Abstract

Factor XII (FXII), the zymogen of the protease FXIIa, contributes to pathologic processes such as bradykinin-dependent angioedema and thrombosis through its capacity to convert the homologs prekallikrein and factor XI to the proteases plasma kallikrein and factor XIa. FXII activation and FXIIa activity are enhanced when the protein binds to a surface. Here, we review recent work on the structure and enzymology of FXII with an emphasis on how they relate to pathology. FXII is a homolog of pro-hepatocyte growth factor activator (pro-HGFA). We prepared a panel of FXII molecules in which individual domains were replaced with corresponding pro-HGFA domains and tested them in FXII activation and activity assays. When in fluid phase (not surface bound), FXII and prekallikrein undergo reciprocal activation. The FXII heavy chain restricts reciprocal activation, setting limits on the rate of this process. Pro-HGFA replacements for the FXII fibronectin type 2 or kringle domains markedly accelerate reciprocal activation, indicating disruption of the normal regulatory function of the heavy chain. Surface binding also enhances FXII activation and activity. This effect is lost if the FXII first epidermal growth factor (EGF1) domain is replaced with pro-HGFA EGF1. These results suggest that FXII circulates in blood in a “closed” form that is resistant to activation. Intramolecular interactions involving the fibronectin type 2 and kringle domains maintain the closed form. FXII binding to a surface through the EGF1 domain disrupts these interactions, resulting in an open conformation that facilitates FXII activation. These observations have implications for understanding FXII contributions to diseases such as hereditary angioedema and surface-triggered thrombosis, and for developing treatments for thrombo-inflammatory disorders.

Keywords: factor XII, prekallikrein, factor XI, pro-HGFA, contact activation, kallikrein-kinin system

Factor XII (FXII), the precursor of the trypsin-like protease factor XIIa (FXIIa),1–3 was first identified as a blood constituent missing in a few individuals whose plasmas clotted slowly when exposed to Pyrex glass (borosilicate), but that clotted normally on addition of tissue factor.4,5 The missing entity was originally called Hageman factor after the index case and was subsequently designated FXII in recognition of its presumed importance to blood clotting.6 Similar isolated defects in glass-initiated coagulation had been observed in patients with the inherited hemorrhagic disorders hemophilia (factor VIII deficiency), Christmas disease (factor IX deficiency), and plasma thromboplastin antecedent deficiency (factor XI deficiency). But in contrast to these conditions, FXII deficiency (Hageman trait) did not cause an obvious bleeding tendency.4,5,7 While FXII serves a limited role in stemming injury-induced bleeding (hemostasis), it contributes to several host–defense and injury-response pathways, and a variety of pathologic processes.1,2,8,9 There is particular interest in the protein as a therapeutic target because of its roles in inflammation and thrombosis, and its limited contribution to hemostasis.10–15 In this review, we discuss recent work on the structure and enzymology of FXII that provides insights into mechanisms by which it contributes to thrombo-inflammatory processes.

The Kallikrein-Kinin System and Contact Activation

Any analysis of FXII requires an appreciation of its activities within the context of the plasma kallikrein-kinin system (KKS). In addition to FXII, the KKS consists of the proteins prekallikrein (PK) and high-molecular-weight kininogen (HK).3,8,16 In solution, the zymogens FXII and PK convert each other to the proteases FXIIa and plasma kallikrein (PKa; ►Fig. 1A).3,17,18 Reciprocal activation is accelerated when FXII and PK bind to a surface such as silicate glass, a process called contact activation (►Fig. 1B).8,16–18 On the surface, FXII also undergoes autocatalytic conversion to FXIIa (autoactivation).8,16–18 Most substances that induce contact activation carry a negative surface charge. Nonbiologic materials, such as silicates (e.g., glass, kaolin, Celite)4,19,20 and metals (e.g., titanium),21 and biological macromolecules including polymers of orthophosphate (polyphosphates),22–24 nucleic acids,25–28 and glycosaminoglycans29,30 support contact activation. HK serves at least two key functions in the KKS.31 First, it is a substrate for PKa, which cleaves it at two specific locations to release the vasoactive peptide bradykinin (►Fig. 1C).8,31,32 Second, it is a cofactor that facilitates PK binding to surfaces (►Fig. 1B).31–33 During contact activation, FXIIa also converts factor XI (FXI), a homolog of PK, to factor XIa (FXIa; ►Fig. 1B).31,34,35 As with PK, HK enhances FXI surface binding. Surface-dependent FXI activation is a major mechanism by which FXIIa drives thrombin generation and clot formation.

Fig. 1.

The kallikrein-kinin system and contact activation. (A) Reciprocal activation of factor XII (FXII) and prekallikrein (PK) in the absence of a surface. (B) Contact activation on a negatively charged surface (gray cloud) includes autoactivation of FXII, subsequent reciprocal activation of FXII and PK, and FXIIa activation of factor XI (FXI). High-molecular-weight kininogen (HK) facilitates PK and FXI binding to the surface. (C) Schematic diagram of HK showing the domain (D1–D6) structure and the position of bradykinin (BK) within domain 4. PKa cleaves HK at two locations to release BK.

FXII and PK reciprocal activation, as well as PKa cleavage of HK, appears to occur at a basal level in vivo.36–38 The produced bradykinin likely contributes to setting normal vascular tone and permeability through binding to specific cellular receptors. It is not clear if basal activation of KKS proteases is surface dependent, surface independent, or a combination of both. Increased local bradykinin production at injury sites leads to changes in vascular permeability, tissue swelling, and pain sensation as part of the host–defense response.

Disease Processes Involving the Kallikrein-Kinin System

The KKS contributes to a spectrum of pathologic processes.1,8,17,39–41 Here we concentrate on a group of inherited disorders referred to collectively as hereditary angioedema (HAE),42–44 and on thrombosis triggered when blood encounters nonbiologic surfaces such as those found in medical devices.45–47

Patients with HAE experience episodic soft-tissue swelling involving the oropharynx, hands, face, gastrointestinal tract, and genitals.42–44 In contrast to the common histamine-induced swelling in IgE-mediated allergic reactions, tissue swelling in HAE is caused by excessive bradykinin production or, perhaps in some cases, heightened vascular sensitivity to bradykinin.42,43 Angioedema in the most common forms of HAE responds to treatments that neutralize PKa or FXIIa,11,48 attesting to the importance of the KKS in the disease process.

During contact activation, FXIIa converts FXI to FXIa, a potent activator of the plasma clotting protein factor IX.7,8 PKa also has some capacity to activate factor IX.49–52 These reactions may be most important for triggering thrombosis during clinical procedures where blood is exposed to materials that support contact activation, including renal dialysis, cardiopulmonary bypass, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and central venous catheter placement.45,46 While PK and FXI are structurally similar, the latter undergoes reciprocal activation with FXII weakly in solution and is a poor FXIIa substrate in the absence of a surface.2,3

