Abstract

The plant–parasitic Root Knot Nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.,) play a pivotal role to devastate vegetable crops across the globe. Considering the significance of plant–microbe interaction in the suppression of Root Knot Nematode, we investigated the diversity of microbiome associated with bioagents-treated and nematode-infected rhizosphere soil samples through metagenomics approach. The wide variety of organisms spread across different ecosystems showed the highest average abundance within each taxonomic level. In the rhizosphere, Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria were the dominant bacterial taxa, while Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Mucoromycota were prevalent among the fungal taxa. Regardless of the specific treatments, bacterial genera like Bacillus, Sphingomonas, and Pseudomonas were consistently found in high abundance. Shannon diversity index vividly ensured that, bacterial communities were maximum in B. velezensis VB7-treated soil (1.4–2.4), followed by Root Knot Nematode-associated soils (1.3–2.2), whereas richness was higher with Trichoderma konigiopsis TK drenched soils (1.3–2.0). The predominant occurrence of fungal genera such as Aspergillus Epicoccum, Choanephora, Alternaria and Thanatephorus habituate rhizosphere soils. Shannon index expressed the abundant richness of fungal species in treated samples (1.04–0.90). Further, refraction and species diversity curve also depicted a significant increase with maximum diversity of fungal species in B. velezensis VB7-treated soil than T. koningiopsis and nematode-infested soil. In field trial, bioagents-treated tomato plant (60% reduction of Meloidogyne incognita infection) had reduced gall index along with enhanced plant growth and increased fruit yield in comparison with the untreated plant. Hence, B. velezensis VB7 and T. koingiopsis can be well explored as an antinemic bioagents against RKN.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-023-03851-1.

Keywords: Meloidogyne incognita, Bacillus velezensis VB7, Trichoderma koningiopsis TK, Rhizosphere soil, Tomato

Introduction

Root Knot Nematode (Meloidogyne spp.,) being a devastating plant parasitic nematode of tomato, causes a significant yield loss in crop production, worldwide (Berliner et al. 2023; Liu et al. 2023; Lamelas et al. 2020). The annual loss due to RKN in tomato was estimated as 110 billion dollars (El-Nuby et al. 2021; Ibrahim et al. 2021) with 30% to 50% crop loss globally (Phani et al. 2021; Zhao et al. 2023a, b, c). As a sedentary endoparasite, it completes its life cycle in plant tissue by developing giant cells in roots which lead to the development of root galls and thus interfere with the plant metabolic process (Huang et al. 2022; Elhady et al. 2017). The cuticle of RKN, composed of glycosylated proteins serve as a physical barrier against microbes, which has a significant role in evading host defense and microbial attack. But in the recent past, managing plant parasitic nematodes (PPN) in an eco-friendly manner with beneficial antagonistic microbes has paved the way to suppress PPN successfully, and thus contributes to ensure a pollution-free ecosystem (Abd-Elgawad 2020).

In this context, the fungal and bacterial antagonists, bestowed with diverse mechanisms aid to suppress nematode infection besides promoting plant growth (Abd-Elgawad et al. 2018; Topalović et al. 2020; Viljoen et al. 2019; Xiang et al. 2018). Antagonism by bacteria on PPN affects mortality, motility, egg hatching and reduce the invasion of plant roots through several mechanisms (Topalović et al. 2019). Hitherto, several evidences have explained the nematicidal effect of Bacillus spp (Abd-Elgawad et al. 2018; Cetintas et al. 2018; Xiao et al. 2018; Zhou et al. 2019) and fungal bioagents (Fan et al. 2020; Khan et al. 2020) in vitro and in vivo. However, the niche of the rhizosphere soil is bestowed with cultivable and non-cultivable microbial communities, the interaction of the complex microbial communities with plants also influences the diversity of the microbiome and taxonomic profile responsible to defend against a wide range of phytopathogens and environmental stress (Glick and Gamalero 2021). As a consequence, the nematicidal activity and the efficacy of bioagents could be complemented by the interaction of microbial communities in the rhizosphere ecosystem (Zhao et al. 2023a, b, c). There are several reports, that supported the microbe–microbe and plant–microbe interactions in the rhizosphere through the interchange of numerous signal molecules to possess a substantial effect on microbial functions (Akanmu et al. 2021).

Thus, the microbial diversity strengthens the system’s resistance leading to the disruptions and reduction in the activity of destructive biota like soil-borne pathogens (Bertola et al. 2021), including PPN. It is noteworthy to mention that, the present investigations on the diversity of microbial communities associated with rhizosphere have utilized culture-independent strategies that can be unveiled through metagenomic approaches including pyrosequencing and 16S rRNA as well as 18SrRNA sequencing would dissect the diversity of uncultivable microbes and their genetic information along with a deeper insight into functional traits (Fadiji et al. 2021). The coexistence of nematodes along with bioagents has a potential antagonistic effect to suppress the infection of nematodes via interaction with other diverse microbiomes. Several research findings explained the diversity of microbiome have altered the bacterial (Lamelas et al. 2020; Zheng et al. 2019) and fungal (Liu et al. 2018; Su et al. 2020; Zhou et al. 2021) communities in healthy and diseased tomato plants. Considering the significance of microbial communities, the knowledge on diverse nature of microbiome in RKN-infected and healthy tomato roots may aid to delineate the information about the variations in the diversity of microbial communities related to parasitism and antagonistic activity (Tian et al. 2015).

The application of bio-agents for the management of RKN may alter the rhizosphere microbiome diversity leading to a change in root biology, with potential effects on the establishment of specialized rhizosphere organisms. However, there is no evidence regarding the diversity analysis of microbial communities in tomato plants augmented with bio-agents under field conditions responsible for the management of RKN. Therefore, we investigated the diversity of microbiome in tomato rhizosphere soil augmented with B. velezensis VB7 and T. koningiopsis TK against the infection of RKN in tomato plants under field conditions through metagenomic analysis of rhizosphere soil samples.

Materials and methods

Collection of samples

Rhizosphere soil samples were collected from three different treatments by random sampling technique at 30 days after drenching the soil with 1% T. koningiopsis TK (Suneeta et al. 2017) formulation (3 × 108 cfu/g) and with liquid formulation of B. velezensis VB7 (MW301630) (5 × 108 cfu/mL) as per the protocol of (Vinodkumar et al. 2018) in RKN infected tomato field trial laid at Thondamuthur in Coimbatore province of Tamil Nadu, India (GPS coordinates: 10.5484°N 76.2857°E). Three biological replicates were maintained for each sample. Collected samples were stored in sterile polypropylene bags, immediately placed in an ice box, transported to the laboratory and stored at − 80 °C before processing.

PCR amplification of 16S rRNA and purification

Metagenomic DNA was separately extracted from the collected rhizosphere soil for B. velezensis VB7 (MW301630), T. koningiopsis TK (KX 555650)-treated and untreated control using Power Soil DNA Isolation Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany). Quantitative and qualitative analysis of DNA was performed by Nanodrop followed by agarose gel electrophoresis. A total of 50 ng DNA from each sample were subjected to PCR amplification using 16S rRNA gene amplification using V1–V9 region-specific primers of 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG3′) and 1492R (5′TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT3′) and fungal ribosomal operon (18S rRNA) region-specific primers KYO – FP (5′- ATAGAGGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAA-3′) and LE31-RP (5′- ATGGTCCGTGTTTCAAGAC-3′). The amplicons obtained from the samples were confirmed by Agarose (1%) with EtBr gel electrophoresis. The PCR products were purified using 1.6X Ampure XP beads (Beckmann Coulter, USA).

