Abstract

The WRKY proteins comprise a major family of transcription factors that are essential in pathogen and salicylic acid responses of higher plants as well as a variety of plant-specific reactions. They share a DNA binding domain, designated as the WRKY domain, which contains an invariant WRKYGQK sequence and a CX4–5CX22–23HXH zinc binding motif. Herein, we report the NMR solution structure of the C-terminal WRKY domain of the Arabidopsis thaliana WRKY4 protein. The structure consists of a four-stranded β-sheet, with a zinc binding pocket formed by the conserved Cys/His residues located at one end of the β-sheet, revealing a novel zinc and DNA binding structure. The WRKYGQK residues correspond to the most N-terminal β-strand, kinked in the middle of the sequence by the Gly residue, which enables extensive hydrophobic interactions involving the Trp residue and contributes to the structural stability of the β-sheet. Based on a profile of NMR chemical shift perturbations, we propose that the same strand enters the DNA groove and forms contacts with the DNA bases.

INTRODUCTION

The WRKY proteins, which have been identified from a wide range of higher plants (Ishiguro and Nakamura, 1994; Rushton et al., 1995, 1996; de Pater et al., 1996), comprise a large family of plant-specific transcription factors (Eulgem et al., 2000; Riechmann et al., 2000). Most of the WRKY proteins are involved in responses to bacterial or fungal pathogens and a pathogen-related hormone, salicylic acid (Rushton et al., 1996; Eulgem et al., 1999; Chen and Chen, 2000; Du and Chen, 2000). Typically, they mediate signaling triggered by the elicitor molecule encoded by the pathogen and induce rapid apoptosis of cells so as to prevent further invasion. An increasing number of recent reports have indicated that the WRKY proteins are also involved in a variety of other plant-specific reactions, such as senescence (Robatzek and Somssich, 2001), morphogenesis (Johnson et al., 2002), and cold tolerance (Huang and Duman, 2002) and responses to wounding (Hara et al., 2000), drought (Pnueli et al., 2002; Rizhsky et al., 2002; Seki et al., 2002a), heat shock (Rizhsky et al., 2002), high salinity (Seki et al., 2002a), UV radiation (Izaguirre et al., 2003), sugar (Sun et al., 2003), and gibberellin (Zhang et al., 2004). The WRKY proteins are known to mediate signaling through binding to the promoter regions of target genes containing the W-box sequence, (T)TTGACY, where Y is C or T (de Pater et al., 1996; Rushton et al., 1996; Eulgem et al., 1999).

The WRKY proteins share a DNA binding domain of ∼60 amino acids in length, which contains an invariant WRKYGQK sequence (after which the domain was named; Rushton et al., 1996) and a CX4–5CX22–23HXH (or CX7CX23HXC in a minority of cases) zinc binding motif. It is known that DNA binding in vitro is abolished by divalent metal chelators (Rushton et al., 1995; de Pater et al., 1996; Hara et al., 2000) and restored by the addition of Zn2+ (Maeo et al., 2001). A mutational experiment revealed that the conserved Cys and His residues in the motif are involved in this zinc-dependent DNA binding activity and that the invariant WRKYGQK sequence is required for DNA binding (Maeo et al., 2001). Many of the WRKY proteins possess two WRKY domains, which are classified into group I, whereas those possessing a single WRKY domain are classified into group II or III. Group III WRKY proteins are typified mainly by having the less common CX7CX23HXC zinc binding motif (Eulgem et al., 2000). It has been shown for Arabidopsis thaliana, parsley (Petroselinum crispum), and sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) group I WRKY proteins that the C-terminal WRKY domain, but not the N-terminal domain, is responsible for sequence-specific binding to DNA (Ishiguro and Nakamura, 1994; de Pater et al., 1996; Eulgem et al., 1999).

In this study, the three-dimensional structure of the C-terminal WRKY domain of the Arabidopsis WRKY4 protein (WRKY4-C) was determined by NMR spectroscopy. Circular dichroism (CD) and NMR experiments provided evidence for the zinc-dependent folding of the structure. The structure consists of a four-stranded β-sheet with a zinc binding pocket formed at one end and represents a novel type of zinc and DNA binding domain, although it shows partial similarity to other larger proteins. A DNA titration experiment strongly suggested that the region corresponding to the conserved sequence WRKYGQK is directly involved in DNA binding, which enabled us to propose a structural framework for the DNA recognition mechanism.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

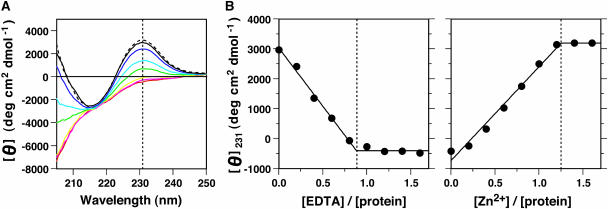

Zinc-Dependent Folding of WRKY4-C

The protein was expressed and purified in the presence of Zn2+ ions because the WRKY proteins are known to bind zinc. The addition of EDTA to the purified WRKY4-C protein caused a large structural change as observed by CD measurements in the far-UV region (Figure 1A). A titration profile indicated that the change appears complete at an approximately 1:1 molar ratio of EDTA to protein (Figure 1B), revealing that Zn2+ ions were released in equimolar amounts to the protein concentration. The initial spectrum before the EDTA titration (Figure 1A) is characteristic of a β-sheet, with a small negative peak at 210 to 220 nm (Woody, 1995). Conversely, the final spectrum after the titration (Figure 1A) is more consistent with the spectrum of an unfolded peptide, with a large negative peak at ∼200 nm (Woody, 1995). Thus, it was shown that EDTA induced unfolding of the WRKY4-C protein by chelating the Zn2+ ion. NMR spectra showed more clearly that the protein in a solution without EDTA possesses a specific tertiary structure, whereas the protein in a solution containing EDTA loses its large chemical shift dispersion, an indication of being largely unfolded (see supplemental data online). Adding Zn2+ ions to the solution of the unfolded protein induced refolding to the native structure as judged by the nearly identical CD spectra (Figure 1A). The titration profile showed complete refolding of the protein at an approximate 1:1 molar ratio of Zn2+ ions to the protein (Figure 1B). These results indicate that binding of a single Zn2+ ion to a WRKY4-C molecule causes the formation of a specific tertiary structure. This is likely to account for the requirement of Zn2+ for DNA binding activity (Rushton et al., 1995; de Pater et al., 1996; Hara et al., 2000; Maeo et al., 2001). These observations are also consistent with the results of mutations of the conserved Cys and His residues, all of which abolished the DNA binding activity (Maeo et al., 2001).

Figure 1.

Zinc-Dependent Structural Formation of WRKY4-C.

(A) CD spectra of WRKY4-C in the absence (black) or presence of 0.2 (blue), 0.4 (cyan), 0.6 (green), 0.8 (yellow), 1.0 (magenta), and 1.2 (red) times molar concentrations of EDTA and after the back-titration of ZnCl2 (dashed line).

(B) The change in the CD value during the titration of EDTA and the back-titration of ZnCl2 was monitored at 231 nm, the position of which is marked by a dotted vertical line in (A). Solid lines in (B) indicate linear changes in the ellipticity up to saturation values, which were obtained by nonlinear least-squares fitting. The points of saturation are shown by dotted vertical lines.

