Abstract

Reminder devices reportedly improve medication adherence in the elderly patients with mild dementia; however, the efficacy of such devices remains unexplored. Therefore, a 3-month before and after study with convenience sampling was conducted to determine the efficacy of a medication reminder device used by 18 participants (aged 81.2 ± 6.2 years) with Clinical Dementia Rating scores of 0.5 or 1. At the onset of device use, examiners visited the users’ homes to ensure that they and their caregivers understood how to use the device. Caregivers monitored its use during the first week. Values of the self-administration medication rate during 1 week for 13 (72.2%) users showed improvement at 3 months. This result revealed that reminder devices can improve medication adherence in the elderly patients with mild cognitive impairment. Further study is needed to assess the magnitude of this improvement and to enhance its support for users with mild cognitive impairment.

Keywords: medication adherence, dementia, reminder, memory aid, mild cognitive impairment

Introduction

The population of individuals with dementia will increase considerably in the next few decades. In 2009, Alzheimer’s Disease International estimated that 65.7 million people in the world will have dementia by 2030 and that this number will increase to 115.4 million by 2050. 1

Cognitive impairment is one of the risk factors for medication nonadherence in the elderly patients. 2 Even mild cognitive impairment often results in poor adherence. 3 –5 An appropriate strategy for improving adherence is required for successful disease management and reduction in health care costs. However, few studies have described about the strategies developed to enhance medication adherence in the elderly patients with cognitive impairment.

A medication reminder device is a tool that uses an alarm cue to prompt users to take medication. Some case studies have revealed that such devices may be effective in enhancing medication adherence in the elderly patients with mild dementia. 6 –8 However, the degree of efficacy of these devices and the appropriate support for this population in using such devices have not yet been determined. In addition, the security of medication management using these devices is a concern in this population. In this study, the efficacy of such devices in medication management for the elderly patients with mild cognitive impairment was investigated. Empirical evidence was collected to address this concern and provide recommendations for appropriate use of medication reminder devices in this population.

Methods

Participants

Families of the elderly patients and health care professionals familiar with our research were offered trial use of the medication reminder devices in return for participation. One of the examiners (an occupational therapist or rehabilitation engineer) conducted a preliminary interview by phone with either the family member or the health care professional referring the elderly participant. The examiners visited potential participants’ homes to confirm that they met the study criteria and to obtain informed consent.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: score of 0.5 or 1 on the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) 9 scale, aged ≥65 years, living at home, and history of missed medication doses, overdoses, or need for verbal reminders to take medication once or more during 1 week. Exclusion criteria were as follows: visual or hearing impairment, motor dysfunction, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia sufficient to interfere with the operation of the reminder device, no fixed dosing time or place, medication in a form other than tablets or capsules, and no caregivers to fill the device with tablets or capsules.

This study was conducted from September 2008 to December 2011. The experimental protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Research Institute of the National Rehabilitation Center for Persons with Disability and the Medical Ethics Committee of Shinshu University.

Intervention

The automatic pill dispenser (Pivotell Ltd, Walden, Essex, UK; Figure 1) was the medication reminder device used in this study. Its audible and visual stimuli remind users when to take their medication. When the alarm rings, the correct dose of medication is released into the lid opening. Users must then invert the device to obtain medication and stop the alarm.

Figure 1.

The automatic pill dispenser is 190 × 180 × 56 mm and 480 g (including batteries). Left: the device in closed position. Right: the device in open position to set the alarm and insert medication. The device can be locked using a key.

The examiners evaluated the following points in the participants before they used the device: users’ ability to discriminate the alarm sound, initiate a search for the device on the basis of the alarm cue, obtain medication, return the device to the correct position, and prepare a glass of water for taking medication. In case of participants not finding any difficulty with using the device, the device and its usage were customized. Customized conditions included medication loaded into the device, loading schedule, location in the home, time of the alarm, and other individual considerations. Brief instructions regarding the operation of the device were written for each user and attached to the device. The device was occasionally used for part of the medication regimen prescribed to each user. The examiners then trained the users and their caregivers to use the device. Evaluation, customization, and training were completed typically in 1 visit. An additional visit was made if necessary. The caregivers then monitored device use during the first week of its usage. They were asked to provide minimal assistance to users while using the devices, only when required.

The examiners supervised 2 follow-up procedures: 1 involved the above-mentioned caregivers’ monitoring and the other involved long-term monitoring to manage events causing changes in use during the follow-up period, such as altered prescriptions or changes in users’ daily lifestyle or state of health.

