Abstract

The use of autoclitics can influence the behavior of individuals making choices when responding to a survey (e.g., checking or unchecking a box). In two studies, we investigated the effects of autoclitics as “nudges” on choice by manipulating different frames (opt-in and opt-out) and default options (i.e., unchecked and checked boxes). Undergraduate students recruited from behavioral science courses engaged with materials in the study. In study 1, we used an online survey at the beginning of the semester offering the choice of whether to enroll in extra-academic activities (i.e., practice tests) available via the online course platform, Blackboard. We randomly assigned students into one of four groups: 1) option to enroll with an unchecked box, 2) option to not enroll with an unchecked box, 3) option to enroll with a checked box, or 4) option to not enroll with a checked box. Results showed that the option to not enroll with an unchecked box produced higher enrollment to receive extra academic activities. In the middle of the semester, we conducted a within-subject arrangement wherein students who initially opted out of receiving activities had the option to accept them following exposure to the negative autoclitic frame. Most of these students opted into receiving activities. In study 2, we replicated the methods of study 1 in Canvas, a different course platform, and obtained similar results. We briefly discuss the implications of a nudge for ethical consent.

Keywords: Autoclitic, choice architecture, opt-in, opt-out, nudge, consent

Choosing one alternative over another can be interpreted as operant behavior. Behavioral economists have studied how the strategic use of economic principles can “nudge” behaviors toward desirable outcomes (Reed et al., 2013). An example of environmental arrangements designed to “nudge” behavior is choice architecture (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008)—the presentation of choices that may include selecting (a) the number of choices presented (e.g., two options versus ten), (b) framing of choice options (e.g., opt-in and opt-out arrangements), and/or (c) presence of a default (e.g., preselected option). From an operant perspective, “nudges” in the form of choice architecture can be interpreted as an antecedent manipulation of certain stimuli (e.g., framing and defaults) that exert stimulus control on choice.

Outside behavior analysis, prior research on choice framing (Fisher & Mandel, 2021), an element of choice architecture, is shown to influence decision making. In a hypothetical scenario related to the U.S. government’s response to a disease outbreak, for example, Tversky and Kahneman (1981) found that participants’ choice of policy strategies differed depending on whether options were described in terms of people who will be saved versus those who would die.

In another example of choice framing, Johnson et al. (2002) explored effects of defaults and framing in opt-in and opt-out options in an online marketing survey. Choosing whether to opt-in or opt-out into receiving health surveys, participants were randomly assigned to one of four framing/default groups: (1) option to enroll—hereafter referred to as “positive frame”—with unchecked box (no default), (2) option to not enroll—hereafter referred to as “negative frame”—with unchecked box (no default), (3) positive frame with checked box (default), and (4) negative frame enroll with checked box (default). Their study revealed that the negative frame with no default (Frame 2) produced higher rates of participating compared to the other framing and default options (Frame 2 = 96.3%; Frame 3 = 73.8%; Frame 4 = 69.2%; Frame 1 = 48.2%). Despite these results, full interpretations of the study are difficult given the article’s limited description of procedures, ways to ensure strict stimulus control, and observing behaviors.

Along with adding more detailed procedural descriptions, interpretations of the findings of Johnson et al. (2002) and others may be improved using a verbal operant framework. From a verbal operant perspective, choice framing can include mands emitted by a speaker (e.g., request to agree or disagree with policies and procedures), which are directed to a listener who will then respond to this mand (e.g., by agreeing or disagreeing with policies or guidelines) as a speaker. Mands may include autoclitics to enhance one alternative and thus, from the speaker’s perspective, increase the likelihood of the listener making a “desirable” choice. A literature review of empirical applications of verbal operants (Sautter & LeBlanc, 2006) found that autoclitics are the least studied verbal operant. In this review, they identified one empirical article by Lodhi and Greer (1989) that focused on children’s analysis of speaker- and listener-oriented operants when playing with different toys. Following the review by Sautter and LeBlanc (2006), it is possible to find other empirical studies on autoclitics in children (e.g., Luke et al., 2011; Speckman et al., 2012), adults (e.g., Cengher et al., 2020), and on autoclitic analogs in pigeons (Kuroda et al., 2014), but more empirical research on the topic is warranted.

Autoclitics are second-order verbal operants that can modify a verbal response and increase its effectiveness. Skinner (1957) describes four categories of autoclitics: descriptive, quantifying, qualifying, and relational. In the studies described in this paper, only two types are relevant. Descriptive autoclitics are emitted by a speaker and consist of verbal behavior descriptive of their own behavior. Descriptive autoclitics can also indicate the circumstances or conditions evoking a response. One subtype of the descriptive autoclitic expresses relations between a response and other verbal behavior of the speaker or listener (e.g., “I agree with…”). This form permits the listener to relate the response to other aspects of the situation and subsequently respond more efficiently. Relatedly, descriptive autoclitics may also be characterized as negative autoclitics, which qualify or cancel an accompanied response (e.g., “I do not…) (Skinner, 1957, p. 317).

