Abstract

Macrophages clear infections by engulfing and digesting pathogens within phagolysosomes. Pathogens escape this fate by engaging in a molecular arms race; they use WxxxE motif–containing “effector” proteins to subvert the host cells they invade and seek refuge within protective vacuoles. Here, we define the host component of the molecular arms race as an evolutionarily conserved polar “hot spot” on the PH domain of ELMO1 (Engulfment and Cell Motility protein 1), which is targeted by diverse WxxxE effectors. Using homology modeling and site-directed mutagenesis, we show that a lysine triad within the “patch” directly binds all WxxxE effectors tested: SifA (Salmonella), IpgB1 and IpgB2 (Shigella), and Map (enteropathogenic Escherichia coli). Using an integrated SifA–host protein–protein interaction network, in silico network perturbation, and functional studies, we show that the major consequences of preventing SifA–ELMO1 interaction are reduced Rac1 activity and microbial invasion. That multiple effectors of diverse structure, function, and sequence bind the same hot spot on ELMO1 suggests that the WxxxE effector(s)–ELMO1 interface is a convergence point of intrusion detection and/or host vulnerability. We conclude that the interface may represent the fault line in coevolved molecular adaptations between pathogens and the host, and its disruption may serve as a therapeutic strategy.

Keywords: ELMO1, Rac1, Dock180, SifA, engulfment, Salmonella, WxxxE effectors

Enteric pathogens such as Salmonella rely upon their virulence factors to invade and replicate within host cells. Upon invasion, they seek refuge within a modified phagosome-like structure, the Salmonella-containing vacuole (SCV) (1), within which they survive, even replicate, or simply persist in a dormant-like state (2). Both invasion and SCV formation require the delivery of microbial effector proteins via type III secretion systems (T3SSs) into the host cell; they both require the cooperation of a subverted host cell whose phagolysosomal signaling and membrane trafficking pathways are manipulated to mount very dynamic and extensive membrane remodeling and actin rearrangement (1). Thus, three key aspects facilitating Salmonella pathogenesis are (i) vacuole formation for refuge, (ii) delivery of effector proteins via T3SSs to interfere and/or manipulate the host system, facilitating (iii) more bacterial invasion. These mechanisms of pathogenesis are shared also among other enteric pathogens such as enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, enterohemorrhagic E. coli, and Shigella. E. coli rely upon T3SS effectors—for example, Map, EspH, and EspF—to form E. coli-containing vacuoles (3) and manipulate the host cell into forming pedestals (4), filopodia, or microspikes for invasion, whereas Shigella rely upon T3SS effectors, for example, IpgB1/2, to form vacuoles (5) and manipulate host cells into forming membrane ruffles for orchestrating what is known as “the trigger mechanism of entry” (6, 7, 8, 9). Similar mechanisms are also used by Yersinia (10) and Campylobacter (11) to subvert host epithelial cells.

Regardless of the diversity of the pathogens, their equally diverse T3SS injectosomes, or the repertoire of effectors (reviewed in Ref. (12)), the host actin cytoskeleton has emerged as the dynamic hub in a microbe-induced circuitry of Ras-superfamily GTPases (Ras homolog family member A [RhoA], Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 [Rac1], and cell division control [Cdc] protein-42) (13). Diverse microbes converge upon and exploit this host circuitry to mount pathogenic signaling, escape lysosomal clearance by seeking refuge in vacuoles, invade host cells, and alter inflammatory response. As for mechanism(s) for such convergence, the ability of a WxxxE motif–containing family of effectors to directly activate host GTPases was reported first (14). By activating host Rho GTPases, the WxxxE effectors subvert actin dynamics (15). SopE, IpgB1, and EspT trigger membrane ruffles (16, 17, 18), IpgB2 and EspM trigger stress fibers (19), and Map triggers filopodia (20) via activation of Rac1, RhoA, and Cdc42, respectively. Engulfment and cell Motility protein 1 (ELMO1) was identified subsequently as a WxxxE effector–interacting host protein (21). Three independent groups, each using ELMO1-knockout animals that were infected with different pathogens (Shigella (6), Salmonella (21), and E. coli (22)), have implicated the WxxxE–ELMO1 interaction in the augmentation of the actin–GTPase circuitry via the well-established ELMO1–DOCK180 (dedicator of cytokinesis)→Rac1 axis (23, 24, 25). Within this signaling cascade, ELMO1–Dock180 is not only a bipartite guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the monomeric GTPase Rac1 (26) but is also capable of activating Cdc42 (27) and RhoA (28).

Despite these insights, key questions remained unanswered; for example, how do the WxxxE effectors, which are unique to gut pathogens (21) [yet to be found in commensals (29)] converge on one host macromolecular complex (the ELMO1–Dock180→RhoGTPases) to subvert host actin dynamics. Because the WxxxE effectors are structurally and functionally diverse except for the WxxxE motif, which is their defining and unifying feature, initial studies hypothesized that this motif could be the mechanism of such convergence; but four structural studies revealed otherwise (26, 30, 31, 32). Resolved structures of SifA, IpgB, and Map and a homology model of EspM2 showed that Trp (W) and Glu (E) within the WxxxE motif are “structural residues” that are positioned around the junction of the two 3-α-helix bundles and maintain the conformation of a “catalytic loop” through hydrophobic contacts with surrounding residues. Consistent with these conclusions, conserved substitutions [W→Y and E→D; in EpsM (19)] did not alter stability or functions, whereas W→A or E→A substitutions make the protein highly unstable (33) and render it nonfunctional (34). With the WxxxE motif “ruled out” as the potential contact site for convergence, the basis for how diverse WxxxE effectors may bind ELMO1 and induce convergent pathogenic signaling via the ELMO1–DOCK axis remains unknown. Using a transdisciplinary and multiscale approach that spans structural models as well as protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks, here we reveal a surprisingly conserved molecular mechanism for how diverse pathogens use their WxxxE effectors to hijack the ELMO1–DOCK–Rac1 axis via a singular point of vulnerability on ELMO1.

