Abstract

CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CCT) catalyzes a rate-controlling step in the biosynthesis of phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho). Multiple CCT isoforms, CCTα, CCTβ2, and CCTβ3, are encoded by two genes, Pcyt1a and Pcyt1b. The importance of CCTα in mice was investigated by deleting exons 5 and 6 in the Pcyt1a gene using the Cre-lox system. Pcyt1a−/− zygotes failed to form blastocysts, did not develop past embryonic day 3.5 (E3.5), and failed to implant. In situ hybridization in E11.5 embryos showed that Pcyt1a is expressed ubiquitously, with the highest level in fetal liver, and CCTα transcripts are significantly more abundant than transcripts encoding CCTβ or phosphatidylethanolamine (PtdEtn) N-methyl transferase, two other enzymes capable of producing PtdCho. Reduction of the CCTα transcripts in heterozygous E11.5 embryos was accompanied by upregulation of CCTβ and PtdEtn N-methyltransferase transcripts. In contrast, enzymatic and real-time PCR data revealed that CCTβ (Pcyt1b) expression is not upregulated to compensate for the reduction in CCTα expression in adult liver and other tissues from Pcyt1a+/− heterozygous mice. PtdCho biosynthesis measured by choline incorporation into isolated hepatocytes was not compromised in the Pcyt1a+/− mice. Liver PtdCho mass was the same in Pcyt1a+/+ and Pcyt1a+/− adult animals, but lung PtdCho mass decreased in the heterozygous mice. These data show that CCTα expression is required for early embryonic development, but that a 50% reduction in enzyme activity has little detectable impact on the operation of the CDP-choline metabolic pathway in adult tissues.

Phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho) is the most abundant phospholipid in mammalian cells and plays an important structural role in cellular membranes and lipoprotein metabolism (8, 20). The CDP-choline pathway is the primary route to PtdCho, and CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CCT) is the rate-controlling enzyme in this three-step pathway. CCT activity is tightly regulated by its reversible interaction with lipid regulators and protein phosphorylation (8, 20). A second route to PtdCho is the phosphatidylethanolamine (PtdEtn) N-methyltransferase (PEMT) reaction; however, this pathway is thought to be only of significant importance in the liver (19, 21). PEMT−/− mice have a mild phenotypic defect in hepatic lipoprotein metabolism (15) but die when choline starvation is used to eliminate the CDP-choline pathway for PtdCho synthesis in the liver (21), illustrating that PEMT is an important alternate route to PtdCho in the liver. Esko et al. (6) developed a temperature-sensitive cell line that was conditionally defective in CCT activity, and when this cell line is shifted to the nonpermissive temperature PtdCho synthesis ceases, cell growth halts, and apoptosis ensues (4). Similar results are obtained using chemical inhibitors of CCT (2, 16). These results led to the hypothesis that CCT is essential for mammalian cell survival.

Complexity was introduced into the field with the discovery of a second CCT isoform, called CCTβ (13, 14). CCTα and CCTβ are highly related proteins. Both proteins have very similar catalytic and membrane interaction domains. An amphipathic helix in the membrane interaction domain regulates enzyme activity by controlling the reversible interaction of the protein with phospholipid bilayers (8). However, CCTα has a nuclear localization signal in the amino-terminal domain and is found predominantly in the nucleus (22, 23), while CCTβ lacks this signal and localizes with the endoplasmic reticulum and in the cytosol (13). The CCTα isoform is the product of the Pcyt1a gene and is ubiquitously expressed in cell lines and animal tissues, whereas the CCTβ2 and CCTβ3 isoforms are the products of the mouse Pcyt1b gene and are most highly expressed in the brain (9, 11, 13). Disruption of CCTβ2 expression results in gonadal dysfunction in mice, but the mice are otherwise normal, including the histology of the brain (9), illustrating that CCTα and CCTβ3 can substitute for CCTβ2 function in most tissues. A mouse conditional knockout model to study the role of CCTα in specific tissues was developed (24). The selective deletion of CCTα expression in cells of the macrophage lineage showed a surprisingly mild phenotype (24). The mice had normal numbers of macrophages, and macrophage development was supported in these cells by the upregulation of Pcyt1b gene expression. Similarly, the liver-specific knockout of CCTα yielded viable mice with visually normal livers (10). Although these animals had reduced PtdCho levels both in their liver and in serum lipoproteins, it is clear that CCTα is not essential for liver development, due to the expression of PEMT or perhaps CCTβ. These two experiments with conditional knockouts suggested that the hypothesis that CCTα is essential for mammalian cell survival may not be correct and prompted us to determine if one could derive mice that lack the expression of the Pcyt1a gene in all tissues and to investigate whether CCTβ expression was sufficient. This work shows that the inhibition of CCTα expression has an early embryonic lethal phenotype, with the embryos failing to develop past embryonic day 3.5 (E3.5) and implant, and that CCTβ expression cannot compensate at this stage of development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Targeted disruption of the mouse Pcyt1a gene.

