Key Clinical Message

In developing countries, VVF mainly occurs due to obstructed labor unlike developed countries where common causes are radiotherapy and malignancy. Due to social taboos, patients do not seek medical attention for problems like urinary incontinence and dysuria, thus presenting very late.

Keywords: bladder calculus, case report, cystolithotomy, vesicovaginal fistula

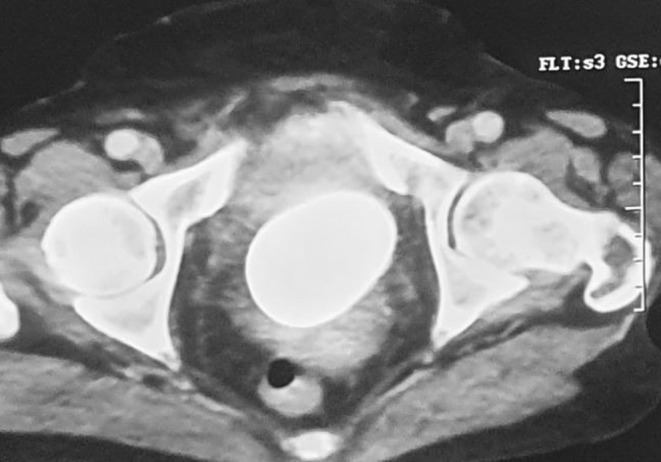

CECT showing the massive bladder calculus.

1. INTRODUCTION

Obstetric fistulas are abnormal connections between the genital tract and urinary/gastrointestinal tract, usually resulting in fecal or urinary incontinence. 1 A vesicovaginal fistula (VVF) is an abnormal communication between the bladder transitional epithelium and the vaginal squamous epithelium. 2 VVF is the most prevalent type of urogenital fistula and represents a devastating morbidity in gynecologic urology. 3 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates 50,000 to 100,000 new cases of obstetric fistula each year, globally. In Nepal, there is estimated incidence of 56.4 fistulas per 100,000 women of reproductive age group per year. 1 Bladder calculi account for 5% of all urinary tract stones and 1.5% of all urinary hospitalizations, and are the commonest manifestation of lower urinary tract stones. 4 Worldwide, very few cases of clinically evident bladder calculi presenting as VVF have been reported. We report a case of a large bladder calculi associated with VVF in an elderly Nepalese female.

2. CASE PRESENTATION

A 73‐years‐old lady presented with complaints of pain abdomen and abdominal discomfort for 3 months. The pain was mild, dull aching, intermittent, insidious, and non‐radiating, and was associated with a palpable stony hard mass in the hypogastrium. She was a hypertensive under medication for the past 10 years. Her past medical and surgical history were not suggestive of any underlying pathology.

Meanwhile, she had a history of urge incontinence since a year which progressed to continuous urinary leakage for a month. It used to soak all her undergarments and bedclothes, which then lead to discovery of the problem by her family. The incontinence was associated with pelvic pain, increased frequency and nocturia, but she had no hematuria or fever. She tried hiding the problem from her family as long as she could, and isolated herself due to the fear of embarrassment. Initially, she used to wrap cloth around her genitals which was later replaced by diaper.

On examination, her general condition was fair. She was clinically pale and had edematous skin overlying the bladder. Tenderness along with a hard, palpable, round mass was present in the suprapubic region, extending up to the umbilicus. Bimanual examination revealed a stony hard mass abutting the physical defect in the anterior vaginal wall. Urethral opening was found to be completely blocked with calculi, and there was urine leak through the defect.

