Abstract

This work shows that the ribC wild-type gene product has both flavokinase and flavin adenine dinucleotide synthetase (FAD-synthetase) activities. RibC plays an essential role in the flavin metabolism of Bacillus subtilis, as growth of a ribC deletion mutant strain was dependent on exogenous supply of FMN and the presence of a heterologous FAD-synthetase gene in its chromosome. Upon cultivation with growth-limiting amounts of FMN, this ribC deletion mutant strain overproduced riboflavin, while with elevated amounts of FMN in the culture medium, no riboflavin overproduction was observed. In a B. subtilis ribC820 mutant strain, the corresponding ribC820 gene product has reduced flavokinase/FAD-synthetase activity. In this strain, riboflavin overproduction was also repressed by exogenous FMN but not by riboflavin. Thus, flavin nucleotides, but not riboflavin, have an effector function for regulation of riboflavin biosynthesis in B. subtilis, and RibC seemingly is not directly involved in the riboflavin regulatory system. The mutation ribC820 leads to deregulation of riboflavin biosynthesis in B. subtilis, most likely by preventing the accumulation of the effector molecule FMN or FAD.

Various Bacillus species have gained increasing importance as host strains for industrial fermentation processes for, e.g., proteases, purine nucleotides, or vitamins (1, 37, 39). Recently, a commercially attractive riboflavin production process using Bacillus subtilis Marburg 168 as a host strain has been developed. This strain was optimized for riboflavin production by means of classical mutagenesis procedures and genetic engineering techniques (34). The genes encoding the riboflavin biosynthetic enzymes of B. subtilis were found to be clustered in a single 4.3-kbp operon (rib operon) which was mapped at 209° of the B. subtilis chromosome (29, 30, 33). The gene products of the rib operon (RibG, RibB, RibA, and RibH) catalyze the conversion of GTP and ribulose-5-phosphate to riboflavin (2, 5, 33).

An untranslated rib leader sequence of almost 300 nucleotides is present in the 5′ region of the rib operon between the transcription start and the translational start codon of the first rib gene (ribG). One class of riboflavin-overproducing B. subtilis mutants identified contained single-point mutations, designated ribO mutations, at various positions in the 5′ half of the rib leader sequence (23, 31). A potential rho-independent terminator is present at the 3′ end of the rib leader sequence (23, 29), suggesting that riboflavin biosynthesis in B. subtilis may be regulated by a transcription attenuation mechanism.

In a second class of riboflavin-overproducing mutants, designated ribC mutants, the chromosomal lesions were mapped at 147° (25). It was suggested that the riboflavin regulatory system in B. subtilis consists of a cis-acting operator element in the rib leader sequence, defined by the ribO mutations, and a trans-acting DNA- or RNA-binding repressor protein encoded by the ribC gene (26).

The ribC gene was recently cloned and sequenced. Surprisingly, the gene was found to have significant sequence similarities to bifunctional bacterial flavokinases/flavin adenine dinucleotide synthetases (FAD-synthetases) (12, 17). Flavokinases (EC 2.7.1.26) catalyze the conversion of riboflavin to FMN; FAD-synthetases (EC 2.7.7.2) convert FMN to FAD (3). In the present work, it is shown that ribC encodes a bifunctional flavokinase/FAD-synthetase which is essential for B. subtilis flavin metabolism. The gene product of a ribC mutant allele (ribC820), which leads to riboflavin overproduction in B. subtilis RB52 (12), has drastically reduced enzymatic activity. It is demonstrated that FMN and/or FAD, but not riboflavin, act as effector molecules controlling riboflavin biosynthesis. We present a model which explains the riboflavin overexpression phenotype of B. subtilis ribC mutant strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains used in this study are described in Table 1. B. subtilis 1012 is a wild-type strain with respect to riboflavin biosynthesis (35). B. subtilis 1012MM002 contains Escherichia coli ribF at sacB. B. subtilis 1012MM003 contains Saccharomyces cerevisiae FADI at sacB. B. subtilis 1012MM004 contains E. coli ribF at sacB, and B. subtilis ribC is replaced by a neomycin cassette. B. subtilis 1012MM006 contains S. cerevisiae FADI at sacB, and B. subtilis ribC is replaced by a neomycin cassette. B. subtilis 1012mro87 has a mutation within the ribO region which leads to riboflavin overproduction (23). B. subtilis RB52 (34) has a mutation within the ribC gene (ribC820) (12) that as well leads to riboflavin overproduction. B. subtilis RB52MM100 contains B. subtilis ribC at sacB. B. subtilis RB52MM110 contains B. subtilis ribC820 at sacB. All genes that were introduced at sacB (ribC, ribC820, ribF, and FADI) are under the control of the medium-strength PvegI promoter (20). B. subtilis RB52p210 contains the B. subtilis ribC locus at sacB. B. subtilis RB52p211 contains the B. subtilis ribC820 locus at sacB (11). In the latter two strains, ribC and ribC820 are under the control of the original promoter. E. coli XL1-Blue (10) and BL21 (40) were used as hosts for gene cloning and expression experiments, respectively. E. coli BL21MM01 contains ribC on plasmid pJF119HE (15). E. coli BL21MM02 contains ribC820 on plasmid pJF119HE.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype, antibiotic resistance, or relevant feature(s)a | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| B. subtilis | ||

