Abstract

Tuning the electronic properties of transition metals using pyrophosphate (P2O7) ligand moieties can be a promising approach to improving the electrochemical performance of water electrolyzers and supercapacitors, although such a material’s configuration is rarely exposed. Herein, we grow NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 nanoparticles on conductive Ni-foam using a hydrothermal procedure. The results indicated that, among all the prepared samples, FeP2O7 exhibited outstanding oxygen evolution reaction and hydrogen evolution reaction with the least overpotential of 220 and 241 mV to draw a current density of 10 mA/cm2. Theoretical studies indicate that the optimal electronic coupling of the Fe site with pyrophosphate enhances the overall electronic properties of FeP2O7, thereby enhancing its electrochemical performance in water splitting. Further investigation of these materials found that NiP2O7 had the highest specific capacitance and remarkable cycle stability due to its high crystallinity as compared to FeP2O7, having a higher percentage composition of Ni on the Ni-foam, which allows more Ni to convert into its oxidation states and come back to its original oxidation state during supercapacitor testing. This work shows how to use pyrophosphate moieties to fabricate non-noble metal-based electrode materials to achieve good performance in electrocatalytic splitting water and supercapacitors.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s11671-023-03937-y.

Keywords: Transition metal pyrophosphate, Electrocatalysts, OER, HER, Water-splitting, Electrolyzer, Supercapacitor

Introduction

The current agenda of finding renewable energy resources to meet the global energy crisis is one of the most pressing research hotspots. In this context, the development of efficient, clean, and sustainable energy technologies, such as electrolyzers and supercapacitors, is considered the most promising approach [1–3]. However, these systems require low-cost and highly efficient electrode materials for commercialization [4–6]. To date, electrode material research has concentrated on discovering materials that can meet both low- and high-energy needs while being inexpensive, highly active in water electrocatalysis, displaying high specific energy and power density in supercapacitors, and having great cycling stability [7, 8]. Within this framework, transition metal oxides [RuO2, MnO2, Co3O4, hydroxides (Ni(OH)2, Co(OH)2), sulfides (MoS2, Co9S8), and phosphides (Ni2P)] have been tested as electrode materials in these devices [9–15]. However, these materials still have limited electrochemical performance and stability in water electrolyzers and supercapacitors, which may be due to poor alteration of transition metal electronic characteristics by corresponding oxide, sulfide, and phosphide frameworks [15–20].

Recently, it was hypothesized that the pyrophosphate framework would demonstrate exceptional electronic alteration of transition metal atoms as well as possess outstanding physical and chemical properties. For example, Mn, Co, and Ni transition metals were integrated into a pyrophosphate framework, forming Mn2P2O7, Co2P2O7, and Ni2P2O7. These materials have attracted substantial attention from researchers for improved water-splitting performance and energy storage capacity [21, 22]. For instance, sodium ion-doped, and amorphous Ni2P2O7, and porous Co2P2O7, having different morphologies, were constructed and found to be promising materials in energy storage applications [23]. Although pyrophosphate-based materials worked well and showed promising electrochemical performance in energy storage devices, it would be ideal to develop a simple and economical way to boost their electrochemical water oxidation performance [24].

Besides, disordered and defect-rich amorphous nanostructured materials with high mechanical and electric isotropy and low crystallinity can have interesting physico-chemical properties. Amorphous nanostructures permit the deeper dispersion of the electrolyte’s ionic species to approach the active components, benefiting from their charge storage features in supercapacitors compared to similar crystallized materials [25–28]. With the exception of the substantial amount of work that has been done on transition metal integrated pyrophosphate materials for applications involving energy storage, these materials have been inadequately investigated in electrocatalytic water splitting. In addition, theoretical research on pyrophosphate electrode materials is still limited to investigating the underlying chemistry of the influence that the framework of pyrophosphate has on transition metal atoms [29].

Therefore, in light of these considerations and to investigate the possible applications of metal-pyrophosphate-type materials in both energy conversion and storage, the authors directly grown NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 nanoparticles for the first time on conductive Ni-foam using the hydrothermal approach, and the electrocatalytic and electrochemical characterizations were investigated under the prelims of surface phenomena. Since we have utilized urea during synthesis, it also reacts with Ni-foam and it is relevant to errors if we calculate mass loading on the Ni-foam. Thus, we have not proceeded with this study on the basis of mass-loading. However, we highly consider mass-loading as a crucial parameter to report for electrochemical explanation. Therefore, we already measured the mass-loading before testing. The FeP2O7 composite showed the lowest overpotential of 220 and 241 mV @10 mA/cm2 for the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and hydrogen evolution reaction (HER). Further, the NiP2O7 composite was found to have the highest specific capacitance as well as the best cycle stability for all the composites. According to theoretical studies, the optimal electronic coupling of the Fe site with the pyrophosphate framework is what contributes to the enhancement of FeP2O7's overall electronic properties and benefits to its electrochemical performances in water splitting.

Experimental study

Materials

Nickel foam (NF) was purchased from MTI-KJ Group, Richmond, California; nickel nitrate [Ni(NO3)2] and cobalt nitrate [Co(NO3)2] were ordered from STREM Chemicals; ferrous nitrate [Fe (NO3)2] and urea (CH4N2O) were acquired from ACROS Organics; deionized (D.I.) water was purchased from Fischer Scientific, USA; and sodium dihydrogen phosphate (NaH2PO4) was ordered from Sigma Aldrich.

Preparation of the catalytic samples

Typically, a two-step protocol was followed for the preparation of transition metal-based pyrophosphate nanoparticles grown on the Ni-foam. In the first step of the synthesis, 3 mmol of sodium dihydrogen phosphate, 240 mg of urea, and 20 ml of de-ionized water were added with 1 mmol of nickel nitrate, cobalt nitrate, and ferrous nitrate precursors in three different beakers, respectively, and the resulting solutions were sonicated for 5 min at 25 °C to ensure homogeneity of composition. In the second step, all the prepared solutions and the Ni-foams with an area of 2 × 2 cm2 were transferred into 50 ml Teflon autoclaves and treated at 180 °C for 12 h. After cooling down, the obtained Ni foams supported by NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 arrays were washed with DI water many times before being placed in an oven for 12 h to dry.

Physical characterization

The synthesised materials underwent characterization using an X-ray diffractometer (Shimadzu XRD-6000 with Cu-Kα source and 1.54 Å wavelength) within the angular range of two theta degrees from 10 to 80. The investigation involved the examination of morphology, elemental mapping, and energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDAX, Oxford) utilising field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) (SU 5000 – Hitachi). The X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were collected at Kratos Axis Ultra-DLD spectrometer (employing Al Kα,x non-monochromatic radiation of approx. 1 mm). Elemental quantitative analysis was performed by calculating the area under the elemental peaks by fitting a curve to the data.

Electrochemical characterization

The electrochemical experiments were conducted on a Versa STAT 4-500 electrochemical workstation using a three-electrode device. Due to the fact that the material was not grown directly on Ni-foam and mass-loading of material on Ni-foam was not considered for this study, the potentiodynamic and electrochemical supercapacitor investigation was done on the basis of surface area analysis. However, mass loading is an important parameter during electrochemical investigations therefore, we have measured mass-loading of the material on the Ni-foam. The mass-loading of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 are 26.3, 31.8, and 21.9 mg/cm2, respectively [30]. To analyze the catalytic activity, 1 M KOH solution was used as an electrolyte, with a saturated calomel electrode, graphite rod, and a prepared electrode serving as a reference electrode, counter electrode, and working electrode, respectively. The electrochemical characterization of HER and OER was performed using linear sweep voltammetry; all the polarization curves were plotted after the iR correction. The degree of iR compensation for NiP2O7, CoP2O7 and FeP2O7 samples was found to be 15%, 13%, and 12%, respectively [31–33]. Tafel slope, turnover frequency (TOF), electrochemical active surface area (ECSA), roughness factor (RF), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and chronoamperometry (CA) were also performed to evaluate the performance of the prepared samples. Additionally, for the energy storage characteristics, 3 M KOH solution was used as an electrolyte with a mercury/mercury oxide (Hg/HgO) electrode, platinum wire, and a prepared electrode serving as a reference electrode, counter electrode, and working electrode. The supercapacitor properties were investigated by accompanying cyclic voltammetry (CV), galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD), and durability tests over 5000 cycles using a three-electrode system. The turnover frequency (TOF) value was calculated using the formula [34, 35];, where, J, NA, n, F, and τ stands for the current density (A/cm2), Avogadro number (6.022 × 1023 mol−1), transferred electrons during product formation (for O2, it is 4, and H2, it is 2), Faraday constant (96,485 C), and surface concentration of active sites, respectively.

