Abstract

Background

Studies suggest a harmful pharmacogenomic interaction exists between short leukocyte telomere length (LTL) and immunosuppressants in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). It remains unknown if a similar interaction exists in non-IPF interstitial lung disease (ILD).

Methods

A retrospective, multicentre cohort analysis was performed in fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (fHP), unclassifiable ILD (uILD) and connective tissue disease (CTD)-ILD patients from five centres. LTL was measured by quantitative PCR for discovery and replication cohorts and expressed as age-adjusted percentiles of normal. Inverse probability of treatment weights based on propensity scores were used to assess the association between mycophenolate or azathioprine exposure and age-adjusted LTL on 2-year transplant-free survival using weighted Cox proportional hazards regression incorporating time-dependent immunosuppressant exposure.

Results

The discovery and replication cohorts included 613 and 325 patients, respectively. In total, 40% of patients were exposed to immunosuppression and 22% had LTL <10th percentile of normal. fHP and uILD patients with LTL <10th percentile experienced reduced survival when exposed to either mycophenolate or azathioprine in the discovery cohort (mortality hazard ratio (HR) 4.97, 95% CI 2.26–10.92; p<0.001) and replication cohort (mortality HR 4.90, 95% CI 1.74–13.77; p=0.003). Immunosuppressant exposure was not associated with differential survival in patients with LTL ≥10th percentile. There was a significant interaction between LTL <10th percentile and immunosuppressant exposure (discovery pinteraction=0.013; replication pinteraction=0.011). Low event rate and prevalence of LTL <10th percentile precluded subgroup analyses for CTD-ILD.

Conclusion

Similar to IPF, fHP and uILD patients with age-adjusted LTL <10th percentile may experience reduced survival when exposed to immunosuppression.

Tweetable abstract

Fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis and unclassifiable ILD patients who have age-adjusted leukocyte telomere length <10th percentile may experience reduced survival when exposed to immunosuppression, similar to IPF patients https://bit.ly/3DJDLYg

Introduction

The interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) are a diverse group of inflammatory and fibrotic disorders that often require pharmacological therapy to mitigate progressive loss of lung function. The initial treatment choice is primarily dictated by the ILD subtype. Antifibrotics are the preferred treatment for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) [1, 2], while immunosuppressants have been the mainstay for non-IPF ILDs, including fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (fHP), unclassifiable ILD (uILD) and connective tissue disease (CTD)-ILD. Inaccurate ILD classification can result in suboptimal management for some patients; therefore, biomarkers that inform treatment selection irrespective of ILD subtype are needed.

Telomeres are 6-nucleotide repeats at ends of chromosomes that normally shorten with cellular replication and ageing. Telomere dysfunction has been inexorably linked with ILD development and disease trajectory [3–12]. Short leukocyte telomere length (LTL) has been found in 13–62% of patients with various ILDs and is consistently associated with reduced survival and rapid progression [13–21]. For certain ILDs, there may also exist a pharmacogenomic relationship between short LTL and immunosuppressive therapies. We previously reported that historical use of immunosuppression was associated with worse survival for IPF patients with short age-adjusted LTL [21]. We also described differential survival for fHP patients treated with mycophenolate when stratified by telomere quartiles [17]. This current study seeks to expand these findings by examining a generalisable age-adjusted LTL percentile measurement across multiple cohorts, additional ILD subtypes and other immunosuppressive therapies while accounting for potential immortal time bias in previous analyses [22].

In this observational study, we examined fHP, uILD and CTD-ILD patients from five US academic ILD centres split into discovery and replication cohorts. Within each cohort, we explored the association between time-dependent exposure to mycophenolate or azathioprine and transplant-free survival in non-IPF ILD patients stratified by age-adjusted LTL in percentiles. We also assessed the longitudinal forced vital capacity (FVC) trajectory across immunosuppressant exposure and LTL groups.

Methods

Study populations

Patients with fHP, uILD and CTD-ILD were identified from the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW; 2003–2019), University of California San Francisco (UCSF; 2004–2017), University of California Davis (UCD; 2013–2017), University of Chicago (Chicago; 2001–2015) and Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC; 2019–2020). The institutional review boards for each centre approved this study. All patients provided written inform consent and a blood sample for research LTL measurement. LTL was independently assessed at UTSW/CUMC or UCSF, which comprised the discovery and replication cohorts. A portion of this cohort with fHP has been previously described [17].

Eligible patients had non-IPF ILD diagnoses conferred through multidisciplinary discussion at each centre. Patients were excluded if baseline FVC and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) measurements were unavailable, chest high-resolution computed tomography did not demonstrate fibrosis per centre radiologist, were exposed to immunosuppressants (mycophenolate, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide or rituximab) or antifibrotics (pirfenidone or nintedanib) before blood collection for LTL measurement, or were exposed to antifibrotics before immunosuppressants. Patients were grouped into immunosuppressant exposed (initiated on mycophenolate or azathioprine within 2 years of blood collection) or unexposed. Prednisone exposure was variable and largely coincided with other immunosuppressant exposure; therefore, patients were not excluded based on prednisone therapy to preserve sample size. Patients subsequently exposed to pirfenidone or nintedanib were censored at initiation of antifibrotic therapy.

Leukocyte telomere length

Genomic DNA was collected from leukocytes using Autopure LS (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA; UTSW and CUMC), Gentra Puregene (Qiagen; UCSF and UCD) and FlexiGene DNA kit (Qiagen; Chicago). All LTLs were measured using a similar quantitative PCR (qPCR) methodology at either UTSW/CUMC (discovery cohort) or UCSF (replication cohort) as previously reported [19, 21, 23, 24]. The UTSW and CUMC protocol was identical and performed by the same laboratory, so the data were combined. Age-adjusted LTL was calculated by comparing observed to expected telomere length (supplementary methods) and dichotomised for comparative analyses: <10th and ≥10th percentile of the reference population. Patients who underwent LTL measurement at both sites were included in the replication cohort only.