Homozygous Pcyt1aflox mice were derived previously (10, 24) and crossed with transgenic strain FVB/N-TgN(ACTB-Cre)2Mrt (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) expressing Cre recombinase driven by the human β-actin gene promoter. The floxed Pcyt1a locus in the resulting heterozygous embryos was deleted by the blastocyst stage of development, and the heterozygous pups carrying a wild-type and a deleted Pcyt1a gene were identified by PCR-mediated genotyping of tail DNA as described below. The heterozygous mice were intercrossed and anticipated to yield embryos and pups which were wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous for a deleted Pcyt1a allele in a 1:2:1 ratio. Littermates were used as comparison controls.

Genotyping.

The Pcyt1a genotypes were assessed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA extracted from mouse tails or embryos by incubation overnight at 55°C in 50 μl of lysis buffer made up of 20 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM disodium EDTA (Na2EDTA), 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 1 mg of proteinase K/ml. Aliquots of the digestion mixture were used in a PCR with REDTaq genomic DNA polymerase (Sigma). Two sets of primers, illustrated in Fig. 1, detected the wild-type or the Pcyt1a−/− allele. The sequence of forward primer 1 (FP1) was 5′-AATGTCTTCCAGGCTCCATAGG; FP2 was 5′-GAACTTAGGGCCTTATTCAAAGC; RP1 was 5′-TTGCCTGGTTTGTGTTTATGC. Primers FP1 and RP1 yielded a 255-bp product specific for the wild-type allele, and primers FP2 and RP1 yielded a 255-bp fragment specific for the deleted Pcyt1a allele. The PCR consisted of an initial incubation at 94°C for 2 min, then five cycles at 94°C for 30 s and 65°C for 30 s; and another five cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 63°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 5 min. The amplified DNA fragments were distinguished by agarose gel electrophoresis. Preimplantation embryos were collected from pregnant dams on E3.5, where the morning of the day on which a vaginal plug was detected was designated day E0.5. The uterine horns were flushed with HEPES-buffered M2 culture medium and transferred into individual Eppendorf tubes containing 5 μl of lysis buffer (0.05% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 0.035 N NaOH) by using a mouth pipette assembly. The samples were boiled for 3 min, and 2.5 μl of this mixture was used in the PCR with either primer set FP1 and RP1 or primer set FP2 and RP1. The PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel. Due to their low yield, they were detected by Southern blot hybridization with radiolabeled probes corresponding to the sequences amplified by the primers FP1 and RP1 or FP2 and RP1, as appropriate. Blots were visualized using a Typhoon 9200 PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). The probe templates had previously been cloned into the pCR2.1 vector, and the DNA sequences were confirmed by the Hartwell Center for Biotechnology at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.

FIG. 1.

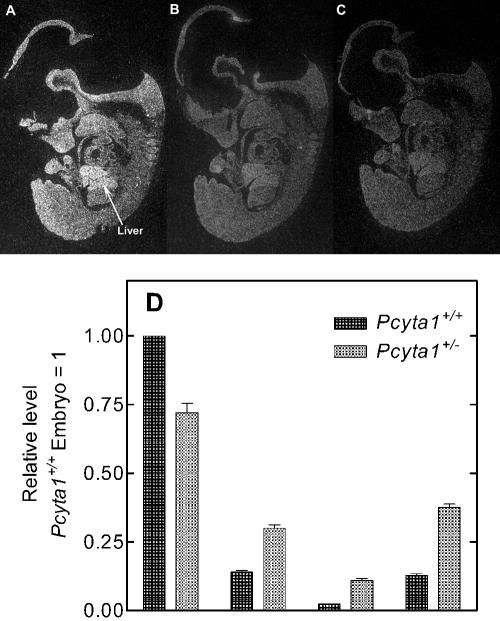

CCTα, CCTβ, and PEMT gene expression in day E11.5 embryos. Embryos (day E11.5) were obtained following timed matings. (A to C) In situ hybridization of fixed and frozen sagittal sections from wild-type mice. The CCTα gene (A) is widely expressed throughout the mouse embryo at E11.5 and is particularly predominant in liver; CCTβ expression (B) is lower; PEMT expression (C) is lower. (D) Real-time PCR quantification of relative abundance of CCT isoform and PEMT transcripts in day E11.5 embryos using primers and probes listed in Table 1. Wild-type and Pcyt1a+/− embryos were also genotyped in an independent assay. Both assays are described in Materials and Methods. The amount of target RNA (2−ΔΔCT) was normalized to the endogenous GAPDH reference (ΔCT) and related to the amount of target CCTα in day E11.5 embryos from Pcyt1a+/+ mice (ΔΔCT), which was set as the calibrator at 1.0.

