Abstract

Objectives: To estimate long-term care costs and disease progression among Medicare beneficiaries aged 65+ with ADRD. Methods: Retrospective analysis of Medicare Part A claims and nursing home (NH) Minimum Data Set (MDS) records among beneficiaries 1999-2007. Expenditures were grouped into 3 periods; PRE, events occurring between date of ADRD diagnosis, before first NH admission; PERI, from first NH admission to at least 100 days; and, PERM, after 120 days. Utilization and reimbursements were computed for each period. Results: Demographics of the3,681,702 ADRD beneficiaries showed average age of 83 (+/−7), female (67.7%) and white (87.4%). Medicare reimbursements per person increased by 58% from the PRE ($47,912) to PERM period ($75,654). Age, ethnicity, gender (male), and comorbidities were significantly related to total reimbursements in each phase. Conclusions: Applying a taxonomy of NH phases, Medicare expenditures per person year are higher among patients in their terminal phase and higher still with comorbidities.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, nursing homes, Medicare expenditures, cognitive and functional decline

Introduction

In the United States, Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders (ADRD) affects approximately 5.4 million Americans or 1 in 8 persons aged 65 and older. 1 This prevalence estimate is based on linear extrapolation from published prevalence estimates for 2010 and 2020. 2 Among the oldest old, those aged 85+, 43% have ADRD. 1 Since ADRD prevalence rises with age and women live longer than men, it is not surprising that 65% of ADRD patients older than 65 years are women. 1 While most people in the United States with ADRD are Caucasian, a higher age-specific incidence of ADRD has been seen in African American and Hispanic persons. 1 There is evidence that health conditions, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and other conditions which are more prevalent among minorities, may account for this disparity. 3 –14

Due to the projected increase in the number of people older than 65 years in the United States, the number of new cases of ADRD is projected to double 15 by 2050. Given the increasing longevity of the aged, the number of Americans expected to live into their 80s and 90s will double, eventually comprising nearly 20% of the total population. 16 As the size of the aged population grows, so, too, will the numbers of people with ADRD; by 2050, the number of people aged 65 years and older with ADRD will triple, from 5.2 million to between 11 and 16 million. 2

The health care cost implications of ADRD are staggering. Aggregate payments for health care, long-term care, and hospice care for ADRD in 2011 were estimated to be $183 billion. 1 Medicare currently pays 51% of these costs, having paid $93 billion in 2011. 1 For all Medicare beneficiaries 65+ with ADRD, it has been estimated on the basis of the 2004 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, that in 2010 dollars, Medicare paid $19 304 per person, nearly 3 times the $6720 per person payment for similarly aged beneficiaries without AD. 1

Based on Medicare claims data from 2006, if one were to compute “the Alzheimer premium,” or the differential between total payments for selected medical conditions and those associated with the presence of ADRD, in 2010, diabetes would cost $8967, or 59% more due to the presence of ADRD; for coronary heart disease, the differential would be a 41% premium of $7173 and cancer would be linked to a 38% differential 1 of $6046. This ADRD differential is likely due to both a greater rate of hospitalization and longer hospital stays among patients with ADRD. 1

A recent review of the literature on methods of estimating the costs of ADRD in the United States notes that the economic burden of ADRD is distributed across many different population segments and providers within the medical care system. The authors note that much of the research to date has been limited because it has not summarized costs by category of expenditure, nor by where in the disease progression process patients were when consuming different types of services. 17

The purpose of our study is to empirically describe the costs to Medicare of ADRD and to characterize how these change over the course of patients’ disease progression, based upon a population of Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older identified as having an ADRD diagnosis and who were admitted to a nursing home (NH) between 1999 and 2007.

Methods

The data for this study rely upon nationwide data sets, including the Minimum Data Set (MDS), the Medicare enrollment file, and Medicare claims (hospital, skilled nursing facility [SNF], outpatient, home health and hospice claims), for the year 1999 to 2007. The MDS is an NH assessment tool for all residents served in Medicare-/Medicaid-certified nursing facilities. The assessments are completed upon admission to an NH and at least quarterly thereafter. The MDS contains detailed information about residents’ health conditions, including their functional status and comorbidities. The MDS is considered to have adequate reliability and construct as well as predictive validity. 18,19 The Medicare enrollment file includes Medicare beneficiaries’ unique identifier (eg, Medicare Health Insurance Claim number) and demographic characteristics (eg, date of birth, gender, race, and date of death) and their Medicare enrollment information (eg, whether they are enrolled in managed care plan). Medicare claims contain information about services rendered by inpatient and outpatient providers by type (eg, hospitals or SNFs), dates of service (ie, admission and discharge date), up to 10 diagnosis codes, procedure codes, and Medicare reimbursements paid to the provider.

Based on the MDS and Medicare claims file, a sequential, temporal history for each Medicare beneficiary was constructed, which allowed Medicare beneficiaries’ location of care to be tracked over time. 20 Therefore, we were able to identify first hospitalizations, first NH admissions, and where in time or sequence each individual’s health care utilization expenditures occurred.

