Abstract

Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) contamination seriously threatens nutritional safety and common health. Bacterial CotA-laccases have great potential to degrade AFB1 without redox mediators. However, CotA-laccases are limited because of the low catalytic activity as the spore-bound nature. The AFB1 degradation ability of CotA-laccase from Bacillus licheniformis ANSB821 has been reported by a previous study in our laboratory. In this study, a Q441A mutant was constructed to enhance the activity of CotA-laccase to degrade AFB1. After the site-directed mutation, the mutant Q441A showed a 1.73-fold higher catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) towards AFB1 than the wild-type CotA-laccase did. The degradation rate of AFB1 by Q441A mutant was higher than that by wild-type CotA-laccase in the pH range from 5.0 to 9.0. In addition, the thermostability was improved after mutation. Based on the structure analysis of CotA-laccase, the higher catalytic efficiency of Q441A for AFB1 may be due to the smaller steric hindrance of Ala441 than Gln441. This is the first research to enhance the degradation efficiency of AFB1 by CotA-laccase with site-directed mutagenesis. In summary, the mutant Q441A will be a suitable candidate for highly effective detoxification of AFB1 in the future.

Keywords: CotA-laccase, Bacillus licheniformis, Site-directed mutagenesis, Aflatoxin B1

1. Introduction

Mycotoxins are secondary metabolites produced by molds [1]. Nearly 25 % of the world's food supply is contaminated with mycotoxins each year [2]. The most common mycotoxins in food and feed are aflatoxins [3]. The four main natural aflatoxins are aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), aflatoxin B2, aflatoxin G1 and aflatoxin G2 [4]. Among these four kinds of aflatoxins, AFB1 receives particular attention because of the severe carcinogenicity and immunotoxicity to humans and animals [5]. Different approaches have been used to remove AFB1 from grains, such as ammoniation, irradiation, adsorption, ozonation and peroxidation [6]. However, these methods are expensive and cause adverse effects on nutritional value of cereals [6]. Because of the depressed performance of traditional physical and chemical approaches to remove AFB1, biological methods have shown great potential in AFB1 degradation [7]. At present, there are many reports about the enzymatic detoxification of AFB1. Among these enzymes, laccase has attracted much attention for its good detoxification effect [8].

Laccases are enzymes that can catalyze various phenolic compounds, and reduce molecular oxygen to water to oxidize aromatic compounds [9]. They are widely distributed among plants, insects, fungi and bacteria [10]. In plants, laccases are implicated in cell wall lignification [11]. In insects, laccases participate in lignin degradation and cuticle sclerotization [12]. In fungi, laccases are related to plant pathogenesis and lignin degradation [13]. In bacteria, laccases are involved in melanin production and copper detoxification [14].

Laccases have been considered to be biological green tools to remove environmental pollutants [15]. A number of laccases, such as fungal and bacterial laccases, have been demonstrated to have the ability to degrade AFB1. The laccases from Trametes versicolor could directly oxidize AFB1, and the mutagenicity and prooxidative abilities of the degradation products were reduced compared to AFB1 [16]. Song and coworkers reported that Pleurotus pulmonarius laccase 2 was able to detoxify 99.82 % of AFB1 in the presence of acetosyringone [17]. However, fungal laccases are usually unstable under high temperature and alkaline condition, thus limiting their practical applications in aflatoxin detoxification in food and feed processing as several processing steps (such as maize gelatinization processing, maize puffing, and the processing of pellet feed) occur at elevated temperatures [15]. Compared with fungal laccases, bacterial laccases offer the advantage of better alkali and high-temperature resistance, so that have broader application prospects in the biotechnology [18].

In recent years, the detoxification ability of various enzymes to mycotoxins has been improved mainly by molecular modification. Structure-guided mutagenesis has been used to improve the degradability of zearalenone by different zearalenone hydrolases [19,20]. Furthermore, the catalytic performance of Trametes versicolor AFB1-degrading enzyme was improved by mutating Gln232 to Met232 [21]. Our previous study has reported a CotA-laccase from Bacillus licheniformis ANSB821 (accession no. MN075270). This CotA-laccase can oxidize AFB1 in the absence of redox mediators and exhibits excellent thermostability [8]. However, the ability of CotA-laccase to degrade AFB1 under acidic or neutral conditions is not as high as that under alkaline conditions, which limits the detoxification of AFB1 by CotA-laccase in the gastrointestinal tract of animals. To improve the AFB1 degradation efficiency of CotA-laccase and widen the potential application in degrading AFB1 in food and feed, a combination of structure-based methods and site-directed mutagenesis was used in the present study. Based on this, the mutant enzyme was constructed and compared with the wild-type CotA-laccase according to the kinetic parameters, optimal pH and temperature, as well as detoxification ability to AFB1.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Materials

2,2′-Azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) was purchased from Pribolab (Qingdao, China). Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was obtained from Biotopped (Beijing, China). Ampicillin was from Solarbio (Beijing, China). The plasmid extraction kit and fast mutagenesis system were obtained from Tiangen (Beijing, China). All chemical reagents were standard reagent grade.

