It is well established that certain phenotypes of uveitis such as choroidal tuberculomas (Fig. 1A) and choroidal tubercles are due to active tuberculosis (TB) and require treatment with anti-tubercular therapy (ATT) [1]. In the presence of recent evidence of active systemic tuberculosis, other uveitic entities, such as granulomatous uveitis, retinal vasculitis and serpiginous like choroiditis are also treated with ATT.

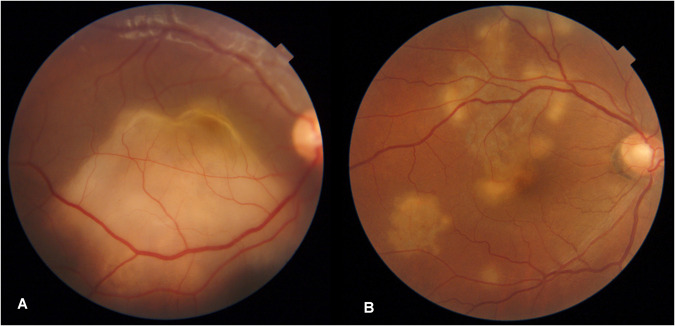

Fig. 1. Fundus photographs of definite and presumed ocular tuberculosis.

A A single large choroidal lesion with overlying exudative retinal detachment suggestive of choroidal tuberculoma. B Multifocal choroiditis lesions with geographic shape and active borders are suggestive of serpiginous like choroiditis. While choroidal tuberculoma responds to anti-tubercular therapy alone, serpiginous like choroiditis is treated with systemic steroids and immunosuppressive agents without ATT.

However, conditions such as syphilis, sarcoidosis and autoimmune disorders may be associated with similar presentations of uveitis [2]. Majority of these cases may just be an idiopathic ocular pathology. Thus, it would be inappropriate to ascribe these phenotypes of uveitis to tuberculosis in the absence of definite systemic evidence of tuberculosis.

Some recent studies suggest TB as the aetiology of isolated retinal vasculitis and serpiginous like choroiditis in the absence of systemic evidence of TB, based on tests for latent TB such as Tuberculin Skin Test (TST)/Interferon Gamma Release Assays (IGRA) and detection of tubercular DNA from ocular fluids [3, 4]. An undue emphasis has been laid on TST /IGRA as evidence of TB disease, while these tests are only a marker of Latent Tuberculosis infection (LTBI). Few studies suggest clinical signs to differentiate idiopathic form of vasculitis/serpiginous like choroiditis from the tubercular variety [3, 5]. In the Collaborative Ocular Tuberculosis Study, the authors recommend starting ATT even if only TST or IGRA is positive [6]. In India, with a high endemicity of TB, LTBI is reported in 31.4% population [7] and thus the validity of this recommendation needs to be critically addressed. WHO clearly mandates against the use of tests for LTBI for diagnosis of tuberculosis [8]. Detection of TB DNA needs careful interpretation in the absence of clinical signs and symptoms [9, 10].

Uveitis phenotypes such as choroidal tubercles respond to ATT alone. Most of the larger choroidal tuberculomas respond to ATT alone as well. In some cases, systemic steroids are added as adjunctive therapy empirically to hasten the resolution or reduce excessive exudation from the tuberculoma which may lead to an exudative retinal detachment. If a case of choroidal tuberculoma is treated only with steroids, it is bound to worsen. Cases of systemic tuberculosis in which granulomatous uveitis or vasculitis or serpiginous like choroiditis is detected are treated with local/systemic steroids in addition to ATT as the ocular manifestation may only be inflammatory in nature.

Idiopathic granulomatous uveitis/vasculitis and serpiginous choroiditis (Fig. 1B) respond well to steroids alone. Some studies labelled these uveitis phenotypes as tubercular, advocated treating these cases not with ATT alone but with a combination of ATT and systemic steroids (+/− immunosuppressive agents) and considered the response to therapy as confirmation of tuberculosis [3, 11]. Addition of steroids to the treatment is a major confounding factor. With this treatment protocol it can never be established whether it was tuberculosis or an immune process responsible for the vasculitis or serpiginous choroiditis. The rationale given for adding steroids and immunosuppressants to ATT is Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction [12]. Such a reaction should not occur invariably in most treated patients. Similarly, it is not prudent to justify steroids for fear of an immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) as this syndrome is quite rare in otherwise immunocompetent individuals [13]. Literature also suggests that cases of serpiginous choroiditis progress despite ATT and such cases need to be given additional immunosuppression for resolution of the uveitis [14].