Structural Description

The experimental constraints and stereochemical properties of the NMR solution structure of WRKY4-C are shown in Table 1. The secondary structure elements are four β-strands (β1, Trp414–Lys420; β2, Pro428–Thr436; β3, Cys439–Ala448; β4, Ala454–Glu460) forming an antiparallel β-sheet, as defined by the program Procheck-NMR (Laskowski et al., 1996) (Figures 2 and 3). The β1 strand is largely kinked in the middle at the position of Gly418 of the invariant WRKYGQK sequence because the residues on either side (Tyr417 and Gln419) form contacts with two adjacent residues of strand β2 (Tyr431 and Ser430, respectively) in the antiparallel β-strand connection. Specifically, Trp414, Arg415, Lys416, Tyr417, Gln419, and Lys420 of strand β1 are adjacently connected to Cys434, Lys433, Tyr432, Tyr431, Ser430, and Arg429, respectively, of strand β2 by the formation of interstrand hydrogen bonds or the close proximity of α-protons, leaving Gly418 with no connecting partner.

Table 1.

Structural Statistics

| Structural Constraints | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sequential NOEs | 331 | |

| Medium-range NOEs (2 ≤ |i-j| ≤ 4) | 91 | |

| Long-range NOEs (|i-j| > 4) | 353 | |

| Hydrogen bonds | 38 | |

| Torsion (φ) angles | 49 | |

| Torsion (χ1) angles | 28 | |

| Theoreticala | 14 | |

| Total | 904 | |

| Characteristics | Ensemble of 20 Structures | Minimized Mean Structure |

| The rms deviation from constraints | ||

| NOEs and hydrogen bonds (Å) | 0.001 ± 0.0004 | 0.001 |

| Torsion angles (°) | 0.013 ± 0.009 | 0.007 |

| van der Waals energy (kcal/mol)b | 14.6 ± 0.2 | 14.600 |

| The rms deviation from the ideal geometry | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.0008 ± 0.00002 | 0.0007 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.279 ± 0.001 | 0.2760 |

| Improper angles (°) | 0.094 ± 0.002 | 0.0840 |

| Average rms deviation from the unminimized mean structure (Å)c | ||

| N, Cα, C | 0.48 ± 0.08 | |

| All heavy atoms | 0.95 ± 0.09 | |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Most favored region (%) | 76.5 | 75.9 |

| Additionally allowed region (%) | 22.4 | 24.1 |

| Generously allowed region (%) | 1.1 | 0.0 |

| Disallowed region (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Distance, angle, and plane restraints applied for Zn2+ ions and coordinating atoms (see Methods).

Values calculated with the force field for NMR structure determination in the CNS package.

Values calculated with Tyr412–Val422, Asn425–Asp451, and Lys453–His465.

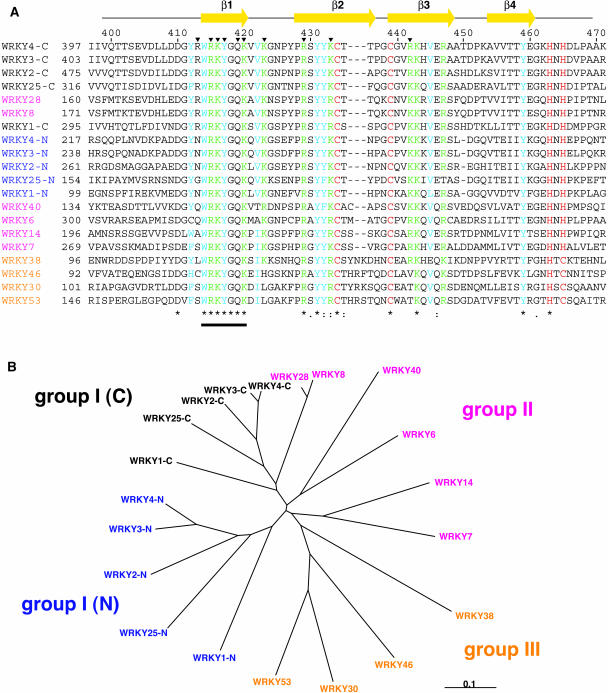

Figure 2.

Comparison of Primary Sequences of Arabidopsis WRKY Domains.

(A) Sequence alignment of the WRKY domains of Arabidopsis produced by the ClustalX program (Thompson et al., 1997). Sequences were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Entry codes are AAM15341 (WRKY1), AAL13039 (WRKY2), AAK28311 (WRKY3), AAL13048 (WRKY4), AAK01127 (WRKY6), AAK28440 (WRKY7), AAK96193 (WRKY8), AAL11007 (WRKY14), AAL13040 (WRKY25), AAL35286 (WRKY28), AAK96196 (WRKY30), AAL35288 (WRKY38), AAL85879 (WRKY40), AAK96020 (WRKY46), and AAK28442 (WRKY53). For the group I WRKY proteins (WRKY1 to 4, and 25; Eulgem et al., 2000), each possessing two WRKY domains, both the N- and C-terminal domains are used in the alignment. Numbers above the sequences are for WRKY4-C, and those of the first residues of the aligned sequences of the individual proteins are indicated beside the sequences. Domain names are colored according to the classification (i.e., black for group I C-terminal domains, blue for group I N-terminal domains, magenta for group II, and orange for group III). The zinc-coordinating residues (Cys or His) are colored red, basic (Arg and Lys) residues conserved in 17 or more of the 20 domains presented here are colored green, and aliphatic (Ile, Leu, Met, and Val) or aromatic (His, Phe, Trp, and Tyr) residues conserved in 17 or more domains are colored cyan. Yellow arrows above the sequence alignment indicate the regions of the β-strands of WRKY4-C. Arrowheads indicate the residues that directly contact to DNA in the proposed model (see text). Below the sequence, identical and similar residues are marked as produced by the program ClustalX. The location of the invariant WRKYGQK sequence is indicated by a horizontal bar.

(B) The phylogenetic tree for the above alignment. The domain names are colored according to the classification as in (A). The scale bar indicates the distance corresponding to 0.1 amino acid substitutions per site.

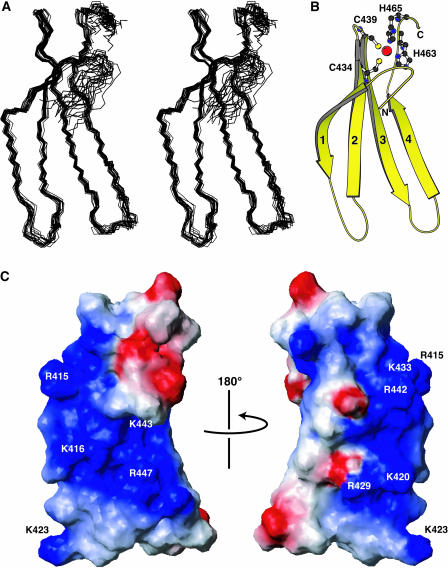

Figure 3.

Solution Structure of WRKY4-C.

The ensemble of the selected structures in stereo view (A), a ribbon diagram of the minimized mean structure (B), and the contact surface with the presentation of electrostatic polarization (C) (blue, positive; red, negative). In (C), the four β-strands are numbered from the N terminus, and the Zn2+ ion and zinc-coordinating residues are shown by a red sphere and ball-and-stick representations, respectively. The conserved basic residues are indicated in (C). The presented region is Leu407–Ala469, excluding the N-terminal region with little amino acid conservation. The figure was produced by the programs Molscript (Kraulis, 1991) and MOLMOL (Koradi et al., 1996).