Whereas descriptive autoclitics can function as tacts of our own behavior, qualifying autoclitics can modify the tact such that the intensity or direction of the listener’s behavior is affected. In these cases, the autoclitic may specify an action upon the listener’s part and can function as a mand. One type of qualifying autoclitic is negation—that is, a mand specifying the cessation of behavior on the part of the listener (“Don’t…”) and having the “force” of a mand (Skinner, 1957, p. 322).

Further, descriptive and qualifying autoclitics may be combined in a single response (Skinner, 1957, p. 325). Such autoclitics could be characterized as operating within opt-in (e.g., “Enroll me…”) and opt-out (e.g., “Do not enroll me…”) arrangements in choice architecture manipulations. When asking someone whether they agree with policies or procedures, for example, this framing option could function as a descriptive autoclitic that specifies or tacts a relation between a response and other verbal behavior of speaker or listener (e.g., speaker tacts own behavior of agreeing to receive notifications in the “I agree to receive notifications” statement that can serve as a discriminative stimulus for the listener to behave by agreeing or not with speaker). This could also function as a qualifying autoclitic that mands the listener to agree with the speaker (e.g., speaker mands listener to agree with them). When a negative assertion is presented as a “negative” descriptive autoclitic and/or “negation” qualifying autoclitic, the same logic can be applied. That is, the framing option could function as either a descriptive and/or qualifying autoclitic in relation to a “I do not agree” statement. Although we can interpret framing options for opt-in and opt-out arrangements as autoclitics, it stands to reason that the presence of defaults have an autoclitic function as well. An opt-in arrangement with a checked box default (“☑ Enroll me…”), for example, can function as a stronger and more explicit mand upon the listener to behave than an option with an unchecked box default (“☐ Enroll me…”).

The benefits of research on choice architecture and nudging are far reaching. Previous studies have shown them to be effective for encouraging energy sustainability behavior (Nolan et al., 2008), healthier food choices (Ensaff, 2021), and improved physical activity patterns (Bhattacharya et al., 2015). Choice architecture and nudging can even be lifesaving; increasing the likelihood of safer driving speeds (Choudhary et al., 2022; Rubatelli et al., 2021; Thaler & Sunstein, 2008) and increasing supply of donated organs (Whyte et al., 2012). Notably present in each of these examples are changes to behavior made without explicit contingency-shaping (Tagliabue et al., 2019). Rather, successful nudging often involves rule-governance in influencing choice behavior, which is further shaped by social (i.e., verbal) environments and reinforcement histories (Rachlin, 2015). Examining choice architecture and nudging from a verbal behavior perspective, therefore, may be a key avenue by which future applications are strengthened.

In addition, there are clear benefits on integrating an interpretation of verbal behavior into these studies. The majority of the current literature in behavioral economics and choice architecture describes methods to assess decision making and choice via self-report measures. These procedures involve exposing participants to verbal stimuli that can evoke their verbal behavior. However, we are aware of no studies that analyzed possible effects of verbal stimuli (e.g., vignettes, scenarios, question framing) from a verbal operant perspective. A functional perspective of verbal behavior in behavioral economics studies can likely bring new insights to the understanding of verbal processes occurring during the decision-making process of making a choice, and can help refine procedures by controlling and analyzing verbal operants that can potentially be evoked in behavioral economics tasks.

Despite examples of choice architecture and nudge within the broader literature, we are aware of no studies designed and interpreted from a behavior-analytic framework nor those that explore effects of different autoclitic framing during opt-in/opt-out and default manipulations. Further, overall research on autoclitics is relatively limited. Despite the presence of a small number of publications on autoclitic research (e.g., Cengher et al., 2020; Kuroda et al., 2014; Luke et al., 2011), more empirical research on the topic is warranted. Thus, Study 1 aimed to add to the literature by both replicating procedures described by Johnson et al. (2002) in a controlled setting with undergraduate students using the Blackboard platform and analyzing data within an operant framework. Study 2 replicated procedures from Study 1 with a different group of students using the Canvas platform. Finally, we discuss the potential ethical implications for using nudges in environmental manipulations.

General Method

Participants

Undergraduate students enrolled in introductory behavioral science courses at a large, Midwestern university were sampled for the current study. In Study 1, 192 students participated. Of these, 31 students identified as male, 158 as female, two as non-binary, and one as gender-fluid. Students also selected their age range wherein four were under age 18, 185 were between ages 18–24, and two were between ages 25–34. One student did not indicate their age range.