Library preparation and sequencing of DNA product

A total ~50 ng from each amplicon DNA was end-repaired (NEBnext ultra II end repair kit,), and cleaned with 1x AmPure beads. Barcoding adapter ligation (BCA) was performed with NEB blunt/TA ligase and cleaned with 1x AmPure beads. Qubit quantified adapter-ligated DNA samples were barcoded using PCR reaction and pooled at equimolar concentration. The end-repair was performed using NEB next ultra II end repair kit (New England Biolabs, MA, USA) and cleaned. Adapter ligation (AMX) was performed for 15 minutes using NEB blunt/TA ligase (New England Biolabs, MA, USA). Library mix was cleaned up using Ampure beads and finally eluted in 15 μl of elution buffer. Sequencing was performed for both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms through the Oxford Nanopore sequencing method using MinION flow cell R9.4 (FLO-MIN106). Nanopore raw reads (‘fast5’ format) were base-called (‘fastq5’ format) and de-multiplexed using Guppy1 v2.3.4.

Processing of sequencing data and taxonomic profiling

Sequencing data were processed with Guppy v2.3.4 tool kit used for base calling the sequencing data to generate pass read. The adapter and barcode sequences were trimmed using the Porechop tool. The reads were filtered by size using SeqKit software ver. 0.10.0 and the average Phred quality score was assessed using SILVA database. A comprehensive taxonomic analysis of microbial communities was performed on the processed reads from each set. To conduct the diversity analysis, obtained rRNA reads were imported into Qiime2 in the Single End Fastq Manifest Phred33 input format. The readings were de-duplicated and then grouped into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) based on their 97% similarity (Schloss et al. 2009). BLAST with QIIME (categorize-consensus-search) was used to classify representative sequences using percent identity 0.97 against the SILVA full-length 16S and ITS database. The long-read amplicons data were sequenced by using Nanopore MinION and validated against SILVA databases to determine their classification. The relative microbial abundances were determined to categorize the microbial community of each sample according to their taxonomic profile (Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species-level) and indicated in a stacked bar chart. The top 20 bacterial and fungal communities were used as illustrated in the figures.

Diversity index analysis

The alpha diversity analysis was carried out using the Shannon, Evenness vector index to determine the richness of the microbial community. Core microbiome diversity was performed at a sequencing depth of 521bp to determine the richness and diversity of species (Shannon 1948). The statistical differences between the microbiome groups were determined using the Mann–Whitney or ANOVA nonparametric tests in Prism. The dissimilarity between the two samples was analysed using the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity statistic (Bray and Curtis 1957), measured phylogenetic distances and relative abundance (Sharma et al. 2008). Principal coordinates (PCoA) plots were generated to determine the community structure using QIIME1 version 1.9.1 (Caporaso et al. 2010)

The efficiency of bioagents against M. incognita in field condition

To assess the efficacy of bacterial and fungal bioagents, field experiments were conducted in a tomato field laid at Thondamuthur in Coimbatore province of Tamil Nadu (GPS coordinates: 10.5484°N 76.2857°E). Tomato hybrid Sivam was used in the study. Bioagents, B. velezensis VB7 (5 × 108 cfu/mL) and T. koningiopsis (TK) (3 × 108 cfu/mL) based formulation at 1% concentration were applied through soil drenching. Three different treatments include; T1 - B. velezensis (@ 1 % conc.) + RKN, T2 – T. koningiopsis TK (@ 1 % conc.) + RKNand T3 - RKN (Untreated control). The bioagents were applied periodically on 15, 30, 45 and 60 days after transplanting (DAT). The observation of plant height, yield and root gall index was recorded periodically. In addition, the average weight of fruits per plant was also recorded. All the treatments were replicated seven times, for each treatment over an area of 40.5 m2 with a spacing of 90×60 cm in a randomized block design (RBD). The gall index was scored with 1 to 5-point scale: 1 = no galls; 2 = 1–25% galled roots; 3 = 26–50% galled roots; 4 = 51–75% galled roots; 5 = > 75% galled roots (Dube and Smart, 1987). The disease index was calculated according to the formula: Disease index = [∑ (Number of tomato plants in the gall index × Gall index) / (Number of total plants × Highest gall index)] × 100. The efficacy of VB7 and TK against M. incognita in the field was assessed with the formula: Managing effect (%) = [(Disease index of control − Disease index of treatment)/Disease index of control] × 100.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed the relative abundance of the microbial communities at phylum to genus levels using a stacked bar chart. All statistical analyses were performed using the R (v4.2.1) software. QIIME scripts were used to plot and calculate the alpha diversity index including the Shannon index. Permutation multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was performed using the vegan package to compare and determine the significant differences in beta diversity among the samples. The diversity in fungal community structure was studied using the Bray–Curti’s differential method. The unconstrained principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was used to visualize the fungal community structure.

Results

Diversity of bacterial community

Totally 5,75,212 raw reads with an average of 1,91,737 raw reads were generated using 16S rRNA gene amplification. The raw reads were trimmed and quality filtered. Finally, after quality checking, 4,94,763 clean reads with an average of 1,64,921 reads remained. The quality-filtered reads were further size filtered to obtain the classified OTUs to retain the target V1–V9 region which comprised 1200–1950 bp sequences. Totally, 9604 size filtered reads ranging from 2722 to 3517 reads were identified by processing of QC filtered reads. A total of 2014 OTUs were identified as classified read. Among these, 561 (24.69 %) for B. velezensis VB7 rhizosphere soil, 737 (20.96 %) for T. koningiopsis TK rhizosphere soil and 716 (21.28 %) for RKN-infested soil were used for further analysis. A metagenomic analysis revealed the existence of 20 phylum, 42 classes, 88 orders, 122 families, 187 genera and 219 species of bacterial biome from all 3 rhizosphere soil samples through Nanopore MinION sequencing using the SILVA database. The major bacterial phylum in all rhizosphere samples were identified as Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Chloroflexi, Bacteroidota, Cyanobacteria, Planctomycetota, Verrucomicrobiota, Acidobacteriota, Gemmatimonadota, Nitrospirota, Myxococcota, Patescibacteria, Campilobacterota and Spirochaetota. Among them, the dominant bacterial Phylum were identified as Proteobacteria (38.41%), Firmicutes (20.63%), Actinobacteriota (20%), Chloroflexi (5.87%) and Cyanobacteria (3.80%) (Fig. S1). However, the percent relative abundance of bacterial phylum varied in response to different treatments. Irrespective of the three treatments, Proteobacteria had the highest relative abundance value of 39.71% in T. koningiopsis TK-treated soil, followed by 39.05% in B. velezensis VB7-treated soil and 36.26% in RKN-infested soil. Proteobacteria was followed by Firmicutes and ranked second in relative abundance (RA). Comparison of RA between the treatments indicated that, the abundance of Firmicutes was the maximum in RKN-infested soil (22.27%), and was succeeded by B. velezensis VB7 (20.17%) and T. koningiopsis TK (19.61%) applied soil. The third predominant phylum was Actinobacteriota. The abundance of Actinobacteriota was maximum in the rhizosphere soil drenched with T. koningiopsis TK (22.0%). Subsequently, it was followed by B. velezensis VB7 with 20.17% relative abundance. However, abundance of Actinobacteriota was lowest (17.61%) in RKN-infested soil. The other phylums including Bacteroidota and Spirochaetota were not found to differ significantly between the treatments (Fig. 1a).

Fig.1.