Study patients had to be Medicare eligible, at least 65 years of age, and meet the ADRD claims based operational definition. Patients enrolled in Medicare Managed Care at any time during the observation period were excluded because Medicare Advantage plans do not submit claims data; including them would substantially underestimate Medicare reimbursements. Study patients had at least 1 inpatient hospital claim with a diagnosis of ADRD (International Classification of Diseases [ICD] codes for Alzheimer’s disease: 331.0; dementia similar to Alzheimer’s disease: 290.1x; 294.1x; 331.1x; 331.82; other dementia: 290.0; 290.2x; 290.3; 290.4; 290.8; 290.9; 291.2; 292.82; 294.8; 331.7; 331.9) or had 2 Medicare claims or MDS records with 1 of these ADRD diagnoses.

The inception cohort began in 1999, but we continued to accrue patients who met eligibility requirements through 2006, meaning not all study patients were observed from diagnosis to death. Since the date of Medicare claim defined ADRD diagnosis could have occurred long before patients ever entered an NH or well after they became permanent NH residents, we defined 3 mutually exclusive time periods per patient and summarized their Medicare reimbursed health care utilization and expenditures within each period. This categorization did not necessarily correspond to any disease severity or progression system, rather it was predicated entirely on when patients meeting our criteria for an ADRD diagnosis had entered a nursing facility temporarily or permanently.

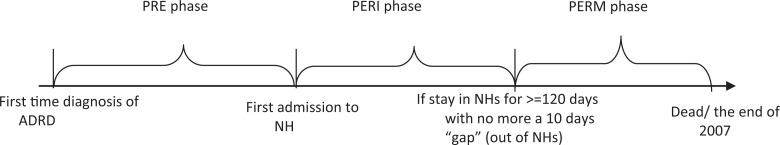

As shown in Figure 1, PRE–long-term care (PRE) phase was defined as the time between the first diagnosis of ADRD and the patient’s first admission to an NH. PERI–long-term care (PERI) referred to the time between the first NH admission and when the patient becomes a permanent NH resident. Permanent (PERM) phase was the time patients experience after having a stay in an NH of at least 120 continuous days, with no more than 10 days out of the NH during that period. Not all study patients experienced all 3 periods.

Figure 1.

The definition of 3 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders (ADRD) health care utilization phases.

For each phase (PRE, PERI, and PERM), by patient we counted the number of days in the phase, the number of service events of each type (eg, hospital admissions and days in hospital), and the accumulated Medicare reimbursements for each type of service. All Medicare expenditures within phase for all study participants who had any time in that phase were summarized. We also calculated expenditures per day in each phase to indicate the “intensity” of service consumption, reflecting both the amount and type of services consumed (ie, more expensive hospital days vs less expensive home health care services used) and the amount of time in the phase. Patients with very long phases where they did not use many Medicare services would have lower expenditures per day than those with short periods who used services on most days.

The MDS-based Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale was used to examine the change in functional status after an individual entered the PERM phase. The ADL scale includes 7 items: dressing, personal hygiene, toilet use, locomotion, unit transfer, bed mobility, and eating. Each item is scored from 0 (independent) to 4 (totally dependent). The total ADL score is the sum of all items and ranges from 0 to 28, with 0 indicating total independence and 28 indicating total dependence. 21 Cognitive performance was measured using the Cognitive Performance scale (CPS), which is composed of memory and decision-making items constructed on a scale of 0 (independent) to 6 (vegetative). 22

We calculated the proportion of patients experiencing a significant functional decline during the PERM period, as defined by having more than a 4-point change in the 28-point ADL scale. Prior research showed that ADL scores on the MDS fluctuated over time in between quarterly assessments, but that patients experiencing a decline of 4 points were much less likely to revert to their prior ADL score. 23 Therefore, we used a 4-point decline “cutoff” to indicate permanent decline in physical function. On the other hand, cognitive function decline was as defined by 1 point or greater change in the 7-point CPS scale since each category represents a clinical state rather than a mere summary score. 22 We also examined the number of days from the beginning of PERM phase to time of physical or cognitive functional decline.

After constructing cost and utilization variables per phase, a set of generalized linear models were used to examine the relationship between individuals’ demographic characteristics and their comorbidities and Medicare expenditures. A modified Park test and Box-Cox test were used to confirm the distribution function (γ distribution) and the link function (log link function), respectively.

Results

Of the 23 328 052 people in the Medicare Database for 1999 to 2007, the number of people included in the final sample was 3 681 702. Excluded were 18 242 396 non-ADRD cases, 584 674 cases with only 1 non-inpatient ADRD diagnosis, 404 640 persons below the age of 65 or who were enrolled in managed care at some point after receiving the ADRD diagnosis, and 29 955 records with irregularities concerning the date of death.

