Abstract

To better understand responses in the large number of US-based patients included in a global trial of donepezil 23 mg/d versus 10 mg/d for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease (AD), post hoc exploratory analyses were performed to assess the efficacy and safety in US and non-US (rest of the world [RoW]) patient subgroups. In both subgroups, donepezil 23 mg/d was associated with significantly greater cognitive benefits than donepezil 10 mg/d. Significant global function benefits of donepezil 23 mg/d over 10 mg/d were also observed in the US subgroup only. Compared with RoW patients, US patients had relatively more severe AD, had been treated with donepezil 10 mg/d for longer periods prior to the start of the study, and a higher proportion took concomitant memantine. In both subgroups, donepezil had acceptable tolerability; overall incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events was higher in patients receiving donepezil 23 mg/d compared with donepezil 10 mg/d.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, donepezil, efficacy, tolerability, clinical trial, United States

Introduction

Donepezil, a piperidine-based, highly selective, reversible, noncompetitive inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase, has been shown to provide symptomatic benefits in patients at the mild, moderate, and severe stages of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). 1 –5 In July 2010, a high-dose formulation of donepezil (23 mg/d) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe AD. Approval of this new formulation was based on outcomes from a global 24-week, double-blind trial comparing donepezil 23 mg/d with donepezil 10 mg/d in more than 1400 patients with moderate-to-severe AD (baseline Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score of 0-20). 6 Patients were enrolled into this study at sites in numerous countries including Argentina, Australia, Austria, Chile, Croatia, Denmark, France, Germany, Hong Kong, India, Israel, Italy, Korea, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, and the US.

Results in the overall study population showed that the 23 mg/d dose provided statistically significant benefits over the 10 mg/d dose on the coprimary cognitive measure (Severe Impairment Battery [SIB]), but no statistically significant incremental benefit over that achieved with the 10 mg/d dose on the coprimary global function measure (Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Change-plus caregiver input [CIBIC-plus]). 6 As the US provided the largest proportion of participating sites (29%) and enrolled patients (32%), an efficacy subanalysis was performed in the US patient subgroup. This showed that donepezil 23 mg/d provided statistically significant benefits over 10 mg/d on both the cognitive and global function end points. 6,7

Since high-dose donepezil has been approved in the United States for about 2 years and based on a subanalysis of the performance of donepezil 23 mg/d in the US subgroup, it was thought that a more detailed evaluation of donepezil 23 mg/d in US patients would be highly relevant to US-based physicians treating advanced AD. Here, we report on further post hoc exploratory analyses of the efficacy and safety of donepezil 23 mg/d versus 10 mg/d in the US subgroup from this global trial. Moreover, as the US subgroup showed benefits on both primary end points, 6 we also describe outcomes with donepezil 23 mg/d and donepezil 10 mg/d among patients enrolled at sites outside of the US (rest of the world [RoW] subgroup) and analyze baseline characteristics in the 2 subgroups in an effort to evaluate if any may have influenced the observed outcomes. Another exploratory objective of the original study was to evaluate whether treatment response was related to the presence of the AD risk factor, apolipoprotein E4 (ApoE4), and it was, therefore, reported in this post hoc evaluation. Overall, these analyses are designed to provide an additional novel insight into the efficacy and safety outcomes with donepezil 23 mg/d across US-based and non-US-based subpopulations and will serve to provide physicians treating US patients with appropriate expectations of donepezil therapy.

Methods

Study Design

A detailed description of the original study design and methods is published elsewhere. 6 Briefly, this randomized, double-blind, multinational trial included patients with moderate-to-severe AD (MMSE 0-20) who had been receiving donepezil 10 mg/d for at least 3 months prior to screening. Patients were randomized, in a 2:1 ratio, to either increase their donepezil dose to 23 mg/d or to continue taking their current donepezil 10 mg/d dose for a period of 24 weeks. Patients receiving concomitant memantine therapy at doses of no more than 20 mg/d for at least 3 months prior to screening were eligible for enrollment, provided they maintained their current memantine dosage throughout the trial.

Instruments and Variables

Coprimary efficacy measures were the change from baseline to week 24 in SIB total score and the CIBIC-plus overall change score at week 24. Secondary efficacy measures were the change from baseline to week 24 in scores on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living-severe version (ADCS-ADL-sev) and the MMSE. Safety variables included the incidence, severity, and relationship to treatment of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), as well as the incidence and relationship to treatment of serious TEAEs; the change from baseline in laboratory parameters, vital signs, and body weight; and abnormal findings on 12-lead electrocardiographic recordings or physical and neurologic examinations.

Statistical Analysis

Post hoc, exploratory subgroup analyses were performed to assess the efficacy and safety of donepezil 23 mg/d and donepezil 10 mg/d in the US and RoW subgroups. The intent-to-treat (ITT) populations for each subgroup were used for statistical analysis of efficacy, with missing values imputed by the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method; observed case (OC) populations were also analyzed. Efficacy analysis was performed in the overall US and RoW subgroup populations, as well as in subsets of US and RoW patients with available baseline data for ApoE genetic status. Safety and tolerability were assessed in each subgroup safety population comprising those randomized patients who had received at least one dose of study medication and who had available data from at least 1 postbaseline safety assessment.

Statistical analysis of demographics and patient characteristics was performed to evaluate baseline differences between the US and RoW subgroups (overall safety populations). For comparison of continuous variables across the subgroups, a standard 2-sample t test was used; for comparison of categorical variables, a χ2 test was used. Baseline demographics and patient characteristics in the ApoE subsets of each subgroup were analyzed descriptively and no statistics are provided.

Changes from baseline to week 24 in SIB total scores among patients receiving donepezil 23 mg/d and 10 mg/d were analyzed for the US and RoW subgroups (overall populations and ApoE subsets) using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with terms for baseline score and treatment; similar models were used to evaluate score changes on the ADCS-ADL-sev and MMSE. For the SIB, ADCS-ADL-sev and MMSE end points, the least squares (LS) or adjusted means for each donepezil treatment arm were calculated, as were between-treatment differences (donepezil 23 mg/d vs 10 mg/d) in adjusted means, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and P values. The CIBIC-plus overall change scores for patients receiving donepezil 23 mg/d or 10 mg/d in the US and RoW subgroups (overall populations and ApoE subsets) were derived using a nonparametric ANCOVA method with an embedded Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel component, with adjustment for baseline severity (CIBIS-plus).

