Abstract

Plateau iris syndrome (PIS) was first coined in 1958 to describe the iris configuration of a patient, 2 years later; the concept of plateau iris was published. In 1992, the anatomic aspects of plateau iris were studied using ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) determining it as a form of primary angle-closure glaucoma caused by a large or anteriorly positioned ciliary body that leads to mechanical obstruction of the trabecular meshwork, this condition is most often found in young patients. We aim to review the current literature and knowledge on the diagnosis and treatment options of PIS; the search was conducted in PubMed, LILACS, and BIREME internet search sites using keywords and snowball search strategy of articles published until 2022, focusing on PIS history, epidemiology, clinical diagnosis, UBM feature, and treatment.

Keywords: Iridotomy, plateau iris syndrome, primary angle-closure glaucoma

Introduction

The concept of plateau iris was first coined in a 1960 publication by Shaffer,[1] later in 1970 Kitazawa et al. described a case.[2] Plateau iris is one of the most frequent causes of primary angle-closure glaucoma in young patients; most often, it is diagnosed in patients under 50 years of age with narrow angle despite proper peripheral iridotomy (PI).[3] This form of angle closure is secondary to an anteriorly positioned ciliary body or of greater dimensions that can lead to mechanical obstruction of the trabecular meshwork.[4]

Plateau iris syndrome (PIS) refers to the condition, in which angle closure is still present, confirmed by gonioscopy, despite a peripheral patent iridotomy that has removed a degree of pupillary block and without a shallow anterior chamber.[5]

The syndrome should be differentiated from the plateau iris configuration (PIC). PIC refers to a preoperative condition, in which angle-closure glaucoma is gonioscopically confirmed, but the iris is flat, and the anterior chamber is not axially shallow. In most cases, angle-closure glaucoma due to PIC is not cured by a PI. PIS refers to a postoperative condition, in which a patent iridotomy has removed the relative pupillary block, which is ordinarily important in causing angle closure, but confirmed angle closure is gonioscopically repeated without shallowing of the anterior chamber axially. PIS is rare compared to PIC, which itself is not common.[6]

Epidemiology

Patients with PIC and developing angle-closure glaucoma are younger than those with primary angle-closure glaucoma through the pupillary block (which accounts for 75% of cases). It is commonly seen in women, and the mean age at the first presentation for PIS is 40 years.[7]

In a chart review conducted in the USA including patients under 60 years and recurrent angle-closure symptoms, the prevalence of PIS despite initial iridotomy or iridectomy was 54%.[8] Nevertheless, the prevalence seems to be increased in patients with a family history of PIS, and the predisposition may be of autosomal dominant inheritance pattern according to the findings from a study conducted to assess the prevalence of PIS in the first-degree relatives of patients with PIS, among the ten patients whose living first-degree relatives were screened, five families with at least one additional first-degree family member having PIS were found. In this study, all patients with PIS were followed over a 5-year period. Some families had more than one member with PIS, elucidating that the pattern of inheritance of PIS seems to be autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance.[9]

In a retrospective study that evaluated the angle-closure etiology in young patients, PIS was responsible for the highest frequency of closure revealed in 35 (52.2%) out of the 67 patients with angle-closure glaucoma. Patients with PIS were mostly women (74.3%), young (34.9 years old on average), and less hypermetropic than the patients with pupillary block who, very often, have a family history of angle-closure glaucoma. Excepting younger patients, some elements of the pupillary block are present.[10]

A recent cross-sectional study was published determining the prevalence of plateau iris in primary angle-closure suspects (PACSs) using ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM). Patients over 50 years diagnosed as PACSs were randomized to undergo laser PI in one eye. UBM was performed before and a week after PI. UBM images were qualitatively assessed using standardized criteria. Two hundred and five patients were enrolled; UBM images of 167 patients were available for analysis. Plateau iris was found in 54 out of 167 (32.3%) PACS eyes after PI. Plateau iris was most observed in the superior and inferior quadrants. Using standardized UBM criteria, plateau iris was found in about a third of PACS eyes after PI.[11]

