Abstract

Chemoproteomic profiling is a powerful approach to define the selectivity of small molecules and endogenous metabolites with the human proteome. In addition to mechanistic studies, proteome specificity profiling also has the potential to identify new scaffolds for biomolecular sensing. Here, we report a chemoproteomics-inspired strategy for selective sensing of acetyl-CoA. First, we use chemoproteomic capture experiments to validate the N-terminal acetyltransferase NAA50 as a protein capable of differentiating acetyl-CoA and CoA. A Nanoluc-NAA50 fusion protein retains this specificity and can be used to generate a bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) signal in the presence of a CoA-linked fluorophore. This enables the development of a ligand displacement assay in which CoA metabolites are detected via their ability to bind the Nanoluc-NAA50 protein “host” and compete binding of the CoA-linked fluorophore “guest”. We demonstrate that the specificity of ligand displacement reflects the molecular recognition of the NAA50 host, while the window of dynamic sensing can be controlled by tuning the binding affinity of the CoA-linked fluorophore guest. Finally, we show that the method’s specificity for acetyl-CoA can be harnessed for gain-of-signal optical detection of enzyme activity and quantification of acetyl-CoA from cellular samples. Overall, our studies demonstrate the potential of harnessing insights from chemoproteomics for molecular sensing and provide a foundation for future applications in target engagement and selective metabolite detection.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Acetyl-CoA is essential for life and plays a key role in energy production and lipid metabolism.1 Overactivation of two enzymes responsible for human acetyl-CoA metabolism, ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY) and acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 (ACSS2), is associated with several cancers2,3 and has been the target of substantial therapeutic development efforts.4,5 Acetyl-CoA also plays an important role in epigenetic signaling, protein homeostasis, and protein synthesis due to its ability to serve as a cofactor used in the modifications of proteins6 and RNA.7 Over the last decade, substantial evidence indicates that these processes can be regulated by subcellular acetyl-CoA levels,8-10 highlighting the potential for acetyl-CoA to directly link metabolism and gene expression. Emphasizing this, a recent study demonstrated that concentrations of acetyl-CoA in the nucleus are distinct from those in other organelles.11 These experiments relied on careful cellular fractionation in combination with liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS). This approach holds the advantage of being able to differentiate multiple acyl-CoA metabolites but requires specialized equipment and has a limited capacity for measuring dynamics.

Optical sensing represents an alternative approach to study CoA metabolites.12 Three general classes of CoA sensors have been reported, which detect malonyl-CoA,13,14 long-chain fatty acyl (LCFA)-CoAs,15 and nonthioesterified CoA.16 Absent from this emerging arsenal are methods to detect acetyl-CoA. The selective molecular recognition of acetyl-CoA versus CoA presents a challenge to sensor design due to the necessity to differentiate two large (>750 Da) metabolites based on replacement of a single hydrogen atom with an acetyl group that comprises only ~5% of total mass (Figure 1a). Prior efforts at selective molecular recognition of acetyl-CoA have either failed17 or been limited to disruption rather than augmentation of acetyl-CoA binding.16

Figure 1.

(a) Structures of acetyl-CoA and CoA. (b) Schematic of the competitive chemoproteomic profiling experiment. (c) Dose-dependent competition of NAA50 capture in chemoproteomic experiments. Label-free abundance measurements were based on dNSAF, n = 3 technical replicates. (d,e) Chemoproteomic capture of NAA50 by Ahx-CoA resins is competed by acetyl-CoA and CoA. Data is representative of two independent replicates. For additional validation blotting data, see Figure S3.

A prerequisite for acetyl-CoA sensing is the identification of specific binding scaffolds that can be leveraged for optical detection. Setting this as our goal, we took inspiration from metabolic mechanisms of epigenetic regulation.18,19 Specifically, histone acetylation has been proposed to be regulated by high acetyl-CoA levels, which liberate histone acetyltransferase (HAT) enzymes from metabolic feedback inhibition by CoA.20,21 To understand this mechanism’s selectivity, our group has used chemoproteomic profiling to define how proteins bind to acetyl-CoA and CoA on a proteome-wide scale.22 In addition to identifying new acetyltransferases that are highly sensitive to feedback inhibition, these studies also detect enzymes that preferentially bind acetyl-CoA (Figure 1b). Here, we describe a unique example of how chemoproteomic profiling data can be directly leveraged for biomolecular sensor design by enabling the development and application of a selective bioluminescent reporter of acetyl-CoA.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemoproteomics Identifies NAA50 as a Selective Acetyl-CoA Binding Scaffold.