At one of the ends of the β-sheet, a zinc binding pocket is formed by the conserved Cys/His residues, Cys434, Cys439, His463, and His465 (Figures 2 and 3). Thirteen nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs; NMR distance information) were observed between these residues, which allowed the pocket to be accounted for in the structural calculation by the distance and dihedral angle experimental constraints alone. However, to regularize the tetrahedral coordination geometry around the zinc ion, theoretical constraints were included in the structural calculation (see Methods), which affected the structure only slightly. It was shown that the Nδ atom of His463 and the Hɛ atom of His465 coordinate to the Zn2+ ion, and significant violations were observed when the structure was calculated with theoretical constraints based on alternative assumptions (data not shown).

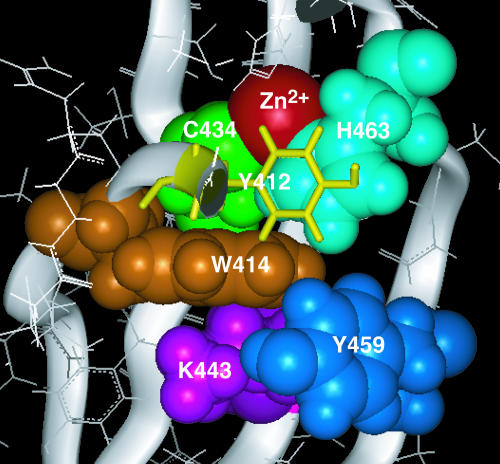

Extensive hydrophobic interactions were observed between Tyr412–His463, Trp414–Cys434, Trp414–Lys443, Trp414–Tyr459, Tyr417–Tyr431, Val422–Asn425, Tyr427–Arg447, Tyr432–Lys443, Lys433–Arg442, and Thr436–His465, which were determined by more than three pairs of side-chain carbon atoms having average distances of <4.5 Å over the 20 structures of the ensemble [e.g., between Tyr412 and His463, 15 carbon atom pairs, such as CB(Tyr412)–CE1(His463), CG(Tyr412)–CE1(His463), CD1(Tyr412)–CD2(His463), CD1(Tyr412)–CE1(His463), and CE1(Tyr412)–CG (His463), have distances <4.5 Å on average]. Most of these residues are the aromatic (Tyr412, Trp414, Tyr431, Tyr432, Tyr459, and His465), aliphatic (Val422), or basic (Lys433, Arg442, Lys443, and Arg447) residues that are highly conserved among the WRKY domains (Figure 2A), indicating that these domains share a common structural architecture. The numerous basic residues involved in the hydrophobic interactions are likely to be suitable for maintaining a single β-sheet structure. That is, the basic residues possess long hydrophobic side chains with hydrophilic ends, which facilitate hydrophobic packing between residues oriented in similar directions while allowing the hydrophilic ends to be exposed to the solvent. The observation that many Tyr residues, which possess hydrophilic ends, but no Phe residues, which do not, are involved in hydrophobic interactions in WRKY4-C is also consistent with this premise.

It is of particular interest that the bulky side chain of Trp414 of the invariant WRKYGQK sequence, located on strand β1, has extensive contacts to Cys434 of β2, Lys443 of β3, and Tyr459 of β4 (Figure 4), as listed above. Therefore, Trp414 appears to be of particular importance in stabilizing the structure of the four-stranded β-sheet. It also makes hydrophobic contacts to the side chains of Tyr412 and His463 (two and three carbon atom pairs with average distances of <4.5 Å were identified for Trp414–Tyr412 and Trp414–His463, respectively). Thus, among the residues contacting Trp414, two (Cys434 and His463) are the Zn2+ coordinating residues. Therefore, Trp414, together with Tyr412, which makes extensive hydrophobic contacts to His463 as described above, is likely to be important in stabilizing the Zn2+ coordination and thereby forming the structural core of the domain (Figure 4). The prominent contribution of Trp414 in stabilizing the structure is enabled by the kink in strand β1 located at the position of Gly418. As described above, Tyr417 of the WRKYGQK sequence also makes extensive hydrophobic contacts to Tyr431, which likely stabilizes the β-sheet on the opposite side of Trp414.

Figure 4.

Structural Core of WRKY4-C.

Trp414 (orange), Cys434 (green), Lys443 (magenta), Tyr459 (blue), His463 (cyan), and Zn2+ ion (red) are shown in the CPK representation, whereas Tyr412 (yellow) is shown in the stick representation so as not to conceal other residues. The backbone is shown in the ribbon representation. The figure was produced by the Insight II molecular display program (Accelrys, San Diego, CA).

DNA Recognition by WRKY4-C

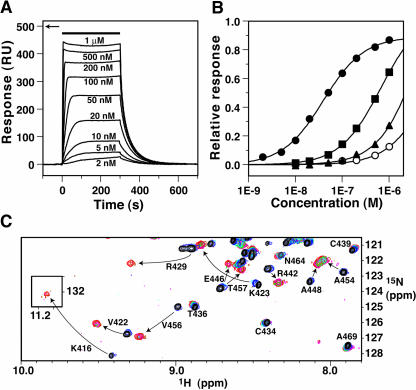

The W-box consensus sequence (T)TTGACY is known to be recognized by WRKY domains (de Pater et al., 1996; Rushton et al., 1996; Eulgem et al., 1999). Using surface plasmon resonance, WRKY4-C was demonstrated to bind to double-stranded DNA containing this consensus sequence (Figures 5A and 5B), with a binding constant of 2.6 × 107 M−1 at low ionic strength (100 mM KCl). Binding was sensitive to the ionic strength and became weaker at higher salt concentrations (Figure 5B). The response ratio of maximal binding of the protein to DNA immobilized on the sensor chip suggested that WRKY4-C binds to DNA with a stoichiometry of 1:1 (Figures 5A and 5B). Nonspecific binding to DNA with an unrelated sequence was also observed, although the binding was much weaker (Figure 5B). Thus, the recognition specificity to the W-box sequence was observed for the domain used in this study.

Figure 5.

DNA Binding of WRKY4-C Observed by Surface Plasmon Resonance and NMR.

(A) Surface plasmon resonance difference sensorgrams (the responses in the control flow cell were subtracted) for binding of WRKY4-C to a double-stranded 16mer DNA (5′-CGCCTTTGACCAGCGC-3′/5′-GCGCTGGTCAAAGGCG-3′; the W-box consensus sequence is underlined), where the protein concentrations are 2 nM to 1 μM, as indicated beside the sensorgrams. The solution is at a KCl concentration of 100 mM. The protein solutions were injected during the period indicated by the horizontal bar. The arrow indicates the maximum response value expected when the protein molecules bind to all the immobilized DNA molecules with a 1:1 stoichiometry.

(B) Equilibrium response values relative to the expected maximum values at a 1:1 stoichiometry, as a function of the protein concentration. The binding profiles of WRKY4-C to the double-stranded 16mer DNA (as above) (closed symbols) or to a 25mer DNA with an unrelated sequence (5′-TCTTTAATTTCTAATATATTTAGAA-3′/5′-TTCTAAATATATTAGAAATTAAAGA-3′) (open symbols) are shown. The KCl concentration was 100 (circles), 200 (squares), or 300 (triangles) mM. Fitting curves to the simple 1:1 binding model are shown.

