Graphical abstract

Keywords: Porcine bone collagen, Ultrasound, Enzymatic hydrolysis, Bioactive peptides, Anti-inflammatory effect

Highlights

-

•

Ultrasound-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis enhanced the peptide content from porcine bone collagen.

-

•

The optimum extraction parameters were investigated to be ultrasound power of 450 W and treatment time of 20 min.

-

•

Porcine bone collagen derived peptides was firstly reported to exert anti-inflammatory activities by suppressing the secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells.

-

•

Anti-inflammatory sequences were screened by PeptideRanker and molecular docking to elucidate its potential inflammatory regulatory pathway.

Abstract

In this study, the effects of ultrasound-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis on the extraction of anti-inflammatory peptides from porcine bone collagen were investigated. The results showed that ultrasound treatment increased the content of α-helix while decreased β-chain and random coil, promoted generation of small molecular peptides. Ultrasound-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis improved the peptide content, enhanced ABTS+ radical scavenging and ferrous ion chelating ability than non-ultrasound group. At the ultrasonic power of 450 W (20 min), peptides possessed significant anti-inflammatory activity, where the releasing of interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) was all suppressed in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced RAW264.7 cells. After the analysis with LC-MS/MS, eight peptides with potential anti-inflammatory activities were selected by the PeptideRanker and molecular docking. In general, the ultrasound-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis was an effective strategy to extract the bioactive peptides from porcine bone, and the inflammatory regulation capacity of bone collagen sourced peptides was firstly demonstrated.

1. Introduction

Bioactive peptides are considered as substances with chain length of 2–20 amino acid residues and a relative molecular mass of less than 6 kDa [1]. Compared with other functional food ingredients, bioactive peptides have specific characteristics such as simple structure, high safety and good stability. Many proteins isolated from animal and plant products have been proven to be good sources of bioactive peptides with various functions on human metabolism and physiological regulation, such as antioxidant, immune promotion, antibacterial, blood pressure lowering, and hormone regulation [2], [3].

Bone is a by-product of pork slaughtering industry, accounting for about 35 % of the live weight of adult pigs, and constituting an excellent protein source of collagen. Additionally, the bone collagen from livestock is considered to be green and equivalent safe as well as an applicable protein resource because it is similar in structure to human collagen without causing rejection responses [4]. The general structure of collagen is the repetition of the “glycine-X-Y” domain, culminating in triple helix structure. The “X” represents proline (Pro), and “Y” represents hydroxyproline (Hyp). Collagen is particularly rich in non-essential amino acids and not so much in essential amino acids which can generate bioactive peptides with specific sequences after hydrolysis. Such peptides have proved to exert a variety of bioactivities with great interest for health. For instance, peptides derived from sturgeon (Acipenser Schrenckii) cartilage collagen could scavenge free radicals and inhibit mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) channels to alleviate inflammatory response [5]. Chicken bone collagen peptides, as a potential functional anti-aging ingredient, can effectively delay skin aging, increase skin antioxidant levels and decrease inflammation [6]. In the in vivo study, the collagen peptides isolated from the skin of Lophius litulon enhanced the activity of antioxidant-related enzymes, activated the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) cell signal and inhibited nod-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) to significantly reduce the levels of cellular inflammatory factors and ameliorate high-fat diet-induced kidney injury in mice [7]. Collagen peptides extracted from pig bones have also shown antioxidant, anti-hypertensive, DPP IV inhibitory and calcium binding activities [8], [9].

Enzymatic hydrolysis is a typical strategy for producing bioactive peptides, but the entire operation steps have the disadvantages of a long time and a relatively low yield of target peptides. In recent years, some emerging technologies have been applied to assist enzymatic hydrolysis, such as microwaves, high-voltage pulsed electric fields and ultrasonic waves [10]. Among them, ultrasound is a green, clean, efficient, safe and easy-to-operate auxiliary production technology. During the treatment of ultrasonic process, tiny bubbles are generated due to the vibration of the liquid, which will burst when reaching the critical size and results in a strong shock wave. With the collapse of the bubbles, the local pressure increases, resulting in a high shear force, and the whole process also has a local high temperature and other phenomena generating “ultrasonic cavitation” effect [11]. Recently, studies have demonstrated the potential of ultrasound-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis technology in improving functional ingredient extraction, which can increase protein conversion and enzymatic hydrolysis rate. Bedin et al., [12] compared the simple alkaline and ultrasonic-assisted alkaline extraction, and reported that ultrasonic- assisted treatment could improve the extraction rate of rice bran protein by increasing the frequency and speed of rice bran protein molecular movement. The antioxidant activity of peptides from soft-shelled turtle collagen in ultrasonic treatment was also improved in relation to the non-ultrasonic group. At the same time, ultrasonic treatment can induce significant physical changes, with a looser, more porous and homogeneous microstructure of collagen [13]. A combination of ultrasonic and thermal pretreatment also increased the rate of enzymatic digestion and exhibited an effective capacity in modifying globular proteins [14]. However, till now, the efficacy of ultrasound combined enzymatic hydrolysis on the production of inflammatory regulating peptides from porcine bone remains unknown.

In the current study, the ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis was used to produce bioactive peptides from porcine bones. Generally, the peptide content, ABTS+ radical scavenging rate, ferrous ion chelating ability, nitric oxide (NO) scavenging activity and albumin denaturation inhibiting activity were used as indicators for the optimization of ultrasound process. In addition, the anti-inflammatory activity of the porcine bone peptides (PBPs) was investigated via the RAW264.7 cell model with the release of NO, interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Finally, the anti-inflammatory peptide sequences were screened by molecular docking to reveal the structure induced functional properties.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials

Porcine bones were purchased from Yurun group (Nanjing, China). The RAW264.7 cells and the dulbecco's modified eagle cell culture medium (DMEM) were purchased from KeyGEN Biotech Co., Ltd (Nanjing, China). NO assay kit was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). CCK-8 kit was purchased from Yifeixue Biotech Inc. (Nanjing, China). ELISA kits (TNF-α, IL-6) were purchased from NeoBioscience (Shenzhen, China). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, USA). Molecular weight calibration protein was purchased from Solarbio Technology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China) and the synthetic peptide was purchased from GenScript Biotech Co., Ltd (Nanjing, China). All other chemicals were analytically pure grade.

2.2. Preparation of peptides

2.2.1. Porcine bone powder preparation

The preparation process of porcine bone was operated referring to the study of Cao et al., [15]. Firstly, the lean meat and fascia on porcine bones were removed thoroughly and then the bones were put in an oven at 40 °C for 24 h with drying. Secondly, the dried bones were pulverized by a small rocking crusher and then sifted to 40 mesh. Subsequently, the bone powder was mixed with NaOH (0.1 M, 1:10, w:v), 10 % n-hexane and 0.25 M EDTA, followed by shaking (4 °C, 200 r/min) for 2 d. Finally, the powder mixture was washed 10 times (5 s each time) with ultrapure water to remove residual reagent, and followed by centrifuging for 10 min (4 °C, 12,000 g) to collect the precipitation. The bone powder was freeze-dried for subsequent use.