Sixty-five students participated in Study 2. Within this sample, eight students identified as male, 55 as female, one as non-binary, and one preferred not to answer. Within each age range category, one student was under 18, 62 were aged 18–24, one aged 25–34, and one aged 35–44. All procedures used in this study were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Setting and Materials

Students completed all study activities online using a commercially available survey platform (i.e., Qualtrics, Provo, UT). We implemented all components of the current studies as part of routine course sequencing. The IRB approved procedures of this study as a retrospective analysis of previously collected data. When recruiting participants, we informed students that completion of study surveys was optional (i.e., students would not be compensated nor penalized for participation/lack thereof). An announcement appeared on online course platforms (i.e., Blackboard and Canvas) to all students prior to distributing the survey, stating that the purpose of the survey was to provide instructors a chance to learn more about the students and to offer additional learning opportunities. The announcement contained the link for the survey, which directed to the informed consent. The first part of the survey included the opt-in/out arrangement and is described in the section below. The second part of the survey included demographic questions (e.g., age, gender, pronouns) and questions related to their academic interests and experience (e.g., anticipated or declared major). In addition, the survey indicated responses would be used for educational/academic purposes and completion would not be counted toward their grades. As we implemented all components of the current studies as part of routine course sequencing and we used retrospective analysis (i.e., we analyzed data after the course ended) with the IRB approval, we did not have debriefing sessions. Students who opted into receiving extra academic activities received them throughout the course sequencing.

Experimental Design and Dependent Variable

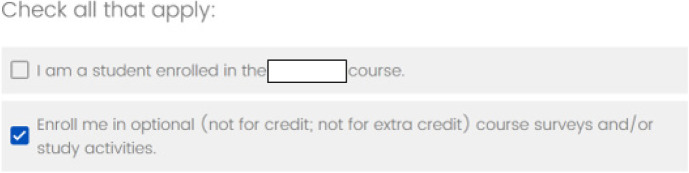

The dependent variable was percent enrollment in academic activities. Independent variables were the autoclitic frames (positive or negative) and the defaults (checked or unchecked box) presented on the screen. To increase the likelihood of adequate observing responses to independent variables, we designed the Qualtrics survey such that only primary visual stimuli were present on the survey screen page (i.e., no other questions or statements appeared on that page). In addition, we added an observing response requirement for all respondents. The first statement presented on the screen read, “I am a student enrolled in the [name of the course]” preceded by an unchecked box. The second statement on the screen referred to the type of independent variables presented, as described above. To advance in the survey to the next page, students were required to check the box for that first statement. All respondents were students enrolled in the course; thus, requiring them to check the box served to potentially ensure attending to the screen. This procedure was identical for all students and in all phases of the study. The only difference for all conditions was the type of independent variables presented (i.e., type of autoclitic framing and box).

Both studies were conducted during regular university terms. We conducted Study 1 during the Fall 2021 semester and Study 2 during the Spring 2022 semester. Both studies also included two phases and had identical experimental design and procedures. We used the Blackboard for Study 1 and replicated its procedures in Canvas in Study 2.

Phase 1

In the beginning of the semester, students were randomly assigned to receive one of four message frames: Frame 1 = positive frame with unchecked box (i.e., “☐ Enroll me…”); Frame 2 = negative frame with unchecked box (i.e., “☐ Do NOT enroll me…”); Frame 3 = positive frame with checked box (i.e., “☑ Enroll me…”); or Frame 4 = negative frame with checked box (i.e., “☑ Do NOT enroll me…”). Table 1 describes these frames and how they differed in terms of autoclitic framing, default, opt-in/out arrangement, and choice options for students. Frames 1 and 3 consisted of opt-in arrangements to enroll and receive surveys and extra practice activities for the course. In this context, opting-in may be viewed as explicit consent to enroll for receiving additional information related to the course.

Table 1.

Autoclitic Framing, Default, Opt-in/out Arrangement, and Choice Options

| Group | Description | Framing | Default and Opt-in/out Arrangement | Choice Options |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ☐ Enroll me in optional (not for credit/not for extra credit) course surveys and/or study activities | Positive | Unchecked box: Students need to check box to opt-in |

Students could: • Check the box and enroll OR • Keep the box unchecked and not enroll (lower response effort) |

| 2 | ☐ Do not enroll me in optional (not for credit/not for extra credit) course surveys and/or study activities | Negative | Unchecked box: Students need to check box to opt-out |

Students could: • Check the box and not enroll OR • Keep the box unchecked and enroll (lower response effort) |

| 3 | ☑ Enroll me in optional (not for credit/not for extra credit) course surveys and/or study activities | Positive | Checked box: Students need to check box to opt-in |