Statistical analysis

Groups were compared using Chi-squared, Fisher's exact test, t-test, Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test or one-way ANOVA, where appropriate. Relationships between continuous variables were examined using Pearson's correlation.

Given the observational nature of the study, inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using propensity scores was used to minimise indication bias and estimate the average treatment effect of immunosuppression across the entire cohort (supplementary methods). Propensity scores were generated using multivariable logistic regression to estimate the conditional probability of either mycophenolate or azathioprine exposure, adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, family history of ILD, smoking status, baseline FVC and DLCO % pred, radiographic usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), prednisone exposure, ILD diagnosis, and centre. Weights were calculated by taking the inverse of the propensity score for immunosuppressant-exposed patients and one minus the inverse of the propensity score for the unexposed patients; the weights were used to determine each patient's contribution to a pseudo-population with balanced covariate distributions across treatment groups [25]. Variables with standardised mean difference (SMD) >0.15 after weighting were considered unbalanced and included as covariates in outcome models. Given that prednisone exposure may similarly impact outcomes and is commonly used for non-IPF ILDs, a separate IPTW procedure was conducted for prednisone monotherapy using similar methods.

The primary aim was to determine if immunosuppression was associated with differential 2-year transplant-free survival, defined as time from blood collection for LTL measurement to death or transplant, in patients stratified by the age-adjusted LTL 10th percentile. We constructed weighted multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models with robust variance estimation (supplementary methods). Immunosuppressant exposure was treated as a time-dependent covariate to address immortal time bias, whereby patients initiated on mycophenolate or azathioprine during follow-up were considered unexposed until drug start date. Models were adjusted for centre, radiographic honeycombing and ILD diagnosis given residual imbalances after weighting and survival differences across diagnoses and presence of honeycombing [26, 27]. We assessed the pharmacogenomic interaction using an interaction term for LTL group and immunosuppressant exposure. The discovery and replication cohorts were analysed separately, then a meta-analysis across cohorts was performed using a random effects model. There was no evidence of non-proportional hazards which were examined by plotting Schoenfeld residuals versus time.

Multiple secondary survival analyses were performed. First, survival was assessed for each non-IPF ILD diagnosis using within-diagnoses meta-analysis of the discovery and replication cohorts. Second, we examined survival associations between immunosuppressant exposure and LTL percentile as a continuous variable. Third, we restricted the exposed cohort to patients initiated on immunosuppressants within 1 year of blood collection and who had >3 months of exposure. Lastly, survival associations were individually assessed for mycophenolate and azathioprine. For this analysis, the propensity scores and IPTWs were calculated for each medication separately. For patients exposed to both medications sequentially, the first immunosuppressant drug was considered primary.

Longitudinal FVC trajectory was analysed using joint models incorporating survival and linear mixed effects submodels (supplementary methods) [28, 29]. Both submodels were constructed similar to the primary survival model, including terms for immunosuppressant exposure, LTL group, centre, radiographic honeycombing and diagnosis. The linear mixed effects submodel also included terms for FVC, time and an interaction term for FVC, time and immunosuppressant exposure. Immunosuppressant-exposed patients were included if they had at least two FVC measurements during exposure within 2 years of blood collection, while unexposed patients were included if they had at least two FVC measurements within 2 years of blood collection. p-values <0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed using R version 4.2.0 (www.r-project.org).

Results

Study cohorts

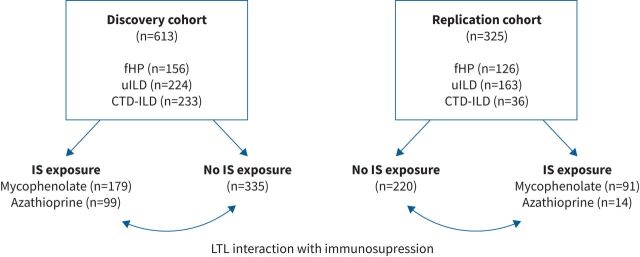

Of the 1332 non-IPF ILD patients identified across five centres, 938 met eligibility criteria, including 613 and 325 in the discovery and replication cohorts, respectively (figure 1 and supplementary figure E1). CTD-ILD was the most common ILD subtype in the discovery cohort followed by uILD and fHP, while uILD was more common in the replication cohort followed by fHP and CTD-ILD (tables 1 and 2). Among the CTD-ILDs, rheumatoid arthritis ILD and scleroderma-related ILD were the most common diagnoses in both cohorts. The distribution of radiographic patterns and honeycombing differed by ILD subtype (supplementary figure E2).

FIGURE 1.

STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) diagram. fHP: fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis; uILD: unclassifiable interstitial lung disease; CTD-ILD: connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease; IS: immunosuppressant; LTL: leukocyte telomere length.

TABLE 1.

Unweighted and weighted discovery cohort patient characteristics stratified by immunosuppressant (IS) exposure

| Discovery cohort | Weighted discovery cohort | ||||||

| IS exposed (n=278) | IS unexposed (n=335) | p-value | IS exposed (n=286) | IS unexposed (n=332) | p-value | SMD | |

