Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-transduced T cells (CAR-T) have been shown to improve outcomes in patients with CD19 and BCMA-positive lymphoproliferative disorders. The identification of viable targets for hematological malignancies other than B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) and multiple myeloma (MM) has, however, lagged behind.

CD30 has been validated as a target for classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) given the efficacy of brentuximab vedotin (BV), a CD30 monoclonal antibody (mAb) conjugated with monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE, an antimitotic agent) in multiple settings, including front-line, consolidation, and salvage (1–3). Although using a murine idiotype (HRS3) instead of the humanized BV idiotype (cAC10), a CD30-specific CAR was originally designed in Germany in the 1990s (4), and later adapted and optimized at Baylor College of Medicine (5). Human T cells transduced with this CAR (CD30.CAR-Ts) showed activity in xenograft models of HL. The preclinical activity seen in this and other subsequent studies utilizing anti-CD30 CARs laid the foundation for their evaluation in early-phase clinical trials.

CD30 is also expressed in a subset of T-cell lymphomas (TCL), and BV has shown good activity in these disorders, making CD30.CAR-Ts a promising potential therapy in this setting as well. Several early-phase studies of CD30.CAR-Ts have also allowed the enrollment of patients with CD30-positive TCLs. The restricted expression of CD30 in normal T cells limits the potential “on-target, off-tumor” effects of CD30.CAR-Ts, but also prevents their applicability to a wider variety of T-cell malignancies. Therefore, more universal T-cell markers, such as CD2, CD5 and CD7, are being pursued as potential targets.

Targeting a universal T-cell antigen with a T-cell derived product raises potential deleterious consequences, however. On one hand, since the target antigens are expressed on the CAR-T cells themselves, they may be susceptible to killing by neighboring CAR-Ts during their manufacture (and after infusion), a phenomenon called fratricide (6). On the other hand, because culture conditions favor the growth and transduction of T cells, circulating malignant cells may get transduced during the manufacturing process when using autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), providing a means of tumor escape. Finally, because native and malignant T cells share expression of the antigen being targeted, in vivo long-term persistence of CAR-Ts could lead to T-cell aplasia resulting in profound immunodeficiency (7). Consequently, to be successful, any treatment strategy will have to address these potential obstacles.

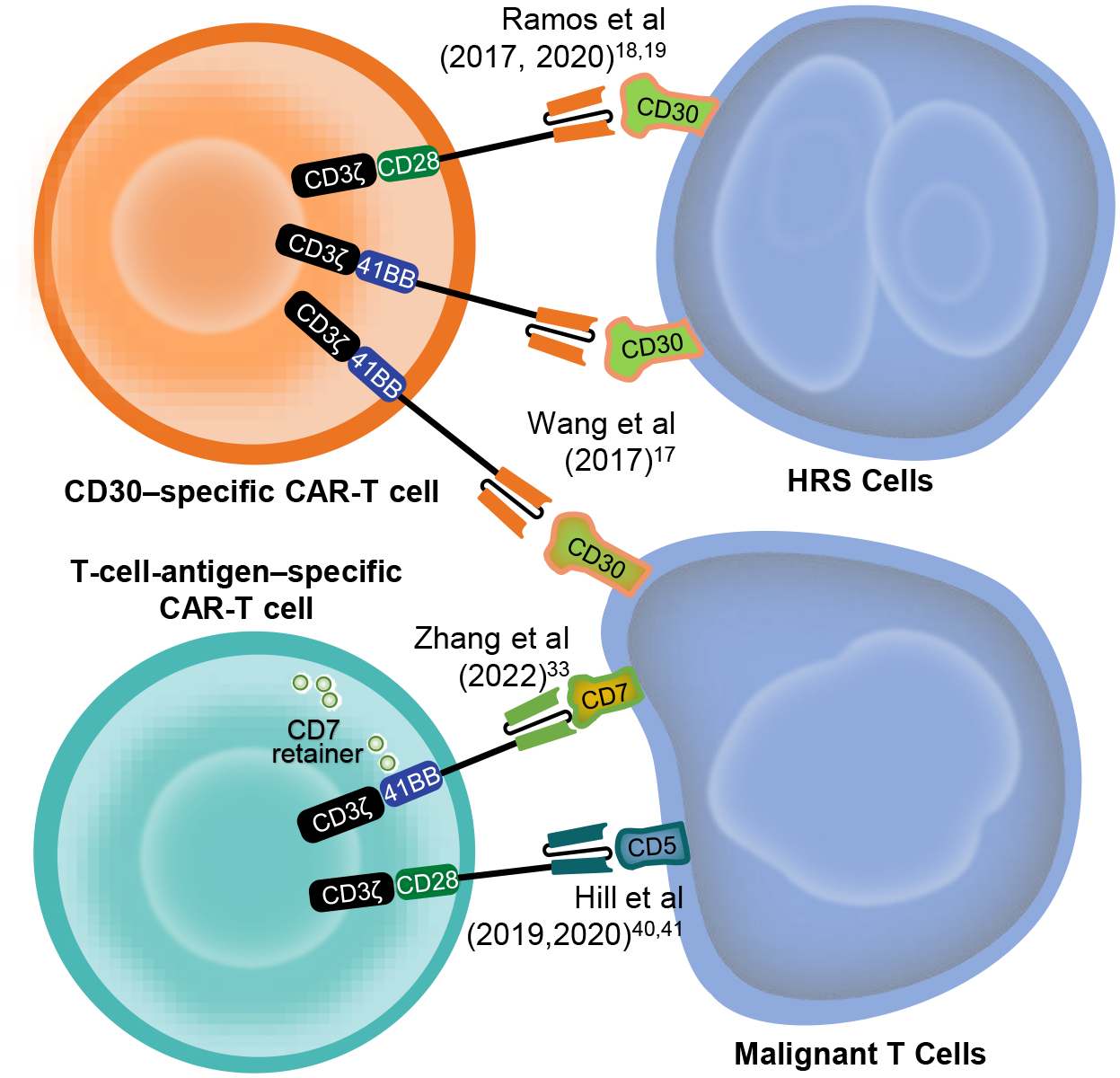

Herein, we review published data on clinical trials using CAR-T cells for HL and TCL. We will begin by summarizing the results of targeting CD30 via CAR-T cells in HL, and then address targeting CD30, CD5 and CD7 with CAR-Ts in TCL (see Figure 1). Current challenges and potential future directions will be discussed.

Figure 1:

A summary of the major CAR-T cell targets in Hodgkin and T-cell lymphomas. Adapted and modified with permission from: Leung WK, Ayanambakkam A, Heslop HE, Hill LC. Beyond CD19 CAR-T cells in lymphoma. Curr Opin Immunol. 2022 Feb; 74:46–52.

