Abstract

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) has long been acknowledged as a potential complication of total hip arthroplasty (THA) contributing to heightened patient morbidity, mortality, and substantial healthcare costs. We aimed to: 1) assess trends in VTE prophylaxis utilization between 2016 and 2021; 2) determine the incidence of postoperative VTE and transfusions; and 3) identify independent risk factors for 90-day VTE and transfusion risks following THA in relation to the use of aspirin, dabigatran, enoxaparin, rivaroxaban, and warfarin.

Methods

A national, all-payer database was queried from January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2022. Use trends for aspirin, enoxaparin, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and warfarin as thromboprophylaxis following THA was assessed. Incidence of ninety-day postoperative outcomes assessed included rates of 90-day postoperative VTE and transfusion.

Results

From 2016 to 2021, aspirin (n = 36,346) was the most used agent for VTE prophylaxis after THA, followed by dabigatran (n = 13,065), rivaroxaban (n = 11,790), enoxaparin (n = 11,380), and warfarin (n = 6326). Independent risk factors for 90-day VTE included CKD, COPD, CHF, obesity, dabigatran, enoxaparin, rivaroxaban, and warfarin (all p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Aspirin was used with increasing frequency and demonstrated lower rates of VTE and transfusion following THA, compared to dabigatran, enoxaparin, rivaroxaban, and warfarin. These findings seem to indicate that the increasing use of aspirin in VTE prophylaxis has been accomplished in appropriately selected patients.

Keywords: Aspirin, VTE prophylaxis, Hip arthroplasty, Trends, Anticoagulation

1. Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), has long been acknowledged as a potential complication of total hip arthroplasty (THA) contributing to heightened patient morbidity, mortality, and substantial healthcare costs.1 Historically, PE stood as the leading cause of mortality following total hip arthroplasty (THA).2,3 However, the introduction of routine VTE prophylaxis (VTEp) combined with advances in perioperative protocols,4 has reduced VTE incidence, with current estimates ranging from 0.24 % to 1.60 %.5, 6, 7, 8, 9

Potent anticoagulants such as warfarin, heparins, low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), were traditionally the mainstay of VTE chemoprophylaxis following THA. However, concerns regarding higher rates of bleeding10, and wound complications11,12 led to calls for a more optimal agent—one that strikes a balance between VTE prevention and the risk of bleeding.

Aspirin has garnered significant attention as VTEp due to its affordability, wide availability, well-established safety profile, no required monitoring, and the growing body of evidence supporting its efficacy as a VTE prophylactic.13 In 2022, a remarkable 93 % of members of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons (AAHKS) reported the use of aspirin in combination with mechanical measures for VTE prophylaxis,14 marking a substantial increase from the 20 % reported in 2012. There is evidence demonstrating a similar or slightly improved efficacy and safety profile of aspirin compared to commonly used anticoagulants,15,16 with significantly lower odds of major bleeding events,17 decrease rates of heterotopic ossification,18 knee manipulation for stiffness, prosthetic joint infections,10 mortality,15 and reduced overall costs.19 Patients considered high risk for VTE often receive more potent anticoagulants, such as low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), factor Xa inhibitors, and warfarin, however, some suggest aspirin to be more, or comparatively, effective, and safe even in patients considered high-risk.10,16,20

Despite the current prevalent use of aspirin for VTE prophylaxis, conflicting literature combined with the current rare occurrence of VTE after THA, creates a challenge for definitively determining the optimal agent for VTEP. While awaiting the results of large, high quality, randomized controlled trials, such as the PEPPER Trial,21 the large cohorts afforded by retrospective observational database analyses are a practical approach gain useful insights in the trends in VTEp utilization and current rates of VTE, as well as monitor the efficacy and safety of current measures. As such, this study aimed to: 1) assess trends in VTE prophylaxis utilization between 2016 and 2021; 2) determine the incidence of postoperative VTE and transfusions; and 3) identify independent risk factors for 90-day VTE and transfusion risks following THA in relation to the use of aspirin, dabigatran, enoxaparin, rivaroxaban, and warfarin.

2. Methods

2.1. Database

PearlDiver Mariner Patient Claims Database (PearlDiver Technologies, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) is a national, all-payer database containing over 120 million Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) compliant records from across the United States and includes commercial, Medicare, Medicaid, government, and cash payers. The database is queried using International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes were utilized to identify the patient cohorts. This study was exempt from Institutional Review Board approval due to the use of deidentified patient information. Annual audits for validity and reliability of the data were required for providers supplying the claims information by an independent third-party. There was no funding for this study.

2.2. Patients

All patients who underwent primary THA between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2022 were identified using ICD-10 and CPT codes. Patients undergoing THA who also had a pre-existing coagulopathy, cancer, or were prescribed an anticoagulant or antithrombotic within the year prior to undergoing THA were excluded. Revision THA and THA indicated due to trauma were also excluded.