Results

Patient Characteristics

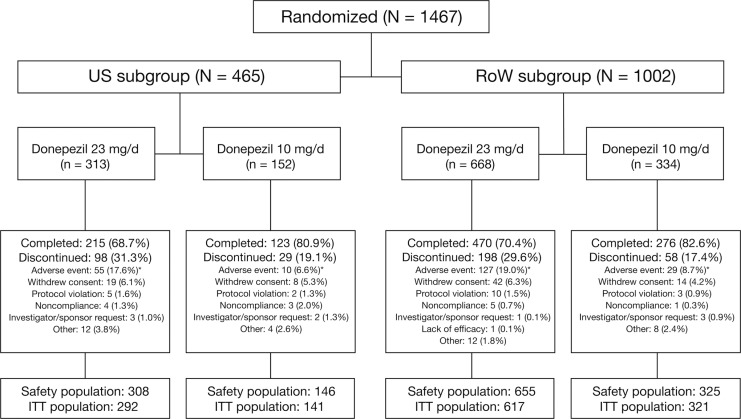

Of the 1467 patients randomized to treatment in the study, 465 (32%) were enrolled at sites within the United States (US subgroup) and 1002 (68%) were enrolled at sites outside the United States (RoW subgroup). In both subgroups, the percentage of patients who withdrew from the study was higher in the donepezil 23 mg/d treatment arm than in the donepezil 10 mg/d arm (Figure 1). Moreover, the percentage of patients who discontinued due to adverse events (AEs) was higher with donepezil 23 mg/d than with 10 mg/d. Discontinuation rates with donepezil 23 mg/d were comparable between US and RoW patients, as were discontinuation rates with 10 mg/d. Reasons for withdrawal in each treatment arm were generally similar (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition in the US and RoW subgroups. *Includes discontinuations due to serious adverse events. ITT indicates intent-to-treat; RoW, rest of the world.

Baseline demographics and treatment/disease characteristics for the US and RoW subgroups are shown in Table 1. Compared with patients in the RoW subgroup, patients in the US subgroup were older (mean age [±standard deviation, SD]: 74.7 [±8.6] years vs 73.5 [±8.5] years; P = .011), had a greater body mass index (BMI) (mean BMI [±SD]: 26.0 [±4.7] vs 24.8 [±4.1]; P < .001), and had been educated for a longer period of time (mean duration of education [±SD]: 13.2 [± 2.8] years vs 9.6 [±4.6] years; P < .001). Overall racial distribution differed between the US and RoW subgroups (P < .001); the majority of patients in both subgroups were white, although the proportion of white patients was higher in the US subgroup (87.4% vs 67.0%). Distribution of non-white populations was mainly among black (6.8%) and Hispanic (5.5%) in the US subgroup and among Asian/Pacific (25.2%) and Hispanic (6.9%) in the RoW subgroup. Overall distribution of residence status differed somewhat between the subgroups (P < .001), although nearly 90% of patients in both subgroups were living with their caregiver or with a relative/friend; fewer than 5% were living alone in either subgroup. Numerical differences between the US and RoW subgroups were seen only in the proportion of patients residing in assisted living facilities (6.6% vs 1.0%, respectively).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

| US subgroup |

RoW subgroup |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donepezil 23 mg/d | Donepezil 10 mg/d | Donepezil 23 mg/d | Donepezil 10 mg/d | |

| Safety population | 308 | 146 | 655 | 325 |

| Age, years a | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 74.5 (8.7) | 75.0 (8.2) | 73.5 (8.4) | 73.3 (8.7) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 114 (37.0) | 52 (35.6) | 242 (36.9) | 125 (38.5) |

| Female | 194 (63.0) | 94 (64.4) | 413 (63.1) | 200 (61.5) |

| BMI b | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 26.0 (4.7) | 25.9 (4.7) | 24.8 (4.2) | 24.6 (4.0) |

| Education, years b | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 13.3 (3.1) | 13.1 (2.4) | 9.5 (4.6) | 9.7 (4.7) |

| Race, n (%) c | ||||

| White | 268 (87.0) | 129 (88.4) | 440 (67.2) | 217 (66.8) |

| Black | 22 (7.1) | 9 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hispanic | 18 (5.8) | 7 (4.8) | 49 (7.5) | 19 (5.8) |

| Asian/Pacific | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 161 (24.6) | 86 (26.5) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.8) | 3 (0.9) |

| Residence status, n (%) c | ||||

| Lives with caregiver | 249 (80.8) | 107 (73.3) | 531 (81.1) | 258 (79.4) |

| Lives with relative/friend | 26 (8.4) | 12 (8.2) | 71 (10.8) | 33 (10.2) |

| Lives alone | 13 (4.2) | 8 (5.5) | 21 (3.2) | 22 (6.8) |

| Assisted living facility | 13 (4.2) | 17 (11.6) | 7 (1.1) | 3 (0.9) |

| Senior residence | 3 (1.0) | 2 (1.4) | 11 (1.7) | 3 (0.9) |

| Skilled nursing facility | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) |

| Intermediate nursing facility | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (1.1) | 4 (1.2) |

| Prior duration of 10 mg, weeks b | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 167.5 (120.7) | 166.7 (118.0) | 86.1 (90.9) | 76.0 (74.0) |

| Concomitant memantine at baseline, n (%) d | 231 (75.0) | 108 (74.0) | 121 (18.5) | 60 (18.5) |

| SIB | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 73.3 (20.1) | 76.1 (15.8) | 74.8 (16.2) | 75.1 (16.7) |

| MMSE b | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 12.2 (5.3) | 12.4 (4.9) | 13.6 (4.8) | 13.3 (4.6) |

| ADCS-ADL-sev | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 34.5 (11.1) | 35.0 (10.9) | 33.9 (10.9) e | 34.3 (11.4) |

| CIBIS-plus f | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.50 (0.89) | 4.48 (0.84) | 4.37 (0.83) | 4.35 (0.91) |

Abbreviations: ADCS-ADL-sev, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living-severe version; BMI, body mass index; CIBIS-plus, Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Severity-plus caregiver input; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; SIB, Severe Impairment Battery; RoW, rest of the world; SD, standard deviation.

a P < .05 for US subgroup (all patients) versus RoW subgroup (all patients); standard 2-sample t test.

b P < .001 for US subgroup (all patients) versus RoW subgroup (all patients); standard 2-sample t test.

c P < .001 for US subgroup (all patients) versus RoW subgroup (all patients); χ2 test.

d P < .001 for US subgroup (all patients) versus RoW subgroup (all patients); χ2 test.

e Based on 644 patients with available baseline ADCS-ADL-sev data.

f P < .01 for US subgroup (all patients) versus RoW subgroup (all patients); standard 2-sample t test.