2.2.2. Preparation of porcine bone collagen

The method was referring to the operations from Cao et al., [15]. The bone powder was mixed with 0.05 M citric acid solution (1:10, w:v) under stirring for 21 h at 25 °C. Subsequently, the pepsin was supplemented to stir together for 5 h (100 U/g, pH 2.0, 300 r/min). After washing, the bone powder mixture was diluted with ultrapure water in a ratio of 1:5 (w:v) and then boiled at 70 °C for 7 h. Finally, the mix was centrifuged for 10 min (12,000 g) to collect the supernatant for drying (45 °C). The dried porcine bone collagen was stored at −80 °C refrigerator for further experiments.

2.2.3. The producing of peptides by ultrasound-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis

The production method was according to Cao et al., [15] with appropriate modifications. The porcine bone collagen was dissolved in ultrapure water (30 mg/mL) and treated by an ultrasonic cell disruptor (Shanghai Yuming Instrument Co., Ltd., China) to set different ultrasonic power and time for processing. The solution was treated in a water bath (40℃, 10 min) after sonication. The pH was then adjusted to 10.5 with NaOH, and Alkaline 2.4 L (Novozymes Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Denmark) was added for enzymatic hydrolysis (7,200 U/g, 4 h). Afterwards, the solution was incubated in a boiling water bath for 15 min for enzyme inactivation and the pH was adjusted to 7.0 with HCl after the solution was cooled. Finally, the supernatant was obtained by centrifugation (25 °C, 12,000 g, 10 min) and then freeze-dried to prepare porcine bone collagen peptides, and finally stored in −80 °C for subsequent experiments.

2.3. Peptide content

The peptide content of porcine bone peptides (PBPs) was determined according to Fu et al., [16]. Firstly, the o-phthalaldehyde mixed solution was prepared by dissolving 80 mg of o-phthalaldehyde in methanol (2 mL), which was then mixed with sodium tetraborate decahydrate (100 mmol/L, 50 mL), sodium dodecyl sulfate (20 %, 5 mL), β-mercaptoethanol (200 µL) and 42.8 mL of ultrapure water. Secondly, the sample was dissolved in ultrapure water to prepare a crude peptide solution (1 mg/mL). A mixed solution of o-phthalaldehyde (2 mL) was added to 100 μL of the crude peptide solution. Accurately, the mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 2 min without light, and the absorbance was measured at 340 nm by microplate reader (Tecan Spark). The standard curve was made with tryptone to determine the peptide content.

2.4. Antioxidant activity

2.4.1. Scavenge ABTS+ radical ability

The testing method was operated according to Cai et al., [17]. Firstly, the working solution was prepared containing 0.5 mL ABTS (7.4 mmol/L) and 0.5 mL K2S2O8 (2.6 mmol/L) and then, the mix was placed for 12 h without light. After diluted by anhydrous ethanol, the working solution was checked by an absorbance value of 0.7 ± 0.02 at 734 nm in advance. For the sample group, the 0.8 mL working solution was added with 0.2 mL sample (2.5 mg/mL) and left to stand for 6 min. The anhydrous ethanol was added with working solution for blank. Finally, all groups were measured at 734 nm, and blank and sample group were recorded as Ablank and Asample, respectively. The antioxidant capacity of ABTS+ scavenging rate was calculated through the following equation:

ABTS+ radical scavenging (%) = (Ablank - Asample)/Ablank × 100.

2.4.2. Fe2+ chelating activity

The assay method was referred to the study of Zhao et al., [18]. The solution mixture was prepared by 1.0 mL of sample (1 mg/mL), 3.7 mL of ultrapure water, and 0.1 mL of FeCl2 (2 mmol/L). Then the phenanthroline (5 mmol/L, 0.2 mL) was supplemented to inspire the reaction. For the control group, the ultrapure water was used to replace the peptide solution and for the blank group the ultrapure water was used to replace FeCl2 and phenanthroline. The mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 20 min before measuring. Finally, the measurement absorbance was 562 nm and Fe2+ chelating rate was obtained according to following formula:

Fe2+ chelating rate (%) = [1 - (Asample - Ablank)/Acontrol] × 100.

2.5. Anti-inflammatory activity

2.5.1. Albumin inhibitory activity

The albumin inhibitory activity was operated referring to the study of Hu et al., [19]. The reaction solution was prepared by sample solution (50 μL) and bovine serum albumin solution (450 μL, dissolved in 0.01 M PBS, pH 7.4, 1 %, w/v). All reaction solutions were stabilized at 37 °C (15 min) and placed at 90 °C (20 min) to induce the denaturation of proteins. The turbidity was measured at 660 nm with a microplate reader at room temperature (25℃). The ultrapure water was used instead of peptides solution as a blank group. The albumin denaturation inhibition rate was computed by the following formula:

2.5.2. NO inhibitory activity

The inhibitory activity on NO was tested referring to the method of Marcocci et al., [20] with slight modifications. Firstly, the sample solution (1 mg/mL, 40 µL) was combined with PBS (0.01 M, pH 7.4, 260 µL) and sodium nitroprusside dihydrate solution (100 mM, 100 µL), and then the tube was placed in a incubator (37 °C, 100 % light intensity) for 2 h. The 100 µL of mixtures were combined with 100 µL of Griess reagent (NO assay kit, Beyotime Biotechnology, China), and then the solutions were placed for 10 min at 25 °C without light. As the blank group, the peptide solution was replaced by ultrapure water. The absorbance of the solutions was measured at 540 nm. The inhibition rate on NO was calculated through the following equation:

2.6. Molecular weight distribution

The molecular weights (MWs) distribution was measured by the superdex peptide HR 10/30 column. During the elution process, the phosphate buffer was prepared by sodium dihydrogen phosphate (50 mM), disodium hydrogen phosphate (50 mM), NaCl (pH 7.0, 100 mM) and the flow rate was 0.8 mL/min. The sample powder was dissolved in ultrapure water to prepare the concentration of 1 mg/mL. The sample injection volume was 1 mL and the detection absorbance was 280 nm. Molecular weight calibration was performed with bovine serum albumin (MWs of 66.5 kDa), lysozyme (MWs of 14.5 kDa), aprotinin (MWs of 6.5 kDa), bacitracin (MWs of 1.4 kDa), hemin (MWs of 0.6 kDa), synthetic peptide FSGL (MWs of 0.4 kDa) and tyrosine (MWs of 0.1 kDa) used as reference proteins.

2.7. Secondary structure

The secondary structure was analyzed using circular dichroism under the sample concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. Here, bandwidth was set to 1 nm and the average residual ellipticity of samples were recorded in the wavelength of 190 ∼ 260 nm. Ultrapure water was used as a blank group and each sample was measured three times. The relative contents of α-helix, β-sheet, β-turns and random coil were calculated using the DichroWeb (https://dichroweb.cryst.bbk.ac.uk/html/home.shtml). The choice of methods was chosen as CDSSTR and Set 4 along with the advanced options of 1.0. Finally, the module of output options was applied as delta epsilon.

