INTRODUCTION

Representing the vast majority of urologists practicing in Canada, the Canadian Urological Association (CUA) has a mandate to be the “Voice of Urology in Canada,” by addressing challenges affecting its membership, including workforce and resource needs. As we exited the pandemic, healthcare within Canada was forced to take stock of the unmet clinical care needs and assign priorities to address those demands.

In order to best assist our members and their patients as we faced the post-pandemic new world order, CUA leadership felt it important to obtain the most updated information on the current state of urology in Canada. To that end, a census was developed and circulated to the CUA membership. The intention was to collect data on membership demographics and practice patterns, as well as to better understand workforce and resource challenges across the country. Moreover, it was hoped that the information obtained could be used by the CUA in its advocacy efforts with licensing, accrediting bodies, and policymakers. As the topic of healthcare reform gains increasing attention, the ability of the CUA to lobby effectively requires up-to-date information to highlight our specialty’s challenges and support meaningful solutions. Demographic surveys of the CUA membership had previously been conducted in 2011 and 2018, focusing primarily on workforce issues. It was felt a more comprehensive sampling was needed to better understand contemporary demographics and practice patterns.

Herein, we present a description of the census development process, the observed findings, and the CUA’s plans to explore the results.

METHODS

A request for proposal (RFP) process was initiated in January 2022 by the CUA in order to identify a Canadian media organization capable of partnering with us to fulfill the requirements of the proposed survey. After completion of the RFP, Leger,* the largest Canadian-owned market research and analytics company in the country, was selected. Following several meetings to clarify the CUA’s goals and objectives, an online survey was developed with Leger’s market research team. It was emphasized that in addition to obtaining information on the current state of urology in Canada, the long-term intention was to collect longitudinal data over time in order to identify trends and monitor the impact of the administration of health policy changes. Forty-four questions were developed in an attempt to capture this information. The questionnaire was designed to be completed within 15 minutes. The full survey is included in an Appendix (available at cuaj.ca).

The specific objectives of the census survey included the collection of data on members’ demographics, including geographic practice location and education. Collection of information on CUA members’ practice patterns, access to resources, including new technology, and also workforce issues, including hiring and retirement planning, were also requested.

The CUA has eight categories of membership. The survey was sent by email to members in the active and senior (but still practicing) categories whose mailing address was in Canada. Two additional reminder emails were also sent. The survey was not offered to members practicing outside Canada, non-urologist associate members, honorary members, senior and retired urologists, or those in training. The census survey was offered in both English and French. Members who had not responded to the online survey and were in attendance at the 2022 CUA annual meeting in Charlottetown, PEI, had the opportunity to complete the survey using computers provided at the meeting. At the time the survey was conducted, there were 676 active and senior members (still practicing).

Data was captured such that regional comparisons would be possible. To ensure reasonable sample sizes, data from respondents from Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland and Labrador were combined into a group labeled Atlantic Canada. Similarly, responses from members in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba were included as representing the Prairie Provinces.

The census was open from May 26 to August 3, 2022. As an incentive to participate, at the 2022 annual meeting, a rebate of $50.00 on the annual membership dues was offered.

The statistical data obtained was rounded such that not all domains totaled 100%. Weighting was applied based on the CUA membership by province in order to render a representative sample from all regions. No other demographic domains were used to weight the sample.

