Abstract

This study examined the short-, mid-, and long-term effects of a motor and multisensory care-based approach on (i) the behavior of institutionalized residents with dementia and (ii) care practices according to staff perspective. In all, 6 residents with moderate to severe dementia (mean age 80.83 ± 10.87 years) and 6 staff members (40 ± 10.87 years old) were recruited. Motor and multisensory stimulation strategies were implemented in residents’ morning care. Data were collected with video recordings and focus-group interviews before, immediately after, at 3 months and 6 months after the intervention. The frequency and duration of each resident’s behavior were analyzed. Content analysis was also performed. Results showed short-term improvements in residents’ communication and engagement, followed by a sustained decline over time. Staff reported to change their practices; however, difficulties related to the institution organization were identified. There is a need to implement long-term strategies and involve institutions at different organizational levels to sustain the results.

Keywords: multisensory stimulation, motor stimulation, morning care routines, staff training, residents, dementia

Introduction

Dementia is associated with a progressive deterioration of cognitive functions, changes in behavior and communication problems, 1 , 2 and restrictions in mobility and self-care activities. 3 , 4 As the disease progresses, caring for these patients at home becomes an overwhelming task and care home placement tends to occur. 3 , 5

In residential care homes, the care provided to people with dementia is commonly task oriented, focusing on the instrumental activities of daily living (ADLs) and pharmacological treatment. 6 Currently, good care is associated with person-centered approaches, 6 which in the case of dementia care should include motor, social and multisensory stimulation (often neglected) tailored to each patient’s preferences and needs, 4 , 7 since it promotes psychosocial and physical activity, contributing to delay functional, cognitive and social decline.6–9

Multisensory stimulation (MSS) consists of actively stimulating the primary senses without the involvement of higher cognition processes. 10 This intervention has been found to decrease the frequency of behavioral problems and apathy, 11 , 12 improve residents’ communication 13 and interactions with staff, 10 , 14 and increase residents’ functional performance 15 and attentiveness to the environment. 16 Motor Stimulation (MS) is characterized by structured exercises known to stimulate mobility, improve balance and cognition, reduce falls and functional decline, 17 and delay the progression of the performance decline of ADLs in residents with dementia. 18

These stimulation-oriented approaches (MSS and MS) have been provided to people with dementia, 13 , 17–21 mostly by qualified staff and confined to specialized wards or nursing homes, 2 , 20 , 22 , 23 being scarce in the context of more traditional care homes (where in Portugal most people with dementia are institutionalized), with nonqualified staff. Furthermore, these studies did not examine the long-term effects.

Overall, care staff, who maintain the most direct contact with people with dementia, 24 have insufficient specialized training for providing them care. 25 , 26 Therefore, training care staff to meet specific competencies on dementia has been recommended to (i) improve staff knowledge and skills regarding dementia care 25 , 26 ; (ii) increase residents’ well-being, 27 and (iii) create opportunities for people with dementia to use their resources and abilities in their everyday lives. 28

There are still few research studies which have trained care staff with basic skills to implement MSS 29 or MS 13 in daily care provision to residents with dementia. Furthermore, a scarce number of studies have assessed the impacts of the interventions directly on the residents’ behaviors and on care practices considering staff’s opinions. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the short- (after the intervention), mid- (3 months), and long-term (6 months) effects of a motor and multisensory care-based approach on (i) the behavior of residents with moderate to severe dementia living in a residential care home and (ii) care practices according to staff perspective.

Methods

Design and Setting

A single-group repeated measures design was conducted in a residential care home, in the central region of Portugal. The care home met the following requirements: willingness and agreement to participate in the study, no substantial organizational changes during the study period, and no simultaneous participation in similar studies. The facility included 53 licensed beds for older people and, before the study began, there were 21 residents with a clinical diagnosis of dementia.

Participants

Residents with dementia

In all, 13 residents with dementia were identified by the physician of the residential care home to participate in the study, according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) presenting a clinical diagnosis of moderate to severe dementia, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition; DSM-IV criteria) 30 ; (2) living in the care home for at least 2 months, so adjustments to the new people and environment had been performed; (3) requiring staff assistance during daily care activities; and (4) having no other psychiatric diagnosis. The legal guardian of each resident was contacted, informed about the study, and asked to sign the informed consent. In all, 8 legal guardians signed the written informed consent. However, 1 resident died during the implementation period and other was excluded for refusing to be assessed by video recordings. A total of 6 residents were thus recruited.

Residents (4 females) with a mean age of 80.83 ± 10.87 years (age ranged from 66 to 93 years old) and a clinical diagnosis of moderate to severe dementia participated in the study (Table 1). All participants had moderate to severe cognitive impairment, according to the cutoff scores of the Portuguese version of the Cognitive Impairment Test of the EASYcare. 31 The assessment of global functional ability with the Barthel Index 32 showed that 3 presented high levels of dependency in the ADLs performance, whereas the other 3 revealed moderate to slight dependency (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Residents With Dementia.

