This qualitative study of medical records examines how decision-making occurs for hospitalized incarcerated persons lacking decisional capacity.

Key Points

Question

How does decision-making occur for hospitalized incarcerated persons lacking decisional capacity?

Findings

In this qualitative study of documentation for 43 hospitalized incarcerated persons without decisional capacity, prison employees appeared to have been involved in decisions for half of the admissions, including participating in family meetings and being asked to authorize invasive procedures.

Meaning

In this single-center cohort of hospitalized, incapacitated patients, carceral status appeared to have influenced decision-making practices, representing a threat to autonomy.

Abstract

Importance

Incarcerated patients admitted to the hospital face threats to their rights to privacy and self-determination in medical decision-making. Little is known about medical decision-making processes for hospitalized incarcerated persons who lack decisional capacity.

Objective

To characterize the prevalence of incapacity among hospitalized incarcerated patients and describe the decision-making processes, including who served as surrogate decision-makers, involvement of prison employees in medical decisions, and ethical concerns emerging from the patients’ care.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective descriptive and qualitative study of medical records for all patients admitted from prison for at least 24 hours between January 1, 1999, and September 1, 2019, at a large Midwestern academic medical center. Data analysis was performed from March 15, 2021, to December 14, 2022.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Prevalence of prison-to-hospital admissions for patients with a loss of capacity and characteristics of medical decision-making.

Results

During the 20-year study period, 462 patients from the prison were admitted to the hospital, totaling 967 unique admissions. Of these, 131 admissions (14%) involved patients with a loss of capacity and 43 admissions (4%, representing 34 unique patients) required surrogate decision-making. Ten of these patients had advance directives. Surrogate decision-makers often faced decisions about end-of-life care (n = 17) or procedural consent (n = 23). A family member was identified as surrogate decision-maker in 23 admissions. In 6 cases with a kindred surrogate, additional consent was requested from a prison employee. In total, prison employees were documented as being present during or participating in major medical decisions for half of the admissions. Five themes emerged from thematic analysis: uncertainty and misinformation about patient rights and the role of prison employees in medical decision-making with respect to these two themes, privacy violations, deference to prison officials, and estrangement from family and friends outside of the prison.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this first in-depth description, to date, of decision-making practices for hospitalized incarcerated patients lacking decisional capacity, admissions of these patients generated uncertainty about their rights, sometimes infringing on patients’ privacy and autonomy. Clinicians will encounter incarcerated patients in both hospital and clinic settings and should receive education on how to support ethically and legally sound decision-making practices for this medically vulnerable population.

Introduction

The US criminal legal system is contending with an increasing and rapidly aging incarcerated population with a high burden of chronic disease.1 Composing the largest incarcerated population in the world (2.2 million annually), this population is disproportionately Black and Hispanic, minoritized groups who experience disparately poor health outcomes compared with their White counterparts.2,3,4,5 Incarcerated individuals across the age spectrum experience increased prevalence of health conditions, from infectious diseases to substance dependence and mental health disorders, to higher rates of chronic medical conditions (eg, hypertension, asthma, and cancer).3,4

Between 2007 and 2010, the number of adults 65 years or older in the custody of state and federal criminal legal systems increased at a rate 94 times faster than the total sentenced US prison population.6 It is estimated that by 2030, adults older than 55 years will compose more than one-third of the population detained by the Federal Bureau of Prisons.7 Compared with their community-dwelling counterparts, incarcerated older adults are more likely to experience multimorbidity, as well as both cognitive and broader functional impairment that may lead to a loss of decisional capacity.4,8,9,10

Jails and prisons have varying capabilities to provide on-site medical care; incarcerated persons whose needs exceed the capabilities of their facility receive care in clinics and hospitals in neighboring communities.11 Care delivery in these settings may be complicated by policies and procedures imposed because of the patient’s carceral status. When the person in custody lacks decisional capacity, clinicians face challenges liaising with surrogate decision-makers and may be uncertain about the appropriate role of prison employees in care decisions.12

Medical decision-making practices for incapacitated incarcerated patients remain poorly understood. In this retrospective qualitative study, we establish the prevalence of incapacity among patients admitted from a federal medical center operated by the Federal Bureau of Prisons (providing specialized or long-term medical and psychiatric care) to a tertiary care center over a 20-year period, present demographic and clinical characteristics of incapacitated patients, and describe decision-making processes for these patients.

