Abstract

Background

To evaluate vision 3 months after SmartSight lenticule extraction treatments.

Design

Case series.

Methods

This case series of patients were treated at Specialty Eye Hospital Svjetlost in Zagreb, Croatia. Sixty eyes of 31 patients consecutively treated with SmartSight lenticule extraction were assessed. The mean age of the patients was 33 ± 6 years (range 23–45 years) at the time of treatment with a mean spherical equivalent refraction of −5.10 ± 1.35 D and mean astigmatism of 0.46 ± 0.36 D. Monocular corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA), uncorrected distance visual acuity (UDVA) were assessed pre- and post-operatively. Ocular and corneal wavefront aberrations have been postoperatively compared to the preoperative baseline values. Changes in ocular wavefront refraction, as well as changes in keratometric readings are reported.

Results

At 3 months post-operatively, mean UDVA was 20/20 ± 2. Spherical equivalent showed a low myopic residual refraction of −0.37 ± 0.58 D with refractive astigmatism of 0.46 ± 0.26 D postoperatively. There was a slight improvement of 0.1 Snellen lines at 3-months follow-up. Compared to the preoperative status, ocular aberrations (at 6 mm diameter) did not change at 3 months follow-up; whereas corneal aberrations increased (+0.22 ± 0.21 µm for coma; +0.17 ± 0.19 µm for spherical aberration; and +0.32 ± 0.26 µm for HOA-RMS). The same correction was determined using changes in ocular wavefront refraction, as well as changes in keratometric readings.

Conclusion

Lenticule extraction after SmartSight is safe and efficacious in the first 3 months postoperatively. The post-operative outcomes indicate improvements in vision.

Subject terms: Refractive errors, Outcomes research

Introduction

Lenticule extraction is an established alternative for laser vision correction [1]. Lenticule extraction involves the use of an ultrashort pulse laser system to delineate the contour of a volume of tissue to be excised (providing for the refractive correction) along with a channel to access and extract the lenticule [2].

For years only one provider for the technology and technique was available (SMILE using Visumax by Carl Zeiss Meditec, Germany) [2]. More recently, alternatives have been established, including CLEAR using Z8 by Ziemer, Switzerland [3]; and SmartSight using ATOS by SCHWIND eye-tech-solutions, Germany [4].

The SCHWIND ATOS (used in the current work in the form of SmartSight treatments) works in the plasma-mediated ablation regime [5], slightly exceeding the threshold for laser-induced optical breakdown [6], but below the classic photodisruption regime [7]. It uses pulse energies below 100nJ, associated with repetition rates of up to 4 MHz, and an asymmetric scanning pattern [8]. For 100 nJ pulse energies, the spot spacing is >4 µm with a track spacing ~3 µm. The system includes a video-based eye registration (for both centration and cyclotorsion controls) from the diagnostic [9, 10]. The SmartSight profile includes a refractive progressive transition zone [11] (similar to the one used in the SCHWIND AMARIS [12]) tapering the lenticule towards the edge of the transition zone, without the need for a minimum-lenticule-thickness pedestal [13].

The main differences between SmartSight and SMILE include no minimum lenticule thickness potentially reducing the overall thickness of the lenticules; progressive refractive transition zone potentially reducing the epithelial remodeling; working from in to outside (centrifugally) i.e., the most important part (center of the treatment) goes first; low pulse energy concept (sub 100nJ) providing better resolution and lower corneal reactions; asymmetric spacing leading to more homogeneous cuts with lower pulse energies; overbending of the cap as protective measure against slight decentrations; Eye-Tracking guided centration incorporating the pupil offset with better positioning of the lenticule respect to the visual axis; cyclotorsion compensation with better positioning of the lenticule respect to the meridional orientation (astigmatism axis); low suction level (sub 300 mmHg) with low load onto the eye (sub 200 g) resulting in less stress to the cornea/eye; high repetition rate (in the MHz regime) offering potential for faster treatments or better resolution; and High Numerical Aperture and Quasi Telecentric Optics leading to the same cutting quality for the whole cornea.

In this work, we report the first European results of one of those new refractive lenticular extraction procedures—SmartSight by SCHWIND eye-tech-solutions.

Methods

Patients

This work evaluates a consecutive case series of patients treated by a single surgeon (MB), with SmartSight to correct myopia (with or without refractive astigmatism), at Svjetlost, Zagreb, Croatia. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was retrospective with anonymized data. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Ethics approval was not required due to the retrospective nature of the review chart. The purpose of this clinical research does not represent a clinical investigation. The medical device was used within its intended purpose without any additional invasive or patient-burdensome procedures used.