2.2. Plasmid, strains, and media

The CotA-laccase gene of B. licheniformis ANSB821 stored in our laboratory was expressed into pET31b provided by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Escherichia coli strain DH5α and BL21 cells were obtained from TransGen Biotech (Beijing, China). All strains were cultivated with Luria-Bertani (LB) medium.

2.3. Bioinformatics analysis

All protein sequences were searched from the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Multiple sequence alignment was performed with Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). Homology modeling was performed with SWISS-MODEL Server (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/). CotA-laccase protein from B. subtilis (PDB code: 1GSK) that showed 66.14 % identity to B. licheniformis laccase was used as the template. The structures of enzymes were analyzed with PyMol viewer. The substrate molecules were docked into the enzyme structure with Software AutoDockTools 1.5.6.

2.4. Construction of mutant

The mutant was constructed by Quik-Change site specific mutagenesis. PCR mixture contained the synthetic primers as Table S1, fastalteration buffer, fastalteration DNA polymerase, RNase-free ddH2O and plasmid pET31b which contained the wild-type CotA-laccase gene. The PCR program consists of pre-heating the reaction mixture at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 18 cycles of denaturation at 94°C (20 s), annealing at 55°C (10 s) and extension at 68°C for 2.5 min with a final extension at 68°C for 5 min. The PCR product was incubated with DpnⅠ restriction enzyme at 37°C for 1 h, and the template plasmid was removed. Finally, the digested product was transformed into E. coli DH5α and sequenced to confirm the mutant. Confirmed gene was then transformed into E. coli BL21 by heat shock transformation method.

2.5. Expression and purification

Expression of CotA-laccase and its mutant was based on our previous work [8]. The recombinant strains were cultured at 37°C in LB medium containing 100 μg mL−1 ampicillin. 0.1 mM IPTG and 2 mM CuSO4 were added to induce the gene expression at an OD600 of 0.6 in LB medium. Temperature was reduced to 16°C in a shaking incubator (120 rpm) and cells were incubated for 20 h. Afterwards, cells were harvested by centrifugation (15 min, 8000×g, 4°C) and the pellets were resuspended in binding buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, pH 7.4). The cells were disrupted by sonification on ice and the cell debris was removed by centrifugation (10 min, 12,000×g, 4°C).

The proteins in supernatant were then purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography column (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA, USA) as described previously [8]. The His-tags of both wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A were not removed in this study. Purity of the proteins was confirmed by 12 % sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Then the collected proteins were concentrated by ultrafiltration (molecular weight cutoff of 30 kDa) and quantified using a Bradford Protein Assay Kit (TransGen, China).

2.6. Enzyme activity assay

The kinetic parameters of purified laccases were measured at 37°C with ABTS as substrate. The reaction mixture (3 mL total volume) contained 2.0 μg mL−1 CotA-laccase, 100 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5), and various amounts of ABTS (5–1000 μM). The ultraviolet absorbance of ABTS was 420 nm (ɛ = 36,000 M−1cm−1) [22]. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as 1 μmol of substrate oxidized by how many amounts of enzyme per minute. Kinetic parameters were fitted by nonlinear Michaelis-Menten plots with Graphpad Prism 8.0 (SanDiego, CA, USA). All assays were performed at least in triplicate.

2.7. Optimum pH and pH stability

The optimum pH of wild-type CotA-laccase and the mutant was measured with ABTS as substrate. The reaction mixture (3 mL total volume) contained 2.0 μg mL−1 CotA-laccase, 100 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5), and 1 mM ABTS. The reaction was run at 37°C for 30 s, and the enzyme activities were spectrophotometrically determined at 420 nm. The pH stability of wild-type CotA-laccase and the mutant was assayed by overnight incubation at 4°C and different pH values (pH 3.0–12.0), and then residual activity was measured. The remaining enzyme activity was determined at 37°C and pH 4.5 with ABTS as substrate. All assays were done at least in triplicate.

2.8. Optimum temperature and thermal stability

The optimum temperature of wild-type CotA-laccase and the mutant was measured with ABTS as substrate. The reaction mixture (3 mL total volume) contained 2.0 μg mL−1 CotA-laccase, 100 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5), and 1 mM ABTS. The reaction solutions were maintained at different temperatures (30-100°C) for 30 s, and the enzyme activities were spectrophotometrically determined at 420 nm. The thermal stability was determined by incubating enzymes in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) at 50, 70 and 90°C, and then the residual activity was measured. The remaining enzyme activity was determined at 37°C and pH 4.5 with ABTS as substrate. All measurements were performed at least in triplicate.