RESULTS

Demographics

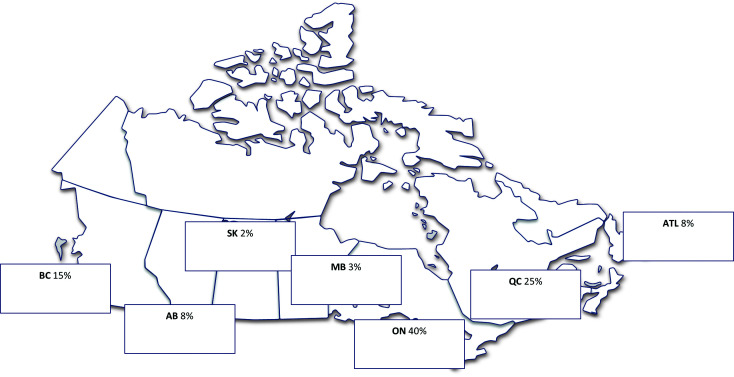

From a potential pool of 676 active and senior (practicing) members, 261 completed the survey, for a response rate of 39%. The gender distribution of participants was 81% male and 17% female, with 2% not providing a response to the question. The average age was 48, with 9% under age 35, 35% between 35 and 44, 28% between 45 and 54, and 28% over 55 years old. For 74% of members, English was the primary language used in their practice. French was primarily spoken in 20% of practices, with both languages used in 6%. With respect to the type of practice, 38% of participants identified themselves as community urologists, 36% as academic, and 26% as working in a hybrid model. Census responses by region are shown in Figure 1. Among respondents, 91% indicated they worked full-time, while 9% reported they worked on a part-time basis.

Figure 1.

Respondent profile by region.

Among survey participants, 91% completed medical school training in Canada. For international medical graduates, countries where training occurred included (in alphabetical order): Colombia, Egypt, France, Germany, India, Iran, Ireland, Italy, Lebanon, Libya, Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and Syria. Residency training was completed after 2001 by 69% of respondents, 18% in the 1990s and by 13% between 1970 and 1989. Seventy-two per cent of members completed at least one year of fellowship training after residency. The motivation for pursuing a fellowship included academic interest (75%), as a necessity to securing a practice position (47%), and because there were no other options for work at the time of residency completion (10%); 6% of respondents did not specify a reason. Of note, some participants provided more than one reason. Subspecialty fellowship training areas, including a breakdown by current region of practice, are shown in Figure 2. Overall, of those who completed a fellowship, 73% reported most of their practice was focused on their subspecialty. For those working in an academic setting, 92% were practicing in their subspecialty, with 51% of community practitioners and 62% of those who work in a hybrid model also able to do so.

Figure 2.

Types of fellowship training programs and by region. Other included: functional, female, and neuro-urology. MIS: minimally invasive surgery.

Among the cohort, the average number of years in practice was 15. Forty-seven percent identified general urology as their primary clinical focus, with the remainder practicing in a subspecialty area. Areas of clinical practice focus are listed in Figure 3. Among those who reported working in a community setting, 77% indicated general urology was their main area of focus, while 67% of those working in hybrid model and only 7% of academic urologists had a general focus. Among community members, solo practitioners were more likely to describe their practice as having a general focus (67%) vs. those who participated in a group practice (38%).

Figure 3.

Primary clinical practice focus. MIS: minimally invasive surgery.

Practice patterns

On average, respondents reported 65 in-person patient office or clinic visits per week. Urologists with a general practice focus and those working in Quebec reported higher in-person patient visits. Among the entire cohort, 23% of members reported seeing more than 100 patients in-person each week. The average time participants spent on a new patient consult was 17 minutes. The average number of days spent seeing patients in the office or clinic setting was three, with 50% spending two days or less. Seventy-five percent of participants reported receiving in-hospital clinic time, with an average of 14 hours/week being provided. Members in Quebec reported the largest number of hours, with a mean of 27 hours/week, and those in British Columbia received the least, with eight hours/week of hospital clinic time provided.

During a typical week, the average time spent on clinical activities was 46 hours, although for 40% of members, clinical work exceeded 50 hours/week. The mean hours per week did not differ between those who identified themselves as working in a general urology practice compared to those with a subspecialty focus. Among the regions of the country, those respondents from Quebec reported fewer mean hours/week in clinical activity (34), and those in the prairies reported the highest (52).

The mean time spent performing cystoscopy in a typical week was five hours, with 39% reporting more than seven hours devoted to this activity. Survey participants reported an average of four operating room (OR) days/month (excluding cystoscopy time). Twenty-five percent of members reported having more than six OR days in a typical month. Members in Atlantic Canada reported fewer mean OR days (three), and those in British Columbia reported more than (five) than those in the rest of the country.

Those surveyed reported a night call volume of six days per month, on average, although 12% were on call more than 11 days/month. While on-call, the average number of hospitals covered was three, with 28% covering four or more hospitals. Those in Atlantic Canada covered more hospitals on average (four) than those in other regions, especially Ontario and Quebec, where the average was two hospitals.