Students could: • Keep the box checked and enroll (lower response effort) OR • Uncheck the box and not enroll |

| 4 | ☑ Do not enroll me in optional (not for credit/not for extra credit) course surveys and/or study activities | Negative | Checked box: Students need to check box to opt-out |

Students could: • Keep the box checked and not enroll (lower response effort) OR • Uncheck the box and enroll |

Phase 2

In the middle of the semester, students receiving Frames 1, 3, and 4 who opted out of enrolling received a second opportunity to enroll into receiving additional information related to the course. We chose this manipulation because Frame 2 produced higher enrollment—see Results section below—in Phase 1. Thus, we were able to collect within-subject data for these students and compare exposure to different independent variables (i.e., variations of autoclitic framing and box default). For example, a student assigned to receive Frame 1 (positive frame with unchecked box) in Phase 1 who opted out of enrolling (i.e., did not enroll into receiving extra receiving) had another opportunity to opt into enrolling in Phase 2 when assigned Frame 2 (negative frame with unchecked box).

Study 1 Results

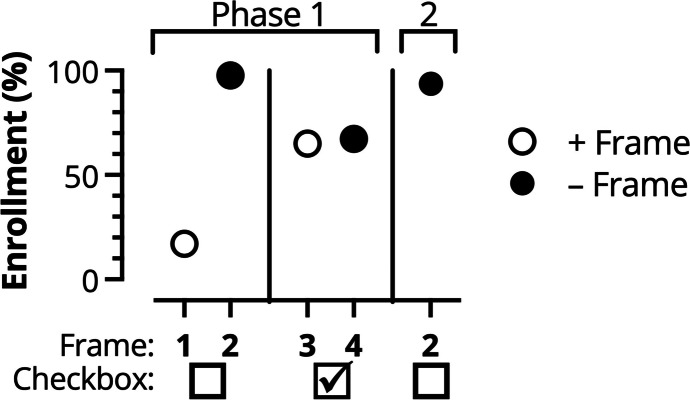

A total of 192 students engaged the enrollment email in Phase 1. We contacted students using the Blackboard platform. Fifty-three students were randomly assigned by Qualtrics to receive Frame 1; 44 assigned to receive Frame 2, 43 assigned to receive Frame 3; and 52 assigned to receive Frame 4. Table 2 summarizes the number of students who enrolled and did not enroll into receiving study materials and percentage for each group in both phases. Overall, Frame 2 (negative frame with unchecked box) produced the highest enrollment (97.7%, 43 out of 44 students enrolled. Frame 4 (negative frame with checked box) produced the second highest enrollment (67.3%, 35 out of 52), followed by Frame 3 (positive frame with box checked; 65.1%, 28 out of 43). Frame 1 (positive frame with unchecked box) produced the lowest enrollment (17%, 9 out of 53). These data are displayed in Figure 2. The x-axis depicts the box default options (checked or unchecked). Closed circles represent the use of negative frames and open squares the use of positive frames. The y-axis depicts the enrollment percentage. Negative frames produced higher percentage of enrollment compared to positive frames.

Table 2.

Enrollment for Study 1 and 2 across Phases

| Group | Description | Study 1 – Phase 1 | Study 1 – Phase 2 | Study 2 – Phase 1 | Study 2 – Phase 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ☐ Enroll me in optional (not for credit/not for extra credit) course surveys and/or study activities |

17% 9 out of 53 students |

17.6% 3 out of 17 students |

||

| 2 | ☐ Do not enroll me in optional (not for credit/not for extra credit) course surveys and/or study activities |

97.7% 43 out of 44 students |

93.7% 30 out of 32 students |

100% 12 out of 12 students |

84.2% 16 out of 19 students |

| 3 | ☑ Enroll me in optional (not for credit/not for extra credit) course surveys and/or study activities |

65.1% 28 out of 43 students |

14.2% 2 out of 14 students |

||

| 4 | ☑ Do not enroll me in optional (not for credit/not for extra credit) course surveys and/or study activities |

67.3% 35 out of 52 students |

63.6 % 14 out of 22 students |

Fig. 2.

Enrollment rate per default and autoclitic frame in Study 1

To test the replicability of these results, we designed Phase 2 to examine whether Frame 2 would produce higher enrollment if presented to students who were assigned to groups 1, 3 or 4 in Phase 1 and opted out into receiving extra information about the course (i.e., did not enroll into receiving additional resources). Thus, students opting out in Phase 1 (i.e., 120 students) received another opportunity to enroll. A total of 32 students answered the survey. When exposed to the negative frame with unchecked box, 93.7% (30 out of 32) opted into enrolling.