Theoretical studies

To perform the theoretical calculations, the primitive unit cell with lattice parameters of a = 10.14 Å and b = 12.22 Å, having 20 Å vacuum space, was constructed for each catalytic material. The Quantum Espresso calculation software was used to do theoretical computations on the constructed models by employing the generalized-gradient approximation (GGA) theory in association with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional and the double numerical (+) polarisation functional basis set. To calculate the density of states (DOS) for the constructed models, the convergence limits for force (0.05 eV) and energy (250 eV) were set under the plane-wave expansion of the electronic wave function (10−5 eV). After thoroughly optimizing the constructed models, the adsorption energies for OER and HER adducts were calculated using the following Eq. 1.

| 1 |

where E(catalyst-reactant), E(catalyst), and E(reactant) are the energies of catalyst-reactant adduct, catalyst, and reactant, respectively.

Results and discussions

Synthesis, and characterization of the prepared samples

In this study, to investigate the electrochemical performance of transition metal-based pyrophosphate-type materials towards electrocatalytic water oxidation and supercapacitors, the FeP2O7, CoP2O7, and NiP2O7 nanoparticles were grown on conductive Ni-foam, following a two-step strategy, as shown in Fig. 1. First of all, all the prepared composite materials were characterized using multiple analytical techniques and then investigated for the electrochemical performances using electrochemical techniques.

Fig. 1.

A schematic representation of a two-step preparation of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 in hydrothermal

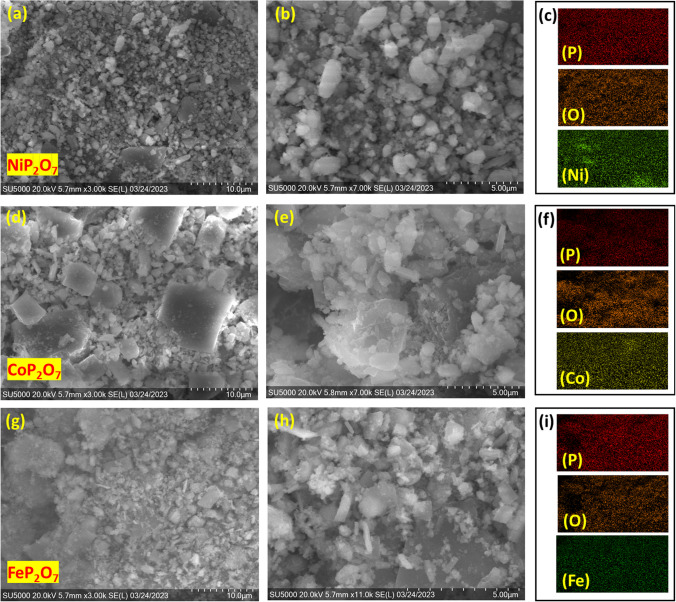

The morphology of the prepared composites, FeP2O7, CoP2O7, and NiP2O7, were characterized by the SEM technique. The SEM pictures (Fig. 2) of these prepared composites (powdered form) showed almost similar morphology, having a mixture of microplate and agglomerated nanoparticles with non-homogeneous sizes of 15–1 µm of FeP2O7, CoP2O7, and NiP2O7 NPs, which were distributed over the Ni-foam. Further, SEM–EDX mapping was carried out at 10 μm to analyze the composition of the prepared samples. The results indicated that images taken under the NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 samples have corresponding elements, as shown in the right inset figure of Fig. 2 and the respective EDX of the as-prepared samples were illustrated in Fig. S1. Moreover, to gain a further understanding on the microstructure of the as prepared materials, the SEM of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 grown on Ni-foam were taken at different magnifications as well as accounted elemental mapping and EDX analysis for the same in Figs. S2, S3, and S4, respectively. After observing SEM taken before testing reveal the similar microplate-like structure for all the three prepared samples.

Fig. 2.

SEM images of powdered a, b NiP2O7, d, e CoP2O7, and g, h FeP2O7. Elemental mapping at 10 μm of c P, O, and Ni for NiP2O7, f P, O, and Co for CoP2O7, and i P, O, and Fe for FeP2O7

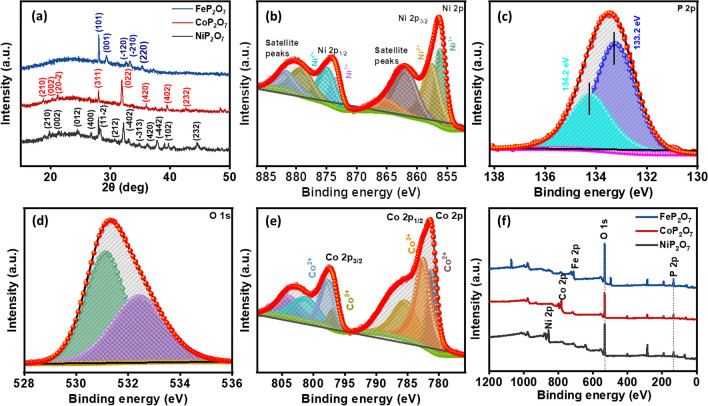

Further, to characterize the sample purity, crystallinity, and crystal structure of the prepared NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 samples, XRD spectra were recorded. The XRD pattern (Fig. 3a) of the prepared catalytic samples showed that NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 samples were perfectly matched with JCPDS#74-1604 [36–39], JCPDS#34-0378 [40–44], and JCPDS#72-1516 [45–48], respectively, confirming their precise structure, as shown in the theoretical section. Subsequently, X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy was employed to investigate the elemental chemical states and results reveal the main elements such as Ni, Co, Fe, P, and O in NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7. Furthermore, the high-resolution XPS of Ni 2p, P 2p, and O 1s of NiP2O7 are displayed in Fig. 3b–d, respectively. In Fig. 3b, the two peaks are obtained after Gaussian fitting of the Ni 2p spectrum located at 875.4 and 857.5 eV corresponding to Ni 2p1/2 and Ni 2p3/2, respectively. Moreover, the satellite peaks at 880.5 and 862.1 eV are attributed to Ni (II) [49]. In addition, the peaks located at 133.2 and 134.2 eV in Fig. 3c, correspond to the significant P 2p3/2 designated to P (V), and P 2p1/2, respectively, and ΔE between the two characteristic peaks is 1 eV. The P 2p spectrum further confirmed the presence of (P2O7)4− at binding energy 133.2 eV. The wider O 1s spectrum in Fig. 3d was deconvoluted into two Gaussian distributions corresponding to two prominent species, chemisorbed hydroxyl (OH) at 533 eV and lattice oxygen at 531.8 eV. Figure 3e shows the high-resolution XPS spectrum of Co, and Figs. S5 and S6 delineate P and O XPS spectra for CoP2O7, respectively. The Co 2p compromised of the Co 2p3/2 and Co 2p1/2 peaks located at 781.5 and 797.5 eV, furthermore the two shake-up satellite peaks located at 786.1 and 802.7 eV, clearly confirms the presence of Co (II) in the obtained material [50]. The peaks designated at specific binding energy correspond to the characteristic P 2p3/2 peaks of P (V) [50]. The peaks in Fig. S6 illustrate the main peaks of O 1s, confirming the presence of O (II). Simultaneously, the high-resolution XPS spectra of Fe 2p, P 2p, and O 1s in Figs. S7–S9 for FeP2O7 were obtained, respectively. The XPS spectra of Fe 2p contain Fe (III) at 711.4 eV, and Fe (II) at 709.7 and 714.2 eV. Thus, the ratio between Fe (III) and Fe (II) components in the XPS is approximately close to 1:2 [51]. Moreover, the XPS P 2p and O 1s consistently suggest a partial negative charge of pyrophosphate ion and due to electron transfer from Fe and P2O7 ions [51, 52]. Further, the survey spectrum evident the presence of Ni, Co, Fe, P, and O in the as-synthesized samples, displayed in Fig. 3f, which comprehensively suggests the formation of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7, combining the results from XRD, further confirmed the formation of the samples with XPS observations.