CAR-T cells in Hodgkin Lymphoma

Although the majority of HL patients are cured with first-line combination chemotherapy, 10–20% will have refractory or recurrent (r/r) disease (8), which has a poor prognosis. Treatment for r/r HL has included salvage chemotherapy or immunotherapy with possible consolidative autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT). Adoptive T-cell therapy has also been investigated to improve the outcomes of these patients (9). One of the earliest examples of adoptive T-cell therapy for HL was the use of EBV-specific T cells (EBVSTs), as a significant portion of HLs are associated with EBV infection and express EBV antigens. EBVSTs have shown activity in several EBV-related diseases, including post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) (9–11). However, this approach has several limitations, including the lack of universal EBV positivity in HL and the intrinsic immunosuppressive potential of HL, which may evade the antitumor activity of native EBVST (12). Whereas these approaches are still being studied and optimized, targeting CD30 via genetically modified T cells has generated considerable interest more recently.

CD30 expression and targeting in Hodgkin lymphoma

CD30 was identified more than four decades ago and is a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family that is expressed on various immune cells, including some granulocytes and activated B and T lymphocytes. Additionally, it is highly expressed by Hodgkin Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells (13). The high expression of CD30 in HL has implied a possible role in HL pathogenesis, but data are conflicting. While some studies have implicated CD30 in ligand-independent activation of the NFkB pathway, others have suggested that NFkB activation is unrelated to CD30 (14,15). Given the limited expression by other tissues and thus lower potential of “on-target, off-tumor” adverse events, multiple strategies have been developed to target CD30 in HL, including mAbs and antibody-drug conjugates (13). The success of BV encouraged targeting CD30 with CAR-Ts.

Earlier preclinical studies have demonstrated the ability of anti-CD30 CAR-T cells to lyse HL cell lines expressing CD30 (4,16). The efficacy of these first-generation CAR-Ts, lacking a costimulatory endodomain, was limited but supported the potential efficacy of a CD30-specific CAR. Additionally, those studies suggested that soluble CD30 (sCD30), which is often detected at higher levels in advanced HL patients, would not necessarily decrease the efficacy of CD30.CAR-Ts (4,5), fostering their further development.

CD30.CAR-T cells in relapsed/refractory HL

A few early-phase trials have investigated the antitumor activity and safety of CD30.CAR-Ts in r/r HL (see Table 1). The first published phase 1 trial reported results in 17 r/r HL patients (17). In this study, patients received autologous CAR-Ts transduced with a second-generation CD30-specific CAR (derived from the AJ878606.1 mAb) that included a 4–1BB costimulatory endodomain and was delivered by a lentiviral vector (CD30-BB.CAR-T). Patients received one or two infusions of CAR-Ts after varied lymphodepleting chemotherapy regimens. Two subsequently published studies also used autologous T cells transduced with a CD30-specific CAR, but which was derived from the HRS3 mAb, contained a CD28 costimulatory endodomain, and was delivered via a γ-retrovirus (CD30–28.CAR-T) (18,19). Ramos et al. reported the results of using CD30–28.CAR-T in seven r/r HL patients without using any lymphodepleting chemotherapy (18). Subsequently, the largest published study to date enrolled 42 r/r HL patients in two parallel trials at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) and University of North Carolina who received CD30–28.CAR-T preceded by lymphodepleting chemotherapy using fludarabine with cyclophosphamide or bendamustine, or only bendamustine (19).

Table 1:

Summary of the published CD30 CAR-T cells studies

| Study | No. of HL Patients | Median Age (Range), y | No. of Patients with Prior BV (%) | LDC | Costimulatory Endodomain (Vector) | Range of CAR-T Cells Ooses | Response % (n) | CRS & ICANS %(n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. Wang et al,17 | 2017 | 17 | 31 (13–55) | 423 | GEMC (n = 8) Flu + Cy (n = 5) PC (n = 4) Others (n = 4) |

4–1BB (Lenti virus) | 1.1–2.1 × 107 cells/kg | ORR 35%6

PR 35%6 |

CRS. all grades: 100%17

CRS. grade ≥3: 0% ICANS. all grades: 0% ICANS. qrade ≥3: 0% |

| Ramos et al,18 | 2017 | 7 | 31 (20–65) | 5 (71) | None | CD28 (γ-retrovirus) | 0.2–2.0 × 108 cells/m2 | ORR 29%2

CR 29%2 a |

CRS. all grades: 0% CRS. grade ≥3: 0% ICANS. all grades: 0% ICANS. qrade ≥3: 0% |

| Ramos et al,19 | 2021 | 42 | 35 (17–69) | 38 (90) | Flu + Cy (n = 17) Benda-Flu (n = 17) Benda (n = 8) |

CD28 (γ-retrovirus) | 0.2–2.0 × 108 cells/m2 | ORR 62% (23/37)b

CR 51% (19/37) PR 11% (4/37) |

CRS. all grades: 24%10

CRS. grade ≥3: 0% ICANS. all grades: 0% ICANS. grade ≥3: 0% |

Abbreviations: Benda, bendamustine; BV, brentuximab vedotin; CR, complete response; CRS. cytokine release syndrome; Flu+Cy, fludarabine + cyclophosphamide; GEMC, gemcitabine + epirubicin + mustargen + cyclophosphamide; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; ICANS, immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome; LDC. lymphodepleting chemotherapy; ORR, overall response rate; PC, nab-paclitaxel + cyclophosphamide; PR, partial response.

One patient had no active disease but maintained remission after CAR-Tcells.

Thirty-seven patients who had active disease before infusion were included in the ORR calculation.

All these trials established the safety of CD30.CARTs, with the majority of patients having mostly grade 1–2 adverse events and few experiencing higher grade events. When grade 3–4 adverse events were reported, they were predominantly cytopenias attributable to chemotherapy, as these were only seen in the trials that utilized lymphodepleting chemotherapy (17,19). In the study that did not use chemotherapy (18), patients had no significant difference in their blood counts following CD30.CAR-T infusion, except for a mild decrease in eosinophils; a finding that may be related to CD30 expression by eosinophils. As to events of special interest, the incidence of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) was variable among the studies, ranging from 0 in the trial without chemotherapy, to potentially 100%, as Wang et al. (17) reported mild febrile illness with fever and chills immediately after CAR infusion in all treated patients. The largest study reported CRS in 24% of patients (19). All CRS and febrile events were low-grade, self-limited and did not require any anti-cytokine therapy. Moreover, none of the studies reported any neurotoxicity. Finally, there was no evidence of excess infectious complications, which was a potential concern with targeting CD30 since this molecule is expressed by activated T cells that play a key role in the control of latent and acute viral infections. Anti-viral immunity appeared not to have been compromised in these patients when assessed by virus-specific ELISpot assays on PBMCs before and after CAR-T infusion (18).