| Residents With Dementia (n = 6) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female (n, %) | 4 | 66.7 |

| Male (n, %) | 2 | 33.3 |

| Age | ||

| Mean, SD a (years) | 80.83 | 10.87 |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||

| Moderate dementia, n (%) | 4 | 66.7 |

| Severe dementia, n (%) | 2 | 33.3 |

| Academic qualifications (school years) | ||

| 1-4, n (%) | 5 | 83.3 |

| 7-9, n (%) | 1 | 16.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married, n (%) | 1 | 16.7 |

| Divorced, n (%) | 1 | 16.7 |

| Widowed, n (%) | 4 | 66.7 |

| Cognitive Impairment Test of the EASYcare (0-28 points) | ||

| Mean score, SD a (points) | 20.67 | 6.25 |

| Barthel index (0-100 points) | ||

| 0-20—total dependency a , n (%) | 3 | 50.0 |

| 61-90—moderate dependency a , n (%) | 2 | 33.3 |

| 91-99—slight dependency a , n (%) | 1 | 16.7 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

a According to the interpretation of scores proposed by Shah and colleagues. 57

Care staff

The service manager identified 10 eligible staff participants who maintained direct contact with the residents with dementia during daily care provision. Staff members who were only working at night were excluded as they were not involved in providing morning care. Potential participants were individually informed about the study purposes and invited to participate. Nine agreed to participate. Written informed consent was obtained. Prior to the start of the program, 3 members had to abandon the study (1 due to health problems, 1 for personal reasons, and 1 quitted the job). Thus, 6 staff members, all females with a mean age of 40 ± 11.91 years, ranging from 23 to 51 years participated in the study. Their academic qualifications were primary school (n = 1), 5 to 6 school years (n = 1), 7 to 9 school years (n = 1), secondary school (n = 1), and higher education (n = 2). Half of the sample was working at the care home for more than 3 years (on average 5 ± 5.99 years).

Motor and Multisensory Care-Based Approach

A training program was developed to provide staff with knowledge and skills to introduce MSS and MS to residents’ morning care routines. Morning care was chosen as the recent literature indicates that this is the period of the day where more interaction between staff and resident occurs 33 and problematic behaviors are more frequent. 16 , 33 Morning care was defined as the period of time between 07:00 am and 12:00 am, when staff members are engaged with residents in activities concerning bathing, dressing, grooming, and toileting. 29 , 34

Staff participants received eight 60-minute training sessions, 1 every other week, over a 4-month period. The training was performed in the care home by a multidisciplinary team, which included a gerontologist, a physiotherapist, and a psychologist. The topics of the sessions comprised myths and misconceptions related to dementia syndrome; staff-resident relationships and the importance of understanding the effects of dementia on social and self-care abilities of residents; the relevance of maintaining the remaining abilities and integrate MSS and MS strategies during the provision of personal care according to residents’ sensory stimuli preferences (which were collected by the research team dialoguing with the family and care staff); and verbal and nonverbal communication and other facilitative interaction aspects. The intervention has been presented and described in detail elsewhere. 35 All participants were given handouts which summarized the most relevant information and emphasized the person-centered care.

In the following 3 days after each session, the gerontologist and the physiotherapist assisted staff during the provision of morning care, clarifying doubts and making suggestions to help them implement the MSS (eg, using a fragranced shower gel or playing a relaxing music during the resident’s bath) and the MS strategies (encouraging the person to perform 1 task, or a part of it, eg, washing the arms, removing the foam from the body, by giving him or her small and simple instructions or physical guidance), according to what has been described in Cruz et al. 35 The individual assistance was provided as it has been considered essential to promote practice change 36 and sustain implementation of new knowledge. 2 , 26 , 37

Data Collection

Data were collected at baseline, immediately after, at 3 months, and 6 months after the training program.

Residents’ behavior

The short-, mid-, and long-term effects of the motor and multisensory care-based approach on the behavior of residents with moderate to severe dementia were studied through video recordings of morning care routines. In all, 24 video recordings were collected, 6 in each period of data collection. Prior to data collection, several video recordings were performed to minimize the effects of the camera in the behavior of staff and residents. 38 Furthermore, a rigorous protocol for data collection was defined in advance to minimize reactivity effects, the video camera was fastened to a top of a tripod, placed in the bathroom, and turned on before the resident entered the room; all staff members were instructed to inform the resident about the camera and to ask permission to record; staff members were also instructed to stop or remove the video camera if they noticed any resident’s negative reaction caused by the device presence.

Staff opinions about the motor and multisensory care-based approach

Focus group interviews were also conducted with 5 staff participants at 2 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months after the intervention. One participant missed all the interviews due to personal medical reasons. These interviews were semi-structured and aimed to obtain in-depth staff participants’ opinions about their care practices implementing a motor and multisensory care-based approach (ie, impacts on the care provided, suggestions for future interventions, and difficulties in implementing it into practice). Each interview lasted for approximately 2 hours and was audio-recorded and transcribed.

Data Analysis

Residents’ behavior was studied by analyzing the frequency and duration of a list of behaviors (ethogram). The ethogram was obtained from the previous research 29 , 39 , 40 and preliminary observations of the video recordings. The list comprised 4 categories (Table 2), caregiver-direct gaze, verbal communication, and task engagement (voluntary and solicited).

Table 2.

Categories of the Residents’ Behavior List.

| Categories | Definition |

|---|---|

| Caregiver-direct gaze | The resident looks at the caregiver. |

| Verbal communication | The resident articulates words or sentences with meaning, voluntarily and purposely, in order to communicate with the caregiver. Verbal aggression is excluded. |

| Solicited engagement in the task | The resident moves the body or a body part in order to perform a task, or a part of it, related to the morning care activity (eg, reach the towel, clean up his or her face, and wash a body part). The action is previously solicited by the staff member, through verbal commands or physical guidance. |

| Voluntary engagement in the task | The same as the category above but the action is voluntary, that is, the resident starts to perform the task without any verbal or physical command. |

The video footage was then selected for analysis. It was predefined that the observation time started when both resident and staff member appeared on the screen and it ended when they were both out of reach of the camera. Thus, to follow this criterion and to be able to compare the observational variables between the different participants and across the different phases of the intervention, the video recordings were cut so that all would have the length of the smallest video recording (211 seconds [3 minutes and 31 seconds]). In the longer video recordings it was pre-established that the start of the video recording analyzes would be the beginning of the observation time.