2.9. Aflatoxin oxidase properties

All AFB1 oxidation assays were performed in the 2 mL centrifuge tubes with a reaction volume of 500 μL, containing 20 μg mL−1 of CotA and 2.0 μg mL−1 of AFB1. The effect of pH on AFB1 oxidation by wild-type CotA-laccase and the mutant was determined at pH 5.0–9.0 and 37°C for 12 h. The effect of temperature on AFB1 oxidation was determined in the range of 30–80°C and pH 8.0 for 30 min. The effect of metal ions on CotA-mediated oxidation of AFB1 was determined. The wild-type CotA-laccase and the mutant (100 μg mL−1) were pre-incubated with 10 mM metal ions at 37°C and pH 8.0 for 10 min. Then AFB1 was added and the mixture reacted at 37°C for 30 min. The control was prepared in the absence of the enzymes. The reaction was terminated by adding 500 μL HPLC-grade methanol. The assays were measured at 37°C and pH 8.0 using different concentrations (1–100 μg mL−1) of AFB1 as substrates when calculated the kinetic parameters [8]. The initial reaction rate was measured by monitoring the reduction of AFB1 every 6 min intervals for a total of 30 min. Kinetic parameters were calculated by nonlinear Michaelis-Menten plots with Graphpad Prism 8.0 (SanDiego, CA, USA). All assays were performed at least in triplicate. The degradation rate of AFB1 was calculated as the following equation: DR = (1 - CT/CC) × 100 %, where DR was the degradation rate; CT and CC were the concentration of AFB1 in the experimental group and the control group, respectively.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed by GraphPad Prism 8.3 software (GraphPad Software, USA). Data were shown as the averages ± standard deviation of three parallel experiments. Two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test was used for comparison between two groups and one-way ANOVA followed Tukey's t-test was used for comparison between multiple groups. P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Structural model of B. licheniformis CotA-laccase

The combination technique of structure-based approaches and site-directed mutagenesis was used for purpose of enhancing the catalytic activity of CotA-laccase. In this experiment, the 3D structure of B. licheniformis ANSB821 CotA-laccase was obtained by homology modeling. Hence, it has been assumed that the generated model could stand for the structure of CotA-laccase from B. licheniformis. Laccases were members of the multicopper oxidase family with three copper centers [23]. Laccases were reported to be able to utilize a wide range of substrates [24]. There were three cupredoxin-like domains in structure of CotA-laccase, and four copper atoms existed in the form of type-1, type-2 and type-3 copper centers [25]. The catalytic mechanism of laccase includes oxidation of the substrate on type-1 Cu site and reduction of O2 to H2O on type-2/3 Cu cluster [26]. Shown here, Gln441 of B. licheniformis CotA-laccase was located in the α-helix fragment of domain 3, which was the entrance of substrate-binding pocket (Fig. 1). It was surmised that the different conformation of this site may affect the activity of laccase.

Fig. 1.

The modeled 3D structure of B. licheniformis CotA-laccase. This molecular structure is comprised of three domains, and four copper atoms are classified into three types which are marked with different colors. The position of Gln441 and its hydrogen bonding interaction with Ile437 are highlighted as the close-up view.

3.2. Mutation design, cloning and expression

Site-directed mutagenesis has so far been an important method to improve the enzyme activity. In a previous study, the mutant Q442A of B. pumilus W3 screened from the saturation mutagenesis library showed 2.45-fold higher catalytic efficiency on ABTS than the wild-type CotA-laccase [27]. Moreover, the Reactive Black 5 decolorization activity was improved by site-saturation mutagenesis. The potential mutation site of CotA-laccase, Gln442, plays an important role in changing the affinity of substrate [28]. According to the sequence alignment of amino acid residues of B. licheniformis ANSB821 and B. pumilus W3 CotA-laccase, Gln441 in B. licheniformis laccase was equivalent to Gln442 in B. pumilus laccase (Fig. S1). Therefore, it was hypothesized that the catalytic activity of the CotA-laccase in our present study for ABTS and the degradation ratio for AFB1 could be improved by replacing Gln441 with Ala441. In order to study the possible effect of single amino acid replacement on the catalytic activity of B. licheniformis CotA-laccase, mutation Q441A was successfully introduced into the CotA-laccase gene of B. licheniformis. In our previous study, plasmid containing the gene of CotA-laccase of B. licheniformis ANSB821 has been introduced into E. coli. In this study, both the wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A mutant were cloned and expressed in E. coli.

3.3. Purification and characterization of wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A mutant

The recombinant wild-type CotA-laccase and its variant were purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography column as described previously [8]. The two purified enzymes molecular weight were ∼60 kDa (Fig. S2). To study the enzymatic properties of these two enzymes, ABTS was used as the substrate. The kcat and Km values of wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A mutant to ABTS were listed in Table 1. The kcat/Km value of Q441A was determined to be 392.07 s−1 mM−1, which was about 2.02-folds higher than the 194.09 s−1 mM−1 of wild-type laccase.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for the wild-type CotA and Q441A using ABTS as substrate.

| Laccase | Km (mM)a | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (s−1 mM−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 0.079 ± 0.005 | 15.36 ± 2.41 | 194.09 |

| Q441A | 0.052 ± 0.003 | 20.48 ± 2.18 | 392.07 |

Laccase activity was calculated at 37°C with 100 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5). ABTS was chosen as substrate. Km and kcat were determined by Michaelis-Menten equation.

