Abstract

The β-barrel assembly machinery (BAM) complex is responsible for inserting outer membrane proteins (OMPs) into the Escherichia coli outer membrane. The SecYEG translocon inserts inner membrane proteins into the inner membrane and translocates both soluble proteins and nascent OMPs into the periplasm. Recent reports describe Sec possibly playing a direct role in OMP biogenesis through interactions with the soluble polypeptide transport-associated (POTRA) domains of BamA (the central OMP component of BAM). Here we probe the diffusion behavior of these protein complexes using photoactivatable super-resolution localization microscopy and single-particle tracking in live E. coli cells of BAM and SecYEG components BamA and SecE and compare them to other outer and inner membrane proteins. To accurately measure trajectories on the highly curved cell surface, three-dimensional tracking was performed using double-helix point-spread function microscopy. All proteins tested exhibit two diffusive modes characterized by “slow” and “fast” diffusion coefficients. We implement a diffusion coefficient analysis as a function of the measurement lag time to separate positional uncertainty from true mobility. The resulting true diffusion coefficients of the slow and fast modes showed a complete immobility of full-length BamA constructs in the time frame of the experiment, whereas the OMP OmpLA displayed a slow diffusion consistent with the high viscosity of the outer membrane. The periplasmic POTRA domains of BamA were found to anchor BAM to other cellular structures and render it immobile. However, deletion of individual distal POTRA domains resulted in increased mobility, suggesting that these domains are required for the full set of cellular interactions. SecE diffusion was much slower than that of the inner membrane protein PgpB and was more like OMPs and BamA. Strikingly, SecE diffused faster upon POTRA domain deletion. These results are consistent with the existence of a BAM-SecYEG trans-periplasmic assembly in live E. coli cells.

Significance

Single-molecule super-resolution localization microscopy provides mechanistic insight into membrane processes, yet it is underutilized in the context of OMP biogenesis. Here, we present a study using three-dimensional (3D) single-particle tracking in live cells via photoactivatable localization microscopy combined with the double-helix point-spread function to determine the diffusive behavior of the β-barrel assembly machinery (BAM), the SecYEG translocon, and compare them to PgpB and OmpLA as reference inner and outer transmembrane proteins. This work represents the first single-particle tracking study of BAM and the SecYEG translocon in live cells, giving insight into the nature of the Escherichia coli. cell envelope and establishing a platform for high-resolution 3D imaging of gram-negative bacterial membrane proteins.

Introduction

Gram-negative bacteria have a unique cellular envelope comprising two membranes separated by the periplasm that contains the peptidoglycan wall (1). The outer membrane (OM) is an essential protective barrier against antibiotics and other lipophilic agents, and it facilitates functions such as nutrient uptake and interactions with the host. Integral outer membrane proteins (OMPs) fold into β barrels that span the entire width of the membrane (2). Unlike co-translationally folded α-helical inner membrane proteins (IMPs), OMPs are folded post-translationally (3,4,5,6). After synthesis in the cytoplasm, OMPs are translocated across the inner membrane (IM) and into the periplasm through the Sec translocon (7). OMPs are folded into the outer membrane by an essential complex named the β-barrel assembly machinery (BAM) (8,9,10). The BAM consists of BamA, itself a β-barrel OMP, and four lipoprotein subunits BamB, C, D, and E. BamA is the central component of BAM and is present in every bacterium with two membranes (11). BamA is composed of five N-terminal periplasmic polypeptide transport-associated (POTRA) domains and a β barrel of 16 β strands that is embedded in the outer membrane. POTRA domains bind nascent OMPs (12) and may promote the formation of β strands in OMP substrates (13,14,15). There are no known contact points between the inner and outer membranes (16). Therefore, nascent OMPs must traverse the periplasm before they are delivered to BAM.

Although OMP membrane insertion and folding have been the subject of intense investigation, the mechanism of OMP trafficking across the periplasm after emerging from the Sec translocon and their delivery to the BAM complex remain poorly understood. The current consensus hypothesis for this mechanism is that periplasmic chaperones such as SurA and FkpA bind nascent OMPs as they emerge in the periplasm and shuttle them to BAM (12,17,18,19). However, recent biochemical experiments suggest that a trans-periplasmic BAM-SecYEG supercomplex may be important for OMP biogenesis (20,21,22,23). This model has not yet been investigated through in vivo biophysical methods such as live-cell microscopy.

Single-molecule techniques such as atomic force microscopy, fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, and Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) have been used extensively to study OMPS (24,25,26), yet single-particle tracking (SPT) has remained less utilized to study OMPs in cells. This is likely due to the small size of bacteria, the reported slow diffusion of OMPs in the outer membrane, and the difficulty presented by the oxidizing periplasmic environment for fluorescent proteins. SPT is a powerful tool in examining bacterial processes, capable of resolving dynamics at a level that probes molecular interactions and binding events (27,28,29,30). Previous studies of OMP diffusion (31,32,33,34) have been limited to mean squared displacement analysis of two-dimensional (2D) experiments or fluorescence recovery after photobleaching, both of which provide limited information on heterogeneity, such as the presence of multiple populations or multiple diffusive modes (35). Here, we compare the diffusion of the BAM complex with that of the Sec complex as well as various OMPs, BamA mutants, and an IMP using three-dimensional (3D) SPT combined with live-cell photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM). These comparisons were enabled by creating multiple genetically encoded photoactivatable mCherry (PAmCherry) fusions. 3D tracking allowed us to extract accurate measurements of motion on highly curved bacterial surfaces, and the use of complementary cumulative distribution function (CCDF) analysis enabled us to distinguish the presence of multiple diffusive modes. Moreover, this approach has the capability to discern small differences in OMP diffusion rates across multiple modes. The findings enabled by these experiments provide new insights into the diffusive behaviors and potential interactions of the BAM and Sec complexes, as well as the mobility of IMPs and OMPs in their unique live-cell membrane environments.

Materials and methods

Strain and plasmid construction

Plasmid pMS 1166 was generated by Gibson assembly, inserting the gene for photoactivatable mCherry (PAmCherry, obtained as a gift from Prof. Carlos Bustamante) with an STGSG linker at the N terminus and a GSGSG linker at the C terminus, between the signal sequence and the coding sequence for mature BamA cloned in the pZS21 vector (a generous gift from Prof. Thomas Silhavy) (Table S1). Subsequent deletions of POTRA 1 (ΔP1, pMS1722) and POTRAs 1 and 2 (ΔP12, pMS1729) were obtained by single-fragment Gibson assembly reactions using pMS1166 as a template. All pBAD plasmids in this study were obtained by Gibson reactions with fragments from a pBAD vector, an insert with the respective gene from genomic Escherichia coli DH5α DNA, and PAmCherry with a five-amino-acid linker (STGSG or GSGSG as indicated for each plasmid). The strain MSC18 was generated from the reference MC4100 strain (36), replacing the endogenous BamA gene with the PAmCherry fusion described above, using a scarless λ-red recombineering approach (Table S2). The pRSET-A plasmids were formed by Gibson reactions from the pRSET-A vector and an insert with the respective gene from their pBAD plasmids made during this study.

Cell preparation for live microscopy

For experiments involving the BamA-depletion JCM166 strain (37), cells with their respective plasmids were initially plated on Luria Broth (LB) medium with 0.1% arabinose to allow expression of endogenous BamA. Cells were then passaged onto LB plates with 0.1% fucose multiple times to deplete them of the endogenous BamA. This process was repeated until a negative control JCM166 strain containing a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-encoding pZS21 plasmid ceased to grow, indicating depletion of the endogenous BamA. JCM166 colonies expressing plasmid-borne FL-BamA, ΔP1 BamA, or ΔP12 BamA were then used for the imaging procedures. For strains assessing SecE and PgpB diffusion in POTRA deletion backgrounds, JCM166 cells with the pZS21 plasmid were kept in 0.1% arabinose and transformed with the second pRSET-A plasmid before the above depletion procedure was performed.