The video recordings were then analyzed by 2 independent observers. The observers rated the residents’ behaviors according to the ethogram using specialized software, Noldus The Observer XT 7.0 (Noldus International Technology, Wageningen, the Netherlands). They were previously trained to use the software by analyzing the video recordings obtained before data collection, and were blinded to the phase of the data collection (baseline, immediately after, 3 months, and 6 months after). The frequency and duration of the categories were measured for each resident in different phases.

Reliability of the observations

One of the major challenges to observational data is collecting reliable information. 41 Therefore, the study of the interobserver reliability was performed for the frequency and duration of each behavior in each phase, using the methods recommended for conducting reliability studies with continuous data, 42 that is, intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) 43 using Equation (2.1), and the Bland and Altman method for assessing the agreement. 44

The ICC (2.1) values (Table 3) ranged between 1.00 and 0.444 for all categories except 2, indicating excellent to moderate reliability. 43 The lower ICC values, 0.283 and 0.377, were found for the frequency of the category voluntary engagement in the task (baseline) and for the frequency of caregiver-direct gaze (3-month follow-up), respectively.

Table 3.

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient and Bland and Altman 95% Limits of Agreement of Residents’ Behaviors at Baseline, Immediately After, 3 and 6 Months After the Implementation of the Motor and Multisensory Care-Based Approach.

| Categories | Period | ICC | ICC 95% CI | SE of | 95% CI for | SD differences | 95% Limits of Agreement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver-direct gaze | Baseline | Freq | 0.62 | −0.18; 0.93 | −0.17 | 0.17 | −0.54; 0.21 | 0.41 | −0.97; 0.63 |

| Dur | 0.80 | 0.19; 0.97 | −0.33 | 0.33 | −1.09; 0.42 | 0.82 | −1.93; 1.27 | ||

| Immediately after | Freq | 0.55 | −0.15; 0.92 | 1.17 | 0.65 | −0.31; 2.65 | 1.60 | −1.97; 4.31 | |

| Dur | 0.64 | −0.09; 0.94 | 3.67 | 2.89 | −2.88; 10.21 | 7.09 | −10.23; 17.56 | ||

| 3 months | Freq | 0.38 | −0.35; 0.87 | −1.50 | 1.09 | −3.96; 0.96 | 2.67 | −6.72; 3.72 | |

| Dur | 0.96 | 0.77; 0.99 | −0.83 | 0.60 | −2.19; 0.53 | 1.47 | −3.72; 2.05 | ||

| 6 months | Freq | 0.69 | −0.26; 0.95 | 0.00 | 0.26 | −0.58; 0.58 | 0.63 | −1.24; 1.24 | |

| Dur | 0.44 | −0.48; 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.42 | −0.62; 1.29 | 1.03 | −1.69; 2.36 | ||

| Verbal communication | Baseline | Freq | 0.97 | 0.83; 0.99 | −0.67 | 0.49 | −1.78; 0.45 | 1.21 | −3.04; 1.71 |

| Dur | 0.95 | 0.71; 0.99 | 6.67 | 5.60 | −5.98; 19.31 | 13.71 | −20.20; 33.53 | ||

| Immediately after | Freq | 0.96 | 0.60; 0.99 | −1.33 | 0.56 | −2.59; −0.07 | 1.37 | −4.01; 1.35 | |

| Dur | 0.99 | 0.91; 0.99 | −2.00 | 1.81 | −6.09; 2.09 | 4.43 | −10.68; 6.68 | ||

| 3 months | Freq | 0.99 | 0.96; 0.99 | −0.33 | 0.33 | −1.09; 0.42 | 0.82 | −1.93; 1.27 | |

| Dur | 0.97 | 0.80; 0.99 | 3.83 | 2.29 | −1.33; 9.00 | 5.60 | −7.14; 14.81 | ||

| 6 months | Freq | 0.97 | 0.85; 0.99 | −0.67 | 0.56 | −1.93; 0.59 | 1.37 | −3.35; 2.01 | |

| Dur | 0.91 | 0.48; 0.99 | 4.67 | 2.70 | −1.44; 10.78 | 6.62 | −8.32; 17.65 | ||

| Solicited engagement in the task | Baseline | Freq | 0.84 | 0.16; 0.98 | 0.50 | 0.22 | −0.00; 1.01 | 0.55 | −0.57; 1.57 |

| Dur | 0.98 | 0.87; 0.99 | 1.67 | 0.96 | −0.49; 3.82 | 2.34 | −2.92; 6.25 | ||

| Immediately after | Freq | 0.97 | 0.83; 0.99 | −0.17 | 0.31 | −0.86; 0.53 | 0.75 | −1.64; 1.31 | |

| Dur | 0.77 | 0.15; 0.96 | −11.17 | 8.28 | −29.88; 7.55 | 20.28 | −50.92; 28.59 | ||

| 3 months | Freq | 0.99 | 0.92; 0.99 | −0.17 | 0.17 | −0.54; 0.21 | 0.41 | −0.97; 0.633 | |

| Dur | 0.82 | 0.19; 0.97 | −12.17 | 6.48 | −26.82; 2.49 | 15.88 | −43.29; 18.96 | ||

| 6 months | Freq | 0.96 | 0.76; 0.99 | −0.17 | 0.17 | −0.54; 0.21 | 0.41 | −0.97; 0.63 | |

| Dur | 0.92 | 0.59; 0.99 | −2.50 | 1.77 | −6.49; 1.49 | 4.32 | −10.98; 5.98 | ||

| Voluntary engagement in the task | Baseline | Freq | 0.28 | −0.64; 0.86 | −1.17 | 1.47 | −4.49; 2.16 | 3.60 | −8.22; 5.89 |