Results and discussion

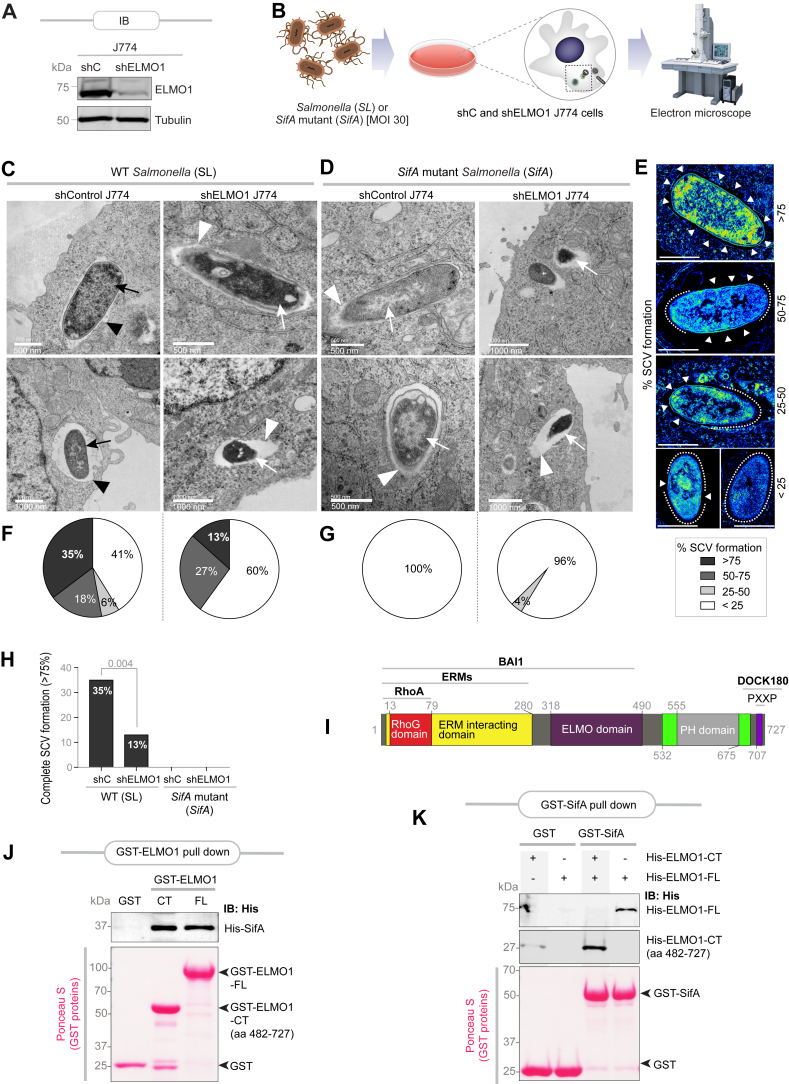

ELMO1 and SifA cooperate during vacuole formation

Prior work has separately implicated both ELMO1 (35) and SifA (32, 36, 37) in Salmonella pathogenesis. While SifA has been directly implicated in the formation of SCVs (32, 37), ELMO1 was shown to impact bacterial colonization, dissemination, and inflammatory cytokines in vivo (21). We asked if both proteins are required for SCV formation. We stably depleted ELMO1 in J774 macrophages by shRNA (>99% depletion compared with controls; Fig. 1A), infected them with either the WT (SL) or a mutant Salmonella strain that lacks SifA (ΔSifA), and then assessed the ultrastructure of the SCVs by transmission electron microscopy (see workflow; Fig. 1B). Bacteria were observed as either intact within vacuoles, free in cytosol, or partially digested within fused lytic compartments, as reported previously (38) (Fig. 1, C and D). When assessed for the completeness of the vacuolar wall (see basis for quantification; Fig. 1E), WT Salmonella formed complete SCVs at a significantly lower rate in ELMO-depleted macrophages compared with controls (13% versus 35%; Fig. 1, F and H). The absence of SifA impaired SCV biogenesis regardless of the presence or absence of ELMO1 (Fig. 1, G and H). Findings demonstrate that both ELMO1 and SifA are required for SCV formation and suggest cooperativity between the two proteins during SCV biogenesis.

Figure 1.

ELMO1 and SifA interact directly and cooperate to promote SCV formation.A, immunoblot of control (shC) and ELMO1-depleted (shELMO1) J774 murine macrophages. B, schematic shows workflow for TEM on J774 macrophages infected with either Salmonella (SL) or an SifA-deleted variant strain (SifA) of the same. C and D, representative electron micrographs of control (shC) or ELMO1-depleted (shELMO1) J774 macrophages, infected with Salmonella typhimurium (SL or SifA; 30 MOI), at 6 h postinfection. Examples of bacteria within vacuoles (black arrowheads) and cytosolic bacteria (white arrowheads) are indicated. Bacteria that are either intact (black arrows) or partially degraded upon fusion with lytic compartments (white arrows) are also indicated. Scale bars are placed at the lower left corner of each micrograph. E–G, a montage (E) of pseudo-colored micrographs of SCVs at various stages of formation is shown. The presence (arrowheads) or absence (interrupted lines) of detectable vacuolar membrane are marked. The top panel (>75%) is derived from the “top-left side” image in the “shControl J774” column in 1C. The “50 to 75” pseudo-colored micrograph image (second from the top) is derived from the “lower-left side” image in the “shControl J774” column in (C). The “<25” pseudo-colored micrograph image in the lower-right side corner in (E) is derived from the “top-right side” image in the “shELMO J774” column in (D). Scale bars represent 1000 nm. Pie charts display the percentage of bacteria at each stage of SCV formation (F and G) encountered in (C and D). H, bar graph displays the percentage of complete (representing >75% in E) SCV formation in (C and D). I, a domain map of ELMO1 with major interacting partners. J, recombinant His-SifA (∼5 μg) was used in a pulldown assay with immobilized bacterially expressed recombinant GST-tagged full-length (FL) or a C-terminal domain (CT; amino acids 482–727) of ELMO1 or GST alone (control). Bound SifA was visualized by immunoblot using anti-His (SifA) antibody. GST proteins are visualized by Ponceau S staining. K, recombinant His-tagged CT (amino acids 482–727) or FL ELMO1 proteins (∼3 μg) were used in a pulldown assay with immobilized bacterially expressed recombinant full-length GST-SifA or GST alone (control). Bound ELMO1 proteins were visualized by immunoblot using anti-His (ELMO1) antibody. GST proteins are visualized by Ponceau S staining. BAI1, Brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor 1 (ADGRB1); ELMO1, Engulfment and Cell Motility protein 1; ERM proteins, ezrin, radixin, and moesin; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; MOI, multiplicity of infection; SCV, Salmonella-containing vacuole; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

SifA directly binds the C terminus of ELMO1

We next asked if SifA binds ELMO1; the latter is a multimodular protein with several known interacting partners (summarized in Fig. 1I). We compared head-to-head equimolar amounts of glutathione-S-transferase–tagged full length versus a C-terminal fragment (amino acids 482–727) of ELMO1 (which contains a Pleckstrin-like homology domain [PHD]; Fig. 1I) for their ability to bind a His-tagged recombinant SifA protein. The C-terminal PH domain was prioritized because of two reasons: (i) a recent domain mapping effort using fragments of ELMO1 on cell lysates expressing SifA had ruled out contributions of the N-terminal domain in mediating this interaction (21) and (ii) SifA directly binds another PHD, SKIP, forming 1:1 complex at micromolar dissociation constant, the structural basis for which has been resolved (26, 39). We found that both full-length ELMO1 and its C-terminal fragment can bind His-SifA (Fig. 1J). Binding was also observed when the bait and prey proteins were swapped, such that immobilized glutathione-S-transferase-SifA was tested for its ability to bind His-ELMO1 proteins (Fig. 1K). Because interactions occurred between recombinant proteins purified to >95% purity, we conclude that the SifA–ELMO1 interaction is direct. Because SifA bound both the full-length and the C-terminal fragment of ELMO1 to a similar extent, we conclude that the C terminus of ELMO1 is sufficient for the interaction.