Use trends for aspirin, enoxaparin, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and warfarin as thromboprophylaxis following THA was assessed for years 2016 through 2021. Patient demographic and baseline characteristics were collected, including age, sex, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI),22 alcohol abuse, chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), diabetes, hypertension, hypothyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, obesity, tobacco use, coronary artery disease (CAD), renal disease, renal failure, and depression. Patients receiving dabigatran were oldest, with an average age of 67.19 (SD = 10.31) and had the highest percentage of patients with an ECI >3 (64 %). Those receiving aspirin were the youngest, with average age of 61.58 (SD = 10.77) and had the lowest percent of patients with an ECI >3 (47 %). See Table 1 for full baseline demographic and patient characteristic data.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline patient characteristics.

| Dabigatran n = 13,065 (%) | Rivaroxaban n = 11,790 (%) | Enoxaparin n = 11,380 (%) | Warfarin n = 6326 (%) | Aspirin n = 36,346 (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Age (SD) | 67.19 (10.31) | 64.11 (10.38) | 62.51 (10.95) | 65.34 (10.32) | 61.58 (10.77) | |

| Sex | <0.0001 | |||||

| Female | 7661 (59) | 7170 (61) | 6827 (60) | 3869 (61) | 20,799 (57) | |

| Male | 5404 (41) | 4620 (39) | 4553 (40) | 2457 (39) | 15,547 (43) | |

| ECI >3 | 8421 (64) | 6057 (51) | 5895 (52) | 3249 (51) | 17,262 (47) | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 883 (7) | 843 (7) | 1017 (9) | 435 (7) | 3356 (9) | <0.0001 |

| CKD | 2694 (21) | 1733 (15) | 1766 (16) | 1049 (17) | 4236 (12) | <0.0001 |

| COPD | 4190 (32) | 3404 (29) | 3387 (30) | 1923 (30) | 9357 (26) | <0.0001 |

| CHF | 891 (7) | 573 (5) | 526 (5) | 340 (5) | 1165 (3) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 5042 (39) | 4174 (35) | 4113 (36) | 2348 (37) | 11,398 (31) | <0.0001 |

| HTN | 11,023 (84) | 9261 (79) | 8852 (78) | 5070 (80) | 26,049 (72) | <0.0001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 3838 (29) | 3235 (27) | 3073 (27) | 1720 (27) | 8999 (25) | <0.0001 |

| RA | 747 (6) | 633 (5) | 684 (6) | 344 (5) | 1756 (5) | <0.0001 |

| Obesity | 6515 (50) | 5803 (49) | 5467 (48) | 3048 (48) | 17,424 (48) | 0.00124 |

| Tobacco Use | 5575 (43) | 5036 (43) | 5018 (44) | 2566 (41) | 15,827 (44) | <0.0001 |

| CAD | 4363 (33) | 2876 (24) | 2747 (24) | 1631 (26) | 6959 (19) | <0.0001 |

| Renal Disease | 2776 (21) | 1797 (15) | 1826 (16) | 1092 (17) | 4365 (12) | <0.0001 |

| Depression | 4952 (38) | 4662 (40) | 4738 (42) | 2490 (39) | 14,205 (39) | <0.0001 |

| Renal Failure | 911 (7) | 625 (5) | 655 (6) | 433 (7) | 1368 (4) | <0.0001 |

SD: Standard Deviation; ECI: Elixhauser Comorbidity Index; CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CHF: Congestive Heart Failure; HTN: Hypertension; RA: Rheumatoid Arthritis; CAD: Coronary Artery Disease.

2.3. Outcomes

Incidence of ninety-day postoperative outcomes assessed included rates of 90-day postoperative VTE and transfusion. A multivariable regression was performed to determine independent risk factors for 90-day VTE and transfusion following THA, as compared to aspirin, controlling for gender, age, ECI >3, alcohol abuse, chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart Failure (CHF), diabetes, hypertension (HTN), hypothyroidism, obesity, tobacco use, and chronic steroid use.

2.4. Data analysis

Continuous variables such as age were compared using student's t-tests. Categorical variables, including demographics, comorbidities, and complications utilized Chi-square tests in bivariate analyses. Multivariable analyses were performed to determine independent risk factors for 90-day transfusion and VTE following THA. All analyses were performed using R Studio (Statistics Department of the University of Auckland, New Zealand) with significance regarded as p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

