Abstract

Behavior analysts are concerned with developing strong client–therapist relationships. One challenge to the development of such relationships may be a reliance on technical language that stakeholders find unpleasant. Previous research suggests that some behavior analysis terms evoke negative emotional responses. However, most relevant research was conducted with individuals from the general public and not individuals with a history of interaction with behavior analysts. The current study evaluated how parents of individuals with disabilities, who accessed behavior analytic services for their child, rated their emotional responses to 40 behavior analysis terms. We found that half of behavior analysis terms were rated as less pleasant than the majority of English words by parents. Furthermore, word emotion ratings by our stakeholder sample corresponded closely to norms obtained from the general public (Warriner et al. Behavior Research Methods, 45(4), 1191–1207, 2013). Our findings suggest that, while learning history may mediate some emotional responses to words, published word emotion data could be a useful guide to how stakeholders may respond to behavior analysis terminology. A need remains for additional studies examining word emotion responses that may be unique to particular sub-categories of stakeholders and evaluating how emotional responses impact the development of effective relationships.

Keywords: Technical terms, Emotional responses, Parents

In recent years, the field of applied behavior analysis (ABA) has increasingly recognized the importance of soft skills in the development of strong client–therapist relationships (e.g., Rohrer et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2019). Research in related disciplines provides support for this focus, as successful relationships have been shown to improve client outcomes (e.g., Beach et al. 2006; Heckman & Kautz, 2012). One behavior that can be important for the development of strong client–therapist relationships is the use of accessible language (Beck et al., 2002; LeBlanc et al., 2020; Rohrer et al., 2021). This behavior may stand in conflict with a long-standing tradition among applied behavior analysts of relying on technical terms that may be unfamiliar and off-putting to stakeholders (Friman, 2021; Lindsley, 1991; Taylor et al., 2019). While technical terms may be beneficial to effective communication between behavior analysts (Schlinger et al., 1991) and allow for conceptually systematic descriptions of behavior (Chiesa, 1994; Hineline, 1980), these terms may also evoke negative emotional responses that could interfere with relationship-building and make therapists seem less likeable (Critchfield et al., 2017a, 2017b; Marshall et al., 2023). Technical terminology has also been shown to detract from perceptions of a procedure's acceptability (Becirevic et al., 2016; McMahon et al., 2021; Rolider & Axelrod, 2005; cf. Normand & Donohue, 2022), recall of the steps of procedures (Banks et al., 2018), and implementation of procedures (Jarmolowicz et al., 2008; Marshall et al., 2023). Given these deleterious effects of behavior analysis terminology, practitioners have been urged to find ways to communicate that are a better match for the communication styles of stakeholders (Bailey, 1991; Neuman, 2018).

Although suggestions for productive communication strategies have been advanced (e.g., Friman, 2021; Lindsley, 1991), best practices for stakeholder communication remain to be identified. An example helps to illustrate why those best practices should be evidence based. Lindsley (1991), drawing on decades of experience working with stakeholders, devised a comprehensive method for identifying “plain English” substitutes that he thought would be better received than technical behavior analysis terms. Yet, some of Lindsley's replacement terms have been rated by individuals from the general public (e.g., Warriner et al., 2013) as unpleasant, similar to technical behavior analysis terms (Critchfield et al., 2017a). This shows that even Lindsley’s extensive clinical experience may be an insufficient guide for identifying terms that are perceived as pleasant or unpleasant by the general public. Hence, behavior analysts need scientifically validated methods for identifying technical terms that may be problematic for stakeholders, and for evaluating the appropriateness of replacement terms.

