Abstract

Background

Neck pain is common, disabling and costly. The effectiveness of electrotherapy as a physiotherapeutic option remains unclear. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2005 and previously updated in 2009.

Objectives

This systematic review assessed the short, intermediate and long‐term effects of electrotherapy on pain, function, disability, patient satisfaction, global perceived effect, and quality of life in adults with neck pain with and without radiculopathy or cervicogenic headache.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, MANTIS, CINAHL, and ICL, without language restrictions, from their beginning to August 2012; handsearched relevant conference proceedings; and consulted content experts.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), in any language, investigating the effects of electrotherapy used primarily as unimodal treatment for neck pain. Quasi‐RCTs and controlled clinical trials were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by The Cochrane Collaboration. We were unable to statistically pool any of the results, but we assessed the quality of the evidence using an adapted GRADE approach.

Main results

Twenty small trials (1239 people with neck pain) containing 38 comparisons were included. Analysis was limited by trials of varied quality, heterogeneous treatment subtypes and conflicting results. The main findings for reduction of neck pain by treatment with electrotherapeutic modalities were as follows.

Very low quality evidence determined that pulsed electromagnetic field therapy (PEMF) and repetitive magnetic stimulation (rMS) were more effective than placebo, while transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) showed inconsistent results.

Very low quality evidence determined that PEMF, rMS and TENS were more effective than placebo.

Low quality evidence (1 trial, 52 participants) determined that permanent magnets (necklace) were no more effective than placebo (standardized mean difference (SMD) 0.27, 95% CI ‐0.27 to 0.82, random‐effects model).

Very low quality evidence showed that modulated galvanic current, iontophoresis and electric muscle stimulation (EMS) were not more effective than placebo.

There were four trials that reported on other outcomes such as function and global perceived effects, but none of the effects were of clinical importance. When TENS, iontophoresis and PEMF were compared to another treatment, very low quality evidence prevented us from suggesting any recommendations. No adverse side effects were reported in any of the included studies.

Authors' conclusions

We cannot make any definite statements on the efficacy and clinical usefulness of electrotherapy modalities for neck pain. Since the evidence is of low or very low quality, we are uncertain about the estimate of the effect. Further research is very likely to change both the estimate of effect and our confidence in the results. Current evidence for PEMF, rMS, and TENS shows that these modalities might be more effective than placebo. When compared to other interventions the quality of evidence was very low thus preventing further recommendations.

Funding bias should be considered, especially in PEMF studies. Galvanic current, iontophoresis, EMS, and a static magnetic field did not reduce pain or disability. Future trials on these interventions should have larger patient samples, include more precise standardization, and detail treatment characteristics.

Keywords: Humans, Magnets, Electric Stimulation Therapy, Electric Stimulation Therapy/methods, Iontophoresis, Iontophoresis/methods, Magnetic Field Therapy, Magnetic Field Therapy/methods, Musculoskeletal Pain, Musculoskeletal Pain/therapy, Neck Pain, Neck Pain/therapy, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Whiplash Injuries, Whiplash Injuries/therapy

Plain language summary

Electrotherapy for neck pain

Background

Neck pain is common, disabling and costly. Electrotherapy is an umbrella term that covers a number of therapies using electric current that aim to reduce pain and improve muscle tension and function.

Study characteristics

This updated review included 20 small trials (N = 1239). We included adults (> 18 years old) with acute whiplash or non‐specific neck pain as well as chronic neck pain including degenerative changes, myofascial pain or headaches that stem from the neck. No index for severity of the disorders could be specified. The evidence was current to August 2012. The results of the trials could not be pooled because they examined different populations, types and doses of electrotherapy and comparison treatments, and measured slightly different outcomes.

Key results

We cannot make any definitive statements about the efficacy of electrotherapy for neck pain because of the low or very low quality of the evidence for each outcome, which in most cases was based on the results of only one trial.

For patients with acute neck pain, TENS possibly relieved pain better than electrical muscle stimulation, not as well as exercise and infrared light, and as well as manual therapy and ultrasound. There was no additional benefit when added to infrared light, hot packs and exercise, physiotherapy, or a combination of a neck collar, exercise and pain medication. For patients with acute whiplash, iontophoresis was no more effective than no treatment, interferential current, or a combination of traction, exercise and massage for relieving neck pain with headache.

For patients with chronic neck pain, TENS possibly relieved pain better than placebo and electrical muscle stimulation, not as well as exercise and infrared light, and possibly as well as manual therapy and ultrasound. Magnetic necklaces were no more effective than placebo for relieving pain; and there was no additional benefit when electrical muscle stimulation was added to either mobilisation or manipulation.

For patients with myofascial neck pain, TENS, FREMS (FREquency Modulated Neural Stimulation, a variation of TENS) and repetitive magnetic stimulation seemed to relieve pain better than placebo.

Quality of the evidence

About 70% of the trials were poorly conducted studies. The trials were very small, with a range of 16 to 336 participants. The data were sparse and imprecise, which suggests that results cannot be generalized to the broader population and contributes to the reduction in the quality of the evidence. Therefore, further research is very likely to change the results and our confidence in the results.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings: EMS.

| EMS + another treatment compared with that same treatment for neck pain | |||

|

Patient or population: Patients with subacute/chronic neck pain with or without radicular symptoms and cervicogenic headache Settings: Community USA Intervention: Electrical Muscle Stimulation (EMS) + another treatment Comparison: that same treatment | |||

| Outcomes | Effect | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Pain Intensity ‐ intermediate‐term follow‐up (about 6 months) | One trial with factorial design (multiple treatment meta‐analysis, I2 = 0%) showed no difference in pain intensity (pooled SMD 0.09, 95% CI Random ‐0.15 to 0.33) |

269 (1 study with factorial design of 4 independent comparisons) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

low Design: 0 Limitations: 0 Inconsistency: 0 Indirectness: 0 Imprecision: ‐1 Other: ‐1 |

|

Function intermediate‐term follow‐up |

One trial with factorial design (multiple treatment meta‐analysis, I2 = 0%) showed no difference in pain intensity (pooled SMD 0.09, 95% CI Random ‐0.15 to 0.33) |

269 (1 study with factorial design of 4 independent comparisons) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

low Design: 0 Limitations: 0 Inconsistency: 0 Indirectness: 0 Imprecision: ‐1 Other: ‐1 |

| Global Perceived Effect | Not measured | ||

|

Satisfaction intermediate‐term follow‐up |

One trial with factorial design (multiple treatment meta‐analysis, I2 = 0%) showed no difference in pain intensity (pooled SMD 0.02, 95% CI Random ‐0.22 to 0.26) |

269 (1 study with factorial design of 4 independent comparisons) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

low Design: 0 Limitations: 0 Inconsistency: 0 Indirectness: 0 Imprecision: ‐1 Other: ‐1 |

| Quality of life | Not measured | ||

| Adverse effects | No known study related adverse events | ||

|

Low quality: 1. Imprecision: Sparce EMS‐related data (‐1) 2. Other: 2x2x2 factorial design (8 groups; 3 of them with EMS plus another treatment; N= 336) No setting parameters for EMS; Treatment schedule unclear: " ...at least 1 treatment..." (manip / mob) No maximum, no average number of treatments reported (‐1) | |||

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings: static magnetic field (necklace).

| Static magnetic field (necklace) compared with placebo for neck pain | |||

|

Patient or population: Patients with chronic non‐specific neck pain Settings: Community USA ‐ Rehabilitation Institute Intervention: Static magnetic field (necklace) Comparison: placebo | |||

| Outcomes | Effect | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Pain Intensity immediate post‐treatment (3 weeks) |

One trial showed no difference in pain intensity (SMD 0.27, 95% CI Random ‐0.27 to 0.82) |

52 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

low Design: 0 Limitations: 0 Inconsistency: 0 Indirectness: ‐1 Imprecision: ‐1 Other: 0 |

| Function | Not measured | ||

|

Global Perceived Effect immediate post‐treatment (3 weeks) |

One trial showed no difference in global perceived effect (RR 0.85, 95% CI Random 0.48 to 1.50) |

52 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

low Design: 0 Limitations: 0 Inconsistency: 0 Indirectness: ‐1 Imprecision: ‐1 Other: 0 |

| Satisfaction | Not measured | ||

| Quality of life | Not measured | ||

| Adverse effects | Not reported | ||

|

Low quality: 1. Imprecision: Sparce data (‐1) 2. Directness: Single small trial (‐1) | |||

Background

For many years, electrotherapy has been commonly used as one of the physiotherapeutic options to treat neck pain. In contrast, little is known about its efficacy and efficiency. In our first review, published in 2005 (Kroeling 2005) and evaluating 11 publications, we found the evidence for all described modalities of electrotherapy either lacking, limited or conflicting. Our first update (Kroeling 2009) replaced the 2005 review and added seven recent publications, including studies on a new modality. Four studies (Ammer 1990; Chee 1986; Persson 2001; Provinciali 1996) that were included in the first review were excluded in the 2009 update, because studies of multimodal treatment were excluded; the unique contribution of the electrotherapy could not be identified. In our 2009 update (Kroeling 2009)18 small trials (1093 people with neck pain) were included. Analysis was limited by trials of varied quality, heterogeneous treatment subtypes and conflicting results.

Description of the condition

We studied neck pain that could be classified as either:

non‐specific mechanical neck pain, including whiplash associated disorders (WAD) category I and II (Spitzer 1987; Spitzer 1995), myofascial neck pain, and degenerative changes including osteoarthritis and cervical spondylosis (Schumacher 1993);

cervicogenic headache (Olesen 1988; Olesen 1997; Sjaastad 1990; or

neck disorders with radicular findings (Spitzer 1987; Spitzer 1995).

It can be classified as acute (less than 30 days), subacute (30 to 90 days) or chronic duration (longer than 90 days). Neck pain is typically provoked by neck movements and by physical examination provocation tests, and is located between the occiput to upper thoracic spine with the associated musculature.

Description of the intervention

Electrotherapy is a treatment category and may include: direct current, iontophoresis, electrical nerve stimulation, electrical muscle stimulation, pulsed electromagnetic fields, repetitive magnetic stimulation, and permanent magnets. Their underpinning mechanisms vary and are described in the following section.