A retrospective study analyzing the UBM images of 228 Brazilian patients was performed to present the prevalence and morphometric findings on eyes of glaucomatous patients with narrow-angle or primary angle-closure glaucoma. One hundred and seventy-one (75%) out of 228 patients were female, and 57 (25%) were male. Twenty-two patients (37 eyes) had PIC, corresponding to the prevalence of 9.6%. Twenty-three (62.2%) eyes of 15 patients had complete PIC, and 14 eyes from 7 patients (37.8%) had incomplete PIC. Two patients (9.1%) had PIS in both eyes. Seventeen (77.3%) out of 22 patients with PIC were female, and 5 (22.7%) were male. No statistically significant difference was found between the morphometric findings of the eyes with complete and incomplete PI except for the iris-ciliary process distance. However, when the comparison between the former and those of normal eyes was made, all parameters of the eyes with PI showed lower values, the statistical differences being highly significant except for Central corneal thickness (CCT) and Iris thickness (IT). The prevalence of PI was 9.6%, much higher in females (77.3%) with a statistically significant difference.[12]

Diagnosis

Plateau iris has been considered an anatomic variant of iris structure, in which the iris root angulates sharply forward from its insertion point and then again angulates sharply and centrally. The surface of the iris appears relatively flat, giving the iris the appearance of a plateau in the sagittal section.[10]

Patients with PIS are often hyperopic, younger than those with primary pupillary block glaucoma, more commonly female, and have a family history of angle-closure glaucoma. The diagnosis may be made on routine examination, or they may present with angle closure spontaneously or after pupillary dilation.[13]

Slit-lamp examination shows standard anterior chamber depth and flat iris surface. Gonioscopy is the golden standard for the assessment of the angle opening. It must be done in a darkroom and with less bright slit beam. On gonioscopic examination, the angle is narrowed or closed. When indentation is performed, the double hump sign (also known as sigma sign) is seen. This sinuous configuration is determined by the ciliary processes that elevate the iris root, the lens curvature that is taken over by the iris surface and the space between them. These changes found in gonioscopic indentation cannot be observed in eyes with primary angle closure due to pupillary block. More force is needed to open the angle on indentation in plateau iris than in pupillary block angle closure because the ciliary processes must be displaced. Besides gonioscopy, the measurement of intraocular pressure (IOP) by tonometry before and after pupillary dilation, after iridotomy has been performed, can indicate residual angle closure from plateau iris.[14]

PIS is defined by persistent occludable angle after patent iridotomy. The height to which the plateau iris rises determines two subtypes of PIS and whether the angle will close completely.[13]

Complete and incomplete plateau iris is defined by the level of the iris relative to Schwalbe's line and the structures of the angle wall.

In complete PIS, the angle is closed to the upper trabecular meshwork or the Schwalbe line, and IOP is increased due to aqueous outflow blocking

In incomplete PIS, the angle is partially closed; the upper trabecular meshwork remains open, allowing drainage of aqueous humor so that the IOP stays between average values.

Patients with incomplete PIS and successful iridotomy can develop peripheral anterior synechiae and angle-closure years after the treatment was initiated.

Ultrasound Biomicroscopy

UBM is an image examination of the anterior segment that plays an important role in plateau iris assessment.

The UBM enabled specialists to anatomically establish the so-called PIC and explain the PIS mechanism in some eyes. Using the UBM, Pavlin et al. studied the anatomic changes of the anterior segment in eight patients with a clinical diagnosis of PIS.[14] In all of them, the ciliary processes were situated anteriorly compared to the position in normal patients and patients with angle-closure glaucoma caused by pupillary block [Figure 1]. The ciliary processes give structural support to the peripheral iris avoiding its withdrawal from the trabecular band after iridotomy. Thus, the anatomic change found in the eyes of these patients is an anterior angulation of the peripheral iris in its insertion in the ciliary body. In some cases, the iris root is short and thick and inserted in a more anterior position in the ciliary body [Figure 2]; anteriorization of the ciliary processes also occurs. There is, thus, an essential narrowing of the angle even though the central depth of the anterior chamber is normal.[15]

Figure 1.