Fig. 3.

a XRD spectra of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7, High-resolution XPS spectra of the NiP2O7, b Ni 2p, c P 2p, d O 1s, e Co 2p XPS spectra of CoP2O7, and f XPS survey spectra of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7

Electrochemical performance

Hydrogen evolution reaction

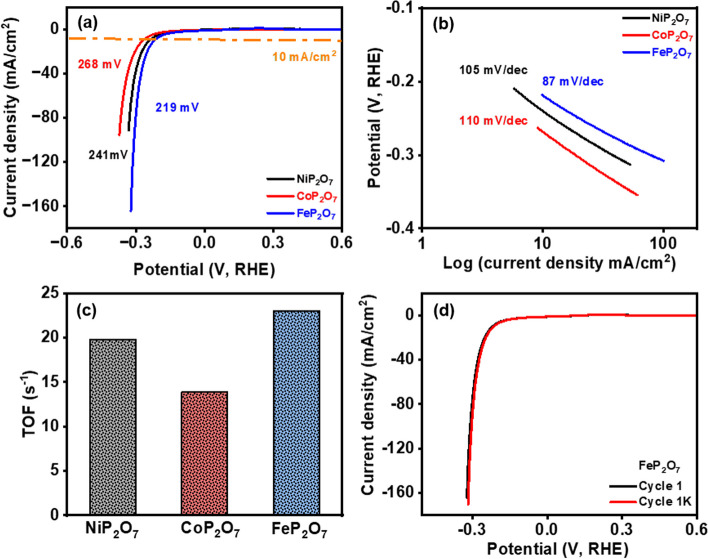

Electrocatalytic HER activity of the prepared NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 samples was assessed in 1 M KOH electrolyte using the LSV technique. Figure 4a shows the typical HER polarization curves for FeP2O7, CoP2O7, and NiP2O7 samples, demonstrating 219 mV, 268 mV, and 241 mV, respectively, at 10 mA/cm2 current density. FeP2O7 exhibited superior HER activity as compared to CoP2O7 and NiP2O7 samples (Fig. S10). Further, to observe the HER kinetics, the Tafel plots for these samples were drawn against their respective LSV data. Figure 4b confirms that the rate-determining step (RDS) for these samples followed the Volmer-Heyrovsky reaction route (H2O + e− → Hads + OH−). From Fig. 4b, it is clear that the FeP2O7 sample showed the lowest Tafel slop value of 87 mV/dec, as compared to CoP2O7 (110 mV/dec), and NiP2O7 (105 mV/dec) samples, suggesting its fast HER kinetics as well as remarkable HER performance. Further, to support the RDS, the TOF values for these catalytic samples were calculated (Fig. 4c), and the results suggested the acquisition of a TOF value of 23.02 s−1 by FeP2O7, which is much higher compared to CoP2O7 and NiP2O7 samples. Therefore, the low overpotential of the FeP2O7 sample corresponds to a higher TOF value, indicating its outstanding HER performance along with efficient rate transfer as compared to CoP2O7 and NiP2O7 samples. Further, to check the practical applicability of the FeP2O7 sample, a durability test was also performed using linear sweep voltammetry. The HER LSV curve for the FeP2O7 sample after 1000 CV cycles displayed negligible fluctuation in its onset potential as well as current density as compared to the first CV cycle, demonstrating its significant durability during the HER process (Fig. 4d). Similar observation was found for NiP2O7 and CoP2O7 (Figs. S11, S12).

Fig. 4.

a Overpotential at 10 mA/cm2 for NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7, b Tafel slopes, c TOF at 100 mV of HER performance for all nanomaterial electrodes, and d LSV curves after and before 1000 cycles of cyclic voltammetry for FeP2O7 sample. All the LSV curves were recorded at 2 mV/s scan rate in 1 M KOH electrolyte

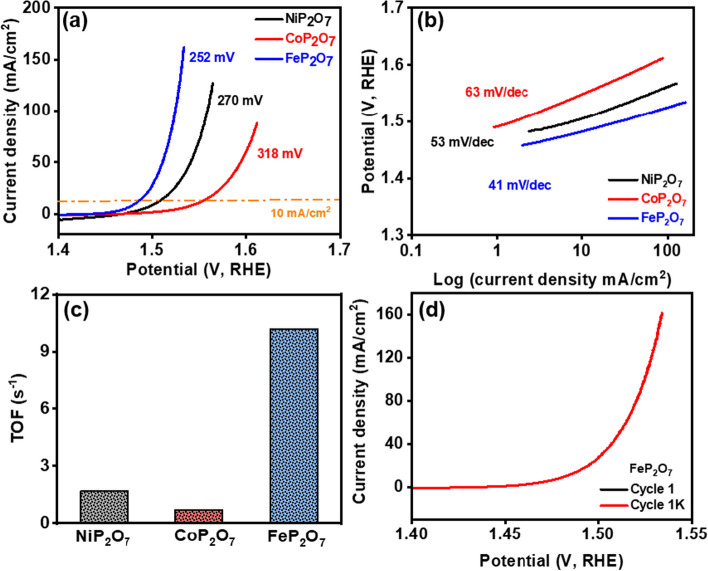

Further, the prepared samples were evaluated for their OER performance using the LSV technique in 1 M KOH media. The iR corrected LSV plots (Fig. 5a) reveal that to attain the 10 mA/cm2 current density, FeP2O7 displayed a 252 mV onset overpotential, which is significantly lower than CoP2O7 (318 mV) and NiP2O7 (270 mV) samples (Fig. S13). In addition, to derive the value of Tafel slopes (Fig. 5b), the Butler–Volmer equation was utilized. A low Tafel value (41 mV/dec) for FeP2O7 is an indication of improved, faster OER kinetics than CoP2O7 and NiP2O7 samples. The TOF value for these samples was also calculated to analyze their intrinsic kinetic behaviour [53]. The TOF value for FeP2O7, CoP2O7, and NiP2O7 samples was found to be 10.17, 0.69, and 1.71 s−1, respectively, indicating the facile OER with the FeP2O7 sample (Fig. 5c). In addition, the OER LSV curve for the FeP2O7 sample recorded before and after 1000 CV cycles displayed negligible fluctuation in its onset potential as well as current density, demonstrating its significant durability during the OER process (Fig. 5d). Similar observation was found for NiP2O7 and CoP2O7 (Figs. S14, S15).

Fig. 5.

a Overpotential at 10 mA/cm2 for NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7. All the LSV curves were recorded at 2 mV/s scan rate in 1 M KOH electrolyte. b Tafel slopes, c TOF at 350 mV of HER performance for all nanomaterial electrodes, and d LSV curves after and before 1000 cycles of cyclic voltammetry for FeP2O7 sample

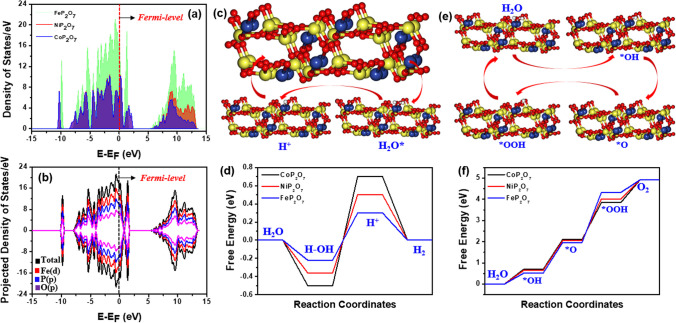

Further, to confirm the catalytic OER and HER mechanisms for the prepared NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 samples and to find the reasons for the improved catalytic performance of FeP2O7 sample as compared to CoP2O7, and NiP2O7 samples, theoretical calculations was performed using DFT. First, of all, we optimized the constructed slabs for these catalytic models, as shown in Fig. 6a. The optimized energy indicated the higher stability of Fe-atom with pyrophosphate. After that, we calculated the density of states for these samples (Fig. 6b), and found the higher high density of state (DOS) and its distribution over the fermi level for the FeP2O7 sample, as compared to CoP2O7, and NiP2O7 samples. These results suggested that the pyrophosphate framework significantly improved the electronic properties of Fe-atom as compared to Co and Ni atoms, benefiting to catalytic performance of the FeP2O7 sample towards HER and OER, as supported by experimental investigations. Further, to confirm the HER mechanism on the prepared samples, the transition metal atom was considered as the active site (*). For HER, H2O adsorption (H2O* state), H-adsorption (H* state), and H2 disposal (Ni-1/2H2 state) on the active site were optimized (Fig. 6c). The computed corresponding free energy curves for these samples clearly indicated the less energy barrier for HER (the values for activity descriptors, ΔGH2O* and ΔGH*, were very close to zero) on the FeP2O7 sample, which might be due to its improved electronic properties, suggesting its efficient HER activity as compared to CoP2O7, and NiP2O7 samples (Fig. 6d). In a similar way, all the intermediates of OER were optimized on the corresponding transition metal site of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 samples (Fig. 6e). The transformation of *O into *OOH can be considered as the potential determining step. Moreover, the free energy diagram suggested that the OER process followed the lower energy barrier with the FeP2O7 sample as compared to CoP2O7, and NiP2O7 samples, indicating its superior OER performance (Fig. 6f).