Before imaging, overnight cultures in LB medium were diluted 100-fold in fresh LB and grown at 37°C to optical density 600 (OD600) 0.5–0.6. For experiments with JCM166 cells, the medium was supplemented with 0.05% fucose to continuously repress endogenous BamA expression. No induction step was necessary due to the leaky (pBAD), constitutive (JCM166), or native promoter (MSC18)-driven expression of the desired protein-PAmCherry fusion. Cells were then centrifuged at 2000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in 1 mL of 0.01× PBS-S (0.01× PBS supplemented with 20 mM glucose, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2) and centrifuged again. This process was repeated twice to wash fluorescent LB medium away. After final resuspension in 1 mL of 0.01× PBS-S, 50 μL of 100× diluted 0.1 μm Tetraspeck Beads (Thermo Fisher) were vortexed and added to the cell solution. Then 50 μL of this mixture were applied to a 0.01% poly-L-lysine-coated 35-mm imaging dish with a #1.5 glass coverslip (Ibidi). Slides were incubated for 3 min to allow cell attachment to the poly-L-lysine surface. The cells and surrounding glass surface were rinsed three times with 1 mL of M9-S (M9 minimal medium supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.4% (w/v) D-glucose). Cells were allowed to recover by incubation in ∼4 mL of M9-S for 20 min before imaging. For the Tetraspeck bead diffusion experiment, 0.1 μm Tetraspeck Microspheres were diluted in 0.01× PBS-S without cells and then bound, washed, and prepared identically as above. Representative sample movies are included in the supporting material.

spt-PALM acquisition

Microscopy was performed on an NSTORM super-resolution microscope system equipped with a SPINDLE module including a short-range high-precision DH2R phase mask and an emission filter (Double Helix Optics, Boulder, CO). The microscope was equipped with four laser lines (405/488/561/640 nm) and a 100× oil immersion objective (Olympus 1.49 NA). The environmental chamber was set to 20°C for all data collection. Tracking experiments were acquired by imaging a 33.3 × 33.3- or 66.6 × 66.6-μm area with the 405- and 561-nm lasers set at the optimal highly inclined and laminated optical sheet illumination angle, and the focal plane was set at ∼700 nm from the surface to be approximately centered on the E. coli cell volume. Samples were pre-photobleached with the 561-nm laser for 3 min at a power output of 75 mW. Data were then collected with a 561-nm excitation laser for the entire duration of the imaging at a power output of 52.5 mW, and an activation laser of 405 nm pulsed every 20 frames at a power output of 1–10 mW. For each construct, 25,000–50,000 frames were collected with an acquisition time of 70 ms/frame. Experiments were conducted in at least triplicate over two separate days of imaging. For the Tetraspeck bead diffusion experiments, beads were bleached to similar photon counts (<8000) as PAmCherry in tracking experiments and movies were collected as shown above. Representative sample movies (Video S1) for all tracked proteins are included in the supporting material.

SPT data analysis

Single particles were localized with the 3DTRAX software plugin (Double Helix Optics) for ImageJ. Each day the phase mask was used, a calibration was performed over a 3-μm axial range using a 40-nm z step. Using the respective calibration file, 3D super-resolution localization data were obtained for each experiment. For each experiment, an image correlation method was applied to correct for drift. Tracks were created with a maximum linking distance of 250 nm, a maximum frame gap of 2, and a minimum track length of four frames. To minimize noise associated with fluorescent impurities on the support, the data from the bottom 200 nm of each cell (i.e., closest to the cover slip) were discarded. Single-particle tracks were then exported to MATLAB for further processing. Custom MATLAB scripts were written to perform several functions. For datasets examining diffusion based on distance from the centroid in dividing cells, cells were manually segmented from a brightfield image to create a binary mask. For each trajectory, the radius of the smallest sphere encompassing the entire trajectory was calculated, and a histogram of these spherical radii was created and fitted to a double-Gaussian function. Trajectories having a minimal spherical radius of more than two standard deviations greater than the larger of the two Gaussian means were deemed to be anomalous and eliminated from further analysis. For the remaining trajectories, squared displacements as a function of lag time were calculated, and an apparent short-time diffusion coefficient was determined from a linear fit to the first three squared displacements from the first four frames of each track. CCDFs were calculated using the squared displacements for each construct for lag times of 70, 140, 210, and 280 ms. Finally, the distance of each trajectory from the centroid of its respective cell was calculated.

To obtain complementary cumulative distributions, the squared displacement was defined as the square of the Euclidean distance traveled from frame to frame:

| (1) |

where Δt is the time between frames (e.g., 70 ms); r(t) is the displacement between the times t and t + Δt; x(t), y(t), and z(t) are the Cartesian position coordinates at time t; and x(t) + Δt, y(t) + Δt, and z(t) + Δt are the Cartesian position coordinates at time t + Δt. These distributions were fitted to a double exponential mixture model in GraphPad Prism (Version 9.3.1):

| (2) |

Afast and Aslow represent the population fractions of the fast and slow modes, respectively. The %slow and %fast were determined as the respective percentage associated with Afast and Aslow (Table S3). The data for all constructs were fitted to a double exponential decay. The fits were weighted by two different methods and the compared results were found to be nearly identical (Table S3). The first method applied was to weigh by a factor of 1/Y2. Alternatively, a “binning” weighting method was applied to assess the potential over-emphasizing of the data-rich small-displacement portion of CCDFs in the fitting procedure. This weighting method consisted of rounding squared displacements to the nearest nm2, binning the identical squared displacements, and weighting each bin by the standard deviation of the Y values in that bin. All values displayed in this manuscript were determined using weighting by a factor of 1/Y2.

In vivo complementation assay

FL-BamA and POTRA deletion constructs were tested for complementation effectiveness as detailed in (38). Briefly, JCM166 cells containing pZS21 vectors containing a GFP control and BamA test constructs were grown overnight in 0.05% arabinose to allow endogenous BamA expression. Cells were pelleted to remove residual arabinose, resuspended in LB medium with 0.05% fucose to shut down expression of the endogenous BamA expression, and allowed to grow at 37°C in depleted conditions. When the OD600 reached 0.5–0.6, cells were diluted to an OD600 of 0.025 in 3 mL of the same medium.

Western blotting

Cells were grown in 50-mL cultures to an OD600 of 0.4. Cultures were centrifuged for 20 min at 5000 × g and resuspended in 3 mL of BugBuster Protein Extraction Reagent (EMD Millipore), 1× Complete Protease Inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and gently rotated for 10 min at room temperature to lyse the cells. The lysates were centrifuged for 20 min at 21,000 × g at 4°C and the supernatant was run on a 4%–20% polyacrylamide gradient Mini-PROTEAN TGX precast gel (Bio-Rad) (150 V, 60 min). The samples were then blotted on an Immobilon-P PVDF membrane (Millipore Sigma) and blocked with 3% dried nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline buffer with Tween-20 (TBST) overnight at room temperature. Blots were incubated with primary anti-BamA antibodies (Cocalico Biologicals) (1:2000) raised against purified BamA-E in 3% milk in TBST buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were then washed with TBST (5 × 3 min) and probed with secondary goat anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:2000, Innovative Solutions) for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were washed as described above and detection was performed with Clarity ECL western blotting substrates (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Images were recorded using an ImageQuant LAS 4000 imager (GE) and the corresponding software.

Results

All proteins in this work were visualized using the photoactivatable red fluorescent protein mCherry (PAmCherry) tag that, upon activation, is fluorescent in the periplasm (39). The spatial density of fluorescently active PAmCherry fusion proteins was maintained at an appropriate level for single-molecule localization using irradiation with a 405-nm laser (40), stochastically activating individual molecules, and enabling so-called photoactivated light microscopy (PALM). PALM has similar advantages to fluorescence microscopy with conventional fluorescent proteins and is an established platform for bacterial live-cell super-resolution imaging (41,42,43). Although many SPT studies rely on 2D imaging, this approach complicates the analysis of trajectories on highly curved surfaces such as bacterial cells, as the molecules also diffuse along the optical (z) axis. We therefore implemented 3D tracking using the Double Helix SPINDLE module (Double Helix Optics) to produce the two-lobed double-helix point-spread function (DH-PSF), a well-established tool in 3D tracking (44,45,46,47,48). The DH-PSF encodes the axial position along the optical (z) axis into the shape and rotation of the two lobes (Fig. 1 A) (49). The approach has the advantage of localizing particles in the z axis over a large depth range (1.5–2.0 μm) with a localization precision that is more uniform than other approaches (50,51). Therefore, the implementation enabled direct 3D sampling of the entire E. coli cell volume. Furthermore, as the particle displacements per frame are small compared to the cell radius of curvature (Fig. 1 B), the particle trajectories can be analyzed with no deconvolution or unwrapping of the cell shape without affecting the accuracy of the measured diffusion coefficients (45). SPT was combined with PALM (spt-PALM) by alternatingly activating and subsequently imaging individual fluorophores as they diffused until photobleaching (52,53). From this tracking information, parameters such as diffusion coefficients and modes were determined and then compared among the membrane proteins targeted in this study.

Figure 1.