One established method for identifying emotional responses to words is to ask individuals to rate them on a scale ranging from happy to unhappy. For example, using this method, Warriner et al. (2013) presented general-population norms of emotion ratings for 13,195 English words (hereafter referred to as the “Warriner norms”). Such data appear to be informative to behavior analysts. For instance, Critchfield et al. (2017a) found that selected behavior analysis terms tended to be rated as unhappy in the Warriner norms, thereby providing a quantitative measure of effects that have been historically discussed in the field of ABA (e.g., Bailey, 1991; Lindsley, 1991). Yet, questions of generality can be raised about such data. Behavior analysts most commonly work with individuals with disabilities and their families (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, n.d.), a subset of the general population that, when compared to the general population on which the Warriner norms are based, may have unique histories that mediate their emotional responses to behavior analysis terms. For example, previous exposure to behavior analytic training might mitigate emotional responses to these terms. As verbal behavior can only be considered effective based on its impact on the listener (Skinner, 1957); behavior analysts’ language should be tailored to their specific audience. Thus, there is a need to evaluate if the emotional impact of technical behavior analytic terms found in previous studies would be observed when participants have these unique learning histories, including previous exposure to behavior analysis.

In the present study, we sought to evaluate the emotional responses to selected behavior analysis terms with parents of individuals with disabilities who have contacted our services. To accomplish this, we replicated methods from word-emotion studies (e.g., Warriner et al., 2013), to see how parents would respond to terms related to common behavior analysis procedures. We also conducted a test of generality to see how our results from parents compared to the Warriner norms. Differences between the two data sources would cast doubt on the suggestion, in previous studies, that general-population norms are a valuable predictor of how stakeholders respond to behavior analysis terms (e.g., Critchfield et al., 2017a). Close correspondence between the results from our parent participants and the Warriner norms would support the suggestion of previous researchers (e.g., Critchfield et al., 2017a) that many word-emotion responses may be relatively population independent and; therefore, publicly available data sets (e.g., Warriner norms) could be a useful tool in the identification of terms that parents of individuals with disabilities may also find unpleasant.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited via email messages sent by the first author and her colleagues. These recruiters determined on an individual basis whether to send emails to all potential participants at a particular organization (e.g., private clinics, schools for individuals with disabilities) or to only those individuals that they believed would be good candidates for the study. To be eligible to participate, individuals had to be a parent of a child with a disability who presently or previously received behavior analytic services. The recruitment message contained a link to a survey, administered in the Qualtrics platform, within which consent to participate could be granted and word emotion ratings made. Of the 87 parents who gave consent, 68 provided word emotion ratings and were thereby included in the study. These participants were recruited from 14 different behavior analytic organizations and were in varied locations in the United States, except for three who were from Dubai and one who was from Canada. As Table 1 shows, the participants were predominantly female, white, and well educated.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Demographic characteristics | All participants (68) % (n) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

|

26–30 years old 31–35 years old 36–40 years old 41–45 years old 46–50 years old 50+ years old |

2.9 (2) 7.4 (5) 13.2 (9) 26.5 (18) 17.65 (12) 32.4 (22) |

| Gender, % female | 86.8 (59) |

| Race/ Ethnicity | |

|

White Black or African American Asian Hispanic, Latinx, or Spanish Chose not to disclose Self-describe |

73.5 (50) 5.9 (4) 11.8 (8) 5.9 (4) 1.5 (1) 1.5 (1) |

| Education Level | |

|

High School Diploma Bachelor’s Degree Master’s Degree Doctoral Degree |

23.5 (16) 41.2 (28) 27.9 (19) 7.4 (5) |

| Age of Child | |

|

3–5 years old 6–11 years old 12–15 years old 16–18 years old 19+ years old No response |

17.6 (12) 39.7 (27) 16.2 (11) 17.6 (12) 1.5 (1) 7.4 (5) |

| Previous behavior analytic parent training, % yes | 36.8 (25) |

| Hours of previous parent training received (only those individuals who answered yes to parent training) | |

|

Less than 5 hours 5–10 hours 11+ hours |

12.0 (3) 32.0 (8) 56.0 (14) |

Materials

The first page of the Qualtrics survey was a consent form, and participants were required to select “Agree” to move through the rest of the survey. The survey included three sections: participant demographics, participant emotional ratings of technical terms, and participant knowledge of terms. The knowledge of terms section was not used in the present study, as participant pools differed and knowledge data were used in a separate study and analysis (see Marshall et al., 2023).

