Abstract

Background:

Although vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (VEGFR TKIs) are a preferred systemic treatment approach for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and thyroid carcinoma (TC), treatment-related cardiovascular (CV) toxicity is an important contributor to morbidity. However, the clinical risk assessment and impact of CV toxicities, including early significant hypertension, among real-world advanced cancer populations receiving VEGFR TKI therapies remain understudied.

Methods:

In a multicenter, retrospective cohort study across three large and diverse US health systems, we characterized baseline hypertension and CV comorbidity in RCC and TC patients newly initiating VEGFR TKI therapy. We additionally evaluated baseline patient-, treatment-, and disease-related factors associated with the risk for treatment-related early hypertension (within 6 weeks of TKI initiation) and major adverse CV events (MACE), accounting for the competing risk of death in an advanced cancer population, following VEGFR TKI initiation.

Results:

Between 2008 – 2020, 987 patients (80.3% with RCC; 19.7% with TC) initiated VEGFR TKI therapy. The baseline prevalence of hypertension was high (61.5% and 53.6% in RCC and TC patients, respectively). Adverse CV events, including heart failure and cerebrovascular accident, were common (occurring in 14.9% of patients) and frequently occurred early (46.3% occurred within 1 year of VEGFR TKI initiation). Baseline hypertension and Black race were the primary clinical factors associated with increased acute hypertensive risk within 6 weeks of VEGFR TKI initiation. However, early significant ‘on-treatment’ hypertension was not associated with MACE.

Conclusion:

These multicenter, real-world findings indicate that hypertensive and CV morbidities are highly prevalent among patients initiating VEGFR TKI therapies, and baseline hypertension and Black race represent the primary clinical factors associated with VEGFR TKI related early significant hypertension. However, early ‘on-treatment’ hypertension was not associated with MACE, and cancer-specific CV risk algorithms may be warranted for patients initiating VEGFR TKIs.

INTRODUCTION:

Small molecule receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) represent a mainstay systemic therapy for several advanced solid tumor malignancies. (1) In particular, anti-angiogenic VEGFR TKI therapies are a preferred systemic treatment approach for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and thyroid carcinoma (TC), which represent the most common prescription indications. Indeed, prolonged VEGFR signaling inhibition with VEGFR TKIs is commonly utilized for several advanced TCs. (2) In addition, seven VEGFR TKI therapies have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of advanced RCC, either as monotherapy or in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). (3–5)

Despite these important oncologic benefits, VEGFR TKI treatment results in clinically important cardiovascular (CV) toxicity. Numerous CV toxicities, including incident left ventricular dysfunction and hypertension, are class effects associated with VEGFR TKI therapies. (6, 7) Incident or worsening of pre-existing hypertension represents the most common ‘on-target’ CV toxicity, affecting up to 70% of patients. (8, 9) Although treatment-related hypertension on VEGFR TKI therapy is reflective of therapeutic drug activity and is associated with improved cancer-related outcomes, such CV toxicities may also contribute to adverse CV outcomes and result in treatment modifications, delays, or cessation of effective cancer therapy. (10–12) These toxicities may be of mounting importance given the improving long-term clinical outcomes recently observed with novel VEGFR TKI-based regimens across both TC and clear cell RCC malignancies. (4, 9)

Yet, a comprehensive understanding of CV toxicity risk and adverse CV events in real world cancer patients receiving VEGFR TKI therapies remains incompletely defined. First, while blood pressure (BP) management and CV risk mitigation guidelines in non-cancer populations are informed by well-established patient-related risk factors and BP targets, much of the available data regarding clinical risk assessment and impact of VEGFR TKI CV toxicities in advanced cancer patients are derived from clinical trial populations, which may not be generalizable to patients cared for in everyday practice. (13) Moreover, prior studies evaluating the impact of prevalent CV risk factors on risk for hypertensive or other treatment-related CV events on VEGFR TKI therapies are of limited sample size and have reported varied and inconsistent associations. (8, 14, 15) Second, while adequate BP control in non-cancer populations is known to significantly reduce morbidity and mortality from adverse CV events, the association between BP change and adverse CV events in advanced cancer patients receiving VEGFR TKI therapies is unknown. (16, 17) As a result, expert statements on CV risk assessment and BP control for patients receiving VEGFR TKI therapies have relied on standard risk assessment tools developed for non-cancer populations. (18) However, given the competing risks of cancer and non-cancer adverse outcomes, the optimal BP target may be unique in cancer populations. Given these limitations, a number of unanswered questions remain. For example, what individual patient characteristics and treatment-related factors are most strongly associated with early BP changes? What are the associations between early on-treatment BP changes and subsequent adverse CV events? Are certain BP thresholds associated with improved clinical outcomes?

To address these current knowledge gaps and inform a real-world approach to VEGFR TKI hypertension and CV toxicity, we evaluated the key factors unique to an advanced cancer population that may inform the risks of early significant hypertension and adverse CV events, accounting for the competing risk of death. We first comprehensively characterized the baseline patient-, treatment-, and disease-related factors associated with early, acute treatment-related hypertension risk and with longer term major adverse CV outcomes following initiation of VEGFR TKI therapy. In an exploratory analysis, we evaluated the association between on-treatment early BP elevations and risk of major adverse CV outcomes to gain insight into potential BP targets within this advanced cancer population.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We performed a multicenter retrospective cohort study of RCC and TC patients receiving cancer care at 3 large health systems, including Penn Medicine (Penn) and Barnes-Jewish Hospital/Washington University in St. Louis (WashU), both quaternary care academic medical centers, and the Geisinger Health System (GHS), a regional healthcare network serving central and northeastern Pennsylvania. Using the Penn Data Store, Clinical Desktop and Touchworks, and the Geisinger data warehouse, which are the enterprise data warehouses containing aggregated longitudinal clinical data from the electronic health record (EHR) at Penn, WashU, and GHS, respectively, we extracted information on patient demographics, hospital and office encounters, comorbidities, inpatient and outpatient medications, cancer therapies, procedures, and vital status using International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision (Clinical Modifications) (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes (Supplemental Table 1). Available data related to VEGFR TKI administration, including dosages and prescription dates, were also extracted from the data warehouses. A full description of extracted data elements is listed in the Supplemental Methods.