As can be seen in Table 1, the average person in the sample was a white female aged 82 to 85, with at least 1 comorbid condition. The proportion of patients with cancer is between 8% and 13% across the different cohorts. The proportion of patients with a cardiovascular comorbidity varied substantially by cohort. Variation in comorbidities by cohort is observed despite the fact that the proportion of patients dying before the end of observational period (December 31, 2007) is comparable across the PERI and PERM only cohorts at 78%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Cohort

| All participants | Those who have only PERI phase | Those who have only PERM phase | Those who have PRE and PERI phases | Those who only have PRE and PERM phases | Those who have PERI and PERM phases | Those who have all 3 phases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of observations a | 3 681 702 | 200 241 (5.44%) | 344 048 (9.34%) | 1 612 595(43.80%) | 1 150 549 (31.25%) | 36 975 (1.00%) | 337 294 (9.16%) |

| Age, years b | 83.30 (7.29) | 84.56 (7.51) | 84.29 (7.59) | 83.34 (7.17) | 83.19 (7.32) | 82.36 (7.33) | 81.78 (6.99) |

| Male | 32.29% | 34.90% | 24.16% | 37.66% | 27.47% | 29.78% | 30.08% |

| White | 87.37% | 88.50% | 87.91% | 87.97% | 86.37% | 85.67% | 86.86% |

| Black | 9.82% | 8.28% | 8.90% | 9.31% | 10.88% | 10.51% | 10.46% |

| Cancer | 11.34% | 9.36% | 8.08% | 12.85% | 10.11% | 11.51% | 12.78% |

| Congestive heart failure | 43.83% | 33.30% | 36.88% | 44.54% | 43.93% | 50.00% | 52.75% |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 33.62% | 23.11% | 25.27% | 34.57% | 33.72% | 38.22% | 43.06% |

| Diabetes | 31.30% | 24.40% | 30.07% | 29.58% | 32.99% | 38.45% | 38.37% |

| Parkinson | 10.91% | 6.79% | 10.15% | 10.18% | 11.59% | 12.99% | 15.04% |

| Stroke | 28.89% | 19.62% | 26.17% | 27.13% | 30.61% | 35.05% | 38.93% |

| Part B eligibility | 99.23% | 99.20% | 99.72% | 99.14% | 99.24% | 99.35% | 99.17% |

| Died by December 31, 2007, % | 75.07% | 78.42% | 77.74% | 76.45% | 73.66% | 71.29% | 68.99% |

| % Censored (by December 31, 2007) | 24.93% | 21.58% | 22.26% | 23.55% | 26.34% | 28.71% | 31.01% |

| Days to death by December31, 2007 b | 674 (649) | 187 (353) | 809 (604) | 452 (565) | 897 (632) | 1005 (622) | 1170 (652) |

| Days to censoring (by December31, 2007) b | 1176 (847) | 569 (659) | 1140 (831) | 986 (805) | 1346 (827) | 1358 (784) | 1629 (794) |

Abbreviations: PRE, pre-long-term care phase; PERI, peri-long-term care phase; PERM, permanent long-term care phase.

aThe numbers in parentheses indicate percentage of the total individuals.

bThe numbers indicate the mean (standard deviations).

Table 2 presents data by phase, combining the experiences of all patients who had a PRE, PERI, or PERM phase, regardless of which combination of other phases they experienced. Thus, these Medicare reimbursed utilization rates reflect the average experience of all patients with ADRD during a particular phase. By definition, during the PRE phase, no SNF services were received, while hospital use was virtually universal. Only 60% of patients were hospitalized during the PERI or PERM phases. A little more than one quarter of patients with ADRD have an emergency room (ER) visit during the PRE phase, but this more than doubles during the PERM phase when the vast majority of patients reside in an NH the entire period.

Table 2.

Proportion of Individuals With Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders That Incur Any Medicare Reimbursements, by Type of Medicare Services (1999-2007)

| PRE phase | PERI phase | PERM phase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of observations | 2 374 542 | 2 137 754 | 1 868 866 |

| Any skilled nursing facility reimbursement | n/a | 82.45% | 69.44% |

| Any inpatient reimbursement | 95.31% | 62.80% | 64.16% |

| Any Home Health Agency reimbursement | 24.32% | 29.87% | 2.40% |

| Any hospice reimbursement | 1.74% | 21.67% | 25.84% |

| Any emergency room reimbursement | 27.02% | 38.83% | 53.42% |

Abbreviations: PRE, pre-long-term care phase; PERI, peri-long-term care phase; PERM, permanent long-term care phase.

aThese 3 categories are not mutually exclusive—for example, an individual may have both PRE and PERI periods. Thus, these 3 groups will not add up to the total number of eligible individuals.