(C) An overlay of a selected region of 1H-15N HSQC spectra of WRKY4-C in the absence (black) or the presence of 0.25 (blue), 0.5 (cyan), 0.75 (green), 1.0 (magenta), 1.25 (brown), and 1.5 (red) times molar concentrations of the 16mer DNA. The final spectrum shown in red was recorded at approximately three times the larger number of scans than the others. The inlet is for an isolated downfield region where the Lys416 cross-peak of the protein–DNA complex appears. Spectra were recorded at the proton frequency of 750 MHz.

The regions of a protein surface responsible for binding to DNA tend to be positively charged, simply because the DNA is negatively charged. It is apparent that a large continuous area of the WRKY4-C surface is positively charged, which includes all of the nine conserved basic residues (Figure 3C). Some of these conserved basic residues, Lys433, Arg442, Lys443, and Arg447, are also important in hydrophobic interactions as described above, although this does not exclude the possibility of their involvement in DNA binding.

An NMR titration experiment was performed to elucidate the protein–DNA interface (Figure 5C). By adding increasing amounts of DNA, chemical-shift perturbations were observed in heteronuclear single-quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra. The positions of some HSQC cross-peaks changed only slightly or not at all, such that the chemical-shift changes were easy to follow (e.g., Cys434, Thr436, Cys439, Asn464, and Ala469 in Figure 5C). For others, however, the differences were significant enough that the changes could not be followed, in which case analysis of three-dimensional spectra of the protein–DNA complex was necessary for their assignment (e.g., Lys416, Val422, Lys423, Arg429, Arg442, Glu446, Ala448, Ala454, Val456, and Thr457 in Figure 3C). It should be noted that the HSQC cross-peak of Lys416 of the WRKYGQK sequence is extremely downfield shifted, a possible reason for which will be discussed later. These chemical shift changes were completed when the concentration ratio of DNA to protein reached ∼1.0, which indicated a 1:1 binding stoichiometry of the protein–DNA complex.

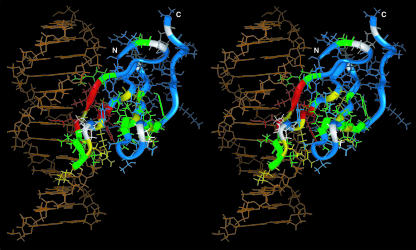

By classifying the residues according to their chemical shift differences, it became clear that one side of the structure is largely affected by the binding of DNA (Figure 6). Based on this result, we built a structural model of the complex of WRKY4-C and standard B-DNA using a computational approach (Figure 6). In this model, β-strand 1 consisting of the invariant WRKYGQK sequence residues deeply enters the major groove of the DNA in such a way that the β-sheet plane is nearly perpendicular to the DNA axis. Accordingly, the side chains of Arg415, Lys416, Gln419, and Lys420, which are likely the most important residues in the sequence-specific recognition, contact the bases. The backbone atoms of Tyr417 also contact the bases. The basic side chains of Arg413, Lys423, Arg429, and Arg442 and the backbone amide of Lys416 form intermolecular hydrogen bonds to the DNA phosphate groups. The hydrogen bond formation by the Lys416 backbone amide is consistent with the extreme downfield shift of its NMR cross-peak (Figure 5C). In addition, the side chain of Lys433 is at a distance from a DNA phosphate group that would allow the formation of a salt bridge or an indirect hydrogen bond through a water molecule.

Figure 6.

A Predicted Model of the Complex of WRKY4-C (Ribbon and Wire of Different Colors Described Below) and a Standard B-DNA Molecule (Orange Wire) in Stereo View.

Amino acid residues with backbone chemical shifts affected by the DNA binding are colored red [(ΔδH2+ ΔδN2)1/2 ≥ 400 Hz at the proton frequency of 750 MHz: residues 416, 417, 419, 430, and 431], yellow [(ΔδH2+ ΔδN2)1/2 ≥ 200 Hz: residues 418, 423, 425, 429, 433, 443, and 456], or green [(ΔδH2+ ΔδN2)1/2 ≥ 100 Hz: residues 409, 415, 420–422, 424, 440, 444 to 447, 454, 455, and 457 to 459], and those only slightly affected [(ΔδH2+ ΔδN2)1/2 < 100 Hz: residues 407, 408, 411 to 414, 427, 432, 434 to 436, 438, 439, 441, 442, 448 to 451, 453, 460 to 467, and 469] are shown in blue. Residues with no meaningful information (i.e., those with unassigned or unobserved backbone resonances) or Pro residues (residues 410, 426, 428, 437, 452, and 468) are shown in white. Residues 407 to 469 are presented, and the excluded residues 399 to 406 are affected only slightly by the addition of the DNA. The figure was produced by Insight II (Accelrys).

In this proposed model, the β-strand containing the WRKYGQK motif makes contacts with an ∼6-bp region, which is largely consistent with the length of the (T)TTGACY W-box consensus (de Pater et al., 1996; Rushton et al., 1996; Eulgem et al., 1999). The concave curvature of strand β1 induced by the kink at Gly418 allows the deep entrance of this strand into the DNA groove. Thereby, the three basic residues and the Gln residue of the motif are able to make contacts with the DNA bases, even though the neighboring residues, namely Arg415 and Lys416 or Gln419 and Lys420, are pointing toward the opposite sides of the sheet.

The involvement of the WRKYGQK sequence in DNA binding was demonstrated by a mutational experiment (Maeo et al., 2001). In this experiment, the Trp, Tyr, and two Lys residues were shown to be indispensable for DNA binding. This is consistent with our proposed model, wherein the two Lys residues contact the DNA bases directly. In addition, the Trp and Tyr residues are likely to be necessary for the structural architecture required for DNA binding, as discussed above. In contrast with our proposed model, the results of Maeo et al. (2001) also showed that DNA binding activity was not significantly affected by mutation of the Arg or Gln residues of the sequence, and, although significantly reduced, was not abolished by the mutation of the Gly residue. Our results suggested the involvement of these residues in DNA binding, whether directly or indirectly through forming the structural architecture. The reason for this inconsistency (or partial consistency) and details of the mechanism of sequence-specific DNA recognition by the WRKY domains await a structural determination of the protein complexed with DNA.

