Abstract

Aim

The aim of the study was to synthesize the evidence on the essential elements, nurses must address when they perform therapeutic education to patients and their caregivers to promote a safe paediatric hospital‐to‐home discharge.

Design

A systematic review and narrative synthesis.

Methods

The search strategy identifies studies published between 2016 and 2023. The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklists. The protocol of this review was not registered. A search of three electronic databases (PubMed, CINAHL and Web of Science) and a search in the reference lists of the included studies was conducted in February 2021 and June 2023.

Results

Fifteen studies met the inclusion criteria. The essential elements identified are grouped into the following topics: emergency management, physiological needs, medical device and medications management, long‐term management and short‐term management. Nurses have a critical role in ensuring patient safety and quality of care, and the nurses' competence makes the difference in the discharge's related outcomes. Our results can help the nursing profession implement comprehensive discharge projects. Our results support the improvement of nurse‐led paediatric discharge programmes. Nurse managers can identify the grey areas of therapeutic education provided in their units and work for their improvement. Following the implementation of therapeutic education on these topics, measuring the discharge's related outcomes could be interesting. This study addresses the problem of managing a safe and efficient nurse‐led discharge in a paediatric setting. It presents evidence on the essential elements to promote a safe paediatric discharge at home. These could impact nursing practice by using them to implement project and discharge pathways. We have adhered to relevant EQUATOR guidelines—PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic review. No patients, service users, caregivers or public members were involved in this study due to its nature (systematic review).

Keywords: nurse's role, nursing, paediatrics, patient discharge, patient education, systematic reviews

1. INTRODUCTION

In the United States, in 2014, an average of nearly 10,000 paediatric patients were discharged from hospitals (Berry et al., 2014). In Italy, between 2017 and 2018 (the most recent data available), we have had a rate of 61.89 paediatric hospital discharges per thousand inhabitants (National Observatory on Health in the Italian Regions, 2021). Since 2001, the Institute of Medicine has stated that a safe hospital discharge, timely and efficient, is a marker for the quality of care (Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, 2001). A ‘safe discharge’ is not conceptualized but is commonly intended as the lowest probability of developing adverse outcomes after discharge (Goodacre, 2006). However, 22 years have passed since this statement, and even if many projects aim to improve discharge outcomes (like healthcare services reuse, hospital readmission, and length of stay), they all light some complications that emerge if the discharge process presents some fragility that must be addressed. The main issues related to discharge management from patients and families are follow‐up management (i.e. the difficulty in getting an appointment), medications (i.e. the difficulties in filling a prescription) and lack of understanding the change in health condition to pay attention (that led to an E.R. readmission) (Glick et al., 2017; Heath et al., 2015; Rehm et al., 2018; Warembourg et al., 2020). Other studies identify a lack of readiness for hospital discharge of family caregivers (Lu et al., 2022) or a lack of resources provided explicitly for paediatric patients (Chen et al., 2022). In addition, the studies investigating the impact of improvement projects on discharge outcomes focus mainly on a specific population or disease, like paediatric patients with asthma (Ekim & Ocakci, 2016), cardiovascular diseases (Staveski et al., 2016) or orthopaedic pathologies (Garin, 2020).

This specification on some health conditions drives both a lack of standardization and a univocal gold standard to follow to promote a safe paediatric discharge at home. A framework on paediatric discharge was published to address this issue, outlining nine steps to follow to promote a safe discharge at home. This framework has a section on the information the patients and their families must possess to manage a safe discharge. However, there is no precise specification about the topic that must be addressed before the discharge (e.g. medication or follow‐up appointments) (Berry et al., 2014).

Therefore, despite the efforts made in the literature to promote a safe paediatric discharge at home, the essential information elements still need to be clarified and not focused on specific pathologies' management and designated to the paediatric discharge as a whole.

With the terms ‘essential elements’, we referred to the discharge healthcare needs and the factors that could influence the child's health after leaving the hospital, identified during the therapeutic education process performed during a hospital stay by nurses. In this manuscript, we refer to therapeutic education as defined by the World Health Organization in 1996: therapeutic education is intended to help patients and their families acquire or maintain the skills to manage their lives with a chronic disease in the best possible way (World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe, 1998).

Nurses perform a central role in the discharge process (Ali Pirani, 2010; Breneol et al., 2018) because they are on the front line of patient care from hospital admission to the moment of discharge. Therefore, they are the principal facilitators of promoting a safe discharge at home, in every setting, including paediatrics. In 2018, Breneol and colleagues published a scoping review to synthesize and map what is known about nurse‐led discharge in paediatric care and how the nurse's role in this process is defined. Their results show a study's paucity on this topic, highlighting a great variety in the terms utilized to identify nurses' roles in the discharge process and an ambiguity in the definition of the nurses' role in this process. In addition, most of the studies analysed showed how, differently from nurse‐led discharge in an adult setting, in the paediatric environment, nurses manage discharge without a pre‐determined order set or pathway.

Given this gap in the existing literature, we decided to conduct a systematic review that could deliver a comprehensive overview of available evidence and allow us to identify the research gaps on this topic.

The research question is: Which are the essential elements nurses must address when they perform therapeutic education to paediatric patients and their caregivers to promote a safe hospital‐to‐home discharge?

2. AIMS

Our systematic review aimed to synthesize the principal evidence about the essential elements nurses must address to promote a safe paediatric discharge at home when they perform therapeutic education.

3. METHODS

3.1. Design

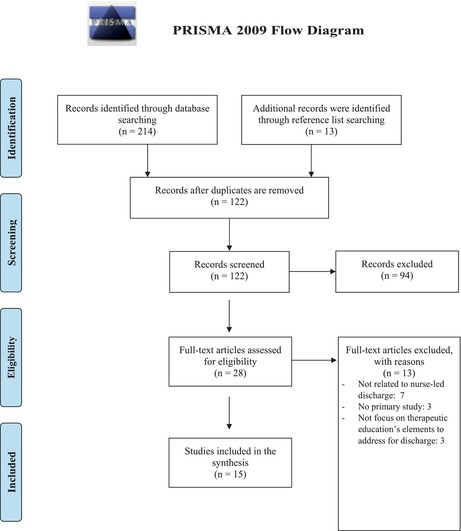

We performed this review using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) (see Supporting Information S1 and S2; Moher et al., 2010; Page et al., 2021).

3.1.1. Data sources and search strategies

We identified the keywords and elaborated the search queries for three major nursing scientific literature databases (PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science) (see Appendix 1). Appendix 1 represents the queries utilized without inserting MeSh terms, date limits or other specifications (Aali & Shokraneh, 2021). The databases were interrogated primarily on 01 February 2021. Then, due to the delay related to manuscript publication and to have the most up‐to‐date literature, another search with the same queries in the same databases was launched in June 2023.