Table 3 presents the average Medicare reimbursements per patient with ADRD, by type of service, during each phase. Each Medicare claim was classified by whether it was an “ADRD-related expenditure” based upon the presence of at least 1 ADRD diagnosis on that particular claim. Comparing total Medicare expenditures for a service with the size of the ADRD-related expenditures provides some indication of the consistency with which providers were identifying ADRD as a major, or underlying, factor in patients’ treatment. Medicare beneficiaries with ADRD in the PRE phase, on average, have a higher proportion (65%) of their total Medicare expenditures as dementia-related Medicare reimbursements compared with patients in the PERI (35%) and PERM (41%) phases. A similar pattern is observed for hospitalizations; ADRD-related Medicare reimbursements for hospitalizations are highest in the PRE phase, averaging $29 743 per person, compared with $15 353 per person in PERI and $18 349 in PERM.

Table 3.

Average Medicare Reimbursement Per Person With Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, by Type of Services, During Each Phase a

| PRE phase | PERI phase | PERM phase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of observations | 2 374 542 | 2 137 754 | 1 868 866 |

| Total days in the period | 260 (446) | 360 (505) | 829 (633) |

| Medicare reimbursements in the period ($) | 47 912 (68407) | 67 625 (113079) | 75 654 (118491) |

| ADRD-related Medicare reimbursements in the period ($) | 31 284 (36543) | 23 648 (42898) | 30 791 (49016) |

| Total reimbursements per day in the period ($) | 1745 (2163) | 480 (787) | 128 (197) |

| Total reimbursements (ADRD related) per day in the period ($) | 1630 (2154) | 179 (400) | 51 (87) |

| Medicare reimbursements for hospitalizations in the period ($) | 42341 (60168) | 41 635 (92730) | 40 120 (93935) |

| ADRD-related Medicare reimbursements for hospitalizations in the period ($) | 29 743 (35766) | 15 353 (36697) | 18 349 (40792) |

| Medicare reimbursements for SNF in the period ($) | 0 | 15 431 (19166) | 19 318 (25035) |

| ADRD-related Medicare reimbursements for SNF in the period ($) | 0 | 5922 (11818) | 7499 (15122) |

| Medicare reimbursements for ER in the period | 1195 (4188) | 1864 (5392) | 2307 (5155) |

| ADRD-related Medicare reimbursements for emergency room in the period | 404 (1855) | 531 (2247) | 860 (2682) |

| Medicare reimbursements for outpatient visit in the period | 2522 (17330) | 4334 (26760) | 9074 (33941) |

| ADRD-related Medicare reimbursements for outpatient visit in the period | 345 (2257) | 393 (2337) | 1641 (4616) |

| Medicare reimbursements for home health in the period | 1513 (8458) | 2318 (9204) | 174 (2713) |

| ADRD-related Medicare reimbursements for home health in the period | 628 (4615) | 647 (4257) | 54 (1366) |

| Medicare reimbursements for hospice in the period | 341 (4225) | 2042 (9603) | 4661 (16487) |

| ADRD-related Medicare reimbursements for hospice in the period | 164 (2907) | 803 (6310) | 2389 (12225) |

Abbreviations: ADRD, Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders; SNF, skilled nursing facility; ER, emergency room; PRE indicates pre–long-term care phase; PERI, peri–long-term care phase; PERM, permanent long-term care phase.

aThe numbers indicate mean (standard deviation). These 3 categories are not mutually exclusive—for example, an individual may have both PRE and PERI periods. Thus, these 3 groups will not add up to the total number of eligible individuals.

Inpatient care accounts for a larger proportion of Medicare reimbursement for patients in the PRE period (88%) compared with the PERI (62%) and PERM (53%) periods. Medicare spends an average of $15 431 per person on SNF services in the PERI cohort and $19 318 per person in the PERM group. For those in the PERI period, SNF expenditures accounted for 23% of all Medicare reimbursements; for those in the PERM group, SNF services accounted for 26%. Since the Medicare SNF benefit is generally not intended for long-term care in NHs, the relatively high rate of SNF use during the PERM phase is associated with SNF use after hospitalizations during the PERM phase.

Medicare spending for emergency department, outpatient visits, and hospice care were all higher in the PERM phase than in the earlier phases. It should be noted that the high level of outpatient expenditures during the PERM phase are very different from Part B physician service costs which are not included in these calculations. Such outpatient expenditures are not included in the daily SNF reimbursement rates during periods when the patient was receiving the SNF benefit.

As expected, home health expenditures were highest in the PERI phase and lowest in the PERM phase. Medicare reimbursements for hospice services were highest during the PERM period, suggesting that most were patients receiving the hospice benefit while residents of an NH. Since about one half of all Medicare expenditures for hospice are attributable to patients with ADRD, it is likely that the other half of patients had comorbid diagnoses that were recorded as the reason for the terminal prognosis.

Multivariate analyses of total Medicare reimbursements were conducted separately by phase for those Medicare beneficiaries who were initially diagnosed in 1999, 2000, and 2001, allowing enough time to observe most patients’ total time in each phase. The results are presented in Table 4. The independent variables entered into the regression models were demographic characteristics and comorbidities identified in the Medicare claims. Consistent with prior research, blacks have higher reimbursements than whites in all 3 phases. Age, although statistically significant due to the large sample size, has a very weak effect on reimbursements, regardless of phase. The presence of a comorbidity, particularly congestive heart failure (CHF) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, is associated with substantially higher reimbursements across all 3 ADRD phases. The results across all years are similar, suggesting that these trends are stable.