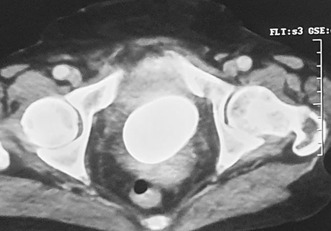

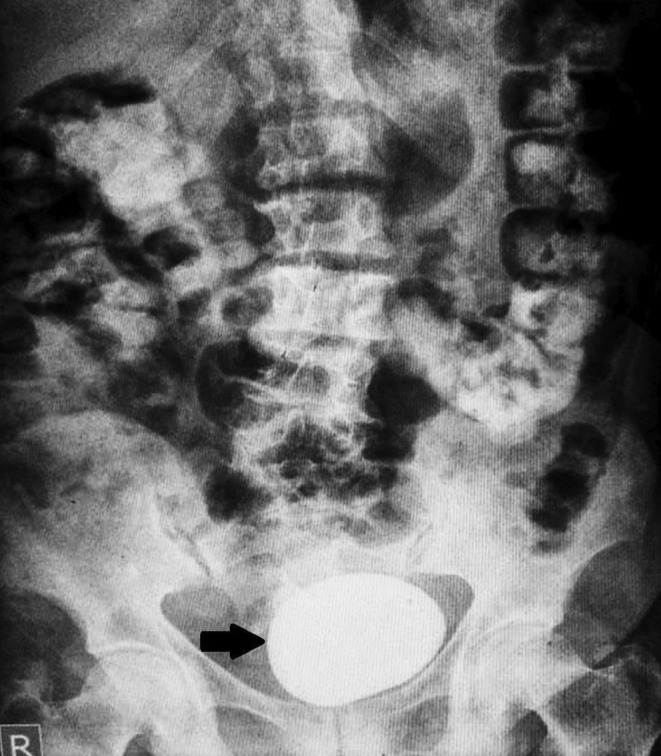

Routine laboratory investigations showed her hemoglobin to be 8.6 g/dL, leukocytosis with neutrophilia and elevated ESR. Urine tests revealed albuminuria. All other routine investigations were within normal limits. Plain X‐Ray Kidney, Ureter and Bladder (KUB) showed a large, radiopaque mass in the pelvic area (Figure 1). Then on computed tomography (CT) scan, a large vesical calculus measuring 7 × 5 × 6.2 cm was seen causing obstruction of bilateral vesicoureteral junction (Figure 2). Bladder was partially distended with thickened wall, which was suggestive of chronic cystitis. Bilateral hydroureteronephrosis (right: moderate, left: gross with parenchymal thinning) was appreciated. Right renal cortical cysts and left tiny nephrolithiasis were also found; however, she did not have chronic kidney disease. Contrast enhanced CT (CECT) revealed non‐excreting left kidney. On cystoscopy, vaginal opening was seen in the bladder with clear visualization of stones.

FIGURE 1.

Plain X‐ray KUB showing a large calculus.

FIGURE 2.

CECT showing a hyperdense shadow in the bladder, suggestive of the massive calculus.

The patient underwent a successful single‐staged surgery with a transabdominal open cystolithotomy and transvaginal fistula repair (Figure 3). Postoperative course was uneventful. At 1 year follow‐up, she remains asymptomatic and is doing well.

FIGURE 3.

Calculus obtained after surgery.

3. DISCUSSION

Obstetric population in low and low‐middle income countries suffer from various communicable and non‐communicable diseases. 5 VVF continues to be a major problem in women's health in developing countries, where majority of the cases occur due to prolonged and obstructed labor. 1 , 6 , 7 Other factors responsible can be accidental injury at the time of cesarean section, forceps delivery, traditional surgical practices such as gishiri and complications of criminal abortion. 8 This is in contrast with high income countries where VVF occurs after radiotherapy, malignancy, and surgery. 2 , 9 In addition to inherent morbidity itself, VVF is also associated with other complicating conditions such as amenorrhea, foot drop, dermatoses, vaginal stenosis, and bladder calculi. 3 , 10 Vaginal foreign body and bladder calculi are rarely found to be the cause of VVF. 6 , 7

Bladder calculi may form due to urinary infection, urinary stasis, dehydration, foreign bodies, diet, and debris desquamation from vaginal epithelium into the bladder. 2 , 6 Bladder calculi leading to VVF is an extremely rare occurrence, and its exact pathogenesis is unknown. However, pressure necrosis and inflammation as a result of obstructed labor or a bladder calculus can lead to VVF. 3 , 11

Bladder calculi with VVF usually presents with recurrent urinary tract infection, gross hematuria and pyuria, suprapubic pain and dysuria, perineal swelling and urinary incontinence. 2 , 6 Diagnosis is made after detailed history taking focusing especially on social history, a thorough and proper physical examination and investigations. Cystoscopy is preferred for definitive diagnosis, whereas X‐ray‐KUB, Ultrasonography (USG), CECT, dye tests (methylene blue), blood and urine analysis also aid in diagnosis. 2 , 3 , 9 , 12

Management is primarily surgical, addressing both the fistula and calculi. Stone management usually depends on size. Cystolitholapaxy is done for calculi less than 3 cm, and those more than 3 cm are managed by open cystolithotomy. Fistula repair is done either transvaginally or transvesically, with/out flap interposition. Controversy exists whether a two stage procedure (delayed repair, wherein stone removal is carried out followed by fistula repair after 3 months) is superior to concomitant repair. 2 , 6 Because of the advantages of concomitant repair in terms of patient outcomes, cost effectivity, and patient compliance, recent trend is toward using concomitant repair, as was the case in our patient. 13

