Abstract

Historically, maternal HIV research has focused on prevention of mother-to-child transmission and child outcomes, with little focus on the health outcomes of mothers. Over the course of the HIV epidemic, the approach to including pregnant women in research has shifted. The current landscape lends itself to reviewing the public health ethics of this research. This systematic review aims to identify ethical barriers and considerations for including pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV in treatment adherence and retention research. We completed a systematic literature review following PRISMA guidelines with analysis using a relational ethics perspective.

The included studies (k=7) identified ethical barriers related to (1) women research participants as individuals, (2) partner and family dynamics, (3) community perspectives on research design and conduct, and (4) policy and regulatory implications. These broader contextual factors will yield research responsive to, and respectful of, the needs of pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV. While current regulatory and policy environments may be slow to change, actions can be taken now to foster enabling environments for research. We suggest that a relational approach to public health ethics can best support the needs of pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV; acknowledging this population as systematically disadvantaged and inseparable from their communities will best support the health of this population.

Keywords: empirical ethics, HIV, maternal health, adherence, retention

INTRODUCTION

There is a critical public health need for safe and effective HIV treatment for pregnant and postpartum women. Annually, approximately 1.5 million women living with HIV give birth, and nearly half of those who acquire HIV are reproductive-aged women.1 Historically, research has focused on prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT), with existing policies centered around fetal and infant health rather than needs of the woman herself. HIV progression in pregnant women has implications beyond the transmission of HIV to the fetus, including maternal progression to AIDS and mortality.2 Despite the importance of appropriately managing HIV during pregnancy and the postpartum period, critical evidence gaps exist around the safety, efficacy and dosing of ART during pregnancy.3 Including pregnant women in clinical trial research presents substantial ethical barriers; however treatment without appropriate evidence may be harmful to both mothers and fetuses. Consequently, failing to conduct the research that will close these gaps poses an ethical “catch-22.”

Reviewing ethical dimensions of public health topics, which are focused on population-level health promotion and reducing health disparities4, requires a framework which is appropriate for the values and goals of public health work. As opposed to individual level clinical ethics frameworks, public health ethics considers the public’s interests and the common good. For example, a relational perspective of public health ethics situates individuals within communities and explicitly acknowledges that the two are interrelated; this relational approach to public health ethics has been proposed by Baylis, Kenny and Sherwin.5 This approach is founded on values of: 1) relational autonomy, which recognizes persons as socially, politically and economically situated, 2) relational social justice, which is concerned with fair access to social goods such as rights and opportunities, and 3) relational solidarity, which attends to the needs of all persons, with special attention to those who are vulnerable and/or systematically disadvantaged.6

The challenges of weighing risk and benefits of research for pregnant women living with HIV and their fetuses have been discussed extensively in the literature. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, debates centered on whether it was appropriate for women living with HIV to become pregnant, since HIV diagnosis in that era amounted to a death sentence for mother and child.7 In the mid-1990s, trials of zidovudine (AZT) treatment regimens found significantly reduced vertical transmission from mothers to infants.8 This initial regimen was cost-prohibitive for low-income settings, so fifteen randomized controlled trials were launched to evaluate the efficacy of a reduced-dose AZT regimen against a placebo-controlled arm.9 Known as the AIDS Clinical Trial Group (ACTG) 076 protocol, this study was loudly criticized by members of the Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, Peter Lurie and Sidney Wolfe, who argued that this research was unethical because the placebo-controlled design denied access to effective treatment for some study participants.10 Ethical standards for HIV research evolved by the early 2000s, requiring RCTs to use a known effective intervention as the comparison arm. Over the last decade, ART regimens and access to treatment have improved, with policies like Option B+ ensuring life-long access to treatment for pregnant and breastfeeding women.11 In part due to these improvements, adults living with HIV who receive comprehensive treatment have similar rates of mortality as the general population and near-normal life expectancy.12

Over the course of the HIV epidemic, the approach to including pregnant women in research has shifted. Current guidelines prepared by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) challenge the historical view that pregnant women are a vulnerable population, stating that “Pregnant women must not be considered vulnerable simply because they are pregnant.”13 Instead, some groups have argued that pregnant women should be defined as “scientifically complex” or “special populations”14, classifications which acknowledge the distinct physiologies and health needs of pregnant women, but which aim to promote a research environment that is inclusive of pregnant women.

There is agreement that it is ethically questionable to ask a mother to compromise her own health for that of her fetus, yet this principle has not been fully integrated into research practices and clinical recommendations.15 The recent debate over the use of dolutegravir (DTG) in first-line ART for pregnant and breastfeeding women showcases this tension.16 Preliminary data from the Tsepamo study in Botswana suggested an increased risk of neural tube defects (NTDs) among babies born to women taking DTG during periconception (0.94%, 4/426 vs. 0.1%, 14/11,173).17 More recent data indicated a decreased NTD risk of 0.40% (1/248), with additional evaluations ongoing.18 In light of these data, the WHO initially did not recommend DTG-based regimens for women and adolescent girls of childbearing potential, those who wanted to become pregnant, or those without effective contraception, denying effective treatment to a large portion of the population. These recommendations have since been revised based on additional evidence, and DTG is now recommended for all populations, including pregnant women and those of childbearing potential.19 The DTG debate prompted this review, which focuses on research about ethical barriers and considerations for including pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV in studies of treatment adherence and retention.