3.4. Effect of pH on enzyme activity and stability

In this study, the optimal pH value of both wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A were 4.5 with ABTS as substrate (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the catalytic activity at 2.5 and 3.0 were higher for Q441A compared with the wild-type CotA-laccase. Stability studies of pH indicated that the wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A were especially stable in a neutral and alkaline environment (Fig. 2B). The wild-type CotA-laccase was most stable at pH 8.0, and Q441A was most stable at pH 9.0. The wild-type CotA-laccase maintained 22 % residual activity after overnight incubation at pH 3.0 compared to pH 8.0. Similarly, Q441A maintained 21 % residual activity after overnight incubation at pH 3.0 compared to pH 9.0. The pH stability of Q441A had no distinct difference with that of the wild-type at acidic pHs. However, the activity of Q441A after overnight incubation at pH 9.0 was about 1.57-folds higher than the activity of wild-type CotA-laccase after overnight incubation at pH 8.0. Therefore, although the stability of Q441A and wild-type CotA-laccase was similar, the residual activity of Q441A was higher than that of wild-type CotA-laccase after overnight incubation at each pH.

Fig. 2.

Effect of pH on the activity (A) and stability (B) of the purified wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A at 37°C using ABTS as substrate. (A) The test on enzyme activity was conducted at pH 2.0–8.0, whereas (B) the test on stability involved the incubation of the purified CotA for overnight at 4°C and pH 3.0–12.0 before measurement of residual activity.

3.5. Effect of temperature on enzyme activity and stability

The wild-type CotA-laccase had the optimal reaction temperature at 80°C with ABTS as substrate. The Q441A held the optimal temperature at 90°C (Fig. 3A). As for the thermostability of the two CotA-laccases, it demonstrated a higher thermostability at 50°C and 70°C for Q441A (Fig. 3B–D). Furthermore, both the two enzymes were stable at 50°C for maintaining more than 60 % activity after incubated for 5 h.

Fig. 3.

Effect of temperature on the activity (A) and stability (B–D) of the purified wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A using ABTS as substrate at pH 4.5. (A) Laccase activity was measured at different temperatures (30-100°C). The thermostability of the wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A were measured after incubation at different temperatures 50°C (B), 70°C (C), and 90°C (D), respectively.

3.6. Catalytic efficiency of aflatoxin B1 by wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A mutant

The application of CotA-laccase from B. licheniformis ANSB821 in AFB1 detoxification has been reported [8]. In this study, the catalytic efficiency of AFB1 by purified wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A were compared. As shown in Table 2, the purified Q441A mutant exhibited higher kcat/Km value on AFB1 than the wild-type CotA-laccase (1.73-fold). This was attributed to the decrease in Km and the slightly increase in kcat for the Q441A mutant. The effects of pH and temperature on the oxidation activity of wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A with AFB1 as substrate were shown in Fig. 4. Compared with the wild-type CotA-laccase, the degradation of AFB1 by Q441A increased in the pH range from 5.0 to 9.0. The AFB1 degradation ratio by Q441A was more than 97 % in the pH range from 7.0 to 9.0, whereas, the maximal AFB1 degradation rate by wild-type CotA-laccase reached up to 91 % only at pH 8.0. The results showed that compared with the wild-type laccase, the AFB1 degradation rate of Q441A was improved under acid, neutral and alkaline conditions. The optimal temperature for Q441A to degrade AFB1 was 70°C, which was the same as wild-type laccase, and the degradation of AFB1 by Q441A increased in the range of 30–80°C. In addition, the AFB1 degradation rate of Q441A was higher than that of the wild-type laccase significantly at 30, 40, 60, 70, and 80°C. The effect of metal ions (10 mM) on the activity of wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A towards AFB1 was shown in Table 3. Among the seven metal ions, Cu2+, Mg2+ and Na+ had little effect on the activity of laccases towards AFB1. The significant inhibitory effect of Ca2+, Co2+, Zn2+ and Mn2+ were obvious.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters for the wild-type CotA and Q441A using AFB1 as substrate.

| Laccase | Km (mM)a | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (s−1 mM−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 0.131 ± 0.004 | 0.054 ± 0.008 | 0.412 |

| Q441A | 0.084 ± 0.002 | 0.060 ± 0.005 | 0.714 |

Laccase activity was calculated at 37°C with 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0). AFB1 was chosen as substrate. Km and kcat were determined by Michaelis-Menten equation.

Fig. 4.

Effect of pH (A) and temperature (B) on the activity of the purified wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A using AFB1 as substrate.

Table 3.

Effect of metal ions on activity of wild-type CotA and Q441A using AFB1 as substrate.

| Metal ion (10 mM) | Residual activity (%) |

SEM | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Q441A | |||

| – | 100a | 100a | – | – |

| Cu2+ | 78.31 ± 11.88bc | 86.19 ± 6.53ab | 9.581 | 0.457 |

| Mg2+ | 88.29 ± 8.46ab | 102.20 ± 1.64a | 6.092 | 0.085 |

| Ca2+ | 70.92 ± 7.41bc | 76.16 ± 6.16bc | 6.817 | 0.484 |

| Co2+ | 69.89 ± 4.94bc | 68.06 ± 12.73c | 9.656 | 0.859 |

| Zn2+ | 30.03 ± 2.30Bd | 40.99 ± 3.13Ad | 2.750 | 0.016 |

| Mn2+ | 60.40 ± 2.73c | 61.12 ± 2.57c | 2.652 | 0.798 |

| Na+ | 86.87 ± 1.70Bab | 97.13 ± 0.47Aa | 1.249 | 0.001 |

| SEM | 4.368 | 4.370 | ||

| P-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

A, B Different letters indicate significant different (P < 0.05) between WT and Q441A.

a-d Different letters indicate significant different (P < 0.05) among various metal ions.