In situ hybridization.

Riboprobe templates were generated by PCR from plasmid DNA containing the cDNA from Pcyt1a (NM_00981.2) nucleotides (nt) 1088 to 1662, Pcyt1b (NM177546) nt 1358 to 1944, and Pemt (BC026796.1) nt 26 to 651. The 3′-untranslated regions of Pcyt1a and Pcyt1b were selected as templates to achieve sufficient sequence diversity between these two transcripts, and the cDNA sequences were verified by the Hartwell Center for Biotechnology. The templates were cloned into pBluescript, and T7 RNA polymerase was used for in vitro transcription reactions to generate [α-33P]UTP antisense radiolabeled riboprobes for in situ hybridization. E11.5 embryos were removed from the mother by cesarean section and immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 24 h. Embryos were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose (in PBS) and embedded in Triangle Biosciences freezing medium and frozen on dry ice. Sixteen-micrometer tissue sections in the sagittal plane were cut using a cryostat, and tissues were mounted onto Superfrost Plus microscope slides. Several slides with E11.5 tissue were processed identically as the experimental slides, except that they were not hybridized with probe, to document the background signal from the tissues. Gene expression was evaluated by in situ hybridization as described previously (17, 18). Microscope slides were dipped in NBT2 liquid emulsion, and autoradiography proceeded for 9 days at 4°C. NBT2 emulsion-treated slides were developed in Kodak D19 developer and fixer before slides were dehydrated and coverslips were attached with Permount. All treatments, hybridizations, and wash conditions were identical for the probes used in this assay. A nearby section in the tissue block used was stained with cresyl violet as a reference for location of anatomical structures in the mouse. Micrographs were photographed with a Nikon Coolsnap ES camera mounted onto a Zeiss Stemi 11 Stereo microscope. All photographs were captured at 50 ms, using identical settings for all images including the negative control.

Detection of CCT isoform mRNAs.

Real-time PCR was used to determine the relative expression levels of the intact CCTα, CCTβ2, and CCTβ3 isoform transcripts, encoded by the Pcyt1a and Pcyt1b genes, and PEMT mRNA, derived from the Pemt gene, in embryonic and adult tissues. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Pelleted RNA was resuspended in nuclease-free water, digested with DNase I to remove contaminating genomic DNA, aliquoted, and reprecipitated in ethanol and stored at −20°C. Total RNA (0.5 μg) was reverse transcribed with random primers and SuperScript II RNase H− reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out with 10% of the reverse transcription product in a 30-μl reaction volume of Taqman Universal PCR master mixes (Applied Biosystems), using the Applied Biosystems 7300 sequence detection system and software version 1.2.1. Specific primers and probes are listed in Table 1. The Taqman rodent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) control reagent (Applied Biosystems) was the source of the primers and probe for quantifying the control GAPDH mRNA. RNA was isolated from the liver, brain, heart, kidney, and lungs of three mice of each gender individually, and each RNA sample was quantified in quintuplicate. All of the real-time values for each tissue were averaged and compared using the CT method, where the amount of target RNA (2−ΔΔCT) was normalized to the endogenous GAPDH reference (ΔCT) and related to the amount of target CCTα in liver from Pcyt1a+/+ mice (ΔΔCT), which was set as the calibrator at 1.0. Standard deviations from the mean ΔCT values were <10%.

TABLE 1.

Real-time PCR primer-probe sets

| Primer | Sequence | Probea |

|---|---|---|

| mCCTα-Forward | 5′-GATGAGCTAACGCACAACTTCAA | 6FAM-CGCTCATTCTCGTTCATCACAGTGA-TAMRA |

| mCCTα-Reverse | 5′-GTGCTGCACGGCGTCATA | |

| mCCTβ2-Forward | 5′-TTCTTTGCCTGGGAGGAGACT | 6FAM-TGCTCCCTCCAGCTCTACACCCT-TAMRA |

| mCCTβ2-Reverse | 5′-AAGTACTGGCATGGCCAGTGA | |

| mCCTβ3-Forward | 5′-GGGCCAAACCTTGTGGTACA | 6FAM-AATTCGTCCTTGTCCATGCTGCAT-TAMRA |

| mCCTβ3-Reverse | 5′-TGCAGTCAGGGTCTTGCGT | |

| mPEMT-Forward | 5′-GGCATCTGCATCCTGCTTTT | 6FAM-CTCCGCTCCCACTGCTTCACAC-TAMRA |

| mPEMT-Reverse | 5′-TTGGGCTGGCTCACTATAGC |

6FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein; TAMRA, tetramethyl carboxy rhodamine.

CCT enzyme activity.