The average length of time patients had been receiving donepezil 10 mg/d therapy prior to enrollment in the trial was nearly twice as long in the US subgroup than in the RoW subgroup (mean prior duration [±SD]: 167.2 [±119.7] weeks vs 83.0 [±85.7] weeks; P < .001). In addition, the proportion of patients taking concomitant memantine was more than 4 times higher in the US subgroup (74.7%) than in the RoW subgroup (18.5%; P < .001). In relation to disease characteristics, there were statistically significant differences in some baseline markers of disease severity, with patients in the US subgroup having a significantly lower (worse) baseline score than those in the RoW subgroup on the MMSE (mean [±SD]: 12.3 [±5.2] vs 13.5 [±4.7]; P < .001) and a significantly higher (worse) baseline score on the CIBIS-plus (mean [±SD]: 4.49 [±0.87] vs 4.36 [±0.85]; P = .007).

Efficacy

The US subgroup

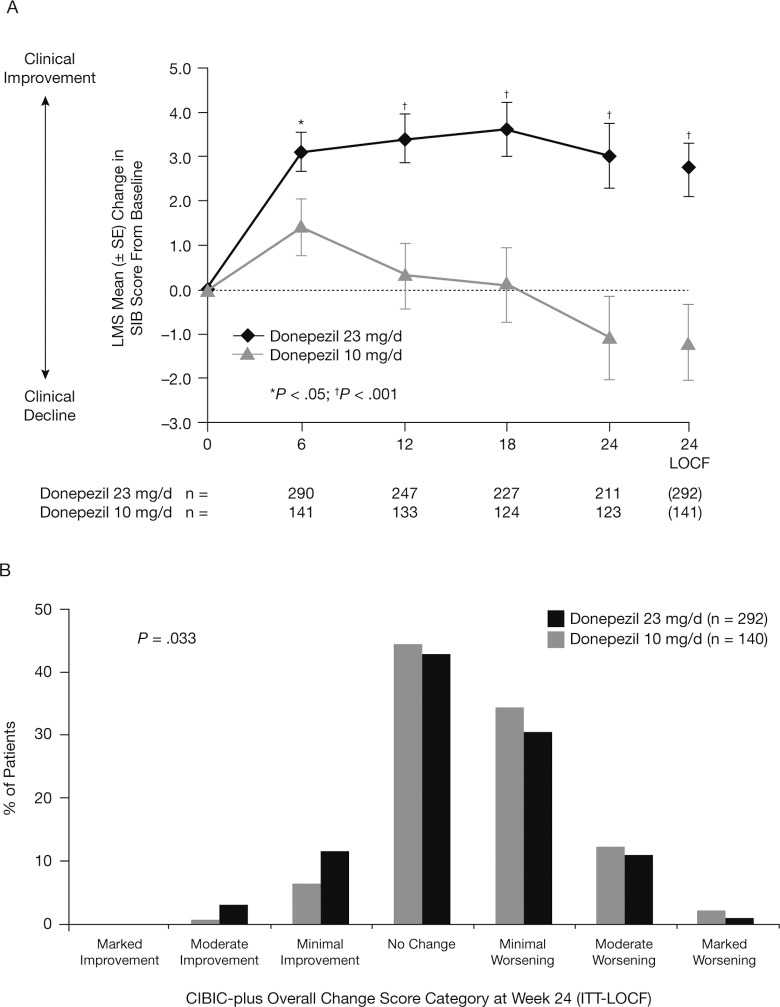

In the US subgroup, there was a statistically significant benefit that favored donepezil 23 mg/d over 10 mg/d on both coprimary end points (Figure 2 and Table 2). The LS mean treatment difference between the 2 donepezil doses at study end was 3.9 points (95% CI: 1.87-5.94; P < .001; ITT-LOCF analysis). The LS mean changes from baseline in SIB score were significantly greater with donepezil 23 mg/d than with donepezil 10 mg/d from week 6 onward (P < .05; OC analysis). Similarly, CIBIC-plus overall change scores at week 24 were significantly different in favor of donepezil 23 mg/d over 10 mg/d (P = .033; ITT-LOCF analysis). At study end, no statistically significant incremental benefits of donepezil 23 mg/d over 10 mg/d were observed on either the ADCS-ADL-sev or MMSE measures (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Treatment effects of donepezil 23 mg/d versus 10 mg/d in the US subgroup: (A) changes from baseline in SIB total score (OC and ITT-LOCF analysis); (B) frequency distribution of CIBIC-plus overall change scores at week 24 (ITT-LOCF). CIBIC-plus indicates Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Change-plus caregiver input; ITT-LOCF, intent-to-treat last observation carried forward; OC, observed cases; SIB, Severe Impairment Battery.

Table 2.

Summary of Efficacy Outcomes Following Treatment With Donepezil 23 mg/d and Donepezil 10 mg/d in the US Subgroup (ITT-LOCF)

| Parameter | Change from baseline to week 24 |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donepezil 23 mg/d | Donepezil 10 mg/d | ||

| SIB | |||

| n | 292 | 141 | |

| LS mean (SE) | +2.7 (0.59) | –1.2 (0.85) | <.001 |

| CIBIC-plus a | |||

| n | 292 | 140 | |

| Mean (SD) | 4.38 (0.97) | 4.57 (0.89) | .033 |

| ADCS-ADL-sev | |||

| n | 292 | 141 | |

| LS mean (SE) | –2.0 (0.37) | –2.6 (0.54) | .368 |

| MMSE | |||

| n | 292 | 141 | |

| LS mean (SE) | +0.5 (0.18) | –0.1 (0.26) | .092 |

Abbreviations: ADCS-ADL-sev, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living-severe version; CIBIC-plus, Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Change-plus caregiver input; LS, least squares; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; SIB, Severe Impairment Battery; SE, standard error; SD, standard deviation; ANCOVA, analysis of covariance.

a CIBIC-plus values are mean (SD) overall change scores at week 24 (determined using a nonparametric ANCOVA method with a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel component embedded, with adjustment for baseline CIBIS-plus [Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Severity-plus caregiver input]).