Relative abundances of bacterial taxa with respective to various treatments. a Relative abundance of bacterial phyla, b Relative abundances of bacterial classes, c Relative abundances of bacterial orders, d Relative abundances of bacterial families, e Relative abundances of bacterial genera, and f Relative abundances of bacterial species, VB7 – B. velezensis VB7, TK – T. koningiopsis and RKN – Root Knot Nematode (Control)

Comparison of metagenomic data, irrespective of various treatments indicated the existence of various classes pertaining to α proteobacteria, γ proteobacteria, Bacilli, Actinobacteria, Thermoleophilia, Vicinamibacteria, Cyanobacteria, Anaerolineae, Acidimicrobiia, Rubrobacteria, Bacteroidia, Rubrobacteria, Saccharimonadia, Polyangia, Gemmatimonadetes, Verrucomicrobiae, Myxococcia and Blastocatellia (Fig. S2). Among the top 20 different classes, α proteobacteria (21.86%), γ proteobacteria (19.24%), Bacilli (17.98%) and Actinobacteria (13.05%) were predominant in rhizosphere soil. The relative abundance of α Proteobacteria (8%) and Actinobacteria (4%) was also maximum in tomato rhizosphere soils drenched with B. velezensis VB7 (Fig. 1b). Abundance of γ proteobacteria was maximum in the soil treated with T. koningiopsis TK (27.81%). However, the relative abundance of Bacilli was maximum (20.93%) in RKN-infected soil rather than the bioagents-treated soils.

The dominant 20 bacterial orders documented from tomato rhizosphere treated with B. velezensis VB7, T. koningiopsis TK and soil infested by RKN were identified as Bacillales, Sphingomonadales, Burkholderiales, Micrococcales, Rhizobiales, Xanthomonadales, Pseudomonadales, Gemmatimonadales, Streptomycetales, Paenibacillales, Solirubrobacterales, Anaerolineales, Gaiellales, Rhodobacterales, Tistrellales, Anaerolineales, Cyanobacteriales, Microtrichales, Cellvibrionales, Vicinamibacterales and Propionibacteriales (Fig. S3). Among them, the predominant bacterial orders that habituated in the tomato rhizosphere pertains to Bacillales (26%), Sphingomonadales (10.20%), Burkholderiales (9.97%), Micrococcales (7.02%), Rhizobiales (6.57%) and Xanthomonadales (5.9%). But, the diversity of relative abundance varied between the treatments. The relative abundance of Bacillales (28.02%) and Sphingomonadales (14.64%) was maximum in rhizosphere soil of B. velezensis VB7 (28.02%), and was followed in the rhizosphere soils of T. koningiopsis TK and RKN-infested soils (Fig. 1c).

The top 20 families of bacterial communities in rhizosphere soil were identified as Bacillaceae, Sphingomonadaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, Comamonadaceae, Micrococcaceae, Xanthomonadaceae, Rhizobiaceae, Streptomycetaceae, Microbacteriaceae, Comamonadaceae, Beijerinckiaceae, Microbacteriaceae, Nocardioidaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, Vicinamibacteraceae, Gaiellaceae, Rhodobacteraceae, Cellvibrionaceae and Paenibacillaceae (Fig. S4). The dominant families irrespective of different rhizosphere soils comprised only Bacillaceae (31.43%), and Sphingomonadaceae (10.24%). The bacterial population of Bacillacae in T. koningiopsis TK-treated soil and RKN-infested soil constituted the higher RA of 30.23% and 31.81%, whereas lower RA of 25.42% was observed in B. velezensis VB7-treated soil. On the contrary, relative abundance of Sphingomonadaceae (18.18%), Rhizobiaceae (11.3%) and Pseudomonadaceae (5.58%) was maximum in B. velezensis VB7-treated soil (Fig. 1d).

The major rhizosphere genera observed in rhizosphere soil samples, irrespective of different treatments were characterized as Bacillus, Sphingomonas, Pseudomonas, Gaiella, Cellvibrio, Rubrobacter, Solirubrobacter, Nocardioides, Paenibacillus, Microbacterium, Pluralibacter, Thermomonas, Lysobacter, Ensifer and Acidovorax. Among the 20, predominant genera, Bacillus (19.06%) was dominant in rhizosphere region, followed by Sphingomonas (5.5%), Pseudomonas (4.1%), Gaiella (2%) and Streptomyces (2.0%) (Fig. S5). Soil associated with RKN had the highest relative abundance of 45.54% of Bacillus, while VB7 and TK applied soil had 35.86% and 28.44%, respectively. The relative abundance of Sphingomonas was 16.30%, 6.40%, and 9.90% in B. velezensis VB7, T. koningiopsis TK and RKN-infested soils, respectively. On the contrary, RA of the genus Pseudomonas was predominant in TK-treated soil (17.43%) followed by RKN-infested soil (3.90%) (Fig. 1e).

Metagenomic analysis of species distribution indicated that, the top 20 bacterial Species from the rhizosphere region were identified as Bacillus sp, Sphingomonas ub, B. megaterium, Pseudomonas borborid, Streptomyces sp, Solirubrobacter ub, Gaiella ub, Cellvibrio sp, Ensifer adhaerens, Pseudomonas sp, Rubrobacter sp, Mitsuaria chitosanitabida, Brevundimonas sp, Pseudonocardia ub, Shinella sp, Pluralibacter gergoviae and Vicinamibacteraceae sp (Fig. S6). Among them, Sphingomonas (1.3%), Vicinamibacterea (1.4%), Pseudonocardia, Solirubrobacter (2%%) and Gaiella (1.2%) were considered as uncultured bacterial species. The cultured bacterial species included Bacillus sp (6.9%), B. megaterium (0.3%), Pseudomonas borbori (1.5%), Streptomyces sp (2%), Ensifer adhaerens (1.04%), Pseudomonas sp (1.04%), Rubrobacter sp (1.04%), Mitsuaria chitosanitabida (1.2%), Brevundimonas sp (0.5%), Shinella sp (0.6%), and Pluralibacter gergoviae (0.5%). The RA of Bacillus sp was higher in RKN-infested soil, which accounted for 25% followed by T. koningiopsis TK and B. velezensis VB7 applied soil contributing towards 22.61% and 18.86%, respectively. The soil applied with B. velezensis VB7 had the maximum RA of 24.5% Sphingomonas species, whereas the lowest RA of 8.75% was noticed in untreated RKN-infested soil (Fig. 1f).

Diversity index of bacterial community

Shannon diversity index revealed that, the richness of bacterial communities was maximum in B. velezensis VB7-treated soil (1.4–2.4), followed by RKN-infested soils (1.3–2.2) (Fig. 2a). The richness was lowest in soils drenched with T. koningiopsis TK (1.3–2.0). The evenness vector index indicated that the most unique bacterial community group was observed in all the rhizosphere soil samples (P=<0.05) and had 0.1 variation between the samples from phylum to species level (Fig. 2b). The refraction curve indicated that, T. koningiopsis TK-treated samples had the higher richness of bacterial species, followed by B. velezensis VB7 with similar levels of diversified organisms (Fig. 2c). The RKN-infected soil samples had the lowest richness of the bacterial community. Thus, the present study clearly indicated that the diversity index of bioagents-treated samples had the highest richness of diversified bacterial populations when compared to RKN-infected soil samples. The higher diversity of bacterial species was observed in RKN-infested soil followed by bioagents amended soil, which was confirmed by Species Diversity Curve analysis (Fig. 2d). The Bray–Curti’s dissimilarity was visualized with a principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) to determine the distribution of microbial phyla obtained in rhizosphere soils of tomato plants. It indicated that the bacterial phylum ( – 0.006 to – 0.02) and genera (0;01 to 0.04), distributed in bioagents-treated soil samples were different from those of RKN-infested soil samples (Fig. 3a). Thus, the comparative analysis of our results indicated the largest variation in the distribution of microbial diversity between the samples in the present investigation. However, it was statistically non-significant with each other. At the class level, B. velezensis VB7-treated soil had slight variation of bacterial diversity with a range of 0.005, whereas T. koningiopsis TK and RKN-infested soil ( – 0.03) occupied a similar class of bacterial communities. All the three-rhizosphere soil reflected the same level of distribution of unique bacterial organisms at order, family and species level ( – 0.01 to 0.03). Similarly, the Jaccard algorithm index also revealed similar bacterial organisms with high richness in treated and untreated soil at phylum and order levels (Fig.3b). The bioagent-treated soils had more diversity, when compared to RKN-infected soils ( – 0.12) at the class level. The bacterial families with higher diversity were also observed in soils treated with B. velezensis VB7 ( – 0.109) than in T. koningiopsis TK and RKN soil samples. The soil applied with T. koningiopsis TK had more diversified (0.17) bacterial genera than B. velezensis VB7 and RKN soil, whereas RKN soil had high richness ( – 0.267) with dissimilar bacterial species.