How the intervention might work

1) Galvanic current for pain control

Treatment by direct current (DC), so‐called Galvanic current, reduces pain by inhibiting nociceptor activity (Cameron 1999). This effect is restricted to the area of current flow through the painful region. The main indication for Galvanic current is the treatment of acute radicular pain and inflammation of periarticular structures such as tendons and ligaments. Because DC enhances the transport of ionised substances through the skin, it can also be used to promote resorption of topical treatments, especially anti‐inflammatory drugs (iontophoresis).

2) Electrical nerve stimulation (ENS) or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for pain control

Alternating electrical current (AC) or modulated DC (so‐called Galvanic stimulation), mostly in the form of rectangular impulses, may inhibit pain‐related potentials at the spinal and supraspinal level, known as 'gate control'. This underpins all classical forms of stimulating electrotherapy (for example diadynamic current), as well as a modern form called TENS (including Ultra‐Reiz). While Galvanic current efficacy is restricted to the area of current flow, analgesic effects of ENS can be observed in the whole segmental region, both ipsilateral and contralateral (Cameron 1999; Kroeling 1998; Stucki 2000; Stucki 2007; Walsh 1997).

3) Electrical muscle stimulation

Most characteristics of EMS are comparable to TENS. The critical difference is in the intensity, which leads to additional muscle contractions. Primary pain relief via gate control can be obtained by EMS, TENS or other forms of ENS (Hsueh 1997). Rhythmic muscle stimulation by modulated DC, AC or interferential current probably increases joint range of motion (ROM), re‐educates muscles, retards muscle atrophy, and increases muscle strength. The circulation can be increased and muscle hypertension decreased, which may lead to secondary pain relief (Tan 1998).

4) Pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMF) and permanent magnets

Electricity is always connected with both electrical and magnetic forces. Alternating or pulsed electromagnetic fields induce electric current within the tissue. Even though these currents are extremely small, we recognize PEMF and the application of permanent magnets as forms of electrotherapy. Their main therapeutic purpose is for enhancement of bone or tissue healing and pain reduction.

5) Repetitive magnetic stimulation

Repetitive magnetic stimulation (rMS), in contrast to PEMF therapy, is a rather new (mid‐1980s) neurophysiologic technique that allows the transcutaneous induction of nerve stimulating electric currents. This technique requires extremely strong and sharp magnetic impulses (for example 15,000 amperes peak current; 2.5 T field strength; < 1 msec) applied by specially designed coils (< 10 cm) over the target area. Modern devices allow the repetition of up to 60 impulses per second. Mainly developed to study and influence brain functions, rMS also stimulates spinal chord fibres and peripheral nerves. Initial studies used peripheral rMS for therapeutic reasons, such as in myofascial pain syndrome (Pujol 1998; Smania 2003; Smania 2005). Since the resulting small electric impulses are the nerve stimulating factor, rMS effects may be similar to TENS and EMS.

Why it is important to do this review

Neck disorders with episodic pain and functional limitation (Hogg‐Johnson 2008) are common in the general population (Carroll 2008a; US Census Bureau 2012), in workers (Côté 2008) and in whiplash associated disorders (WAD) (Carroll 2008b). In a Canadian study, about 5% of cases revealed a clinically important disability (Côté 1998). There is a great impact on the work force; and 3% to 11% of claimants are off work each year (Côté 2008). Direct and indirect costs are substantive (Hogg‐Johnson 2008). Chronic pain accounts for about USD 150 to USD 215 billion each year in economic loss (that is lost workdays, therapy, disability) (NRC 2001; US Census Bureau 1996). The annual expenditure on medical care for back and neck conditions adjusted for inflation per patient increased by 95%, from USD 487 in 1999 to USD 950 in 2008 (Davis 2012). Yet very little is known about the effectiveness of most of the numerous available treatments still. Two systematic reviews have been published subsequent to ours. Teasell 2010 investigated acute whiplash while Leaver 2010 reviewed non‐specific neck pain. Neither review revealed any new data and agreed with our former update. There continues to be very little information on this topic. Therefore ongoing updates of this review are necessary.

Objectives

This systematic review assessed the short, intermediate and long‐term effects of electrotherapy on pain, function, disability, patient satisfaction, global perceived effect, and quality of life in adults with neck pain with and without radiculopathy or cervicogenic headache.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in any language. Quasi‐RCTs and controlled clinical trials (CCTs) were excluded.

Types of participants

The participants were adults, 18 years or older, who suffered from acute (less than 6 weeks), subacute (6 to 12 weeks) or chronic (longer than 12 weeks) neck pain categorized as:

non‐specific mechanical neck pain, including WAD category I and II (Spitzer 1987; Spitzer 1995), myofascial neck pain, and degenerative changes including osteoarthritis and cervical spondylosis (Schumacher 1993);

cervicogenic headache (Olesen 1988; Olesen 1997; Sjaastad 1990; and

neck disorders with radicular findings (Spitzer 1987; Spitzer 1995).

Studies were excluded if they investigated neck pain with definite or possible long tract signs, neck pain caused by other pathological entities (Schumacher 1993), headache that was not of cervical origin but was associated with the neck, co‐existing headache when either the neck pain was not dominant or the headache was not provoked by neck movements or sustained neck postures, or 'mixed' headaches.

Types of interventions

All studies used at least one type of electrotherapy: direct current, iontophoresis, electrical nerve stimulation; electrical muscle stimulation; pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMF), repetitive magnetic stimulation (rMS) and permanent magnets.

Interventions were contrasted against the following comparisons:

electrotherapy versus sham or placebo (e.g. TENS versus sham TENS or sham ultrasound);

electrotherapy plus another intervention versus that same intervention (e.g. TENS + exercise versus exercise);

electrotherapy versus another intervention (e.g. TENS versus exercise);

one type of electrotherapy versus another type (e.g. modulated versus continuous TENS).

Exclusion criteria

Other forms of high frequency electromagnetic fields, such as short wave diathermy, microwave, ultrasound and infrared light, were not considered in this review because their primary purpose is to cause therapeutic heat. Since electro‐acupuncture is a special form of acupuncture, it was also excluded. Multimodal treatment approaches that included electrotherapy were excluded if the unique contribution of electrotherapy could not be determined.

Types of outcome measures

The outcomes of interest were pain relief (for example a Numerical Rating Scale), disability (for example Neck Disability Index), function (for example activities of daily living) including work‐related outcomes (for example return to work, sick leave), patient satisfaction, global perceived effect and quality of life. Adverse events as well as costs of care were reported if available. The duration of follow‐up was defined as:

immediate post‐treatment (within one day);

short‐term follow‐up (closest to four weeks);

intermediate‐term follow‐up (closest to six months); and

long‐term follow‐up (closest to12 months).

Primary outcomes

The outcomes of interest were pain relief, disability, and function including work‐related outcomes.

Secondary outcomes

Patient satisfaction, global perceived effect and quality of life.

Search methods for identification of studies

References of retrieved articles were independently screened by two review authors. Note that our systematic review methodological design is consistent with the Cochrane Back Group methods.

Electronic searches

A research librarian searched computerized bibliographic databases without language restrictions for medical, chiropractic, and allied health literature. The search for this review was part of a comprehensive search on physical medicine modalities. These databases were searched for this update from December 2008 to August 2012.

We searched the following databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Manual Alternative and Natural Therapy (MANTIS). Subject headings (MeSH) and key words included anatomical terms (neck, neck muscles, cervical plexus, cervical vertebrae, atlanto‐axial joint, atlanto‐occipital joint, spinal nerve roots, brachial plexus); disorder and syndrome terms (arthritis, myofascial pain syndromes, fibromyalgia, spondylitis, spondylosis, spinal osteophytosis, spondylolisthesis, headache, whiplash injuries, cervical rib syndrome, torticollis, cervico‐brachial neuralgia, radiculitis, polyradiculitis, polyradiculoneuritis, thoracic outlet syndrome); treatment terms (multimodal treatment, electric stimulation therapy, transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation, rehabilitation, ultrasonic therapy, phototherapy, lasers, physical therapy, acupuncture, biofeedback, chiropractic, electric stimulation therapy); and methodological terms. See Appendix 1 for the full MEDLINE search strategy. We also searched trial registers such as ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP).

Searching other resources

We communicated with identified content experts, searched conference proceedings of the World Confederation for Physical Therapy 2011 and International Federation of Orthopaedic and Manipulative Therapists 2008. In addition, we searched our own personal files for grey literature.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently conducted citation identification and study selection. All forms were pre‐piloted. Each pair of review authors met for consensus and consulted a third author when there was persisting disagreement. Agreement (yes, unclear, no) was assessed for study selection using the quadratic weighted Kappa statistic, Cicchetti weights (Landis 1977).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently conducted data abstraction. Forms used were pre‐piloted. Data were extracted on the methods (RCT type, number analysed, number randomized, intention‐to‐treat analysis), participants (disorder subtype, duration of disorder), interventions (treatment characteristics for the treatment and comparison groups, dosage and treatment parameters, co‐intervention, treatment schedule), outcomes (baseline mean, reported results, point estimate with 95% confidence intervals (CI), power, side effects, costs of care) and notes (if authors were contacted or points of consideration related to the RCT). These factors are detailed in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We conducted the 'Risk of bias' assessment for RCTs using the criteria recommended by The Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins 2011) and the Cochrane Back Review Group (Furlan 2009) (see Appendix 2). At least two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias. A consensus team met to reach a final assessment. The following characteristics were assessed for risk of bias: randomisation; concealment of treatment allocation; blinding of patient, provider, and outcome assessor; incomplete data: withdrawals, dropout rate and intention‐to‐treat analysis; selective outcome reporting; other including similar at baseline, similar co‐interventions, acceptable compliance, similar timing of assessment. A study with a low risk of bias was defined as having low risk of bias on six or more of these items and no fatal flaws.