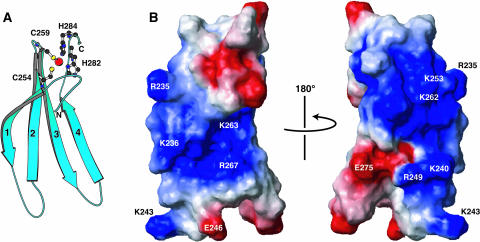

Different WRKY Domains

It is known that the C-terminal domain of group I WRKY proteins, but not the N-terminal domain, is responsible for DNA binding (Ishiguro and Nakamura, 1994; de Pater et al., 1996; Eulgem et al., 1999). We investigated the structural basis for this observation by producing a computational model of the WRKY4-N structure based on its sequence homology to WRKY4-C (Figure 7). We also modeled the WRKY4-N/DNA complex, based on the proposed model of the WRKY4-C/DNA shown in Figure 6. The modeled WRKY4-N structure is very similar to WRKY4-C and is energetically favored, which confirms that the structural architecture is shared by the different WRKY domains (Figure 7A). The energy gain upon forming the protein–DNA complex was approximately −200 kcal mol−1 for WRKY4-N, whereas it was approximately −300 kcal mol−1 for WRKY4-C, as estimated with implicit solvent effects in the AMBER force field (Case et al., 2002). This suggests that both domains are capable of DNA binding, although WRKY4-C binds more strongly. The difference in the energy gain of ∼100 kcal mol−1 is mostly due to differences in electrostatic energies. The surface potential of WRKY4-N (Figure 7B) showed that the domain is still basic, with similar locations of the conserved basic residues to those in WRKY4-C (Figure 3C). However, two conserved acidic residues in the N-terminal WRKY domains, Glu246 and Glu275, are in the equivalent positions to the neutral residues Pro426 and Val456, respectively, of WRKY4-C (Figure 2A) and reduce the basicity of WRKY4-N (Figure 7B). Indeed, the numbers of basic and acidic residues are 12 and 6, respectively, for WRKY4-C, whereas they are 11 and 7, respectively, for WRKY4-N, resulting in the net charges of +6 for WRKY4-C and +4 for WRKY4-N. In addition, Arg413 of WRKY4-C, the side chain of which is positively charged and contacts a DNA phosphate group in the proposed model, is conserved in the C-terminal WRKY domains but not in the N-terminal domains (Figure 2A). These distinctions are likely to be responsible for the predicted differences in the electrostatic energy gain for each domain upon formation of the complex. A more accurate comparison of free energies, including an evaluation of the entropic effects, will require an extensive dynamical calculation encompassing the surrounding water molecules.

Figure 7.

A Structural Model of WRKY4-N.

The ribbon diagram (A) and the contact surfaces with the presentation of the electrostatic polarization (B) (blue, positive; red, negative) are shown, where the orientation is the same as in Figure 3. Positions of the conserved basic residues equivalent to those in Figure 3, as well as the acidic residues conserved only in the N-terminal WRKY domains (see text), are marked on the surface. The presented region is Pro227–Gln288, which is equivalent to Leu407–Ala469 of WRKY4-C shown in Figure 3.

For five group I WRKY proteins shown in Figure 2, the phylogenetic relationships of the N-terminal domains are essentially the same as those of the C-terminal domains (Figure 2B), indicating that they evolved as proteins possessing two WRKY domains. The group II WRKY domains are more divergent in their primary sequences. In fact, the WRKY domains of WRKY8 and WRKY28 lie on a branch of the group I C-terminal WRKY domains (Figure 2B), emphasizing their evolutionary relatedness. Arg413 of WRKY4-C, which is likely to be important in DNA binding as discussed above, is conserved in the two WRKY domains, but not in the other group II WRKY domains (Figure 2). From the above phylogenetic relationship and structural point of view, we propose that WRKY8, WRKY28, and related WRKY proteins (group IIc in Eulgem et al., 2000) are more appropriately classified into group I, even though they possess a single WRKY domain.

Arg413 of WRKY4-C also is not conserved in the group III WRKY domains (Figure 1). In addition, two other important basic residues in WRKY4-C, Lys423 and Arg442, are not conserved in three group III WRKY domains: WRKY30, WRKY46, and WRKY53 (Figure 2A). It has been reported that similar group III WRKY proteins from tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) are capable of binding to the W-box DNA sequence (Chen and Chen, 2000). Interestingly, for the three group III WRKY domains, basic residues are instead conserved in two different positions, namely, Pro426 and the gap between Thr435 and Thr436 in WRKY4-C (Figure 2A). By examining the proposed model, we suggest that the long side chains of the basic residues in these positions are capable of contacting DNA phosphate groups without a large change in the DNA binding mode proposed in Figure 6. Therefore, these group III WRKY proteins are likely to possess essentially the same DNA binding mode as the group I C-terminal WRKY domains, although this is accomplished at least partly through different residues.

Similarity to Other Structures

The Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/) was searched for structures similar to that of WRKY4-C using the program DALI (Holm and Sander, 1993). Structures with high similarity scores (Z-scores >4.0) were those of β-galactosidase (PDB code 1bgl; Z-score 4.6), ferric hydroxamate uptake protein (PDB code 1by5; Z-score 4.2), and clathrin fragment (PDB code 1bpo; Z-score 4.2), which are much larger (500 to 1000 amino acids) than WRKY4-C and possess antiparallel β-sheets of four strands or more as inseparable parts of their large structural architectures (data not shown). This is also essentially true for another 27 partially similar structures with Z-scores >3.0. These partly similar structures do not bind to zinc or DNA, and so it is evident that WRKY4-C possesses a novel type of zinc and DNA binding structure.

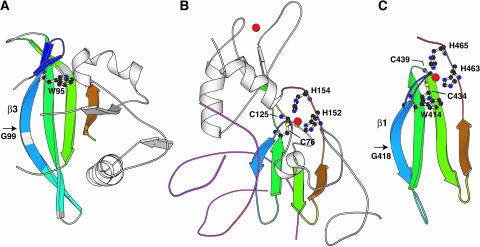

We found two DNA binding domain structures of marginal similarity to WRKY4-C, Arabidopsis NAC (no apical meristem) (PDB code 1ut4; Ernst et al., 2004) (Z-score 2.6) and Drosophila GCM (glia cell missing) (PDB code 1odh; Cohen et al., 2003) (Z-score 2.2), which are transcription factors that have functional similarities to WRKY4-C (Figure 8). Like other partly similar structures, they are significantly larger than WRKY4-C and possess antiparallel β-sheets of four strands or more as substructures. The NAC structure possesses a six-stranded antiparallel β-sheet in which the central four strands were aligned to the four-stranded β-sheet of WRKY4-C using the DALI program (in addition, a short strand of the NAC structure was aligned to a loop region of WRKY4-C) (Figure 8A). It is important to note that β-strand 3 of NAC, corresponding to β1 of WRKY4-C, possesses a curvature forming a concave surface, which is induced by the presence of a Gly residue (shown by an arrow in Figure 8A) and one more residue at its C terminus. The indole ring of a Trp residue, located four residues to the N-terminal side of the Gly residue, is oriented inside of the β-sheet (Figure 8A) and forms extensive hydrophobic interactions. These characteristics are very similar to β-strand 1 of WRKY4-C (Figure 8C) as described above. In β-strand 3 of NAC, a WKATGXD[K/R] sequence is conserved, which appears to be partially similar to the WRKYGQK motif in β-strand 1 of WRKY4-C. In addition, an area of the molecular surface including the side of β-strand 3 is positively charged and was suggested to be involved in DNA binding (Ernst et al., 2004). Therefore, we propose that the structures of these two plant-specific transcription factor DNA binding domains are related not only in their secondary structure arrangement, but also in the DNA binding mode.

Figure 8.

Structural Similarities of the Arabidopsis NAC Domain and Drosophila GCM Domain to WRKY4-C.

(A) Arabidopsis NAC domain.

(B) Drosophila GCM domain.

(C) WRKY4-C.

The NAC domain exists in a dimeric form, from which a monomer is presented in (A). Residues of interest (see text) are shown in the ball-and-stick representation or indicated by arrows. Zinc ions are represented by red spheres. The two DNA strands bound by the GCM domain are shown by loops colored magenta (B). The structures are oriented similarly as aligned by the DALI program (Holm and Sander, 1993), where the aligned segments in (A) and (B) are shown in the same colors used for the corresponding residues of WRKY4-C (C). The figure was produced by Molscript (Kraulis, 1991).