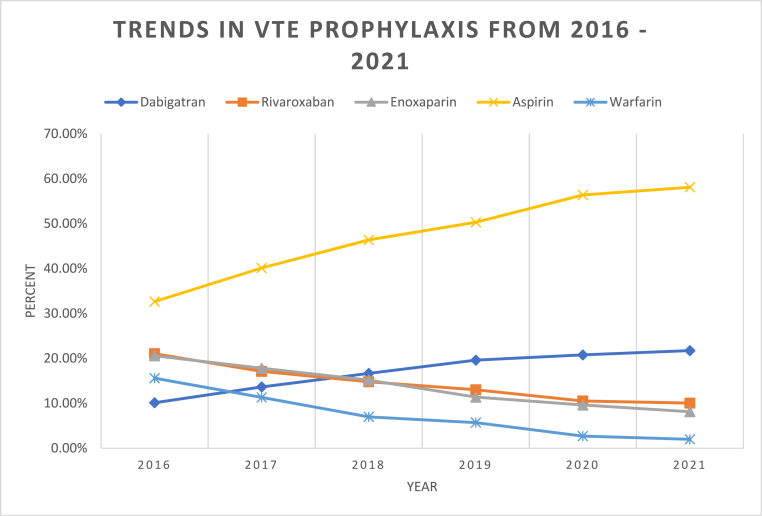

From 2016 to 2021, aspirin (n = 36,346) was the most used agent for VTE prophylaxis after THA, followed by dabigatran (n = 13,065), rivaroxaban (n = 11,790), enoxaparin (n = 11,380), and warfarin (n = 6326), respectively. Aspirin saw the greatest increase in use (33–58 %), while the use of warfarin had the greatest decrease (16–2 %) over this time. In 2016, dabigatran was the least used agent (10 %), however by 2021 it was the second most used agent (22 %) for VTEp. Rivaroxaban and enoxaparin both decreased in use, 21 %–10 % and 21 %–8 %, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Thromboprophylaxis use trends by year from 2016 to 2021.

| Yearly Total | Dabigatran |

Rivaroxaban |

Enoxaparin |

Aspirin |

Warfarin |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | ||

| 2016 | 15,434 | 1563 | 10.13 % | 3249 | 21.05 % | 3177 | 20.58 % | 5039 | 32.65 % | 2406 | 15.59 % |

| 2017 | 13,739 | 1875 | 13.65 % | 2351 | 17.11 % | 2446 | 17.80 % | 5512 | 40.12 % | 1555 | 11.32 % |

| 2018 | 13,992 | 2332 | 16.67 % | 2071 | 14.80 % | 2123 | 15.17 % | 6488 | 46.37 % | 978 | 6.99 % |

| 2019 | 15,273 | 2994 | 19.60 % | 1988 | 13.02 % | 1738 | 11.38 % | 7682 | 50.30 % | 871 | 5.70 % |

| 2020 | 15,514 | 3224 | 20.78 % | 1633 | 10.53 % | 1493 | 9.62 % | 8746 | 56.37 % | 418 | 2.69 % |

| 2021 | 4955 | 1077 | 21.74 % | 498 | 10.05 % | 403 | 8.13 % | 2879 | 58.10 % | 98 | 1.98 % |

Fig. 1.

Trends in VTE prophylaxis use from 2016 to 2021.

3.2. Outcomes

The cohort who received dabigatran had the highest incidence of 90-day postoperative VTE (3.9 %), followed second by rivaroxaban (2.5 %). The cohort who received aspirin had the lowest incidence of 90-day postoperative VTE (0.4 %), as well as the lowest incidence of requiring transfusion (1.1 %). Enoxaparin use had the highest incidence of transfusion (1.9 %) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Incidence of postoperative VTE and transfusion within 90 Days of THA.

| Dabigatran | Rivaroxaban | Enoxaparin | Aspirin | Warfarin | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 13,065 (%) | n = 11,790 (%) | n = 11,380 (%) | n = 36,346 (%) | n = 6326 (%) | ||

| 90-Day Complications | ||||||

| VTE | 512 (3.9) | 290 (2.5) | 132 (1.2) | 153 (0.4) | 138 (2.2) | <0.0001 |

| Transfusion | 182 (1.4) | 170 (1.4) | 215 (1.9) | 394 (1.1) | 103 (1.6) | <0.0001 |

TKA: Total Knee Arthroplasty; VTE: Venous Thromboembolism.

Compared to aspirin, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, enoxaparin, and warfarin all demonstrated greater odds of VTE when compared to aspirin (all p-value <0.0001). Dabigatran use was associated with nearly 10-fold greater odds of VTE in the 90 days following THA relative to aspirin (OR 9.65, 95 % CI 8.05 to 11.57, p < 0.0001). Enoxaparin was associated with the greatest odds of requiring transfusion (OR 1.76, 95 % CI 1.49 to 2.08, p < 0.0001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Odds of VTE and transfusion within 90 Days of THAa.

| Dabigatran |

Rivaroxaban |

Enoxaparin |

Warfarin |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95 % CI) | p-value | OR (95 % CI) | p-value | OR (95 % CI) | p-value | OR (95 % CI) | p-value | |

| 90-Day Complications | ||||||||

| VTE | 9.65 (8.05–11.57) | <0.0001 | 5.97 (4.90–7.26) | <0.0001 | 2.78 (2.20–3.51) | <0.0001 | 5.28 (4.18–6.65) | <0.0001 |

| Transfusion | 1.29 (1.08–1.54) | 0.0049 | 1.33 (1.11–1.60) | 0.0018 | 1.76 (1.49–2.08) | <0.0001 | 1.51 (1.21–1.88) | 0.0002 |

Odds ratio calculated with Aspirin as comparative group. TKA: Total Knee Arthroplasty; OR: Odds Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval; VTE: Venous Thromboembolism.