Fig. 6.

a Density of states (DOS) of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 samples, and b Projected Density of states (PDOS) of FeP2O7 sample. c HER mechanism, d HER Free energy diagram, e OER mechanism, and f OER Free energy diagram, for FeP2O7 sample

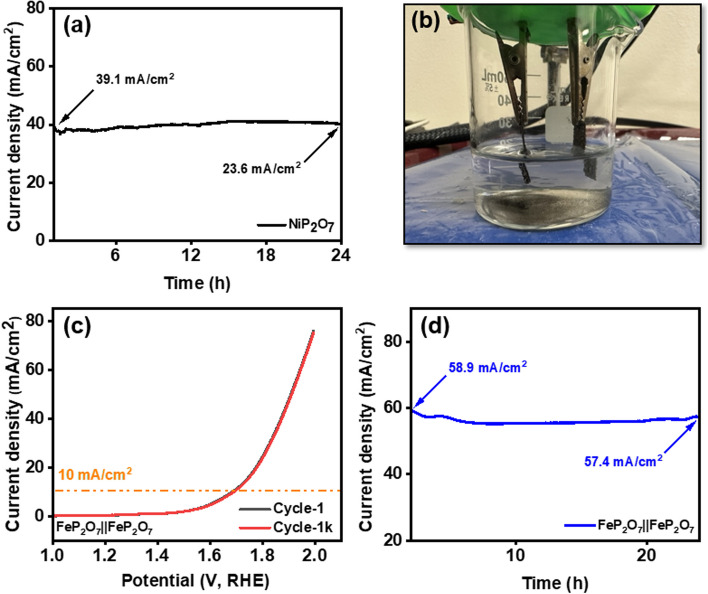

Further, the ECSA was calculated (using the equation; , where Cs = 0.04 mF/cm2 in 1 M KOH [35] to correlate the improved catalytic performance of FeP2O7 sample. It is a thorough comprehension of the mechanism behind the nature of electrocatalysts by developing CV in the region that does not include oxidation or reduction [54]. In order to conduct an analysis of the ECSA, the current densities and related scan rates were plotted, as displayed in Fig. 7a. Also, the value of ECSA is proportional to the value of the electrochemical double-layer capacitance (Cdl). Therefore, the higher the value of Cdl, the greater the ECSA (Fig. 7b), and the more effective the catalytic activity. The Cdl values for the NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 samples are 80, 12, and 85 mV, respectively. FeP2O7 samples have an ECSA of 2125 cm2, which is remarkably higher than CoP2O7 and NiP2O7 samples, indicating more exposure of their active sites towards the catalytic reactions and thereby improving their catalytic performance in OER and HER. In that sense, the roughness factor was calculated to observe the material performance toward producing gas bubbles efficacy as shown in Fig. 7c. Thus, FeP2O7 delineates the highest roughness factor than other samples, indicating the highest ECSA value corresponds to the greater number of active sites for catalytic reaction to produce more gas bubbles supported by the roughness factor. Furthermore, to study the motion of the ions under the electrochemical atmosphere we carried out an electrochemical impedance spectroscopy test to analyze the charge transfer resistance (Rct). Thus, the Nyquist plot of all the samples was plotted in Fig. 7d, Figs. S16 and S17 of FeP2O7, NiP2O7, and CoP2O7, respectively at different potentials of 0.45, 0.5, 0.55, and 0.6 V. Moreover, a fitted Randles circuit is demonstrated in Fig. S18 to exaggerate the attribute of Nyquist plot [55–59] and After analyzing the Nyquist plot at various potential, it was noteworthy found that FeP2O7 showed least charge transfer resistance among all the samples and over different potentials, tabulated in Table S1 in the supplementary information. Furthermore, the longevity stability of the as-prepared samples was examined by using Chronoamperometry testing over 24 h. Figure 8a and Fig. S19a, b displayed a chronoamperometry curve of NiP2O7, and CoP2O7, and FeP2O7, respectively, at 0.65 V potential. The current density drop was fluctuated from 39.1, 47.2, and 114.6 to 23.6, 39.1, and 109.2 mA/cm2 of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7, respectively without any extreme deterioration. It was found that FeP2O7 has a lowest current density drop of about 5.4 mA/cm2 than other materials. However, a variation was caused after 12 h due to release of bubble during water-splitting.

Fig. 7.

a Double layer capacitance of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 samples, b Electrochemical surface area. c Roughness factor, d Nyquist plot of FeP2O7 sample obtained from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

Fig. 8.

a Chronoamperometry curve of NiP2O7, b working of the electrolyzer FeP2O7||FeP2O7, c LSV curve for electrolyzer and polarization stability over 1000 cycles, and d chronoamperometry test for electrolyzer over 24 h

Since the FeP2O7 sample showed excellent bifunctional OER and HER performance, an electrocatalytic water-splitting device was built with the FeP2O7 sample serving as both anode and cathode (Fig. 8b) to test its suitability for practical application in a water electrolyzer. The results show that a sample of FeP2O7 can faithfully adhere to either a 2- or 4-electron process over an extended period of time. The FeP2O7||FeP2O7 on NF showed a low cell potential of just 1.69 V at a current density of 10 mA/cm2 (Fig. 8c), while still creating a huge bubble with a high endurance, as seen by the overlap between the 1st and 1000th cycles of polarization curves (Fig. 8c). Then, long term durability test was performed for 24 h (Fig. 8d) and it was observed that the electrolyzer attained 58.9 mA/cm2 of current density and after 24 h it goes down to 57.4 mA/cm2, indicating highly stable device material for splitting water into H2 and O2. In order to analyze the durability of the FeP2O7 material electrode towards overall water-splitting process, the XRD and SEM images were taken after overall water-splitting stability testing as enumerated in Fig. S20, indicating no structural changes depicted from XRD and no significant change in the morphology was observed through SEM. Due to its robust nature, it can be summarized that there is no obvious chemical changes after overall water-splitting and can be a best candidate towards HER and OER activity.

Supercapacitor study

After microscopic and phase investigations of the materials, the detailed performance of the prepared metal-based pyrophosphate electrodes toward the electrochemical supercapacitor using cyclic voltammograms (CV), galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and stability. Polyphosphates possess excellent chemical stability, indicating better for the long-life challenge of cycling ability. On the other hand, the electrical harvesting, kinetics of charges, and holding capacity over a long time have been challenging problems for pyrophosphate materials. Herein, we have developed the NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 grown on Ni-foam to increase the overall conductivity of the electrode. Moreover, the synthesized sample was treated at an optimum temperature during hydrothermal which helped to grow metal-pyrophosphate without shrinking of material and indicated a strong bond between the material and the substrates, leading to highly enhanced stability in electrochemical reactions. For instance, Wang et al. [60] designed marigold flower-like Mn2P2O7 material and further applied it to a Li-ion battery. However, the obtained material was irreversible at first due to charges consumed to reduce Mn2+ ions to the metallic state, and owing to the formation of electrolyte interphase.

Later on, Senthilkumar et al. [61] fabricated a highly porous carbon-based Ni2P2O7 electrode for supercapacitor application. To promote high conductivity and stability, electrode material possesses a high-purity phase, morphology, sufficient working potential, and reversibility. In those terms, they successfully acquired grain-like nanoparticles which resembled the monoclinic phase of Ni2P2O7 which further enhanced the electrochemical process. Following to that, Hou et al. [62] designed promising 1D Co2P2O7 nanorods without any templates and high-temperature calcination as a pseudocapacitive material for energy storage. The obtained material contains CoO6 coordination octahedron phase with P2O7 groups as an electroactive component for electrochemical activity. In addition, its magnetic and microwave absorption properties also fascinated that material for highly stable and reversible supercapacitor devices. Considering all those parameters, the developed NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 was projected towards preliminary CV testing in 3 M KOH electrolyte at various scan rate from 2 to 300 mV/s in a potential window of 0–0.6 V and the outcomes are illustrated in Fig. 9a–c. CV plot demonstrated pseudocapacitive behavior of the materials and one oxidation and reduction peak appeared in NiP2O7 and FeP2O7 at lower scan rate unless CoP2O7, having two oxidation peaks where first peak around 0.3–0.4 V can be ascribed to the oxidation of Co to Co2+ and peak about 0.45–0.55 occurred due to the Co2+ to Co3+; all the samples showed stable redox profile the profound reversibility due to symmetric nature of faradic reaction. Therefore, the proposed redox mechanism for NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 with basic electrolyte is described in the Eq. (2–4), respectively.

