Highlights

-

•

Oxaliplatin (OXA) is one of the most common chemotherapy drugs in cancer therapy.

-

•

The various kinds of nanoparticles, including lipid-, polymeric-, metal-, and carbon-based nanostructures, have been introduced for OXA delivery in cancer therapy.

-

•

Smart nanostructures, including pH-, redox-, light-, and thermo-sensitive nanostructures, have been designed for OXA delivery and cancer therapy.

Keywords: Oxaliplatin, Targeted delivery, Chemoresistance, Synergistic cancer therapy, Gene and drug delivery

Abstract

As a clinically approved treatment strategy, chemotherapy-mediated tumor suppression has been compromised, and in spite of introducing various kinds of anticancer drugs, cancer eradication with chemotherapy is still impossible. Chemotherapy drugs have been beneficial in improving the prognosis of cancer patients, but after resistance emerged, their potential disappeared. Oxaliplatin (OXA) efficacy in tumor suppression has been compromised by resistance. Due to the dysregulation of pathways and mechanisms in OXA resistance, it is suggested to develop novel strategies for overcoming drug resistance. The targeted delivery of OXA by nanostructures is described here. The targeted delivery of OXA in cancer can be mediated by polymeric, metal, lipid and carbon nanostructures. The advantageous of these nanocarriers is that they enhance the accumulation of OXA in tumor and promote its cytotoxicity. Moreover, (nano)platforms mediate the co-delivery of OXA with drugs and genes in synergistic cancer therapy, overcoming OXA resistance and improving insights in cancer patient treatment in the future. Moreover, smart nanostructures, including pH-, redox-, light-, and thermo-sensitive nanostructures, have been designed for OXA delivery and cancer therapy. The application of nanoparticle-mediated phototherapy can increase OXA's potential in cancer suppression. All of these subjects and their clinical implications are discussed in the current review.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Cancer is among the most malignant diseases around the world with an increasing trend in its incidence rate. The cancer cells are characterized with their abnormal proliferation and metastasis as well as development of therapy resistance. There are two problems in cancer including diagnosis and treatment. The tumor is asymptomatic in early stages and therefore, most of the cancer patients are diagnosed in advanced stages, when the tumor has aggressive behavior and can develop therapy resistance. The treatment of cancer has also faced difficulties, resulting from several factors. The changes and interactions in the tumor microenvironment (TME) can accelerate tumor progression and may develop therapy resistance [1]. The current therapeutics for cancer range from immunotherapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgical resection (in early stages) and targeted therapy. The immunotherapy has revolutionized the process of cancer therapy and it can be utilized for both solid and hematological tumors, causing long-term responses [2,3]. However, a problem in cancer immunotherapy is long-term and remarkable immune responses only a minor proportion of patients [4]. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy suffer from resistance and adverse impacts. Furthermore, the targeted therapies, especially application of nanoparticles has been accelerated in the recent years, empowering cancer therapy [5,6]. The natural products are promising compounds in cancer therapy, but they suffer from poor bioavailability. The delivery of natural products by nanocarriers can improve their potential in cancer suppression. The resveratrol-loaded nanoparticles can suppress oral cancer through dully disruption of cancer invasion and angiogenesis [7]. Due to resistance of cancer cells to the therapy, new strategies were utilized, especially combination cancer therapy. The combinational therapy allows to increase sensitivity of cancer cells to drugs through application of drugs with different mechanisms of actions. Veliparib is an PARP inhibitor that its combination with curcumin can cause synergistic impact in downregulation of PI3K/Akt and disrupting NECTIN-4-mediated angiogenesis [8]. Moreover, combinational therapy can increase the apoptosis induction in tumor cells [9]. For instance, resveratrol stimulates DNA damage to mediate apoptosis in cancer. The combination of resveratrol and olaparib can accelerate DNA damage through suppression of PARP1/BRCA1 [10]. The curcumin has been beneficial for apoptosis induction in cancer. A combination of curcumin and olaparib can downregulate BER cascade to increase DNA damage and apoptosis in cancer [11]. In spite of exploring several methods for the treatment of cancer, the patients still have problems in the clinical level, urging scientists to develop new strategies for tumor suppression. Although significant challenges and barriers are present in the way of cancer chemotherapy, it is still among the most common ways in clinical trials to treat patients and improve their prognosis. OXA is a third-generation platinum compound in tumor suppression. There was a 20-year gap from the year of discovery to its approval for clinical application (1976–1996). OXA has been beneficial in the monotherapy of tumors, and poly-chemotherapy can improve its anticancer activity [12]. The main way for administration of OXA is intravenous injection, which has a short initial phase of distribution followed by drug removal that is a long process and may be observed in the kidney after 48 h of administration [13]. Peripheral neuropathy can result from the use of OXA in cancer patients. Moreover, passive diffusion is involved in the cellular uptake of OXA, but it has been shown that active transport can increase its internalization [14]. When OXA enters cells, it can bind to DNA, RNA, and proteins [15]. OXA creates bindings with DNA to prevent the replication of DNA and its transcription. Compared to cisplatin, OXA generates fewer DNA adducts, but it provides higher cytotoxicity against tumor cells [16]. In spite of the novel action mechanism of OXA and its ability in tumor suppression, the emergence of resistance has decreased its potential in cancer suppression. Epigenetic alterations accelerate tumorigenesis, and changes in the expression level of non-coding RNAs can lead to OXA resistance [17,18]. To be more specific, recent studies have evaluated the exact signaling networks participating in the OXA resistance of colorectal cancer (CRC). The down-regulation of circ-FLI1 in CRC leads to a reduction in the progression of colon tumor, and this is of importance in overcoming OXA resistance via impairing dyskeratosis congenita [19]. ELK3 promotes RNASEH2A expression, triggering OXA resistance in gliomas [20]. LncRNA NEF participates in suppressing the MEK/ERK axis to reverse EMT and OXA resistance in the CRC [21]. Moreover, the transfer of DNA and other molecules by exosomes can result in OXA resistance [22]. Therefore, complicated interactions among molecular pathways can result in OXA resistance, and therapeutic approaches can be developed for reversing this condition [22], [23], [24].

Although the interactions occurring at the molecular level can change the chemotherapy response of cancer and, in most cases, lead to drug resistance, more attention should be directed towards solutions for overcoming chemoresistance than improving knowledge in the field of chemoresistance. Overall, three kinds of strategies can be developed for reversing drug resistance. The first strategy is to use combination cancer therapy, which means the co-application of two drugs with various anticancer activities. The anti-cancer compounds with pleiotropic function are suggested in cancer therapy due to the wide networks participating in tumorigenesis. Therefore, natural products can be considered as promising compounds in tumor eradication. However, since drugs still have poor bioavailability, more progress should be made for combination cancer therapy with drugs. In a more recent effort, genes and chemotherapy drugs are used together in synergistic cancer therapy. Similar to co-drug administration, gene and drug co-application suffer from poor bioavailability. Therefore, increasing evidence supports the fact that it is better to utilize nanoparticles for cancer chemotherapy. The reason is that nanoparticles mediate the site-specific delivery of drugs and genes in cancer therapy [25,26]. In the current review, the focus is on the role of nanostructures for targeted delivery of OXA in cancer therapy. This comprehensive review will provide state-of-the-art experiments related to using nanoparticles for OXA delivery and enhancing its potential in cancer therapy and reversing chemotherapy resistance.