Of note, one of the trials reported a transient, non-tender, non-pruritic maculopapular skin rash developing in around half of the treated patients, and more frequently in those who received cyclophosphamide (19). The rash started within one week after CAR-T cell infusion and resolved in 1 to 2 weeks without requiring specific therapy. Biopsies of the affected skin showed a non-specific spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils, and the finding was postulated to be an “on-target, off-tumor” effect of CD30.CARTs on CD30-expressing cells in the skin.

Apart from safety, these trials showed promising efficacy of the approach. In the study using CD30-BB.CARTs (17), 6 of the 17 HL patients had a partial response (PR), corresponding to an overall response rate (ORR) of 39%. The median progression-free survival (PFS) in this study was 14 months. Even without lymphodepleting chemotherapy, CD30–28.CAR-Ts showed some activity with 1 of 7 HL patients achieving a CR which lasted more than 36 months, and 1 patient maintaining a pre-treatment CR for more than 24 months after receiving CAR-Ts (18). The addition of lymphodepleting chemotherapy was associated with an increased response rate to CD30–28.CAR-Ts, which was likely related to improved in vivo expansion of the cells. Indeed, of the 37 patients who had active disease at the time of CAR-T infusion and received lymphodepleting chemotherapy prior to CD30–28.CAR-Ts, 23 had a response (ORR 62%) with 19 (51%) achieving CR. Patients who achieved remission had a median PFS of 14.6 months and 10 of these patients had not had progression at the time of publication, with the longest ongoing CR reported being 25 months. The 1-year overall survival in this patient population was 94%, which is notable given that the patients included in the study were heavily pre-treated, with a median of 7 prior lines of therapy (19).

An international multicenter phase 2 trial combining bendamustine and fludarabine lymphodepletion with CD30–28.CAR-Ts (CHARIOT trial, NCT04268706) was open to corroborate the findings of earlier studies. Initial results of the CHARIOT trial, which included 12 heavily pre-treated patients (median of 6 lines of therapy), have been presented at the American Society of Hematology (ASH) meeting (20). Efficacy data was only reported for five patients, with an ORR of 100%. Similar larger and comparative studies will be needed to determine the true efficacy of this approach. Ongoing trials of CD30-targeting CAR-T cells are included in Table 2.

Table 2:

Ongoing CD30 clinical trials in Hodgkin Lymphoma

| Target/Therapy | Identifier* | Phase of study | Type of CAR-T cells | Institution (Country) | Status** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD30 | NCT04288726 | I | Allogeneic CD30.CAR-EBVST cells | Baylor College of Medicine (United States) | Recruiting |

| NCT02259556 | I/II | Autologous CD30.CART cells | Chinese PLA General Hospital (China) | Recruiting | |

| NCT04653649 | I/II | Autologous CD30.CART cells | Fundacio Institut de Recerca de l’Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Spain) | Recruiting | |

| NCT03383965 | I | Autologous CD30.CART cells | Immune Cell, Inc. (China) | Recruiting | |

| NCT02690545 | I/II | Autologous CD30.CART | University of North Carolina (United States) | Recruiting | |

| NCT01192464 | I | Autologous CD30.CAR-EBVST cells | Baylor College of Medicine (United States) | Active, not recruiting | |

| NCT02917083 | I | Autologous CD30.CART | Baylor College of Medicine (United States) | Recruiting | |

| NCT02663297 | I | Autologous CD30.CART cells | University of North Carolina (United States) | Active, not recruiting | |

| NCT04268706 | II | Autologous CD30.CART cells | Tessa Therapeutics (Multi-center) (United States) | Active, not recruiting | |

| NCT04665063 | Not reported | Autologous CD30.CART cells | Hebei Senlang Biotechnology Inc., Ltd. (China) | Recruiting | |

| CD30 along with Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) | NCT04134325 | I | Autologous CD30.CART cells followed by ICI | University of North Carolina (United States) | Recruiting |

| NCT05352828 | I | Autologous CD30.CART cells along with ICI | Tessa Therapeutics (Multi-center) (United States) | Active, not recruiting | |

| CD30 & CCR4 | NCT03602157 | I | Autologous CD30.CART cells + CCR4 | University of North Carolina (United States) | Recruiting |

Listed on clinicaltrials.gov. Search terminology: (Hodgkin lymphoma or Hodgkin disease) and (Chimeric Antigen Receptor or CAR T cells).

Includes studies with active status (both recruiting or not recruiting).

Challenges and Future directions

Despite an impressive overall response rate, the duration of responses to CD30.CAR-Ts appears to be shorter than those that have been seen with CD19.CAR-Ts in aggressive NHL, suggesting that additional improvements are needed. Because autologous CAR-T cell products are derived from individuals who usually have been exposed to several rounds of chemotherapy, the biologic properties of these products may not be optimal. Hence, ready-made, off-the-shelf T-cell products derived from healthy donors are quite attractive, but the overall treatment strategy will have to be designed in a way that will avoid the potential complications associated with alloreactivity (i.e., product rejection and graft-versus-host disease – GVHD) (21,22). A study treating patients with CD30-positive lymphoma with CD30.CAR-transduced EBVSTs derived from healthy donors is currently ongoing at our center (BESTA trial, NCT04288726). EBVSTs are specific for EBV antigens and therefore should not be alloreactive and cause GVHD. On the other hand, because CD30 is expressed in activated T cells (including alloreactive T cells in the recipient that might mediate rejection), CD30.CAR-Ts may kill alloreactive T cells and thus be protected from rejection. Additional studies will be needed to investigate the safety and efficacy of allogeneic CAR-T cells (23).