| Dur | 0.74 | −0.07; 0.96 | −7.17 | 13.93 | −38.64; 24.31 | 34.11 | −74.03; 59.70 | ||

| Immediately after | Freq | 0.94 | 0.67; 0.99 | −1.00 | 0.63 | −2.43; 0.43 | 1.55 | −4.04; 2.04 | |

| Dur | 0.96 | 0.78; 0.99 | 2.67 | 5.12 | −8.91; 14.25 | 12.55 | −21.93; 27.26 | ||

| 3 months | Freq | 1.00 | – | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00; 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00; 0.00 | |

| Dur | 0.96 | 0.74; 0.99 | 0.00 | 1.18 | −2.67; 2.67 | 2.90 | −5.68; 5.68 | ||

| 6 months | Freq | 0.82 | 0.25; 0.97 | −0.50 | 0.50 | −1.63; 0.63 | 1.23 | −2.90; 1.90 | |

| Dur | 0.99 | 0.94; 0.99 | −3.50 | 4.35 | −13.33; 6.33 | 10.65 | −12.98; 9.98 | ||

| Total engagement in the task | Baseline | Freq | 0.66 | −0.24; 0.95 | −0.67 | 1.36 | −3.74; 2.40 | 3.33 | −7.19; 5.85 |

| Dur | 0.84 | 0.24; 0.98 | −5.00 | 13.11 | −35.13; 24.13 | 32.12 | −68.45; 57.45 | ||

| Immediately after | Freq | 0.96 | 0.74; 0.99 | −1.17 | 0.65 | −2.65; 0.31 | 1.60 | −4.31; 1.97 | |

| Dur | 0.98 | 0.80; 0.99 | −8.50 | 4.09 | −17.74; 0.74 | 10.02 | −28.13; 11.13 | ||

| 3 months | Freq | 0.99 | 0.97; 0.99 | −0.17 | 0.17 | −0.54; 0.21 | 0.41 | −0.97; 0.63 | |

| Dur | 0.88 | 0.30; 0.98 | −12.17 | 5.59 | −24.81; 0.48 | 13.70 | −39.02; 14.69 | ||

| 6 months | Freq | 0.91 | 0.54; 0.99 | −0.67 | 0.49 | −1.78; 0.45 | 1.21 | −3.04; 1.71 | |

| Dur | 0.99 | 0.93; 0,99 | −4.00 | 2.15 | −8.85; 0.85 | 5.25 | −14.30; 6.30 |

Abbreviations: Freq, frequency; Dur, duration; , mean of the difference; SE of , standard error (SE) of the mean difference: SE = SD differences /√n; 95% confidence intervals (CI) for , ± 2.26SE; SD differences , Standard deviation of the differences; 95% limits of agreement, ± 1.96 × SD differences ; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Bland and Altman 95% limits of agreement were measured and the scatter plots were analyzed for all categories. A good agreement between the observers was found and no systematic bias was seen (see Table 3).

Effects of the motor and multisensory care-based approach on residents’ behavior

Descriptive and inferential analyses of the behavior categories were carried out using the PASW Statistics version 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). The mean frequency and duration of each behavior category was calculated for the descriptive analysis. Differences between the phases of the data collection were analyzed using the nonparametric Friedman test (repeated measures for paired samples). A P value below .05 was considered statistically significant. To be able to measure effect size for each behavior category, Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests were calculated to compare each phase of data collection with the baseline. The equation used was r = |Z|/√N. 45 According to Cohen, 46 a cutoff of r ≥ .1 indicates a small effect, r ≥ .3 a medium, and r ≥ .5 a large effect.

Focus-group interviews

The transcripts were analyzed using qualitative content analysis. The texts were read repeatedly by 2 authors (second and third authors) who acted as independent judges to (i) construct a sense of the text as a whole, (ii) identify meaning units according to the aim of the study, and (iii) condensed the meaning units and clustered them into major categories. Thereafter, a formal meeting was held to compare individual analysis and to agree on final categories and subcategories. Critical feedback was performed by the other authors.

Results

Video Recording Findings

Table 4 presents the changes in residents’ behavior during morning care routines, in the 4 moments of data collection. It is possible to observe an increase in both frequency and duration of caregiver-direct gaze immediately after the intervention and at 3-month follow-up, with a medium effect size for both frequency and duration (r values ranged from .27 to .46); however, this interaction decreased almost to baseline levels after 6 months (r = .28). On the topic of verbal communication, there was a small increase in its frequency immediately after the implementation of the motor and multisensory care-based approach (r = .21), which was maintained 3 months after (r = .15). Nevertheless, the number returned to baseline levels after 6 months (r = .03). As regards to the duration of that behavior, it is possible to observe a sustained decline from baseline to 6-month follow-up (r values ranged from .04 to .21).

Table 4.