Fig.2.

Alpha diversity indexes of bacterial communities with respect to various treatments a Shannon Index, b Evenness vector, c Refraction curve, d Species diversity curve, VB7 – B. velezensis VB7, TK – T. koningiopsis and RKN – Root Knot Nematode (Control). The richness of bacterial communities was represented in box plot with higher values indicating greater richness and lower values having lower richness of communities

Fig.3.

Beta diversity index for rhizospheric bacterial communities with respect to various treatments a Bray Curti’s – PcoA, b Jaccard index, VB7 – B. velezensis VB7, TK – T. koningiopsis and RKN – Root Knot Nematode (Control). The richness of bacterial communities were represented in box plot with higher values indicating greater richness and lower values having lower richness of communities

Distribution of fungal community in rhizosphere soil samples

Totally 14881 raw reads with an average of 4960 reads were generated using 18s rRNA ribosome gene amplification of ITS region. After quality filtering of the base, 13,575 sequences with an average of 4525 QC reads were retained. The quality-filtered reads were further size filtered to obtain the classified OUT to retain the 500–600 bp sequences of the ITS region. Totally 1679 sizes of filtered reads ranging from 516 to 624 were identified after processing of QC filtered reads. A total of 16 OTUs were identified as classified read. Among these, 6 (12.25%) for B. velezensis VB7, 5 (29.5%) for T. koningiopsis TK, and 5 (17.25%) for RKN-infested samples were used for further analysis. Eight Phylum, 11 Classes, 12 Orders, 14 Families, 16 Genera and 19 Species were present in all rhizosphere soil samples. Generally, Ascomycota (81.25%), Basidiomycota (12.5%) and Mucoromycota (6.25%), were relatively the major fungal phyla associated with all rhizosphere soil samples (Fig. S7). Ascomycota was the most dominant phylum with 100% RA in T. koningiopsis TK-treated soil, 83.33% of RA in B. velezensis VB7-treated soils, and the abundance was lowest in RKN-infested soil (60% of RA). The second dominant fungal phyla Basidiomycota was noticed in RKN-infested soil with a relative abundance of 40% (Fig. 4a).

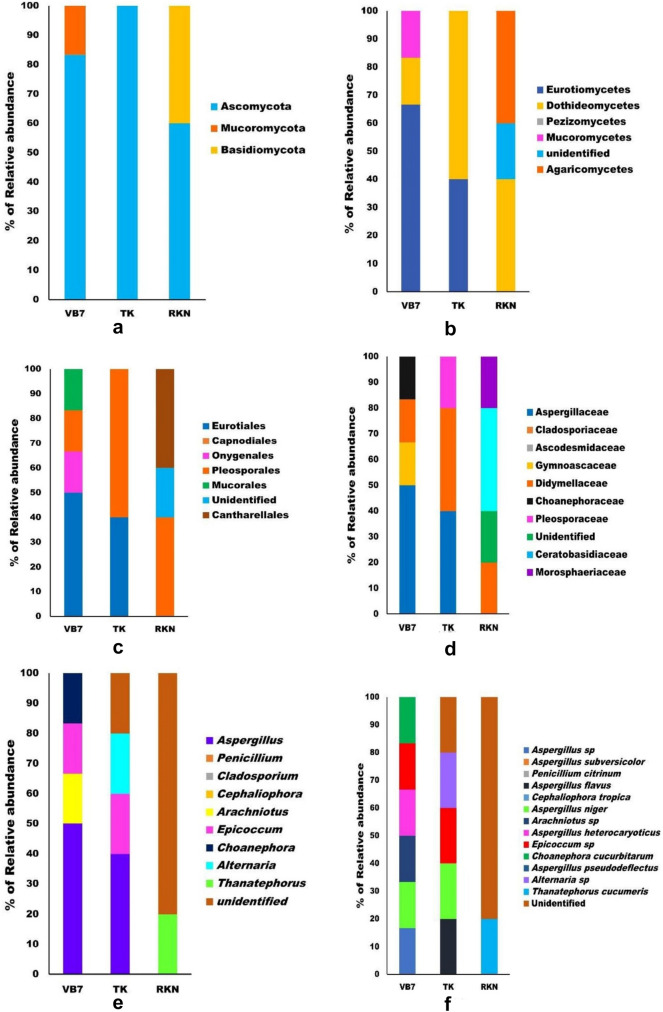

Fig.4.

Relative abundances (RA) of fungal taxa with respective to various treatments. a Relative abundances of fungal phyla, b Relative abundances of fungal classes, c Relative abundances of fungal orders, d Relative abundances of fungal families, e Relative abundances of fungal genera, and f Relative abundances of fungal Species, VB7 – B. velezensis VB7, TK – T. koningiopsis and RKN – Root Knot Nematode (Control)

The major fungal classes of Eurotiomycetes (37.5%), Dothideomycetes (37.5%), Agaricomycetes (12.5%), and Pezizomycetes (6.25%), were dominantly associated with all rhizosphere soil samples (Fig. S8). Eurotiomycetes population was observed in soil treated with bioagents with a relative frequency of 66.66% in B. velezensis VB7-treated soil and 40.00% of RA in T. koningiopsis TK applied soil sample. The relative abundance of Dothideomycetes class was 16.67% in B. velezensis VB7 soil, 60% in soil applied with T. koningiopsis TK and 40% in RKN-infested soil. The fungal population belonging to Agaricomycetes was prevalent only in RKN-infested soil samples representing 40% of abundance. Comparative analysis of diversity among different classes reflected that the soil treated with bioagents had the highest (16–40%) abundance of fungal communities than soil with RKN alone (Fig. 4b).

At the order level, Pleosporales (37.5%), Eurotiales (31.25%), Mucorales (6.25%), Cantharellales (12.25%), Onygenales (6.25%) and Pezizales (6.25%) were commonly distributed in all the soil samples (Fig. S9). Among them, Eurotiales had the maximum abundance of fungal order in B. velezensis VB7 applied soil accounting for 50% of the RA. But it was only 40% in T. koningiopsis TK applied soils, while RKN soil was devoid of Eurotiales. However, comparative analysis of all the soil samples pertaining to Cantharellales order indicated that the relative abundance was 40% in RKN-infested soil and the same was not observed in bioagents-treated soils. The soil treated with T. koningiopsis TK had the maximum abundance of 60% Pleosporales population, followed by 40% in RKN soil and only 16.67% in B. velezensis VB7 soil (Fig. 4c).