Independent risk factors for 90-day VTE included CKD, COPD, CHF, obesity, dabigatran, enoxaparin, rivaroxaban, and warfarin (all p < 0.05) (Table 5). Independent risk factors for 90-day transfusion included CKD, HTN, tobacco use, rivaroxaban, and warfarin (all p < 0.05). Male sex and obesity were independently associated with a decreased risk of requiring transfusion (Table 6).

Table 5.

Independent risk factors for 90-day VTEa.

| OR | 95 % CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.9894 |

| Male Sex | 1.09 | 0.95–1.25 | 0.2144 |

| ECI | 1.00 | 0.97–1.03 | 0.9508 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 1.08 | 0.83–1.38 | 0.5441 |

| CKD | 1.21 | 1.01–1.44 | 0.0376 |

| COPD | 1.47 | 1.28–1.70 | < 0.0001 |

| CHF | 0.71 | 0.52–0.97 | 0.0356 |

| Diabetes | 1.16 | 0.91–1.47 | 0.2145 |

| HTN | 0.99 | 0.82–1.21 | 0.9361 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0.95 | 0.81–1.10 | 0.4840 |

| Obesity | 1.37 | 1.19–1.58 | < 0.0001 |

| Tobacco Use | 0.90 | 0.78–1.03 | 0.1396 |

| Dabigatran | 24.59 | 18.72–32.95 | < 0.0001 |

| Enoxaparin | 18.42 | 12.18–27.64 | < 0.0001 |

| Rivaroxaban | 14.51 | 10.93–19.61 | < 0.0001 |

| Warfarin | 7.52 | 5.24–10.82 | < 0.0001 |

OR: Odds Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval; VTE: Venous Thromboembolism.

Controlled for gender, age, ECI >3, Alcohol Abuse, Chronic Kidney Disease, Chronic Pulmonary Disease, Congestive Heart Failure, Diabetes, Hypertension, Hypothyroidism, Obesity, Tobacco Use, Chronic Steroid Use.

Table 6.

Independent risk factors for 90-day transfusiona.

| OR | 95 % CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.04984 |

| Male Sex | 0.50 | 0.42–0.59 | < 0.0001 |

| ECI | 1.15 | 1.11–1.18 | < 0.0001 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 0.93 | 0.72–1.19 | 0.57617 |

| CKD | 1.33 | 1.10–1.60 | 0.00249 |

| COPD | 0.98 | 0.84–1.15 | 0.83382 |

| CHF | 1.08 | 0.81–1.41 | 0.59010 |

| Diabetes | 0.94 | 0.71–1.22 | 0.63664 |

| HTN | 1.30 | 1.05–1.62 | 0.01688 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0.87 | 0.74–1.02 | 0.09511 |

| Obesity | 0.85 | 0.73–0.99 | 0.03238 |

| Tobacco Use | 1.20 | 1.03–1.39 | 0.01635 |

| Dabigatran | 1.13 | 0.94–1.36 | 0.19413 |

| Enoxaparin | 1.20 | 0.72–1.88 | 0.45687 |

| Rivaroxaban | 1.32 | 1.09–1.58 | 0.00418 |

| Warfarin | 1.44 | 1.12–1.83 | 0.00312 |

OR: Odds Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval; ECI: Elixhauser Comorbidity Index; CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CHF: Congestive Heart Failure; HTN: Hypertension; RA: Rheumatoid Arthritis; CAD: Coronary Artery Disease.

Controlled for gender, age, ECI >3, Alcohol Abuse, Chronic Kidney Disease, Chronic Pulmonary Disease, Congestive Heart Failure, Diabetes, Hypertension, Hypothyroidism, Obesity, Tobacco Use, Chronic Steroid Use.

4. Discussion

Efforts to identify an optimal VTE chemoprophylactic agent that balances the reduction in clot formation with the risk of postoperative bleeding-related complications has been underway for nearly 2 decades. While a consensus on the best approach remains elusive, aspirin has garnered immense attention due to the mounting evidence supporting its efficacy and safety. Nonetheless, the search for an ideal agent continues, as high-quality evidence comparing its efficacy and safety with common anticoagulants remains inconclusive. Observational studies, like the present one, play a crucial role in monitoring prophylaxis trends and associated outcomes. Our study, spanning from 2016 to 2021, revealed a rising trend in aspirin use, correlating with the lowest rates of VTE and transfusions.

