Abstract

Medicaid is a major insurer of autistic people. However, during the transition to adulthood, autistic individuals are more likely than people with intellectual disability to lose their Medicaid benefits. Individuals with intellectual disability may have greater success maintaining Medicaid coverage during this time because most states provide coverage to individuals with intellectual disability throughout adulthood, which is not the case for autism. Using national Medicaid data from 2008 to 2016, we estimated the probability of intellectual disability diagnosis accrual among autistic Medicaid beneficiaries. Medicaid beneficiaries ages 8 to 25 with 1+ inpatient or 2+ outpatient autism spectrum disorder claims, but no intellectual disability claim, in a 12-month eligibility period were included. We used a person-month discrete-time proportional hazards model. Disruptions in Medicaid coverage were operationalized as 2+ consecutive months of no coverage before coverage resumed (yes/no). One in five autistic individuals ages 8–25 accrued an intellectual disability diagnosis. The probability of accruing an intellectual disability diagnosis was higher among autistic individuals who had disruptions in Medicaid coverage compared to those without disruptions, and peaked at age 21 (during the transition to adulthood). Expanding Medicaid to cover autistic people of all ages could decrease the need for intellectual disability diagnosis accrual and improve health outcomes for autistic adults.

Keywords: Adolescents, Autism spectrum disorders, Policy, Health Services

Introduction

Autistic individuals have lifelong service needs, and healthcare costs several times greater than individuals with other disabilities (Zuvekas et al., 2021), in part because of service barriers (Shattuck et al., 2020). While a growing number of Medicaid programs are available for autistic people, these programs often focus on children, so autistic adults still face barriers to services (Shea et al., 2021). For example, during the transition to adulthood, autistic individuals are more likely than non-autistic peers with intellectual disability (ID) to lose their Medicaid benefits and not re-enroll (Shea et al., 2019; Shea et al., 2022). Providers and advocates have sought ways to improve health insurance coverage for autistic adults. One approach may be for autistic individuals to accrue new diagnoses that they don’t necessarily need services for, but may help meet Medicaid eligibility criteria, such as ID. New ID diagnoses may help autistic youth with coverage disruptions regain --or when accrued proactively, retain -- Medicaid coverage and allow for continued healthcare service access.

In this retrospective cohort study, we examined the probability of ID diagnosis accrual in autistic young people who did not have an ID diagnosis in their first year of Medicaid enrollment. We hypothesized that: 1) autistic individuals who experience disruptions in Medicaid coverage would be more likely to accrue an ID diagnosis because their autism diagnosis was insufficient for retaining Medicaid coverage; and 2) accrued ID diagnoses would be more likely to appear during the transition to adulthood than earlier in life.

Methods

Data were extracted from the 2008–2016 national Medicaid Analytic eXtract and Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System Analytic Files personal summary and service files. Individuals were eligible for inclusion if they had 1+ inpatient or 2+ outpatient claims with an ASD diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] codes 299.xx or ICD-10-CM F84.x) during the first 12 months of enrollment (“eligibility period”; n = 373,864). Autistic beneficiaries with any ID claims (ICD-9-CM codes 317.xx-319.xx or ICD-10-CM F70-F79) during the eligibility period were excluded (n = 308,429; n = 65,435 (21.2%) excluded); we additionally required that individuals have at least one claim for ASD or ID after the eligibility period (n = 244,710).

Individuals were followed beginning after the eligibility period for up to 8 years (96 months). The unit of time, person-months, was measured as the number of months an individual was followed and only counted when the individual was between 8 and 25 years old (n = 192,875). We selected our minimum age criteria (8 years old) because ID etiology suggests that genetic and non-genetic risk factors for ID are present in the prenatal and postnatal periods and present in early life (Boat & Wu, 2015). We were primarily interested in examining accrued ID diagnoses in the context of systems change, and selected the cutoff age (25) to observe some years following termination of IDEA services and child Medicaid waivers (around 21).

Our outcome of interest, ID diagnosis accrual, was measured at the person-month level and identified by the presence of a claim with an ID diagnosis code that occurred after the eligibility period. Our exposure of interest, disruption in Medicaid coverage (yes/no), was a time-varying variable indicating whether there was at least one gap in coverage of 2+ consecutive months before coverage resumed. This threshold (2+ months) is consistent with the literature and more specific than 1+ month, which may include those disenrolled for administrative reasons or temporary changes in income (Shea et al., 2022).