Methods

Study Cohort, Setting, and Data Collection

We identified the medical records of all persons admitted for at least 24 hours to Mayo Clinic, a large academic medical center in Minnesota, from a nearby federal medical center (hereafter, prison) between January 1, 1999, and September 1, 2019. Self-reported race and ethnicity were obtained from the medical record for each patient. Study data were collected using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database, a secure, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant web-based software database. This study was approved as minimal risk by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and determined to meet criteria for permissible research on incarcerated individuals under 45 CFR 46.305. This study followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) reporting guideline.

Primary Review

Electronic medical records from all admissions of incarcerated persons were reviewed by one of us (S.B.) to identify explicit documentation of lack of decisional capacity that either predated admission or occurred during the hospitalization. Loss of capacity was defined as inability to engage in medical decision-making, whether due to baseline absence of decisional capacity (eg, advanced dementia) or an acute medical cause, including sedation. Hospitalizations involving incapacity were reviewed to determine whether surrogate decision-making occurred, such as another individual providing consent for invasive medical intervention or changes to the therapeutic approach (eg, status or transition to hospice).

Secondary Review

Two of us (S.B. and J.D.D.) reviewed available documentation from all admissions involving incapacity and surrogate decision-making, meeting weekly for discussion of the identified content. The 2 researchers performed an iterative content analysis of all notes (eg, admission, consult, social work, and discharge notes) from each admission, using both inductive and deductive approaches to systematically identify and code relevant content using a spreadsheet (Excel; Microsoft Corp).13 A priori content identified for extraction at this stage included the nature of clinical situations requiring surrogate decision-making, the process of identifying and engaging surrogates (including the role of the prison in this process), all parties involved in decision-making for incapacitated patients, prevalence of advance directives, and consultation of hospital ethics or legal teams. All authors performed a final review of the content analysis for rigor.

Additionally, we conducted a thematic analysis of all documentation to identify ethical themes related to incapacity and incarceration. Two of us (S.B. and J.D.D.) reviewed each admission, developing an initial codebook of inductively identified ethical themes. These were synthesized into a final framework of 5 broad ethical themes by all authors, then applied to all admissions in this cohort. All authors participated in consensus meetings for agreement on ethical themes applied to each admission, including text excerpts from the medical record coded under each ethical theme. A final review of all admissions and coded excerpts was performed by all authors. The data analysis was performed between March 15, 2021, and December 14, 2022.

Results

Study Cohort

During the 20-year study period, 462 patients from the prison were admitted to the hospital, totaling 967 unique admissions (Figure 1). In 131 admissions (14%), the patient lacked decision-making capacity.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

Of 131 admissions involving incapacity, 88 did not have documentation of surrogate decision-making. These admissions often involved standard operative care preceded by informed consent with the patient, with an uncomplicated hospital course. The remaining 43 admissions (43 of 967 [4%]), among 34 unique patients, required engagement with a surrogate decision-maker.

Demographic Characteristics

Of the 34 patients who required a surrogate decision-maker, the median patient age was 58 years (mean [SD] age, 58.4 [15.6] years); all were men (Table 1). Among these patients, 1 (3%) identified as American Indian or Alaska Native, 1 (3%) as Black or African American, 10 (29%) as White, and 2 (6%) as other (not specified in the medical record); for 20 patients (59%), race and ethnicity were not reported. For most patients (28 [82%]), educational attainment was not documented in the medical record, although all categories of educational attainment were represented. Two patients had limited English proficiency, inferred by presence of an interpreter services flag in the medical record. Ten patients had an advance directive, corresponding to one-third of admissions (15 of 43 [35%]). Documented contact with the hospital’s ethics or legal services occurred in 5 admissions. Also, in 5 admissions, the consult liaison psychiatry service was engaged for formal capacity evaluation.