Measures of treatment effect

Standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated for continuous data while relative risks (RR) were calculated for dichotomous outcomes. We selected SMD over weighted mean difference (WMD) because we were looking across different interventions and most interventions used different outcome measures with different scales. For outcomes reported as medians, effect sizes were calculated using the formula by Kendal 1963 (p 237). When neither continuous nor dichotomous data were available, we extracted the findings and the statistical significance as reported by the author(s) in the original study.

In the absence of clear guidelines on the size of a clinically important effect, a commonly applied system by Cohen 1988 was used: small (0.20), medium (0.50) and large (0.80). A minimal clinically important difference between treatments for the purpose of the review was 10 points on a 100‐point pain intensity scale (small: WMD < 10%; moderate: 10% ≤ WMD < 20%; large: 20% ≤ WMD of the visual analogue scale (VAS)). For the neck disability index, we used a minimum clinically important difference of 7/50 neck disability index units. It is noted that the minimal detectable change varies from 5/50 for non‐complicated neck pain to 10/50 for cervical radiculopathy (MacDermid 2009). To translate effect measures into clinically meaningful terms and give the clinician a sense of the magnitude of the treatment effect, we calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) when the effect size was statistically significant (NNT: the number of patients a clinician needs to treat in order to achieve a clinically important improvement in one) (Gross 2002).

Unit of analysis issues

We performed one multiple treatment meta‐analysis for the Hurwitz 2002 trial that used a factorial design. We used a random‐effects model to allow for heterogeneity within each subgroup. An I2 statistic was also computed for subgroup differences. The data in the subgroups were independent.

Dealing with missing data

Where data were not extractable primary authors were contacted. See the 'Characteristics of included studies' table, 'Notes' for details. Missing data from Hurwitz 2002 and Chiu 2005 were obtained in this manner. No other data were requested. Missing data that were greater than 10 years old were not requested.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Prior to calculation of a pooled effect measure, we assessed the reasonableness of pooling on clinical grounds. The possible sources of heterogeneity considered were: symptom duration (acute versus chronic); subtype of neck pain (for example WAD); intervention type (for example DC versus pulsed); characteristics of treatment (for example dosage, technique); and outcomes (pain relief, measures of function and disability, patient satisfaction, quality of life). We were unable to perform any of these calculations because the data were incompatible.

Assessment of reporting biases

Occurrences of reporting biases were noted in the text and 'Characteristics of included studies' tables, 'Notes' column. Our review search methods addressed language bias; no additional languages were selected for this review. Funding bias was possible in three trials (Sutbeyaz 2006; Thuile 2002; Trock 1994). One trial from Spain was judged to have serious flaws and high risks of bias which may represent reporting bias (Escortell‐Mayor 2011).

Data synthesis

We assessed the quality of the body of the evidence using the GRADE approach, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and adapted in the updated Cochrane Back Review Group (CBRG) method guidelines (Furlan 2009). Domains that may decrease the quality of the evidence are: 1) study design, 2) risk of bias, 3) inconsistency of results, 4) indirectness (not to generalize), 5) imprecision (insufficient data), and 6) other factors (for example reporting bias). The quality of the evidence was reduced by a level based on the performance of the studies against these five domains (see Appendix 3 for definitions of these domains). All plausible confounding factors were considered as were their potential effects on the demonstrated treatment responses and the treatment dose‐response gradient (Atkins 2004). Levels of quality of evidence were defined as the following.

High quality evidence: there are consistent findings among at least 75% of RCTs with low risk of bias; consistent, direct and precise data; and no known or suspected publication biases. Further research is unlikely to change either the estimate or our confidence in the results.

Moderate quality evidence: one of the domains is not met. Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low quality evidence: two of the domains are not met. Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low quality evidence: three of the domains are not met. We are very uncertain about the results.

No evidence: no RCTs were identified that addressed this outcome.

We also considered a number of factors to place the results into a larger clinical context: temporality, plausibility, strength of association, dose response, adverse events, and cost. Clinical relevance was addressed for individual trials and reported either in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table or in the text.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We had also planned to assess the influence of risk of bias (concealment of allocation, blinding of outcome assessor), duration (acute, subacute, chronic), and subtypes of the disorder (non‐specific, WAD, degenerative change‐related, radicular findings, cervicogenic headache), but again data were too sparse. Since a meta‐analysis was not possible, sources of heterogeneity were not explored.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis or meta‐regression for (1) symptom duration, (2) methodological quality, and (3) subtype of neck disorder were planned but were not carried out because we did not have enough data in any one category.

Results

Description of studies

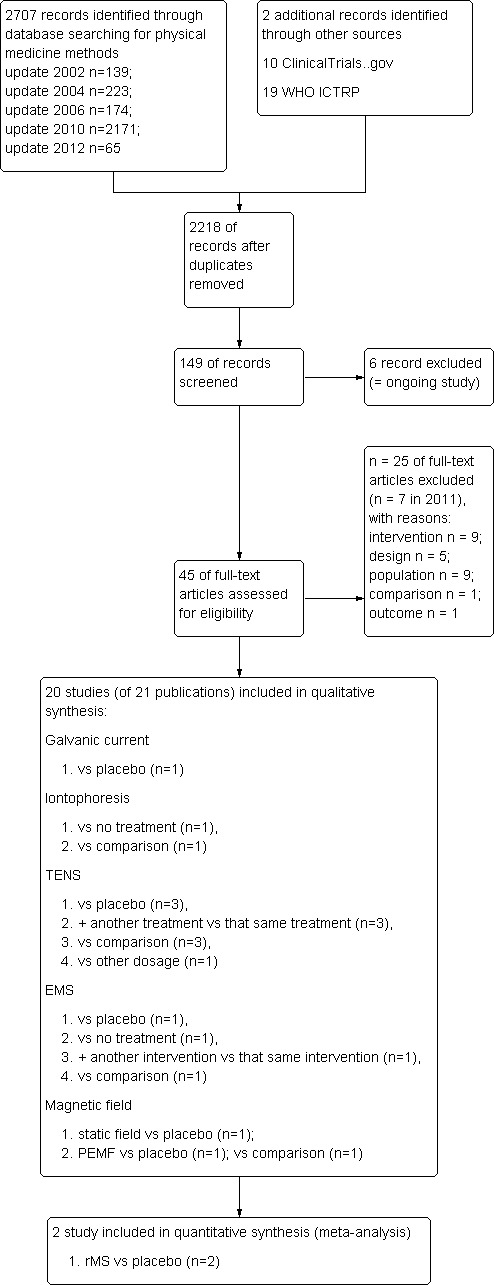

Twenty trials (1239 participants) were selected (Figure 1). The duration of the disorder, disorder subtypes and electrotherapy subtypes were as follows.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Acute whiplash associated disorders (WAD) with or without cervicogenic headache (n = 4): Fialka 1989, electrical muscle stimulation (EMS) and iontophoresis; Hendriks 1996, transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS); Foley‐Nolan 1992, pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF); Thuile 2002, PEMF.

Acute non‐specific neck pain (n = 1): Nordemar 1981, TENS.

Chronic myofascial neck pain (n = 5): Farina 2004, TENS; Hsueh 1997, TENS; Hou 2002, TENS; Smania 2003, repetitive magnetic stimulation (rMS); Smania 2005, rMS.

Chronic neck pain due to osteoarthritic cervical degenerative changes (n = 2): Trock 1994, PEMF; Sutbeyaz 2006, PEMF.

Chronic non‐specific neck pain (n = 5): Chiu 2005, TENS; Flynn 1987, TENS; Foley‐Nolan 1990, PEMF; Hong 1982, static magnetic field; Philipson 1983, modulated galvanic current.

Subacute or chronic neck pain with or without cervicogenic headache and radicular findings (n = 1): Hurwitz 2002, EMS.

Subacute or chronic non‐specific neck pain (n = 1): Escortell‐Mayor 2011.

One trial was translated from Danish (Philipson 1983). Three further non‐English trials (two French, one Italian) were subsequently excluded because they did not meet our criteria.

Six ongoing trials have been registered but not published (Triano 2009; Escortell 2011; Guayasamín 2013; Taniguchi 2010; Weintraub 2007).

Excluded studies

Twenty‐five studies were excluded (n = 7 in 2011). The reasons were: the intervention (n = 9) (Ammer 1990; Fernadez‐de‐las Penas2004; Forestier 2007a; Forestier 2007b; Klaber‐Moffett 2005; Persson 2001; Provinciali 1996; Vas 2006; Vikne 2007); population (n = 9) (Chen 2007; Coletta 1988; Gabis 2003; Hansson 1983; Jahanshahi 1991; Porzio 2000; Rigato 2002; Wang 2007; Wilson 1974); design (n = 5) (Chee 1986; Gonzales‐Iglesias 2009; Lee 1997; Vitiello 2007; Yip 2007); comparison (n = 1) (Dusunceli 2009); outcome (n = 1) (Garrido‐Elustondo 2010).

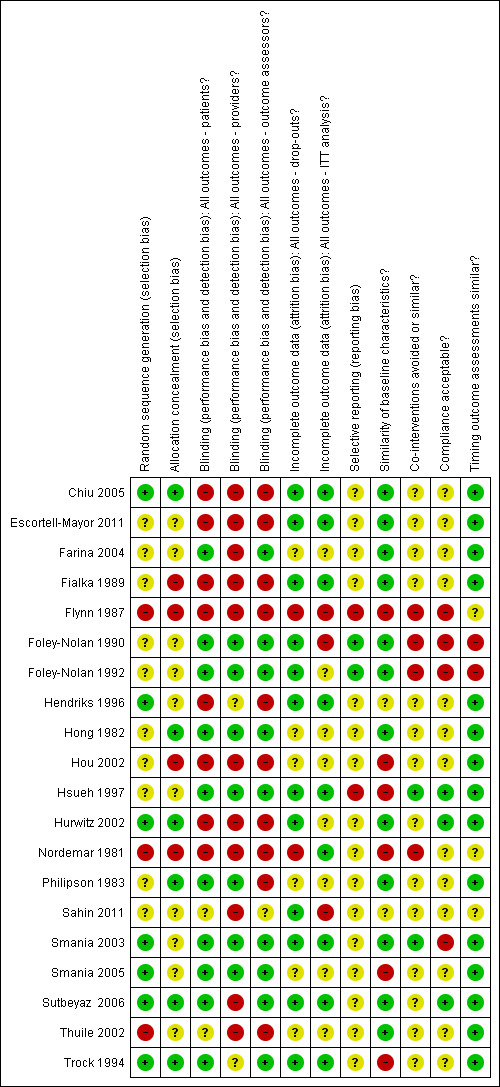

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

The allocation of concealment and reports on adequate randomisation were unclear in 60% of the trials (see also Figure 2).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each item for each included study.