The major fungal family observed in various rhizosphere soil included Aspergillaceae (31.25%), Didymellaceae (25%), Ceratobasidiaceae (6.25%), Pleosporaceae (6.25%), Gymnoascaceae (6.25%), Choanephoraceae (6.25%) and Cladosporiaceae (Fig. S10). Among them, the fungi belonging to Aspergillaceae were prevalent only in bioagent-applied soil samples accounting for the maximum distribution of 50% and 40 % RA in B. velezensis VB7 and T. koningiopsis TK-treated soil samples, respectively. The family Didymellaceae was dominant in all samples, with a lesser abundance in B. velezensis VB7 (16.67%) soil samples. Interestingly, untreated soil with the maximum association of RKN had the highest mean distribution of Ceratobasidiaceae (40%) and Morosphaeriaceae (20%), whereas it was not present in bioagent applied soil samples (Fig. 4d).

Comparative analysis on the distribution of different genera, irrespective of different treatments indicated that fungal genera Aspergillus (31.25%), Arachniotus (6.25%), Epicoccum (12.25%), Choanephora (6.25%), Alternaria (6.25%), Thanatephorus (6.25%) were predominantly observed to habituate rhizosphere soils (Fig. S11). The relative abundance of the genus Aspergillus, ranked the highest in bioagent-treated soil samples than in RKN soil. Amid bioagents, T. koningiopsis TK soil had the maximum abundance of Aspergillus genus which accounted for 50% followed by Arachniotus, Epicoccum and Choanephora. The soil drenched with B. velezensis VB7 contained 40% RA of Aspergillus, 20% RA of Epicoccum and 20% RA of Alternaia genus. Further, 40% of unidentified fungal genera were commonly observed in all rhizosphere soil samples. Among them, 80 % of the unidentified fungal genera were noticed only in RKN soil (Fig. 4e).

The fungal species Aspergillus sp, Aspergillus subversicolor, Penicillium citrinum, Aspergillus flavus, Cladosporium, Cephaliophora tropica, Aspergillus niger, Arachniotus sp, Aspergillus heterocaryoticus, Epicoccum sp, Choanephora cucurbitarum, Aspergillus pseudodeflectus, Alternaria sp, Thanatephorus cucumeris were habituated in rhizosphere soil irrespective of different treatments (Fig. S12). Similarly, the comparative analysis of different species in the investigated rhizosphere soils indicated that B. velezensis VB7-treated soils had the maximum diversity of fungal species including Aspergillus niger, Arachniotus sp Aspergillus heterocaryoticus, Epicoccum sp and Choanephora cucurbitarum with 16.67% relative abundance. T. koningiopsis TK-treated soil had lesser diversity with greater abundance (20%) of fungal species A. flavus, Epicoccum and Alternaria sp. The soil applied with bioagents had higher microbial composition with greater abundance than RK-infested soil. Comparison of mycobiome between bioagents applied soil revealed that, the mycobiome in B. velezensis VB7-treated soil had the maximum diversity and more abundance than T. koningiopsis TK soil (Fig. 4f).

Diversity indexes of fungal community

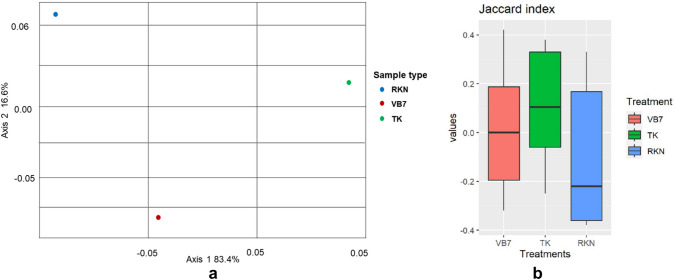

Alpha diversity was analysed, to assess the robustness of microbial diversity at all taxonomic levels. Based on diversity index analysis, the bioagents-treated soil samples had the maximum value with greater diversity and tended to contain more diverse microbial populations than RKN-infected soil samples. Shannon index revealed the abundant richness of fungal species in treated samples (1.04–0.9) as well as in untreated samples (P = < 0.05) (Fig. 5a). Evenness vector algorithm confirmed the distribution of evenness among fungal communities at Phylum and Order level (P = < 0.05) (Fig. 5b). But, the refraction curve indicated a significant increase of fungal species in B. velezensis VB7-treated soil with more diverse fungal species than RKN-infested and T. koningiopsis TK-treated soil (Fig. 5c). The Species Diversity Curve analysis revealed that the number of fungal species in soil varied with respect to each treatment. The soil treated with B. velezensis VB7 had the maximum species diversity when compared with T. koningiopsis TK soil and RKN-infested soil (Fig. 5d). The beta diversity analysis using Bray–Curtis’s dissimilarity explained that microbial phyla in the treated and untreated tomato rhizosphere soils had a similar fungal community with a significant difference in microbial populations between treated and untreated samples (Fig. 6a). Similarly, Jaccard algorithm index also revealed that treated soil had more diversified mycobiome with the maximum richness than untreated RKN-infested soil (Fig. 6b).

Fig.5.

Alpha diversity indexes of fungal communities with respect to various treatments a Shannon Index, b Evenness vector, c Refraction curve, d Species diversity curve, VB7 – B. velezensis VB7, TK – T. koningiopsis and RKN – Root Knot Nematode (Control). The richness of bacterial communities was represented in box plot with higher values indicating greater richness and lower values having lower richness of communities

Fig.6.

Beta diversity index for rhizosphere fungal communities with respect to various treatments a Bray Curti’s – PcoA, b Jaccard index , VB7 – B. velezensis VB7, TK – T. koningiopsis and RKN – Root Knot Nematode (Control). The richness of bacterial communities were represented in box plot with higher values indicating greater richness and lower values having lower richness of communities

Efficiency of bioagents against M. incognita in the field condition

The bio-efficacy of bio-agents against RKN was assessed in a tomato field endemic to the infection of M. incognita. Tomato plants treated with B. velezensis VB7 had a maximum plant height of 122.76 cm at 70 DAT with an average fruit yield of 22.5t/ha coupled with a low gall index of 1 and with reduced gall numbers when compared with untreated plants. The plant height in T. koningiopsis TK-treated plants was 113.29 cm at 70 DAT, with an average yield of 21.7t/ha. The mean gall index was 1 and thus both were not found to differ significantly from each other. However, untreated control plants had a minimum plant height of 78.53cm at 70 DAT, with a mean yield of 11.2t/ha. Ultimately, T. koningiopsis TK and B. velezensis VB7-treated plants had 60% reduction of RKN infection over control (Table 1).

Table 1.

Efficiency of bioagents against M. incognita in the field condition

| Treatments | Plant height (cm) | Root Gall Index | Efficacy of bioagent (%) | Yield/ha | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 DAT | 40 DAT | 55 DAT | 70 DAT | ||||

| T 1—B. velezensis VB7(@1% conc.) + RKN | 25.19 ± 0.2a | 62.73 ± 0.8a | 92.51 ± 0.3a | 122.76 ± 1.5a | 1b | 80 | 22.5a |

| T 2—Trichoderma koningiopsis (@1% conc.) + RKN | 21.84 ± 0.09b | 58.21 ± 0.2b | 89.15 ± 1.4a | 113.29 ± 0.0b | 1b | 80 | 21.7b |

| T3—Untreated control (RKN) | 14.93 ± 0.3c | 38.05 ± 0.5c | 65.19 ± 1.4b | 78.53 ± 1.7c | 5a | – | 11.2c |

Data are presented as mean ± SE of three independent biological replicates for each treatment. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) according to one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple range test

Discussion

The richness and diversity of soil microbes play an important role in regulating soil structure, and productivity towards the suppression of inimical plant pathogens. The tomato rhizosphere soil was rich in microbial communities comprising bacteria, fungi, and archaea (Babalola et al. 2022). Certain beneficial microbes are vital for boosting agricultural productivity and soil fertility for enhancing resistance to pathogen persistence. Interaction between microbial bio-agents, plants, and nematodes in rhizosphere soil is highly complex. Furthermore, rhizosphere soil possesses diverse and widely distributed bio-control agents producing secondary metabolites offered exciting prospects in the search for biomolecules with various biological and nematicidal potentials.

