Abstract

Behavior-based ergonomics therapy (BBET) has been proposed in the past as a viable individualized non-pharmacological intervention to manage challenging behaviors and promote engagement among long-term care residents diagnosed with Alzheimer’s/dementia. We evaluate the effect of BBET on quality of life and behavioral medication usage in an 18-bed dementia care unit at a not-for-profit continuing care retirement community in West Central Ohio. Comparing a target cohort during the 6-month pre-implementation period with the 6-month post-implementation period, our study indicates that BBET appears to have a positive impact on the resident’s quality of life and also appears to correlate with behavioral medical reduction. For instance, the number of days with behavioral episodes decreased by 53%, the total Minimum Data Set (MDS) mood counts decreased by 70%, and the total MDS behavior counts decreased by 65%. From a medication usage standpoint, the number of pro re nata (PRN) Ativan doses decreased by 57%.

Keywords: non-pharmacological, therapies, quality of life, medications

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia. Caring for a loved one with AD is very difficult, often negatively impacting the primary caregiver’s health and well-being. 1 For this reason, persons with AD and other dementias are frequent users of long-term care facilities. Although placement in a long-term care facility alleviates the primary caregiver of responsibilities associated with activities of daily living (ADLs), such as bathing, dressing, and feeding as well as managing behavioral problems, many still maintain active involvement in the care of their loved ones, hoping to provide them the highest quality of life possible. 2

Active management of AD can significantly improve the quality of life of diagnosed individuals. 1 This includes appropriate uses of all available treatment options, addressing not only medical issues, but also behavioral issues, which are common and challenging for both staff caregivers and visiting family members. In the coming years, as the baby boom generation ages, the number of people diagnosed with AD will increase substantially, making the need to develop a treatment option that addresses the sources of these behavioral issues incredibly important.

Ergonomics examines the interaction between humans and the environment in which they function. The most obvious application of ergonomics addresses physical stresses and focuses on equipment, tool, and space design in order to alleviate these stresses. Another application of ergonomics, often referred to as information or cognitive ergonomics, focuses on mental stress. When overburdened cognitively, people experience mental fatigue that is accompanied by the sensation of weariness and the feeling of being impaired, heavy, and overworked. 3 As a response to physical and cognitive stress, elderly persons with AD exhibit agitated or challenging behaviors as a way of expressing their unmet needs. 4 –7 These behaviors may include, but are certainly not limited to, restlessness, wandering, shadowing, sundowning, and combativeness. 5,6 Stressors that trigger these challenging behaviors can have physical causes, such as hunger, fatigue, and pain, or cognitive causes, such as boredom, disengagement, or dissatisfaction with the surrounding environment. 5 , 6

When persons with dementia exhibit agitated behaviors, they become more prone to falls and injury. Additionally, they increase the stress of caregivers and family members. Although physical restraints have been used in the past to reduce falls, prevent wandering, and manage agitation, concerns regarding the health and humane treatment of impaired individuals have led to a reduction in the use of restraints in long-term care settings. 8 Alternate methods for treating challenging behaviors have included the use of medications, such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, anxiolytics, and benzodiazepines. However, concerns about adverse side effects and drug interactions have raised interest in non-pharmacological interventions. 4

Studies have shown that non-pharmacological interventions can be as effective at reducing disruptive behaviors in persons with AD as psychotropic medications, 9 and research favors the use of individualized, or person-centered, non-pharmacological interventions. 10 Single-center studies have shown that person-centered interventions can reduce the use of psychotropic medications while maintaining or reducing behavioral issues and quality of life of residents 11 ; multicenter studies confirm this finding. 12,13

We have developed and implemented an individualized non-pharmacological intervention, the behavior-based ergonomic therapy (BBET) program, to manage challenging behaviors and promote engagement with long-term care residents diagnosed with AD. The BBET program consists of individualized therapeutic activities that are used as a complement to group activities to proactively address resident stress caused by boredom or disengagement. It is a structured approach to providing multimodal therapies in a customized manner that includes family inputs and 24/7 availability.

The long-term goal of this low-cost BBET program is to reduce cognitive stress and behavioral (or mood-related) issues such as agitation. A pilot study to determine the practical feasibility and effectiveness of this intervention was conducted in a dementia unit in a continuing care retirement community (CCRC) in West Central Ohio. In this article, we analyze the effect the BBET program had on the quality of life and use of medications by residents at this facility. We provide both qualitative and quantitative evidence of the effectiveness of this approach.