The RoW subgroup

In the RoW subgroup, a statistically significant treatment difference favoring donepezil 23 mg/d over 10 mg/d was seen on the SIB end point, but not the CIBIC-plus end point (Figure 3 and Table 3). The LS mean treatment difference between the 2 donepezil doses at study end was 1.4 points (95% CI: .09-2.67; P = .036; ITT-LOCF analysis). The LS mean changes from baseline in SIB score were significantly greater with donepezil 23 mg/d than with 10 mg/d at weeks 12 and 24 (P < .05; OC analysis), but not at week 18. The CIBIC-plus overall change scores at week 24 were not different (P = .768; ITT-LOCF). No statistically significant treatment differences were observed on the ADCS-ADL-sev or MMSE (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Treatment effects of donepezil 23 mg/d versus 10 mg/d in the RoW subgroup: (A) changes from baseline in SIB total score (OC and ITT-LOCF analysis); (B) frequency distribution of CIBIC-plus overall change scores at week 24 (ITT-LOCF). CIBIC-plus indicates Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Change-plus caregiver input; ITT-LOCF, intent-to-treat last observation carried forward; OC, observed cases; RoW, rest of the world; SIB, Severe Impairment Battery.

Table 3.

Summary of Efficacy Outcomes Following Treatment With Donepezil 23 mg/d and Donepezil 10 mg/d in the RoW Subgroup (ITT-LOCF)

| Parameter | Change from baseline to week 24 |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donepezil 23 mg/d | Donepezil 10 mg/d | ||

| SIB | |||

| n | 615 | 321 | |

| LS mean (SE) | +2.3 (0.61) | +1.0 (0.71) | .036 |

| CIBIC-plus a | |||

| n | 616 | 319 | |

| Mean (SD) | 4.16 (1.11) | 4.16 (1.12) | .768 |

| ADCS-ADL-sev | |||

| n | 616 | 320 | |

| LS mean (SE) | –1.3 (0.43) | –0.9 (0.50) | .467 |

| MMSE | |||

| n | 616 | 321 | |

| LS mean (SE) | +0.4 (0.19) | +0.3 (0.22) | .816 |

Abbreviations: ADCS-ADL-sev, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living-severe version; CIBIC-plus, Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Change-plus caregiver input; LS, least squares; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; SIB, Severe Impairment Battery; SE, standard error; SD, standard deviation; ANCOVA, analysis of covariance.

a The CIBIC-plus values are mean (SD) overall change scores at week 24 (determined using a nonparametric ANCOVA method with a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel component embedded, with adjustment for baseline CIBIS-plus [Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Severity-plus caregiver input]).

Safety

The US subgroup

Seventy-two percent of patients in the US subgroup experienced at least 1 TEAE (Table 4), with a higher overall incidence of TEAEs observed in patients receiving donepezil 23 mg/d than receiving donepezil 10 mg/d. The percentages of patients experiencing TEAEs that were considered mild or severe were similar with donepezil 23 mg/d (26.0% and 10.4%, respectively) and 10 mg/d (24.7% and 8.2%); however, a greater percentage of patients receiving donepezil 23 mg/d than receiving 10 mg/d experienced events considered as moderate in severity (39.9% vs 30.1%). Overall, most patients experienced TEAEs that were considered mild or moderate in severity. The most common TEAEs in the US subgroup were diarrhea, agitation, fall, nausea, and urinary tract infection (UTI; Table 4). Rates of nausea, UTI, vomiting, weight decreased, anorexia, fatigue, and urinary incontinence were at least twice as high among those receiving donepezil 23 mg/d as among those receiving donepezil 10 mg/d. Conversely, rates of hypertension, aphasia, and anxiety among patients receiving donepezil 23 mg/d were less than half the respective rates reported among those receiving 10 mg/d. The overall incidence of serious TEAEs was higher among US subgroup patients receiving donepezil 23 mg/d than among those receiving 10 mg/d (Table 4). Rates of individual serious TEAEs were low (<2.0%), with the most common being fall (1.8%). Three patients (0.6%) in the US subgroup died during the study or within 30 days of study discontinuation (2 receiving donepezil 23 mg/d and 1 receiving donepezil 10 mg/d); none of the deaths were considered possibly or probably related to donepezil treatment.

Table 4.

Summary of TEAEs and Serious TEAEs Among Patients Treated With Donepezil 23 mg/d or Donepezil 10 mg/d in the US Subgroup a

| Parameter, n (%) | Donepezil 23 mg/d (n = 308) | Donepezil 10 mg/d (n = 146) | All Patients (n = 454) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with ≥1 TEAE | 235 (76.3) | 92 (63.0) | 327 (72.0) |

| Diarrhea | 38 (12.3) | 14 (9.6) | 52 (11.5) |

| Agitation | 25 (8.1) | 10 (6.8) | 35 (7.7) |

| Fall | 25 (8.1) | 9 (6.2) | 34 (7.5) |

| Nausea | 29 (9.4) | 4 (2.7) | 33 (7.3) |

| Urinary tract infection | 25 (8.1) | 5 (3.4) | 30 (6.6) |

| Vomiting | 19 (6.2) | 2 (1.4) | 21 (4.6) |

| Weight decreased | 16 (5.2) | 3 (2.1) | 19 (4.2) |

| Fatigue | 14 (4.5) | 2 (1.4) | 16 (3.5) |

| Anorexia | 15 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (3.3) |

| Dizziness | 9 (2.9) | 6 (4.1) | 15 (3.3) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 8 (2.6) | 5 (3.4) | 13 (2.9) |

| Hypertension | 5 (1.6) | 7 (4.8) | 12 (2.6) |

| Urinary incontinence | 10 (3.2) | 1 (0.7) | 11 (2.4) |

| Aphasia | 4 (1.3) | 5 (3.4) | 9 (2.0) |

| Anxiety | 3 (1.0) | 6 (4.1) | 9 (2.0) |

| Patients with ≥1 serious TEAE | 39 (12.7) | 14 (9.6) | 53 (11.7) |

| Fall | 6 (1.9) | 2 (1.4) | 8 (1.8) |

| Dizziness | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.7) | 4 (0.9) |

| Pneumonia | 2 (0.6) | 2 (1.4) | 4 (0.9) |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.7) |

| Presyncope | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.7) |

| Syncope | 1 (0.3) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (0.7) |

Abbreviation: TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse events.

a Individual TEAEs reported in ≥3% of patients receiving either donepezil dose; individual serious TEAEs occurring in ≥0.5% of all patients.