The articles retrieved were managed with the use of Mendeley reference citation manager. The articles were initially screened to merge the duplication, and then two authors independently screened the titles and abstract of the articles against the inclusion criteria defined. The same two authors evaluated the full‐text articles that remained. Eventual doubts were clarified with the consultation of a third author until a consensus was achieved. At the end of the process, the reference lists of the included studies were screened to retrieve other pertinent articles. To keep track of the entire process, we utilized the PRISMA Flow Diagram (Moher et al., 2010) (see Appendix 2). See Appendix 3 for Search Strategy for Web of Science database.

3.1.2. Eligibility criteria

We included only studies focused on the paediatric population, nursing discharge, therapeutic education to promote discharge, patient discharge at home, studies in Italian or English languages published in the last 7 years (to have only up‐to‐date literature) and primary studies.

The exclusion criteria were studies focused on a population ≥18 years of age, studies about patients discharged in other healthcare structures and not at home, studies published before 2016 and grey literature.

Grey literature was excluded due to the subject of our review. One of the problems of the grey literature is the evaluation of the validity of what is reported in it (Higgins & Green, 2011). Given the objective of our review (research the elements to be addressed to promote a safe paediatric discharge, that is a process of discharge that could reduce the adverse outcomes connected to it—like hospital readmissions or length of stay), we decided to include only peer‐reviewed studies.

We decided not to include studies published before 2016 because Glick and colleagues have published an interesting systematic review that was used as a starting point to generate our research question (Glick et al., 2017).

3.1.3. Screening, data extraction and quality appraisal

A data extraction form was developed with the following fields: author, year and country, aim, study design, sampling, sample size, subject addressed during therapeutic education, results and relevance to clinical practice. Two authors independently extracted the data and completed the form, with the information retrieved from the included studies. We made no assumptions about missing data and left the form blank.

To assess the risk of bias and to conduct the quality assessment of the included studies, we utilized the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklists for randomized controlled trials (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2021d), cohort studies (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2021a), case–control study (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2021b) and qualitative study (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2021c). Two authors assessed the quality of the studies independently, and in case of disagreement, the assessment of a third author was sought. The results of the quality assessment were summarized in a table.

3.2. Synthesis

Characteristics of all studies were summarized to provide a narrative synthesis that addresses the review's aim. Key findings have been narratively synthesized to demonstrate the common and specific factors that the studies addressed to promote a safe paediatric discharge at home. The elements retrieved are then grouped into common topics. We used a narrative approach (Popay et al., 2006) to synthesize the included studies.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Study inclusion

A PRISMA Flow Diagram outlining the selection of eligible studies is presented in Appendix 4. Initially, 214 studies were identified through the databases searched, and after duplicates were removed, only 109 articles remained. After the title screening, only 69 articles met the inclusion criteria, and 40 were excluded because they were published before 2016, were not primary studies, were referred to adult settings or were written not in English or Italian languages. From the abstract screening of these 69 articles, 41 were excluded due to the following reasons: no focused on therapeutic education (n = 27), instrument development or validation (n = 6), no primary study (n = 4), no focused on paediatric discharge (n = 2), not focused on nurse‐led discharge (n = 2). Then, from the full‐text selection, only 13 studies met the inclusion criteria, and an additional 13 full‐text were retrieved from the analysis of the reference lists, two of them included in the final synthesis. At the end of the screening process, 15 articles were included in the synthesis.

4.2. Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the included studies. All included studies (n = 15) were published in English between 2016 and 2022. 12 studies were conducted in the USA (Auger et al., 2018; Brooks et al., 2022; Desai et al., 2016; Jubic et al., 2022; Leyenaar et al., 2017; Mallory et al., 2017; Moo‐Young et al., 2019; Parikh et al., 2018, 2021; Patra et al., 2020; Shermont et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016), one was conducted in Turkey (Ekim & Ocakci, 2016), and two in Australia (Aydon et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2021).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Author, year | Country and setting | Aim | Study design | Sampling and sample size | Subject of therapeutic education addressed to promote safe discharge | Results and relevance to clinical practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parikh et al. (2021) |

|

|

Prospective pilot randomized clinical trial. |

Patient/caregiver dyads (children with asthma) were prospectively enrolled during hospitalization. The randomization results in 16 dyads per arm. |

|

Patient Navigator, SBAT, and medications in hand were classified as ‘extremely helpful’ by 100%. There was a trend in lower healthcare reuse, but it was not statistically significant. Individualized, multi‐component interventions initiated during an asthma‐related hospitalization are feasible and acceptable in an urban minority population. |

| Auger et al. (2018) |

|

Assess the effects of a post‐discharge telephone call on reuse events for urgent health care services, parental coping, and recall of crucial clinical information after standard paediatric discharge. | 2‐arm randomized clinical trial. | Patients ≤18 years (n = 966) who would not require skilled nursing after discharge. Enrolled participants were randomized 1:1 using a block randomization approach with two stratification factors (neighbourhood poverty and state of residency). |

|

A telephone call did not result in a decrease in reuse events. However, parents who received the telephone call could better recall clinical red flags or warning signs. |

| Desai et al. (2016) |

|

Explore caregiver needs and preferences for achieving high‐quality hospital‐to‐home transitions. | Qualitative study. | 18 English‐speaking caregivers of patients older than 1 month of age and hospitalized in the medical or surgical unit were recruited with convenience sampling. |

|

The findings under light needs and preferences of caregivers to promote a safe home discharge. These findings might be used to inform paediatric transition interventions. |

| Ekim and Ocakci (2016) |

|

Test the efficacy of a transition theory‐based discharge planning programme for managing childhood asthma. | A quasi‐experimental study using a prospective clinical trial design with two groups. | 120 children with asthma (age range 1–6 years) and their mothers participated in the study. Subjects were recruited consecutively on admission. |

|

The results show that the intervention improves asthma management. The access to emergency departments and unscheduled visits were significantly reduced, and the self‐efficacy perception level was significantly higher. The main components of a transition theory‐based discharge planning programme can guide nurses in developing family‐centred interventions and planning for individualized care. |

| Jubic et al. (2022) |

|

Improve the discharge process, increase patient experience related to discharge, and decrease the hospital's 7‐day readmission rate. | Plan‐Do‐Study‐Act cycle to conduct an improvement project. | Convenience sampling. |

|

The new discharge process was effective in reducing the 7‐day readmission rate. The patient experience measured with the CAHPS Child Hospital Survey increased. |

| Zhou et al. (2021) |

|

Observe and describe the experience of nurse–caregiver communication in the hospital‐to‐home transition. | Qualitative descriptive research involves clinical observations, semi‐structured interviews, and medical records audits. | Purposive sampling with 31 observations and medical records audit, 20 semi‐structured interviews with caregivers (of children admitted for tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy, appendectomy, and bronchiolitis), and 12 with nurses. |

|

Six common components were identified: information on diagnosis/procedure and treatments, expected symptoms, continuity of care, when and where to seek medical assistance, follow‐up appointments, and confirmation of caregivers' understanding. Nurses recognize that information delivery is very individual, and communication must start earlier than in the last 15 min. |

| Mallory et al. (2017) |

|

Demonstrate the feasibility of implementing a 4‐element patient‐centred paediatric care transition and assess their early impact on caregivers' home management skills and reuse rates. | Quasi‐experimental cohort design with project implementation. |