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients Who Required a Surrogate Decision-Maker.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) (N = 34) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 58.4 (15.6) |

| Male sex | 34 (100) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (3) |

| Black or African American | 1 (3) |

| White | 10 (29) |

| Othera | 2 (6) |

| Not reported | 20 (59) |

| Educational attainment | |

| High school diploma or GED | 2 (6) |

| Some college or 2-y degree | 1 (3) |

| College graduate, 4-y degree | 2 (6) |

| Some graduate studies or degree | 1 (3) |

| Not reported | 28 (82) |

| Limited English proficiency | 2 (6) |

| Advance directiveb | 10 (29) |

Abbreviation: GED, general educational development test.

Not specified in medical record.

Twelve documents were identified, including a health care directive (n = 8); living will and surrogate designation (n = 1); power of attorney (n = 1); surrogate appointment (n = 1); and a physician orders for life-sustaining therapy (n = 1).

Admissions Involving Loss of Capacity and Surrogate Decision-Making

Thirty-five of the 43 admissions involving loss of capacity and surrogate decision-making were for medical indications, with the remainder split equally between psychiatric (4) and surgical (4) indications. Additional detail on admission characteristics and loss of capacity is provided in the eTable in Supplement 1.

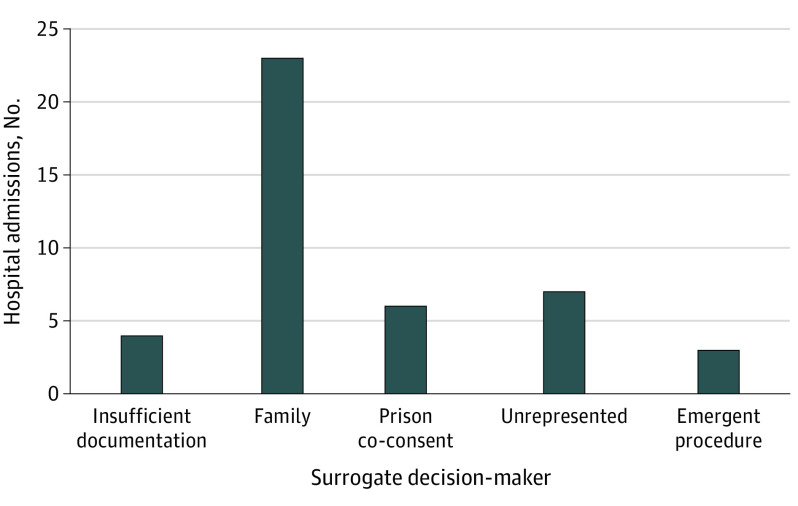

Surrogate Identification and Medical Decisions

Surrogate decision-makers most frequently were contacted for procedural consent (n = 23), decisions about end-of-life care (n = 17), or other treatment decisions (n = 3). Three admissions involved decisions for emergency surgery; a surrogate decision-maker was not contacted before surgery (Figure 2). Seven admissions were of unrepresented patients for whom no surrogate was ever identified. Guardianship was not pursued for any of these patients. Instead, the inpatient medical team and prison employees (ie, officials or medical personnel) collaborated in decision-making. The principal surrogate decision-maker(s) was identified as a family member in 23 of 43 admissions. For 4 admissions, documentation was too limited to characterize whether a surrogate decision-maker was ever identified.

Figure 2. Who Made Decisions and What Types of Decisions They Faced.

Surrogate decision-makers for incarcerated patients without decisional capacity. Decision-makers faced decisions about procedural consent in 23 of 43 hospitalizations and end-of-life or code status change in 17 of 43 hospitalizations. In the remaining 3 cases, their decisions related to psychiatric or other medical care.