2.8. Cell culture and cytotoxicity test

In the cell culture and cytotoxicity test, the PBPs were isolated by a 3 kDa molecular weight (MW) cut-off membrane (EMD Millipore Co., Ltd., Billerica, USA) and then lyophilized to be the peptide powder. The cell culture medium was prepared with DMEM, fetal bovine serum (10 %) along with the supplement of penicillin/streptomycin (1 %). The RAW264.7 cells were cultured in 96-well plates (density of 5,000 cells/well) for growing 24 h. The peptide solution was dissolved in DMEM and filtered by a 0.22 μm filter. The treatment group was incubated with 100 μL of PBPs (1, 5, 10 µg/mL) for 8 h and then, 10 μL of CCK-8 solutions were added for 1 h. The control group was cultured with 100 μL of DMEM for 8 h and then, 10 μL of CCK-8 solution was added, while the blank group was only mixed with 100 μL of DMEM and 10 μL of CCK-8 solutions without cells. The absorbance of the mixtures was measured at 450 nm and the cell viability was obtained through the following formula:

2.9. Determination of inflammatory cytokines

The cells were plated and cultured for 24 h on a 96-well plate with a density of 5,000 cells/well. The inflammatory model was established with the stimulus of LPS (1 ng/mL). After removing the culture medium, the plates were pretreated with PBPs for 2 h and then, the LPS (1 ng/mL) was added. After 6 h, the supernatant was collected and the contents of NO and cytokines were determined using the NO and cytokines kit (S0021, Beyotime, China). As for the TNF-α testing, cell supernatant and standard sample (100 µL) were added to the antibody pre-coated plate and incubated for 90 min in the dark at 37 ℃. The plate was then washed with PBS for 5 times. The biotinylated anti-mouse TNF-α antibody (100 µL) was added to each well for incubation under 37 ℃ for 60 min and washed 5 times. Similarly, horseradish peroxidase labeled avidin (100 µL) was added under 37 ℃ for 30 min. After washing, a color developing agent (100 µL) was added and incubated for 15 min at 37 ℃. Finally, a termination solution was added directly into the mixture. The absorbance of 450 nm was set for measuring different groups and the TNF-α content in the supernatant was calculated according to the standard curve. Again, IL-6 was measured with the same method. The incubation without PBPs was used as negative control (NC). The group treated with only LPS was a positive control (PC). The inhibition rate was calculated as follows:

2.10. Peptides identification

The peptides were prepared by desalting column (PierceTM, 0.5 mL) and then dissolved in 0.1 % formic acid. The sequences of the peptides were analyzed using Nano LC-MS/MS (EASY-nLC 1200, Thermo Scientific) which equipped with a Orbitrap Exploris 480 mass spectrometer (High-Field Asymmetric Waveform Ion Mobility Spectrometry). Peptides were eluted from the analytical column (Acclaim PepMap® RSLC, C18, 75 μm × 15 cm, 3 μm, 100 Å, Thermo Scientific) over a 30 min linear gradient (80 % acetonitrile with 0.1 % FA, 3–35 %) at 0.3 μL/min. The compensation voltage (CV) of mass spectrometer was set at −45 V and −65 V. The peptides were selected by full-scan MS spectra (m/z 350–1500) and MS2 fragmentation (m/z 200). Finally, the resolutions were operated at 60,000 and 15,000 in MS and MS2 scan, respectively. The MS2 fragmentation was followed top intense ions and 1 s cycle time.

2.11. Molecular docking

The interaction mechanism between anti-inflammatory peptide and calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) was analyzed and predicted by AutoDock 4.2 (ScrippsResearch, USA). AutoDock software is made up of AutoGrid and AutoDock. AutoGrid is applied in the calculation of relevant energy in the grid, while AutoDock is mainly used for the conformation search and evaluation. The structure of CaSR (PDB: 7DD7, https://www.rcsb.org/) was optimized, while hydrogenated and ligands were removed. Firstly, the CaSR was wrapped in a larger box with the AutoGrid program, and the grid energy was calculated according to the scanning of different types of atom probes. Secondly, the AutoDock program was used to ligand conformational search within the performed pocket box. Finally, the orientation, position and energy of the ligand was established according to the different conformation.

2.12. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was managed by SPSS 16.0 software. All results were repeated 3 times and expressed as mean ± standard error. Analysis of one-way ANOVA and mean comparisons were performed by Duncan's multiple range test. The SAS 9.2 software was used for two-factor analysis by Fisher's LSD (Least Significant Difference) and Bonferroni method. The significant differences were considered with the P < 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. The effects of ultrasound on the extraction of peptides

Ultrasound is widely used in the food industry as an auxiliary device for a variety of purposes such as extraction, sterilization, emulsification and drying [21], [22], [23]. As shown in Fig. 1, the producing effects of ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis on the generation of PBPs were preliminarily investigated. Compared with the non-ultrasound group (0 W), the ultrasound treatment significantly improved the peptide content, ABTS+ radical scavenging and ferrous ion chelating ability of PBPs at 150 W, 300 W and 450 W, respectively (P < 0.05). When the ultrasound power was increasing, the peptide content was also improved from 74.44 % (0 W) to 86.04 % (300 W, P < 0.05). Meanwhile, the ABTS+ scavenging ability was enhanced from 82.02 % (0 W) to 86.24 % (300 W, P < 0.05). The ferrous ion chelating activity of 450 W group was shown to be much higher than 0 W, which was increased from 80.35 % (0 W) to 87.15 % (450 W, P < 0.05). The cavitation effect of the ultrasonic waves could destroy the crosslinking in collagen, reduce the stability of collagen and improve its solubility [24]. In addition, the ultrasound treatment may also loosen the structure of collagen and give rise to the exposure of enzymolysis sites, which then promoted the extracting capacity of peptides. Generally, the ultrasound with low-power is widely applied in medical diagnosis, meanwhile, the ultrasound with high-power is mainly used as the physical and chemical treatments in the biological matrix as it has the mechanical, and thermal effects [25]. The ultrasound treatment parameters could also affect the extraction efficiency, structure and function of bioactive peptides. To further explore the effect of ultrasound on enzymatic hydrolysis, the powers and treatment time of ultrasound were optimized in the following steps. The treatments of ultrasound-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis were designed under powers of 150 W ∼ 450 W and times of 10 ∼ 60 min, respectively, based on the previous studies performed in our lab.

Fig. 1.

Effect of ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis on the extraction of bioactive peptide from porcine bone. Peptide content (A), (B) ABTS+ radical scavenging rate, (C) ferrous ion chelating activity. Different letters (a–c) represent significant differences (p < 0.05, n = 3).

3.2. Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis

3.2.1. Peptide content

The different powers and treatment times of ultrasound and their interaction had a significant impact on the peptide content (P < 0.05) as shown in Table 1. At the power of 150 W, the peptide content tended to rise with the increase of treatment time up to 20 min. Whereas, under the power of 450 W, the peptides content was decreased at 40 min and 60 min when compared with 10 min and 20 min (P < 0.05). When the ultrasonic treatment time was 10 min, the power of 300 W and 450 W increased the peptide content in comparison to the 150 W (P < 0.05). Under the treatment time of 20 min, the peptide content remained with no significant differences at 150 W, 300 W, 450 W, respectively (P > 0.05), whereas the treatment of 40 min and 60 min decreased the peptide content under a higher power of 450 W (P < 0.05). Short period of ultrasonic treatment will evacuate protein structures and expose more enzymatic hydrolysis sites, which was conducive to enzymatic hydrolysis, while long time and high power ultrasound may lead to protein aggregation. With the increase of ultrasonic energy density, the small bubbles around the solute may be protected by the surrounding bubble clusters to reduce the influence of cavitation. Therefore, a low power with a long time and a high power with a short time could contribute to the improvement of peptide content.

Table 1.