The RoW subgroup

In total, 69.7% of patients in the RoW subgroup experienced at least 1 TEAE (Table 5); the overall incidence of TEAEs was higher with donepezil 23 mg/d than with donepezil 10 mg/d. Most patients experienced TEAEs that were considered mild or moderate in severity. The percentages of patients experiencing TEAEs considered mild or severe were similar with donepezil 23 mg/d (33.1% and 7.5%, respectively) and 10 mg/d (34.2% and 6.8%), but the percentage of patients experiencing events considered as moderate was greater with donepezil 23 mg/d than with 10 mg/d (31.9% vs 23.1%). The most common events in the RoW subgroup were nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, and anorexia. Rates of nausea, vomiting, and anorexia were at least twice as high among those receiving donepezil 23 mg/d as among those receiving donepezil 10 mg/d (Table 5). The overall incidence of serious TEAEs in the RoW subgroup was marginally higher among the patients receiving donepezil 10 mg/d than among those receiving 23 mg/d (Table 5), but the incidence of individual serious TEAEs was very low across all patients in the RoW subgroup (<1.0%). Ten patients (1.0%) in the RoW subgroup died during the study or within 30 days of study discontinuation (6 with donepezil 23 mg/d and 4 with donepezil 10 mg/d); no deaths were considered possibly or probably related to donepezil treatment.

Table 5.

Summary of TEAEs and Serious TEAEs Among Patients Treated With Donepezil 23 mg/d or Donepezil 10 mg/d in the RoW Subgroup a

| Parameter, n (%) | Donepezil 23 mg/d (n = 655) | Donepezil 10 mg/d (n = 325) | All patients (n = 980) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with ≥1 TEAE | 475 (72.5) | 208 (64.0) | 683 (69.7) |

| Nausea | 85 (13.0) | 12 (3.7) | 97 (9.9) |

| Vomiting | 70 (10.7) | 10 (3.1) | 80 (8.2) |

| Diarrhea | 42 (6.4) | 11 (3.4) | 53 (5.4) |

| Dizziness | 38 (5.8) | 10 (3.1) | 48 (4.9) |

| Anorexia | 36 (5.5) | 8 (2.5) | 44 (4.5) |

| Headache | 32 (4.9) | 11 (3.4) | 43 (4.4) |

| Weight decreased | 29 (4.4) | 9 (2.8) | 38 (3.9) |

| Insomnia | 27 (4.1) | 10 (3.1) | 37 (3.8) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 20 (3.1) | 11 (3.4) | 31 (3.2) |

| Urinary tract infection | 17 (2.6) | 14 (4.3) | 31 (3.2) |

| Aggression | 20 (3.1) | 10 (3.1) | 30 (3.1) |

| Patients with ≥ 1 serious TEAE | 41 (6.3) | 31 (9.5) | 72 (7.3) |

| Aggression | 1 (0.2) | 4 (1.2) | 5 (0.5) |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.6) | 5 (0.5) |

Abbreviation: TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse events.

a Individual TEAEs reported in ≥3% of patients receiving either donepezil dose; individual serious TEAEs occurring in ≥0.5% of all patients.

The ApoE Analysis

The ApoE genetic status was available at baseline for 810 patients in the safety population: 310 in the US subgroup and 500 in the RoW subgroup. Baseline characteristics for the subsets of US and RoW patients with ApoE data were generally similar to those for the overall US and RoW subgroup populations. There were no noteworthy differences between baseline characteristics in the subset of US patients with ApoE data when compared with the overall US subgroup. The subset of RoW patients with ApoE data contained a greater proportion of white patients versus the overall RoW subgroup (76.4% vs 67.0%) and a greater proportion taking concomitant memantine (18.5% vs 12.6%); when compared with the overall RoW subgroup, RoW patients with ApoE data also had marginally higher mean scores at baseline on the SIB (76.7 vs 74.9) and ADCS-ADL-sev (36.4 vs 34.0).

Distribution of ApoE status was significantly different between the US and RoW subgroups (P = .0345, χ2 test), with the US subgroup including a greater proportion of ApoE4 homozygotes versus the RoW subgroup (16.8% vs 10.6%), a similar proportion of ApoE4 heterozygotes (44.5% vs 46.0%, respectively) and a lower proportion of ApoE4 noncarriers (38.7% vs 43.4%, respectively). Evaluation of baseline demographics/characteristics for the ApoE4 homozygotes, ApoE4 heterozygotes, and ApoE4 noncarriers in the 2 subgroups revealed some noteworthy differences. In the US subgroup, the mean age of the ApoE4 homozygotes (72.0 years) was lower than both the ApoE4 heterozygotes and ApoE4 noncarriers (75.3 and 75.1 years); in addition, the proportion of ApoE4 homozygotes and ApoE4 heterozygotes taking concomitant memantine (80.8% and 79.0%) was higher versus the ApoE4 noncarriers (66.7%). In the RoW subgroup, the ApoE4 homozygotes differed from the ApoE4 heterozygotes and ApoE4 noncarriers in terms of the proportion of females (49.1% vs 63.0% and 68.2%), the proportion of Asian/Pacific patients (7.5% vs 17.4% and 22.6%) and the mean years of education (11.1 vs 9.9 and 9.3).

Efficacy and safety outcomes in the US and RoW subgroups were analyzed based on ApoE4 status (Table 6). In both subgroups, LS mean between-treatment differences in change in SIB score favored the donepezil 23 mg/d dose, regardless of ApoE4 status. Moreover, these between-treatment differences were much greater in ApoE4 homozygotes versus the ApoE4 heterozygotes and ApoE4 noncarriers (Table 6). Further analysis of the change in SIB score in the ApoE4 homozygotes identified a number of outliers. When data from these patients were removed from the analysis, LS mean between-treatment differences remained larger in ApoE4 homozygotes versus the ApoE4 heterozygotes and ApoE4 noncarriers for both the US subgroup (5.3 vs 1.6 and 1.7) and RoW subgroup (2.2 vs 1.6 and 1.8). For the coprimary CIBIC-plus end point and the secondary end points, there was no clear pattern of response in relation ApoE4 status (Table 6). The proportion of patients experiencing at least 1 TEAE was also not influenced by ApoE4 status (data not shown).