Blinding

There was no clear reporting of blinding of patients (50%), providers (60%) or observers (60%).

Incomplete outcome data

In 50% of the trials there was attrition bias, when considering both dropouts (30%) and intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis (50%).

Selective reporting

Selective reporting was present or unclear in 80% of the trials.

Other potential sources of bias

In Trock 1994 their research support was listed as Bio‐Magnetic Systems, Inc. (co‐author Markoll was the principle shareholder of Bio‐Magnetic Sytems; Markoll and Trock were sentenced in 2001 for billing unapproved electromagnetic therapy (see FDA report: http://www.fda.gov/ora/about/enf_story/archive/2001/ch6/oci6.htm).

Effects of interventions

Galvanic current

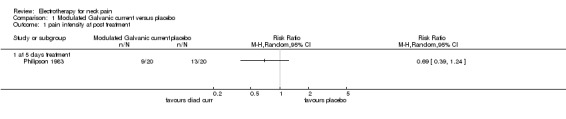

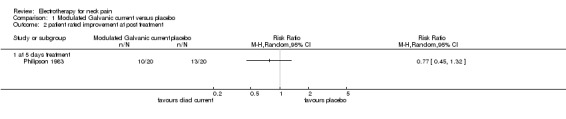

1. Modulated Galvanic current versus placebo

One study with a high risk of bias (Philipson 1983) assessed the effects of 'diadynamic' modulated Galvanic current (50 or 100 Hz) against placebo for patients with chronic pain in trigger points of the neck and shoulders.

Pain relief

No difference (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.24, random‐effects model) between the groups was found after a one‐week treatment.

Global perceived effect

No difference between the groups was noted immediately post‐treatment.

Conclusion: there was very low quality evidence of no difference in pain or global perceived effect when diadynamic modulated Galvanic current was evaluated at immediate post‐treatment.

Iontophoresis

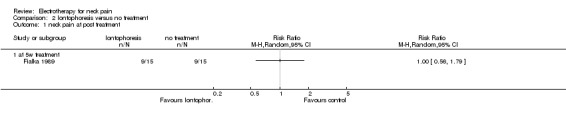

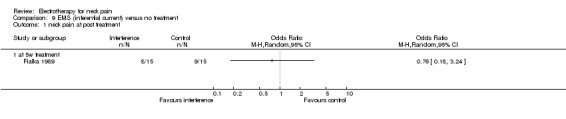

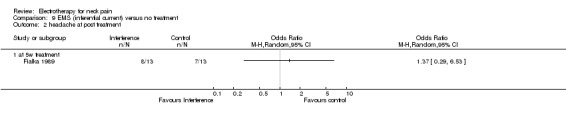

1. Iontophoresis versus no treatment

One study with a high risk of bias (Fialka 1989) assessed the effects of iontophoresis (DC combined with diclofenac gel) compared to no treatment for patients with acute WAD pain with or without cervicogenic headache.

Pain relief:

No difference between the groups was determined after a five‐week treatment.

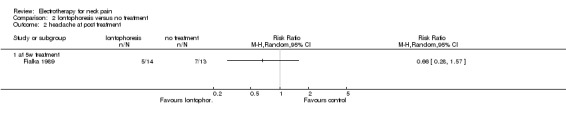

Cervicogenic headache

No difference (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.57, random‐effects model) between the groups was reported after a five‐week treatment.

Conclusion: very low quality evidence suggested that iontophoresis when compared to no treatment improved pain and headache for patients with acute WAD with or without cervicogenic headache.

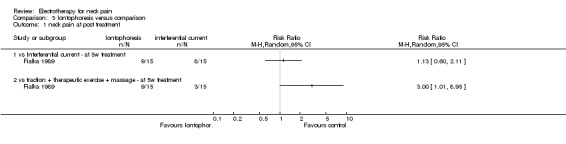

2. Iontophoresis versus comparison

One study with a high risk of bias (Fialka 1989) assessed the effects of iontophoresis (DC combined with diclofenac gel, same as above) against two other treatments: a) interferential current, and b) multimodal treatment (traction + therapeutic exercise + massage) for patients with acute WAD.

Pain relief

No difference between the groups was determined after a five‐week treatment period.

Cervicogenic headache

No difference between the groups was reported after five weeks of treatment.

Conclusion: there was very low quality evidence that iontophoresis improved pain or headache when contrasted against either interferential or a multimodal approach for acute WAD or cervicogenic headache.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

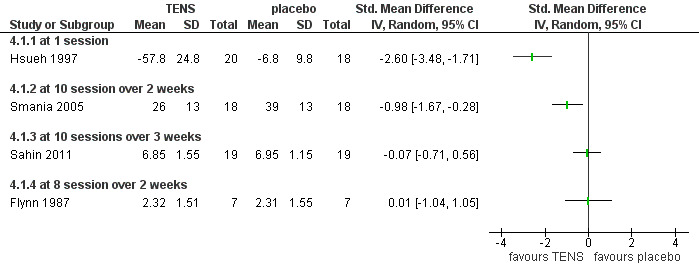

1. TENS versus placebo (sham control)

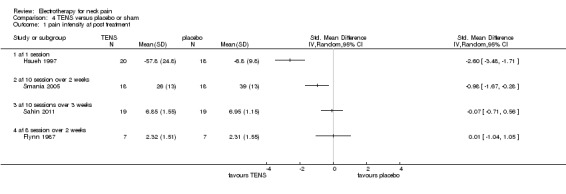

Two studies with low risk of bias (Hsueh 1997; Smania 2005) and two with high risk of bias (Flynn 1987; Sahin 2011) compared TENS to sham controls for patients with chronic neck pain.

Pain relief

All four trials reported immediate post‐treatment pain relief favouring TENS. The results varied and they could not be combined since they assessed outcomes of very different treatment schedules. One trial also reported short‐term pain relief, but our calculations did not support that (SMD ‐0.52, 95% CI ‐1.24 to 0.20, random‐effects model) (Smania 2005).

Conclusion: there was very low quality evidence (four trials with sparse and non‐generalizable data; group sizes between 7 and 22 participants) showing varied results for TENS therapy, with different frequencies and treatment schedules, immediately post‐treatment for patients with chronic neck pain.

2. TENS plus another treatment versus that same treatment

Three studies with high risk of bias utilized TENS (80 to 100 Hz) for individuals with chronic neck pain (Chiu 2005), myofascial neck pain (Hou 2002), and acute neck pain (Nordemar 1981). Another trial assessed TENS (Ultra‐Reiz, 143 Hz) for patients with acute WAD (Hendriks 1996). In these trials, TENS was added to other interventions received by both comparison groups (Chiu 2005: Infrared; Hou 2002: hot pack, exercises; Nordemar 1981: neck collar, exercises, analgesic; Hendriks 1996: standard physiotherapy).

Pain relief

Three trials reported no benefit of TENS at post‐treatment (Hou 2002), short (Nordemar 1981) and intermediate‐term (Chiu 2005) follow‐up. One trial (Hendriks 1996) favoured Ultra‐Reiz for pain relief in the short term. Due to different dosage parameters, data were not pooled.

Conclusion: there was very low quality evidence (two trials with group sizes between 10 and 13, one with no blinding and different treatment regimens) that the addition of TENS had no additional significant effect on pain relief in patients with acute to chronic neck pain, and that Ultra‐Reiz reduced pain for patients with acute WAD (one trial, 2 X 8 participants).

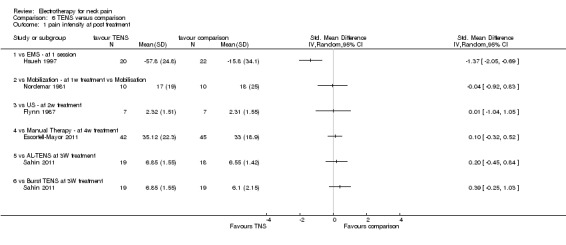

3. TENS versus comparison

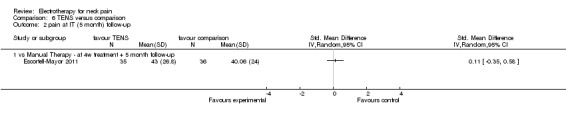

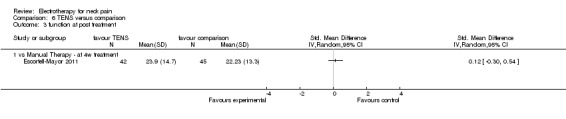

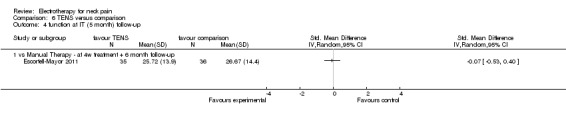

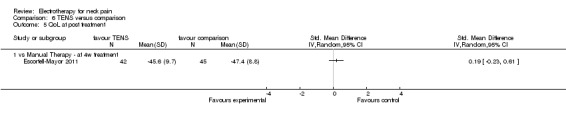

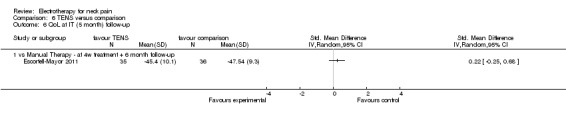

Three studies with high risk of bias compared TENS to EMS (Hsueh 1997), ultrasound (Flynn 1987) and manual therapy (Nordemar 1981) for treatment of acute and chronic neck pain. One study with high risk of bias (Escortell‐Mayor 2011) compared TENS to manual therapy for subacute and chronic neck pain.

Pain relief

TENS seemed superior to EMS (Hsueh 1997), but there was little or no difference between TENS and manual therapy (Nordemar 1981; Escortell‐Mayor 2011) or ultrasound (Flynn 1987).