Changes in Residents’ Behavior at Baseline, Immediately After, 3 and 6 Months After the Implementation of the Motor and Multisensory Care-Based Approach.

| Categories | Type | Baseline Mean ± SD | Immediately After Mean ± SD | 3 months Mean ± SD | 6 months Mean ± SD | P a (Exact sig.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver-direct gaze | Frequency b | 0.50 ± 0.84 | 1.25 ± 1.67 | 2.83 ± 2.99 | 0.83 ± 0.68 | 0.560 |

| Duration c | 0.67 ± 1.21 | 4.17 ± 7.91 | 4.17 ± 5.74 | 0.83 ± 0.82 | 0.597 | |

| Verbal communication | Frequency b | 6.33 ± 5.29 | 7.33 ± 6.49 | 7.33 ± 6.04 | 6.17 ± 6.21 | 0.795 |

| Duration c | 25.83 ± 42.01 | 20.00 ± 25.65 | 19.42 ± 26.94 | 12.83 ± 16.97 | 0.773 | |

| Solicited engagement in the task | Frequency b | 1.42 ± 1.16 | 2.92 ± 2.92 | 1.58 ± 2.38 | 1.08 ± 1.36 | 0.229 |

| Duration c | 10.00 ± 14.44 | 27.58 ± 29.79 | 26.25 ± 29.28 | 8.25 ± 11.51 | 0.410 | |

| Voluntary engagement in the task | Frequency b | 2.42 ± 2.38 | 3.67 ± 5.06 | 1.33 ± 1.75 | 1.25 ± 1.94 | 0.202 |

| Duration c | 31.58 ± 41.37 | 38.17 ± 42.53 | 7.5 ± 9.26 | 22.92 ± 38.93 | 0.127 | |

| Total engagement in the task (solicited + voluntary) | Frequency b | 3.83 ± 3.50 | 6.58 ± 6.67 | 2.92 ± 4.03 | 2.33 ± 2.93 | 0.120 |

| Duration c | 41.58 ± 51.55 | 65.75 ± 59.23 | 33.75 ± 34.51 | 30.17 ± 49.22 | 0.252 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

a Friedman test.

b Frequency: number of occurrences.

c Duration: length of the behavior (in seconds).

In terms of engagement, the results revealed an increase in residents’ involvement in morning care tasks immediately after the intervention, showing a moderate effect of the intervention (r frequency = .37; r duration = .35). However, this involvement was not maintained over time (r frequency = .27 and r duration = .15 3 months after the intervention; r frequency = .27 and r duration = .27 6 months after). Regarding the category solicited engagement in the task, it is noticeable a great increase in the frequency of that behavior in the post-intervention phase ( r = .35), with a similar decrease 3 months after the intervention (r = .28) which was sustained at 6-month follow-up (r = .19). Still, the duration of that behavior was improved after the intervention and maintained at 3-month follow-up (r = .27 and r = .21 immediately after and 3 months after the intervention, respectively). Nevertheless, the improvement was not observed 6 months after the end of the motor and multisensory-based approach (r = .27). With regard to the residents’ voluntary engagement, it found an improvement in both frequency and duration at the post-intervention phase; a large effect size was found for the duration, r = .53, but not for the frequency, r = .11. Although, a sudden decline was found at 3-month and 6-month follow-up to lower values than the observed at baseline (r values ranged from .23 to .43), no statistically significant differences between the phases were found for any behavior category.

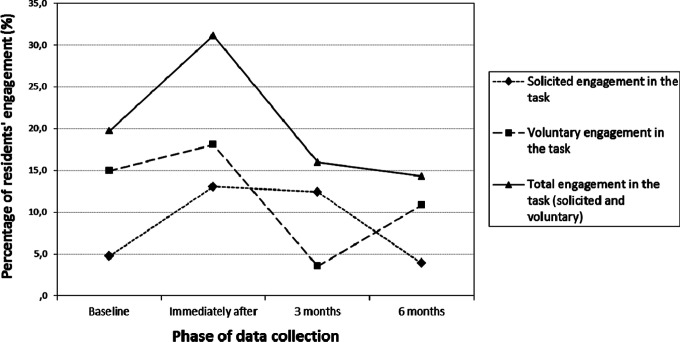

Figure 1 provides information about the percentage of the duration of residents’ engagement in the total observation time of each video recording (ie, 211 seconds). It is possible to observe a considerable increase in the overall engagement in morning care tasks immediately after the intervention (nearly to 10%). However, the 3-month and 6-month follow-up revealed a reduction in residents’ involvement into the values below the baseline levels (from 19.70% at the baseline to 14.30% at 6-month follow-up).

Figure 1.

Percentage of residents’ engagement in the total observation time (211 seconds), in the 4 moments of data collection (baseline, immediately, after 3 and 6 months).

Focus-Group Interviews Findings

From the analyzes of the focus-group interviews several subcategories emerged from the major categories established a priori (ie, impacts of the motor and multisensory care-based approach on the staff care practices, suggestions for future programs, and difficulties in implementing it into practice). An overview of these analyzes over time with examples of staff’s reports can be seen in Table 5.

Table 5.

Overview of the Impacts of the Motor and Multisensory Care-Based Approach Overtime According to the Care Staff Perspective (2 Weeks, 3 Months and 6 Months After). a

| Categories | 2 Weeks After | 3 Months After | 6 Months After |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impacts of the motor and multisensory-based approach on staff care practices | |||

| Demystification of preexistent beliefs associated with dementia | They seem to lose the sensibility to feel the things. I thought they no longer feel the smells… And in that week, almost all residents which I provided care, appeared to have recovered the olfaction! It was great! (C., 27 years old) | I thought they (the residents) were not able to interact, but they actually were! (P., 45 years old) | My initial idea was with these people (…) what am I going to do with them? (…) You gave me the idea that they also know, they also can participate! (P., 45 years old) |

| Awareness for the person-centered care | They were the center of the attentions! Although they were not present in the sessions, they were the main focus … (G., 51 years old) | Motivate them (the residents with dementia) so they can do things, so they don’t forget, (…) We know that there are some things that we will have to do again later, but at least we let them do… (G., 51 years old) | To encourage them to do things, for example, to eat, to drink… To encourage them to have some autonomy, as far as possible. (G., 51 years old) |