Initially, 88 terms were included in the survey. Terms were selected from protocols for common behavior analysis procedures used within multiple research and practice settings (e.g., discrete trial teaching, preference assessment) and the glossaries of behavior analysis texts (i.e., Cooper et al., 2007; Newman et al., 2003). We piloted the survey with all 88 terms and received consistent feedback that the response effort and task duration was too great. We narrowed the terms down to a list of 40, selecting only those terms that were relevant to skill acquisition.

In the emotional ratings section, each word was presented separately above an emotional rating scale shown as a virtual slider. The sliding scale ranged from 1 = Happy to 9 = Unhappy. This is the same scale employed in the Warriner et al. (2013) norming study, as well as in most previous studies of word emotion (e.g., Bradley & Lang, 1999). Participants were instructed to use the scale to rate how they felt about each term.

Analyses

A median was calculated from parents’ ratings to identify the emotional response to each of the technical terms for this participant group. Consistent with Warriner et al. (2013), the ratings were flipped for analysis such that a 1 represented Unhappy and a 9 represented Happy. Analyses focused on the median rating of each term to estimate how a “typical” parent of an individual with disabilities receiving behavior analysis services might respond to behavior analysis terms, rather than to characterize each parent’s ratings. Medians, specifically, were calculated as the sliding scale was considered an ordinal scale. In addition, for the purpose of comparing parents’ ratings to the Warriner norms, which took the form of mean ratings, the numerical mean was also calculated for each of the technical terms for this participant group (a side-by-side comparison of the median and mean for each term are presented in the appendix). A Pearson product-moment correlation was used to compare the parents’ median and mean ratings and a significant correlation was found (r = 0.9034, p < 0.0001). The significant correlation provides support for the use of means to compare with the Warriner norms, despite the ordinal scales used in both surveys. A Pearson product-moment correlation was also used to compare the mean ratings of the parents of individuals with disabilities (in the present study) and the general public (Warriner et al., 2013). Both correlations were conducted in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad, 2021).

