Abstract

Introduction

Acute mechanical thrombectomy (MT) is the preferred treatment for large vessel occlusion-related stroke. Histopathological research on the obtained occlusive embolic thrombus may provide information regarding the aetiology and pathology of the lesion to predict prognosis and propose possible future acute ischaemic stroke therapy.

Methods

A total of 75 consecutive patients who presented to the Amphia Hospital with acute large vessel occlusion-related stroke and underwent MT were included in the study. The obtained thrombus materials were subjected to standard histopathological examination. Based on histological criteria, they were considered fresh (<1 day old) or old (>1 day old). Patients were followed for 2 years for documentation of all-cause mortality.

Results

Thrombi were classified as fresh in 40 patients (53%) and as older in 35 patients (47%). Univariate Cox regression analysis showed that thrombus age, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale at hospital admission, and patient age were associated with long-term mortality (p < 0.1). Multivariable Cox hazards and Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that after extensive adjustment for clinical and procedural variables, thrombus age persisted in being independently associated with higher long-term mortality (hazard ratio: 3.34; p = 0.038, log-rank p = 0.013).

Conclusion

In this study, older thromboemboli are responsible for almost half of acute large ischaemic strokes. Moreover, the presence of an old thrombus is an independent predictor of mortality in acute large vessel occlusion-related stroke. More research is warranted regarding future therapies based on thrombus composition.

Keywords: Stroke, Thrombectomy, Thrombus, Prognosis

Introduction

Stroke is an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In the USA, around 700,000 people suffered from an ischaemic stroke in 2022. Of these, around 140,000 are related to large vessel occlusions suitable for mechanical thrombectomy (MT) [1]. The introduction of MT for acute ischaemic stroke has led to enhancements in both overall survival and quality of life [2]. Therefore, it has been recognized as a class IA recommended treatment for acute large vessel occlusion stroke (LVOS) in the anterior circulation since 2018 [3].

The obtained thrombectomy material enables research regarding the pathophysiology of acute ischaemic stroke. An earlier study demonstrated that thrombus composition may have an impact on MT, the number of recanalization manoeuvres, resistance to retrieval, and thrombolytic potential [4]. Earlier studies on thrombi obtained from ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients demonstrated an association of thrombus age with adverse outcomes [5, 6]. Based on this correlation, we hypothesized that thrombus age might have a similar impact on LVOS as well. The aim of the present study was to establish the relation between thrombus age and outcome in patients who presented with acute large vessel occlusion-related ischaemic stroke and were treated with MT.

Methods

Patient Population

A total of 75 consecutive patients who presented at the Amphia Hospital between January 1, 2016, and December 1, 2017, with acute LVOS and who underwent MT were included in the study. All patients treated with MT at our institution are prospectively followed for clinical outcomes. Patients and procedural data are entered into a local database. Thrombus aspiration and histopathological evaluation of thrombi are part of routine clinical practice. Therefore, in this study, informed consent was not required under the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act. A formal waiver was obtained through our Local Medical Ethical Committee. The study conforms with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

MT Procedure

All patients were treated according to contemporary stroke guidelines [3]. After haemorrhagic stroke was excluded by an unenhanced computed tomography (CT), recombinant tissue plasmin activator (rTPA) was administrated intravenously within 4.5 h after symptom onset. Patients who presented after this time window, patients who were on anticoagulation therapy with an international normalized ratio >1.7 at hospital admission, or patients who recently underwent surgery (less than 6 weeks) did not receive rTPA. After CT, a head and neck CT angiography, including multiphase CT angiography, was performed [7]. In case of an LVOS (internal carotid artery terminus, middle [M1/M2] cerebral artery, or anterior [A1/A2] cerebral or basilar artery), patients were referred for emergency MT. No upper age limit was applied. The MT procedure was performed via an 8-Fr femoral sheath. An 8-Fr balloon catheter (FlowGate, Stryker, Kalamazoo, USA) was positioned in the internal carotid artery (ICA). When a severe ICA stenosis was present, balloon dilatation was performed first. In most cases, a stent retriever (Trevo, Stryker, Kalamazoo, USA, size 4 millimetre [mm] or 6 mm) alone was used. Additional passage with the Penumbra catheter system (Penumbra, Alameda, USA) was performed when flow restoration after stent retriever treatment was suboptimal. Suboptimal was defined as a thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (TICI) grading score of less than TICI 2B [8].