Nanomedicine in cancer therapy

After cardiovascular diseases, cancer is a leading cause of death. According to the statistics, it mainly affects US citizens aged 85 and younger [27]. Although significant achievements have caused surprising results in pre-clinical studies in cancer therapy, there is no profound impact on the cancer patients, and there is still a long way to go in this case. After the failures in the treatment of cancer patients, multiple examples of nanomedicine application and its promising results in cancer therapy were provided. In 2008, David and colleagues demonstrated that siRNA-loaded nanostructures can be systemically injected for the cancer therapy [28]. In 1971, the war against cancer was started, and from that time until now, there has been significant improvement in cancer therapy by coordinating and understanding environmental and molecular reasons for disease pathogenesis [29]. However, there is still much room for understanding the precise differences among normal and tumor cells that should be highlighted in future studies, and if such differences are not understood, it is impossible to counter and suppress cancer. The project to sequence the human genome was completed in 2001 [30]. With subsequent improvements in data sequencing, it was found that improving the biological aspects of cancer can greatly help cancer therapy. After the completion of human genome sequencing, the new trend was directed towards the role of nanoscience in disease therapy, and nanoparticles are defined as structures with a size of 1–100 nm. Nanomedicine is an interdisciplinary field with high application in disease therapy. The first application of nanomedicine is in bioimaging and biosensing, and if molecular imaging of living cells is provided, it can increase the efficacy of cancer therapy. Quantum dots (QDs) with fluorescent activity have been employed recently for the purpose of imaging, and due to their unique size of 1–10 nm and photochemical and photophysical features, they can be used as important agents and materials for imaging [31], [32], [33], [34]. However, most applications of nanoparticles are in the field of cancer chemotherapy [35]. For multiple decades, combination therapy has been considered a promising field in clinics, and several principles should be considered. In the first place, the drugs that are going to be used together should be approved for clinical application, and then their mechanisms of action should be different. Moreover, there should be no cross-resistance, and they should exert synergistic impact in cancer therapy [36], [37], [38]. Due to the challenges of combination cancer therapy, it is suggested to use nanocarrier-based methods for this purpose, in which one drug or two drugs can be loaded onto nanoparticles. Regarding the purpose of nanostructures for cargo delivery or imaging, various kinds of nanostructures have been developed with distinct features. Liposomes, micelles, polymeric nanoparticles, solid lipid nanomaterials, and inorganic materials are among the nanostructures employed for the purpose of cancer therapy [39]. Each of them can be used for drug delivery, and changes in their composition can affect their physico-chemical properties and their ability for drug delivery. Sometimes, the molecular weight of drugs is low, and they also suffer from poor bioavailability; in this case, their conjugation with antibodies is suggested to accelerate tumor suppression [40]. Imaging and drug delivery are not the only fields in which nanocarriers can be used, and it has been reported that nanoparticles can be employed for immunotherapy, gene delivery, and overcoming drug resistance in cancer. In the next sections, the role of nanostructures for specific delivery of OXA is discussed.

Nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery: beyond OXA

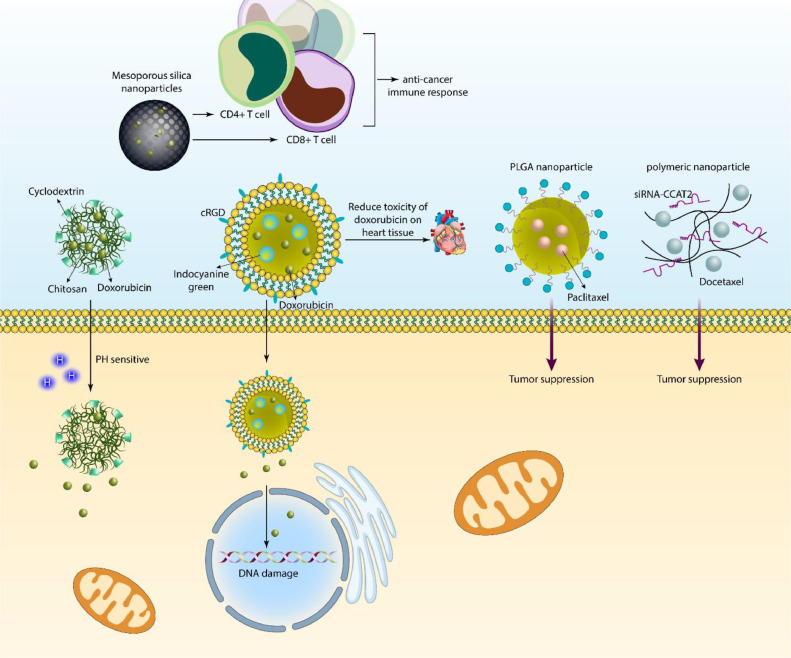

Regarding the increased cases of therapy failure, the nanoparticle utilization for cancer chemotherapy has increased. Since the number of cancer patients is increasing and it may trespass cardiovascular disease in the next few years, it is absolutely necessary to find new solutions for overcoming chemoresistance in cancer patients. Fol-LMSO nanostructures are capable of delivering doxorubicin in breast tumor treatment, and the benefit of these nanostructures is to provide hyperthermia along with chemotherapy drug delivery [41]. An improvement in cancer drug delivery is to make them smart to some of the changes in tumors, such as pH. β-cyclodextrin/chitosan nanostructures are able to mediate the pH-sensitive release of doxorubicin in cancer therapy, and their zeta potential (+20 mV) demonstrates their high stability. Furthermore, these nanoparticles induce the prolonged release of doxorubicin, and due to their antioxidant activity, they may diminish the adverse impacts of chemotherapy drugs on other tissues [42].The ligand functionalization has improved the potential of nanoparticles in cancer therapy. Moreover, some of the nanostructures, such as mesoporous silica nanoparticles, have large pores in their structures that can be used for loading a high amount of doxorubicin into them, followed by their modification with TRAIL to increase selectivity. Moreover, such drug-loaded nanoparticles are able to induce DCs and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and mediate an anticancer immune response [43].

Two aspects of chemotherapy drugs should be highlighted: first, they mediate DNA damage in reducing the viability of tumor cells, and simultaneously, they may cause toxicity in normal cells. The liposomal nanostructures were loaded with indocyanine green, and then they were used for the delivery of doxorubicin. At the next step, they were modified with cRGD to selectively target cancer cells. It was found that such nanostructures not only elevate DNA damage in tumor cells but also, by providing targeted delivery, can reduce the toxicity of doxorubicin on heart tissue [44]. Noteworthy, polymeric nanostructures such as PLGA nanoparticles are also beneficial in cancer therapy. Then, paclitaxel was loaded on PLGA nanoparticles, and it was shown that such nanostructures preferentially accumulate at the tumor site to suppress cancer progression [45,46]. Cancer death mainly results from metastasis, and its suppression can provide new insight for cancer therapy and improve the prognosis of patients. Albumin-paclitaxel nanostructures have been modified with peptides, and their final size is in the range of 100–200 nm, which means that they can impair the invasion of cancer and increase the potential of chemotherapy [47].

In addition, some of the drugs have been co-loaded on nanoparticles to impair tumorigenesis. The co-loading of paclitaxel and 5-fluorouracil on lipid-encapsulated mesoporous silica nanostructures and then their modification with folic acid These nanoparticles targeted breast tumor cells overexpressing the folate receptor, and this receptor was responsible for their internalization in breast tumor cells. Such targeted delivery is of importance for improving the ability to achieve synergistic cancer suppression [48]. Furthermore, dextran nanostructures can be employed for the purpose of co-delivering etoposide and l-asparaginase to release drugs in a pH-sensitive manner, to increase internalization in cancer cells, and to suppress tumorigenesis [49]. Furthermore, co-delivery of chemotherapy drugs and genetic tools can be provided in tumor therapy, and polymeric nanoparticles can be utilized for docetaxel and siRNA-CCAT2 delivery to disrupt lung carcinogenesis [50]. Therefore, nanoparticles can mediate sustained delivery of chemotherapy drugs in potentiating cancer therapy, and their surface modification enhances preferential accumulation at the tumor site (Fig. 1) [51], [52], [53].

Fig. 1.

The role of nanostructures for delivery of chemotherapy drugs. The nanocarriers can utilize multiple methods for the suppression of cancer. The nanoparticles can improve the internalization of current chemotherapy drugs to accelerate tumor suppression. Moreover, nanoparticles mediate co-delivery of chemotherapy drugs and genes in synergistic cancer therapy. Even the anti-tumor immune responses including increase in the number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells can be induced by nanocarriers. Moreover, nanoparticles respond to certain stimuli in tumor microenvironment including pH and their functionalization with ligands and peptides such as cRGD can improve potential in targeting cancer cells and inducing DNA damage.

