Abstract

Hypoxia can lead to different responses from cancer cells, including cell death or survival, partially depending on how long it is exposed. Patients with cancer and under hypoxic tumour conditions have a poorer prognosis and are at greater risk of metastasis. Physiological response to low oxygen levels is controlled by hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1. Curcumin, the major component of the rhizomes of Curcuma longa L., reduces HIF-1 levels and function, inhibiting the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In addition, curcumin efficiently inhibits the angiogenesis of vascular endothelial cells triggered by hypoxia. One of the most compelling features that drive continued interest in curcumin is the molecules’ modulation of initiation, promotion, and progression stages of cancer while concomitantly acting as a radiosensitizer and chemosensitizer for tumours. In this review, we discuss the role of curcumin in modulating hypoxia and investigate the mechanisms and regulatory factors of hypoxia in tumour tissues.

Keywords: curcumin, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), Von Hippel-Lindau, cancer, tumour hypoxia

Introduction

Cancer incidence and death rates have not decreased despite significant improvements in cancer therapy over the last 3 decades [1]. For cancer prevention and treatment, it is crucial to understand how genetic changes contribute to cancer’s genesis and progression. The development of specific cancer cell targeting methods has reduced tumour growth, progression, and metastatic spread while mitigating some adverse effects [2]. Many anti-cancer chemicals with diverse mechanisms of action have been isolated from plant sources [3–6]. Curcumin is the major component of the rhizomes of Curcuma longa L. [7] and was isolated in pure crystalline form from the turmeric plant in 1870 [8]. In the past 2 decades, curcumin and its derivatives have garnered much attention due to their bio-functional qualities, which include anti-inflammatory, anti-tumour, and antioxidant effects [9–15]. These functionalities are linked to the major structural components of curcumin [16]. Much research has been conducted on the structure-activity relationship (SAR) to improve curcumin’s physiochemical and biological properties.

Hypoxia, or low oxygen levels, is a characteristic of most tumours, caused by a disordered vasculature that provides oxygen to the growing tumour. The severity of hypoxia depends on the type of tumour [17]. When tumours multiply and expand rapidly, oxygen demand exceeds oxygen supply, and the distance between cells and existing vasculature grows, further hampering oxygen diffusion and creating hypoxia. Hypoxic tissues have poorer oxygenation than normal tissues and are typically between 1% and 2% oxygenated. As shown by the high proliferation rate of cancer, a decreased oxygen supply can cause hypoxia due to anaemia, a compromised arterial network, or excessive oxygen consumption [18]. Cells in this state are permanently unable to function normally because of reduced oxygen pressure. All cells adapt to hypoxia utilizing a homeostatic process. During oxygen deprivation, cells activate genes involved in glucose uptake, transport, metabolism, inflammation, erythropoiesis (EPO), angiogenesis, cell proliferation, pH regulation, and cell death [19, 20].

An important microenvironmental factor in tumours is pathological hypoxia, which facilitates the survival and propagation of cancer cells. Hypoxia can lead to different responses from cancer cells, including cell death or survival, partially depending on how long the cells are exposed. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced due to cycling hypoxia, contributing to tumour cell survival and progression. Hypoxia causes cellular responses that result in blood vessel formation, aggressiveness, metastasis, and resistance to treatment when these subunits are overexpressed. Cancer patients with hypoxia in their tumours have a poorer prognosis and are at greater risk of metastasis. Physiological response to low oxygen levels is controlled by the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) [21].

Curcumin reduces HIF-1 protein levels and function, inhibiting the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In addition, curcumin efficiently inhibits the angiogenesis of vascular endothelial cells triggered by hypoxia [22].

Curcumin inhibits HIF-1 activity, resulting in the downregulation of HIF-1-targeted genes. Curcumin can disrupt one of the 2 HIF-1 subunits, aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), in various cancer cell types, which can suppress the HIF-1 expression. However, ARNT expression can reverse curcumin-induced HIF-1 inhibition. According to previous research, curcumin can oxidize and ubiquitinate ARNT, resulting in its degradation by proteasomes. In response to turmeric administration, mice with hepatocellular carcinomas expressing Hep3B exhibited reduced tumour growth and expression of EPO, ARNT, and VEGF. According to these findings, curcumin’s anti-cancer properties are related to its ability to inactivate HIF-1 by ARNT degradation [23, 24].

In this review, we discuss the role of curcumin in modulating hypoxia and investigate the mechanisms and regulatory factors of hypoxia in tumour tissues.

Curcumin

Curcumin exerts its unique anti-tumour efficacy primarily via pleiotropic functions resulting in apoptosis and decreased tumour cell growth and metastasis [25–32]. Curcumin targets multiple cancer cell lines, including cancer of the prostate, neck, brain, head, lung, and breast [33]. However, due to its low water solubility and low chemical stability, curcumin’s use is limited. In contrast, due to its hydrophobicity, in the presence of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, curcumin can bind to fatty acid acyl chains within cellular membranes [25, 34]. The structure of curcumin has recently undergone numerous structural modifications in an attempt to overcome these limitations and to improve its anti-cancer potential; indeed, these modifications are designed to increase selective toxicity and improve the bioavailability of these modified curcumin agents against cancer cells. Alternatively, curcumin’s physiochemical characteristics and anti-cancer activity may be enhanced by utilizing alternative delivery strategies [33]. Curcumin possesses both preventive and therapeutic effects against cancer [35]. Traditional medicine has been used for centuries and is now being studied for its potential use in modern cancer treatment. It is a promising natural agent for cancer prevention and treatment. Curcumin exerts significant anti-cancer properties against numerous human cancer cells that can exert its properties on all the significant stages of carcinogenesis, including cell growth, proliferation, angiogenesis, survival, and metastasis via numerous cellular and molecular processes [36, 37].

HIF-1α molecular structure and regulation

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is a protein heterodimer composed of HIF-α and HIF-β subunits [38]. The 2 units are part of a family of transcription factors called PER-ARNT-single-minded proteins (PAS), which are components of basic helix loop helix (bHLH) proteins [39]. The HIF-α protein has 3 subunits, while the HIF-β protein has just 2 subunits [40]. Both HIF-1α and HIF-1β are constitutively expressed transcription factor family members with bHLH and PER-ARNT-SIM(PAS) domains, whereas HIF-1α is oxygen-sensitive and is destroyed by the proteasome pathway [38]. The C-terminal activation domain (CAD) regulates most HIF target genes, while the N-terminal transactivation domains of HIF-1α and HIF-2α are crucial for targeting gene specificity [41, 42]. HIF-1α is rapidly inactivated under normoxic conditions. HIF-1 proteins are hydroxylated by a HIF-prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) at the proline residue. The hydroxylated protein binds to the von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor protein (VHL). In order for HIF-1α to bind to pVHL as a component of the ECV complex (Elongin/Culin/VHL), HIF-1 must first be acetylated at internal lysine 532 by the acetyltransferase ARD1 [39, 43]. Through the 26S proteasome, this interaction quickly leads to poly-ubiquitylation and destruction. Hypoxic tension impairs PHD and prevents HIF-1α from being hydroxylated, which prevents it from binding to pVHL and from degradation. Because of this, HIF-1α builds up and moves into the nucleus, where it dimerizes with HIF-1β. The ATPase-directed chaperone Hsp90 is thought to provide a second mechanism accounting for HIF-1α stability and degradation. HIF-1’s conformation is altered by direct contact with Hsp90, which also causes HIF-1/ARNT heterodimers to form [44]. The balance between cellular HIF-1 production and destruction is precise under normal conditions. In addition to HIF-1’s stability in intra-tumour hypoxia, hyper-activation of HIF-1 and reduced degradation can also be seen under normoxic conditions. This probably happens because of several strong growth-stimulating factors (i.e. cytokines and growth factors) or oncogenic signalling factors (i.e. nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)). These factors may stimulate HIF-1, which may cause it to translate and activate downstream pathways that result in cancer [45]. Changes in the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) significantly impact the activation of the HIF-1α protein oncogenic and other oncogenic pathways [46]. PI3K cascade alterations usually aid in the growth of cancer through a variety of pathways, consisting of the constitutive activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), which activates PI3K, the PTEN (the loss of tumour suppressor phosphatase and tension homologue), PI3K mutations, and AKT improper regulation [47, 48]. Numerous target genes whose protein products control important body functions are affected by HIF.