Histology

Aspirated thrombus materials were directly fixed in 10% formalin and further processed for paraffin embedding. As a standard procedure, all aspirated materials were investigated for thrombus composition and age, inflammation plaque constituents, and other features of potential diagnostic relevance. A standard haematoxylin-eosin (HE) stain (5 μm thick sections) was applied on two sections of each case and used for analysis. Thrombus age was graded as described in earlier studies in two categories: fresh thrombus (less than 1 day old): completely composed of layered patterns of platelets, fibrin, erythrocytes, and intact granulocytes. Old thrombus (>1 day old): areas of colliquation necrosis and karyorrhexis of granulocytes (lytic changes) or organized thrombus: areas of ingrowth of myofibroblasts, with or without depositions of young connective tissue and/or ingrowth of capillary vessels [5, 6, 9]. Two experienced pathologists independently performed the histopathologic analysis determining thrombus age. Figure 1 shows an example of the histopathological appearance of fresh thrombus. Figure 2 shows the histopathological appearance of older thrombus. In case of doubt, additional immunohistochemical stains were applied with monoclonal antibodies reactive with endothelial cells (CD34 antibody) and myofibroblasts/smooth muscle cells (SMA-1 antibody) to verify the presence of older thrombus constituents. Thrombus material with a heterogeneous composition in terms of age was graded according to the age of the oldest part.

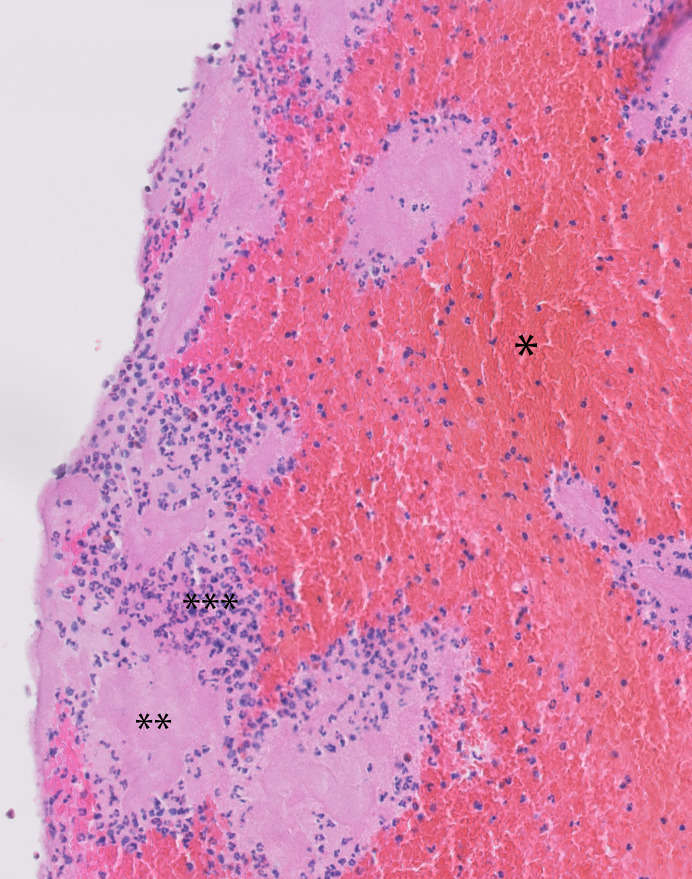

Fig. 1.

Example of histological appearance of fresh thrombus. Layered patterns of platelets, fibrin, erythrocytes, and intact granulocytes (H&E stain). *Erythrocytes, **thrombocytes, and ***granulocytes.