Convenience sampling. Four sites, 2601 patient records and 1394 post‐discharge phone calls. Subjects were technology‐supported and non‐technology‐supported patients aged 0–18. |

|

The bundle implementation improved teach‐back, timely and complete handoff, follow‐up phone call connectivity and discharge checklist use. |

| Moo‐Young et al. (2019) |

|

Increase the percentage of paediatric gastroenterology patients discharged before 1 p.m. and reduce the length of stay. | Quasi‐experimental cohort design, with pre and post‐test. | Convenience sampling (of acute gastroenterology patients), with 154 discharges in the pre‐intervention and 201 post‐intervention periods. |

|

The patient's length of stay had declined in the post‐intervention period. There was no other impact on the evaluated outcomes. Work on family education, empowerment, and standardized discharge criteria could be essential to promote a discharge‐oriented culture. |

| Leyenaar et al. (2017) |

|

Examine the preferences, priorities, and goals of parents of children with medical complexity regarding discharge planning and ascertain healthcare providers' perceptions of families' transitional care needs. | Qualitative descriptive design. | Purposive sampling of 23 parents of children with chronic conditions and 16 healthcare providers. |

|

Families prioritized effective family engagement with the health care team and desired normalization during hospitalization and after hospital discharge. This research provides a paediatric‐specific framework to engage families in planning discharge. |

| Shermont et al. (2016) |

|

Describes the implementation and effectiveness of a discharge bundle in combination with teach‐back methodology and structured handoff to reduce unplanned readmissions. | A quasi‐experimental study with pre‐ and post‐intervention tests. | Convenience sampling of 16 inpatient units (surgical, medical, neurology, transplant, intensive care, intermediate care, oncology and a surgical satellite unit). |

|

The intervention was associated with a relative reduction in unplanned readmission. All units improved performance by scheduling follow‐up appointments, patient/family comprehension of the care plan, knowing whom to call in an emergency and discharge medication reconciliation. |

| Wu et al. (2016) |

|

Examine whether shared improvement strategies would affect discharge‐related care failures, parent‐reported readiness for discharge and readmission. | Quality improvement project. | Convenience sampling, with 11 hospitals. |

|

There was a decrease in discharge‐related care failures and an improvement in the family's perception of discharge readiness, but no improvement in unplanned readmission. This study shows the potential benefit of the collaborative approach. |

| Aydon et al. (2018) |

|

Exploring the discharge experience of parents with babies born between 28 and 32 weeks gestation and their transition to home. | Descriptive qualitative design. | Convenience sampling of 20 sets of parents of babies admitted to NICU. |

|

Three overarching concepts: practical parent–staff communication, feeling informed and involved, and being prepared to go home. Some suggested strategies are improving information transfer, promoting parental contact with staff and encouraging fathers' input to facilitate parental involvement. |

| Parikh et al. (2018) |

|

Build an understanding of the barriers and facilitators of asthma management from the perspective of family caregivers and health professionals. | Descriptive qualitative design. | Convenience and purposeful sampling of 19 family caregivers of children with asthma or health professionals. |

|

This study identifies barriers and facilitators of asthma management after hospitalization that could help to create an effective patient‐centred and stakeholder‐aligned intervention to improve asthma management. |

| Patra et al. (2020) |

|

Evaluating the outcomes of using a standardized process for hospital discharge of paediatric patients. | Cohort study with pre‐ and post‐intervention design. | Convenience sampling with 1321 patients in the preintervention group and 1413 patients in the postintervention group. |

|

The length of stay decreases significantly after the intervention. An evidence‐based discharge risk assessment and interventions checklist can improve the discharge process. |

| Brooks et al. (2022) |

|

|

A prospective descriptive study with pre‐ and post‐intervention design. | A convenience sample of caregivers of tracheostomy‐dependent children with medically complex diagnoses. |

|

This CPR education has positively impacted caregivers' abilities to perform emergency management behaviours effectively. Including simulation in discharge education protocols may benefit children and their caregivers. |

Of the included studies, two were randomized controlled trials (Auger et al., 2018; Parikh et al., 2021), five of them were qualitative studies (Aydon et al., 2018; Desai et al., 2016; Leyenaar et al., 2017; Parikh et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2021), six were cohort studies (Brooks et al., 2022; Jubic et al., 2022; Mallory et al., 2017; Moo‐Young et al., 2019; Patra et al., 2020; Shermont et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016), and only one was a case–control study (Ekim & Ocakci, 2016).

4.3. Methodological quality of included studies

A summary of the quality of the included studies is presented in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5. The studies' quality ranged from middle to high quality: the two randomized controlled trials have a middle quality because none of them had blinded the participants, the investigators or the people analysing data (Auger et al., 2018; Parikh et al., 2021). The five qualitative studies have a high quality (Aydon et al., 2018; Desai et al., 2016; Leyenaar et al., 2017; Parikh et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2021), and also the only case–control study has a high quality (even if we cannot estimate the treatment effect) (Ekim & Ocakci, 2016). The quality of the seven cohort studies varies a lot, and the principal critical issues are referred to participant recruitment and the management of the confounding factors (Brooks et al., 2022; Jubic et al., 2022; Mallory et al., 2017; Moo‐Young et al., 2019; Patra et al., 2020; Shermont et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016). The studies with a middle quality are valuable to answer our research question. Therefore, all the studies were included in the final synthesis.

TABLE 2.

Quality appraisal of the randomized controlled trial included studies.

| Authors, year | CASP question | CASP answers |

|---|---|---|

| Randomized controlled trial | ||

| Parikh et al. (2021) | 1. Did the study address a clearly focused research question? | 1. Yes |

| 2. Was the assignment of participants to interventions randomized? | 2. Yes | |

| 3. Were all participants who entered the study accounted for at its conclusion? | 3. Yes | |

| 4. Were the participants (a) and investigators (b), and people analysing data (c) ‘blind’ to intervention? |

4(a). No 4(b). Yes 4(c). Yes |

|

| 5. Were the study groups similar at the start of the randomized controlled trial? | 5. Yes | |

| 6. Apart from the experimental intervention, did each study group receive the same level of care (that is, were they treated equally)? | 6. Yes | |

| 7. Were the effects of intervention reported comprehensively? | 7. Yes | |

| 8. Was the precision of the estimate of the intervention or treatment effect reported? | 8. No | |

| 9. Do the benefits of the experimental intervention outweigh the harms and costs? | 9. Cannot tell | |

| 10. Can the results be applied to your local population/in your context? | 10. Yes | |

| 11. Would the experimental intervention provide greater value to the people in your care than any of the existing interventions? | 11. Cannot tell | |

| Auger et al. (2018) | 1. Did the study address a clearly focused research question? | 1. Yes |

| 2. Was the assignment of participants to interventions randomized? | 2. Yes | |

| 3. Were all participants who entered the study accounted for at its conclusion? | 3. No | |

| 4. Were the participants (a) and investigators (b), and people analysing data(c) ‘blind’ to intervention? |