Patients with RCC or TC initiating first treatment with VEGFR TKI therapy, identified via an outpatient or inpatient prescription, with a treatment start date between January 1, 2008 and May 31, 2020 and a corresponding clinical provider visit were included. In order to identify patients with a new exposure to VEGFR TKI therapy followed longitudinally at the study site, an observable period of at least 90 days without VEGFR TKI exposure and a minimum duration of 30 days between the VEGFR TKI start date and the last observed clinical provider visit date were required. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Boards at each participating site, and informed consent was not required.

Covariate and Outcomes Definitions

Prevalent hypertension was defined as having either ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes recorded on at least one encounter or the prescription of an anti-hypertensive medication during the 90 days before VEGFR TKI initiation (Supplemental Table 1). Hypertensive medications included beta blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, diuretics, calcium channel blockers, and nitrates, as well as unclassified anti-hypertensives such as hydralazine. Other baseline CV risk factors (hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus) and CV disease (heart failure (HF), coronary artery disease (CAD), peripheral artery disease (PAD), and cerebrovascular accident (CVA)) were defined by ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes present during at least one encounter prior to VEGFR TKI initiation. Baseline BP was calculated as the mean of recorded values in the 90 days prior to VEGFR TKI initiation. Major adverse CV events (MACE) following VEGFR TKI initiation comprised a composite outcome of CV-related medical encounters, including HF (occurring in at least 1 inpatient encounter or 2 outpatient encounters at least 30 days apart), acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization (occurring as primary or secondary inpatient diagnostic codes), or CVA (occurring as primary inpatient diagnostic code). For patients with a history of baseline HF, incident HF was only included if occurring as a primary inpatient diagnosis code, indicating hospitalization for exacerbation of prevalent HF. All CV diagnoses were ascertained by the clinical provider at the time of the health system encounter. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the CKD-EPI equation. (19) Patients receiving concomitant immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy with VEGFR TKI initiation were defined as having the presence of an ICI treatment order within 60 days of the initial VEGFR TKI prescription.

Statistical Analyses

We first sought to characterize prevalent hypertension and CV comorbidity at the time of initiation of VEGFR TKI therapy (baseline). Baseline patient characteristics were summarized using proportions for categorical variables and median with 25th and 75th percentiles (Q1 – Q3) for continuous variables. The Chi-square test or ANOVA were used for statistical comparisons across groups (cancer type, race).

We then sought to evaluate the associations between baseline patient- and treatment-related variables and the outcomes of early significant hypertension, MACE, and overall survival following VEGFR TKI initiation. First, in order to evaluate the associations between baseline characteristics with the outcome of early hypertension following VEGFR TKI initiation, we evaluated BP measures on a continuous scale. Multivariable linear regression models were used to evaluate the association between baseline characteristics and early change in SBP or DBP from baseline. We evaluated this BP outcome within 6 weeks following VEGFR TKI initiation, given the known significant early effects of VEGFR TKIs on BP, and to minimize confounding by CV or oncologic therapy. In the event of multiple BPs obtained for a patient within a single day, the mean BP within a day was used. Independent variables in the multivariable models were selected a priori based on clinical judgment and included age, race, sex, clinical treatment site, baseline SBP, VEGFR TKI type, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, cancer type, and baseline use of any anti-hypertensive medication. Interaction analyses for pre-specified, hypothesized effect modifiers, including cancer type, race, and history of hypertension were also conducted.

The incidence of composite MACE and its association with baseline patient- and treatment-related characteristics was evaluated using a competing-risks framework, to account for the risk of death in an advanced cancer population. In order to evaluate the prognostic factors associated with MACE incidence, the distribution of time to first MACE following VEGFR TKI treatment initiation was evaluated using cumulative incidence functions (CIFs), and Gray’s test was used to compare CIFs among subgroups defined by baseline factors. Subdistribution hazard ratios (HRs), the ratio of the instantaneous risks of having MACE between subgroups defined by baseline factors, were estimated. Covariates included in an adjusted MACE competing risk model were selected a priori based on clinical judgment and included age, race, sex, treatment site, cancer type, diabetes mellitus, baseline SBP > 140 mmHg, hyperlipidemia, and history of CV disease.

In an exploratory analysis, the association between early on-treatment BP change during the initial treatment period and incident MACE was evaluated using a competing risk framework accounting for the risk of death. Early on-treatment BP change was defined as the difference between mean baseline SBP (or DBP) and the peak SBP (or DBP) within 4 weeks of VEGFR TKI initiation. On-treatment early SBP or DBP changes were categorized as an increase of <10 mmHg (reference), 10 – 20 mmHg, and ≥ 20 mmHg. CIFs with estimates of sub-distribution HR were used to assess the association between early on-treatment BP changes with incident adverse CV outcomes (the first of MACE or death), adjusted for age, race, sex, cancer type, baseline CV disease, and baseline use of any anti-hypertensive medication. For these time-to-event analyses, patients were followed until the first of MACE or death, or censored at 2 years following VEGFR TKI initiation to minimize confounding.

Finally, multivariable Cox regression models were used to define the predictors of all-cause survival. Clinical factors of interest that were determined a priori included age, race, sex, treatment site, baseline eGFR, history of prior nephrectomy, hypertension, CV disease, BMI (categorical > 30 kg/m2), and cancer type. For the time-to-event MACE and overall survival analyses, patients were followed from VEGFR-TKI initiation to the first event, death, or censored at the date of the last follow-up visit.