This observational study presents several limitations that warrant attention. First, given its observational nature, it carries an inherent risk of selection bias. The rationale behind a surgeons' selection of VTE prophylaxis agents for individual patients is not known from the available data, therefore it cannot be ruled out that those patients receiving aspirin for VTEp already had a lower baseline risk than those receiving more potent, anticoagulants, introducing the potential to skew results. To mitigate this risk, a multivariable analysis was performed to control for baseline patient characteristics. Furthermore, neither the specific dosage nor the frequency of administration for each prophylactic agent, nor the extent of patient adherence to the prescribed protocols, could be ascertained. Similarly, perioperative protocols, such as anesthesia type, TXA use, time to ambulation, for example, were unknown. Additionally, the study was constrained by its reliance on prescribed medications within the database, limiting inclusion to patients specifically prescribed aspirin. This precluded the use of a control group as it would present the risk of erroneously including individuals who may have utilized over-the-counter aspirin. Moreover, it is important to acknowledge the susceptibility to coding inaccuracies in databases. To address this issue, regular third-party performance audits are conducted with the aim of minimizing coding errors, with a reported 1 % coding error rate.23 Finally, it is crucial to note that the findings of this study may not be readily applicable to individuals with known hypercoagulability, cancer diagnoses, or those who had received anticoagulants or antithrombotic drugs in the year preceding THA, as these patient groups were intentionally excluded from the analysis.

Arthroplasty surgeons’ use of aspirin VTEp has seen a substantial increase in popularity over the last decade.14,24 Notably, a recent study by Agarwal et al. reported a 27.01 % positive annual growth rate in the use of prescribed aspirin following THA from 2011 to 2019. During this period, they also observed a significant reduction VTE rates, decreasing from 1.96 % in 2011 to 1.25 % in 2019.25 The authors largely attributed the decreasing VTE rates during this period to be due to improvements in perioperative protocols4,26,27 and pre-operative medical optimization.28 This shift in clinical practice towards increased aspirin utilization can likely additionally be explained by low cost,19 lack of routine monitoring requirements, and the convenience of oral administration, the latter two which contribute positively to patient compliance.29

The efficacy of aspirin in preventing venous thromboembolism (VTE) following total hip arthroplasty (THA) has been extensively studied. Sidhu et al. compared 90-day VTE rates in elective primary THA and TKA, evaluating aspirin, LMWH, LMWH with aspirin, and direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC). They found aspirin to be associated with low rates of symptomatic VTE, although no significant association between VTE and prophylaxis type was observed after adjusting for confounders.30 Additionally, another study investigated 90-day VTE rates following THA or TKA, comparing aspirin with non-aspirin anticoagulants, including factor Xa inhibitors (e.g., rivaroxaban), LMWH (enoxaparin), and warfarin. Their findings suggested that aspirin was non-inferior to LMWH and warfarin for VTE prevention but not when compared to factor Xa inhibitors.10 While practice generally favors the use of one of the more potent anticoagulants for those considered to be high-risk for VTE, several studies have revealed that aspirin may still be sufficient in high-risk patients. For example, Ludwick et al. reported an incidence of 0.4 % for symptomatic VTE with aspirin in patients undergoing primary TKA or THA, with no increased risk of VTE even after controlling for comorbidities (p = 0.024).31 This finding is particularly noteworthy as they focused on patients with a history of VTE, a group at high risk for VTE following THA. A similar result was observed by Tan et al. which indicated that aspirin was as effective as LMWH (enoxaparin) and warfarin, in primary and revision THA and TKA patients deemed high-risk for VTE16 as determined by an existing VTE risk stratification tool.32 These studies collectively contribute to the growing body of evidence supporting aspirin as an effective VTE chemoprophylactic agent.

An integral aspect of research endeavors aimed at determining the most suitable chemoprophylactic agent involves the identification of risk factors that may significantly elevate a patient's susceptibility to VTE or the need for transfusion. In our study, we identified chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and obesity as independent risk factors for VTE, findings largely consistent with existing literature.33, 34, 35, 36, 37 While both are commonly associated with a higher comorbidity burden, heightening the risk of surgical complications overall, the literature on VTE risk in COPD and obesity has regularly highlighted the presence of chronic low-level systemic inflammation38, 39, 40, 41 as contributing to an elevated baseline VTE risk by way of enhanced coagulation and impeded fibrinolysis.38,42, 43, 44 Assessing VTE risk in obesity, Yuan et al. demonstrated waist circumference, serving as a proxy for abdominal obesity, was a better predictor of VTE risk than overall obesity, as measured by body mass index (BMI),45 possibly due to the distinct impact of visceral adiposity on systemic inflammation41 and thus VTE risk.46 This may explain inconsistencies in the literature with regards to obesity's effect on VTE risk and VTEp effectiveness following THA,47 as BMI is overwhelming used for this purpose. The anti-inflammatory properties of aspirin may be a possible explanation for the non-inferior effectiveness of aspirin even in some higher risk populations, relative to anticoagulants.47,48

In our study, several risk factors for transfusion following THA were identified. The relationship between elevated transfusion risk and CKD has been extensively delineated in the literature.49 In fact, risk of transfusion has been found to be positively correlated with disease severity, as determined by eGFR-based staging,50,51 with increased transfusion risk even seen in those with mild to moderate CKD (stages 3 b and 4).51 Many have underscored the need to optimize hemoglobin (Hgb) preoperatively, not only in those with CKD, but all patients undergoing THA,52,53 due to preoperative anemia predicting postoperative transfusion necessity.54 The relationship between transfusion and obesity is one of debate however, the present study supports obesity being independently associated with a lower risk of transfusion.55, 56, 57 This may be a factor of the larger total blood volume with increasing body weights,57,58 or the increased propensity toward a hypercoagulable state in the obese population.59 The elevated risk of transfusion with warfarin and rivaroxaban corroborates that of many reports.60, 61, 62

In conclusion, from 2016 to 2021, aspirin was used with increasing frequency and demonstrated lower rates of VTE and transfusion following THA, compared to dabigatran, enoxaparin, rivaroxaban, and warfarin. These findings seem to indicate that the increasing use of aspirin VTEp has been accomplished in appropriately selected patients.