| 1012 | leuA8 metB5 | 35 |

| 1012MM002 | 1012 PvegI ribF ermAM @ sacB | This study |

| 1012MM003 | 1012 PvegI FADI ermAM @ sacB | This study |

| 1012MM004 | 1012 ΔribCΩneo PvegI ribF ermAM @ sacB | This study |

| 1012MM006 | 1012 ΔribCΩneo PvegI FADI ermAM @ sacB | This study |

| 1012mro87 | Riboflavin-secreting ribO mutant (G37 GG→A37AA) | 23 |

| RB52 | Dcr-15 ribC820 guaC3 metC7 trpC2 | 34 |

| RB52MM100 | RB52 PvegI ribC ermAM @ sacB | This study |

| RB52MM110 | RB52 PvegI ribC820 ermAM @ sacB | This study |

| RB52p210 | RB52 ribC locus @ sacB | 12 |

| RB52p211 | RB52 ribC820 locus @ sacB | 12 |

| E. coli | ||

| BL21 | Used for gene cloning and expression | 40 |

| BL21MM01 | E. coli BL21 containing pMM01 | This study |

| BL21MM02 | E. coli BL21 containing pMM02 | This study |

| XL1-Blue | Used for gene cloning | 10 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescriptII SK− | High-copy-number cloning vector, amp | Stratagene |

| pJF119HE | Low-copy-number expression vector, amp Ptac lacIq | 15 |

| pMM01 | pJF119HE containing a 1.143-kbp BamHI/EcoRI fragment carrying B. subtilis ribC | This study |

| pMM02 | pJF119HE containing a 1.143-kbp BamHI/EcoRI fragment carrying B. subtilis ribC820 | This study |

| pMM10 | pIXI12 containing a 1.073-kbp NdeI/EcoRI fragment carrying B. subtilis ribC | This study |

| pMM11 | pIXI12 containing a 1.073-kbp NdeI/EcoRI fragment carrying B. subtilis ribC820 | This study |

| pMM20 | pIXI12 containing a 0.960-kbp NdeI/EcoRI fragment carrying E. coli ribF | This study |

| pMM30 | pIXI12 containing a 0.955-kbp NdeI/EcoRI fragment carrying S. cerevisiae FADI | This study |

| pMM60 | pBluescriptSK− containing a 2.609-kbp XhoI/SpeI fragment carrying the B. subtilis ribC locus; ribC of this locus was replaced by a neomycin resistance cassette (21) | This study |

| pXI12 | pBR322 sacB5′ ermAM cryT RBS PvegI sacB3′ amp; B. subtilis integration/expression vector | 20 |

Abbreviations: amp, ampicillin resistance cassette; @ sacB, integration of genes by homologous double-crossover recombination at B. subtilis sacB (296°); Dcr-15, decoyinine resistance; ermAM, erythromycin resistance cassette; FADI, FAD-synthetase gene from S. cerevisiae; guaC3, 8-azaguanine resistance; leuA8, leucine auxotroph; metB5, methionine auxotroph; metC7, methionine auxotroph; neo, neomycin resistance cassette; PvegI, medium-strength vegI promoter; ribC, B. subtilis flavokinase/FAD-synthetase gene; ribC820, ribC gene with mutation G820A; ribF, E. coli flavokinase/FAD-synthetase gene; trpC2, tryptophan auxotroph.

All bacteria were grown aerobically at 37°C on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or Spizizen’s minimal medium (38). FMN (100 μM) was added for the growth of the auxotrophic B. subtilis strain 1012MM006. Commercially available FMN (sodium salt; Sigma F2253) was >99% (wt/wt) 5′-FMN after additional purification by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Construction of plasmids.

The plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. Plasmid pBluescript II SK− (Stratagene) was used for cloning procedures. Plasmid pJF119HE (15) was used for the overexpression of ribC in E. coli.

For gene expression, ribC was amplified by PCR from chromosomal DNA of B. subtilis 1012, using oligonucleotides BamMM1 (5′-GTCTAGAGGATCC22GGGCTGTTAAAGCCGGC38-3′) and EcoMM3 (5′-GCTCCCGGGTGAATT C1139GGATTGCCAAGCAATGG1123-3′). The superscript numbers refer to numbers of the ribC sequence in the GenBank database (accession no. Z80835). The oligonucleotides contained heterologous BamHI/EcoRI restriction sites to allow cloning of the 1.143-kbp PCR fragment, using the expression vector pJF119HE, to create pMM01. Plasmid pMM02 was constructed in the same way except that ribC820 was amplified by PCR from chromosomal DNA of B. subtilis RB52.

For gene integration of ribC into the sacB locus of B. subtilis RB52, pMM10 was constructed. ribC was amplified by PCR using oligonucleotides NdeMM2 (5′-76GGTGACCGTCATATGAAGACG96-3′) and EcoMM3 and chromosomal DNA of B. subtilis 1012 as a template. The oligonucleotides contained heterologous NdeI/EcoRI restriction sites to allow cloning of the 1.073-kbp PCR fragment, using pXI12. For integration of ribC820 into the sacB locus of B. subtilis RB52, plasmid pMM11 was constructed in the same way as described above for pMM10 except that ribC820 was amplified by PCR from chromosomal DNA of B. subtilis RB52.

Plasmid pMM20 was constructed for integration of the E. coli flavokinase/FAD-synthetase gene ribF (22, 24) (GenBank database entry M10428) into sacB of B. subtilis 1012. ribF was PCR amplified by using oligonucleotides NdeMM4 (5′-598GTTTTGAGCCACATATGAAGC619-3′) and EcoMM5 (5′-1572CGGTTTGAATTCATAACAGGC1554-3′) and chromosomal DNA of E. coli M15 (41) as a template. The oligonucleotides contained heterologous NdeI/EcoRI restriction sites to allow cloning of the 0.960-kbp PCR fragment by using pXI12 (20).