The Factor XII Molecule

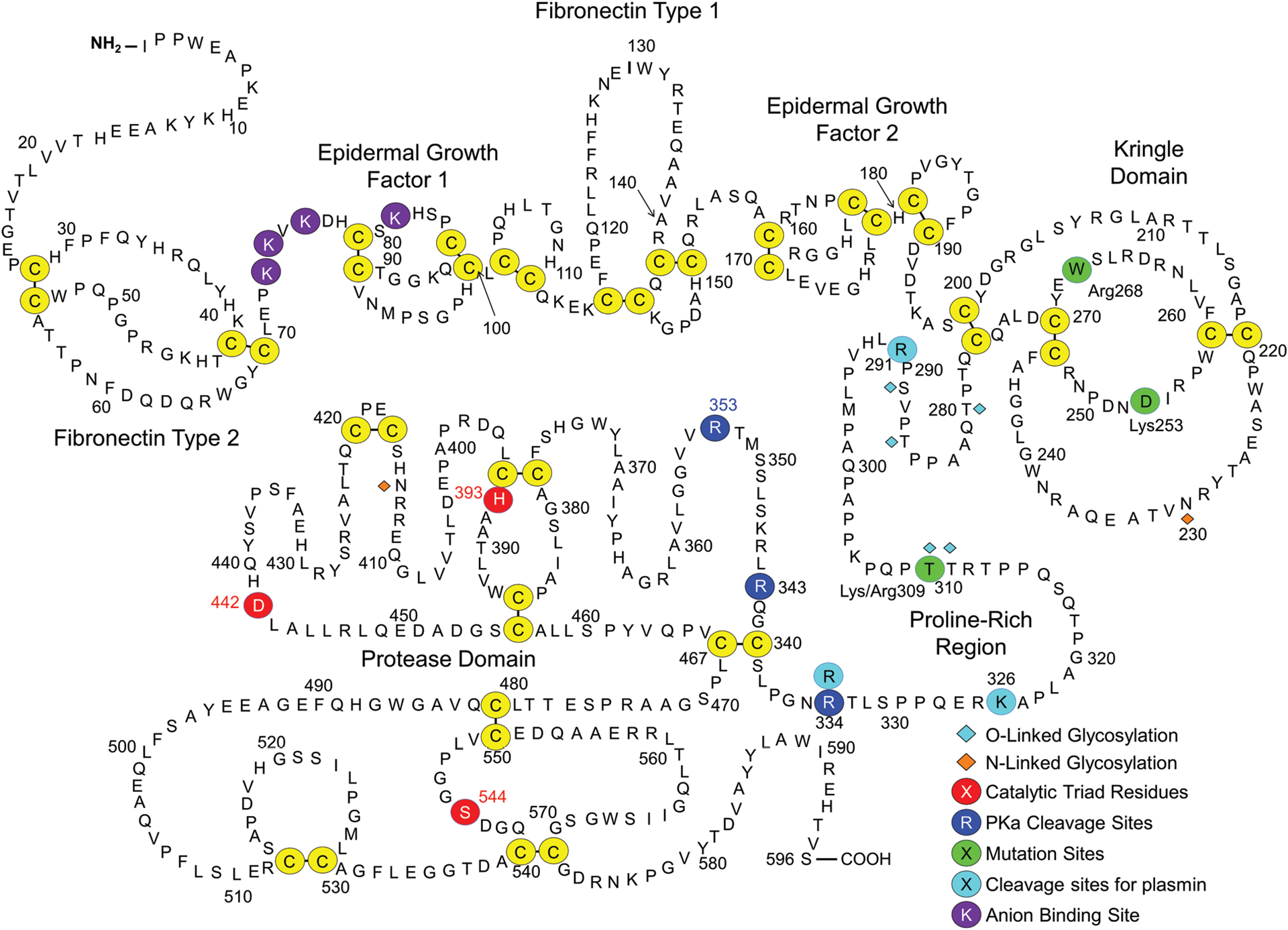

Human FXII is an ~80-kDa polypeptide with a plasma concentration of ~30 μg/mL (375 nM).1,3,53–55 Most plasma FXII is synthesized in hepatocytes, but the protein is expressed in other tissues including leukocytes.56 The diagram in ►Fig. 2 shows the amino acid sequence, disulfide bond locations, and predicted domain structures for human FXII.3,57 The numbering system used hereafter designates the N-terminal isoleucine of the mature plasma protein as residue 1. From the N-terminus, the non-catalytic portion of FXII (amino acids 1–353) contains fibronectin type 2 (FN2), first epidermal growth factor (EGF1), fibronectin type 1 (FN1), a second EGF (EGF2), and kringle (KNG) domains. There is also a proline-rich region (PRR) that does not clearly share homology with domains in other blood proteins. At the C-terminus is the protease domain (amino acids 354–596).

Fig. 2.

Factor XII. Shown are the amino acid sequence and domain structure of human plasma FXII. The FXII heavy chain contains fibronectin type 2, epidermal growth factor 1, fibronectin type 1, epidermal growth factor 2 and kringle domains, and a proline-rich region. The protease domain is a trypsin-like catalytic unit. Disulfide bonds between cysteine residues are shown in yellow circles. The catalytic triad (His393, Asp442, and Ser544) are indicated by red circles. Cleavage sites for PKa (Arg334, Arg343, Arg353) are indicated by dark blue circles. Residues in green are sites of mutations discussed in the text. Plasmin cleavage sites (Arg291, Lys326, Arg334) are indicated in light blue. Anion-binding residues (Lys73, Lys74, Lys76, and Lys81) are indicated by purple circles.

Conversion of FXII to FXIIa requires proteolytic cleavage after Arg353.1,3,53,58 This creates a heavy chain (amino acids 1–353) and light chain (amino acids 354–596) that remain connected by a disulfide bond between Cys340 and Cys467 (►Figs. 2 and 3A).3,57 During activation, FXII is also cleaved after Arg343 (►Fig. 2), which in combination with cleavage after Arg353 should release a 10-amino-acid peptide (Leu344 to Arg353).58 The functional significance of the Arg343 cleavage is not established. Human FXIIa may also undergo cleavage after Arg334, removing the heavy chain to create the truncated protease β-FXIIa (►Figs. 2 and 3A).57–60 Arg334, unlike Arg343 and Arg353, is not conserved, implying β-FXIIa does not form in all species.

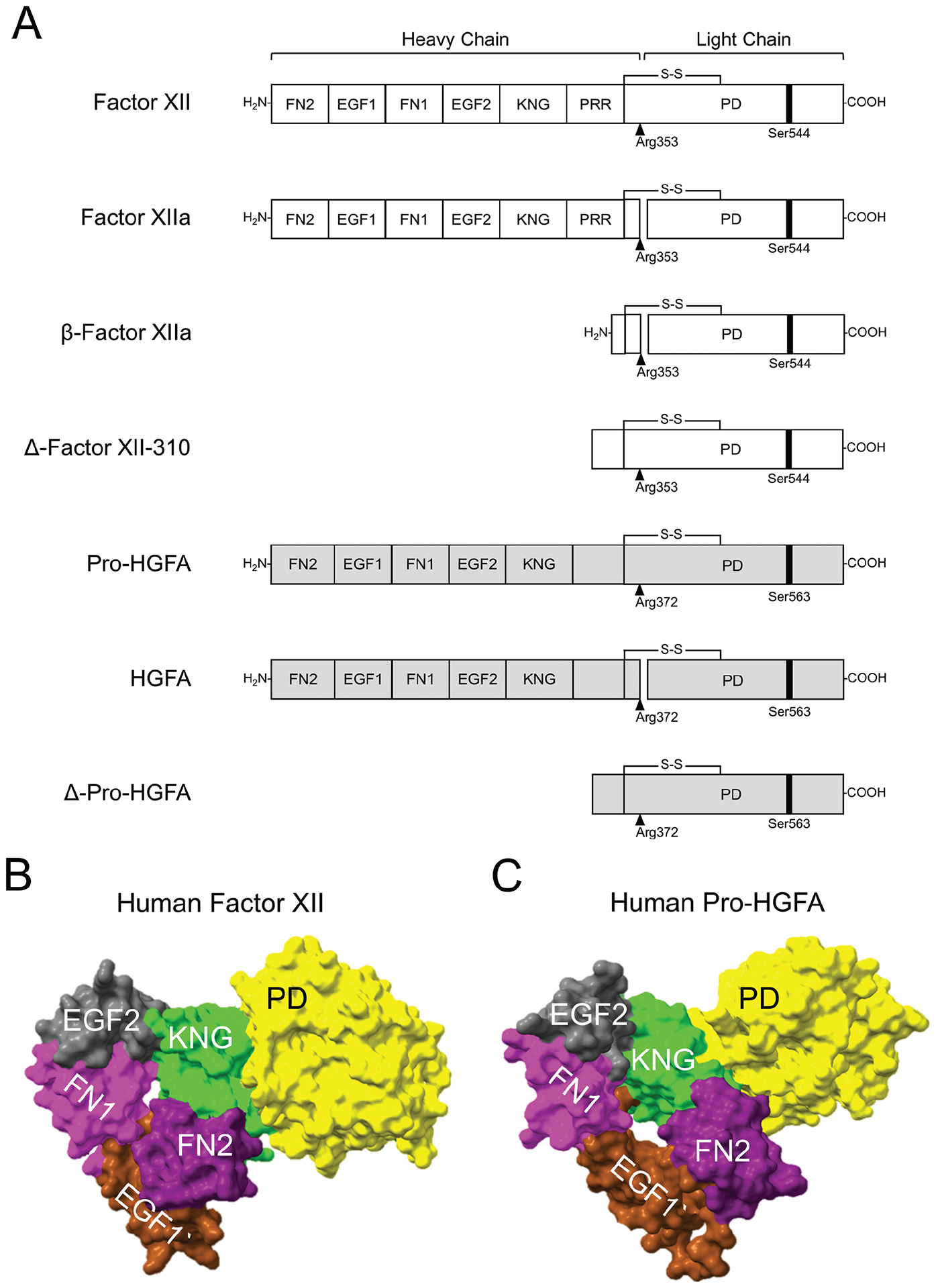

Fig. 3.

Factor XII and pro-hepatocyte growth factor activator structures. (A) Schematic diagrams of FXII (white), pro-HGFA (gray), and their activated and truncated forms. Pro-HGFA is organized similarly except that it does not have a PRR, and the corresponding sequence is not assigned a name. Positions of FXII and pro-HGFA active site serine residues (Ser544 and Ser563, respectively) are indicated by black bars, and sites for proteolytic activation (after Arg353 and Arg372, respectively) are indicated by black arrows. AlphaFold predictions for (B) human FXII and (C) human pro-HGFA. The fibronectin type 2 (FN2, purple), epidermal growth factor 1 (EGF1, brown), fibronectin type 1 (FN1, magenta), epidermal growth factor 2 (EGF2, gray), kringle (KNG, green), and protease (PD, yellow) domains are shown. The proline-rich region of FXII and corresponding area for pro-HGFA have been removed because AlphaFold did not assign a structure to them.

Attempts to crystalize full-length FXII or FXIIa for structural analyses have not been successful. Crystal structures for the protease domain59–61 and fragments of the heavy chain62–64 have been reported, and structures for individual domains (except for the PRR) may be predicted based on homology with other proteins. In a predicted structure for the whole FXII molecule generated by the artificial intelligence-based program AlphaFold,54,65 domains within the FXII non-catalytic heavy chain region fold into a structure with the FN2 domain and KNG domain approximated (►Fig. 3B). Emsely and colleagues recently described a crystal structure for a recombinant FXII heavy chain fragment spanning FN2 through KNG in which KNG and FN2 also interact.64 AlphaFold did not assign a conformation to the PRR in the full-length structure, instead displaying it as an extended ribbon without specific interactions with other parts of the molecule (not included in ►Fig. 3B). Indeed, the length of the PRR varies considerably across species (►Fig. 4), suggesting that the structure, and possibly its function, also varies.