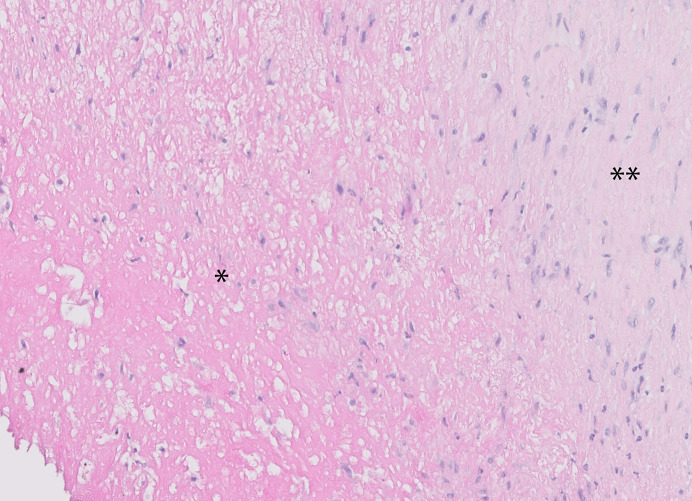

Fig. 2.

Example of the histology of an old thrombus, showing extensive necrosis and organization by myofibrocellular ingrowth and depositions of connective tissue (H&E stain). *Area of colliquation necrosis, **area of fibrocellular organization.

Patient Follow-Up

Patients were followed for 2 years for documentation of all-cause mortality. Time of death was obtained from the national population registry (Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics) and verified until January 1, 2019.

Statistical Analysis

Normality and homogeneity of the variances were tested using Shapiro-Wilk and Levene tests. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD or median (first, third quartile [Q1, Q3]) and were compared with the Student t test or Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages and were compared using Fisher’s exact test.

After stratification into fresh and old thrombus, event rates over time were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and linear trends were tested with the log-rank test. Finally, Cox proportional hazard analyses were used to assess the impact of fresh or older thrombus age on long-term mortality, adjusted for the effect of relevant clinical, angiographic, and procedural characteristics. Candidate covariates included all clinical characteristics (Table 1), rTPA administration before MT, occlusion location, time to thrombectomy, angiographic success of treatment (TICI flow grade), and stroke aetiology according to the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) criteria. All candidate covariates with p < 0.1 in univariate Cox proportional hazards analysis were included in the multivariable model. As a sensitivity analysis, the optimal model was additionally identified using Akaike’s information criterion using the same candidate covariates. Additionally, Cox proportional hazards analysis was repeated according to these steps in those LVOS patients that had successful MT, defined as a TICI flow grade of at least TICI 2B. All Cox proportional hazards models were preceded by verification of the proportional hazard assumption using Schoenfeld’s residuals. A p-value <0.05 (2-sided) was considered statistically significant.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics

| LVOS (n = 75) | Fresh (n = 40) | Old (n = 35) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 69±15 | 66±17 | 72±13 | 0.12 |

| Female gender | 41 (55) | 22 (55) | 19 (54) | 1.00 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension | 51 (68) | 26 (65) | 25 (71) | 0.62 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 22 (29) | 11 (28) | 11 (31) | 0.80 |

| Current nicotine | 14 (19) | 7 (18) | 7 (20) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (15) | 8 (20) | 3 (9) | 0.20 |

| Family history | 12 (16) | 6 (15) | 6 (17) | 1.00 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 30 (40) | 16 (40) | 14 (40) | 1.00 |

| Vascular disease | 30 (40) | 15 (38) | 15 (43) | 0.65 |

| TIA or stroke in history | 14 (19) | 7 (18) | 7 (20) | 1.00 |

| Medication | ||||

| Aspirin | 16 (21) | 8 (20) | 8 (23) | 0.79 |

| Clopidogrel | 7 (9) | 3 (8) | 4 (11) | 0.70 |

| OAC/DOAC | 21 (28) | 10 (25) | 11 (31) | 0.61 |

| rTPA | 35 (47) | 19 (48) | 16 (46) | 0.88 |

| NIHSS pre-MT | 17 (6.3) | 17 (6.0) | 18 (6.7) | 0.55 |

Baseline criteria and clinical characteristics of the total study population, and after stratification for thrombus age. Numbers are expressed as frequency (percentage) or mean ± standard deviation.