| Centre | <0.01 | 0.62 | 0.13 | ||||

| UTSW | 171 (62) | 157 (47) | 138 (48) | 171 (51) | |||

| UCSF | 34 (12) | 51 (15) | 56 (19) | 50 (15) | |||

| Chicago | 69 (25) | 119 (36) | 88 (31) | 105 (32) | |||

| UCD | |||||||

| CUMC | 4 (1) | 8 (2) | 4 (2) | 6 (2) | |||

| ILD diagnosis | 0.10 | 0.91 | 0.04 | ||||

| fHP | 75 (27) | 81 (24) | 73 (25) | 83 (25) | |||

| CTD-ILD# | 114 (41) | 119 (36) | 107 (37) | 131 (39) | |||

| uILD | 89 (32) | 135 (40) | 106 (37) | 118 (36) | |||

| Age, years | 60±11 | 63±12 | 0.01 | 62±10 | 62±12 | 0.93 | 0.01 |

| Male | 113 (41) | 129 (39) | 0.65 | 109 (38) | 128 (39) | 0.93 | 0.01 |

| Ethnicity/race | 0.58 | 0.76 | 0.03 | ||||

| White | 204 (73) | 226 (68) | 196 (68) | 232 (70) | |||

| African American | 37 (13) | 59 (18) | 43 (15) | 59 (18) | |||

| Hispanic | 27 (10) | 37 (11) | 30 (10) | 32 (10) | |||

| Asian | 9 (3) | 12 (4) | 17 (6) | 9 (3) | |||

| Other¶ | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | |||

| Ever-smoker | 130 (47) | 178 (53) | 0.14 | 151 (53) | 172 (52) | 0.81 | 0.02 |

| Family history of ILD | 32 (12) | 31 (9) | 0.43 | 26 (9) | 31 (9) | 0.94 | 0.01 |

| Lung function | |||||||

| FVC % pred | 62±17 | 69±20 | <0.01 | 66±18 | 66±19 | 0.97 | <0.01 |

| DLCO % pred | 42±19 | 48±20 | <0.01 | 45±19 | 45±20 | 0.77 | 0.03 |

| Radiographic features | |||||||

| UIP+ | 54 (19) | 78 (23) | 0.29 | 61 (21) | 72 (22) | 0.92 | 0.01 |

| Honeycombing | 75 (27) | 121 (36) | 0.02 | 78 (27) | 112 (33) | 0.15 | 0.11 |

| IS therapy | |||||||

| Mycophenolate | 179 (64) | 184 (64) | |||||

| Azathioprine | 99 (36) | 102 (36) | |||||

| IS exposure, years | 1.7 (0.7–2.0) | 1.9 (0.6–2.0) | |||||

| Prednisone | 231 (83) | 143 (43) | <0.01 | 169 (60) | 201 (61) | 0.77 | 0.03 |

| LTL | |||||||

| LTL <10th percentile | 57 (21) | 65 (19) | 0.81 | 51 (17) | 65 (20) | 0.52 | 0.06 |

| Age-adjusted LTL | −0.1 (−0.3–0.1) | −0.1 (−0.3–0.1) | 0.39 | −0.1 (−0.2–0.1) | −0.1 (0.3–0.1) | 0.55 | 0.06 |

| Follow-up, years | 2.0 (1.4–2.0) | 2.0 (1.3–2.0) | 0.73 | 2.0 (1.3–2.0) | 2.0 (1.8–2.0) | 0.32 | <0.01 |

| Outcome | |||||||

| Death within 2 years | 42 (15) | 31 (9) | 0.04 | 41 (14) | 29 (9) | 0.06 | 0.18 |

| Transplant within 2 years | 15 (5) | 5 (2) | 0.01 | 11 (4) | 4 (1) | 0.02 | 0.17 |

Data are presented as n (%), mean±sd or median (interquartile range). SMD: standardised mean difference; UTSW: University of Texas Southwestern; UCSF: University of California San Francisco; Chicago: University of Chicago; UCD: University of California Davis; CUMC: Columbia University Medical Center; ILD: interstitial lung disease; fHP: fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis; CTD: connective tissue disease; uILD: unclassifiable ILD; FVC: forced vital capacity: DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia; LTL: leukocyte telomere length. #: CTD-ILD diagnoses: scleroderma n=63, rheumatoid arthritis n=69, inflammatory myositis n=36, mixed CTD n=32, Sjögren's syndrome n=24, systemic lupus erythematosus n=10; ¶: other ethnicity/race: unknown n=2; +: radiographic UIP incudes definite UIP.

TABLE 2.

Unweighted and weighted replication cohort patient characteristics stratified by immunosuppressant (IS) exposure and leukocyte telomere length (LTL) group

| Replication cohort | Weighted replication cohort | ||||||

| IS exposed (n=105) | IS unexposed (n=220) | p-value | IS exposed (n=112) | IS unexposed (n=217) | p-value | SMD | |

| Cohort | <0.01 | 0.24 | 0.28 | ||||

| UTSW | |||||||

| UCSF | 50 (48) | 120 (55) | 74 (66) | 117 (54) | |||

| Chicago | 14 (13) | 56 (26) | 14 (13) | 47 (22) | |||

| UCD | 41 (39) | 44 (20) | 24 (21) | 53 (24) | |||

| CUMC | |||||||

| ILD diagnosis | <0.01 | 0.70 | 0.13 | ||||

| fHP | 49 (47) | 77 (35) | 36 (32) | 84 (39) | |||

| CTD-ILD# | 18 (17) | 18 (8) | 14 (13) | 22 (10) | |||

| uILD | 38 (36) | 125 (57) | 62 (56) | 111 (51) | |||

| Age, years | 63±12 | 69±10 | <0.01 | 68±11 | 67±11 | 0.58 | 0.11 |

| Male | 49 (47) | 110 (50) | 0.66 | 54 (48) | 105 (49) | 0.98 | 0.01 |

| Ethnicity/race | 0.08 | 0.86 | 0.03 | ||||

| White | 59 (56) | 143 (65) | 73 (65) | 137 (63) | |||

| African American | 20 (19) | 41 (19) | 17 (15) | 37 (17) | |||

| Hispanic | 16 (15) | 19 (9) | 12 (11) | 24 (11) | |||

| Asian | 6 (6) | 14 (6) | 8 (7) | 16 (8) | |||

| Other¶ | 4 (4) | 3 (2) | 3 (3) | 3 (1) | |||

| Ever-smoker | 46 (44) | 134 (61) | 0.01 | 73 (65) | 125 (57) | 0.51 | 0.11 |

| Family history of ILD | 13 (12) | 15 (7) | 0.14 | 11 (10) | 20 (9) | 0.84 | 0.04 |