Results

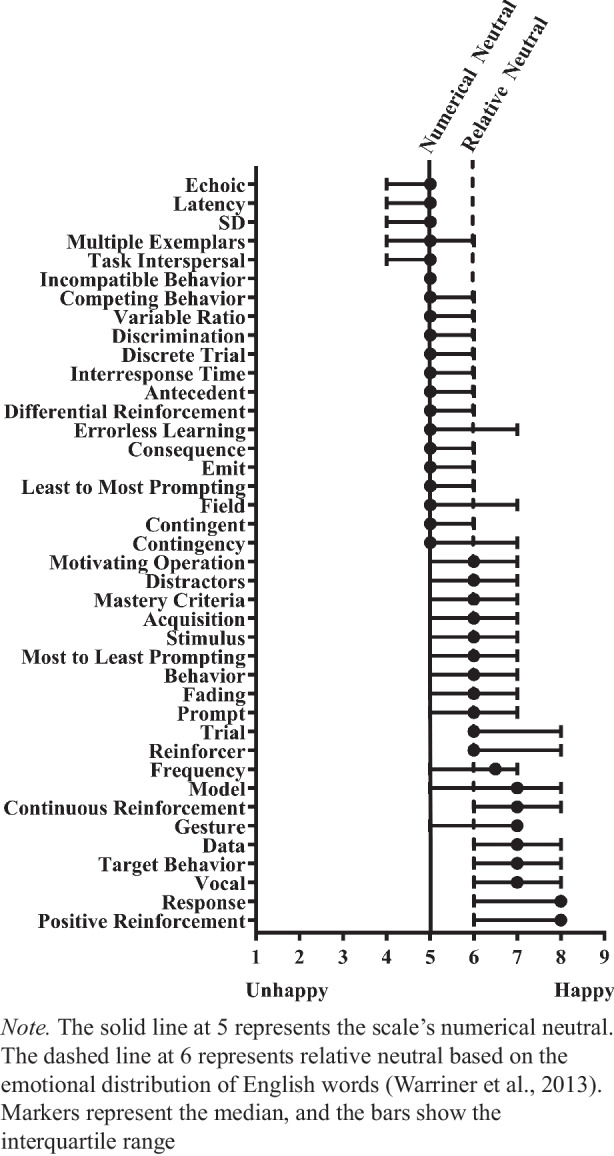

Figure 1 shows the median parent emotional rating of each of the 40 terms comparative to the rating scale’s neutral point (i.e., 5 on a 9-point scale) and the relative neutral point (i.e., 6 on a 9-point scale). All languages studied to date contain a majority of pleasant words (Dodds et al., 2015). For example, about two-thirds of English words are pleasant (Warriner et al., 2013); this translates to a 6 on a 9-point scale. In this context, “emotionally neutral” terms (i.e., 5) would actually fall into the unhappy half of the English language word-emotion distribution, and therefore could contribute to a perception of ABA and its practitioners as unpleasant. As such, we elected to represent both the neutral and relative neutral lines for comparison. Additionally, the quartile range for each term is shown by the bars extending from the marker.

Fig. 1.

Parent emotional ratings of behavior analytic terms

We found that parents of individuals with disabilities rated half of behavior analysis terms as unhappy in comparison to the majority of English words (i.e., 6). Twenty terms (50.0%) had median ratings of 5, falling on the scale’s numerical neutral and in the unhappy range relative to English language norms. Eleven terms (27.5%) had median ratings of 6, indicating that these terms were essentially neutral in comparison to other English words. Finally, nine terms (22.5%) had median ratings above 6, indicating that these terms were in the happy range relative to English language norms.

Of the 40 terms listed in Fig. 1, 17 were also included in the Warriner norms. We compared ratings from the two sources if they were either an exact match or were a different tense (e.g., fading and fade) or pluralization (e.g., prompts and prompt) of the same term. As can be seen in Table 2, most terms (11; 64%) had a difference of less than one point between the parent and general public ratings. In all but two cases (prompts and field), the parents’ ratings of behavior analytic terms were higher (i.e., more happy) than the general public’s ratings. Overall, ratings made by parents of individuals with disabilities and members of the general public were significantly correlated (r = 0.5771, p = 0.0153).

Table 2.

Difference between parent and general public ratings per term

| Term | Parents | General public | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior | 6.16 | 5.28 | 0.88 |

| Consequence | 5.48 | 3.86 | 1.62 |

| Contingency | 5.77 | 4.67 | 1.10 |

| Contingent | 5.73 | 4.85 | 0.88 |

| Frequency | 6.17 | 5.19 | 0.98 |

| Discrimination | 5.20 | 2.45 | 2.75 |

| Fading (W = fade) | 6.22 | 4.65 | 1.57 |

| Prompts (W = prompt) | 6.31 | 6.33 | -0.02 |

| Stimulus | 5.98 | 5.63 | 0.35 |

| Model | 6.40 | 6.38 | 0.02 |

| Acquisition | 5.92 | 5.00 | 0.92 |

| Trial | 6.47 | 3.28 | 3.19 |

| Field | 5.71 | 5.73 | -0.02 |

| Vocal | 6.84 | 5.81 | 1.03 |

| Emit | 5.51 | 4.81 | 0.70 |

| Response | 6.91 | 5.95 | 0.96 |

| Gesture | 6.52 | 5.75 | 0.77 |

Note. General public ratings were retrieved from Warriner et al. (2013)

Discussion

The present results demonstrate two main findings about parents’ emotional responses to behavior analysis terms. First, we found that parents of individuals with disabilities with a history of exposure to behavior analysis identified half of behavior analysis terms as more unhappy than the majority of English language terms. Although our modest sample of parents (N = 68) may not adequately represent the entire population of parents of individuals with disabilities, the present ratings came from more than three times as many individuals as the Warriner norms (18–20 individuals per word), which lends some degree of confidence to the results. The present findings are important because previous studies have relied on general population norms (e.g., Critchfield et al., 2017a) despite uncertainty about the generality of these norms to the stakeholders that applied behavior analysts serve. The unhappy ratings from parents magnify concerns that technical terminology can be detrimental to the relationship-building that has been asserted to be necessary for the dissemination of ABA (e.g., Friman, 2021; Lindsley, 1991).