Targeted delivery and co-delivery approaches

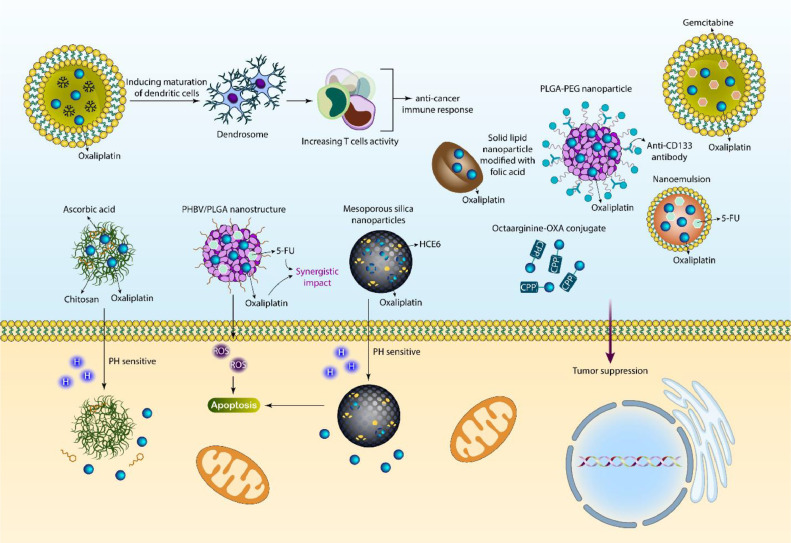

The nanostructures are widely applied for the delivery of OXA in cancer therapy. The reasons for the poor delivery of OXA can be summarized into several factors, but the most important one is that OXA suffers from poor bioavailability and its cytotoxicity against tumor cells decreases due to a lack of specific delivery. Some may consider increasing the concentration of OXA by increasing its levels in serum and suppressing cancer progression, but it is impossible to enhance the concentration of OXA beyond its optimal level due to the fact that when levels of OXA increase, it can lead to cytotoxicity in normal cells, and they can tolerate decreases. Moreover, nanostructures are suggested to be completely vital for the purpose of combination cancer therapy, and by application of nanoparticles, it is possible to accelerate cytotoxicity against cancer. The aim of the current section is to provide an in-depth discussion of using nanomaterials for OXA delivery and along with other drugs or genes in tumor suppression. Chitosan (CS) is one of the natural polysaccharides that can be derived from chitin through its N-deacetylation, and this biomaterial has shown promising features including biocompatibility, biodegradability, and adjustable mechanical and physico-chemical features [54], [55], [56]. Moreover, CS has demonstrated other vital pharmacological characteristics such as antibacterial, antioxidant, and antitumor effects [57]. Recent studies have shown that CS-based nanoparticles can be used for drug [58] or gene [25] delivery in tumorigenesis suppression. Moreover, PEGylation of CS nanoparticles is performed to increase their potential for cancer chemotherapy and delivery [59]. A recent study has prepared CS-based nanostructures for the co-delivery of OXA and ascorbic acid in breast tumor treatment. The diameter of the nanoparticles was in the range of 157–261 nm, and their zeta potential was +22 to +4 mV. They demonstrated high entrapment efficiency and mediated the sustained release of cargo in suppressing tumorigenesis. Moreover, these nanoparticles release drugs in response to pH 5.5 [60].

5-Flourourouracil (5-FU) is one of the most common chemotherapy drugs for colon cancer, and this pyrimidine analog suppresses thymidylate synthesis for the purpose of cancer therapy [61,62]. The short half-life of 5-FU and its poor membrane permeability and distribution in both normal and cancer cells have been among the drawbacks of this chemotherapy drug [63], [64], [65], [66]. Moreover, high activity of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) as a drug efflux pump can result in a reduction in the cytotoxicity of 5-FU and the development of resistance [67]. For improving 5-FU-induced cancer suppression, it is usually used with other compounds. One of the newest advances is the delivery of 5-FU by nanoparticles for effective cancer therapy and overcoming drug resistance [68,69]. The PHBV/PLGA nanostructures have been fabricated for the co-delivery of OXA and 5-FU in colon tumor treatment, and they accelerate ROS levels to stimulate apoptosis. Furthermore, they have high biocompatibility, and such co-delivery synergistically suppresses tumorigenesis [70].

Sometimes, peptides can be conjugated to OXA for targeted delivery of colorectal cancer. A cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) octaarginine-OXA conjugate is able to deliver into colon tumor cells and reduce the IC50 value of OXA [71]. PLGA-PEG nanoparticles were modified with antibodies, and they were used for the delivery of OXA in CRC therapy. They had particle sizes of 207 and 185 nm, and modification with anti-CD133 antibodies enhanced delivery towards tumor cells [72]. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) were introduced in the 1990s, and they were considered alternative nanoparticles for liposomal nanostructures, polymeric nanostructures, and nanoemulsions [73]. Moreover, polymeric nanoparticles can lead to acute and chronic toxicity [74]. Therefore, SLNs were considered biocompatible and promising nanocarriers for OXA delivery in CRC therapy. Then, nanoparticles were modified with folic acid, and their particle size was 146.2 nm. Such OXA-loaded SLNs displayed high anticancer activity [75]. Although the purpose of the current study is to understand the role of nanoparticles in the delivery of OXA in cancer therapy, microparticles, microbubbles, and even films can be utilized for the delivery of OXA and other compounds in cancer chemotherapy [[76], [77], [78]].

At the clinical level, OXA can be used in combination with 5-FU in CRC therapy. The FDA organization in the USA has confirmed the application of OXA along with 5-FU and leucovorin in cancer therapy [79,80]. However, both OXA and 5-FU display low bioavailability upon intravenous administration, and their intestinal membrane permeability is low. Therefore, their long-term application through oral administration is not suggested [[81], [82], [83]]. Nanoemulsions have been developed for the co-delivery of OXA and 5-FU in cancer therapy with a particle size of 20.3 nm and a zeta potential of −4.65 mV. These nanoemulsions demonstrated high permeability through a Caco-2 cell monolayer, with an approximately 4-fold increase in permeability compared to the drug alone. These nanoparticles increased the oral bioavailability of drugs, and in an animal model, they suppressed tumorigenesis [84]. Noteworthy, clinical application is mainly dependent on the biocompatibility of nanostructures. Therefore, increasing evidence suggests using liposomes and their smart and stimuli-sensitive forms for OXA delivery in cancer therapy and improving the potential of OXA in chemotherapy [85,86]. Furthermore, when liposomes deliver OXA to tumor sites, due to their biodegradability, they display no toxicity on the body, and therefore, they are promising nanocarriers in this case [87].

Since monotherapy has not been beneficial for cancer suppression, studies have focused on polychemotherapy. Based on the guidelines of the American Cancer Society, a combination of OXA and irinotecan has been considered a first-line treatment for tumors, and for OXA and irinotecan, the dosages of 85 mg/m2 and 200 mg/m2 are recommended. Owing to distinct characteristics of liposomes including their safety, small particle size, biodegradability, and ability to encapsulate hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs, liposomes have been applied for the co-delivery of OXA and gemcitabine in carcinogenesis suppression. The liposomes demonstrated particle sizes less than 200 nm, and their size distribution was uniform. Moreover, liposomes are capable of releasing drugs synchronously, allowing the synergistic effects of drugs. They show preferential accumulation at tumor cells, and such nanoformulation is interesting for the purpose of cancer therapy [88].