Funding

None.

Data availability

Available in a respository upon request.

Patient consent

No patient consent needed due to retrospective nature and public database.

Ethical approval

IRB exemption due to retrospective nature and public database.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mallory C. Moore: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Jeremy A. Dubin: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Sandeep S. Bains: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Daniel Hameed: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. James Nace: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Ronald E. Delanois: Conceptualization, Formal Analaysis, Project, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

No use of AI tool.

Declaration of competing interest

JD- None.

DH-None.

JN- Arthritis Foundation: Board or committee member, Journal of Arthroplasty, Journal of the American Osteopathic Medicine Association, Orthopedic, Knowledge Online: Editorial or governing board, Journal of Knee Surgery: Editorial or governing board, Knee: Editorial or governing board, Microport: Paid consultant; Paid presenter or speaker; Research support, Stryker: Research support United: Research support

RD- Baltimore City Medical Society.: Board or committee member, Biocomposites, Inc.: Research support, CyMedica Orthopedics: Research support, DePuy Synthes, Product, Inc.: Research support, Flexion Therapeutics: Research support, Microport Orthopedics, Inc.: Research support, Orthofix, Inc.: Research support, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI): Research support, Smith & Nephew: Research support, Stryker: Research support, Tissue Gene: Research support, United Orthopedic Corporation: Research support

MM - None.

SB - None.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- 1.Shahi A., Chen A.F., Tan T.L., Maltenfort M.G., Kucukdurmaz F., Parvizi J. The incidence and economic burden of in-hospital venous thromboembolism in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(4):1063–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coventry M.B., Beckenbaugh R.D., Nolan D.R., Ilstrup D.M. 2,012 total hip arthroplasties. A study of postoperative course and early complications. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56(2):273–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson R., Green J.R., Charnley J. Pulmonary embolism and its prophylaxis following the Charnley total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1977;127:123–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger R.A., Sanders S.A., Thill E.S., Sporer S.M., Della Valle C. Newer anesthesia and rehabilitation protocols enable outpatient hip replacement in selected patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(6):1424–1430. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0741-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedersen A.B., Mehnert F., Sorensen H.T., et al. The risk of venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, major bleeding and death in patients undergoing total hip and knee replacement A 15-year retrospective cohort study of routine clinical practice. Bone Joint Lett J. 2014;4:96–479. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dua A., Desai S.S., Lee C.J., Heller J.A. National trends in deep vein thrombosis following total knee and total hip replacement in the United States. Ann Vasc Surg. 2017;38:310–314. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.05.110. Elsevier Inc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahi A., Bradbury T.L., Guild G.N., Saleh U.H., Ghanem E., Oliashirazi A. What are the incidence and risk factors of in-hospital mortality after venous thromboembolism events in total hip and knee arthroplasty patients? Arthroplast Today. 2018;4(3):343–347. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bateman D.K., Dow R.W., Brzezinski A., Bar-Eli H.Y., Kayiaros S.T. Correlation of the caprini score and venous thromboembolism incidence following primary total joint arthroplasty—results of a single-institution protocol. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(12):3735–3741. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howard T.A., Judd C.S., Snowden G.T., Lambert R.J., Clement N.D. Incidence and risk factors associated with venous thromboembolism following primary total hip arthroplasty in low-risk patients when using aspirin for prophylaxis. HIP Int. 2022;32(5):562–567. doi: 10.1177/1120700021994530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh G., Prentice H.A., Winston B.A., Kroger E.W. Comparison of 90-day adverse events associated with aspirin and potent anticoagulation use for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: a cohort study of 72,288 total knee and 35,142 total hip arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38(8) doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2023.02.021. 1602-1612.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh V., Shahi A., Saleh U., Tarabichi S., Oliashirazi A. Persistent wound drainage among total joint arthroplasty patients receiving aspirin vs coumadin. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(12):3743–3746. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aquilina A.L., Brunton L.R., Whitehouse M.R., Sullivan N., Blom A.W. Direct thrombin inhibitor (dti) vs. Aspirin in primary total hip and knee replacement using wound ooze as the primary outcome measure. A prospective cohort study. HIP Int. 2012;22(1):22–27. doi: 10.5301/HIP.2012.9058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haykal T., Kheiri B., Zayed Y., et al. Aspirin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after hip or knee arthroplasty: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop. 2019;16(4):294–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdel M.P., Carender C.N., Berry D.J. Current practice trends in primary hip and knee arthroplasties among members of the American association of hip and knee surgeons. J Arthroplasty. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2023.08.005. Published online October 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rondon A.J., Shohat N., Tan T.L., Goswami K., Huang R.C., Parvizi J. The use of aspirin for prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism decreases mortality following primary total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. 2019;101(6):504–513. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.18.00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan T.L., Foltz C., Huang R., et al. Potent anticoagulation does not reduce venous thromboembolism in high-risk patients. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery - American. 2019;101(7):589–599. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.18.00335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shohat N., Ludwick L., Goh G S., Streicher S., Chisari E., Parvizi J. Aspirin thromboprophylaxis is associated with less major bleeding events following total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2022;37(2):379–384.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2021.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaz K.M., Brown M.L., Copp S.N., Bugbee W.D. Aspirin used for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in total hip arthroplasty decreases heterotopic ossification. Arthroplast Today. 2020;6(2):206–209. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2020.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gutowski C.J., Zmistowski B.M., Lonner J.H., Purtill J.J., Parvizi J. Direct costs of aspirin versus warfarin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total knee or hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9):36–38. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang A., Zak S., Iorio R., Slover J., Bosco J., Schwarzkopf R. Low-dose aspirin is safe and effective for venous thromboembolism prevention in patients undergoing revision total hip arthroplasty: a retrospective cohort study. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(8):2182–2187. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pellegrini J.V.D., Eikelboom J.W., Evarts C.M., et al. Randomised comparative effectiveness trial of Pulmonary Embolism Prevention after hiP and kneE Replacement (PEPPER): the PEPPER trial protocol. BMJ Open. 2022;12(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ondeck N.T., Bohl D.D., Bovonratwet P., McLynn R.P., Cui J.J., Grauer J.N. Discriminative ability of elixhauser's comorbidity measure is superior to other comorbidity scores for inpatient adverse outcomes after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(1):250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.2020 Medicare Fee-for Service Supplemental Improper Payment Data. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