4(a). No 4(b). Yes 4(c). No |

|

| 5. Were the study groups similar at the start of the randomized controlled trial? | 5. Yes | |

| 6. Apart from the experimental intervention, did each study group receive the same level of care (that is, were they treated equally)? | 6. Yes | |

| 7. Were the effects of intervention reported comprehensively? | 7. Yes | |

| 8. Was the precision of the estimate of the intervention or treatment effect reported? | 8. No | |

| 9. Do the benefits of the experimental intervention outweigh the harms and costs? | 9. Cannot tell | |

| 10. Can the results be applied to your local population/in your context? | 10. Yes | |

| 11. Would the experimental intervention provide greater value to the people in your care than any of the existing interventions? | 11. Cannot tell | |

Note: Negative answers are in bold.

TABLE 3.

Quality appraisal of the qualitative included studies.

| Authors, year | CASP question | CASP answers |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative study | ||

| Desai et al. (2016) | 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 1. Yes |

| 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 2. Yes | |

| 3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 3. Yes | |

| 4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 4. Yes | |

| 5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 5. Yes | |

| 6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 6. No | |

| 7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 7. No | |

| 8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 8. Yes | |

| 9. Is there a clear statement of findings? | 9. Yes | |

| 10. How valuable is the research? | 10. High valuable | |

| Zhou et al. (2021) | 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 1. Yes |

| 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 2. Yes | |

| 3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 3. Yes | |

| 4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 4. Yes | |

| 5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 5. Yes | |

| 6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 6. No | |

| 7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 7. Yes | |

| 8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 8. Yes | |

| 9. Is there a clear statement of findings? | 9. Yes | |

| 10. How valuable is the research? | 10. High valuable | |

| Leyenaar et al. (2017) | 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 1. Yes |

| 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 2. Yes | |

| 3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 3. Yes | |

| 4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 4. Yes | |

| 5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 5. Yes | |

| 6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 6. No | |

| 7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 7. Yes | |

| 8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 8. Yes | |

| 9. Is there a clear statement of findings? | 9. Yes | |

| 10. How valuable is the research? | 10. High valuable | |

| Parikh et al. (2018) | 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 1. Yes |

| 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 2. Yes | |

| 3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 3. Yes | |

| 4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 4. Yes | |

| 5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 5. Yes | |

| 6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 6. No | |

| 7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 7. Yes | |

| 8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 8. Yes | |

| 9. Is there a clear statement of findings? | 9. Yes | |

| 10. How valuable is the research? | 10. High valuable | |

| Aydon et al. (2018) | 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 1. Yes |

| 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 2. Yes | |

| 3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 3. Yes | |

| 4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 4. Yes | |

| 5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 5. Yes | |

| 6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 6. No | |

| 7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 7. Yes | |

| 8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 8. Yes | |

| 9. Is there a clear statement of findings? | 9. Yes | |

| 10. How valuable is the research? | 10. High valuable | |

Note: Negative answers are in bold.

TABLE 4.

Quality appraisal of the cohort included studies.

| Authors, year | CASP question | CASP answers |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort study | ||

| Jubic et al. (2022) | 1. Did the study address a clearly focused issue? | 1. Yes |

| 2. Was the cohort recruited in an acceptable way? | 2. Cannot tell | |

| 3. Was the exposure accurately measured to minimize bias? | 3. No | |

| 4. Was the outcome accurately measured to minimize bias? | 4. Cannot tell | |

| 5. (a) Have the authors identified all important confounding factors? | 5(a). No | |

| (b) Have they taken account of the confounding factors in the design and/or analysis? | 5(b). Cannot tell | |

| 6. (a) Was the follow‐up of subjects complete enough? | 6(a). Cannot tell | |

| (b) Was the follow‐up of subjects long enough? | 6(b). Cannot tell | |

| 7. What are the results of this study? | 7. See Table 1 | |

| 8. How precise are the results? | 8. Enough | |

| 9. Do you believe the results? | 9. Yes | |

| 10. Can the results be applied to the local population? | 10. Yes | |

| 11. Do the results of this study fit with other available evidence? | 11. Yes | |

| 12. What are the implications of this study for practice? | 12. See Table 1 | |

| Mallory et al. (2017) | 1. Did the study address a clearly focused issue? | 1. Yes |

| 2. Was the cohort recruited in an acceptable way? | 2. Cannot tell | |

| 3. Was the exposure accurately measured to minimize bias? | 3. No | |

| 4. Was the outcome accurately measured to minimize bias? | 4. Cannot tell | |

| 5. (a) Have the authors identified all important confounding factors? | 5(a). No | |

| (b) Have they taken account of the confounding factors in the design and/or analysis? | 5(b). Cannot tell | |

| 6. (a) Was the follow‐up of subjects complete enough? | 6(a). Yes | |

| (b) Was the follow‐up of subjects long enough? | 6(b). Cannot tell | |

| 7. What are the results of this study? | 7. See Table 1 | |

| 8. How precise are the results? | 8. Enough | |

| 9. Do you believe the results? | 9. Yes | |

| 10. Can the results be applied to the local population? | 10. Yes | |

| 11. Do the results of this study fit with other available evidence? | 11. Yes | |

| 12. What are the implications of this study for practice? | 12. See Table 1 | |

| Moo‐Young et al. (2019) | 1. Did the study address a clearly focused issue? | 1. Yes |

| 2. Was the cohort recruited in an acceptable way? | 2. Cannot tell | |

| 3. Was the exposure accurately measured to minimize bias? | 3. No | |

| 4. Was the outcome accurately measured to minimize bias? | 4. Cannot tell | |

| 5. (a) Have the authors identified all important confounding factors? | 5(a). No | |

| (b) Have they taken account of the confounding factors in the design and/or analysis? | 5(b). Cannot tell | |

| 6. (a) Was the follow‐up of subjects complete enough? | 6(a). Yes | |

| (b) Was the follow‐up of subjects long enough? | 6(b). Yes | |

| 7. What are the results of this study? | 7. See Table 1 | |

| 8. How precise are the results? | 8. Enough | |

| 9. Do you believe the results? | 9. Yes | |

| 10. Can the results be applied to the local population? | 10. Yes | |

| 11. Do the results of this study fit with other available evidence? | 11. Yes | |

| 12. What are the implications of this study for practice? | 12. See Table 1 | |

| Shermont et al. (2016) | 1. Did the study address a clearly focused issue? | 1. Yes |

| 2. Was the cohort recruited in an acceptable way? | 2. Cannot tell | |

| 3. Was the exposure accurately measured to minimize bias? | 3. No | |

| 4. Was the outcome accurately measured to minimize bias? | 4. Cannot tell | |

| 5. (a) Have the authors identified all important confounding factors? | 5(a). Cannot tell | |

