Abstract

The purpose of this article is to pinpoint the cultural and ethnic influences on dementia caregiving in Chinese American families through a systemic review and analysis of published research findings. Eighteen publications on Chinese American dementia family caregivers published in peer-reviewed journals between 1990 and early 2011 were identified. Based on a systematic database search and review process, we found that caregivers’ beliefs concerning dementia and the concept of family harmony as evidenced through the practice of filial piety are permeating cultural values, which together affect attitudes toward research and help-seeking behaviors (ie, seeking information on diagnosis and using formal services). There is also evidence to suggest that these cultural beliefs impinge on key elements of the caregiving process, including caregivers’ appraisal of stress, coping strategies, and informal and formal support. The study concludes with recommendations for future research and practice with the Chinese American population.

Keywords: Chinese Americans, family caregiving, dementia, culture

The incremental loss of physical, mental, and social capacities due to dementia puts caregivers on a typically challenging and protracted trajectory. A large body of research documents the deleterious impact of this process on caregivers’ health and well-being. 1 Most of this literature addresses the impact of stress-related caregiving with European Americans. 2 Researchers have also begun to focus on African American and Latino American caregivers in order to identify and understand racial, ethnic, and cultural variations in dementia caregiving. 3,4

The research based on Asian American dementia caregivers and specifically on Chinese Americans is very sparse. 5,6 This knowledge gap is especially troubling as Asian Americans are the fastest growing ethnic group in the United States. The US Census Bureau projects that the proportion of Asian Americans 7 will grow from 5.1% in 2010 to between 7.4% and 9.7% by 2050, while those aged 65 years and older 8 will grow from 9.3% to 21.9%. Chinese Americans are the largest subgroup of Asian Americans and the second largest immigrant group after Mexican Americans. 9 Given the prevalence of Alzheimer’s Disease and related disorders, the sixth leading cause of death for adults aged 65 years and older in the United States, 10 about one quarter million older Chinese Americans in the United States will be equally affected.

Culture in Dementia Caregiving

Research on dementia caregiving is guided largely by Stress and Coping model of Lazarus and Folkman 11 or its topical counterpart, the caregiver Stress Process Model developed by Pearlin and associates. 12 These theoretical models have played a key role in identifying core features of caregiving across ethnic and cultural groups, 13 including contextual factors, primary and secondary stressors and strains, psychological and social mediators, and physical and mental health outcomes. Race/ethnicity is often included as a control variable in these models, but this unidimensional measure does not adequately reflect or explain the role of ethnic or cultural values in the caregiving process. 4,14

To address this shortcoming and advance understanding of the experience of caregivers from underrepresented ethnic groups, Aranda and Knight 15 developed a sociocultural stress and coping model that incorporates ethnic/cultural values in the caregiving process by showing how these values operate through influences on caregiving appraisals of burden, coping, and social support. 14 While not discounting the notion that ethnic/cultural values influence caregivers’ appraisals of their situations, Knight and Sayegh 16 recently noted that the various types of situations and specific stressors which trigger distress might well also differ across ethnic/cultural groups.

The sociocultural stress and coping model appears to be a good fit with Latino caregivers 15 and African American caregivers, 14 but it has yet to be tested with other groups, including Chinese Americans. The development of culturally appropriate models for use with Chinese American caregivers requires a complete understanding of their knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes about dementia and how these factors and core cultural values such as filial piety and family harmony influence their appraisal and coping in the caregiving process. 17

Drawing on the sociocultural stress and coping model, 14,16 we contend that Chinese American dementia caregivers’ behaviors are partly influenced by their cultural values, conceptualized as a collection of values, beliefs, and traditions that define a way of life and provide individual and collective meaning. This systematic review aims to (1) identify the main cultural values that influence Chinese American caregiving and (2) explore how these cultural values affect specific areas of the caregiving experience. We conclude with a discussion of implications for future research and practice.

Methods

Data Source

We reviewed English-language articles published in peer-review journals between 1990 and the first 2 quarters of 2011 using the following databases: PubMed, Psyinfo, Medline, Web of Sciences, and Proquest Dissertations and Theses. Specifically, we selected empirical studies that used a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed method design to examine dementia caregiver experiences using a Chinese American sample. We began with the keywords Chinese Americans, dementia caregiving, Alzheimer’s caregiving, cultural values, and combinations of these terms. We then expanded the search by checking bibliographies of reviewed articles.

We identified 25 studies of Chinese American dementia caregiving; 2 focused on general adults rather than family caregivers 18,19 and 5 were conceptual or review articles that did not otherwise report on empirical data. The remaining 18 studies (17 articles and 1 book chapter) were included for analysis. Our objective was to group, compare, and integrate the findings of these studies. Two investigators read and independently coded articles before reaching consensus on relevant themes. A third investigator provided additional feedback to the review process and theme refinement.