We analysed the diversity of microbiome in soil samples through a metagenomics approach to alleviate limitations. By utilizing the advantages of these sequencing strategies, we evaluated the distribution and diversity of the microbiome in treated as well as untreated rhizosphere soil from RKN-infested tomato field trials. As predominant members of the rhizosphere microbial community, Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria were suggested to be dynamic taxa associated with plant disease suppression using DNA metagenomics (Mendes et al. 2013). Similarly, our results indicated that Proteobacteria, Firmicutes Actinobacteria, Cyanobacteria, and Chloroflexi were dominant with a greater abundance of the bacterial population (1–5%) in bioagent-treated soil samples when compared to RKN-infected soil. Abundance of various bacterial phyla in healthy tomato roots will regulate the beneficial interactions between the rhizosphere microbiome and host plants and thus promote plant growth and yield (Adedayo et al. 2022; Cordero et al. 2020; Wen et al. 2016; Dong et al. 2019; Zhou et al. 2021). Abundance of Acidobacteria, Gemmatimonadota, Myxococcota, and Bacteroidota were higher in RKN-infected rhizosphere soil (Adedayo et al. 2022; Zhou et al. 2021). In accordance with it, our results also emphasized that bio-agent-treated rhizosphere soils had the maximum diversity of bacterial population, which might have contributed towards the suppression of RKN in the tomato rhizosphere. However, the diversity was lower in untreated control, leading to the maximum infestation of RKN as observed in the present investigation (Zhou et al. 2021). Similarly, Zhao et al. (2023a, b, c) reported that, the maximum abundance and increased activity of Actinobacteria might be responsible for the suppression of RKN. Rhodobacteriales, Rhizobiales and Sphingomonadales belong to the class Alpha Proteobacteria, Bacillales and Paenibacillales belonging to the class Bacilli were dominant in bioagent-treated soil samples, with a lower range in nematode-infested soil. Lei et al. (2019) also found that Rhizobiales, Rhodospirillales, Sphingomonadales, Burkholderiales, Nitrosomonadales, Myxococcales, and Xanthomonadales were noticed in the rhizosphere soil of different plants which abides with the present investigation. Further, the above-mentioned genera were already observed in the rhizosphere region and reported as a biocontrol agent against nematodes through metagenomic approaches (Huang et al. 2022; Tian et al. 2022; Zhou et al. 2021). Thus, the present observations also confirmed that, the abundance of the genera Bacillus, Sphingomonas, Pseudomonas, and Streptomyces might have protected the rhizosphere region from the infection of RKN. Recent reports by Tian et al. (2022) and Yin et al. (2021) elucidated that different species of Bacillus could enhance resistance in the plants and thus reduce M. incognita infection by activating several defense-responsive genes in cucumber. The Microbacterium, Sphingopyxis, Brevundimonas, Acinetobacter, and Micrococcus genera identified from the cuticle of M. hapla in soils suppressed invasion of J2 into the roots (Topalović et al. 2019).

The main fungal Phyla of Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Mucoromycota were detected in all rhizosphere soils. Our result was also supported by the recent research findings on the occurrence of similar Phyla in tomato rhizosphere soils that serve as bioagents for the suppression of soil-borne pathogens (Hajji-Hedfi et al. 2019). Apart from the diversity of bacterial microbiome, comparison of mycobiome also emphasized the increase in the diversity of fungal flora in the tomato rhizosphere. Similarly, Naz et al. (2021) indicated that, A. flavus had nematicidal property through the production of secondary metabolites in cucumber soil rhizosphere, which in turn affected nematode reproduction in plant roots and rhizosphere, either alone or in combinations with other biocontrol agents. Similarly, our investigations also clearly indicated the relative abundance of Aspergillus genera responsible for the suppression of RKN. Likewise, diversity index indicated that, the RKN rhizosphere soil had higher richness of bacterial and fungal species in microbial communities leading to a higher infestation of nematodes by bacterial and fungal species. The presence of more diverse beneficial microbial communities in soils could reduce RKN infection in crop plants. High-throughput amplicon sequencing of fungal and bacterial communities from cysts in soil suppressive to H. glycines, revealed that suppressiveness was associated with the change in the relative abundance of diverse bacterial and fungal taxa, especially P. chlamydosporia, Exophiala spp., and Clonostachys rosea (Hu et al. 2017). Similarly, we also witnessed the diversity in the relative abundance of bacterial and fungal genera. Moreover, the abundance of bacteria was higher in RKN-infested rhizosphere soil samples, indicating that the bacteria pertaining to Bacillus genera might have proliferated using RKN as its prey. Topalovic et al. (2020) explained that several bacterial and fungal genera had antagonistic properties against PPN in suppressive soil.

In our study, the tomato plants applied with VB7, significantly enhanced the plant height by 39% and increased the fruit yield by 42% when compared to untreated plants. In accordance with it, (Tian et al. 2022) reported the lesser number of root galls in bioagents-treated tomato roots. They have reported that the application of B. velezensis Strain Bv-25 to cucumber plants lowered the root gall index by 61.6%, enhanced plant height by 14.4%, and boosted yield by 36.5% than untreated control in field conditions. Similarly, soil drenching with B. velezensis BZR 277 (1 × 109 CFU/mL) on to cucumber plants enhanced the plant growth and reduced the number of galls by 13 times and increased the yield by 4.6–45.8% when compared to control plants (Asaturova et al. 2022). The other Bacillus genus has been widely described to effectively reduce RKNs in both greenhouse and field experiments, such as, B. subtilis (Cao et al. 2019; Das et al. 2021), B. atrophaeus (Ayaz et al. 2021), B. cereus (Yin et al. 2021) and B. altitudinis (Ye et al. 2022). In the present study, the soil drenched with TK in the rhizosphere region significantly enhanced the plant height by 36% and increased the fruit yield by 38.12% when compared to the untreated plants. A lesser number of root galls were observed in bioagents-treated tomato roots. Our results suggested that the application of VB7 and TK could boost plant growth as well as enhance resistance levels to suppress the infestation of M. incognita in tomato plants. Thus, augmentation of soil with antagonistic Bacillus spp., or Trichoderma spp., might change the microbiome profile in the rhizosphere resulting in the creation of a conducive environment for better growth, immune response and yield increase in the plants. Previous reports by Sreenayana et al. (2022), supported our findings and elucidated that application of T. koningiopsis TRI 41 was effective in the suppression of RKN by significantly reducing egg hatching by 71.51% and increased juvenile mortality by 75%. The tomato plants inoculated with T. haraziaum reduced the formation of root galls by 52.38%, reduced the penetration of nematodes, females (68%) and egg mass (43%). Besides, fungal and bacterial antagonists enhanced plant growth and stimulated the plant’s systemic resistance (Rahman et al. 2023). Application of T. harzianum reduced the severity of Fusarium wilt as well as the infestation of M. javanica in tomato (Mwangi et al. 2019).

In summary, the application of VB7 and TK reduced the incidence of root-knot nematodes in tomatoes under field conditions. The investigation of rhizosphere microbiome assemblages demonstrated that, the applied bio-agents compete with other naturally occurring rhizosphere microbial communities. Bacterial phyla of Proteobacteria, Firmicutes and Actinobacteria and fungal phyla, Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and Deuteromycota had the highest relative abundance, which might have contributed to the engineering of rhizosphere with fungal and bacterial community leading to the suppression of RKN infection in tomato. Further, in field conditions, the bioagents-treated tomato plants enhanced the plant growth, increased yield, and reduced the infestation of M. incognita. Thus, the present investigation indicated that both B. velezensis VB7 and T. koningiopsis TK could be explored as effective biocontrol agents for rhizosphere engineering with beneficial microbiomes for the management of M. incognita.