The structure of the GCM DNA binding domain was determined in complex with DNA (Cohen et al., 2003) (Figure 8B). This structure possesses a small four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet, which was aligned to the WRKY4-C β-sheet using the DALI program. Most importantly, the strand corresponding to β-strand 1 of WRKY4-C deeply enters the major groove of the DNA in a similar manner proposed for the WRKY/DNA complex (Figure 6). In addition, one of the two zinc ions is coordinated by two Cys and two His residues located in very similar positions to those of the zinc-coordinating Cys and His residues of WRKY4-C (Figures 8B and 8C). Specifically, Cys76 of the GCM domain is located on the β-strand that was aligned to β2 of WRKY4-C where Cys434 is located. Cys125 of the GCM domain is located at a loop N-terminal to the β-strand that was aligned to β3 of WRKY4-C, at the N terminus of which Cys439 is located. Similarly, the positions of the two His residues, His152 and His154, appear to be equivalent to those of His463 and His465 of WRKY4-C. Furthermore, the two domains are common in that the Nδ atom is used for the zinc coordination in the N-terminal His residues, His152 of the GCM domain and His463 of WRKY4-C, whereas the Nɛ atom is used in the C-terminal His residues. Therefore, we suggest that they share a common zinc binding structural motif, although their sequence motifs are different because a subdomain containing another zinc binding site is inserted between Cys76 and Cys125 of the GCM domain.

Plant-Specific Transcription Factors

Despite the structural and functional similarities, no significant sequence similarities were observed for the DNA binding domains of the NAC, GCM, and WRKY proteins. However, considering the high degree of similarity in the Zn binding modes and, likely, DNA binding modes of the GCM and WRKY domains, we suggest the possibility of an evolutionary relationship between these domains. Considering that group I WRKY proteins have been identified recently in primitive eukaryotes, such as a slime mold (Dictyostelium discoideum) and a protist (Giardia lamblia) (Ülker and Somssich, 2004), and that GCM domains so far have been identified only in animals such as insects, fish, and mammals (Cohen et al., 2003), the WRKY domain might be more ancestral than the GCM domain.

It was reported that AtERF1 of the plant-specific AP2/ERF family and Tn916 integrase, a bacterial endonuclease, share a similar DNA binding mode through a three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (Allen et al., 1998; Wojciak et al., 1999). Recently, putative endonucleases from bacteria, phages, and a protist possessing DNA binding domains homologous to the plant AP2/ERF domains were reported (Magnani et al., 2004). In addition, the B3 DNA binding domain of the plant-specific transcription factor RAV1 is similar to that of a bacterial restriction enzyme EcoRII in the three-dimensional structure, DNA binding mechanism, and primary sequence (Yamasaki et al., 2004b). Therefore, it is possible that structural frameworks of the DNA binding domains of many plant-specific transcription factors were established before the plant kingdom was isolated from the other eukaryotic kingdoms, after which they gained their specific functions and drastically increased in number, along with the evolution of plant-specific reactions in development and environmental responses.

METHODS

Sample Preparation

The DNA that encodes for WRKY4-C (Val399–Ala469) was subcloned into the pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) by PCR from an Arabidopsis thaliana full-length cDNA clone (Seki et al., 2002b) with the ID code RAFL03-05-E03 (MIPS code: At1g13960). The PCR primers used were designed so that the T7 promoter sequence, ribosome binding site, and oligohistidine tag, as well as the cleavage site for tobacco etch virus protease, are attached at the 5′ end and so that the T7 terminator sequence is attached at the 3′ end (T. Yabuki, Y. Motoda, M. Saito, N. Matsuda, T. Kigawa, and S. Yokoyama, unpublished results). Consequently, additional amino acids (i.e., GlySerSerGlySerSerGly) derived from the expression vector were attached to the N terminus of the protein. The 13C-, 15N-labeled, and unlabeled proteins were expressed by a large-scale cell-free system developed at RIKEN (Tokyo, Japan) (Kigawa et al., 1999, 2004; Yokoyama et al., 2000). The protein was purified by TALON (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), HiPrep 26/10 Desalting (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ), and HiTrap SP (Amersham) column chromatography. The buffers used were as follows: 20 mM Tricine-NaOH, pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, and 5 μM ZnCl2 for sample loading and washing of the TALON column, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, and 5 μM ZnCl2 for protein elution from the TALON column, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 5 μM EDTA, and 10 μM ZnCl2 for HiPrep 26/10 Desalting chromatography, and 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 1 mM DTT, 5 μM EDTA, 10 μM ZnCl2, and 0 to 1 M NaCl for HiTrap SP chromatography. Protein concentration was determined by A280 values with the molar absorption coefficient calculated from the amino acid sequence (Pace et al., 1995). For NMR measurements, proteins of ∼1.0 mM were dissolved in 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, containing 300 mM KCl, 20 μM ZnCl2, 1 mM deuteriated DTT (Isotec, Miamisburg, OH), 0.5 mM sodium 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate (DSS), and 5% D2O, unless otherwise stated. For CD titration experiments, protein of an initial concentration of 50 μM was dissolved in 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, containing 300 mM KCl, and 1 mM DTT.

CD Measurements

CD spectra were recorded on a JASCO J-820 spectropolarimeter (Tokyo, Japan) using a 1-mm path-length cell. Spectra between 195 and 250 nm were obtained using a scanning speed of 20 nm min−1, a response time of 2.0 s, a bandwidth of 1 nm, a spectral resolution of 0.5 nm, and four-scan averaging. Temperature was controlled at 298 K by a Peltier cooling system. Titration experiments were conducted by adding increasing amounts of 1 mM EDTA or 1 mM ZnCl2. Using a nonlinear least-squares method, the obtained titration data were fitted to linear lines with saturation values, assuming that the binding of the Zn2+ ion to the protein was extremely strong.

NMR Measurements and Resonance Assignments

Typical homonuclear and heteronuclear NMR spectra (Wüthrich, 1986; Bax, 1994) were recorded on Bruker DMX-750 (750.13 MHz for 1H and 76.02 MHz for 15N) and DMX-500 (500.13 MHz for 1H, 125.76 MHz for 13C, and 50.68 MHz for 15N) spectrometers (Karlsruhe, Germany) at 298 K, essentially as previously described (Yamasaki et al., 2004a). The backbone and side chain resonance assignments were analyzed as described previously (Yamasaki et al., 2004a). HSQC spectra of samples containing 100% D2O were recorded at 283 K, by which 19 hydrogen bond donors were identified. Using the HMQC-J experiment (Kay and Bax, 1989), 49 3JHNHα coupling values were obtained. By analyzing the NOESY, TOCSY, and DQF-COSY spectra, 22 and 6 pairs of Hβ and Val Hγ resonances, respectively, were assigned stereospecifically.