Two-thirds of CUA members surveyed work in a group practice. Those in community settings were more likely to work in a solo practice, whereas those in academic or hybrid arrangements more commonly were part of a group practice. Overall, group practices were less common in Ontario (50%) and most common in Quebec (83%). Among those working in a group practice, 79% reported 10 urologists or fewer were part of their group.

Participants were asked whether their practices were currently hiring or expecting to hire additional urologists within the next five years. Sixty-eight percent indicated hiring was ongoing or planned during this time frame. Members working in subspecialty academic and hybrid practices reported an 80% likelihood of recruitment vs. 56% for those in general practices. Among the various regions, recruitment was most likely in British Columbia, the Prairies, and Quebec. Among those expecting to recruit new urologists to their practices within the next year, 51% were seeking individuals with oncology specialty training. The complete listing of the desired specialty training required for general and specialty practices highlighted by region is displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Desired subspecialty training for those recruiting within the next year, by practice type (general vs. academic) and region. MIS: minimally invasive surgery.

Among those practitioners currently or planning to hire, 17% of respondents reported recruitment difficulties. Reasons cited included an inability to find a suitable recruit, lack of interest among recruits in the practice location, lack of adequate hospital resources, and failure of cooperation with hospital administration. Participants practicing in Quebec and the Prairie provinces reported higher rates of difficulty than other regions.

Access to equipment and specialized resources was surveyed. The percentage of members with access to the various technologies and the regional variations are displayed in Figure 5. There were some notable differences among the geographic areas. Multi-channel urodynamics was available to 61% of those practicing in Ontario compared to 81–91% of those practicing elsewhere in Canada. Shockwave lithotripsy was only available to 56% and 59% of respondents from Ontario and Quebec, respectively, vs. 71% from British Columbia, 90% from Atlantic Canada, and 93% from the Prairies. In BC and Atlantic Canada, only 35% of members had access to robotic surgery compared to 49% in Ontario, 58% in Quebec, and 60% in the Prairie provinces. Genomic testing or biomarker assessment was most readily available in Ontario (50% of respondents). Focal therapy options for treating prostate cancer were more available in the Prairies.

Figure 5.

Percentage of respondents with access to specialized services, including by region. MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; RFA: radiofrequency ablation.

Several questions were asked about the use of telemedicine, social media, and electronic medical records (EMR) in members’ practices. Survey participants were asked if they planned to continue using telemedicine post-pandemic and 84% indicated their intention to do so. Only 16% used their own website to share information with patients and only 4% used a social media account for this purpose. Practitioners in the Prairies were more likely (32%) to use social media in their practices. Barriers to incorporating social media that were mentioned by respondents included unclear advantage, a lack of time to set up and manage, and privacy concerns. Ninety-one percent of members used an EMR, although this was less commonly employed in Atlantic Canada, where only 68% reported access.

Survey participants were asked at what age they are considering retirement. The mean age mentioned was 64 years, although 32% were unsure. There were no significant differences observed for community vs. academic respondents or between regions. Financial situation was mentioned as the main factor that might delay their decision. All factors mentioned that would influence their decision on retirement are shown in Figure 6. When asked if they were planning to retire in the next year, 15% indicated this intention. Among this subgroup, 6% were planning to completely retire from clinical practice and 9% intended to work part-time. Among all survey participants, 48% felt the specialty of urology lends itself to a part-time practice, although this belief varied by region. In Atlantic Canada, only 28% of urologists surveyed indicated a part-time practice was feasible, while in Quebec, 68% believed it did.

Figure 6.

Factors mentioned by respondents that might influence their decision to retire. HCP: healthcare professional.

Respondents were asked to describe their non-clinical activities in a typical week and the time devoted to this work. Responses are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Time spent on non-clinical activities in a typical week.

For the preceding year, participants were asked to report the number of weeks of vacation they took. The mean number of weeks was five, with 21% taking fewer than three weeks and 39% taking more than six weeks of vacation.