Prison Involvement in Medical Decision-Making

In 17 admissions, involvement of prison employees appeared to be limited to facilitating contact with surrogates (Figure 3). In 22 admissions, prison employees were involved in decision-making. For instance, in 6 admissions, the clinical team documented that consent was requested of a prison employee, even though a family member had already consented on behalf of the patient. The prison was also contacted for consent before each of the 3 emergency surgical procedures in the cohort, although there was no documented attempt to reach a surrogate before surgery. Prison employees collaborated with the inpatient clinical team to reach decisions for the 7 unrepresented patients. In 6 cases in which family was already engaged in surrogate decision-making and ultimately served as the primary decision-makers, prison employees (typically medical personnel) were documented to have been present at family meetings, although their contributions were unclear.

Figure 3. Involvement of Prison Employees in Medical Decision-Making.

Prison employees (prison officials or medical personnel [Prison]) were involved in medical decision-making for 22 of 43 admissions. At times, this involved collaboration with the inpatient team (Hospital) to determine best interest for unrepresented patients (n = 7) or requesting consent for emergent procedures (n = 3). Prison employees were also involved in 12 cases in which patients’ families (Family) were already actively engaged in decision-making through providing additional consent (n = 6) or involvement at family meetings with the clinical team (n = 6). In an additional 17 admissions, prison involvement was limited to facilitating contact with a surrogate decision-maker only, with no additional involvement in medical decisions. For 4 admissions (not depicted in this figure), documentation was insufficient to determine whether a surrogate was identified.

Themes of Medical Decision-Making

Five major themes surrounding medical decision-making for incarcerated patients emerged from our analysis (Table 2). At times, more than 1 theme was present during an admission.

Table 2. Themes of Medical Decision-Making for Hospitalized Incarcerated Patients.

| Theme | Definition | Quotes from medical recorda |

|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty | Statements of uncertainty regarding (1) rights of incarcerated patient to make autonomous medical decisions and (2) appropriate role of prison employees in medical decision-making |

|

| Misinformation | Statement of incorrect information regarding (1) rights of incarcerated individuals to make autonomous medical decisions and (2) appropriate role of prison employees in medical decision-making |

|

| Privacy | Description of a breach of the patient’s privacy |

|

| Deference | Deferring to the prison, deviation from standard decision-making practices in reference to the prison |

|

| Estrangement | Evidence that patient has severely limited contact or strained relationship with persons outside of the prison |

|

Abbreviations: DNI, do not intubate order; DNR, do not resuscitate order; LP, lumbar puncture.

Italics indicates specific content that demonstrates a violation or problematic content related to the theme.

Physicians often documented their own confusion (uncertainty), and less commonly, made inaccurate assertions (misinformation) about how carceral status influences standard medical decision-making practices, the role of prison employees in decision-making for incarcerated patients, and whether decisional authority might ultimately fall to the prison. These statements were even found in cases in which the care team was already in contact with the patient’s family. Occasionally, misinformation about the role of the prison in decision-making appeared to originate from a prison employee. Some physicians documented their intention to clarify the rights of incarcerated patients with the legal or ethics department; all consultations confirmed that medical decisions were not to be made by prison employees.

Physicians also lacked clarity about whether incarcerated patients or their surrogates could decline life-sustaining interventions. Patients themselves were documented to have questioned how their carceral status would impact their ability to make their own medical decisions and what role the prison should play (uncertainty). Additionally, carceral status was mentioned when it had no relevance to the patient’s care or decision-making (eg, whether a suicidal patient lacked capacity to decline life-saving care on the basis of mental illness or because of his criminal legal status). Even when patients’ or surrogates’ preferences about clinical decisions were known, some physicians took special care to solicit and document permission to follow those wishes from prison employees (deference). For instance, we found a consent form signed by a patient’s family member, and a later (duplicate) consent for the procedure completed by a prison physician. In 6 of 29 hospitalizations in which the principal decision-makers were family members, physicians documented additional efforts to obtain consent from prison employees. Identifying a surrogate was difficult in cases in which the patient was estranged from family. Some family members expressed unwillingness to participate in the patient’s care, whereas in other cases, extensive outreach to family was unsuccessful (estrangement).