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic and enrollment characteristics and compared between the group who accrued an ID diagnosis and the group who did not using χ2 tests. The probability of ID diagnosis accrual was assessed using a person-month discrete-time proportional hazards model framework. For the outcome, the baseline model specification included main effects for age (categorical), coverage disruption (yes/no), their interaction, and state fixed effects. Adjusted models controlled for sex, race and ethnicity, insurance type, calendar year, and Medicaid eligibility category. Individuals were considered at risk of ID diagnosis accrual after their eligibility period until their first month with an ID claim, they reached age 26, or censoring in the month of December 2016. To ease interpretation, the month-level hazard rates and 95% CIs were converted into annual probabilities of conversion using the formula p = 1 – exp(rt), where p represents the probability, r is the predicted hazard rate, and t equals 12 months (Briggs et al., 2006). Analyses were conducted using Stata version 16.1 (College Station, TX) and R 4.2.0. Statistical tests used a 2-sided α of .05. This study was approved by the Drexel University Institutional Review Board.

Community Involvement

Autistic community members were not involved in the design or development of this study.

Results

There were 36,883 autistic Medicaid beneficiaries who accrued an ID diagnosis between 2008 and 2016, and 155,992 who did not (Table 1). In other words, approximately one in five autistic young people accrued an ID diagnosis between ages 8 and 25. The two groups exhibited differences in insurance eligibility; a lower percentage of those who accrued an ID diagnosis were eligible for Medicaid due to poverty, than in the non-accrual group (9.3% vs 20.6%), while a higher proportion of those who accrued an ID diagnosis were eligible because of disability (81.9% vs 64.3%).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of the 192,875 Medicaid beneficiaries ages 8-25 on the autism spectrum, with or without a new ID diagnosis during 2008–2016

| Accrued ID diagnosis | No ID diagnosis accrual | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 36,883 (19.1%) | N = 155,992 (80.9%) | ||

| Agea (mean, SD) | 12.9 (4.4) | 11.7 (4.4) | <.0001 |

| Disruption (%) | 12.1 | 11.7 | 0.0226 |

| Sexb (%) | <.0001 | ||

| Male | 77.6 | 80.9 | |

| Female | 22.4 | 19.1 | |

| Race and ethnicityb (%) | <.0001 | ||

| Asian/Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 3.2 | 3.0 | |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 0.9 | 1.0 | |

| Black | 16.4 | 11.7 | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 12.9 | 13.7 | |

| Multiracial | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| White | 53.2 | 55.4 | |

| Missing | 12.2 | 14.2 | |

| Medicaid Eligibility Groupb (%) | <.0001 | ||

| Poverty | 9.3 | 20.6 | |

| Disability | 81.9 | 64.3 | |

| Other | 8.7 | 15.0 | |

| Missing | 0.0 | 0.2 | |

| Coverage Typeb,c (%) | <.0001 | ||

| FFS/PCCM Only | 30.5 | 23.1 | |

| Any CMC | 69.5 | 76.9 |

Variable constructed as average age at start of follow-up

Variables for Table 1 are reported at the person-level; we report the most common variable response for each person

FFS, fee-for-service; PCCM, primary care case management; CMC, comprehensive managed care