Conclusion

In this study, we investigated microbial diversity in nematode-infested tomato plants treated with B. velezensis VB7 and T koningiopsis TK to observe the responses of bacterial biome and mycobiome during nematode pathogenesis and to demonstrate their biological functions during interactions of microbes, plants, and nematodes. Comparative community analysis of rhizosphere microbiome in nematode-associated and bioagents applied rhizosphere soil showed that nematode pathogenesis was decreased due to the abundance of the predominant bioagents genera comprising of Bacillus, Streptomyces and Aspergillus. Because, they were known to enhance a vast diversity of mechanisms against plant parasitic nematodes. Under field conditions, the bioagents-treated tomato plants enhanced the plant growth, increased yield, and reduced M. incognita infestation. Forthcoming attribution and exploration of the root gall-associated microbial community and their functionalities with network analysis in plant parasitic nematode parasitism will help us better to understand the complex interaction between microbe–plant–pathogen and will also enhance the agricultural practice by developing novel strategies to manage PPN efficiently by altering the diversity of the microbiome.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are all provided in this manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Agricultural Bioinformatics – BIC facility available at the Department of Plant Molecular Biology and Bioinformatics, Centre for Plant Molecular biology and Biotechnology, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India. The authors acknowledge the Department of Plant Pathology, Centre for Plant Protection Studies, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India for providing facilities. The authors extends their appreciation to Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2023R979), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for financial assistance.

Author contributions

SN conceptualized the research and was associated with technically guiding and executing the research. KV prepared the manuscript and carried out the data analysis. SN and NS edited the manuscript. PJ provided the resources for the experiment. GP performed the metagenomic analysis. NS, KP and MA have supported the analysis of data.

Data availability

Further information regarding the manuscript can be furnished on the basis of request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Abd-Elgawad MM. Plant-parasitic nematodes and their biocontrol agents: current status and future vistas. Manag Phytonematodes. 2020 doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-4087-5_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abd-Elgawad MM, Askary TH. Fungal and bacterial nematicides in integrated nematode management strategies. Egypt J Biol Pest Control. 2018;28(1):1–24. doi: 10.1186/s41938-018-0080-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adedayo AA, Fadiji AE, Babalola OO. Plant health status affects the functional diversity of the rhizosphere microbiome associated with solanum lycopersicum. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2022 doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.894312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akanmu AO, Babalola OO, Venturi V, Ayilara MS, Adeleke BS, Amoo AE, Sobowale AA, Fadiji AE, Glick BR. Plant disease management: leveraging on the plant-microbe-soil interface in the biorational use of organic amendments. Front Plant Sci. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.700507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asaturova AM, Bugaeva LN, Homyak AI, Slobodyanyuk GA, Kashutina EV, Yasyuk LV, Sidorov NM, Nadykta VD, Garkovenko AV. Bacillus velezensis strains for protecting cucumber plants from root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita in a greenhouse. Plants. 2022;11(3):275. doi: 10.3390/plants11030275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayaz M, Ali Q, Farzand A, Khan AR, Ling H, Gao X. Nematicidal volatiles from Bacillus atrophaeus GBSC56 promote growth and stimulate induced systemic resistance in tomato against Meloidogyne incognita. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9):5049. doi: 10.3390/ijms22095049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babalola OO, Adedayo AA, Fadiji AE. Metagenomic survey of tomato rhizosphere microbiome using the shotgun approach. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2022;11(2):e01131–e1221. doi: 10.1128/mra.01131-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berliner J, Ganguly AK, Kamra A, Sirohi A, VP D (2023) Effect of elevated carbon dioxide on population growth of root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita in tomato. Indian Phytopathol 10.1007/s42360-022-00584-8

- Bertola M, Ferrarini A. Visioli G (2021) Improvement of soil microbial diversity through sustainable agricultural practices and its evaluation by omics approaches: a perspective for the environment, food quality and human safety. Microorganisms. 2021;9(7):1400. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9071400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray JR, Curtis JT. An ordination of the upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin. Ecol Monogr. 1957;27(4):326–349. doi: 10.2307/1942268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Jiao Y, Yin N, Li Y, Ling J, Mao Z, Yang Y, Xie B. Analysis of the activity and biological control efficacy of the Bacillus subtilis strain Bs-1 against Meloidogyne incognita. Crop Prot. 2019;122:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2019.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Peña AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7(5):335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetintas R, Kusek M, Fateh SA. Effect of some plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria strains on root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita, on tomatoes. Egypt J Biol Pest Control. 2018;28(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s41938-017-0008-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero J, de Freitas JR, Germida JJ. Bacterial microbiome associated with the rhizosphere and root interior of crops in Saskatchewan. Canada Can J Microbiol. 2020;66(1):71–85. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2019-0330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Abdul Wadud M, Khokon AM. Functional evaluation of culture filtrates of Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas fluorescens on the mortality and hatching of Meloidogyne javanica. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28:1318–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong CJ, Wang LL, Li Q, Shang QM. Bacterial communities in the rhizosphere, phyllosphere and endosphere of tomato plants. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0223847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhady A, Giné O, Topalovic S, Jacquiod SJ, Sorensen FJ, Sorribas H (2017) Microbiomes associated with infective stages of root-knot and lesion nematodes in soil. PLoS One 12(5):e0177145. 10.1371/journal.pone.0177145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- El-Nuby AS, Afia AI, Alam EA (2021) In vitro evaluation of the toxicity of different extracts of some marine algae against root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita). Pakistan J Phytopathol 33: 55–66. 10.33866/phytopathol.033.01.0676

- Fadiji AE, Ayangbenro AS, Babalola OO. Unveiling the putative functional genes present in root-associated endophytic microbiome from maize plant using the shotgun approach. J Appl Genet. 2021;62:339–351. doi: 10.1007/s13353-021-00611-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H, Yao M, Wang H, Zhao D, Zhu X, Wang Y, Liu X, Duan Y, Chen L. Isolation and effect of Trichoderma citrinoviride Snef 1910 for the biological control of root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20:1–1. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-01984-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick BR, Gamalero E. Recent developments in the study of plant microbiomes. Microorganisms. 2021;9(7):1533. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9071533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajji-Hedfi L, M’Hamdi-Boughalleb N, Horrigue-Raouani N. Fungal diversity in rhizosphere of root-knot nematode infected tomatoes in Tunisia. Symbiosis. 2019;79:171–181. doi: 10.1007/s13199-019-00639-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Samac DA, Liu X, Chen S. Microbial communities in the cysts of soybean cyst nematode affected by tillage and biocide in a suppressive soil. Appl Soil Ecol. 2017;119:396–406. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.07.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Zhao W, Qiao H, Li C, Sun L, Yang R, Ma X, Ma J, Song S, Wang S. SlWRKY45 interacts with jasmonate-ZIM domain proteins to negatively regulate defense against the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita in tomato. Hortic Res. 2022;5:9. doi: 10.1093/hr/uhac197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim DS, Ghareeb RY, Abou El Atta DA, Azouz HA (2021) Nematicidal properties of methanolic extracts of Two marine algae against tomato root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita. J Plant Prot Pathol 12(2):137–44. 10.21608/JPPP.2021.154414