Mainly, experiments have emphasized on the co-delivery of OXA with other anticancer drugs, but it appears that one of the newest developments may be loading a photosensitizer and OXA drug in cancer therapy. OXA and HCE6 (photosensitizer) were loaded on mesoporous silica nanostructures, and they released OXA at an acidic pH. The drug-loaded nanostructures stimulated apoptosis in tumor cells and increased the expression level of autophagic factors. Moreover, they can reduce tumor growth in vivo [89]. Moreover, they can reduce tumor growth in vivo [87]. Moreover, OXA-loaded nanostructures can trigger immune responses in cancer cells. Dendrosomes can be derived from mature dendritic cells, and then a PDEA polymer and OXA prodrug combination can be loaded into dendrosomes. After blood stream circulation, such OXA-loaded nanoparticles can enter the tumor microenvironment and induce the maturation of dendritic cells to increase T cell activity, mediating immunogenic cell death and reducing tumorigenesis [90]. Hence, chemotherapy and immunotherapy combination synergistically suppresses tumorigenesis. The microemulsions have been prepared by nanoprecipitation technique, and then OXA and folinic acid have been loaded in nanocarriers. The CRC and liver tumor can be sensitized to 5-FU to induce immunogenic cell death. Moreover, such nanoparticles stimulate apoptosis and immunogenic cell death, reducing tumorigenesis. Moreover, an in vivo experiment revealed the efficacy of these nanocarriers for reducing tumor size [91]. According to these studies, the development of nanocarriers accelerates OXA-induced tumor suppression ability [[92], [93], [94], [95], [96]]. Moreover, OXA can be loaded along with natural products such as resveratrol on nanocarriers to mediate poly-chemotherapy (Fig. 2, Table 1) [97].

Fig. 2.

The delivery of OXA and also co-delivery in cancer chemotherapy. The targeted delivery of OXA can enhance activity and infiltration of T cells to augment the anti-cancer immune responses. The chitosan-based nanoparticles can release chitosan and ascorbic acid in response to pH for cancer removal. Moreover, PLGA/PHBV nanoparticles respond to ROS to induce apoptosis after OXA release. The co-delivery of OXA with other kinds of drugs such as gemcitabine and 5-flourouracil by nanoparticles has been evaluated in cancer therapy. The functionalization of nanoparticles with folic acid increases their potential in targeted delivery of drugs.

Table 1.

Nanostructure-mediated OXA delivery.

| Nanvehicle | Drug | Cancer type | Remark | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CuS@UiO-66-NH2 | OXA | Colorectal cancer | Higher cytotoxicity compared to OXA alone | [98] |

| Thermosensitive liposomes | OXA | Breast cancer | Complete release of drug at 42 °C High cytotoxicity and retention time |

[99] |

| Erythrocyte-delivered photoactivatable oxaliplatin nanoprodrug | OXA | Breast cancer | Increased antitumor activity Inducing anticancer immune response Reducing tumorigenesis |

[100] |

| PEGylated multi-walled carbon nanotubes | OXA | Colorectal cancer | Loading efficiency of 43.6% Controlled release of drug High cytotoxicity |

[101] |

| Polysaccharide based functionalized polymeric micelles | OXA Vanillic acid |

Colon cancer | Synergistic impact and targeting different molecular pathways such as mTOR/Ras pathway, HIF-1α inhibition, NF-ĸB, and Nrf2 | [102] |

| Self-assembled nanoscale coordination polymers | OXA Gemcitabine |

Pancreatic cancer | Inhibition of cellular uptake by MPS system Increased half-life and blood circulation time Synergsitic impact |

[103] |

| Poly(Ethylene Glycol)- b-Poly(D,L-Lactide) Nanoparticles | OXA | – | OXA as hydrophobic compound is absorbed into core-corona interface Increasing PLA block length reduces drug loading Encapsulation efficiency of 76% |

[104] |

| Oxaliplatin-loaded nanoemulsion containing Teucrium polium L. essential oil | OXA | Colon cancer | Increasing ROS levels to induce apoptosis in cancer cells | [105] |

| oxaliplatin(iv) prodrug-based supramolecular self-delivery nanocarrier | OXA | Colorectal cancer | Cargo release in response to redox status Increased intracellular accumulation in tumor cells High anticancer activity |

[106] |

| Electrospun polylactide nanofibers | OXA 5-flouroracil |

Colorectal cancer | Reducing tumor growth Increasing survival time of animal model |

[107] |

| An ultrasound responsive microbubble-liposome conjugate | OXA Irinotecan |

Pancreatic cancer | UTMD accelerates release of drug from nanostructures and this combination therapy leads to synergistic impact | [108] |

| Gold nanoparticles | OXA | Colon cancer | Functionalization with PEG High cellular uptake and anticancer activity |

[109] |

| Mesoporous silica nanoparticles | OXA | Liver cancer | Enhanced cellular uptake by cancer cells Concentration into lysosomes and endosomes High antitumor activity Increased DNA binding activity |

[110] |

| PEGylated PAMAM dendrimers | OXA | Cervical cancer | Loading efficiency of 84.63% Lack of burst release and drug release in a sustained manner Increasing killing potential |

[111] |

| Micelles | OXA | Colorectal cancer | Elimination of cancer stem cells | [112] |

| Oral nanoemulsions | OXA | Melanoma | Increased anticancer immunity Promoting tumor antigen uptake Stimulation of dendritic cells |

[113] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks | OXA | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Chemodynamic therapy by exposure of composites into irradiation to mediate phototherapy and chemotherapy | [114] |

| Magnetic nanocarriers of pectin | OXA | Pancreatic cancer | Zeta potential of −30.5 demonstrating high biocompatibility of nanocarriers Drug encapsulation efficiency of 55.2% Controlled release and high cytotoxicity |

[115] |

| PEG-coated cationic liposomes | OXA | Murine solid tumor | Deep penetration into enlarged intra-tumoral interstitial space Effective drug delivery Suppressing tumorigenesis |

[116] |

| PEGylated liposome | OXA | – | Increasing intracellular distribution Apoptosis induction |

[117] |

Smart nanostructures

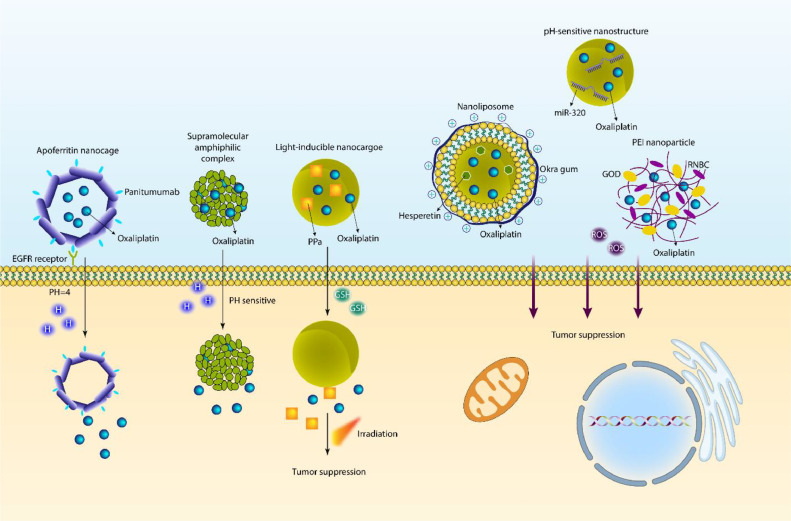

The multifunctional and smart nanocarriers have revolutionized the field of cancer therapy. pH-sensitive nanoparticles are widely utilized in tumor suppression. The tumor microenvironment (TME) displays unique properties including increased temperature, changes in levels and activity of enzymes, dysregulation of redox status, and a reduced pH level near 6.5 [118]. There are several reasons for the low pH level of TME, but the most prominent one is the preference of tumor cells for aerobic glycolysis instead of oxidative phosphorylation for ATP production [[119], [120], [121], [122]]. Regarding this property, pH-sensitive nanostructures have been developed for drug release in acidic conditions [123]. The mechanism of pH-sensitive bonds can be based on protonable groups or acid-sensitive bonds [124,125]. Recently, the concept of protein cages has been interesting and includes ferritin, viral capsids, and heat shock proteins [126]. Ferritin is a protein for storing iron that can be found naturally in humans and other living organisms. Ferritin has 24 subunits, a molecular weight of 440 kDa, and a hollow sphere structure. Ferritin is known as a protein nanocage, and it has an internal diameter of 8 nm and an external diameter of 12 nm [[127], [128], [129]]. Recently, apoferritin nanocages with pH-sensitive activity have been designed for OXA delivery in CRC therapy. The PEG has been used as a linker in the structure of nanocarriers, and they have been functionalized with panitumumab for specific targeting of the EGFR receptor on the surface of tumor. At pH 7, there is no release of OXA, but at a pH level of 4, OXA release occurs, which results in a reduction in the progression of CRC cells. These nanocages demonstrate high accumulation in tumor tissue, and they can suppress tumor proliferation [130].