HIF-1α: a cancer treatment target

Angiogenesis

Vascular differentiation is a vital part of the development and pathophysiology of tumours. HIF1 induces the production of stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF1), nitric oxide synthase (NOS), adrenomedullin (ADM), VEGF, angiopoietin 2 (ANGPT2), and stem cell factor (SCF) to stimulate the angiogenic response [49]. HIF-1 also regulates the activity of the G protein receptor, calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CRLR), which stimulates angiogenesis along with another pro-angiogenic protein, semaphorin 4D (Sema4D) [50].

Metastasis

HIF-1, which triggers epithelial-mesenchymal transition changes (EMT) and cancer metastasis, directly regulates the transcription factor TWIST [51]. In addition, HIF-1 controls the expression of adhesion molecules, E-cadherins, and matrix metalloproteases that are involved in the cellular processes [52].

Glucose metabolism

In cancer cells, anaerobic glycolysis replaces mitochondrial oxidative glycolysis. Glyceraldehyde-3-P-dehydrogenase (GAPDH), lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), hexokinases (HK 1 and 2), pyruvate kinase M (PKM), glucose transporters 1 and 3 (GLUT1, GLUT3), and solute carrier family 2 member (SLC2A1) are only a few of the enzymes modulated by HIF-1 [53]. It should be noted that HIF-1 also acts on 2 glycolytic enzymes, namely MCT4 (monocarboxylate transporter) and PDK1 (pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase), which causes a change in how cancer cells expend their energy [54, 55].

Cell survival and proliferation

Human embryonic stem (hES) cells’ full pluripotency requires hypoxic culture. Several growth factors, including EPO, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), insulin-like factor-2 (IGF2), transforming growth factor (TGF), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), are regulated by HIF-1 [55].

Effect of curcumin on HIF in cancer

The abnormal structural intra-tumoural blood vessels that are functionally present in cancer regions are evidence of hypoxic regions in human cancers due to their rapid cell proliferation. It is noteworthy that intra-tumoural hypoxia increases the risk of invasion, metastasis, treatment failure, and patient death [56]. Curcumin suppresses the HIF-1 pathway under hypoxia, which decreases VEGF expression in both tumour and stromal cells and suppresses angiogenesis. The tumour vasculature is aberrant because tumour-activated endothelial cells have unique gene expression profiles and luminal cell-surface receptors. The leaky and constricted blood arteries that characterize this aberrant vascular network also cause more localized hypoxia, producing a vicious cycle. As a result, tumour cells undergo a ROS (superoxide)-generating hypoxia-reoxygenation cycle that, perhaps via enhanced ROS (superoxide anion) generation, is responsible for a more aggressive phenotype [57]. Another characteristic of solid tumours is low extracellular pH, and acidosis is caused by hypoxia in the tumour microenvironment [58, 59]. A hypoxic environment around tumoural cells facilitates the accumulation of HIF-1α and HIF-2α [60].

Curcumin promotes transcriptional activation of HIF1, which induces the expression of genes related to cellular metabolism and growth, regulation of angiogenesis, cell survival, and death in a hypoxic environment. At the same time, hypoxic signalling is involved in embryonic development and can be exploited in the physiologic modulation of tumour cells [61]. Low oxygen levels induce tumour cells to switch from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, leading to the generation of metabolic acids in most malignancies [62]. These alterations, like enhanced angiogenesis, are mediated by HIF-1α-driven transcription, which upregulates glucose transporters and glycolysis-related genes [63]. Li et al. [64] have found a significant correlation between hypoxia, GLUT-1, and the uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) [65], a key signalling pathway that regulates metabolic activities is the mTOR pathway. By controlling important transcription factors like HIF-1α, mTOR affects numerous locations along the glycolytic process [66]. HIF-1α’s expression is reliant on mTORC1 and mTORC2 [67]. Both mTORC1 and mTORC2 are crucial for tumour cells’ glucose absorption and glycolytic metabolism [68]. Therefore, using mTOR inhibitors to regulate the metabolism of tumours and the malignant microenvironment will become a cutting-edge anti-tumour therapy [69].

Increasing evidence has described a high level of HIF-1α in malignant tumoral cells, whereas normal cells carry low amounts of HIF-1α. Notably, HIF-1 inducible genes and increased levels of HIF-1α are strongly accompanied by the aggressive behaviour of tumours and, therefore, poorer prognosis. Thus, HIFs are essential for tumour progression; conversely, their repression has decreased tumoural growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis [70]. Recently, HIF-1-inhibiting techniques have emerged as a new therapeutic target in cancer therapy. Additionally, due to its anti-cancer potency through affecting multiple gene transcription and signalling pathways, curcumin, highlighting HIF inactivation in an oxygen-, concentration-, and time-dependent manner, has attracted increased attention in oncology. Curcumin treatment led to HIF-1α degradation in primary cultures of human cancer cells but HIF-1α enhancement under normoxic conditions. One of the most compelling abilities that direct continued interest is curcumin’s capacity to suppress all cancer initiation, promotion, and progression stages and act as a radiosensitizer and chemosensitizer for tumours [19].

Observations of the present research revealed that the anti-tumour effects of curcumin are not only exerted by modulation by expression of key cell survival regulatory proteins but also via modulation of disparate signalling and regulatory pathways. For example, exposure of tumour-bearing mice cells to curcumin resulted in pro-apoptotic PUMA gene expression and activation of caspase-3, implicating the involvement of curcumin in caspase-dependent apoptosis. Interestingly, HIF-1α has been shown to play a regulatory role in the expression of multidrug resistance-1 (MDR-1) and PUMA. Apoptosis induction and tumour cell survival regulation have been reported as the results of MDR-1 expression. Altered tumoural microenvironment O2 saturation and pH condition might also contribute to the modulation of MDR-1 expression [71, 72].

The poor bioavailability of curcumin in preclinical studies has led to the development of several novel curcumin analogues. Bromophenol curcumin [73] and tetrahydrocurcumin [74] exert antiangiogenic effects in cervical cancer of animal models through the Akt/VEGF signalling pathway, and also by reducing HIF-1α at both microvascular concentrations and expression levels.

Platinum-based (DDP) drugs are the basis for chemotherapeutic treatment of various human tumours and have significantly improved patient outcomes. In recent years, multidrug resistance by cancer cells has been a significant therapeutic obstacle, with less than a 15% survival rate at 5 years. HIF-1α has been identified as a unique mediator of MDR proteins. MDR may be attributed to the fact that amplified HIF-1α levels were found in the DDP-resistant lung cancer cell lines under normoxic conditions [75]. In other studies, oxygen deprivation as the key stimulator of HIF-1α overexpression was closely correlated with DDP and doxorubicin resistance in lung cancer [76] and treatment failure in early-stage invasive cervical cancer [77]. On the other hand, HIF-1α knockdown by HIF-1α-specific siRNA showed a promising reduction in chemoresistance in the human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cell line [78]. Combination therapy of DDP with curcumin significantly reversed DDP resistance via abrogation of A549/DDP cell proliferation, disruption in HIF-1α amplification, and induced apoptosis through caspase-3 activation and HIF-1α degradation [75]. These findings help to reason the curcumin’s employment as an anti-tumour agent with therapeutic potential to raise the efficacy of the current regimens in cancer treatment.