| Lung function | |||||||

| FVC % pred | 65±16 | 71±21 | <0.01 | 72±16 | 70±20 | 0.50 | 0.11 |

| DLCO % pred | 50±19 | 51±21 | 0.62 | 50±17 | 50±21 | 0.85 | 0.03 |

| Radiographic UIP | |||||||

| UIP+ | 8 (8) | 38 (17) | 0.03 | 10 (9) | 30 (14) | 0.41 | 0.12 |

| Honeycombing | 22 (21) | 56 (25) | 0.45 | 21 (19) | 45 (21) | 0.77 | 0.05 |

| IS therapy | |||||||

| Mycophenolate | 91 (87) | 99 (89) | |||||

| Azathioprine | 14 (13) | 13 (11) | |||||

| IS exposure, years | 1.5 (0.5–2.0) | 1.7 (0.8–2.0) | |||||

| Prednisone | 87 (83) | 70 (32) | <0.01 | 50 (44) | 103 (48) | 0.72 | 0.07 |

| LTL | |||||||

| LTL <10th percentile | 21 (20) | 63 (29) | 0.13 | 26 (24) | 62 (29) | 0.61 | 0.12 |

| Age-adjusted LTL | 0.2 (−0.3–0.6) | 0.1 (−0.4–0.5) | 0.12 | 0.1 (−0.3–0.4) | 0.1 (−0.4–0.5) | 0.75 | 0.03 |

| Follow-up, years | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) | 2.0 (1.1–2.0) | 0.03 | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) | 2.0 (1.4–2.0) | 0.34 | 0.23 |

| Outcome | |||||||

| Death within 2 years | 17 (16) | 42 (19) | 0.63 | 21 (19) | 39 (18) | 0.95 | 0.01 |

| Transplant within 2 years | 1 (1) | 3 (1) | 1.0 | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.40 | 0.07 |

Data are presented as n (%), mean±sd or median (interquartile range). SMD: standardised mean difference; UTSW: University of Texas Southwestern; UCSF: University of California San Francisco; Chicago: University of Chicago; UCD: University of California Davis; CUMC: Columbia University Medical Center; ILD: interstitial lung disease; fHP: fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis; CTD: connective tissue disease; uILD: unclassifiable ILD; FVC: forced vital capacity: DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia. #: CTD-ILD diagnoses: scleroderma n=19, rheumatoid arthritis n=5, inflammatory myositis n=6, mixed CTD n=1, Sjögren's syndrome n=2, systemic lupus erythematosus n=3; ¶: other ethnicity/race: Middle Eastern n=2, Native American n=2, Pacific Islander n=3; +: radiographic UIP incudes definite UIP.

In the discovery cohort, 45% of patients were exposed to either mycophenolate or azathioprine within 2 years of blood collection (table 1), while only 32% were exposed in the replication cohort (p<0.001) (table 2). Exposure rates were similar between the discovery and replication cohorts for CTD-ILD (49% versus 50%; p=1.0) and fHP (48% versus 39%; p=0.15), but not uILD (40% versus 23%; p<0.001). Over 80% of patients from both cohorts were initiated on immunosuppressants within 1 year of blood collection (supplementary figure E3); median (interquartile range (IQR)) time to immunosuppressant initiation was 0.1 (0.0–0.5) years and 0.2 (0.0–0.7) years and median (IQR) exposure time was 1.7 (0.7–2.0) years and 1.5 (0.5–2.0) years in the discovery and replication cohorts, respectively. Baseline differences between immunosuppressant-exposed and unexposed patients, including age, severity of lung function impairment and radiographic features, were balanced (SMD <0.15) with propensity score weighting to account for indication bias; however, centre remained imbalanced in the replication cohort (supplementary figure E4).

Leukocyte telomere length

Continuous age-adjusted LTL (median (IQR)) was shorter in the discovery cohort (−0.09 (−0.26–0.09)) than the replication cohort (0.09 (−0.34–0.55); p<0.001) (supplementary figure E5). When dichotomising LTL, more patients in the replication cohort had LTL <10th percentile (26% versus 20%; p=0.04). The prevalence of LTL <10th percentile was highest in uILD (33%) followed by fHP (28%) and CTD-ILD (12%) (supplementary figure E6). In contrast, >80% of CTD-ILD patients had LTL >50th percentile compared with 41% of fHP and 45% of uILD patients. The presence of radiographic UIP or honeycombing was more prevalent in patients with LTL <10th percentile (supplementary table E1). Of the patients with LTL <10th percentile, 47% and 25% were exposed to immunosuppression in the discovery and replication cohorts, respectively. The correlation of 40 individual LTL measurements performed at both UTSW/CUMC and UCSF was found to be in high agreement across sites (r=0.86, p<0.001) (supplementary figure E7).

Transplant-free survival

The 2-year transplant-free survival was similar for the discovery and replication cohorts (p=0.19) and across centres (p=0.95) (supplementary figure E8). Patients with CTD-ILD had better survival than fHP (p<0.001) or uILD (p<0.001). Radiographic honeycombing, but not radiographic UIP, was associated with reduced 2-year transplant-free survival in adjusted analyses (supplementary table E2). Compared with unexposed patients, neither mycophenolate (hazard ratio (HR) 1.47, 95% CI 0.88–2.46; p=0.14) nor azathioprine (HR 1.67, 95% CI 0.83–3.36; p=0.15) exposure was associated with differential 2-year transplant-free survival. There was also no survival difference between mycophenolate and azathioprine exposure (p=0.22).