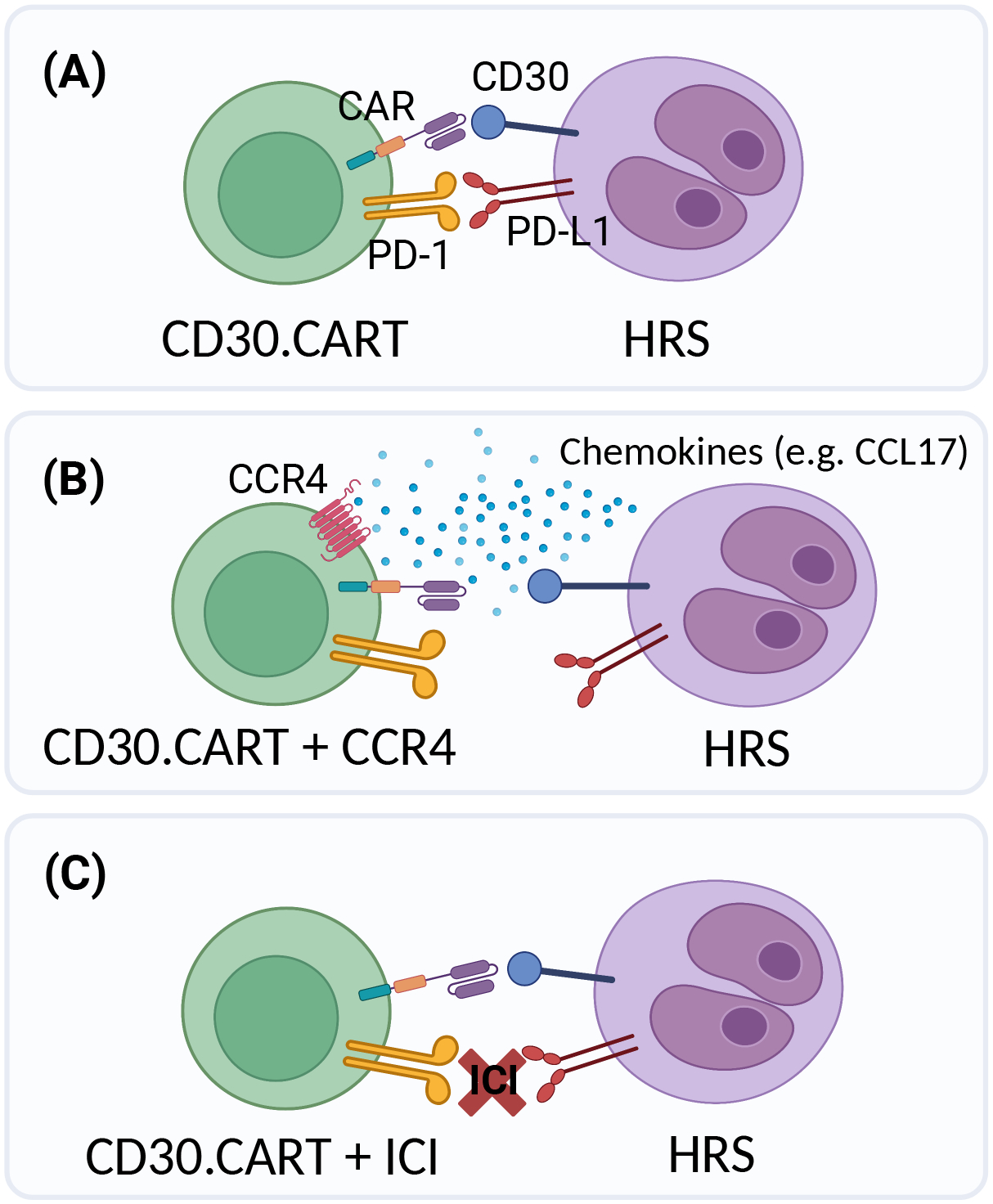

It is worth noting that patients who had received prior CD30 targeting therapy with BV were included in the studies mentioned (17–19). While the number of patients is limited, almost half of the patients whose disease had progressed while on BV achieved CR after CD30.CAR-T infusion. In addition, although post CD30.CAR-T biopsies were obtained in only a small number of patients, CD30 expression was retained in relapsing tumors (19). These findings suggest that resistance to anti-CD30 treatments is not mediated by antigen loss, but that tumor recurrence may be due to insufficient persistence of CAR-Ts within the highly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment of HL. Improving persistence in this setting is therefore desirable (see Figure 2). One possible strategy is to try to augment the efficacy of CD30 CAR-T cells by combining them with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI). CD30.CAR-T cells express programmed death-1 (PD-1) and thus are susceptible to the inhibition by PD-1 ligand. This inhibition could potentially be evaded by administering an ICI before or after CD30 CAR-Ts (e.g., NCT04134325), or by producing CAR-T cells that do not express PD-1. Other approaches, still in early phases, include enhancing CD30.CAR-T trafficking to tumors by co-expressing CCR4 (the receptor for CCL17, which is secreted in high amounts by HRS), and additionally targeting the immunosuppressive HL microenvironment using CD19 and CD123-specific CAR-Ts (9, 24–26).

Figure 2:

Different potential strategies of targeting CD30 using CAR-T cells are shown: (A) CD30.CARTs, (B) CD30.CARTs co-expressing CCR4 (CCL17 receptor), or (C) administering it along with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI). CCL17 is one of the chemokines secreted by HRS that is thought to attract immunosuppressive effector cells, such as regulatory T cells, to the tumor microenvironment. Expressing CCR4 in CAR-T cells takes advantage of an ordinarily immune inhibitory mechanism. (Figure created with BioRender.com)

Further studies are also required to optimize other aspects of CAR-T administration, such as defining the optimal lymphodepleting therapy. Additionally, work investigating the effects of CD30 CAR-Ts on tumor CD30 expression and clinical predictors of response is needed (27,28).

CAR-T Cells in T-cell Lymphoma

TCLs are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms that, in general, have a worse prognosis when compared to B-cell NHL and HL, and for which treatment options (particularly in r/r settings) are limited and exhibit only modest efficacy (29). The success of adoptive T-cell therapies in B-cell malignancies has led to an interest in applying them in TCL; however, the biology of TCLs creates new challenges, including the potential fratricide and profound immunodeficiency that may be associated with a CAR targeting a universal T-cell antigen.

Several strategies have been exploited to prevent fratricide during CAR-T manufacture, including disrupting gene expression in T cells via CRISPR or other gene editing methods (30,31), or preventing surface expression of the target antigen by inducing its retention in the endoplasmic reticulum (32,33). Additionally, Watanabe et al. showed that the expansion of CAR-Ts in the presence of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (ibrutinib and dasatinib) prevents global fratricide while allowing the production of functional CAR-Ts against the universal T-cell marker CD7 without additional cell engineering (34), suggesting another potential manufacturing method.

Other recent studies have highlighted that a population of T cells that are natively negative for the antigen targeted can be selected in culture after CAR transduction or in vivo after infusion. In vivo expansion of naturally CD7-negative T cells that express a CD7.CAR and are fratricide-resistant due to the lack of antigen expression appears to be an important mechanism for CD7.CAR-Ts persistence described by Watanabe et al. (34). In addition, some CARs may spontaneously induce intracellular sequestration or masking of their cognate antigen and thus allow the emergence of an antigen-negative CAR-T population in culture as has been described with CD5.CARs (35).