4. Discussion

The selection of mutation site is a key point in site-directed mutagenesis. Current researches on site-directed mutagenesis of laccase were mostly about the changes of amino acid residues near different copper ion centers [29]. It has long been clearly recognized that mutagenesis of amino acid residues near the active center played an important role in the enhanced activity of enzymes [30]. Nevertheless, the hydrophobic interactions of amino acid residues around the active centre are important for the thermal stability of enzymes, so that the introduction of mutations around the active centre in order to improve the catalytic efficiency was possible to reduce the thermal stability of the enzymes [31]. Considering the poor thermal stability that may result from the mutation of amino acid around the active center of enzymes, we avoided the introduction of mutations near the active site, but concentrated on residues at the entrance to the substrate-binding pocket.

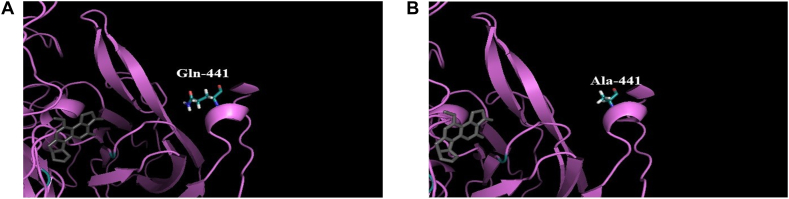

In our present study, a combination of structure-based methods and site-directed mutagenesis was used to improve the detoxification ability of CotA-laccase on AFB1. It was found that Gln441 was located in a short α-helix fragment of the entrance of substrate-binding pocket. It had been mentioned that the change of amino acids located at the entrance of the substrate-binding pocket may reduce the steric hindrance, so that the substrate was easy to enter the tunnel and dock into the active site of the enzyme [27]. The local structures of the wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A were further compared (Fig. 5). Both Gln441 and Ala441 could form a hydrogen bond with Ile437 according to the structural characteristics of the α-helix. However, it was apparent that the side chain of Ala441 became shorter than that of Gln441 after site-directed mutagenesis. It could be speculated that maybe Gln441 had more steric effects with the substrates than Ala441. The shorter side chain of Ala441 in the mutant contributed to the decreased steric effects, so that the substrates were more likely to bind to the active site of CotA-laccase (Fig. 5). Beyond that, the result of molecular docking showed that the mutation of Gln441 had no significant effect on the number and location of hydrogen bonds formed between AFB1 and the active center of CotA-laccase, so that the enzyme would not be inactivated by this kind of mutagenesis (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Partial structure of wild-type CotA-laccase (A) and Q441A mutant (B). Wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A are generated using PyMol viewer. Residue 441 is labeled and shown as colored stick, and AFB1 is displayed as grey stick.

Fig. 6.

Interactions of AFB1 with the wild-type CotA-laccase (A) and Q441A (B). The yellow structure indicates AFB1, and the green structure represents the amino acid residues around AFB1. Hydrogen bonds are shown as the green or yellow dashes.

The result showed that compared with wild-type CotA-laccase, the Km value of Q441A to ABTS and AFB1 decreased by 1.52-fold and 1.56-fold, respectively, which indicated that the affinity of Q441A to substrates including ABTS and AFB1 was improved. The kcat/Km value of Q441A to ABTS and AFB1 were determined to be 392.07 and 0.714 s−1 mM−1 which achieved 2.02 and 1.73-fold higher catalytic efficiency than that of the wild-type, respectively. Hence, it was speculated that amino acid at 441 was in an important position. When Gln441 was mutated to Ala441, the side chain became shorter and the steric hindrance decreased. Therefore, it was easy to allow the substrate to dock into the active site. The higher catalytic efficiency of Q441A for ABTS in our study was in agreement with the previous study, where Gln442 of B. pumilus CotA-laccase was turned into Ala442 and exhibited higher catalytic efficiency on ABTS [27]. In another research, remodeling of the substrate-binding site in the small laccase created a cavity and improved the access of substrates to the type-1 Cu site [32].

The optimal pH value of the mutant Q441A for ABTS was about 4.5, which was same to the wild-type CotA laccase. This optimal pH value was not significantly different from the optimal pH 4.0 of the Streptomyces griseoflavus Ac-993 laccase [33] and pH 4.4 of the B. subtilis LS03 laccase [34]. The wild-type CotA-laccase had the optimal reaction temperature at 80°C with ABTS as substrate, while the mutant Q441A held the optimal temperature at 90°C. Both of the optimal temperatures of wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A to oxidize ABTS were higher than that of Lac2 from Pleurotus pulmonarius with 55°C [17], which indicated that maybe the optimal temperature of bacterial laccase for oxidation ABTS was higher than that of fungal laccase.