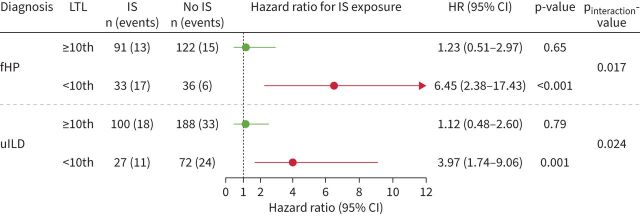

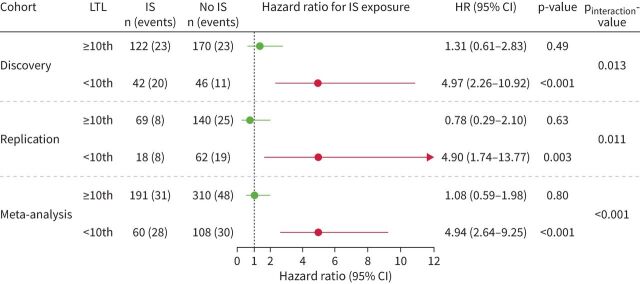

Immunosuppressant exposure was associated with worse 2-year transplant-free survival for both fHP and uILD patients with LTL <10th percentile, but not those with LTL ≥10th percentile (figure 2). In CTD-ILD patients, the low 2-year event rate (6%) and prevalence of LTL <10th percentile (12%) precluded meaningful subgroup survival analyses. In the combined analysis of fHP and uILD patients with age-adjusted LTL <10th percentile, immunosuppressant exposure was associated with worse transplant-free survival in both discovery (HR 4.97, 95% CI 2.26–10.92; p<0.001) and replication cohorts (HR 4.90, 95% CI 1.74–13.77; p=0.003; meta-analysis HR 4.94, 95% CI 2.64–9.25; p<0.001) (figure 3). Immunosuppression was not associated with survival in fHP and uILD patients with LTL ≥10th percentile (pooled meta-analysis HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.59–1.98). There was a significant interaction between immunosuppressant exposure and LTL 10th percentile (discovery pinteraction=0.013; replication pinteraction=0.011; meta-analysis pinteraction<0.001) for patients with fHP and uILD.

FIGURE 2.

Association between immunosuppressant (IS) exposure (mycophenolate or azathioprine) compared with no exposure and 2-year transplant-free survival in fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (fHP) and unclassifiable interstitial lung disease (uILD) patients stratified by age-adjusted leukocyte telomere length (LTL) <10th and ≥10th percentile of normal. Weighted Cox proportional hazards regression model with robust variance estimation and adjustment for radiographic honeycombing and centre.

FIGURE 3.

Association between immunosuppressant (IS) exposure (mycophenolate or azathioprine) and 2-year transplant-free survival in combined fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis and unclassifiable interstitial lung disease (uILD) patients stratified by age-adjusted leukocyte telomere length (LTL) <10th and ≥10th percentile of normal. Weighted Cox proportional hazards regression model with robust variance estimation and adjustment for non-idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis ILD diagnosis, radiographic honeycombing and centre.

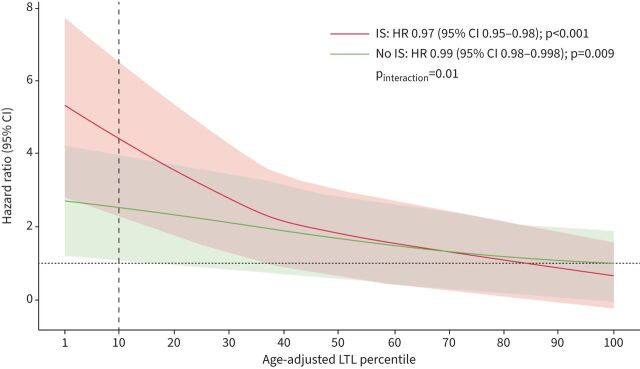

Sensitivity analyses using age-adjusted LTL percentile as a continuous variable confirmed that shorter LTL was associated with worse survival overall regardless of exposure, but this detrimental association was magnified by immunosuppression treatment (pinteraction=0.01) for fHP and uILD patients (figure 4). In a subset of fHP and uILD patients initiated on immunosuppression within 1 year of blood collection and who had >3 months of exposure, immunosuppression was similarly associated with reduced survival in those with LTL <10th percentile (supplementary figure E9). Both mycophenolate and azathioprine individually were associated with reduced transplant-free survival in fHP and uILD patients with LTL <10th percentile; however, the interaction between LTL and azathioprine exposure was inconsistent (supplementary figure E10). Prednisone monotherapy was not associated with differential 2-year transplant-free survival for non-IPF ILD patients with LTL <10th or ≥10th percentile (supplementary table E3).

FIGURE 4.

Association between immunosuppressant (IS) exposure and age-adjusted leukocyte telomere length (LTL) percentile as a continuous variable for fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis and unclassifiable interstitial lung disease (uILD) patients. Weighted Cox proportional hazards regression model with robust variance estimation and adjustment for non-idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis ILD diagnosis, radiographic honeycombing and centre.

Longitudinal FVC trajectory

There were 286 immunosuppressant-exposed patients (201 mycophenolate, 85 azathioprine) and 251 unexposed patients from both cohorts included in this analysis. The median (IQR) FVC measurement timespan was similar between exposed (1.17 (0.55–1.71) years) and unexposed patients (1.27 (0.68–1.65) years; p=0.75). The annualised rate of FVC change over 2 years did not differ by study cohort or ILD subtype (supplementary table E4). Immunosuppressant exposure was not associated with differential FVC change (exposed: −60 (95% CI −91– −30) mL per year versus unexposed: −83 (95% CI −116– −50) mL per year; p=0.32). Patients with LTL <10th percentile experienced faster FVC decline (−125 (95% CI −178– −72) mL per year) than those with LTL ≥10th percentile (−59 (95% CI −84– −35) mL per year; p=0.027). However, neither the composite (table 3) nor the individual immunosuppressant medications (supplementary table E5) were associated with differential FVC trajectory in patients stratified by the age-adjusted LTL 10th percentile threshold.