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

Fig. 9.

a–c CV voltammogram for the NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7, at different scan rates ranging from 2 to 300 mV/s, respectively, Trasatti plot of d 1/C versus V1/2 of the NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7, and e C versus v−1/2 of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7, f percentage of capacitance contribution evaluated for the electrodes based on trasatti analysis

The electrode material delineated quasi-reversible reaction which is because of multiple oxidation states of the Ni, Co and Fe, here Ni2+/Co2+/Fe2+ transformed to the Ni3+/Co3+/Fe3+ during redox process. From the reaction Eq. (2–4), inferred that the pair of redox reaction can be observed at a specified potential range, indicating reversible reaction. Analogous to the work done by Wang et al. and group, where they acknowledged that due to lower Pauling electronegativity of P (2.19) enables much higher conductivity. Therefore, the electronegativity difference of P2O7 anion facilitates Ni, Co and Fe and without any further distortion of the CV plots, resembling best reversibility, enhanced mass transportation, capacitive property and rate of charge transfer. Furthermore, the observed distinctive peaks at lower rate corresponds to the pseudocapacitive performance. However, while increasing the scan rate the anodic peak shifted towards right and cathodic peak to the lower potential due to limited interaction of OH− ions. Thereby, we employed a Trasatti method in order to identify the charge stored by the material of the electrodes, either a pseudocapacitive which refers to reversible redox phenomenon, showing the intercalation and electro absorption of the ions or electrochemical double layer capacitance (EDLC) formed at the electrode/electrolyte interface. The Eq. (5–7) are involved to study the mechanism behind the CV curves.

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

where C signifies areal capacitance, CT is total capacitance, CEDLC symbolizes electrical double layer capacitance, and CPS infers pseudo capacitance contribution. A plot of 1/C in function to v1/2 as illustrated in Fig. 9d and a plot of C in function to v−1/2 as shown in Fig. 9e has been analyzed to deduce the EDLC and pseudocapacitance contribution of the NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 electrodes. The overall CEDLC and CPS contribution was illustrated in Fig. 9f based on Trasatti method, indicating NiP2O7 offered high pseudocapacitive behavior of 98% with a least EDLC influence of 2%. However, CoP2O7 and FeP2O7 showed pseudo mechanism by 96% and 95% and EDLC of 4% and 5%, respectively.

Overall, the NiP2O7 represented pseudocapacitive dominated material. Furthermore, to corroborate the kinetic mechanism of the as synthesized materials in terms of diffusion and capacitive nature by indepth observation of CV curves at plethora of scan rates from 2 to 100 mV/s. Hence, Power law was adopted for further calculations which is described in Eqs. (8–9).

| 8 |

| 9 |

where i is the sum of diffusion controlled process (idiff) and surface capacitance controlled process (icap), v represents scan rate, a and b are adjustable parameters where predominant charge storage mechanism was ascertained using b-values, as shown in Fig. S21 which depicts that all the samples completely reliance on ion diffusion. In order to further investigate the contribution of both the mechanism, the total capacity can be quantitively divided into two parts; k1v stands for capacitive effect and k2v1/2 for diffusion controlled effects asaccording to Eq. (10).

| 10 |

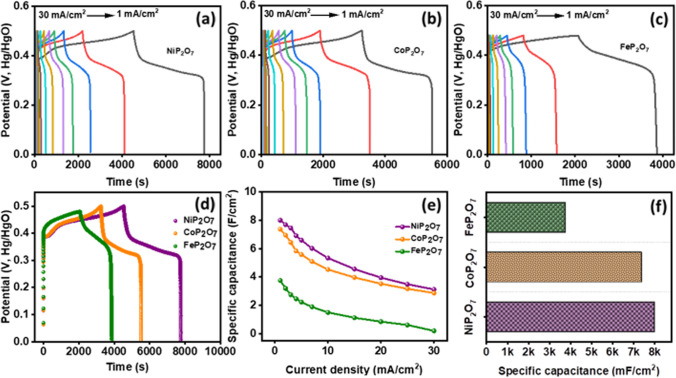

The k1v and k2v1/2 contributions is illustrated for NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 from 2 to 100 mV/s of scan rate in Figs. S22–S24. At low scan rate of 10 mV/s the k1v and k2v1/2 contributions were 5, 11, and 26% and 95, 89, and 74% for NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7, respectively, whereas, at 100 mV/s the contributions tuned to 13, 28, and 52% and 87, 72, and 48% for NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7, respectively. On the contrary of both the mechanisms, the diffusion dominated over capacitive nature in NiP2O7 with least involvement of surface capacitance. Therefore, it reflects that the NiP2O7 possess high rate of ingression of anions deep inside the nanomaterial than regression of the ions. Thus it takes a longer time to completely discharge of ions out of the material to the electrolyte. It is clearly visible that the diffusion was responsible to influence the charge barring property of the material. Furthermore, the charge holding ability of the electrodes were tested under the norms of galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) method and was performed at a different current densities of 1–30 mA/cm2 ran at a potential window of 0.0–0.5 V in a 3 M KOH. Discharge time is the indespensable parameter for the electrochemical performcance for supercapacitor and greater time indicates higher specific capacitance. The specific capacitance (Cs) of the electrodes was derived by using the discharge profile of the GCD as shown in Fig. 10a–c, using Eq. (11) where i is current, Δt is discharge time drew from GCD plots, cm2 is the area of the electrodes, and Δv is the potential window. Herein, the GCD curve is disintegrated into three pillars; fast potential drop, plateau regime and sharp decay. The pioneer decay of potenial is due to internal resistance, intermediate regime of GCD dedicated to plateau due to faradic redox reaction where, NiP2O7 displayed a plateau region but FeP2O7 showed slant nature during discharge, indicating amorphosity of the material (surface capacitance). The GCD plot at higher current densities, such as 15, 20, 25 and 30 mA/cm2 showed a gradual decrease in the discharge time as a consequence of increased voltage drop and insufficient active electrode material took part in redox reactions at higher current densities. The comparitive plot of GCD for NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 at a specific current density of 1 mA/cm2 was graphed in Fig. 10d to enumerates the discharge time taken and behavior of the curve. At last in the discharge process, the sudden drop of potenial was recorded which points the formation of double layer on the surface of the electrode.

| 11 |

Fig. 10.

a–c Galvanostatic charging-discharging of the NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 at different current densities ranging 30–1 mA/cm2, respectively, d Charge–discharge plot of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 at 1 mA/cm2, e Specific capacitance values at different current densities, and f Bar plot comparing specific capacitance of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 at 1 mA/cm2

The calculated specific capacitance from the discharge curves is shown in Fig. 10e in the function of current densities. It was evident that the NiP2O7 outcasted better charge holding property with a maximum specific capacitance than other two samples over different range of current density. In Fig. 10f bar plot shows the comparison of specific capacitance at 1 mA/cm2, where greatest discharge time corresponds to NiP2O7 acquired highest specific capacitance of 7986 mF/cm2 (7.986 F/cm2) than the CoP2O7 (7363 mF/cm2) and FeP2O7 (3745 mF/cm2). Very astounding values of NiP2O7 is because of the agglomerated crystalline structured nanoparticles on the Ni-foam which facilitated more grain boundaries and higher surface area, further improving a more significant number of active sites for OH− ions. The obtained values for specific capacitance of the three novel electrode materials are better than the already reported work in the past. For instance, nanosheets of Co3O4/CC (400 mF/cm2 @ 4 mA/cm2) [63], MnO@C composite (720 mF/cm2 @ 4 mA/cm2) [63], nanoneedle arrays of NiCo2O4 (0.99 F/cm2 @ 5.56 mA/cm2), [64] Na-doped Ni2P2O7//AC (22 mF/cm2 at 1 mA/cm2) [64], Ni2P2O7/Co2P2O7 nanograss array (2074 F/g @ 5 A/g) [37], Ni3(PO4)2/RGO/Co3(PO4)2 composite (1137.2 F/g at 0.5 A/g) [65], MnFe2O4/graphene/polyaniline (241 F/g @ 0.5 mA/cm2) [66], C3N4-1/Ni2P2O7 (4.4 F/cm2 @ 1 mA/cm2) [67], Li2Co2(MoO4)3 (1.03 F/cm2 @ 1 mA/cm2) [68], and Co0.5Ni0.5DHs/NiCo2O4/CFP (2.3 F/cm2 @ 2 mA/cm2) [69]. In that sense, the agglomerated spherical nanoparticles of the NiP2O7 as discussed in SEM investigation provided larger surface and volume ratio for ease in ions transportation in bulk.