Study 2 Results

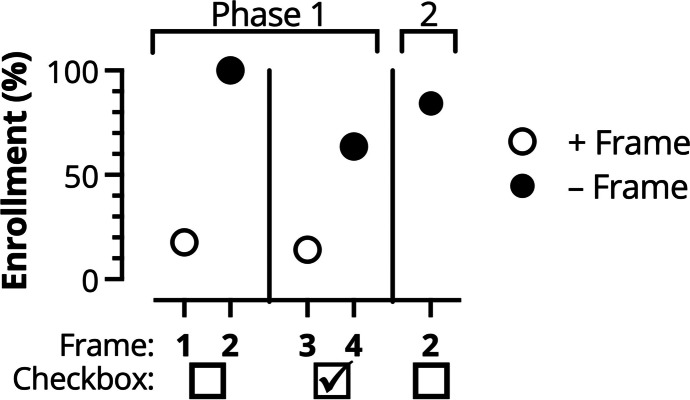

To evaluate the generality of our findings in Study 1, we conducted Study 2 using the same procedures in the following academic semester with different students using a different course platform (i.e., Canvas). Table 2 and Fig. 3 illustrate data for this experiment. A total of 65 students engaged the enrollment email in Phase 1. Seventeen students were randomly assigned by Qualtrics to receive Frame 1, 12 assigned to received Frame 2, 14 assigned to receive Frame 3, and 22 assigned to receive Frame 4. Again, Frame 2 (negative frame with unchecked box) produced the highest enrollment (100%, 12 out of 12 students enrolled). Again, Frame 4 (negative frame with checked box) produced the second highest enrollment (63.6%, 14 out of 52). Group 1 (positive frame with unchecked box) produced the third highest enrollment (17.6%, 3 out of 17). Frame 3 (positive frame with checked box) produced the lowest enrollment (14.2%, 2 out of 14). These data are displayed in Fig. 3. The x-axis depicts the box default options (checked or unchecked). Closed circles represent the use of negative frames and open squares represent the use of positive frames. The y-axis depicts the enrollment percentage. Negative frames produced higher percentage of enrollment compared to positive frames.

Fig. 3.

Enrollment rate per default and autoclitic frame in Study 2

During Phase 2, students receiving Frames 1, 3, and 4 who opted out in Phase 1 (i.e., 34 students) received another opportunity to enroll. A total of 19 students answered the survey. When provided with the negative frame with unchecked box, 84.2% (16 out of 19) opted into enrolling.

General Discussion

The primary aim of the current study was to evaluate effects of choice architecture as antecedent verbal stimuli on enrollment in a controlled setting. Specifically, Studies 1 and 2 examined effects of antecedent variable arrangements (i.e., presence of positive and negative framing and presence of checked or unchecked box) on choice behavior in undergraduate students. Further, we added a within-subject manipulation by conducting a second phase (Phase 2) where students failing to enroll into receiving additional resources in Phase 1 received the arrangement that produced higher enrollment in the first phase.

Results of both studies showed that negative frames with an unchecked box produced the highest enrollment, which replicate findings of previous research (Johnson et al., 2002). Overall, negative autoclitic frames (Frames 2 and 4) produced higher enrollment. Of note, Frame 2 (negative frame with an unchecked box) produced a higher enrollment than Frame 4 (negative frame with a checked box).

By having the box checked as a default, we hypothesized that Frame 3 could potentially nudge students into enrolling. In contrast, Frames 2 and 4 consisted of opt-out arrangements to enroll to receive extra activities for the course. In other words, by opting-out, we may view students as giving their explicit consent not to enroll for additional activities. In this way, by having the box checked as a default, Frame 4 could nudge students into not enrolling. Further, because Frame 2 contained negative form and the box was unchecked, it could nudge students into enrolling.

An additional manipulation was the introduction of an observing response. Students needed to check a box and confirm that they were students in the course—see Fig. 1. We wanted to increase the likelihood that students would attend to the instruction to opt-in or -out of receiving additional resources for the course. For all students, groups, and phases, this box was unchecked by default. We were concerned that checking the box could inadvertently increase the likelihood of students checking the following box (i.e., box that preceded a positive or negative frame to enroll) for Frames 1 and 2, where the box was unchecked by default. However, for both frames, a majority of students did not check the box in both studies.

Fig. 1.

Screenshot example of autoclitic framing and box default options. Note. Screen displayed for students assigned in Frame 3 (positive frame with box checked). The observing response requirement consisted of checking the first box (i.e., “I am a student enrolled…”). The white rectangle was inserted in this screenshot for publication only for confidentiality purposes; students could see the name of the course.