Fig. 4.

Proline-rich region variability. FXII PRR sequences between cysteine residues 276 and 340 (human sequence) are shown from representative organisms for different classes of vertebrates. The corresponding regions from human, mouse, and lung fish pro-HGFA are also shown. Proline residues are in red.

Evolutionary Considerations

The FXII gene (F12) arose from a duplication of the HGFAC gene encoding the injury response protease pro-hepatocyte growth factor activator (pro-HGFA; ►Fig. 3A).52,66,67 F12 has not been found in jawless, cartilaginous, or ray-finned fish.

The most primitive organism in which F12 has been identified is the West African lungfish Protopterus annectens, a sarcopterygian or lobe-finned fish. Sarcopterygii are ancestor to terrestrial vertebrates (tetrapods) and are more closely related to them in some respects than to other fish. F12 is present in most land vertebrates but, notably, has been lost in two lineages. F12 was deactivated in a common ancestor of all living birds, with no gene remnant detectable in extant species.64 In cetaceans (whales, porpoises, and dolphins), F12 is converted to a pseudogene by a point mutation common to all members of the infraorder.52,66,68 Interestingly, the Klkb1 gene encoding PK appears to have been lost in cetaceans prior to deactivation of F12.52,66,68 This raises the possibility that selection pressure to maintain F12 was reduced after Klkb1 deactivation because the major adaptive function of FXII is PK activation.

In clinical laboratories, contact activation-initiated clotting is tested in the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) assay by adding micronized silica (SiO2) or another contact activator to plasma. While use of SiO2 in laboratory testing may seem irrelevant to physiology, silicates form a substantial part of the Earth’s crust. Most terrestrial vertebrates spend their lives in intimate contact with silicate-rich soils, which likely contaminate wounds during and after injury.69 Juang et al showed that applying silicate-rich earth to surgical tail wounds shortens the duration of bleeding in wild-type mice but not in FXII-deficient mice.70 Birds and cetaceans, the two vertebrate lineages that have lost F12, probably spend less time than other tetrapods in contact with silicate-rich earths.

Factor XII Activation in Solution

In the absence of a surface, FXII and PK are reciprocally converted to FXIIa and PKa (►Figs. 1A and 5A, B, left panel).3,17,18 Reciprocal activation could be triggered by traces of FXIIa or PKa contaminating FXII and PK preparations. However, FXII and PK express activity in their zymogen forms that may maintain reciprocal activation.17,71 The protease domains of FXII and the fibrinolytic protease tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) are closely related. tPA expresses significant activity in its single-chain zymogen form,72 a property referred to as low zymogenicity. For FXII, replacing Arg334, Arg343, and Arg353 with alanine at the known cleavage sites (►Fig. 2) creates FXII-T, a protein that is locked into a form that cannot be converted to FXIIa.17,73 Despite this, FXII-T converts PK to PKa in solution (►Fig. 5B, right panel) and activates FXII and FXI in the presence of a surface.17 FXII-T activity is three orders of magnitude lower than that of FXIIa,17 but this may be sufficient to sustain continuous PK activation in plasma to contribute to basal bradykinin generation. This activity probably does not account for all basal bradykinin production, however, as some kinins are detectable in plasmas of FXII-deficient mice.37

Fig. 5.

Properties of factor XII-T and factor XII truncated forms. (A) Reciprocal FXII-PK activation. PK (60 nM) was mixed with 12.5 nM FXII or ΔFXII-310, and 200 uM chromogenic substrate S-2302 at 37 °C. Changes in optical density (OD) at 405 nm were continuously monitored. (B) PK activation by FXII and FXII-T. FXII or FXII-T (200 nM) and PK (200 nM) were incubated at 37 °C. At indicated times, samples were evaluated by Western blot using anti-FXII or anti-PK polyclonal IgGs. Positions of standards for FXII (XII) and PK and the heavy chain (HC) and light chain (LC) of FXIIa and PKa are indicated on the right. (C) FXII activation. FXII (○), the full-length FXII precursor used to generate ΔFXII-Lys309 (□), and ΔFXII-310 (4), 200 nM each, were incubated at 37 °C with PKa (10 nM). FXIIa activity was measured by chromogenic assay. (D) FXII-induced HK cleavage. Western blots of human FXII-deficient plasma supplemented with FXII or ΔFXII-310 (400 nM). At indicated times, samples were removed into a nonreducing sample buffer. Western blots were probed with anti-HK IgG. Positions of standards for HK and cleaved HK (HKa) are shown on the right. (E) Bradykinin generation in normal plasma after addition of 160 nM ΔFXII-310 (●), ΔFXII-310 and kallikrein inhibitor (KV999272 10 nM; ●), or vehicle (○). Bradykinin was measured by ELISA. (F) FXII cleavage by plasmin. FXII was incubated with plasmin and analyzed by Western blot using a polyclonal anti-FXII IgG under nonreducing conditions. Positions of three truncated forms are indicated by arrows. (G) Nonreducing Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-PAGE of purified recombinant wild-type FXII and truncated forms. (H) PK (60 nM) was mixed with 12.5 nM FXII (○), Δ292 (□), Δ327 (◊), or Δ335 (Δ). PKa generation was determined with a chromogenic assay. (I) HK cleavage in human FXII-deficient plasma after supplementing with FXII, ΔFXII-292, ΔFXII-327, and ΔFXII-335. The procedure is the same as in panel D. Panels A, C, D, and E are from Shamanaev et al.20 Panel B is from Ivanov et al.17

Regulation of Factor XII Activation

In plasma, reciprocal activation of FXII and PK, and FXIIa and PKa activity, are regulated by the serpin C1-inhibitor (C1-INH).74 Inherited C1-INH deficiency is the most common cause of HAE,42,43 with most patients having plasma C1-INH activity levels of 5 to 30% of normal. The episodic nature of angioedema in HAE patients indicates triggering events periodically increase KKS activity to the point that it exceeds the capacity of the reduced C1-INH to control it properly. It is not clear that bradykinin formation in C1-INH-deficient patients is surface-dependent (i.e., is triggered by contact activation),75 but at least one type of HAE is likely surface-independent.

It is estimated that at least 10% of HAE patients have normal C1-INH levels.76–79 In some, HAE is associated with a lysine or arginine replacement of Thr309 in FXII (FXII-Lys/Arg309; ►Fig. 2).80,81 The replacement creates a novel cleavage site for trypsin-like proteases including plasmin, thrombin, and FXIa.18,82 Cleavage after Lys/Arg309 creates a truncated species lacking most of the heavy chain that we will refer to as ΔFXII310 (►Figs. 2 and 3A),18,82 the number indicating the new N-terminal amino acid.57 As the heavy chain is required for FXII surface-binding (discussed later), ΔFXII310 cannot support contact activation.18 We observed that ΔFXII310 is activated by PKa with a catalytic efficiency at least 15-fold greater than for FXII (►Fig. 5C). As a result, ΔFXII310 accelerates reciprocal FXII-PK activation (►Fig. 5A). Adding ΔFXII310 to plasma overwhelms endogenous C1-INH leading to rapid cleavage of HK (►Fig. 5D) and bradykinin release (►Fig. 5E).18 These results support those of de Maat et al, who demonstrated accelerated FXII and PK activation in plasma in which ΔFXII310 forms.82 Thus, in patients carrying the FXII-Lys/Arg309 substitution, truncation likely sets off a surface-independent process that leads to excessive bradykinin production and angioedema.

Intravenous infusion of tPA converts the plasma zymogen plasminogen to the fibrin-degrading protease plasmin, a strategy used to restore blood vessel patency after thrombotic occlusion. In some patients, tPA infusion triggers angioedema.83,84 Plasmin converts FXII to FXIIa, suggesting a possible underlying mechanism.82,85 However, we observed that plasmin cleaves FXII into multiple species. Using Edman degradation, we identified cleavage sites that produced these fragments (Ivan Ivanov, PhD, and David Gailani, MD, unpublished data). Plasmin cleaves FXII after Arg291, Arg326, or Arg334 in the PRR, forming the truncated species ΔFXII292, ΔFXII327, and ΔFXII335 (►Fig. 5F). We expressed these proteins in HEK293 cells (►Fig. 5G).17,18,20 ΔFXII292, ΔFXII327, and ΔFXII335 accelerate reciprocal activation with PK similar to ΔFXII310 (►Fig. 5H), leading to rapid HK cleavage in plasma (►Fig. 5I). de Maat and colleagues identified cleavage sites for neutrophil elastase and cathepsin K within the PRR that have a similar accelerating effect on PKa-catalyzed FXII activation.86 These observations raise the possibility that a function of the PRR is to provide cleavage sites specifically for FXII truncation to enhance bradykinin production in certain situations. Interestingly, the arginine residues at the plasmin cleavage sites in the human FXII PRR are not conserved across species (►Fig. 4). Given the heterogeneity in length and composition of the PRR, it is possible that different proteases catalyze FXII truncation in different species. Zamolodchikov et al identified an mRNA in neurons encoding a truncated FXII (ΔFXII297) that is present in the cerebrospinal fluid of some patients with Alzheimer’s disease or multiple sclerosis.87 As with other truncated forms, ΔFXII297 is activated faster than FXII by PKa. Taken as a whole, these observations support the hypothesis that the non-catalytic domains in FXII perform a regulatory function that restricts FXII activation in the absence of a surface, limiting the rate of FXII/PK reciprocal activation and bradykinin formation.