Table 6.

Effect of ApoE4 Status on Primary and Secondary Efficacy Outcomes Following Treatment With Donepezil 23 mg/d and Donepezil 10 mg/d in the US and RoW Subgroups (ITT-LOCF) a

| Parameter | US subgroup |

P Value b | RoW subgroup |

P Value b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change from baseline to week 24 |

LS mean difference (SE) | Change from baseline to week 24 |

LS mean difference (SE) | ||||||

| Donepezil 23 mg/d | Donepezil 10 mg/d | ||||||||

| Donepezil 23 mg/d | Donepezil 10 mg/d | ||||||||

| SIB | |||||||||

| Non-ApoE4 | |||||||||

| n | 81 | 32 | 136 | 72 | |||||

| LS mean (SE) | 3.0 (0.85) | 1.3 (1.36) | 1.7 (1.61) | .2928 | 2.9 (0.82) | 0.6 (1.12) | 2.3 (1.39) | .0999 | |

| Heterozygous ApoE4 | |||||||||

| n | 85 | 45 | 141 | 81 | |||||

| LS mean (SE) | 1.9 (0.99) | 0.3 (1.37) | 1.6 (1.70) | .3393 | 1.8 (0.78) | 0.5 (1.03) | 1.2 (1.30) | .3371 | |

| Homozygous ApoE4 | |||||||||

| n | 36 | 15 | 35 | 16 | |||||

| LS mean (SE) | 3.6 (2.24) | –9.4 (3.48) | 13.0 (4.14) | .0029 | 4.2 (1.62) | –1.4 (2.39) | 5.6 (2.89) | .0592 | |

| CIBIC-plus c | |||||||||

| Non-ApoE4 | |||||||||

| n | 80 | 32 | 136 | 72 | |||||

| LS mean (SE) | 4.3 (0.10) | 4.5 (0.16) | –0.3 (0.19) | .1869 | 4.2 (0.09) | 4.2 (0.13) | 0.0 (0.16) | .7558 | |

| Heterozygous ApoE4 | |||||||||

| n | 85 | 45 | 140 | 81 | |||||

| LS mean (SE) | 4.4 (0.09) | 4.6 (0.12) | –0.2 (0.15) | .1384 | 4.4 (0.08) | 4.5 (0.11) | –0.1 (0.14) | .7152 | |

| Homozygous ApoE4 | |||||||||

| n | 36 | 15 | 33 | 16 | |||||

| LS mean (SE) | 4.6 (0.16) | 4.5 (0.25) | 0.1 (0.30) | .7938 | 4.1 (0.22) | 4.6 (0.31) | –0.5 (0.38) | .2211 | |

| ADCS-ADL-sev | |||||||||

| Non-ApoE4 | |||||||||

| n | 81 | 32 | 136 | 72 | |||||

| LS mean (SE) | –1.3 (0.67) | –2.9 (1.07) | 1.6 (1.27) | .2158 | –0.6 (0.57) | –0.7 (0.78) | 0.1 (0.97) | .9313 | |

| Heterozygous ApoE4 | |||||||||

| n | 85 | 45 | 140 | 81 | |||||

| LS mean (SE) | –2.7 (0.70) | –1.7 (0.97) | –1.0 (1.20) | .4142 | –2.1 (0.63) | –2.1 (0.84) | 0.0 (1.05) | .9628 | |

| Homozygous ApoE4 | |||||||||

| n | 36 | 15 | 35 | 16 | |||||

| LS mean (SE) | –1.3 (1.04) | –4.0 (1.61) | 2.8 (1.92) | .1546 | –0.5 (1.33) | –2.3 (1.99) | 1.7 (2.42) | .4749 | |

| MMSE | |||||||||

| Non-ApoE4 | |||||||||

| n | 81 | 32 | 136 | 72 | |||||

| LS mean (SE) | 0.4 (0.32) | 0.6 (0.50) | –0.2 (0.60) | .6848 | 1.2 (0.27) | 0.9 (0.37) | 0.2 (0.46) | .6266 | |

| Heterozygous ApoE4 | |||||||||

| n | 85 | 45 | 141 | 81 | |||||

| LS mean (SE) | 0.4 (0.31) | –0.5 (0.43) | 0.9 (0.53) | .0844 | 0.7 (0.25) | 0.3 (0.33) | 0.4 (0.41) | .3276 | |

| Homozygous ApoE4 | |||||||||

| n | 36 | 15 | 35 | 16 | |||||

| LS mean (SE) | –0.2 (0.55) | –0.3 (0.86) | 0.1 (1.02) | .9267 | 1.4 (0.45) | 0.7 (0.67) | 0.7 (0.82) | .3855 | |

Abbreviations: ADCS-ADL-sev, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living-severe version; ApoE, apolipoprotein E; CIBIC-plus, Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Change-plus caregiver input; ITT-LOCF, intent-to-treat last observation carried forward; LS, least squares; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; RoW, rest of the world; SIB, Severe Impairment Battery; SE, standard error; SD, standard deviation; ANCOVA, analysis of covariance.

a Populations are based on a subset of patients with known ApoE status and available baseline and postbaseline data for the respective end points.

b P values derived using an ANCOVA method with terms for baseline score and treatment.

c The CIBIC-plus values are mean (SD) overall change scores at week 24 (determined using a nonparametric ANCOVA method with a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel component embedded, with adjustment for baseline CIBIS-plus [Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Severity-plus caregiver input]).

Discussion

High-dose donepezil was approved by the US FDA for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD on the basis of results from a large clinical trial including patients enrolled in more than 20 different countries. 6 Across this multinational patient population, donepezil 23 mg/d was shown to provide statistically significant incremental benefits over donepezil 10 mg/d on the cognitive end point (SIB), but not the global function end point (CIBIC-plus). Efficacy subanalyses in the US subgroup, representing almost a third of the total study population, demonstrated significant incremental benefits of donepezil 23 mg/d over 10 mg/d on both coprimary end points. 6,7 Based on these observations, additional post hoc exploratory analyses were conducted to fully evaluate the efficacy and safety of donepezil 23 mg/d versus 10 mg/d both in the US subgroup and in the subgroup of patients enrolled outside of the US, the RoW subgroup. Furthermore, despite ApoE data not being available for all patients, additional exploratory analyses were performed in these subgroups to evaluate whether treatment response was related to ApoE status.