Determination of the Three-Dimensional Structures

The distance constraints derived from the NOESY spectra were classified into four categories, 1.5 to 2.8, 1.5 to 3.5, 2.0 to 4.5, and 2.5 to 6.0 Å, according to the relationship that NOE intensity is inversely proportional to the sixth power of distance, which was calibrated with the average intensities of the intraresidue NOEs of Hδ-Hɛ pairs of Phe or Tyr residues. When a pair of NOEs from chemically equivalent protons (e.g., Hβ1 and Hβ2) without stereospecific assignment was classified into the same distance category, two separate constraints were imposed as if they were stereospecifically assigned. For other NOEs from stereospecifically unassigned protons, the constraints were imposed using the sum-averaged distances from all the equivalent protons (Nilges, 1993). For maintaining a hydrogen bond, a constraint of 1.5 to 2.5 Å was imposed on the distance between the hydrogen and the acceptor oxygen, whereas another constraint, of 2.5 to 3.5 Å, was imposed on the distance between the donor nitrogen and the acceptor oxygen. A force constant of 150 kcal mol−1 Å−2 was used for these distance constraints.

The φ angle constraints were classified into three categories, −120° ± 50°, −65° ± 35°, and −100° ± 70°, corresponding to the 3JαN coupling values larger than 8.0 Hz, smaller than 7.0 Hz, and 7.0 to 8.0 Hz, respectively. For stereospecifically assigned residues, χ1 torsion angle constraints classified into three categories, 60° ± 40°, 180° ± 40°, and −60° ± 40°, were imposed. A force constant of 100 to 200 kcal mol−1 rad−2 was used for the dihedral angle constraints.

To maintain the zinc coordination, theoretical constraints were imposed on the Zn–S and Zn–N distances, the Sγ–Zn–Sγ, Sγ–Zn–N, and Cβ–Sγ–Zn angles, and the Zn–imidazole ring planes, as described (Lee et al., 1989). The force constants were 150 kcal mol−1 Å−2, 30 kcal mol−1 rad−2, and 500 kcal mol−1 Å−2 for the theoretical distance, angle, and plane positional constraints, respectively.

Random simulated annealing (Nilges et al., 1988) was performed using the program CNS (Brünger et al., 1998). At the initial stage of the structure calculation, NOE distance and dihedral angle constraints were imposed. The hydrogen bond and theoretical constraints were used only at the final stage of the calculation, so that the hydrogen bond acceptors and zinc-coordinating atoms were determined using the structures obtained at an earlier stage. From 50 initial structures, 20 structures with no distance violation larger than 0.2 Å, no torsion angle violation larger than 2°, and the lowest total energies were selected as accepted structures. The minimized mean structures were produced by a protocol for the selection of the accepted structures in the CNS program. The average rms deviations of the coordinates from the unminimized mean structure of the ensemble (Table 1) were calculated using the program MOLMOL (Koradi et al., 1996). The φ and ψ dihedral angles were analyzed using the program Procheck-NMR (Laskowski et al., 1996). The secondary structure elements were also identified by Procheck-NMR.

Surface Plasmon Resonance

Experiments were performed at 298 K using a Biacore X apparatus (Biacore, Uppsala, Sweden). The running buffer was 20 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.0, containing 100 to 300 mM KCl, and 0.005% Tween 20. A total of 583 and 539 resonance units of two double-stranded DNAs, 5′-bio-CGCCTTTGACCAGCGC-3′/5′-GCGCTGGTCAAAGGCG-3′ (the W-box consensus sequence is underlined) and 5′-bio-TCTTTAATTTCTAATATATTTAGAA-3′/5′-TTCTAAATATATTAGAAATTAAAGA-3′, respectively (“bio” indicates the 5′-biotinylated strand), were immobilized on the surfaces of Sensor Chip SAs (Biacore) in one (flow cell 2) of the two flow cells, and the other was treated as the control. Solutions containing WRKY4-C, at concentrations of 2 nM to 1 μM, were injected into the flow cells at 20 μL min−1 for 5 min. The equilibrium binding constants were obtained by fitting the equilibrium response values at different protein concentrations to the simple 1:1 binding model using BIAevaluation 3.0 software (Biacore).

NMR Titration Analysis

HSQC spectra of WRKY4-C at the initial concentration of 0.20 mM, dissolved in 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, containing 200 mM KCl, 20 μM ZnCl2, 1 mM deuteriated DTT, 0.5 mM 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate, and 5% D2O, were recorded at 298 K by adding increasing amounts of 4.2 mM of the double-stranded 16mer DNA (5′-CGCCTTTGACCAGCGC-3′/5′-GCGCTGGTCAAAGGCG-3′; the W-box consensus sequence is underlined) dissolved in the same buffer. The concentration of the double-stranded DNA was determined using an extinction coefficient calculated after digestion of the strands with phosphodiesterase I (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ). The assignments of the backbone 1H and 15N resonances of WRKY4-C in the complex with DNA were completed by analyses of heteronuclear three-dimensional spectra recorded on the complex sample at a concentration of 0.8 mM.

Structural Modeling of the WRKY4-C/DNA Complex and WRKY4-N

Starting from an initial model in which the side of the protein containing the residues with largely affected chemical shifts in the DNA titration experiment was oriented to the DNA major groove, the most energetically favored structure was obtained by a careful and systematic search, essentially as described previously (Yamasaki et al., 2004a). The structure model of WRKY4-N was produced on the basis of sequence homology to WRKY4-C, essentially as described (Yamasaki et al., 2004b).

The coordinates of the determined structure have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession ID 1WJ2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank N. Matsuda, Y. Motoda, Y. Fujikura, M. Saito, Y. Miyata, K. Hanada, A. Kobayashi, N. Sakagami, M. Ikari, F. Hiroyasu, Y. Nishimura, M. Watanabe, M. Sato, M. Hirato, H. Hamana, N. Oobayashi, and Y. Kamerari for technical assistance, P. Reay and N. Eckardt for critical reading and improvement of the manuscript, and Y. Ota for collaboration on related proteins and continuous encouragement. The molecular modeling calculations in this study were partially conducted using the resources in the Computer Center for Agriculture, Foresty, and Fisheries Research. This work was supported in part by the RIKEN Structural Genomics/Proteomics Initiative and the National Project on Protein Structural and Functional Analyses, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology.

The authors responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) are: Kazuo Shinozaki (sinozaki@rtc.riken.go.jp) and Shigeyuki Yokoyama (yokoyama@biochem.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp).

Online version contains Web-only data.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.104.026435.

References

- Allen, M.D., Yamasaki, K., Ohme-Takagi, M., Tateno, M., and Suzuki, M. (1998). A novel mode of DNA recognition by a β-sheet revealed by the solution structure of the GCC-box binding domain in complex with DNA. EMBO J. 17, 5484–5496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax, A. (1994). Multidimensional nuclear magnetic resonance methods for protein studies. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 4, 738–744. [Google Scholar]

- Brünger, A.T., et al. (1998). Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case, D.A., et al. (2002). AMBER 7. (San Francisco: University of California).