| (b) Have they taken account of the confounding factors in the design and/or analysis? | 5(b). Cannot tell | |

| 6. (a) Was the follow‐up of subjects complete enough? | 6(a). Yes | |

| (b) Was the follow‐up of subjects long enough? | 6(b). Yes | |

| 7. What are the results of this study? | 7. See Table 1 | |

| 8. How precise are the results? | 8. Enough | |

| 9. Do you believe the results? | 9. Yes | |

| 10. Can the results be applied to the local population? | 10. Yes | |

| 11. Do the results of this study fit with other available evidence? | 11. Yes | |

| 12. What are the implications of this study for practice? | 12. See Table 1 | |

| Wu et al. (2016) | 1. Did the study address a clearly focused issue? | 1. Yes |

| 2. Was the cohort recruited in an acceptable way? | 2. Cannot tell | |

| 3. Was the exposure accurately measured to minimize bias? | 3. No | |

| 4. Was the outcome accurately measured to minimize bias? | 4. Cannot tell | |

| 5. (a) Have the authors identified all important confounding factors? | 5(a). Cannot tell | |

| (b) Have they taken account of the confounding factors in the design and/or analysis? | 5(b). Cannot tell | |

| 6. (a) Was the follow‐up of subjects complete enough? | 6(a). Yes | |

| (b) Was the follow‐up of subjects long enough? | 6(b). Yes | |

| 7. What are the results of this study? | 7. See Table 1 | |

| 8. How precise are the results? | 8. Enough | |

| 9. Do you believe the results? | 9. Yes | |

| 10. Can the results be applied to the local population? | 10. Yes | |

| 11. Do the results of this study fit with other available evidence? | 11. Yes | |

| 12. What are the implications of this study for practice? | 12. See Table 1 | |

| Patra et al. (2020) | 1. Did the study address a clearly focused issue? | 1. Yes |

| 2. Was the cohort recruited in an acceptable way? | 2. Cannot tell | |

| 3. Was the exposure accurately measured to minimize bias? | 3. Yes | |

| 4. Was the outcome accurately measured to minimize bias? | 4. Cannot tell | |

| 5. (a) Have the authors identified all important confounding factors? | 5(a). Cannot tell | |

| (b) Have they taken account of the confounding factors in the design and/or analysis? | 5(b). Cannot tell | |

| 6. (a) Was the follow‐up of subjects complete enough? | 6(a). Yes | |

| (b) Was the follow‐up of subjects long enough? | 6(b). Yes | |

| 7. What are the results of this study? | 7. See Table 1 | |

| 8. How precise are the results? | 8. Enough | |

| 9. Do you believe the results? | 9. Yes | |

| 10. Can the results be applied to the local population? | 10. Yes | |

| 11. Do the results of this study fit with other available evidence? | 11. Yes | |

| 12. What are the implications of this study for practice? | 12. See Table 1 | |

| Brooks et al. (2022) | 1. Did the study address a clearly focused issue? | 1. Yes |

| 2. Was the cohort recruited in an acceptable way? | 2. Cannot tell | |

| 3. Was the exposure accurately measured to minimize bias? | 3. Yes | |

| 4. Was the outcome accurately measured to minimize bias? | 4. Cannot tell | |

| 5. (a) Have the authors identified all important confounding factors? | 5(a). Cannot tell | |

| (b) Have they taken account of the confounding factors in the design and/or analysis? | 5(b). Cannot tell | |

| 6. (a) Was the follow‐up of subjects complete enough? | 6(a). Yes | |

| (b) Was the follow‐up of subjects long enough? | 6(b). Yes | |

| 7. What are the results of this study? | 7. See Table 1 | |

| 8. How precise are the results? | 8. Enough | |

| 9. Do you believe the results? | 9. Yes | |

| 10. Can the results be applied to the local population? | 10. Yes | |

| 11. Do the results of this study fit with other available evidence? | 11. Yes | |

| 12. What are the implications of this study for practice? | 12. See Table 1 | |

Note: Negative answers are in bold.

TABLE 5.

Quality appraisal of the case control included studies.

| Authors, year | CASP question | CASP answers |

|---|---|---|

| Case–control study | ||

| Ekim and Ocakci (2016) | 1. Did the study address a clearly focused issue? | 1. Yes |

| 2. Did the authors use an appropriate method to answer their question? | 2. Yes | |

| 3. Were the cases recruited in an acceptable way? | 3. Yes | |

| 4. Were the controls selected in an acceptable way? | 4. Yes | |

| 5. Was the exposure accurately measured to minimize bias? | 5. Yes | |

| 6(a). Aside from the experimental intervention, were the groups treated equally? | 6(a). Yes | |

| 6(b). Have the authors taken account of the potential confounding factors in the design and/or in their analysis? | 6(b). Yes | |

| 7. How large was the treatment effect? | 7. Cannot tell | |

| 8. How precise was the estimate of the treatment effect? | 8. Cannot tell | |

| 9. Do you believe the results? | 9. Yes | |

| 10. Can the results be applied to the local population? | 10. Yes | |

| 11. Do the results of this study fit with other available evidence? | 11. Yes | |

4.4. Review findings

The essential elements identified in the included studies that must be addressed to promote a safe paediatric discharge at home are included in the following topics:

4.4.1. Emergency management

This topic includes the essential elements related to therapeutic education provided about the management of emergencies. The essential elements to address are:

Triggers or red flags to pay attention to once at home and how to manage them (Auger et al., 2018; Brooks et al., 2022; Desai et al., 2016; Ekim & Ocakci, 2016; Jubic et al., 2022; Mallory et al., 2017; Parikh et al., 2018, 2021);

Education on pain control (Desai et al., 2016; Leyenaar et al., 2017);

Information about whom to call in an emergency (Brooks et al., 2022; Desai et al., 2016; Shermont et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2021).

4.4.2. Physiological needs

This topic includes the essential elements related to therapeutic education about satisfying the patient's physiological needs. The essential elements to address are:

4.4.3. Medical device and medication management

This topic includes the essential elements related to therapeutic education provided about acquiring the necessary skills to manage and utilize the possible medical device whereby the patients were discharged, as well as the management of the pharmacological therapy. The essential elements to address are:

Education about medications (Desai et al., 2016; Ekim & Ocakci, 2016; Jubic et al., 2022; Mallory et al., 2017; Parikh et al., 2021; Patra et al., 2020; Shermont et al., 2016);

Information about correctly using and managing the medical devices with which the patient was discharged (Brooks et al., 2022).

4.4.4. Long‐term management

This topic includes the essential elements related to therapeutic education provided about the condition's management over the long term. The essential elements to address are:

How to have adequate support from healthcare professionals before and after the discharge (Auger et al., 2018; Aydon et al., 2018; Brooks et al., 2022; Desai et al., 2016; Ekim & Ocakci, 2016; Leyenaar et al., 2017; Mallory et al., 2017; Parikh et al., 2018, 2021; Patra et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2021);

Education and in‐depth information about appointment lists/follow‐up and related details (Desai et al., 2016; Ekim & Ocakci, 2016; Jubic et al., 2022; Mallory et al., 2017; Patra et al., 2020; Shermont et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2021).