This study showed that the oxidation of AFB1 by CotA-laccase was enhanced remarkably after site-directed mutagenesis in a large range of pH and temperature conditions. The feed enzymes are able to used as feed additives, or they can be applied in feed processing to detoxify mycotoxins in feed directly. However, the use of enzymes to degrade mycotoxins in large-scale feed processing is time-consuming and expensive. Therefore, most of the feed enzymes on the market are used as feed additives to play a role in gastrointestinal tract of animals. As is known, the normal pH value of gastrointestinal tract of livestock is almost between 3.0 and 7.0 [[35], [36], [37]]. Q441A showed better catalytic activity than wild-type CotA-laccase using AFB1 as substrate under acidic or neutral conditions, especially at pH 7.0, showing that this mutant could play a more important role in the degradation of AFB1 in the gastrointestinal tract of animals. Since the CotA-laccase from B. licheniformis is a thermo-alkali stable enzyme, the stability of the wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A were investigated. The mutant CotA-laccase was more stable at pH 9.0, therefore, Q441A had better ability to resistant strongly alkaline environments.

The degradation ratio of both wild-type CotA-laccase and Q441A to AFB1 was the highest at 70°C. The similar phenomenon was observed in the CotA-laccase from B. licheniformis ZOM-1 [38]. In addition, the optimal temperature of CotA-laccases in our study and that of CotA-laccase from B. licheniformis ZOM-1 to degrade AFB1 were higher than that of fungal laccases [21]. AFB1 degradability improved with the increasing temperature from 30 to 70°C was possibly related to the activation of the laccase molecules and the enhancement of the coordination of copper ions [39]. Q441A showed a relatively higher thermostability than CotA-laccase and could meet the technological requirements of feed processing [40]. Gln441 was located on the surface of CotA-laccase. The exposed Gln was prone to deamination at high temperature and not conducive to protein stability [41]. It was reported that the molecule surface hydrophobicity of mutant laccase was enhanced when Gln441 turned into Ala441 so that it would be more suitable for high temperature catalytic reaction [27].

It is of great significance to study the influence of metal ions on laccase because there are many kinds of metal ions in the environment. In this study, Zn2+ significantly inhibited the activity of laccase. The phenomenon was also observed in other kinds of laccases [8,42]. This was perhaps due to the interaction between metal ions and laccase electron transport system [42]. Moreover, the residual activity of laccase was over 60 % with other metal ions (Cu2+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Co2+, Mn2+, Na+) supplementation. The interesting thing was that the activity of Q441A was higher than the wild-type laccase significantly by the addition of Zn2+ and Na+. This indicated that this mutant could play a good role in the presence of heavy metals.

We obtained a CotA-laccase mutant Q441A with improved AFB1 detoxification in this study. However, this study has potential limitations. It is uncertain whether CotA laccase can degrade other nutrients in gastrointestinal tract of animals when used as a feed additive, and whether CotA laccase can maintain the original activity in the presence of various digestive enzymes such as trypsin and pepsin in the gastrointestinal, because these digestive enzymes may degrade CotA laccase. In the future, we plan to evaluate the application value of CotA laccase by animal feeding experiments.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study obtained a CotA-laccase mutant Q441A with improved degradability of AFB1. Q441A mutant present good pH stability, thermostability and high catalytic efficiency to AFB1. Further studies are needed to evaluate the performance of Q441A in degrading AFB1 as feed additive.

Ethics statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments of comparable ethical standards. The purchase, storage and use of poisonous and harmful materials in this experiment were performed in compliance with the relevant laws and institutional guidelines of China. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Data availability statement

The data associated with our study have not been deposited in a publicly available repository. Data will be made available on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yanrong Liu: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Yongpeng Guo: Methodology, Data curation. Limeng Liu: Methodology, Formal analysis. Yu Tang: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Yanan Wang: Formal analysis. Qiugang Ma: Supervision. Lihong Zhao: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments and funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Program No. 2021YFC2103003), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Program No. 31972604), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Program No. 2023M730998).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22388.

Contributor Information

Yanrong Liu, Email: 15110578158@163.com.

Yongpeng Guo, Email: 18771951786@163.com.

Limeng Liu, Email: Liulimeng_9@163.com.

Yu Tang, Email: m17801115235@163.com.

Yanan Wang, Email: wyn17600596712@163.com.

Qiugang Ma, Email: maqiugang@cau.edu.cn.

Lihong Zhao, Email: zhaolihongcau@cau.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

figs1.

figs2.