Methods

The BBET program was developed in 2009 and implemented in 2010 in conjunction with executives and managers, family members, physicians, nurses, nursing assistants, and other members of an interdisciplinary team at a not-for-profit, religiously affiliated CCRC in West Central Ohio.

Using ergonomics as the basis for the program, BBET employs a unique compilation of interventions to improve a resident’s interaction with his or her environment, in light of the challenges associated with AD or other dementias. The goal of the BBET program is to proactively intervene prior to occurrences of disruptive episodes and prevent future challenging behaviors that are attributed to non-clinical causes such as boredom and disengagement. Through the use of comforting or stimulating interventions that are tailored to each resident’s interests and capabilities, the BBET program addresses the most common unmet needs experienced in a long-term care environment. 11

In addition to disruptive behaviors, the BBET program also addresses withdrawn or passive behaviors. Although typically highly agitated residents receive more attention from caregivers, the BBET program is often used to persuade the quieter residents (including those who are early in the disease and prone to depression) into coming out, instead of hiding in their rooms. Complete details of the BBET program are available in Bharwani et al 14 ; below we summarize the key aspects of this program before sharing details of the pilot study.

The BBET program creates a resident-specific action plan that utilizes over 90 items in order to provide person-centered interventions and activities that are derived from resident profiles and level of cognitive function. This program is not a group activity but a set of individualized and customized activities that are available to the residents 24/7 via facility staff. In contrast to recreational therapists (RTs) who are credentialed activity specialists typically responsible for engaging residents based on a predetermined schedule, all staff (nurses and aids) can administer BBETs as opportunities arise throughout the day and night, with minimal formal training. Because the program is available to residents 24 hours a day via staff, activities can be requested when family members are visiting, allowing family members to also utilize the program in order to enhance their experiences with their loved ones.

The BBET program includes 4 types of interventions that can be classified as either comforting or stimulating. Comforting interventions include music therapy that utilizes portable CD players and a music library, and video therapy that utilizes DVD players and a DVD library. Also included as a comforting intervention is a prop box that securely stores sentimental items (memory props) provided by family members of each resident. These items could be family photos, magazines, books, stuffed animals, and so on. Stimulating interventions, which are designed for residents with medium to high cognitive functioning, include tools from the stimulating library such as stage-specific games and puzzles.

Our observation at long-term care facilities is that the time spent in behavior management is between 10 and 60 minutes per episode, with about 4 to 5 behavior episodes during a day. Because so much time is spent handling behavioral episodes, a proactive approach (ie, the BBET program) was designed to identify triggers of abnormal behavior and managing them. When a nursing assistant observes a resident becoming bored (or disengaged from a group activity), he or she goes to the BBET resource center and selects a therapy item based on the individual resident’s BBET action plan and engages the resident in the therapy. Because the action plan contains options that are customized to the resident’s interests and capabilities, the resident will usually stay engaged on his or her own (without 1:1 attention) after the staff has initiated the therapy (which takes 2-3 minutes of staff time). The staff are trained how to monitor and conclude a therapy. It is important to understand that therapies typically last 30 to 45 minutes but have a lasting calming effect afterward for 2 to 4 hours. The BBET program is generally used 2 to 3 times per resident per day primarily when the staff observe a resident showing signs of mental stress (ie, wandering, repeating questions, shadowing, etc) or before an already known stressor such as a bath or a meal. Total staff time required to manage behaviors through the use of BBET is less than 5 minutes, which is a substantial decrease compared to 10 to 60 minutes previously required to manage a behavior when it occurred.

Pilot Details

The BBET program was implemented at St. Leonard, a nonprofit, religiously affiliated senior living community in West Central Ohio. Situated on 240 acres, the campus consists of 250 cottages/garden homes, a 100-unit tax credit housing development, 83 independent apartments, 74 Joint Commission–accredited assisted living apartments, and a 120-bed Joint Commission–accredited Medicare/Medicaid nursing facility. Eighteen of those beds are dedicated to residents with Alzheimer's/dementia in a secured unit. One nurse and 2 state-tested nursing assistants (STNAs) oversee the unit along with a medical doctor, a geriatric nurse practitioner, and a psychiatrist.