Effect of ultrasonic power and treatment time on peptide content, ABTS+ radical scavenging rate and Fe2+ chelating ability.

| Treat time (min) | Ultrasound power (W) |

SE |

P-Values |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 150 | 300 | 450 | Power | Time | Power × Time | |||

| Peptide content (%) | 10 | 79.66 ± 0.47Bb | 81.56 ± 1.86Aa | 82.24 ± 0.94Aa | 1.30 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 20 | 82.71 ± 1.35Aa | 83.48 ± 1.10Aa | 82.26 ± 0.96Aa | |||||

| 40 | 82.98 ± 1.11Aa | 83.43 ± 0.63Aa | 79.47 ± 1.12Bb | |||||

| 60 | 81.88 ± 0.95Aa | 81.45 ± 1.26Aa | 70.86 ± 1.53Bc | |||||

| ABTS+ radical scavenging (%) | 10 | 82.24 ± 0.60Bb | 84.44 ± 0.98Ab | 82.21 ± 0.57Bb | 5.32 | <0.001 | 0.7420 | 0.9977 |

| 20 | 83.61 ± 0.73Aab | 84.31 ± 0.18Ab | 83.67 ± 0.75Aab | |||||

| 40 | 84.77 ± 0.90Aa | 86.24 ± 0.67Aa | 85.46 ± 0.58Aa | |||||

| 60 | 82.10 ± 1.41Bb | 86.06 ± 0.72Aa | 84.23 ± 1.64ABab | |||||

| Fe2+ chelating ability (%) | 10 | 79.23 ± 0.62Bb | 80.09 ± 0.60Bb | 87.03 ± 1.88Ab | 1.6 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 20 | 79.70 ± 0.82Bb | 81.31 ± 3.41Bb | 94.54 ± 1.42Aa | |||||

| 40 | 79.62 ± 0.85Cb | 82.72 ± 1.48Bb | 87.60 ± 0.82Ab | |||||

| 60 | 83.39 ± 0.60Ba | 87.26 ± 0.93Aa | 87.15 ± 2.68Ab | |||||

1P-Values indicate the level of significance including ultrasound power, treatment time and their interaction.

2SE: standard error.

3Different letters (A-C) in the same row indicate a significant difference between ultrasound power (P < 0.05).

4Different letters (a-c) in the same column indicate significant difference between treatment time (P < 0.05).

3.2.2. Antioxidant activities of PBPs

It is generally known that the excessive free radicals will cause the oxidative stress in body, which will change the physiological level of organs and further induce autophagy, trigger apoptosis, and cause irreversible tissue damage [26]. The ABTS+ radical is the most widely used indirect assay for the determination of free radical scavenging capacity and can be used to determine the antioxidant capacity of hydrophilic and lipophilic substances. The effect of ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis on the ABTS+ radical scavenging activity of PBPs is presented in Table 1. Generally, the power of ultrasound treatment posed to exert a significant effect on the ABTS+ scavenging rate (P < 0.05). When the time was 10 min, the treatment of 300 W showed a higher ABTS+ activity of PBPs than 150 W and 450 W (P < 0.05), whereas it remained unchanged at 20 min and 40 min under different powers (P > 0.05). When the ultrasound power was 450 W, the ABTS+ activity had no significant differences among the treatments of 20 min, 40 min and 60 min (P > 0.05). He et al., [27] investigated the capacity of ultrasound time on antioxidant peptides obtained from hydrolysis of yak skin gelatin and reported that a short time of ultrasound (5 min) could improve the antioxidant capacity of peptides. However, a long time of ultrasound (10 min) would lead to molecular aggregation, inhibition of protease hydrolysis, and gradually decrease in the contents of Tyr, Pro and Ala, which suppressed the formation of hydrogen donors.

Metal chelating indirectly participates in antioxidant activity due to the Fenton reaction, which can suppress the metal ions catalysis, and then reduce the generation of oxidation reactions. The influence of ultrasound treatment on the Fe2+ chelating of PBPs is shown in Table 1. Generally, the ultrasonic power, ultrasonic time and their interaction had significant effects on the Fe2+ chelating ability of PBPs. At the same power (150 W and 300 W), the time of 60 min possessed a higher Fe2+ chelating ability than other treatment times (P < 0.05). Under the power of 450 W, the time of 20 min exhibited a much higher Fe2+ chelating ability than other treatment times (P < 0.05). The current study primarily demonstrates that moderate ultrasound can improve the antioxidant activity of PBPs. Known from the relationship between structure and function of bioactive peptides, the residues of Val, Leu, Pro, Tyr and Ala may play an important and key role in antioxidant ability [28] and the release of these hydrophobic amino acids was related to the influence of ultrasound on protein structure. Moderate ultrasound had the beneficial effect on exposing the hydrophobic groups, while excessive ultrasound led to protein aggregation with the resistance on releasing hydrophobic groups. Thus, the bioactive peptides with a higher antioxidant activity can be obtained by enzymatic hydrolysis when the protein structure was loosened and the hydrophobic groups were exposed. Based on the peptide content, ABTS+ radical scavenging rate and Fe2+ chelating activity, the treatment groups were demonstrated to be more effective on the extraction of PBPs including the group of 40 min at 150 W, the groups of 20 min, 40 min, and 60 min at 300 W, as well as the groups of 20 min, 40 min at 450 W, which were then selected for further investigation on the anti-inflammatory activities as well as the peptide profiles of PBPs.

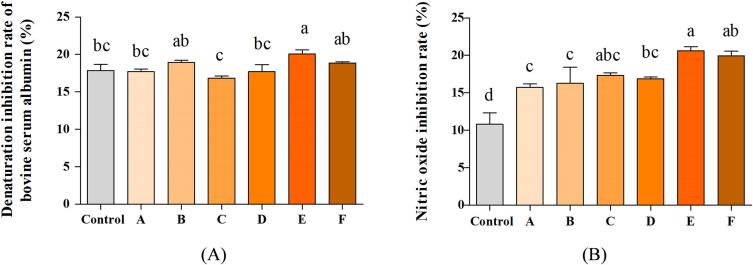

3.2.3. Chemical anti-inflammatory activity

In order to testing the anti-inflammatory activity of PBPs, the bovine serum albumin denaturation rate and NO inhibition activities were investigated. The important properties of the anti-inflammatory agents consist in the ability to inhibit the thermal denaturation of serum albumin. Generally, the PBPs produced by different ultrasound conditions posed to have different suppressing effects on bovine serum albumin denaturation (Fig. 2A). Compared with control (17.85 %), the ultrasound of 450 W with 20 min exhibited a higher inhibition rate of 20.08 % on bovine serum albumin denaturation (P < 0.05). No significant differences were shown between the other ultrasound treatments and the control group (P > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

The anti-inflammatory activity of PBPs. Bovine serum albumin denaturation inhibitory activity (A), (B) nitric oxide inhibitory activity. Control means no ultrasound treatment, the letter A, B, C, D, E, F mean the treatment groups of 150 W 40 min, 300 W 20 min, 300 W 40 min, 300 W 60 min, 450 W 20 min, and 450 W 40 min, respectively. Different letters (a-d) represent significant differences (p < 0.05, n = 3).