Some medical records documented engaging bedside corrections officers for elements of history taking. They were also asked to assist with patient positioning for physical examination, and to relay medical information back and forth to prison medical professionals (privacy).

Discussion

From this qualitative study involving a review of 20 years of medical records for hospitalized incarcerated patients lacking decisional capacity, we found that prison employees appeared to have played some role in medical decisions in half of the admissions. Physician uncertainty, deference to prison authority, and occasional erroneous assertions about carceral status constitute unique challenges to patient autonomy when incarcerated people interface with physicians outside of correctional settings. Our findings raise important questions about how carceral status influences inpatient medical care, particularly of incapacitated adults.

Ethically Appropriate Care of Hospitalized Incarcerated Patients

Incarcerated persons have a constitutionally afforded right to community-standard health care. Likewise, they have a legally protected right to make their own health care decisions, including the decision to refuse life-sustaining interventions.14 They maintain the right to appoint a surrogate decision-maker.12 Identifying an appropriate surrogate when none has previously been named is often complicated by estrangement, as occurred in several cases in this cohort.14

For persons in the custody of federal prisons, surrogate appointment follows the laws of the state in which the person is detained.15,16 Some states are explicit about who may serve as a surrogate for incarcerated persons, including several states with prohibitions on correctional staff serving in this role.17 Although we were able to identify cases of surrogate decision-making that were consistent with ethical and legal standards, others deviated from these standards.

Our analysis suggests poor physician awareness of ethical principles and legal rights relevant to caring for hospitalized adults in custody, including the proper role of the prison in medical decision-making. Prison involvement ranged from ethically acceptable to questionable or unnecessary, to possible violations of ethical practice. Although it is appropriate for prison employees to facilitate contact with documented surrogates or next of kin and coordinate logistics of patient care, further involvement in medical decisions is not broadly supported by ethical and legal standards for medical decision-making, unless the individual involved is a person uniquely qualified to speak to the patient's goals, preferences and values, such as a physician or social worker with close knowledge of the patient.18 Prison employees were also frequently present at multidisciplinary family meetings. Although their contributions to those meetings were poorly documented, their presence in these medical discussions raises questions about prison employees’ role in patient care decisions.

Societal deference to law enforcement may impede clinicians’ willingness to support patients’ rights at the bedside, especially if they lack the training to delineate between legal practices and unnecessary measures that infringe on the rights of incarcerated patients. It is notable that many clinicians mentioned this uncertainty in their medical documentation. This confusion seemed to have been shared by the hospital team, bedside officers, and prison employees, although at times, prison employees were documented to have corrected clinicians who inappropriately sought their consent. Some clinicians recognized their lack of familiarity with the rights of incarcerated patients and what the role of the prison in the decision-making process should be, consulting with the ethics and legal departments for education and clarity.

Enhanced awareness of the appropriate role of all stakeholders (eg, the surrogate[s], clinician, bedside corrections officers, and prison employees) in the care and medical decision-making for this medically vulnerable population may improve care and reduce instances of inappropriate deviation from standard practices (eg, asking bedside corrections officers for a patient’s medical history or inviting nonmedical prison employees to participate in family meetings). It is essential that clinicians have access to resources to understand the role of prison employees in the care of their patients, not only to ensure the rights of patients in their care are upheld, but also to maintain collegial and respectful relationships with prison employees responsible for the custody and welfare of the individual.

Notably, we identified instances of collaborative communication between the clinical team and prison employees, including navigating complexities of estrangement from family members to identify an appropriate surrogate. Likewise, the medical teams at the hospital and prison worked together to reach decisions for unrepresented patients in a manner that appeared to have been deliberative. There are situations in which this type of prison involvement could be appropriate (eg, if medical professionals or social workers at the prison are able to share previous conversations or observations of the patient’s preferences and values). If no such insight is available from prison employees, it is appropriate for decisions for unrepresented incarcerated patients to follow the hospital’s standard practices for unrepresented patients.