The study participants were a convenience sample recruited by behavior analysts through a variety of methods. These procedures could have led to a potential sampling bias, as individuals who were recruited and participated may have had specific characteristics (e.g., an interest in learning more about applied behavior analysis) that could differentiate them from the general public and other parents of individuals with disabilities. An additional procedural limitation of the current study was the presentation of terms in a consistent order. Future researchers should ensure word order is randomized to avoid potential carryover effects.

The parents included in this study all had previous experience with behavior analysis, as inclusion criteria required that they have a child with disabilities who had previously or currently received behavior analytic services. Over a quarter of the participants reported receiving previous parent training in behavior analysis. It is possible that parents’ previous exposure to behavior analysis could have been correlated with their relatively more pleasant ratings compared to the Warriner norms.

Empirical evaluation is needed to evaluate whether providing people with a learning history with technical behavior analytic terms may make those terms less emotionally arousing. Importantly, and relatedly, there is a need to empirically evaluate if more positive responses to technical terms improve collaborative relationships. If this is the case, then understanding the specific parameters of such effects will be crucial to supporting behavior analysts with using exposure to behavior analytic terminology to effectively change emotional responses. For example, behavior analysts could be coached to engage in autoclitic behavior (e.g., presenting technical terms within the frame of everyday terms) that may reduce emotional responses to these terms. In addition, future research should strive to understand the mechanisms through which emotional responses to behavior analysis terms might change as a result of exposure. It may be particularly important to understand the impact of exposure for technical terms that appear to have utility (e.g., there is a dearth of technically precise alternatives, or the length and complexity of alternative explanations is problematic [Hineline, 1980]).

Second, we found close correspondence, at the level of individual terms, between word emotion ratings of parents of individuals with disabilities (in the present study) and members of the general public (Warriner et al., 2013). This matters because, in a quest for constructive communication, practicing behavior analysts are unlikely to have time to conduct a custom evaluation of how each parent they work with responds to technical terms. Similarly, stakeholders are unlikely to have time (or enthusiasm) for completing extensive surveys that would reveal their emotional responses to terms. A far more efficient approach is to consult publicly available data sources (whether representing the general public or ABA stakeholders specifically) in order to avoid terms that may be perceived as emotionally unpleasant and to emphasize those that may be perceived as emotionally pleasant. This approach both saves time and effort, and is likely to be more effective than simply guessing about how behavior analysis terms will be received (e.g., Critchfield et al., 2017a).

However, some caution is suggested in interpreting the previous claim. There were a minority of cases in which parents and members of the general public evaluated the same term substantially differently (e.g., trial was rated at 6.47 by parents and 3.28 by the general public, and discrimination was rated at 5.20 by parents and 2.45 by the general public). Given the limited research into word emotion as it applies to the language of behavior analysis, it is unknown how often and for whom these discrepancies might occur.

Future studies should clarify the impact of a broader range of behavior analysis terms on a broader range of audiences. This includes taking steps to assure that stakeholder samples incorporate a full range of demographic diversity. While our sample, predominantly female, well educated, and white, broadly parallels what has been reported in many previous ABA studies (e.g., Jones, et al., 2020), there is an acute need to find out more about the communication needs of more varied consumers (Critchfield & Doepke, 2018; Pritchett et al., 2021). Currently, we do not know which, if any, demographic variables may predict differential stakeholder ratings of technical terminology. Also unclear is the extent to which people may differentially rate technical terms when presented in isolation (as per the present study and Warriner et al., 2013) versus embedded in a naturalistic communication context (e.g., sentences, instructions, stories). While this will be important, particularly in the context of instructions or manuals that provide everyday definitions in combination with behavior analysis technical terms (e.g., Buchanan & Weiss, 2010), previous research suggests that looking at terms in isolation remains valuable. For instance, Reagan et al. (2017) found that the emotional sentiment of a connected text corresponded with the emotional rating of the text calculated from the individual words within it (e.g., calculations based on single word emotion ratings were in the unhappy range for negative movie reviews).