METHODS

Systematic Review and Search Strategy

We completed a systematic review of the literature following PRISMA guidelines.20 We searched electronic databases to identify studies (PubMed, PsychINFO, CINAHL, Philosopher’s Index, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, and ProQuest PAIS Index; Table 1). We identified search strings (Table 2) from previous literature. We searched abstracts from selected conferences (AIDS 2016 and 2018, AIDS Impact 2017, and AIDS Impact 2019) using the key term “ethic.” As part of grey literature review, we also identified selected book chapters for inclusion.

Table 1:

Database and Conference Search Results

| Database/Conference | Results | Duplicates | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| PubMed | 839 | 6 | 833 |

| PsychINFO | 102 | 38 | 64 |

| CINAHL | 99 | 47 | 52 |

| Philosopher’s Index | 24 | 13 | 11 |

| ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global: Titles & Abstracts Only | 27 | 3 | 24 |

| ProQuest PAIS Index | 1856 | 21 | 1835 |

| AIDS 2018 | 62 | 0 | 62 |

| AIDS 2016 | 76 | 1 | 75 |

| AIDS Impact 2017 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Book Chapters (Grey Literature) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

|

| |||

| Total | 2955 | ||

Table 2:

Full Database Search Terms

| Database Search Terms | |

|---|---|

| Population |

Pregnant or postpartum: *Partum OR *natal OR preg* OR mother* OR matern* Living with HIV: HIV OR “Human Immunodeficiency Virus” OR “Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome” OR AIDS OR CD4 OR serum OR serodiscordant OR serodifferent OR T-cell OR T-helper OR “viral load” |

| Phenomenon of Interest |

Ethics: Ethic*† Treatment and Retention: ART OR “Antiretroviral Therapy” OR HAART OR “Highly active antiretroviral therapy” OR “engagement in care” OR medication OR drug OR ARV OR antiretroviral OR therapy OR treatment OR resistan* OR protect* |

| Example of full database search string – PubMed | (*Partum OR *natal OR preg* OR mother* OR matern*) AND Ethic* AND (HIV OR “Human Immunodeficiency Virus” OR “Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome” OR AIDS OR CD4 OR serum OR serodiscordant OR serodifferent OR T-cell OR T-helper OR “viral load”) AND (ART OR “Antiretroviral Therapy” OR HAART OR “Highly active antiretroviral therapy” OR “engagement in care” OR medication OR drug OR ARV OR antiretroviral OR therapy OR treatment OR resistan* OR protect*) |

Conference abstracts searched using only ethics search term.

Inclusion Criteria

We included studies if they were peer-reviewed journal articles that: (1) focused on pregnant or postpartum women living with HIV and (2) explicitly focused on issues related to research ethics. We also included conference presentations or book chapters that met these focal areas. We excluded studies that were: (1) clinically oriented, (2) focused on ethics of global North-South research, (3) opinion or op-ed pieces, (4) not in English, or (5) not available as full texts.

After removing duplicate studies, we independently screened study titles and abstracts based on the pre-defined eligibility criteria (AZW, JP), with half double-screened to ensure consistency. We performed full-text review of all studies that potentially met inclusion criteria; these were double-coded by two independent screeners (AZW, JP) with consensus reached for inclusion or exclusion. During full-text review, we imposed an additional criterion to exclude studies published before 2000, to focus on current ethical considerations of research studies.

Study Characteristic Coding, Assessment of Study Quality and Analysis

Study characteristic coding included general study information, location, purpose, methodology and findings (Table 3). We evaluated studies presenting primary qualitative data using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist;21 as it does not provide for scoring quality, the findings are discussed qualitatively.

Table 3:

Characteristics of Included Studies (k=7)

| Author and year | Journal/ Conference | Location | Purpose | Methodology | Women’s Voices Represented? | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baggaley & van Praag 2000 | Bulletin of the World Health Organization | Global | To present a framework for making decisions about interventions where there is a high prevalence of HIV among pregnant women. | Secondary Data. Reviews implementation and implementation of health care | No | PMTCT programs have prioritized the health of the child over the health of the mother. Resource allocation is a challenge in finance-limited settings. It may be more ethically acceptable and rational to devote resources to prevention of HIV infection in future mothers than to treat women living with HIV. |