Conclusion: there was very low quality evidence (trials with group sizes between 7 and 43 participants, sparse and non‐generalizable data) that TENS may relieve pain better than EMS, but there was little or no difference between the effects of TENS and manual therapy (low quality evidence) or ultrasound (very low quality evidence) for patients with acute or chronic neck pain. Due to different comparative treatments, the results of the trials could not be pooled.

4. TENS versus TENS (with different parameters)

One study with a low risk of bias (Farina 2004) examined the effects of TENS (100 Hz) against FREMS (a frequency and intensity varying TENS modification, 1 to 40 Hz) for chronic myofascial pain. Another study with high risk of bias (Sahin 2011) compared conventional TENS (100 Hz) with both acupuncture like (AL)‐TENS (4 Hz) and burst‐mode (Burst)‐TENS (100 Hz, 2 Hz) for chronic myofascial pain.

Pain relief

TENS and FREMS were both reported to be significantly effective for pain relief (VAS) after one week of treatment, and at one and three‐month follow‐up (Farina 2004). Conventional TENS showed no significant difference over AL‐TENS or Burst‐TENS after three weeks of treatment (Sahin 2011).

Conclusion: there was very low quality evidence (one trial, 19 + 21 participants; insufficient data reported) that FREMS and TENS were similarly effective for the treatment of chronic myofascial neck pain. There was very low quality evidence (one trial, two comparisons with 37 participants) that conventional TENS was similar to Burst‐TENS or AL‐TENS for chronic myofascial pain immediately post‐treatment.

Electrical Muscle Stimulation (EMS)

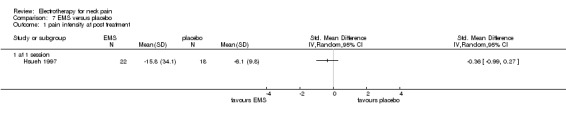

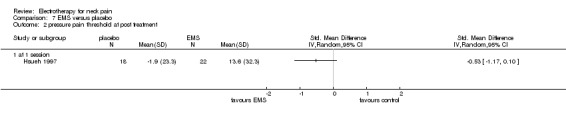

1. EMS versus placebo (sham control)

One trial with a low risk of bias (Hsueh 1997) studied the effects of a single EMS treatment (20 minutes,10 Hz) for chronic neck pain with cervical trigger points compared to sham control.

Pain relief

No difference for pain intensity and pressure threshold was found.

Conclusion: there was very low quality evidence (one trial, 22 + 18 participants) that a single treatment of EMS had no effect on trigger point tenderness compared to placebo treatment in patients with chronic neck pain.

2. EMS (interferential current) versus no treatment

One study with a high risk of bias described the effect of EMS (stereodynamic 50 Hz interferential current) (Fialka 1989) for acute WAD versus no treatment.

Pain relief

No difference between treated and untreated control patients was found for neck pain relief and headache.

Conclusion: there was very low quality evidence (one trial, 2 x 15 participants) that EMS neither reduced neck pain nor cervicogenic headache in patients with acute WAD, compared to no treatment.

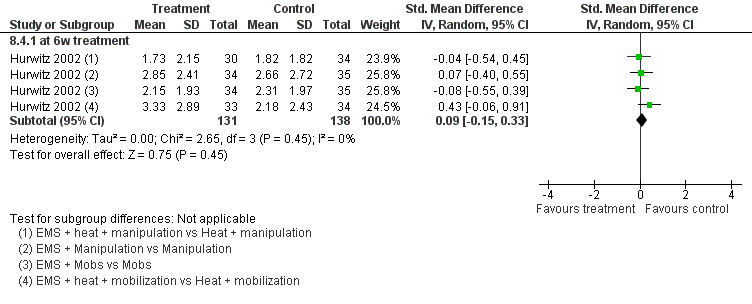

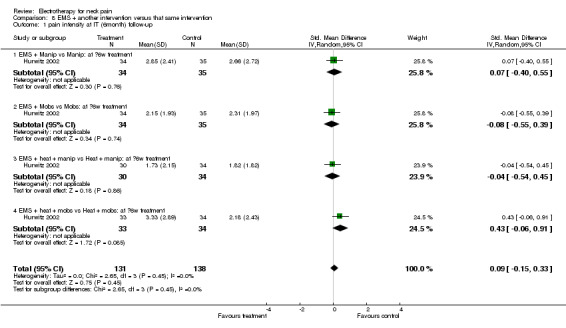

3. EMS plus another treatment versus the same treatment

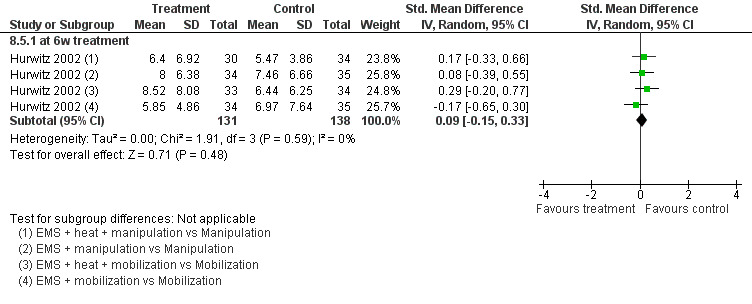

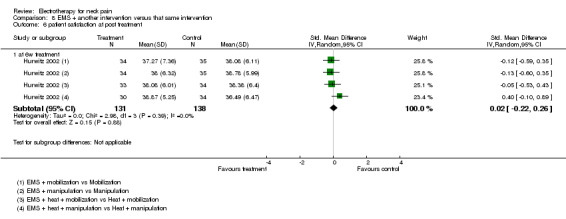

One 2 x 2 x 2 factorial design study with a low risk of bias (Hurwitz 2002) compared the effects of additional EMS on two independent groups with mobilisation and two independent groups with manipulation (each arm with or without moist heat) for patients with subacute to chronic neck pain with and without cervicogenic headache or radicular symptoms.

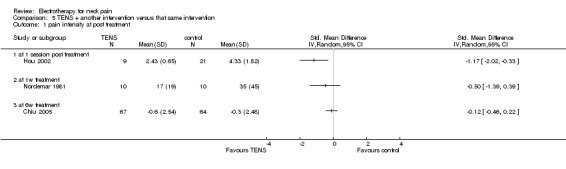

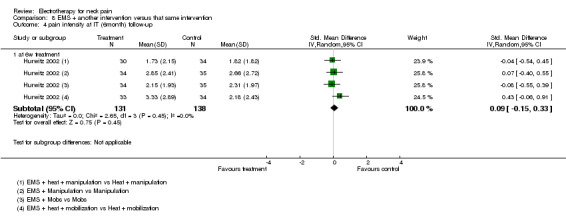

Pain relief

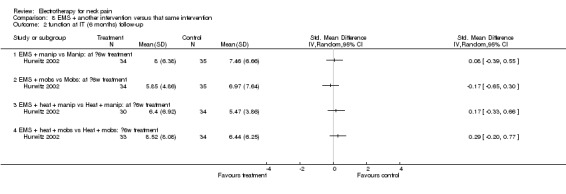

No differences between the groups were found at post‐treatment, short‐term and intermediate‐term follow‐up (Figure 3). A multiple treatment meta‐analysis from one factorial design of independent groups was pooled (SMD 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.33, random‐effects model) with an I2 of 0% at intermediate‐term follow‐up (Figure 4).

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 TENS versus placebo or sham, outcome: 4.1 pain intensity at post‐treatment.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 8 EMS + another intervention versus that same intervention, outcome: 8.4 pain intensity at IT (6‐month) follow‐up.

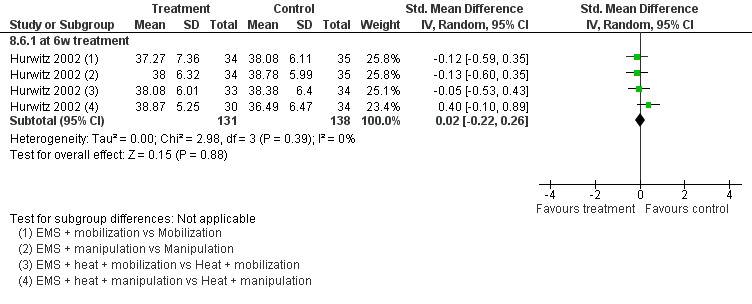

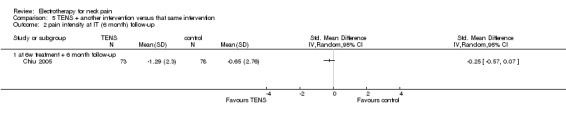

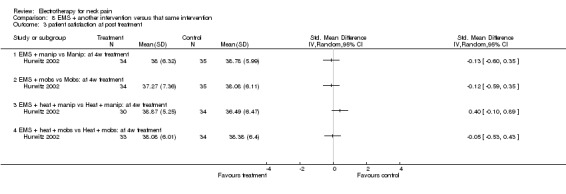

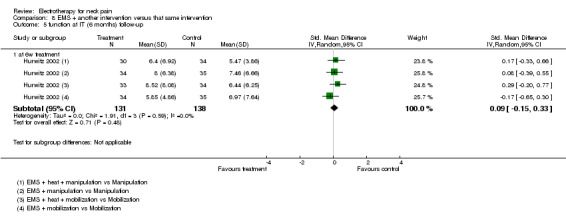

Function

No differences between the groups were found (pooled SMD 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.33, random‐effects model; I2 = 0%) at post‐treatment, short‐term and intermediate‐term follow‐up (Figure 5).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 8 EMS + another intervention versus that same intervention, outcome: 8.5 function at IT (6‐month) follow‐up.

Patient satisfaction

No differences between the groups were found (pooled SMD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.26, random‐effects model; I2 = 0%) at post‐treatment, short‐term and intermediate‐term follow‐up (Figure 6).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 8 EMS + another intervention versus that same intervention, outcome: 8.6 patient satisfaction at post‐treatment.

Conclusion: there was low quality evidence (1 factorial designed trial, N = 336; three EMS groups, N = ˜ 40; no EMS settings or treatment schedules reported) that EMS had no significant impact on pain relief, disability and patient satisfaction when used as an adjunct to cervical mobilisation and manipulation, at post‐treatment, short‐term and intermediate‐term follow‐up.