| Implementation of the new acquired knowledge into practice | I strove more in my practice every morning! (C., 27 years old) | Active participation. We encourage them to comb their hair, to get up from the bed, to brush their teeth, to wash their hands… (M., 45 years old). Multisensory stimulation. I get the shower and I say ’see if the water is good’ and they go and respond… And I tell them to be aware to the smell in the shower. (G., 51 years old) | Communication skills. The program allowed me to be more aware and helped me to manage the communication between me and the resident (G., 51 years old) |

| Awareness of the impact of implementing the acquired skills in the well-being of all residents | I think that is not only the work with the residents with dementia, but in general, the work with all residents… for example, (…) the way that we react to their calls (…), if we see that resident’s cushion is misplaced… the way staff members react to the welfare of the residents (…) everyday. (G., 51 years old) | ||

| Reflection about practice | Each theme we discussed about made me think… I always tried to put it into practice during the week after the session… (C. 27 years old) | ||

| Motivation to improve practice | This program motivated us to put into practice! (G., 51 years old) | ||

| Suggestions for future programs | |||

| New themes (eg, grief) | …how we deal with the resident that is dying, the peaceful way we have to inform the resident (…)… How to prepare him/her, often we have to dress him/her… And the family, how we manage… there is no preparation at all! (G., 51 years old) | One thing that is missing is how to deal when patients are in a terminal phase … how to deal with death. (M., 45 years old) | |

| Developing the program with the new colleagues | They should receive the training we have received. They should be aware to these factors and problems. They have no training. (G., 51 years old) | The program should be extended to all employees. (M., 45 years old) | |

| Difficulties implementing it into practice | |||

| Lack of time and human resources | In order to do a more comprehensive work, more staff, more time is required … (P., 45 years old) | We need more staff and time, because it takes longer to motivate them (the residents). (P., 45 years old) | We cannot waste much time, we cannot. There are cases that if we could invest more time, we would get more results, no doubt! (G., 51 years old) |

| Lack of availability to help | Each one wants to do their job without helping others. There is no mutual help. (P., 45 years old) | ||

| Lack of support from managers | “The person above us does not know, is not interested…is not present to see staff. We do and recommend, but is the manager that should recommend and say ‘this is how it should be done’. We do not have that power”. (G., 51 years old) | ||

a The gray shade shows when each category emerged.

Impacts of the Motor and Multisensory Care-Based Approach on Staff Care Practices

Some impacts were sustained over time. The staff perceived that the training program allowed them to: (i) demystify preexistent beliefs associated with dementia; (ii) be more conscious to person-centered care, and (iii) be able to implement the new acquired knowledge into practice (eg, active participation, multisensory stimulation, and communication skills). However, only in the focus group conducted 2 weeks after the program, participants reported to be (i) more aware of the impact of implementing the acquired skills on all residents’ well-being (not only those with dementia), (ii) able to reflect about their practice, and (iii) motivated to improve their practice.

Suggestions

Grief was suggested as a new theme to be explored in the future programs. Staff also considered that it would be important to conduct the program with the new admitted colleagues. This was mentioned at 3 and 6 months after the program.

Difficulties

The lack of time and human resources were identified in all focus groups as the major barriers to implement the strategies. In addition, the lack of availability to help was also mentioned at 6 months. In the last focus group, the lack of managers’ support was highlighted as a considerable constraint to the implementation of the intervention.

Discussion

The results showed a trend toward positive short-term effects of the motor and multisensory care-based approach on residents’ behaviors; however, no statistical significant differences were found. The frequency and duration of all behavioral categories increased immediately after the program, with the exception of verbal communication duration. An increase of almost 10% was observed for the duration and frequency of the total engagement of residents in the morning tasks at this point of time. Therefore, this study shows that it is very likely that staff has a significant role in stimulating residents’ verbal and non- verbal communication as well as their engagement in tasks. Similar findings have been found previously. 29 The exception found for verbal communication duration might be explained by the fact that, during the training, staff was encouraged to stimulate residents’ engagement in daily tasks and be aware of the nonverbal communication as an effective way to communicate with these residents. The increase in the frequency and duration of caregiver-direct gaze and residents’ engagement in the task also supports the idea that residents were receptive to the staff’s orientations and were engaging with the environment and therefore, their verbal communication decreased. Engaging residents with dementia in constructive and meaningful activities (eg, brushing their hair, dressing their clothes) has been shown to be beneficial in increasing positive emotions for preventing loneliness, boredom, and problematic behaviors associated with dementia, and improving ADLs and daily function. 47 These promising results may ultimately be translated in residents’ increased mobility and improvements of psychosocial aspects 6 and general quality of life 47 , 48 on day-to-day basis.

However, the duration and frequency of all behavior categories analyzed decreased over time. The declines were already observed at 3 months and levels equal or even below baseline were observed at 6 months. The results from the focus-group interviews might help to interpret these findings. Staff reported to continue to demystify preexistent beliefs associated with dementia, implement the new acquired knowledge, and be aware for the person-centered care. However, simultaneously the lack of: (i) time and resources, (ii) availability to help, and (iii) managers’ support; were identified as the main difficulties to implement the motor and multisensory care-based approach. The time commitment during the morning care to implement this type of interventions has already been raised. 29 However, in dementia care there are only a few moments where real individual contact between residents and staff can occur 29 and morning care is probably the longest and the most important in traditional care homes. In this study, this was not objectively quantified; however, staff were questioned about this aspect and did not perceive that the time needed for morning care had increased due to the intervention. Furthermore, staff reports to continue to implement the new acquired knowledge; however, the results from the video recordings do not confirm this finding. Social desirability might explain this discrepancy.