Iris plateau. Elongated ciliary process narrowing the ciliary sulcus

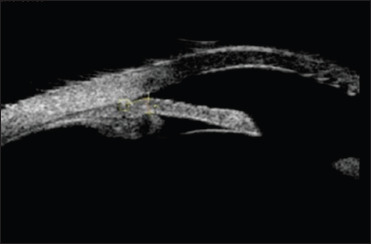

Figure 2.

Iris plateau associated with Thick Iris

An anteriorly directed ciliary body defined plateau iris, an absent ciliary sulcus, a steep iris root from its point of insertion followed by a downward angulation from the corneoscleral wall, presence of a central flat iris plane, and irido-angle contact.[11,14]

A review of measures of the anterior-chamber depth (ACD) in 318 eyes of 318 patients whom UBM had diagnosed as having either pupillary block or PIS was performed. Patients with PIS had previously patent iridotomy. The ACD was measured axially from the internal corneal surface to the lens surface using the ultrasound instrument's internal measuring capability. The literature suggests that patients with PIS have a standard or deeper axial ACD compared with pupillary block. However, this study found that the ACD associated with PIS is shallower than average and shallower than in pupillary block.[16]

UBM not only can reveal classic features of PIS but also shows multiple neuroepithelial cysts of the ciliary body. PIS may be associated with multiple ciliary body cysts, the pseudo-plateau iris [Figures 3-5].[17]

Figure 3.

Pseudo Iris Plateau. Multiple ciliary body cysts

Figure 5.

Iris Plateau configuration associated with iridocorneal sinequia

Figure 4.

Iris plateau associated with Thin iris

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis can be made with:

Pseudo-plateau iris comprises other abnormalities of the ciliary body, such as neuroepithelial cysts or iris cysts that cause the narrowing of the anterior chamber angle. This term does not distinguish between different forms of cysts. The diagnosis can be easily made, as in the case of one cyst; the angle will close focal and be confirmed by imaging techniques[18]

Ciliary body edema has a similar configuration as plateau iris. It is caused by sulfur-containing drugs (topiramate), oral acetazolamide, thalidomide, idiopathic uveal effusion syndrome, increased choroidal venous pressure, or systemic inflammatory disorders[19]

Malignant glaucoma is a subtype of secondary angle-closure glaucoma caused by anterior rotation of the ciliary body. It appears most commonly after filtering surgery due to the aqueous misdirection toward the posterior chamber and vitreous cavity

Ciliary body tumors

Incomplete iridotomy

Gas bubble after vitreoretinal eye surgery.

Treatment

Medical treatment

The medical treatment consists of miotic drug administration: pilocarpine 1%, aceclidine 2% (muscarinic agents), carbachol 0.75% (muscarinic and nicotinic agent), and dapiprazole 0.5% (alpha-adrenergic agonist). These facilitate aqueous humor outflow through ciliary muscle contraction, distance the iris periphery from the trabecular meshwork, and prevent synechiae formation but do not remove iridotrabecular contact.

Miotic agents open the angle reducing the IOP by 20%–25%. Adverse reactions can be local: ocular pain, conjunctival hyperemia, pupillary constriction, myopia, retinal detachment, or general: bronchospasm, headache, and intestinal cramps.[5] This treatment is an option for acute and intermittent angle closure and is mainly reserved for patients who do not consent to laser therapy.[20] Miotics can also be used to prevent angle closure after laser iridotomy or argon laser peripheral iridoplasty (ALPI).[5]

Surgical treatment

PI must always be the first treatment choice. It excludes any associated pupillary block and helps to confirm PIS diagnosis. A patent iridotomy is a prevention procedure that reduces the risk of angle closure. Even after iridotomy has satisfactorily opened the angle, periodic gonioscopy is still essential because the angle may narrow with age, or patients may have incomplete PIS. Patients with PIC must not be assumed to be cured, and PIS may develop years later.[20]