Plasmid pMM30 was constructed for integration of the FAD-synthetase gene FADI (43) from S. cerevisiae into sacB of B. subtilis 1012. FADI was PCR amplified by using oligonucleotides NdeMM6 (5′-125GGAGCACCATATGCAGCTGAGC146-3′) and EcoMM7 (5′-GGAA1074TTCCTCCGTTAAACCGTA C1056-3′) and chromosomal DNA of a wild-type S. cerevisiae strain as a template. The oligonucleotides contained heterologous NdeI/EcoRI restriction sites to allow cloning of the 0.955-kbp PCR fragment, using pXI12.

The ribC gene was replaced by a neomycin cassette via double-crossover recombination. Adjacent homologous regions to the gene ribC within the ribC locus (147°) of the B. subtilis chromosome were truB (5′) and rpsO (3′). truB was amplified by PCR from B. subtilis 1012 chromosomal DNA, using oligonucleotides XhoMM8 (5′-CCGCTCGAGCTCAAAAGAAGGAGTG-3′) and EcoMM9 (5′-CGGAATTCACAGAACGGTCACC-3′). rpsO was amplified by PCR from B. subtilis 1012 chromosomal DNA with oligonucleotides PstMM10 (5′-ACTGCAGCTTGCAACGCACGC-3′) and SpeMM11 (5′-GGACTAGTCGCAGATACGTAAGAAG-3′). The neomycin cassette was amplified by PCR using plasmid pBEST501 (21) as a template and oligonucleotides EcoMM12 (5′-CGGAATTCGCTTGGGCAGCAGGTCG-3′) and PstMM13 (5′-AACTGCAGTTCAAAATGGTATGCG-3′). The plasmid pMM60 was constructed by ligation of digested PCR fragments of truB, neo, and rpsO (in that order) into XhoI/SpeI-digested pBluescript II SK−.

The integration/expression vector pXI12 (20) was used for the functional introduction of genes into the sacB locus (296°) of B. subtilis.

DNA amplification, cloning, and sequencing.

DNA amplification and cloning were performed according to standard protocols (36). Plasmids pMM01 and pMM02 were proof-sequenced with Taq polymerase (Boehringer). Primary structures were aligned by using MegAlign version 1.05 (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.).

Heterologous expression of ribC.

E. coli BL21 was transformed with pMM01 (ribC wild type) and pMM02 (ribC820), and the resulting strains (BL21MM01 and BL21MM02) were aerobically cultivated at 37°C on LB medium. Gene expression was stimulated by adding 1 mM isopropylthiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) after the culture had reached an optical density at 600 nm of 1.4. After 1 h of further aerobic incubation, cells were harvested by centrifugation.

Purification of overproduced RibC from E. coli.

All procedures were carried out at 0 to 4°C except for the column chromatography steps, which were carried out at room temperature. Frozen cell paste (5 g) of E. coli BL21MM01 and BL21MM02 was resuspended in 25 ml of cold 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM dithiothreitol. Cells were sonicated for 2 min at a power of 80 W in a Branson model 450 sonicator equipped with a 3/4-in. flat tip. All subsequent centrifugation steps were performed at 18,000 × g and 4°C.

Centrifugation for 45 min removed cell debris and unbroken cells. The resulting supernatant was made 40% (wt/vol) in ammonium sulfate, and the precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation. The supernatant was made 70% (wt/vol) in ammonium sulfate and centrifuged, and the deep yellow pellet was resuspended in 10 ml 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). The solution was dialyzed twice for 16 h each time against 5 liters of 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM dithiothreitol. After dialysis, an aliquot (0.2 ml) of this solution was applied to a Mono S HR 5/5 cation-exchange column (Pharmacia) previously equilibrated with 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.5). The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min. The bound protein was washed with 13 ml of this buffer, and elution was carried out by applying 33 ml of a linear gradient from 0 to 400 mM sodium chloride in the same buffer. RibC was eluted from the column at 10 ml (200 mM sodium chloride). Aliquots of the fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250. The apparently homogeneous fractions were tested directly for flavokinase activity and stored at −20°C. The enzyme was stable for at least 2 weeks under these conditions.

Protein determination.

Protein was estimated by the method of Bradford (8), using the Bio-Rad protein assay and bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Protein sequence analysis.

N-terminal sequencing of RibC was done by the method of Hewick et al. (19).

Mass spectroscopy and gel filtration experiments.

Mass spectroscopy of the purified protein was performed as described earlier (42). The molecular masses of the native enzymes (RibC wild type and mutant) were estimated by chromatography on a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 column (Pharmacia) with 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.5)–100 mM NaCl and a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. RibC wild type eluted at 16.015 ml (34.176 kDa), and the RibC mutant eluted at 16.012 ml (34.228 kDa). The standard proteins were RNase A (13.7 kDa) eluted at 17.66 ml, chymotrypsinogen A (25 kDa) eluted at 17.00 ml, ovalbumin (43 kDa) eluted at 15.24 ml, albumin (67 kDa) eluted at 14.19 ml, aldolase (158 kDa) eluted at 13.01 ml, catalase (232 kDa) eluted at 12.92 ml, ferritin (440 kDa) eluted at 11.15 ml, and thyroglobulin (669 kDa) eluted at 9.57 ml.

Enzyme assay, HPLC analysis of flavins, and preparation of cell extracts.