References

- 1.Snyder A.B., Worobo R.W. Fungal spoilage in food processing. J. Food Protect. 2018;81(6):1035–1040. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-18-031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nesic K., Habschied K., Mastanjevic K. Modified mycotoxins and multitoxin contamination of food and feed as major analytical challenges. Toxins. 2023;15(8):511. doi: 10.3390/toxins15080511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khalil O.A.A., Hammad A.A., Sebaei A.S. Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus ochraceus inhibition and reduction of aflatoxins and ochratoxin A in maize by irradiation. Toxicon. 2021;198:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2021.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo Y.P., Zhao L.H., Ma Q.G., Ji C. Novel strategies for degradation of aflatoxins in food and feed: a review. Food Res. Int. 2021;140 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adedara I.A., Atanda O.E., Monteiro C.S., Rosemberg D.B., Aschner M., Farombi E.O., Rocha J.B.T., Furian A.F., Emanuelli T. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of aflatoxin B1-mediated neurotoxicity: the therapeutic role of natural bioactive compounds. Environ. Res. 2023;237(1) doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.116869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adegoke T.V., Yang B.L., Tian X.Y., Yang S., Gao Y., Ma J.N., Wang G., Si P.D., Li R.Y., Xing F.G. Simultaneous degradation of aflatoxin B1 and zearalenone by Porin and Peroxiredoxin enzymes cloned from Acinetobacter nosocomialis Y1. J. Hazard Mater. 2023;459 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.132105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai M.Y., Qian Y.Y., Chen N., Ling T.J., Wang J.J., Jiang H., Wang X., Qi K.Z., Zhou Y. Detoxification of aflatoxin B1 by Stenotrophomonas sp. CW117 and characterization the thermophilic degradation process. Environ. Pollut. 2020;261 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo Y.P., Qin X.J., Tang Y., Ma Q.G., Zhang J.Y., Zhao L.H. CotA laccase, a novel aflatoxin oxidase from Bacillus licheniformis, transforms aflatoxin B1 to aflatoxin Q1 and epi-aflatoxin Q1. Food Chem. 2020;325 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Datta S., Veena R., Samuel M.S., Selvarajan E. Immobilization of laccases and applications for the detection and remediation of pollutants: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021;19(1):521–538. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01081-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahn V. Potential of the enzyme laccase for the synthesis and derivatization of antimicrobial compounds. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023;39(4):107. doi: 10.1007/s11274-023-03539-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bai Y.S., Ali S., Liu S., Zhou J.J., Tang Y.L. Characterization of plant laccase genes and their functions. Gene. 2023;852 doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2022.147060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balabanidou V., Grigoraki L., Vontas J. Insect cuticle: a critical determinant of insecticide resistance. Current Opinion in Insect Science. 2018;27:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang F., Xu L., Zhao L.T., Ding Z.Y., Ma H.L., Terry N. Fungal laccase production from lignocellulosic agricultural wastes by solid-state fermentation: a review. Microorganisms. 2019;7(12):665. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7120665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwal N., Solanki V.S., Gacem A., Hasan M.A., Pare B., Srivastava A., Singh A., Yadav V.K., Yadav K.K., Lee C., Lee W., Chaiprapat S., Jeon B.H. Bacterial laccases as biocatalysts for the remediation of environmental toxic pollutants: a green and eco-friendly approach- A review. Water. 2022;14(24):4068. doi: 10.3390/w14244068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khatami S.H., Vakili O., Movahedpour A., Ghesmati Z., Ghasemi H., Taheri-Anganeh M. Laccase: various types and applications. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2022;69(6):2658–2672. doi: 10.1002/bab.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeinvand-Lorestani H., Sabzevari O., Setayesh N., Amini M., Nili-Ahmadabadi A., Faramarzi M.A. Comparative study of in vitro prooxidative properties and genotoxicity induced by aflatoxin B1 and its laccase-mediated detoxification products. Chemosphere. 2015;135:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song Y.Y., Wang Y.A., Guo Y.P., Qiao Y.Y., Ma Q.G., Ji C., Zhao L.H. Degradation of zearalenone and aflatoxin B1 by Lac2 from Pleurotus pulmonarius in the presence of mediators. Toxicon. 2021;201:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2021.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y., Lin D.F., Hao J., Zhao Z.H., Zhang Y.J. The crucial role of bacterial laccases in the bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020;36(8):116. doi: 10.1007/s11274-020-02888-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang M.X., Yin L.F., Hu H.Z., Selvaraj J.N., Zhou Y.L., Zhang G.M. Expression, functional analysis and mutation of a novel neutral zearalenone-degrading enzyme. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2018;118(Pt A):1284–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.06.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu X.R., Tu T., Luo H.Y., Huang H.Q., Su X.Y., Wang Y., Wang Y.R., Zhang J., Bai Y.G., Yao B. Biochemical characterization and mutational analysis of a lactone hydrolase from Phialophora americana. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020;68(8):2570–2577. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b05853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang P.Z., Lu S.H., Xiao W., Zheng Z., Jiang S.W., Jiang S.T., Jiang S.Y., Cheng J.S., Zhang D.F. Activity enhancement of Trametes versicolor aflatoxin B1-degrading enzyme (TV-AFB1D) by molecular docking and site-directed mutagenesis techniques. Food Bioprod. Process. 2021;129:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2021.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nasoohi N., Khajeh K., Mohammadian M., Ranjbar B. Enhancement of catalysis and functional expression of a bacterial laccase by single amino acid replacement. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013;60:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta N., Lee F.S., Farinas E.T. Laboratory evolution of laccase for substrate specificity. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2010;62(3–4):230–234. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2009.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu F. Oxidation of phenols, anilines, and benzenethiols by fungal laccases: correlation between activity and redox potentials as well as halide inhibition. Biochemistry. 1996;35(23):7608–7614. doi: 10.1021/bi952971a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khodakarami A., Goodarzi N., Hoseinzadehdehkordi M., Amani F., Khodaverdian S., Khajeh K., Ghazi F., Ranjbar B., Amanlou M., Dabirmanesh B. Rational design toward developing a more efficient laccase: catalytic efficiency and selectivity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;112:775–779. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mot A.C., Silaghi-Dumitrescu R. Laccases: complex architectures for one-electron oxidations. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2012;77(12):1395–1407. doi: 10.1134/S0006297912120085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma H., Xu K.Z., Wang Y.J., Yan N., Liao X.R., Guan Z.B. Enhancing the decolorization activity of Bacillus pumilus W3 CotA-laccase to Reactive Black 5 by site-saturation mutagenesis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020;104(21):9193–9204. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-10897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durao P., Bento I., Fernandes A., Melo E., Lindley P., Martins L. Perturbations of the T1 copper site in the CotA laccase from Bacillus subtilis: structural, biochemical, enzymatic and stability studies. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2006;11(4):514–526. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu Y.Y., Zhang Y., Zhan J.B., Lin Y., Yang X.R. Axial bonds at the T1 Cu site of Thermusthermophilus SG0.5JP17-16 laccase influence enzymatic properties. FEBS Open Bio. 2019;9(5):986–995. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monza E., Lucas M.F., Camarero S., Alejaldre L.C., Martinez A.T., Guallar V. Insights into laccase engineering from molecular simulations: toward a binding-focused strategy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015;6(8):1447–1453. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y., Luo Q., Zhou W., Xie Z., Cai Y.J., Liao X.R., Guan Z.B. Improving the catalytic efficiency of Bacillus pumilus CotA-laccase by site-directed mutagenesis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016;101(5):1935–1944. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7962-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toscano M.D., De Maria L., Lobedanz S., Ostergaard L.H. Optimization of a small laccase by active-site redesign. Chembiochem. 2013;14(10):1209–1211. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolyadenko I., Scherbakova A., Kovalev K., Gabdulkhakov A., Tishchenko S. Engineering the catalytic properties of two-domain laccase from Streptomyces griseoflavus Ac-993. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23(1):65. doi: 10.3390/ijms23010065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ouyang F.J., Zhao M. Enhanced catalytic efficiency of CotA-laccase by DNA shuffling. Bioengineered. 2019;10(1):182–189. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2019.1621134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamidifard M., Khalaji S., Hedayati M., Sharifabadi H.R. Use of condensed fermented corn extractives (liquid steep liquor) as a potential alternative for organic acids and probiotics in broiler ration. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2023;22(1):418–429. doi: 10.1080/1828051X.2023.2206420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y.R., Du H.S., Wu Z.Z., Wang C., Liu Q., Guo G., Huo W.J., Zhang Y.L., Pei C.X., Zhang S.L. Branched-chain volatile fatty acids and folic acid accelerated the growth of Holstein dairy calves by stimulating nutrient digestion and rumen metabolism. Animal. 2020;14(6):1176–1183. doi: 10.1017/S1751731119002969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Risley C.R., Kornegay E.T., Lindemann M.D., Wood C.M., Eigel W.N. Effect of feeding organic acids on selected intestinal content measurements at varying times postweaning in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 1992;70(1):196–206. doi: 10.2527/1992.701196x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun F., Yu D.Z., Zhou H.Y., Lin H.K., Yan Z., Wu A.B. CotA laccase from Bacillus licheniformis ZOM-1 effectively degrades zearalenone, aflatoxin B1 and alternariol. Food Control. 2023;145 doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2022.109472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar S., Jain K.K., Rani S., Bhardwaj K.N., Goel M., Kuhad R.C. In-vitro refolding and characterization of recombinant laccase (CotA) from Bacillus pumilus MK001 and its potential for phenolics degradation. Mol. Biotechnol. 2016;58(12):789–800. doi: 10.1007/s12033-016-9978-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoder A.D., Stark C.R., Tokach M.D., Jones C.K. Effects of pellet processing parameters on pellet quality and nursery pig growth performance. Transactions of the Asabe. 2019;62(2):439–446. doi: 10.13031/trans.12987. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaneko H., Minagawa H., Shimada J. Rational design of thermostable lactate oxidase by analyzing quaternary structure and prevention of deamidation. Biotechnol. Lett. 2005;27(22):1777–1784. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-3555-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Si W., Wu Z.W., Wang L.L., Yang M.M., Zhao X. Enzymological characterization of Atm, the first laccase from Agrobacterium sp. S5-1, with the ability to enhance in vitro digestibility of maize straw. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data associated with our study have not been deposited in a publicly available repository. Data will be made available on request.