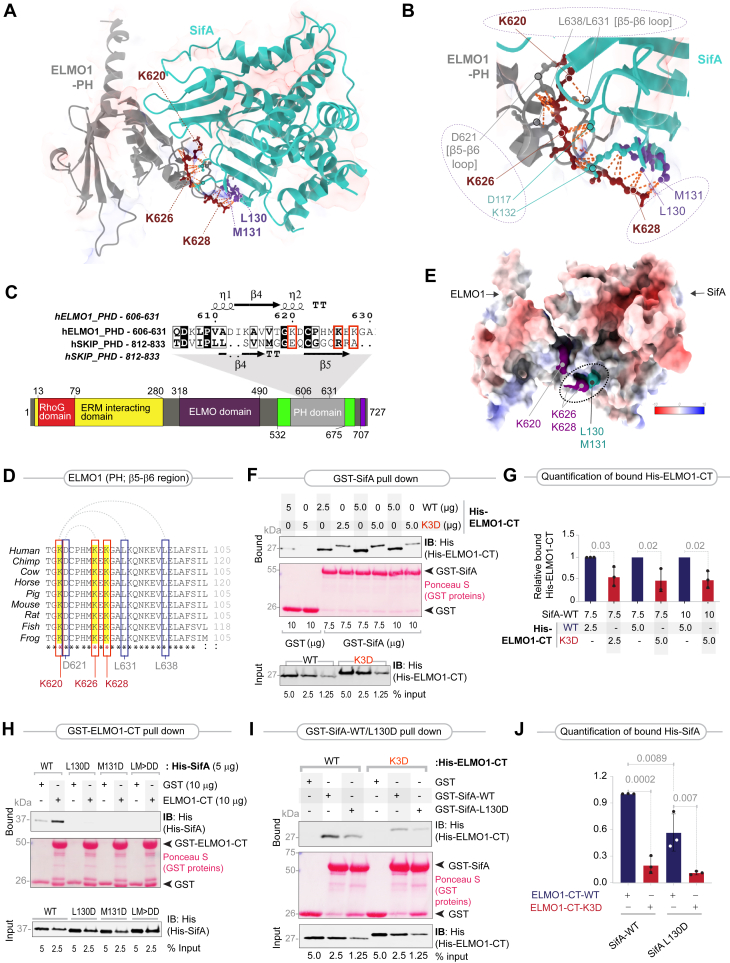

SifA binds to an evolutionarily conserved lysine hot spot on the PHD of ELMO1

To gain insights into the nature of the SifA–ELMO1 interface, we leveraged two previously resolved structures of a SifA–SKIP (PHD) cocomplex (32) and ELMO1 (PHD) to build a homology model of SifA–ELMO1 (PHD) complex (see Fig.S1, A and B for workflow and the Experimental procedures section). The resultant model helped draw three key important conclusions: (i) the resolved structure of SifA–SKIP (32) and the model for SifA–ELMO1 were very similar, and hence, the specific recognition of SifA by both SKIP (PHD) and ELMO1 (PHD) was predicted to be mediated through a large network of contacts (Fig. 2A), primarily electrostatic in nature (Fig.S1, C and D); (ii) the tryptophan (W197, deeply buried within the hydrophobic core of SifA) and glutamate (E201) within the WxxxE motif (red residues; Fig. S2), which are essential for protein stability, but dispensable for binding SKIP (26), are likely to be nonessential also for ELMO1; and (iii) the amino acids deemed essential for the assembly of the SifA–ELMO1 interface were a pair of hydrophobic residues, leucine (L)130 and methionine (M)131 on SifA and a triad of polar lysine residues within the β5–β6 loop of ELMO1 (K620, K626, and K628) (Fig. 2, A and B). An alignment of the sequences of ELMO1 (PHD) and SKIP (PHD) showed that the lysine triad in ELMO1 corresponds to the corresponding contact sites on SKIP for SifA in the resolved complex (26) (Figs. 2C and S3A). A full catalog of both intermolecular and intramolecular contact sites (Supporting Information Data 1) revealed how each lysine within the lysine triad in the β5–β6 loop of ELMO1 contributes uniquely to generate the electrostatic attractions that stabilize the SifA–ELMO1 complex (Fig. 2B): (i) K628 primarily establishes intermolecular electrostatic contacts with L130 and M131 on SifA; (ii) K626 mediates intermolecular interaction by engaging K132 and also via charge-neutralizing salt bridges with Asp(D)117 on SifA. It also mediates intramolecular interactions with D621 within the β5–β6 loop of ELMO1; (iii) K620 primarily engages in intramolecular contact with two other residues within the β5–β6 loop, L631 and L638, thus stabilizing the loop. Thus, all three lysines within the triad appeared important: While K628 and K626 establish strong electrostatic interactions with SifA, K626 and K620 stabilize the β5–β6 loop that contains the lysine triad.

Figure 2.

Characterization of the ELMO1–SifA interface.A, homology model of the ELMO1 (gray)–SifA (turquoise) complex, generated by superimposing the solved structure of the ELMO1-PH (PDB code: 2VSZ) on that of the SKIP-PH in complex with SifA (PDB code: 3CXB). The executive RMSD of the model is 1.528 (see Fig. S1 for the workflow used to generate the homology models and select the fittest model with the most optimal parameters). The model is annotated with key amino acids that are predicted to form the interface. On ELMO1, these amino acids were identified as an evolutionarily conserved polar hot spot of three lysines within the β5–β6 loop, and their key intramolecular and intermolecular contacts on SifA are annotated. See Supporting Information Data 1 for a complete catalog of the intermolecular and intramolecular contacts of the highlighted residues. The distance between the residues calculated for contacts was within 4.0 A. See Fig. S2 for the position of the WxxxE motif relative to the ELMO1–SifA interface. B, a magnified view of the key residues participating at the ELMO1 (gray)–SifA (turquoise) interface. Three major clusters of intermolecular and intramolecular interactions of the lysine triad are annotated with interrupted circles/ovals. Lys(K)628 on (ELMO1) primarily engages via strong polar contacts with Met(M)131 and Leu(L)130 on SifA. K626 on (ELMO1) makes an intramolecular contact with D621, a residue within the β5–β6 loop; it is also juxtaposed with K132 and forms a “charge-neutralizing” salt bridge with Asp(D)117 on SifA. K620 on (ELMO1) appears to primarily bind L631 and L638, which are key residues within the β5–β6 loop. C, top, an alignment of the sequences of the PH domains of ELMO1 and SKIP is shown, along with secondary structures. Conserved residues are shaded in black; similar residues are boxed. Three lysine residues on ELMO1 that correspond to the structurally resolved contact sites of SKIP for SifA are marked with red boxes. See also Fig. S3A for an extended alignment. Bottom, a domain map of ELMO1. D, an alignment of the β5–β6 loop of ELMO1 showing that the lysine triad highlighted with red box in (C) is conserved across diverse species. Intraloop interactions are indicated with interrupted arcs on top. Leu(L) and Asp(D) residues that are engaged in these interactions are also conserved and highlighted with blue boxes. See also Fig. S4 for extended alignment. E, the panel displays APBS (Adaptive Poisson–Boltzmann Solver)-derived surface electrostatics for an all-side chain model of the ELMO1–SifA cocomplex, as visualized using Chimera. Volume surface coloring was set in the default range of −10 (red), through 0 (white), to +10 (blue) kT/e, where negatively charged surfaces are red (−10 kT/e) and positively charged surfaces are blue (+10 kT/e). In the most energetically favorable orientation, charged residues Lys(K)628 and Lys(K)626 on (ELMO1) bring hydrophobic residues Met(M)131 and Leu(L)130 on SifA into proximity (marked by an oval). See Fig. S5 for additional views. F, recombinant WT or K3D mutant His-ELMO1-CT proteins (input) were used in pulldown assays with immobilized GST alone or GST-SifA (∼7.5 or 10 μg). Bound ELMO1 was visualized by immunoblotting using an anti-His (ELMO1) antibody. GST proteins are visualized by Ponceau S staining. The K3D mutant displayed slower electrophoretic mobility compared with the WT ELMO1 protein consistently in both reducing and nonreducing gels, and regardless of whether it was expressed in bacteria as recombinant proteins or expressed in mammalian cells, suggesting it is likely to be due to the introduction of negative charge in the form of three aspartates. G, quantification of immunoblots in (F). Results are displayed as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates). Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t test. H, equal aliquots (input) of recombinant His-SifA and its mutants (L130D, M131D, and LM-DD) were used in pulldown assays with immobilized GST alone or GST-ELMO1-CT (10 μg). Bound SifA proteins were visualized by immunoblotting using an anti-His antibody. GST proteins are visualized by Ponceau S staining. I, recombinant WT or K3D mutant His-ELMO1-CT proteins were used in pulldown assays with GST or GST-SifA (WT or L130D mutant). Bound ELMO1 was visualized by immunoblotting using an anti-His antibody. GST proteins are visualized by Ponceau S staining. J, quantification of immunoblots in (I). Results are displayed as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates). Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t test. ELMO1, Engulfment and Cell Motility protein 1; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; PDB, Protein Data Bank.