CCT activities in murine tissues of adult Pcyt1a+/+ and Pcyt1a+/− mice were determined essentially as described previously (12). Selected organs from Pcyt1a+/+ and Pcyt1a+/− mice were lysed in a Dounce homogenizer and cold 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 5 mM Na2EDTA, 1 μM Na3VO4, 5 mM NaF, 2% aprotinin, 10 μg of leupeptin/ml, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The lysate was centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to remove large debris. Protein concentration was determined according to the method of Bradford using gamma globulin as a standard (3). The standard assay mixture contained 150 mM bis-Tris-HCl (pH 6.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 4 mM CTP, 100 μM lipid vesicles (PtdCho:oleic acid, 1:1), and 1 mM phospho[methyl-14C]choline (American Radiolabeled Chemicals; specific activity, 4.5 mCi/mmol) in a final volume of 50 μl. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 5 μl of 0.5 M Na2EDTA, and the tubes were vortexed and placed on ice. Next, 40 μl of each sample was spotted onto a preadsorbent silica gel G thin-layer plate (Analtech), which was developed in 2% ammonium hydroxide, 95% ethanol (1:1, vol/vol). CDP-[methyl-14C]choline was identified by comigration with authentic radiolabeled standard (American Radiolabeled Chemicals). CCT activity was calculated from a series of assays that were linear with time and protein.

Metabolic labeling.

Fresh livers were harvested from adult Pcyt1a+/+ and Pcyt1a+/− mice, rinsed in buffer containing 66.7 mM NaCl, 6.7 mM KCl, 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), and 36 mM glucose, and chopped with a Mcllwain tissue chopper (The Vibratome Company, O'Fallon, Mo.). The minced tissue was digested in the same buffer plus 5 mM CaCl2 · 2H2O, collagenase (0.5 mg/ml), and DNase (6 μg/ml) for 20 min at 37°C three times successively. The debris was allowed to settle each time, and the supernatant containing the cell suspension was collected. After filtering the combined cell suspension through 41-μm Spectra/Mesh nylon (Fisher Scientific), the hepatocytes in the filtrate were collected by centrifugation at 100 × g for 2 min and washed three times with buffer containing 137 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.65 mM Mg2SO4 · 7H2O, 1.2 mM CaCl2 · 2H2O, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), and 15 mg of bovine serum albumin/ml. The cells were resuspended in 10 ml of Dulbecco's PBS containing 5 mM glucose and 3.3 mM pyruvate plus 0.5% bovine serum albumin. Cells were counted using a hemocytometer, and viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion. Cells were incubated at 37°C with aeration and gentle mixing in the same buffer with 3 μCi of [methyl-3H]choline/ml for up to 6 h. After incubation, cells were transferred to ice and washed three times with PBS, and the cell pellets were extracted using a two-phase system (1) to separate the chloroform-soluble metabolites. The amount of radiolabel incorporated into PtdCho (>95% of the total) in the organic phase was determined by scintillation counting.

Lipid determinations.

Flash-frozen liver or lung tissue was thawed and weighed, and approximately 50 mg was extracted by the method of Bligh and Dyer (1). The organic phase containing lipid was concentrated under nitrogen and resuspended in 400 μl of chloroform-methanol (2:1). A 1-μl aliquot was loaded onto a thin-layer silica gel rod, developed first in ether, dried, and then developed in chloroform-methanol-acetic acid-water (50:25:8:3) for phospholipid determinations or hexane-ethyl ether-acetic acid (80:20:0.5) for neutral lipid determinations. Lipid mass was detected by flame ionization using an Iatroscan instrument (Iatron Laboratories, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) with PEAK SIMPLE software (SRI Instruments), and peaks were identified by comigration with authentic standards. PtdCho mass was calculated using a standard curve prepared with egg PtdCho (Matreya, Inc.).

RESULTS

Targeted disruption of the Pcyt1a gene results in early embryonic lethality.