Finally, the potential risk of transduction of circulating tumor cells with the CAR needs to be considered. Many of the manufacture protocols include a selection step to try to eliminate any tumor cells in the starting culture or, at a minimum, a screening step to rule out the presence of malignant cells in the final product.

CD30.CAR-T cells in T-cell lymphomas

As CD30 is highly expressed in a subset of TCLs and BV has improved outcomes in these patients (36), CD30.CAR-Ts are currently being studied in CD30-positive TCL patients. While all of the studies discussed in the prior section allowed enrollment of CD30+ TCL patients, current published results include only 3 patients: 2 with cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) and 1 with systemic ALK-positive ALCL (17,18). Two patients had at least partial response, with the ALK+ ALCL patient achieving and maintaining remission for nine months. The data on using CD30.CARs in TCL is encouraging but CD30 expression is restricted to a small subset of TCLs and thus applicable to a limited group of patients.

CD5.CAR-T cells in T-cell lymphomas

CD5 is a member of the scavenger receptor cysteine-rich (SRCR) superfamily that is expressed on the surface of 85–95% of TCLs depending on the disease subtype, with expression otherwise limited to normal T cells, a small subset of B cells (B1a cells), and thymocytes (6,37). Based on its broad expression across multiple T-cell malignancies, CD5 was identified as a potential therapeutic target, with early studies investigating the use of a murine mAb for treatment of r/r T-cell malignancies (primarily cutaneous TCLs) (38,39). While the efficacy was marginal, no severe or irreversible toxicities were observed, providing proof of concept that CD5 could be targeted without dire consequences. Nearly 25 years later, researchers at BCM published the first preclinical data using a second-generation CD28-containing CD5.CAR demonstrating that CD5.CAR-Ts were able to expand and persist in vitro and in vivo with limited fratricide (35), likely due to intracellular sequestration and degradation of CD5 when it is bound by the CAR in a transduced cell. The CAR-Ts were also able to eliminate T-ALL in xenograft mouse models. These preclinical results supported the clinical development of CD5.CAR-Ts for CD5-positive T-cell malignancies.

At the time of this writing, there are currently 7 early-phase trials registered on Clinicaltrials.gov exploring the use of CD5.CAR-Ts for T-cell malignancies. However, only 4, of which 2 are actively recruiting (USA: BCM; China: Peking University), include TCLs. Preliminary findings from the BCM trial (NCT030381910) utilizing autologous CD5.CARTs in patients with r/r T-ALL and TCL were encouraging (40,41). Results of the first 9 treated TCL patients were presented at the 2021 ASH annual meeting (42). Disease subtypes included PTCL, angioimmunoblastic TCL (AITL), cutaneous TCL, and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL). Enrolled patients had been heavily treated, with a median of 5 lines of prior therapy. All received standard lymphodepletion with cyclophosphamide and fludarabine followed by infusion of CD5.CAR-Ts. Responses were seen on all dose levels, in 4 of 9 patients, with 2 CR, 1 PR, and 1 mixed response initially (all prior disease resolved with appearance of one new lesion) (42). Two patients remain alive over 2 years post infusion. No severe CAR-T mediated toxicities were observed, with 4 patients experiencing CRS (grade 1–2) and 1 patient having grade 2 neurotoxicity (concurrent with grade 2 CRS). None of the patients had severe infections. Count recovery occurred by day 28 in most patients; however, 3 patients did experience prolonged cytopenias. The safety of CD5.CAR-Ts was also demonstrated in T-ALL patients (43).

CD7.CAR-T cells in T-cell lymphomas

CD7 is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily with broad surface expression in T-cell malignancies, including more than 90% of T-ALL. Its expression is, however, variable in TCL depending on the subtype; in AITL and ALCL it exceeds 50% (6,44). Similar to CD5 mAb, targeting CD7 with a toxin-conjugated mAb showed modest responses, but its use was limited owing to capillary leak syndrome, which was thought to be related to the toxin (45). In contrast to CD5.CAR, several preclinical studies of CD7.CAR-Ts demonstrated substantial fratricide (30–32), a major limiting factor for their potential applicability. Several phase 1 clinical trials using CD7.CAR-Ts to treat T-cell malignancies and exploiting various strategies to avoid fratricide have been published. However, most of the studies currently available primarily include patients with r/r T-ALL, with few studies including TCL patients (46–48).

Hu et al. reported the results of 12 patients (NCT04538599) treated with allogeneic donor-derived CD7-negative CAR-Ts generated with CD7 and TCR/CD3 knockout via CRISPR/Cas9 (47). Four of the patients were categorized as TCL and included 2 patients with T-LBL and 1 patient each with PTCL NOS and EBV+ NK/TCL. The patient with PTCL NOS achieved complete remission and a partial response was observed in the patient with EBV+ NK/TCL and in one patient with T-LBL. Unfortunately, the patient with PTCL NOS developed EBV-associated PTLD ~55 days post-infusion and died of progressive disease despite treatment with rituximab. The majority of the patients (83%) developed grade 1–2 CRS, but none developed ICANS or GVHD after a median follow-up of 10.5 months.

In an effort to limit the need for gene editing, Lu et al. investigated the role of naturally selected CD7-negative T cells in 20 patients with T-ALL (n=14) or T-LBL (n=6) (48). Sixteen patients with bone marrow involvement (94%) achieved CR with negative MRD by day 28 post-infusion, while 5 of 9 patients with extramedullary disease had an extramedullary CR at a median time of 29 days (range 15–51). CRS occurred in >90% of patients, but only one case developed grade 3 CRS. Fourteen patients received subsequent allo-HSCT, of which ten were for remission consolidation. Others have also reported impressive responses in r/r T-ALL with an overall encouraging safety profile (49).

BCM currently has an ongoing phase 1 trial (CRIMSON; NCT03690011) that is currently recruiting patients with TCL. The trial utilizes non-edited autologous CD7.CAR-Ts manufactured in the presence of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, based on the previously described preclinical work (34). Preliminary findings include 2 patients with TCL (AITL and CTCL) who achieved a CR and very good PR, respectively (unpublished data). Other studies are ongoing, the results of which are eagerly awaited.

Challenges and Future Directions

Individual subtypes of TCLs are rare and have distinct clinical behaviors posing real challenges to the interpretation of antitumor activity of CAR-Ts in this setting. Longer follow-up and larger studies are needed to confirm the long-term safety and efficacy of CAR-Ts in TCL in general and in each specific type of TCL.