Model regression coefficient estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented for linear regression models, odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs are presented for logistic regression models, and HRs with 95% CIs are presented for subdistribution and Cox proportional hazards models. A two-sided alpha level of 0.05 was used to assess statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

RESULTS

Patient Population and Baseline Hypertension and CV Morbidity

A total of 987 eligible patients, including 793 (80.3%) with RCC and 194 (19.7%) with TC were included in the study cohort (Table 1), with baseline characteristics by treatment site shown in Supplemental Table 2. The median age of the study cohort at baseline was 63 (Q1-Q3 56 – 71) years, 85.2% were White, and 8.4% were Black or African American. The most common VEGFR TKIs initiated in RCC patients were pazopanib (40.2%) and sunitinib (37.7%), whereas the most common VEGFR TKIs newly initiated in TC patients were sorafenib (40.2%) and lenvatinib (24.7%). Among patients with RCC, 64.6% had prior nephrectomy, and 59.9% had chronic kidney disease (median eGFR 56.8 mL/min/1.73m2, Q1-Q3 42.0 – 76.8). The prevalence of hypertension and CV disease at baseline was high --- among patients with RCC and TC, respectively, 61.5% and 53.6% had hypertension, 19.8% and 12.4% had CAD, 8.8% and 6.2% had heart failure. One-third of patients (N=329) had an average SBP ≥ 140 mmHg (median 148; range 139 – 206) during the 90 days prior to VEGFR TKI initiation. Differences were noted in the baseline CV risk profile according to race (Supplemental Table 3), with a higher proportion of Black RCC patients having hypertension (80.6% vs 60.5%; overall p across race < 0.01), CVA/stroke (16.4% vs 8.3%; p = 0.04) and CKD (77.6% vs 59.3%; p < 0.01), and a numerically greater proportion of prevalent heart failure (14.9% vs 8.6%; p = 0.10) and diabetes (27.3 vs 24.6%; p = 0.07). While the baseline SBP and DBP were similar between races, a greater proportion of Black patients were on anti-hypertensive medications at baseline compared to White patients (71.6% vs 47.3%; p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics (N = 987)

| Renal Cell Carcinoma (N = 793) | Thyroid Cancer (N = 194) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| AA-TKI Monotherapy (N, %) | 715 (90.2) | 190 (97.9) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| AA-TKI / IO Combination Therapy (N, %) | 78 (9.8) | 4 (2.1) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Patient Demographics (N, %) | |||

|

| |||

| Age (median, Q1-Q3) | 63 (56 – 71) | 64 (56 – 71) | 0.77 |

| Male Sex | 558 (70.4) | 92 (47.4) | <.001 |

| Race | 0.24 | ||

| White | 676 (85.2) | 163 (84.0) | |

| Black | 67 (8.4) | 15 (7.7) | |

| Other | 34 (4.3) | 14 (7.2) | |

| Tobacco Exposure | 0.001 | ||

| Current | 107 (13.5) | 14 (7.2) | |

| Former | 352 (44.4) | 74 (38.1) | |

| Never | 320 (40.4) | 105 (54.1) | |

| BMI kg/m2 (med, Q1-Q3) | 28.5 (25.0 – 32.8) | 28.7 (24.0 – 33.3) | 0.57 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 201 (25.3) | 41 (21.1) | 0.22 |

| Hypertension | 488 (61.5) | 104 (53.6) | 0.04 |

| Heart Failure | 70 (8.8) | 12 (6.2) | 0.23 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 362 (45.6) | 74 (38.1) | 0.06 |

| CVA/Stroke | 68 (8.6) | 13 (6.7) | 0.39 |

| Peripheral Arterial Disease | 94 (11.9) | 8 (4.1) | 0.002 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 475 (59.9) | 15 (7.7) | <0.001 |

| eGFR(mL/min/1.73m2) (med, Q1-Q3) | 56.8 (42.0 – 76.8) | 84.1 (67.6 – 96.7) | <0.001 |

| Prior Nephrectomy | 512 (64.6) | 8 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| Angina/CAD | 157 (19.8) | 24 (12.4) | 0.02 |

| SBP mmHg (med, Q1-Q3) | 133 (122 – 144) | 129 (119 – 140) | <0.001 |

| DBP mmHg (med, Q1-Q3) | 75 (69 – 81) | 75 (69 – 82) | 0.94 |

|

| |||

| Cancer Therapies (N, %) | |||

|

| |||

| AA-TKI | <0.001 | ||

| Axitinib | 61 (7.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Cabozantinib | 81 (10.2) | 37 (19.1) | |

| Lenvatinib | 4 (0.5) | 48 (24.7) | |

| Pazopanib | 319 (40.2) | 8 (4.1) | |

| Sorafenib | 29 (3.7) | 78 (40.2) | |

| Sunitinib | 299 (37.7) | 10 (5.2) | |

| Vandetinib | 0 (0) | 13 (6.7) | |

| Concomitant Immune Therapy | 0.81 | ||

| Atezolizumab | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Ipilimumab | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Nivolumab | 19 (2.4) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Pembrolizumab | 24 (3.0) | 3 (1.5) | |

|

| |||

| CV Medications (N, %) | |||

|

| |||

| ACEi / ARB | 338 (42.6) | 73 (37.6) | 0.21 |

| Beta Blocker | 322 (40.6) | 69 (35.6) | 0.20 |

| Calcium Channel Blocker | 244 (30.8) | 43 (22.2) | 0.02 |

| Diuretic | 263 (33.2) | 57 (29.4) | 0.31 |

| Nitrate | 38 (4.8) | 4 (2.1) | 0.09 |

| Any Anti-hypertensive | 511 (64.4) | 112 (57.7) | 0.69 |

| Oral Anticoagulant | 33 (4.2) | 9 (4.6) | 0.77 |

| Statin | 319 (40.2) | 72 (37.1) | 0.43 |

| Aspirin | 335 (42.2) | 70 (36.1) | 0.12 |

Abbreviations: AA-TKI, anti-angiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitor; ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CV, cardiovascular; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; IO, immune-oncology therapy; SBP, systolic blood pressure;

p-value comparing renal cell versus thyroid cancer

Incidence and Predictors of Early Hypertension Following VEGFR TKI Initiation

We then characterized the incidence and baseline predictors of early hypertension during the first 6 weeks following the initiation of VEGFR TKI therapy. The median number of BP measures per patient during the first 6 weeks was 2 (Q1-Q3 2 – 4). One BP measure was recorded in 22.1% of patients, while 47.8% of patients had ≥ 3 BP measures during the 6 week period. A total of 530 (53.7%) and 172 (17.4%) patients had at least one recorded SBP >140 mmHg or >160 mmHg, respectively, during this initial treatment period, including 185 (46.8%) and 46 patients (11.7%) without baseline hypertension. Similarly, a total of 212 (21.5%) and 42 (4.3%) patients had at least one recorded DBP >90 mmHg or >100 mmHg, respectively, including 84 (21.3%) and 14 patients (3.5%) without baseline hypertension. Among all patients, a total of 276 (28.0%) and 370 (37.5%) experienced an increase in SBP ≥ 20 mmHg or DBP ≥ 10 mmHg, respectively, from baseline.