The residents in this Alzheimer's/dementia unit are ambulatory but usually require assistance with meals and other ADLs. Their stay in the unit typically begins while they are medium to high cognitive functioning and ends when they are no longer ambulatory or require extensive physical care to perform ADLs. There are dedicated activity coordinators who facilitate group exercise in the morning and 1 to 2 group activities throughout the rest of the day.

The BBET program pilot was introduced to St. Leonard’s dementia unit on February 18, 2010. The staff quickly became comfortable with the program and by March 1, the staff was initiating BBET interventions by themselves. As the program was not fully functional until March, the February data were excluded from the analysis. The 6 months prior to February, August 2009 through January 2010, were designated as the pre-implementation period and the 6 months following February, March 2010 through August 2010, were designated as the post-implementation period.

Evaluation Measures

Institutional review board (IRB) approval for this study was obtained on July 6, 2011, from Wright State University’s IRB. This study analyzed 2 groups of residents who participated in the BBET program during the pre- and post-implementation periods. The first group was the total hall population. This cohort comprised 39 residents who resided in the dementia unit for any length of time in the pre-implementation period, post-implementation period, or both. A subset of the hall population, the second group or target cohort, comprised 9 residents from the original 39 who resided in the dementia unit for the entire pre- and post-implementation periods, with the exception of 2 residents who resided in the hall for 11 of the 12 months analyzed. All 39 residents participated in the BBET program while they resided in the Alzheimer’s unit. Both groups were analyzed in order to present the effect of the program on both types of individuals receiving treatment: those who received long-term treatment (target cohort) and those who received short-term treatment (hall population).

Because this was a retrospective study, we were limited to analyzing the existing data that were routinely recorded by the St. Leonard’s staff. The information used to analyze the effects of the BBET program included various reports, records, and systems of information, which were kept and maintained at St. Leonard’s facility. These sources included routine medication orders, progress notes, pharmacy data, mood and behavior charting, incident reports, paper charts, and Minimum Data Set (MDS) 2.0 reports.

Typically, quality of life is measured via dementia care mapping. 12,15 However, this assessment was not performed as part of routine care at St. Leonard and therefore was not available for analysis. To evaluate quality of life, we investigated incident reports, MDS 2.0 reports, and medication orders in order to discern quantifiable data. These data included resident falls, MDS 2.0 mood and behavior counts, behavioral episodes, and pro re nata (PRN) usage.

Resident falls were described as the number of incidents where the resident was either witnessed falling to the ground or found on the floor. Behavioral incidents, or those behaviors exhibited by residents that were not normal behavior traits, were documented by staff as they occurred each day and each shift. For example, if a resident wandered around the hall as part of a normal behavior pattern, wandering would not be documented as a behavioral incident for that specific resident. However, if that resident became agitated and began to yell and act aggressively toward staff, yelling would be documented. The individual days that behavioral incidents were observed were defined as behavioral episodes. These documented incidents and behaviors were classified into either behavior or mood categories, which were later used for quarterly MDS reports.

The MDS behavior categories (behavior observations) include the following: wandering, verbal abuse, physical/self-injurious, socially inappropriate, and resisting care. The MDS mood categories that provide indications of depression, anxiety, and sad mood include the following: negative statements, repetitive questions, repetitive verbalization, persistent anger, self-depreciation, unrealistic fears, recurrent statements, health complaints, nonhealth complaints, bad morning mood, insomnia, sad facial expressions, crying/tearfulness, physical movements, activities withdrawal, and reduced social. From these categories, we obtained MDS mood counts and MDS behavior counts, which are the individual behaviors observed during a behavioral incident.

From a medication standpoint, PRN (Ativan) usage was measured as individual doses administered on an as-needed basis outside of normal orders. Because all residents are agitated when they first moved onto the unit, PRN doses administered the first week of a resident’s stay were excluded as well as those associated with medical conditions such as hospice. Additional categories of behavioral medications that were analyzed based on the availability of data included antipsychotics and anxiolytics. For these, we recorded the number of residents who received orders for each type of behavioral medication.