Table 4.

Regression Analyses—Total Medicare Reimbursements Per Phase a

| PRE phase | PERI phase | PERM phase | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort start year | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 |

| No. of observations | 419 763 | 319 839 | 293 728 | 245 260 | 219 061 | 221 565 | 293 106 | 234 130 | 216 726 |

| Age | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 |

| Black | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.45 |

| Other race | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.30 |

| Female | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Cancer | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.18 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.42 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.39 |

| Diabetes | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.27 |

| Parkinson | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.17 |

| Stroke | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.24 |

Abbreviations: PRE, pre–long-term care phase; PERI, peri–long term care phase; PERM, permanent long term care phase.

aThe numbers in the cell are unstandardized β coefficient (on their original scales). All the coefficients are statistically significant at P < .01. The models also take account of state effects.

The rate of physical and cognitive functional decline was examined for those in the PERM period. Table 5 presents the frequency distribution of ADL and CPS scores for those in the PERM group at the time that they entered that phase. Since the MDS assessments are done at least quarterly, these baseline data reflect the MDS assessment closest to the point when patients with ADRD met the criteria for entering the PERM phase. Over 30% of patients were severely compromised in their ADL status around the time that they met the criteria for entering the PERM phase with ADL scale scores of 21 or higher, indicating being bed-bound and or unable to eat independently. Similarly, some 20% of patients with ADRD were severely cognitively impaired (CPS 5 or 6) at the time that they entered the PERM phase, a score that is comparable to a Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) score of <10. While about 20% of patients with ADRD still were reasonably independent in their late loss ADLs at the outset of the PERM phase, the preponderance of patients was substantially or extremely impaired.

Table 5.

Distribution of Functional Status at the Beginning of PERM Phase (Among Those Who Enter PERM phase) a

| Activities of Daily Living (ADL) score at the time of entering PERM Phase | Frequency | Percentage | Cognitive Performance Scale(CPS) at the time of entering PERM phase | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-4 | 203,403 | 11.06 | 0 | 96,363 | 5.24 |

| 5-8 | 183,396 | 9.97 | 1 | 136,194 | 7.41 |

| 9-12 | 240,357 | 13.06 | 2 | 286,117 | 15.56 |

| 13-16 | 279,140 | 15.18 | 3 | 755,249 | 41.07 |

| 17-20 | 364,847 | 19.83 | 4 | 201,941 | 10.98 |

| 21-24 | 272,780 | 14.83 | 5 | 204,575 | 11.12 |

| 25-28 | 295,887 | 16.09 | 6 | 158,491 | 8.62 |

Abbreviation: PERM, permanent long-term care phase.

a The sum of each of the two Frequency columns will not match due to missing observations in the ADL or CPS assessments.

Table 6 presents the results of analyses of the probability that patients with ADRD who entered the PERM phase either died or declined at least 4 points in the late loss ADL scale or experienced a 1 point decline on the CPS score. Also included in the table is the mean and standard deviation for the number of days patients spent in the PERM phase prior to dying or declining by the specified number of points on each scale. Some 18% of patients with ADRD died prior to declining 4 points on the ADL scale and 27% died prior to declining 1 point on the CPS. Over two thirds of patients (68.8%) declined in ADL before dying and 58% declined on CPS prior to dying. On average, it required about 1 year for patients with ADRD to decline that much, but there is a high degree of heterogeneity. Cross-referencing Tables 5 and 6, it is likely that those patients with the most impaired physical and cognitive functioning were most likely to have declined quickly or to have died without declining.

Table 6.

Distribution of Changes in Functional Status Among Those who Enter PERM Phase †

| Activities of Daily Living (ADL) decline a | Frequency | Percentage | Days to decline/death b | Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) decline c | Frequency | Percentage | Days to decline/death b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least 4 points of decline | 749,776 | 68.80 | 348 (385) | At least 1 point of decline | 694,298 | 58.36 | 356 (396) |

| No decline (still alive before the end of observational period, which is December31, 2007) | 141,549 | 12.99 | - | No decline (still alive before the end of observational period, which is December31, 2007) | 174,058 | 14.63 | - |

| No decline, died | 198,461 | 18.21 | 501 (409) | No decline, died | 321,379 | 27.01 | 532 (430) |

Abbreviation: PERM, permanent long-term care phase.

aAmong those whose baseline ADL is <22.

bThe numbers indicate mean (standard deviation).

cAmong those whose baseline CPS is <5.

†The population is restricted to those who have non-missing ADL and CPS assessments, and those who only stayed in one NH.