4. EMS versus comparison

One study with a low risk of bias compared the effect of EMS to TENS for chronic myofascial pain (Hsueh 1997), and one study with a high risk of bias to treatment with iontophoresis for patients with acute WAD (Fialka 1989; see above).

Pain relief

EMS was found to be inferior to TENS for pain relief immediately following treatment. No difference was found between EMS and Iontophoresis at post‐treatment and short‐term follow‐up.

Conclusion: there was very low quality evidence (one trial, 20 + 18 participants; one treatment only; poor clinical relevance) that EMS was inferior to TENS for pain relief of chronic neck pain. There was very low quality evidence (one trial, 2 x 15 participants) that there was no significant difference between EMS and iontophoresis for pain relief in acute WAD.

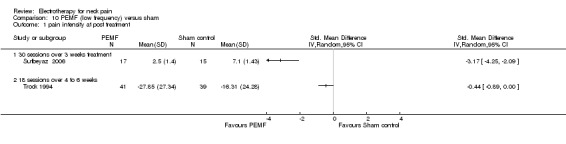

Pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF)

1. PEMF versus placebo or sham control

Two studies with a low risk of bias examined the efficacy of non‐thermal, high frequency PEMF (miniaturized high frequency (HF) generator, 27 MHz, 1.5 mW/cm²) treatment on patients with chronic neck pain (Foley‐Nolan 1990) and acute WAD (Foley‐Nolan 1992). Two other trials with a low risk of bias studied the efficacy of low frequency PEMF therapy (< 100 Hz) for participants with chronic cervical osteoarthritis pain (Sutbeyaz 2006; Trock 1994). All four studies were sham‐controlled by inactive devices.

Pain relief

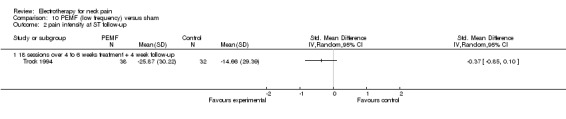

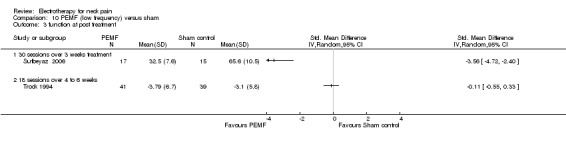

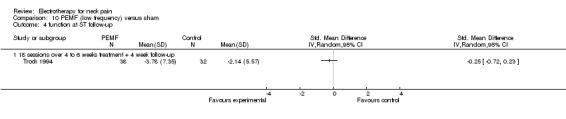

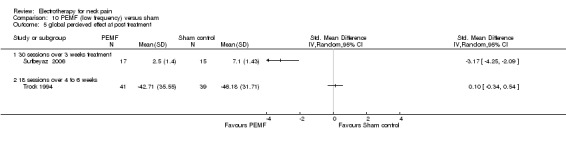

In their first trial, the authors (Foley‐Nolan 1990) found that pain intensity (VAS) was reduced post‐treatment. In their second trial (Foley‐Nolan 1992) no relevant effects were found. Trock 1994 reported significant pain relief after four to six weeks of treatment, but not at the one‐month follow‐up. Sutbeyaz 2006 reported significant pain relief, favouring the active PEMF group, after three weeks of treatment.

Function

Trock 1994 reported no differences in improvement in function.

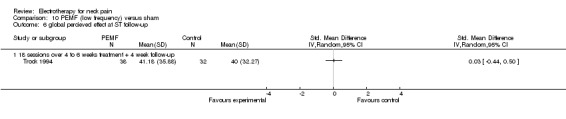

Global perceived effects

Trock 1994 and Sutbeyaz 2006 reported no differences in effects.

Conclusion: there was very low quality evidence that non‐thermal high frequency PEMF (27 MHz) reduced acute or chronic neck pain, and that low frequency PEMF (< 100 Hz) may have reduced pain from cervical spine osteoarthritis after some weeks of treatment. Even though these trials were rated as having a low risk of bias by our validity assessment team, they were imprecise, inconsistent and may have been influenced by other biases. The evidence rating was therefore reduced from moderate quality to very low for the following reasons: funding bias may have been present in Trock 1994 and Sutbeyaz 2006; the PEMF application (in a cervical collar worn 24 hours per day) in Foley‐Nolan 1990 and Foley‐Nolan 1992 was a very uncommon PEMF method using diathermy‐like HF‐pulses but with intensities far below the thermal threshold. The biological rationale for the chosen treatment was based on literature from 1940 and remains unclear.

2. PEMF versus comparison

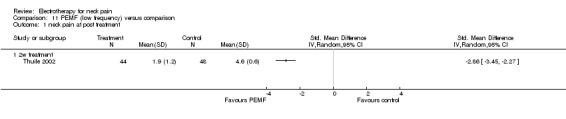

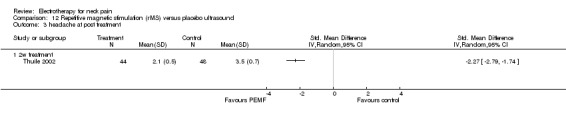

One study with a high risk of bias (Thuile 2002) compared low frequency PEMF (< 100 Hz) treatment versus a standard therapy for WAD patients.

Pain relief

Reported results favoured PEMF therapy for neck pain relief and headache reduction in patients with WAD.

Conclusion: there was very low quality evidence (one trial, 44 + 48 participants; no placebo control; funding bias unclear) that PEMF may have reduced WAD‐related neck pain and headache compared to a standard therapy.

Repetitive magnetic stimulation (rMS)

1. rMS versus placebo

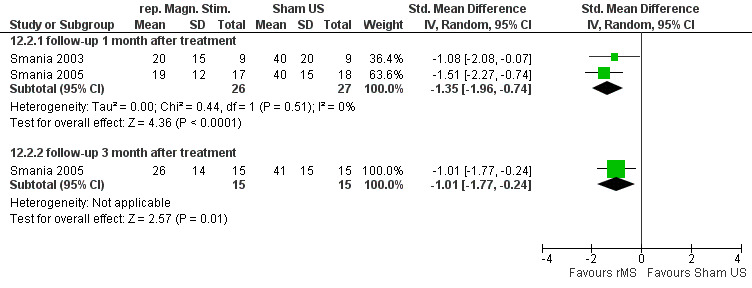

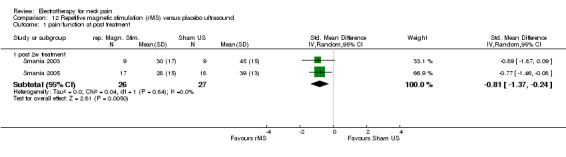

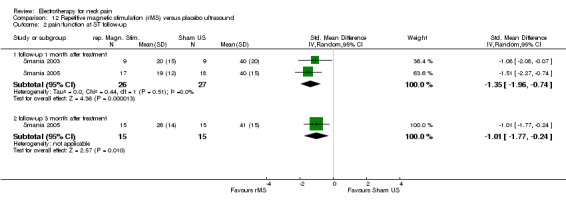

Two similar studies with a low risk of bias (Smania 2003; Smania 2005) evaluated rMS therapy (400 mT, 4000 pulses per session) for patients with myofascial neck pain against placebo ultrasound.

Pain relief and function

Pain and disability (VAS, Neck Pain Disability (NPD)) reduction by rMS was more effective than placebo for the treatment of myofascial neck pain at two weeks, one month (Figure 7) (pooled SMD ‐1.35, 95% CI ‐1.96 to ‐0.74, random‐effects model), and three months follow‐up.

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 12 Repetitive magnetic stimulation (rMS) versus placebo ultrasound, outcome: 12.2 pain and function at ST follow‐up.

Conclusion: we found very low quality evidence (two trials from the same research group, with sparse and non‐generalizable data, 9 to 16 participants in either group) that rMS was effective for a short‐term reduction of chronic neck pain and disability compared to placebo. However, although the NNT = 3 and treatment advantage was 46% to 56%, because of the low quality of the evidence one should treat the results with caution. Publication bias may be considered. Funding was not reported.

Static magnetic field

1. Static magnetic field (permanent magnets, necklace) versus sham control

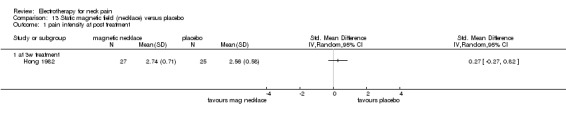

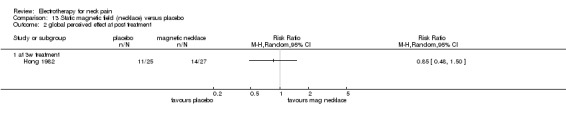

One study with a low risk of bias (Hong 1982) investigated the efficacy of a magnetic necklace (120 mT) on patients with chronic neck and shoulder pain compared to a sham control group with identical but non‐magnetic necklaces.

Pain relief

No differences (SMD 0.27, 95% CI ‐0.27 to 0.82, random‐effects model) were found between the groups (Figure 8).

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 13 Static magnetic field (necklace) versus placebo, outcome: 13.1 pain intensity at post‐treatment.

Conclusion: there was low quality evidence (one trial, 27 + 25 participants) that permanent magnets were not effective for chronic neck and shoulder pain relief.

Side effects

No adverse side effects were reported in any of the included studies evaluated above. However, studies were too small for a valid evaluation of adverse effects.

Costs

No costs were reported in any of the included studies evaluated above.

Discussion

Electrotherapy has been developed during the last two centuries. The systematic use of electric currents for therapeutic reasons began shortly after Luigi Galvani's observations (1780) that electric currents cause muscle contractions if stimulating efferent nerves. Since then, a growing variety of methods, including electromagnetic and magnetic agents, have been developed for a manifold of therapeutic reasons. Only a small selection of these methods have been investigated by the trials described above, direct or modulated Galvanic currents, iontophoresis, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), electrical muscle stimulation (EMS), low or high frequency pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMF), repetitive magnetic stimulation (rMS) and permanent magnets. A great deal of research in these fields has been published in the past 25 years (Cameron 1999), however only 20 trials examining the treatment of neck pain met our review criteria. Therefore, evidence for any of the modalities was found to be of low or very low quality, due to the size of the trials and the heterogeneity of the populations, interventions and outcomes. This precluded meta‐analysis and resulted in sparse data. The average sample size over all treatment groups was about 20 participants.