Most importantly, future studies should evaluate if negative emotional responses to technical terms are correlated with other behaviors that are detrimental to client–therapist relationships. For example, when a therapist provides a parent with an intervention plan heavily laden with unpleasant jargon, is the parent less likely to implement the procedure, less likely to contact the therapist with questions, or less likely to continue using the therapists’ services? On the other hand, would instructions containing pleasant everyday terms increase the likelihood of the parent developing a collaborative relationship with the therapist and seeking their ongoing services? Client–therapist relationships are complex; consequently, isolating variables, such as technical terms, can be difficult. However, future researchers should establish methods for evaluating the impact of emotionally unpleasant terms when presented within the context of novel and ongoing professional relations to better understand their influence on the development and maintenance of effective relationships.

A great deal of research is still needed to define evidence-based communication practices that support the development of effective relationships. Despite this, the present study suggests that there is potential value in practitioners referencing publicly available data sets to identify terms that they may benefit from avoiding when communicating with stakeholders. Professors and supervisors training future and early career behavior analysts should highlight terms that may evoke problematic responses and support their students and supervisees in using the available data sets to identify effective replacements. Specifically, terms that fall below the rating of neutral on the Warriner norms should be avoided while terms that are rated as above the neutral scoring can be prioritized in interactions with parents of individuals with disabilities.

One specific method for identifying problematic terms and emotionally pleasant replacement terms is outlined here as an example of the steps that practitioners might take to improve their communications with stakeholders.

Identify a term that is needed for use in instructions for a behavioral procedure and was rated below neutral in a publicly available dataset. For example, the term multiple exemplars might be used when the clinician requests that the parents use multiple exemplars to teach the concept of unsafe.

Identify a replacement term for the technical term. Many methods can be used to identify potential replacement terms, including the use of dictionaries or behavior analysis texts (e.g., Buchanan & Weiss, 2010; Newman et al., 2003). Critchfield (2017) suggested the use of Visuwords (an online tool showing words that have semantic relations with a searched word; https://visuwords.com/) to detect potential problematic associations with our technical terminology. However, this tool can also be useful for identifying synonymous or similar terms that are less emotionally unpleasant than technical terms. Following our example, a search for exemplar in Visuwords supplied the following potential replacement terms, model and example.

Evaluate replacement terms using normative emotional data sets. A review of the Warriner norms showed that example was rated as 4.9 and model was rated as 6.38. As such, the behavior analyst might ask the parent to use multiple models of unsafe activities and items to teach the concept of unsafe.

This suggested process is not without limitations. First, identifying replacement terms may not always be easy. For example, a search in Visuwords for the most unhappy term in the present study, echoic, provided terms (e.g., imitative, echolike, reflected) that are not synonymous with the behavior analytic meaning of the term. Nevertheless, similar terms could be identified by behavior analysts based on their personal knowledge (e.g., imitate or copy) or additional resources (e.g., Newman et al., 2003; repeat), and evaluated using available data sets (e.g., 5.44, 5.22, and 4.64 on the Warriner norms, respectively). Second, this process may initially be time consuming. However, as behavior analysts develop a vocabulary of replacement terms and use these successfully in their interactions with stakeholders, the use of these terms would be maintained and the need to complete ongoing searches of the Warriner norms would decrease. Ultimately, the time spent upfront may be quickly deemed worthwhile if it leads to improved communication with stakeholders and aids in the development of strong client–therapist relationships. As stated above, it will be essential to evaluate if changes in the use of unpleasant technical terms result in positive changes to relationships with clients and stakeholders.

It is possible such lengthy processes could be avoided in the future if the field shifted training and supervision models to incorporate routine preparation for using everyday replacement terms. If students and new practitioners were evaluated both on their technical precision and their ability to translate technical ideas into layman terms, these skills could be developed to fluency. Junior practitioners could enter clinical practice with an established skillset of speaking in an accessible manner, potentially leading to less observed challenges in client–therapist relationships.