- 24.Abdel M.P., Berry D.J. 2019. Current Practice Trends in Primary Hip and Knee Arthroplasties Among Members of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons: A Long-Term Update. J Arthroplasty. Published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agarwal A.R., Das A., Harris A., Campbell J.C., Golladay G.J., Thakkar S.C. Trends of venous thromboembolism after total hip arthroplasty in the United States: analysis from 2011 to 2019. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2023;31(7):E376–E384. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-22-00708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galat D.D., McGovern S.C., Larson D.R., Harrington J.R., Hanssen A.D., Clarke H.D. Surgical treatment of early wound complications following primary total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. 2009;91(1):48–54. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein G.R., Posner J.M., Levine H.B., Hartzband M.A. Same day total hip arthroplasty performed at an ambulatory surgical center: 90-day complication rate on 549 patients. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(4):1103–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernstein D.N., Liu T.C., Winegar A.L., et al. Evaluation of a preoperative optimization protocol for primary hip and knee arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(12):3642–3648. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dietz M.J., Moushmoush O., Frye B.M., Lindsey B.A., Murphy T.R., Klein A.E. Randomized trial of postoperative venous thromboembolism prophylactic compliance: aspirin and mobile compression pumps. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2022;30(20):E1319–E1326. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-01063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sidhu V., Badge H., Churches T., Maree Naylor J., Adie S., Harris I A. Comparative effectiveness of aspirin for symptomatic venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty, a cohort study. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2023;24(1) doi: 10.1186/s12891-023-06750-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludwick L., Shohat N., Van Nest D., Paladino J., Ledesma J., Parvizi J. Aspirin may Be a suitable prophylaxis for patients with a history of venous thromboembolism undergoing total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. 2022;104(16):1438–1446. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.21.00601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parvizi J., Huang R., Rezapoor M., Bagheri B., Maltenfort M.G. Individualized risk model for venous thromboembolism after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(9):180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.02.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vakharia R.M., Adams C.T., Anoushiravani A.A., Ehiorobo J.O., Mont M.A., Roche M.W. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with higher rates of venous thromboemboli following primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(8):2066–2071.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng T., Yang C., Ding C., Zhang X. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with serious infection and venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasties: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38(3):578–585. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2022.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parvizi J., Huang R., Rezapoor M., Bagheri B., Maltenfort M.G. Individualized risk model for venous thromboembolism after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(9):180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.02.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hotoleanu C. Association between obesity and venous thromboembolism. Med Pharm Rep. 2020;93(2):162–168. doi: 10.15386/mpr-1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zuke W.A., Chughtai M., Emara A.K., et al. What are drivers of readmission for readmission-requiring venous thromboembolic events after primary total hip arthroplasty? An analysis of 544,443 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2022;37(5):958–965.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2022.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gan W.Q., Man S.F.P., Senthilselvan A., Sin D.D. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Thorax. 2004;59(7):574–580. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.019588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mair K.M., Gaw R., MacLean M.R. Obesity, estrogens and adipose tissue dysfunction – implications for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2020;10(3) doi: 10.1177/2045894020952023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klasan A., Dworschak P., Heyse T.J., et al. COPD as a risk factor of the complications in lower limb arthroplasty: a patient-matched study. International Journal of COPD. 2018;13:2495–2499. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S161577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishida M., Moriyama T., Sugita Y., Yamauchi-Takihara K. Abdominal obesity exhibits distinct effect on inflammatory and anti-inflammatory proteins in apparently healthy Japanese men. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2007;6 doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang G., De Staercke C., Hooper W.C. The effects of obesity on venous thromboembolism: a review. Open J Prev Med. 2012;2(4):499–509. doi: 10.4236/ojpm.2012.24069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maclay J.D., McAllister D.A., Johnston S., et al. Increased platelet activation in patients with stable and acute exacerbation of COPD. Thorax. 