- Chen, C., and Chen, Z. (2000). Isolation and characterization of two pathogen- and salicylic acid-induced genes encoding WRKY DNA-binding proteins from tobacco. Plant Mol. Biol. 42, 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.X., Moulin, M., Hashemolhosseini, S., Kilian, K., Wegner, M., and Müller, C.W. (2003). Structure of the GCM domain-DNA complex: A DNA-binding domain with a novel fold and mode of target site recognition. EMBO J. 22, 1835–1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Pater, S., Greco, V., Pham, K., Memelink, J., and Kijne, J. (1996). Characterization of a zinc-dependent transcriptional activator from Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 4624–4631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, L., and Chen, Z. (2000). Identification of genes encoding receptor-like protein kinases as possible targets of pathogen- and salicylic acid-induced WRKY DNA-binding proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 24, 837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, H.A., Olsen, A.N., Skriver, K., Larsen, S., and Lo Leggio, L. (2004). Structure of the conserved domain of ANAC, a member of the NAC family of transcription factors. EMBO Rep. 5, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulgem, T., Rushton, P.J., Robatzek, S., and Somssich, I.E. (2000). The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 5, 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulgem, T., Rushton, P.J., Schmelzer, E., Hahlbrock, K., and Somssich, I.E. (1999). Early nuclear events in plant defence signaling: Rapid gene activation by WRKY transcription factors. EMBO J. 18, 4689–4699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara, K., Yagi, M., Kusano, T., and Sano, H. (2000). Rapid systematic accumulation for transcripts encoding a tobacco WRKY transcrption factor upon wounding. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263, 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm, L., and Sander, C. (1993). Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 233, 123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T., and Duman, J.G. (2002). Cloning and characterization of a thermal hysteresis (antifreeze) protein with DNA-binding activity from winter bittersweet nightshade, Solanum dulcamara. Plant Mol. Biol. 48, 339–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro, S., and Nakamura, K. (1994). Characterization of a cDNA encoding a novel DNA-binding protein, SPF1, that recognizes SP8 sequences in the 5′ upstream regions of genes coding for sporamin and β-amylase from sweet potato. Mol. Gen. Genet. 244, 563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaguirre, M.M., Scopel, A.L., Baldwin, I.T., and Ballare, C.L. (2003). Convergent responses to stress. Solar ultraviolet-B radiation and Manduca sexta herbivory elicit overlapping transcriptional responses in field-grown plants of Nicotiana longiflora. Plant Physiol. 132, 1755–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C.S., Kolevski, B., and Smyth, D.R. (2002). TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA2, a trichome and seed coat development gene of Arabidopsis, encodes a WRKY transcription factor. Plant Cell 14, 1359–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay, L.E., and Bax, A. (1989). New methods for measurement of NH-CαH coupling constants in 15N-labelled proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 86, 110–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kigawa, T., Yabuki, T., Matsuda, N., Matsuda, T., Nakajima, R., Tanaka, A., and Yokoyama, S. (2004). Preparation of Escherichia coli cell extract for highly productive cell-free protein expression. J. Struct. Funct. Genomics 5, 63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kigawa, T., Yabuki, T., Yoshida, Y., Tsutsui, M., Ito, Y., Shibata, T., and Yokoyama, S. (1999). Cell-free production and stable-isotope labelling of milligram quantities of proteins. FEBS Lett. 442, 15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koradi, R., Billeter, M., and Wüthrich, K. (1996). MOLMOL: A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis, P.J. (1991). MOLSCRIPT: A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24, 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R.A., Rullmann, J.A.C., MacArthur, W.M., Kaptein, R., and Thornton, J.M. (1996). AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: Programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 8, 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.S., Gippert, G.P., Soman, K.V., Case, D.A., and Wright, P.E. (1989). Three-dimensional solution structure of a single zinc finger DNA-binding domain. Science 245, 635–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeo, K., Hayashi, S., Kojima-Suzuki, H., Morikami, A., and Nakamura, K. (2001). Role of conserved residues of the WRKY domain in the DNA-binding to tobacco WRKY family proteins. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 65, 2428–2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnani, E., Sjölander, K., and Hake, S. (2004). From endonucleases to transcription factors: Evolution of the AP2 DNA binding domain in plants. Plant Cell 16, 2265–2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilges, M. (1993). A calculation strategy for the structure determination of symmetric dimers by 1H NMR. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 17, 297–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilges, M., Clore, G.M., and Gronenborn, A.M. (1988). Determination of the three-dimensional structures of proteins from inter-proton distance data by dynamic simulated annealing from a random array of atoms. FEBS Lett. 239, 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace, C.N., Vajdos, F., Fee, L., Grimsley, G., and Gray, T. (1995). How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 4, 2411–2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pnueli, L., Hallak-Herr, E., Rozenberg, M., Cohen, M., Goloubinoff, P., Kaplan, A., and Mittler, R. (2002). Molecular and biochemical mechanisms associated with dormancy and drought tolerance in the desert legume Retama raetam. Plant J. 31, 319–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riechmann, J.L., Heard, J., Martin, G., Reuber, L., Jiang, C.-Z., Keddie, J., Adam, L., Pineda, O., Ratcliffe, O.J., Samaha, R.R., Creelman, R., Pilgrim, M., et al. (2000). Arabidopsis transcription factors: Genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science 290, 2105–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizhsky, L., Liang, H., and Mittler, R. (2002). The combined effect of drought stress and heat shock on gene expression in tobacco. Plant Physiol. 130, 1143–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robatzek, S., and Somssich, I.E. (2001). A new member of the Arabidopsis WRKY transcription factor family, AtWRKY6, is associated with both senescence- and defence-related processes. Plant J. 28, 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, P.J., Macdonald, H., Huttly, A.K., Lazarus, C.M., and Hooley, R. (1995). Members of a new family of DNA-binding proteins bind to a conserved cis-element in the promoters of α-Amy2 genes. Plant Mol. Biol. 29, 691–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, P.J., Torres, J.T., Parniske, M., Wernert, P., Hahlbrock, K., and Somssich, I.E. (1996). Interaction of elicitor-induced DNA-binding proteins with elicitor response elements in the promoters of parsley PR1 genes. EMBO J. 15, 5690–5700. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki, M., et al. (2002. a). Monitoring the expression profiles of 7000 Arabidopsis genes under drought, cold and high-salinity stresses using a full-length cDNA microarray. Plant J. 31, 279–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki, M., et al. (2002. b). Functional annotation of a full-length Arabidopsis cDNA collection. Science 296, 141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C., Palmqvist, S., Olsson, H., Boren, M., Ahlandsberg, S., and Jansson, C. (2003). A novel WRKY transcription factor, SUSIBA2, participates in sugar signaling in barley by binding to the sugar-responsive elements of the iso1 promoter. Plant Cell 15, 2076–2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.D., Gibson, T.J., Plewniak, F., Jeanmougin, F., and Higgins, D.G. (1997). The CLUSTAL-X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4876–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ülker, B., and Somssich, I.E. (2004). WRKY transcription factors: From DNA binding towards biological function. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 7, 491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojciak, J.M., Connolly, K.M., and Clubb, R.T. (1999). NMR structure of the Tn916 integrase-DNA complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody, R.W. (1995). Circular dichroism. Methods Enzymol. 246, 34–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wüthrich, K. (1986). NMR of Proteins and Nucleic Acids. (New York: John Wiley & Sons).

- Yamasaki, K., et al. (2004. a). A novel zinc-binding motif revealed by solution structures of DNA-binding domains of Arabidopsis SBP-family transcription factors. J. Mol. Biol. 337, 49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki, K., et al. (2004. b). Solution structure of the B3 DNA binding domain of the Arabidopsis cold-responsive transcription factor RAV1. Plant Cell 16, 3448–3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama, S., et al. (2000). Structural genomics projects in Japan. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7 (suppl.), 943–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.L., Xie, Z., Zou, X., Casaretto, J., Ho, T.H., and Shen, Q.J. (2004). A rice WRKY gene encodes a transcriptional repressor of the gibberellin signaling pathway in aleurone cells. Plant Physiol. 134, 1500–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.