Assessment

Caregivers reported the results of monitoring during the first week to the examiners by phone.

Values of the self-administration medication rate (SAMR) prior to implementation of the device were compared with those measured at 1 and 3 months after onset of device use. The SAMR was defined as the ratio of the number of doses taken independently to the number of all prescribed doses during 1 week. Caregivers confirmed the number of doses taken independently by monitoring the unused medication and counting the number of times help was required to use the device. The benefits from using the device other than SAMR was examined through open questioning of users and their caregivers. If users stopped using the device within the 3-month duration of the study, they were asked to provide the reasons for cessation.

Results

The examiners visited the homes of 19 potential participants. One participant was excluded because of lack of an adequate caregiver to operate the device. Thus, in total, 18 participants (aged 81.2 ± 6.2 years; 15 females) participated in this study. Seventeen participants (94.4%) lived alone and 1 participant lived with an elderly spouse (Table 1). Alzheimer’s disease was the most common underlying cause of cognitive impairment (n = 11, 61.1%; Table 1). No formal diagnosis related to cognitive impairment had been made in 3 participants (Table 1). The CDR score of 10 participants (55.6%) was 0.5 and that of remaining participants was 1 (Table 1). The Mini-Mental State Examination scores of 13 participants (72.2%) ranged from 21 to 26 (mild cognitive impairment). 10 Scores for the remaining participants were >11 (moderate impairment; Table 1). 10 Caregivers for filling medication of 10 participants (55.6%) were their family members living separately (Table 1). At the beginning of the study period, the most widely administered regimen programmed into the device involved taking medication once each morning (n = 11, 61.1%; Table 1). Medications for the following ailments were administered using the device: hypertension, dementia, and gastrointestinal illnesses (Table 2). Seven people used the device for part of their prescribed medication regimen at the beginning of the study period (Table 1). For medications not administered using the device, some users received caregivers’ assistance but others received no assistance.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants

| Age, years | |

|---|---|

| Mean ± SD (range) | 81.2 ± 6.2 (70-93) |

| Sex | n (%) |

| Female | 15 (83.3) |

| Household | |

| Elderly alone | 17 (94.4) |

| Diagnosis of cause of cognitive impairment | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 11 (61.1) |

| Mixed dementia | 1 (5.5) |

| Vascular dementia | 3 (16.7) |

| None | 3 (16.7) |

| Clinical Dementia Rating | |

| 0.5 | 10 (55.6) |

| 1 | 8 (44.4) |

| Mini Mental State Examination | |

| 21-26 | 13 (72.2) |

| 14-21 | 5 (27.8) |

| The SAMR a prior to using the device | |

| 0% | 11 (64.1) |

| <80% | 4 (22.2) |

| >80% | 3 (16.7) |

| Caregiver for filling the medication | |

| Family members living separately | 10 (55.6) |

| Caregiver/visiting nurse | 8 (44.4) |

| Medication regimen administered by the device | |

| Each morning | 11 (61.2) |

| Each evening | 1 (5.5) |

| Each morning and evening | 2 (11.1) |

| Each morning, noon, and evening | 4 (22.2) |

| The device can be used for | |

| All medicines prescribed to the user | 11 (61.1) |

| A part of the medicines prescribed to the user | 7 (38.9) |

a The self-administration medication rate (SAMR): the ratio of the number of doses taken independently to the number of all prescribed doses during 1 week.

Table 2.

Types of Medications Administered Using the Device

| Types | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Hypotensive drugs | 11 (61.1) |

| Antidementia drugs | 10 (55.6) |

| Gastrointestinal drugs | 8 (44.4) |

| Drugs for heart failure | 4 (22.2) |

| Antithrombotic drugs | 4 (22.2) |

| Antipollakiuria drugs | 3 (16.7) |

| Vitamin preparation | 3 (16.7) |

| Hematopoietic drugs | 2 (11.1) |

| Others | 6 (33.3) a |

| Multiple answers |

a Includes 6 different types of medications.

Fifteen participants (83.3%) could use the device during the first examiners’ visit. One participant (5.6%) required additional visits before initiating the use of the device. The remaining 2 participants (11.1%) needed practice with their family members before initiating device use. Because most participants were initially unwilling to use the device, the examiners requested their cooperation in order to decrease family members’ anxiety about the medication and to allow us to examine the utility of the device.

Once and more during the first week, 15 caregivers (83.3%) reported that they helped the users to manipulate the device or find unused medication in the device after the scheduled dosing time. Among them, 5 (27.8%) reported these events on 2 or more consecutive occasions during this period.