Modulatory pathways

Although hypoxia is considered a primary inducer of HIF-1 transcription, other stressors can also motivate HIF-1 expression, such as a rise in the HIF-1α level following endoplasmic reticulum stress. The thioredoxin (Trx) system is a key antioxidant system generally overexpressed in hypoxic tumour cells, and it influences HIF-1α expression [79]. Under hypoxic stress, Trx inhibitors can prevent angiogenesis by suppressing HIF-1. With its potential to target the Trx system, curcumin is considered an anti-cancer drug via mechanisms of reduction in intracellular-redox potential, the elevation of oxidative stress, and induction of cell death [80].

In many cancers, chemotherapeutic agents reduce primary tumour growth by inhibiting tumour angiogenesis. Anti-VEGF therapy, however, has had a poor response, because intra-tumoral hypoxia associated with impaired angiogenesis is responsible for the formation of HIF-1-dependent metastases and the expansion of cancer stem cells. Experiments have shown that overexpression of HIF-1 in colorectal and pancreatic cancer cells increases vessel density and tumour growth. Notably, some cancer studies have found a positive correlation between overexpression of HIF-1, resistance to radiotherapy, and mortality of the patients [56]. Furthermore, curcumin may play pivotal roles in tumour suppression via the downregulation of HIF-1α protein levels and suppression of pro-angiogenic VEGF under hypoxia-induced angiogenesis of the tumour environment.

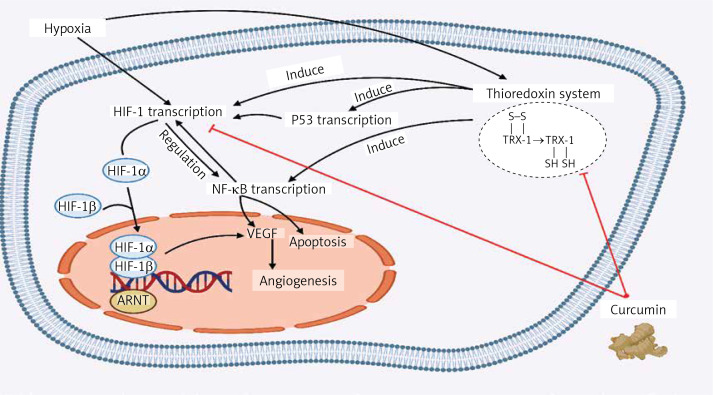

Curcumin restrains the amplification of VEGF utilizing NF-κB regulation. On the other hand, NF-κB and HIF-1α regulate the expression of one another interdependently. They are known to be involved in similar processes like cell apoptosis. Under severe hypoxia, rising p53 levels promote Mdm2-dependent HIF-1α degradation. The p53 tumour suppressor prevents hypoxia-induced HIF-1α expression by augmenting its proteasomes and ubiquitination (Figure 1) [81].

Figure 1.

The effect of curcumin on the modulatory pathways of tumour cells. Under hypoxic condition the thioredoxin inhibitors such as curcumin can prevent angiogenesis by suppressing HIF1, which results in the elevation of oxidative stress, and induction of apoptosis. Also, curcumin may cause tumour suppression by downregulating the HIF-1α protein levels and suppressing the VEGF, which can prevent angiogenesis

ARNT – aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator, NF-κB – nuclear factor-kappa B, VEGF – vascular endothelial growth factor, Trx – thioredoxin, HIF-1 – hypoxia inducible factor.

The balance of Th1/Th2 cytokines is associated with tumour cell apoptosis. Indeed, in tumour-bearing mice, curcumin therapy has decreased the level of Th2 and inhibited the expression of stress-adapting proteins Hsp70 and Hsp90 and anti-apoptotic Bcl2 proteins involved in cell survival regulation [82]. Studies show that T-regulatory (Treg), tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and cells are highly infiltrated in intertumoural hypoxic regions [69]. During prolonged hypoxia exposure, activated HIF-1α may result in cytotoxic lymphocyte inactivation, such as CD8 T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, impairing their anti-tumour activity [83, 84]. Additionally, increased lactate synthesis in the tumour microenvironment (TME) can render cytotoxic lymphocytes, including CD8 T and NK cells, diminishing their anti-tumour activity [85]. The elevation of HIF-1α-dependent PD-L1 expression in tumour cells, and antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages, which is critical in suppressing anti-tumour immunity by cancer cells, is strongly influenced by hypoxia [86]. Hypoxia accelerates B cells’ glycolytic rate, inhibiting class switching and decreasing proliferation while increasing death. At crucial points in B cells’ development, HIF will become active, which may help determine how they develop and function. Reduced germinal centre B cells, impaired affinity maturation, recall response, and early memory B-cell development are all effects of constitutive HIF stabilization caused by Vhl deletion. Therefore, the overactivation of HIF caused by hypoxia diminishes B cell function [87, 88]. This suggests another mechanism of the decline in tumour cell survival following curcumin administration associated with HIF-1α, in accordance with the observation that upstream modulation in the expression of HIF-1α is attributed to the regulation of Hsp70, Hsp90, and Bcl2 [89, 90].

Several studies have demonstrated the anti-cancer effect of curcumin, focusing on targeting subunits of HIF-1 and HIF-2α. Ströfer et al. explored curcumin’s inhibitory effect with higher concentrations, and its result revealed lower HIF-1 subunits and HIF-2α protein levels in MCF-7 breast cells, Hep3B, and HepG2 liver cells [81]. Another study showed that curcumin negatively regulates stable HIF-1 protein levels under hypoxia, but it did not affect the mRNA level of HIF-1 in HepG2 cells [74]. In another study, Sarighieh et al. investigated curcumin’s ability to control HIFs expression under both hypoxic and normoxic conditions in MCF-7 cells and cancer stem-like cells (CS-LCs), in which curcumin treatment decreased the level of HIF2α protein expression but did not affect HIF-1α expression. Moreover, it was hypothesized that curcumin treatment in CS-LCs could inactivate HIF-1 through degradation of ARNT, and it helped inhibit tumour metastasis, other than the direct inhibitory effect on its transcription [91]. Another study also demonstrated that of the 2 subunits of HIF-1, curcumin only destabilized ARNT in several cancer cell types, and also ARNT expression helped curcumin inhibit HIF-1. This study’s results suggested that curcumin’s anti-tumour activity is due to the inactivation of HIF-1 through the degradation of ARNT [23].

Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-mono-oxygenase activation protein gamma polypeptide (YWHAG) is a prognostic factor in cervical cancer of HeLa and C33A cells involved in cervical cancer. A positive correlation between YWHAG and HIF-1α expression has been detected in cervical cancer cells, because YWHAG expression promotes further HIF-1α overexpression. This interaction affects the proliferative and invasive capacity of cervical cancer cells. On the other hand, YWHAG knockdown leads to a reduction of the pentose phosphorylation pathway-related proteins, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 2 and MMP9 expression, and glucose uptake. Combining cisplatin with curcumin promotes cell apoptosis through the YWHAG pathway and its interaction with HIF-1α, affecting the pentose phosphorylation pathway [92].

Different cancers

The remarkable preventive and therapeutic effects of curcumin can be exerted through various signalling pathways, as mentioned above. Therefore, herein we provide up-to-date evidence and findings of clinical studies on curcumin contributions and its effect on tumour cell survival and death by focusing on its anti-cancer effects via HIF signalling pathway regulation.

In vitro studies

While curcumin has shown benefits in different models of cancers by applying a wide variety of cellular properties, including anti-inflammatory activity by suppression of NF-κB induced by TNF-α or inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8 in response to acid exposure, an antioxidant effect by activating PPAR-γ, and anti-bacterial and antiproliferative activities, recent interests have focused on its use in cancer treatment via HIF regulation [93] (Table I).

Table I.