Discussion

Estimates of the cost of ADRD to Medicare depend upon assumptions about average survival postdiagnosis and how ADRD-specific expenses are identified. We identified Medicare expenditures over the duration of beneficiaries’ ADRD health care utilization experience using a claims-based definition of the disease using real Medicare claims and following patients in a large cohort that eventually used NH services between 1999 and 2007 for a short or a long stay. By dividing Medicare expenditures into 3 distinct phases of health care utilization, we were able to estimate expenditures in terms of periods following diagnosis and entering an NH, separating costs incurred before and after patients became permanent NH residents. Each of these phases is characterized by different patterns of health care utilization with 95% of patients using inpatient hospital care in the PRE period and 65% using hospital care after NH admission. Overall, Medicare expenditures are highest ($75 654 in 2007 dollars) after patients became permanent NH residents, largely because the average time in this period was well over 2 years. The relatively high proportion of permanent NH residents hospitalized (64.1%) and who use emergency departments (53.4%) clearly contributes to the high expenditures during this period. These high-average Medicare expenditures were observed in spite of the fact that over a third of beneficiaries entering the permanent NH placement phase were already severely restricted in late loss activities of daily living and a fifth were severely cognitively impaired.

In earlier studies of ADRD health care costs, 24 –42 the assessment of ADRD severity usually was based on a clinical assessment, such as including the MMSE or other tests as well as behavioral problems, dependence, and functional status. Most research has shown that as disease severity increases, direct health care costs also increase. However, in light of the substantial heterogeneity of most such studies in terms of the mix of patients, the types of costs included, and the analyses undertaken, it is difficult to compare them and to decide which estimate should be used as inputs into economic simulation models. By relying upon actual Medicare claims, revealing the variation in costs across patients even after dividing costs into periods postdiagnosis, our direct care cost estimates, though limited to Medicare, may be useful for future cost of illness studies. 17

Our use of a claims-based definition of ADRD results in a population that is more heterogeneous than those based upon clinical definitions found in some Alzheimer’s Disease registries. 43 Nonetheless, the average age at diagnosis and the proportion of women included is within the bounds of other studies based upon a clinical diagnosis. The proportion of patients with selected comorbidities varies substantially by cohort, possibly related to how long between diagnosis and death, with those observed through all 3 phases having the longest duration (almost 1200 days) and those observed only around the time of their short stay NH entry having the shortest duration (under 200 days). Perhaps these patients are more likely to acquire these diagnoses because of their more frequent use of health care system. 44 It may be the case that more comorbidities decrease the chance that ADRD will be noted as a diagnosis on a health utilization claim. Our data are consistent with this interpretation since only 40% of Medicare expenditures during the PERM phase have an ADRD-associated claim (when ADRD should be obvious), whereas this is true in 65% of expenditures during the PRE phase. If this is true, future research may have to reconsider how to consider the direct ADDR-related costs of medical care.

The construction and use of an ADRD patient taxonomy defined largely by the pattern of initial, intermittent, and permanent NH admissions made it possible to analyze the substantial variability in health care utilization and Medicare expenditures that these patients incur over the course of their illness. While this categorization scheme differs from the biological, clinical, functional, and behaviorally determined disease stages used in much of the existing literature, 24 –42 the use of the PRE, PERI, and PERM approach makes it possible to classify patients’ medical care use experiences during these episodes. This partitioning of patients’ ADRD career into phases partially overcomes the problem that some patients are diagnosed late, entering NH around the time of diagnosis (possibly through manifestation of previously unrecognized symptoms), while others are diagnosed relatively early in the disease process, either during a hospitalization for an unrelated reason or as a function of extensive diagnostic testing. This methodological approach makes it possible to deal with the issue of variation in survival time following the date of a diagnosis of ADRD appearing in a Medicare claim.

It is difficult to compare our estimates of Medicare Part A expenditures with those reported in other studies, even those using claims-based case definitions of ADRD. Many studies look at annual prevalence estimates for all Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with ADRD, thereby combining patients at very different stages of the disease. Comparisons are also complicated by differences in the years covered by a study, due to both inflation and the increased intensity of diagnostic testing and treatments for patients as well as differences in how ADRD is defined, both of which affect not only prevalence but also per capita costs. 45

The estimates presented here, particularly if they are refined in future studies to include even earlier physician diagnoses present on their billing data, could produce much more accurate estimates of the lifetime cost of ADRD since they would make it possible to estimate the cost impact of earlier diagnosis or changes in treatment practices. The establishment of nationally reliable estimates related to the characteristics of ADRD for these patients is challenging since individuals are brought to providers’ attention at various stages of disease. Some persons with early- and mid-stage ADRD are cared for at home, while others are admitted to nursing homes much earlier in the ADRD progression. Both conditions at diagnosis and survival time will affect both the amount and the intensity of health care utilization.