Results

During the pilot study, the number of residents in the unit ranged between 16 and 18. In all, 54% of the hall population was female and 97% was white. The average age of the hall population was 85 years. Of those included in the target cohort, 56% were female and 100% were white. The average age of the target cohort was 88 years old. Typical Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores for all residents in the 600 hall ranged between 4 and 21. Electronic medical records served as the main source of quantitative and qualitative data collection, along with observations from caregivers.

Quality of Life

Figure 1 shows the comparison of pre-implementation and postimplementation quality of life measurements for both the target cohort of 9 residents and the entire hall population of 39 residents. To determine statistical significance, we performed a paired t test on individual data for the target cohort of 9 residents. For the hall population, a t test was performed on the difference between the pre-implementation and post-implementation means in order to determine statistical significance. Table 1 summarizes the cumulative percentage for all residents in their respective cohort.

Figure 1.

Comparison of pre- and post-implementation quality-of-life measurements.

Table 1.

Improvement in Quality-of-Life Measurements.

| Measurement (% reduction) | Target cohort (9 residents) | Hall population (39 residents) |

|---|---|---|

| Resident falls | 33% | 33% |

| MDS mood counts | 70% | 68% |

| MDS behavior counts | 65% | 66% |

| No. of behavioral episodes | 53% | 38% |

For the target cohort, we found that the MDS behavior counts decreased significantly by 65% (p = .0264), while the MDS mood counts decreased substantially by 70% (p = .0704; marginally significant). While there was considerable reduction in the number of behavior episodes (53%) and falls (33%), none of them were found to be statistically significant (p = .1311 and p = .2159, respectively).

For the hall population, the MDS behavior counts decreased significantly by 66% (p = .0121) and the mood counts decreased significantly by 68% (p = .0260). The number of behavioral episodes decreased by 38%, which was marginally significant with p = .0861. The reduction in hall population falls, though considerable at 33%, was not statistically significant (p = .1039).

Medication

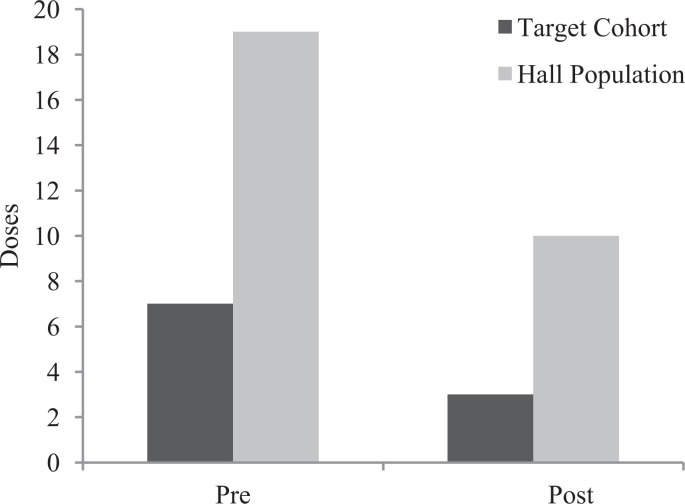

From Figure 2, we observed that PRN Ativan doses decreased considerably by 57% for the target cohort and 47% for the hall populations, but none of these decreases were statistically significant (p = .2794 and p = .1728). The number of residents in the target cohort, who received orders for antipsychotics and anxiolytics, is shown in Table 2. From Table 2, we see that 5 residents were ordered antipsychotics in the pre-implementation period and 4 residents were ordered antipsychotics in the post-implementation period. The number of residents ordered anxiolytics stayed steady at 4 residents in the pre- and post-implementation periods.

Figure 2.

Comparison of pre- and post-implementation PRN (Ativan) usage.

Table 2.

Number of Residents in the Target Cohort Prescribed Each Type of Medication.

| Medication category | Pre-implementation (August 2009 - January 2010) | Post-implementation (March 2010 - August 2010) |

|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotics | 5 | 4 |

| Anxiolytics | 4 | 4 |

Further investigation into the usage/consumption of medication was performed to see whether a reduction in dosages existed. Cumulative milligram of each medication consumed by all residents in the target cohort was totaled in the pre- and post-implementation periods. Antipsychotic medications such as olanzapine and risperidone saw substantial decreases in their consumptions (69.7% and 65.2%, respectively). However, quetiapine saw a small increase in consumption (18.7%). Similarly, anxiolytic medications such as lorenzepam and alprazolam saw reductions of 15.8% and 32.4%, respectively, while buspirone saw a substantial increase of 429%. These results are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Total Cumulative Medication Consumed by the Target Cohort.