TABLE 3.

Annualised change in forced vital capacity (FVC) for non-idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis interstitial lung disease (ILD) patients stratified by immunosuppressant (IS) exposure and age-adjusted leukocyte telomere length (LTL) <10th and ≥10th percentile of normal

| IS exposed | IS unexposed | p-value | |||

| n (n FVC) | ΔFVC, mL per year (95% CI) # | n (n FVC) | ΔFVC, mL per year (95% CI) # | ||

| LTL <10th percentile | 55 (209) | −141 (−218– −65) | 56 (177) | −111 (−184– −39) | 0.58 |

| LTL ≥10th percentile | 231 (978) | −46 (−79– −12) | 195 (673) | −76 (−113– −39) | 0.23 |

#: joint model incorporating time-to-event and linear mixed effects submodels, adjusted for ILD diagnosis, radiographic honeycombing and ILD centre. Restricted to patients with at least two FVC measurements while on immunosuppression within 2 years of blood collection for exposed patients and at least two FVC measurements within 2 years of blood collection for unexposed patients.

Discussion

This study evaluated the impact of commonly used immunosuppressants on 2-year transplant-free survival in non-IPF ILD patients stratified by age-adjusted LTL percentiles. We found that immunosuppressant exposure was associated with reduced survival for fHP and uILD patients with age-adjusted LTL <10th percentile. However, the study was underpowered to examine the survival associations between immunosuppressant exposure and age-adjusted LTL for CTD-ILD patients. In addition, LTL <10th percentile was associated with faster FVC decline independent of immunosuppressant exposure. These data suggest that commonly used immunosuppressants may be associated with higher mortality risk, but not progressive lung function decline, in a subset of fHP and uILD patients.

Over the last decade, ILD treatment strategy has shifted from near-universal use of immunosuppressants to thoughtful medication selection guided by ILD subtype. Based on high-quality studies, an IPF diagnosis mandates avoidance of immunosuppressants in favour of antifibrotics [1, 2, 30]. In contrast, treatment selection and timing in non-IPF ILDs is highly variable. Immunosuppressants have been a common therapeutic option for non-IPF ILD patients requiring therapy based on limited clinical trials and observational studies [31–35]. However, monitoring for progression without therapy may be appropriate for some non-IPF ILD patients [36]. In this study, 60% of patients were not initiated on therapy during the 2-year follow-up. Therefore, there is an urgent need for biomarkers that can identify high-risk patients and inform their treatment strategy. Given the current data, we propose that LTL may serve both functions.

We confirm prior studies demonstrating that non-IPF ILD patients with short LTL are at high risk of progression, experience worse mortality and may benefit from earlier treatment [13–20]. While LTL testing for IPF patients may similarly aid in prognostication, it is unlikely to inform treatment selection since antifibrotics appear safe and effective in patients with telomere dysfunction [10, 37]. However, we find that LTL may allow personalised management for some non-IPF ILDs. Our study found that immunosuppressant exposure was associated with higher mortality risk in fHP and uILD patients with age-adjusted LTL <10th percentile. While prospective studies are needed, our findings suggest that LTL testing may inform treatment selection whereby immunosuppressants should be considered with caution in fHP and uILD patients with LTL <10th percentile.

The current study differs from our prior report [17] examining the differential impact of mycophenolate for fHP patients stratified by LTL quartiles in multiple ways. First, we applied age-adjusted LTL percentiles that are generalisable outside of our study cohort. Second, we dichotomised by age-adjusted LTL <10th percentile as a biologically relevant threshold; prior studies demonstrated this threshold to be sensitive to detecting carriers with pathogenic telomere gene mutations [5]. However, immunosuppressant exposure was associated with higher mortality risk across the continuum of LTL percentiles, driven by the shortest LTLs. Third, we mitigated immortal time bias [22] by enrolling at time of LTL measurement and modelled immunosuppressant exposure as a time-dependent covariate [38]. Using this approach, we found that mycophenolate was not associated with favourable survival in any subpopulation and was associated with worse outcomes in those with LTL <10th percentile. Lastly, the current study expanded the size and scope of the analysis to include additional ILD subtypes and immunosuppressants in additional cohorts. These efforts uncovered a significant interaction between short LTL and immunosuppressant exposure for fHP and uILD patients, whereby immunosuppressant exposure was associated with higher mortality risk for those with age-adjusted LTL <10th percentile.

We also found important differences across the non-IPF ILD subtypes included in this study. While the phenotypic heterogeneity within the CTDs may have limited this subgroup analysis, there were also fewer events and lower prevalence of short telomeres that limited the assessment of an immunosuppression and LTL interaction. In contrast to CTD-ILD, the fHP and uILD cohorts had a higher prevalence of LTL <10th percentile, which approached the level seen in IPF cohorts [20]. In addition, the current study found that radiographic UIP and honeycombing were present in a higher proportion of non-IPF ILD patients with LTL <10th percentile, similar to a prior study in fHP patients [15]. However, the effect of these “UIP-like” features on survival was smaller than the effect of LTL and neither UIP nor honeycombing modified the impact of immunosuppression on survival. Therefore, the current data suggest that short LTL may predispose to a “UIP-like” phenotype, but the short LTL confers a greater impact on survival that may be further magnified by immunosuppressive therapies.