Implications for Patient Care

Most medical professionals receive little to no formal education about carceral health care.19,20,21,22 Prison employees and bedside corrections officers cannot be expected to be experts in the law and ethics of correctional health and would likely also benefit from professional development and education on these topics. The relatively infrequent nature of these inpatient encounters, as illustrated in the 20-year time frame of this study, likely contributed to practice inconsistency and clinicians’ unfamiliarity with legal and ethical standards.

People who are incarcerated have a right to privacy under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act with some exceptions, including coordination of care, the health and safety of staff, and the safety and security of the correctional facility.23 Incarcerated patients are accompanied by corrections officers to maintain custody and security. With few exceptions, a patient’s medical status should not be discussed with corrections officers to prevent violations of privacy, which were frequently documented in our cohort.24,25,26,27,28,29 The use of physical restraints (handcuffs and ankle shackles) or knowledge that the corrections officer is carrying a weapon may further distort the dynamic at the patient’s bedside.

Our findings suggest that a knowledge gap exists over how to justly navigate health care decisions for hospitalized incarcerated patients, particularly those who lack decisional capacity. Carceral status appeared to influence the care of patients, leading to deviations from standard practices for incapacitated patients. Although the overall prevalence of documented, potentially inappropriate prison involvement in decision-making was low over the 20-year period, it is nevertheless concerning. We did not assess the 836 admissions without a documented loss of capacity. Based on the findings of other authors,11,19,24,28 we would expect that issues of clinician uncertainty and infringement on privacy and autonomy were not limited to incapacitated patients.

Clinicians can ensure protection of incarcerated patients’ rights and dignity by using person-first language; recognizing the power differential in clinician–patient–correctional officer interactions; familiarizing themselves with their institutions’ policies for caring for incarcerated persons; respectfully asking bedside corrections officers to step farther away during sensitive conversations or examinations; liaising with medical professionals at the correctional institution to coordinate care, but not mistaking prison employees for surrogate decision-makers; and modeling compassion during patient interactions.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first in-depth description of decision-making practices for hospitalized incarcerated patients lacking decisional capacity. This study describes incarcerated and incapacitated patients from a single prison and hospital, limiting generalizability; patients at a federal medical center may have greater medical needs than other incarcerated populations. Findings may be influenced by local policies and practice patterns. Decisional incapacity is difficult to ascertain from medical record review. Patients were excluded unless incapacity was clearly reported, likely resulting in underestimation of true prevalence. We were limited by medical record documentation. In addition, documentation of decision processes was variable; when the extent of prison involvement was unclear, it was assumed the prison was not involved.

Conclusions

Community and academic clinicians care for incarcerated patients in both clinic and inpatient settings, including patients lacking decisional capacity. Our findings raise questions about how care decisions are navigated for incarcerated patients during acute care hospitalization nationally, warranting further investigation. Ensuring ethically and legally sound standards are upheld for incarcerated patients who lack decisional capacity will require enhanced instruction in carceral health care for medical professionals. Hospitals with high volumes of incarcerated patients should review formal policies with hospital staff or conduct joint training sessions with correctional employees, and they should conduct retrospective reviews of the care of incarcerated patients to ensure it meets medical, legal, and ethical standards.

eTable. Admission Characteristics

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Mitka M. Aging prisoners stressing health care system. JAMA. 2004;292(4):423-424. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fair H, Walmsley R. World Prison Population List. 13th ed. Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research; 2021. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/world_prison_population_list_13th_edition.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wildeman C, Wang EA. Mass incarceration, public health, and widening inequality in the USA. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1464-1474. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30259-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binswanger IA, Redmond N, Steiner JF, Hicks LS. Health disparities and the criminal justice system: an agenda for further research and action. J Urban Health. 2012;89(1):98-107. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9614-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carson EA. Prisoners in 2021—statistical tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2022. NCI 305125:1-50. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/documents/p21st.pdf

- 6.Fellner J, Vinck P. Old behind bars: the aging prison population in the United States. Human Rights Watch. January 27, 2012. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/01/28/old-behind-bars/aging-prison-population-united-states