Results

Table 1 describes the main features of the articles we reviewed. All studies used nonprobability sampling; 12 samples were from the Boston area, 5 were from the San Francisco area, and 1 was from the Los Angeles area. Two thirds were grounded in a theoretical or conceptual framework. Ten articles used a qualitative design, including individual interviews, focus group interviews, or field note analysis. The sample size of dementia caregivers ranged from 3 to 25 in qualitative studies and from 45 to 70 in surveys or clinical trials. Ten articles compared Chinese American caregivers with other ethnic/cultural counterparts. Two culturally oriented themes predominated understanding of and beliefs about dementia and familial norms concerning filial piety.

Table 1.

Summary of Articles Reviewed on Dementia Caregiving among Chinese Americans

| Source | Focused topic | Conceptual framework | Design | Participants (N) | Study site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hicks and Lam 20 | Decision making in the dementia caregiving process within a sociocultural context | The model of social process of decision making | Qualitative interviews | Three Chinese American medical professional and 7 Chinese American CGs | Boston area |

| Guo, Levy, Hinton, Weitzman, and Levkoff (2000) 21 | Perceptions of dementia and its impact on the willingness to participant in research by Chinese American dementia CGs | Medical anthropology | Qualitative interviews and field notes of quantitative survey | Total of 16 Chinese American CGs in the qualitative study, 14 in the quantitative study; and 5 service professionals | Boston China town |

| Hinton et al 22 | Sociocultural barriers to recruitment of Chinese American CGs | n/a | Qualitative interviews and field notes | Total of 25 Chinese American CGs | Boston Chinatown and suburb areas |

| Ho et al 23 | Stress and service use in 4 ethnic groups of dementia CGs | Stress and process model of Pearlin et al 12 | Survey | Total of 117 participants and 25 Chinese American CGs | Boston area |

| Levy et al 24 | Dementia attributions and CG burden | Attribution theory | Qualitative interviews | Total of 40 participants and 10 Chinese American CGs | Boston area |

| Dilworth-Anderson and Gibson 17 | Meanings of dementia perceived by 4 ethnic CG groups | Illness meaning in a sociocultural context | Secondary narrative data from semi-structured interviews | Total of 32 participants and 12 Chinese American CGs | Boston area |

| Hinton et al 25 | Pathways to diagnosis of dementia and help-seeking behaviors of 3 ethnic CG groups | Medical sociology and anthropology | Semi-structured qualitative interviews | Total of 39 participants and 14 Chinese American CGs | Greater Boston area, nearby metropolitan areas in Eastern Massachusetts |

| Zhan 26 | Experience of Chinese American Alzheimer’s CGs | n/a | Qualitative interviews | Four Chinese American CGs | Boston Chinatown |

| Hinton et al 27 | Perceptions of dementia in CGs from 4 ethnic groups | Typology of explanatory models | Secondary analysis of narrative data | Total of 92 participants and 22 Chinese American CGs | Boston and San Francisco areas |

| Mahoney et al 6 | Perceptions of the onset and diagnosis of dementia among 3 ethnic CG groups | Leininger’s transcultural model of nursing care | Focus group interviewing | Total of 22 participants and 4 were Chinese American GGs | Boston China town |

| Gallagher-Thompson et al 28 | Effectiveness of 3 recruitment methods of CGs into research | n/a | Quantitative analysis | Candidates, 250;116 Chinese participants contacted and 45 Chinese American CGs enrolled | San Francisco Bay area |

| Gallagher-Thompson et al 29 | Effectiveness of 2 interventions with CGs | Cognitive behavior therapy | Random assignment clinical trial | Forty-five Chinese American CGs completed | San Francisco Bay area |

| Lombardo et al 30 | Interventions for Chinese American families with dementia relatives | Psychosocial counseling and education | Program evaluation | Ten Chinese American CG and patient dyads | Boston |

| Vickrey et al 31 | Similarities and differences in caregiving experience across 4 ethnic groups | n/a | Focus group interviews | Forty-five participants, and 4 Chinese American CGs | UCLA Alzheimer’s research center |

| Liu et al 32 | Stigma and dementia in Chinese and Vietnamese cultures | Goffman’s 3 types of stigma | Narrative study/qualitative interviews | Total of 32 participants and 23 are Chinese American CGs | Boston and Springfield areas of Massachusetts |

| Gray et al 33 | Beliefs about Alzheimer’s disease | n/a | Survey | Total of 215 participants and 48 Chinese American CGs | San Francisco Bay area |

| Gallagher-Thompson et al 34 | Effectiveness of 2 interventions with CGs | Cognitive and behavioral theories | Random clinical trial | Seventy Chinese American CGs (36 in skill training intervention group; 34 in education intervention group) | San Francisco Bay area |

| Holland et al 35 | Dementia CGs’ psychosocial stress and its relations with Asian values | n/a | Survey | Forty-seven Chinese American women CGs | San Francisco Bay area |

Abbreviations: n/a, not applicable; CG, caregiver.