Even if fratricide can be circumvented in culture and in vivo, the profound immunosuppression caused by potential T-cell aplasia is problematic. The studies published to date have not shown that CD5/7.CAR-T cells are associated with a higher rate of severe infectious complications, but fatal post CD7.CAR-T EBV-related PTLD has been reported in one patient (47). In an effort to avoid potentially prolonged immunosuppression, several trials are utilizing CAR-T cells in T-cell malignancies as a bridge to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (and concurrent immune ablation that should lead to CAR-T eradication) until more data is available on the extent of immunosuppression, infectious complications, as well as the durability of responses. Another potential strategy to ablate CAR-Ts on demand in case of toxicities is the inclusion of a suicide switch, such as an inducible caspase 9, in the CAR construct (50). An alternative approach takes advantage of the mutually exclusive expression of β-chain constant region types (TRBC1 or TRBC2) in the TCRs of normal T cells versus the expression of a single type of constant region in the TCR of malignant T cells (which are monoclonal). Selectively targeting malignant TRBC1+ T cells will spare native TRBC2+ T cells (and vice-versa), preventing global T-cell aplasia and potentially avoid severe immunodeficiency (51).

Although our discussion was limited to the use of CD30, CD5 and CD7-targeting CAR-Ts (see Table 3), other targets are being investigated, including CD3, CD4, and CCR4 together with CD30 (6,7,52). Table 4 includes examples of ongoing studies investigating the use of CAR-Ts against different targets in TCL.

Table 3:

Summary of available results from CD5 and CD7 CAR-T cell studies

| Study | Total No. Patients (No. TCL Patients) | Median Age (Range), y | Target (CAR Type) | Subtypes of TCL | LDC | Costimulatory Endodomain (Vector) | Range of CAR-T Cells Doses | Responses % (n) | CRS & ICANS % (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD5 | ||||||||||

| Rouce et al.42 | 2021 | 99 | 63 (27–71) | CD5 (Autologous) | PTCL (n = 4) AITL (n = 2) CTCL (n = 2) ATLL (n = 1) |

Flu + Cy | CD28 (γ-retrovirus) | 0.1–1.0 × 108 cells/m2 | ORR 44%4

CR 33%3,a PR 11%1 |

CRS, all grades: 44%4

CRS, grade ≥3: 0% ICANS, all grades: 11%1 ICANS, grade ≥3: 0% |

| Pan et al.43 | 2022 | 5 (0) | NR | CD5 (donor-derived) | N.A | NR | 4–1BB (Lentivirus) | 0.5–1.0 × 106 cells/kg | ORR 100%5

CR 100%5 |

CRS 80%4

CRS, grade ≥3: 0% ICANS, all grades: NR ICANS, grade ≥3: NR |

| CD7 | ||||||||||

| Zhang et al.46 | 2023 | 105 | 32 (16–69) | CD7 (autologous or donor-derived) | AITL (n = 1) CTCL (n = 1) TLBL (n = 3) |

Flu + Cy | 4–1BB (Lentivirus) | 1.0–2.0 × 106 cells/kg | ORR 70% (7/10)b | CRS, all grades: 80%8

CRS, grade ≥3: 10%1 ICANS, all grades: 0% ICANS, grade ≥3: 0% |

| Hu et al,47 | 2022 | 124 | 34 (8–66) | CD7 (donor-derived) | PTCL, NOS (n = 1) EBV + NK/TCL (n = 1) TLBL (n = 2) |

Flu + Cy + Etop | 4–1BB (Lentivirus) | 2 × 107 cells/kg | ORR 75% (9/12) CR 58% (7/12)c PR 17% (2/12) |

CRS, all grades: 83%10

CRS, grade ≥3: 0% ICANS, all grades: 0% ICANS, grade ≥3: 0% |

| Lu et al,48 | 2022 | 206 | 223–47 | CD7 (autologous or donor-derived) | TLBL (n = 6) | Flu + Cy | 4–1BB (Lentivirus) | 0.5–2.0 × 106 cells/kg | ORR 95% (19/20) CR 80% (16/20) PR 10% (2/20) |

CRS, all grades: 95%19

CRS, grade ≥3: 5%1 ICANS, all grades: 10%2 ICANS, grade ≥3: 0% |

| Pan et al,49 | 2022 | 20 (0) | 112–43 | CD7 (donor-derived) | N.A | Flu + Cy | 4–1BB (Lentivirus) | 0.5–1.0 × 106 cells/kg | ORR 95% (19/20) CR 90% (18/20) PR 5% (1/20) |

CRS, all grades: 100%20

CRS, grade ≥3: 10%2 ICANS all grades: 15%3 ICANS, grade ≥3: 0% |

Abbreviations: AITL, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; ATLL, adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma; CR, complete response; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; CTCL, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; Cy-flu, cyclophosphamide+ fludarabine; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; EBV+ NK/TCL, EBV-associated NK/T-cell lymphomap; Etop, etoposide; ICANS, immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome; LDC, lymphodepleting chemotherapy; NOS, not otherwise specified; NR, not reported; ORR, overall response rate; PR, partial response; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; TCL, T-cell lymphoma.

Two AITL and one PTCL achieved CR. ATLL patient achieved PR; result details were provided courtesy of Dr. LaQuisa Hill.

Details on CR and PR rates were not clear. CTCL patient achieved PR. No individual data were reported about the AITL patient.

One PTCL, NOS patient achieved CR, and one EBV+ NK/TCL achieved PR.

Table 4:

Examples of CAR-T cells clinical trials in T-cell Lymphomas

| Target* | Identifier | Phase of study | Type of CAR-T cells | Institution/Sponsor (Country) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD30 | NCT04952584 | I | Allogeneic CD30.CAR-EBVST cells | Baylor College of Medicine (United States) | Recruiting |

| NCT04083495 | II | Autologous CD30.CART cells | University of North Carolina (United States) | Recruiting | |

| NCT02917083 | I | Autologous CD30.CART cells | Baylor College of Medicine (United States) | Recruiting | |

| CD30 & CCR4 | NCT03602157 | I | Autologous CD30.CART cells +CCR4 | University of North Carolina (United States) | Recruiting |

| CD5 | NCT03081910 | I | Autologous CD5.CART cells | Baylor College of Medicine (United States) | Recruiting |

| NCT04594135 | I | CD5.CART cells | iCell Gene Therapeutics/Peking University People’s Hospital (China) | Recruiting | |

| CD7 | NCT03690011 | I | Autologous CD7.CART cells | Baylor College of Medicine (United States) | Recruiting |

| NCT05059912 | II | CD7.CART cells | The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (China) | Recruiting | |

| NCT04823091 | I | Donor-derived CD7.CART cells | Wuhan Union Hospital (China) | Recruiting | |

| NCT05290155 | I | CD7.CART cells | Shanghai General Hospital (China) | Recruiting | |

| NCT05377827 | I | Allogeneic CD7.CART cells | Washington University School of Medicine (USA) | Not yet recruiting | |

| CD37 | NCT04136275 | I | Autologous CD37.CART cells | Massachusetts General Hospital (United States) | Recruiting |

| CD4 | NCT04162340 | I | Autologous CD4.CART cells | iCell Gene Therapeutics (China) | Recruiting |

| NCT04712864 | I | Autologous CD4.CART cells | Legend Biotech USA Inc (Multi-center) (United States) | Active, not recruiting | |

| CD147 | NCT05013372 | Early phase I | CD147.CART cells | Peking University People’s Hospital (China) | Not yet recruiting |

This table includes examples of studies investigating each target and not inclusive of all the ongoing studies listed on clinicaltrials.gov.