LVOS, large vessel occlusion stroke; fresh, fresh thrombus (<1 day old); old, old thrombus (>1 day old); TIA, transient ischaemic attack; OAC, oral anticoagulants; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulants; rTPA, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (thrombolysis); NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale at admission to the hospital; MT, mechanical thrombectomy.

The χ2 or independent sample T/median test was used to assess for differences in baseline characteristics (such as age, gender, risk factors, medication use, and NIHSS), MT data (such as use of rTPA, time to thrombectomy, and success rate), and follow-up data (such as modified Rankin Scale [mRS]) stratified for fresh and older thrombus. Univariate Cox regression analysis was used to assess the effect of thrombus colour on survival. All calculations were performed with the STATA 13.1 statistical software package (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and SPSS Statistics v25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics as well as the distribution according to fresh or older thrombus age. Table 2 demonstrates the distribution of fresh and older thrombi by stroke aetiology as defined by the TOAST criteria. No significant difference was found between fresh and older thrombus and its distribution over the TOAST criteria (p = 0.46). Nor did we find any significant difference between fresh or old thrombi stratified by thrombus colour (p = 0.53).

Table 2.

Stroke aetiology according to the TOAST criteria, stratified for thrombus age and thrombus colour

| Toast criteria | Fresh (n = 40) | Old (n = 35)* | Red (n = 20) | White (n = 24) | Mixed† (n = 31) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOAST 1 (large artery atherosclerosis) | 11 (28) | 6 (17) | 4 (20) | 6 (25) | 7 (23) |

| TOAST 2 (cardioembolic) | 21 (52) | 18 (51) | 12 (60) | 13 (54) | 14 (45) |

| TOAST 3 (small vessel disease) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| TOAST 4 (stroke of other determined aetiology) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| TOAST 5 (stroke of undetermined source) | 8 (20) | 10 (29) | 3 (15) | 5 (21) | 10 (32) |

Stroke aetiology according to the “Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment” (TOAST) criteria, stratified for thrombus age. Thrombus colour (red blood cell-rich [=red]/ fibrin-rich [=white]/ mixed [red blood cell and fibrin]). Numbers are expressed as a frequency and percentage. TOAST 3, not applicable.

Fresh, fresh thrombus (<1 day old); old, old thrombus (>1 day old).

*No significant difference was found between fresh/old thrombus and its distribution over the TOAST criteria (p value = 0.45).

†No significant difference was found between red/white/mixed colour thrombus and its distribution over the TOAST criteria (p value = 0.53).

Thrombi were classified as fresh (<1 day old) in 40 patients (53%) and older (>1 day) in 35 patients (47%). The distal ICA was the culprit vessel for thrombectomy in 12 patients (16%), the proximal middle cerebral artery (M1) in 52 patients (69%), the middle part of the middle cerebral artery (M2) in 10 patients (13%), and the vertebrobasilar artery system in 1 patient (1.3%). Almost half of LVOS patients received rTPA before MT (n = 35; 46.7%). Successful recanalization (TICI 2B/3) was achieved in 68 (90.7%) patients after a median of 1 pass (Table 3). No significant difference was found in the use of rTPA, time to MT, or success rate of MT by comparing fresh and old thrombus. Table 4 demonstrates an overview of thrombus characteristics on survival. Univariate Cox regression analysis did not show an association between thrombus colour and mortality on 2-year follow-up.

Table 3.

MT data

| Peri-procedural data | LVOS (n = 75) | Fresh (n = 40) | Old (n = 35) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to MT | 190 (163–249) | 193 (166–259) | 187 (150–218) | 0.53 |

| Location | ||||

| ICA | 12 (16) | 8 | 4 | |

| M1 | 52 (69) | 25 | 27 | |

| M2 | 10 (13) | 6 | 4 | |

| VA | 1 (1.3) | 1 | 0 | |

| TICI | ||||

| 0 | 4 (5.3) | 2 | 2 | |

| 1 | 2 (2.7) | 2 | 0 | |

| 2A | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 1 | |

| 2B | 8 (11) | 4 | 4 | |

| 3 | 60 (80) | 32 | 28 | |

| Success rate | 68/75 (91) | 36/40 (90) | 32/35 (94) | 0.83 |

Peri-procedural data from mechanical thrombectomy stratified for thrombus age. Numbers are expressed as frequency (percentage) or median (interquartile range).