In both the US and RoW subgroups, patients treated with donepezil 23 mg/d showed significant benefits in cognition, as measured by the SIB, compared with patients taking donepezil 10 mg/d. A statistically significant incremental benefit of high-dose (23 mg/d) over standard-dose donepezil (10 mg/d) was also observed on the global function end point (CIBIC-plus) in the US subgroup; no statistically significant difference was observed in the RoW subgroup or, as previously reported, the overall study population. 6 On the secondary efficacy measures (MMSE and ADCS-ADL-sev), treatment differences were not statistically significant in either subgroup, similar to outcomes observed in the overall study population. These results support previous evidence suggesting that the SIB may be a more sensitive instrument than the MMSE for detecting cognitive changes in moderate and severe AD populations. 8 Although the specific mechanism/mechanisms whereby the higher dose of donepezil provides incremental cognitive benefits on the SIB has not been fully elucidated, acetylcholinesterase continues to be present in the brain in advanced AD, providing a target substrate for selective inhibition. 9 Moreover, it has been shown that cholinergic deficits are most evident in more advanced AD, suggesting that greater inhibition of acetylcholinesterase, via higher dosing, may be required to achieve sufficient cholinergic stimulation in the advanced stages of the disease. 9

Analysis of baseline demographics and disease/treatment characteristics for the US and RoW subgroups showed that there were noteworthy differences in some baseline demographic characteristics, including age, race, BMI, education, and residence status. Some or all these baseline differences may have had some influence on the efficacy outcomes seen with donepezil 23 mg/d and 10 mg/d in the respective subgroups. For example, higher education levels have been associated with a faster rate of cognitive decline in patients with AD. 10,11 Thus, the higher level of education in the US subgroup may have contributed to the different pattern of SIB score change observed among patients who continued receiving their existing donepezil 10 mg/d dose in the 2 subgroups (Figures 2A and 3A). Since the pattern of SIB score change among patients who transitioned to donepezil 23 mg/d was similar between the US and RoW subgroups, we might speculate that the higher donepezil dose was able to attenuate the influence of education on cognitive decline.

The US and RoW subgroups also differed in terms of the severity of disease at baseline with the US subgroup showing worse mean scores on measures of cognition (MMSE) and global function (CIBIS-plus), indicating that patients in the US subgroup tended to have more severe AD. Moreover, a higher proportion of patients in the US subgroup (nearly 75%), compared with 18.5% in the RoW subgroup, were taking concomitant memantine, which may also indicate a more severe AD population since the coprescription of donepezil and memantine is a common practice in the United States for more patients with advanced AD. Memantine is more widely available in the US than the RoW, and this also may have influenced the respective usage of this medication in the 2 subgroups. The length of time that patients had been treated with donepezil prior to this study was considerably longer in the US subgroup (>3 years), suggesting these patients were further along in their disease course or that treatment was begun earlier in the disease than for patients in the RoW subgroup. The relative severity of AD in the 2 subgroups may also have influenced efficacy outcomes. In the original study publication, it was observed that between-treatment differences on the SIB end point were numerically larger in the cohort of patients with more advanced AD (MMSE 0-16) than in the overall study population. 6 Moreover, this more advanced cohort also appeared to benefit from donepezil 23 mg/d on the CIBIC-plus end point. The more advanced disease in the US subgroup versus the RoW subgroup might explain why the US subgroup also showed numerically larger between-treatment differences on the SIB end point and also appeared to benefit from donepezil 23 mg/d on the CIBIC-plus end point.

In addition to measurable characteristics of the enrolled patients, other factors may have influenced the relative efficacy and safety of donepezil 23 mg/d and 10 mg/d in the 2 subgroups. For example, economic, cultural, and language factors might have contributed to the baseline differences between the subgroups, as well as the observed efficacy and safety outcomes. In particular, the CIBIC-plus end point, which is based heavily upon the rater’s perception of improvement or decline, may have been influenced by these factors.

Exploratory analysis of a subset of patients with available data on ApoE4 status may provide additional information on characteristics influencing the observed treatment outcomes, in particular the SIB outcomes. Between-treatment differences in change in SIB score favoring high-dose donepezil were substantially larger among ApoE4 homozygotes than among ApoE4 heterozygotes and ApoE4 noncarriers, and remained larger even after removal of outlying data. However, no clear pattern of response in relation to ApoE4 status was observed for the CIBIC-plus, ADCS-ADL-sev, or MMSE end points. The ApoE4 genetic status has previously been associated with differential rates of cognitive decline among healthy elderly persons and patients with mild cognitive impairment. 12,13 Moreover, a previous study suggested that donepezil treatment was particularly effective in reducing the risk of progression from mild cognitive impairment to AD among patients with one or more ApoE4 allele. 14 The current results may, therefore, suggest that ApoE4 status also influences cognitive decline during the course of AD and that the higher donepezil dose may be somewhat more effective in reducing this influence in ApoE4 homozygotes. However, as the patients were not stratified by ApoE4 status in the current study, there were a number of differences between the homozygotes, heterozygotes, and noncarriers in terms of baseline characteristics (eg, age, gender, and education) and all or some of these differences may have influenced the observed outcomes. Therefore, it is difficult to interpret these results, and prospective studies in larger patient populations are required to further elucidate these preliminary findings.

In both subgroups (US and RoW), the overall incidence of TEAEs was higher in patients receiving donepezil 23 mg/d than receiving donepezil 10 mg/d, similar to what was observed in the full study population. 6 Most patients in both subgroups experienced TEAEs that were considered mild or moderate in severity. The TEAEs that tended to be more common with donepezil 23 mg/d than donepezil 10 mg/d were typically cholinergic in nature and included gastrointestinal events such as diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. A small proportion of patients across the 2 subgroups also experienced less typical cholinergic-related AEs, including insomnia, urinary incontinence, psychiatric events (eg, agitation and aggression), and cardiovascular events (eg, presyncope/syncope), all of which have been previously associated with donepezil therapy. 15 In both subgroups, the incidence of individual serious TEAEs was uniformly low (<2%). Overall, no new safety findings were observed in either subgroup, and the types of TEAEs and serious AEs observed were consistent with those reported in other studies of donepezil. 1,4,5,16,17