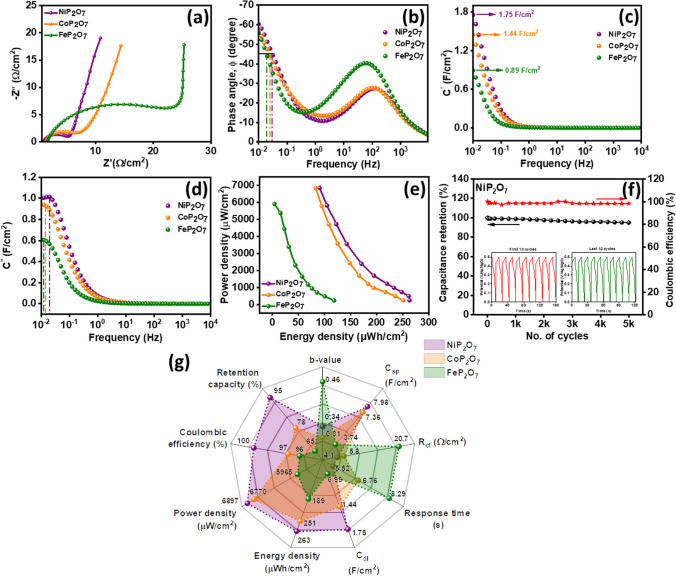

To inculcate the further comprehensive understanding on the charge transfer route and electron transport during the electrochemical process. Therefore, the electrochemical impedance spectrum were measured at room temperature over a frequency range of 0.01–10 k Hz in a 10 mV AC amplitude under open circuit conditions. Figure 11a shows the Nyquist plot derived from the EIS data, where the arc in the high frequency region reflects the reaction occuring at the electrode surface, corresponding to electron transfer and controls the kinetics of the electrode interface. Hence charge transfer resistance can be calculated by measuring the radii of the arc; directly proportional to eachother [57, 58]. The charge transfer resistance of the NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 is 4.05, 5.84, and 20.77 Ω/cm2. The associated Randles circuit [58] for the Nyquist plot of the as synthesized material was demonstrated in Fig. S25. On the basis of EIS observation the NiP2O7 is a better electrochemical active material and a defined slope at a lower frequency region also manifest the excellent ingression of ions in the electrode material, proposing more efficient charge transport thus, pointing good capacitive behavior.

Fig. 11.

a EIS plot of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7, b Bode phase angle for NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 at 45°, c Real capacitance in function to frequency, d Imaginary capacitance in function to frequency, e Power density vs energy density of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7, and f Stability plot of capacitance retention and coulombic efficiency for NiP2O7, g Radar plot comparing nine figures of merit: b-value, specific capacitance (Csp), charge transfer resistance (Rct), response time, double layer capacitance (Cdl), energy density, power density, coulombic efficiency, and capacitance retention

Apart from this, Bode phase angle plot (Fig. 11b) was taken into consideration, which directs the capacitive and inductive nature of the material. If phase angle is closer to − 90°, the material obeys capacitive behavior and behave as an ideal capacitor. The phase angle lesser than − 90° at lower frequency represents pseudocapacitive nature [55]. Herein, all the synthesized material lie between − 50° to − 60°, confirming their pseudocapacitive trait. Moreover, the charge holding parameter and frequency correspondance to − 45° phase angle is defined as figure of merit for supercapacitor materials and response time was calculated and it was found that the NiP2O7 acquired the least response time of 5.521 s to transfer charges. However, the response time (Eq. 12) for CoP2O7 and FeP2O7 are 6.765 and 8.298 s, respectively. Hence, the less response time and charge transfer resistance of the NiP2O7 confirmed the improved kinetics.

The frequency dependent capacitance (C) is a addition of real () and imaginary capacitance (C″) (Eq. 13) [70]. Under that line, the double layer capacitance (Cdl) was analyzed by plotting frequency dependent real capcitance () curve as shown in Fig. 11c, measured by using Eq. 14, where, Z″ and |Z| signifies the imaginary part (resistance), and modulus of total impedance, respectively and recorded that the capacitance value increases from zero to near saturation [71]. The Cdl value for NiP2O7 (1.75 F/cm2) is higher than CoP2O7, and FeP2O7, directing highest power density. Moreover, Fig. 11d elucidates imaginary capacitance to frequency (Eq. 15), where Z′ is the real part (resistance), which reassist the response time of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 is 7.722, 11.312, and 13.227 s and matches the trend of response time calculated by using phase angle plot, indicating NiP2O7 offered better energy density. Additionally, the relationship between power and energy densities were analyzed using the Ragone plot in Fig. 11e. With the niches in power density, the energy density depreciates. The maximum power density recorded for NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 is 6.897, 6.870, and 5.965 mW/cm2 and energy density for the three materials are 0.263, 0.251, and 0.118 mWh/cm2, respectively. Thus NiP2O7 electrode commanding on power and energy density over other electrodes can be used for battery-supercapacitor hybrid device [72].

| 12 |

| 13 |

| 14 |

| 15 |

Stability is considered as a crucial parameter for real life application. Thereby, the cycling stability was carried out for 5000 charge–discharge cycles, Fig. 11f, Figs. S26 and S27 shows the multiple charge–discharge cycles, capacitance retention and coulombic efficiency of the NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7, respectively, where NiP2O7 holds 97% of capacitance retention and 100% coulombic efficiency.

The Radar plot, as displays in Fig. 11g, compares 9 figure of merit, that is Csp, b-value, Rct, response time calculated using phase angle plot, Cdl, energy desnity, power density, capacitance retention, and coulombic efficiency of NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7. The salient features depicted from the Radar plot and observations as follows; (1) The XRD reveals the high crystallinity of NiP2O7 than other samples, (2) EDX showed more percentage composition of Ni in NiP2O7 than other transition metals in CoP2O7 and FeP2O7, exhibiting more conversion of oxidation states in NiP2O7 and assist passivity to the ions feassibly, (3) thus numerous active sites are provided by NiP2O7 and better diffusion of ions as an effect of less Rct and response time during electrochemical reaction, (4) highest value of Cdl, Csp, power density, energy density and stability cordially contributing to reason that NiP2O7 showed improved and best candidate for supercapacitor application among other pyrophosphates.

Conclusion

In summary, three composites, NiP2O7, CoP2O7, and FeP2O7 nanoparticles grown on Ni-foam, were prepared using hydrothermal strategy, and characterized via multiple analytical techniques. The prepared composites were tested for electrochemical water splitting and supercapacitors. The results indicated the superior performance of FeP2O7 composite towards OER and HER, displaying the lowest overpotential of 220 and 241 mV at 10 mA/cm2, respectively. The DFT calculations revealed that FeP2O7 had a higher distribution of DOS over the fermi level than CoP2O7 and NiP2O7, which improved its electronic characteristics and contributed to its superior electrochemical performances towards OER, and HER. Moreover, NiP2O7, with its higher percentage composition of Ni on the Ni-foam, which permits more Ni to convert into its oxidation states and come back to its original oxidation state during supercapacitor testing, was found to have the highest specific capacitance and remarkable cycle stability due to its high crystallinity. This work can serve as an approach towards understanding of electronic alterations in transition metals via pyrophosphate species to design efficient materials for developing energy conversion and storage.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST award number 70NANB20D146) and the U.S. Economic Development Administration (US-EDA award number 05-79-06038) for providing research infrastructure funding. RKG acknowledges support from the National Aeronautics & Space Administration (NASA) (Award number 80NSSC20M0109, subaward number R52545-21-01235) and Mishra acknowledges financial support from the University of Memphis.

Author contributions

RS wrote the original draft. HC, FMDS, SRM, and FP provided the comments and helped in editing. AK & RKG provided the comments and supervised the project throughout.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Anuj Kumar, Email: anuj.kumar@gla.ac.in.