Perceptions of Dementia

Chinese American dementia caregivers incorporated folk models (nonbiomedical terms) into their explanations of dementia. 26 In Chinese culture, Alzheimer's disease and dementia are typically not described as a brain dysfunction as in western culture. 25 Rather, they are depicted in terms of “fate,” “wrongdoing,” “a result of worrying too much,” “craziness,” or “contagious.”

Perceptions of dementia as “normal aging” and as “a stigmatized mental illness” were prevalent attributions among Chinese American caregivers, particularly in early stages of the disease. 21,25 In Chinese culture, a certain degree of cognitive decline at older ages is tolerated and a return to a child-like state is deemed a natural part of aging. 31,32 But as symptoms progress in the more advanced stages of the disease, caregivers’ main concern is stigma. 21,25,31 At this stage, dementia is perceived more often as a mental illness that evokes “craziness” or as a contagion that causes feelings of shame or loss of face. Liu et al 31 used the term “tribal stigma” to describe the extension of humiliating feelings to the entire family.

Family Harmony and Filial Piety

Another major theme in dementia-related caregiving is the failure to adhere to norms of filial piety, which violates the ideal of a harmonious and honorable family. Filial piety, a prominent Confucian principle in Chinese and other Asian cultures, emphasizes honor and devotion to one's parents. This family-centered cultural construct implies that adult children have a responsibility to sacrifice individual physical, financial, and social interests for the benefit of their parents or family. This attitude may be manifested by showing concern for parents' health, providing housing and financial support to parents, and respecting parental authority. 6

Filial piety is bidirectional, prescribing cultural and social norms that dictate how children and their parents ought to treat each other. In exchange for their children's love and respect, parents are expected to provide financial assistance, childcare, and lessons and wisdom gleaned from their life experience. 31 This intergenerational reciprocity is crucial to maintaining familial ties and preserving the family's dignity and sense of honor. 6 A parent’s inability to contribute to and participate in family life due to dementia creates an imbalance of care, leading to shame and disgrace over unfulfilled responsibilities, which in turn may create stigma and resentment, exacerbating an already stressful situation. 33,34

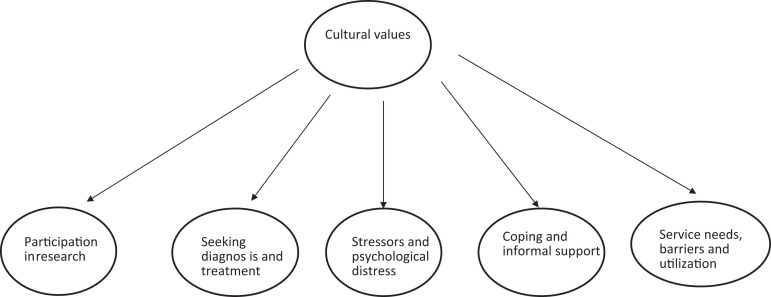

In the articles we reviewed, perceptions of dementia and the concept of family harmony through filial piety influenced caregivers’ willingness to participate in research, an essential activity for building knowledge and improving practice with this population. These cultural constructs also influenced 3 major aspects of the dementia caregiving process, including seeking professional diagnosis and treatment, appraising stress and psychological distress, and coping through informal support and use of formal services (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Themes identified in the 18 articles.

Seeking Diagnosis and Treatment

The ideal pathway to a diagnosis of dementia is believed to begin with the family or patient’s recognition of early symptoms, followed by active help seeking from a primary care doctor who either diagnoses the condition or refers the patient to a specialist. 25 However, culturally related stigma associated with dementia may lead Chinese Americans to delay or avoid seeking professional help; the helping process for these caregivers was more likely to be initiated by health professionals than for European Americans or African Americans. 25 Gray et al 33 also found that Chinese American caregivers’ attribution of symptoms of dementia to normal aging enables them to postpone a diagnosis, often until family resources are exhausted.