Preoperative examinations

All patients underwent a complete preoperative ophthalmologic examination to decide whether patients were eligible for SmartSight surgery using criteria normally adopted for refractive surgery [14]. Patients with history of ocular surgery, abnormal corneal topography, preoperative corneal thickness <480 µm or calculated residual stromal bed thickness <275 µm were excluded.

Examination included uncorrected distance visual acuity (UDVA), corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA), manifest and cycloplegic refraction, corneal tomography (Pentacam HRTM, Oculus Optikgeräte GmbH, Germany; and Sirius, CSO, Italy), corneal and ocular aberrometry (Peramis and MS-39, both CSO, Italy), tonometry (ICARE, Finland), slit lamp and dilated funduscopic examination. RMS; coma, trefoil, and spherical aberration were the three higher-order aberration values harvested during this evaluation. Visual acuities were evaluated using the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) charts.

The patients were asked to discontinue contact lens wear for up to four weeks, depending on the type of contact lenses, prior to the examination.

Surgical procedure

Both eyes were anesthetized with two drops of topical anesthetic (NovesineTM, OmniVision GmbH, Germany) instilled at two-minute intervals just before surgery. After standardized cleaning with 2.5% povidone-iodine and sterile draping, eyelid speculum was used to keep the eye open. SCHWIND ATOS femtosecond laser (SCHWIND eye-tech-solutions, Germany) was used for the SmartSight procedure. After the patient was positioned on the bed, the cone (disposable patient interface) was inserted, the patient’s eye was positioned under the cone and patient was instructed to fixate on the light target.

For the SmartSight procedure, the system works in the low-density plasma region [15], above the threshold for laser-induced optical breakdown [16], but below the photodisruption regime [17]. In this series pulse energies between 80 nJ and 100 nJ have been used with an asymmetric scanning pattern. The spot spacing ranged from 3.6 µm to 4.4 µm with a track spacing from 2.6 µm to 3.0 µm.

For centering the treatments, 50% of the distance from vertex to pupil center (as obtained from the Sirius tomographer; CSO) [18] has been used.

An eye-tracker-guided centration was used to proceed with docking of the eye to the system. A coaxial view through the cone of the patient interface, including static overlays of the target pupil position (yellow cross-hair) surrounded by two concentric hot zones (target hot zone of 200 µm radius, marked as a yellow circle; maximum permissible hot zone of 700 µm radius marked as a red circle) is displayed. The operator is instructed to overlap the pupil center (detected by a video-based Eye-Tracker, green cross) to the target pupil position (within the yellow circle) (Supplemental Fig. 1). Suction was then applied at levels between 290 mmHg and 330 mmHg, and it was confirmed that the pupil remained within the yellow circle (target hot zone), or at least within the red circle (maximum permissible hot zone); otherwise a new docking was attempted. Further to that, the last valid videoframe of the eye-tracker has been used for cyclotorsional alignment to the diagnostic image [19]. The treatment was applied and the laser ablation was initiated after suction.

For all cases, the programmed treatment consisted of cycloplegic spherical correction with manifest astigmatic power and axis. Caps were 125–135 µm thick with a superotemporal incision at 135° and 65° with an entry angle of 110° and width of 3.0 mm. The optical zone ranged from 6.5 to 7.0 mm, depending on the scotopic pupil size and attempted correction, surrounded by a refractive progressive transition zone of up to 0.8 mm (depending on the corneal curvature gradient otherwise induced by the correction [20]) tapering the lenticule to zero thickness, without the need of a minimum-lenticule-thickness pedestal [21]. Once the lenticule creation was completed, suction was released automatically. A thin blunt spatula was inserted through the incision to first identify two sides of the lenticule and then separate the lenticule (first the anterior and then the posterior surface) from the stroma and extracted it through the incision. After extraction 2.0 ml of Balanced Salt Solution was injected in the pocket [22] and cornea was gently massaged (ironed) in straight movements toward the incision in order to spread the cap evenly and potentially decrease Bowman’s wrinkles [23]. In the end, the remaining tissue was checked for any residual material or tears.

Treatment parameters are summarized in Supplemental Table 1.