This case is important not only for the clinical knowledge it imparts, but also because of its social association. Especially in low‐ and middle‐income countries like Nepal, various other causes like illiteracy, teenage status at delivery, lack of skilled birth attendance are among the major factors that lead to VVF. 1 Moreover, VVF causes chronic urinary incontinence in women which can lead to social isolation, divorce, desertion and even assault. 14 The taboo associated with seeking medical care especially for sexual and reproductive problem in woman is still deeply rooted in many societies, leading to significant morbidity and mortality. This psychosocial stigma must be addressed by raising awareness within the community. We recommend establishment of strong maternal health policies and programs for enhancement of the quality and accessibility of obstetric fistula services. This is a potentially manageable condition and can help improve the quality of life of females in various communities.

Because of the disease's rarity, we publish this case to underline the necessity of early detection of vesical stones in VVF and to highlight the clinical and social aspects of this condition.

4. PATIENT PERSPECTIVE

Patient was satisfied with the treatment she received, and she had agreed to come for regular follow‐up visits as per necessity. Also, she was glad to be a part of this report as she could also help us and people around the world learn about such case.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Muna Sharma: Conceptualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Mitesh Karn: Conceptualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Hritika Adhikari: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Binita Basnet: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Ishuvi Bhattarai: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Sachita Chapagain: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Chandika Pandit: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

WRITTEN CONSENT FROM THE PATIENT

An informed written consent was obtained from the patient for writing and publishing this case report.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

None.

Sharma M, Karn M, Adhikari H, et al. Vesicovaginal fistula associated with massive bladder calculi: An urogynecological case report. Clin Case Rep. 2023;11:e8281. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.8281

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are included in the article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Tebeu PM, Upadhyay MT. Campaign to End Fistula in Nepal: Report on Need Assessment for Obstetric Fistula in Nepal. Vol 57. Women's Rehabilitation Center (WOREC); 2011. Available from: http://countryoffice.unfpa.org/nepal/drive/NeedAssesmentofObstetricFistulainNepal.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kholis K, Palinrungi MA, Syahrir S, Faruk M. Bladder stones associated with vesicovaginal fistula: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;75:122‐125. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Creanga AA, Genadry RR. Obstetric fistulas: a clinical review. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2007;99(Suppl 1):40‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Minami T, Koshiba K, Masuda H. Giant Vesical Calculus: a Case Report. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1964;10(107):345‐348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Karn M, Sharma M. Climate change, natural calamities and the triple burden of disease. Nat Clim Chang. 2021;11(10):796‐797. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dalela D, Goel A, Shakhwar SN, Singh KM. Vesical calculi with unrepaired vesicovaginal fistula: a clinical appraisal of an uncommon association. J Urol. 2003;170(6):2206‐2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Siddiqui NY, Paraiso MFR. Vesicovaginal fistula due to an unreported foreign body in an adolescent. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007;20(4):253‐255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hilton P. Vesico‐vaginal fistulas in developing countries. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2003;82(3):285‐295. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(03)00222-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheng MH, Chao HT, Horng HC, Hung MJ, Huang BS, Wang PH. Vesical calculus associated with vesicovaginal fistula. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2014;3(1):23‐25. doi: 10.1016/j.gmit.2013.07.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ahmed S, Holtz SA. Social and economic consequences of obstetric fistula: life changed forever? Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2007;99(Suppl 1):10‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mukerji AC, Ghosh BC, Sharma MM, Taneja OP. Spontaneous urinary fistula Caused by vesical calculus. Br J Urol. 1970;42(2):208‐212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alan A, Cardoso C, Paes ADS, Afonso T, Celestino C. Giant bladder stone in a patient with vesicovaginal fistula caused by bladder wall ischemia due to unassisted prolonged labor in the amazon jungle. Int J Med Rev Case Rep. 2018;2:82‐84. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shephard SN, Lengmang SJ, Kirschner CV. Bladder stones in vesicovaginal fistula: is concurrent repair an option? Experience with 87 patients. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(4):569‐574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Malik MA, Sohail M, Malik MTB, Khalid N, Akram A. Changing trends in the etiology and management of vesicovaginal fistula. Int J Urol. 2018;25(1):25‐29. doi: 10.1111/iju.13419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are included in the article.