To assess whether the chemoproteomics data approach could be leveraged for selective sensing, we analyzed a previous chemoproteomic dataset, which determined how capture of proteins by a CoA-based affinity resin was competed by acetyl-CoA or CoA,10 fitting quantitative abundance data to a nonlinear regression model. Since CoA affinity resins can capture both direct and indirect interactors,23 we focused on 23 proteins known to directly bind to acetyl-CoA, 13 of which displayed dose-dependent competition (R2 ≥ 0.85) by both metabolites (Figure S1 and Tables S1 and S2). Comparing half-maximal inhibition (IC50) values, we identified three N-terminal acetyltransferases (NAA30, NAA40, and NAA50) that display ≥5-fold preferential competition by acetyl-CoA (Table S2 and Figure 1c). These proteins harbor highly homologous acetyl-CoA binding sites (Figure S2).24 We prioritized validation of the recognition properties of NAA50 as it yielded the strongest chemoproteomic signal (Table S2), has been well-studied from the perspective of inhibitor binding,25,26 and interacts with two partner proteins (NAA15 and HYPK) that were also selectively competed by acetyl-CoA (Table S2). Nondenatured whole cell lysates were incubated with CoA affinity resins, washed to remove nonspecific interactors, and blotted for NAA50.

Consistent with high-throughput measurements, acetyl-CoA competed capture of NAA50 at lower concentrations than CoA (Figure 1d,e and Figure S3). Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis further confirmed ~10-fold preferential binding of acetyl-CoA to NAA50 (Table S3).26 Overall, these studies highlight the ability of chemoproteomics to characterize differential metabolite binding and specify NAA50 as a selective receptor for acetyl-CoA.

Nanoluc-NAA50 and Cy3-CoA Exhibit Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer.

Next, we sought to exploit NAA50’s molecular recognition properties for acetyl-CoA sensing. Previous CoA biosensors have used ratiometric fluorescence15 and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) detection.16 Considering the relatively narrow sensing window of NAA50 and unknown conformational effects of acetyl-CoA binding, we wondered whether bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET), a method that can display increased detection sensitivity relative to FRET, may provide a complementary approach (Figure 2a).27 To construct a BRET reporter for acetyl-CoA, we fused NAA50 to the C-terminus of an engineered luciferase (Nanoluc/Nluc) that has shown broad utility as a BRET donor.28 The predicted structure of the fusion protein29 indicated a distance of ~6 nm between the Nanoluc and NAA50 active sites, well within the 10 nm range recommended for BRET (Figure 2b).27 Two CoA analogues were synthesized to serve as BRET acceptors: Cy3-Ahx-CoA (1) and Cy3-Ahx-D-CoA (2; Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

(a) Competitive BRET assay. (b) Domain architecture and predicted structure of Nanoluc-NAA50. The CoA analogue is positioned based on a prior structure of NAA50 structure complexed to a bisubstrate inhibitor (PDB: 6wf3). (c) Structures of Cyanine-CoA BRET acceptors 1 and 2 used in this study.

Prior studies have found both 1 and 2 capture NAA50 from cell extracts when immobilized on resin; however, enrichment by Ahx-D-CoA (2) is more efficient than 1 due to its higher affinity.30 This is useful as high and low affinity BRET acceptor ligands may enable our sensing window to be shifted into different concentration regimes (e.g., micromolar versus nanomolar), increasing the utility of our approach.

To establish this method, Nanoluc-NAA50 was recombinantly expressed and purified (Figure S4). CoA analogues were synthesized via a previously reported method (Scheme S1).30 Chemoproteomic capture confirmed preferential binding of acetyl-CoA to the fusion protein (Figure S5). To assess this system’s capabilities as a BRET reporter (Figure 3a), purified Nanoluc-NAA50 (Figure 3b) was incubated with the Nanoluc substrate furimazine in the presence of increasing Cy3-Ahx-CoA (1). Evaluation of BRET by comparing the ratio of Cy3 (λem = 590 nm) to furimazine (λem = 460 nm) emission (Figure 3c) revealed a dose-dependent increase in signal, with a maximum change of ~ 15-fold observed in the presence of 100 nM 1 (Figure 3d). BRET signal intensity decreased slightly after 30 min (Figure S6), as expected due to consumption of the furimazine substrate. These studies establish the capability of Cy3-CoA 1 to serve as a BRET acceptor for Nanoluc-NAA50.

Figure 3.

(a) BRET assay schematic. (b) SDS-PAGE of purified Nanoluc-NAA50. (c) Emission spectra of Nanoluc-NAA50 treated with furimazine in the presence of increasing 1. Data is the average of n = 3 technical replicates. (d) BRET emission ratio of Nanoluc-NAA50 treated with furimazine in the presence of increasing concentrations of 1. Data represents the average of n = 3 technical replicates.

BRET Is Acetyl-CoA-Dependent and Can Be Tuned by Acceptor Ligand Affinity.

Next, we defined the properties and tunability of this system as a ligand displacement assay for acetyl-CoA. Nanoluc-NAA50 was preincubated with increasing concentrations of CoA metabolites, followed by addition of Cy3-Ahx-CoA (1) and furimazine. Consistent with chemoproteomic data, BRET analysis indicated differential competition of NAA50 occupancy by acetyl-CoA (IC50 = 61 nM) and CoA (IC50 = 680 nM; Figure 4a). To extend our BRET sensing method into higher concentration regimes, we tested metabolite competition in the presence of 2, a CoA ligand with a higher affinity for NAA50.30

Figure 4.