Postoperative evaluation

Postoperative therapy included topical antibiotic and steroid drops (TobradexTM, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, USA) four times daily for two weeks, and artificial tears (BlinkTM, Johnson & Johnson Surgical Vision Inc, USA) 6–8 times daily for one month.

Patients were reviewed on 1st day, 1st week 1 and 3 months postoperatively. A full ophthalmologic examination was performed on all the patients. CDVA and UDVA were evaluated using ETDRS charts assessed with a phoropter.

Topography and aberrometry, providing corneal and ocular aberrometry were reported for a 6 mm diameter, measured with the MS-39 (CSO, Italy) and SCHWIND PERAMIS (CSO, Italy), respectively. Root mean square (RMS) higher-order aberrations, coma, trefoil, and spherical aberrations were reported.

The refractive correction has been assessed in three different ways: manifest refraction was used, aberrometric refraction (objective refraction derived from the ocular wavefront measurements, as a high-resolution autorefractor), and changes in keratometric readings at 3-mm were also evaluated.

The MS-39 used to acquire tomographic and topographic measurements is a spectral domain OCT specifically developed to measure the anterior segment of the eye [24], whereas the SCHWIND PERAMIS used to acquire ocular wavefront measurements is a pyramidal wavefront sensor providing over 40,000 measurement points, representing a lateral resolution of ~41 µm [25].

Statistical analysis

To determine the sample size, the following values were taken from the patient cohort in a recently published study: the standard deviation (SD) of the postoperative refraction (0.31 diopter [D]) and the SD of the interocular differences of postoperative refraction (0.39 D) in bilaterally treated patients. To detect a difference in refraction barely reaching detectability (clinical relevance), the level of detection was set to 3/16 D (0.1875 D). The required sample size for alpha = .05 and 80% statistical power was 42 and 33 eyes, respectively. A total of 31 patients (60 eyes) were identified.

The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Analysis of variance and t-tests were performed on normally distributed data and Friedman tests and post-hoc Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests when the data was not normally distributed. UDVA and CDVA were analyzed in logMAR but reported in equivalent Snellen fractions.

Results

All patients completed the 3-month follow-up. The cohort included 31 patients (60 eyes) and all eyes were included for analysis. The mean age of the patients was 33 ± 6 years (range 23–45 years) at the time of treatment with a mean spherical equivalent refraction of −5.10 ± 1.35 D and mean astigmatism of 0.46 ± 0.36 D. A summary of the preoperative and postoperative demographics is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of preoperative and postoperative outcomes.

| Parameter | Value Preop | StdDev | min | max | Value Postop | StdDev | min | max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of treatments | 60 eyes / 31 patients | |||||||

| Female:Male | 17:14 | |||||||

| Age (years) | 33 | 6 | 23 | 45 | ||||

| MRSEq (D) | −5.15 | 1.27 | −8 | −3.25 | −0.01 | 0.11 | −0.5 | 0.5 |

| M. Astigmatism (D) | 0.46 | 0.36 | 0 | 2 | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0 | 1 |

| CDVA (Snellen) | 20/21 | 2 | 20/40 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 1 | 20/22 | 20/20 |

| UDVA (Snellen) | 20/400 | 6 | 20/2000 | 20/126 | 20/20 | 2 | 20/32 | 20/16 |

| K-readings (D) | 44.1 | 1.4 | 41.1 | 48.0 | 39.8 | 1.7 | 36.3 | 44.8 |

| Corneal HOA (µm) | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.63 | 0.27 | 0.3 | 1.8 |

| Corneal Coma (µm) | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 1.31 |

| Corneal SphAb (µm) | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 1.07 |

| Ocular HOA (µm) | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.75 | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.77 |

| Ocular C[3,−1] | 0.02 | 0.15 | −0.21 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.23 | −0.60 | 0.53 |