Success of MT is defined as a TICI 2B score or higher after mechanical thrombectomy.

LVOS, large vessel occlusion stroke; fresh, fresh thrombus (<1 day old); old, old thrombus (>1 day old); rTPA, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (thrombolysis); time to MT, median time to mechanical thrombectomy in minutes; ICA, internal carotid artery; M1/M2, M1 en M2 segment of the middle cerebral artery; VA, vertebral artery; TICI, thrombolysis in cerebral infarction grading system.

Table 4.

Thrombus characteristics

| Thrombus characteristics | Total (n = 75) | Alive (n = 59) | Deceased (n = 16) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombus colour | ||||

| Red | 20 (27) | 15 (75) | 5 (25) | p = 0.87 |

| White | 24 (32) | 20 (83) | 4 (17) | |

| Mixed | 31 (41) | 24 (77) | 7 (23) | |

| Fresh thrombus | 40 (53) | 36 (90) | 4 (10) | p = 0.02 |

| Old thrombus | 35 (4.7) | 23 (66) | 12 (34) | |

Thrombus colour (red blood cell-rich [=red]/fibrin-rich [=white]/mixed [red blood cell and fibrin]) and thrombus age on survival and mortality on 2-year follow-up by using univariate Cox regression analysis. Numbers are expressed as a frequency (percentage). N: number of patients total, alive, and deceased during 2-year follow-up.

Clinical Outcomes

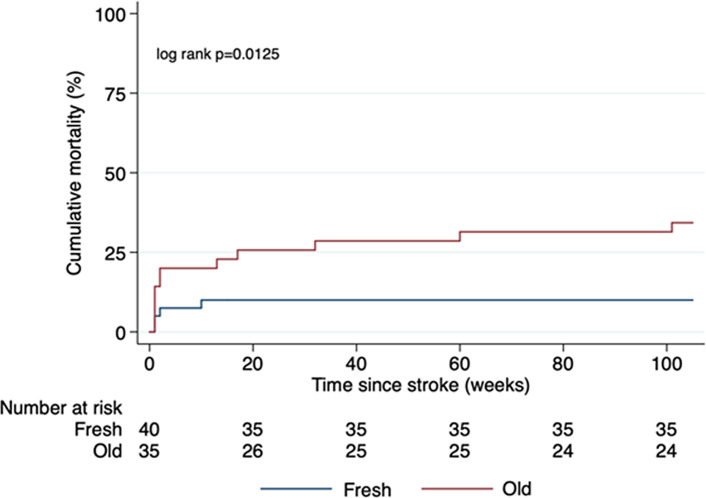

Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve for fresh versus old thrombi. The Kaplan-Meier estimate of mortality was higher for patients with older thrombi compared to those with fresh thrombi (log-rank p = 0.013). Univariate Cox proportional hazard analysis documented that thrombus age (p = 0.023), patient age (p = 0.020), and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) at hospital admission were associated with long-term mortality (p = 0.017). Time to thrombectomy (p = 0.136), hypertension (p = 0.230), hyperlipidaemia (p = 0.885), diabetes mellitus (p = 0.207), nicotine use (p = 0.554), atrial fibrillation (p = 0.139), vascular disease (p = 0.746), stroke (0.485), and thrombus colour (p = 0.87) were not associated with a higher mortality.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of mortality for fresh versus old thrombi in LVOS patients.

Mean mRS at 90 days after stroke did not show a significant association between fresh or old thrombus. Fresh thrombus mean 2.78 (1.76 SD), older thrombus mean 3.17 (2.0 SD), p = 0.13. Model identification using Akaike’s information criteria identified the same optimal predictive model including age, NIHSS, and old thrombus age. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis demonstrated that, after adjustment for age and NIHSS at admission, thrombus age was independently associated with long-term mortality (hazard ratio: 3.34 (95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 1.07–10.43; p = 0.038).