Conclusions

CAR-T cells have improved outcomes in several lymphoproliferative diseases, in particular CD19 and BCMA-positive malignancies. The use of CAR-T cells is likely to expand over the next few decades, with applications to other hematological and solid tumors. CD30.CAR-T cells have promising safety and activity in r/r HL, with early-phase clinical trial data supporting CD30 as a therapeutic target for CAR-T cells in this disorder. Clinical data of CAR-T cells for r/r TCLs are much less mature. Malignant T cells widely express CD5 and CD7, which are potential targets for CAR-T cells. However, further research in the treatment of these disorders with CAR-Ts is needed to address potential challenges, including fratricide and cellular immunodeficiency.

Synopsis:

We review the current use of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-transduced T cells (CAR-T) in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and T-cell lymphomas (TCL) and discuss the data on CD30-targeting CAR-T cells, which appear to be safe and effective in HL. Additionally, we examine the use of CAR-T cells targeting CD30, CD5 or CD7 in TCL, while highlighting the unique challenges of their use in this subset of lymphomas. Furthermore, we present future directions and ongoing trials investigating the use of CAR-T cells in TCL and HL.

Key Points:

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells have improved outcomes in several lymphoproliferative diseases, including B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (CD19.CAR-T cells), and multiple myeloma (BCMA.CAR-T cells).

CD30.CAR-T cells have shown safety and promising efficacy in relapsed/refractory (r/r) Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), with early-phase clinical trial data supporting CD30 as a potential target for CAR-T cells in HL.

Efforts to improve the antitumor activity of CD30.CAR-T cells in r/r HL with additional genetic modification or combination treatment (e.g., with immune check point inhibitors) are ongoing.

Several potential targets have been identified for T-cell lymphomas (TCLs) and CAR-T cells targeting broadly expressed antigens, such as CD5 and CD7, are currently being explored as treatment for r/r TCL.

CAR-T cell use in TCL is still in early development stages, and more research is needed to address potential challenges, including the risks of fratricide, prolonged cellular immunodeficiency, and transduction of malignant T cells.

Acknowledgement:

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute grants P50 CA126752 and P30 CA125123, and a Specialized Center of Research grant from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

Conflict of interest:

L.C.H. has consulted for March Biosciences, is a member of Speakers Bureau for Kite/Gilead, and served on advisory board for Incyte. C.A.R. has participated in advisory boards for Novartis, Genentech and CRISPR Therapeutics, and has received research funding from Athenex and Tessa Therapeutics. I.N.M. declares no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Ansell SM, Radford J, Connors JM, et al. ECHELON-1 Study Group. Overall Survival with Brentuximab Vedotin in Stage III or IV Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022. Jul 28;387(4):310–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen R, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Five-year survival and durability results of brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2016;128(12):1562–1566. 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moskowitz CH, Nademanee A, Masszi T, et al. ; AETHERA Study Group. Brentuximab vedotin as consolidation therapy after autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma at risk of relapse or progression (AETHERA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9980):1853–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hombach A, Heuser C, Sircar R, et al. An anti-CD30 chimeric receptor that mediates CD3-zeta-independent T-cell activation against Hodgkin’s lymphoma cells in the presence of soluble CD30. Cancer Res. 1998. Mar 15;58(6):1116–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savoldo B, Rooney CM, Di Stasi A, et al. Epstein Barr virus specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes expressing the anti-CD30zeta artificial chimeric T-cell receptor for immunotherapy of Hodgkin disease. Blood. 2007. Oct 1;110(7):2620–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scherer LD, Brenner MK, Mamonkin M. Chimeric Antigen Receptors for T-Cell Malignancies. Front Oncol. 2019. Mar 5;9:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safarzadeh Kozani P, Safarzadeh Kozani P, Rahbarizadeh F. CAR-T cell therapy in T-cell malignancies: Is success a low-hanging fruit? Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021. Oct 7;12(1):527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engert A, Plutschow A, Eich HT, et al. Reduced treatment intensity in patients with early-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(7): 640–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho C, Ruella M, Levine BL, et al. Adoptive T-cell therapy for Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2021. Oct 26;5(20):4291–4302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doubrovina E, Oflaz-Sozmen B, Prockop SE, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy with unselected or EBV-specific T cells for biopsy-proven EBV1 lymphomas after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;119(11):2644–2656. 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heslop HE, Slobod KS, Pule MA, et al. Long-term outcome of EBV-specific T-cell infusions to prevent or treat EBV-related lymphoproliferative disease in transplant recipients. Blood. 2010;115(5):925–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bollard CM, Aguilar L, Straathof KC, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte therapy for Epstein-Barr virus+ Hodgkin’s disease. J Exp Med. 2004. Dec 20;200(12):1623–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Weyden CA, Pileri SA, et al. Understanding CD30 biology and therapeutic targeting: a historical perspective providing insight into future directions. Blood Cancer J. 2017. Sep 8;7(9):e603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horie R, Watanabe T, Morishita Y, et al. Ligandindependent signaling by overexpressed CD30 drives NF-kappaB activation in Hodgkin–Reed–Sternberg cells. Oncogene 2002; 21: 2493–2503. 48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch B, Hummel M, Bentink S, et al. CD30- induced signaling is absent in Hodgkin’s cells but present in anaplastic large cell lymphoma cells. Am J Pathol 2008; 172: 510–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grover NS, Savoldo B. Challenges of driving CD30-directed CAR-T cells to the clinic. BMC Cancer. 2019. Mar 6;19(1):203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang CM, Wu ZQ, Wang Y, et al. Autologous T Cells Expressing CD30 Chimeric Antigen Receptors for Relapsed or Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma: An Open-Label Phase I Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2017. Mar 1;23(5):1156–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramos CA, Ballard B, Zhang H, et al. Clinical and immunological responses after CD30-specific chimeric antigen receptor-redirected lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 2017. Sep 1;127(9):3462–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramos CA, Grover NS, Beaven AW, et al. Anti-CD30 CAR-T Cell Therapy in Relapsed and Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020. Nov 10;38(32):3794–3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed S, Flinn I, Mei M, et al. Safety and efficacy profile of autologous CD30.CAR-T-Cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHARIOT trial). Blood (2021) 138(Supplement 1):3847–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao J, Lin Q, Song Y, Liu D. Universal CARs, universal T cells, and universal CAR-T cells. J Hematol Oncol. 2018; 11:132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martínez Bedoya D, Dutoit V, Migliorini D. Allogeneic CAR-T Cells: An Alternative to Overcome Challenges of CAR-T Cell Therapy in Glioblastoma. Frontiers in Immunology. 2021;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Depil S, Duchateau P, Grupp SA, et al. “Off-the-shelf” allogeneic CAR-T cells: development and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020; 19:185–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ullah F, Dima D, Omar N, et al. Advances in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma: Current and future approaches. Front Oncol. 2023. Mar 3;13:1067289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meier JA, Savoldo B, Grover NS. The Emerging Role of CAR T Cell Therapy in Relapsed/Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma. J Pers Med. 2022. Feb 1;12(2):197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Stasi A, De Angelis B, Rooney CM, et al. T lymphocytes coexpressing CCR4 and a chimeric antigen receptor targeting CD30 have improved homing and antitumor activity in a Hodgkin tumor model. Blood. 2009. Jun 18;113(25):6392–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marques-Piubelli ML, Kim DH, et al. CD30 expression is frequently decreased in relapsed classic Hodgkin lymphoma after anti-CD30 CAR T-cell therapy. Histopathology. 2023. Mar 30. doi: 10.1111/his.14910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voorhees TJ, Zhao B, Oldan J, et al. Pretherapy metabolic tumor volume is associated with response to CD30 CAR T cells in Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2022. Feb 22;6(4):1255–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foss FM, Zinzani PL, Vose JM, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Blood 2011;117(25):6756–6767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gomes-Silva D, Srinivasan M, Sharma S, et al. CD7-edited T cells expressing a CD7-specific CAR for the therapy of T-cell malignancies. Blood. (2017) 130:285–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper ML, Choi J, Staser K, et al. An “off-the-shelf” fratricide-resistant CAR-T for the treatment of T cell hematologic malignancies. Leukemia. 2018. Sep;32(9):1970–1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Png YT, Vinanica N, Kamiya T, et al. Blockade of CD7 expression in T cells for effective chimeric antigen receptor targeting of T-cell malignancies. Blood Adv. (2017) 1:2348–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang M, Chen D, Fu X, et al. Autologous Nanobody-Derived Fratricide-Resistant CD7-CAR T-cell Therapy for Patients with Relapsed and Refractory T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia/Lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2022. Jul 1;28(13):2830–2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watanabe N, Mo F, Zheng R, et al. Feasibility and preclinical efficacy of CD7-unedited CD7 CAR T cells for T cell malignancies. Mol Ther. 2023. Jan 4;31(1):24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mamonkin M, Rouce RH, Tashiro H, et al. A T-Cell-Directed chimeric antigen receptor for the selective treatment of T-cell malignancies. Blood (2015) 126(8):983–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horwitz S, O’Connor OA, Pro B, et al. ECHELON-2 Study Group. Brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy for CD30-positive peripheral T-cell lymphoma (ECHELON-2): a global, double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019. Jan 19;393(10168):229–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campana D, van Dongen JJ, Mehta A, et al. Stages of T-cell receptor protein expression in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1991;77(7):1546–1554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertram JH, Gill PS, Levine AM, et al. Monoclonal antibody T101 in T cell malignancies: a clinical, pharmacokinetic, and immunologic correlation. Blood. 1986. Sep;68(3):752–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.LeMaistre CF, Rosen S, Frankel A, et al. Phase I trial of H65-RTA immunoconjugate in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1991;78(5):1173–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hill LC, Rouce RH, Smith TS, et al. Safety and anti-tumor activity of CD5 car T-cells in patients with Relapsed/Refractory T-cell malignancies. Blood. 2019; 134 (Supplement_1): 199.31064751 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hill L, Rouce RH, Smith TS, et al. CD5 CAR T-Cells for Treatment of Patients with Relapsed/Refractory CD5 Expressing T-Cell Lymphoma Demonstrates Safety and Anti-Tumor Activity. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2020;26. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rouce RH, Hill LC, Smith TS, et al. Early Signals of Anti-Tumor Efficacy and Safety with Autologous CD5.CAR T-Cells in Patients with Refractory/Relapsed T-Cell Lymphoma. Blood 2021; 138 (Supplement 1): 654. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pan J, Tan Y, Shan L, et al. Phase I study of donor-derived CD5 CAR T cells in patients with relapsed or refractory T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2022. 40:16_suppl, 7028–7028. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei W, Yang D, Chen X, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for T-ALL and AML. Front Oncol. 2022. Nov 29;12:967754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frankel AE, Laver JH, Willingham MC, et al. Therapy of patients with T-cell lymphomas and leukemias using an anti-CD7 monoclonal antibody-ricin A chain immunotoxin. Leuk Lymphoma. 1997. Jul;26(3–4):287–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y, Li C, Du M, et al. Allogenic and autologous anti-CD7 CAR-T cell therapies in relapsed or refractory T-cell malignancies. Blood Cancer J. 2023. Apr 25;13(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu Y, Zhou Y, Zhang M, et al. Genetically modified CD7-targeting allogeneic CAR-T cell therapy with enhanced efficacy for relapsed/refractory CD7-positive hematological malignancies: a phase I clinical study. Cell Res. 2022. Nov;32(11):995–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu P, Liu Y, Yang J, et al. Naturally selected CD7 CAR-T therapy without genetic manipulations for T-ALL/LBL: first-in-human phase 1 clinical trial. Blood. 2022. Jul 28;140(4):321–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pan J, Tan Y, Wang G, et al. Donor-Derived CD7 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells for T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: First-in-Human, Phase I Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021. Oct 20;39(30):3340–3351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Di Stasi A, Tey SK, Dotti G, et al. Inducible apoptosis as a safety switch for adoptive cell therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011. Nov 3;365(18):1673–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maciocia PM, Wawrzyniecka PA, Philip B, et al. Targeting the T cell receptor beta-chain constant region for immunotherapy of T cell malignancies. Nat Med 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hill L, Lulla P, Heslop HE. CAR-T cell Therapy for Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas: A New Treatment Paradigm. Adv Cell Gene Ther. 2019. Jul;2(3):e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]