Effect of curcumin on HIF in different cancers

| Author | Year | Study type | Cancer | Type of cell line or animal study | Biological activity | Curcumin dosage; and duration | Anti-cancer effect of curcumin via HIFs | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ye et al. [75] | 2012 | In vitro | lung adenocarcinoma | human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells, cis-platin (DDP) sensitive A549 and resistant A549/DDP cell lines | Pro-apoptotic; ↓ Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α | DDP (control), DDP + Cur (5, 10, 15, 20 μM); 12 h | Curcumin promoted apoptosis via HIF-1α degradation and a decrease in HIF-1α-dependent P-gp expression | Combined regime of curcumin and DDP therapy significantly suppressed A549/DDP cell proliferation, reduced DDP resistance, and triggered cancer cell apoptosis -HIF-1α abnormality was found to be associated with DDP resistance |

| Du et al. [101] | 2015 | In vitro | Prostate cancer | PC3 cells; Human prostate cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) | Anti-inflammatory; ↓ IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 | 25 μM curcumin; 72 h | Curcumin inhibits CAF-induced EMT via suppressing MAOA/mTOR/HIF-1α signalling, by inducing silence of HIF-1α by shRNA in PC3 cells |

Curcumin abrogated CAF-induced invasion, inhibited EMT, ROS production, and CXCR4 and IL-6 receptor expression |

| Man et al. [127] | 2020 | In vivo | HCC | Kunming mice; H22 tumour cells inoculated in mice | Antioxidant; ↓ LDH | 25 mg/kg/day Curcumin; 3 weeks | Curcumin affects via anaerobic glycolysis suppression through HIF-1α and LDH inhibition | Curcumin protects against the progression of liver cancer by affecting α-fetoprotein levels in liver tissues |

| Wang et al. [128] | 2020 | In vitro | Mesenchymal stem cells therapy | Rat BMSCs | Pro-apoptotic; ↑ Caspases | 10 μM curcumin; 2 h | Caspase-3 activation happens as a result of HIF-1 destabilization and up-regulation of PGC-1α and SIRT3 | Hypoxic preconditioning and curcumin significantly improved cell survival, mitochondrial function in BMSCs, and their therapeutic properties |

| Guo et al. [129] | 2022 | In vitro | Pancreas cancer | Two pancreatic cancer cell lines, PANC-1 and SW1990 | Pro-apoptotic; ↑ berlin 1 | Curcumin (0, 20, 40, and 60 μM); 48 h | Curcumin inhibited the interaction between Beclin1 and HIF-1α, thereby reducing cellular ATP and the expression levels of HSP70, HSP90, and von Hippel-Lindau protein | Curcumin can affect the glycolytic pathway and inhibit cell proliferation of pancreatic cancerous cells |

| Vishvakarma et al. [89] | 2010 | In vivo | T cell lymphoma | Murine model, serial transplantation of Dalton’s lymphoma in BALB/c mice | Pro-apoptotic; ↓ Bcl-2 | Pre-optimized dose of 50 mg/kg body weight in 0.2 ml PBS at every 48-h interval until day 15 | Modulation of HIF-1α expression was attributed in decline Bcl2, Hsp70 and Hsp90 expression | Curcumin-treated mice cells were observed to resist to decrease in pH conditions |

| Lou et al. [105] | 2018 | In vitro | Hemangioma | HemECs | Anti-cancer; ↓ VEGF | Serial dilution of curcumin at concentrations of 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 mM; 48 h | Curcumin down-regulated the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins MCL-1, HIF-1α, and VEGF | Curcumin administration induced apoptosis in HemECs, by caspase-3 activation, and cleavage of PARP in the treated cells |

| Monteleone et al. [106] | 2018 | In vitro | CML | Human CML cell lines K562 and LAMA84 | Pro-apoptotic; ↓ Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α | 20 μM curcumin; 24 h | Affecting HIF-1α targets resulted in the decrease of several proteins involved in glucose metabolism | Curcumin treatment-induced reduction of BCR-ABL expression at both mRNA and protein level Curcumin affected metabolic enzyme profiles by decreasing HIF-1α activity due to the miR-22-mediated down-regulation of IPO7 expression |

| Maiti et al. [130] | 2018 | In vitro | Glioblastoma multiforme | U-87MG, GL261, F98, C6-glioma, and N2a cells | Pro-apoptotic; ↓ Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α | Curcumin 25 μM; 24 h | HIF-1α knockdown led to decrease in NIX or BNIP3 levels and glioma cells migration | Solid lipid Curcumin particles induced greater cell death in U-87MG cells |

| Chatterjee et al. [131] | 2021 | In vitro | Oral cancer | Oral cancer cells (H357) | Antioxidant; NO synthase | Curcumin 100 μg; 96 h | Curcumin works through NO enhancement via HIF-1α-mediated iNOS activation | Administration of combined Curcumin-Veliparib by utilizing PI3K-AKT-eNOS pathway led to suppressed angiogenesis |

| Sarighieh et al. [91] | 2020 | In vitro | Breast adenocarcinoma | MCF-7 (human breast adenocarcinoma) and CS-LCs | Pro-apoptotic; ↓ Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α | Different concentrations (5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 μM) of curcumin; 24 h | Curcumin inhibited tumour progression, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis by down-regulation of HIF-1 via ARNT degradation | Under treatment with curcumin, early apoptosis occurred in CSC-LCs more than in MCF-7 cells under hypoxic conditions |

EMT – epithelial to mesenchymal transition, HCC – hepatocellular carcinoma, BMSCs – bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, ATP – adenosine triphosphate, HemECs – primary human haemangioma endothelial cells, VEGF – vascular endothelial growth factor, PARP – poly (adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase, MCL-1 – myeloid cell leukemia-1, CML – chronic myelogenous leukaemia, CS-LCs – cancer stem-like cells, ARNT – aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator.

In non-small cell lung cancer, curcumin has been shown to promote apoptosis by inducing anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 degradation [94]. In a recent study, suppression of the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk resulting from combined curcumin and DDP treatment suggests that curcumin via a caspase-3-dependent mechanism can sensitize DDP cytotoxicity by triggering A549/DDP apoptosis. HIF-1α overexpression was detected in DDP-resistant cells under normoxic conditions [75]. Likewise, as an adjuvant chemotherapeutic agent in lung cancer treatment, curcumin has played a major role in conquering MDR and improving treatment efficiency by promoting A549 and A549/DDP cell apoptosis via a miRNA mechanism. Resistance to cisplatin, the most common chemotherapeutic agent used in NSCLC, is reversed by curcumin [95].

Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies have shown curcumin’s capability to abrogate the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells through inhibition of COX-2, CD-31, VEGF, and IL-8 and suppression of TGF-β via NF-κB and HIF-1α downregulation [96]. Another study showed that a new synthetic curcumin analogue (difluorinated curcumin) could inhibit miR-21, miR-210, HIF-1α, and cancer stem cell (CSC) signature gene markers in human pancreatic cancer cells in vitro under hypoxic conditions [97]. In another study, curcumin, in a dose-dependent manner, either as a single agent or in combination with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), resulted in chemoresistance reduction of gastric cancer cells via phosphorylation of STAT3 [98], the exact anti-cancer mechanism of curcumin has been observed in squamous carcinoma cells [99]. In colon cancer cells, curcumin has been reported to induce apoptosis and restrain the growth of cancer cells through repression of specificity protein (Sp) transcription factors Sp1,3,4 and Sp-regulated genes, suppression of genes like NF-κB (p65 and p50), BCL-2, cyclin D1, and hepatocyte growth factor receptor (c-MET) [100]. As in PC3 prostate cancer cells, curcumin suppressed fibroblast-induced invasion and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via MAOA/mTORC1/HIF-1α signalling pathway repression [101].

The reported in vitro and in vivo data on hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) showed that accumulation of hypoxia-mediated HIF-1α leads to stimulation of ß-catenin expression increase in EMT process, and enhancement in invasive and metastatic behaviour [102]. PD-L1 protein expression, an enhancer of T-cell activation, which can be a direct target of HIF-1α blockade under hypoxia, is upregulated when STAT3 and HIF-1α are jointly overexpressed. Accordingly, Zuo et al. proved that crosstalk between HIF-1α and STAT3 signalling pathways was the mechanism of curcumin action in significant downregulation of PD-L1 expression when applied as a co-treatment in hepatic cancer [103].