When the viral and pathogenic organisms invade the immune cells, the molecular nitric oxide is elevated, and the excessive production of NO can induce cell inflammation cascade reaction. Therefore, the inhibitory effect on NO secretion is the primary biological index to reflect the anti-inflammatory capacity of bioactive peptides [29]. As shown in Fig. 2B, the ultrasound-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis significantly improved the NO inhibition rate of PBPs (P < 0.05). Compared with non-ultrasound, the PBPs in treatment of 450 W (20 min) had much higher inhibition rates on NO (P < 0.05). The inhibition rates were increased from 10.80 % to 20.62 %, which were 1.91 times higher than the control. The other ultrasound groups of PBPs also exhibited significant NO inhibitory activities which were higher than the control (P < 0.05).

3.3. The composition of PBPs

The molecular weights (MWs) distribution of the PBPs was correlated with its functional properties. In the statistical analysis, peptide distribution was divided into five intervals according to their molecular weights, which included < 500 Da, 500–1,000 Da, 1,000–3,000 Da, 3,000–8,000 Da, and > 8,000 Da. According to the results of Table 2, the content of small molecular weight (<3,000 Da) peptides was increased in all ultrasound groups except 450 W of 40 min, and ultrasound significantly changed the MWs distribution of the peptides (P < 0.05). More small peptides (MWs < 3,000 Da) were generated in the group of 150 W and 40 min. Derived from chickpea protein hydrolysate, the bioactive peptides with the MWs of 200–3,000 Da posed to have higher hydrophobic amino acid content as well as stronger antioxidant activity than other contents [30]. Consistent with the results of Zhu et al., [31], the current research also demonstrated the ultrasonic treatment of PBPs had a higher antioxidant activity than the control, where a higher content of peptides with less than 3,000 Da showed a stronger antioxidant activity of PBPs.

Table 2.

Effect of ultrasound on molecular weight distribution and the secondary structure.

| Percentage content (%) | Control | 150 W 40 min | 300 W 20 min | 300 W 40 min | 300 W 60 min | 450 W 20 min | 450 W 40 min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular weights distribution | <500 Da | 45.25 ± 0.60d | 54.72 ± 0.07a | 47.49 ± 0.95bc | 46.99 ± 0.48c | 46.50 ± 0.51cd | 48.69 ± 1.09b | 45.11 ± 0.74d |

| <1 kDa | 58.99 ± 0.71c | 67.48 ± 0.18a | 61.46 ± 1.07b | 60.95 ± 0.34b | 60.67 ± 0.27b | 62.20 ± 1.31b | 58.39 ± 0.68c | |

| <3 kDa | 76.04 ± 0.69c | 82.25 ± 0.41a | 78.57 ± 0.86b | 78.80 ± 0.24b | 78.11 ± 0.06b | 78.89 ± 1.23b | 76.09 ± 0.43c | |

| <8 kDa | 87.89 ± 0.65c | 91.56 ± 0.51a | 90.01 ± 0.65b | 90.44 ± 0.27ab | 89.66 ± 0.29b | 89.91 ± 1.04b | 88.09 ± 0.44c | |

| Secondary structure | α-helix | 29.33 ± 4.93c | 44.33 ± 1.15b | 44.00 ± 0.00b | 48.67 ± 1.15a | 51.33 ± 0.58a | 42.67 ± 0.58b | 52.33 ± 0.58a |

| β-chain | 38.00 ± 7.81a | 34.67 ± 0.58ab | 34.00 ± 1.00abc | 30.67 ± 0.58bc | 28.67 ± 1.53c | 35.00 ± 0.00ab | 28.67 ± 1.53c | |

| random coil | 34.33 ± 7.50a | 21.33 ± 0.58b | 21.67 ± 0.58b | 20.33 ± 0.58b | 20.00 ± 0.00b | 22.00 ± 0.00b | 19.67 ± 0.58b |

Different letters (a-d) in the same row indicate significant differences between different ultrasound treatments (P < 0.05).

With the objective of evaluating the secondary structure of PBPs, the circular dichroism (CD) method was used in current study. Obviously, the secondary structure of PBPs was changed by ultrasound (Table 2), where the content of α-helix was improved and random coil was suppressed. In the treatment of 300 W (40 min), 300 W (60 min) and 450 W (40 min), the β-chain all showed to be decreased in relation to the control (P < 0.05) and there were no significant differences between other ultrasound treatments and control (P > 0.05). Ren et al., [32] also reported the consistent changes in the secondary structure of zein during ultrasonic treatment, where the subunit structure of the peptide chain was loosened due to the movement of hydrophobic groups, and induced the exposure of Phe, Trp and Tyr in the peptides side chain. The α-helix is stabilized by a combination of hydrophobic and pile-up interactions and H-bond and electrostatic interactions [33]. Known from the sequence of anti-inflammatory peptides, the positively charged and hydrophobic amino acids at the N and C ends of the peptides chain promoted its anti-inflammatory activity [16]. Therefore, the increasing content of α-helix indicated that the hydrophobic groups were exposed by ultrasound leading to the improved anti-inflammatory capacity of the peptide as the solution was more uniform and stable.

Based on the above research results, the optimal condition of ultrasound treatment was ultrasonic power of 450 W with treatment time of 20 min. In addition, the MWs distribution of anti-inflammatory peptides was concentrated in the sizes below 3 kDa [19], [34]. Thus, in the follow-up of the study, the PBPs with molecular weight below 3 kDa were obtained by ultrafiltration, and RAW264.7 cells were used to establish inflammation model to further investigate the anti-inflammatory activities of PBPs.

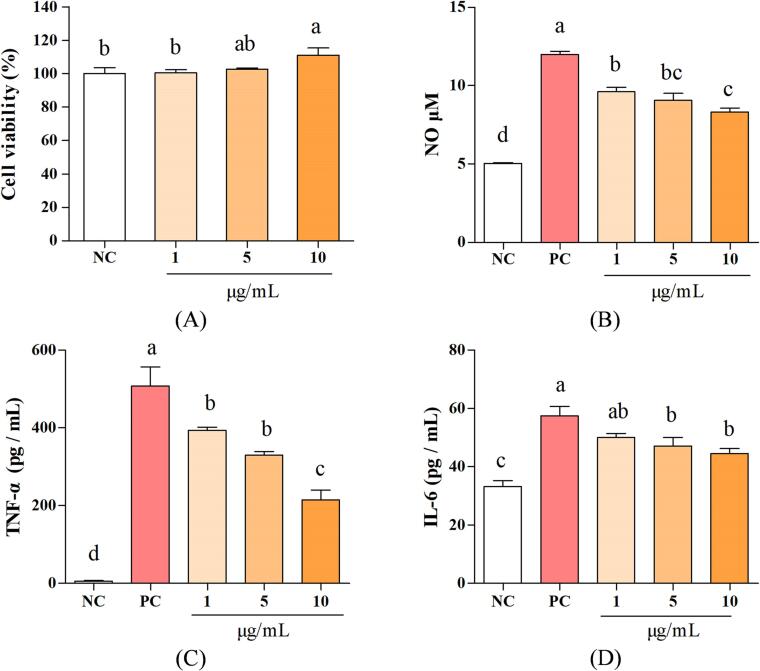

3.4. Anti-inflammatory effect of PBPs in RAW264.7 cells

Inflammation is an immune response that assists the body in removing invaded immunogens. When the body's immune system is damaged, the relevant immune cells will release much more inflammatory mediators. NO is a signaling molecule associated with inflammatory response, and then, it stimulates the macrophage cells to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, etc.) by activating cell signal pathways such as nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) and MAPK. To further verify the anti-inflammatory activity of PBPs, different doses of PBPs were used to be incubated in RAW264.7 cells along with the investigation on the release of TNF-α and IL-6 cytokines.