Chinese American caregivers who do seek professional help tend to receive a delayed diagnosis or a “no final” diagnosis of dementia. 20,25 Those who visit non-Chinese speaking physicians may experience language barriers which preclude communication of symptoms. 20 On the other hand, cultural barriers appear to outweigh language barriers. Seven Chinese American caregivers in the Boston area reported that Chinese speaking doctors also attributed dementia-related symptoms to normal aging, and thus considered further tests or specialist referrals to be of limited use. Moreover, older Chinese patients may convey respect to their doctors through “deferential silence”20(p422) during their visits.

Caregiving Stressors and Psychological Distress

Cultural beliefs may influence how Chinese American caregivers perceive their caregiving situations and affect their emotional well-being. The attribution of cognitive decline to normal aging can safeguard culturally valued practices of intergenerational interdependence embedded in the principle of filial piety. 17 Such attributions can help to counteract stigma-induced shame and preserve the expectation that adult children will care for their parent. 24

However, the cultural regard of dementia as a stigmatized mental illness can be a serious stressor for Chinese American caregivers. Vickrey et al 31 found that Chinese American caregivers were very concerned about how others in their community react to a diagnosis of dementia for their relative. Negative social responses were especially difficult for Chinese-speaking caregivers who mainly interact within their ethnic community. 26 Caregiving stress can be amplified when family caregivers find social networks diminished because of cultural perceptions of dementia. 32 This is particularly the case when a family member exhibits behavioral problems that can bring shame and embarrassment. 35

Evidence regarding the influence of filial piety on caregiver perceptions of burden and emotional well-being is mixed. In a study of 47 Chinese American female dementia caregivers, Holland et al 35 explored the association of psychosocial factors and levels of diurnal cortisol, a biomarker of levels of health and stress. Caregivers’ belief in Asian cultural beliefs was associated with lower levels of distress, fewer depressive symptoms, greater self-efficacy, and more positive caregiving experiences. The authors conclude that the link of stronger identification with traditional values and lower caregiver burden is due to “a clear expectation and sense of acceptance about their role and duty to a sick elder (particularly daughters and daughters-in-law).”35(p122)

On the other hand, filial piety norms may constitute a source of stress for some Chinese American caregivers, many of whom bring their parents to the United States in order to care for them. Chinese American caregivers were more likely to attribute dementia to immigration or to stressful life conditions after immigration than their counterparts from other ethnic groups, 17,24 compounding existing caregiver stress with additional guilt and concerns.

Family conflict arising from the care of parents with dementia is also a source of stress for Chinese American caregivers. Adult children may be differentially acculturated to US social norms, and as 1 Chinese American caregiver reported in the study of Mahoney et al, 6 stigma caused rejection of a parent with dementia. This resonated with a story told by a daughter caregiver that she had to fight skillfully with her brothers to ensure that their mother was not neglected, a struggle that can be even more trying for Chinese Americans who endorse the cultural belief that institutionalizing a family member is a disgraceful abandonment of family responsibilities. 20 As Dilworth-Anderson and Gibson 17 argue more research should focus on understanding how such cultural meanings affect the stress process for Chinese Americans.

Coping and Informal Support

According to Stress Process Theory, psychological coping and social support are 2 major mediators between caregiving stressors and caregiver well-being. Coping is defined as the behavioral and cognitive strategies that people use to manage stressful life situations. Because there is relatively little a caregiver can do to stop or slow the decline of a family member’s dementia, emotion-focused coping is an important means of managing stress. However, because a dementia diagnosis is often a source of shame in Chinese American families, caregivers may not disclose or share negative emotions and experiences openly or with those they consider “outsiders.” 26 This reticence might contribute to the tendency for some Chinese American caregivers to cope with their distress spiritually. 31 Values of filial piety might also facilitate effective coping. Zhan 26 reported that Chinese American caregivers found good relationships with care recipients; valuing elder care helped them to cope with stressful situations.

Support from informal networks such as families, relatives, friends, or neighbors is critical to family caregivers. Chinese culture dictates that most family caregivers are either spouses or adult children. There is some evidence that there is a lack of sufficient family support for these caregivers. 26 As noted, some relatives or friends might sever contact with the family of a dementia patient to avoid being stigmatized, 6,26 while others who are more acculturated to American values may be unwilling to assume care responsibilities. A Chinese American caregiver in the study of Dilworth-Anderson and Gibson , 17 for example, described his frustration with his son, who appeared to reject a role in the caregiving process.