Strategy for Studying Factor XII Domain Structure–Function Relationships

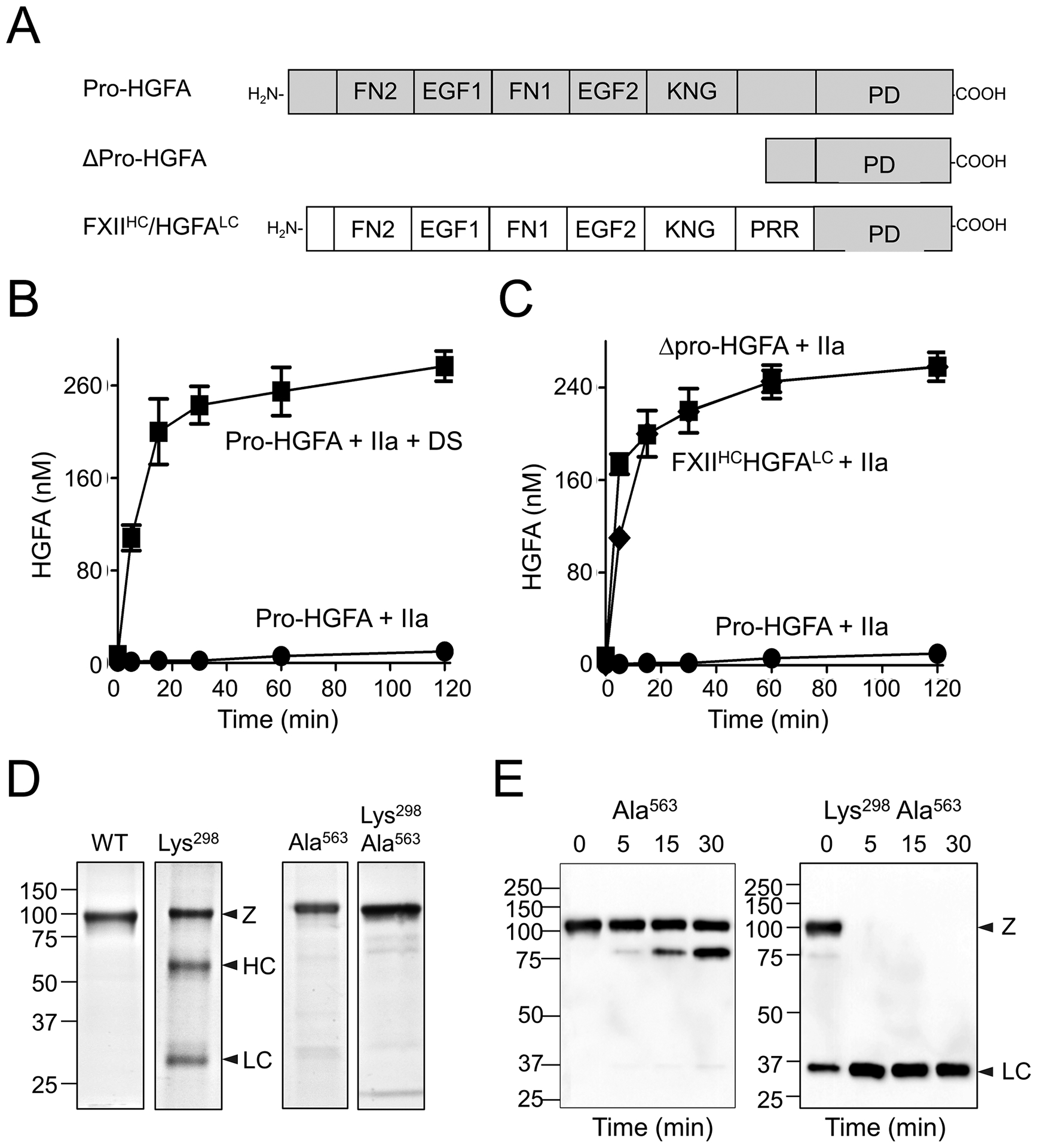

The paralogs FXII and pro-HGFA have similar disulfide bond and domain organization (►Fig. 3A).57,67 Predicted structures for the proteins determined by AlphaFold support the impression that the proteins have similar structures (►Fig. 3B, C). As discussed, FXII in solution behaves as if it is in a “closed” conformation that is relatively resistant to activation by PKa.17,20,73 Removing the heavy chain converts the protein to an open conformation with a more accessible activation cleavage site.17,20 In the absence of a surface, pro-HGFA is also in a closed conformation, rendering it resistant to activation by thrombin, its presumed physiologic activator (►Fig. 6B).20 As with FXII, removing the pro-HGFA heavy chain to create Dpro-HGFA (►Fig. 6A) markedly enhances activation by thrombin in the absence of a surface (►Fig. 6C).20 The heavy chains of both FXII and pro-HGFA, therefore, limit protease activation in solution.

Fig. 6.

Pro-HGFA activation by thrombin. (A) Schematic diagrams of pro-HGFA, Δ-pro-HGFA, and FXII-HC/HGFA-LC. Abbreviations for domains are the same as in ►Fig. 3. (B) Activation of pro-HGFA. Pro-HGFA (260 nM) was incubated with thrombin (26 nM) in the absence (●) or presence (■) of dextran sulfate (10 μg/mL) at 37 °C. (C) Pro-HGFA (●), Δpro-HGFA (▲), or FXII-HC/HGFA-LC (♦), 260 nM each, was incubated with thrombin (26 nM) in the absence of a surface at 37 °C. For panels B and C, at indicated times, samples of reaction were stopped and HGFA generation was determined by chromogenic assay. (D) Nonreducing Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-PAGE of recombinant wild-type pro-HGFA, pro-HGFA-Lys309, pro-HGFA-Ala563, and pro-HGFA-Lys309, Ala563. (E) Pro-HGFA-Ala563 and pro-HGFA-Lys309, Ala563, each 260 nM, were incubated with 26 nM thrombin in the absence of a surface. At indicated times, samples were removed, and size fractionated by reducing SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with anti-hemagglutinin IgG which recognizes a tag on the C-terminus of the HGFA light chain. Panels are from Shamanaev et al.20

Despite their similarities, the human versions of FXII and pro-HGFA differ in important ways. Charges on the FXII heavy and light chains (positive and negative, respectively) are reversed in pro-HGFA.3,20 The sequence corresponding to the FXII PRR is shorter in pro-HGFA, with only four proline residues compared with 19 in FXII (►Fig. 4).20 While PKa cleaves pro-HGFA, it does not do so at the activation cleavage site.20 Most relevant to the analyses described in the following sections, pro-HGFA cannot substitute for FXII in reciprocal activation reactions with PK in solution or on a surface.20 We took advantage of the homology between FXII and pro-HGFA to create a panel of chimeric molecules to study the importance of specific FXII domains to protease function (►Fig. 7A).20

Fig. 7.

Importance of the factor XII FN2 and KNG domains. (A) Schematic diagrams of FXII, Δ-FXII, and HGFA-HC/FXII-LC and FXII/pro-HGFA individual domain chimeras. Abbreviations are the same as in the legend for ►Fig. 3. (B–D) FXII-PK reciprocal activation. PK (60 nM) was mixed with (B) 12.5 nM FXII, HGFA-HC/FXII-LC, ΔFXII-310 or control; (C) 12.5 nM FXII, FXII-pro-HGFA domain chimeras, or control; or (D) 6 nM FXII, HGFA-HC/FXII-LC, FXII-Lys253 or control. For B–D, 200 uM S-2302 was added and changes in OD of 405 nm were continuously monitored on a spectrophotometer. The color coding in panel C matches that in panel A. (E) HK cleavage after supplementing FXII-deficient human plasma with 160 nM FXII or FXII-Lys253. The procedure is the same as in ►Fig. 5D. Panels B–E are from Shamanaev et al.20

Heavy Chain Domains and Regulation of Factor XII Activation

Interestingly, while the heavy chains of FXII and pro-HGFA maintain their respective proteins in closed conformations, they cannot replace each other for this purpose. A chimera with the pro-HGFA heavy chain and the FXII protease domain (HGFA-HC/FXII-LC, ►Fig. 7A) behaves as if it is in an open conformation in reciprocal activation reactions with PK (►Fig. 7B).20 The chimera FXII-HC/HGFA-LC behaves in a similar manner during activation by thrombin (►Fig. 6C).20 Perhaps differences in surface charge, or other subtle structural features, prevent the heavy and light chains from orienting properly relative to each other in the chimeras. This provides an opportunity to study the functional importance of specific FXII heavy chain domains in maintaining the closed conformation. Individual replacement of most FXII heavy chain domains with the corresponding pro-HGFA domains (►Fig. 7A) alters the closed structure,20 as reflected by an increased rate of reciprocal activation with PK (►Fig. 7C). This supports the premise that the heavy chain functions as a unit in regulating protease activation. Replacing the FN2 or KNG domain produced an effect comparable to that seen in HGFA-HC/FXII-LC and ΔFXII310 (►Fig. 7C),20 suggesting these domains play particularly important roles in the closed conformation.