2011;66(9):769–774. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.157529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saghazadeh A., Rezaei N. Inflammation as a cause of venous thromboembolism. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;99:272–285. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan S., Bruzelius M., Xiong Y., Håkansson N., Åkesson A., Larsson S.C. Overall and abdominal obesity in relation to venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemostasis. 2021;19(2):460–469. doi: 10.1111/jth.15168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pierre-Emmanuel M., Marie-Christine A. Thrombosis in central obesity and metabolic syndrome: mechanisms and epidemiology. Thromb Haemostasis. 2013;110(4):669–680. doi: 10.1160/TH13-01-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang A., Sicat C.S., Singh V., Rozell J.C., Schwarzkopf R., Long W.J. Aspirin use for venous thromboembolism prevention is safe and effective in overweight and obese patients undergoing revision total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2021;36(7):S337–S344. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Humphrey T.J., O'Brien T.D., Melnic C.M., et al. Morbidly obese patients undergoing primary total joint arthroplasty may experience higher rates of venous thromboembolism when prescribed direct oral anticoagulants vs aspirin. J Arthroplasty. 2022;37(6):1189–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2022.01.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Augustin I.D., Yeoh T.Y., Sprung J., Berry D.J., Schroeder D.R., Weingarten T.N. Association between chronic kidney disease and blood transfusions for knee and hip arthroplasty Surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(6):928–931. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan T.L., Kheir M.M., Tan D.D., Filippone E.J., Tischler E.H., Chen A.F. Chronic kidney disease linearly predicts outcomes after elective total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(9):175–179.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Antoniak D.T., Benes B.J., Hartman C.W., Vokoun C.W., Samson K.K., Shiffermiller J.F. Impact of chronic kidney disease in older adults undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty: a large database study. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(5):1214–1221.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanreich C., Cushner F., Krell E., et al. Blood management following total joint arthroplasty in an aging population: can we do better? J Arthroplasty. 2022;37(4):642–651. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2021.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patil A., Sephton B.M., Ashdown T., Bakhshayesh P. Blood loss and transfusion rates following total hip arthroplasty: a multivariate analysis. Acta Orthop Belg. 2022;88(1):27–34. doi: 10.52628/88.1.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang Z.Y., Huang C., Xie J.W., et al. Analysis of a large data set to identify predictors of blood transfusion in primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. Transfusion (Paris) 2018;58(8):1855–1862. doi: 10.1111/trf.14783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sambandam S., Serbin P., Senthil T., et al. Patient characteristics, length of stay, cost of care, and complications in super-obese patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty: a national database study. CiOS Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery. 2023;15(3):380–387. doi: 10.4055/cios22180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shaka H., Ojemolon P.E. Impact of obesity on outcomes of patients with hip osteoarthritis who underwent hip arthroplasty. Cureus. 2020 doi: 10.7759/cureus.10876. Published online October 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jakuscheit A., Schaefer N., Roedig J., et al. Modifiable individual risks of perioperative blood transfusions and acute postoperative complications in total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Personalized Med. 2021;11(11) doi: 10.3390/jpm11111223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sizer S.C., Cherian J.J., Elmallah R.D.K., Pierce T.P., Beaver W.B., Mont M.A. Predicting blood loss in total knee and hip arthroplasty. Orthop Clin N Am. 2015;46(4):445–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aggarwal V.A., Sambandam S., Wukich D. The impact of obesity on total hip arthroplasty outcomes: a retrospective matched cohort study. Cureus. 2022 doi: 10.7759/cureus.27450. Published online July 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnson S.A., Jones A.E., Young E., et al. A risk-stratified approach to venous thromboembolism prophylaxis with aspirin or warfarin following total hip and knee arthroplasty: a cohort study. Thromb Res. 2021;206:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2021.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Le G., Yang C., Zhang M., et al. Efficacy and safety of aspirin and rivaroxaban for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip or knee arthroplasty: a protocol for meta-analysis. Medicine. 2020;99(49) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000023055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Heckmann N.D., Piple A.S., Wang J.C., et al. Aspirin for venous thromboembolic prophylaxis following total hip and total knee arthroplasty: an analysis of safety and efficacy accounting for surgeon selection bias. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38(7):S412–S419.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2023.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Available in a respository upon request.