The associations between baseline clinical variables and early systolic or diastolic BP changes are summarized in Table 2. On multivariable analyses, elevated baseline SBP was strongly associated with a significant mean BP increase following VEGFR TKI initiation. Similarly, Black race was associated with an increase in mean SBP from baseline on the order of 3.2 mmHg (95% CI 0.4–6.1). Notably, no significant associations were observed between sex, baseline diabetes mellitus, cancer type, or specific VEGFR TKI therapy with significant early BP changes. On evaluation of hypothesized effect modifiers, no significant interaction was observed between baseline hypertension and cancer type for early BP change outcomes. However, on multivariable analysis adjusted for all variables noted in Table 2, including baseline anti-hypertensive use, a significant interaction between baseline hypertension and race was present, with Black patients without baseline hypertension having a greater change in SBP from baseline following VEGFR TKI initiation (mean SBP change 14.4 mmHg (95% CI 8.14 – 20.7)) when compared to Black patients with baseline hypertension (mean SBP change 4.4 mmHg (95% CI 0.9 – 7.8)).

Table 2.

Association Between Baseline Clinical Variables and Early Change in Systolic or Diastolic Blood Pressure Following VEGFR TKI Initiation

| Hypertensive Outcome | Change in SBP from Baseline following VEGFR TKI Initiation | Change in DBP from Baseline following VEGFR TKI Initiation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Mean Change (95% CI) | p-value | Mean Change (95% CI) | p-value |

| Week | 1.11 (0.54 – 1.68) | <0.001 | 1.23 (0.78 – 1.68) | <0.001 |

| Age (year) | 0.08 (−0.01 – 0.16) | 0.07 | 0.01 (−0.04 – 0.05) | 0.82 |

| Race | ||||

| Non-Black | Ref | Ref | ||

| Black | 3.24 (0.41 – 6.07) | 0.02 | 0.54 (−1.22 – 2.29) | 0.55 |

| Male Sex | −0.01 (−1.97 – 1.95) | 0.99 | −0.51 (−1.91 – 0.90) | 0.48 |

| Site | ||||

| 1 | Ref | 0.57 | Ref | 0.66 |

| 2 | −1.08 (−3.44 – 1.27) | −0.59 (−2.19 – 1.00) | ||

| 3 | 0.29 (−2.05 – 2.63) | −0.74 (−2.43 – 0.95) | ||

| Baseline SBP (or DBP) 1 | 5.04 (2.93 – 7.15) | <0.001 | −7.54 (−10.13 - − 4.96) | <0.001 |

| VEGFR TKI | ||||

| Axitinib | Ref | 0.35 | Ref | 0.76 |

| Pazopanib | 0.53 (−2.58 – 3.64) | 0.36 (−1.63 – 2.34) | ||

| Sorafenib | 1.62 (−2.21 – 5.45) | −1.08 (−3.24 – 1.09) | ||

| Sunitinib | 0.41 (−2.67 – 3.49) | −0.22 (−1.84 – 1.39) | ||

| Other2 | −1.97 (−5.32 – 1.39) | 0.02 (−2.35 – 2.38) | ||

| Diabetes Mellitus | −1.83 (−4.17 – 0.51) | 0.12 | −0.48 (−2.05 – 1.09) | 0.55 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.16 (−0.91 – 3.23) | 0.27 | 0.51 (−0.97 – 2.00) | 0.50 |

| Cancer Type | ||||

| RCC | Ref | Ref | ||

| TC | 2.05 (−0.77 – 4.87) | 0.15 | −0.03 (−1.87 – 1.82) | 0.98 |

| Any HTN Med | −1.24 (−3.26 – 0.78) | 0.23 | 0.32 (−0.86 – 1.49) | 0.59 |

Each model adjusted for time (week), Age, Race, Sex, Clinical Treatment Site, Baseline SBP, VEGFR TKI type, Diabetes mellitus, Hyperlipidemia, Cancer Type, and Baseline Use of Any Anti-Hypertensive Medication.

− Baseline SBP (or DBP) covariate is baseline SBP > 140 mmHg (or DBP > 90 mmHg).

− Other VEGFR TKI category includes cabozantinib, lenvatinib, vandetinib

Abbreviations: DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HTN, hypertension; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, thyroid carcinoma; VEGFR- TKI, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Incidence and Predictors of First Major Adverse CV Events Following VEGFR TKI Initiation