Pcyt1a+/− mice were intercrossed to obtain Pcyt1a−/− mice, and we investigated the phenotype associated with homozygous CCTα deficiency. The genotypes of the offspring were determined by PCR analysis of tail DNA at age 3 weeks. From 120 pups total, 40 were wild type and 80 were heterozygous, but no homozygous mutant mice were obtained (Table 2) and no neonatal deaths occurred. These data suggested that Pcyt1a gene deficiency caused embryonic lethality. To determine the time of embryonic death, timed-pregnant mice were euthanized at day E11.5, embryos were removed, and embryonic DNA was analyzed for the presence of wild-type and deleted Pcyt1a genes. Of 60 embryos analyzed, 19 were wild type and 41 were heterozygous for the Pcyt1a deletion, but no Pcyt1a−/− embryos were identified (Table 2). Thus, Pcyt1a−/− embryos appeared to die before day E11.5. To identify further the time of embryonic death, timed matings were done and day E3.5 preimplantation embryos were isolated by flushing the uterine horns. Analysis of the embryonic DNA by PCR followed by Southern blotting demonstrated the presence of 10 Pcyt1a−/− embryos out of 44 total. We noted that all of the homozygous Pcyt1a−/− embryos exhibited retarded development at day E3.5. Whereas the vast majority of both wild-type and heterozygous embryos were blastocysts composed of a hollow trophoectoderm surrounding a fluid-filled cavity, with a small group of internal cavity mass cells as expected, 100% of the homozygous mutant embryos failed to form blastocysts. These results indicated that targeted disruption of both Pcyt1a alleles caused delayed or abnormal embryonic development prior to implantation. To determine whether homozygous knockout embryos became implanted in the uterus, we isolated day E8.5 embryos with surrounding yolk sacs from pregnant Pcyt1+/− dams and found neither homozygous mutant embryos nor evidence of uterine resorption of embryos. The data support the conclusion that Pcyt1a−/− embryos did not develop successfully beyond the preimplantation stage.

TABLE 2.

Genotypes of offspring from intercrosses of Pcyt1a+/− mice

| Agea | No. with genotype

|

No. resorbedb | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | +/− | −/− | |||

| E3.5 | 12 | 22 | 10 | NA | 44 |

| Blastocystc | 9 | 21 | 0 | NA | 30 |

| Morulac | 3 | 1 | 10d | NA | 14 |

| E8.5 | 7 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 24 |

| E11.5 | 19 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 60 |

| 3 wks | 40 | 80 | 0 | NA | 120 |

Animals from intercrosses of CCTα+/− mice were collected at E3.5, E11.5, or 3 weeks after birth, and the genotypes were determined by PCR or PCR followed by Southern blotting as described in Materials and Methods.

The uterus was examined for evidence of resorbed embryos. NA, not applicable.

Genotypes were determined by PCR analysis followed by Southern blotting as described in Materials and Methods.

The Pcyt1a−/− embryos did not have normal morphology.

Pcyt1a gene expression is dominant at day E11.5.

RNA in situ hybridization of frozen sagittal sections at day E11.5 of murine gestation showed widespread expression of CCTα encoded by the Pcyt1a gene throughout the mouse embryo (Fig. 1A), and a particularly high level of CCTα expression was observed in the liver. There was more restricted expression of CCTβ (Fig. 1D) encoded by the Pcyt1b gene compared to that of CCTα. CCTβ2 and -β3 expression could not be distinguished from each other using this technique, because the optimum probe size necessitated that the 3′-untranslated portion of the transcripts be used to signal the α and β isoforms and this region is identical for the β2 and β3 species. PEMT transcripts were also investigated, since this enzyme catalyzes a reaction significant for PtdCho biosynthesis in liver (21) and was found to be expressed at a very low level in E11.5 embryos (Fig. 1C). The negative control (background) showed no signal on the tissue, whereas the PEMT showed barely detectable levels above background. Using a different approach, quantitative real-time PCR showed that CCTα transcripts in wild-type E11.5 embryos constituted 77%, whereas CCTβ2 made up approximately 11%, CCTβ3 transcripts were 2%, and PEMT made up 10% of the four transcripts (Fig. 1B). These data support the in situ hybridization results, demonstrate that Pcyt1a gene expression is dominant at day E11.5 in wild-type embryos, and support a role for CCTα expression during embryonic development beyond the blastocyst stage.

Disruption of one Pcyt1a allele adjusts CCTβ and PEMT expression.