| Ocular C[3,+1] | 0.01 | 0.07 | −0.26 | 0.27 | −0.01 | 0.14 | −0.34 | 0.35 |

| Ocular C[4,0] | 0.09 | 0.11 | −0.14 | 0.41 | 0.11 | 0.18 | −0.23 | 0.52 |

Standard graphs for reporting astigmatism outcomes of refractive surgery

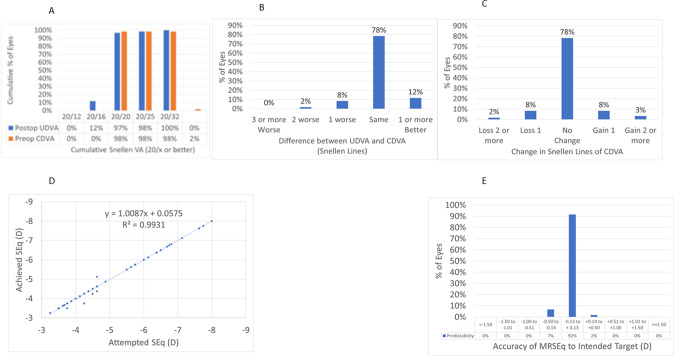

At 3 M, 97% of the eyes reached an UDVA of 20/20 or better (Fig. 1A), for 98% of the eyes UDVA remained within one line of preoperative CDVA (Fig. 1B), 2% of the eyes (1 eye) lost 2 lines of CDVA (Fig. 1C). At 3 M, the scattergram showed an excellent refractive correction of the SEQ (Fig. 1D), with all eyes within 0.5D from target (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1. Standard graphs for reporting outcomes in laser vision correction.

A Cummulative Visual acuity. B Difference between UDVA and CDVA. C Change in Snellen lines of CDVA. D Attempted SEQ. E Accuracy of MRSEQ to intended target (D).

Wavefront refraction

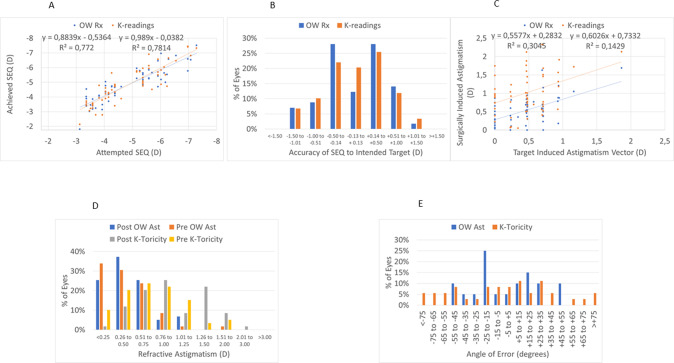

At 3 M, the scattergram of achieved change in wavefront refraction vs. attempted refractive correction of the SEQ showed a very good correlation (Fig. 2A), with 68% eyes within 0.5D from target (Fig. 2B). The scattergram of achieved change in wavefront refraction vs. attempted refractive correction of astigmatism showed only a fair correlation (Fig. 2C), with 63% eyes within 0.5D from target (Fig. 2D). The angle of error was within 25° from attempted astigmatism axis in 60% of the eyes (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2. Wavefront refraction.

A Change in wavefront refraction and keratometry readings vs. attempted SEQ (D). B Accuracy of wavefront and keratometry readings SEQ to intended target (D). C Scattegram of achieved change in wavefront refraction and keratometry readings vs attempted correction of the astigmatism. D Percentage of eyes within the intended target of postoperative wavefront astigmatism and keratometry readings toricity. E Angle of error for wavefront and keratometry readings astigmatism axis.

Topographic changes

At 3 M, the scattergram of achieved change in keratometry readings vs. attempted refractive correction of the SEQ showed a very good correlation (Fig. 2A), with 68% eyes within 0.5D from target (Fig. 2B). The scattergram of achieved change in keratometry readings vs. attempted refractive correction of astigmatism showed only a low correlation (Fig. 2C), with 59% eyes with postoperative corneal toricity of 1 D or less (Fig. 2D). The angle of error was within 25° in 42% of the eyes (Fig. 2E).

Wavefront refraction vs Topographic changes

At 3 M, the scattergram of achieved change in wavefront refraction vs. achieved change in keratometry readings of the SEQ showed a very good correlation (Fig. 3A), with 75% eyes within 0.75 D (Fig. 3B). The scattergram of achieved change in OW astigmatism vs change in keratometric toricity showed only a low correlation (Fig. 3C). The angle of error was within 25° for 42% of the eyes (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3. Wavefront refraction vs topographic changes.

A Scattegram of achieved change in wavefront refraction vs achieved change in keratometry readings of the SEQ. B Agreement of change in SEQ between wavefront refraction and keratometry readings. C Scattegram of achieved change in OW astigmatism vs change in keratometric toricity. D Angle of error between change in wavefront refraction and keratometry readings.