In these experiments, we conceptualized “nudges” (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008) as antecedent manipulations of choice framing (e.g., defaults) and how they exert stimulus control to prompt responses that may be tacted as more socially valid in terms of outcomes (e.g., studying more by having access to additional study materials can improve grades). We propose that certain types of framing (e.g., “Do NOT enroll…”) and boxes (e.g., checked box as a default) can have an autoclitic function by increasing the effectiveness of a verbal response that can influence listener responding. Analyzing nudges can be important because verbal responses to consent or dissent are usually influenced by antecedent stimulus control. In the context of choice architecture arrangements, nudges are typically deliberately arranged by an agent (e.g., a business organization) to influence the behavior of others (e.g., a consumer) in the agent’s desired direction (e.g., sign up to receive their services), based on what the agent interprets as the other’s best interest. However, it is possible to argue that “natural,” “unintentional,” or unplanned nudges exist and can increase the likelihood of certain verbal responses. As these antecedent arrangements are always present, it can be important for behavior analysts to proactively pay attention to these sources of control and evaluate potential effects when intervening.

Our studies did not analyze specifically how rule-governed behavior plays with college students. That is, we did not control previous behavioral history, nor did we arrange specific stimuli preceding or following rule-governed behavior. However, it is also important to consider the role of rule-governed behavior when arranging stimuli in nudge manipulations with undergraduate students. Behavior analysts have taken various approaches to conceptualizing and analyzing rule-governed behavior (e.g., Hayes & Hayes, 1989; Michael, 1984; Schlinger, 2008; Skinner, 1989). Rules can be characterized as being related to instructions given by experimenters or implied from the experimenters’ behavior, or can occur as a part of the participants’ own verbal repertoire and history (Michael, 1984). When we presented to students the choice to enroll in extra academic activities, it is possible that these arrangements—manipulated by the experiments, in the role of speakers—had the form and function of a rule by conditioning the behavior of students as listeners. In other words, the verbal stimuli, “Enroll me in extra academic activities,” could serve as discriminative stimuli to evoke and condition the behavior of students. Future studies could investigate or manipulate previous behavioral history with rule following, as well as collecting additional information on the decision-making process for choice.

Moreover, it is possible to interpret that there are many reasons why students follow norms and behave in ways expected or desired by experimenters. The choice to enroll in extra academic activities could be interpreted as the preferred choice from the experimenters’ perspective (i.e., “Engaging with extra activities is good!” as a rule), possibly influencing students to allocate their responding toward social positive consequences of approval. As Skinner analyzed (1989), rules work to the mutual advantage of those who maintain the contingencies and those who are affected by them. However, given that the positive frame, “Enroll me” was present in Groups 1 and 3 and evoked low responding for Group 1 and high for 3, rule-governed behavior alone cannot explain differentiated responding across groups using positive frames.

Although our studies did not initially conceptualize nudges arrangements and responses evoked by them as part of problem-solving processes, it is possible to interpret these arrangements as a problem. Behavior analysts have taken various approaches to conceptualizing and analyzing problem solving (e.g., Axe et al., 2018; Chastain et al., 2022; Donahoe & Palmer, 2004; Skinner, 1984). A problem exists when (a) the target response is in the individual’s repertoire, (b) the target response is scheduled for reinforcement, and (c) stimuli in the environment do not directly evoke the target response (Donahoe & Palmer, 2004). In this study, we can assume that checking or unchecking the box, as well as making choices, was in the students’ repertoire prior to the experiment. In addition, choosing or not to receive extra academic activities can be followed by consequences, socially mediated or not. Finally, the complex of discriminative stimuli (i.e., verbal stimuli, boxes, and frames) was not sufficient to evoke a response directly, as these stimuli could evoke competing responses. In our studies, we did not arrange immediate social consequences for choosing one alternative over another. Future studies could manipulate socially mediated contingencies and collect additional verbal responses related to problem solving—for example, requiring participants to talk aloud as a way of capturing potentially relevant responses (e.g., Chastain et al., 2022).

Manipulations, replications, and interpretations of nudge from a verbal operant perspective are potential contributions of our studies. Limitations include not having baseline data to compare our findings with data obtained in the antecedent manipulation phases. We also did not collect extensive demographic data from our students and had lower rates of responses in Study 2. Thus, although we replicated results from previous studies with different students and using different platforms, more studies are warranted.

In our studies, we aimed to evaluate the effects of different arrangements, interpreted through a verbal operant lens. We were surprised to replicate Johnson et al.’ (2002) results on having the negative framing with unchecked box producing the highest enrollment. Our hypothesis was that the positive frame with checked box would nudge more students to enroll into extra academic activities. At the time we conducted our studies, there was no behavior-analytic study on the effects of nudge and negative frames. Why did this specific antecedent arrangement produce higher enrollment?