Ram K. Gupta, Email: ramguptamsu@gmail.com

References

- 1.Khalafallah D, Xiaoyu L, Zhi M, Hong Z. 3D hierarchical NiCo layered double hydroxide nanosheet arrays decorated with noble metal nanoparticles for enhanced urea electrocatalysis. ChemElectroChem. 2020;7:163–174. doi: 10.1002/celc.201901423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khalafallah D, Farghaly AA, Ouyang C, Huang W, Hong Z. Atomically dispersed Pt single sites and nanoengineered structural defects enable a high electrocatalytic activity and durability for hydrogen evolution reaction and overall urea electrolysis. J Power Sources. 2023;558:232563. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2022.232563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed FBM, Khalafallah D, Zhi M, Hong Z. Porous nanoframes of sulfurized NiAl layered double hydroxides and ternary bismuth cerium sulfide for supercapacitor electrodes. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater. 2022;5:2500–2514. doi: 10.1007/s42114-022-00496-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khalafallah D, Li X, Zhi M, Hong Z. Nanostructuring nickel–zinc–boron/graphitic carbon nitride as the positive electrode and BiVO4-immobilized nitrogen-doped defective carbon as the negative electrode for asymmetric capacitors. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2021;4:14258–14273. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.1c03870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khalafallah D, Zhi M, Hong Z. Bi-Fe chalcogenides anchored carbon matrix and structured core–shell Bi-Fe-P@Ni-P nanoarchitectures with appealing performances for supercapacitors. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2022;606:1352–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2021.08.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khalafallah D, Zhi M, Hong Z. Rational engineering of hierarchical mesoporous CuxFeySe battery-type electrodes for asymmetric hybrid supercapacitors. Ceram Int. 2021;47:29081–29090. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.07.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duan F, Huang Y, Han T, Jia B, Zhou X, Zhou Y, Yang Y, Wei X, Ke G, He H. Enhanced oxygen evolution reaction performance on NiSx@Co3O4/nickel foam electrocatalysts with their photothermal property. Inorg Chem. 2023;62:12119–12129. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.3c01690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song F, Bai L, Moysiadou A, Lee S, Hu C, Liardet L, Hu X. Transition metal oxides as electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction in alkaline solutions: an application-inspired renaissance. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:7748–7759. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b04546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang J, Salunkhe RR, Liu J, Torad NL, Imura M, Furukawa S, Yamauchi Y. Thermal conversion of core-shell metal-organic frameworks: a new method for selectively functionalized nanoporous hybrid carbon. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:1572–1580. doi: 10.1021/ja511539a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Z-S, Wang D-W, Ren W, Zhao J, Zhou G, Li F, Cheng H-M. Anchoring hydrous RuO2 on graphene sheets for high-performance electrochemical capacitors. Adv Funct Mater. 2010;20:3595–3602. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201001054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hou Y, Cheng Y, Hobson T, Liu J. Design and synthesis of hierarchical MnO2 nanospheres/carbon nanotubes/conducting polymer ternary composite for high performance electrochemical electrodes. Nano Lett. 2010;10:2727–2733. doi: 10.1021/nl101723g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang Z, Tang C, Gong H. A high energy density asymmetric supercapacitor from nano-architectured Ni(OH)2/carbon nanotube electrodes. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22:1272–1278. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201102796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao L, Xu F, Liang Y-Y, Li H-L. Preparation of the novel nanocomposite Co(OH)2/ultra-stable Y zeolite and its application as a supercapacitor with high energy density. Adv Mater. 2004;16:1853–1857. doi: 10.1002/adma.200400183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang D, Kong L-B, Liu M-C, Luo Y-C, Kang L. An approach to preparing Ni–P with different phases for use as supercapacitor electrode materials. Chem.—A Eur. J. 2015;21:17897–17903. doi: 10.1002/chem.201502269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta A, Allison CA, Ellis ME, Choi J, Davis A, Srivastava R, de Souza FM, Neupane D, Mishra SR, Perez F, Kumar A, Gupta RK, Dawsey T. Cobalt metal–organic framework derived cobalt–nitrogen–carbon material for overall water splitting and supercapacitor. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2023;48:9551–9564. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.11.340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ding H, Xu L, Wen C, Zhou J-J, Li K, Zhang P, Wang L, Wang W, Wang W, Xu X, Ji W, Yang Y, Chen L. Surface and interface engineering of MoNi alloy nanograins bound to Mo-doped NiO nanosheets on 3D graphene foam for high-efficiency water splitting catalysis. Chem Eng J. 2022;440:135847. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2022.135847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao W, Zou Y, Zang Y, Zhao X, Zhou W, Dai Y, Liu H, Wang J-J, Ma Y, Sang Y. Magnetic-field-regulated Ni-Fe-Mo ternary alloy electrocatalysts with enduring spin polarization enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. Chem Eng J. 2023;455:140821. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2022.140821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srivastava R, Bhardwaj S, Kumar A, Singhal R, Scanley J, Broadbridge CC, Gupta RK. Waste Citrus reticulata assisted preparation of cobalt oxide nanoparticles for supercapacitors. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:4119. doi: 10.3390/nano12234119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta A, Allison CA, Kumar A, Srivastava R, Lin W, Sultana J, Mishra SR, Perez F, Gupta RK, Dawsey T. Tuned morphology configuration to augment the electronic structure and durability of iron phosphide for efficient bifunctional electrocatalysis and charge storage. J Energy Storage. 2023;73:108824. doi: 10.1016/j.est.2023.108824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allison CA, Gupta A, Kumar A, Srivastava R, Lin W, Sultana J, Mishra SR, Perez F, Gupta RK, Dawsey T. Phase modification of cobalt-based structures for improvement of catalytic activities and energy storage. Electrochim Acta. 2023;465:143023. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2023.143023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khalafallah D, Miao J, Zhi M, Hong Z. Structuring graphene quantum dots anchored CuO for high-performance hybrid supercapacitors. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2021;122:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jtice.2021.04.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khalafallah D, Huang W, Zhi M, Hong Z. Synergistic tuning of nickel cobalt selenide@nickel telluride core–shell heteroarchitectures for boosting overall urea electrooxidation and electrochemical supercapattery. Energy Environ Mater. 2022; e12528.

- 23.Khalafallah D, Ouyang C, Ehsan MA, Zhi M, Hong Z. Complexing of NixMny sulfides microspheres via a facile solvothermal approach as advanced electrode materials with excellent charge storage performances. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2020;45:6885–6896. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huynh N-D, Choi WM, Hur SH. Exploring the effects of various two-dimensional supporting materials on the water electrolysis of Co-Mo sulfide/oxide heterostructure. Nanomaterials. 2023;13:2463. doi: 10.3390/nano13172463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou S, Li C, Yang G, Bi G, Xu B, Hong Z, Miura K, Hirao K, Qiu J. Self-limited nanocrystallization-mediated activation of semiconductor nanocrystal in an amorphous solid. Adv Funct Mater. 2013;23:5436–5443. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201300969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen J, Xu J, Zhou S, Zhao N, Wong C-P. Amorphous nanostructured FeOOH and Co–Ni double hydroxides for high-performance aqueous asymmetric supercapacitors. Nano Energy. 2016;21:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2015.12.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi S-H, Hwang D, Kim D-Y, Kervella Y, Maldivi P, Jang S-Y, Demadrille R, Kim I-D. Amorphous zinc stannate (Zn2SnO4) nanofibers networks as photoelectrodes for organic dye-sensitized solar cells. Adv Funct Mater. 2013;23:3146–3155. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201203278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang N, Ouyang S, Kako T, Ye J. Synthesis of hierarchical Ag2ZnGeO4 hollow spheres for enhanced photocatalytic property. Chem Commun. 2012;48:9894–9896. doi: 10.1039/c2cc34738e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pang H, Zhang Y-Z, Run Z, Lai W-Y, Huang W. Amorphous nickel pyrophosphate microstructures for high-performance flexible solid-state electrochemical energy storage devices. Nano Energy. 2015;17:339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2015.07.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong Y, Zhu J, Li Q, Zhang S, Song H, Jia D. Carbon materials for high mass-loading supercapacitors: filling the gap between new materials and practical applications. J Mater Chem A. 2020;8:21930–21946. doi: 10.1039/D0TA08265A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang Y, Jiang LW, Liu H, Wang JJ. Electronic structure regulation and polysulfide bonding of Co-doped (Ni, Fe)1+ xS enable highly efficient and stable electrocatalytic overall water splitting. Chem Eng J. 2022;441:136121. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2022.136121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu YZ, Huang Y, Jiang LW, Meng C, Yin ZH, Liu H, Wang JJ. Modulating the electronic structure of CoS2 by Sn doping boosting urea oxidation for efficient alkaline hydrogen production. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2023;642:574–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2023.03.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beeman JW, Bullock J, Wang H, Eichhorn J, Towle C, Javey A, Ager JW. Si photocathode with Ag-supported dendritic Cu catalyst for CO2 reduction. Energy Environ Sci. 2019;12:1068–1077. doi: 10.1039/C8EE03547D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anantharaj S, Ede SR, Karthick K, Sam Sankar S, Sangeetha K, Karthik PE, Kundu S. Precision and correctness in the evaluation of electrocatalytic water splitting: revisiting activity parameters with a critical assessment. Energy Environ Sci. 2018;11:744–771. doi: 10.1039/C7EE03457A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akbar K, Jeon JH, Kim M, Jeong J, Yi Y, Chun S-H. Bifunctional electrodeposited 3D NiCoSe2/nickle foam electrocatalysts for its applications in enhanced oxygen evolution reaction and for hydrazine oxidation. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2018;6:7735–7742. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b00644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coustan L, Le Comte A, Brousse T, Favier F. MnO2 as ink material for the fabrication of supercapacitor electrodes. Electrochim Acta. 2015;152:520–529. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2014.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matheswaran P, Karuppiah P, Chen SM, Thangavelu P. A binder-free Ni2P2O7/Co2P2O7 nanograss array as an efficient cathode for supercapacitors. New J Chem. 2020;44:13131–13140. doi: 10.1039/D0NJ00890G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matheswaran P, Karuppiah P, Chen SM, Thangavelu P, Ganapathi B. Fabrication of g-C3N4 nanomesh-anchored amorphous NiCoP2O7: tuned cycling life and the dynamic behavior of a hybrid capacitor. ACS Omega. 2018;3:18694–18704. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b02635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Surendran S, Sivanantham A, Shanmugam S, Sim U, Selvan RK. Ni2P2O7 microsheets as efficient Bi-functional electrocatalysts for water splitting application. Sustain Energy Fuels. 2019;3:2435–2446. doi: 10.1039/C9SE00265K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou H, Upreti S, Chernova NA, Whittingham MS. Lithium cobalt(II) pyrophosphate, Li1.86CoP2O7, from synchrotron X-ray powder data. Acta Crystallogr Sect E Struct Rep Online. 2011;67:i58–i59. doi: 10.1107/S1600536811038451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim H, Lee S, Park YU, Kim H, Kim J, Jeon S, Kang K. Neutron and X-ray diffraction study of pyrophosphate-based Li2–xMP2O7 (M = Fe, Co) for lithium rechargeable battery electrodes. Chem Mater. 2011;23:3930–3937. doi: 10.1021/cm201305z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J, Liu P, Bu R, Zhang H, Zhang Q, Liu K, Liu Y, Xiao Z, Wang L. In situ fabrication of a rose-shaped Co2P2O7/C nanohybrid via a coordination polymer template for supercapacitor application. New J Chem. 2020;44:12514–12521. doi: 10.1039/D0NJ02414G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang Y, Shi N-E, Zhao S, Xu D, Liu C, Tang Y-J, Dai Z, Lan Y-Q, Han M, Bao J. Coralloid Co2P2O7 nanocrystals encapsulated by thin carbon shells for enhanced electrochemical water oxidation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:22534–22544. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b07209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu Y, Xie T, Zhang S, Zhang N, Wang G, Feng P, Xu H, Lv K. A sandwich structure of cobalt pyrophosphate/nickel phosphite@C: one step synthesis and its good electrocatalytic performance. J Solid State Electrochem. 2022;26:1221–1230. doi: 10.1007/s10008-022-05156-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee GH, Seo SD, Shim HW, Park KS, Kim DW. Synthesis and Li electroactivity of Fe2P2O7 microspheres composed of self-assembled nanorods. Ceram Int. 2012;38:6927–6930. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2012.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xie X, Hu G, Cao Y, Du K, Gan Z, Xu L, Wang Y, Peng Z. Rheological phase synthesis of Fe2P2O7/C composites as the precursor to fabricate high performance LiFePO4/C composites for lithium-ion batteries. Ceram Int. 2019;45:12331–12336. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.03.149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li H, Liu T, He Y, Song J, Meng A, Sun C, Hu M, Wang L, Li G, Zhang Z, Liu Y, Zhao J, Li Z. Interfacial engineering and a low-crystalline strategy for high-performance supercapacitor negative electrodes: Fe2P2O7 nanoplates anchored on N/P Co-doped graphene nanotubes. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14:3363–3373. doi: 10.1021/acsami.1c17356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fe2P2O7-XRD-04.pdf (n.d.).