Flavokinase activity was measured in a final volume of 1 ml of potassium phosphate (pH 7.5) containing 50 μM riboflavin, 3 mM ATP, 15 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Na2SO3 (32). The mixture was preincubated at 37°C for 5 min, and the reaction was started by addition of the enzyme. After appropriate time intervals, an aliquot was removed and applied directly to an HPLC column (Nucleosil 10 C18; 4.6 by 250 mm; Macherey & Nagel). The following solvent system was used at a flow rate of 2.5 ml/min: 25% (vol/vol) methanol–100 mM formic acid–100 mM ammonium formate (pH 3.7). Detection was carried out with a fluorescence detector (excitation, 470 nm; emission, 530 nm; Waters Associates, Inc.). Flavokinase activity is expressed as nanomoles of FMN formed from riboflavin and ATP.

Cell extracts of B. subtilis strains were prepared as follows. Cells of an overnight culture (50 ml) were collected by centrifugation, and the cell pellet was washed with 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.5)–1 mM dithiothreitol–0.1 mM EDTA (buffer A). The cells were resuspended in buffer A and sonicated for 5 min. After centrifugation (18,000 × g, 20 min), an aliquot of the supernatant was directly used in the flavokinase assay.

Riboflavin secretion was monitored by HPLC as described above. Overnight cultures were centrifuged, and an aliquot of the supernatant was applied to an HPLC column.

Gene integration into B. subtilis sacB.

Transformation-competent B. subtilis 1012 was transformed with PstI-linearized pMM20 and pMM30 (1 μg of each) by the previously described two-step procedure (13). The erythromycin-resistant transformant B. subtilis strains obtained by homologous double-crossover recombination into the B. subtilis sacB locus (296°) were selected (1012MM002 and 1012MM003). Integration was checked by PCR. B. subtilis RB52 was transformed with PstI-linearized pMM10 and pMM11 (1 μg of each); the resulting strains were RB52MM100 and RB52MM110.

Replacement of B. subtilis ribC by a neomycin cassette via double-crossover recombination.

B. subtilis 1012MM002 was transformed with ScaI-linearized pMM60 (1 μg), and the resulting strain was 1012MM004. B. subtilis 1012MM003 was transformed by using ScaI-linearized pMM60 (1 μg), and the resulting strain was 1012MM006.

RESULTS

Purification and structural characterization of B. subtilis RibC from the wild-type strain 1012 and of the mutant RibC820 from the riboflavin-overproducing strain RB52.

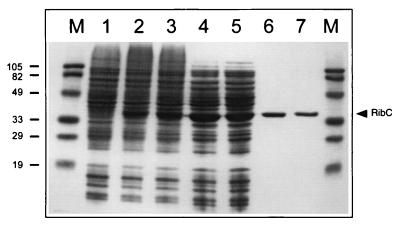

The wild-type ribC and mutant ribC820 genes from B. subtilis were separately overexpressed in E. coli, and the corresponding gene products were purified to apparent homogeneity (Fig. 1). The apparent molecular mass of 36 kDa of wild-type RibC as determined by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1, lane 6) and the molecular mass of 35.668 kDa obtained from mass spectroscopy were in accordance with the molecular mass of 35.665 kDa that was deduced from the 951-bp ribC open reading frame (12). Thus, when overproduced in E. coli, RibC does not contain a covalently bound cofactor. From gel filtration experiments, under nondenaturing conditions, an apparent molecular mass of 34.2 kDa for the wild-type RibC and for the mutant RibC820 was deduced, suggesting a monomeric structure for each protein. N-terminal sequence analysis of pure wild-type RibC revealed a single sequence (MKTIHITHPHL) and confirmed the N terminus that was tentatively deduced from DNA sequence data earlier (12). Thus, ribC starts with the codon GTG, as is true for about 10% of the B. subtilis genes (18).

FIG. 1.

Overproduction and purification of B. subtilis wild-type RibC and mutant RibC820. SDS-PAGE of cell extracts of IPTG-induced E. coli strains harboring the B. subtilis ribC wild-type (E. coli BL21MM01; lane 2) and ribC820 mutant (E. coli BL21MM02; lane 3) genes. As a control, lane 1 shows a cell extract of an IPTG-induced E. coli BL21 strain harboring the expression vector pJF119HE without insert. Lanes 4 and 5 show RibC wild type and mutant, respectively, after (NH4)2SO4 purification. Cation-exchange eluates of RibC wild type and mutant are shown in lanes 6 and 7. Lanes marked M are molecular weight markers (in kilodaltons).

RibC is a flavokinase/FAD-synthetase, and the enzymatic activity of the mutant RibC820 is drastically reduced.

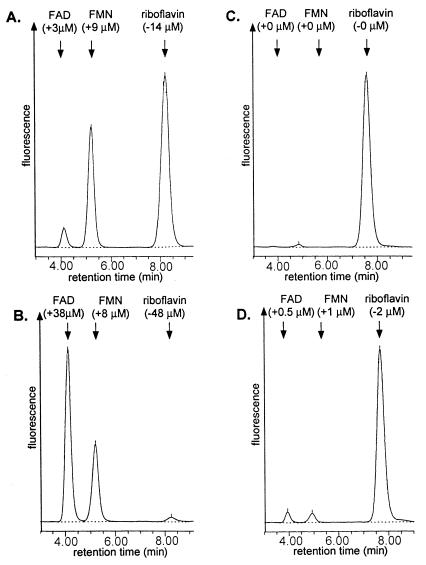

RibC has significant similarities (>30% identity) to bifunctional bacterial flavokinases/FAD-synthetases, suggesting that RibC is the corresponding enzyme in B. subtilis producing the essential coenzymes FMN and FAD (12). The pure wild-type RibC protein showed a specific flavokinase activity of 580 U/mg of protein (Table 2), which is comparable to the specific flavokinase activity (450 U/mg) reported for a flavokinase from Brevibacterium ammoniagenes (28). In addition to FMN, FAD was detected as a second product of the RibC-catalyzed enzymatic reaction (Fig. 2). Thus, RibC is a bifunctional enzyme, as is true for the flavokinases/FAD-synthetases from B. ammoniagenes (28) and E. coli (24).