As a sensitivity analysis, the same steps were repeated for those LVOS patients that had successful MT, defined as post-MT TICI flow grade of at least TICI 2B. Univariate Cox regression analysis in this population identified thrombus age, NIHSS at hospital admission, and age as associated with long-term mortality (p < 0.1). However, model identification using Akaike’s information criteria identified the combination of age, NIHSS at hospital admission, thrombus age, rTPA use prior to MT, and diabetes mellitus as the optimal model to predict long-term mortality. After correction for these variables, thrombus age remained independently associated with long-term mortality (hazard ratio [95% CI]: 5.96 [1.25–28.53], p = 0.025). Univariate Cox regression analysis on overall survival on specific TOAST criteria for fresh versus older thrombus (as a subanalysis) did not show any significant association.

Discussion

The present study is the first to explore the relationship between thrombus age and long-term mortality in LVOS patients treated with MT. In these patients, old thrombi were present in almost half of the patients, and the presence of an older thrombus was an independent predictor of long-term mortality. No other clinical or procedural characteristics were associated with survival in this small study. A recent published study by Lin et al. [10] also found a comparable relation between thrombus age and clinical outcome in acute ischaemic stroke. In a study of 107 patients, they found a worse mRS score at 90 days in patients with an old thrombus (we found a trend, but no significant difference). However, they did not investigate the effect of thrombus age on survival. Furthermore, there are some other clear differences between our studies such as the definition of older thrombi and the technique used to determine thrombus age. Additionally, Lin et al. [10] used dichotomous variables of mRS (≤2 was seen as a good functional outcome and >2 was seen as a poor outcome) in its comparison to fresh/old thrombus, where we used absolute numbers. Different definitions of thrombus age have resulted in a higher total of patients with older thrombi in their study. Regardless, both studies showed a worse outcome for older thrombi. In another small study from Niesten et al. [11], the prevalence of fresh and old thrombus was examined in 22 LVOS patients. The authors documented a majority of fresh thrombi (73%) and organization in only 9% of patients. This is not in line with our study and the study of Lin et al. [10]. The outcome was not investigated in this particular study either. Earlier pathology studies in other acute vascular syndromes like ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction showed a similar prevalence of old thrombi and a similar association between the presence of older thrombus and higher mortality [5, 6, 12, 13].

The pathophysiologic mechanism is an avenue for further research. Older thrombi, especially in the lytic stage with a fragile (necrotic) structure, may be associated with a higher risk of microembolization which is related to recurrent stroke and higher mortality [14]. Furthermore, the presence of tissue decay and organization may be a marker of more advanced disease or older thrombus age and consequently associated with higher mortality [15, 16]. However, thrombus age remained independently associated with 2-year mortality even after adjustment for the confounding effect of patient age and the use of rTPA, and even after restricting the analysis to patients with successful MT, which suggests there is more to thrombus age as a prognostic marker. Other thrombus characteristics may contribute to a worse prognosis as well, for example, thrombus composition (fibrin-rich or red blood cell [RBC]-rich). RBC-rich thrombi are typically associated with favourable outcomes, while fibrin-rich thrombi have a less favourable outcome [4]. However, our results did not show this association, possibly due to the smaller sample size. Another study found no correlation between thrombus age and thrombus colour (RBC-rich or fibrin-rich) [17]. Other parameters may include biochemical and immunological markers that have been investigated mostly in thrombi obtained from patients undergoing PCI. Further larger studies are warranted to provide more insight into the mechanism by which thrombus age is related to clinical outcomes in acute vascular syndromes.

Limitations

The present study represents a prospective observational study in a relatively small group of 75 LVOS patients. Although consecutive patients were enrolled in this histopathology study, the observational nature of our data needs to be considered in the interpretation of the study results.

For each thrombus, two separate specimens/slices were prepared for analysis since it is not possible to analyse the entire thrombus. These slices were taken at the largest diameter of the thrombus. Nevertheless, there is a small risk of missing (and therefore) underreporting of organized thrombus formation, leading to bias.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates an independent prognostic value of older thrombi with signs of lysis or organization in LVOS patients. Future larger studies are warranted to elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms, clinical implications, and potential treatment consequences of this finding.

Statement of Ethics

This study protocol was reviewed, and the need for approval was waived by MEC-U W23.057. The need for informed consent was waived by MEC-U W23.057.