Summary of main results

For this review, there were 20 trials with 38 comparisons that met our inclusion criteria. No outcomes had high or moderate strength of evidence. The evidence for all electrotherapy interventions for neck pain is of low or very low quality, which means that we are very uncertain about the estimate of effect. Further research is very likely to have an important impact on this and our confidence in the results. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn regarding the effectiveness of electrotherapy for neck pain based on the available small trials. Large randomized controlled trials are needed to get a valid and precise estimate of the effect of electrotherapy for neck pain.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

In general, convincing, high or moderate quality evidence for any of the described modalities was lacking. Thirty‐eight comparisons in 20 studies examined seven different forms, and their modifications, of electrotherapy. Of the few studies that examined the same modalities, conclusions were limited by the heterogeneity of the treatment parameters or population. For example, the frequency for TENS ranged from 60 Hz to 143 Hz, with disorders from acute WAD to chronic myofascial pain. This heterogeneity made it impossible to pool the data and difficult to interpret the applicability of the results. More research needs to be done in order to confirm the positive findings, and to determine which treatment parameters are the most applicable and for which disorders.

Quality of the evidence

Performance and detection bias are the two dominant biases influencing our systematic review findings. Specifically, blinding of the patients and providers are essential considerations for future trials. Co‐interventions need to be avoided to establish clearer results.

Potential biases in the review process

Language bias was avoided by including all languages during study selection, however non‐English databases were not searched (that is Chinese databases).

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The evidence presented in this review needs to be compared to the evidence described in other reviews. The limited number of reviews on the subject makes it difficult to carry out that comparison. There was conflicting evidence in the results on PEMF (Sutbeyaz 2006; Thuile 2002; Trock 1994), such that the positive findings for PEMF were strongly doubted in other reviews (Hulme 2002; Schmidt‐Rohlfing 2000). We also have these concerns and caution the reader that funding bias may be present. In particular, research support was declared as being provided by Bio‐Magnetic Systems, Inc. Co‐author Markoll was principle shareholder of Bio‐Magnetic Sytems; Markoll and Trock were sentenced in 2001 for billing unapproved electromagnetic therapy (see FDA report:http://www.fda.gov/ora/about/enf_story/archive/2001/ch6/oci6.htm).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We cannot make any definitive statements on the efficacy and clinical usefulness of electrotherapy modalities for neck pain. Since the quality of the evidence is low or very low, we are uncertain about the estimates of the effect. Further research is very likely to change both the estimate of effect and our confidence in the results. Current evidence for rMS, TENS and PEMF shows that these modalities might be more effective than placebo but not other interventions, and funding bias has to be considered, especially in PEMF studies. Galvanic current, iontophoresis, electric muscle stimulation (EMS) and a static magnetic field did not reduce pain or disability.

Implications for research.

Due to a lack of consensus on parameters, and the restricted quality of most of the publications, additional studies need to be done to confirm the results described in this review. Possible new trials examining these specific interventions should include more participants and correct the internal validity and reporting shortcomings found in earlier randomized controlled trials. They should include more precise standardization and description of treatment characteristics.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 July 2013 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Updated literature search from 2009 to August 2012, 2 new publications were included, 7 publications were excluded. |

| 4 July 2013 | New search has been performed | 20 studies (21 publications) included in qualitative synthesis: galvanic current versus placebo (n = 1); iontophoresis versus no treatment (n = 1), versus comparison (n = 1); TENS versus placebo (n = 3), + another treatment versus that same treatment (n = 3), versus comparison (n = 3), versus other dosage (n = 1); EMS versus placebo (n = 1), versus no treatment (n = 1), + another intervention versus that same intervention (n = 1), versus comparison (n = 1); Static magnetic field versus placebo (n = 1); PEMF versus placebo (n = 1), versus comparison (n = 1); |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2003 Review first published: Issue 2, 2005

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 August 2009 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Inclusion criteria modified and contracted to clearly isolate the unique effect of electrotherapy, resulting in four publications excluded from the 2005 version of the review. An additional kind of electrotherapy was also identified (repetitive magnetic stimulation, rMS). However, there were no essential changes in conclusions ‐ the evidence neither supports nor refutes the efficacy of electrotherapy for the management of neck pain. Further research is very likely to change both the estimate of effect and our confidence in the results. |

| 15 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 14 June 2008 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We thank our volunteer translators and the Cochrane Back Review Group editors.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

Physical Medicine‐COG_NeckPain_

July 11 2010

1. Neck Pain/

2. exp Brachial Plexus Neuropathies/

3. exp neck injuries/ or exp whiplash injuries/

4. cervical pain.mp.

5. neckache.mp.

6. whiplash.mp.

7. cervicodynia.mp.

8. cervicalgia.mp.

9. brachialgia.mp.

10. brachial neuritis.mp.

11. brachial neuralgia.mp.

12. neck pain.mp.

13. neck injur*.mp.

14. brachial plexus neuropath*.mp.

15. brachial plexus neuritis.mp.

16. thoracic outlet syndrome/ or cervical rib syndrome/

17. Torticollis/

18. exp brachial plexus neuropathies/ or exp brachial plexus neuritis/

19. cervico brachial neuralgia.ti,ab.

20. cervicobrachial neuralgia.ti,ab.

21. (monoradicul* or monoradicl*).tw.

22. or/1‐21

23. exp headache/ and cervic*.tw.

24. exp genital diseases, female/

25. genital disease*.mp.

26. or/24‐25

27. 23 not 26

28. 22 or 27

29. neck/

30. neck muscles/

31. exp cervical plexus/

32. exp cervical vertebrae/

33. atlanto‐axial joint/

34. atlanto‐occipital joint/

35. Cervical Atlas/

36. spinal nerve roots/

37. exp brachial plexus/

38. (odontoid* or cervical or occip* or atlant*).tw.

39. axis/ or odontoid process/

40. Thoracic Vertebrae/

41. cervical vertebrae.mp.

42. cervical plexus.mp.

43. cervical spine.mp.

44. (neck adj3 muscles).mp.

45. (brachial adj3 plexus).mp.

46. (thoracic adj3 vertebrae).mp.

47. neck.mp.

48. (thoracic adj3 spine).mp.

49. (thoracic adj3 outlet).mp.

50. trapezius.mp.

51. cervical.mp.

52. cervico*.mp.

53. 51 or 52

54. exp genital diseases, female/

55. genital disease*.mp.

56. exp *Uterus/

57. 54 or 55 or 56

58. 53 not 57

59. 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 58

60. exp pain/

61. exp injuries/

62. pain.mp.

63. ache.mp.

64. sore.mp.

65. stiff.mp.

66. discomfort.mp.

67. injur*.mp.

68. neuropath*.mp.

69. or/60‐68

70. 59 and 69

71. Radiculopathy/

72. exp temporomandibular joint disorders/ or exp temporomandibular joint dysfunction syndrome/

73. myofascial pain syndromes/

74. exp "Sprains and Strains"/

75. exp Spinal Osteophytosis/

76. exp Neuritis/

77. Polyradiculopathy/

78. exp Arthritis/

79. Fibromyalgia/

80. spondylitis/ or discitis/

81. spondylosis/ or spondylolysis/ or spondylolisthesis/

82. radiculopathy.mp.

83. radiculitis.mp.

84. temporomandibular.mp.

85. myofascial pain syndrome*.mp.

86. thoracic outlet syndrome*.mp.

87. spinal osteophytosis.mp.

88. neuritis.mp.

89. spondylosis.mp.

90. spondylitis.mp.

91. spondylolisthesis.mp.

92. or/71‐91

93. 59 and 92

94. exp neck/

95. exp cervical vertebrae/

96. Thoracic Vertebrae/

97. neck.mp.

98. (thoracic adj3 vertebrae).mp.

99. cervical.mp.

100. cervico*.mp.

101. 99 or 100

102. exp genital diseases, female/

103. genital disease*.mp.

104. exp *Uterus/

105. or/102‐104

106. 101 not 105

107. (thoracic adj3 spine).mp.

108. cervical spine.mp.

109. 94 or 95 or 96 or 97 or 98 or 106 or 107 or 108

110. Intervertebral Disk/

111. (disc or discs).mp.

112. (disk or disks).mp.

113. 110 or 111 or 112

114. 109 and 113

115. herniat*.mp.

116. slipped.mp.

117. prolapse*.mp.

118. displace*.mp.

119. degenerat*.mp.

120. (bulge or bulged or bulging).mp.

121. 115 or 116 or 117 or 118 or 119 or 120

122. 114 and 121

123. intervertebral disk degeneration/ or intervertebral disk displacement/

124. intervertebral disk displacement.mp.

125. intervertebral disc displacement.mp.

126. intervertebral disk degeneration.mp.

127. intervertebral disc degeneration.mp.

128. 123 or 124 or 125 or 126 or 127

129. 109 and 128

130. 28 or 70 or 93 or 122 or 129

131. animals/ not (animals/ and humans/)

132. 130 not 131

133. exp *neoplasms/

134. exp *wounds, penetrating/

135. 133 or 134

136. 132 not 135

137. Neck Pain/rh [Rehabilitation]

138. exp Brachial Plexus Neuropathies/rh

139. exp neck injuries/rh or exp whiplash injuries/rh

140. thoracic outlet syndrome/rh or cervical rib syndrome/rh

141. Torticollis/rh

142. exp brachial plexus neuropathies/rh or exp brachial plexus neuritis/rh

143. 137 or 138 or 139 or 140 or 141 or 142

144. Radiculopathy/rh

145. exp temporomandibular joint disorders/rh or exp temporomandibular joint dysfunction syndrome/rh

146. myofascial pain syndromes/rh

147. exp "Sprains and Strains"/rh

148. exp Spinal Osteophytosis/rh

149. exp Neuritis/rh

150. Polyradiculopathy/rh

151. exp Arthritis/rh

152. Fibromyalgia/rh

153. spondylitis/rh or discitis/rh

154. spondylosis/rh or spondylolysis/rh or spondylolisthesis/rh

155. or/144‐154

156. 59 and 155

157. exp Combined Modality Therapy/

158. Exercise/

159. Physical Exertion/

160. exp Exercise Therapy/

161. exp Rehabilitation/

162. exp Physical Therapy Modalities/

163. Hydrotherapy/

164. postur* correction.mp.