| Nataraj 2005 | Monash Bioethics Review | India | To examine how the “research enterprise” in PMTCT influenced intervention design and policy; includes women’s voices to explore impacts of research | Primary/Secondary Data. Reviews history of PMTCT; interviews with research participants | Partially. Includes voices of research participants. | PMTCT programs have instrumentalized women to ensure an HIV-free child, under the motivation to reduce costs associated with increasing burden of care. PMTCT programs did not evaluate the impact on women involved. Consideration was not given to risks that mothers may face as research participants: mental trauma, stigma, breakdown of relationships, loss of social status, damage to self-esteem and identity, physical illness from cesarean, drug resistance issues, etc. |

| Brewster 2011 | Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health | Global | To discuss the double standard inherent to global inequity, advocate for contextual ethical reasoning and describe clinical practice ethical issues. | Secondary data. Reviews ethical issues related to clinical practice and health resources. | No | There is enormous inequity in standards of clinical practice and health outcomes, particularly with regard to inequity of access to medicines. As such, there are limitations to ethical guidelines (such as CIOMS, Declaration of Helsinki, Beauchamp & Childress) when taken without consideration to context. Informed consent remains problematic. The choices for a participant may be stark: research with good standard of care vs. admission to general ward with limited nursing and care. Compliance with intensive research regulations does not ensure research with high ethical standards. |

| Krubiner et al. 2016 | AIDS | Global | To learn what HIV experts percieve as barriers and constraints to conducting HIV research among pregnant women. | Primary Data. Qualitative - group and one-on-one consults with 62 HIV investigators and clinicians | No | Safety, efficacy and appropriate dosing information are needed for newer ARVs, preventive strategies, and treatment for co-infections. Trials need to address the needs of pregnant women. There are many challenges, including: ethical concerns, legal concerns, financial/professional disincentives, and analytical and logistical complexities. |

| Little et al. 2016 | Book Chapter | Global | To present lessons learned about research in pregnancy from HIV/AIDS | Secondary Data. Reviews ethical conduct of HIV trials in pregnant women. | No | It is critical to address the health needs of the woman for her own sake, not just the needs of the fetus. We lack appropriate dosing information, safety and efficacy data. The issues of fetal “risk” and “potential benefit” need to be considered carefully. Benefit to the mother is often benefit to the child. Pregnancy does not (by itself) limit the ability to reason or make decisions. Therefore, it may not be appropriate to consider pregnant women to be a vulnerable population. |

| Little 2018 | AIDS 2018 | Botswana, Malawi, South Africa, US | To discuss the safety of dolutegravir in pregnancy and contrast the risks and benefits for women living with HIV | Secondary Data. Reviews DTG evidence and WHO recommendations | No | Although dolutegravir improves quality of life and reduces women’s mortality (positive impact on women’s lives), policy does not allow women to choose this option due to concerns of wellbeing for potential children. |

| Sullivan et al. 2018 | Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics | Malawi, USA | To describe the perspectives of pregnant women living with or at risk of HIV regarding a requirement for paternal consent in biomedical research | Primary Data. Qualitative - in-depth interviews with 140 pregnant women living or at risk of HIV in Malawi and the USA. | Yes. Entirely informed by women’s voices. | Women articulated nuanced and multifaceted opinions on the rule. The majority of women supported paternal consent requirements when the potential benefits of the study are limited solely to the fetuses. Relationship power dynamics play a role in women’s engagement in research requiring paternal consent. |