Aberrations

Ocular aberrations did not change from preoperative to 3 M postoperative for coma or spherical aberration, whereas HOA-RMS increased by +0.14 ± 0.15 µm (range −0.35 µm to +0.40 µm) (Fig. 4A, C). Corneal aberrations increased change from preoperative to 3 M postoperative for coma by +0.22 ± 0.21 µm (range −0.13 µm to +1.08 µm), spherical aberration +0.17 ± 0.19 µm (range −0.12 µm to +0.85 µm), and HOA-RMS by +0.32 ± 0.26 µm (range −0.03 µm to +1.41 µm) (Fig. 4B, C).

Fig. 4. Change in high order aberrations.

A Pre and postoperative OW aberrations. B Pre and postoperative CW aberrations. C Change in postoperative HOAs from preoperative baseline.

Complications

Lenticule removal was completed without relevant intraoperative complications. There were no events of suction loss during lenticule creation in this series (though suction loss occurred before the treatment started in six lenticule attempts), six cases of incisional bleeding or subconjunctival hemorrhage have been recorded, two abrasions at the incision and no tearing of the lenticule has been observed.

Discussion

In this work, we report the first European results of one new refractive lenticular extraction procedure—SmartSight by SCHWIND eye-tech-solutions at 3 M follow-up for a consecutive case series of patients treated by a single surgeon (MB), with SmartSight to correct myopia (with or without refractive astigmatism), at Svjetlost, Zagreb, Croatia.

The low energy delivered to the cornea (80–100 nJ per pulse) represents a potential advantage of SCHWIND ATOS and SmartSight, along with clinical features such as cyclotorsion control and eye-tracker guided centration, which were previously emphasized as major shortcomings in the treatment of a higher amount of astigmatism. Alternative lenticule extraction techniques as SMILE with VisuMax (Carl Zeiss Meditec) work in slightly higher energies (100–160 nJ pulse energy regime) [26]; whereas Z8 Neo (Ziemer Ophthalmics) works in a similar energy level (60–90 nJ per pulse) [27]; and ELITA (Johnson & Johnson Vision) works in a slightly lower level (45–70 nJ per pulse) [3].

At 3 M, 97% of the eyes reached an UDVA of 20/20 or better (Fig. 1A), for 98% of the eyes UDVA remained within one line of preoperative CDVA (Fig. 1B), 2% of the eyes (1 eye) lost 2 lines of CDVA (Fig. 1C). At 3 M, the scattergram showed an excellent refractive correction of the SEQ (Fig. 1D), with all eyes within 0.5 D from target (Fig. 1E).

This excellent refractive outcome in terms of manifest refraction was only partly confirmed by the objective refraction and the topographical changes. This suggests that manifest refraction may be more forgiving in terms of exactly determining the accuracy of the treatments [28]. At the same time, UDVA is a main driver for patient satisfaction, and CDVA loss of two lines occurred only in a single eye. Loss of two lines of CDVA was caused by severely dry eye and punctate epitheliopathy which resolved after extensive dry eye therapy 5 months after the surgery.

Alternative lenticule extraction techniques produce similar overall outcomes, as SMILE (Carl Zeiss Meditec) [29] with 95% of the cases in 20/25 or better UDVA postop; CLEAR (Ziemer Ophthalmics) [30] with 70% in 20/25 or better UDVA postop. Both percentages seem at first sight lower than the reported values for the study cohort; yet a comprehensive comparison can only be granted on the ground of congruent/homogeneous cohorts and study designs. In our cohort at 3 M, for the change in wavefront refraction or corneal keratometry 68% eyes were within 0.5D from the target (Fig. 1B), with 63% and 58% eyes within 0.5D from target astigmatism for wavefront refraction and corneal keratometry, respectively (Fig. 1D). The angle of error was within 25 deg from attempted astigmatism axis in 60% and 42% of the eyes for wavefront refraction and corneal keratometry, respectively (Fig. 1E).

Many studies have shown an increase in the correction efficiency for steeper corneas in myopia correction [31]. Yet it would be ideal that the correction measured in the cornea (using adequate models) would correspond 1-to-1 to the correction measured in the refraction, enabling an objective direct dose-response control [32].

Munnerlyn et al. expressed that the attempted correction univocally determines the postoperative corneal curvature (corneal refractive power) [33]. Conversely, it should be possible to objectively determine the refractive correction by comparing the postoperative with the preoperative corneal curvature (corneal refractive power).

Total corneal refractive power measurement may provide more accurate central corneal power compared to simulated keratometry and true net power [34].