Single molecules were tracked in three dimensions with spt-PALM and the DH-PSF. (A) A representative sequence of DH-PSF images, taken in series 70 ms apart, showing a single molecule as two lobes overlaid on a diffuse background stemming from a BamA fusion protein fluorescing in the periplasm. The rotation of the two lobes around the center of the distribution correlates with the molecule’s z position, here showing a decrease in z. These images were taken from consecutive frames in the track shown in (B). Scale bars, 1 μm. (B) Brightfield image of an E. coli cell from a tracking experiment. The trajectory in (C) is superimposed on the image at the bottom pole of the cell (boxed inset). (C) Visualization of 3D motion for the trajectory shown in (B). The color of the localization point corresponds with its z position, from blue (high z) to red (low z). To see this figure in color, go online.

The BAM complex diffuses slower than free OMPs

To assess the diffusion of the BAM complex, a mutant E. coli strain MSC18 was created with BamA N-terminally tagged with PAmCherry using a scarless lambda red recombination strategy. This strategy ensured that MSC18 cells were rid of untagged BamA and expressed the essential tagged BamA protein from the endogenous promoter (Fig. S1 A). MSC18 cells were capable of growth at a near-normal rate (Fig. S1 B), confirming the expression and functionality of the fusion protein. Raw double-helix fluorescence images and reconstructed track data for a PAmCherry-BamA molecule from the MSC18 strain are shown in Fig. 1. This representative track is shown in its cellular context in Fig. 1 B, revealing the minute scale of displacement by the BamA fusion in the OM. As shown in Fig. 1 C, this spt-PALM method detects nanoscale membrane protein diffusion in 3D.

The apparent diffusion coefficient (Dapp) can be quantified from SPT data in multiple ways, and the most frequently used is mean squared displacement (MSD) analysis (54). MSD analysis is helpful in calculating an average Dapp from consecutive time points of a molecule’s track. We achieved this by determining the squared displacement from the first four points of each individual track (70–280 ms) to calculate the D, derived from the slope. The tracks that displayed positive slopes are shown in Fig. 2 A, with the median Dapp indicated for each construct. BamA-PAmCherry diffused very slowly (median Dapp = ∼0.005 μm2/s). The slow diffusion rates of OMPs observed in this study agree with the low diffusion rates reported previously (32,34). For comparison, we used the same approach for MC4100 E. coli cells expressing plasmid-borne OmpLA and BamA barrel (BamA with all POTRA domains deleted) fusions with PAmCherry. The constructs in MC4100 cells were expressed from a pBAD vector without induction (leaky expression) to minimize OMP density and effects of overcrowding. OmpLA, an OMP with 12 β strands that functions as a hydrolase (55), showed a significantly faster diffusion (median Dapp = ∼0.010 μm2/s) than BamA (Fig. 2 A). This result was not a surprise, given the smaller size of OmpLA’s β barrel. Interestingly, the truncated BamA barrel displayed a similar diffusion profile to OmpLA (median Dapp = ∼0.009 μm2/s) (Fig. 2 A). We interpreted this result to mean that the diffusion speed differences between BamA and free OMPs were not simply due to the size of the BamA’s larger β barrel (e.g., resulting in greater drag and hence slower diffusion) but also due to the interactions of BamA’s POTRA domains or associated BAM subunits with other cellular elements.

Figure 2.

BamA POTRA domains anchor the BAM complex in the E. coli cell envelope. (A) Histogram showing the measured apparent diffusion coefficients (Dapp) for BamA-PAmCherry, OmpLA-PAmCherry, and BamA barrel-PAmCherry. Median depicted as black line. Data shown on a log10 scale. A Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test indicated a p < 0.0001 between BamA (n = 648 tracks) and OmpLA (n = 585 tracks) and between BamA and BamA barrel (n = 1039 tracks), and p = 0.27 between OmpLA and BamA barrel. (B) Complementary cumulative squared displacement distributions for OMP constructs. The black lines represent the best fits to a double exponential mixture model. (C and D) Dependence of the apparent diffusion coefficients on () on lag time. The individual apparent diffusion coefficients for the slow (C) and fast (D) modes are shown as a function of inverse lag time. The data points and error bars are derived from the average and SE of the mean values determined from experimental replicates, respectively. The Dtrue values extracted from the y intercepts are annotated on the figures, and the number in parentheses represents the uncertainty in the least significant digit as given by the SE of the mean from experimental replicates. (C) R2 values for each fit are 0.9947, 0.9675, and 0.9937 for BamA-PAmCherry, OmpLA-PAmCherry, and BamA barrel-PAmCherry, respectively. An extra sum-of-squares F test to compare the y intercepts was performed and yielded a p value of 0.39 for BamA and OmpLA, 0.52 for BamA and BamA barrel, and 0.64 for OmpLA and BamA barrel. (D) R2 values for each fit are 0.9488, 0.9610, and 0.9583 for BamA-PAmCherry, OmpLA-PAmCherry, and BamA barrel-PAmCherry, respectively. An extra sum-of-squares F test to compare the y intercepts was performed and yielded a p value of 0.0067 for the of BamA and OmpLA, 0.025 for BamA and BamA barrel, and 0.57 for OmpLA and BamA barrel. To see this figure in color, go online.

Although membrane proteins often display multiple diffusive modes (or populations), the Dapp derived from MSD analysis represents the weighted average of such modes. To test if multiple diffusive behaviors are exhibited by OMPs, we calculated the CCDFs for each construct from its single-step (70 ms) squared displacement values. The distribution was then fitted to one or more exponentials to account for a single or multiple behaviors. BamA’s CCDF fit best to a two-exponential decay function, indicating that it exhibits two diffusive modes: slow () and fast () (Table S4). Both the apparent diffusion coefficients ( = 0.012 ± 0.001 μm2/s, = 0.038 ± 0.007 μm2/s) and percentage of time observed (%slow = 83 ± 5, %fast = 17 ± 5) were obtained from the fit and suggested that BamA was moving in its slow mode a large majority of the time in these experiments (Table S3). We determined these behaviors to be modes and not distinct protein populations, as they could both be observed within a single track and the D histograms displayed only one population (Fig. 2 A). Fig. 2 B shows the distributions fit to two exponentials, with their fitting parameters shown in Table S3. OmpLA ( = 0.019 ± 0.003 μm2/s, = 0.048 ± 0.005 μm2/s) and the BamA barrel ( = 0.022 ± 0.001 μm2/s, = 0.06 ± 0.01 μm2/s) both were also best described by two exponentials and displayed faster diffusion than BamA (Fig. 2 B). Interestingly, OmpLA diffused at more frequently compared to both the BAM complex and the BamA barrel (Table S3).

Uncertainty in the spatial localization of SPT experiments can make immobile molecules appear mobile. This is illustrated by tracking data collected for Tetraspeck fluorescent beads that adhere to the glass slides utilized for imaging and are thus immobile. Nevertheless, CCDF analysis of their single-step (70 ms) squared displacements was best fit by a single exponential that yielded an apparent diffusion coefficient of 0.012 ± 0.001 μm2/s for that particular time lag (Fig. S2 A). Therefore, the spatial localization uncertainty can exaggerate the apparent values of diffusion coefficient of proteins of interest. This is especially true when studying OMPs in vivo, due to the slow diffusion observed in the outer membrane and the relatively high fluorescent background signal during live-cell imaging. In some analyses, this is interpreted as a discrete diffusive mode. However, building on standard treatments of multimodal diffusion on cell membranes (56,57), Kues and Kubitscheck demonstrated that diffusion coefficients for multimodal diffusion can be extracted by examining the dependence of the apparent diffusion coefficients on lag time between experimental observations (58). Kastantin and Schwartz then advanced this approach, extracting apparent diffusion coefficients for multiple modes from CCDF analyses and showing that positional uncertainty induces a shift in the measured diffusion coefficients by σ2/Δt where σ is the positional uncertainty length scale and Δt is the lag time (59). This provides a convenient graphical method to extract the true diffusion coefficients for each mode from the y intercept of a plot of apparent diffusion coefficients vs. the inverse lag time (1/Δt). We thus implemented this approach carrying out additional CCDF analyses of the squared displacements for double, triple, and quadruple steps that resulted in additional and values at three additional lag times (140, 210, and 280 ms; Table S5; Fig. S3) to estimate the true diffusion coefficients for the slow () and fast () diffusion modes observed in BamA, OmpLA, and BamA barrel (Fig. 2 C–D; Table 1). Accounting for experimental uncertainty, the was indistinguishable from zero for all constructs (BamA, 0.0002 ± 0.0006 μm2/s; OmpLA, 0.001 ± 0.002 μm2/s; BamA barrel, 0.001 ± 0.001 μm2/s). Furthermore, a similar analysis of the apparent diffusion of immobile beads yielded a Dtrue of −0.00005 ± 0.00002 μm2/s. An extra sum-of-squares F test indicates this is not significantly different from those obtained for the of BamA, OmpLA, or the BamA barrel (p ≥ 0.30, Table S6). These results are consistent with an immobile mode at the resolution of our experiments (Fig. 2 C). These observations led us to conclude that this is characteristic of the OMPs transient interactions with immobile cellular structures or highly crowded environments resulting in an immobile mode on the scale of these experiments. OmpLA and BamA barrel constructs exhibited comparable mobility in their true modes (Fig. 2 D). The BamA barrel’s mean (0.018 ± 0.003 μm2/s) was slightly slower than OmpLA’s, as expected (0.021 ± 0.001 μm2/s), consistent with the difference in barrel size. Interestingly, the value of for the BAM complex was also indistinguishable from zero (−0.002 ± 0.004 μm2/s) based on the experimental resolution (Fig. 2 D), implying that, even though there is a distinct second mode consistent with faster movement, the speed of this motion is below the detection limit of these experiments. This remarkably slow was significantly slower than those of the other OMPs. We conclude that is affected by the size of the OMP barrel and any interaction with other mobile proteins that may limit the diffusion of the complex. This interpretation is consistent with reports that BAM may operate within “precincts” where a few complexes are assembled (60), which may reduce their diffusion below the detection limit of our approach.