Due to the important function of pH-sensitive nanoparticles for OXA delivery, there has been interest in using such nanostructures for the co-delivery of OXA and other antitumor compounds to promote their specific release at the tumor site. Hesperetin is one of the anticancer agents, and its delivery by PEGylated gold nanoparticles [131] or PLGA nanostructures [132] has been beneficial in improving its cytotoxicity against tumor cells. The nanoliposomes have been designed using the thin film hydration method, and then they have been coated with okra gum so that the final nanostructure has a cationic feature. Then, OXA and hesperetin have been loaded on liposomes, and the final particle size is 145–175 nm. They have a zeta potential of −29 mV, and their EE for OXA and hesperetin is 66% and 98%, respectively. The modification of liposomes with cationic Okra gum improved the stability of liposomes, and this co-delivery exerted a synergistic impact on CRC suppression [133]. However, for improving the potential for drug delivery, studies have evaluated dual functionalized complexes for the purpose of OXA delivery in cancer therapy [134]. One of the newest advances in OXA delivery by nanoparticles is the provision of pH-sensitive nanostructures that are capable of OXA and microRNA (miRNA) co-delivery. miRNA-320 is a newly discovered molecule in cancer, and its low expression leads to enhancement in the growth and metastasis of breast tumor cells [135]. SOX4, FOXM1, and FOXQ1 are among the targets of miR-320 for purposes of cancer therapy [136,137]. Therefore, the function of miR-320 is pleiotropic, and if its delivery is mediated, it can suppress tumorigenesis. In a recent effort, pH-sensitive nanostructures have been prepared for the delivery of miR-320 and OXA in head and neck cancer treatment. In order to prevent peptide degradation, the surface of nanoparticles has been coated with a shield, and then, due to their pH-sensitive feature, the peptides are exposed when they are at the acidic pH of TME. These pH-sensitive nanostructures increased the cellular uptake of OXA and miR-320, and they mediate nucleus and cytoplasmic delivery of the cargo for effective cancer suppression. This co-delivery was beneficial in suppressing growth, metastasis, and overcoming chemoresistance due to modulation of NRP1/Rac1, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, GSK-3β/FOXM1/β-catenin, P-gp/MRPs, KRAS/Erk/Oct4/Yap1, and N-cadherin/Vimentin/Slug pathways [138].

Although hydrogels are not nanostructures, it is worth mentioning that they can be deployed for sustained pH-release of OXA in cancer therapy due to their high biocompatibility [139]. Furthermore, due to advances in the field of chemistry, different chemical complexes can be developed for pH-sensitive delivery of OXA in cancer therapy [140]. Various kinds of nano-scale delivery systems have been developed for cancer chemotherapy, including liposomes [[141], [142], [143]], polymeric nanostructures [[144], [145], [146]], hybrid nanomaterials (organic and inorganic materials) [[147], [148], [149]], and other methods [[150], [151], [152]]. The development of pro-drugs for the co-delivery of OXA with other anticancer agents and being responsive to stimuli are of importance in cancer therapy [153]. Doxorubicin (DOX) resistance is one of the newest emergency conditions in cancer because of the abnormal alterations in the genetic and epigenetic profile of tumor cells. When it is brought to the concept of bioengineering, it is believed that nanostructures, especially functionalized nanocarriers, can provide targeted delivery of DOX, improving its anticancer potential, and moreover, co-delivery of DOX with other antitumor compounds is of importance in cancer therapy. In a recent effort, a supramolecular amphiphilic complex has been designed for the preparation of an OXA-based prodrug to encapsulate DOX and provide an EPR effect. At the low pH level of lysosomes, these complexes release cargo in cancer therapy, and they have a superior capacity to penetrate through the cell membrane [153]. Another important factor for the development of smart nanocarriers is redox balance (reactive oxygen species, or ROS). In an effort, PEI nanoparticles have been developed for the delivery of OXA in cancer therapy, and they have been complexed with GOD and RNBC. When these redox-responsive nanoparticles accumulate in tumor cells, they are reduced to release RNase A, and a cytotoxic Pt(II) drug is developed. Then, DNA replication is suppressed by the RNase enzyme, and the way is paved for OXA to exert its anticancer activity [154].

These discussions revealed the role of endogenous stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for sustained delivery of drugs and other cargo in cancer therapy. Light-inducible nanocargoes (LINC) have been promising structures for controlled and spatiotemporal release of cargo in cancer therapy. The LINC can be employed for the purpose of immunogenic cell death (ICD) induction and to diminish the expression level of IDO-1. The nanostructures have been utilized for the delivery of OXA, photosensitizer pheophorbide A (PPa), and IDO-1 inhibitor NLG919 (termed as PN). The nanocarriers are responsive to GSH and release cargo in response to GSH levels. The interesting part is related to the prodrug OXA, which is light-responsive, and when irradiation occurs, it causes the synergistic impact of OXA and PPa-SH in triggering ICD and increasing anticancer immunity (Fig. 3) [155]. Therefore, smart nanostructures are beneficial for the purpose of OXA delivery in tumor suppression (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Stimuli-responsive nanoparticles in cancer chemotherapy. The emergence of stimuli-sensitive nanocarriers has revolutionized cancer therapy, since there are specific features in the tumor microenvironment including low pH levels and redox imbalance. The increase in GSH levels and decrease in pH levels can cause release of OXA from nanoparticles in cancer therapy.

Table 2.

The role of smart nanoparticles for OXA delivery in cancer therapy.

| Nanoparticle | Remark | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| pH-responsive nanoprodrugs combining a Src inhibitor and chemotherapy | pH-sensitive nanomicelles for delivery of OXA and masitinib in increasing anticancer immunity | [156] |

| Lipid-Coated CaCO3 Nanoparticles | pH-sensitive release of OXA Increasing blood circulation time Enhancing antitumor immunity |

[156] |

| PEGylated dendritic diaminocyclohexyl-platinum (II) conjugates | EPR effect Increased tumor accumulation Suppressing tumorigenesis in vivo |

[157] |

| Polymeric nanocomplex | Redox-responsive release of OXA and protein in synergistic cancer therapy | [154] |

| Light-Inducible Nanocargoes | Stimulation of ICD and enhancing anticancer immunity | [155] |

| Laser/GSH-Activatable Oxaliplatin/Phthalocyanine-Based Coordination Polymer Nanoparticles | A combination of chemotherapy and phototherapy to increase anticancer immunity | [158] |

| Magnetic Thermosensitive Cationic Liposome | Anti-lncRNA MDC1 and OXA co-delivery in synergistic cancer therapy | [159] |