One hypothesis could be related to the relative response effort of a verbal response. As operant behavior, verbal responses require an effort to be emitted. Previous research on operant behavior (see Friman & Poling, 1995; Wilder et al., 2021) shows that organisms will emit a low-effort response instead of a high-effort to obtain the same reinforcer. For Frame 2, keeping the box unchecked (i.e., keeping the default option and not checking the box) is a lower-effort response compared to checking a box (i.e., taking an action and checking the box). In addition, if a student was not effectively observing the screen and did not read what they were consenting to, the negative frame with unchecked box nudged students to enroll into receiving extra activities. Thus, we can interpret that nudges have an autoclitic function and allocate responding toward the option with relative lower response effort.

This response effort hypothesis can be corroborated when analyzing data for students receiving Frame 1 in both studies and Frame 3 in Study 1. Table 2 illustrates that point. Students assigned to Frame 1 could behave in two ways: either by checking the box (i.e., higher response effort) and enrolling or keeping the box unchecked (i.e., lower response effort).

However, the nudge to opt out of enrolling for students receiving Frame 4 (negative frame with checked box) was ineffective and most students unchecked the box and enrolled into receiving additional resources for the course in both studies. Thus, it is possible to hypothesize that there is something about negative frames in nudge arrangements. That is, the negative frame with unchecked box produced the highest enrollment, and the negative frame with checked box—designed to nudge an opt out response—influenced students to enroll as well. Although we cannot tact precisely what this is, we suggest that future studies could examine controlling variables and potential effects of negative and negation autoclitics with more detail.

For example, future experimental manipulations could investigate time spent when making a decision to consent or not to receive services, and potential effects of autoclitics and negative framing arrangements. When responding to a mand for consenting to something, effective listener responding must be in place. This response takes and requires time. A more well-informed decision or response may require even more time. Also, creating conditions for the listener to respond in a way that benefits themselves can be considered an ethical response. It is possible to infer that negative or negation autoclitics may evoke more overt and covert responses—and, consequently, require more time—to make a decision. When someone is told to do something and is presented with an option in a positive frame, this can exert clear stimulus control into making a decision. In contrast, when someone presents a choice in a negative frame, stimulus control can be more intricated and require more time for an informed decision. As discussed previously, choice architecture arrangements can be conceptualized as problem solving. We can interpret that negative frames, when compared to positive, are stimuli that will create even more barriers to the process of not directly evoking the target response (Donahoe & Palmer, 2004).

Despite the many demonstrated benefits and applications of nudging, their continued use does not come without some ethical concerns (Schmidt & Engelen, 2020). Among some groups, for example, nudging may be viewed as coercive in that individuals are influenced to make a particular decision without their knowledge or explicit consent (Selinger & Whyte, 2011). Nudging may also be considered patronizing—the public is too uneducated to make positive choice for themselves—thus infringing upon their personal freedoms (O’Neill, 2010). These concerns may be overstated, however, given the overwhelming presence of choice architecture among private entities and commercial advertising, which are viewed less controversially (Hausman & Welch, 2010). Nevertheless, concerns over the image of nudge-based intervention should be taken seriously, especially considering the benefits of policy-level programs as seen with the United Kingdom’s Behavioural Insights Team (Sunstein, 2014). On the other hand, arguments to support nudging include that choice architecture is inevitable—as there is no “neutral” way to frame options—and it can lead to cost-effective policies that can promote beneficial policy outcomes (Schmidt & Engelen, 2020). To further differentiate from coercion, researchers and policymakers should also be aware of what qualifies as a nudge. Described by Rachlin (2015), nudges manipulate means rather than ends, avoid punishment, present the freedom to choose an alternative, and present rewards or costs that are small relative to the consequences of the non-nudge alternative.

In an ideal situation, a person would effectively respond to verbal stimuli and make a choice that would benefit them, not necessarily the agent or person engaging in mands to consent. It would be “more ideal” and tacted as “more ethical” conduct because this would respect the person’s autonomy to make a choice, without deliberately nudging them to make a choice that would benefit the agent. It is important to consider, however, that unplanned nudges may already be in place; therefore, it could be relevant to understand all these environmental relations when presenting a choice to an individual.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception, design, material preparation, data collection, and analysis. The first author (Oda) wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors commented on subsequent versions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

De-identified datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB ID STUDY00149358) and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Axe JB, Phelan SH, Irwin CL. Empirical evaluations of Skinner's analysis of problem solving. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2018;35(1):39–56. doi: 10.1007/s40616-018-0103-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, J., Garber, A. M., & Goldhaber-Fiebert, J.D. (2015). Nudges in exercise commitment contracts: A randomized trial. Becker Friedman Institute for Research in Economics Working Paper. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2636165