As ADRD is identified earlier due to diagnostic advances, greater awareness, and an interest in earlier treatment, estimates of the underlying costs, both public and private, will also rise. By dividing costs into phases, it is possible to explore the implications of changes in the composition of the population, the composition of the costs, and the duration of the phase. For example, if the proportion of ADRD cases identified several years before a first hospitalization or postacute care episode increases, the average duration and cost of the PRE period will increase. On one hand, this might translate into longer survival or shorter periods in the high-cost “terminal” period or it might have no effect on the duration of the terminal period, yielding a net increase in costs. Given the rapid changes in diagnostic practices and treatments, it would be very important to establish a data-based mechanism to track the implications of these changes.

As noted, a relatively large proportion of patients with ADRD are physically and cognitively impaired around the time they become permanently institutionalized, suggesting that between a third and a half of all patients with ADRD who eventually become NH residents do so with a fairly advanced or late stage of disease. In this population of permanent NH residents, over 25% used the Medicare hospice benefit, a finding that is consistent with recent studies of hospice in nursing homes. 46 The relatively high inpatient hospital and emergency department costs incurred by ADRD as patients while permanent NH residents is consistent with recent research revealing that a pattern of aggressive care for terminal, late-stage patients with ADRD occurs when these patients are hospitalized. 47 It would be important to understand whether it is the same or different patients who are consuming both acute care and palliative care services sequentially while still in the NH setting. At present, the evidence suggests that hospitalization of these patients varies geographically and that some hospitals are far more likely to institute aggressive procedures than others even though there is no evidence that these improve survival or quality of life. 48

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

It is important to note that this study of Medicare claims includes only individuals who eventually experienced an NH admission, meaning our estimates of SNF and NH use may be high. With a complete longitudinal Medicare claims file covering many years, it would be possible to use the same taxonomy in an additive manner to generate cost estimates for the whole population of patients with ADRD, including those who never enter a nursing home. Including Medicare claims for physician visits, where an increasingly high percentage of patients are initially diagnosed, would likely increase the estimates of the average disease duration as well as add to the cost estimates. Now that Part D (Medicare prescription drug coverage) is available on a virtually universal basis, future studies of Medicare costs of ADRD should also include this important component of treatment costs. We are confident that our methodology, applied to a more complete data set, would support meaningful and useful cost projections.

Similar to all studies based on insurance claims data, this study is also subject to the vagaries of ICD coding. There is no way to ascertain the accuracy of ADRD diagnoses and it is well established that claims-based diagnoses underestimate the prevalence of ADRD relative to either patient surveys or clinical reviews of medical records. As noted, our total cost estimates are conservative in that we did not include physician services, pharmacy costs, or any costs borne by Medicaid or out-of-pocket and indirect costs of unpaid caregivers. Including these costs would swamp the figures presented here.

In summary, this study adds to the growing literature on the costs of Alzheimer’s disease by characterizing the enormous heterogeneity of costs, even though we only focused on direct Medicare Part A expenditures. Since patients with ADRD increasingly constitute the bulk of the long-stay NH population served in the United States, it is important to understand the nature of the services they use and the patterns of expenditures both before and after they reach the nursing home. For unless there is a dramatic medical breakthrough that reduces the incidence of ADRD or there are policies developed to modify the intensity of treatments provided, Medicare will be spending an increasing share of its rapidly diminishing dollars on patients who will be moving in and out of the long-term care system.

Footnotes

Dr. Mucha is an employee of Pfizer, Inc. At the time of this research, Dr. Treglia was an employee of Pfizer, Inc. There are no other potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

This research was partially funded by a contract from Pfizer, Inc.