PI procedure can be done with Nd: YAG or argon laser. The lenses used are Abraham (+66D) and wise (+103D). Iridotomy is usually done in the superior quadrant of the iris or an iris crypt. After the iridotomy has been made, it should be horizontally enlarged so that it remains permeable in case of edema, proliferation of pigment epithelial, or pupil dilation.[20]

Nd: YAG laser iridotomy is done using the following parameters: power 1–6 mJ, spot size 50–70 µm, and 1–3 pulses/burst. If the iris is thick and dark, prior treatment with argon laser can be considered.[20]

Argon laser iridotomy is generally done when Nd: YAG laser is unavailable. Parameters are adjusted according to iris thickness and color.[20]

PI complications include hyphemia, visual disturbances (halo and glare), epithelial or endothelial burns, transient elevations of IOP, the emergence of synechia, or closure of iridotomy site.[5]

ALPI is the definitive treatment and the procedure of choice that opens the angle in case of PIS. It is indicated when laser iridotomy is not efficient. ALPI is highly useful in reducing appositional closure of the iris periphery to the trabecular meshwork and opening the angle. This procedure reduces the risk of later synechiae formation.[21]

In rare cases, ALPI can be repeated. Studies that analyzed the iris after ALPI treatment employing spectral domain optical coherence tomography showed that the angle opened where laser burns were applied on the surface of the iris but remained closed in untreated areas. Other studies had suggested that contraction of iris stroma and thinning of the tissue done by ALPI will open the angle, indicating that ALPI technique must be done as far peripheral as possible.[22,23]

Argon laser parameters’ spot size was 200–500 µm, exposure 0.3–0.6 s, and power 200–400 mW. Laser spots must be directed to the peripheral part of the iris. The optimal effect is the contraction of the iris periphery that is visible and flattening of iris curvature; however, possible complications of the procedure are iritis, burns of the corneal endothelium, and atrophy of the iris, IOP elevation, and synechia. Steroid and nonsteroid anti-inflammatory medication can be administered in postlaser management.[22,23]

Alternative treatment procedures are reserved for patients with persistent angle closure despite laser iridotomy and argon peripheral iridoplasty. This can include the following treatment choices: anterior chamber paracentesis (for angle closure glaucoma cases), trabeculectomy (difficult because of possible anterior protrusion of ciliary processes through scleral ostium), goniosynechialysis, lens extraction, shunt implantation surgery, or endophotocoagulation of ciliary processes.[24]

Evolution and Prognosis

Patients with narrow angle and PICs can develop acute or chronic angle closure. These cases need to have periodic follow-up screening for the assessment of an eventual angle narrowing. These patients must be individually evaluated, and the risk between extensive treatment and possible angle closure must be balanced. The prognosis is good in general. Appropriate patient information about a chronic condition that was initially treated with success is essential.[24]

Plateau Iris and Malignant Glaucoma

Some studies report that, in malignant glaucoma, there is an anterior rotation of the ciliary body with the disappearance of the ciliary sulcus on UBM examination, like what is observed in PIC.

To provide evidence for diagnosing malignant glaucoma and elucidating the disease's pathogenetic mechanism of the disease, UBM is a valuable tool. UBM examined the anterior segment of three patients with postoperative malignant glaucoma regarding the state before the operation, the state of the opposite eye, and the state after the release of the ciliolenticular block. Slit-like anterior chamber angle and anteriorly positioned ciliary body were observed in all three cases, which were identical to those that Pavlin reported in eight cases with PIS. UBM seems to be an important preoperative examination to evaluate the risk of malignant glaucoma and to determine which surgical procedure and postoperative management are proper. The preoperative configuration of the ciliary body may be associated with the onset of malignant glaucoma in some patients with chronic angle-closure glaucoma or narrow angle.[25]