165. Feldenkrais.mp.

166. (alexander adj (technique or method)).tw.

167. Relaxation Therapy/

168. Biofeedback, Psychology/

169. or/157‐168

170. 136 and 169

171. 143 or 156 or 170

172. animals/ not (animals/ and humans/)

173. 171 not 172

174. exp randomized controlled trials as topic/

175. randomized controlled trial.pt.

176. controlled clinical trial.pt.

177. (random* or sham or placebo*).tw.

178. placebos/

179. random allocation/

180. single blind method/

181. double blind method/

182. ((singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) adj25 (blind* or dumm* or mask*)).ti,ab.

183. (rct or rcts).tw.

184. (control* adj2 (study or studies or trial*)).tw.

185. or/174‐ 184

186. 173 and 185

187. limit 186 to yr="2006 ‐Current"

188. limit 186 to yr="1902 ‐ 2005"

189. guidelines as topic/

200. practice guidelines as topic/

201. guideline.pt.

202. practice guideline.pt.

203. (guideline? or guidance or recommendations).ti.

204. consensus.ti.

205. or/189‐204

206. 173 and 205

207. 136 and 205

208. 206 or 207

209. limit 208 to yr="2006 ‐Current"

210. limit 208 to yr="1902 ‐ 2005"

211. meta‐analysis/

212. exp meta‐analysis as topic/

213. (meta analy* or metaanaly* or met analy* or metanaly*).tw.

214. review literature as topic/

215. (collaborative research or collaborative review* or collaborative overview*).tw.

216. (integrative research or integrative review* or intergrative overview*).tw.

217. (quantitative adj3 (research or review* or overview*)).tw.

218. (research integration or research overview*).tw.

219. (systematic* adj3 (review* or overview*)).tw.

220. (methodologic* adj3 (review* or overview*)).tw.

221. exp technology assessment biomedical/

222. (hta or thas or technology assessment*).tw.

223. ((hand adj2 search*) or (manual* adj search*)).tw.

224. ((electronic adj database*) or (bibliographic* adj database*)).tw.

225. ((data adj2 abstract*) or (data adj2 extract*)).tw.

226. (analys* adj3 (pool or pooled or pooling)).tw.

227. mantel haenszel.tw.

228. (cohrane or pubmed or pub med or medline or embase or psycinfo or psyclit or psychinfo or psychlit or cinahl or science citation indes).ab.

229. or/211‐228

230. 173 and 229

231. limit 230 to yr="2006 ‐Current"

Appendix 2. Criteria for assessing risk of bias for internal validity (Higgins 2011)

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomized sequence

There is a low risk of selection bias if the investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process such as: referring to a random number table, using a computer random number generator, coin tossing, shuffling cards or envelopes, throwing dice, drawing of lots, minimisation (minimisation may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random).

There is a high risk of selection bias if the investigators describe a non‐random component in the sequence generation process, such as: sequence generated by odd or even date of birth, date (or day) of admission, hospital or clinic record number; or allocation by judgement of the clinician, preference of the participant, results of a laboratory test or a series of tests, or availability of the intervention.

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment

There is a low risk of selection bias if the participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because one of the following, or an equivalent method, was used to conceal allocation: central allocation (including telephone, web‐based and pharmacy‐controlled randomisation); sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; or sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes.

There is a high risk of bias if participants or investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments and thus introduce selection bias, such as allocation based on: using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; or other explicitly unconcealed procedures.

Blinding of participants

Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants during the study

There is a low risk of performance bias if blinding of participants was ensured and it was unlikely that the blinding could have been broken; or if there was no blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinding of personnel/ care providers (performance bias)

Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by personnel or care providers during the study

There is a low risk of performance bias if blinding of personnel was ensured and it was unlikely that the blinding could have been broken; or if there was no blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinding of outcome assessor (detection bias)

Detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors

There is low risk of detection bias if the blinding of the outcome assessment was ensured and it was unlikely that the blinding could have been broken; or if there was no blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding, or:

for patient‐reported outcomes in which the patient was the outcome assessor (e.g. pain, disability): there is a low risk of bias for outcome assessors if there is a low risk of bias for participant blinding (Boutron 2005);

for outcome criteria that are clinical or therapeutic events that will be determined by the interaction between patients and care providers (e.g. co‐interventions, length of hospitalisation, treatment failure), in which the care provider is the outcome assessor: there is a low risk of bias for outcome assessors if there is a low risk of bias for care providers (Boutron 2005);

for outcome criteria that are assessed from data from medical forms: there is a low risk of bias if the treatment or adverse effects of the treatment could not be noticed in the extracted data (Boutron 2005).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

Attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data

There is a low risk of attrition bias if there were no missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data were unlikely to be related to the true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data were balanced in numbers, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with the observed event risk was not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, the plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes was not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size, or missing data were imputed using appropriate methods (if drop‐outs are very large, imputation using even "acceptable" methods may still suggest a high risk of bias) (van Tulder 2003). The percentage of withdrawals and drop‐outs should not exceed 20% for short‐term follow‐up and 30% for long‐term follow‐up and should not lead to substantial bias (these percentages are commonly used but arbitrary, not supported by literature) (van Tulder 2003).

Selective Reporting (reporting bias)

Reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting

There is low risk of reporting bias if the study protocol is available and all of the study's pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way, or if the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon).

There is a high risk of reporting bias if not all of the study's pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not pre‐specified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis; the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study.

Group similarity at baseline (selection bias)

Bias due to dissimilarity at baseline for the most important prognostic indicators.

There is low risk of bias if groups are similar at baseline for demographic factors, value of main outcome measure(s), and important prognostic factors (examples in the field of back and neck pain are duration and severity of complaints, vocational status, percentage of patients with neurological symptoms) (van Tulder 2003).

Co‐interventions (performance bias)

Bias because co‐interventions were different across groups

There is low risk of bias if there were no co‐interventions or they were similar between the index and control groups (van Tulder 2003).

Compliance (performance bias)

Bias due to inappropriate compliance with interventions across groups

There is low risk of bias if compliance with the interventions was acceptable, based on the reported intensity/dosage, duration, number and frequency for both the index and control intervention(s). For single‐session interventions (e.g. surgery), this item is irrelevant (van Tulder 2003).

Intention‐to‐treat‐analysis

There is low risk of bias if all randomized patients were reported/analysed in the group to which they were allocated by randomisation.

Timing of outcome assessments (detection bias)

Bias because important outcomes were not measured at the same time across groups

There is low risk of bias if all important outcome assessments for all intervention groups were measured at the same time (van Tulder 2003).

Other bias

Bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table

There is a low risk of bias if the study appears to be free of other sources of bias not addressed elsewhere (e.g. study funding).

Appendix 3. Grading the quality of evidence ‐ definition of domains

Factors that might reduce the quality of the evidence

Study Design refers to type of study (i.e. randomized, observational study)

Limitations within Study Design (Quality) refers to the 12 risk of bias criteria noted in Appendix 2.

Consistency (heterogeneity) refers to the similarity of results across studies. When all studies are included in the meta‐analysis, ‘consistency’ is defined as absence of statistical heterogeneity. In the case that not all studies are combined in a meta‐analysis, ‘consistency’ is defined when all studies for the specific outcome lead to the same decision or recommendation, and ‘inconsistency’ is present if the results of two or more studies lead to clinically different decisions or recommendations. Authors use their judgment to decide if there is inconsistency when only one study leads to clinically different decision or recommendation.

Directness (generalizability) refers to the extent to which the people, interventions and outcome measures are similar to those of interest.

Precision of the evidence relates to the number of studies, patients and events for each outcome. Imprecise data is defined as:

Only one study for an outcome, regardless of the sample size or the confidence interval.

Multiple studies combined in a meta‐analysis: the confidence interval is sufficiently wide that the estimate is consistent with conflicting recommendations. For rare events one should consider the confidence interval around the risk difference rather than the confidence interval around the relative risk.

Multiple studies not combined in a meta‐analysis: the total sample size is underpowered to detect a clinically significant difference between those who received the index intervention compared to those who received the control intervention. In this case, a post‐hoc sample size calculation should be performed to determine the adequate sample size for each outcome.

Reporting (publication) bias should only be considered present if there is actual evidence of reporting bias rather than only speculation about reporting bias. The Cochrane Reporting Bias Methods Group describes the following types of Reporting Bias and Definitions:

Publication Bias: the publication or non publication of research findings, depending on the nature and direction of the results.

Time Lag Bias: the rapid or delayed publication of research findings, depending on the nature and direction of the results.

Language Bias: the publication of research findings in a particular language, depending on the nature and direction of the results.

Funding Bias: the reporting of research findings, depending on how the results accord with the aspirations of the funding body.

Outcome Variable Selection Bias: the selective reporting of some outcomes but not others, depending on the nature and direction of the research findings.

Developed Country Biases: the non publication or non indication of findings, depending on whether the authors were based in developed or in developing countries.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Modulated Galvanic current versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 pain intensity at post treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 at 5 days treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 patient rated improvement at post treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 at 5 days treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Modulated Galvanic current versus placebo, Outcome 1 pain intensity at post treatment.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Modulated Galvanic current versus placebo, Outcome 2 patient rated improvement at post treatment.

Comparison 2. Iontophoresis versus no treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 neck pain at post treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 at 5w treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 headache at post treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 at 5w treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Iontophoresis versus no treatment, Outcome 1 neck pain at post treatment.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Iontophoresis versus no treatment, Outcome 2 headache at post treatment.

Comparison 3. Iontophoresis versus comparison.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|