BRET-based detection of CoA metabolites. (a) Competition of 1 by acetyl-CoA (orange) and CoA (gray). n = 3 technical replicates. (b) Competition of 2 by acetyl-CoA and CoA. n = 3 technical replicates. (c) Structures of CoA metabolites. (d) Competition of Nanoluc-Naa50-1 BRET signal by structurally diverse CoA metabolites at 1 μM. n = 3 technical replicates. n.s. = not significantly different (Student’s t test, two-tailed). (e) Comparison of measurements of acetyl-CoA present in extracted cellular metabolomes made by LC–MS (gray) and BRET (orange). * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.005 n.s. = not significantly different (Student’s t-test, two-tailed). Data is reported in pmol of acetyl-CoA per extract and represents the average of n = 3 biological replicates. (f) Linear correlation between measurements of acetyl-CoA made by LC–MS (x axis) and BRET (y axis). R2 = correlation coefficient of linear regression.

As anticipated, competition of the tighter-binding CoA BRET acceptor requires higher concentrations of acetyl-CoA (IC50 = 620 nM) and CoA (IC50 = 7300 nM; Figure 4b). However, the selectivity for these metabolites remains unchanged. The ability to tune concentration window using structural analogues of the BRET acceptor offers a unique alternative to mutational optimization, and suggests the possibility of extending this method across the range of acetyl-CoA concentrations that occur in cells.1,11

Acetyl-CoA Selectivity In Vitro and in Extracted Cellular Metabolite Pools.

Assessing the selectivity of our assay (using Cy3-Ahx-CoA 1) across a wider range of CoAs revealed that only the short chain fatty acid (SCFA) metabolites acetyl- and propionyl-CoA significantly competed BRET signal at 1 μM (Figure 4c,d). Although cellular concentrations of acetyl-CoA are typically far higher than propionyl-CoA, this result suggests that other SCFA-CoAs could significantly interact with our sensor, particularly in specialized conditions where they accumulate.31,32 To better understand the Nanoluc-NAA50 sensor’s ability to measure acetyl-CoA amid a physiological range of structurally related metabolites, we isolated metabolomes from two cell lines (LN229 and HepG2) and compared BRET competition to LC–MS measurements of acetyl-CoA.33,34 Metabolite extracts or vehicle buffer was added to the BRET sensor reaction (Nanoluc-NAA50, 1 and furimazine), and the observed loss of signal was fit to a standard curve generated by acetyl-CoA competition (Figure 4a). LC–MS analyses have found these metabolomes can harbor 2–3-fold greater CoA (interferant) than acetyl-CoA (analyte).35 However, comparative measurements of acetyl-CoA made by LC–MS and BRET signal competition were not significantly different (Figure 4e,f). To more definitively attribute the competition signal to acetyl-CoA, we incubated cells with acetate, which fuels acetyl-CoA production via the activity of ACSS2.3,4 LC–MS analysis revealed that acetate treatment led to a significant increase in acetyl-CoA levels in LN229 but not HepG2 metabolite extracts as assessed by LC–MS. Acetate-treated LN229 metabolomes also displayed significantly increased concentrations of acetyl-CoA as calculated by the BRET ligand displacement assay (Figure 4e). Again, absolute levels of acetyl-CoA quantified by LC–MS and BRET were within error. This is consistent with the ability of the Nanoluc-NAA50 scaffold to accurately quantify changes in acetyl-CoA against physiological metabolite backgrounds. These findings establish a ligand-tunable bioluminescent indicator displacement assay capable of mass spectrometry-free detection of acetyl-CoA from cellular samples.

Real-Time Optical Detection of Enzymatic Acetyl-CoA Turnover.