- Cengher M, Ramazon NH, Strohmeier CW. Using extinction to increase behavior: Capitalizing on extinction-induced response variability to establish mands with autoclitic frames. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2020;36(1):102–114. doi: 10.1007/s40616-019-00118-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chastain, Luoma SM, Love SE, Miguel CF. The role of irrelevant, class-consistent, and class-inconsistent intraverbal training on the establishment of equivalence classes. The Psychological Record. 2022;72(3):383–405. doi: 10.1007/s40732-021-00492-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary V, Shunko M, Netessine S, Koo S. Nudging drivers to safety: Evidence from a field experiment. Management Science. 2022;68(6):4196–4214. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2021.4063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donahoe JW, Palmer DC. Learning and complex behavior. Ledgetop; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ensaff H. A nudge in the right direction: The role of food choice architecture in changing populations' diets. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2021;80(2):195–206. doi: 10.1017/S0029665120007983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher SA, Mandel DR. Risky-choice framing and rational decision-making. Philosophy Compass. 2021;16(8):e12763. doi: 10.1111/phc3.12763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friman PC, Poling A. Making life easier with effort: Basic findings and applied research on response effort. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28(4):583–590. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausman DM, Welch B. Debate: To nudge or not to nudge. Journal of Political Philosophy. 2010;18(1):123–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9760.2009.00351.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, editor. Rule-governed behavior: Cognition, contingencies, and instructional control. Plenum Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EJ, Bellman S, Lohse G. Defaults, framing and privacy: Why opting in-opting out. Marketing Letters. 2002;13(1):5–15. doi: 10.1023/A:1015044207315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda T, Lattal KA, García-Penagos A. An analysis of an autoclitic analogue in pigeons. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2014;30(2):89–99. doi: 10.1007/s40616-014-0019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodhi S, Greer RD. The speaker as listener. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1989;51(3):353–359. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1989.51-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke N, Greer RD, Singer-Dudek J, Keohane D. The emergence of autoclitic frames in atypically and typically developing children as a function of multiple exemplar instruction. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2011;27:141–156. doi: 10.1007/BF03393098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael J. Verbal behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1984;42(3):363–376. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1984.42-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan JM, Schultz PW, Cialdini RB, Goldstein NJ, Griskevicius V. Normative social influence is underdetected. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34(7):913–923. doi: 10.1177/0146167208316691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, B. (2010). A message to the illiberal nudge industry: Push off. Spikedhttps://www.spiked-online.com/2010/11/01/a-message-to-the-illiberal-nudge-industry-push-off/.

- Rachlin H. Choice architecture: A review of why nudge: The politics of libertarian paternalism. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2015;104(2):198–203. doi: 10.1002/jeab.163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed DD, Niileksela CR, Kaplan BA. Behavioral economics: A tutorial for behavior analysts in practice. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2013;6(1):34–54. doi: 10.1007/BF03391790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubaltelli E, Manicardi D, Orsini F, Mulatti C, Rossi R, Lotto L. How to nudge drivers to reduce speed: The case of the left-digit effect. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 2021;78:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2021.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sautter RA, Leblanc LA. Empirical applications of Skinner's analysis of verbal behavior with humans. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2006;22(1):35–48. doi: 10.1007/BF03393025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlinger HD. Conditioning the behavior of the listener. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2008;8(3):309–322. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt AT, Engelen B. The ethics of nudging: An overview. Philosophy Compass. 2020;15(4):1–13. doi: 10.1111/phc3.12658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selinger E, Whyte K. Is there a right way to nudge? The practice and ethics of choice architecture. Sociology Compass. 2011;5(10):923–935. doi: 10.1111/J.1751-9020.2011.00413.X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Skinner BF. An operant analysis of problem solving. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1984;7(4):583–613. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X00027412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. The behavior of the listener. In: Hayes SC, editor. Rule-governed behavior: Cognition, contingencies, and instructional control. Plenum; 1989. pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Speckman J, Greer RD, Rivera-Valdes C. Multiple exemplar instruction and the emergence of generative production of suffixes as autoclitic frames. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2012;28:83–99. doi: 10.1007/BF03393109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein CR. Nudging: A very short guide. Journal of Consumer Policy. 2014;37(4):583–588. doi: 10.1007/s10603-014-9273-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliabue M, Squatrito V, Presti G. Models of cognition and their applications in behavioral economics: A conceptual framework for nudging derived from behavior analysis and relational frame theory. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10:2418. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981;211(4481):453–458. doi: 10.1126/science.7455683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder DA, Ertel HM, Cymbal DJ. A review of recent research on the manipulation of response effort in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Modification. 2021;45(5):740–768. doi: 10.1177/2F0145445520908509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte SE, Caplan AL, Sadowski J. Nudge, nudge or shove, shove-the right way for nudges to increase the supply of donated cadaver organs. American Journal of Bioethics. 2012;12(2):32–39. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2011.634484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

De-identified datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.