TABLE 2.

Purification of wild-type RibC and mutant RibC820 from cell extracts of overproducing E. coli strains

| Purification step | Wild-type RibC

|

RibC820

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavokinase activitya | Purification (fold) | Flavokinase activity | Purification (fold) | |

| Cell extract | 70 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| (NH4)2SO4 (40–70% [wt/vol]) purification | 140 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Cation exchange | 580 | 8 | 6 | 6 |

Measured in a final volume of 1 ml of potassium phosphate (pH 7.5) containing 50 μM riboflavin, 3 mM ATP, 15 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Na2SO3 and expressed as nanomoles of FMN produced per minute per milligram of protein. FAD synthetase activity could not be exactly measured because exogenous, highly purified 5′-FMN was not accepted as a substrate.

FIG. 2.

HPLC chromatograms of the products of flavokinase/FAD-synthetase assays. Assay mixtures containing 50 μM riboflavin, 3 mM ATP, 15 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM sodium sulfite (Na2SO3) were preincubated at 37°C for 5 min. Pure wild-type RibC (A and B) or mutant RibC820 (C and D) (3 μg of each) was added, and the mixtures were incubated for another 5 (A and C) or 30 (B and D) min. An aliquot was removed and separated on an HPLC column (Nucleosil 10 C18; 4.6 by 250 mm; Macherey & Nagel). The following solvent system was used at a flow rate of 2.5 ml/min: 25% (vol/vol) methanol–100 mM formic acid–100 mM ammonium formate (pH 3.7). The reaction was monitored with a fluorescence detector (excitation, 470 nm; emission, 530 nm; Waters Associates). The chromatograms show three clearly resolved peaks of riboflavin (8 min), FMN (5 min), and FAD (4 min). Numbers in parentheses indicate decrease of riboflavin and increase of flavin nucleotides during the enzyme assay.

The flavokinase activity of the pure mutant protein RibC820 from the riboflavin-overproducing strain RB52 was reduced to about 1% of the activity of wild-type RibC (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

ribC is essential for growth of B. subtilis.

The ribC820 mutation does not lead to an FMN/FAD auxotrophic B. subtilis strain, although the flavokinase activity of the protein encoded by ribC820 is drastically reduced. This could mean that B. subtilis contains another flavokinase/FAD-synthetase activity complementing the RibC820 defect. Alternatively, the residual activity of RibC820 might be sufficient to meet the FMN/FAD requirements of B. subtilis. Attempts to replace ribC in a B. subtilis wild-type strain (B. subtilis 1012) or in the ribC820 mutant strain (B. subtilis RB52) by a selectable neomycin resistance gene failed, although FMN and FAD were added to the culture medium during the transformation experiments. However, the ribC gene could be removed from the B. subtilis genome after introduction of the E. coli ribF gene encoding a flavokinase/FAD-synthetase. For chromosomal integration of E. coli ribF at the B. subtilis sacB locus and expression of the heterologous gene, the pXI12 expression/integration vector was used. The resulting ribC deletion mutant 1012MM004 had no requirement for FMN or FAD and did not overproduce riboflavin. In summary, transformants devoid of the ribC gene could be obtained only from a parent strain that contained a heterologous flavokinase/FAD-synthetase-encoding gene at sacB. Thus, RibC is essential for the flavin metabolism of B. subtilis. The remaining flavokinase/FAD-synthetase activity of the mutant protein RibC820 within B. subtilis RB52 is sufficient for growth under standard growth conditions.

The ribC gene could also be deleted in a strain that carried the S. cerevisiae FADI gene at the sacB locus. The FADI gene, which was provided with the pXI12 integration/expression system, encodes an FAD-synthetase. The resulting ribC deletion strain 1012MM006 was auxotrophic for FMN, indicating that FMN can be taken up by B. subtilis from the culture medium. No complementation was observed by using exogenous riboflavin. Mutants lacking FAD-synthetase activity could not be rescued by adding FAD to the medium.

Overexpression of wild-type ribC and ribC820 at sacB suppresses the riboflavin overproduction phenotype of the B. subtilis ribC820 strain RB52.

The wild-type ribC gene driven by the medium-strength vegI promoter was introduced at the sacB locus of the riboflavin-overproducing B. subtilis strain RB52, which carries the ribC820 mutation. Again, the pXI12 integration/expression system was used. The flavokinase activity of cell extracts of the resulting strain RB52MM100 was drastically increased (54 U/mg of total cellular protein) compared to the recipient strain RB52 (flavokinase activity below the detection limit) or a wild-type B. subtilis strain (0.21 U/mg of total cellular protein). RB52MM100 did not secrete riboflavin into the culture medium. The wild-type ribC gene at the sacB locus under the control of its original promoter (strain RB52p210) also suppressed riboflavin secretion of RB52 (11).

As in the previous experiment, the mutant ribC820 gene was introduced into the chromosome of RB52. The resulting strain RB52MM110 contained two copies of ribC820, one at the ribC locus and the other at sacB under the control of the vegI promoter. This strain showed flavokinase activity (0.16 U/mg of total cellular protein), which was comparable to the flavokinase activity of a ribC wild-type strain (0.21 U/mg of total cellular protein). RB52MM110 did not secrete riboflavin into the culture medium. The ribC820 gene at sacB under the control of its original promoter (strain RB52p211) did not suppress riboflavin secretion of RB52 (11). In conclusion, wild-type ribC is dominant over mutant ribC820, preventing deregulation of riboflavin biosynthesis in ribC820 mutants. Overexpression of the mutant gene ribC820 can restore the wild-type phenotype as well. These results suggest a negative regulatory role of RibC in riboflavin biosynthesis.