Therefore, managers should be aware that, although it is important that the staff access formal training on dementia, training alone cannot transform staff’s practices. If the training is to make any sustained impact, it needs to consider care staff experiences 49 and be supported by managers. 50 Managers can, for example, give clear and constructive feedback on care practice, or make sure that staff have enough time to support residents to maximize the use of their own abilities in personal care tasks, 50 which will contribute to sustain results over time. In sum, achievements will only be consolidated if other hierarchical levels besides staff are also involved as they will be the ones to legitimate the introduction of new practices.

Developing the intervention with the new colleagues and adding the theme “grief” were the 2 aspects suggested for future training programs. These suggestions lead us to interpret that the high turnover problematic and the importance to manage emotions should be considered and dealt directly in the training programs. These aspects are well described in the literature, however, often neglected in the design of training programs.

Strengths and Limitations

In this study the effects of the motor and multisensory care-based approach were examined directly on the residents’ behaviors; however, staff opinions were also considered to interpret the findings and inform the development and implementation of future training programs. This leads to a more complete, authentic, and rich exploratory data. 51 This is particularly important as in moderate/severe dementia, the only viable alternative (to measure residents’ well-being) is the direct observation of behavior 39 , 52 and ultimately, the goal of staff training is to improve the care provided to residents with dementia, helping staff translating learning into practice. 49 Therefore, care staff opinions are crucial for the development and implementation of innovative approaches and change in care practices.

Furthermore, few studies have implemented MSS and MS interventions in the residents’ natural contexts 29 but, have used instead special snoezelen rooms 53 , 54 or specific exercises to improve cognitive or physical function, 17 which were added as extras to the residents’ daily routine. This research supports that MSS and MS interventions can be implemented by trained care staff, on a daily routine (bedside, bathroom, etc) and in meaningful activities (brushing the teeth, showering), which facilitates its implementation in institutions with little resources and potentiates its routine use.

Our findings suggest that if MSS and MS are implemented by staff on a daily basis, 29 , 55 according to a person-centered care, considering resident’s preferences (which in this study was obtained dialoguing with the family and staff), it is possible to encourage and improve resident’s communication and engagement.

The few studies that have trained staff to implement MSS 29 MS 13 in daily care provision to residents with dementia had very different durations and yet all reported short-term positive benefits for the residents and/or staff. However, the long-term effects were not examined or in this study were found to deteriorate over time. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that it is not so much the intensity of the intervention (as long as a structured and organized training is provided) that will make a difference, but other strategies need to be explored to help to sustain results such as frequent close follow-up sessions, which will probably need to be a part of each institution policy. This emphasizes the need of involving the organizations as a key element for changing practices, also in dementia care. The role of education and training in care homes and the complexity of promoting and sustaining change has been thoroughly approached by Nolan and his coworkers, 56 however, relatively ignored in the clinical practice. Therefore, not involving the whole organization at its different levels has been a limitation which needs to be acknowledged in this study. Future research should consider this aspect carefully.

Other limitations have to be acknowledged. Given the small sample size, sufficient power was lacking to statistically confirm the differences between the phases; however, effect size for each variable was calculated. Future research with a larger sample, with a control group to provide comparisons, monitoring the organizations, and providing close follow-up sessions is recommended.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian (project reference 100131/FCG/2009).

References

- 1. van der Flier WM, Scheltens P. Epidemiology and risk factors of dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2005;76(suppl 5):v2–v7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Weert JCM, Kerkstra A, van Dulmen AM, Bensing JM, Peter JG, Ribbe MW. The implementation of snoezelen in psychogeriatric care: an evaluation through the eyes of caregivers. Int J Nurs Stud. 2004;41(4):397–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chung PYF, Ellis-Hill C, Coleman PG. Carers perspectives on the activity patterns of people with dementia. Dementia. 2008;7(3):359–381. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kovach CR, Magliocco JS. Late-stage dementia and participation in therapeutic activities. Appl Nurs Res. 1998;11(4):167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Agüero-Torres H, Strauss Ev, Viitanen M, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Institutionalization in the elderly: The role of chronic diseases and dementia. Cross-sectional and longitudinal data from a population-based study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(8):795–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Edvardsson D, Winblad B, Sandman PO. Person-centred care of people with severe Alzheimer's disease: current status and ways forward. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(4):362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. MacDonald C. Back to the real sensory world our “care” has taken away. J Dement Care. 2002;10:33–36. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kolanowski A, Buettner L. Prescribing activities that engage passive residents. An innovative method. J Gerontol Nurs. 2008;34(1):13–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tappen RM, Roach KE, Applegate EB, Stowell P. Effect of a combined walking and conversation intervention on functional mobility of nursing home residents with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2000;14(4):196–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Weert JCM, van Dulmen AM, Bensing JM. What factors affect caregiver communication in psychogeriatric care? In: Visser AM, ed. Alzheimer's Disease: New Research. New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers; 2008:87–117. [Google Scholar]