4.4.5. Short‐term management

This topic includes the essential elements related to therapeutic education provided about the condition's management between hospital admission and the days immediately after discharge. The essential elements to address are:

5. DISCUSSION

This study is the first review to assess the essential elements nurses must address to promote a safe discharge home in paediatric care. This review was based on 15 studies that met the inclusion criteria. The findings suggest that a checklist of the essential elements that must be addressed can be grouped into five topics as follows: (1) emergency management, (2) physiological needs, (3) medical device and medications management, (4) long‐term management and (5) short‐term management.

In many developing countries, children with medical complexity were discharged at home; this led to patients' and caregivers' need for in‐depth discharge education programmes to enable them to recognize complications and manage their children's care after hospital discharge. Some nurse‐led discharge implementation programmes have had exciting results, improving caregivers knowledge on discharge and decreasing adverse outcomes like surgical site infections (Staveski et al., 2016).

Our results show how the management of emergencies needs to be correctly taught during therapeutic education performed by nurses, which has been evident for many years (Stevens et al., 2010). Therapeutic education on this topic has to be focused on who to call in case of emergency, how to manage pain, and which are the ‘red flags symptoms’ to pay attention. These could be very challenging points because these difficulties could cause health problems and lead to hospital readmission or Emergency Department access.

On the contrary, our results show the importance of giving information about the expected symptoms and how to manage them. It is clear how the ‘red flags symptoms’ and the ‘expected symptoms’ need to be addressed in depth to help patients and families understand their health status (Sarsfield et al., 2013) and know when what they are experiencing is normal or not.

Regarding therapeutic education focused on the satisfaction of patient's physiological needs, like hydration and feeding, sleep issues and wound care, literature has shown how this topic could be challenging for caregivers to manage at home (Bharadia et al., 2023; Heath et al., 2015; Toolaroud et al., 2023). Our review highlights the need to be more precise during discharge to avoid complications or health deterioration.

Regarding medical device and medication management, one study found that children discharged with medications in hand are less likely to have 30‐day hospital readmission (Hatoun et al., 2016). This result highlights the need to focus, during the therapeutic education and discharge process, on which medication must be taken, the dosage and who can provide that drug (i.e. territorial pharmacy or hospital pharmacy) (Heath et al., 2015). In addition, other studies stated that the main issues related to medication are dose, frequency, name, duration and side effects (Glick et al., 2017; Heath et al., 2015). Also, therapeutic education about managing medical devices, like central venous catheters or pulse oximeters, is essential to avoid complications and give standardized indications that can improve the discharge's related outcomes (Fierro et al., 2022). These results point to the need to address all of this information during the therapeutic education and discharge process and to evaluate that the information given is correctly received and known before discharge.

Our results on long‐term management show how appointment management is one of the main post‐discharge issues (Glick et al., 2017; Heath et al., 2015; Rehm et al., 2018) with the problem of how to receive adequate support from healthcare professionals (like continuity of care at home). These issues appear to be most related to older age (older than 10 years), length of stay and chronic conditions (Rehm et al., 2018). It is essential to highlight how a follow‐up could be more frequent after paediatric discharge than an adult one: this could lead to difficulty in management (Rehm et al., 2018), and it is essential to pay more attention to give the correct information and to understand if the information has been correctly received.

Regarding our results on short‐term management, the restriction to normal activities was identified as an element of concerns related to discharge by other authors (Glick et al., 2017; Toolaroud et al., 2023), with our results that place the return to normal activities as an essential element to address for promoting a safe paediatric discharge at home. Otherwise, our review identifies other essential elements that need attention in this topic, such as the information about the duration of hospital stay and how to return home safely.

The studies included in our review are all conducted in a paediatric hospital setting, and the patient or caregiver enrolled varies from chronic disease (such as asthma or tracheostomy) to acute disease (such as tonsillectomy). Also, the ages ranged from 1 month to 18 years old.

These characteristics make our results applicable to all paediatric care settings.

All of these elements, if correctly addressed, could promote a safe discharge at home in paediatric settings.

Further research is needed to understand if, following a pre‐order set of topics to address during therapeutic education, like the results of this review, nurses who lead the discharge process could improve some discharge‐related outcomes.

6. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

The strength of this review is its adherence to the PRISMA guidelines, which guarantee an adequate quality of the review process. In addition to mainstream research on databases, we included other data sources by checking the bibliography of included studies. Although we observed a rigorous process in retrieving relevant articles, we may have missed some studies because we searched only English and Italian studies. Therefore, we cannot report the studies published in other languages. In addition, we do not research grey literature because we need only peer‐reviewed studies due to our research topic. The studies included had a quality ranging from medium to high. These judgements guarantee a reasonably good quality of both the methods applied in the studies and the results obtained. However, we cannot exclude that the study reporting could miss some critical information for our aim. We solved possible biases in reviewing and assessing the studies using two reviewers at each stage in the review process.

7. CONCLUSION

This review identifies the essential elements nurses must address during therapeutic education to promote a safe discharge at home in a paediatric setting.

The discharge outcomes are strictly correlated to the discharge process itself, and nurses need to provide comprehensive and individualized patient and family‐centred therapeutic education during hospital stays to reduce adverse related outcomes. Therefore, efforts among nurses and organizations to reduce adverse discharge‐related outcomes could include the elements identified in this systematic review by creating comprehensive and individualized discharge planning.

The studies included in the review were conducted in many regions globally, pointing out that the issue addressed is of global interest. The studies in the synthesis showed a need for a more comprehensive approach in the paediatric discharge practice. The results of our review could be helpful for future research on the discharge process in paediatric care, focusing on improvement projects of the discharge process by creating discharge pathways aimed to address all the essential elements retrieved in this review. Thanks to these results, nurse managers could investigate the area of therapeutic education delivery in their units that need improvement. Also, the nurse researchers could imagine projects focusing on the aspects that appear fragile in their context. By optimizing research on this topic, it could be possible to obtain more specific findings to improve clinical practice. For example, future research could use these results to investigate whether the adverse outcome related to discharge decreases by promoting therapeutic education on these topics.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Silvia Rossi, Roberta Tirone and Silvia Scelsi: Conceptualization. Silvia Rossi and Alice Zuco: Data curation and investigation: Silvia Rossi, Alice Zuco, Francesca Tappino and Roberta Tirone: Formal analysis. Silvia Rossi and Silvia Scelsi: Project administration. Mark Hayter and Silvia Scelsi: Supervision. Silvia Rossi and Mark Hayter: Writing—original draft, review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not‐for‐profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee (NR.198/2922–DB id 12324).