Table 1.

True diffusion coefficients after accounting for localization uncertainty

| PAmCherry construct | Strain | μm2/s) | (μm2/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BamA | MSC18 | 0.0002 (6) | −0.002 (4) |

| OmpLA | MC4100 | 0.001 (2) | 0.021 (1) |

| BamA barrel | MC4100 | 0.001 (1) | 0.018 (3) |

| FL-BamA | JCM166 | 0.0001 (5) | 0.002 (2) |

| ΔP1 BamA | JCM166 | 0.0013 (6) | 0.007 (4) |

| ΔP12 BamA | JCM166 | 0.003 (1) | 0.006 (3) |

| SecE | MC4100 | 0.001 (2) | 0.005 (1) |

| PgpB | MC4100 | 0.0028 (8) | 0.039 (4) |

| SecE | JCM166/FL-BamA | 0.001 (1) | 0.0052 (5) |

| JCM166/ΔP1 BamA | 0.0020 (8) | 0.0163 (9) | |

| JCM166/ΔP12 BamA | 0.0019 (9) | 0.0167 (7) | |

| PgpB | JCM166/FL-BamA | 0.0022 (6) | 0.0351 (4) |

| JCM166/ΔP1 BamA | 0.0029 (7) | 0.0371 (8) | |

| JCM166/ΔP12 BamA | 0.0026 (9) | 0.0363 (6) |

These values were obtained by calculating the y intercept when plotting Dapp vs. lag time. The number in parentheses represents uncertainty in the least significant digit as given by the SE of the mean of these values calculated from experimental replicates. Strains denoted with a “/” are composed of the strain on the left side transformed with a plasmid containing the construct on the right side (without a fluorescent tag).

POTRA deletion mutants alter the OMP environment of BamA

The interactions that lead to the immobility of the BAM complex shown above are presumably mediated by BamA’s POTRA domains. POTRAs 3–5 are proximal to the β barrel of BamA, function as a scaffold for the other BAM subunits, and are essential for cell viability (6). These domains have also been reported to interact with the mature peptidoglycan wall (61). Conversely, POTRAs 1 and 2 are thought to bind nascent OMP substrates to facilitate their folding process (15). However, they have also been proposed to interact with IMPs. Mutants with deletions of POTRA 1 (ΔP1) or both POTRA 1 and POTRA 2 (ΔP12) from BamA were tested to probe for potential interactions with these domains and the effect of their deletion on diffusion in comparison to full-length BamA.

Depletion strains can be used to eliminate essential endogenous proteins of interest while expressing a functional fluorescent fusion in its place. The JCM166 strain is a BamA-depletion strain, where the expression of native BamA is under the control of a pBAD promoter (37). This allows for expression of endogenous BamA in the presence of arabinose and the shutdown of its expression in the presence of fucose. We utilized this strain in combination with pZS21 plasmids that constitutively express fusions of PAmCherry with full-length BamA (FL-BamA), BamA missing the POTRA1 domain (ΔP1 BamA), or BamA missing POTRA1 and POTRA2 (ΔP12 BamA) to evaluate their diffusive behaviors. After multiple passages of the cells to fucose-containing medium to deplete the endogenous wild-type BamA, the constructs were tested for their ability to functionally complement the depletion. Cells transformed with plasmids expressing PAmCherry fusions of FL-BamA or ΔP1 BamA displayed growth rates comparable to those of control cells grown in arabinose (Fig. S4). However, cells expressing PAmCherry-ΔP12-BamA grew more slowly, suggesting an impaired functionality of this construct.

Examination of the distribution of Dapp derived from single-track MSD analysis revealed similar behaviors for FL-BamA (median Dapp = ∼0.007 μm2/s) and ΔP1 BamA (median Dapp = ∼0.006 μm2/s) (Fig. 3 A), whereas ΔP12 BamA diffused more rapidly (median Dapp = ∼0.010 μm2/s). Analysis of the CCDFs (Fig. 3 B) revealed similar trends: the magnitudes of and for FL-BamA, ΔP1 BamA, and ΔP12 BamA were similar (Table S3), but ΔP12 BamA was observed in its mode >40% of the time, more than twice as frequently as for FL-BamA and ΔP1 BamA (Fig. 3 B; Table S3).

Figure 3.

Deletion of POTRA domains 1 and 2 has varying effects on BamA diffusion. (A) Histogram showing the measured apparent diffusion coefficients (Dapp) for FL-BamA, ΔP1 BamA, and ΔP12 BamA. Median depicted as black line. Data shown on a log10 scale. A KS test indicated a p value of 0.17 between FL-BamA (n = 1759 tracks) and ΔP1 BamA (n = 2206 tracks), and p < 0.0001 between ΔP12 BamA (n = 638 tracks) and both FL-BamA and ΔP1 BamA. (B) Complementary cumulative probability distributions of single-step square displacements for OMP constructs. The black lines represent the best fits to the sum of two exponentials. (C and D) Dependence of the apparent diffusion coefficients on () on lag time. The individual apparent diffusion coefficients for the slow (C) and fast (D) modes are shown as a function of inverse lag time. The data points and error bars are derived from the average and SE of the mean values determined from experimental replicates, respectively. The Dtrue values extracted from the y intercepts are annotated on the figures, and the number in parentheses represents the uncertainty in the least significant digit as given by the SE of the mean from experimental replicates. (C) R2 values for each fit are 0.9991, 0.9984, and 0.9710 for FL-BamA-PAmCherry, ΔP1 BamA-PAmCherry, and ΔP12 BamA-PAmCherry, respectively. An extra sum-of-squares F test to compare the y intercepts was performed and yielded a p value of 0.044 for the of FL-BamA and ΔP1 BamA, 0.026 for FL-BamA and ΔP12 BamA, and 0.086 for ΔP1 BamA and ΔP12 BamA. (D) R2 values for each fit are 0.9941, 0.9529, and 0.9817 for FL-BamA-PAmcherry, ΔP1 BamA-PAmCherry, and ΔP12 BamA-PAmCherry, respectively. An extra sum-of-squares F test to compare the y intercepts was performed and yielded a p value of 0.20 for the of FL-BamA and ΔP1 BamA, 0.31 for FL-BamA and ΔP12 BamA, and 0.70 for ΔP1 BamA and ΔP12 BamA. To see this figure in color, go online.

Analysis of and as a function of lag time was once again performed to derive the true diffusion coefficient associated with each diffusive mode (Fig. 3 C–D; Table 1). FL-BamA displayed a diffusive mode consistent with immobility ( = 0.0001 ± 0.0005 μm2/s). Interestingly, ΔP1 BamA (0.0013 ± 0.0006 μm2/s) and ΔP12 BamA (0.003 ± 0.001 μm2/s) displayed the nonzero values that were significantly faster than FL-BamA’s upon statistical analysis (p < 0.050; Table S6) (Fig. 3 C). It has been reported by Kim et al. (14) that deletion of POTRA domains 1 or 2, although tolerated in E. coli, results in outer membrane defects and substantially lower density of OMPs in the outer membrane. This reduced crowding may explain the enhanced baseline diffusion of ΔP1 and ΔP12 BamA mutants and provides supporting evidence that promiscuous protein-protein interactions play an important role in the diffusion of OMPs (62,63).