Formal Service Needs, Barriers, and Utilization

The service needs of Chinese American dementia caregivers are similar to those of caregivers in other ethnic/cultural groups, 23 but Chinese American caregivers have higher levels of unmet need, particularly in the areas of medical and mental health services. Internal barriers to service use include shame and stigma which contribute to delayed help seeking and embarrassment about not knowing English or how best to work within the health care system. 23,33

External barriers can include a paucity of culturally competent services targeting the needs of Chinese American caregivers. 26 In a focus group study by Vickery et al 31 , Chinese American caregivers experienced frustration with the absence of information published in Chinese and expressed a lack of trust in service professionals. Similarly, Chinese American caregivers were found to expect physicians to develop a personal and trusting relationship with the patient and family, rather than just diagnosing them and leaving them to worry. 6 Finally, caregivers also noted negative interactions with service providers as a barrier to their help seeking. 26

Culturally Competent Interventions

Three studies provided evidence of effective interventions to reduce depressive symptoms and relieve stress among Chinese American family caregivers: an in-home behavioral management program, 29 psychoeducation skills training using a DVD, 34 and individualized counseling and support. 30

Chinese cultural values are central to these interventions. In part because of the stigma of dementia as a mental illness, Chinese caregivers tend to hold a negative attitude toward psychotherapy. Gallagher-Thompson et al 29 integrated cognitive behavioral therapy into a psychoeducation format to circumvent this type of resistance. To further ensure access and protect family privacy, interventions were designed for home delivery. Lombardo et al 30 allowed program staff to vary the length of home visits to accommodate the needs of families who were reluctant to meet them and wanted shorter sessions. To avoid the embarrassment of having a stranger come to caregivers’ homes, Gallagher-Thompson et al 34 recently adopted a DVD format to deliver the intervention.

In addition to the mode of delivery, intervention contents were tailored to Chinese cultural values. Interventionists were bilingual and either bicultural or trained in Chinese cultural values that influence dementia caregiving before implementing the intervention. 29,30 For example, in the session on communicating with care recipients, terms like “assertiveness training,” which may convey disrespect for the patient, especially if the caregiver is an adult child, were avoided. 29

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to examine existing empirical literature to determine how cultural values influence dementia caregiving processes among Chinese Americans. Our findings suggest that cultural beliefs and attitudes about dementia and cultural norms about family harmony as achieved through the practice of filial piety are key elements. These 2 themes appear to affect Chinese American caregivers’ attitudes toward participation in research and contribute to caregiving stress in terms of help seeking for diagnosis and treatment, stress appraisal, psychological and social coping, including informal and formal service use, and well-being outcomes.

In interpreting existing studies with this population, it should be noted that Chinese American caregivers’ cultural beliefs also influenced their attitudes toward research participation. The low rates of enrollment in research among Chinese Americans are related to their beliefs about dementia. 22,28 Patients in early stages of dementia do not require clinical or research attention because mild cognitive impairment is viewed as part of the normal aging process. At more advanced disease stages, refusal to join research projects stemmed from a struggle to contain news of the illness with the family due to stigma. 22

The stigma of dementia appears to inhibit caregivers’ openness about their experiences with outsiders. Recruitment through informal networks often offers a viable sampling alternative. However, 62% of European American caregivers were referred by nonprofessionals to the dementia caregiver study by Gallagher-Thompson et al 24 compared with only 15% of Chinese American caregivers, over half of whom were referred by health professionals. The small samples in quantitative and qualitative studies with Chinese American caregivers to date may be due, at least in part, to such culturally rooted recruitment challenges, and self-exclusion may create significant bias. To improve confidence in research findings, culturally appropriate methods for recruiting larger and more representative samples must be accomplished.

There is some empirical evidence that cultural beliefs about dementia and the practice of filial piety influence caregiving distress among Chinese American caregivers. The specific effects of cultural beliefs appear to vary. The conceptualization of dementia as a normal part of aging tends to be linked with lower levels of caregiver distress, presumably because it normalizes the expectations for caregivers. In contrast, stigma associated with dementia may exacerbate stress by generating disgrace and shame.

Evidence on the influence of filial piety is mixed. In the context of dementia care, this concept broadens the scope of responsibility for family caregivers, particularly adult children. At some levels, filial piety may buffer stress by mobilizing and obligating other family members to provide assistance, lowering individual caregiver burden. 36 Holland et al 28 found that belief in Asian cultural values (eg, filial piety) is associated with lower levels of anxiety and burden in female Chinese American caregivers. The same pattern was found in a sample of family caregivers in Taiwan. 37

The price of fulfilling cultural obligations of dementia caregiving may ultimately be stress and burnout, as research shows that levels of acceptance and identification with cultural norms influence caregivers’ perception of burden. Resulting family conflict or lack of supportive family members can be devastating for caregivers. 36 A study with female Chinese Canadian dementia caregivers found that intergenerational tension due to different levels of acculturation to western values caused extra burden. 23 Also, while Chinese American caregivers may report fewer depressive symptoms than European Americans, they tend to somatize emotional distress. 38