Plasminogen has five KNG domains, four of which contain Asp-X-Asp/Glu motifs that bind side chains of lysine and arginine residues.88,89 These sites mediate intramolecular interactions that maintain full-length Glu-plasminogen in a closed conformation. KNG domains in FXII (►Fig. 2, Asp251-Asn-Asp253) and pro-HGFA (Asp296-Asn-Asp298) also contain Asp-X-Asp motifs.57,67 Disrupting the motifs by replacing the second aspartic acid with lysine (FXII-Lys253 and pro-HGFA-Lys309) renders the proteins more susceptible to activation (Figs. 6D and 7D, respectively).20 Indeed, FXII-Lys253 supports reciprocal activation reactions with PK (►Fig. 7D), and HK cleavage in plasma (►Fig. 7E), comparably to ΔFXII310, suggesting the closed conformation depends on Asp251-Asn-Asp253 interacting with lysine/arginine residues elsewhere in the molecule. Consistent with this, the lysine analog ε-aminocaproic acid, which disrupts interactions involving plasminogen Asp-X-Asp/Glu motifs, also opens the FXII structure.20 Hofman et al identified a Trp268 to arginine substitution in the FXII KNG domain (►Fig. 2) in a patient with a novel auto-inflammatory syndrome. This substitution also opens the FXII conformation,90,91 indicating intramolecular interactions involving KNG extend beyond the Asp-X-Asp motif. For pro-HGFA, the Lys309 variant becomes activated in cell culture (►Fig. 6D). This is prevented by replacing the active site serine (Ser563) with alanine, indicating pro-HGFA-Lys309 undergoes spontaneous autocatalysis (►Fig. 6D).20 Pro-HGFA-Lys309 lacking an active site serine (pro-HGFALys298, Ala309) is highly susceptible to cleavage by thrombin at the activation cleavage site, consistent with an open conformation (►Fig. 6E). This information supports the notion that the lysine/arginine-binding function of the FXII and pro-HGFA KNG domains are required for maintaining their respective proteins in a closed conformation.

Surface-Dependent Factor XII Activation

Platelets secrete polyphosphates upon activation that have a variety of procoagulant effects on human blood.23,24,92 When FXII binds polyphosphate, it undergoes autocatalytic conversion to FXIIa (►Fig. 8A), and its activation by PKa is enhanced (►Fig. 8B).16,17,24 Surface binding has two major effects on FXII. First, FXII adopts an open conformation, exposing the activation cleavage site.3,20 The ability of a short polymer of dextran sulfate to enhance FXII activation by PKa demonstrates this effect (►Fig. 8C). Second, FXII and an activating protease (PKa or FXIIa) bind near each other on a surface to enhance activation through a “template” mechanism.3,20 The template mechanism requires longer dextran sulfate chains to facilitate binding of multiple FXII, FXIIa, and PKa molecules in proximity to each other,93 with activation exhibiting a bell-shaped dependence on surface concentration (►Fig. 8D).3,20,93 The red curve in ►Fig. 8C reflects the combined effect of the conformational and template mechanisms on FXII activation.

Fig. 8.

Factor XII activation and activity. (A, B) FXII activation on polyphosphate. (A) FXII (200 nM) was incubated without (left) or with (right) 70 μM polyphosphate at 37 °C. (B) FXII (100 nM) was mixed with 12.5 nM PKa without (left) or with (right) 70 μM polyphosphate at 37 °C. For panels A and B, samples were removed at indicated time points into reducing sample buffer, and evaluated by Western blot using a polyclonal anti-FXII IgG. Positions of standards for FXII (XII), and the heavy chain (HC) and light chain (LC) of FXIIa are indicated at the right. (C, D) FXII activation with dextran sulfate. (C) FXII (100 nM) and PKa (12.5 nM) were incubated with short-chain dextran sulfate (6–10 kDa, blue), long-chain dextran sulfate (500 kDa, red), or vehicle (black). At indicated times, FXIIa activity was determined with a chromogenic substrate. (D) FXII (100 nM) was incubated with varying concentrations of short-chain (6–10 kDa, blue) or long-chain (500 kDa, red) dextran sulfate. After 30 minutes, FXIIa activity was measured with a chromogenic substrate. (E) FXII, pro-HGFA, HGFA-HC/FXII-LC, FXII-HC/HGFA-LC, or FXII/pro-HGFA chimeras, each 200 nM, were incubated with 70 μM polyphosphate at 37 °C and chromogenic substrate S-2302 (200 uM). Changes in OD at 405 nm were monitored on a spectrophotometer. Comparable reactions without polyphosphate are indicated by dashed lines. The color code is the same as in ►Fig. 7A. (F) FXII, pro-HGFA, or FXII-pro-HGFA chimeras (20 μg) were applied to a heparin-Sepharose column and eluted with a linear NaCl gradient (50–1,000 mmol/L). Shown are NaCl concentrations required to elute protein from the column. (G, H) PK (60 nM) was incubated with 60 pM (G) FXIIa, βFXIIa, HGFA-HC/FXIIa-LC, or (H) activated forms of FXII/pro-HGFA domain chimeras in the absence (G) or presence (G) of 70 μM polyphosphate. At indicated times, aliquots were removed and PKa measured by chromogenic assay. Panels A, C, and D are from Shamanaev et al3 (with permission) and panels E–H are from Shamanaev et al.20

FXII and FXIIa bind to surfaces through their heavy chains. Predictably, truncated species such as ΔFXII310 and β-FXIIa interact poorly with contact surfaces.18,20 A variety of approaches have been used to identify surface-binding sites on FXII, and there is disagreement as to which domain is most important for this process. Most studies indicate that sites in the FN2, EGF1, and FN1 domains in the N-terminal part of the molecule are most important.20,53,62,86,94–100 However, others suggest roles for EGF2, KNG, and the PRR.62,101–103 Many substances that induce contact activetion carry a negative surface charge. We tested the effects of several anionic inducers of contact activation on the panel of FXII/pro-HGFA chimeras.3,20

In experiments with polyphosphate, the only FXII chimeras that failed to autoactivate were those with a pro-HGFA replacement for the EGF1 domain (FXII-EGF1 and HGFAHC/FXIILC; ►Fig. 8E).20 Similar results were obtained with dextran sulfate and ellagic acid as surface20; however, with dextran sulfate, the FN1 domain was also required.20 From this, we can postulate that the positively charged FXII EGF1 domain facilitates binding to anionic surfaces, a notion supported by studies of FXII binding to the polyanion heparin (►Fig. 8F).20 We noted that monoclonal antibodies against the human FXII heavy chain that were selected primarily for their capacity to block contact activation in plasma often bind to the EGF1 domain.104

Clark and colleagues reported that removing the FXII FN2 and EGF1 domains results in a protein that is defective in surface binding, while removing the FN2 domain alone did not cause this defect.100 This is consistent with data for FXII-HGFA chimeras. However, using a panel of internal truncation variants, Heestermans and colleagues reported that FXII in which EGF1 is deleted functions normally in a surface-dependent aPTT assay.103 This raises the possibility that the negative charge on the pro-HGFA EGF1 domain in the FXIIEGF1 chimera may have generated a repulsive effect that gave the false impression that EGF1 mediates surface binding. However, this should not have been an issue with the truncation variants described by Clark et al.100 Furthermore, we observed that replacing a group of lysine residues at the N-terminus of EFG1 (Lys73, Lys74, Lys76, and Lys81; ►Fig. 2) with noncharged alanine reduces surface-dependent FXII activities in a similar manner to what was observed with FXII-EGF1.105 In the study by Heestermans et al, the PRR was implicated in surface binding,103 a conclusion not supported by our work with FXII/pro-HGFA chimeras,20 nor the study from Clark et al.100 The length and sequence of PRRs varies considerably among terrestrial mammals (►Fig. 4), even though their plasmas perform similarly in surface-dependent clotting assays. This suggests that if there is a common surface-binding element in mammalian FXII, it is unlikely to be in the PRR domain.

FXIIa Activity

In the absence of a surface, PK is activated by FXIIa, HGFAHC/FXIIaLC, and the truncated species βFXIIa at similar rates (►Fig. 8G), indicating the FXIIa heavy chain is not required for a productive interaction with PK.20 Given this, it is not surprising that PK is activated by all FXIIa/HGFA heavy chain domain chimeras similar to FXIIa in the absence of a surface.20 Adding polyphosphate enhances PK activation by FXIIa, but not by HGFAHC/FXIIaLC, βFXIIa, or DFXIIa, consistent with the importance of the heavy chain in surface-dependent reactions.20 In reactions with polyphosphate, FXIIa-EGF1 showed a marked defect, and FXIIa-FN1 a modest defect, in PK activation reactions (►Fig. 8H).