Author’s Note

Kimberly Marshall is now at the College of Education, University of Oregon.

Thank you to Drs. David Palmer and Justin Leaf for their review of previous versions of the manuscript.

This study was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Applied Behavior Analysis at Endicott College by the first author.

Appendix

| Median | Mean | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive reinforcement | 8 | 7.15 |

| Response | 8 | 6.91 |

| Vocal | 7 | 6.84 |

| Target behavior | 7 | 6.80 |

| Data | 7 | 6.76 |

| Gesture | 7 | 6.52 |

| Continuous reinforcement | 7 | 6.46 |

| Model | 7 | 6.40 |

| Frequency | 6.5 | 6.17 |

| Reinforcer | 6 | 6.56 |

| Trial | 6 | 6.47 |

| Prompt | 6 | 6.31 |

| Fading | 6 | 6.22 |

| Behavior | 6 | 6.16 |

| Most to least prompting | 6 | 6.00 |

| Stimulus | 6 | 5.98 |

| Acquisition | 6 | 5.92 |

| Mastery criteria | 6 | 5.88 |

| Distractors | 6 | 5.86 |

| Motivating operation | 6 | 5.73 |

| Contingency | 5 | 5.77 |

| Contingent | 5 | 5.73 |

| Field | 5 | 5.71 |

| Least to most prompting | 5 | 5.55 |

| Emit | 5 | 5.51 |

| Consequence | 5 | 5.48 |

| Errorless learning | 5 | 5.43 |

| Differential reinforcement | 5 | 5.38 |

| Antecedent | 5 | 5.29 |

| Interresponse time | 5 | 5.26 |

| Discrete trial | 5 | 5.24 |

| Discrimination | 5 | 5.20 |

| Variable ratio | 5 | 5.18 |

| Competing behavior | 5 | 5.14 |

| Incompatible behavior | 5 | 5.10 |

| Task interspersal | 5 | 4.98 |

| Multiple exemplars | 5 | 4.98 |

| SD | 5 | 4.84 |

| Latency | 5 | 4.83 |

| Echoic | 5 | 4.65 |

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

This study was approved by the Endicott College Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bailey JS. Marketing behavior analysis requires different talk. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24(3):445–448. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks BM, Shriver MD, Chadwell MR, Allen KD. An examination of behavioral treatment wording on acceptability and understanding. Behavioral Interventions. 2018;33(3):260–270. doi: 10.1002/bin.1521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beach MC, Keruly J, Moore RD. Is the quality of the patient-provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(6):661–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becirevic A, Critchfield TS, Reed DD. On the social acceptability of behavior-analytic terms: Crowdsourced comparisons of lay and technical language. The Behavior Analyst. 2016;39(2):305–317. doi: 10.1007/s40614-016-0067-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: A systematic review. The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2002;15(1):25–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (n.d). BACB certificant data. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/BACB-certificant-data

- Bradley, M. M. & Lang, P. J. (1999). Affective norms for English words (ANEW): Instruction manual and affective ratings. Technical report C-1, The Center for Research in Psychophysiology, 30(1), 25–36.

- Buchanan SM, Weiss MJ. Applied behavior analysis and autism: An introduction. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa M. Radical behaviorism: The philosophy and the science. Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL, editors. Applied behavior analysis. 2. Merrill Prentice Hall; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield TS. Visuwords®: A handy online tool for estimating what nonexperts may think when hearing behavior analysis jargon. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2017;10(3):318–322. doi: 10.1007/s40617-017-0173-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield TS, Doepke KJ, Epting LK, Becirevic A, Reed DD, Fienup DM, Kremsreiter JL, Ecott CL. Normative emotional responses to behavior analysis jargon or how not to use words to win friends and influence people. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2017;10(2):97–106. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0161-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield TS, Becirevic A, Reed DD. On the social validity of behavior-analytic communication: A call for research and description of one method. Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2017;33(1):1–23. doi: 10.1007/s40616-017-0077-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield TS, Doepke KJ. Emotional overtones of behavior analysis terms in English and five other languages. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;11(2):97–105. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-0222-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds PS, et al. Human language reveals a universal positivity bias. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 2015;112:2389–2394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411678112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friman, P. C. (2021). There is no such thing as a bad boy: The circumstances view of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1–18. 10.1002/jaba.816 [DOI] [PubMed]