We noted that K620 is reported to be ubiquitinated, and the threonine (T) at 618 is phosphorylated (Fig. S3B); none of the lysine residues are reported to be impacted by germline SNPs or somatic mutations in cancers. Most importantly, the β5–β6 loop and the lysine triad within this stretch are evolutionarily conserved from fish to humans, as well as in the homologous members of the family, ELMO2 and ELMO3 (Figs. 2D and S4).

To analyze the electrostatics for the model of the SifA–ELMO1 complex, we used Adaptive Poisson–Boltzmann Solver (40), a widely accepted software for solving the equations of continuum electrostatics for large biomolecular assemblages. We found that in the most energetically favorable orientation, charged residues Lys(K)628 and Lys(K)626 on ELMO1 bring hydrophobic residues Met(M)131 and Leu(L)130 on SifA into proximity (Figs. 2E and S5). Because the Adaptive Poisson–Boltzmann Solver approach allows us to determine the electrostatic interaction profile as a function of the distance between two molecules, we conclude that the lysines K628 and K626, and potentially other amino acids in the β5–β6 loop, are key sites on ELMO1 that engage in electrostatic interactions with L130 and M131 on SifA.

We validated the homology model and the nature of the major interactions (i.e., electrostatic) in the assembly of the complex by generating several structure-rationalized mutants of ELMO1 and SifA. On ELMO1, the positively charged lysines were substituted with negatively charged aspartate residues (D; ELMO1-CT-K3D), expecting that such substitution will disrupt the intermolecular electrostatic attractions and destabilize the SifA–ELMO1 complex. These substitutions were expected to also disrupt intramolecular interactions within the β5–β6 loop (Fig. 2D) and destabilize the highly conserved loop. Mutation of the individual lysines within the patch was not pursued because their relative contributions to the intermolecular interaction were likely to be confounded by their ability to stabilize each other on the β5–β6 loop. On SifA, the hydrophobic residues L130 and M131 were substituted with an unfavorable negatively charged and polar aspartate residue, either alone (L130D; M131D) or in combination (LM>DD). Binding to SifA was significantly reduced in the case of the K3D ELMO1 mutant (Fig. 2, F and G), and binding to ELMO1 was virtually abolished in the case of all the SifA mutants (Fig. 2H).

Although both L130 and M131 on SifA were predicted to bind ELMO1, L130 was predicted to be the major contributor (accounting for 13 of the 17 intermolecular contact sites; Supporting Information Data 1). M131, on the other hand, engaged also in numerous intramolecular contacts, which suggests that M131 could be important also for protein conformation. We asked if the strong polar contacts between L130(SifA) and the lysine triad (ELMO1) were critical for the SifA–ELMO1 interaction (Fig. 2B) and tested their relative contributions without disrupting M131(SifA). Pulldown assays showed that SifA–ELMO1 interactions were partially impaired when L130D-SifA and K3D-ELMO1 substitutions when used alone (Fig. 2, I and J) and virtually lost when the mutants were used concomitantly (Fig. 2, I and J).

These findings provide atomic level insights into the nature and composition of the SifA–ELMO1 complex, which is assembled when a pair of hydrophobic residues on SifA binds an evolutionarily conserved polar hot spot on ELMO1 (PHD). Strong hydrophobic interactions stabilize the SifA–ELMO1 interface, which can be selectively disrupted.

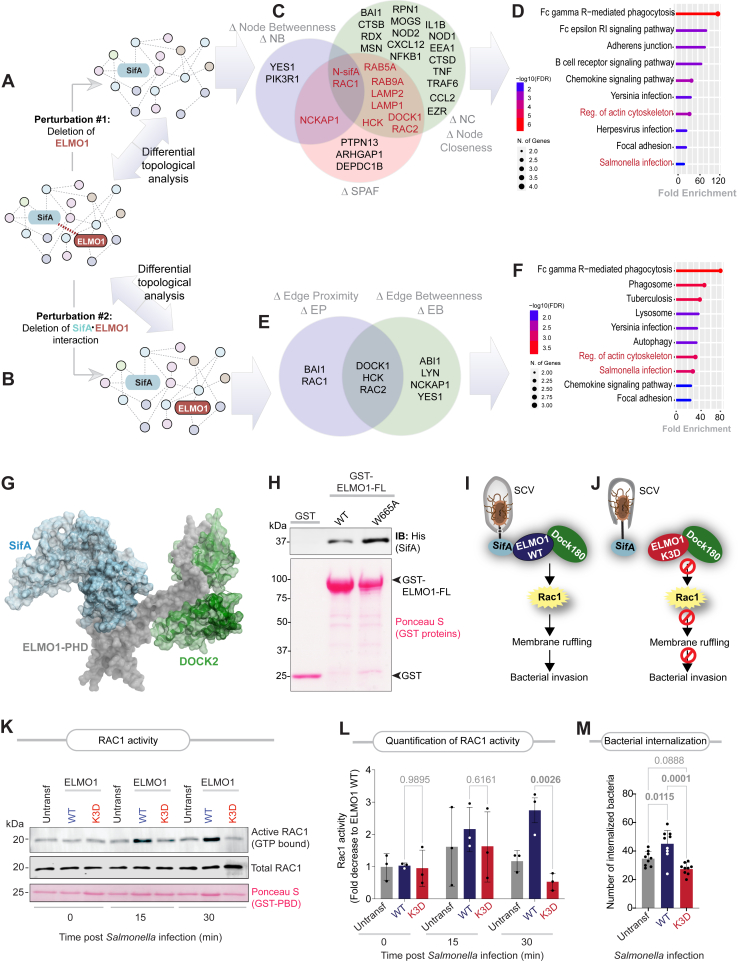

Disrupting the SifA–ELMO1 interface suppresses Rac1 activity and bacterial invasion

To assess the impact of selective disruption of the SifA–ELMO1 interface in the setting of an infection, we used an unbiased network-based approach. We leveraged a previously published (41) SifA interactome, as determined by proximity-dependent biotin labeling (BioID) and used those interactors as “seeds” for fetching additional interactors to build an integrated SifA(Salmonella)–host PPI network (see the Experimental procedures section for details). The resultant network (Fig. S6A) was perturbed by in silico deletion of either ELMO1 (Figs. 3A and S6B) or, more specifically, the SifA–ELMO1 interaction (Fig. 3B). Both modes of perturbation were analyzed by a differential network analysis (with versus without perturbations) using various network metrices (see legends; Fig. 3, C and E). As one would expect, deletion of ELMO1 impacts many proteins (Figs. 3C and S6, C and D), including those engaged in microbe sensing (BAI1, NOD1, and NOD2), membrane trafficking along the phagolysosomal pathway (EEA1, Rab5A, Rab9A, and LAMP), multiple Src-family kinases (LYN, YES, and HCK), inflammatory cytokines (IL1B, CCL2/MCP1, CXCL12, and TNF), as well as immune cell (B cell) and epithelial (adherens junction) pathways (Fig. 3D). Findings are consistent with prior published work, implicating ELMO1 in facilitating the recruitment of LAMP1 to SCVs (42), mounting a cytokine response (21, 35), as well as regulating epithelial junctions (43) upon Salmonella infection. The proteins found to be impacted based on at least two network metrices (Fig. 3C) are enriched for Rac1 signaling (Rac1, Rac2, Nckap1, and Dok180) and the endolysosomal pathway (LAMP and RABs). The more refined approach of selective deletion of the SifA–ELMO1 interaction yielded, as expected, a smaller list of proteins that mostly concerned with the DOCK1–RAC signaling axis and Src-family kinases, HCK, LYN, and YES (Fig. 3, E and F). Because phosphorylation of ELMO1 by Src-family kinases such as Src, Fyn (44), and HCK (45) also converge on Rac1, activation of Rac1 signaling, presumably via the ELMO1–DOCK1 axis, emerged as the most important function predicted to be impacted in infected cells.