Functionalized nanostructures

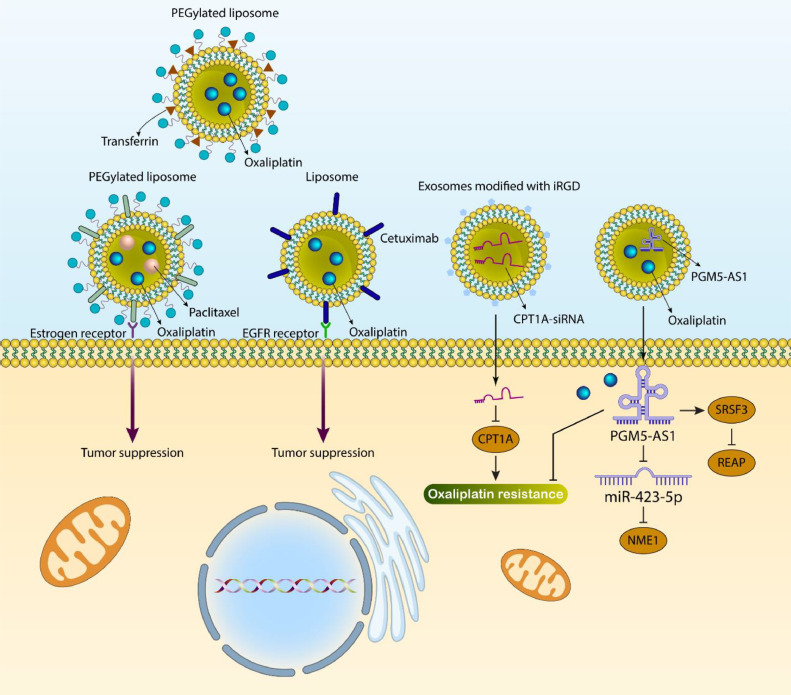

Notably, functionalization of nanostructures with ligand has been an essential part of targeting cancer cells in a specific way. A number of ligands, including lactoferrin [160], folate [161], and NGR peptide [162], have been utilized for the modification of liposomes to improve their targetability towards tumor cells. On the nucleus and cell membrane, there are estrogen receptors [163,164] that are involved in various biochemical and physiological mechanisms [165]. Estrogen receptors display upregulation in different kinds of tumors, such as breast [166], lung, gastric, and ovarian cancers [167,168], and they can be considered promising targets in cancer drug delivery. A recent experiment has developed PEGylated liposomes. Such estrogen-targeted PEGylated Liposomes have been prepared using the film hydration method, and they have been utilized for the co-delivery of OXA and paclitaxel. After internalization in tumor cells due to binding to the estrogen receptor, they released OXA and paclitaxel to suppress microtubule balance and mediate cell death [169]. In addition, estrogen-targeted PEGylated OXA-loaded liposomes have been used for the treatment of gastric cancer [170]. Cetuximab (CTX) as an antibody has emerged recently as a specific agent for the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and CRC cells mainly upregulate this receptor [171,172]. After the attachment of CTX to EGFR, internalization occurs and this receptor is suppressed. In addition, signals related to apoptosis induction are mediated, and subsequent activation of the immune system leads to tumor cell death [173]. In 65–70% of CRC cases, EGFR demonstrates an increase in expression [174,175]. After loading OXA in liposomes, they have been functionalized with CTX to selectively target the EGFR receptor in CRC cells, and such modification enhances cellular uptake by three times compared to conventional liposomes. Moreover, animal experiments highlighted the role of CTX-modified OXA-loaded liposomal nanoparticles in suppressing CRC progression [176]. In addition, transferrin-conjugated PEGylated liposomes can be used for OXA delivery in cancer therapy [177]. Therefore, modification of nanostructures with ligands significantly increases their potential for targeted delivery and cancer suppression. Moreover, modification with ligands does not increase the size of nanostructures, and they are still promising carriers for OXA in cancer chemotherapy [82,[178], [179], [180]].

Exosomes as new emerging structures in oxaliplatin delivery

Exosomes belong to extracellular vesicles, and their small size is less than 100 nm. They can carry bioactive molecules such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [181]. Recently, the function of exosomes in cancer has been of importance, and they could be secreted by macrophages and cancer cells to regulate tumorigenesis [182]. The bioengineered exosomes can be utilized for the delivery of OXA in cancer therapy. OXA and PGM5-AS1 can be co-loaded in exosomes for the purpose of colon cancer therapy. Increasing the expression level of PGM5-AS1 suppresses proliferation, metastasis, and OXA resistance in colon cancer. Co-delivery of OXA and PGM5-AS1 by exosomes leads to overcoming OXA resistance in colon tumors. Interestingly, after delivery of PGM5-AS1, it decreases REAP expression via recruiting SRSF3. Moreover, PGM5-AS1 sponges miR-423–5p to enhance NME1 expression [183]. It has been reported that high expression levels of CPT1A enhance FAO expression in mediating OXA resistance. The exosomes can be modified by iRGD to mediate selective targeting of colon tumor cells. The targeted delivery of CPT1A-siRNA by iRGD-functionalized exosomes leads to increased OXA sensitivity in colon tumors (Fig. 4) [184]. However, a few studies have focused on using exosomes in cancer therapy and reversing OXA resistance.

Fig. 4.

Ligand-modified nanoparticles and exosomes in OXA delivery. The functionalization of nanoparticles with ligands has been emerged as a promising strategy in cancer therapy. The unmodified nanoparticles improve the pharmacokinetic profile of OXA, but ligand-functionalized nanoparticles can specifically target the tumor cells due to overexpression of receptors. Moreover, functionalization can increase the internalization of nanoparticles in the tumor cells through endocytosis. The exosomes are also ideal carriers for OXA, since their biocompatibility is high and they can delivery cargo with high efficacy.

Current limitations of nanoparticles: pre-clinical and clinical insights

A major frontier in the cancer therapy is the development of multifunctional nanoparticles [185]. The pre-clinical studies have confirmed the efficacy of nanoparticles in cancer removal. In spite of significant studies evaluating nanoparticle-mediated cancer therapy, a few types of nanocarriers have been introduced into clinic. Hence, the current problems and limitations of nanoparticles for clinical utilization should be addressed [186]. The nanoparticles have differences in composition, size, surface charge, porosity and aggregation behavior, known as physico-chemical properties [187,188]. The significant alterations in the physico-chemical features make it difficult to understand mechanism of action and their characteristics before and after administration. The heterogeneity of nanostructures regarding to size, shape and mass is considered as polydispersity index (PDI). Even the partial changes in PDI and physico-chemical features of nanoparticles can change and determine the biocompatibility, toxicity and in vivo results [[189], [190], [191], [192]]. The safety concerns are of high importance for the nanoparticles due to their wide application and their impact on the human health and environment should be critically evaluated. The nanoparticles have a nano-scale size that is similar to the organelles or the biomolecules participating in the cellular signaling. The nanoparticles may interact negatively with the biological mechanisms. Therefore, the nanotoxicology field has been emerged and evaluating the toxicity concern of nanostructures before their clinical application is vital [190,193]. The comparison of toxicity rates among nano- and macro-materials is difficult. Moreover, toxicity evaluation of nanoparticles is similar to the classical drugs using same experiments, showing that current assays for evaluating toxicity of nanoparticles are not enough [194,195]. Regardless of the properties and biocompatibility, there are also regulatory issues regarding application of nanoparticles and they should be approved by FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA). The current problem is that FDA and EMA, among other agencies, have not still provided the specific criteria and guidelines for the drug-loaded nanoparticles. Recently, the FDA rules for the application of drug-loaded nanoparticles in clinic have been summarized [196]. In June 2014, the guidelines regarding the application of products having nanoparticles was released [197]. Accordingly, the nanostructures are defined as particles with at least one dimension and particle size of 1–100 nm. The materials with dimensions up to 1 μm with nano-properties can be also considered, if they demonstrate quantum impacts. Another issue is the manufacturing process of nanoparticles that is quite challenging and the current clinical and pre-clinical studies have been performed with a low amount of nanostructures. One of prominent problems in the clinical level is that when large-scale production occurs, the differences in the physico-chemical features are observed because of PDI of nanoparticles [198]. This may subsequently affect the efficacy of nanoparticles at the clinical level. Hence, the large-scale production of nanoparticles in industry should be tightly controlled to develop nanoparticles with favorable physico-chemical characteristics [199]. The clinical application of nanoparticles has been mainly based on diagnosis including utilization of ligand-receptor interactions for the early diagnosis of cancer or application of biomarkers for determining the best therapeutic option for the patients [200]. If the EPR effect of a patient is determined, it can be understood that how the cancer patients responds to the therapy and if the nanostructures can appropriately accumulate in the tumor site [201]. Therefore, the nanoparticles can revolutionize the precision medicine. However, there is still a long way for clinical regulation of immune system and gene editing by nanoparticles and their industrial production.