FMN or FAD but not riboflavin is an effector molecule regulating riboflavin biosynthesis in B. subtilis.

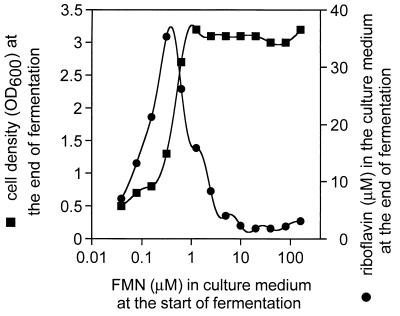

The ribC deletion mutant 1012MM004, which contains the ribF-encoded flavokinase/FAD-synthetase from E. coli (see above), did not overproduce riboflavin. This was also true for the FMN auxotrophic ribC deletion mutant 1012MM006 carrying the S. cerevisiae FAD1 gene (see above) when cultivated with 10 μM FMN. Upon cultivation with 0.1 to 1 μM FMN in the culture medium, however, significant amounts of riboflavin (>10 μM) were secreted (Fig. 3). The low FMN concentrations in the culture medium allowed only suboptimal growth of the bacteria, most likely due to FMN shortage or FMN depletion in the cells. These results indicate that repression of riboflavin overproduction occurs in the absence of B. subtilis RibC. The critical parameter determining the rate of riboflavin biosynthesis seemingly is the intracellular FMN or FAD concentration.

FIG. 3.

FMN-dependent riboflavin overproduction in B. subtilis 1012MM006. The FMN auxothropic ribC deletion mutant B. subtilis 1012MM006 was cultivated for 16 h in the presence of the indicated amounts of FMN. Riboflavin in the culture medium at the end of fermentation was determined by HPLC analysis as described for Fig. 2. Cell optical density at 600 nm (OD600) at the end of fermentation was estimated photometrically.

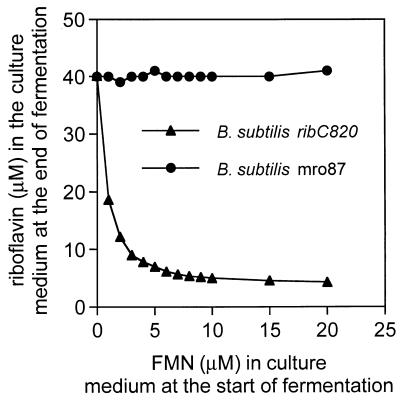

Since the flavokinase/FAD-synthetase of the B. subtilis ribC820 mutant strain has a drastically reduced enzymatic activity, the intracellular flavin nucleotide levels should be lower in the mutant strain than in a B. subtilis wild-type strain. The low nucleotide levels might be the reason for the riboflavin overexpression phenotype of ribC820. Consequently, addition of FMN to the culture medium should prevent riboflavin overproduction and secretion. In fact, in the presence of >10 μM FMN, almost complete repression of riboflavin secretion from B. subtilis ribC820 was observed (Fig. 4). FMN did not prevent riboflavin secretion from a B. subtilis ribO mutant (1012mro87) with a deregulating cis-acting mutation in the rib leader sequence (Fig. 4). Addition of 10 μM riboflavin had no repressive effect on riboflavin secretion.

FIG. 4.

Exogenuous FMN represses riboflavin overproduction in a B. subtilis ribC820 (triangles) but not in a B. subtilis 1012mro87 (ribO mutant, circles) strain. A B. subtilis ribC820 strain and strain 1012mro87 (ribO mutant) were cultivated for 16 h in growth medium supplemented with indicated amounts of FMN. Riboflavin in the supernatant was determined by HPLC as described for Fig. 2. Cell growth was estimated photometrically at 600 nm.

These results indicate that FMN and/or FAD, but not riboflavin, act as effector molecules for regulation of riboflavin biosynthesis. With the data presented here, it cannot be distinguished whether both FMN and FAD or only one of the two flavin nucleotides has an effector function. The riboflavin overproduction phenotype of B. subtilis ribC820 can be explained by the reduced flavokinase/FAD-synthetase activity encoded by the mutant ribC820 gene, which prevents accumulation of inhibitory FMN and/or FAD levels.

DISCUSSION

B. subtilis strains carrying mutations in the ribC gene overproduce riboflavin and secrete the vitamin into the culture medium. Deregulation of riboflavin biosynthesis in these mutant strains was assigned previously to a defect in a putative RibC apo-repressor protein (26). The wild-type RibC protein was thought to negatively regulate riboflavin biosynthesis in combination with riboflavin, FMN, and FAD, which should act as corepressors (9). Cloning and sequencing of the ribC gene, however, revealed that the primary structure was similar to that of a number of genes encoding bifunctional bacterial flavokinases/FAD-synthetases (12, 17). In the present work, it is directly shown that RibC has flavokinase/FAD-synthetase activity. Furthermore, it is shown that RibC plays an essential role in the flavin metabolism of B. subtilis: a ribC deletion mutant is not viable unless a heterologous bifunctional flavokinase/FAD-synthetase gene (e.g., E. coli ribF) or a heterologous FAD-synthetase gene (e.g., S. cerevisiae FADI) in combination with exogenous FMN is present. Since the FMN but not the FAD requirements of B. subtilis ribC deletion mutants could be met by exogenous supply, it is reasonable to assume that FMN but not FAD can be imported by B. subtilis.