RESULTS

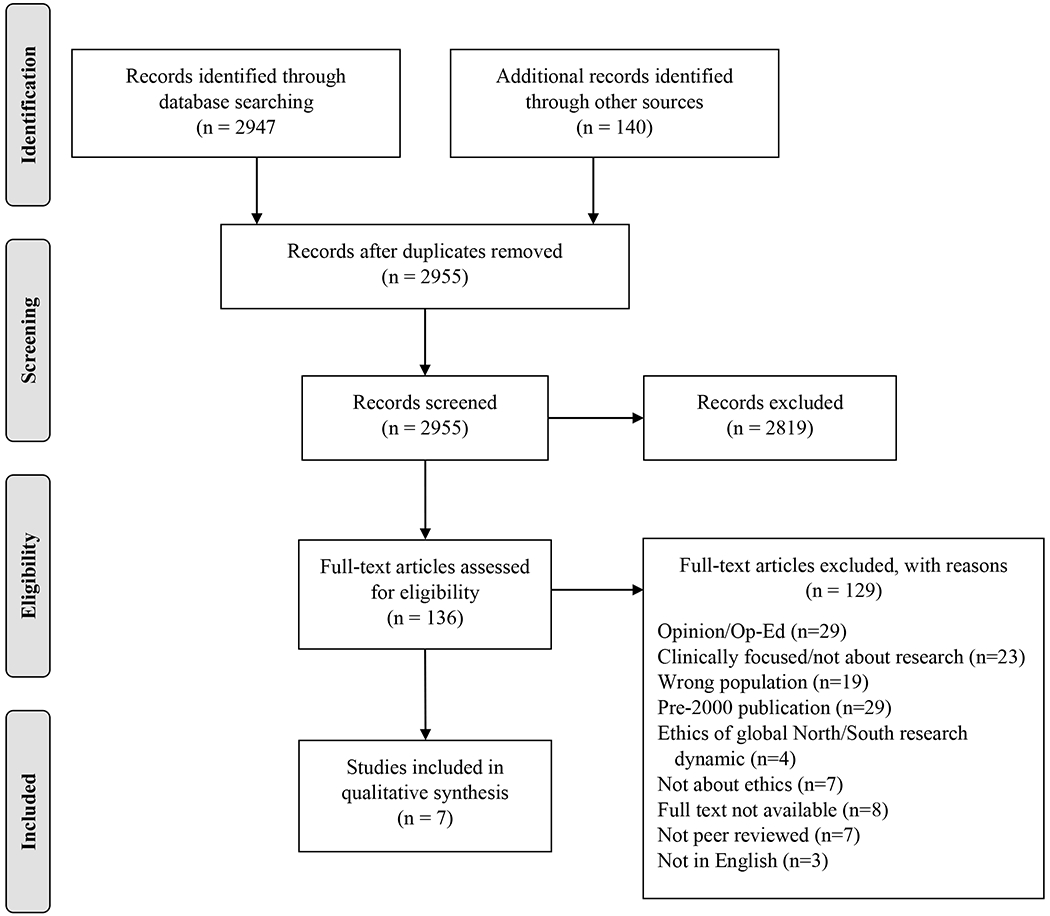

We reviewed a total of 2955 titles and abstracts (Figure 1). Most articles (k=29) that underwent full-text review were published before 2000. Of these, most were published in 1998, after Lurie and Wolfe’s article denouncing unethical PMTCT studies in developing countries.22 In order to focus our review on topics more relevant to the current state of HIV treatment, our descriptive review encompasses only articles from 2000 to January 2019.

Figure 1:

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Each included study (k=7) identified ethical barriers to including pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV in treatment adherence and retention research. Table 3 includes a full description of the extracted variables. Briefly, while Nataraj (2005) focused on barriers in India, the remaining studies pertained to broader geographic areas. Two studies presented primary qualitative data (Sullivan et al. 2018, Krubiner et al. 2016), while the remainder represented viewpoints, commentaries or policy pieces. Overall, the studies identified an array of ethical barriers, including: (1) the woman research participant as an individual, (2) partner and family dynamics, (3) community perspectives on research design and conduct, and (4) policy and regulatory implications.

Mothers as Individuals: Rights of Pregnant Women

Nearly all studies identified the need for research to more directly address the needs of pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV, as participants themselves are best positioned to speak to their needs. Despite these calls for enhanced focus on women, only 2 of the 7 studies included the voices of pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV. Sullivan et al. (2018) conducted a qualitative study to describe the perspectives of pregnant women living with or at risk for HIV (n=140) regarding paternal consent requirements in biomedical research.23 Entirely informed by women’s voices, this study found that while women have nuanced and multifaceted opinions regarding paternal consent requirements, the majority supported these requirements when the potential benefit of the study was limited to the fetuses.

Nataraj (2005) conducted a study to, in part, explore the impacts of PMTCT research on women in India.24 Opinions of women indicated that PMTCT programs conducted in India did not adequately address potential risks to women involved. Some women participating in PMTCT research suffered mental trauma, relationship breakdown, loss of social status, damage to self-esteem and identity, depression and isolation.25 In light of these negative consequences, researchers called for future work to focus on improving the health of the woman for her own sake, and with consideration to the social, political and economic contexts surrounding participants.26

These studies emphasize the need for careful consideration of what constitutes meaningful consent for women living with HIV, with acknowledgement that individual’s actions are not independent or separate from our social circumstances. For instance, Nataraj pointed out that participants may feel uncomfortable declining study enrollment, particularly if consent is obtained within groups rather than individually.27 In resource-constrained settings, the choice to participate in a study may be stark: study enrollment with a good standard of care versus a general care setting with limited resources.28 The trade-offs can be obvious to participants, and thus the decision about whether to participate may not be truly autonomous.

Partner and Family Dynamics as Influences on Women’s Participation in Research Studies

Aside from considerations about the individual needs of women living with HIV, two studies identified the need to consider broader partner and family dynamics during research design and conduct. One ethical barrier concerns that of the appropriate role for the fetus’ father in the consent process. Those in favor of paternal consent requirements believe that it protects fathers’ rights and fetal welfare, while those opposed argue that they do not adequately respect pregnant women’s autonomy or the diversity of family dynamics and may discourage participation in research studies.29

While these dynamics have been discussed among researchers, clinicians and other stakeholders, only one study considered pregnant women’s views.30 Through in-depth interviews, women reported that their views on paternal consent requirements were strongly tied to their relationship dynamics.31 For example, requiring consent from partners may expose women to relationship violence if their partners were unaware of their HIV status and could inhibit some women’s willingness to participate in studies. In contrast, some women identified that paternal consent requirements could strengthen families, provide multiple levels of protection for fetuses, and reinforce shared partner responsibility for fetuses. Although many regulations waive the paternal consent requirement only in instances of rape or absent fathers, the issues raised by the women interviewed relate to the dynamics internal to committed relationships, particularly when power differentials exist. It bears noting that partners’ voices were not represented in this study, so these findings were based on women’s perspectives of partners’ involvement and reactions to the paternal consent requirement.