Conclusion and remarks

The first benefit of nanoparticles is that they can deliver OXA to tumor tissue in a very targeted way. This kind of delivery is important for two reasons. The first reason is that when smart and stimuli-sensitive nanoparticles are used for OXA delivery, they mediate cargo release exactly at the tumor site, and therefore, an increase in the cytotoxicity of drugs is observed. The second reason is that OXA has concentration-dependent toxicity, and such site-specific delivery prevents the accumulation of OXA in normal tissues and decreases side effects. The smart nanoparticles can be responsive to endogenous or exogenous stimuli. In the first type of nanocarrier, they can be developed in a way that is responsive to pH and redox, and in the exogenous-responsive nanoparticles, they can be sensitive to light and heat. In both cases, smart nanoparticles are promising factors for the purpose of cancer therapy, and if they are combined for the development of multifunctional nanocarriers, their efficacy in site-specific and precise release of drugs increases. The benefit of light-responsive nanocarriers is that they can mediate phototherapy along with chemotherapy to accelerate the process of cancer elimination. One of the most important benefits of nanoparticles is their ability to deliver OXA at the tumor site and enhance its internalization by tumor cells. Such increased cellular uptake promotes cytotoxicity against tumor cells, which is beneficial in preventing drug resistance in cancer cells. However, in most cases, polychemotherapy is preferred, and therefore, OXA is combined with other anticancer drugs for tumor suppression. Interestingly, nanoplatforms can mediate the co-delivery of drugs in synergistic cancer therapy. Furthermore, genes can be loaded on nanoplatforms to be delivered with OXA in cancer gene therapy or chemotherapy. However, there is no experiment about the delivery of OXA with CRISPR/Cas9 in cancer therapy. Furthermore, modification of nanoparticles with ligands and antibodies can increase selectivity toward tumor cells. However, there is no experiment about the modification of nanostructures with aptamers in cancer chemotherapy. Although different kinds of polymeric-, lipid-, and carbon-based nanomaterials have been used for OXA delivery [[202], [203], [204], [205]], there is little attention given to the use of metal nanoparticles in OXA delivery. Moreover, there is no experiment about the delivery of OXA by layered double hydroxide (LDH) nanostructures in cancer therapy.

The pre-clinical studies have focused on understanding the application of OXA-loaded nanoparticles in the treatment of cancer. The increase in cellular accumulation, co-delivery with drugs and genes, specific targeting of cancer cells, especially the ligand-functionalized nanocarriers and utilization of exosomes as new kind of structures for OXA delivery, are a number of benefits using nanostructures in OXA chemotherapy. However, the clinical application of current studies requires more investigation. Moreover, the type of nanoparticle utilized in clinical trial is of importance. Between the years 2002 and 2016, there has been an increase in the application of protein nanoparticles, but after that and between 2016 and 2021, there has been an increase in the application of liposomal nanostructures [206]. Therefore, among the various nanostructures used in OXA delivery, exosomes, liposomes and polymeric nanoparticles have the highest chance for application in treatment of cancer. The newest clinical trial product was Pfizer vaccine for COVID-19 that also utilized the liposomes for the mRNA delivery. The long-term safety and biocompatibility of liposomes have been recognized. Moreover, since exosomes can be obtained from the cells, their biocompatibility is high and if they are utilized in cancer therapy, they are not recognized as foreign bodies by immune cells. In the future, there is high possibility of using liposomes and exosomes for the delivery of OXA for treatment of cancer in clinical trials. However, the large-scale production of nanoparticles and determining the physico-chemical features of structures in the industrial range are still problems.

Funding

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mohsen Bagheri: Conceptualization. Mohammad Arad Zandieh: Data curation, Writing – original draft. Mahshid Daryab: Writing – review & editing. Seyedeh Setareh Samaei: Data curation, Writing – original draft. Sarah Gholami: Conceptualization. Parham Rahmanian: Conceptualization. Sadaf Dezfulian: Visualization, Investigation. Mahsa Eary: Visualization, Investigation. Aryan Rezaee: Writing – review & editing. Romina Rajabi: Data curation, Writing – original draft. Ramin Khorrami: Validation, Writing – review & editing. Shokooh Salimimoghadam: Visualization, Investigation. Peng Hu: Validation. Mohsen Rashidi: Supervision. Alireza Khodaei Ardakan: Supervision. Yavuz Nuri Ertas: Supervision. Kiavash Hushmandi: Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2023.101838.

Contributor Information

Mohsen Rashidi, Email: dr.mohsenrashidi@yahoo.com.

Alireza Khodaei Ardakan, Email: alirezakhodaei@hotmail.com.