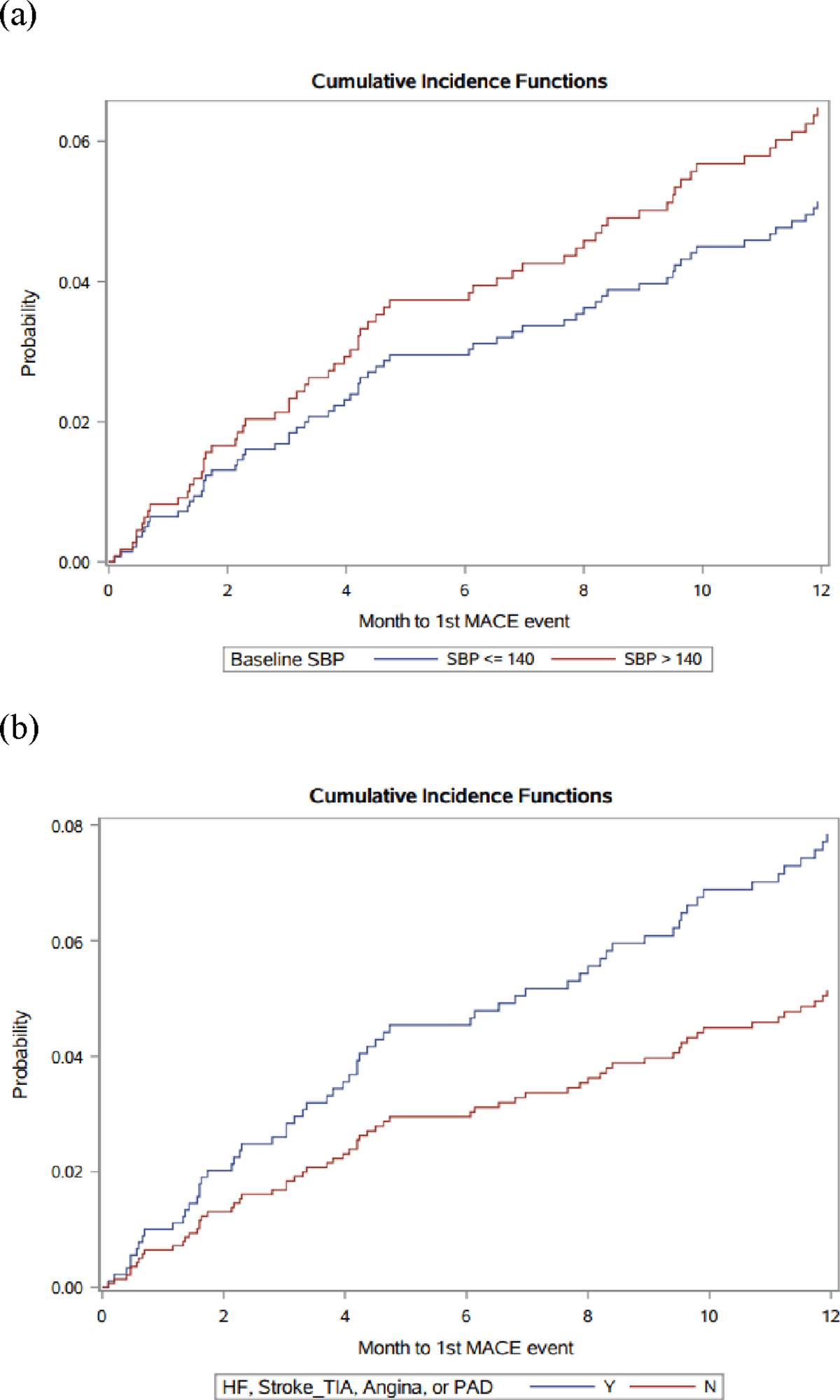

We next evaluated whether baseline patient-, treatment-, and disease-related factors were associated with increased risk for major adverse CV outcomes following initiation of VEGFR TKI therapy. There was a total of 147 MACE over a median follow-up time of 19 months and a maximum follow-up time of 158 months, which included first occurrences of 71 incident HF events (48.3% of MACE outcomes), 49 incident CVA events (33.3% of MACE), and 27 acute coronary events or coronary revascularizations (18.4% of MACE). The cumulative incidence of the first MACE at one and two years was 6.9% and 10.0%, respectively, and 68 of 147 observed events (46.3%) occurred within 1 year of VEGFR TKI initiation. The median time to a MACE was 14 months (Q1-Q3 4 – 31). The associations between baseline clinical variables and incident MACE following VEGFR TKI initiation are summarized in Table 3. Using a competing risks modeling framework with Fine & Gray analysis, baseline SBP ≥ 140 mmHg (subdistribution HR 1.41; 95% CI 1.00 – 1.98) and history of CV disease (subdistribution HR 1.62; 95% CI 1.15 – 2.28) were each associated with MACE outcomes in univariable analyses (Figures 1A and 1B). However, no significant associations between CV disease, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, or male sex and MACE outcomes were observed on multivariable analysis accounting for the competing risk of death (Table 3). Similarly, there were no significant associations between CV disease or CV risk factors and MACE outcomes in stratified analyses by cancer type (Supplemental Table 4).

Table 3.

Association Between Baseline Clinical Variables and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events Following VEGFR TKI Initiation

| Subdistribution Hazards | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||

| Covariate | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Age (year) | 1.02 (1.00 – 1.03) | 1.01 (1.00 – 1.03) | 0.15 |

| Race | |||

| White | Ref | Ref | |

| Black | 0.98 (0.54 – 1.81) | 1.16 (0.63 – 2.14) | 0.63 |

| Other | 1.25 (0.63 – 2.47) | 1.96 (0.96 – 4.01) | 0.06 |

| Male Sex | 0.83 (0.59 – 1.17) | 0.85 (0.60 – 1.20) | 0.35 |

| Site | |||

| 1 | Ref | Ref | |

| 2 | 1.58 (1.06 – 2.34) | 1.66 (1.07 – 2.58) | 0.02 |

| 3 | 2.18 (1.43 – 3.31) | 2.58 (1.60 – 4.13) | <0.001 |

| Renal Cell Carcinoma | 0.93 (0.62 – 1.37) | 0.76 (0.50 – 1.14) | 0.18 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 1.19 (0.82 – 1.73) | 1.04 (0.71 – 1.52) | 0.85 |

| Baseline SBP > 140 mmHg | 1.41 (1.00 – 1.98) | 1.26 (0.89 – 1.79) | 0.19 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.34 (0.96 – 1.87) | 1.03 (0.71 – 1.50) | 0.88 |

| Cardiovascular Disease | 1.62 (1.15 – 2.28) | 1.41 (0.95 – 2.09) | 0.09 |

The association between baseline characteristics and MACE was evaluated using a competing risk framework to account for the risk of death. Gray’s test and estimates of subdistribution HRs were performed in order to evaluate prognostic factors associated with MACE incidence, accounting for the risk of death in this advanced cancer population.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure; VEGFR TKI, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Figure 1.