Family dynamics are also an important consideration for research, especially in settings where families play a large role in child rearing or supporting the mother throughout pregnancy and postpartum. Nataraj (2005) interviewed a research participant in India who experienced a break-down of her family relationships in the wake of a home visit from a study social worker, which was highly unusual and caused suspicion within her community. Ultimately, this forced the woman to disclose her HIV status to her partner and mother-in-law, resulting in estrangement from her in-laws.32 While this was an anecdotal example, Nataraj concluded that it showcases a broader trend in HIV research in that research practices have not historically been sensitive to family dynamics.

Together, these studies point to the need for future research to be more responsive to the needs and concerns of pregnant women with regards to her partner and familial context, ensuring that she has ownership over her HIV status disclosure to avoid serious social and medical implications.33

Community Perspectives on Research Design and Conduct for Pregnant Women

Three of the studies reviewed focused on the need for community participation in research to ensure that research addresses the needs of the community; these findings highlight the social justice component of public health.34 Nataraj (2005) argues that the stigma associated with HIV exposes pregnant and postpartum participants to an array of harms, from physical violence to social isolation and mental trauma. Brewster (2011) argues that studies must be responsive to the health needs and priorities of the communities in which they are situated, and knowledge gained must be made available to community members.35 Baggaley & van Praag (2000) underscore the importance of community consultation in resource-constrained settings, where decisions about allocation of research dollars are sensitive and research must address the most pressing health needs facing those at systemic disadvantage.36

Taken together, these authors point to the need for a social justice lens when undertaking research within populations who are exposed to patterns of systemic injustice, such as women who are living with HIV. Community consultation in protocol development, design and evaluation of procedures for disclosure, informed consent, confidentiality measures and right of dissent are paramount. Community members may have valuable contextual knowledge to identify gaps in research protocols or additional protective measures to ensure that harms to participants are minimized, while rights to participation are maximized.37

The remainder of the 7 articles included in this review did not focus on community level factors for HIV care and adherence research. In comparison with the other themes presented in this review, there was less consideration regarding the importance of community consultation or community consent in research design and conduct among included studies.

Regulatory Perspectives towards Including Pregnant Women in Research

The studies identified a variety of regulatory constraints, including: (1) vague and complex regulatory language creating uncertainty around what research is permissible, (2) lack of an enabling regulatory environment, and (3) narrow focus on regulatory compliance as the indicator of ethical research.

Little et al. (2016) found that complex regulatory requirements can inhibit research from being conducted among pregnant women living with HIV.38 Both Little et al. (2016) and Krubiner et al. (2016) discussed that uncertainties around how to distribute and minimize risk deterred research in pregnant women.39 The interpretation of what constitutes “minimal risk” can vary; however, they reported that an extremely cautious interpretation was usually used to ensure that research did not harm the fetus.40 Krubiner et al. (2016) also found that oversight officials and IRB reviewers were reluctant to approve studies involving pregnant women and may have assumed that pregnant women should be excluded from studies.41 Overall, these studies found that ambiguities in the regulatory requirements and subjective interpretation of risk created uncertainty about what constitutes permissible research.

Without clarity around regulatory requirements, some authors argue that research is caught in a vicious cycle:42 Little et al. (2016) and Krubiner et al. (2016) describe lack of an enabling regulatory environment and historical attitudes towards research with pregnant women as responsible for the limited safety and efficacy data about HIV treatment regimens in pregnant women today. These factors create reluctance to study treatment for fear of inflicting harm on the pregnant woman or fetus, which in turn perpetuates a system with limited data.43 With unknown maternal-fetal exposure risks, lack of appropriate dosing information, and limited safety-efficacy data, clinical decisions can amount to guesswork. For example, Little et al. (2016) pointed out that changes in metabolism during pregnancy can impact dosing levels, safety and efficacy, and can contribute to over-dosing (causing toxicity) or under-dosing (causing poor control of viral load and potential for resistance).44

Brewster (2011) echoed this concern regarding limited data, pointing out that focusing exclusively on whether research complies with regulations, particularly when this means that pregnant women are simply excluded from trials, does not ensure that research is conducted following high ethical standards.45 Little et al. (2016) argued that research providing direct medical benefit to pregnant women necessarily provides direct medical benefit to fetuses because the pregnancy and fetus are at risk if illnesses are not properly treated.46 Similarly, Krubiner et al. (2016) argued that research approval processes should encourage explicit discussion and justification for decisions about pregnancy as inclusion or exclusion criteria in trials.47 These approaches advocate for more dialogue around the inclusion process, with the goal to conduct ethical research within an enabling regulatory environment that promotes research.