- GraphPad. (2021). GraphPad Prism (Version 9.1.0). GraphPad Software. www.graphpad.com

- Heckman JJ, Kautz T. Hard evidence on soft skills. Labour Economics. 2012;19(4):451–464. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hineline PN. The language of behavior analysis: Its community, its functions, and its limitations. Behaviorism. 1980;8(1):67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Jarmolowicz, D. P., Kahng, S., Ingvarsson, E. T., Goysovich, R., Heggemeyer, R., & Gregory, M. K. (2008). Effects of conversational versus technical language on treatment preference and integrity. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 46(3), 190–199. 10.1352/2008.46:190–199. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jones, S. H., St. Peter, C. C., & Ruckle, M. M. (2020). Reporting of demographic variables in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53(3), 1304–1315. [DOI] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc LA, Taylor BA, Marchese NV. The training experiences of behavior analysts: Compassionate care and therapeutic relationships with caregivers. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2020;13(2):387–393. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00368-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley OR. From technical jargon to plain English for application. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24(3):449–458. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, K. B., Weiss, M. J., Critchfield, T. S., & Leaf, J. B. (2023). Effects of jargon on parent implementation of discrete trial teaching. Journal of Behavioral Education (in press).

- McMahon, M. X., Feldberg, Z. R., & Ardoin, S. P. (2021). Behavior analysis goes to school: Teacher acceptability of behavior-analytic language in behavioral consultation. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1–10. 10.1007/s40617-020-00508-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Neuman P. Vernacular selection: What to say and when to say it. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2018;34(1–2):62–78. doi: 10.1007/s40616-018-0097-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman B, Reeve KF, Reeve SA, Ryan CS. Behaviorspeak: A glossary of terms in applied behavior analysis. Dove and Orca; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Normand MP, Donohue HE. Behavior analytic jargon does not seem to influence treatment acceptability ratings. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2022;55(4):1294–1305. doi: 10.1002/jaba.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett, M., Ala’i-Rosales, S., Cruz, A. R., & Cihon, T. M. (2021). Social justice is the spirit and aim of an applied science of human behavior: Moving from colonial to participatory research practices. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1–19. 10.1007/s40617-021-00591-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Reagan AJ, Danforth CM, Tivnan B, Williams JR, Dodds PS. Sentiment analysis methods for understanding large-scale texts: a case for using continuum-scored words and word shift graphs. EPJ Data Science. 2017;6:1–21. doi: 10.1140/epjds/s13688-017-0121-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rolider A, Axelrod S. The effects of “behavior speak” on public attitudes toward behavioral interventions: A cross-cultural argument for using conversational language to describe behavioral interventions to the general public. In: Heward WL, Heron TE, Neef NA, Peterson SM, Sainato DM, Cartedge G, Gardner R, Peterson LD, Hersh SB, Dardig JC, editors. Focus on behavior analysis in education: Achievement, challenges, and opportunities. Pearson Education; 2005. pp. 283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer JL, Marshall KB, Suzio C, Weiss MJ. Soft skills: The case for compassionate approaches or how behavior analysis keeps finding its heart. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2021;14(4):1135–1143. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00563-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlinger HD, Blakely E, Fillhard J, Poling A. Defining terms in behavior analysis: Reinforcer and discriminative stimulus. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1991;9:153–161. doi: 10.1007/BF03392869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Taylor BA, LeBlanc LA, Nosik MR. Compassionate care in behavior analytic treatment: Can outcomes be enhanced by attending to relationships with caregivers? Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(3):654–666. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00289-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warriner AB, Kuperman V, Brysbaert M. Norms of valence, arousal, and dominance for 13,915 English lemmas. Behavior Research Methods. 2013;45(4):1191–1207. doi: 10.3758/s13428-012-0314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.