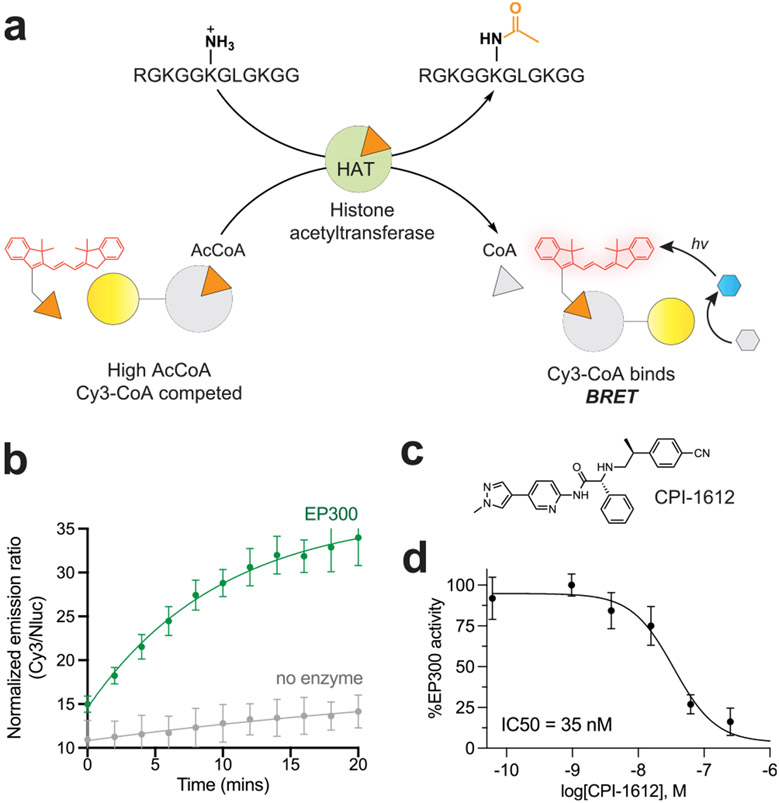

Prior work has demonstrated that BRET metabolite sensors can be coupled to a wide range of enzyme assays to facilitate research and clinical diagnostics,36-38 a capability that could be extended by a method for detecting acetyl-CoA. To assess whether the selectivity window afforded by NAA50 could accommodate such an application, we first tested the ability of our BRET ligand displacement assay to monitor acetyltransferase activity (Figure 5a). For these assays, we incubated the histone acetyltransferase EP300 (75 nM) with the acetyl-CoA (1 μM) histone peptide substrate (50 μM) and all components necessary for the BRET detection of acetyl-CoA (Nanoluc-NAA50, furimazine, and 1). Our expectation was that high concentrations of acetyl-CoA present at the start of the assay would compete with 1 for binding to the Nanoluc-Naa50 donor, inhibiting BRET (Figure 5a, left). Transfer of acetyl-CoA to the histone peptide by EP300 relieves this competition, enabling 1 to bind and produce a BRET signal (Figure 5a, right). Pilot studies to establish practicality indicated acetyl-CoA competes Nanoluc-NAA50/1 BRET in the presence of micromolar CoA (Figure S7a). As anticipated, performing the EP300 enzyme reaction in the presence of ligand displacement assay components resulted in time-dependent BRET signal production (Figure 5b). To assess the assay ability to report on changes in enzyme activity, we incubated EP300 with CPI-1612, a high-affinity small molecule inhibitor of the enzyme.39 Analyzing a fixed time point in the enzymatic reaction linear phase,40 we observed CPI-1612 to cause a dose-dependent decrease in BRET signal (IC50 = 35 nM, Figure 5d). Control experiments confirmed that CPI-1612 did not interfere with the BRET assay itself (Figure S8). This method was further extended to monitor the enzymatic activity and small molecule inhibition of KAT6A, another histone acetyltransferase drug target (Figure S9).41,42 Consumption of acetyl-CoA has been previously monitored as a surrogate for acetyltransferase activity using fluorogenic reactions43 or LC–MS.44 The BRET method uniquely complements these methods by enabling a real-time rather than endpoint readout. An important caveat is that the demonstrated BRET assay does not use cell extracts, as would be required for a point-of-care assay,36,45 and thus is most appropriate for research applications. However, we did demonstrate that ectopically overexpressed Nanoluc can differentiate acetyl-CoA and CoA in cell lysates (Figure S7b), supporting the feasibility of detecting enzymatic acetyl-CoA consumption in more complex settings. Overall, our studies illustrate how selective molecular recognition of acetyl-CoA can be coupled to enzyme activity to develop biochemical assays with novel capabilities.

Figure 5.

(a) Overall assay schematic. (b) Time-dependent activity of EP300 histone acetyltransferase. (c) Structure of CPI-1612. (d) Dose-dependent inhibition of EP300 by CPI-1612. Activity was calculated from single time-point measurements made when the EP300 reaction was in its linear phase (t = 5 min). Data represents the average of n = 5 technical replicates.

CONCLUSIONS

Specific detection of acetyl-CoA presents a challenge to sensor design due to a lack of scaffolds capable of its selective molecular recognition. As a first step to address this challenge, here, we describe the chemoproteomics-driven discovery of a selective molecular host for acetyl-CoA. Our approach harnesses the observation that capture of NAA50 by chemoproteomic affinity resins is competed more efficiently by acetyl-CoA than CoA.10,23 This enabled the development of a BRET-based indicator displacement assay that can differentiate acetyl-CoA and CoA, whose absolute concentration range can be tuned via structural editing of the Cy3-CoA acceptor ligand and which can be applied for quantification of acetyl-CoA from biological samples and real-time assays of histone acetyltransferase activity and inhibition. Chemoproteomic methods to probe metabolite binding sites are increasingly used to analyze drug target engagement and enable biological discovery. Our study highlights an additional powerful application of chemoproteomics: the ability to identify natural molecular recognition scaffolds that can be harnessed for biomolecular sensing, providing a methodological bridge between target engagement and imaging.