Study Quality

The two articles presenting qualitative primary data were evaluated using the COREQ checklist. The Sullivan et al. (2018) article included approximately half of the items required on the checklist. While the article robustly described the analysis approach and findings, items related to research team, reflexivity, and study design (namely, how participants were approached, how many refused to participate, and where the interviews were conducted) were not well described. The Krubiner et al. (2016) article presented synthesized opinions from international HIV experts. Rather than using a qualitative study protocol, the article disseminated information from consultations and meetings conducted under the Pregnancy and HIV/AIDS: Seeking Equitable Study (PHASES) project. As such, few of the COREQ items were reported. The remainder of the articles did not present primary data and thus could not be evaluated with the COREQ checklist.

DISCUSSION

HIV research has a strong track record of involving pregnant women, but the field is struggling to move beyond PMTCT programs to focus on the health of the pregnant women themselves.48 Research must be respectful of participants as individuals and as mothers, to prioritize a mother’s health for her own sake and as guardian of her fetus. Participants’ needs must also be considered in the context of their partnerships, families and communities. However, lack of an enabling environment for ethical design and regulations regarding research among women living with HIV constrains the ability of researchers to conduct this work.

Given these findings, the field of HIV research has arguably not moved beyond viewing women as reproductive vessels.49 It has long been established that asking a mother to compromise her health in the interest of that of her fetus or her potential child is ethically questionable.50 Yet, little work has been done to include women’s voices in HIV research. The studies reviewed here point to the importance of including participants’ views in decision-making.51 Women living with HIV may be more aware of ethical considerations for research that policy makers or scholars could overlook in research design or conduct. Women identified the need for better support of participants in studies requiring paternal consent, as participation may harm the women’s well-being within their relationships or expose women to partner violence.52 Centering research design around ongoing consultation with women living with HIV ensures that the needs and wellness of the research participants themselves are prioritized.53

Some work has been conducted examining partner and family dynamics; however, partner voices were not well represented. Inclusion of partner perceptions and experiences when possible can enhance awareness of the interpersonal dynamics surrounding pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV and contribute to research design considerations. The work done by Sullivan et al. suggests that the negative aspects of requiring paternal consent are greater than the benefits of requiring it.54 For women who can easily obtain consent from partners, this requirement does not pose a barrier to care as women can inform their partners without risk. However, women who are in unstable partnerships or have not disclosed their HIV status are likely to avoid trial participation if paternal consent is required.

In identifying the varying perspectives that women have towards paternal consent requirements, the work done by Sullivan et al. underscores the value of situating research participants within their social relationships. Taking a relational autonomy perspective for public health research gives an opportunity to examine the impact of policies like paternal consent on a population. For instance, a paternal consent requirement may bolster the autonomy of a father, but that may come at the expense of a mother’s autonomy. A relational perspective suggests that the best approach moving forward may require a shift away from existing consent requirements and toward policies that support fairness, inclusivity, and responsiveness to systemic inequalities.55 Future studies that center the voices of pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV may identify additional ethical issues related to relational autonomy, and may provide further empirical evidence to inform more inclusive research policies.

Some studies pointed to the need for ethical study design to take a more holistic approach responsive to the health needs of individuals within the context of their communities. Leveraging community members’ expertise in study design and conduct ensures that social norms are respected and minimizes potential harms to research participants. In practice, this can be achieved by using a participatory approach to study design, ranging from consulting with community members on aspects of study design to community-based participatory research that equitably involves community members as equal partners in research. Since enhanced collaboration with community members can yield culturally-sensitive practices and more supportive research environments, it merits greater attention.

Taking a relational approach can provide a richer understanding of how we might understand the normative value of community-engaged research, given these findings. Relational social justice is focused on ensuring equitable access to social goods, including rights and opportunities.56 Relational social justice assesses the implications for social groups collectively, in an effort to identify patterns of inequality or disadvantage. Within a relational approach, the values of fairness, inclusivity and transparency support conducting community-engaged research, and further suggest that we must evaluate policy-making processes to correct patterns of systemic disadvantage.