The values for ΔP1 BamA (0.007 ± 0.004 μm2/s) and ΔP12 BamA (0.006 ± 0.003 μm2/s) are somewhat higher than that of FL-BamA, but the differences are not statistically significant (p ≥ 0.20; Table S6). They remain relatively low when compared to the other OMPs, indicating their diffusion is still slower than that of OmpLA or the isolated BamA barrel. We interpret this difference as reflecting the collective slowing effects of POTRAs 3–5 interacting with the BAM lipoprotein subunits and the peptidoglycan wall limiting their . Consistent with the data obtained for the MSC18 strain, the FL-BamA remains indistinguishable from immobile. Taken together, these results imply that all POTRA domains in BamA modulate BAM’s diffusive behavior, with POTRAs 3–5 mediating interactions with the BAM lipoproteins and peptidoglycan wall and POTRA’s 1 and 2 likely contacting additional cellular structures.

The SecYEG translocon diffuses more similarly to OMPs than monomeric IMPs

If a trans-envelope supercomplex of the SecYEG translocon and BAM were to facilitate OMP biogenesis, we hypothesized that Sec would be observed diffusing as slowly as BAM in at least one mode. SecYEG diffusion has been studied in vitro (64), yet it remains to be examined in vivo with the full potential for interactions in the cell envelope. To this end, the cytosolic N terminus of SecE was tagged with PAmCherry using previously employed fusion construct architecture (65). Importantly, this construct was reported to be capable of complementing depletion of native SecE, indicating that the fusion was functional and capable of forming SecYEG channels. For comparison of SecYEG to a diffusing monomeric IMP, the transmembrane enzyme PgpB was also tagged on the cytosolic side (C terminus) and all these constructs were analyzed by spt-PALM.

The histograms of Dapp derived from single tracks (Fig. 4 A) indicate that PgpB diffused faster than the OMPs in this study (Fig. 2 A and 3 A). This was an expected result, due to the less viscous nature of the phospholipid IM compared to the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-containing OM (66). However, the histogram of SecE’s Dapp indicate that SecE diffused slowly, with a median Dapp = ∼0.006 μm2/s, comparable to those of OMPs (Fig. 2 A). CCDF analysis further illustrates the differential behavior of SecYEG as both modes of PgpB’s diffusion ( = 0.018 ± 0.002 μm2/s, = 0.08 ± 0.02 μm2/s) were significantly faster than SecE’s ( = 0.014 ± 0.002 μm2/s, = 0.029 ± 0.004 μm2/s) (Fig. 4 B). PgpB was also observed in Dfast more frequently (%fast = 41% ± 5%) than SecYEG (%fast = 30% ± 3%) (Table S3). Similarly, the true diffusion coefficients (0.001 ± 0.002 μm2/s) and (0.005 ± 0.001 μm2/s) are substantially lower for SecE than PgpB ( = 0.0028 ± 0.0008 μm2/s, = 0.039 ± 0.004 μm2/s; Fig. 4 C–D), and once again similar to the Dtrue for OMPs (Fig. 2 C–D). PgpB displays a relatively high , in agreement with the concept that this parameter is defined by the lipid environment and the crowding of the membrane environment. In conclusion, SecE diffuses much more slowly than a monomeric IMP and more similar to OMPs in both of its modes.

Figure 4.

The Sec translocon diffuses much more slowly than a typical IMP. (A) Histogram showing the measured apparent diffusion coefficients (Dapp) for SecE and PgpB. Median depicted as black line. Data shown on a log10 scale. KS tests indicated a p value of <0.0001 between SecE (n = 878 tracks) and PgpB (n = 730 tracks) and a p value of 0.030 between SecE and BamA. (B) Complementary cumulative probability distributions of single-step square displacements for IMP constructs. The black lines represent the best fits to the sum of two exponentials. (C and D) Dependence of the apparent diffusion coefficients on () on lag time. The individual apparent diffusion coefficients for the slow (C) and fast (D) modes are shown as a function of inverse lag time. The data points and error bars are derived from the average and SE of the mean values determined from experimental replicates, respectively. The Dtrue values extracted from the y intercepts are annotated on the figures, and the number in parentheses represents the uncertainty in the least significant digit as given by the SE of the mean from experimental replicates. (C) R2 values for each fit are 0.9947 and 0.9943 for SecE and PgpB, respectively. An extra sum-of-squares F test to compare the y intercepts was performed and yielded a p value of 0.031 for the of SecE and PgpB. (D) R2 values for each fit are 0.9715 and 0.9828 for SecE and PgpB, respectively. An extra sum-of-squares F test to compare the y intercepts was performed and yielded a p value of 0.0003 for the of SecE and PgpB. To see this figure in color, go online.

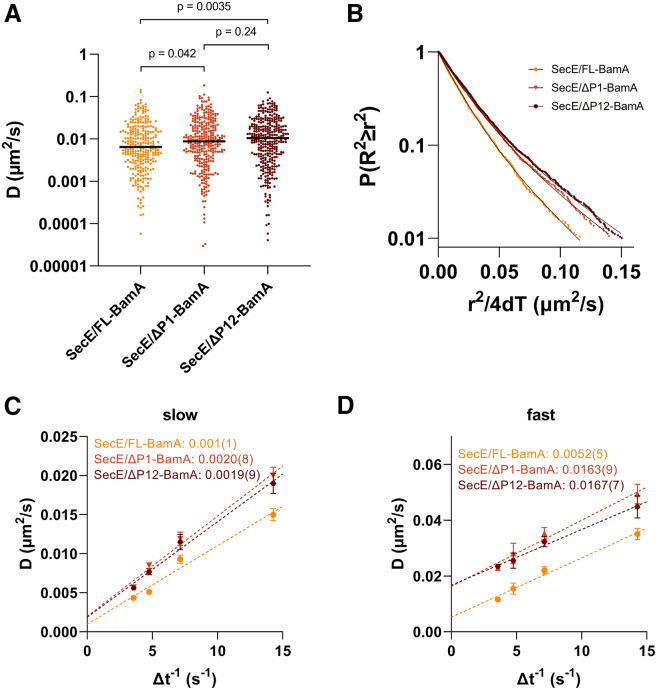

Deletion of BamA POTRA domains 1–2 results in faster SecYEG diffusion

The data presented above are consistent with the existence of a trans-envelope SecYEG-BAM assembly. Putative interactions between SecYEG and BAM have been proposed to be mediated by POTRA domains 1 and 2 (20,21,22,23), located most proximal to the inner membrane. This model thus predicts that deletion of BamA POTRA1 or POTRA 1–2 would disrupt the SecYEG-BAM interactions and result in faster SecYEG diffusion. To test this hypothesis, we expressed a PAmCherry-SecE construct in JCM166 cells (where endogenous BamA is depleted) complemented with full length, ΔP1, and ΔP12 BamA (no fluorescent tags) to yield the strains SecE/FL-BamA, SecE/ΔP1-BamA, and SecE/ΔP12-BamA. Additionally, PgpB-PAmCherry expressed in the same BamA backgrounds (PgpB/FL-BamA, PgpB/ΔP1-BamA, and PgpB/ΔP12-BamA) were tested to control for any nonspecific effects of POTRA deletion on IMP diffusion.

The histogram of Dapp values derived from the MSDs from individual tracks (median Dapp = ∼0.006 μm2/s; Fig. 5 A) showed a similar diffusion for SecE/FL-BamA to SecE in the MC4100 strain (median Dapp = ∼0.006 μm2/s, Fig. 4 A). Therefore, the changes in expression of BamA (chromosomal gene vs. plasmid borne) did not significantly affect SecE’s diffusion. Strikingly, SecE diffused faster upon deletion of BamA’s POTRA 1 (median Dapp = ∼0.009 μm2/s) or both POTRA’s 1 and 2 (Dapp = ∼0.010 μm2/s) (Fig. 5 A). Furthermore, CCDF fitting of single-step (70 ms) squared displacements (Fig. 5 B) indicate a faster diffusion for SecE/ΔP1-BamA ( = 0.020 ± 0.001 μm2/s, = 0.049 ± 0.004 μm2/s) and SecE/ΔP12-BamA ( = 0.0190 ± 0.0006 μm2/s, = 0.045 ± 0.004 μm2/s) with respect to SecE/FL-BamA ( = 0.0149 ± 0.0008 μm2/s, = 0.035 ± 0.002 μm2/s). The fraction observed in slow and fast modes was similar for all three constructs (Table S3). The SecE was found to be not significantly different in the three BamA backgrounds (SecE/FL-BamA = 0.001 ± 0.001 μm2/s, SecE/ΔP1-BamA = 0.0020 ± 0.0008 μm2/s, SecE/ΔP12-BamA = 0.0019 ± 0.0009 μm2/s), suggesting that the inner membrane environment was not altered by BamA POTRA deletions (Fig. 5 C). Conversely, values for SecE/ΔP1-BamA (0.0163 ± 0.009 μm2/s) and SecE/ΔP12-BamA (0.0167 ± 0.007 μm2/s) were similar and both significantly faster than that of SecE/FL-BamA (0.0052 ± 0.0005 μm2/s, p ≤ 0.013; Table S6). This indicates that the diffusion of SecE increased after slowing interactions were disrupted by the POTRA deletions. Importantly, the diffusion of PgpB was unaffected by these BamA POTRA deletions (Fig. S5), indicating that the POTRA deletions do not result in changes in inner membrane fluidity or protein content. The of SecE in ΔP1-BamA and ΔP12-BamA backgrounds remains slower than that of PgpB in the same backgrounds (0.0371 ± 0.0008 and 0.0363 ± 0.0006 μm2/s, respectively). This is likely due to SecYEG’s larger size (15 transmembrane helices vs. six in PgpB) and associations with ribosomes and/or other translocation factors (4,7,17). These results show that deletion of distal POTRA domains (proximal to the inner membrane) leads to an increase in the SecYEG translocon’s diffusion consistent with the SecYEG-BAM trans-periplasmic model. Deletion of POTRA1 is sufficient to cause this outcome.