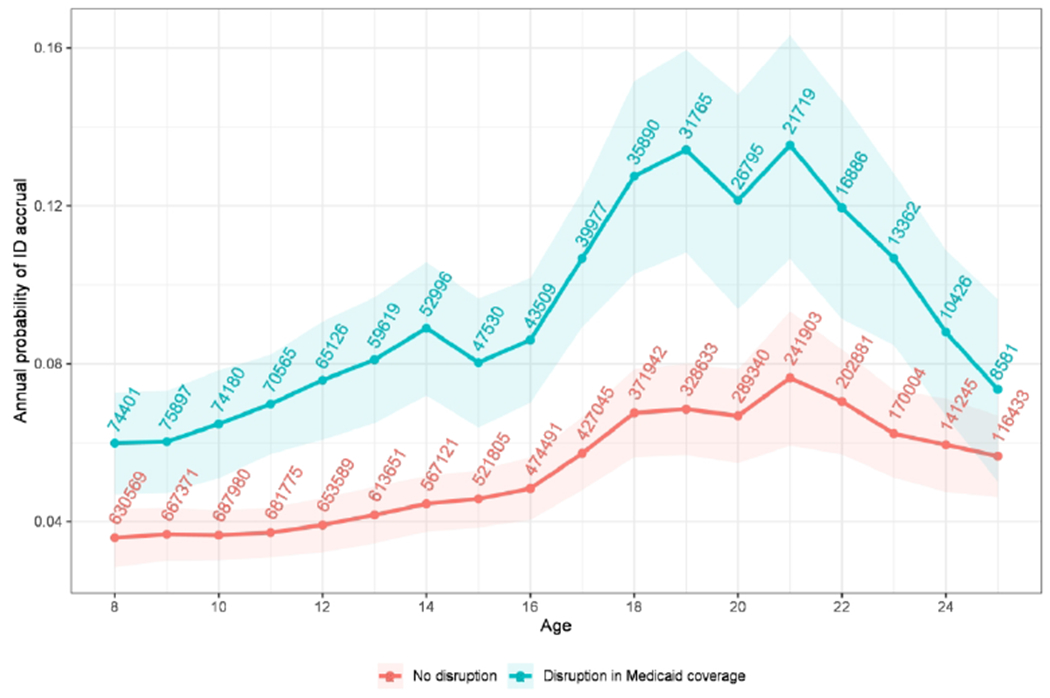

We examined the annual probability of ID diagnosis accrual between ages 8 and 25 years among those who had disruptions in Medicaid coverage (n = 22,629) and those who did not (n = 170,246; Figure 1). Those with disruptions in coverage had a higher probability of accruing an ID diagnosis compared with those without disruptions, across the entire age range. The difference between the groups ranged from under 2 percentage points to nearly 7 percentage points. Both groups saw marked increases in the probability of ID diagnosis accrual after age 16, with the peaks occurring at ages 19 (for those with disruptions) and 21 (for both groups)), reaching maximums of 14% for those with disruptions in coverage and 8% for those without disruptions in coverage. The robustness of results were tested by extending our eligibility period to exclude autistic young people with any ID claims during their first two years of enrollment; results were substantively unchanged.

Figure 1.

Adjusted annual probability of acquiring an ID diagnosis by Medicaid enrollment disruption status among autistic Medicaid beneficiaries during 2008–2016.

Note: Numbers included in Figure 1 represent the total number of person-months in the study at each time point.

Discussion

Among autistic Medicaid beneficiaries who do not have an ID diagnosis identified in their first year of Medicaid enrollment, 19% accrued an ID diagnosis between ages 8 and 25. The probability of ID diagnosis accrual among autistic young people was higher among those with disruptions in Medicaid insurance coverage compared to those without disruptions; for both groups probability of accrued ID diagnosis was highest during the transition to adulthood. This study is the first to our knowledge to examine ID diagnosis accrual among autistic young people.

There are a few mechanisms that may explain the phenomenon of ID diagnosis accrual. The first is that autistic individuals who accrued an ID diagnosis met ID criteria in childhood but weren’t formally diagnosed until later because they didn’t need ID-related services, or stigma. While co-occurrence of ID among the autistic population in Medicaid is common (~25%) (Shea et al., 2022), ID is most often diagnosable in early childhood especially as children enter school cognitive testing is delivered more frequently. Thus, we would expect the number of accrued ID diagnoses after age 8 to be substantially lower than the observed 19%. Further, the American Psychological Association suggests any newly acquired intellectual disability after age 18 should be diagnosed as a neurocognitive disorder or another diagnosis unless there was a traumatic brain injury (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), which is inconsistent with the peaks of ID accrual at ages 19 and 21 observed in this study.

The second explanation is that individuals in our sample were diagnosed with ID as a mechanism for retaining or regaining Medicaid coverage not afforded to individuals with ASD alone. Prior research by Shea and colleagues (2022) supports this hypothesis; they observed autistic Medicaid enrollees with ID had half the probability of Medicaid disenrollment compared to those with ASD alone. Given individuals with ID have frequent interactions with the healthcare system (Shea et al., 2018), we expect our eligibility criteria of least 1+ claim in a 12-month period to be appropriate for identifying ID; sensitivity analyses supported robustness of these findings. Because of their established advocacy history people with ID are often more likely to be Medicaid-eligible than autistic people (Rizzolo et al., 2013). While the addition of an ID diagnosis among autistic people may help maintain Medicaid enrollment, it also could lead to autistic individuals not receiving autism-specific or appropriate healthcare if access is limited to ID-specific services (Shea et al., 2021). Although outpatient behavioral health services are the typical intervention modality recommended for both ASD and ID (Lloyd & Kennedy, 2014), the cognitive deficits observed in ID differ from the social and communication challenges observed in ASD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

In this study, we observed a higher probability of ID accrual among those who experienced disruptions in Medicaid coverage, compared to those who did not. States largely use 1915(c) waivers to enroll autistic individuals in Medicaid. However, Shea and colleagues (2021) examined waivers through 2015 and found: 1) few US states have ASD-specific waivers without ID diagnosis requirements and; 2) most ASD-specific waivers only cover children ages 0 through 10 years. Cumulatively, this suggests that changes to waivers that ensure adequate coverage for autistic people without co-occurring ID and ensure continuity in waivers across the lifespan could be an effective approach to mitigate these disruptions to Medicaid coverage.

The greatest probability of ID diagnosis accrual among our sample occurred between ages 19 (for those with disruptions) and 21 (for both groups), which coincides with when autistic young adults are reassessed for Medicaid eligibility as an individual rather than a family (age 19), and when most states terminate supports education system supports (age 21), and disenrollment peaks observed in prior studies (Carey et al., 2023; Shea et al., 2022). Threats to continuous healthcare coverage among those in need of services and supports have significant downstream consequences and may contribute to increased levels of unmet health needs among autistic adults (Turcotte et al., 2016). Given Medicaid is a critical safety net insurer and the lifelong needs of autistic individuals, policies aimed at ensuring Medicaid coverage across the lifespan are essential to meet these unmet healthcare-related needs for autistic people.