The policy and regulatory environments that encompass research with pregnant and postpartum women can either derail or support research that is needed to improve health outcomes for this population. Clearer guidance is needed regarding ethical and legal uncertainties about research during pregnancy.57 Moreover, the opportunity exists to re-conceptualize and reinforce the need to prioritize the health of women living with HIV, both for their own sakes and their children. Researchers, ethics committees and regulators can encourage inclusion of pregnant women living with HIV in studies. For instance, in the US, the shift away from categorizing pregnant women as vulnerable populations may create a more supportive regulatory environment.58 The research approval process can further shift to assume inclusion, rather than exclusion, of pregnant women.59 Researchers have also proposed creative trial designs that advance research while minimizing risk to participants.60

This study is the first, to our knowledge, that attempts to systematically identify and synthesize literature around ethical barriers to the inclusion of pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV in treatment and retention research. As with any systematic review, it is possible that we were unable to identify all relevant articles for inclusion. Our results are also subject to publication bias. Further, as this review included two primary data articles and five viewpoint or commentary articles, there is a risk of bias both within and across the studies. Without additional studies presenting primary quantitative and/or qualitative data, this review is unable to draw any conclusions about whether the findings from these studies are consistent with a body of literature. We are also constrained in our ability to make robust ethical syntheses that can move these debates forward. However, we believe that this review is uniquely positioned to shed light on critical gaps in knowledge and the state of literature around inclusion of pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV in treatment and retention research.

To end, the concept of relational solidarity refers to attending to the needs of all, with particular attention to those who are systematically disadvantaged.61 The basis for relational solidarity is the interconnection of all persons, founded in our shared human interests in survival, safety and security. For pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV, there is a clear normative argument for a social justice approach to correct the conditions that inhibit research that could improve health outcomes for this population. Relational solidarity suggests that we should focus on this population in particular, because pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV may be subject to multiple layers of vulnerability and disadvantage, including low economic resources, racial/ethnic minority status and/or stigma associated with HIV status. Our collective identities, as humans, requires us to attend to the needs of this group.

CONCLUSIONS

Given the urgent public health need for safe and effective HIV treatment for pregnant and postpartum women, what constitutes ethical design and conduct of research must be considered. Consistent with a relational approach to public health ethics, the values of relational autonomy, relational social justice, and relational solidarity can guide future public health research programs. Broader consideration of contextual factors such as partner, family and community dynamics will yield research that is responsive to and respectful of the needs of pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV. Regulatory and policy actions can be taken to create a more enabling environment for research. We suggest that a relational approach to public health ethics can best support the needs of pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV; acknowledging this population as systematically disadvantaged and inseparable from their communities will best support the health of this population.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank those who provided comments and support for this paper, particularly Kira DiClemente, Georgie McTigue, Anne Weber, and Caroline Kuo. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers of this manuscript for their insightful comments. Support for data analysis and manuscript preparation was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH112443, PI: Pellowski). The funders did not have any role in the development, execution, or writing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. The gap report: children and pregnant women living with HIV; World Health Organization. Global health sector response to HIV, 2000-2015: focus on innovations in Africa. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 2.French R, & Brocklehurst P The effect of pregnancy on survival in women infected with HIV: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998; 105(8): 827–35: 827–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krubiner CB, et al. Advancing HIV research with pregnant women: navigating challenges and opportunities. AIDS 2016; 30(15): 2261–65: 2261–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Little MO, et al. 2016. Ethics and research with pregnant women: lessons from HIV/AIDS. In Baylis F, & Ballantyne A, eds. Clinical research involving pregnant women. Cham: Springer International Publishing [Google Scholar]; Little M. Safety of dolutegravir in pregnancy: weighing up the risks and benefits. Amsterdam, the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beauchamp DE. 1999. Public Health as Social Justice. In Beauchamp DE, & Steinbock B, eds. New Ethics for the Public’s Health. New York: Oxford University Press:1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenny NP, et al. Re-visioning Public Health Ethics: A Relational Perspective. Can J Public Health 2010; 101(1): 9–11: 9–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Baylis F, et al. A Relational Account of Public Health Ethics. Public Health Ethics 2008; 1(3): 196–209: 196–209. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenny, et al. (cited n. 5) : 9–11 [Google Scholar]; Baylis, et al. (cited n. 5) : 196–209. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nolan K. Human immunodeficiency virus infection, women, and pregnancy. Ethical issues. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 1990; 17(3): 651–68: 651–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhutta ZA. Ethics in international health research: a perspective from the developing world. Bull World Health Organ 2002; 80(2): 114–20: 114–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Resnik DB. The ethics of HIV research in developing nations. Bioethics 1998; 12(4): 286–306: 286–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lurie P, & Wolfe SM. Unethical Trials of Interventions to Reduce Perinatal Transmission of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus in Developing Countries. N Engl J Med 1997; 337(12): 853–56: 853–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knettel BA, et al. Retention in HIV Care During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period in the Option B+ Era: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies in Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2018; 77(5): 427–38: 427–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson LF, et al. Life Expectancies of South African Adults Starting Antiretroviral Treatment: Collaborative Analysis of Cohort Studies. PLoS Med 2013; 10(4): e1001418: e1001418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Boulle A, et al. Mortality in Patients with HIV-1 Infection Starting Antiretroviral Therapy in South Africa, Europe, or North America: A Collaborative Analysis of Prospective Studies. PLoS Med 2014; 11(9): e1001718: e1001718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS). International Ethical Guidelines for Health-related Research Involving Humans, Fourth Edition. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimsrud KN, et al. Special population considerations and regulatory affairs for clinical research. Clin Res Regul Aff 2015; 32(2): 45–54: 45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Little (cited n. 3).