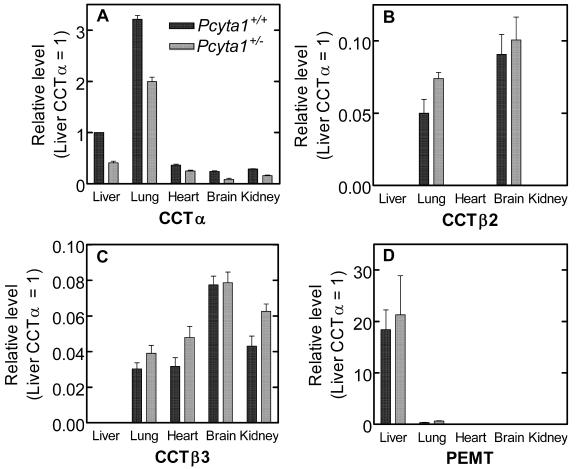

The heterozygous Pcyt1a+/− embryos and adult mice did not exhibit an apparently different phenotype compared to wild-type littermate controls. Therefore, we investigated the relative expression of the CCT transcripts in day E11.5 embryos (Fig. 1D) as well as multiple adult tissues (Fig. 2) by quantitative real-time PCR to determine if expression of alternate genes compensated for the Pcyt1a reduced gene dosage. The value for CCTα expression in the Pcyt1a+/+ embryos was set at 1.0, and in the Pcyt1a+/− embryos CCTα was expressed at approximately 0.7 times the amount found in the wild type. The expression of CCTβ2, CCTβ3, and PEMT increased at least twofold in the heterozygous embryos in response to reduced CCTα expression. On the other hand, reduction of CCTα expression in Pcyt1a+/− adult liver, lung, heart, brain, or kidney did not elicit an increase in the expression of the alternative transcripts (Fig. 2), suggesting that the lower CCTα expression in adult heterozygotes was sufficient for maintaining PtdCho production via the CDP-choline pathway. The general distribution of transcripts in wild-type adult animals was consistent with previously measured values (9). CCTβ2, CCTβ3, and PEMT transcripts were considerably lower overall in the adult animals (Fig. 2) compared to their relative expression in embryos (Fig. 1D), suggesting that these genes play a larger role in embryo development, with the exception of the PEMT in adult liver. We cannot evaluate how much the slight, and perhaps insignificant, elevation of CCTβ expression contributes to total PtdCho production in adult tissues, but the data suggest that CCTα expression is sufficient in the Pcyt1a+/− animals, since there are no overt phenotypic differences compared to wild type.

FIG. 2.

Relative abundance of the CCT isoforms and PEMT transcripts in tissues from adult wild-type and Pcyt1a+/− mice. Selected organs were removed from Pcyt1a+/+ and Pcyt1a+/− mice. RNA was isolated from liver, brain, heart, kidney, and lung of three mice of each gender individually, and each RNA sample was quantified in quintuplicate. Primers and probes for expression of CCTα (A), CCTβ2 (B), CCTβ3 (C), and PEMT (D) are listed in Table 1. All of the real-time values for each tissue were averaged and compared using the CT method, where the amount of target RNA (2−ΔΔCT) is normalized to the endogenous GAPDH reference (ΔCT) and related to the amount of target CCTα in liver from Pcyt1a+/+ mice (ΔΔCT), which was set as the calibrator at 1.0.

PtdCho biosynthesis in tissues.

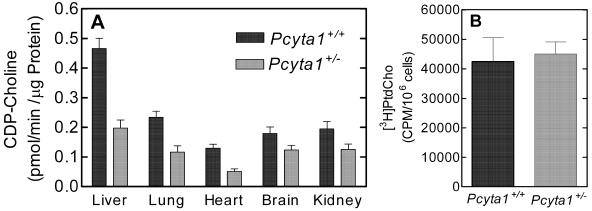

The biochemical consequence of disruption of one Pcyt1a allele on CCTα protein and enzyme activity was determined by measuring the CCT specific activity in tissue lysates (Fig. 3A) and in intact hepatocytes isolated from wild-type and heterozygous mice (Fig. 3B). Within each tissue, the activity from Pcyt1a+/− mice decreased significantly, by about 50% in most tissues compared with Pcyt1a+/+ littermate controls (Fig. 3A). Whereas the lung had a higher CCTα transcript abundance than the liver, the CCT enzyme specific activity was higher in liver compared to lung, probably due at least in part to normalization of the enzymatic values to total protein content. Real-time PCR values, on the other hand, were normalized to total RNA. Liver is one of the few tissues where CCTβ is not expressed at detectable levels (Fig. 2) (9), and so the reduction in CCT activity, measured using the same optimal conditions, from 0.466 ± 0.034 in wild-type liver to 0.198 ± 0.026 pmol/min/μg of protein (P < 0.0001) in heterozygous liver was truly due to reduction in CCTα protein. On the other hand, the total CCT activity in brain did not decrease significantly (P = 0.07) in the Pcyt1a+/− mice, suggesting that the relatively high level of CCTβ expression in this organ (9) compensated for the loss of one active CCTα allele. Livers from a total of three mice of each sex and each genotype were included in the determination. There was no difference between males and females within a genotype, and so the values were combined and averaged.

FIG. 3.

Effect of targeted disruption of the Pcyt1a gene on hepatic PtdCho synthesis in wild-type and heterozygous mice. (A) CCT enzyme specific activity was determined in adult mouse tissue lysates and normalized to protein content as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Radiolabeling of PtdCho in hepatocytes derived from Pcyt1a+/+ and Pcyt1a+/− mice. Hepatocytes (2 × 106 per sample per animal) were incubated in Dulbecco's PBS containing glucose and pyruvate for 6 h with [methyl-3H]choline (3 μCi/ml). Radiolabeled PtdCho was extracted from cells and quantified as described in Materials and Methods. The results shown are the average values obtained using hepatocytes from six animals of each genotype.