Synthesized formulations called ceria nanoparticles, coated with dextran and loaded with curcumin, represent promising small-molecule drug therapy for neuroblastoma cells while producing only minor toxicity in healthy cells. This induced stabilizing HIF-1α, prolonged oxidative stress, and induced caspase-dependent apoptosis with a specifically more pronounced effect in MYCN-amplified cells [104]. It has also been reported that curcumin shows potent antiproliferative and apoptotic features in haemangioma endothelial cells by recruiting the HIF-1α-VEGF axis and its contribution in suppression of MCL-1 as a key downstream effector of HIF-1α pathway [105].

According to the literature supporting curcumin’s capability in the regulation of miRNA expression, curcumin affects nuclear traffic by inhibiting specific importins related to HIF-1α nuclear translocation, like IPO7 together with CRM1 (exportin1 or Xpo1), which was found to be down-regulated in curcumin-treated K562 cells in CML treatment. Interestingly, it was demonstrated that curcumin could significantly inhibit HIF-1α activity without affecting its expression and employing a new molecular scenario, which was up-regulation of miR-22 expression level [106].

Curcumin pretreatment has shown protective effects against severe relocated conditions, so-called hypoxia and reoxygenation (H/R) triggered injury after BMSCs-based cell therapy. Curcumin pretreatment remarkably reduced H/R-induced mitochondrial dysfunction by expediting the production of adenosine triphosphate and suppressing ROS accumulation. Furthermore, curcumin induced Epac1 and Akt activation while Erk1/2 and p38 deactivation and HIF-1α destabilization in BMSCs [107].

Another study also showed that expression of HIF-1α was significantly upregulated in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) associated with areca quid chewing, and arecoline-induced HIF-1α expression was down-regulated by NAC, curcumin, PD98059, and staurosporine [108].

Another study showed that in addition to Let-7C aerobic glycolysis inhibition by targeting HIF-1α, it can regulate cancer progression and metabolism by inhibiting the lin28/PDK1 pathway. Furthermore, let-7C can regulate PDK1 expression through HIF-1α inhibition [109]. Obaidi et al. reported the cancer chemosensitization potential of curcumin through the induction of let-7C on RCC [110].

In vivo animal and human studies

Consistent with the strong in vitro studies and the many molecular efficacies of curcumin involved in the progression and promotion of cancer, which have been demonstrated in cell culture systems, it has provided a good basis to progress the studies on curcumin into animal and human subjects.

Curcumin’s efficacy as a chemopreventive agent in GI cancers, including oral [111], oesophageal [112], stomach [113], colon [113], liver [114], and various extra-intestinal malignancies such as head and neck squamous carcinoma [115], lung [116], kidney [117], and haematological cancers [118], in different animal models, mainly rodent, is well established. Treatment with curcumin and its analogues in mice carrying HCT116 and HT-29 cell xenografts have resulted in the reduction of angiogenesis in gastrointestinal cancers, and due to the low bioavailability of orally administered curcumin, gastrointestinal cancers, and especially oesophageal cancer, they seem to be more suitable for curcumin as an anti-cancer regime [119, 120]. Similarly, in a mouse model, curcumin application reduced tumourspheres of H460 cells via inhibition of the JAK2/STAT3 signalling pathway [121].

In another study, by Zhao et al., the administration of curcumin attenuated the degree of fibrosis and inhibited the proliferation of hepatic stellate cells in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in rats [122]. Recent evidence indicated the profound effect of HIF-1 on regulating profibrotic mediator production by macrophages and the transcription of central mediators of tissue remodeling, such as TIMP-1, PAI-1, and CTGF pathways. It was concluded that liver fibrosis is promoted by HIF-1α and at least partly through the ERK pathway, an important marker in fibrogenesis [122].

More recently, curcumin has been evaluated in several clinical studies as a potential therapeutic in human cancers. In one study, oral administration of curcumin to 25 patients with oral leukoplakia, gastric metaplasia, bladder cancer, cervical intraepithelial metaplasia, or Bowen’s disease resulted in tumour regression in a proportion of these patients [123]. In other uncontrolled studies, topical application of curcumin in 62 patients with oral cancerous lesions led to tumour shrinkage in 10% of the patients and symptom reduction by 70% [124]. High-dose oral curcumin administration resulted in disease stability or regression in 4 out of 21 patients with advanced fatal pancreatic cancer [125]. Also, another clinical trial reported significant clinical outcome improvements in curcumin combined with a standard docetaxel chemotherapy regime in patients with advanced and metastatic breast cancer [126]. Ultimately, as the promising results and interests in the therapeutic effect of curcumin continue to grow, several other clinical trials are ongoing, investigating its chemotherapeutic potential in gut cancers, pancreatic cancer, systemic inflammatory diseases, and Alzheimer’s disease.

Conclusions

Curcumin exhibits pleiotropic properties, interacting with molecular targets and intracellular signalling in cancer pathogenesis. However, its anti-tumour efficacy via regulation of hypoxia signalling pathways or inhibition of HIF-target genes has received little attention in this field. Due to curcumin’s non-toxicity and tolerability reported in several trials, it is considered a therapeutic supplement in cancer treatment. However, low solubility and poor bioavailability have limited its efficacy profile and hence demand extensive research to overcome these problems and to bring out novel formulations with maximum efficacy. Curcumin’s inhibitory effect on cancer cell development, invasion, and metastasis via targeting of HIF subunits in combination with promising results of in vitro, in vivo, and human trials have provided a passionate basis to develop ongoing and further studies to bring curcumin as a therapeutic agent in the treatment of human cancer.

Conflict of interest

EG is Director of Research and Science at Isagenix International, LLC (Gilbert, AZ, USA). Isagenix International sells foods and dietary supplements containing curcumin; MB – speakers bureau and consultancy fee: Kogen, Viatris; Grants from Viatris, shareholder in Nomi Biotech Corporation and Dairy Biotechnologies, CMDO at the Longevity Group (LU).