Figure 3.

Prediction and validation of the consequences of disruption of the ELMO1–SifA interface.A and B, an SifA (Salmonella)–human PPI network was constructed using a previously identified BioID-determined interactome of SifA (41), and their connectors were fetched from the human STRING database (59). Network perturbation was carried out in silico either by deletion of ELMO1 (A; node deletion) or selective disruption of the ELMO1–SifA interaction (B; edge deletion). C and D, Venn diagram (C) shows sets of proteins that were impacted by in silico deletion of ELMO1, as determined by three independent metrics of network topological analyses: differential node betweenness (ΔNB), node closeness (ΔNB), and shortest path alteration fraction (ΔSPAF). Lollipop plots (D) indicate the KEGG pathways enriched among the proteins that were identified as impacted based on more than one node-based metric. See Fig. S6 for a detailed analysis. E and F, Venn diagram (E) shows sets of proteins that were impacted by in silico deletion of the ELMO1–SifA interaction, as determined by two metrics of network topological analyses: differential edge betweenness (ΔEB) and edge proximity (ΔEP). Lollipop plots (F) indicate the KEGG pathways enriched among the proteins that were identified using edge-based metrices. See Supporting Information Data 2 for a detailed list of nodes and edges. G, a homology model of a cocomplex between SifA (light blue), ELMO1 (gray), and DOCK180 (green), built by overlaying resolved crystal structures of DOCK2–ELMO1 (PDB code: 3A98) (24), ELMO1 (PDB code: 2VSZ), and SifA–SKIP (PDB code: 3CXB). H, recombinant His-SifA (∼5 μg) were used in a GST pulldown assay with GST (negative control), GST-tagged WT and W665A mutants of full-length (FL) ELMO1, and bound SifA was visualized by immunoblot using anti-His (SifA) antibody. Equal loading of GST proteins is confirmed by Ponceau S staining. I and J, key steps in SifA–ELMO1–Dock180 cocomplex–mediated Rac1 signaling (I) and the predicted impact of selectively disrupting SifA–ELMO1 interaction using the K3D mutant (J) are shown. K and L, ELMO1-depleted J774 macrophages (untransfected) transfected with either WT or K3D mutant ELMO1 and subsequently infected with Salmonella (MOI 10; at indicated time point postinfection) were assessed for Rac1 activation by pulldown assays using GST-PBD. Immunoblots and Ponceau S-stained GST proteins are shown in (K). Quantification of immunoblots in (L). Results are displayed as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA. M, bar graph represents the number of internalized bacteria by the same cells in (K) infected with Salmonella (MOI 10; 30 min postinfection). Results are displayed as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA. ELMO1, Engulfment and Cell Motility protein 1; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; MOI, multiplicity of infection; PDB, Protein Data Bank; PPI, protein–protein interaction.

Structure homology models of ternary complexes of SifA–ELMO1–DOCK revealed that although both SifA and DOCK180 bind ELMO1 (PHD), they do so via two distinct and nonoverlapping interfaces (Fig. 3G). To experimentally validate this finding, we generated a mutant ELMO1 (W665A) that was previously confirmed by two independent groups to be essential for binding DOCK180 (46, 47) and tested its ability to bind His-SifA in pulldown assays. Both WT and ELMO1-W665A bound SifA to similar extents, indicating that W665 is dispensable for binding SifA (Fig. 3H). Findings are also consistent with the fact that both SifA and DOCK180 coimmunoprecipitate with ELMO1 (21) and hence may exist as a ternary complex.

We anticipated that selective disruption of the SifA–ELMO1 interface (using the ELMO1-K3D mutant), while leaving intact the ELMO1–DOCK interface, would interrupt the ELMO1–DOCK–Rac1 signaling axis and reduce bacterial invasion (Fig. 3, I and J). This was indeed found to be the case as Rac1 signaling was induced during Salmonella infection in ELMO1-depleted J774 macrophages reconstituted with WT ELMO1 but found to be significantly blunted when the same macrophages were reconstituted with the K3D mutant ELMO1 (Fig. 3, K and L). Reduced Rac1 activity was also associated with reduced bacterial internalization (Fig. 3M). Findings demonstrate that one of the major consequences of mutating the polar triad of lysine residues on ELMO1 is reduction in both Rac1 activity and microbial invasion.

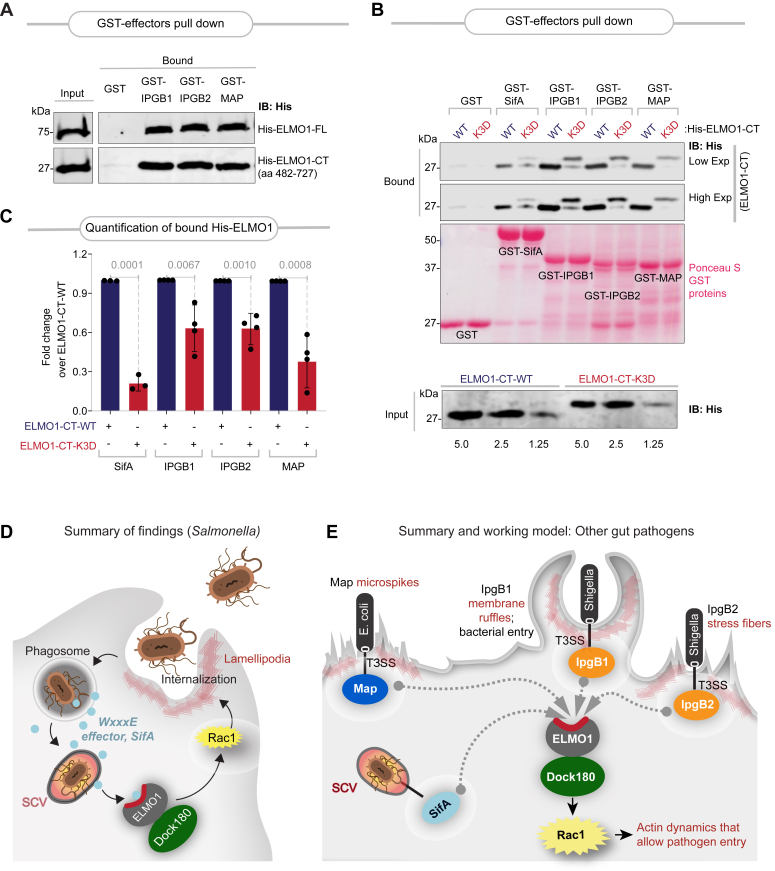

Diverse WxxxE effectors target the same lysine hot spot on ELMO1

Prior work using ELMO1-knockout zebrafish (E. coli/MAP (22)) and mouse (Shigella/IpgB1 (6) and Salmonella/SifA) (21) has independently concluded that diverse pathogens, acting via their WxxxE effectors trigger host immune responses through functional interactions with ELMO1. We asked if our insights into the nature of the SifA–ELMO1 interface are relevant also to other WxxxE motif–containing effectors. As observed previously for SifA (Fig. 1, J and K), WxxxE effectors IpgB1, IpgB2, and Map also directly bound both full-length (Fig. 4A, top) and the C-terminal PHD containing fragment (Fig. 4A, bottom) of ELMO1. More importantly, mutation of the polar lysine triad on ELMO1 reduced the binding of all effectors tested (Fig. 4, B and C), indicating that these effectors require the same hot spot as SifA to engage with ELMO1, presumably via similar hydrophobic contacts. Because the effectors have little to no sequence similarity other than the invariant WxxxE motif (see alignment; Fig. S7), and the N-terminal extension is unique to SifA, we were unable to predict the exact nature of the potential electrostatic contacts on the effectors. We conclude that the newly identified hot spot on ELMO1 represents a point of convergence for numerous WxxxE effectors encoded by diverse pathogens to engage with one host protein. It is noteworthy that each of these WxxxE effectors we tested here have recently been shown to require ELMO1 for inducing Rac1 signaling (21).