Previous publications suggested that the under-correction in SMILE for higher refractive treatments could be associated with changes (steepening) of the posterior curvature as a result of a forward shift of the posterior surface [35, 36].

The SmartSight profile includes a refractive progressive transition zone (similar to the one used in the SCHWIND AMARIS) to smooth out the transition from treated to untreated cornea and possibly reduce the biomechanical changes and epithelial remodeling on the edge of the treatment (depending on the corneal curvature gradient otherwise induced by the correction) tapering the lenticule to zero thickness and power at the outer edge of the transition zone.

The average age at the time of treatment was 33 ± 6 years (23 to 45 years; median age was 32 years), this may be in line with current trends in LVC, but this means that these findings may not hold true for older patients. Similarly, eyes included in the study had manifest spherical equivalent refractive error between −3.25 and −8.5 D, so that the determined difference may not hold true for higher or lower myopic corrections (out of this range).

Keratometries were measured by Placido-OCT-based corneal topography (MS-39) by averaging three consecutive examinations. This average may provide a “low pass” filter and shall better represent the likely “true” keratometries (pre and post).

In this study at 3 M, the scattergram of achieved change in wavefront refraction vs. achieved change in keratometry readings of the SEQ showed a very good correlation (Fig. 2A), with 75% eyes within 0.75D (Fig. 2B).

Corneal aberrations slightly increased after the treatment, but the change of ocular aberrations was very minor and non-significant. This may confirm the relatively neutral behavior in terms of aberrations reported from other refractive lenticule extraction techniques, as well as being indicative of adequate centration.

Aberrations were induced across a 6 mm corneal diameter, but ocular aberrations could only be measured through the pupil so the actual values of analysis diameter were in the range of 5.4 ± 0.2 mm. SphAb was less positive when measured with ocular aberrations than for corneal aberrations. Postoperative corneal SphAb increased more than ocular SphAb. The RMS higher order aberrations increased (both for corneal and ocular aberrations), with corneal aberrations showing systematically higher inductions HOA than the ocular counterparts. Corneal aberrometry revealed an induction of positive SphAb, associated with an increase in the RMS higher-order aberrations.

Alternative lenticule extraction techniques also induce certain levels of HOAs, in SMILE (Carl Zeiss Meditec) [37]. similar to the presented cohort. This has also been previously reported for ablation-based procedures (to a higher extent) and may be actually in part intrinsic to removing corneal tissue. Observed complications in this study included suction loss, incisional bleeding, subconjunctival hemorrhage, abrasion at the incision, and tearing of the lenticule. Opaque bubble layer and black spots/areas or inaccurate laser pulse placement were not evaluated in this series since they did not interfere with the dissection (subjectively there was no impression that more resistance during dissection was found for those eyes), and on the other hand (unlike for flaps) there is no subsequent treatment step (excimer laser) for which the presence of opaque bubble layer may interfere with the tracking system (of the excimer laser). Our results are similar to those found by Kishore et al. [38] who also did not observe any relevant intraoperative complications.

Although, only 3-month data were included in the study longer follow up of this patient cohort is available. Up to 12 months follow up we did not observe any regression of the refractive outcome or need for additional enhancement due to regression (unpublished data). In the larger cohort of patients which includes more than 350 eyes some initial undercorrections were observed (unpublished work of the same group of authors, surgeries and follow up were performed during the period from 2020 to 2022).

Limitations of this work include a moderate sample size of 60 eyes of 31 consecutive patients who completed the 3-month follow-up included for analysis (i.e., both eyes have been considered), the retrospective nature of the analysis, including a single arm, and the fact that no treatment parameter was fixed (retrospective nature) including pulse energies, spot spacing, track spacing, suction level, caps thickness, or optical zone.

The presented clinical outcomes are based on 3-months of clinical follow-up, which is considered the minimum short-term meaningful in refractive surgery. However, shorter follow-ups have been reported in the literature to determine the time course of visual recovery. Longer follow-ups could shed light on the durability of performance. In conclusion, lenticule extraction after SmartSight is safe and efficacious in the first 3 months postoperatively. The post-operative outcomes indicate improvements in vision.

Summary

What was known before

Lenticule extraction has gained popularity in recent years and has become a serious alternative to LASIK and PRK nowadays.

Currently, there is one technology and technique clearly established in the market (SMILE using Visumax by Carl Zeiss Meditec, Germany) -two emerging alternatives have been introduced in the market (CLEAR using Z8 by Ziemer, Switzerland; and SmartSight using ATOS by SCHWIND eye-tech-solutions, Germany).