- 11. van Weert JCM, van Dulmen AM, Spreeuwenberg PMM, Ribbe MW, Bensing JM. Behavioral and mood effects of snoezelen integrated into 24-hour dementia care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(1):24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Verkaik R, Weert JC, Francke AL. The effects of psychosocial methods on depressed, aggressive and apathetic behaviors of people with dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(4):301–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sidani S, LeClerc C, Streiner D. Implementation of the abilities-focused approach to morning care of people with dementia by nursing staff. Int J Older People Nurs. 2009;4(1):48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hope KW, Easby R, Waterman H. ‘Finding the person the disease has' - The case for multisensory environments. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2004;11(5):554–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Collier L, McPherson K, Ellis-Hill C, Staal J, Bucks R. Multisensory stimulation to improve functional performance in moderate to severe dementia—interim results. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(8):698–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Van Weert JCM, Janssen BM, Van Dulmen AM, Spreeuwenberg PMM, Bensing JM, Ribbe MW. Nursing assistants’ behaviour during morning care: effects of the implementation of snoezelen, integrated in 24-hour dementia care. J Adv Nurs 2006;53(6):656–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Christofoletti G, Oliani MM, Gobbi S, Stella F, Bucken Gobbi LT, Renato Canineu P. A controlled clinical trial on the effects of motor intervention on balance and cognition in institutionalized elderly patients with dementia. Clin Rehabil 2008;22(7):618–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rolland Y, Pillard F, Klapouszczak A, et al. Exercise program for nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease: a 1-year randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baker R, Holloway J, Holtkamp CC, et al. Effects of multi-sensory stimulation for people with dementia. J Adv Nurs. 2003;43(5):465–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Milev RV, Kellar T, McLean M, Mileva V, Luthra V, Thompson S, et al. Multisensory stimulation for elderly with dementia: a 24-week single-blind randomized controlled pilot study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;23(4):372–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sidani S, Streiner D, Leclerc C. Evaluating the effectiveness of the abilities-focused approach to morning care of people with dementia. Int J Older People Nurs. 2012;7(1):37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Littbrand H, Lundin-Olsson L, Gustafson Y, Rosendahl E. The effect of a high-intensity functional exercise program on activities of daily living: A randomized controlled trial in residential care facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(10):1741–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Witucki JM, Twibell RS. The effect of sensory stimulation activities on the psychological well being of patients with advanced Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 1997;12(1):10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 24. American Psychiatric Association A. Practice Guideline For The Treatment of Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. Arlington (VA), TX: American Psychiatric Association (APA); 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Beer C, Horner B, Almeida O, et al. Dementia in residential care: education intervention trial (DIRECT); protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2010;11(1):63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kuske B, Hanns S, Luck T, Angermeyer MC, Behrens J, Riedel-Heller SG. Nursing home staff training in dementia care: a systematic review of evaluated programs. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(5):818–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cheung CK, Chow EO. Spilling over strain between elders and their caregivers in Hong Kong. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2006;63(1):73–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alzheimer Europe. Yearbook 2008: Alzheimer Europe; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Weert JCM, van Dulmen AM, Spreeuwenberg PMM, Ribbe MW, Bensing JM. Effects of snoezelen, integrated in 24 h dementia care, on nurse-patient communication during morning care. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;58(3):312–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV-TR - Manual de Diagnóstico e Estatística das Perturbações Mentais. 4th ed. Lisboa, Portugal: Climepsi Editores; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Figueiredo D, Sousa L. Easycare: um instrumento de avaliação da qualidade de vida e bem estar do idoso. Rev Port Med Geriat. 2001;130:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mahoney F, Barthel D. Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sloane PD, Miller LL, Mitchell CM, Rader J, Swafford K, Hiatt SO. Provision of morning care to nursing home residents with dementia: Opportunity for improvement? Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2007;22(5):369–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rogers JC, Holm MB, Burgio LD, et al. Improving morning routines of nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:1049–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cruz J, Marques A, Barbosa AL, Figueiredo D, Sousa L. Effects of a motor and multisensory-based approach on residents with moderate-to-severe dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2011;6(4):282–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McCabe MP, Davison TE, George K. Effectiveness of staff training programs for behavioral problems among older people with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(5):505–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vernooij-Dassen M, Vasse E, Zuidema S, Cohen-Mansfield J, Moyle W. Psychosocial interventions for dementia patients in long-term care. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(7):1121–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Elder JH. Videotaped behavioral observations: enhancing validity and reliability. Appl Nurs Res. 1999;12(4):206–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Perrin T. The positive response schedule for severe dementia. Aging Ment Health. 1997;1(2):184–191. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wood W, Womack J, Hooper B. Dying of boredom: An exploratory case study of time use, apparent affect, and routine activity situations on two Alzheimer’s special care units. Am J Occup Ther. 2009;63(3):337–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ice GH. Technological advances in observational data collection: the advantages and limitations of computer-assisted data collection. Field Methods. 2004;16(3):352–375. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rankin G, Stokes M. Reliability of assessment tools in rehabilitation: an illustration of appropriate statistical analyses. Clin Rehabil. 1998;12(3):187–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fleiss J. Reliability of measurements. In: Fleiss J, ed. The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments. 1 ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1986:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bland MJ, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;327(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hirsch O, Keller H, Albohn-Kühne C, Krones T, Donner-Banzhoff N. Pitfalls in the statistical examination and interpretation of the correspondence between physician and patient satisfaction ratings and their relevance for shared decision making research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011:11–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cohen-Mansfield J, Dakheel-Ali M, Marx MS. Engagement in persons with dementia: the concept and its measurement. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(4):299–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. McGilton KS, Sidani S, Boscart VM, Guruge S, Brown M. The relationship between care providers’ relational behaviors and residents mood and behavior in longterm care settings. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(4):507–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dening T, Milne A. Mental Health and Care Homes: New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Loveday B. Dementia Training in Care Homes. In Mental Health and Care Homes. Great Claredon Street, Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Foss C, Ellefsen B. The value of combining qualitative and quantitative approaches in nursing research by means of method triangulation. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40(2):242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Volicer L, Camberg L, Hurley AC, et al. Dimensions of decreased psychological well-being in advanced dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1999;13(4):192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chung JC, Lai CK. Snoezelen for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2002(4):CD003152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lancioni GE, Cuvo AJ, O'Reilly MF. Snoezelen: an overview of research with people with developmental disabilities and dementia. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(4):175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, et al. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(15):2015–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nolan M, Davies S, Brown J, et al. The role of education and training in achieving change in care homes: a literature review. J Res Nurs. 2008;13(5):411–433. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shah S, Vanclay F, Cooper B. Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42:703–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]