DISCUSSION

A census is an official count or survey of a population typically taken at regular intervals.1,2 While the intention of a government-mandated census is to attempt capture data on every member of a population, medical organizations must usually rely on sampling of a smaller group of individuals to represent the membership. Sampling a population requires less expense than an in-depth census, and yet can still provide meaningful information on the entire population of interest. Sampling can be used to identify trends from large datasets as well. In order to gauge how representative a sampling is of a population as a whole, the survey response rate is an important metric. When sampling, margin of error or confidence interval is an estimate of how survey participants’ responses reflect those of the entire population. The smaller the margin of error the more confidence one can have in the survey findings.

In this CUA survey, 261 of 676 (39% of eligible members) participated. Using a standard 95% confidence level, a margin of error of 5% was calculated.3 A sampling rate of 39% is generally considered a reasonable response to an online survey. In two recent meta-analyses of online surveys, the average response rates were 36–41.1%.4,5

The CUA survey was sent to a clearly defined subset of members — those in active practice. As our intention was to collect demographic data and understand practice patterns on those in practice in Canada, trainees, non-urologist members, and those working outside the country were not included. Targeting a subset of the membership may also allow the creation of a shorter, more focused questionnaire and may improve participation. In Wu et al’s meta-analysis of survey responses, having a clearly defined population of interest, as well as employing reminders, helped increase participation. Pre-contacting participants and using methods other than online platforms also enhanced response rates, while use of incentives does not appear to impart much added benefit.

The information obtained from this in-depth survey of the CUA membership can be used by the organization and its committees in a number of ways. The demographic data will be important to monitor by the Membership Services and Office of Education teams to ensure needs are being adequately met, and to aid in the development of new programs as age, gender, and regional variations undoubtedly occur over time. Workforce needs and resource access challenges are topics of importance to the Health Policy and the newly created Advocacy Committees; the data collected can be shared with policymakers to bring forward, in concrete terms, the issues facing Canadian urologists and their patients. As regional differences have been noted in the survey, this information can potentially be leveraged in provincial dialogue. Future surveys will also be invaluable in tracking the impact of changes on urological care as a result of changes in healthcare delivery and general population demographic shifts.

Limitations

While this survey provides a wealth of information about urologists and their practices in Canada, with a relatively low margin of error, there are limitations that must be acknowledged. Census surveys rely on individuals self-reporting and, therefore, the responses cannot be validated and are potentially subject to bias. While a response rate of 39% for a membership survey is considered reasonable and with a relatively low margin of error, it is possible the results of the survey do not reflect the majority of CUA members who did not participate. Moreover, although the vast majority of practicing urologist in Canada are members of the CUA, non-members’ data is not captured in these results either. Some regions of the country have a relatively small number of CUA members, and the small sample size of survey respondents in those areas might be especially susceptible to observational misrepresentation.

CONCLUSIONS

The 2022 CUA active membership survey has provided an invaluable snapshot on the state of urology in Canada. The information collected and analyzed will be helpful to the CUA Board of Directors and corporate office in the provision of services to members. For the newly created Advocacy Committee, the data obtained will assist in the development of the office’s short-term work plan, and will be particularly beneficial as we begin engagement with provincial licensing bodies, educational providers, and policymakers. Future surveys will allow refinement of the questions and the collection of longitudinal data that may help to identify important demographic shifts or clinical practice trends.

The CUA is grateful to all members who participated and who shared their experiences.

Supplementary Information

Footnotes

Leger, 507 Place d’Armes, Suite 700, Montreal, QC, H2Y 2W8; https//leger360.com/

Appendix available at cuaj.ca

COMPETING INTERESTS: The authors do not report any competing personal or financial interests related to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bell Kenton., editor. Census. Open Education Sociology Dictionary. 2015. https://sociologydictionary.org/census/

- 2.Statcan.gc.ca

- 3. surveymonkey.com

- 4.Daikeler J, Silber H, Bosnjak M. A meta-analysis of how country-level factors affect web survey response rates. Int J Market Res . 2021;64:306–33. doi: 10.1177/14707853211050916. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu M-J, Zhao K, Fils-Aime F. Response rates of online surveys in published research: A meta-analysis. Comp Hum Behav Rep. 2022:7. doi: 10.1016/j.chbr.2022.100206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.