Coping, informal support, and formal services are grouped as caregiver resources. Knight and Sayegh 16 argue that cultural values are most likely to affect caregivers’ physical and mental health through such resources. But our review suggests insufficient evidence on the relationship between coping and culture among Chinese American caregivers. Folkman and Lazarus 39 conceptualize coping as emotion focused (helping one to deal with reactions to stressors) or problem focused (directly impacting the source of stress). There is no research on how cultural values may help shape coping among Chinese American caregivers, although using strategies such as spirituality, problem solving, and avoidance have been noted. 31,35

Studies comparing coping strategies of caregivers in Shanghai, China, and their counterparts (mostly European Americans) in San Diego, California, found similarities and differences. 13,40 For example, Chinese caregivers were less likely to use emotionally expressive coping strategies and more likely to use cognitive confronting (eg, “I just accept it”), while the US caregivers used more social support (eg, “Ask someone for help”). Other studies found that both groups appear to benefit from problem-focused coping. 37,41 It is unclear how findings from these studies might apply to Chinese American caregivers.

There is also insufficient evidence to support a conclusion about the effects of cultural values on informal support. Family support is critical to Chinese American caregivers, but there is no evidence that they have more available family support. Indeed, family support could be compromised due to stigma or different levels of acculturation.

There is abundant evidence that cultural values influence Chinese American caregivers’ access to and use of formal services. Challenges to access include language, lack of awareness of programs, reluctance to seek help outside of the family due to stigma and traditional values, and a dearth of culturally competent services, education, and information. Few western interventions account for Chinese Americans' unique experiences, perspectives on family and health care, and cultural traditions, expectations, and values. As a result, these caregivers must manage the disparate, and at times conflicting, beliefs and realities of 2 cultures with inadequate resources and services. Collaborative culturally tailored research and programming with service agencies, policymakers, and Chinese American communities is needed to meet the growing demand for dementia care services and to ensure effective coping and improved outcomes for patients and their caregivers. 42

Recommendations for Future Research and Practice

There are clearly significant gaps in the literature on the experience and needs of Chinese American caregivers of persons with dementia. This review of studies suggests several directions for future inquiry. Further studies need to examine experience of dementia-related stigma in relation to family dynamics and social norms in Chinese American communities. One such study examined the impact of embarrassment on Alzheimer's disease caregivers in a multiethnic sample. 43 It was pointed out that social discrediting (stigma) can differ depending on whether people know the person with dementia—and stigmatization has already occurred—or do not know the person with dementia and the potential for stigma still exists.

To illustrate, a caregiver may avoid inviting guests to home although they already know the patient's diagnosis. The same caregiver may experience a different kind of distress when taking the patient out in public. It is important to understand conditions of social embarrassment for Chinese American caregivers as they affect delayed help seeking, reduced social supports, and barriers to dementia-related resources and services.

In-depth study of family dynamics, for example, changing roles, effects of acculturation, and experiences of cohesion and conflict, could improve understanding of how the stress process unfolds for Chinese American dementia caregivers and could contribute to culturally appropriate assessment and intervention protocols to strengthen caregivers’ social and psychological coping repertoires. Research is also needed on appropriate assessment and evaluation instruments.

Most dementia studies use scales with forced choice response sets, such as Caregiving Coping measures 12 or the Ways of Coping Checklist 39 to assess coping. An open-ended narrative approach could be very useful for soliciting dementia caregivers’ perspectives and for understanding dynamics of coping in this population since standardized inventories do not permit caregivers to share the meaning behind their choices of coping strategies. 44,45 Hicks and Lam 20 suggest that Chinese American caregivers draw on a variety of different cultural paradigms to turn situations to their advantage. It will be important to identify and support such innovative coping strategies.

Finally, Meuser and Marwit 46 pointed out that the gradual loss of a loved one's memory and personal identity due to dementia generates unique stress associated with present and anticipated loss. Chinese cultural norms eschew open discussion of death and illness, so caregivers’ feelings of grief and loss may not be acknowledged, an oversight that might further contribute to feelings of stress, burden, and burnout.

Findings of this review also have several implications for service professionals who work with Chinese American caregivers. Service professionals need to be aware of the cultural stigma attached to dementia and to avoid speech and actions that might cause shame or embarrassment for patients and caregivers. Werner et al 47 recommended that management of stigma beliefs be included in any intervention program for family caregivers and that professional associations and the media be used to educate people in the community. Because Chinese American caregivers and patients tend to regard dementia-related symptoms as part of normal aging, professionals also need to be proactive in detecting and assessing patients’ current and changing levels of cognitive functioning. Training of service professionals not only should focus on recognition of dementia symptoms but also on effective strategies to respond to individual patient’s needs following diagoansis. 48 Service providers should also be aware of the considerable diversity within Chinese American dementia caregivers in terms of socioeconomic status and levels of education and acculturation and should assess their cultural beliefs regarding dementia and their adherence to traditional cultural values such as filial piety.