A Model for FXII Activation and Activity

The data presented here support the model for FXII activation shown in ►Fig. 9.20 FXII in solution is mostly in a closed conformation with restricted access to the activation cleavage site. The closed conformation appears to require the FN2 and KNG domains, which may facilitate folding of the heavy chain into a structure that physically blocks the activation site, as described for Glu-plasminogen,88,89 or that interacts directly with the protease domain, as observed in plasminogen and prothrombin.88,106,107 Intramolecular interactions between KNG and other parts of the molecule (FN2 and/or other domains) appear to contribute to the closed conformation. Disrupting the closed conformation, either through loss of the heavy chain (e.g., various forms of ΔFXII, FXII lacking an FN2 domain)17,20,86,100 or through structural changes within it (FXII-FN2, FXII-KNG, FXII-Lys253, FXII-Arg268),20,90,91 opens the structure to facilitate FXII activation. Disruption of this mechanism may underlie several disorders associated with angioedema and/or inflammation.18,80,81,90,91

Fig. 9.

A model for factor XII activation. Left. The schematic diagram representing FXII in its closed form in solution, with access to the activation cleavage site at Arg353 (black circle) restricted by components of the heavy chain. Right. When FXII binds to a negatively charged surface, the internal binding interactions involving FN2 and KNG (and perhaps other domains) are disrupted, and the activation cleavage site (black circle) becomes more accessible to cleavage by a protease such as PKa or FXIIa (indicated by scissors). Surface binding in this model is through the EGF1 domain, although other domains may also contribute, and surface-binding domains may vary depending on the surface.

The FXII heavy chain is required for surface-dependent processes during contact activation, including FXII autoactivation, FXII activation by PKa, and FXIIa activation of PK and FXI.20 Our analysis indicates that a series of lysine residues at the N-terminus of the EGF1 domain play a key role in binding to polyanions such as polyphosphate, heparin, and dextran sulfate. In addition to supporting binding, EGF1 may function as a switch that is triggered by binding,54 leading to disruption of interactions involving the KNG and FN2 domains that maintain the closed conformation. In aPTT assays, particles of silica are often used to induce contact activation to drive clot formation. In experiments in which FXII-deficient plasma is reconstituted with FXII or FXI/HGFA chimeras, the only chimera demonstrating a large defect was FXII-EGF1, which expresses only ~3% of the procoagulant activity of wild-type FXII.20

Our analyses of FXII surface-mediated reactions, to this point, have been limited to soluble polyanions (polyphosphate, heparin, dextran sulfate), insoluble silicates (kaolin, silica), or transition metals (titanium)108, all of which carry a negative surface charge.20,105 FXII binding to some surface types, particularly those lacking negative charge, may involve domains other than EGF1. The KKS also assembles on, and is activated on, cell membranes, with FXII and HK interacting with the glycoprotein gC1qR.63,109 The FXII interaction with gC1qR may differ from the largely charged-based interactions we studied. Consistent with this, Kaira et al reported a crystal structure for gC1qR in complex with the isolated FN2 domain of FXII.63 However, it remains unclear if this interaction is necessary for FXII activation on cell surfaces, and further investigation is required to determine if other FXII domains are involved.

Conclusions and Implications

Studies over the past 30 years using a variety of techniques have provided important insights into FXII structure–function relationships but have also generated conflicting data regarding the importance of specific elements to function. Models of FXII generated with AlphaFold suggest there are complex interactions between domains that would not be revealed by crystal structures of isolated domains or even multidomain fragments.54 The complexity of the properly folded molecule raises the possibility that studies with recombinant deletion variants may not be optimal for assessing certain FXII structure–function relationships. Similarly, individual isolated domains removed from the context of the whole molecule may not retain normal activity or may produce artifact. The chimeric approach discussed in this review avoids some pitfalls but could also introduce elements that lead to nonspecific effects on function. These issues, combined with varying effects of different buffer systems on the behavior of contact factors, undoubtedly contribute to disagreements between studies. The results presented here, based on work with FXII/pro-HGFA chimeras, are consistent with some, but not all, recently published work on FXII structure–function relationships. We clearly need data for whole FXII and FXIIa molecules from crystallization, cryoEM, or other structural approaches to put the data into proper context, and to refine our models.

The emerging picture of the FXII molecule provides interesting insights into disease mechanisms and the potential for FXII(a) as a therapeutic target. The dual role of the FXII heavy chain as a regulator of enzyme activity to maintain bradykinin generation within an acceptable range, and as a promoter of blood coagulation, suggests that some methods for inhibiting FXII(a) could have confounding effects. For example, because FXII is not required for hemostasis at an injury site, long-acting therapeutics such as antibodies could be used to block FXII activation relatively safely (from a bleeding perspective). If the goal is to prevent surfaceinitiated FXII activation, it might seem reasonable to target components of the heavy chain to block contact activation. Indeed, this approach was successful in a baboon thrombosis model using the monoclonal anti-FXII IgG 15H8, which binds to the FN2 domain.110 However, we subsequently observed that many antibodies, including 15H8, that block contact activation by binding to the heavy chain region also open the FXII structure, leading to a surge in surface-independent PK activation and HK cleavage.18 Targeting the catalytic domain with an antibody or small molecule inhibitor that blocks the FXIIa active site would seem preferable to targeting the heavy chain from the standpoint of avoiding complications related to bradykinin production. In this case, it will be important to make certain that inhibitors neutralize surface-bound FXIIa as well as FXIIa in solution.

The new data may also provide some insight into a longstanding conundrum. FXIIa activity contributes to tissue edema in HAE through its capacity to activate PK.12 FXIIa also contributes to thrombus formation when blood is exposed to surfaces because of its ability to activate FXI.46 Bradykinin production in HAE is often thought of in terms of a process that occurs on cell surfaces or substances that induce contact activation. This begs the question why do thrombotic events appear to be infrequent in HAE patients during acute episodes of angioedema.111,112 This might be explainable if bradykinin production in HAE is partly, or even largely, surface-independent. The mechanism by which ΔFXII310 causes HAE, at the very least, demonstrates that surface-mediated contact activation is not an absolute requirement for symptomatic HAE.17,82 Alternatively, assembly of the KKS on vascular endothelium or other blood vessel cells, while nominally occurring on a surface, may not promote FXI activation or activity to the same extent as classic contact activation.113,114 FXIIa-induced thrombus formation may require specific types of surfaces such as polyphosphate released from damaged tissue and activated platelets, or chromatin-based extracellular traps released upon neutrophil activation.115 The requirement for a specific surface type may, therefore, distinguish FXIIa-mediated thrombosis from FXIIa-induced angioedema.

Funding

The authors wish to acknowledge the generous support for this work from the Ernest W. Goodpasture chair in Experimental Pathology for Translational Research, and award R35 HL140025 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