Conflict of Interests Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Sources

The authors did not receive any grant or funding for this project.

Author Contributions

Martijn Meuwissen, Tim van de Hoef, Allard van der Wal, Michel Remmers, Kartika Pertiwi, Onno de Boer, and Bart van Gorsel: concept, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing, and manuscript review. Louwerens Vos, Bas Scholzel, Dirk Haans, Ruud Aarts, Rob Versteylen, Anouk van Norden, Casper van Oers, Jeroen Vos, Sander Ijsselmuiden, Ben van den Branden, Farshad Imani, Marco Alings, Robbert de Winter, and Ishita Miah: data collection and concept review.

Funding Statement

The authors did not receive any grant or funding for this project.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Rai AT, Link PS, Domico JR. Updated estimates of large and medium vessel strokes, mechanical thrombectomy trends, and future projections indicate a relative flattening of the growth curve but highlight opportunities for expanding endovascular stroke care. J Neurointerv Surg. 2022;0:1–2022–019777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goyal M, Menon BK, Van Zwam WH, Dippel DWJ, Mitchell PJ, Demchuk AM, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387(10029):1723–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, et al. 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49(3):e46–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jolugbo P, Ariëns RAS. Thrombus composition and efficacy of thrombolysis and thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2021;52(3):1131–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kramer MCA, Van Der Wal AC, Koch KT, Ploegmakers JP, van der Schaaf RJ, Henriques JPS, et al. Presence of older thrombus is an independent predictor of long-term mortality in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2008;118(18):1810–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li X, Kramer MC, Damman P, van der wal AC, Grundeken MJ, van Straalen JP, et al. Older coronary thrombus is an independent predictor of 1-year mortality in acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Clin Invest. 2016;46(6):501–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Menon BK, D’Esterre CD, Qazi EM, Almekhlafi M, Hahn L, Demchuk AM, et al. Multiphase CT angiography: a new tool for the imaging triage of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Radiology. 2015;275(2):510–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zaidat OO, Yoo AJ, Khatri P, Tomsick TA, von Kummer R, Saver JL, et al. Recommendations on angiographic revascularization grading standards for acute ischemic stroke: a consensus statement. Stroke. 2013;44(9):2650–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Laridan E, Denorme F, Desender L, François O, Andersson T, Deckmyn H, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in ischemic stroke thrombi. Ann Neurol. 2017;82(2):223–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lin J, Guan M, Liao Y, Zhang L, Qiao H, Huang L. An old thrombus may potentially identify patients at higher risk of poor outcome in anterior circulation stroke undergoing thrombectomy. Neuroradiology. 2023;65(2):381–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Niesten JM, Van Der Schaaf IC, Van Dam L, Vink A, Vos JA, Schonewille WJ, et al. Histopathologic composition of cerebral thrombi of acute stroke patients is correlated with stroke subtype and thrombus attenuation. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rittersma SZH, Van Der Wal AC, Koch KT, Piek JJ, Henriques JPS, Mulder KJ, et al. Plaque instability frequently occurs days or weeks before occlusive coronary thrombosis: a pathological thrombectomy study in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2005;111(9):1160–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kramer MC, van der Wal AC, Koch KT, Rittersma SZH, Li X, Ploegmakers HP, et al. Histopathological features of aspirated thrombi after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-Elevation myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e5817–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jaffe R, Charron T, Puley G, Dick A, Strauss BH. Microvascular obstruction and the no-reflow phenomenon after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2008;117(24):3152–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sheriff F, Diz-Lopes M, Khawaja A, Sorond F, Tan CO, Azevedo E, et al. Microemboli after successful thrombectomy do not affect outcome but predict new embolic events. Stroke. 2020;51(1):154–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Farina F, Palmieri A, Favaretto S, Viaro F, Cester G, Causin F, et al. Prognostic role of microembolic signals after endovascular treatment in anterior circulation ischemic stroke patients. World Neurosurg. 2018;110:e882–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eriksen E, Herstad J, Pertiwi KR, Tuseth V, Nordrehaug JE, Bleie O, et al. Thrombus characteristics evaluated by acute optical coherence tomography in ST elevation myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0266634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.