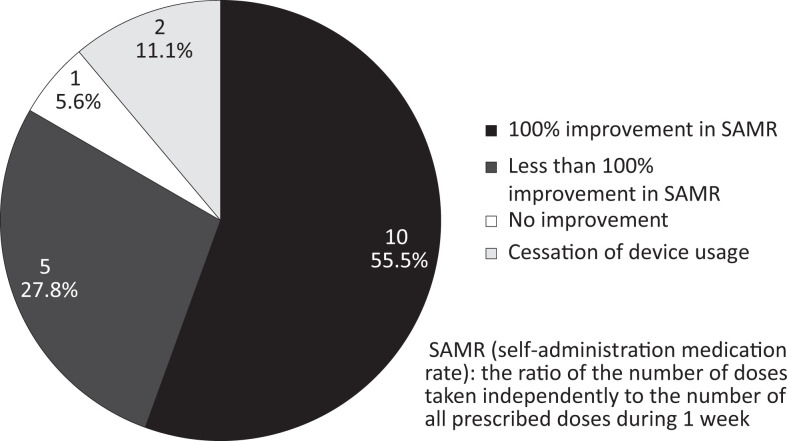

Changes in SAMR 1 month after onset of device use are shown in Figure 2. Ten users (55.5%) showed 100% improvement in SAMR values from before onset of use to 1 month after onset. The SAMR values for 5 users (27.8%) showed an improvement of <100% (28.6%, 57.1%, 78.6%, 85.7%, and 85.7%). No improvement was observed in the SAMR value for 1 user (5.6%). The remaining 2 users (11.1%) ceased to use the device within the first month.

Figure 2.

Changes in self-administration medication rate (SAMR) after 1 month.

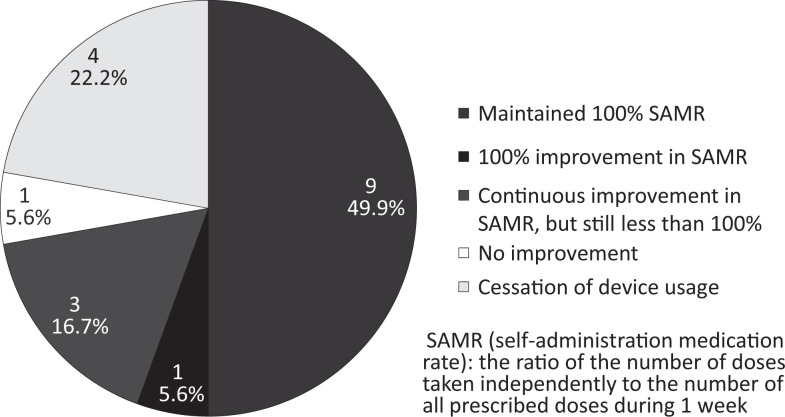

Changes in SAMR at 3 months are shown in Figure 3. Nine users (49.9%) maintained SAMR values of 100%, and 1 user (5.6%) showed 100% improvement in SAMR values. The SAMR values for 3 users (16.7%) showed continual improvement from the onset of use but were still <100%. These values were 14.3%, 64.3%, and 76.2%. No improvement was observed in the SAMR value for 1 user (5.6%).

Figure 3.

Changes in self-administration medication rate (SAMR) after 3 months.

Four users (22.2%) ceased to use the device during the 3 months of the study (at 10 days, 22 days, 2 months, and 2.5 months). Their respective reasons for cessation were as follows: embarrassment about the warning beep due to improper operation of the device, wrist fracture due to a fall, occasionally forgetting to take medication despite use of the device, and onset of low back pain necessitating changes in prescription. Only in the third case discontinuation was prompted by the caregiver.

Caregivers reported the following benefits from using the device: maintenance of normal blood pressure in users, reduction of caregivers’ burdens, and decreased care costs. Users reported gaining self-confidence because of improved SAMR and success at learning the skills necessary to use the device.