Several limitations of this review need to be noted. We were limited by the relatively small number of articles identified and the wide-ranging nature of these studies. We were able to identify some consistent findings from this small body of literature that varied much in research design, variables levels of rigor, samples, and study sites, but these themes may not be considered as definitive conclusions. Future controlled trials and subsequent meta-analyses are needed to strengthen this nascent knowledge base and to develop a range of evidence-based interventions for dementia caregivers in Chinese American families.

Conclusion

Psychosocial research on caregiving for persons with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias has increased dramatically in an effort to keep pace with the increasing prevalence of these diseases in a rapidly aging population. Similarly, research on aging populations has turned concerted attention toward ameliorating racial/ethnic disparities in the prevention and intervention. Yet, there has been little attention to the Chinese American experience of dementia caregiving, so knowledge about the process and outcomes of the caregiving process on caregivers and their afflicted family members remains limited. Also noteworthy, virtually all the studies reviewed for this article were situated in coastal urban areas where most Chinese Americans settle. Future studies should also account for less-integrated Chinese American communities, including those in rural areas, where caregiving challenges are likely to be compounded by geographic, linguistic, and cultural isolation.

Thus, there is a clear and compelling need for a program of rigorous research that will meaningfully incorporate Chinese cultural and family values in order to inform better practices with this population. Studies to date suggest that a complete examination of the experience of dementia-related stigma, the effects of dementia caregiving on family dynamics and caregiver coping, and the dementia-specific trajectory of grief and loss are promising avenues to pursue.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Schulz R, Martire L. Family caregiving of persons with dementia prevalence, health effects, and support strategies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12(3):240–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cox CB. Culture and dementia. In: Cox CB, ed. Dementia and Social Work Practice: Research and Interventions. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2007:173–187. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haley WE, Gitlin LN, Wisniewski SR, et al. Well-being, appraisal, and coping in African-American and Caucasian dementia caregivers: findings from the REACH study. Aging Ment Health. 2004;8(4):316–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hilgeman MM, Durkin DW, Sun F, et al. Testing a theoretical model of the stress process in Alzheimer’s caregivers with race as a moderator. Gerontologist. 2009;49(2):248–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Janevic MR, Connell CM. Racial, ethnic and cultural differences in the dementia caregiving experience: recent findings. Gerontologist. 2001;41(3):334–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mahoney DF, Cloutterbuck J, Neary S, Zhan L. African American, Chinese, and Latino family caregivers’ impressions of the onset and diagnosis of dementia: cross-cultural similarities and differences. Gerontologist. 2005;45(6):783–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Day CJ. Population Projections of the United States by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 1995 to 2050, U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports, P25-1130. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1999. http://www.census.gov/prod/1/pop/p25-1130.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. The next four decades: the older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. 2010. http://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p25-1138.pdf.2010. Accessed June 20, 2011.

- 9. U.S. Census Bureau. The American Community-Asians: 2004. 2007. http://www.census.gov/prod/2007pubs/acs-05.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2011.

- 10. Alzheimer’s Association. What is Alzheimer’s? 2009. http://www.alz.org. Accessed May 2, 2011.