Figure 4.

The SifA–ELMO1 interface is a conserved site for engaging diverse WxxxE effectors.A, recombinant His-tagged CT (amino acids 482–727) or full-length (FL) ELMO1 proteins (∼3 μg) were used in a pulldown assay with immobilized FL GST-tagged WxxxE effectors (SifA, IpgB1, IpgB2, and Map) or GST alone (negative control). Bound ELMO1 proteins were visualized by immunoblot using anti-His (ELMO1) antibody. GST proteins are visualized by Ponceau S staining. B, recombinant WT or K3D mutant His-ELMO1-CT proteins (∼3 μg; Input, bottom) were used in pulldown assays with immobilized GST-tagged FL effectors as in A. Bound ELMO1 (top) was visualized by immunoblotting using an anti-His antibody. GST proteins are visualized by Ponceau S staining. C, quantification of immunoblots in (B). Results are displayed as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates). Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t test. D and E, schematic (D) summarizes the key findings in this work using Salmonella and its WxxxE-motif effector, SifA. Schematic (E) summarizes the key biochemical findings and the working model proposed for how diverse microbes use their WxxxE motif–containing virulence factors (effectors) to hijack the host engulfment pathway via a shared mechanism. Although diverse in sequence (see Fig. S7 for an alignment of WxxxE effectors) and function, they all bind a conserved surface on ELMO1 (highlighted in red). The major consequence of such WxxxE-effector–ELMO1 interaction is enhanced Rac1 activation and bacterial engulfment. ELMO1, Engulfment and Cell Motility protein 1; GST, glutathione-S-transferase.

Conclusions and study limitations

This work provides an atomic-level insight into a single point of vulnerability within the host engulfment pathway, that is, a hot spot (lysine triad) on the ELMO1 (PHD). This hot spot is exploited by diverse gut pathogens such as Salmonella to activate the ELMO1–DOCK180–Rac1 axis, invade host cells, and seek refuge within SCVs (see summary of findings; Fig. 4D). These findings come as a surprise because the bacterial effector proteins that are responsible for such exploitation are diverse, and yet, they all bind the same hot spot on ELMO1 to hijack the Rac1 axis to their advantage (see legend; Fig. 4E).

Because the WxxxE motif is found in enteric as well as plant pathogens, and within the Toll/interleukin-1 receptor modules of both host and pathogen proteins [but notably absent in commensals (21)], it is possible that some host WxxxE proteins may also engage ELMO1 via the same hot spot. If so, the pathogen-encoded WxxxE effectors should competitively block such interactions, exemplifying the phenomenon of molecular mimicry. The structural insights revealed here also warrant the consideration of another form of competitive binding, one in which the same WxxxE effector (SifA) may bind different host proteins (SKIP or ELMO1) using nearly identical interfaces. Because both interactions require the identical residues on SifA, the SifA–ELMO1 and SifA–SKIP interactions must be mutually exclusive. Given the roles of ELMO1 in the regulation of actin dynamics during bacterial entry and the role of SKIP in endosomal tubulation (32) and anterograde movement of endolysosomal compartments (39), we hypothesize that SifA may bind two host proteins sequentially. It may bind ELMO1 first during Salmonella entry and SCV formation and SKIP later to support cellular processes that help in SCV membrane stabilization, the development of Sifs, and the creation of a favorable environment for the survival and multiplication of Salmonella (39, 48). If/how SifA coordinates its interactions with two host proteins, ELMO1 and SKIP, during Salmonella infection remains unknown; however, the fact that the polar lysine triad on both host proteins is evolutionarily intact from fish to humans suggests that these conserved hot spots on host protein surfaces may have coevolved with the pathogens as part of a molecular arms race of adaptations. The deleterious impact of structure-rationalized mutants suggests that both the SifA–ELMO1 (shown here) and the SifA–SKIP (published before (26, 32)) interfaces are sensitive to disruption. This is particularly important because hydrophobic interactions that stabilize protein–protein interfaces via a central cluster of hot spot residues are of high therapeutic value because they are amenable to disruption with rationally designed small-molecule inhibitors (49).

This study also has a few limitations. For example, how post-translational modifications may impact the WxxxE–ELMO1 interface was not evaluated. It is possible that lysine methylation, which ironically was described as a post-translational modification first in Salmonella flagellin (50), may impact the interface, as shown in other instances (51). Similarly, phosphorylation at T618 or ubiquitination at K620 may have impacts that were not explored; because the ELMO1–DOCK180 cocomplex is known to be regulated by ubiquitination (52), and both proteins are downregulated rapidly upon lipopolysaccharide stimulation (53), we speculate that ubiquitination at K621 may deter WxxxE–effector interactions and thereby serve as a protective strategy of the host during acute infections. Finally, the impact of disrupting the WxxxE–ELMO1 interface on host immune responses was not studied here and will require the creation of knock-in K3D mutant models. All these avenues are expected to provide a more complete picture of the consequences of disrupting the WxxxE–ELMO1 interface and help formulate strategies to disrupt it for therapeutic purposes.

In conclusion, our studies characterize a polar patch on ELMO1 (PHD) as a conserved hot spot of host vulnerability—a so-called Achilles heel—which is exploited by multiple pathogens. Because prior studies on ELMO1-knockout zebrafish (22) and mice (6, 21) have implicated WxxxE–ELMO1 interactions as responsible also for mounting host inflammatory responses, the same polar patch on ELMO1 (PHD) may also serve as a conserved hot spot of intrusion detection.

Experimental procedures

Full experimental procedures can be found in the Supporting information.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text or the Supporting information. Original Western blot images and microscopy data will be shared by the lead contact upon request. This article also analyzes an existing publicly available proteomics dataset and protein structures (listed in the Key Resources Table). Source data for Gene Ontology analyses are provided with this article. This article includes PPI network analysis; a link to the codes is provided (Key Resources Table). Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this article is available from the lead contact upon request.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information (15, 21, 35, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Soumita Das (University of California San Diego, CA; currently at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, MA) for numerous reagents and constructs that were used in this work and for helpful discussions and Stella-Rita Ibeawuchi, Hobie Gementera and Alicia Amamoto for technical assistance. We also thank the University of California, San Diego—Cellular and Molecular Medicine Electron Microscopy Core (Research Resource Identifier: SCR_022039) for equipment access and technical assistance. The University of California, San Diego—Cellular and Molecular Medicine Electron Microscopy Core is partly supported by the National Institutes of Health Award number S10OD023527.