Known from Fig. 3A, the PBPs treatment (1, 5, 10 μg/mL) had no cytotoxicity on the cell vitality. In compare with the NC group (100 %), the vitality of 10 μg/mL treatment group was increased to 111 %, which had an improving effect on the cells. For the NO secretion, the treatments with 1, 5 and 10 μg/mL PBPs significantly decreased NO content to 34.39 %, 42.17 % and 52.96 %, respectively, when compared with PC (Fig. 3B, p < 0.05). Similarly, the PBPs also significantly diminished the secretion of cellular inflammatory factor TNF-α, as shown in Fig. 3C. Compared with the PC group, PBPs treatment (1, 5 and 10 μg/mL) inhibited the secretion of TNF-α by 22.67 %, 35.44 % and 58.31 %, respectively. The secretion of IL-6 was also decreased under the PBPs treatment (Fig. 3D). Compared with the PC group, PBPs treatment (5 and 10 μg/mL) attenuated the secretion of IL-6 by 42.63 %, and 53.31 %, respectively. According to the above results, the PBPs can reduce the release of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 in LPS induced RAW264.7 cells, which indicated a suppressing effect on inflammatory condition.

Fig. 3.

The anti-inflammatory activity of the PBPs in RAW264.7 cell. Cell viability (A), the effects of the NO (B), TNF-α (C) and IL-6 (D) secretion in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. NC means negative control; PC means positive control. Different letters (a-d) represent significant differences (p < 0.05, n = 3).

3.5. The sequences in PBPs

Based on the above results, the best anti-inflammatory activity of PBPs was obtained when the ultrasonic power was 450 W with treatment time of 20 min. The sequences in PBPs were further measured by the Nano-LC-MS/MS analysis. The data were then sequenced by PEAKS Studio X Pro with the module of de novo analysis. A total of 247 high-confidence peptide sequences (ALC%=99 %) were identified as shown in Table S1. The number of amino acid residues in PBPs was shown in Fig. 4. The length of PBPs was mainly concentrated in heptapeptide, octapeptide, nonapeptide, decapeptide, dodecapeptide, accounting for 67 % of the total sequences. PeptideRanker (https://distilldeep.ucd.ie/ PeptideRanker/) is a system peptide database with the predicated threshold value (>0.5) for the bioactivity of peptides, where the higher of the value, the stronger of its bioactivity. There were 150 peptides predicted with bioactivity, which accounting for 61 % of the identified sequences. Among bioactive peptide sequences, there were 83 % hydrophobic amino acids at the N-terminal, with glycine accounting for 51 %, proline accounting for 8 %. C-terminal possessed 61 % hydrophobic amino acids, including alanine, leucine, and proline, accounting for 15 %, 11 %, and 10 %, respectively. Ultrasound played a crucial role in the exposure of hydrophobic groups. The structure of the PBPs sequences conformed to the general structural pattern of α-helix. A large number of Gly and Pro in the sequence was consistent with the characteristic amino acids of collagen. Known from the sequences of identified peptides, the Gly and Pro were mostly sited in end peptides chain. It was worth noting that the existing of hydrophobic amino acids was helpful for the anti-inflammatory activity of peptides.

Fig. 4.

The distribution of peptide length and quantity of PBPs in external layer pie plot, as well as the distribution of its bioactive peptides (score > 0.5) at internal layer pie plot.

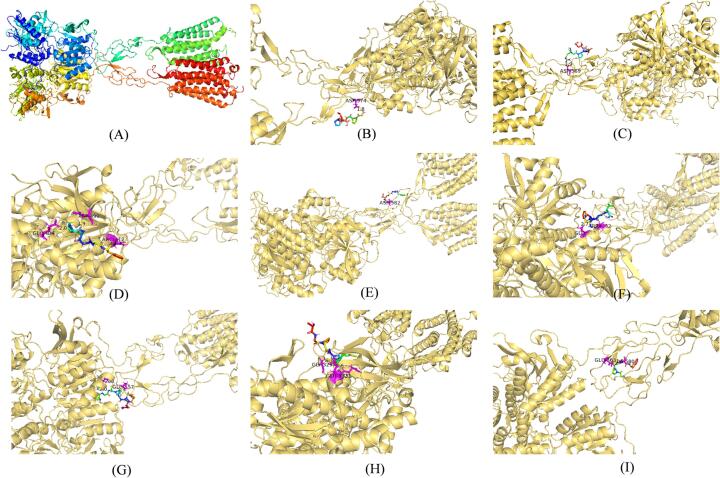

3.6. Molecular docking

Belong to the G-protein-coupled receptor, the Calcium sensitive receptor (CaSR) is expressed widely in a variety of tissues. As a signaling molecule, CaSR plays a crucial role in maintaining calcium homeostasis, and regulating apoptosis, proliferation, differentiation and ion channel activity, and the CaSR activation is a potential target for the immune regulating effect of bioactive peptides [35]. In the docking process, the protein and ligand recognize each other, optimize the conformation, minimize the free energy of the system, and then predict the affinity and binding pattern between the protein and ligand. The binding energy and predicted bioactivity of PBPs were shown in Table 3. According to the predicted bioactivity score, the peptide sequences with scores > 0.85 were further screened for docking with CaSR protein. The smaller of value (<0) means a tight interaction between CaSR and peptides. Finally, eight sequences corresponding to GPGPM, RGPPGPM, PSGGF, VGGF, FSGL, PGSPGPGPR, AGPGPM and GPTGF with the lowest binding energy were selected. Consistent with the structure of collagen, the eight sequences contained high amounts of glycine and proline, which was generally characterized by repetitions of the “glycine-X-Y” structural domain. Anna et al., [36] extracted proteins from cereals and reported that the anti-inflammatory peptides were rich in glycine site. Derived from the Xuanwei ham, the peptide sequences of GPAGPL and GPPGAP were also demonstrated with a high anti-inflammatory activity, which possessed a higher content of glycine and proline [16]. In addition, the identified peptide sequences were searched in the peptides databases (https://www.cqudfbp.net/; https://biochemia.uwm.edu.pl/biopep-uwm/), where the eight sequences with strong anti-inflammatory activity were not reported before. Thus, these anti-inflammatory peptides derived from porcine bone collagen were firstly identified and evaluated.

Table 3.