Figure 5.

POTRA deletion increases Sec diffusion. (A) Histogram showing the measured apparent diffusion coefficients (Dapp) for SecE/FL-BamA, SecE/ΔP1-BamA and SecE/ΔP12-BamA. Median depicted as black line. Data shown on a log10 scale. KS tests indicated a p value of 0.042 between SecE/FL-BamA (n = 494 tracks) and SecE/ΔP1-BamA (n = 493 tracks), a p value of 0.0035 between SecE/FL-BamA and SecE/ΔP12-BamA (n = 591 tracks), and a p value of 0.24 between SecE/ΔP1-BamA and SecE/ΔP12-BamA. (B) Complementary cumulative probability distributions of single-step square displacements for Sec constructs. The black lines represent the best fits to the sum of two exponentials. (C and D) Dependence of the apparent diffusion coefficients on () on lag time. The individual apparent diffusion coefficients for the slow (C) and fast (D) modes are shown as a function of inverse lag time. The data points and error bars are derived from the average and SE of the mean values determined from experimental replicates, respectively. The Dtrue values extracted from the y intercepts are annotated on the figures, and the number in parentheses represents the uncertainty in the least significant digit as given by the SE of the mean from experimental replicates. (C) R2 values for each fit are 0.9737, 0.9863, and 0.9875 for SecE/FL-BamA, SecE/ΔP1-BamA, and SecE/ΔP12-BamA, respectively. An extra sum-of-squares F test to compare the y intercepts was performed and yielded p values of 0.49 for the of SecE/FL-BamA and SecE/ΔP1-BamA, 0.52 for SecE/FL-BamA and SecE/ΔP12-BamA, and 0.93 for SecE/ΔP1-BamA and SecE/ΔP12-BamA. (D) R2 values for each fit are 0.9861, 0.9793, and 0.9907 for SecE/FL-BamA, SecE/ΔP1-BamA, and SecE/ΔP12-BamA, respectively. An extra sum-of-squares F test to compare the y intercepts was performed and yielded a p value of 0.013 for the of SecE/FL-BamA and SecE/ΔP1-BamA, 0.0039 for SecE/FL-BamA and SecE/ΔP12-BamA, and 0.87 for SecE/ΔP1-BamA and SecE/ΔP12-BamA. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

OmpLA is a freely diffusing OMP with no known tethering interactions that would inhibit its diffusion in the E. coli. outer membrane. In this study, its diffusion was confirmed to be of the same magnitude as other OMPs of a similar unbound nature when studied in live cells (34,63). Comparably, PgpB is a freely diffusing IMP that has no known interactions with other cellular structures. Its diffusion was also observed here to mirror that of other membrane proteins (67). However, one of the main conclusions from SPT experiments is that, in cell membranes (as opposed to reconstituted model membranes), the diffusion cannot be described simply as isotropic Brownian motion. Instead, multiple non-Brownian diffusive modes are observed, including confined, tethered, and directed diffusion in addition to an immobile (during the time frame of the experiment) mode. Furthermore, transitions between modes is observed in most cases (for a discussion of diffusion modes see refs. (68) or (69)). We consistently observe two diffusion modes in all the proteins tested. The mode characterized by the is indistinguishable from zero and we thus ascribe it to an immobile mode, likely due to transient interactions of the molecules with largely immobile cellular structures, such as membrane protein clusters (70,71), or cell-wall-interacting proteins (72,73,74,75). Conversely, we attribute the to diffusion dominated by the effects of membrane fluidity, transmembrane domain size, and interactions with other mobile proteins in the form of oligomers or mobile complexes.

BamA was shown to diffuse slower than OmpLA, even proving to be essentially immobile in the time frame of our experiments when considering only its true motion separated from localization error. Upon removal of its POTRA domains, however, the BamA barrel also diffused similarly to a typical OMP. Evidently, the POTRA domains facilitate interactions that restrict the mobility of the BAM complex. The most obvious BamA interactions are the contacts with the other BAM subunits. The lipoprotein BAM subunits (BamBCDE) interact with the inner leaflet of the outer membrane primarily through a small N-terminal lipid anchor. Therefore, they have reduced membrane contacts compared to transmembrane OMPs and would thus be expected to cause less frictional drag than transmembrane OMPs. Moreover, a recent study calculated a 2D median diffusion coefficient about three times higher for an outer membrane lipoprotein than for the full-length BamA constructs in this study (29). Therefore, we would not expect the lipoprotein members of the BAM complex to contribute much frictional drag to BamA to substantially slow its diffusion. However, BamA has been reported to interact with the peptidoglycan wall (61). Isolating interactions with the BAM subunits and the cell wall is difficult due to both occurring through the essential POTRA domains 3–5 (6). Nevertheless, the for both ΔP1 and ΔP12 remained significantly lower (extra sum-of-squares F test p value of 0.031 and 0.015 with the of OmpLA, respectively) than the unbound OMPs despite their lower OMP density, suggesting that peptidoglycan or the BAM subunits restrict diffusion. On the other hand, our experiments showed no measurable difference in BAM diffusion along the cell axis where the proportion of mature and nascent peptidoglycan is variable (Fig. S6). Recent work supports a model where BamA preferentially binds mature peptidoglycan, which is most abundant at the cell poles, inhibiting BamA’s activity (61). Although mature peptidoglycan may bind and inhibit BAM, our tracking data suggest this interaction has no dramatic diffusion dynamic consequences.

The POTRA domains of BamA have been reported to crosslink with periplasmic domains of the inner transmembrane proteins associated with the SecYEG translocon to form a trans-periplasmic assembly (20) as well as indirectly via an interaction mediated by SurA (23). Consistent with this idea, the full-length BamA fusions diffuse more slowly than the POTRA deletion mutants, which could be due to disrupted trans-periplasmic contacts. Their effect may be estimated as the difference between the immobile of FL-BamA and the slow yet mobile of ΔP1 and ΔP12. Furthermore, it is intriguing that SecE, a component of the putative SecYEG-BAM assembly, diffuses substantially slower than the IMP PgpB (Fig. 4) and at a similar rate to the BAM complex (Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test p = 0.030 for SecE and BAM (MSC18 strain), KS test p = 0.10 for SecE and FL-BamA (JCM166 strain)). It is also possible that the relatively slow diffusion of the SecYEG translocon is due to interaction with other partners, such as ribosomes or translocation accessory proteins. Strikingly, however, we observed the of SecE to increase significantly with the deletion of either one or two of the POTRA domains of BamA that are closest to the inner membrane (Fig. 5 D, p values of 0.013 for SecE/FL-BamA and SecE/ΔP1-BamA and 0.0039 for SecE/FL-BamA and SecE/ΔP12-BamA). This provides tantalizing evidence that the SecYEG translocon interacts with full-length BamA in wild-type E. coli. It may be expected that disruption of BamA interactions with SecYEG by POTRA deletions would also result in faster diffusion of BAM. Although the of ΔP1-BamA and ΔP12-BamA appear somewhat faster that of FL-BamA, their differences do not achieve statistical significance (Fig. 3 D). We suggest that this is due to the lower fluidity of the LPS-containing outer membrane having a dominant effect on the diffusion coefficients, making the disruption of a link to the inner membrane SecYEG less apparent. Furthermore, the faster SecE diffusion in the POTRA deletions is not due to an indirect effect on the inner membrane fluidity as diffusion of PgpB is unaffected by the deletions (Fig. S5). Taken together, these results are consistent with a trans-envelope SecYEG-BAM assembly model that is also supported by results in independent laboratories (20,21,22,23). It is worth noting, however, that some estimates of the distance between the inner and outer membranes may suggest that a direct interaction between BAM and SecYEG may be difficult (for a review, see ref (76)). It is thus possible that additional, yet-to-be-discovered periplasmic components are required for the SecYEG-BAM interaction.