Cumulative Incidence of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events Following VEGFR TKI Initiation, Stratified by (a) Baseline Systolic Blood Pressure and (b) Baseline Cardiovascular Disease

(a) Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence Function of MACE, by Baseline SBP > 140 mmHg (subdistribution HR 1.41 (95% CI 1.00 – 1.98)

(b) Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence Function of MACE, by Baseline CV Disease (subdistribution HR 1.62 (95% CI 1.15 – 2.28)

Association Between On-Treatment BP Change and Adverse CV Events

In an exploratory analysis, we next sought to evaluate the association between early changes in ‘on-treatment BP’ and subsequent risk of MACE in order to inform potential optimal BP targets for mitigating CV risk in patients initiating VEGFR TKI therapy. A total of 304 patients (30.8%) experienced a mean SBP >140 mmHg, and 321 patients (32.5%) experienced a mean DBP >80 mmHg within 4 weeks of VEGFR TKI initiation. Subdistribution HR competing risk analysis evaluating the association between early on-treatment BP change during the initial 4 weeks of VEGFR TKI therapy and MACE outcomes are summarized in Table 4. Early significant elevations of SBP or DBP during the first 4 weeks following VEGFR TKI initiation were not significantly associated with adverse CV outcomes within 2 years (subdistribution HRs 0.99 (95% CI 0.60 – 1.65) and 1.55 (0.76 – 3.18) for on-treatment elevations of SBP > 20 mmHg and DBP > 20 mmHg, respectively).

Table 4.

Association Between Initial On-Treatment Systolic or Diastolic Blood Pressure Control and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Event During First Year Following VEGFR TKI Initiation

| Subdistribution HR (95% CI) | p-value | Subdistribution HR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On-Treatment SBP Change (mmHg)* | On-Treatment DBP Change (mmHg)* | ||||

| <10 | Ref | <10 | Ref | ||

| 10 – 20 | 0.79 (0.45 – 1.38) | 0.41 | 10 – 20 | 1.29 (0.79 – 2.10) | 0.31 |

| >20 | 0.99 (0.60 – 1.65) | 0.98 | >20 | 1.55 (0.76 – 3.18) | 0.23 |

Model adjusted for Age, Race, Sex, Cancer Type, Baseline Cardiovascular Disease, and Baseline Use of Any Anti-Hypertensive Medication

Change between baseline mean BP and peak BP during first 4 weeks following VEGFR TKI initiation

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, hazard ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure; VEGFR TKI, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Predictors of Overall Survival Following VEGFR TKI Initiation

A total of 592 patients (60.0%) died over a maximum follow-up time of 158 months. Over a median follow-up time of 19 months following VEGFR TKI initiation, the median time to death was 13 months (Q1-Q3 5.5 – 27). The 1-year and 2-year all-cause mortality rates following VEGFR TKI initiation were 26.7% and 42.5%, respectively. Table 5 demonstrates the associations between baseline clinical variables and overall survival following VEGFR TKI initiation. Within this cohort, patients with RCC had inferior survival compared to patients with TC (HR 1.61, 95% CI [1.22–2.13], p<0.001). Consistent with established prognostic factors for advanced RCC, a history of prior nephrectomy, which typically indicates initial presentation with clinically localized disease or candidacy for cytoreductive nephrectomy, was associated with improved survival following VEGFR TKI initiation (HR 0.64, [95% CI 0.53–0.79], p<0.001). (20) Black race was associated with inferior survival (HR 1.40, [95% CI 1.04–1.89], p = 0.03). However, known CV risk factors (hypertension, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) and prevalent CV disease prior to VEGFR TKI initiation were not significantly associated with overall survival outcomes.

Table 5.

Association Between Baseline Clinical Variables and Overall Survival Following VEGFR TKI Initiation

| Covariate | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 1.01 (1.00 – 1.02) | 0.13 |

| Race | ||

| White | Ref | |

| Black | 1.40 (1.04 – 1.89) | 0.03 |

| Other | 0.85 (0.53 – 1.37) | 0.51 |

| Male Sex | 0.99 (0.82 – 1.19) | 0.88 |

| Site | ||

| 1 | Ref | |

| 2 | 1.02 | 0.85 |

| 3 | 1.34 (1.07 – 1.67) | 0.01 |

| eGFR | 1.00 (0.99 – 1.01) | 0.97 |

| Prior Nephrectomy | 0.64 (0.53 – 0.79) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.91 (0.75 – 1.11) | 0.37 |

| Cardiovascular Disease | 1.05 (0.85 – 1.29) | 0.66 |

| BMI ≥ 30 (kg/m2) | 0.79 (0.66 – 0.95) | 0.01 |

| Cancer Type | ||

| Thyroid | Ref | |

| RCC | 1.61 (1.22 – 2.13) | <0.001 |

Model adjusted for age, race, gender, treatment site, eGFR, history of prior nephrectomy, hypertension, CV disease, BMI (categorical > 30 kg/m2), and cancer type.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratio; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; VEGFR TKI, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter retrospective cohort study of patients receiving cancer care across 3 large US health systems, we first evaluated the baseline prevalence and incidence of early hypertension and MACE outcomes following VEGFR TKI therapy initiation for the most common prescription indications, advanced RCC or TC malignancies. In this ‘real-world’, non-clinical trial population, the baseline prevalence of CV disease and traditional CV risk factors, in particular hypertension, was notably high, with more than half of patients diagnosed with hypertension and prescribed anti-hypertensive agents. In addition, adverse CV events, including HF and CVA events, were common (overall occurring in 14.9% of patients) and frequently occurred early (46.3% of events occurred within 1 year of VEGFR TKI initiation). When evaluating the association between baseline patient-, treatment-, and disease-related factors and early hypertensive and adverse CV outcomes, a key finding from our analyses was that baseline hypertension and Black race were the primary clinical factors associated with greater risk of early BP increases on VEGFR TKI therapies. These findings lend insight into the identification of high risk subgroups who may be more likely to experience significant acute hypertension with the initiation of VEGFR TKIs.