References

- 1.Gupta A, Pandotra P, Sharma R, Kushwaha M, Gupta S. Marine resource: a promising future for anticancer drugs. Stud Nat Prod Chem 2013; 40: 229-35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Umar A, Dunn BK, Greenwald P. Future directions in cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer 2012; 12: 835-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta A, Khan S, Manzoor M, et al. Anticancer curcumin: natural analogues and structure-activity relationship. Studies Natural Prod Chem 2017; 54: 355-401. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang S, Yan J, Chen X, et al. Ginsenoside Rh2 inhibits thyroid cancer cell migration and proliferation via activation of miR-524-5p. Arch Med Sci 2022; 18: 164-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Periasamy VS, Athinarayanan J, Ramankutty G, Akbarsha MA, Alshatwi AA. Plumbagin triggers redox-mediated autophagy through the LC3B protein in human papillomavirus-positive cervical cancer cells. Arch Med Sci 2022; 18: 171-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang H, Yang S, Lin T. Bergamottin exerts anticancer effects on human colon cancer cells via induction of apoptosis, G2/M cell cycle arrest and deactivation of the Ras/Raf/ERK signalling pathway. Arch Med Sci 2022; 18: 1572-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alibeiki F, Jafari N, Karimi M, Peeri Dogaheh H. Potent anti-cancer effects of less polar Curcumin analogues on gastric adenocarcinoma and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goel A, Kunnumakkara AB, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin as “Curecumin”: from kitchen to clinic. Biochem Pharmacol 2008; 75: 787-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagahama K, Utsumi T, Kumano T, Maekawa S, Oyama N, Kawakami J. Discovery of a new function of curcumin which enhances its anticancer therapeutic potency. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 30962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassanzadeh S, Read MI, Bland AR, Majeed M, Jamialahmadi T, Sahebkar A. Curcumin: an inflammasome silencer. Pharmacol Res 2020; 159: 104921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cicero AFG, Sahebkar A, Fogacci F, Bove M, Giovannini M, Borghi C. Effects of phytosomal curcumin on anthropometric parameters, insulin resistance, cortisolemia and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease indices: a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Eur J Nutrition 2020; 59: 477-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keihanian F, Saeidinia A, Bagheri RK, Johnston TP, Sahebkar A. Curcumin, hemostasis, thrombosis, and coagulation. J Cell Physiol 2018; 233: 4497-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khayatan D, Razavi SM, Arab ZN, et al. Protective effects of curcumin against traumatic brain injury. Biomed Pharmacother 2022; 154: 113621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mokhtari-Zaer A, Marefati N, Atkin SL, Butler AE, Sahebkar A. The protective role of curcumin in myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury. J Cell Physiol 2018; 234: 214-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panahi Y, Sahebkar A, Amiri M, et al. Improvement of sulphur mustard-induced chronic pruritus, quality of life and antioxidant status by curcumin: results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Nutrition 2012; 108: 1272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aggarwal BB, Deb L, Prasad S. Curcumin differs from tetrahydrocurcumin for molecular targets, signaling pathways and cellular responses. Molecules 2014; 20: 185-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muz B, de la Puente P, Azab F, Kareem Azab A. The role of hypoxia in cancer progression, angiogenesis, metastasis, and resistance to therapy. Hypoxia 2015; 3: 83-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Laarhoven HW, Kaanders JH, Lok J, et al. Hypoxia in relation to vasculature and proliferation in liver metastases in patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Radiation Oncol Biol Phys 2006; 64: 473-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bahrami A, Atkin SL, Majeed M, Sahebkar A. Effects of curcumin on hypoxia-inducible factor as a new therapeutic target. Pharmacol Res 2018; 137: 159-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Höckel M, Vaupel P. Biological consequences of tumor hypoxia. Semin Oncol 2001; 28 (Suppl 8); 36-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozaki T, Nakamura M, Ogata T, Sang M, Shimozato O. The functional interplay between pro-oncogenic RUNX2 and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) during hypoxia-mediated tumor progression. Curr Human Cell Res Appl Regulation Signal Transd Human Cell Res 2017; 85-98. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bae MK, Kim SH, Jeong JW, et al. Curcumin inhibits hypoxia-induced angiogenesis via down-regulation of HIF-1. Oncol Rep 2006; 15: 1557-62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi H, Chun YS, Kim SW, Kim MS, Park JW. Curcumin inhibits hypoxia-inducible factor-1 by degrading aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator: a mechanism of tumor growth inhibition. Mol Pharmacol 2006; 70: 1664-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan Z, Zhuang J, Ji C, Cai Z, Liao W, Huang Z. Curcumin inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma growth by targeting VEGF expression. Oncol Letters 2018; 15: 4821-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunnumakkara AB, Bordoloi D, Padmavathi G, et al. Curcumin, the golden nutraceutical: multitargeting for multiple chronic diseases. Br J Pharmacol 2017; 174: 1325-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panahi Y, Fazlolahzadeh O, Atkin SL, et al. Evidence of curcumin and curcumin analogue effects in skin diseases: a narrative review. J Cell Physiol 2019; 234: 1165-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marjaneh RM, Rahmani F, Hassanian SM, et al. Phytosomal curcumin inhibits tumor growth in colitis-associated colorectal cancer. J Cell Physiol 2018; 233: 6785-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohajeri M, Sahebkar A. Protective effects of curcumin against doxorubicin-induced toxicity and resistance: a review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2018; 122: 30-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Momtazi AA, Sahebkar A. Difluorinated curcumin: a promising curcumin analogue with improved anti-tumor activity and pharmacokinetic profile. Curr Pharm Design 2016; 22: 4386-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohammed ES, El-Beih NM, El-Hussieny EA, El-Ahwany E, Hassan M, Zoheiry M. Effects of free and nanoparticulate curcumin on chemically induced liver carcinoma in an animal model. Arch Med Sci 2021; 17: 218-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Afshari AR, Jalili-Nik M, Abbasinezhad-Moud F, et al. Anti-tumor effects of curcuminoids in glioblastoma multiforme: an updated literature review. Curr Med Chem 2021; 28: 8116-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohajeri M, Bianconi V, Ávila-Rodriguez MF, et al. Curcumin: a phytochemical modulator of estrogens and androgens in tumors of the reproductive system. Pharmacol Res 2020; 156: 104765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomeh MA, Hadianamrei R, Zhao X. A review of curcumin and its derivatives as anticancer agents. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20: 1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsukamoto M, Kuroda K, Ramamoorthy A, Yasuhara K. Modulation of raft domains in a lipid bilayer by boundary-active curcumin. Chem Commun 2014; 50: 3427-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beevers CS, Li F, Liu L, Huang S. Curcumin inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin-mediated signaling pathways in cancer cells. Int J Cancer 2006; 119: 757-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qadir MI, Naqvi STQ, Muhammad SA, Qadir M, Naqvi ST. Curcumin: a polyphenol with molecular targets for cancer control. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev 2016; 17: 2735-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu F, Gao S, Yang Y, et al. Antitumor activity of curcumin by modulation of apoptosis and autophagy in human lung cancer A549 cells through inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Oncol Rep 2018; 39: 1523-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1995; 92: 5510-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eda S, Vadde R, Jinka R. Role of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) in the initiation of cancer and its therapeutic inhibitors. In: Role of Transcription Factors in Gastrointestinal Malignancies. Nagaraju GP, Bramhachari PV (eds.). Springer; 2017: 131-59. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Unwith S, Zhao H, Hennah L, Ma D. The potential role of HIF on tumour progression and dissemination. Int J Cancer 2015; 136: 2491-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor S. From single cell to single molecule: elucidation of the intracellular dynamics of the Hypoxia Inducible Factor (HIF). The University of Liverpool (United Kingdom) 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu CJ, Sataur A, Wang L, Chen H, Simon MC. The N-terminal transactivation domain confers target gene specificity of hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1α and HIF-2α. Mol Biol Cell 2007; 18: 4528-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson CM, Ohh M. The multifaceted von Hippel–Lindau tumour suppressor protein. FEBS Letters 2014; 588: 2704-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katschinski DM, Le L, Heinrich D, et al. Heat induction of the unphosphorylated form of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α is dependent on heat shock protein-90 activity. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 9262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schnitzer S, Schmid T, Zhou J, Brüne B. Hypoxia and HIF-1α protect A549 cells from drug-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 2006; 13: 1611-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agani F, Jiang BH. Oxygen-independent regulation of HIF-1: novel involvement of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2013; 13: 245-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bahrami A, Khazaei M, Shahidsales S, et al. The therapeutic potential of PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors in breast cancer: rational and progress. J Cell Biochem 2018; 119: 213-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bahrami A, Hasanzadeh M, Hassanian SM, et al. The potential value of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway for assessing prognosis in cervical cancer and as a target for therapy. J Cell Biochem 2017; 118: 4163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kelly BD, Hackett SF, Hirota K, et al. Cell type–specific regulation of angiogenic growth factor gene expression and induction of angiogenesis in nonischemic tissue by a constitutively active form of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Circ Res 2003; 93: 1074-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nikitenko LL, Smith DM, Bicknell R, Rees MC. Transcriptional regulation of the CRLR gene in human microvascular endothelial cells by hypoxia. FASEB J 2003; 17: 1499-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang MH, Wu MZ, Chiou SH, et al. Direct regulation of TWIST by HIF-1α promotes metastasis. Nat Cell Biol 2008; 10: 295-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krishnamachary B, Zagzag D, Nagasawa H, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1-dependent repression of E-cadherin in von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor–null renal cell carcinoma mediated by TCF3, ZFHX1A, and ZFHX1B. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 2725-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Amirkhah R, Naderi-Meshkin H, Mirahmadi M, Allahyari A, Sharifi HR. Cancer statistics in Iran: towards finding priority for prevention and treatment. Cancer Press J 2017; 3: 27-38. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Obach M, Navarro-Sabaté À, Caro J, et al. 6-Phosphofructo-2-kinase (pfkfb3) gene promoter contains hypoxia-inducible factor-1 binding sites necessary for transactivation in response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 53562-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim JW, Tchernyshyov I, Semenza GL, Dang CV. HIF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metabol 2006; 3: 177-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang CM, Yu J. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 as a therapeutic target in cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 28: 401-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Croix BS, Rago C, Velculescu V, et al. Genes expressed in human tumor endothelium. Science 2000; 289: 1197-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chiche J, Brahimi-Horn MC, Pouysségur J. Tumour hypoxia induces a metabolic shift causing acidosis: a common feature in cancer. J Cell Mol Med 2010; 14: 771-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ward PS, Thompson CB. Metabolic reprogramming: a cancer hallmark even warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell 2012; 21: 297-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shan B, Schaaf C, Schmidt A, et al. Curcumin suppresses HIF1A synthesis and VEGFA release in pituitary adenomas. J Endocrinol 2012; 214: 389-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ledda A, Belcaro G, Dugall M, et al. Meriva®, a lecithinized curcumin delivery system, in the control of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a pilot, product evaluation registry study. Panminerva Medica 2012; 54 (1 Suppl 4): 17-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang G, Li J, Wang X, et al. The reverse Warburg effect and 18F-FDG uptake in non-small cell lung cancer A549 in mice: a pilot study. J Nuclear Med 2015; 56: 607-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2003; 3: 721-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li XF, Ma Y, Sun X, Humm JL, Ling CC, O’Donoghue JA. High 18F-FDG uptake in microscopic peritoneal tumors requires physiologic hypoxia. J Nuclear Med 2010; 51: 632-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shen B, Huang T, Sun Y, Jin Z, Li XF. Revisit 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose oncology positron emission tomography:“systems molecular imaging” of glucose metabolism. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 43536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Magaway C, Kim E, Jacinto E. Targeting mTOR and metabolism in cancer: lessons and innovations. Cells 2019; 8: 1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Masui K, Tanaka K, Akhavan D, et al. mTOR complex 2 controls glycolytic metabolism in glioblastoma through FoxO acetylation and upregulation of c-Myc. Cell Metabol 2013; 18: 726-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li Y, He ZC, Liu Q, et al. Large intergenic non-coding RNA-RoR inhibits aerobic glycolysis of glioblastoma cells via Akt pathway. J Cancer 2018; 9: 880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li Y, Patel SP, Roszik J, Qin Y. Hypoxia-driven immunosuppressive metabolites in the tumor microenvironment: new approaches for combinational immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2018; 9: 1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Semenza GL. HIF-1 inhibitors for cancer therapy: from gene expression to drug discovery. Curr Pharm Design 2009; 15: 3839-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cairns R, Papandreou I, Denko N. Overcoming physiologic barriers to cancer treatment by molecularly targeting the tumor microenvironment. Mol Cancer Res 2006; 4: 61-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chiche J, Ilc K, Laferrière J, et al. Hypoxia-inducible carbonic anhydrase IX and XII promote tumor cell growth by counteracting acidosis through the regulation of the intracellular pH. Cancer Res 2009; 69: 358-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guo C, Wanga L, Jianga B, Shia D. Bromophenol curcumin analog BCA-5 exerts an antiangiogenic effect through the HIF-1α/VEGF/Akt signaling pathway in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2018; 29: 965-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yoysungnoen B, Bhattarakosol P, Patumraj S, Changtam C. Effects of tetrahydrocurcumin on hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in cervical cancer cell-induced angiogenesis in nude mice. BioMed Res Int 2015; 2015: 391748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ye MX, Zhao YL, Li Y, et al. Curcumin reverses cis-platin resistance and promotes human lung adenocarcinoma A549/DDP cell apoptosis through HIF-1α and caspase-3 mechanisms. Phytomedicine 2012; 19: 779-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Song X, Liu X, Chi W, et al. Hypoxia-induced resistance to cisplatin and doxorubicin in non-small cell lung cancer is inhibited by silencing of HIF-1alpha gene. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2006; 58: 776-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Birner P, Schindl M, Obermair A, Plank C, Breitenecker G, Oberhuber G. Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha is a marker for an unfavorable prognosis in early-stage invasive cervical cancer. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 4693-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schnitzer SE, Schmid T, Zhou J, Brüne B. Hypoxia and HIF-1alpha protect A549 cells from drug-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 2006; 13: 1611-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dal Piaz F, Braca A, Belisario MA, De Tommasi N. Thioredoxin system modulation by plant and fungal secondary metabolites. Curr Med Chem 2010; 17: 479-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cai W, Zhang B, Duan D, Wu J, Fang J. Curcumin targeting the thioredoxin system elevates oxidative stress in HeLa cells. Toxicol Appl Parmacolo 2012; 262: 341-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ströfer M, Jelkmann W, Depping R. Curcumin decreases survival of Hep3B liver and MCF-7 breast cancer cells: the role of HIF. Strahlenther Onkol 2011; 187: 393-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Contasta I, Berghella AM, Pellegrini P, Adorno D. Passage from normal mucosa to adenoma and colon cancer: alteration of normal sCD30 mechanisms regulating TH1/TH2 cell functions. Cancer Biother Radiopharmaceuticals 2003; 18: 549-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Parodi M, Raggi F, Cangelosi D, et al. Hypoxia modifies the transcriptome of human NK cells, modulates their immunoregulatory profile, and influences NK cell subset migration. Front Immunol 2018; 9: 2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Velásquez SY, Killian D, Schulte J, Sticht C, Thiel M, Lindner HA. Short term hypoxia synergizes with interleukin 15 priming in driving glycolytic gene transcription and supports human natural killer cell activities. J Biol Chem 2016; 291: 12960-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Piñeiro Fernández J, Luddy KA, Harmon C, O’Farrelly C. Hepatic tumor microenvironments and effects on NK cell phenotype and function. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20: 4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Palsson-McDermott EM, Dyck L, Zasłona Z, et al. Pyruvate kinase M2 is required for the expression of the immune checkpoint PD-L1 in immune cells and tumors. Front Immunol 2017; 8: 1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cho SH, Raybuck AL, Stengel K, et al. Germinal centre hypoxia and regulation of antibody qualities by a hypoxia response system. Nature 2016; 537: 234-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Burrows N, Maxwell PH. Hypoxia and B cells. Exp Cell Res 2017; 356: 197-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vishvakarma NK, Kumar A, Singh SM. Role of curcumin-dependent modulation of tumor microenvironment of a murine T cell lymphoma in altered regulation of tumor cell survival. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2011; 252: 298-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sulkowska M, Wincewicz A, Sulkowski S, Koda M, Kanczuga-Koda L. Relations of TGF-beta1 with HIF-1 alpha, GLUT-1 and longer survival of colorectal cancer patients. Pathology 2009; 41: 254-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sarighieh MA, Montazeri V, Shadboorestan A, Ghahremani MH, Ostad SN. The inhibitory effect of curcumin on hypoxia inducer factors (Hifs) as a regulatory factor in the growth of tumor cells in breast cancer stem-like cells. Drug Research 2020; 70: 512-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mao Z, Zhong L, Zhuang X, Liu H, Peng Y. Curcumenol targeting YWHAG inhibits the pentose phosphate pathway and enhances antitumor effects of cisplatin. Evid Based Complem Alternative Med 2022; 2022: 3988916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Epstein J, Sanderson IR, Macdonald TT. Curcumin as a therapeutic agent: the evidence from in vitro, animal and human studies. Br J Nutrition 2010; 103: 1545-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chanvorachote P, Pongrakhananon V, Wannachaiyasit S, Luanpitpong S, Rojanasakul Y, Nimmannit U. Curcumin sensitizes lung cancer cells to cisplatin-induced apoptosis through superoxide anion-mediated Bcl-2 degradation. Cancer Investig 2009; 27: 624-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.De Iuliis F, Salerno G, Taglieri L, et al. Serum biomarkers evaluation to predict chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity in breast cancer patients. Tumour Biology 2016; 37: 3379-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Li L, Braiteh FS, Kurzrock R. Liposome-encapsulated curcumin: in vitro and in vivo effects on proliferation, apoptosis, signaling, and angiogenesis. Cancer 2005; 104: 1322-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cao L, Xiao X, Lei J, Duan W, Ma Q, Li W. Curcumin inhibits hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer cells via suppression of the hedgehog signaling pathway. Oncol Rep 2016; 35: 3728-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pandey A, Vishnoi K, Mahata S, et al. Berberine and curcumin target survivin and STAT3 in gastric cancer cells and synergize actions of standard chemotherapeutic 5-fluorouracil. Nutrition Cancer 2015; 67: 1293-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wu J, Lu WY, Cui LL. Inhibitory effect of curcumin on invasion of skin squamous cell carcinoma A431 cells. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev 2015; 16: 2813-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gandhy SU, Kim K, Larsen L, Rosengren RJ, Safe S. Curcumin and synthetic analogs induce reactive oxygen species and decreases specificity protein (Sp) transcription factors by targeting microRNAs. BMC Cancer 2012; 12: 564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Du Y, Long Q, Zhang L, et al. Curcumin inhibits Cancer-associated fibroblast-driven prostate cancer invasion through MAOA/mTOR/HIF-1α signaling. Int J Oncol 2015; 47: 2064-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang Q, Bai X, Chen W, et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling enhances hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma via crosstalk with hif-1α signaling. Carcinogenesis 2013; 34: 962-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zuo HX, Jin Y, Wang Z, et al. Curcumol inhibits the expression of programmed cell death-ligand 1 through crosstalk between hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and STAT3 (T705) signaling pathways in hepatic cancer. J Ethnopharmacol 2020; 257: 112835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kalashnikova I, Mazar J, Neal CJ, et al. Nanoparticle delivery of curcumin induces cellular hypoxia and ROS-mediated apoptosis: Via modulation of Bcl-2/Bax in human neuroblastoma. Nanoscale 2017; 9: 10375-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lou S, Wang Y, Yu Z, Guan K, Kan Q. Curcumin induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation in infantile hemangioma endothelial cells via downregulation of MCL-1 and HIF-1α. Medicine 2018; 97: e9562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Monteleone F, Taverna S, Alessandro R, Fontana S. SWATH-MS based quantitative proteomics analysis reveals that curcumin alters the metabolic enzyme profile of CML cells by affecting the activity of miR-22/IPO7/HIF-1α axis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2018; 37: 170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wang X, Zhang Y, Yang Y, et al. Curcumin pretreatment protects against hypoxia/reoxgenation injury via improvement of mitochondrial function, destabilization of HIF-1α and activation of Epac1-Akt pathway in rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Biomed Pharmacother 2019; 109: 1268-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lee SS, Tsai CH, Yang SF, Ho YC, Chang YC. Hypoxia inducible factor-1α expression in areca quid chewing-associated oral squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Dis 2010; 16: 696-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ma X, Li C, Sun L, et al. Lin28/let-7 axis regulates aerobic glycolysis and cancer progression via PDK1. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 5212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Obaidi I, Blanco Fernández A, McMorrow T. Curcumin sensitises cancerous kidney cells to TRAIL induced apoptosis via let-7C mediated deregulation of cell cycle proteins and cellular metabolism. Int J Mol Sci 2022; 23: 9569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Azuine MA, Bhide SV. Protective single/combined treatment with betel leaf and turmeric against methyl (acetoxymethyl) nitrosamine-induced hamster oral carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer 1992; 51: 412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ushida J, Sugie S, Kawabata K, et al. Chemopreventive effect of curcumin on N-nitrosomethylbenzylamine-induced esophageal carcinogenesis in rats. Japan J Cancer Res 2000; 91: 893-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ikezaki S, Nishikawa A, Furukawa F, et al. Chemopreventive effects of curcumin on glandular stomach carcinogenesis induced by N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine and sodium chloride in rats. Anticancer Res 2001; 21: 3407-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chuang SE, Cheng AL, Lin JK, Kuo ML. Inhibition by curcumin of diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatic hyperplasia, inflammation, cellular gene products and cell-cycle-related proteins in rats. Food Chem Toxicol 2000; 38: 991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.LoTempio MM, Veena MS, Steele HL, et al. Curcumin suppresses growth of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 6994-7002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hecht SS, Kenney PM, Wang M, et al. Evaluation of butylated hydroxyanisole, myo-inositol, curcumin, esculetin, resveratrol and lycopene as inhibitors of benzo[a]pyrene plus 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-induced lung tumorigenesis in A/J mice. Cancer Letters 1999; 137: 123-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Okazaki Y, Iqbal M, Okada S. Suppressive effects of dietary curcumin on the increased activity of renal ornithine decarboxylase in mice treated with a renal carcinogen, ferric nitrilotriacetate. Biochim Biophys Acta 2005; 1740: 357-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Huang MT, Lou YR, Xie JG, et al. Effect of dietary curcumin and dibenzoylmethane on formation of 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-induced mammary tumors and lymphomas/leukemias in Sencar mice. Carcinogenesis 1998; 19: 1697-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rajitha B, Nagaraju GP, Shaib WL, et al. Novel synthetic curcumin analogs as potent antiangiogenic agents in colorectal cancer. Mol Carcinogen 2017; 56: 288-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wang S, Gao X, Li J, et al. The anticancer effects of curcumin and clinical research progress on its effects on esophageal cancer. Front Pharmacol 2022; 13: 1058070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wu L, Guo L, Liang Y, Liu X, Jiang L, Wang L. Curcumin suppresses stem-like traits of lung cancer cells via inhibiting the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Oncol Rep 2015; 34: 3311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zhao Y, Ma X, Wang J, et al. Curcumin protects against ccl4-induced liver fibrosis in rats by inhibiting HIF-1α through an erk-dependent pathway. Molecules 2014; 19: 18767-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cheng AL, Hsu CH, Lin JK, et al. Phase I clinical trial of curcumin, a chemopreventive agent, in patients with high-risk or pre-malignant lesions. Anticancer Res 2001; 21: 2895-900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kuttan R, Sudheeran PC, Josph CD. Turmeric and curcumin as topical agents in cancer therapy. Tumori 1987; 73: 29-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Dhillon N, Aggarwal BB, Newman RA, et al. Phase II trial of curcumin in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 4491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bayet-Robert M, Kwiatkowski F, Leheurteur M, et al. Phase I dose escalation trial of docetaxel plus curcumin in patients with advanced and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 2010; 9: 8-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Man S, Yao J, Lv P, Liu Y, Yang L, Ma L. Curcumin-enhanced antitumor effects of sorafenib: via regulating the metabolism and tumor microenvironment. Food Function 2020; 11: 6422-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wang X, Shen K, Wang J, et al. Hypoxic preconditioning combined with curcumin promotes cell survival and mitochondrial quality of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, and accelerates cutaneous wound healing via PGC-1α/SIRT3/HIF-1α signaling. Free Radical Biol Med 2020; 159: 164-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Guo W, Ding Y, Pu C, Wang Z, Deng W, Jin X. Curcumin inhibits pancreatic cancer cell proliferation by regulating Beclin1 expression and inhibiting the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α mediated glycolytic pathway. J Gastrointest Oncol 2022; 13: 3254-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Maiti P, Scott J, Sengupta D, Al-Gharaibeh A, Dunbar GL. Curcumin and solid lipid curcumin particles induce autophagy, but inhibit mitophagy and the PI3K-Akt/mTOR pathway in cultured glioblastoma cells. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20: 399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Chatterjee S, Sinha S, Molla S, Hembram KC, Kundu CN. PARP inhibitor Veliparib (ABT-888) enhances the anti-angiogenic potentiality of Curcumin through deregulation of NECTIN-4 in oral cancer: role of nitric oxide (NO). Cell Signal 2021; 80: 109902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]