Immunosuppressant exposure was not associated with differential FVC decline in non-IPF ILD patients with LTL <10th percentile, suggesting a harmful effect unrelated to progressive lung fibrosis. Immunosuppressants are associated with non-pulmonary complications in lung transplant recipients with short LTL or telomere gene mutations [39–42]. These medications may unmask extrapulmonary short telomere syndrome manifestations, including bone marrow suppression and impaired adaptive immunity [43, 44], tipping the balance toward harmful inhibition of protective immunity without causing progressive lung function decline. Prospective studies with systematic evaluation of pulmonary and non-pulmonary effects of immunosuppressants are needed.

The current study has limitations. First, this retrospective study demonstrates associations but not causal links. Future clinical trials are needed to validate these findings and inform clinical practice. Second, we accounted for indication bias by using measured variables that influence immunosuppressant exposure to generate weighted propensity scores. Using this approach, we were able to balance the distribution of important covariates such as age, sex, severity of disease and radiographic patterns across exposure groups, thus limiting their influence on effect estimates. However, given the non-randomised nature of this study, we cannot exclude the possibility of unmeasured effects impacting our results. Third, subsetting the relatively large total cohort reduced the effective sample size and may have led to imprecision. However, similar direction and magnitude of effects were seen across secondary analysis, increasing confidence that the associations may approach reality. Fourth, we used banked genomic DNA to measure LTL by qPCR at two sites, which may have introduced variability in the LTL measurement, although the correlation between site measurements was high. Given the potential for LTL variability across sites, we chose to perform meta-analysis of the two cohorts, instead of combining. Next, only fibrotic ILDs were included so it remains unknown if a similar interaction exists in non-fibrotic ILDs. Lastly, we were unable to systematically assess immunosuppressant-related adverse effects due to the non-standardised follow-up or the impact of other ILD treatments due to lower usage in the cohorts.

Conclusions

By identifying a harmful pharmacogenomic interaction between LTL <10th percentile of normal and mycophenolate or azathioprine exposure, we demonstrate that LTL may be a clinically viable genomic marker to aid treatment decisions for fHP and uILD patients. The findings should form the basis for prospective validation studies to determine if LTL-informed personalised treatment selection improves outcomes.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-00441-2023.Supplement (968KB, pdf)

Shareable PDF

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all participating patients and research staff that assisted with patient recruitment, data collection and technical analyses (Leslie Vickers at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY, USA; Jane Berkeley at University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA).

Footnotes

This article has an editorial commentary: https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01852-2023

Author contributions: Study design: D. Zhang, A. Adegunsoye, C.K. Garcia and C.A. Newton. Patient recruitment or data collection: D. Zhang, A. Adegunsoye, J.M. Oldham, N. Garcia, M. Poonawalla, R. Strykowski, S-F. Ma, I. Noth, M.E. Strek, P.J. Wolters, C.K. Garcia and C.A. Newton. Data analysis: J. Kozlitina and C.A. Newton. Interpretation of the results: D. Zhang, A. Adegunsoye, J.M. Oldham, J. Kozlitina, P.J. Wolters, C.K. Garcia and C.A. Newton. Manuscript preparation: D. Zhang, A. Adegunsoye and C.A. Newton. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest: D. Zhang reports consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, and grant support from the Stony Wold-Herbert Fund and Parker B. Francis Foundation. A. Adegunsoye reports consulting fees from Genentech, Inogen, Medscape, PatientMpower and Boehringer Ingelheim, lecture honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, and grant support from the NHLBI. J.M. Oldham reports consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Lupin Pharmaceuticals, AmMax Bio, Roche and Veracyte, advisory board participation with Endeavor Biomedicines, and grant support from the NHLBI; J.M. Oldham also has a patent “TOLLIP TT genotype for NAC use in IPF” issued, and is an associate editor of CHEST, as well as a member of the programme committee for the American Thoracic Society. I. Noth reports consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Sanofi, data safety monitoring board participation with Yale, and grant support from Veracyte and the NIH. M.E. Strek reports honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Fibrogen and the American College of Chest Physicians, advisory board participation with Fibrogen, and grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim and the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation; M.E. Strek also reports being a member of the scientific review committee of the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation. P.J. Wolters reports grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Sanofi, Pliant and the NIH, and consulting fees from Blade Therapeutics. C.K. Garcia reports grant support from the NIH, DOD and Boehringer Ingelheim, lecture honoraria from Three Lakes Foundation, Stanford, UPenn, UCSF and Cedar-Sinai. C.A. Newton reports consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and grant support from the NHLBI; C.A. Newton is also a member of the scientific review committee for the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation, member of the editorial board for CHEST and member of the planning committee for the American Thoracic Society. J. Kozlitina, N. Garcia, M. Poonawalla, R. Strykowski, A.L. Linderholm, B. Ley and S-F. Ma have nothing to disclose.