Although there is evidence of interaction between Sec and BAM, their diffusion was not identical. In addition to translocating nascent OMPs, the SecYEG complex translocates soluble periplasmic proteins and mediates insertion of IMPs (77). Therefore, a continuous direct coupling of diffusion between SecYEG and BAM would not necessarily be expected. Alternatively, a stable and constant interaction could still occur between BAM and Sec even when Sec is translocating a non-OMP protein. It is possible that a complex across two membranes could yield different observed diffusion speeds for the membrane components reflecting the different membrane viscosities. Further diffusion and co-localization studies in live cells examining SecYEG mutants and their interactions would provide new insight into these models.

Conclusions

3D super-resolution imaging and SPT are still at the forefront of biophysical tools required to understand membrane protein dynamics and interactions. Using double-helix point-spread function tracking, we characterized the diffusive behavior of the BAM and SecYEG complexes as well as other E. coli membrane proteins in live cells. This work provided new insights into the scale and frequency of the nanoscale diffusion of OMPs. Furthermore, the CCDF analysis performed here establishes a precedent in accounting for the effect of positional uncertainty on the observed mobility in live-cell 3D SPT. The method outlined in this paper can serve as a platform for 3D localization or tracking of any bacterial membrane protein and could be expanded to multi-color microscopy as well.

The results presented here demonstrate that wild-type OMPs diffuse with a bimodal behavior: a that is indistinguishable from immobility once positional error is taken into account and a second mode that is extremely slow (<0.025 μm2/s) yet named to differentiate it from the immobile mode. The POTRA domains of BamA facilitate interactions that completely immobilize the BAM complex. When removed, the BamA barrel gains mobility similar to that of OmpLA. Deleting the distal POTRA domains of BamA raises the diffusion speed of the Dslow mode of the BAM complex but not to the levels of free OMPs, consistent with the proposed interaction of POTRA’s 3–5 with the peptidoglycan wall. The faster diffusion of these POTRA deletion mutants may be due to the reduced efficiency of OMP biogenesis that consequently lowers OMP density, but it is also consistent with the model that these domains facilitate interactions with the SecYEG complex in the inner membrane. Also consistent with this hypothesis, the diffusion of SecE was much slower than that of the IMP PgpB and was on the same scale as that of BamA. Importantly, SecE was observed to diffuse faster upon the deletion of a single or two BamA POTRA domains. This supports a model where the SecYEG and BAM complexes interact in vivo to form a trans-periplasmic assembly to facilitate OMP biogenesis. Nevertheless, further confirmation from direct live-cell co-localization experiments is needed.