It is also important to describe limitations of our study and future avenues by which they may be addressed. While we achieved our goal of identifying and validating the first protein scaffold capable of direct bioluminescent detection of acetyl-CoA, additional development will be necessary for imaging and diagnostic applications. Focusing on selectivity, specific imaging of CoA has been achieved using protein scaffolds that bind CoA ~20-fold preferentially relative to acetyl-CoA.16 An equal or greater preference may aid imaging of acetyl-CoA. To extend the window with which acetyl-CoA can be differentiated from CoA (currently ~10-fold for Nanoluc-NAA50), we envision two approaches. First, almost all characterized acetyltransferases interact with acetyl-CoA via a binding cleft formed between the β4 and β5 strands that includes a β-bulge in β4, which orients backbone amides toward the carbonyl thioester of acetyl-CoA (Figure S10).24 Prior studies have found mutations in β4 and β5, and the adjacent loops can alter acyl-CoA/acetyltransferase interactions,46-48 providing a starting point for rational mutagenesis or directed evolution. Second, further application of chemoproteomic strategies will likely yield additional scaffolds of distinct selectivity. As one example, in the dataset analyzed here,10 the CoA biosynthetic enzyme PANK3 was specifically competed by acetyl-CoA versus CoA at 3 μM but was not prioritized due to the poor fit (R2 ≤ 0.85) of its dose–response profile (Figure S11a,b). Extending our design and analysis workflow to this “weak hit”, we generated an N-terminal maltose-binding protein (MBP)-PANK3-Nanoluc fusion that displays an ~4-fold increase in BRET ratio upon incubation with 1 (10 μM) and furimazine (Figure S11c-f). This BRET signal is significantly less effective than that produced by Nanoluc-NAA50 (~15–20-fold, Figure 3d) and requires 10-fold higher concentrations of 1; however, competition of MBP-PANK3-Nanoluc BRET was highly selective (~100-fold) for acetyl-CoA versus CoA (Figure S11g). While we defer further characterization of the PANK3 scaffold to future work, these studies demonstrate the potential for acetyl-CoA sensor selectivity to be improved and the ability of chemoproteomics to facilitate this goal.

In addition to better selectivity, avoiding perturbation of endogenous biology during cellular application will benefit from identification of mutations that inactivate catalytic activity without altering acetyl-CoA binding. In the case of NAA50 and PANK3, crystal structures should help specify candidate inactivating residues in their N-terminal peptide and ATP binding sites, respectively.26,49 Finally, exploiting these protein scaffolds for cellular acetyl-CoA imaging will require coupling them to fluorescence detection, for example, via insertion of circular-permutated fluorescent proteins into regions whose conformation is altered by acetyl-CoA binding 5 or employment of the Snifit (SNAP-tag-based indicator with a fluorescent intramolecular tether) concept.16 In the case of the sensor described here, Nanoluc could be replaced with a fluorescent protein and a SNAP-tag fusion used to couple a dye-labeled CoA analogue or small molecule inhibitor26 directly to the acetyl-CoA-binding protein (Figure S12). Our results indicate that the structure of the CoA guest can change its binding affinity with NAA50 (Figure 4a,b), a property that could be useful for tuning the sensing window of a Snifit to the distinct concentrations of acetyl-CoA found in different organelles. Overall, our studies demonstrate how insights from chemoproteomics can address challenges in molecular recognition and provide an analysis workflow and proof-of-concept binding scaffold for target engagement and selective metabolite detection applications.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Martin Schnermann (NCI) for helpful discussions, Dr. Euna Yoo (NCI) for access to instrumentation, and Lauren Beaumont (Leidos Inc.) for experimental protocols. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Kryzsztof Krajewski of the UNC High-Throughput Peptide Synthesis Core facility for peptide synthesis. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research ZIA BC011488 (J.L.M.) and NIH R01GM132261 and T32GM142606 (N.W.S.). In addition, this project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract number HHSN261200800001E.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.3c05489.

Detailed experimental procedures, Figures S1–S12, Tables S1–S3, and Scheme S1 (PDF)

Extended Table S1 giving numerical values for >1000 proteins captured by CoA affinity resin (XLSX)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Whitney K. Lieberman, Chemical Biology Laboratory, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Frederick, Maryland 21702, United States.

Zachary A. Brown, Chemical Biology Laboratory, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Frederick, Maryland 21702, United States.

Daniel S. Kantner, Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, Center for Metabolic Disease Research, Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19140, United States

Yihang Jing, Chemical Biology Laboratory, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Frederick, Maryland 21702, United States.

Emily Megill, Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, Center for Metabolic Disease Research, Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19140, United States.

Nya D. Evans, Chemical Biology Laboratory, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Frederick, Maryland 21702, United States

McKenna C. Crawford, Chemical Biology Laboratory, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Frederick, Maryland 21702, United States

Isita Jhulki, Chemical Biology Laboratory, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Frederick, Maryland 21702, United States.

Carissa Grose, Protein Expression Laboratory, Cancer Research Technology Program, Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc., Frederick, Maryland 21702, United States.

Jane E. Jones, Protein Expression Laboratory, Cancer Research Technology Program, Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc., Frederick, Maryland 21702, United States

Nathaniel W. Snyder, Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, Center for Metabolic Disease Research, Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19140, United States