D.G. is a consultant for pharmaceutical companies (Anthos Therapeutics; Aronora, Inc.; Bayer Pharma; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Ionis Pharmaceuticals; Janssen, Pharmaceuticals) with interests in targeting factor XI, factor XII, and prekallikrein for therapeutic purposes. The other authors do not have conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Maas C, Renné T Coagulation factor XII in thrombosis and inflammation. Blood 2018;131(17):1903–1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konrath S, Mailer RK, Renné T Mechanisms, functions and diagnostic relevance of FXII activation by foreign surfaces. Hamostaseologie 2021;41(06):489–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shamanaev A, Litvak M, Gailani D. Recent advances in factor XII structure and function. Curr Opin Hematol 2022;29(05):233–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ratnoff OD, Margolius A Jr. Hageman trait: an asymptomatic disorder of blood coagulation. Trans Assoc Am Physicians 1955; 68:149–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ratnoff OD, Colopy JE. A familial hemorrhagic trait associated with a deficiency of a clot-promoting fraction of plasma. J Clin Invest1955G;34(04):602–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright IS. The nomenclature of blood clotting factors. Can Med Assoc J 1962;86(08):373–374 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gailani D, Wheeler AP, Neff AT. Rare coagulation factor deficiencies. In: Hoffman R, Benz EJ, Silberstein LE, eds. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice, 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:2034–2050 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmaier AH. The contact activation and kallikrein/kinin systems: pathophysiologic and physiologic activities. J Thromb Haemost 2016;14(01):28–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pryzdial ELG, Leatherdale A, Conway EM. Coagulation and complement: key innate defense participants in a seamless web. Front Immunol 2022;13:918775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nickel KF, Long AT, Fuchs TA, Butler LM, Renné T Factor XII as a therapeutic target in thromboembolic and inflammatory diseases. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017;37(01):13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valerieva A, Longhurst HJ. Treatment of hereditary angioedemasingle or multiple pathways to the rescue. Front Allergy 2022; 3:952233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craig T, Magerl M, Levy DS, et al. Prophylactic use of an anti-activated factor XII monoclonal antibody, garadacimab, for patients with C1-esterase inhibitor-deficient hereditary angioedema: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2022;399(10328):945–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srivastava P, Gailani D. The rebirth of the contact pathway: a new therapeutic target. Curr Opin Hematol 2020;27(05):311–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fredenburgh JC, Weitz JI. New anticoagulants: moving beyond the direct oral anticoagulants. J Thromb Haemost 2021;19(01): 20–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kluge KE, Seljeflot I, Arnesen H, Jensen T, Halvorsen S, Helseth R. Coagulation factors XI and XII as possible targets for anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Res 2022;214:53–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long AT, Kenne E, Jung R, Fuchs TA, Renné T Contact system revisited: an interface between inflammation, coagulation, and innate immunity. J Thromb Haemost 2016;14(03):427–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ivanov I, Matafonov A, Sun MF, et al. Proteolytic properties of single-chain factor XII: a mechanism for triggering contact activation. Blood 2017;129(11):1527–1537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivanov I, Matafonov A, Sun MF, et al. A mechanism for hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor: an inhibitory regulatory role for the factor XII heavy chain. Blood 2019;133(10):1152–1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu S, Diamond SL. Contact activation of blood coagulation on a defined kaolin/collagen surface in a microfluidic assay. Thromb Res 2014;134(06):1335–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shamanaev A, Ivanov I, Sun MF, et al. Model for surface-dependent factor XII activation: the roles of factor XII heavy chain domains. Blood Adv 2022;6(10):3142–3154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arvidsson S, Askendal A, Tengvall P. Blood plasma contact activation on silicon, titanium and aluminium. Biomaterials 2007;28(07):1346–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hassanian SM, Avan A, Ardeshirylajimi A. Inorganic polyphosphate: a key modulator of inflammation. J Thromb Haemost 2017;15(02):213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker CJ, Smith SA, Morrissey JH. Polyphosphate in thrombosis, hemostasis, and inflammation. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2018;3(01):18–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Ivanov I, Smith SA, Gailani D, Morrissey JH. Polyphosphate, Zn2+ and high molecular weight kininogen modulate individual reactions of the contact pathway of blood clotting. J Thromb Haemost 2019;17(12):2131–2140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kannemeier C, Shibamiya A, Nakazawa F, et al. Extracellular RNA constitutes a natural procoagulant cofactor in blood coagulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104(15):6388–6393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vu TT, Leslie BA, Stafford AR, Zhou J, Fredenburgh JC, Weitz JI. Histidine-rich glycoprotein binds DNA and RNA and attenuates their capacity to activate the intrinsic coagulation pathway. Thromb Haemost 2016;115(01):89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ivanov I, Shakhawat R, Sun MF, et al. Nucleic acids as cofactors for factor XI and prekallikrein activation: different roles for high-molecular-weight kininogen. Thromb Haemost 2017;117(04): 671–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gajsiewicz JM, Smith SA, Morrissey JH. Polyphosphate and RNA differentially modulate the contact pathway of blood clotting. J Biol Chem 2017;292(05):1808–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin L, Xu L, Xiao C, et al. Plasma contact activation by a fucosylated chondroitin sulfate and its structure-activity relationship study. Glycobiology 2018;28(10):754–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oschatz C, Maas C, Lecher B, et al. Mast cells increase vascular permeability by heparin-initiated bradykinin formation in vivo. Immunity 2011;34(02):258–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ponczek MB. High molecular weight kininogen: a review of the structural literature. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22(24):13370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Favier B, Bicout DJ, Baroso R, Paclet MH, Drouet C. In vitro reconstitution of kallikrein-kinin system and progress curve analysis. Biosci Rep 2022;42(10):BSR20221081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh PK, Chen ZL, Horn K, Norris EH. Blocking domain 6 of high molecular weight kininogen to understand intrinsic clotting mechanisms. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2022;6(07):e12815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen ZL, Singh PK, Horn K, Strickland S, Norris EH. Anti-HK antibody reveals critical roles of a 20-residue HK region for Aβ-induced plasma contact system activation. Blood Adv 2022;6 (10):3090–3101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moellmer SA, Puy C, McCarty OJT. HK is the apple of FXI’s eye. J Thromb Haemost 2022;20(11):2485–2487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Revenko AS, Gao D, Crosby JR, et al. Selective depletion of plasma prekallikrein or coagulation factor XII inhibits thrombosis in mice without increased risk of bleeding. Blood 2011;118(19): 5302–5311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iwaki T, Castellino FJ. Plasma levels of bradykinin are suppressed in factor XII-deficient mice. Thromb Haemost 2006;95(06): 1003–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bekassy Z, Lopatko Fagerström I, Bader M, Karpman D. Crosstalk between the renin-angiotensin, complement and kallikrein-kinin systems in inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2022l;22 (07):411–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Girolami JP, Bouby N, Richer-Giudicelli C, Alhenc-Gelas F. Kinins and kinin receptors in cardiovascular and renal diseases. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021;14(03):240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamid S, Rhaleb IA, Kassem KM, Rhaleb NE. Role of kinins in hypertension and heart failure. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2020;13 (11):347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xie Z, Li Z, Shao Y, Liao C. Discovery and development of plasma kallikrein inhibitors for multiple diseases. Eur J Med Chem 2020; 190:112137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santacroce R, D’Andrea G, Maffione AB, Margaglione M, d’Apolito M. The genetics of hereditary angioedema: a review. J Clin Med 2021;10(09):2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zafra H. Hereditary angioedema: a review. WMJ 2022;121(01): 48–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaplan AP, Joseph K, Ghebrehiwet B. The complex role of kininogens in hereditary angioedema. Front Allergy 2022; 3:952753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaffer IH, Fredenburgh JC, Hirsh J, Weitz JI. Medical device-induced thrombosis: what causes it and how can we prevent it? J Thromb Haemost 2015;13(Suppl 1):S72–S81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tillman B, Gailani D. Inhibition of factors XI and XII for prevention of thrombosis induced by artificial surfaces. Semin Thromb Hemost 2018;44(01):60–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Visser M, Heitmeier S, Ten Cate H, Spronk HMH. Role of factor XIa and plasma kallikrein in arterial and venous thrombosis. Thromb Haemost 2020;120(06):883–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anderson J, Maina N. Reviewing clinical considerations and guideline recommendations of C1 inhibitor prophylaxis for hereditary angioedema. Clin Transl Allergy 2022;12(01):e12092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Visser M, van Oerle R, Ten Cate H, et al. Plasma kallikrein contributes to coagulation in the absence of factor XI by activating Factor IX. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2020;40(01): 103–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noubouossie DF, Henderson MW, Mooberry M, et al. Red blood cell microvesicles activate the contact system, leading to factor IX activation via 2 independent pathways. Blood 2020;135(10): 755–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kearney KJ, Butler J, Posada OM, et al. Kallikrein directly interacts with and activates Factor IX, resulting in thrombin generation and fibrin formation independent of Factor XI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021;118(03):e2014810118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ponczek MB, Shamanaev A, LaPlace A, et al. The evolution of factor XI and the kallikrein-kinin system. Blood Adv 2020;4(24): 6135–6147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Maat S, Maas C. Factor XII: form determines function. J Thromb Haemost 2016;14(08):1498–1506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frunt R, El Otmani H, Gibril Kaira B, de Maat S, Maas C. Factor XII explored with AlphaFold - opportunities for selective drug development. Thromb Haemost 2023;123(02):177–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Naudin C, Burillo E, Blankenberg S, Butler L, Renné T Factor XII contact activation. Semin Thromb Hemost 2017;43(08): 814–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Renné T, Stavrou EX. Roles of factor XII in innate immunity. Front Immunol 2019;10:2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cool DE, Edgell CJ, Louie GV, Zoller MJ, Brayer GD, MacGillivray RT. Characterization of human blood coagulation factor XII cDNA. Prediction of the primary structure of factor XII and the tertiary structure of beta-factor XIIa. J Biol Chem 1985;260(25): 13666–13676 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Colman RW, Schmaier AH. Contact system: a vascular biology modulator with anticoagulant, profibrinolytic, antiadhesive, and proinflammatory attributes. Blood 1997;90(10):3819–3843 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pathak M, Wilmann P, Awford J, et al. Coagulation factor XII protease domain crystal structure. J Thromb Haemost 2015;13 (04):580–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dementiev A, Silva A, Yee C, et al. Structures of human plasma β-factor XIIa cocrystallized with potent inhibitors. Blood Adv 2018; 2(05):549–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pathak M, Manna R, Li C, et al. Crystal structures of the recombinant β-factor XIIa protease with bound Thr-Arg and Pro-Arg substrate mimetics. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 2019;75(Pt 6):578–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beringer DX, Kroon-Batenburg LM. The structure of the FnI-EGF-like tandem domain of coagulation factor XII solved using SIRAS. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 2013;69(Pt 2):94–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaira BG, Slater A, McCrae KR, et al. Factor XII and kininogen asymmetric assembly with gC1qR/C1QBP/P32 is governed by allostery. Blood 2020;136(14):1685–1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Emsely J, Saleem M, Li C, Phillipous H. Factor XII heavy chain structure [abstract]. Accessed December 12, 2022 at: https://abstracts.isth.org/factor-xii-heavy-chain-structure/