Discussion

According to previous reviews, 11,12 factors hindering good use of memory aids generally included old age and lack of experience using similar types of aids premorbidly. However, the results of this study suggested that people with these 2 conditions and CDR scores of 0.5 or 1 can become good users of medication reminder devices. This discrepancy might be due to the fact that the aid was externally programmed and prepared and therefore required minimal cognitive resources for utilization. In addition, professional support and monitoring by caregivers at the onset of use may also have contributed to the success of the elderly participants using the device in this study. In many cases, elderly people with mild cognitive impairment are unwilling to use new technology; they may also have difficulty with some types of learning. 13 –15

Caregiver’s help is a prerequisite for use of the medication reminder device examined in this study. Caregivers were required to fill the device with medication and monitor both its effect on the users and any events necessitating changes in its use, including cessation of use. Furthermore, this device simply prompts users to take medication at a fixed time and in a particular place. Therefore, its use is not applicable to some types of medication, such as medication taken only when necessary and medication with contraindicated conditions after administration. Thus, this device has only limited application for scheduled doses. Moreover, the device cannot be used under conditions included in the exclusion criteria of this study. From the standpoint of medication management for people with cognitive impairment, this device should be developed as a technical aid for use with caregivers’ help.

This study design has certain limitations. First, the outcome measure of the status of taking medication was estimated according to the amount of unused medication counted by the caregivers in this study. Assessment of outcome in this manner resulted in problems in some cases. For example, users forgot to take medication after extracting it from the device and subsequently the medication was lost. To prevent this problem, concurrent visual observation would be more effective in using the status of taking medication as an outcome measure. Second, no generalizations can be made on the basis of the high success rate with the reminder device because this result was obtained through convenience sampling of the participants. In this study, people who referred participants to the examiners either became caregivers or encouraged caregivers in the utilization of the device. Therefore, almost all caregivers were strongly supportive of the intervention in this study, which may have influenced the results positively. Third, because of the nonsystematic data collection methods used in this study, no generalizations can be made about the contribution of this device to good disease management, decreasing of care costs, reducing of family members’ burdens, and increasing users’ self-confidence. To expand on the findings of this study, future randomized, controlled trials must include these measures and refine the measurement of the status of taking medication. In addition, the contribution of this device to disease management in users, for example, blood pressure management in users taking hypotensive drugs, can be assessed in future studies. Questionnaires may also be administered to evaluate family members’ burden and users’ self-confidence.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the participants, caregivers, and occupational therapists for their willingness to take part in this study.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: Funded by Health Labour Sciences Research Grant (H22-Dementia- General-001).

References

- 1. Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2009. http://www.alz.co.uk/research/files/WorldAlzheimerReport.pdf. Accessed February 7, 2012.

- 2. Cooper C, Carpenter I, Katona C, et al. The AdHOC study of older adults’ adherence to medication in 11 countries. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(12):1067–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahn IS, Kim JH, Kim S, et al. Impairment of instrumental activities of daily living in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Psychiatry Invest. 2009;6(3):180–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Allaire JC, Gamaldo A, Ayotte BJ, Sims R, Whitfield K. Mild cognitive impairment and objective instrumental everyday functioning: the Everyday Cognitive Battery Memory Test. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(1):120–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hayes TL, Larimer N, Adami A, Kaye JA. Medication adherence in healthy elders: small cognitive changes make a big difference. J Aging Health. 2009;21(4):567–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gilliard J. Enabling technologies for people with dementia: Cross-National Analysis Report 2004. http://www.dementia-voice.org.uk/Projects/EnableFinalProject.pdf. Accessed February 7, 2012.

- 7. Buckwalter KC, Wakefield BJ, Hanna B, Lehmann J. New technology for medication adherence: electronically managed medication dispensing system. J Gerontol Nurs. 2004;30(7):5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sather BC, Forbes JJ, Starck DJ, Rovers JP. Effect of a personal automated dose-dispensing system on adherence: a case series. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2007;47(1):82–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tarawneh R, Snider BJ, Coats M, Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating. In: Abou-Saleh MT, et al. ed. Principles and Practice of Geriatric Psychiatry. 3rd ed. Chichester, UK: Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Folstein MF, Folstei SE, Fanjiang G. MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination. Clinical Guide. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Evans JJ, Wilson BA, Needham P, Brentnall S. Who makes good use of memory aids?: results of a survey of people with acquired brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003;9(6):925–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kapur N. Compensating for memory deficits with memory aids. In: Wilson BA, ed. Memory Rehabilitation. London, UK: Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hashimoto R, Meguro K, Yamaguchi S, et al. Executive dysfunction can explain word-list learning disability in very mild Alzheimer’s disease: the Tajiri Project. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58(1):54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kasai M, Meguro K, Hashimoto R, Ishizaki J, Yamadori A, Mori E. Non-verbal learning is impaired in very mild Alzheimer’s disease (CDR 0.5): normative data from the learning version of the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60(2):139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beversdorf DQ, Ferguson JLW, Hillier A, et al. Problem solving ability in patient with mild cognitive impairment. Cog Behav Neurol. 2007;20(1):44–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]