| Medication | Pre-implementation (total mg) | Post-implementation (total mg) | % Increase (decrease) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotics | |||

| Zyprexa (olanzapine) | 1520 | 460 | (69.7%) |

| Seroquel (quetiapine) | 19 075 | 22 638 | 18.7% |

| Risperdal (risperidone) | 132 | 46 | (65.2%) |

| Anxiolytics | |||

| Ativan (lorazepam) | 202 | 170 | (15.8%) |

| Buspar (buspirone) | 1528 | 8083 | 429.0% |

| Xanax (alprazolam) | 68 | 46 | (32.4%) |

Staff Observations

According to the staff, there was a noticeable improvement in the agitation levels of residents, which was attributed to the effectiveness of the BBET program. This improvement was perceived to positively impact the quality of life of the residents as well as reduce the amount of medications they were taking. The following are quotes from the staff based on their observations during the pilot:

I think that the BBET program is excellent. This program has created some consistency in the approach to handling behavior problems.—Medical Director

As the staff got to know the BBET program, we stopped getting emergency phone calls.—Geriatric Nurse Practitioner

I feel that the antipsychotic medications have been reduced because the staff is using the BBET program.—Geriatric Nurse Practitioner

I believe there has been a reduction in medication because there is much more focus on using the BBET program to calm the residents.—Unit Manager

Before, I used to have many problems when giving residents a bath. Now I use the BBET program to calm them before giving them a bath.—STNA

One resident loves the music therapy & starts dancing.—STNA

We use BBET a lot before dinner time while they wait for food.—STNA

The BBET program has a calming effect on the residents, and they react to their environment in a more positive way.—Unit Nurse

Discussion

The impact challenging behaviors have on residents is substantial, affecting not only their health, but also their quality of life. Evidence supports the conclusion that there is an increased risk of cerebrovascular adverse events in patients with dementia who are treated with antipsychotics. 6 It is for medical reasons such as this that government regulations have been passed in order to monitor and/or limit the use of antipsychotic drugs. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1987 limits the use of antipsychotic (psychotropic) drugs in nursing homes in order to reduce the medication side effects that lead to the deterioration of medical and cognitive status. 16 Similarly, Medicare’s SOM PP F329 states that, unless medically justified, non-pharmacological interventions should be used in conjunction with a gradual dose reduction in an effort to discontinue the use of antipsychotic medications. 17

Non-pharmacological interventions can help alleviate many challenging behaviors experienced by residents with AD and should be attempted prior to the prescription of psychotropic drugs. 6 , 10 , 13 , 16 Although non-pharmacological interventions will not eliminate the need for medication, the use of these interventions can reduce the need for psychotropic drugs. 7 The implementation of combination interventions like the A.G.E. program (Activities, Guidelines for psychotropic medications and Educational rounds) has been successful 18 in reducing both challenging behaviors and the use of psychotropic drugs. Supporting the use of individualized non-pharmacological interventions, existing research has found that behavior management practices that use these approaches involve fewer medication changes and drug side effects and are no more time consuming than approaches that predominantly use psychotropic medication. 13

The BBET program is one such non-pharmacological intervention that should be used as a first-line treatment in dealing with challenging behaviors from residents with AD. The cumulative quality of life measurements analyzed showed a decrease from the pre-implementation period to the post-implementation period across all measures for both the target cohort and hall population. In general, the target cohort saw larger cumulative reductions than the hall population, but that is to be expected since their data equally spanned both time periods. The reduction in mood and behavior counts was statistically significant for both the target cohort and hall population, indicating that the BBET program helped mitigate the amount of depression, anxiety, and agitation in the lives of these residents. To validate this claim, we interviewed the staff of St. Leonard’s dementia unit to ascertain their opinion of the program. There was an overwhelmingly positive response from all members of staff, from STNAs up to the medical director.