- 16.Moorhouse MA, et al. Southern African HIV Clinicians Society Guidance on the use of dolutegravir in first-line antiretroviral therapy. South Afr J HIV Med 2018; 19(1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; World Health Organization. Updated recommendations on first-line and second-line antiretroviral regimens and post-exposure prophylaxis and recommendations on early infant diagnosis of HIV: interim guidelines. Supplement to the 2016 consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zash R, et al. Neural-Tube Defects with Dolutegravir Treatment from the Time of Conception. N Engl J Med 2018; 379(10): 979–81: 979–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mofenson LM. Periconceptional Antiretroviral Exposure and Central Nervous System and Neural Tube Defects - Data from the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry. Mexico City, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO recommends dolutegravir as preferred HIV treatment option in all populations. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/22-07-2019-who-recommends-dolutegravir-as-preferred-hiv-treatment-option-in-all-populations [Accessed 20 October 2019].

- 20.Moher D, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6(7): e1000097: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong A, et al. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19(6): 349–57: 349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lurie, & Wolfe (cited n. 10) : 853–56. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan KA, et al. Women’s Views About a Paternal Consent Requirement for Biomedical Research in Pregnancy. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2018; 13(4): 349–62: 349–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nataraj S. Ethical considerations in research on preventing mother-to-child HIV transmission. Monash Bioeth Rev 2005; 24(4): 28–39: 28–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ibid.; Bennetts A, et al. Determinants of depression and HIV-related worry among HIV-positive women who have recently given birth, Bangkok, Thailand. Soc Sci Med 1982. 1999; 49(6): 737–49: 737–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Little, et al. (cited n. 3); Nataraj (cited n. 24): 28–39 [Google Scholar]; Baggaley R, & Praag E. van. Antiretroviral interventions to reduce mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus: challenges for health systems, communities and society. Bull World Health Organ 2000; 78(8): 1036–44: 1036–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nataraj (cited n. 24): 28–39.

- 28.Ibid.; Brewster D. Science and ethics of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome controversies in Africa: Ethics of HIV in Africa. J Paediatr Child Health 2011; 47(9): 646–55: 646–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sullivan, et al. (cited n. 23): 349–62.

- 30.Ibid.

- 31.Ibid.

- 32.Nataraj (cited n. 24) : 28–39.

- 33.Ibid.; Sullivan, et al. (cited n. 23) : 349–62.

- 34.Nataraj (cited n. 24) : 28–39; Brewster (cited n. 28) : 646–55; Baggaley, & Praag van (cited n. 26) : 1036–44.

- 35.Brewster (cited n. 28) : 646–55.

- 36.Ibid.; Baggaley, & Praag van (cited n. 26) : 1036–44.

- 37.Nataraj (cited n. 24) : 28–39.

- 38.Little, et al. (cited n. 3).

- 39.Krubiner, et al. (cited n. 3) : 2261–65.

- 40.Ibid.

- 41.Ibid.

- 42.Ibid.; Little (cited n. 3); Little, et al. (cited n. 3).

- 43.Little, et al. (cited n. 3); Krubiner, et al. (cited n. 3) : 2261–65.

- 44.Little, et al. (cited n. 3).

- 45.Brewster (cited n. 28) : 646–55.

- 46.Little, et al. (cited n. 3).

- 47.Krubiner, et al. (cited n. 3) : 2261–65.

- 48.Little, et al. (cited n. 3).

- 49.Sullivan, et al. (cited n. 23) : 349–62; Nataraj (cited n. 24) : 28–39; Baggaley, & Praag van (cited n. 26) : 1036–44; Little, et al. (cited n. 3).

- 50.Baggaley, & Praag van (cited n. 26) : 1036–44.

- 51.Sullivan, et al. (cited n. 23) : 349–62; Nataraj (cited n. 24) : 28–39.

- 52.Sullivan, et al. (cited n. 23) : 349–62.

- 53.Little (cited n. 3).

- 54.Sullivan, et al. (cited n. 23) : 349–62.

- 55.Kenny, et al. (cited n. 5) : 9–11; Baylis, et al. (cited n. 5) : 196–209.

- 56.Kenny, et al. (cited n. 5) : 9–11; Baylis, et al. (cited n. 5) : 196–209.

- 57.Krubiner, et al. (cited n. 3) : 2261–65.

- 58.Buchanan L. Brief Overveiw of the Revised Common Rule and Subpart B - Pregnant Women.

- 59.Krubiner, et al. (cited n. 3) : 2261–65.

- 60.Little, et al. (cited n. 3).

- 61.Kenny, et al. (cited n. 5) : 9–11; Baylis, et al. (cited n. 5) : 196–209.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.