Supporting information

Supporting Information S1 and S2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None. Open access funding provided by BIBLIOSAN.

APPENDIX 1. Search strategy for PubMed database.

1.1.

| PUBMED | |

|---|---|

|

P AND |

(“child” OR “children” OR “infant” OR “newborn” OR “premature” OR “adolescent” OR “pediatric”) |

|

E AND |

(“nurse‐led discharge” OR “pediatric discharge” OR “hospital‐to‐home transition” OR “hospital‐to‐home transitions”) |

| O | (“procedure” OR “procedures” OR “programme” OR “programmes” OR “process” OR “activity” OR “activities” OR “intervention” OR “guidelines” OR “experience” OR “experiences” OR “perception” OR “perceptions”) |

| Articles obtained | 91 |

APPENDIX 2. Search strategy for CINAHL complete.

2.1.

| CINAHL complete | |

|---|---|

|

P AND |

(“child” OR “children” OR “infant” OR “newborn” OR “premature” OR “adolescent” OR “pediatric”) |

|

E AND |

(“nurse‐led discharge” OR “pediatric discharge” OR “hospital‐to‐home transition” OR “hospital‐to‐home transitions”) |

| O | (“procedure” OR “procedures” OR “programme” OR “programmes” OR “process” OR “activity” OR “activities” OR “intervention” OR “guidelines” OR “experience” OR “experiences” OR “perception” OR “perceptions”) |

| Articles obtained | 58 |

APPENDIX 3. Search strategy for Web of Science database.

3.1.

| Web of Science | |

|---|---|

|

P AND |

(“child” OR “children” OR “infant” OR “newborn” OR “premature” OR “adolescent” OR “pediatric”) |

|

E AND |

(“nurse‐led discharge” OR “pediatric discharge” OR “hospital‐to‐home transition” OR “hospital‐to‐home transitions”) |

| O | (“procedure” OR “procedures” OR “programme” OR “programmes” OR “process” OR “activity” OR “activities” OR “intervention” OR “guidelines” OR “experience” OR “experiences” OR “perception” OR “perceptions”) |

| Articles obtained | 65 |

APPENDIX 4. PRISMA flow diagram.

4.1.

Rossi, S. , Hayter, M. , Zuco, A. , Tappino, F. , Tirone, R. , & Scelsi, S. (2024). Essential elements nurses have to address to promote a safe discharge in paediatrics: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Nursing Open, 11, e2043. 10.1002/nop2.2043

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Aali, G. , & Shokraneh, F. (2021). No limitations to language, date, publication type, and publication status in search step of systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 133, 165–167. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali Pirani, S. S. (2010). Prevention of delay in the patient discharge process: An emphasis on nurses' role. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development: JNSD: Official Journal of the National Nursing Staff Development Organization, 26(4), E1–E5. 10.1097/NND.0b013e3181b1ba74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger, K. A. , Shah, S. S. , Tubbs‐Cooley, H. L. , Sucharew, H. J. , Gold, J. M. , & Wade‐Murphy, S. (2018). Effects of a 1‐time nurse‐led telephone call after pediatric discharge the H2O II randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics, 172, e181482. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydon, L. , Hauck, Y. , Murdoch, J. , Siu, D. , & Sharp, M. (2018). Transition from hospital to home: Parents perception of their preparation and readiness for discharge with their preterm infant. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27, 269–277. 10.1111/jocn.13883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J. G. , Blaine, K. , Rogers, J. , McBride, S. , Schor, E. , Birmingham, J. , Schuster, M. A. , & Feudtner, C. (2014). A framework of pediatric hospital discharge care informed by legislation, research, and practice. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(10), 955–962. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadia, M. , Golden‐Plotnik, S. , van Manen, M. , Sivakumar, M. , Drendel, A. L. , Poonai, N. , Moir, M. , & Ali, S. (2023). Adolescent and caregiver perspectives on living with a limb fracture: A qualitative study. Pediatric Emergency Care, 39(8), 589–594. 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breneol, S. , Hatty, A. , Bishop, A. , & Curran, J. A. (2018). Nurse‐led discharge in pediatric care: A scoping review. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 41, 60–68. 10.1016/j.pedn.2018.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, M. , Jacobs, L. , & Cazzell, M. (2022). Impact of emergency management in a simulated home environment for caregivers of children who are tracheostomy dependent. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 27(2), e12366. 10.1111/jspn.12366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. , Dai, Y. , Zheng, Y. , Yuan, T. , Dong, G. , Wu, W. , Huang, K. , Yuan, J. , Fu, J. , & Chen, X. (2022). Diabetes education in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes in China. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 51(9), 2017–2026. 10.18502/ijph.v51i9.10556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme . (2021a). CASP (cohort study) checklist. CASP. https://casp‐uk.net/casp‐tools‐checklists/ [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme . (2021b). CASP (case control) checklist. CASP. https://casp‐uk.net/casp‐tools‐checklists/ [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme . (2021c). CASP (qualitative) checklist. CASP. https://casp‐uk.net/casp‐tools‐checklists/ [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme . (2021d). CASP (randomised controlled trial) checklist. CASP. https://casp‐uk.net/casp‐tools‐checklists/ [Google Scholar]

- Desai, A. D. , Durkin, L. K. , Jacob‐Files, E. A. , & Mangione‐Smith, R. (2016). Caregiver perceptions of hospital to home transitions according to medical complexity: A qualitative study. Academic Pediatrics, Children with Special Health Care Needs, 16(2), 136–144. 10.1016/j.acap.2015.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekim, A. , & Ocakci, A. F. (2016). Efficacy of a transition theory‐based discharge planning program for childhood asthma management. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge, 27(2), 70–78. 10.1111/2047-3095.12077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierro, J. , Herrick, H. , Fregene, N. , Khan, A. , Ferro, D. F. , Nelson, M. N. , Brent, C. R. , Bonafide, C. P. , & DeMauro, S. B. (2022). Home pulse oximetry after discharge from a quaternary‐care children's hospital: Prescriber patterns and perspectives. Pediatric Pulmonology, 57(1), 209–216. 10.1002/ppul.25722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garin, C. (2020). Enhanced recovery after surgery in pediatric orthopedics (ERAS‐PO). Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Surgery & Research: OTSR, 106(1S), S101–S107. 10.1016/j.otsr.2019.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick, A. F. , Farkas, J. S. , Nicholson, J. , Dreyer, B. P. , Fears, M. , Bandera, C. , Stolper, T. , Gerber, N. , & Shonna Yin, H. (2017). Parental management of discharge instructions: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 140(2), e20164165. 10.1542/peds.2016-4165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodacre, S. (2006). Safe discharge: An irrational, unhelpful, and unachievable concept. Emergency Medicine Journal: EMJ, 23(10), 753–755. 10.1136/emj.2006.037903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatoun, J. , Bair‐Merritt, M. , Cabral, H. , & Moses, J. (2016). Increasing medication possession at discharge for patients with asthma: The meds‐in‐hand project. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20150461. 10.1542/peds.2015-0461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath, J. , Dancel, R. , & Stephens, J. R. (2015). Post‐discharge phone calls after pediatric hospitalization: An observational study. Hospital Pediatrics, 5(5), 241–248. 10.1542/hpeds.2014-0069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. P. T. , & Green, S. (Eds.). (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. www.handbook.cochrane.org [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America . (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. National Academies Press (U.S.). [Google Scholar]