Support statement: Support from the National Institutes of Health includes K23HL146942 (A. Adegunsoye), K23HL138190 and R56HL158935 (J.M. Oldham), UG3HL145266 (I. Noth), R01HL093096 (C.K. Garcia), K23HL148498 and UL1TR001105 (C.A. Newton); Stony Wold-Herbert Fund and Parker B. Francis Foundation (D. Zhang), Nina Ireland Program for Lung Health (P.J. Wolters). Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2083–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2071–2082. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsakiri KD, Cronkhite JT, Kuan PJ, et al. Adult-onset pulmonary fibrosis caused by mutations in telomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 7552–7557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701009104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armanios MY, Chen JJ, Cogan JD, et al. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 1317–1326. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuart BD, Choi J, Zaidi S, et al. Exome sequencing links mutations in PARN and RTEL1 with familial pulmonary fibrosis and telomere shortening. Nat Genet 2015; 47: 512–517. doi: 10.1038/ng.3278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannengiesser C, Borie R, Menard C, et al. Heterozygous RTEL1 mutations are associated with familial pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2015; 46: 474–485. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00040115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cogan JD, Kropski JA, Zhao M, et al. Rare variants in RTEL1 are associated with familial interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 191: 646–655. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201408-1510OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrovski S, Todd JL, Durheim MT, et al. An exome sequencing study to assess the role of rare genetic variation in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 196: 82–93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201610-2088OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ley B, Torgerson DG, Oldham JM, et al. Rare protein-altering telomere-related gene variants in patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 200: 1154–1163. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201902-0360OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dressen A, Abbas AR, Cabanski C, et al. Analysis of protein-altering variants in telomerase genes and their association with MUC5B common variant status in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a candidate gene sequencing study. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6: 603–614. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30135-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alder JK, Chen JJ, Lancaster L, et al. Short telomeres are a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 13051–13056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804280105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duckworth A, Gibbons MA, Allen RJ, et al. Telomere length and risk of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a Mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: 285–294. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30364-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stuart BD, Lee JS, Kozlitina J, et al. Effect of telomere length on survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an observational cohort study with independent validation. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2: 557–565. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70124-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dai J, Cai H, Li H, et al. Association between telomere length and survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2015; 20: 947–952. doi: 10.1111/resp.12566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ley B, Newton CA, Arnould I, et al. The MUC5B promoter polymorphism and telomere length in patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: an observational cohort-control study. Lancet Respir Med 2017; 5: 639–647. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30216-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Zhuang Y, Peng H, et al. The relationship between MUC5B promoter, TERT polymorphisms and telomere lengths with radiographic extent and survival in a Chinese IPF cohort. Sci Rep 2019; 9: 15307. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51902-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adegunsoye A, Morisset J, Newton CA, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and mycophenolate therapy in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Eur Respir J 2021; 57: 2002872. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02872-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ley B, Liu S, Elicker BM, et al. Telomere length in patients with unclassifiable interstitial lung disease: a cohort study. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2000268. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00268-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Chung MP, Ley B, et al. Peripheral blood leucocyte telomere length is associated with progression of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Thorax 2021; 76: 1186–1192. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newton CA, Oldham JM, Ley B, et al. Telomere length and genetic variant associations with interstitial lung disease progression and survival. Eur Respir J 2019; 53: 1801641. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01641-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newton CA, Zhang D, Oldham JM, et al. Telomere length and use of immunosuppressive medications in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 200: 336–347. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201809-1646OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suissa S. Immortal time bias in pharmaco-epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 167: 492–499. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Leon AD, Cronkhite JT, Katzenstein AL, et al. Telomere lengths, pulmonary fibrosis and telomerase (TERT) mutations. PLoS One 2010; 5: e10680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faust HE, Golden JA, Rajalingam R, et al. Short lung transplant donor telomere length is associated with decreased CLAD-free survival. Thorax 2017; 72: 1052–1054. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med 2015; 34: 3661–3679. doi: 10.1002/sim.6607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adegunsoye A, Oldham JM, Bellam SK, et al. CT honeycombing identifies a progressive fibrotic phenotype with increased mortality across diverse interstitial lung diseases. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019; 16: 580–588. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201807-443OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryerson CJ, Urbania TH, Richeldi L, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of unclassifiable interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J 2013; 42: 750–757. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00131912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crowther MJ, Abrams KR, Lambert PC. Flexible parametric joint modelling of longitudinal and survival data. Stat Med 2012; 31: 4456–4471. doi: 10.1002/sim.5644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hogan JW, Laird NM. Model-based approaches to analysing incomplete longitudinal and failure time data. Stat Med 1997; 16: 259–272. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network . Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1968–1977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, et al. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 2655–2666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Clements PJ, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): a randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4: 708–719. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30152-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morisset J, Johannson KA, Vittinghoff E, et al. Use of mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine for the management of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Chest 2017; 151: 619–625. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adegunsoye A, Oldham JM, Fernandez Perez ER, et al. Outcomes of immunosuppressive therapy in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. ERJ Open Res 2017; 3: 00016-2017. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00016-2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oldham JM, Lee C, Valenzi E, et al. Azathioprine response in patients with fibrotic connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. Respir Med 2016; 121: 117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022; 205: e18–e47. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Justet A, Klay D, Porcher R, et al. Safety and efficacy of pirfenidone and nintedanib in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and carrying a telomere-related gene mutation. Eur Respir J 2021; 57: 2003198. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03198-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suissa S, Suissa K. Antifibrotics and reduced mortality in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: immortal time bias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023; 207: 105–109. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202207-1301LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borie R, Kannengiesser C, Hirschi S, et al. Severe hematologic complications after lung transplantation in patients with telomerase complex mutations. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015; 34: 538–546. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Courtwright AM, Lamattina AM, Takahashi M, et al. Shorter telomere length following lung transplantation is associated with clinically significant leukopenia and decreased chronic lung allograft dysfunction-free survival. ERJ Open Res 2020; 6: 00003-2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00003-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newton CA, Kozlitina J, Lines JR, et al. Telomere length in patients with pulmonary fibrosis associated with chronic lung allograft dysfunction and post-lung transplantation survival. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017; 36: 845–853. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tokman S, Singer JP, Devine MS, et al. Clinical outcomes of lung transplant recipients with telomerase mutations. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015; 34: 1318–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Popescu I, Mannem H, Winters SA, et al. Impaired cytomegalovirus immunity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis lung transplant recipients with short telomeres. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 199: 362–376. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201805-0825OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang P, Leung J, Lam A, et al. Lung transplant recipients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have impaired alloreactive immune responses. J Heart Lung Transplant 2022; 41: 641–653. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2021.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-00441-2023.Supplement (968KB, pdf)

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-00441-2023.Shareable (436.1KB, pdf)