Liver did not express detectable levels of CCTβ, and so we determined whether the significant reduction of CCTα protein would alter the rate of PtdCho synthesis in primary hepatocytes isolated from heterozygous animals. Hepatocytes were isolated from Pcyt1a+/− and Pcyt1a+/+ mice and incubated with [3H]choline to estimate the rate of PtdCho synthesis in vivo (Fig. 3B). Incorporation into PtdCho was linear from 2 to 6 h and, surprisingly, there was no statistical difference between the heterozygous livers and those from wild-type animals, i.e., 4.0 × 104 cpm versus 5.0 × 104 per 106 viable cells after 6 h of incubation. The data certainly did not reflect the approximate 50% difference in lysate specific activity noted above (Fig. 3A), but the results explained the lack of phenotypic distinction between heterozygous and wild-type animals. There was no difference in the metabolic labeling results between the sexes, and thus the values are the averages of a total of six independent determinations from each genotype, i.e., hepatocytes from three males and three females. These results indicated that the amount of CCT activity in wild-type cells was more than sufficient to maintain physiological PtdCho production and that CCT activity was biochemically regulated in cells to maintain PtdCho synthesis at homeostatic levels. Tissue lipids were quantified in Pcyt1a+/− and Pcyt1a+/+ mice and did not exhibit a substantive change in PtdCho content in liver (32.5 ± 4.8 and 35.57 ± 1.69 μg/mg [wet weight], respectively), consistent with the metabolic labeling results. The highest relative CCTα expression was previously found in lung, where CCTβ expression was roughly 40 times lower (9), and so we examined if the PtdCho content of this organ was more sensitive to the reduction in CCTα gene expression. There was a small but significant reduction in the PtdCho content of Pcyt1a+/− animals (19.18 ± 2.54 in Pcyt1a+/− compared to 23.19 ± 1.74 μg/mg [wet weight] in Pcyt1a+/+; P < 0.01), but the other lipids, i.e., PtdEtn, triglyceride, and cholesterol, did not change.

DISCUSSION

Deletion of CCTα expression in mice revealed its essential role in early embryonic development. The ability of the knockout preimplantation embryos to progress through the first few cell divisions is likely due to the expression of maternal CCTβ that is present at high levels in mature ova (9). Retarded development of the CCTα-deficient embryos is seen at the morula stage, indicating that cell division arrests at an earlier stage. CCT plays a central role in membrane PtdCho synthesis (8) and, although embryonic cell size decreases during preimplantation development, there is an increase in total membrane surface area which requires the activity of CCTα plus CCTβ. These data are consistent with observations in the liver-specific CCTα knockout, where the organ contains fewer hepatocytes than control liver, suggesting that the hepatocytes lacking CCTα do not produce enough PtdCho for normal cell division (10). CCTα expression dominates over CCTβ and PEMT expression during embryogenesis, and CCTα is found throughout the different cell types, with highest expression in liver (Fig. 1). These data are consistent with the very low level of PEMT activity observed in prenatal rat livers (5) and the lack of detectable PEMT pathway activity in E9.5 embryos with impaired CCT activity (7). Although CCTα is reduced in heterozygous embryos, the CCTβ isoforms and PEMT expression both are increased, and so it is difficult to judge whether the level of CCTβ expression alone would be sufficient to support the normal development that is observed.