- Jubic, K. , Dick, E. , & Moelber, C. (2022). A multidisciplinary approach to improving the pediatric discharge process. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 37(3), 206–212. 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyenaar, J. K. , O'Brien, E. R. , Leslie, L. K. , Lindenauer, P. K. , & Mangione‐Smith, R. M. (2017). Families' priorities regarding hospital‐to‐home transitions for children with medical complexity. Pediatrics, 139(1), e20161581. 10.1542/peds.2016-1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, F. , Zhang, G. , Zhao, X. , & Luo, B. (2022). Readiness for hospital discharge in primary caregivers for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 31(21–22), 3213–3221. 10.1111/jocn.16159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallory, L. A. , Osorio, S. N. , Prato, B. S. , DiPace, J. , Schmutter, L. , Soung, P. , Rogers, A. , Woodall, W. J. , Burley, K. , Gage, S. , & Cooperberg, D. (2017). Project IMPACT pilot report: Feasibility of implementing a hospital‐to‐home transition bundle. Pediatrics, 139(3), e20154626. 10.1542/peds.2015-4626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , & Altman, D. G. (2010). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery, 8(5), 336–341. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moo‐Young, J. A. , Sylvester, F. A. , Dancel, R. D. , Galin, S. , Troxler, H. , & Bradford, K. K. (2019). Impact of a quality improvement initiative to optimize the discharge process of pediatric gastroenterology patients at an academic Children's hospital. Pediatric Quality and Safety, 4(5), e213. 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Observatory on Health in the Italian Regions . (2021). Report 2019: State of health and quality of care in the Italian regions . https://www.osservatoriosullasalute.it/osservasalute/rapporto‐osservasalute‐2019

- Page, M. J. , Boutron, I. , Shamseer, L. , Brennan, S. E. , Grimshaw, J. M. , Li, T. , McKenzie, J. E. , Bossuyt, P. M. , Hoffmann, T. C. , Mulrow, C. D. , Tetzlaff, J. M. , Akl, E. A. , Chou, R. , Glanville, J. , Hróbjartsson, A. , Lalu, M. M. , Loder, E. W. , Mayo‐Wilson, E. , McGuinness, L. A. , … McDonald, S. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh, K. , Paul, J. , Fousheé, N. , Waters, D. , Teach, S. J. , & Hinds, P. S. (2018). Barriers and facilitators to asthma care after hospitalization as reported by caregivers, health providers, and school nurses. Hospital Pediatrics, 8(11), 706–717. 10.1542/hpeds.2017-0182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh, K. , Richmond, M. , Lee, M. , Fu, L. , McCarter, R. , Hinds, P. , & Teach, S. J. (2021). Outcomes from a pilot patient‐centered hospital‐to‐home transition program for children hospitalized with asthma. Journal of Asthma, 58(10), 1384–1394. 10.1080/02770903.2020.1795877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra, K. P. , Mains, N. , Dalton, C. , Welsh, J. , Iheonunekwu, C. , Dai, Z. , Murray, P. J. , & Fisher, E. S. (2020). Improving discharge outcomes by using a standardized risk assessment and intervention tool facilitated by advanced pediatric providers. Hospital Pediatrics, 10(2), 173–180. 10.1542/hpeds.2019-0109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay, J. , Roberts, H. , Sowden, A. , Petticrew, M. , Arai, L. , Rodgers, M. , & Britten, N. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Lancaster University. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm, K. P. , Brittan, M. S. , Stephens, J. R. , Mummidi, P. , Steiner, M. J. , Gay, J. C. , Ayubi, S. A. , Gujral, N. , Mittal, V. , Dunn, K. , Chiang, V. , Hall, M. , Blaine, K. , O'Neill, M. , McBride, S. , Rogers, J. , & Berry, J. G. (2018). Issues identified by post‐discharge contact after pediatric hospitalization: A multisite study. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 13(4), 236–242. 10.12788/jhm.2934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarsfield, M. J. , Morley, E. J. , Callahan, J. M. , Grant, W. D. , & Wojcik, S. M. (2013). Evaluation of emergency medicine discharge instructions in pediatric head injury. Pediatric Emergency Care, 29(8), 884–887. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31829ec0d9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shermont, H. , Pignataro, S. , Humphrey, K. , & Bukoye, B. (2016). Reducing pediatric readmissions: Using a discharge bundle combined with teach‐back methodology. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 31, 224–232. 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staveski, S. L. , Parveen, V. P. , Madathil, S. B. , Kools, S. , & Franck, L. S. (2016). Parent education discharge instruction program for care of children at home after cardiac surgery in southern India. Cardiology in the Young, 26(6), 1213–1220. 10.1017/S1047951115002462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, P. K. , Penprase, B. , Kepros, J. P. , & Dunneback, J. (2010). Parental recognition of postconcussive symptoms in children. Journal of Trauma Nursing, 17(4), 178–182. 10.1097/JTN.0b013e3181ff2789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toolaroud, P. B. , Nabovati, E. , Mobayen, M. , Akbari, H. , Feizkhah, A. , Farrahi, R. , & Jeddi, F. R. (2023). Design and usability evaluation of a mobile‐based self‐management application for caregivers of children with severe burns. International Wound Journal, 20(7), 2571–2581. 10.1111/iwj.14127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warembourg, M. , Lonca, N. , Filleron, A. , Tran, T. A. , Knight, M. , Janes, A. , Soulairol, I. , & Leguelinel‐Blache, G. (2020). Assessment of anti‐infective medication adherence in pediatric outpatients. European Journal of Pediatrics, 179(9), 1343–1351. 10.1007/s00431-020-03605-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe . (1998). Therapeutic patient education: Continuing education programs for health care providers in the field of prevention of chronic diseases: Report of a WHO working group. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/108151 [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S. , Tyler, A. , Logsdon, T. , Holmes, N. M. , Balkian, A. , Brittan, M. , Hoover, L. , Martin, S. , Paradis, M. , Sparr‐Perkins, R. , Stanley, T. , Weber, R. , & Saysana, M. (2016). A quality improvement collaborative to improve the discharge process for hospitalized children. Pediatrics, 138(2), e20143604. 10.1542/peds.2014-3604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H. , Roberts, P. A. , & Della, P. R. (2021). Nurse‐caregiver communication of hospital‐to‐home transition information at a tertiary pediatric Hospital in Western Australia: A multi‐stage qualitative descriptive study. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 60, 83–91. 10.1016/j.pedn.2021.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information S1 and S2

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.