An improved understanding of the clinical impact of this early significant hypertension and other traditional CV risk factors on adverse CV outcomes, particularly within an advanced cancer population at high risk for cancer-related mortality, is key to informing the optimal management of VEGFR TKI treatment-related hypertension. Advanced cancer patients, in particular RCC patients, are at increased risk for competing CV morbidity and mortality, owing to the shared risk factors between cancer and CV disease and the known cancer therapy toxicity profiles. (6) In our analyses, elevated baseline SBP > 140 mmHg and CV disease were associated with MACE on univariable analysis, in keeping with previous published studies of VEGFR TKI therapies indicating a prognostic association between baseline hypertension and prevalent CV events with MACE. (15) However, in our study cohort, no baseline clinical factors, including traditional CV risk factors, were associated with MACE following VEGFR TKI initiation in adjusted analyses. Although a MACE incidence of 10% at 2 years in our cohort suggests CV morbidity in this population is important, cancer disease-related risk in this advanced cancer population remained a significant competing risk with a median survival of 13 months, most likely secondary to progressive malignancy. Similarly, as hypertension is a known risk factor for adverse CV outcomes, we had hypothesized that treatment-related early hypertensive toxicity on VEGFR TKI therapy would contribute to VEGFR TKI related MACE, including HF and CVA. (21) However, in our study, early ‘on-treatment’ BP elevations were not associated with MACE during the first two years following VEGFR TKI initiation. As such, while prior randomized clinical trials have demonstrated the benefits of intensive BP control (to a target systolic BP (SBP) <120 mmHg) for decreasing MACE and all-cause mortality in non-cancer populations, the appropriate BP targets in this unique cancer population remain an important unanswered question. (22) In particular, while our analyses indicated that early changes in BP (within 4 weeks of VEGFR TKI initiation) were not associated with MACE, the association between more sustained BP elevations while on VEGFR TKI therapy and adverse CV outcomes in this population remains uncertain.

Taken together, these findings may inform several important aspects of the real-world clinical management of early hypertensive toxicity in advanced cancer patients initiating VEGFR TKIs. As hypertension is a well-established toxicity of VEGFR TKI therapies, eligibility criteria for clinical trials and resulting regulatory product labels encourage adequate BP control prior to treatment initiation. (23) However, the non-trial population included in this study cohort reflects the variable baseline BP control common to RCC and TC patients initiating VEGFR TKIs in routine clinical practice, in which one-third of patients initiating VEGFR TKI therapy had a mean SBP > 140 mmHg during the 3 months prior to treatment initiation. Moreover, our findings indicate that elevated baseline SBP is the strongest factor associated with the development of clinically significant acute changes in BP following VEGFR TKI initiation, even when accounting for the baseline use of anti-hypertensive medications. These findings underscore the current under-management of this modifiable risk factor and the relevance of adequate BP control prior to VEGFR TKI initiation in order to mitigate early on-treatment hypertensive toxicity. (8, 14) These findings provide evidence to support the cardio-oncology consensus recommendations from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) which emphasize recognition and management of hypertension prior to therapy initiation. (24) In addition, while BP elevations on VEGFR TKI therapy have been associated with improved cancer outcomes, early ‘on-treatment’ significant BP elevations may often contribute to VEGFR TKI cessation, dose interruption, or reduction (given the known association between poor BP control and adverse CV outcomes in non-cancer populations). However, our findings indicate that such acute BP elevations were not associated with MACE, and may emphasize that priority should be given to continuing VEGFR TKI therapy in the early treatment period in order to maximize cancer treatment, with parallel efforts to carefully manage and control BP, consistent with the concept of permissive cardiotoxicity. (25) These findings similarly support recent ESC recommendations, which state a “goal to continue VEGFi treatment for as long as possible with initiation or optimization of CV treatment if indicated.” (24) However, the potential longer-term CV effects of such permissive hypertension during more sustained BP elevations on VEGFR TKI therapy require further evaluation.

An advanced cancer population treated with palliative intent systemic therapies represents a unique setting in which to assess and manage comorbid CV risks. Importantly, the highly variable clinical behavior of advanced RCC and TC, with some ‘favorable-risk’ patients experiencing prolonged survival outcomes, is well-established. (26) Furthermore, contemporary treatment regimens combining VEGFR TKIs with other cardiotoxic agents, such as ICI therapy, have significantly improved prognosis in this population, now with a median survival approaching 4 years. (27) Consequently, this increased survival may also result in greater clinical significance of CV comorbidities in the longer term for some patients. As such, our findings overall indicate that traditional CV risk assessment tools may not broadly apply within this cancer population, and that cancer-specific CV risk assessments, incorporating both cancer-related prognostic factors and CV-related patient factors (in particular elevated baseline SBP > 140 mmHg and prevalent CV disease) may be necessary to optimally identify patients at highest risk of MACE following VEGFR TKI therapy.

An additional notable finding from our study was the association between self-identified Black race and both hypertension and worse survival outcomes. Black race was associated with inferior overall survival, as well as a greater change from baseline in BP among non-hypertensive patients, following VEGFR TKI initiation on adjusted analyses. Similar inferior clinical outcomes for Black patients relative to White patients receiving VEGFR TKI therapies have been reported. (28) While reasons for this difference remain unclear, the higher proportion of baseline comorbidities among Black patients, as well as potential disparities in care, including less aggressive anti-hypertensive management or undertreated baseline hypertension, may contribute to observed differences in hypertensive outcomes on VEGFR TKI therapy and warrant further investigation. These findings again highlight patient populations that may be particularly vulnerable and the need for a targeted, multidisciplinary approach to improve care.

Our study had limitations. First, while representing a large multi-institutional cohort of cancer patients, potential limitations in power may have resulted in a lack of a detectable association between baseline CV risk factors (such as diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, elevated BMI) and adverse hypertensive or MACE outcomes. Second, although the study cohort was restricted to patients receiving longitudinal oncologic care at one of the study institutions, CV risk factors, diagnoses, and medications initiated at outside health systems may not have been captured resulting in a risk of misclassification. Similarly, the use of ICD codes as documented in the EHR medical history may have resulted in misclassification in baseline and/or incident MACE outcomes. For example, although incident HF was only included as a MACE if listed as a primary inpatient diagnosis code among patients with baseline HF, this may have overestimated the true incidence of HF following VEGFR TKI initiation. We also did not have cause of death. Third, we were unable to account for the potential effects of anti-hypertensive or VEGFR TKI dose modifications during the initial 6 weeks following TKI initiation. Therefore, although our study findings indicate that patients with early increases in BP may benefit from VEGFR TKI continuation, future studies are needed to evaluate the effect of early TKI dose modifications on longer-term BP changes and/or MACE, as we did not have detailed longitudinal BP data over an extended follow-up time. Fourth, while ESC guidelines recommend ambulatory/home BP monitoring on VEGFR TKI therapy to minimize ‘white coat’ hypertension and variations in measurement technique, our study relied on EHR-derived BP measures obtained in a clinic setting. (24) Finally, the median survival time in our cohort was 13 months, likely related to the low use of ICIs with VEGFR TKIs given the study time period (2008–2020) and evolving practice patterns. With more recent significant improvements in survival outcomes, the prospect for competing CV risk acquires increasing clinical relevance. Strengths of this analysis include the large study population, across multiple regional health systems, different cancer types, and diverse VEGFR TKI exposures. Additionally, the included health systems represent regional health networks with integrated EHRs across medical disciplines and community / academic treatment sites.