Author contributions

S.U., conceptualization, methodology, software, investigation, formal analysis, visualization, writing original draft/review & editing; J.W.T., methodology, software; D.K.S., methodology, formal analysis, writing – review & editing; M.C.S., conceptualization, formal analysis, writing – review & editing, supervision, funding acquisition.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sandra I. Metzner for the original engineering of the MSC18 cell strain. The imaging work was performed at the BioFrontiers Institute Advanced Light Microscopy Core (RRID: SCR_018302). Super-resolution microscopy was performed on a Nikon Ti-E microscope supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. We are indebted to Warren Colomb and Scott Gaumer at Double Helix Optics, Inc., for extensive advice in hardware usage (SPINDLE and Phase Masks) as well as method development and localization data processing with the 3DTRAX software. This work was supported in part by a National Institute of General Medical Sciences Signaling and Cellular Regulation Training Grant no. T32 GM008759 to S.U. as well as a National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant GM127462 to M.C.S. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Editor: Dylan Myers Owen.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2023.10.017.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Nikaido H. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003;67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulz G.E. Transmembrane beta-barrel proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 2003;63:47–70. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(03)63003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hegde R.S., Bernstein H.D. The surprising complexity of signal sequences. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006;31:563–571. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rapoport T.A. Protein translocation across the eukaryotic endoplasmic reticulum and bacterial plasma membranes. Nature. 2007;450:663–669. doi: 10.1038/nature06384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selkrig J., Leyton D.L., et al. Lithgow T. Assembly of beta-barrel proteins into bacterial outer membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1843:1542–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagan C.L., Silhavy T.J., Kahne D. beta-Barrel membrane protein assembly by the Bam complex. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011;80:189–210. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061408-144611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Driessen A.J.M., Nouwen N. Protein translocation across the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:643–667. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061606.160747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knowles T.J., Scott-Tucker A., et al. Henderson I.R. Membrane protein architects: the role of the BAM complex in outer membrane protein assembly. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:206–214. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noinaj N., Gumbart J.C., Buchanan S.K. The beta-barrel assembly machinery in motion. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017;15:197–204. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ricci D.P., Silhavy T.J. The Bam machine: a molecular cooper. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1818:1067–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gatsos X., Perry A.J., et al. Lithgow T. Protein secretion and outer membrane assembly in Alphaproteobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008;32:995–1009. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00130.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voulhoux R., Tommassen J. Omp85, an evolutionarily conserved bacterial protein involved in outer-membrane-protein assembly. Res. Microbiol. 2004;155:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gatzeva-Topalova P.Z., Walton T.A., Sousa M.C. Crystal structure of YaeT: conformational flexibility and substrate recognition. Structure. 2008;16:1873–1881. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S., Malinverni J.C., et al. Kahne D. Structure and function of an essential component of the outer membrane protein assembly machine. Science. 2007;317:961–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1143993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knowles T.J., Jeeves M., et al. Henderson I.R. Fold and function of polypeptide transport-associated domains responsible for delivering unfolded proteins to membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;68:1216–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruiz N., Kahne D., Silhavy T.J. Advances in understanding bacterial outer-membrane biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;4:57–66. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holland I.B. Translocation of bacterial proteins--an overview. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1694:5–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sklar J.G., Wu T., et al. Silhavy T.J. Defining the roles of the periplasmic chaperones SurA, Skp, and DegP in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2473–2484. doi: 10.1101/gad.1581007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vuong P., Bennion D., et al. Misra R. Analysis of YfgL and YaeT interactions through bioinformatics, mutagenesis, and biochemistry. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:1507–1517. doi: 10.1128/JB.01477-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alvira S., Watkins D.W., et al. Collinson I. Inter-membrane association of the Sec and BAM translocons for bacterial outer-membrane biogenesis. Elife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.60669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlson M.L., Stacey R.G., et al. Duong Van Hoa F. Profiling the Escherichia coli membrane protein interactome captured in Peptidisc libraries. Elife. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.46615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranava D., Yang Y., et al. Ieva R. Lipoprotein DolP supports proper folding of BamA in the bacterial outer membrane promoting fitness upon envelope stress. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.67817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y., Wang R., et al. Chang Z. A Supercomplex Spanning the Inner and Outer Membranes Mediates the Biogenesis of beta-Barrel Outer Membrane Proteins in Bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:16720–16729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.710715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krainer G., Gracia P., et al. Schlierf M. Slow Interconversion in a Heterogeneous Unfolded-State Ensemble of Outer-Membrane Phospholipase A. Biophys. J. 2017;113:1280–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan S., Yang C., Zhao X.S. Affinity of Skp to OmpC revealed by single-molecule detection. Sci. Rep. 2020;10 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71608-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thoma J., Sapra K.T., Müller D.J. Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy of Transmembrane beta-Barrel Proteins. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2018;11:375–395. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anchem-061417-010055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watkins D.W., Williams S.L., Collinson I. A bacterial secretosome for regulated envelope biogenesis and quality control? Microbiology (Read.) 2022;168:168. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.001255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uphoff S., Reyes-Lamothe R., et al. Kapanidis A.N. Single-molecule DNA repair in live bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:8063–8068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301804110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szczepaniak J., Holmes P., et al. Kleanthous C. The lipoprotein Pal stabilises the bacterial outer membrane during constriction by a mobilisation-and-capture mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1305. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15083-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niu L., Yu J. Investigating intracellular dynamics of FtsZ cytoskeleton with photoactivation single-molecule tracking. Biophys. J. 2008;95:2009–2016. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.128751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Consoli E., Luirink J., den Blaauwen T. The Escherichia coli Outer Membrane beta-Barrel Assembly Machinery (BAM) Crosstalks with the Divisome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms222212101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oddershede L., Dreyer J.K., et al. Berg-Sørensen K. The motion of a single molecule, the lambda-receptor, in the bacterial outer membrane. Biophys. J. 2002;83:3152–3161. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75318-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothenberg E., Sepúlveda L.A., et al. Golding I. Single-virus tracking reveals a spatial receptor-dependent search mechanism. Biophys. J. 2011;100:2875–2882. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spector J., Zakharov S., et al. Ritchie K. Mobility of BtuB and OmpF in the Escherichia coli outer membrane: implications for dynamic formation of a translocon complex. Biophys. J. 2010;99:3880–3886. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bosch P.J., Kanger J.S., Subramaniam V. Classification of dynamical diffusion states in single molecule tracking microscopy. Biophys. J. 2014;107:588–598. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Casadaban M.J. Transposition and fusion of the lac genes to selected promoters in Escherichia coli using bacteriophage lambda and Mu. J. Mol. Biol. 1976;104:541–555. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu T., Malinverni J., et al. Kahne D. Identification of a multicomponent complex required for outer membrane biogenesis in Escherichia coli. Cell. 2005;121:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warner L.R., Gatzeva-Topalova P.Z., et al. Sousa M.C. Flexibility in the Periplasmic Domain of BamA Is Important for Function. Structure. 2017;25:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foo Y.H., Spahn C., et al. Kenney L.J. Single cell super-resolution imaging of E. coli OmpR during environmental stress. Integr. Biol. 2015;7:1297–1308. doi: 10.1039/c5ib00077g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subach F.V., Patterson G.H., et al. Verkhusha V.V. Photoactivatable mCherry for high-resolution two-color fluorescence microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:153–159. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altinoglu I., Merrifield C.J., Yamaichi Y. Single molecule super-resolution imaging of bacterial cell pole proteins with high-throughput quantitative analysis pipeline. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:6680. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43051-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bach J.N., Giacomelli G., Bramkamp M. Sample Preparation and Choice of Fluorophores for Single and Dual Color Photo-Activated Localization Microscopy (PALM) with Bacterial Cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017;1563:129–141. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6810-7_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stracy M., Lesterlin C., et al. Kapanidis A.N. Live-cell superresolution microscopy reveals the organization of RNA polymerase in the bacterial nucleoid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E4390–E4399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507592112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carr A.R., Ponjavic A., et al. Lee S.F. Three-Dimensional Super-Resolution in Eukaryotic Cells Using the Double-Helix Point Spread Function. Biophys. J. 2017;112:1444–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lasker K., von Diezmann L., et al. Shapiro L. Selective sequestration of signalling proteins in a membraneless organelle reinforces the spatial regulation of asymmetry in Caulobacter crescentus. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:418–429. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0647-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Misiura A., Shen H., et al. Landes C.F. Single-Molecule Dynamics Reflect IgG Conformational Changes Associated with Ion-Exchange Chromatography. Anal. Chem. 2021;93:11200–11207. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c01799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang D., Agrawal A., et al. Schwartz D.K. Enhanced information content for three-dimensional localization and tracking using the double-helix point spread function with variable-angle illumination epifluorescence microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017;110 doi: 10.1063/1.4984133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang D., Wu H., Schwartz D.K. Three-Dimensional Tracking of Interfacial Hopping Diffusion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017;119:268001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.268001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pavani S.R.P., Thompson M.A., et al. Moerner W.E. Three-dimensional, single-molecule fluorescence imaging beyond the diffraction limit by using a double-helix point spread function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:2995–2999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900245106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Badieirostami M., Lew M.D., et al. Moerner W.E. Three-dimensional localization precision of the double-helix point spread function versus astigmatism and biplane. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010;97 doi: 10.1063/1.3499652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grover G., Pavani S.R.P., Piestun R. Performance limits on three-dimensional particle localization in photon-limited microscopy. Opt. Lett. 2010;35:3306–3308. doi: 10.1364/OL.35.003306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shcherbakova D.M., Sengupta P., et al. Verkhusha V.V. Photocontrollable fluorescent proteins for superresolution imaging. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2014;43:303–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-051013-022836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y., Raymo F.M. Photoactivatable fluorophores for single-molecule localization microscopy of live cells. Methods Appl. Fluoresc. 2020;8 doi: 10.1088/2050-6120/ab8c5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qian H., Sheetz M.P., Elson E.L. Single particle tracking. Analysis of diffusion and flow in two-dimensional systems. Biophys. J. 1991;60:910–921. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82125-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dekker N. Outer-membrane phospholipase A: known structure, unknown biological function. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;35:711–717. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bouchaud J.P., Georges A. Anomalous Diffusion in Disordered Media - Statistical Mechanisms, Models and Physical Applications. Phys. Rep. 1990;195:127–293. doi: 10.1016/0370-1573(90)90099-N. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feder T.J., Brust-Mascher I., et al. Webb W.W. Constrained diffusion or immobile fraction on cell surfaces: a new interpretation. Biophys. J. 1996;70:2767–2773. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79846-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kues T., Peters R., Kubitscheck U. Visualization and tracking of single protein molecules in the cell nucleus. Biophys. J. 2001;80:2954–2967. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76261-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kastantin M., Schwartz D.K. Distinguishing positional uncertainty from true mobility in single-molecule trajectories that exhibit multiple diffusive modes. Microsc. Microanal. 2012;18:793–797. doi: 10.1017/S1431927612000438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gunasinghe S.D., Shiota T., et al. Lithgow T. The WD40 Protein BamB Mediates Coupling of BAM Complexes into Assembly Precincts in the Bacterial Outer Membrane. Cell Rep. 2018;23:2782–2794. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mamou G., Corona F., et al. Vollmer W. Peptidoglycan maturation controls outer membrane protein assembly. Nature. 2022;606:953–959. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04834-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kleanthous C., Rassam P., Baumann C.G. Protein-protein interactions and the spatiotemporal dynamics of bacterial outer membrane proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2015;35:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rassam P., Copeland N.A., et al. Kleanthous C. Supramolecular assemblies underpin turnover of outer membrane proteins in bacteria. Nature. 2015;523:333–336. doi: 10.1038/nature14461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koch S., Seinen A.B., et al. Driessen A.J.M. Single-molecule analysis of dynamics and interactions of the SecYEG translocon. FEBS J. 2021;288:2203–2221. doi: 10.1111/febs.15596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brandon L.D., Goehring N., et al. Goldberg M.B. IcsA, a polarly localized autotransporter with an atypical signal peptide, uses the Sec apparatus for secretion, although the Sec apparatus is circumferentially distributed. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;50:45–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schavemaker P.E., Boersma A.J., Poolman B. How Important Is Protein Diffusion in Prokaryotes? Front. Mol. Biosci. 2018;5:93. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2018.00093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kumar M., Mommer M.S., Sourjik V. Mobility of cytoplasmic, membrane, and DNA-binding proteins in Escherichia coli. Biophys. J. 2010;98:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saxton M.J., Jacobson K. Single-particle tracking: applications to membrane dynamics. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1997;26:373–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.26.1.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saxton M.J. In: Fundamental Concepts in Biophysics. Jue T., editor. Humana Press; 2009. 'Single Particle Tracking. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cassidy C.K., Himes B.A., et al. Zhang P. Structure and dynamics of the E. coli chemotaxis core signaling complex by cryo-electron tomography and molecular simulations. Commun. Biol. 2020;3:24. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0748-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sourjik V., Armitage J.P. Spatial organization in bacterial chemotaxis. EMBO J. 2010;29:2724–2733. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Egan A.J.F. Bacterial outer membrane constriction. Mol. Microbiol. 2018;107:676–687. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ginez L.D., Osorio A., et al. Poggio S. Establishment of a Protein Concentration Gradient in the Outer Membrane Requires Two Diffusion-Limiting Mechanisms. J. Bacteriol. 2019;201 doi: 10.1128/JB.00177-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Godlewska R., Wiśniewska K., et al. Jagusztyn-Krynicka E.K. Peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein (Pal) of Gram-negative bacteria: function, structure, role in pathogenesis and potential application in immunoprophylaxis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009;298:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sandoz K.M., Moore R.A., et al. Heinzen R.A. beta-Barrel proteins tether the outer membrane in many Gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Microbiol. 2021;6:19–26. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-00798-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lithgow T., Stubenrauch C.J., Stumpf M.P.H. Surveying membrane landscapes: a new look at the bacterial cell surface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023;21:502–518. doi: 10.1038/s41579-023-00862-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Veenendaal A.K.J., van der Does C., Driessen A.J.M. The protein-conducting channel SecYEG. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1694:81–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.