After having established the function of RibC in flavin metabolism, we investigated a possible direct regulatory role of the protein in riboflavin biosynthesis. A dual role of a protein in coenzyme metabolism and gene regulation would not be without precedence: the birA gene products of both E. coli (14) and B. subtilis (7) catalyze the transfer of biotin to the biotin carboxyl carrier protein, generating the physiologically active form of biotin. Together with biotin as a corepressor, E. coli BirA also acts as a repressor of the biotin biosynthesis genes (6).

A corresponding function in flavin metabolism and rib gene regulation was envisaged for RibC. However, the data presented here show that riboflavin biosynthesis in two B. subtilis mutants lacking the ribC gene is not deregulated, which excludes a direct repressive function of RibC in the regulation of the rib operon, e.g., by physical interaction with the rib operator. This conclusion is based on the very likely assumption that the unrelated S. cerevisiae FADI gene product does not have such a hypothetical direct repressive function on riboflavin biosynthesis in the B. subtilis mutant 1012MM006. It seems also very unlikely that ribF from E. coli, in which riboflavin biosynthesis is constitutive (4), should have a direct repressive function on riboflavin biosynthesis in the B. subtilis mutant 1012MM004.

Riboflavin overproduction by the FMN auxotrophic ribC deletion mutant 1012MM006 is affected by the FMN concentration but not by the riboflavin concentration in the culture broth, suggesting that FMN and/or FAD, but not riboflavin, have an effector role in regulation of riboflavin biosynthesis. This conclusion is supported by the observation, that riboflavin secretion in the ribC820 mutant strain RB52 is repressed by exogenous FMN but not by riboflavin. It is conceivable that the intracellular FMN or FAD concentration in the mutant ribC820 strain is lower than that in wild-type cells, due to the drastically reduced flavokinase/FAD-synthetase activity of the ribC820 gene product. The low flavin nucleotide concentration is sufficient for bacterial growth but does not exceed the threshold level inducing repression of riboflavin biosynthesis. As a result, riboflavin, which has no activity as a coenzyme and no corepressor function, is overproduced in the ribC820 mutant strain.

Recently, a mutation designated ribR was mapped at 236° of the B. subtilis genome. This mutation was reported to suppress riboflavin secretion of ribC mutant strains. It was suggested that the hypothetical gene product of the affected ribR gene together with RibC forms a putative multimeric rib repressor protein (26). The N terminus (110 amino acids) of RibR (16) shows significant sequence similarity (50% identity) to the C terminus of RibC and other bifunctional bacterial flavokinases/FAD-synthetases (27). Kitatsuji et al. (24) reported that the flavokinase activity of the E. coli flavokinase/FAD-synthetase was associated with the C terminus. Thus, ribR might encode a flavokinase-like protein. According to our present work, RibC is seemingly the only flavokinase/FAD-synthetase present in vegetative B. subtilis wild-type strains cultivated under the usual laboratory conditions. To explain why ribR acts as a suppressor mutation in ribC mutants, one could hypothesize that the ribR mutation activates the dormant flavokinase activity of the ribR gene product or allows ribR expression in vegetative B. subtilis cells. This could lead to an increase in the intracellular FMN or FAD concentration of ribC mutants and suppression of the riboflavin overproduction phenotype.

All riboflavin-overproducing B. subtilis strains isolated so far either carry a lesion in the flavokinase/FAD-synthetase-encoding ribC gene or have mutations within the cis-acting ribO leader region of the rib operon. This could mean that the selection and screening methods applied were not suited for isolation of other than these two types of deregulated mutants. Attempts to isolate new types of deregulated mutants and to identify additional components of the riboflavin regulatory system are ongoing. The lack of deregulated mutants with a lesion in a putative repressor protein could also mean that such a repressor protein does not exist and that the flavin nucleotides would negatively affect riboflavin biosynthesis in the absence of a trans-acting protein.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arbige M V, Bulthuis B A, Schultz J, Crabb D. Fermentation of Bacillus. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J A, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 871–895. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacher A. Biosynthesis of flavins. In: Müller F, editor. Chemistry and biochemistry of flavoenzymes. Vol. 1. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 215–259. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bacher A. Riboflavin kinase and FAD synthetase. In: Müller F, editor. Chemistry and biochemistry of flavoenzymes. Vol. 1. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 349–370. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bacher A, Eberhardt S, Richter G. Biosynthesis of riboflavin. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 657–664. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bacher A, Eisenreich K, Kis K, Ladenstein R, Richter G, Scheuring J, Weinkauf S. Biosynthesis of flavins. In: Dugas H, Schmidtchen F P, editors. Bioorganic chemistry frontiers. Vol. 3. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1993. pp. 147–192. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker D F, Campbell A M. The birA gene of Escherichia coli encodes a biotin holoenzyme synthetase. J Mol Biol. 1981;146:451–467. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bower S, Perkins J, Yocum R R, Serror P, Sorokin A, Rahaim P, Howitt C L, Prasad N, Ehrlich S D, Pero J. Cloning and characterization of the Bacillus subtilis birA gene encoding a repressor of the biotin operon. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2572–2575. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2572-2575.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bresler S E, Glazunov E A, Chernik T P, Schevchenko T N, Perumov D A. Investigation of the operon of riboflavin biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. V. Flavin mononucleotide and flavin-adenine dinucleotide as effectors in the riboflavin biosynthesis operon. Genetika. 1975;9:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bullock W O, Fernandez J M, Short J M. XL1-Blue: a high efficiency plasmid transforming recA Escherichia coli strain with beta-galactosidase selection. BioTechniques. 1987;5:376–379. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coquard D. Diploma thesis. Illkirch, France: Ecole Superieure de Biotechnologie de Strasbourg; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coquard D, Huecas M, Ott M, van Dijl J M, van Loon A P G M, Hohmann H-P. Molecular cloning and characterisation of the ribC gene from Bacillus subtilis: a point mutation in ribC results in riboflavin overproduction. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;254:81–84. doi: 10.1007/s004380050393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutting S M, Vander Horn P B. Genetic Analysis. In: Harwood C R, Cutting S M, editors. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus, modern microbiological methods. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 27–74. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenberg M A, Prakash O, Hisiung S-C. Purification and properties of the biotin repressor—a bifunctional protein. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:15167–15173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fürste J P, Pansegrau W, Frank R, Blöcker H, Scholz P, Bagdasarian M, Lanka E. Molecular cloning of the plasmid RP4 primase region in a multi-host-range tacP expression vector. Gene. 1986;48:119–131. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gusarov, I. 1996. GenBank database entry Y09721.