- 7.Chettiar IM, Bunting WC, Schotter G. At America’s expense: the mass incarceration of the elderly. American Civil Liberties Union. June 2012. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.aclu.org/report/americas-expense-mass-incarceration-elderly

- 8.Colsher PL, Wallace RB, Loeffelholz PL, Sales M. Health status of older male prisoners: a comprehensive survey. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(6):881-884. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.82.6.881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perez A, Manning KJ, Powell W, Barry LC. Cognitive impairment in older incarcerated males: education and race considerations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(10):1062-1073. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams BA, Lindquist K, Sudore RL, Strupp HM, Willmott DJ, Walter LC. Being old and doing time: functional impairment and adverse experiences of geriatric female prisoners. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(4):702-707. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00662.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haber LA, Erickson HP, Ranji SR, Ortiz GM, Pratt LA. Acute care for patients who are incarcerated: a review. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(11):1561-1567. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scarlet S, DeMartino ES, Siegler M. Surrogate decision making for incarcerated patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(7):861-862. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dober G. Beyond Estelle: medical rights for incarcerated patients. Prison Legal News. November 4, 2019. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2019/nov/4/beyond-estelle-medical-rights-incarcerated-patients/

- 15.Program statement 6031.04: patient care. Federal Bureau of Prisons, US Department of Justice. June 3, 2014. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.bop.gov/policy/progstat/6031_004.pdf

- 16.DeMartino ES, Dudzinski DM, Doyle CK, et al. Who decides when a patient can’t? statutes on alternate decision makers. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(15):1478-1482. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1611497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helmly V, Garica M, Williams B, Howell BA. A review and content analysis of U.S. Department of Corrections end-of-life decision making policies. Int J Prison Health. Published online December 27, 2021. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-06-2021-0060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Medical Association . Chapter 2: opinions on consent, communication, and decision-making. AMA Code of Medical Ethics. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://code-medical-ethics.ama-assn.org/chapters/consent-communication-decision-making

- 19.Glenn JE, Bennett AM, Hester RJ, Tajuddin NN, Hashmi A. “It’s like heaven over there”: medicine as discipline and the production of the carceral body. Health Justice. 2020;8(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s40352-020-00107-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Min I, Schonberg D, Anderson M. A review of primary care training programs in correctional health for physicians. Teach Learn Med. 2012;24(1):81-89. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2012.641492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Posner MJ. The Estelle medical professional judgment standard: the right of those in state custody to receive high-cost medical treatments. Am J Law Med. 1992;18(4):347-368. doi: 10.1017/S0098858800007334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wakeman SE, Rich JD. Fulfilling the mission of academic medicine: training residents in the health needs of prisoners. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(suppl 2):S186-S188. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1258-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bednar AL. HIPAA’s impact on prisoners’ rights to healthcare. January 28, 2003. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.law.uh.edu/healthlaw/perspectives/privacy/030128hipaas.pdf

- 24.Brooks KC, Makam AN, Haber LA. Caring for hospitalized incarcerated patients: physician and nurse experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(2):485-487. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06510-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clarke JG, Adashi EY. Perinatal care for incarcerated patients: a 25-year-old woman pregnant in jail. JAMA. 2011;305(9):923-929. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Douglas AD, Zaidi MY, Maatman TK, Choi JN, Meagher AD. Caring for incarcerated patients: can it ever be equal? J Surg Educ. 2021;78(6):e154-e160. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuller L, Eves MM. Incarcerated patients and equitability: the ethical obligation to treat them differently. J Clin Ethics. 2017;28(4):308-313. doi: 10.1086/JCE2017284308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tuite H, Browne K, O’Neill D. Prisoners in general hospitals: doctors’ attitudes and practice. BMJ. 2006;332(7540):548-549. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7540.548-b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zust BL, Busiahn L, Janisch K. Nurses’ experiences caring for incarcerated patients in a perinatal unit. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2013;34(1):25-29. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.715234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Admission Characteristics

Data Sharing Statement