Conclusion

Prospective longitudinal studies with large samples aiming at the study and comparison of the morphometric findings in the eyes of normal patients, suspected or confirmed glaucoma patients, with narrow-angle or primary angle-closure glaucoma, with or without PIC and their relationship with malignant glaucoma are required to determine the clinical significance of the actual findings in PIC and PIS patients and to better understand and manage these conditions.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Shaffer RN. Primary glaucomas. Gonioscopy, ophthalmoscopy and perimetry. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1960;64:112–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitazawa K, Nakamura Y, Nakamura C. Case of plateau iris. Ganka. 1970;12:939–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ritch R. Plateau iris is caused by abnormally positioned ciliary processes. J Glaucoma. 1992;1:23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diniz Filho A, Cronemberger S, Mérula RV, Calixto N. Plateau iris. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2008;71:752–8. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27492008000500029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Glaucoma Society Terminology and guidelines for glaucoma, 4th Edition – Chapter 3: Treatment principles and options supported by the EGS foundation: Part 1: Foreword; introduction; glossary; chapter 3 treatment principles and options. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101:130–95. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-EGSguideline.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barkan O. Narrow-angle glaucoma; pupillary block and the narrow-angle mechanism. Am J Ophthalmol. 1954;37:332–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wand M, Grant WM, Simmons RJ, Hutchinson BT. Plateau iris syndrome. Trans Sect Ophthalmol Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1977;83:122–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stieger R, Kniestedt C, Sutter F, Bachmann LM, Stuermer J. Prevalence of plateau iris syndrome in young patients with recurrent angle closure. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;35:409–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2007.01510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Etter JR, Affel EL, Rhee DJ. High prevalence of plateau iris configuration in family members of patients with plateau iris syndrome. J Glaucoma. 2006;15:394–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000212253.79831.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritch R, Chang BM, Liebmann JM. Angle closure in younger patients. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1880–9. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00563-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar RS, Baskaran M, Chew PT, Friedman DS, Handa S, Lavanya R, et al. Prevalence of plateau iris in primary angle closure suspects an ultrasound biomicroscopy study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:430–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cronemberger S, Diniz Filho A, Martins Ferreira D, Calixto N. Prevalence of plateau iris configuration and morphometric findings in patients with narrow angle or primary angle-closure glaucoma on ultrasound biomicroscopic examinations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3863. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiuchi Y, Kanamoto T, Nakamura T. Double hump sign in indentation gonioscopy is correlated with presence of plateau iris configuration regardless of patent iridotomy. J Glaucoma. 2009;18:161–4. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31817d23b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pavlin CJ, Ritch R, Foster FS. Ultrasound biomicroscopy in plateau iris syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;113:390–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran HV, Liebmann JM, Ritch R. Iridociliary apposition in plateau iris syndrome persists after cataract extraction. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:40–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01842-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mandell MA, Pavlin CJ, Weisbrod DJ, Simpson ER. Anterior chamber depth in plateau iris syndrome and pupillary block as measured by ultrasound biomicroscopy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:900–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00578-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azuara-Blanco A, Spaeth GL, Araujo SV, Augsburger JJ, Terebuh AK. Plateau iris syndrome associated with multiple ciliary body cysts. Report of three cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:666–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100130658004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choplin NT, Traverso CE, editors, editors. Colombia: CRC Press; 2014. Atlas of Glaucoma. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quigley HA, Friedman DS, Congdon NG. Possible mechanisms of primary angle-closure and malignant glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2003;12:167–80. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200304000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng WT, Morgan W. Mechanisms and treatment of primary angle closure: A review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;40:e218–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritch R, Tham CC, Lam DS. Argon laser peripheral iridoplasty (ALPI): An update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52:279–88. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu J, Lamba T, Belyea DA. Peripheral laser iridoplasty opens angle in plateau iris by thinning the cross-sectional tissues. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:1895–7. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S47297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parc C, Laloum J, Bergès O. Comparison of optical coherence tomography and ultrasound biomicroscopy for detection of plateau iris. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2010;33:3.e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stefan C, Iliescu DA, Batras M, Timaru CM, De Simone A. Plateau iris – Diagnosis and treatment. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2015;59:14–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ueda J, Sawaguchi S, Kanazawa S, Hara H, Fukuchi T, Watanabe J, et al. Plateau iris configuration as a risk factor for malignant glaucoma. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1997;101:723–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]