Peptide sequence docking with CaSR.

| Peptide | Predicted peptide bioactive* | Binding energy (kcal/mol)# |

Total internal (kcal/mol)# |

Hydrogen bonds formed site# | Number of hydrogen bond# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPGPM | 0.945631 | −3.67 | −2.71 | ASP574 | 1 |

| RGPPGPM | 0.899236 | −2.94 | −4.5 | ASP569 | 1 |

| PSGGF | 0.939871 | −2.78 | −1.84 | GLU404; ARG312; ASP499 | 3 |

| VGGF | 0.864736 | −2.76 | −3.28 | ASP582 | 1 |

| FSGL | 0.886782 | −2.69 | −3.05 | GLU228; GLU232 | 2 |

| PGSPGPGPR | 0.88636 | −2.65 | −5.01 | ASP238; GLU232; GLU557 | 3 |

| AGPGPM | 0.893418 | −2.59 | −3.81 | GLY329; ARG331; GLU332 | 3 |

| GPTGF | 0.882733 | −2.51 | −3.9 | GLU563; ALA580 | 2 |

| PPSGGF | 0.942908 | −2.1 | −3.59 | GLU756; TRP589 | 4 |

| ASGPPGFA | 0.88438 | −1.03 | −6.55 | ASP574; GLU575 | 2 |

| FPFPLPK | 0.972642 | −0.78 | −8.18 | GLU228 | 1 |

| FDFR | 0.967235 | −0.38 | −4.97 | ASP234 | 1 |

| GPPGFPGAV | 0.889442 | −0.25 | −6.18 | null | null |

| PGPMGPSGPR | 0.865403 | 0.33 | −5.91 | ASP234 | 1 |

| GGFDFSFL | 0.955287 | 2.33 | −7.91 | null | null |

| GPAGPPGPPGPPGPPGPS | 0.944428 | 2.73 | −10.53 | TYR572 | 1 |

| GPAGLMGPPGLG | 0.924925 | 2.77 | −7.38 | null | null |

| GPDGF | 0.940609 | 4.1 | 0 | null | null |

| GPPGPPGPPGPPGPPSGGF | 0.973698 | null | null | null | null |

| GPSGPSGERGPPGPM | 0.897603 | null | null | null | null |

| GERGPPGPMGPPGL | 0.887363 | null | null | null | null |

| GPSGERGPPGPM | 0.861882 | null | null | null | null |

PeptideRanker (https://distilldeep.ucd.ie/ PeptideRanker/) is a system peptide database with the predicated value for the bioactivity of peptides. #AutoDock is applied to simulate the binding of different molecules, including binding energy, total internal, as well as the site and number of hydrogen bonds.

The structure of CaSR was shown in Fig. 5A. Besides, the binding energy of GPGPM (peptide ranker score 0.94) was −3.67 kcal/mol. One hydrogen bond was formed at amino acid residue ASP574 (Fig. 5B). The binding energy of RGPPGPM (peptide ranker score 0.90) was −2.94 kcal/mol. One hydrogen bond was formed at amino acid residue ASP569 (Fig. 5C). The binding energy of PSGGF (peptide ranker score 0.94) was −2.78 kcal/mol. Three hydrogen bonds were formed at amino acid residues GLU404, ARG312 and ASP499 (Fig. 5D). The binding energy of VGGF (peptide ranker score 0.86) was −2.76 kcal/mol. One hydrogen bond was formed at amino acid residue ASP582 (Fig. 5E). The binding energy of FSGL (peptide ranker score 0.89) was −2.69 kcal/mol. Two hydrogen bonds were formed at amino acid residues GLU228, GLU232 (Fig. 5F). The binding energy of PGSPGPGPR (peptide ranker score 0.89) was −2.65 kcal/mol. Three hydrogen bonds were formed at amino acid residues ASP238, GLU232, GLU557 (Fig. 5G). The binding energy of AGPGPM (peptide ranker score 0.89) was −2.59 kcal/mol. Three hydrogen bonds were formed at amino acid residues GLY329; ARG331; GLU332 (Fig. 5H). The binding energy of GPTGF (peptide ranker score 0.88) was −2.51 kcal/mol. Two hydrogen bonds were formed at amino acid residues GLU563; ALA580 (Fig. 5I). The interaction of active sites in the VFT domain of CaSR may help increase the agonist activity of CaSR, it had been reported that the VFT domain of human CaSR proteins started from PRO22 to ILE528 [37]. The docking sites of sequence PSGGF, FSGL, PGSPGPGPR, and AGPGPM were all located in the VFT domain, indicating their potential effect on regulating CaSR. In the CaSR homology model, the binding pocket contained a hydrophobic distal portion that accommodated the side chains of hydrophobic amino acid ligands such as phenylalanine and tryptophan, which may explain the preference for aromatic amino acids in enhancing CaSR [38]. In current study, PSGGF, VGGF, FSGL, and GPTGF were occupied by phenylalanine at one end. The position of the amino acid binding site in CaSR was equivalent to the glutamate binding site in mGluRs [38], which also indicated that the binding site in GLU was particularly important when the ligands bind to CaSR, such as PSGGF, FSGL, PGSPGPGPR, AGPGPM, GPTGF. Subsequently, these eight sequences will be synthesized to investigate the regulation between the CaSR activation as well as the anti-inflammatory effects of peptides in porcine bones.

Fig. 5.

The peptides docking with CaSR. The structure of CaSR (A). CaSR bound to GPGPM at ASP574 (B), bound to RGPPGPM at ASP569 (C), bound to PSGGF at GLU404; ARG312; ASP499 (D), bound to VGGF at ASP582 (E), bound to FSGL at GLU228; GLU232 (F), bound to PGSPGPGPR at ASP238; GLU232; GLU557 (G), bound to AGPGPM at GLY329; ARG331; GLU332 (H), bound to GPTGF at GLU563; ALA580 (I).