What this study adds

Lenticule extraction with SmartSight is safe and efficacious in the first 3 months postoperatively. The post-operative outcomes indicate improvements in vision.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: IG—study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, draft manuscript preparation. MB—study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, draft manuscript preparation. KG—study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results. SAM—study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, draft manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was self-financed.

Data availability

Data are available upon request.

Competing interests

SAM is an employee at and inventor in several patents owned by SCHWIND eye-tech-solutions. None of the other authors has financial or proprietary interests in materials or methods presented herein.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was retrospective with anonymized data. Ethics approval was not required due to the retrospective nature of the review chart. The purpose of this clinical research does not represent a clinical investigation. The medical device was used within its intended purpose without any additional invasive or patient-burdensome procedures used. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41433-023-02601-0.

References

- 1.Bohac M, Koncarevic M, Dukic A, Biscevic A, Cerovic V, Merlak M, et al. Unwanted astigmatism and high-order aberrations one year after excimer and femtosecond corneal surgery. Optom Vis Sci. 2018;95:1064–76. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reinstein DZ, Archer TJ, Gobbe M. Small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) history, fundamentals of a new refractive surgery technique and clinical outcomes. Eye Vis. 2014;1:3. doi: 10.1186/s40662-014-0003-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Izquierdo L, Jr, Sossa D, Ben-Shaul O, Henriquez MA. Corneal lenticule extraction assisted by a low-energy femtosecond laser. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2020;46:1217–21. doi: 10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000000236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pradhan KR, Arba-Mosquera S. Three-month outcomes of myopic astigmatism correction with small incision guided human cornea treatment. J Refract Surg. 2021;37:304–11. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20210210-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai PS, Blinder P, Migliori BJ, Neev J, Jin Y, Squier JA, et al. Plasma-mediated ablation: an optical tool for submicrometer surgery on neuronal and vascular systems. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2009;20:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noack J, Vogel A. Laser-induced plasma formation in water at nanosecond to femtosecond time scales: calculation of thresholds, absorption coefficients, and energy density. IEEE J Quantum Electron. 1999;35:1156–67. doi: 10.1109/3.777215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vogel A, Busch S, Jungnickel K, Birngruber R. Mechanisms of intraocular photodisruption with picosecond and nanosecond laser pulses. Lasers Surg Med. 1994;15:32–43. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900150106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arba-Mosquera S, Verma S. Analytical optimization of the ablation efficiency at normal and non-normal incidence for generic super Gaussian beam profiles. Biomed Opt Express. 2013;4:1422–33. doi: 10.1364/BOE.4.001422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chernyak DA. From wavefront device to laser: an alignment method for complete registration of the ablation to the cornea. J Refract Surg. 2005;21:463–8. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20050901-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gobbi PG, Carones F, Brancato R, Carena M, Fortini A, Scagliotti F, et al. Automatic eye tracker for excimer laser photorefractive keratectomy. J Refract Surg. 1995;11:S337–342. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19950502-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dausch D, Klein R, Schröder E, Dausch B. Excimer laser photorefractive keratectomy with tapered transition zone for high myopia. A preliminary report of six cases. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1993;19:590–4. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohac M, Biscevic A, Koncarevic M, Anticic M, Gabric N, Patel S. Comparison of wavelight allegretto eye-Q and Schwind Amaris 750 S excimer laser in treatment of high astigmatism. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252:1679–86. doi: 10.1007/s00417-014-2776-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siedlecki J, Luft N, Keidel L, Mayer WJ, Kreutzer T, Priglinger SG, et al. Variation of lenticule thickness for SMILE in low myopia. J Refract Surg. 2018;34:453–9. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20180516-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giri P, Azar DT. Risk profiles of ectasia after keratorefractive surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2017;28:337–42. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Genc SL, Ma H, Venugopalan V. Low-density plasma formation in aqueous biological media using sub-nanosecond laser pulses. Appl Phys Lett. 2014;105:063701. doi: 10.1063/1.4892665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Schuele G, Palanker D. Finesse of transparent tissue cutting by ultrafast lasers at various wavelengths. J Biomed Opt. 2015;20:125004. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.20.12.125004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogel A, Capon MR, Asiyo-Vogel MN, Birngruber R. Intraocular photodisruption with picosecond and nanosecond laser pulses: tissue effects in cornea, lens, and retina. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:3032–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Ortueta D, Schreyger FD. Centration on the cornea vertex normal during hyperopic refractive photoablation using videokeratoscopy. J Refract Surg. 2007;23:198–200. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20070201-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Köse B. Detection of and compensation for static cyclotorsion with an image-guided system in SMILE. J Refract Surg. 2020;36:142–9. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20200210-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vinciguerra P, Roberts CJ, Albé E, Romano MR, Mahmoud A, Trazza S, et al. Corneal curvature gradient map: a new corneal topography map to predict the corneal healing process. J Refract Surg. 2014;30:202–7. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20140218-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gatinel D, Weyhausen A, Bischoff M. The percent volume altered in correction of myopia and myopic astigmatism with PRK, LASIK, and SMILE. J Refract Surg. 2020;36:844–50. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20200827-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kind R, Kiraly L, Taneri S, Troeber L, Wiltfang R, Bechmann M, et al. Flushing versus not flushing the interface during small-incision lenticule extraction. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019;45:562–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shetty R, Shroff R, Kaweri L, Jayadev C, Kummelil MK, Sinha Roy A. Intra-operative cap repositioning in Small Incision Lenticule Extraction (SMILE) for enhanced visual recovery. Curr Eye Res. 2016;41:1532–8. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2016.1168848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schiano-Lomoriello D, Bono V, Abicca I, Savini G. Repeatability of anterior segment measurements by optical coherence tomography combined with Placido disk corneal topography in eyes with keratoconus. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1124.. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57926-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plaza-Puche AB, Salerno LC, Versaci F, Romero D, Alio JL. Clinical evaluation of the repeatability of ocular aberrometry obtained with a new pyramid wavefront sensor. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2019;29:585–92. doi: 10.1177/1120672118816060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taneri S, Arba-Mosquera S, Rost A, Kießler S, Dick HB. Repeatability and reproducibility of manifest refraction. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2020;46:1659–66. doi: 10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton DR, Chen AC, Khorrami R, Nutkiewicz M, Nejad M. Comparison of early visual outcomes after low-energy SMILE, high-energy SMILE, and LASIK for myopia and myopic astigmatism in the United States. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2021;47:18–26. doi: 10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000000368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahaman A, Rahaman S, Fu H. Glass burn threshold: an innovative method to characterize refractive femtosecond laser performance. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2022;63:4364–A0301. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J, Wang Y. Influence of preoperative keratometry on refractive outcomes for myopia correction with small incision lenticule extraction. J Refract Surg. 2020;36:374–9. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20200513-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taneri S, Arba-Mosquera S, Rost A, Hansson C, Dick HB. Results of thin-cap small-incision lenticule extraction. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2021;47:439–44. doi: 10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000000470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leccisotti A, Fields SV, De Bartolo G. Refractive corneal lenticule extraction with the CLEAR femtosecond laser application. Cornea. 2022. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000003123. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Kaluzny BJ, Verma S, Piotrowiak-Słupska I, Kaszuba-Modrzejewska M, Rzeszewska-Zamiara J, Stachura J, et al. Three-year outcomes of mixed astigmatism correction with single-step transepithelial photorefractive keratectomy with a large ablation zone. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2021;47:450–8. doi: 10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000000476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munnerlyn CR, Koons SJ, Marshall J. Photorefractive keratectomy: a technique for laser refractive surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1988;14:46–52. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(88)80063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qian Y, Liu Y, Zhou X, Naidu RK. Comparison of corneal power and astigmatism between simulated keratometry, true net power, and total corneal refractive power before and after SMILE surgery. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:9659481. doi: 10.1155/2017/9659481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sideroudi H, Lazaridis A, Messerschmidt-Roth A, Labiris G, Kozobolis V, Sekundo W. Corneal irregular astigmatism and curvature changes after small incision lenticule extraction: three-year follow-up. Cornea. 2018;37:875–80. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ganesh S, Patel U, Brar S. Posterior corneal curvature changes following refractive small incision lenticule extraction. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:1359–64. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S84354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee H, Roberts CJ, Arba-Mosquera S, Kang DSY, Reinstein DZ, Kim TI. Relationship between decentration and induced corneal higher-order aberrations following small-incision lenticule extraction procedure. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:2316–24. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-23451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pradhan KR, Arba Mosquera S. Twelve-month outcomes of a new refractive lenticular extraction procedure. J Optom. 2023;16:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.optom.2021.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.