- 17.Gusarov, I. V., Y. I. Yomantas, Y. I. Kozlov, R. A. Kreneva, and D. A. Perumov. 1996. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of regulator gene of the Bacillus subtilis riboflavin operon. EMBL databank entry X95312.

- 18.Hager P W, Rabinowitz J C. Translational specificity in B. subtilis. In: Dubneau D, editor. The molecular biology of the Bacilli. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1985. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hewick R M, Hunkapillar M W, Hood L E, Dreyer W J. A gas-liquid solid phase peptide and protein sequenator. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:7990–7997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hümbelin, M., V. Griesser, T. Keller, W. Schurter, H. P. Hohmann, and A. P. G. M. van Loon. Unpublished results.

- 21.Itaya M, Konda K, Tanaka T. A neomycin resistance gene cassette selectable in a single copy state in the Bacillus subtilis chromosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:4410. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.11.4410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamio Y, Lin C K, Regue M, Wu H C. Characterisation of the ileS-lsp operon in Escherichia coli. Identification of an open reading frame upstream of the ileS gene and potential promoter(s) for the ileS-lsp operon. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:5616–5620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kil Y V, Mironov V N, Gorishin I Y, Kreneva R A, Perumov D A. Riboflavin operon of Bacillus subtilis—unusual symmetric arrangement of the regulatory region. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;233:483–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00265448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitatsuji, K., S. Ishino, S. Teshiba, and M. Arimoto. 1993. Process for producing flavine nucleotides. European patent application 0 542 240 A2.

- 25.Kreneva R A, Perumov D A. Genetic mapping of regulatory mutations of Bacillus subtilis riboflavin operon. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;222:467–469. doi: 10.1007/BF00633858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreneva R A, Perumov D A. Genetic mapping of an additional regulatory locus of the riboflavin operon of Bacillus subtilis. Genetika. 1996;32:1623–1628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mack, M. 1997. Unpublished results.

- 28.Manstein D J, Pai E F. Purification and characterization of FAD synthetase from Brevibacterium ammoniagenes. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:16169–16173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mironov V N, Chikindas M L, Krayev A S, Stepanov A I, Skryabin K G. Operon organization of riboflavin biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR. 1990;312:237–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mironov V N, Krayev A S, Chernov B K, Stepanov A I, Skryabin K G. Complete nucleotide sequence of riboflavin biosynthesis operon from Bacillus subtilis. Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR. 1989;305:482–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mironov V N, Perumov D A, Kraev A S, Stepanov A I, Skryabin K G. Unusual structure of Bacillus subtilis rib-operon regulatory region. Mol Biol (Moscow) 1990;24:256–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nielsen P, Rauschenbach P, Bacher A. Phosphates of riboflavin and riboflavin analogs: a reinvestigation by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1983;130:359–368. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90600-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perkins J B, Pero J G. Biosynthesis of riboflavin, biotin, folic acid, and cobalamin. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J A, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 319–334. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perkins, J. B., J. G. Pero, and A. Sloma. 1990. Riboflavin overproducing strains of bacteria. European patent application 0 405 370 A1.

- 35.Saito H, Shibaat T, Ando T. Mapping of genes determining nonpermissiveness and host specific restriction to bacteriophages in B. subtilis Marburg. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;170:117–122. doi: 10.1007/BF00337785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T E. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiio I. Production of primary metabolites. In: Maruo B, Yoshikawa H, editors. Bacillus subtilis: molecular biology and industrial application. Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha Ltd. and Elsevier Science Publishers; 1989. pp. 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spizizen J. Transformation of biochemically deficient strains of Bacillus subtilis by deoxyribonucleate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1958;44:1072–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.10.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stepanov, A. I., V. G. Zdanov, A. J. Kukanova, M. J. Chaikinson, P. M. Rabinovic, J. A. V. Iomantas, and Z. M. Galuskina. 1983. Verfahren zur Herstellung von Riboflavin. Offenlegungsschrift DE 3420310/A1.

- 40.Studier F W, Moffatt B A. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. Mol Biol. 1986;189:113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villarejo M R, Zabin I. Beta-galactosidase from termination and deletion mutant strains. J Bacteriol. 1974;120:466–474. doi: 10.1128/jb.120.1.466-474.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilm M, Mann M. Analytical properties of the nanoelectrospray ion source. Anal Chem. 1996;68:1–8. doi: 10.1021/ac9509519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu M, Repetto B, Glerum D M, Tzagoloff A. Cloning and characterization of FAD1, the structural gene for flavin adenine dinucleotide synthetase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:264–271. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]