- 49.Kotta A, Kim E-B, Ameen S, Shin H-S, Seo HK. Communication—ultra-small NiO nanoparticles grown by low-temperature process for electrochemical application. J Electrochem Soc. 2020;167:167517. doi: 10.1149/1945-7111/abcf51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li B, Zhu R, Xue H, Xu Q, Pang H. Ultrathin cobalt pyrophosphate nanosheets with different thicknesses for Zn-air batteries. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;563:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2019.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu D, Wu C, Yan M, Wang J. Correlating the microstructure, growth mechanism and magnetic properties of FeSiAl soft magnetic composites fabricated via HNO3 oxidation. Acta Mater. 2018;146:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2018.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khan MW, Loomba S, Ali R, Mohiuddin M, Alluqmani A, Haque F, Liu Y, Sagar RUR, Zavabeti A, Alkathiri T, Shabbir B, Jian X, Ou JZ, Mahmood A, Mahmood N. Nitrogen-doped oxygenated molybdenum phosphide as an efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution in alkaline media. Front Chem. 2020;8:733. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Janani G, Surendran S, Choi H, An T-Y, Han M-K, Song S-J, Park W, Kim JK, Sim U. Anchoring of Ni12P5 microbricks in nitrogen- and phosphorus-enriched carbon frameworks: engineering bifunctional active sites for efficient water-splitting systems. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2022;10:1182–1194. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c06514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Surendran S, Jesudass SC, Janani G, Kim JY, Lim Y, Park J, Han M-K, Cho IS, Sim U. Sulphur assisted nitrogen-rich CNF for improving electronic interactions in Co-NiO heterostructures toward accelerated overall water splitting. Adv Mater Technol. 2023;8:2200572. doi: 10.1002/admt.202200572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mei BA, Lau J, Lin T, Tolbert SH, Dunn BS, Pilon L. Physical interpretations of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of redox active electrodes for electrical energy storage. J Phys Chem C. 2018;122:24499–24511. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b05241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Macdonald JR, Johnson WB. Fundamentals of impedance spectroscopy. In: Impedance spectroscopy. 2005. p. 1–26.

- 57.Lasia A. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and its applications BT—modern aspects of electrochemistry. Mod Asp Electrochem. 2002;32:143–248. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Magar HS, Hassan RYA, Mulchandani A. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (Eis): principles, construction, and biosensing applications. Sensors. 2021;21:6578. doi: 10.3390/s21196578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laschuk NO, Easton EB, Zenkina OV. Reducing the resistance for the use of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy analysis in materials chemistry. RSC Adv. 2021;11:27925–27936. doi: 10.1039/D1RA03785D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shi C, Zhao Q, Li H, Liao ZM, Yu D. Low cost and flexible mesh-based supercapacitors for promising large-area flexible/wearable energy storage. Nano Energy. 2014;6:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2014.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Senthilkumar B, Khan Z, Park S, Kim K, Ko H, Kim Y. Highly porous graphitic carbon and Ni2P2O7 for a high performance aqueous hybrid supercapacitor. J Mater Chem A. 2015;3:21553–21561. doi: 10.1039/C5TA04737D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hou L, Lian L, Li D, Lin J, Pan G, Zhang L, Zhang X, Zhang Q, Yuan C. Facile synthesis of Co2P2O7 nanorods as a promising pseudocapacitive material towards high-performance electrochemical capacitors. RSC Adv. 2013;3:21558–21562. doi: 10.1039/c3ra41257a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu N, Guo K, Zhang W, Wang X, Zhu MQ. Flexible high-energy asymmetric supercapacitors based on MnO@C composite nanosheet electrodes. J Mater Chem A. 2017;5:804–813. doi: 10.1039/C6TA08330G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paquin F, Rivnay J, Salleo A, Stingelin N, Silva C. Multi-phase semicrystalline microstructures drive exciton dissociation in neat plastic semiconductors. J Mater Chem C. 2015;3:10715–10722. doi: 10.1039/C5TC02043C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao C, Wang S, Zhu Z, Ju P, Zhao C, Qian X. Roe-shaped Ni3(PO4)2/RGO/Co3(PO4)2 (NRC) nanocomposite grown: in situ on Co foam for superior supercapacitors. J Mater Chem A. 2017;5:18594–18602. doi: 10.1039/C7TA04802E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sankar KV, Selvan RK. The ternary MnFe2O4/graphene/polyaniline hybrid composite as negative electrode for supercapacitors. J Power Sources. 2015;275:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.10.183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang N, Chen C, Chen Y, Chen G, Liao C, Liang B, Zhang J, Li A, Yang B, Zheng Z, Liu X, Pan A, Liang S, Ma R. Ni2P2O7 nanoarrays with decorated C3N4 nanosheets as efficient electrode for supercapacitors. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2018;1:2016–2023. doi: 10.1021/acsaem.8b00114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hercule KM, Wei Q, Asare OK, Qu L, Khan AM, Yan M, Du C, Chen W, Mai L. Interconnected nanorods-nanoflakes Li2Co2(MoO4)3 framework structure with enhanced electrochemical properties for supercapacitors. Adv Energy Mater. 2015;5:1–7. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201500060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gao L, Surjadi JU, Cao K, Zhang H, Li P, Xu S, Jiang C, Song J, Sun D, Lu Y. Flexible fiber-shaped supercapacitor based on nickel-cobalt double hydroxide and pen ink electrodes on metallized carbon fiber. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:5409–5418. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b16101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Deng Z, Ho C-K, Li C-YV, Chan K-Y. An impedance study on porous carbon/lithium titanate composites for Li-ion battery. In: ECS meeting abstracts. MA2017-01. 2017. p. 613.

- 71.Rokaya C, Keskinen J, Lupo D. Integration of fully printed and flexible organic electrolyte-based dual cell supercapacitor with energy supply platform for low power electronics. J Energy Storage. 2022;50:104221. doi: 10.1016/j.est.2022.104221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zuo W, Li R, Zhou C, Li Y, Xia J, Liu J. Battery-supercapacitor hybrid devices: recent progress and future prospects. Adv Sci. 2017;4:1600539. doi: 10.1002/advs.201600539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.