Additionally, the BBET program saw a reduction in the total milligram consumed in 2 out of 3 medications analyzed in both the antipsychotic and anxiolytic categories from the pre-implementation to the post-implementation time periods. The decrease in consumption of lorazepam, alprazolam, risperidone, and olanzapine show a positive movement away from antipsychotic and anxiolytic medications, and toward safer behavioral medications. These observations from the BBET program reinforce the fact that reduction in falls and improvements in resident mood and behavior due to non-pharmacological interventions will tend to reduce the use of behavioral medications. 12 –14 An increase in a few specific medications was also observed. Since we know that pain and clinical issues like infections and drug side effects, which cannot be addressed with non-pharmacological interventions, will tend to temporarily increase the use of behavioral medications 6 it is likely that these were the causes for increase.

Our study has several limitations. First, the pilot was conducted at a single 18-bed dementia unit where only 9 residents were present during both the pre-implementation period and the post-implementation periods. This could limit the generalization; however, the BBET program has since been implemented across the continuum of care in assisted living, independent living, adult day care, and skilled nursing, and the benefits have been seen at all levels of care. Second, given the retrospective nature of this study, our assessment of reduction in agitation levels and improvement in quality of life was based on existing data that were routinely collected and not based on a standardized scale. Using standardized scales to assess quality of life (e.g., dementia care mapping) and agitation level (eg, Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory) would be expected to provide additional quantifiable outcome measures. Third, the significance of the findings through this retrospective pilot study, like many previous studies, may have been affected due to the presence of nonspecific factors that were either difficult to identify or measure. A randomized control trial is preferred, however, may not be practical at every facility.

The results of our research study show that there is empirical evidence to support the conclusion that the BBET program can improve the quality of life of Alzheimer’s residents as is evident in the reduction of falls, MDS behavior and mood counts, number of behavioral episodes, and PRN medications. There is also some evidence, though not conclusive, that supports the claim that the use of the BBET program can reduce routine antipsychotic and anxiolytic medications. However, further controlled studies must be conducted to conclusively validate this claim.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was sponsored by St. Leonard. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the AMDA Foundation and Pfizer for an unrestricted Quality Improvement Award..

References

- 1. Alzheimer's Association. 2010. Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(2):158–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stull D, Cosbey J, Bowman K, McNutt W. Institutionalization: a continuation of family care. J Appl Gerontol. 1997;16:379–402. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pulat B. Fundamentals of Industrial Ergonomics. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cohen-Mansfield J, Libin A, Marx M. Nonpharmacological treatment of agitation: a controlled trial of systematic individualized intervantion. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(8):908–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Camp C, Cohen-Mansfield J, Capezuti E. Use of nonpharmacologic interventions among nursing home residents with dementia. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(11):1397–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gauthier S, Cummings J, Ballard C, et al. Management of behavioral problems in Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(3):346–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beier M. Treatment strategies for the behavioral symptons of Alzheimer's disease: focus on early pharmacologic intervention. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(3):399–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Evans D, Wood J, Lambert L. A review of physical restraint minimization in the acute and residential care settings. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40(6):616–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bird M, Llewellyn Jones R, Korten A, Smithers H. A controlled trial of a predominantly psychosocial approach to BPSD: treating causality. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(5):874–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ayalon L, Gum A, Feliciano L, Arean P. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions for the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(20):2182–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wierman H, Wadland W, Walters M, Kuhn C, Farrington S. Nonpharmacological management of agitation in hospitalized patients with late-stage dementia a pilot study. J Gerontol Nurs. 2011;37(2):44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fossey J, Ballard C, Juszczak E, et al. Effect of enhanced psychosocial care on antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe dementia: cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2006;332(7544):756–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bird M, Llewellyn-Jones R, Korten A. An evaluation of the effectiveness of a case-specific approach to challenging behavior associated with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(1):73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bharwani G, Parikh P, Lawhorne L, VanVlymen E, Bharwani M. Individualized behavior management program for alzheimer's/dementia residents using behavior-based ergonomic therapies. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(3):188–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ballard C, Powell I, James I, et al. Can psychiatric liason reduce neuroleptic use and reduce health service utilization for dementia patients residing in care facilities. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(2):140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gurvich T, Cunningham J. Appropriate use of psychotropic drugs in nursing homes. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(5):1437–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. State Operations Manual: Appendix PP – Guidance to Surveyors for Long Term Care Facilities. http://cms.hhs.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads//som107ap_pp_guidelines_ltcf.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2012.

- 18. Rovner B, Seele C, Yochi S, Folstein M. A randomized trial of dementia care in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(1):7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]