Several study limitations should be noted, in keeping with our use of claims data, which were not collected for research purposes. First, accrued diagnosis of ID during the study period was determined via a specific diagnostic code for ID rather than diagnostic criteria. Second, we were unable to identify the specific reasons behind disruptions in Medicaid coverage experienced by our sample and interpreted disruptions in Medicaid coverage as disruptions in insurance coverage overall; some individuals could have gained another source of coverage (e.g., commercial insurance), although documented employment rates among autistic individuals are low (Ohl et al., 2017). These limitations could lead to misclassification, which could bias our estimates in either direction. Finally, as our data end in 2016, they may not reflect current practice, limiting the generalizability of our results. However, given the limited changes to Medicaid waivers in the last 7 years, we anticipate similar practices.

Accrual of an ID diagnosis among autistic young people is common and more likely among individuals with disruptions in Medicaid coverage. Some providers may perceive benefits of diagnosing ID among autistic patients to improve access to comprehensive healthcare through continuous insurance coverage. The literature on this topic is quite limited, and more research is needed to elucidate factors that impact diagnostic practices. Expanding Medicaid waivers, which primarily cover children (Shea et al., 2021), to cover autistic young adults could decrease the need for ID diagnosis accrual and serve as an important step in improving health and outcomes for autistic adults (Turcotte et al., 2016). Engaging autistic individuals and their families in their health insurance access and healthcare experiences represents critically important input to understanding next steps for needed research.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Kaitlin Koffer Miller, MPH, and Dylan Cooper for their assistance with the study’s development. The authors acknowledge Amy R. Pettit, PhD for her feedback and assistance with editing.

Funding:

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) at the National Institutes of Health [R01MH117653].

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This study was approved by the Drexel University Institutional Review Board.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Boat TF, & Wu JT (2015). Clinical Characteristics of Intellectual Disabilities. In Mental disorders and disabilities among low-income children. Committee to Evaluate the Supplemental Security Income Disability Program for Children with Mental Disorders. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs A, Sculpher M, & Claxton K (2006). Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. Oup Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Carey ME, Tao S, Miller KHK, Marcus SC, Mandell DS, Epstein AJ, & Shea LL (2023). Association Between Medicaid Waivers and Medicaid Disenrollment Among Autistic Adolescents During the Transition to Adulthood. JAMA Network Open, 6(3), e232768–e232768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd BP, & Kennedy CH (2014). Assessment and treatment of challenging behaviour for individuals with intellectual disability: A research review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(3), 187–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohl A, Grice Sheff M, Small S, Nguyen J, Paskor K, & Zanjirian A (2017). Predictors of employment status among adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Work, 56(2), 345–355. 10.3233/wor-172492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolo MC, Friedman C, Lulinski-Norris A, & Braddock D (2013). Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) waivers: A nationwide study of the states. Intellectual and developmental disabilities, 57(1), 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck PT, Garfield T, Roux AM, Rast JE, Anderson K, Hassrick EM, & Kuo A (2020). Services for Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Systems Perspective. Current Psychiatry Reports, 22(3), 13. 10.1007/s11920-020-1136-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea LL, Field R, Xie M, Marcus S, Newschaffer C, & Mandell D (2019). Transition-age Medicaid coverage for adolescents with autism and adolescents with intellectual disability. American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities, 124(2), 174–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea LL, Koffer Miller KH, Verstreate K, Tao S, & Mandell D (2021). States’ use of Medicaid to meet the needs of autistic individuals. Health Services Research, 56(6), 1207–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea LL, Tao S, Marcus SC, Mandell D, & Epstein AJ (2022). Medicaid Disruption Among Transition-Age Youth on the Autism Spectrum. Medical Care Research and Review, 79(4), 525–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea LL, Xie M, Turcotte P, Marcus S, Field R, Newschaffer C, & Mandell D (2018). Brief report: Service use and associated expenditures among adolescents with autism spectrum disorder transitioning to adulthood. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 48(9), 3223–3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte P, Mathew M, Shea LL, Brusilovskiy E, & Nonnemacher SL (2016). Service needs across the lifespan for individuals with autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 46(7), 2480–2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas SH, Grosse SD, Lavelle TA, Maenner MJ, Dietz P, & Ji X (2021, Aug). Healthcare Costs of Pediatric Autism Spectrum Disorder in the United States, 2003-2015. J Autism Dev Disord, 51(8), 2950–2958. 10.1007/s10803-020-04704-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]