- Khan RA, Najeeb S, Hussain S, Xie B, Li Y (2020) Bioactive secondary metabolites from Trichoderma spp. against phytopathogenic fungi. Microorganisms 10.3390/microorganisms8060817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lamelas A, Desgarennes D, López-Lima D, Villain L, Alonso-Sánchez A, Artacho A, Latorre A, Moya A, Carrion G. The bacterial microbiome of Meloidogyne based disease complex in coffee and tomato. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:136. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei S, Xu X, Cheng Z, Xiong J, Ma R, Zhang L, Yang X, Zhu Y, Zhang B, Tian B. Analysis of the community composition and bacterial diversity of the rhizosphere microbiome across different plant taxa. Microbiologyopen. 2019;8(6):e00762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Xiong W, Zhang R, Hang X, Wang D, Li R, Shen Q. Continuous application of different organic additives can suppress tomato disease by inducing the healthy rhizospheric microbiota through alterations to the bulk soil microflora. Plant Soil. 2018;423:229–240. doi: 10.1007/s11104-017-3504-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Fu G, Li Y, Zhang S, Ji X, Qiao K. Biocontrol Efficacy of Bacillus methylotrophicus TA-1 Against Meloidogyne incognita in Tomato. Plant Dis (ja) 2023 doi: 10.1094/PDIS-12-22-2801-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes R, Garbeva P, Raaijmakers JM. The rhizosphere microbiome: significance of plant beneficial, plant pathogenic, and human pathogenic microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol Reviews. 2013;37(5):634–663. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi MW, Muiru WM, Narla RD, Kimenju JW, Kariuki GM. Management of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici and root-knot nematode disease complex in tomato by use of antagonistic fungi, plant resistance and neem. Biocontrol Sci Technol. 2019;29(3):229–38. doi: 10.1080/09583157.2018.1545219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naz I, Khan RA, Masood T, Baig A, Siddique I, Haq S. Biological control of root knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita, in vitro, greenhouse and field in cucumber. Biol Control. 2021;152:104429. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2020.104429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phani V, Khan MR, Dutta TK. Plant-parasitic nematodes as a potential threat to protected agriculture: current status and management options. Crop Prot. 2021;144:105573. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2021.105573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M, Borah SM, Borah PK, Bora P, Sarmah BK, Lal MK, Tiwari RK, Kumar R. Deciphering the antimicrobial activity of multifaceted rhizospheric biocontrol agents of solanaceous crops viz., Trichoderma harzianum MC2, and Trichoderma harzianum NBG. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1141506. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1141506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, Sahl JW. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(23):7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon CE. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst Tech J. 1948;27(3):379–423. doi: 10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R, Munns K, Alexander T, Entz T, Mirzaagha P, Yanke LJ, Mulvey M, Topp E, McAllister T. Diversity and distribution of commensal fecal Escherichia coli bacteria in beef cattle administered selected subtherapeutic antimicrobials in a feedlot setting. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(20):6178–6186. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00704-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreenayana B, Vinodkumar S, Nakkeeran S, Muthulakshmi P, Poornima K. Multitudinous potential of Trichoderma species in imparting resistance against F. oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum and Meloidogyne incognita disease complex. J Plant Growth Regul. 2022;41(3):1187–206. doi: 10.1007/s00344-021-10372-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su L, Zhang L, Nie D, Kuramae EE, Shen B, Shen Q. Bacterial tomato pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum invasion modulates rhizosphere compounds and facilitates the cascade effect of fungal pathogen Fusarium solani. Microorganisms. 2020;8(6):806. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8060806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suneeta P, Aiyanathan KE, Nakkeeran S (2017). Evaluation of Trichoderma spp. and Fungicides in the Management of Collar Rot of Gerbera Incited by Sclerotium rolfsii. J Pure Appl Microbiol 11(2):1161–8. 10.22207/JPAM.11.2.63

- Tian BY, Cao Y, Zhang KQ. Metagenomic insights into communities, functions of endophytes and their associates with infection by root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita, in tomato roots. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):17087. doi: 10.1038/srep17087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian XL, Zhao XM, Zhao SY, Zhao JL, Mao ZC. The biocontrol functions of Bacillus velezensis strain Bv-25 against Meloidogyne incognita. Front Microbiol. 2022 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.843041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topalović O, Elhady A, Hallmann J, Richert-Pöggeler KR, Heuer H. Bacteria isolated from the cuticle of plant-parasitic nematodes attached to and antagonized the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne hapla. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–3. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47942-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topalović O, Hussain M, Heuer H. Plants and associated soil microbiota cooperatively suppress plant-parasitic nematodes. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:313. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viljoen JJ, Labuschagne N, Fourie H, Sikora RA. Biological control of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita on tomatoes and carrots by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Trop Plant Pathol. 2019;44:284–291. doi: 10.1007/s40858-019-00283-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vinodkumar S, Nakkeeran S, Renukadevi P, Mohankumar S. Diversity and antiviral potential of rhizospheric and endophytic Bacillus species and phyto-antiviral principles against tobacco streak virus in cotton. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2018;267:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2018.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen XY, Dubinsky E, Yao WU, Rong Y, Fu CH. Wheat, maize and sunflower cropping systems selectively influence bacteria community structure and diversity in their and succeeding crop’s rhizosphere. J Integr Agric. 2016;15(8):1892–1902. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(15)61147-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang N, Lawrence KS, Donald PA. Biological control potential of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria suppression of Meloidogyne incognita on cotton and Heterodera glycines on soybean: A review. J Phytopathol. 2018;166(7–8):449–458. doi: 10.1111/jph.12712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Wan JW, Yao JH, Feng H, Wei LH. Effects of Bacillus cereus strain Jdm1 on Meloidogyne incognita and the bacterial community in tomato rhizosphere soil. 3 Biotech. 2018;8:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1348-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, Wang JY, Liu XF, Guan Q, Dou NX, Li J, Zhang Q, Gao YM, Wang M, Li JS, Zhou B (2022) Nematicidal activity of volatile organic compounds produced by Bacillus altitudinis AMCC 1040 against Meloidogyne incognita. Arch Microbiol 204(8):521. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1500056/v1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yin N, Zhao JL, Liu R, Li Y, Ling J, Yang YH, Xie BY, Mao ZC. Biocontrol efficacy of Bacillus cereus strain Bc-cm103 against Meloidogyne incognita. Plant Dis. 2021;105(8):2061–2070. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-03-20-0648-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N, Zhu L, Liu M, He L, Xu H, Jia J. Enzyme-responsive lignin nanocarriers for triggered delivery of abamectin to control plant root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne incognita) J Agric Food Chem. 2023;71(8):3790–3799. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c07466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Lin C, Tan J, Yang P, Wang R, Qi G. Changes of rhizosphere microbiome and metabolites in Meloidogyne incognita infested soil. Plant Soil. 2023;483(1–2):331–353. doi: 10.1007/s11104-022-05742-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Lin C, Tan J, Yang P, Wang R, Qi G. Changes of rhizosphere microbiome and metabolites in Meloidogyne incognita infested soil. Plant Soil. 2023;483(1–2):331–353. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Liu B, Zhu Y, Wang J, Zhang H, Wang Z. Bacterial community diversity associated with the severity of bacterial wilt disease in tomato fields in southeast China. Can J Microbiol. 2019;65(7):538–549. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2018-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Feng H, Schuelke T, De Santiago A, Zhang Q, Zhang J, Luo C, Wei L. Rhizosphere microbiomes from root knot nematode non-infested plants suppress nematode infection. Microb Ecol. 2019;78:470–481. doi: 10.1007/s00248-019-01319-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Wang JT, Wang WH, Tsui CK, Cai L. Changes in bacterial and fungal microbiomes associated with tomatoes of healthy and infected by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici. Microb Ecol. 2021;81:1004–1017. doi: 10.1007/s00248-020-01535-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are all provided in this manuscript.

Further information regarding the manuscript can be furnished on the basis of request.