Jordan L. Meier, Chemical Biology Laboratory, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Frederick, Maryland 21702, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Trefely S; Lovell CD; Snyder NW; Wellen KE Compartmentalised acyl-CoA metabolism and roles in chromatin regulation. Mol. Metab 2020, 38, No. 100941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Hatzivassiliou G; Zhao F; Bauer DE; Andreadis C; Shaw AN; Dhanak D; Hingorani SR; Tuveson DA; Thompson CB ATP citrate lyase inhibition can suppress tumor cell growth. Cancer Cell 2005, 8, 311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Comerford SA; Huang Z; Du X; Wang Y; Cai L; Witkiewicz AK; Walters H; Tantawy MN; Fu A; Manning H. c.; Horton JD; Hammer RE; McKnight SL; Tu BP Acetate dependence of tumors. Cell 2014, 159, 1591–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Miller KD; Pniewski K; Perry CE; Papp SB; Shaffer JD; Velasco-Silva JN; Casciano JC; Aramburu TM; Srikanth YVV; Cassel J; Skordalakes E; Kossenkov AV; Salvino JM; Schug ZT Targeting ACSS2 with a Transition-State Mimetic Inhibits Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Growth. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 1252–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Wei J; Leit S; Kuai J; Therrien E; Rafi S; Harwood HJ Jr.; DeLaBarre B; Tong L An allosteric mechanism for potent inhibition of human ATP-citrate lyase. Nature 2019, 568, 566–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Verdin E; Ott M 50 years of protein acetylation: from gene regulation to epigenetics, metabolism and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2015, 16, 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Sas-Chen A; Thomas JM; Matzov D; Taoka M; Nance KD; Nir R; Bryson KM; Shachar R; Liman GLS; Burkhart BW; Gamage ST; Nobe Y; Briney CA; Levy MJ; Fuchs RT; Robb GB; Hartmann J; Sharma S; Lin Q; Florens L; Washburn MP; Isobe T; Santangelo TJ; Shalev-Benami M; Meier JL; Schwartz S Dynamic RNA acetylation revealed by quantitative cross-evolutionary mapping. Nature 2020, 583, 638–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Wellen KE; Hatzivassiliou G; Sachdeva UM; Bui TV; Cross JR; Thompson CB ATP-citrate lyase links cellular metabolism to histone acetylation. Science 2009, 324, 1076–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Yi CH; Pan H; Seebacher J; Jang IH; Hyberts SG; Heffron GJ; Vander Heiden MG; Yang R; Li F; Locasale JW; Sharfi H; Zhai B; Rodriguez-Mias R; Luithardt H; Cantley LC; Daley GQ; Asara JM; Gygi SP; Wagner G; Liu CF; Yuan J Metabolic regulation of protein N-alpha-acetylation by Bcl-xL promotes cell survival. Cell 2011, 146, 607–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Levy MJ; Montgomery DC; Sardiu ME; Montano JL; Bergholtz SE; Nance KD; Thorpe AL; Fox SD; Lin Q; Andresson T; Florens L; Washburn MP; Meier JL A Systems Chemoproteomic Analysis of Acyl-CoA/Protein Interaction Networks. Cell Chem. Biol 2020, 27, 322–333.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Trefely S; Huber K; Liu J; Noji M; Stransky S; Singh J; Doan MT; Lovell CD; von Krusenstiern E; Jiang H; Bostwick A; Pepper HL; Izzo L; Zhao S; Xu JP; Bedi KC Jr.; Rame JE; Bogner-Strauss JG; Mesaros C; Sidoli S; Wellen KE; Snyder NW Quantitative subcellular acyl-CoA analysis reveals distinct nuclear metabolism and isoleucine-dependent histone propionylation. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 447–462.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Greenwald EC; Mehta S; Zhang J Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Biosensors Illuminate the Spatiotemporal Regulation of Signaling Networks. Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 11707–11794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Ellis JM; Wolfgang MJ A genetically encoded metabolite sensor for malonyl-CoA. Chem. Biol 2012, 19, 1333–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Du Y; Hu H; Pei X; Du K; Wei T Genetically Encoded FapR-NLuc as a Biosensor to Determine Malonyl-CoA in Situ at Subcellular Scales. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30, 826–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Wang W; Wei Q; Zhang J; Zhang M; Wang C; Qu R; Wang Y; Yang G; Wang J A Ratiometric Fluorescent Biosensor Reveals Dynamic Regulation of Long-Chain Fatty Acyl-CoA Esters Metabolism. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 2021, 60, 13996–14004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Xue L; Schnacke P; Frei MS; Koch B; Hiblot J; Wombacher R; Fabritz S; Johnsson K Probing coenzyme A homeostasis with semisynthetic biosensors. Nat. Chem. Biol 2023, 19, 346–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Saran D; Frank J; Burke DH The tyranny of adenosine recognition among RNA aptamers to coenzyme A. BMC Evol. Biol 2003, 3, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Meier JL Metabolic mechanisms of epigenetic regulation. ACS Chem. Biol 2013, 8, 2607–2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kinnaird A; Zhao S; Wellen KE; Michelakis ED Metabolic control of epigenetics in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 694–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Zhao S; Torres A; Henry RA; Trefely S; Wallace M; Lee JV; Carrer A; Sengupta A; Campbell SL; Kuo YM; Frey AJ; Meurs N; Viola JM; Blair IA; Weljie AM; Metallo CM; Snyder NW; Andrews AJ; Wellen KE ATP-Citrate Lyase Controls a Glucose-to-Acetate Metabolic Switch. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 1037–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Savir Y; Tu BP; Springer M Competitive inhibition can linearize dose-response and generate a linear rectifier. Cell Syst. 2015, 1, 238–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Kulkarni RA; Montgomery DC; Meier JL Epigenetic regulation by endogenous metabolite pharmacology. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2019, 51, 30–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Montgomery DC; Garlick JM; Kulkarni RA; Kennedy S; Allali-Hassani A; Kuo YM; Andrews AJ; Wu H; Vedadi M; Meier JL Global Profiling of Acetyltransferase Feedback Regulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 6388–6391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Vetting MW; de Carvalho LP; Yu M; Hegde SS; Magnet S; Roderick SL; Blanchard JS Structure and functions of the GNAT superfamily of acetyltransferases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 2005, 433, 212–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Foyn H; Jones JE; Lewallen D; Narawane R; Varhaug JE; Thompson PR; Arnesen T Design, synthesis, and kinetic characterization of protein N-terminal acetyltransferase inhibitors. ACS Chem. Biol 2013, 8, 1121–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Kung PP; Bingham P; Burke BJ; Chen Q; Cheng X; Deng YL; Dou D; Feng J; Gallego GM; Gehring MR; Grant SK; Greasley S; Harris AR; Maegley KA; Meier J; Meng X; Montano JL; Morgan BA; Naughton BS; Palde PB; Paul TA; Richardson P; Sakata S; Shaginian A; Sonnenburg WK; Subramanyam C; Timofeevski S; Wan J; Yan W; Stewart AE Characterization of Specific N-α-Acetyltransferase 50 (Naa50) Inhibitors Identified Using a DNA Encoded Library. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2020, 11, 1175–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Pfleger KD; Seeber RM; Eidne KA Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) for the real-time detection of protein-protein interactions. Nat. Protoc 2006, 1, 337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Hall MP; Unch J; Binkowski BF; Valley MP; Butler BL; Wood MG; Otto P; Zimmerman K; Vidugiris G; Machleidt T; Robers MB; Benink HA; Eggers CT; Slater MR; Meisenheimer PL; Klaubert DH; Fan F; Encell LP; Wood KV Engineered luciferase reporter from a deep sea shrimp utilizing a novel imidazopyrazinone substrate. ACS Chem. Biol 2012, 7, 1848–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Jumper J; Evans R; Pritzel A; Green T; Figurnov M; Ronneberger O; Tunyasuvunakool K; Bates R; Zidek A; Potapenko A; Bridgland A; Meyer C; Kohl SAA; Ballard AJ; Cowie A; Romera-Paredes B; Nikolov S; Jain R; Adler J; Back T; Petersen S; Reiman D; Clancy E; Zielinski M; Steinegger M; Pacholska M; Berghammer T; Bodenstein S; Silver D; Vinyals O; Senior AW; Kavukcuoglu K; Kohli P; Hassabis D Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Jing Y; Montano JL; Levy M; Lopez JE; Kung PP; Richardson P; Krajewski K; Florens L; Washburn MP; Meier JL Harnessing Ionic Selectivity in Acetyltransferase Chemoproteomic Probes. ACS Chem. Biol 2021, 16, 27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Manoli I; Pass AR; Harrington EA; Sloan JL; Gagné J; McCoy S; Bell SL; Hattenbach JD; Leitner BP; Duckworth CJ; Fletcher LA; Cassimatis TM; Galarreta CI; Thurm A; Snow J; Van Ryzin C; Ferry S; Mew NA; Shchelochkov OA; Chen KY; Venditti CP 1-(13)C-propionate breath testing as a surrogate endpoint to assess efficacy of liver-directed therapies in methylmalonic acidemia (MMA). Genet. Med 2021, 23, 1522–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Tirosh A; Calay ES; Tuncman G; Claiborn KC; Inouye KE; Eguchi K; Alcala M; Rathaus M; Hollander KS; Ron I; Livne R; Heianza Y; Qi L; Shai I; Garg R; Hotamisligil GS The short-chain fatty acid propionate increases glucagon and FABP4 production, impairing insulin action in mice and humans. Sci. Transl. Med 2019, 11, No. eaav0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Frey AJ; Feldman DR; Trefely S; Worth AJ; Basu SS; Snyder NW LC-quadrupole/Orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometry enables stable isotope-resolved simultaneous quantification and 13C-isotopic labeling of acyl-coenzyme A thioesters. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2016, 408, 3651–3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Snyder NW; Tombline G; Worth AJ; Parry RC; Silvers JA; Gillespie KP; Basu SS; Millen J; Goldfarb DS; Blair IA Production of stable isotope-labeled acyl-coenzyme A thioesters by yeast stable isotope labeling by essential nutrients in cell culture. Anal. Biochem 2015, 474, 59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Lee JV; Carrer A; Shah S; Snyder NW; Wei S; Venneti S; Worth AJ; Yuan ZF; Lim HW; Liu S; Jackson E; Aiello NM; Haas NB; Rebbeck TR; Judkins A; Won KJ; Chodosh LA; Garcia BA; Stanger BZ; Feldman MD; Blair IA; Wellen KE Akt-dependent metabolic reprogramming regulates tumor cell histone acetylation. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 306–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Yu Q; Xue L; Hiblot J; Griss R; Fabritz S; Roux C; Binz PA; Haas D; Okun JG; Johnsson K Semisynthetic sensor proteins enable metabolic assays at the point of care. Science 2018, 361, 1122–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Yu Q; Pourmandi N; Xue L; Gondrand C; Fabritz S; Bardy D; Patiny L; Katsyuba E; Auwerx J; Johnsson K A biosensor for measuring NAD(+) levels at the point of care. Nat. Metab 2019, 1, 1219–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Cambronne XA; Stewart ML; Kim D; Jones-Brunette AM; Morgan RK; Farrens DL; Cohen MS; Goodman RH Biosensor reveals multiple sources for mitochondrial NAD(+). Science 2016, 352, 1474–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Wilson JE; Patel G; Patel C; Brucelle F; Huhn A; Gardberg AS; Poy F; Cantone N; Bommi-Reddy A; Sims RJ III; Cummings RT; Levell JR Discovery of CPI-1612: A Potent, Selective, and Orally Bioavailable EP300/CBP Histone Acetyltransferase Inhibitor. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2020, 11, 1324–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Tonge PJ Quantifying the Interactions between Biomolecules: Guidelines for Assay Design and Data Analysis. ACS Infect. Dis 2019, 5, 796–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Baell JB; Leaver DJ; Hermans SJ; Kelly GL; Brennan MS; Downer NL; Nguyen N; Wichmann J; McRae HM; Yang Y; Cleary B; Lagiakos HR; Mieruszynski S; Pacini G; Vanyai HK; Bergamasco MI; May RE; Davey BK; Morgan KJ; Sealey AJ; Wang B; Zamudio N; Wilcox S; Garnham AL; Sheikh BN; Aubrey BJ; Doggett K; Chung MC; de Silva M; Bentley J; Pilling P; Hattarki M; Dolezal O; Dennis ML; Falk H; Ren B; Charman SA; White KL; Rautela J; Newbold A; Hawkins ED; Johnstone RW; Huntington ND; Peat TS; Heath JK; Strasser A; Parker MW; Smyth GK; Street IP; Monahan BJ; Voss AK; Thomas T Inhibitors of histone acetyltransferases KAT6A/B induce senescence and arrest tumour growth. Nature 2018, 560, 253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Sharma S; Chung J; Uryu S; Rickard A; Nady N; Khan S; Wang ZX; Zhang Y; Zhang HK; Kung PP; Greenwald E; Maegley K; Bingham P; Lam H; Bozikis YE; Falk H; Allan E; Avery VM; Butler MS; Camerino MA; Carrasco-Pozo C; Charman SA; Davis MJ; Dawson MA; Sarah-Jane D; de Silva M; Dennis ML; Dolezal O; Lagiakos R; Lindeman GJ; MacPherson L; Nuttall S; Peat TS; Ren B; Stupple AE; Surgenor E; Tan CW; Thomas T; Visvader JE; Voss AK; Vaillant F; White KL; Whittle J; Yang YQ; Hediyeh-Zadeh S; Stupple PA; Street IP; Monahan BJ; Paul T First-in-class KAT6A/KAT6B inhibitor CTx-648 (PF-9363) demonstrates potent anti-tumor activity in ER plus breast cancer with KAT6A dysregulation. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 1130. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Bulfer SL; McQuade TJ; Larsen MJ; Trievel RC Application of a high-throughput fluorescent acetyltransferase assay to identify inhibitors of homocitrate synthase. Anal. Biochem 2011, 410, 133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Rye PT; Frick LE; Ozbal CC; Lamarr WA Advances in Label-Free Screening Approaches for Studying Histone Acetyltransferases. J. Biomol. Screening 2011, 16, 1186–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Griss R; Schena A; Reymond L; Patiny L; Werner D; Tinberg CE; Baker D; Johnsson K Bioluminescent sensor proteins for point-of-care therapeutic drug monitoring. Nat. Chem. Biol 2014, 10, 598–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Kaczmarska Z; Ortega E; Goudarzi A; Huang H; Kim S; Márquez JA; Zhao Y; Khochbin S; Panne D Structure of p300 in complex with acyl-CoA variants. Nat. Chem. Biol 2017, 13, 21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Yang C; Mi J; Feng Y; Ngo L; Gao T; Yan L; Zheng YG Labeling lysine acetyltransferase substrates with engineered enzymes and functionalized cofactor surrogates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 7791–7794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Wang Y; Guo YR; Liu K; Yin Z; Liu R; Xia Y; Tan L; Yang P; Lee JH; Li XJ; Hawke D; Zheng Y; Qian X; Lyu J; He J; Xing D; Tao YJ; Lu Z KAT2A coupled with the α-KGDH complex acts as a histone H3 succinyltransferase. Nature 2017, 552, 273–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Hong BS; Senisterra G; Rabeh WM; Vedadi M; Leonardi R; Zhang YM; Rock CO; Jackowski S; Park HW Crystal structures of human pantothenate kinases. Insights into allosteric regulation and mutations linked to a neurodegeneration disorder. J. Biol. Chem 2007, 282, 27984–27993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.