- 11. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30(5):583–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Patterson TL, Semple SJ, Shaw WS, et al. The cultural context of caregiving: a comparison of Alzheimer’s caregivers in Shanghai, China and San Diego, California. Psychol Med. 1998;28(5):1071–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Knight BG, Silverstein M, McCallum TJ, Fox LS. A sociocultural stress and coping model for mental health outcomes among African American caregivers in southern California. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000;55(3):142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aranda MP, Knight BG. The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: a sociocultural review and analysis. Gerontologist. 1997;37(3):342–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Knight BG, Sayegh P. Cultural values and caregiving: the updated sociocultural stress and coping model. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65B(1):5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dilworth-Anderson P, Gibson BE. The cultural influence of values, norms, meanings, and perceptions in understanding dementia in ethnic minorities. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002;16(suppl 2):S56–S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chow TW, Ross L, Fox P, Cummings JL, Lin K. Utilization of Alzheimer’s disease community resources by Asian-Americans in California. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(9):838–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jones RS, Chow TW, Gatz M. Asian Americans and Alzheimer's disease: assimilation, culture and beliefs. J Aging Stud. 2006;20(1):11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hicks MH, Lam MS. Decision-making within the social course of dementia: accounts by Chinese-American caregivers. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1999;23(4):415–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guo Z, Levy BR, Hinton WL, Witzman PF, Levkoff SE. The power of labels: Recruiting dementia-affected Chinese American elders and their caregivers. J Ment Health Aging. 2000;6(1):103–112. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hinton L, Guo Z, Hillygus J, Levkoff S. Working with culture: a qualitative analysis of barriers to the recruitment of Chinese-American family caregivers for dementia research. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2000;15(2):119–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ho CJ, Weitzman PF, Cui X, Levkoff SE. Stress and service use among minority caregivers to elders with dementia. J Gerontal Soc Work. 2000;33:67–88. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Levy B, Hillygus J, Lui B, Levkoff S. The relationship between illness attributions and caregiver burden: a cross-cultural analysis. J Ment Health Aging. 2000;6(3):213–225. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hinton L, Franz C, Friend J. Pathways to dementia diagnosis: evidence for cross-ethnic differences. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18(3):134–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhan L. Caring for family members with Alzheimer’s disease: perspectives from Chinese American caregivers. J Gerontol Nurs. 2004;30(8):19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hinton L, Franz CE, Yeo G, Levkoff SE. Conceptions of dementia in a multiethnic sample of family caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(8):1405–1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gallagher-Thompson D, Rabinowitz Y, Tang PC, et al. Recruiting Chinese Americans for dementia caregiver intervention research: suggestions for success. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(8):676–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gallagher-Thompson D, Gray HL, Yang PCY, et al. Impact of in-home behavioral management versus telephone support to reduce depressive symptoms and perceived stress in Chinese caregivers: results of a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(5):425–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lombardo NE, Wu B, Chang K, Hohnstein JK. Model dementia care programs for Asian Americans. In: Cox C, ed. Dementia and Social Work Practice: Research and Interventions. New York, NY: Springer Publishers; 2007:205–229. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vickrey BG, Strickland TL, Fitten LJ, Adams GR, Ortiz F, Hays RD. Ethnic variations in dementia caregiving experiences. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2007;15(2-3):233–249. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu D, Hinton L, Tran C, Hinton D, Barker JC. Reexamining the relationships among dementia, stigma, and aging in immigrant Chinese and Vietnamese family caregivers. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2008;23(3):283–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gray HL, Jimenez DE, Cucciare MA, Tong HQ, Gallagher-Thompson D. Ethnic differences in beliefs regarding Alzheimer disease among dementia family caregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(11):925–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gallagher-Thompson D, Wang PC, Liu W, et al. Effectiveness of a psychosocial skill training DVD program to reduce stress in Chinese American dementia caregivers: results of a preliminary study. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(3):263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Holland JM, Thompson LW, Tzuang M, Gallagher-Thompson D. Psychosocial factors among Chinese American women dementia caregivers and their association with salivary cortisol: results of an exploratory study. Ageing Int. 2010;35:109–127. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lai DWL. Filial piety, caregiving appraisal, and caregiving burden. Res Aging. 2009;32(2):200–223. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chou KR, LaMontagne LL, Hepworth JT. Burden experienced by caregivers of relatives with dementia in Taiwan. Nurs Res. 1999;48(4):206–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Braun K, Browne C. Perceptions of dementia, caregiving, and help seeking among Asian and Pacific Islander Americans. Health Soc Work.1998;23(4):262–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Manual for the Ways of Coping Questionnaire: Research Edition. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shaw WS, Patterson TL, Semple SJ, et al. A cross-cultural validation of coping strategies and their associations with caregiving distress. Gerontologist. 1997;37(4):490–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fortinsky RH, Kercher K, Burant C. Measurement and correlates of family caregiver self-efficacy for managing dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2002;6(2):153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu B, Emerson-Lombardo NB, Chang K. Dementia care programs and services for Chinese Americans in the U.S. Ageing Int. 2010;35(2):128–141. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Montoro-Rodriguez J, Kosloski K, Kercher K, Montgomery RJV. The impact of social embarrassment on caregiving distress in a multicultural sample of caregivers. J Appl Gerontol. 2009;28(2):195–217. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gottlieb BH, Gignac MAM. Content and domain specificity of coping among family caregivers of persons with dementia. J Aging Stud. 1996;10(2):137–155. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Folkman S. Questions, answers, issues, and next steps in stress and coping research. Eur Psychol. 2009;14(1):72–77. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Meuser TM, Marwit SJ. A comprehensive, stage-sensitive model of grief in dementia caregiving. Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):658–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Werner P, Goldstein D, Buchbinder E. Subjective experience of family stigma as reported by children of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(2):159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Iliffe S, Manthorpe J. The recognition of and response to dementia in the community: lessons for professional development. Learn Health Soc Care. 2004;3(1):5–16. [Google Scholar]