Author contributions

M. S. A., A. B., and P. G. conceptualization; M. S. A., S. R., S. S., A. B., and P. G. methodology; S. R. and S. S. software; M. S. A. validation; M. S. A., S. R., S. S., G. D. K., and P. G. formal analysis; M. S. A., S. R., S. S., and A. B. investigation; M. S. A., S. R., G. D. K., and P. G. data curation; M. S. A. writing–original draft; M. S. A., G. D. K., and P. G. writing–review & editing; S. S., G. D. K., and P. G. visualization; P. G. supervision; P. G. project administration; P. G. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants: R01-AI141630, UG3TR003355, UH3TR003355, and R01-AI55696 (to P. G.). P. G. was also supported by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and NIH programs. G. D. K. and S. S were supported through The American Association of Immunologists Intersect Fellowship Program for Computational Scientists and Immunologists. M. S. A. was supported in part by R01-DK107585. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Helmsley Charitable Trust or the NIH.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Clare E. Bryant

Contributor Information

Gajanan D. Katkar, Email: kgajanandattatray@ucsd.edu.

Pradipta Ghosh, Email: prghosh@ucsd.edu.

Supporting information

References

- 1.Steele-Mortimer O. The Salmonella-containing vacuole: moving with the times. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2008;11:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castanheira S., García-Del Portillo F. Salmonella populations inside host cells. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017;7:432. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai Y., Rosenshine I., Leong J.M., Frankel G. Intimate host attachment: enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Cell. Microbiol. 2013;15:1796–1808. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith K., Humphreys D., Hume P.J., Koronakis V. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli recruits the cellular inositol phosphatase SHIP2 to regulate actin-pedestal formation. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson J.L., Sanchez-Garrido J., Goddard P.J., Torraca V., Mostowy S., Shenoy A.R., et al. Shigella sonnei O-antigen inhibits internalization, vacuole escape, and inflammasome activation. mBio. 2019;10 doi: 10.1128/mBio.02654-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handa Y., Suzuki M., Ohya K., Iwai H., Ishijima N., Koleske A.J., et al. Shigella IpgB1 promotes bacterial entry through the ELMO-Dock180 machinery. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:121–128. doi: 10.1038/ncb1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finlay B.B., Cossart P. Exploitation of mammalian host cell functions by bacterial pathogens. Science. 1997;276:718–725. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galán J.E., Collmer A. Type III secretion machines: bacterial devices for protein delivery into host cells. Science. 1999;284:1322–1328. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cossart P., Sansonetti P.J. Bacterial invasion: the paradigms of enteroinvasive pathogens. Science. 2004;304:242–248. doi: 10.1126/science.1090124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connor M.G., Pulsifer A.R., Chung D., Rouchka E.C., Ceresa B.K., Lawrenz M.B. Yersinia pestis targets the host endosome recycling pathway during the biogenesis of the Yersinia-containing vacuole to avoid Killing by macrophages. mBio. 2018;9 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01800-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson R.O., Galán J.E. Campylobacter jejuni survives within epithelial cells by avoiding delivery to lysosomes. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e14. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coburn B., Sekirov I., Finlay B.B. Type III secretion systems and disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007;20:535–549. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00013-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orchard R.C., Kittisopikul M., Altschuler S.J., Wu L.F., Süel G.M., Alto N.M. Identification of F-actin as the dynamic hub in a microbial-induced GTPase polarity circuit. Cell. 2012;148:803–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alto N.M., Shao F., Lazar C.S., Brost R.L., Chua G., Mattoo S., et al. Identification of a bacterial type III effector family with G protein mimicry functions. Cell. 2006;124:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bulgin R., Raymond B., Garnett J.A., Frankel G., Crepin V.F., Berger C.N., et al. Bacterial guanine nucleotide exchange factors SopE-like and WxxxE effectors. Infect. Immun. 2010;78:1417–1425. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01250-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardt W.D., Chen L.M., Schuebel K.E., Bustelo X.R., Galán J.E. S. typhimurium encodes an activator of Rho GTPases that induces membrane ruffling and nuclear responses in host cells. Cell. 1998;93:815–826. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohya K., Handa Y., Ogawa M., Suzuki M., Sasakawa C. IpgB1 is a novel Shigella effector protein involved in bacterial invasion of host cells. Its activity to promote membrane ruffling via Rac1 and Cdc42 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:24022–24034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bulgin R.R., Arbeloa A., Chung J.C., Frankel G. EspT triggers formation of lamellipodia and membrane ruffles through activation of Rac-1 and Cdc42. Cell. Microbiol. 2009;11:217–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arbeloa A., Bulgin R.R., MacKenzie G., Shaw R.K., Pallen M.J., Crepin V.F., et al. Subversion of actin dynamics by EspM effectors of attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Cell. Microbiol. 2008;10:1429–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenny B., Ellis S., Leard A.D., Warawa J., Mellor H., Jepson M.A. Co-ordinate regulation of distinct host cell signalling pathways by multifunctional enteropathogenic Escherichia coli effector molecules. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;44:1095–1107. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sayed I.M., Ibeawuchi S.R., Lie D., Anandachar M.S., Pranadinata R., Raffatellu M., et al. The interaction of enteric bacterial effectors with the host engulfment pathway control innate immune responses. Gut Microbes. 2021;13 doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1991776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xue R., Wang Y., Wang T., Lyu M., Mo G., Fan X., et al. Functional verification of novel ELMO1 variants by live imaging in zebrafish. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.723804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grimsley C.M., Kinchen J.M., Tosello-Trampont A.C., Brugnera E., Haney L.B., Lu M., et al. Dock180 and ELMO1 proteins cooperate to promote evolutionarily conserved Rac-dependent cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:6087–6097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanawa-Suetsugu K., Kukimoto-Niino M., Mishima-Tsumagari C., Akasaka R., Ohsawa N., Sekine S., et al. Structural basis for mutual relief of the Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factor DOCK2 and its partner ELMO1 from their autoinhibited forms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:3305–3310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113512109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kukimoto-Niino M., Ihara K., Murayama K., Shirouzu M. Structural insights into the small GTPase specificity of the DOCK guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2021;71:249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2021.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diacovich L., Dumont A., Lafitte D., Soprano E., Guilhon A.A., Bignon C., et al. Interaction between the SifA virulence factor and its host target SKIP is essential for Salmonella pathogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:33151–33160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.034975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin Q., Yang W., Baird D., Feng Q., Cerione R.A. Identification of a DOCK180-related guanine nucleotide exchange factor that is capable of mediating a positive feedback activation of Cdc42. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:35253–35262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toret C.P., Collins C., Nelson W.J. An Elmo-Dock complex locally controls Rho GTPases and actin remodeling during cadherin-mediated adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 2014;207:577–587. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201406135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Achi S.C., Karimilangi S., Lie D., Sayed I.M., Das S. The WxxxE proteins in microbial pathogenesis. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2023;49:197–213. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2022.2046546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Z., Sutton S.E., Wallenfang A.J., Orchard R.C., Wu X., Feng Y., et al. Structural insights into host GTPase isoform selection by a family of bacterial GEF mimics. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:853–860. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klink B.U., Barden S., Heidler T.V., Borchers C., Ladwein M., Stradal T.E., et al. Structure of Shigella IpgB2 in complex with human RhoA: implications for the mechanism of bacterial guanine nucleotide exchange factor mimicry. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:17197–17208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.107953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohlson M.B., Huang Z., Alto N.M., Blanc M.P., Dixon J.E., Chai J., et al. Structure and function of Salmonella SifA indicate that its interactions with SKIP, SseJ, and RhoA family GTPases induce endosomal tubulation. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:434–446. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arbeloa A., Garnett J., Lillington J., Bulgin R.R., Berger C.N., Lea S.M., et al. EspM2 is a RhoA guanine nucleotide exchange factor. Cell. Microbiol. 2010;12:654–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01423.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raymond B., Crepin V.F., Collins J.W., Frankel G. The WxxxE effector EspT triggers expression of immune mediators in an Erk/JNK and NF-κB-dependent manner. Cell. Microbiol. 2011;13:1881–1893. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01666.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Das S., Sarkar A., Choudhury S.S., Owen K.A., Castillo V., Fox S., et al. ELMO1 has an essential role in the internalization of Salmonella Typhimurium into enteric macrophages that impacts disease outcome. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015;1:311–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruiz-Albert J., Yu X.J., Beuzón C.R., Blakey A.N., Galyov E.E., Holden D.W. Complementary activities of SseJ and SifA regulate dynamics of the Salmonella typhimurium vacuolar membrane. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;44:645–661. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beuzón C.R., Méresse S., Unsworth K.E., Ruíz-Albert J., Garvis S., Waterman S.R., et al. Salmonella maintains the integrity of its intracellular vacuole through the action of SifA. EMBO J. 2000;19:3235–3249. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arpaia N., Godec J., Lau L., Sivick K.E., McLaughlin L.M., Jones M.B., et al. TLR signaling is required for Salmonella typhimurium virulence. Cell. 2011;144:675–688. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dumont A., Boucrot E., Drevensek S., Daire V., Gorvel J.P., Poüs C., et al. SKIP, the host target of the Salmonella virulence factor SifA, promotes kinesin-1-dependent vacuolar membrane exchanges. Traffic. 2010;11:899–911. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jurrus E., Engel D., Star K., Monson K., Brandi J., Felberg L.E., et al. Improvements to the APBS biomolecular solvation software suite. Protein Sci. 2018;27:112–128. doi: 10.1002/pro.3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.D'Costa V.M., Coyaud E., Boddy K.C., Laurent E.M.N., St-Germain J., Li T., et al. BioID screen of Salmonella type 3 secreted effectors reveals host factors involved in vacuole positioning and stability during infection. Nat. Microbiol. 2019;4:2511–2522. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0580-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarkar A., Tindle C., Pranadinata R.F., Reed S., Eckmann L., Stappenbeck T.S., et al. ELMO1 regulates autophagy Induction and bacterial clearance during enteric infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2017;216:1655–1666. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sayed I.M., Suarez K., Lim E., Singh S., Pereira M., Ibeawuchi S.R., et al. Host engulfment pathway controls inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. FEBS J. 2020;287:3967–3988. doi: 10.1111/febs.15236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Makino Y., Tsuda M., Ohba Y., Nishihara H., Sawa H., Nagashima K., et al. Tyr724 phosphorylation of ELMO1 by Src is involved in cell spreading and migration via Rac1 activation. Cell Commun. Signal. 2015;13:35. doi: 10.1186/s12964-015-0113-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yokoyama N., deBakker C.D., Zappacosta F., Huddleston M.J., Annan R.S., Ravichandran K.S., et al. Identification of tyrosine residues on ELMO1 that are phosphorylated by the Src-family kinase Hck. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8841–8849. doi: 10.1021/bi0500832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kukimoto-Niino M., Katsura K., Kaushik R., Ehara H., Yokoyama T., Uchikubo-Kamo T., et al. Cryo-EM structure of the human ELMO1-DOCK5-Rac1 complex. Sci. Adv. 2021;7 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abg3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu M., Kinchen J.M., Rossman K.L., Grimsley C., deBakker C., Brugnera E., et al. PH domain of ELMO functions in trans to regulate Rac activation via Dock180. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:756–762. doi: 10.1038/nsmb800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackson L.K., Nawabi P., Hentea C., Roark E.A., Haldar K. The Salmonella virulence protein SifA is a G protein antagonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:14141–14146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801872105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Y., Huang Y., Swaminathan C.P., Smith-Gill S.J., Mariuzza R.A. Magnitude of the hydrophobic effect at central versus peripheral sites in protein-protein interfaces. Structure. 2005;13:297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ambler R.P., Rees M.W. Epsilon-N-Methyl-lysine in bacterial flagellar protein. Nature. 1959;184:56–57. doi: 10.1038/184056b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang J., Sengupta R., Espejo A.B., Lee M.G., Dorsey J.A., Richter M., et al. p53 is regulated by the lysine demethylase LSD1. Nature. 2007;449:105–108. doi: 10.1038/nature06092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Makino Y., Tsuda M., Ichihara S., Watanabe T., Sakai M., Sawa H., et al. Elmo1 inhibits ubiquitylation of Dock180. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:923–932. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Song J.H., Mascarenhas J.B., Sammani S., Kempf C.L., Cai H., Camp S.M., et al. TLR4 activation induces inflammatory vascular permeability via Dock1 targeting and NOX4 upregulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2022;1868 doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2022.166562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steele-Mortimer O., Brumell J.H., Knodler L.A., Méresse S., Lopez A., Finlay B.B. The invasion-associated type III secretion system of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is necessary for intracellular proliferation and vacuole biogenesis in epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 2002;4:43–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stein M.A., Leung K.Y., Zwick M., Garcia-del Portillo F., Finlay B.B. Identification of a Salmonella virulence gene required for formation of filamentous structures containing lysosomal membrane glycoproteins within epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;20:151–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.den Hartog G., Butcher L.D., Ablack A.L., Pace L.A., Ablack J.N.G., Xiong R., et al. Apurinic/apyrimidinic Endonuclease 1 restricts the internalization of bacteria into human intestinal epithelial cells through the inhibition of Rac1. Front. Immunol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.553994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Das S., Owen K.A., Ly K.T., Park D., Black S.G., Wilson J.M., et al. Brain angiogenesis inhibitor 1 (Bai1) is a pattern recognition receptor that mediates macrophage binding and engulfment of Gram-negative bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:2136–2141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014775108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., et al. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Szklarczyk D., Gable A.L., Nastou K.C., Lyon D., Kirsch R., Pyysalo S., et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D605–D612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sahoo D., Seita J., Bhattacharya D., Inlay M.A., Weissman I.L., Plevritis S.K., et al. MiDReG: a method of mining developmentally regulated genes using Boolean implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:5732–5737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913635107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qiao L., Sinha S., Abd El-Hafeez A.A., Lo I.C., Midde K.K., Ngo T., et al. A circuit for secretion-coupled cellular autonomy in multicellular eukaryotic cells. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2023;19 doi: 10.15252/msb.202211127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sinha S., Samaddar S., Das Gupta S.K., Roy S. Network approach to mutagenesis sheds insight on phage resistance in mycobacteria. Bioinformatics. 2021;37:213–220. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Banerjee S.J., Sinha S., Roy S. Slow poisoning and destruction of networks: edge proximity and its implications for biological and infrastructure networks. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2015;91 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.91.022807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Komander D., Patel M., Laurin M., Fradet N., Pelletier A., Barford D., et al. An alpha-helical extension of the ELMO1 pleckstrin homology domain mediates direct interaction to DOCK180 and is critical in Rac signaling. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:4837–4851. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-04-0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the Supporting information. Original Western blot images and microscopy data will be shared by the lead contact upon request. This article also analyzes an existing publicly available proteomics dataset and protein structures (listed in the Key Resources Table). Source data for Gene Ontology analyses are provided with this article. This article includes PPI network analysis; a link to the codes is provided (Key Resources Table). Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this article is available from the lead contact upon request.