4. Conclusion

In this study, the ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis was optimized for the extraction of bioactive peptides from porcine bone. In addition, the strongest anti-inflammatory activities of PBPs were obtained when the ultrasonic power was 450 W with treatment time of 20 min. The anti-inflammatory capacity of peptides was verified in RAW264.7 cells, where the release of NO, IL-6 and TNF-α were all suppressed with a higher concentration of PBPs treatments (5 and 10 μg/mL). Analyzed by LC-MS/MS, there were 247 bioactive peptides identified in PBPs. After predicated by Peptidesranker, the higher bioactivities of PBPs were screened for docking with CaSR, a key protein in inflammation regulation. Subsequently, eight sequences were identified according to their binding energy, which was more likely to exhibit stronger anti-inflammatory effects through the activation of CaSR. Above, the current study firstly clarified the improving effect of ultrasound in the extraction of porcine bone peptides, which also established a primary basis for the development of anti-inflammatory peptides in bone collagen. In the future, the relationship between anti-inflammatory effect of PBPs and its regulation mechanism would be further demonstrated.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yuejing Hao: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Software, Writing – original draft. Lujuan Xing: Project administration, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Zixu Wang: Writing – review & editing, Software. Jiaming Cai: Investigation, Methodology. Fidel Toldrá: Writing – review & editing. Wangang Zhang: Project administration, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32001720).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106697.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Brij P.S., Shilpa V., Subrota H. Functional significance of bioactive peptides derived from soybean. Peptides. 2014;54:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samaraweera H., Zhang W., Lee E.J., Ahn D.U. Egg yolk phosvitin and functional phosphopeptides–review. J. Food Sci. 2011;76:143–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xing L., Liu R., Cao S., Zhang W., Zhou G. Meat protein based bioactive peptides and their potential functional activity: a review. Int. J. Food Sci. 2019;54:56–66. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.14132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortial D., Gouttenoire J., Rousseau C.F., Ronzière M.C., Piccardi N., Msika P., Herbage D., Mallein-Gerin F., Freyria A.M. Activation by IL-1 of bovine articular chondrocytes in culture within a 3d collagen-based scaffold. an in vitro model to address the effect of compounds with therapeutic potential in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartilage. 2006;14:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan L., Chu Q., Wu X., Yang B., Zhang W., Jin W., Gao R. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity of peptides from ethanol-soluble hydrolysates of sturgeon (acipenser schrenckii) cartilage. Front. Nutr. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.689648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao C., Xiao Z., Tong H., Liu Y., Wu Y., Ge C. Oral intake of chicken bone collagen peptides anti-skin aging in mice by regulating collagen degradation and synthesis, inhibiting inflammation and activating lysosomes. Nutrients. 2022;14:1622. doi: 10.3390/nu14081622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miao B., Zheng J., Zheng G., Tian X., Zhang W., Yuan F., Yang Z. Using collagen peptides from the skin of monkfish (lophius litulon) to ameliorate kidney damage in high-fat diet fed mice by regulating the nrf2 pathway and nlrp3 signaling. Front. Nutr. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.798708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrera-Alvarado G., Toldrá F., Mora L. Potential of dry-cured ham bones as a sustainable source to obtain antioxidant and DPP-IV inhibitory extracts. Antioxidants. 2023;12:1151. doi: 10.3390/antiox12061151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jordi P., Ricardo B., Albert I. Effect of enzymatic hydrolyzed protein from pig bones on some biological and functional properties. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2021;58:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s13197-020-04950-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murtaza M.A., Irfan S., Hafiz I., Ranjha M.M.A.N., Rahaman A., Murtaza M.S., Ibrahim S.A., Siddiqui S.A. Conventional and novel technologies in the production of dairy bioactive peptides. Front. Nutr. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.780151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amir A., Parisa S., Nafiseh S. Application of ultrasound treatment for improving the physicochemical, functional and rheological properties of myofibrillar proteins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;111:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.12.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bedin S., Netto F.M., Bragagnolo N., Taranto O.P. Reduction of the process time in the achieve of rice bran protein through ultrasound-assisted extraction and microwave-assisted extraction. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2020;55:300–312. doi: 10.1080/01496395.2019.1577449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He L., Gao Y., Wang X., Han L., Yu Q., Shi H., Song R. Ultrasonication promotes extraction of antioxidant peptides from oxhide gelatin by modifying collagen molecule structure. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;78 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou C., Hu J., Yu X., Yagoub A.E.A., Zhang Y., Ma H., Gao X., Otu P.N.Y. Heat and/or ultrasound pretreatments motivated enzymolysis of corn gluten meal: hydrolysis kinetics and protein structure. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017;77:488–496. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.06.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao S., Wang Y., Xing L., Zhang W., Zhou G. Structure and physical properties of gelatin from bovine bone collagen influenced by acid pretreatment and pepsin. Food Bioprod. Process. 2020;121:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2020.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu L., Xing L., Hao Y., Yang Z., Teng S., Wei L., Zhang W. The anti-inflammatory effects of dry-cured ham derived peptides in raw264.7 macrophage cells. J. Funct. Foods. 2021;87 doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2021.104827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cai J., Xing L., Zhang W., Fu L., Zhang J. Selection of potential probiotic yeasts from dry-cured xuanwei ham and identification of yeast-derived antioxidant peptides. Antioxidants. 2022;11:1970. doi: 10.3390/antiox11101970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao J., He J., Dang Y., Cao J., Sun Y., Pan D. Ultrasound treatment on the structure of goose liver proteins and antioxidant activities of its enzymatic hydrolysate. J. Food Biochem. 2020;44:e13091. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu S., Yuan J., Gao J., Wu Y., Meng X., Tong P., Chen H. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential of peptides derived from in vitro gastrointestinal digestion of germinated and heat-treated foxtail millet (setaria italica) proteins. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2020;68:9415–9426. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c03732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcocci L., Maguire J.J., Droylefaix M.T., Packer L. The nitric oxide-scavenging properties of ginkgo biloba extract egb 761. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Co. 1994;201:748–755. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou L., Zhang J., Lorenzo J.M., Zhang W. Effects of ultrasound emulsification on the properties of pork myofibrillar protein-fat mixed gel. Food Chem. 2021;345 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang D., Zhang W., Lorenzo J.M., Chen X. Structural and functional modification of food proteins by high power ultrasound and its application in meat processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020;61 doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1767538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou L., Zhang J., Xing L., Zhang W. Applications and effects of ultrasound assisted emulsification in the production of food emulsions: a review. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2021;110 doi: 10.1016/J.TIFS.2021.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L., Li J., Teng S., Zhang W., Purslow P.P., Zhang R. Changes in collagen properties and cathepsin activity of beef m semitendinosus by the application of ultrasound during post-mortem aging. Meat Sci. 2021;185 doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2021.108718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shekhar U.K., Brijesh K.T., Carlos Á., Colm P.O. Ultrasound applications for the extraction, identification and delivery of food proteins and bioactive peptides. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2015;46:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2015.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruan S., Li Y., Wang Y., Huang S., Luo J., Ma H. Analysis in protein profile, antioxidant activity and structure-activity relationship based on ultrasound-assisted liquid-state fermentation of soybean meal with bacillus subtilis. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;64 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He L., Han L., Wang Y., Yu Q. Appropriate ultrasonic treatment improves the production of antioxidant peptides by modifying gelatin extracted from yak skin. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2022;57:5897–5908. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.15912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eckert E., Lu L., Unsworth L.D., Chen L., Xie J., Xu R. Biophysical and in vitro absorption studies of iron chelating peptide from barley proteins. J. Funct. Foods. 2016;25:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2016.06.011.E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Udenigwe C.C., Je J., Cho Y., Yada R.Y. Almond protein hydrolysate fraction modulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and enzymes in activated macrophages. Food Funct. 2013;4:777–783. doi: 10.1039/C3FO30327F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y., Jiang B., Zhang T., Mu W., Liu J. Antioxidant and free radical-scavenging activities of chickpea protein hydrolysate (cph) Food Chem. 2007;106:444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.04.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu K., Su C., Guo X., Peng W., Zhou H. Influence of ultrasound during wheat gluten hydrolysis on the antioxidant activities of the resulting hydrolysate. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2011;46:1053–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2011.02585.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren X., Ma H., Mao S., Zhou H. Effects of sweeping frequency ultrasound treatment on enzymatic preparations of ace-inhibitory peptides from zein. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2014;238:435–442. doi: 10.1007/s00217-013-2118-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi Z., Olson C.A., And A., Kallenbach N.R. Stabilization of alpha-helix structure by polar side-chain interactions: complex salt bridges, cation-pi interactions, and C-H em leader O H-bonds. Biopolymers. 2001;60:366–380. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)60:5<366::AID-BIP10177>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suttisuwan P., Saisavoey S., Thongchul K. Isolation and characterization of anti-inflammatory peptides derived from trypsin hydrolysis of microalgae protein. Food Biotechnol. 2019;33:303–324. doi: 10.1080/08905436.2019.1673171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xing L., Hua Z., Majumder K., Zhang W., Y. Mine, Glutamylvaline prevents low-grade chronic inflammation via activation of calcium-sensing receptor pathway in 3T3-L1 mouse adipocytes. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2019:8361–8369. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b02334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jakubczyk A., Szymanowska U., Karaś M., Złotek U., KowalczykJ D. Potential anti-inflammatory and lipase inhibitory peptides generated by in vitro gastrointestinal hydrolysis of heat treated millet grains. CyTA-J. Food. 2019;17:324–333. doi: 10.1080/19476337.2019.1580317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo D., He H., Hou T. Purification and characterization of positive allosteric regulatory peptides of calcium sensing receptor (CaSR) from desalted duck egg white - sciencedirect. Food Chem. 2020;325 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang M., Hampson D.R. An evaluation of automated in silico ligand docking of amino acid ligands to family C G-protein coupled receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:2032. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.