- 65.David A, Islam S, Tankhilevich E, Sternberg MJE. The AlphaFold database of protein structures: a biologist’s guide. J Mol Biol 2022;434(02):167336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ponczek MB, Gailani D, Doolittle RF. Evolution of the contact phase of vertebrate blood coagulation. J Thromb Haemost 2008;6 (11):1876–1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miyazawa K, Shimomura T, Kitamura A, Kondo J, Morimoto Y, Kitamura N. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the cDNA for a human serine protease responsible for activation of hepatocyte growth factor. Structural similarity of the protease precursor to blood coagulation factor XII. J Biol Chem 1993;268 (14):10024–10028 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huelsmann M, Hecker N, Springer MS, Gatesy J, Sharma V, Hiller M. Genes lost during the transition from land to water in cetaceans highlight genomic changes associated with aquatic adaptations. Sci Adv 2019;5(09):eaaw6671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cooley BC. The dirty side of the intrinsic pathway of coagulation. Thromb Res 2016;145:159–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Juang LJ, Mazinani N, Novakowski SK, et al. Coagulation factor XII contributes to hemostasis when activated by soil in wounds. Blood Adv 2020;4(08):1737–1745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ivanov I, Verhamme IM, Sun MF, et al. Protease activity in single-chain prekallikrein. Blood 2020;135(08):558–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Renatus M, Engh RA, Stubbs MT, et al. Lysine 156 promotes the anomalous proenzyme activity of tPA: X-ray crystal structure of single-chain human tPA. EMBO J 1997;16(16):4797–4805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shamanaev A, Emsley J, Gailani D. Proteolytic activity of contact factor zymogens. J Thromb Haemost 2021;19(02):330–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Karnaukhova E. C1-inhibitor: structure, functional diversity and therapeutic Development. Curr Med Chem 2022;29(03): 467–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Maat S, Joseph K, Maas C, Kaplan AP. Blood clotting and the pathogenesis of types i and ii hereditary angioedema. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2021;60(03):348–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaplan AP. Hereditary angioedema: investigational therapies and future research. Allergy Asthma Proc 2020;41(6, Suppl 1): S51–S54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sharma J, Jindal AK, Banday AZ, et al. Pathophysiology of hereditary angioedema (HAE) beyond the SERPING1 gene. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2021;60(03):305–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bork K, Machnig T, Wulff K, Witzke G, Prusty S, Hardt J. Clinical features of genetically characterized types of hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2020;15(01):289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Veronez CL, Csuka D, Sheikh FR, Zuraw BL, Farkas H, Bork K. The expanding spectrum of mutations in hereditary angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021;9(06):2229–2234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dewald G, Bork K. Missense mutations in the coagulation factor XII (Hageman factor) gene in hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006;343 (04):1286–1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bork K, Wulff K, Meinke P, Wagner N, Hardt J, Witzke G. A novel mutation in the coagulation factor 12 gene in subjects with hereditary angioedema and normal C1-inhibitor. Clin Immunol 2011;141(01):31–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.de Maat S, Björkqvist J, Suffritti C, et al. Plasmin is a natural trigger for bradykinin production in patients with hereditary angioedema with factor XII mutations. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;138(05):1414–1423.e9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Engelter ST, Fluri F, Buitrago-Téllez C, et al. Life-threatening orolingual angioedema during thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke. J Neurol 2005;252(10):1167–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brown E, Campana C, Zimmerman J, Brooks S. Icatibant for the treatment of orolingual angioedema following the administration of tissue plasminogen activator. Am J Emerg Med 2018;36 (06):1125.e1–1125.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ewald GA, Eisenberg PR. Plasmin-mediated activation of contact system in response to pharmacological thrombolysis. Circulation 1995;91(01):28–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.de Maat S, Clark CC, Boertien M, et al. Factor XII truncation accelerates activation in solution. J Thromb Haemost 2019;17 (01):183–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zamolodchikov D, Bai Y, Tang Y, McWhirter JR, Macdonald LE, Alessandri-Haber N. A short isoform of coagulation factor XII mRNA is expressed by neurons in the human brain. Neuroscience 2019;413:294–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Law RH, Caradoc-Davies T, Cowieson N, et al. The X-ray crystal structure of full-length human plasminogen. Cell Rep 2012;1 (03):185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Law RH, Abu-Ssaydeh D, Whisstock JC. New insights into the structure and function of the plasminogen/plasmin system. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2013;23(06):836–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hofman ZLM, Clark CC, Sanrattana W, et al. A mutation in the kringle domain of human factor XII that causes autoinflammation, disturbs zymogen quiescence, and accelerates activation. J Biol Chem 2020;295(02):363–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Scheffel J, Mahnke NA, Hofman ZLM, et al. Cold-induced urticarial autoinflammatory syndrome related to factor XII activation. Nat Commun 2020;11(01):179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Müller F, Mutch NJ, Schenk WA, et al. Platelet polyphosphates are proinflammatory and procoagulant mediators in vivo. Cell 2009; 139(06):1143–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Samuel M, Pixley RA, Villanueva MA, Colman RW, Villanueva GB. Human factor XII (Hageman factor) autoactivation by dextran sulfate. Circular dichroism, fluorescence, and ultraviolet difference spectroscopic studies. J Biol Chem 1992;267(27): 19691–19697 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Revak SD, Cochrane CG, Johnston AR, Hugli TE. Structural changes accompanying enzymatic activation of human Hageman factor. J Clin Invest 1974;54(03):619–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Revak SD, Cochrane CG. The relationship of structure and function in human Hageman factor. The association of enzymatic and binding activities with separate regions of the molecule. J Clin Invest 1976;57(04):852–860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pixley RA, Stumpo LG, Birkmeyer K, Silver L, Colman RW. A monoclonal antibody recognizing an icosapeptide sequence in the heavy chain of human factor XII inhibits surface-catalyzed activation. J Biol Chem 1987;262(21):10140–10145 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Citarella F, Ravon DM, Pascucci B, Felici A, Fantoni A, Hack CE. Structure/function analysis of human factor XII using recombinant deletion mutants. Evidence for an additional region involved in the binding to negatively charged surfaces. Eur J Biochem 1996;238(01):240–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Røjkaer R, Schousboe I. Partial identification of the Zn2+-binding sites in factor XII and its activation derivatives. Eur J Biochem 1997;247(02):491–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Citarella F, te Velthuis H, Helmer-Citterich M, Hack CE. Identification of a putative binding site for negatively charged surfaces in the fibronectin type II domain of human factor XII – an immunochemical and homology modeling approach. Thromb Haemost 2000;84(06):1057–1065 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Clark CC, Hofman ZLM, Sanrattana W, den Braven L, de Maat S, Maas C. The fibronectin type II domain of factor XII ensures zymogen quiescence. Thromb Haemost 2020;120(03): 400–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nuijens JH, Huijbregts CC, Eerenberg-Belmer AJ, Meijers JC, Bouma BN, Hack CE. Activation of the contact system of coagulation by a monoclonal antibody directed against a neodeterminant in the heavy chain region of human coagulation factor XII (Hageman factor). J Biol Chem 1989;264(22):12941–12949 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ravon DM, Citarella F, Lubbers YT, Pascucci B, Hack CE. Monoclonal antibody F1 binds to the kringle domain of factor XII and induces enhanced susceptibility for cleavage by kallikrein. Blood 1995;86(11):4134–4143 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Heestermans M, Naudin C, Mailer RK, et al. Identification of the factor XII contact activation site enables sensitive coagulation diagnostics. Nat Commun 2021;12(01):5596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kohs TCL, Lorentz CU, Johnson J, et al. Development of coagulation factor XII antibodies for inhibiting vascular device-related thrombosis. Cell Mol Bioeng 2020;14(02):161–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shamanaev A, Litvak M, Cheng Q, et al. A site on factor XII required for productive interactions with polyphosphate. J Thromb Haemost 2023;21(06):1567–1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dickeson SK, Kumar S, Sun MF, et al. A mechanism for hereditary angioedema caused by a lysine 311-to-glutamic acid substitution in plasminogen. Blood 2022;139(18):2816–2829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pozzi N, Chen Z, Zapata F, Pelc LA, Barranco-Medina S, Di Cera E. Crystal structures of prethrombin-2 reveal alternative conformations under identical solution conditions and the mechanism of zymogen activation. Biochemistry 2011;50(47):10195–10202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Litvak M, Shamanaev A, Zalawadiya S, et al. Titanium is a potent inducer of contact activation: implications for intravascular devices. J Thromb Haemost 2023;21(05):1200–1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mahdi F, Madar ZS, Figueroa CD, Schmaier AH. Factor XII interacts with the multiprotein assembly of urokinase plasminogen activator receptor, gC1qR, and cytokeratin 1 on endothelial cell membranes. Blood 2002;99(10):3585–3596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Matafonov A, Leung PY, Gailani AE, et al. Factor XII inhibition reduces thrombus formation in a primate thrombosis model. Blood 2014;123(11):1739–1746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Grover SP, Kawano T, Wan J, et al. C1 inhibitor deficiency enhances contact pathway mediated activation of coagulation and venous thrombosis. Blood 2023;141(19):2390–2401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gailani D. Hereditary angioedema and thrombosis. Blood 2023; 141(19):2295–2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Baird TR, Walsh PN. The interaction of factor XIa with activated platelets but not endothelial cells promotes the activation of factor IX in the consolidation phase of blood coagulation. J Biol Chem 2002;277(41):38462–38467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mahdi F, Shariat-Madar Z, Schmaier AH. The relative priority of prekallikrein and factors XI/XIa assembly on cultured endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 2003;278(45):43983–43990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rangaswamy C, Englert H, Deppermann C, Renné T Polyanions in coagulation and thrombosis: focus on polyphosphate and neutrophils extracellular traps. Thromb Haemost 2021;121(08): 1021–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]