The safety profile for the donepezil 23 and 10 mg/d doses was relatively consistent across both subgroups. However, AEs and serious AEs associated with more advanced disease, such as falls and agitation, 18 were more commonly reported in the US subgroup patients, which may also support the assertion that patients in this subgroup had more advanced disease at baseline. Other differences in TEAE rates between the subgroups may also reflect differences in baseline disease/treatment characteristics. For example, the incidence of nausea and vomiting, which are considered centrally mediated cholinergic symptoms, was lower in the US subgroup, whereas the incidence of diarrhea, which is not considered to be centrally mediated, was higher in the US population. These differences could potentially be a reflection of the lower BMI of the RoW patients—lower weight has been associated with higher rates of cholinergic-related AEs 6 —and/or the higher proportion of US patients taking concomitant memantine—memantine has potential antiemetic properties due to putative antiserotonergic activity (5-HT3 antagonist). 19

The current findings must be interpreted with consideration of specific limitations. The described analyses were based on an initial efficacy subanalysis of the US population reported in the original study publication and were, therefore, post hoc and exploratory in nature. Furthermore, the study was relatively underpowered to detect statistical differences between donepezil 23 and 10 mg/d in either the US orRoW subgroups. In addition, the RoW patients receiving donepezil 10 mg/day had a better than anticipated SIB change trajectory during the study period. This may suggest that there are variations in treatment practices between the outpatient setting and the clinical trial setting, which might have minimized the between-treatment differences in the RoW subgroup. Finally, this global study was not designed to compare efficacy and safety among the studied subgroups; indeed, on the basis that the US subgroup represents a more homogenous population and the RoW subgroup, a more heterogeneous population, any comparisons and conclusions must be considered cautiously.

In conclusion, this analysis indicated that the cognitive benefits of donepezil 23 mg/d over donepezil 10 mg/d were apparent in both the US and RoW subgroups from this global clinical trial. In addition, the US subgroup also gained statistically significant benefit from donepezil 23 mg/d on the global function end point. This additional benefit in the US subgroup was likely attributable to a number of differences in demographic and disease/treatment-related characteristics, most notably the more severe baseline disease in the US subgroup. Donepezil 23 mg/d had an acceptable tolerability profile in both subgroups, with the most common TEAEs occurring at a higher incidence with 23 mg/d than 10 mg/d being typically cholinergic in nature. The findings of the current analyses, particularly the identification of various characteristic differences between the 2 subgroups, may allow physicians to make more informed decisions when selecting patients for prescription of high-dose donepezil.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Zane Bai of Eisai Inc. for additional post hoc analysis.

Footnotes

Data included in the article have been previously presented in poster format at the 63rd Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), April 9-16, 2011; Honolulu, Hawaii, USA and the NADONA 2011 National Conference, July 16-20, 2011; Kissimmee, Florida, USA.

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Stephen Salloway has received consultation fees from the Eisai Inc. Jacobo Mintzer has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. Jeffrey L. Cummings has provided consultation to Eisai Inc. David Geldmacher has received both research support related to the conduct of the reported study and consulting honoraria in relation to donepezil from Eisai Inc. Yijun Sun is a ex-employee of Eisai Inc. Jane Yardley is a current employee of Eisai Ltd. Joan Mackell is a current employee of Pfizer Inc and holds stock in Pfizer Inc.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: The described analyses derive from a phase 3 clinical study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00478205) is sponsored by Eisai Inc. Editorial support in the development of this manuscript was provided by Richard Daniel, PhD, of PAREXEL, and was funded by Eisai Inc. and Pfizer Inc. Jacobo Mintzer has received grant research support from Pfizer and Eisai, but not for the specific activities reported in this study.

References

- 1. Black SE, Doody R, Li H, et al. Donepezil preserves cognition and global function in patients with severe Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;69(5):459–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Feldman H, Gauthier S, Hecker J, Vellas B, Subbiah P, Whalen E. A 24-week, randomized, double-blind study of donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 2001;57(4):613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seltzer B, Zolnouni P, Nunez M, et al. Efficacy of donepezil in early-stage Alzheimer disease: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(12):1852–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Winblad B, Engedal K, Soininen H, et al. A 1-year, randomized, placebo-controlled study of donepezil in patients with mild to moderate AD. Neurology. 2001;57(3):489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Winblad B, Kilander L, Eriksson S, et al. Donepezil in patients with severe Alzheimer's disease: double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2006;367(9516):1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Farlow MR, Salloway S, Tariot PN, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of high-dose (23 mg/d) versus standard-dose (10 mg/d) donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease: a 24-week, randomized, double-blind study. Clin Ther. 2010;32(7):1234–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Summary Review for Aricept (donepezil hydrochloride extended release) 23 mg Sustained Release. 2012.

- 8. Schmitt FA, Cragar D, Ashford JW, et al. Measuring cognition in advanced Alzheimer's disease for clinical trials. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2002;(62):135–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sabbagh M, Cummings J. Progressive cholinergic decline in Alzheimer's disease: consideration for treatment with donepezil 23 mg in patients with moderate to severe symptomatology. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scarmeas N, Albert SM, Manly JJ, Stern Y. Education and rates of cognitive decline in incident Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(3):308–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stern Y, Albert S, Tang MX, Tsai WY. Rate of memory decline in AD is related to education and occupation: cognitive reserve? Neurology. 1999;53(9):1942–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Whitehair DC, Sherzai A, Emond J, et al. Influence of apolipoprotein E varepsilon4 on rates of cognitive and functional decline in mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(5):412–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caselli RJ, Reiman EM, Locke DE, et al. Cognitive domain decline in healthy apolipoprotein E epsilon4 homozygotes before the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(9):1306–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M, et al. Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(23):2379–2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Inglis F. The tolerability and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of dementia. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2002;(127):45–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rosenblatt A, Gao J, Mackell J, Richardson S. Efficacy and safety of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease in assisted living facilities. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(6):483–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Doody RS, Ferris S, Salloway S, et al. Safety and tolerability of donepezil in mild cognitive impairment: open-label extension study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(2):155–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Feldman HH, Woodward M. The staging and assessment of moderate to severe Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;65:S10–S17. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rammes G, Rupprecht R, Ferrari U, Zieglgansberger W, Parsons CG. The N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor channel blockers memantine, MRZ 2/579 and other amino-alkyl-cyclohexanes antagonise 5-HT(3) receptor currents in cultured HEK-293 and N1E-115 cell systems in a non-competitive manner. Neurosci Lett. 2001;306(1-2):81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]