References

- 1. Alzheimers Association. 2011 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures 2011. http://www.alz.org/downloads/Facts_Figures_2011.pdf. Accessed on March 6, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the US population prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(8):1119–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Akomolafe A, Beiser A, Meigs JB, et al. Diabetes mellitus and risk of developing Alzheimer disease: results from the Framingham study. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(11):1551–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arvanitakis Z, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Diabetes mellitus and risk of Alzheimer disease and decline in cognitive function. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(5):661–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Biessels GJ, Staekenborg S, Brunner E, Brayne C, Scheltens P. Risk of dementia in diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(1):64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brayne C, Gao L, Matthews F. Challenges in the epidemiological investigation of the relationships between physical activity, obesity, diabetes, dementia and depression. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(suppl 1):6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Craft S, Watson GS. Insulin and neurodegenerative disease: shared and specific mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(3):169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ott A, Stolk RP, van Harskamp F, Pols HA, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia: the Rotterdam study. Neurology. 1999;53(9):1937–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pasquier F, Boulogne A, Leys D, Fontaine P. Diabetes mellitus and dementia. Diabetes Metab. 2006;32(5 pt 1):403–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sato T, Shimogaito N, Wu X, Kikuchi S, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M. Toxic advanced glycation end products (TAGE) theory in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2006;21(3):197–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schnaider Beeri M, Goldbourt U, Silverman JM, et al. Diabetes mellitus in midlife and the risk of dementia three decades later. Neurology. 2004;63(10):1902–1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiiki T, Ohtsuki S, Kurihara A, Naganuma H, et al. Brain insulin impairs amyloid-beta(1-40) clearance from the brain. J Neurosci. 2004;24(43):9632–9637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Watson GS, Craft S. The role of insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease: implications for treatment. CNS Drugs. 2003;17(1):27–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Whitmer RA. Type 2 diabetes and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2007;7(5):373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hebert LE, Beckett LA, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Annual incidence of Alzheimer disease in the United States projected to the years 2000 through 2050. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15(4):169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and the Merck Company Foundation. The State of Aging and Health in America, 2007. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mauskopf J, Mucha L. A review of the methods used to estimate the cost of Alzheimer's disease in the United States. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2011;26(4):298–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mor V, Intrator O, Unruh MA, Cai S. Temporal and geographic variation in the validity and internal consistency of the nursing home resident assessment minimum data set 2.0. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mor V, Angelelli J, Jones R, Roy J, Moore T, Morris J. I. Inter-rater reliability of nursing home quality indicators in the U.S. BMC Health Serv Res. 2003;3(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Intrator O, Hiris J, Berg K, Miller SC, Mor V. The residential history file: studying nursing home residents' long-term care histories(*). Health Serv Res. 2011;46(1 pt 1):120–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA. Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(11):M546–M553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49(4):M174–M182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mor V, Gruneir A, Feng Z, Grabowski DC, Intrator O, Zinn J. The effect of state policies on nursing home resident outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Albert SM, Sano M, Bell K, Merchant C, Small S, Stern Y. Hourly care received by people with Alzheimer's disease: results from an urban, community survey. Gerontologist. 1998;38(6):704–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ernst RL, Hay JW, Fenn C, Tinklenberg J, Yesavage JA. Cognitive function and the costs of Alzheimer disease. An exploratory study. Arch Neurol. 1997;54(6):687–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fillenbaum G, Heyman A, Peterson BL, Pieper CF, Weiman AL, et al. Use and cost of hospitalization of patients with AD by stage and living arrangement: CERAD XXI. Neurology. 2001;56(2):201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fillenbaum G, Heyman A, Peterson BL, Pieper CF, Weiman AL. Use and cost of outpatient visits of AD patients: CERAD XXII. Neurology. 2001;56(12):1706–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harrow BS, Mahoney DF, Mendelsohn AB, et al. Variation in cost of informal caregiving and formal-service use for people with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2004;19(5):299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leon J, Cheng CK, Neumann PJ. Alzheimer's disease care: costs and potential savings. Health Aff (Millwood). 1998;17(6):206–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leon J, Neumann PJ. The cost of Alzheimer's disease in managed care: a cross-sectional study. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5(7):867–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marin D, Amaya K, Casciano R, et al. Impact of rivastigmine on costs and on time spent in caregiving for families of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2003;15(4):385–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Max W, Webber P, Fox P. Alzheimer's disease. The unpaid burden of caring. J Aging Health. 1995;7(2):179–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Murman DL, Chen Q, Powell MC, Kuo SB, Bradley CJ, Colenda CC. The incremental direct costs associated with behavioral symptoms in AD. Neurology. 2002;59(11):1721–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rice DP, Fox PJ, Max W, et al. The economic burden of Alzheimer's disease care. Health Aff (Millwood). 1993;12(2):164–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Small GW, McDonnell DD, Brooks RL, Papadopoulos G. The impact of symptom severity on the cost of Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(2):321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhu CW, Leibman C, Townsend R, et al. Bridging from clinical endpoints to estimates of treatment value for external decision makers. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13(3):256–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhu CW, Scarmeas N, Torgan R, et al. Clinical characteristics and longitudinal changes of informal cost of Alzheimer's disease in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(10):1596–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhu CW, Scarmeas N, Torgan R, et al. Clinical features associated with costs in early AD: baseline data from the predictors study. Neurology. 2006;66(7):1021–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhu CW, Leibman C, McLaughlin T, et al. The effects of patient function and dependence on costs of care in Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(8):1497–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhu CW, Torgan R, Scarmeas N, et al. Home health and informal care utilization and costs over time in Alzheimer's disease. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2008;27(1):1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhu CW, Scarmeas N, Torgan R, et al. Longitudinal study of effects of patient characteristics on direct costs in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(6):998–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhu CW, Leibman C, McLaughlin T, et al. Patient dependence and longitudinal changes in costs of care in Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26(5):416–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jack CR, Jr., Albert MS, Knopman DS, et al. Introduction to the recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):257–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Song Y, Skinner J, Bynum J, Sutherland J, Wennberg JE, Fisher ES. Regional variations in diagnostic practices. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lin PJ, Kaufer DI, Maciejewski ML, Ganguly R, Paul JE, Biddle AK. An examination of Alzheimer's disease case definitions using medicare claims and survey data. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(4):334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Miller SC, Lima J, Gozalo PL, Mor V. The growth of hospice care in U.S. nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(8):1481–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, et al. End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):1212–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Gozalo PL, et al. Hospital characteristics associated with feeding tube placement in nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2010;303(6):544–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]