Another argument given by some authors is that adding ATT may reduce recurrences [15]. They propose that the Uveitis may be an immune response to the tubercule bacilli latent somewhere in the body or perhaps in the retinal pigment epithelium. For the sake of argument even if it is accepted that there is a link between latent tuberculosis and some forms of uveitis due to an immune process, the treatment offered must not be full ATT. The therapy if at all for latent tubercular infection (LTBI) is tuberculosis preventive treatment (TPT) as per WHO [8]. Well defined consolidated guidelines have been published by WHO on who all merit TPT and most of the uveitis patients under consideration don’t fall in that category [8].

The studies on use of ATT in retinal vasculitis and serpiginous choroiditis don’t talk of side-effects of ATT. This is something which cannot be neglected as complications of ATT such as hepatitis are not uncommon. Ignoring or failing to highlight possible complications of therapy is startling and another reason for our opposition to misuse of ATT.

Defining uveitis phenotypes as tubercular based on the weak evidence mentioned above and then using this definition as the comprehensive reference standard for ocular tuberculosis can be catastrophic. If the comprehensive standard definition itself is questionable then sensitivity and specificity of diagnosing ocular tuberculosis of all subsequent studies based on this premise are incorrect. It would lead to an overdiagnosis of ocular tuberculosis and significant misuse of ATT which can further increase the problem of drug resistance.

There is need for research on this subject using an array of molecular diagnostic markers not just from the ocular fluids but also a study of markers of host response to correctly identify the subset of case of uveitis which stem from tuberculosis. There is an earnest need for prudence in diagnosis and treatment of Ocular Tuberculosis.

Author contributions

RC, UBS, DV and PV all contributed in conceptualizing, critically analysing existing data on the subject, writing and editing the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Helm CJ, Holland GN. Ocular tuberculosis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1993;38:229–56. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(93)90076-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutchinson J. Serpiginous choroiditis in scrofulous subjects: choroidal lupus. Arch Surg (Lond) 1900;11:126–35. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaza H, Tyagi M, Pathengay A, Basu S. Clinical predictors of tubercular retinal vasculitis in a high-endemic country. Retina. 2021;41:438–44. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bansal R, Sharma K, Gupta A, Sharma A, Singh MP, Gupta V, et al. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome in vitreous fluid of eyes with multifocal serpiginoid choroiditis. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:840–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nazari Khanamiri H, Rao NA. Serpiginous choroiditis and infectious multifocal serpiginoid choroiditis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58:203–32. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agrawal R, Testi I, Mahajan S, Yuen YS, Agarwal A, Kon OM, et al. Collaborative ocular tuberculosis study consensus guidelines on the management of tubercular uveitis-report 1: guidelines for initiating antitubercular therapy in tubercular choroiditis. Ophthalmology. 2021;128:266–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, National Institute for Research in Tuberculosis, Chennai, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi. National TB Prevalence Survey in India 2019–2021. Summary Report.

- 8.WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 1: Prevention. Tuberculosis preventive treatment. Geneva, World Health Organization. 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331525/9789240002906-eng.pdf. [PubMed]

- 9.WHO operational handbook on tuberculosis: module 3: diagnosis: rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection, 2021 update. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240030589 (accessed May, 2023).

- 10.Chawla R, Singh MK, Singh L, Shah P, Kashyap S, Azad S, et al. Tubercular DNA PCR of ocular fluids and blood in cases of presumed ocular tuberculosis: a pilot study. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2022;14:25158414221123522. doi: 10.1177/25158414221123522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bansal R, Gupta V. Tubercular serpiginous choroiditis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2022;12:37. doi: 10.1186/s12348-022-00312-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganesh SK, Abraham S, Sudharshan S. Paradoxical reactions in ocular tuberculosis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2019;9:19. doi: 10.1186/s12348-019-0183-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lanzafame M, Vento S. Tuberculosis-immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2016;3:6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta V, Bansal R, Gupta A. Continuous progression of tubercular serpiginous-like choroiditis after initiating antituberculosis treatment. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152:857–63.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bansal R, Gupta A, Gupta V, Dogra MR, Bambery P, Arora SK. Role of anti-tubercular therapy in uveitis with latent/manifest tuberculosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:772–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]