In contrast to the essentiality of CCTα in embryonic development, CCTα expression is not critical for the function of some adult tissues. Significant reduction of CCTα in heterozygous adult liver does not invoke a compensatory increase in the transcript levels of the CCTβ proteins or PEMT (Fig. 2), nor is there a significant difference in the PtdCho mass compared to that in wild type. Despite a >50% reduction in total CCT enzyme specific activity in heterozygous liver lysates, the metabolic activity of the CDP-choline pathway in isolated hepatocytes was the same as in wild-type hepatocytes (Fig. 3). Furthermore, it was reported previously that homozygous deletion of CCTα in liver does not have a severe phenotype, probably because the PEMT enzyme activity increases in response to CCTα deletion (10). The mild phenotype is found primarily in female mice lacking liver CCTα expression, which have reduced PtdCho and increased triglyceride content (10). In the macrophage-specific CCTα knockout, homozygous deletion of CCTα is accompanied by increased expression of CCTβ, whose activity is sufficient for macrophage development (24). The phenotypic similarity between the heterozygous and wild-type adult mice in this report suggests that the amount of CCTα enzyme in wild-type liver is more than sufficient to maintain PtdCho-associated functions. Reduction of CCTα expression in the lungs of heterozygous animals results in reduced PtdCho content, in contrast to the livers from the same animals. CCTα expression in wild-type lung is comparatively the highest of those tissues examined thus far, with the exception of testis (9), and the lung is a very lipogenic organ, secreting large amounts of disaturated PtdCho as a major component of airway surfactant. Taken together, these data suggest that homozygous deletion of CCTα expression in lung would be very deleterious, and future investigation will determine whether upregulation of CCTβ expression can compensate for the lack of CCTα.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Gunter and Daren Hemingway for expert technical assistance in enzyme assays and lipid analyses, Pam Jackson for primer and probe designs, and Chuck Rock for discussion and interest.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM 45737 (to S.J.), Cancer Center (CORE) support grant CA 21765, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bligh, E. G., and W. J. Dyer. 1959. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37:911-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boggs, K. P., C. O. Rock, and S. Jackowski. 1995. Lysophosphatidylcholine and 1-O-octadecyl-2-O-methyl-rac-glycero-3-phosphocholine inhibit the CDP-choline pathway of phosphatidylcholine synthesis at the CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase step. J. Biol. Chem. 270:7757-7764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cui, Z., M. Houweling, M. H. Chen, M. Record, H. Chap, D. E. Vance, and F. Tercé. 1996. A genetic defect in phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis triggers apoptosis in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271:14668-14671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cui, Z., Y.-J. Shen, and D. E. Vance. 1997. Inverse correlation between expression of phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase-2 and growth rate of perinatal rat livers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1346:10-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esko, J. D., M. M. Wermuth, and C. R. H. Raetz. 1981. Thermolabile CDP-choline synthetase in an animal cell mutant defective in lecithin formation. J. Biol. Chem. 256:7388-7393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher, M. C., S. H. Zeisel, M. H. Mar, and T. W. Sadler. 2002. Perturbations in choline metabolism cause neural tube defects in mouse embryos in vitro. FASEB J. 16:619-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackowski, S., and P. Fagone. 2005. CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase: paving the way from gene to membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 280:853-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackowski, S., J. E. Rehg, Y.-M. Zhang, J. Wang, K. Miller, P. Jackson, and M. A. Karim. 2004. Disruption of CCTβ2 expression leads to gonadal dysfunction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:4720-4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs, R. L., C. Devlin, I. Tabas, and D. E. Vance. 2004. Targeted deletion of hepatic CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase α in mice decreases plasma high density and very low density lipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 279:47402-47410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karim, M. A., P. Jackson, and S. Jackowski. 2003. Gene structure, expression and identification of a new CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase beta isoform. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1633:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luche, M. M., C. O. Rock, and S. Jackowski. 1993. Expression of rat CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase in insect cells using a baculovirus vector. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 301:114-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lykidis, A., I. Baburina, and S. Jackowski. 1999. Distribution of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CCT) isoforms. Identification of a new CCTβ splice variant. J. Biol. Chem. 274:26992-27001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lykidis, A., K. G. Murti, and S. Jackowski. 1998. Cloning and characterization of a second human CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:14022-14029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noga, A. A., Y. Zhao, and D. E. Vance. 2002. An unexpected requirement for phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase in the secretion of very low density lipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 277:42358-42365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramos, B., M. El Mouedden, E. Claro, and S. Jackowski. 2002. Inhibition of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase by C2-ceramide and its relationship to apoptosis. Mol. Pharmacol. 62:1068-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rice, D. S., M. Sheldon, G. D'Arcangelo, K. Nakajima, D. Goldowitz, and T. Curran. 1998. Disabled-1 acts downstream of Reelin in a signaling pathway that controls laminar organization in the mammalian brain. Development 125:3719-3729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simmons, D. M., J. L. Arriza, and L. W. Swanson. 1989. A complete protocol for in situ hybridization of messenger RNAs in brain and other tissues with radiolabeled single-stranded RNA probes. J. Histotechnol. 12:169-181. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vance, D. E., C. J. Walkey, and Z. Cui. 1997. Phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase from liver. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1348:142-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vance, J. E., and D. E. Vance. 2004. Phospholipid biosynthesis in mammalian cells. Biochem. Cell Biol. 82:113-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walkey, C. J., L. Yu, L. B. Agellon, and D. E. Vance. 1998. Biochemical and evolutionary significance of phospholipid methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 273:27043-27046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, Y., J. I. S. MacDonald, and C. Kent. 1995. Identification of the nuclear localization signal of rat liver CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 270:354-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, Y., T. D. Sweitzer, P. A. Weinhold, and C. Kent. 1993. Nuclear localization of soluble CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 268:5899-5904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang, D., W. Tang, P. M. Yao, C. Yang, B. Xie, S. Jackowski, and I. Tabas. 2000. Macrophages deficient in CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase-α are viable under normal culture conditions but are highly susceptible to free cholesterol-induced death. Molecular genetic evidence that the induction of phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis in free cholesterol-loaded macrophages is an adaptive response. J. Biol. Chem. 275:35368-35376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]