Our study demonstrates that hypertension and CV morbidities are highly prevalent among patients initiating VEGFR TKI therapies, and that baseline hypertension and Black race represent the primary clinical factors associated with VEGFR TKI related early significant hypertension, suggesting that there is a need for greater awareness in the management and care of these subgroups. While adverse CV events are common, occur early in this advanced cancer population, and may impart significant medical and quality of life implications with steadily improving long-term cancer outcomes, our findings suggest that early BP elevations are not associated with MACE in this population, and that unique cancer-specific CV risk assessment tools are needed for patients treated with VEGFR TKIs. Further evaluations of the level of ‘optimal’ BP control, and its association with cancer, CV, and quality of life / symptom outcomes are warranted. A cluster randomized trial evaluating the feasibility of achieving intensive versus standard BP control in patients initiating contemporary VEGFR TKI-based regimens (with or without ICI therapy) is currently ongoing (NCT 04467021).

Supplementary Material

Funding Support:

This study was supported by Grant 5-R34-HL-146927-02 (BK, KM) and NCI UGI CA 189828-01 (BK).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant conflicts, including financial interests, activities, relationships, and affiliations.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Li W, Croce K, Steensma DP, et al. 2015. Vascular and metabolic implications of novel targeted cancer therapies: Focus on kinase inhibitors. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 66 : 1160–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brose MS. 2016. Sequencing of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in progressive differentiated thyroid cancer. Clinical advances in hematology & oncology. 14 : 7–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choueiri TK, Powles T, Burotto M, et al. 2021. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. New Engl. J. Med. 384 : 829–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motzer R, Alekseev B, Rha S-, et al. 2021. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or everolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma. New Engl. J. Med. 384 : 1289–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castro DV, Malhotra J, Meza L, et al. 2022. How to treat renal cell carcinoma: The current treatment landscape and cardiovascular toxicities. JACC: CardioOncology. 4 : 271–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narayan V, Ky B. 2018. Common cardiovascular complications of cancer therapy: Epidemiology, risk prediction, and prevention. Annu Rev Med 69 : 97–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen D-, Liu J-, Tseng C-, et al. 2022. Major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with renal cell carcinoma treated with targeted therapies. JACC: CardioOncology. 4 : 223–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall PS, Harshman LC, Srinivas S, et al. 2013. The frequency and severity of cardiovascular toxicity from targeted therapy in advanced renal cell carcinoma patients. JACC Heart Fail. 1 : 72–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlumberger MTM 2015. Lenvatinib versus placebo in radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 372 : 621–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rini BI, Cohen DP, Lu DR, et al. 2011. Hypertension as a biomarker of efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 103 : 763–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rini BI, Schiller JH, Fruehauf JP, et al. 2011. Diastolic blood pressure as a biomarker of axitinib efficacy in solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 17 : 3841–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wirth LJTM 2018. Treatment-emergent hypertension and efficacy in the phase 3 study of (E7080) lenvatinib in differentiated cancer of the thyroid (SELECT). Cancer. 124 : 2365–2372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the eighth joint national committee (JNC 8). JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 311 : 507–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamnvik O-R, Choueiri TK, Turchin A, et al. 2015. Clinical risk factors for the development of hypertension in patients treated with inhibitors of the VEGF signaling pathway. Cancer. 121 : 311–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vallerio P, Orenti A, Tosi F, et al. 2022. Major adverse cardiovascular events associated with VEGF-targeted anticancer tyrosine kinase inhibitors: A real-life study and proposed algorithm for proactive management. ESMO Open. 7 (1) : [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogden LG, He J, Lydick E, et al. 2000. Long-term absolute benefit of lowering blood pressure in hypertensive patients according to the JNC VI risk stratification. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex.1979). 35 : 539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, et al. 2002. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: A meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. The Lancet (British edition). 360 : 1903–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maitland ML, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. 2010. Initial assessment, surveillance, and management of blood pressure in patients receiving vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathway inhibitors. JNCI : Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 102 : 596–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. 2009. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 150 : 604–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heng DYC, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. 2009. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: Results from a large, multicenter study. J. Clin. Oncol. 27 : 5794–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Catino A, Hubbard R, Chirinos J, et al. 2018. Longitudinal assessment of vascular function with sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Circ Heart Fail. 11 : e004408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright JT, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. 2015. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. New Engl. J. Med. 373 : 2103–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U S Food and Drug Administration. 2011. Sunitinib prescribing information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/021938s13s17s18lbl.pdf

- 24.Lyon AR, López-Fernánde T, Couch LS, et al. 2022. 2022 ESC guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European hematology association (EHA), the European society for therapeutic radiology and oncology (ESTRO) and the international cardio-oncology society (IC-OS). Eur. Heart J. 43 : 4229–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porter C, Azam TU, Mohananey D, et al. 2022. Permissive cardiotoxicity: The clinical crucible of cardio-oncology. JACC: CardioOncology. 4 : 302–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ko JJ, Xie W, Kroeger N, et al. 2015. The international metastatic renal cell carcinoma database consortium model as a prognostic tool in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma previously treated with first-line targeted therapy: A population-based study. The lancet oncology. 16 : 293–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rini B PR. 2021. Pembrolizumab (pembro) plus axitinib (axi) versus sunitinib as first-line therapy for advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC): Results from 42-month follow-up of KEYNOTE-426.. J Clin Oncol. 39 ((suppl 15; abstr 4500). doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.4500) (Abstr.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bossé D, Xie W, Lin X, et al. 2020. Outcomes in black and white patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with first-line tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Insights from two large cohorts. JCO global oncology. 6 : 293–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.