Kiavash Hushmandi, Email: Houshmandi.Kia7@ut.ac.ir.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Rihawi K., Ricci A.D., Rizzo A., Brocchi S., Marasco G., Pastore L.V., Llimpe F.L.R., Golfieri R., Renzulli M. Tumor-associated macrophages and inflammatory microenvironment in gastric cancer: novel translational implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:3805. doi: 10.3390/ijms22083805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santoni M., Rizzo A., Kucharz J., Mollica V., Rosellini M., Marchetti A., Tassinari E., Monteiro F.S.M., Soares A., Molina-Cerrillo J., et al. Complete remissions following immunotherapy or immuno-oncology combinations in cancer patients: the MOUSEION-03 meta-analysis. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2023;72:1365–1379. doi: 10.1007/s00262-022-03349-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santoni M., Rizzo A., Mollica V., Matrana M.R., Rosellini M., Faloppi L., Marchetti A., Battelli N., Massari F. The impact of gender on the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer patients: the MOUSEION-01 study. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2022;170 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricci, A.D.; Rizzo, A.; Brandi, G. DNA damage response alterations in gastric cancer: knocking down a new wall. 2021, 17, 865–868. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Li Y., Fang H., Zhang T., Wang Y., Qi T., Li B., Jiao H. Lipid-mRNA nanoparticles landscape for cancer therapy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.1053197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kesharwani P., Ma R., Sang L., Fatima M., Sheikh A., Abourehab M.A.S., Gupta N., Chen Z.S., Zhou Y. Gold nanoparticles and gold nanorods in the landscape of cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer. 2023;22:98. doi: 10.1186/s12943-023-01798-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pradhan R., Chatterjee S., Hembram K.C., Sethy C., Mandal M., Kundu C.N. Nano formulated Resveratrol inhibits metastasis and angiogenesis by reducing inflammatory cytokines in oral cancer cells by targeting tumor associated macrophages. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2021;92 doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2021.108624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatterjee S., Sinha S., Molla S., Hembram K.C., Kundu C.N. PARP inhibitor Veliparib (ABT-888) enhances the anti-angiogenic potentiality of Curcumin through deregulation of NECTIN-4 in oral cancer: role of nitric oxide (NO) Cell. Signal. 2021;80 doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2020.109902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee S., Dhal A.K., Paul S., Sinha S., Das B., Dash S.R., Kundu C.N. Combination of talazoparib and olaparib enhanced the curcumin-mediated apoptosis in oral cancer cells by PARP-1 trapping. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2022;148:3521–3535. doi: 10.1007/s00432-022-04269-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinha S., Chatterjee S., Paul S., Das B., Dash S.R., Das C., Kundu C.N. Olaparib enhances the Resveratrol-mediated apoptosis in breast cancer cells by inhibiting the homologous recombination repair pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2022;420 doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2022.113338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molla S., Hembram K.C., Chatterjee S., Nayak D., Sethy C., Pradhan R., Kundu C.N. PARP inhibitor olaparib enhances the apoptotic potentiality of curcumin by increasing the DNA damage in oral cancer cells through inhibition of BER cascade. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2020;26:2091–2103. doi: 10.1007/s12253-019-00768-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashrafizadeh M., Zarrabi A., Hushmandi K., Hashemi F., Hashemi F., Samarghandian S., Najafi M. MicroRNAs in cancer therapy: their involvement in oxaliplatin sensitivity/resistance of cancer cells with a focus on colorectal cancer. Life Sci. 2020;256 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez-Balibrea E., Martínez-Cardús A., Ginés A., Ruiz de Porras V., Moutinho C., Layos L., Manzano J.L., Bugés C., Bystrup S., Esteller M. Tumor-related molecular mechanisms of oxaliplatin resistance. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015;14:1767–1776. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burger H., Loos W.J., Eechoute K., Verweij J., Mathijssen R.H., Wiemer E.A. Drug transporters of platinum-based anticancer agents and their clinical significance. Drug Resist. Updates. 2011;14:22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graham M.A., Lockwood G.F., Greenslade D., Brienza S., Bayssas M., Gamelin E. Clinical pharmacokinetics of oxaliplatin: a critical review. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:1205–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woynarowski J.M., Faivre S., Herzig M.C., Arnett B., Chapman W.G., Trevino A.V., Raymond E., Chaney S.G., Vaisman A., Varchenko M., et al. Oxaliplatin-induced damage of cellular DNA. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;58:920–927. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.5.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo Z.D., Wang Y.F., Zhao Y.X., Yu L.C., Li T., Fan Y.J., Zeng S.J., Zhang Y.L., Zhang Y., Zhang X. Emerging roles of non-coding RNAs in colorectal cancer oxaliplatin resistance and liquid biopsy potential. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023;29:1–18. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qi F.F., Yang Y., Zhang H., Chen H. Long non-coding RNAs: key regulators in oxaliplatin resistance of colorectal cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020;128 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu W., Jiang H., Li Y. Silencing circular RNA-friend leukemia virus integration 1 restrained malignancy of CC cells and oxaliplatin resistance by disturbing dyskeratosis congenita 1. Open Life Sci. 2022;17:563–576. doi: 10.1515/biol-2022-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mei Y., Chen D., He S., Ye J., Luo M., Wu Q., Huang Y. Transcription factor ELK3 promotes stemness and oxaliplatin resistance of glioma cells by regulating RNASEH2A. Horm. Metab. Res. 2023;55:149–155. doi: 10.1055/a-1981-3328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi C.J., Xue Z.H., Zeng W.Q., Deng L.Q., Pang F.X., Zhang F.W., Fu W.M., Zhang J.F. LncRNA-NEF suppressed oxaliplatin resistance and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer through epigenetically inactivating MEK/ERK signaling. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023 doi: 10.1038/s41417-023-00595-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z., Li Y., Mao R., Zhang Y., Wen J., Liu Q., Liu Y., Zhang T. DNAJB8 in small extracellular vesicles promotes Oxaliplatin resistance through TP53/MDR1 pathway in colon cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13:151. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-04599-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weng X., Liu H., Ruan J., Du M., Wang L., Mao J., Cai Y., Lu X., Chen W., Huang Y., et al. HOTAIR/miR-1277-5p/ZEB1 axis mediates hypoxia-induced oxaliplatin resistance via regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8:310. doi: 10.1038/s41420-022-01096-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu Q., Liu Y., Sun W., Song T., Jiang X., Zeng K., Zeng S., Chen L., Yu L. Blockade LAT1 mediates methionine metabolism to overcome oxaliplatin resistance under hypoxia in renal cell carcinoma. Cancers. 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/cancers14102551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashrafizadeh M., Delfi M., Hashemi F., Zabolian A., Saleki H., Bagherian M., Azami N., Farahani M.V., Sharifzadeh S.O., Hamzehlou S. Biomedical application of chitosan-based nanoscale delivery systems: potential usefulness in siRNA delivery for cancer therapy. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021;260 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.117809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirzaei S., Gholami M.H., Hashemi F., Zabolian A., Hushmandi K., Rahmanian V., Entezari M., Girish Y.R., Kumar K.S.S., Aref A.R. Employing siRNA tool and its delivery platforms in suppressing cisplatin resistance: approaching to a new era of cancer chemotherapy. Life Sci. 2021;277 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanco E., Hsiao A., Mann A.P., Landry M.G., Meric-Bernstam F., Ferrari M. Nanomedicine in cancer therapy: innovative trends and prospects. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1247–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis M.E., Zuckerman J.E., Choi C.H.J., Seligson D., Tolcher A., Alabi C.A., Yen Y., Heidel J.D., Ribas A. Evidence of RNAi in humans from systemically administered siRNA via targeted nanoparticles. Nature. 2010;464:1067–1070. doi: 10.1038/nature08956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawasaki E.S., Player A. Nanotechnology, nanomedicine, and the development of new, effective therapies for cancer. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2005;1:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venter J.C., Adams M.D., Myers E.W., Li P.W., Mural R.J., Sutton G.G., Smith H.O., Yandell M., Evans C.A., Holt R.A. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruchez M., Jr, Moronne M., Gin P., Weiss S., Alivisatos A.P. Semiconductor nanocrystals as fluorescent biological labels. Science. 1998;281:2013–2016. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith A.M., Gao X., Nie S. Quantum dot nanocrystals for in vivo molecular and cellular imaging. Photochem. Photobiol. 2004;80:377–385. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2004)080<0377:QDNFIV>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson S.A., Glod J., Arbab A.S., Noel M., Ashari P., Fine H.A., Frank J.A. Noninvasive MR imaging of magnetically labeled stem cells to directly identify neovasculature in a glioma model. Blood. 2005;105:420–425. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashrafizadeh M., Mohammadinejad R., Kailasa S.K., Ahmadi Z., Afshar E.G., Pardakhty A. Carbon dots as versatile nanoarchitectures for the treatment of neurological disorders and their theranostic applications: a review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;278 doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2020.102123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang R.X., Wong H.L., Xue H.Y., Eoh J.Y., Wu X.Y. Nanomedicine of synergistic drug combinations for cancer therapy–strategies and perspectives. J. Control. Release. 2016;240:489–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waterhouse D.N., Gelmon K.A., Klasa R., Chi K., Huntsman D., Ramsay E., Wasan E., Edwards L., Tucker C., Zastre J., et al. Development and assessment of conventional and targeted drug combinations for use in the treatment of aggressive breast cancers. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2006;6:455–489. doi: 10.2174/156800906778194586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tardi P., Johnstone S., Harasym N., Xie S., Harasym T., Zisman N., Harvie P., Bermudes D., Mayer L. In vivo maintenance of synergistic cytarabine:daunorubicin ratios greatly enhances therapeutic efficacy. Leuk. Res. 2009;33:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shuhendler A.J., O'Brien P.J., Rauth A.M., Wu X.Y. On the synergistic effect of doxorubicin and mitomycin C against breast cancer cells. Drug Metabol. Drug Interact. 2007;22:201–233. doi: 10.1515/dmdi.2007.22.4.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ertas Y.N., Dorcheh K.A., Akbari A., Jabbari E. Nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery to cancer stem cells: a review of recent advances. Nanomaterials. 2021;11 doi: 10.3390/nano11071755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naguib Y.W., Cui Z. Nanomedicine: the promise and challenges in cancer chemotherapy. Nanomater. Impacts Cell Biol. Med. 2014:207–233. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-8739-0_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kulkarni-Dwivedi N., Patel P.R., Shravage B.V., Umrani R.D., Paknikar K.M., Jadhav S.H. Hyperthermia and doxorubicin release by Fol-LSMO nanoparticles induce apoptosis and autophagy in breast cancer cells. Nanomed. (Lond. Engl.) 2022;17:1929–1949. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2022-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mi Y., Zhang J., Tan W., Miao Q., Li Q., Guo Z. Preparation of doxorubicin-loaded carboxymethyl-β-cyclodextrin/chitosan nanoparticles with antioxidant, antitumor activities and pH-sensitive release. Mar. Drugs. 2022;20 doi: 10.3390/md20050278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feng X., Li F., Zhang L., Liu W., Wang X., Zhu R., Qiao Z.A., Yu B., Yu X. TRAIL-modified, doxorubicin-embedded periodic mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery and efficient antitumor immunotherapy. Acta Biomater. 2022;143:392–405. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shetake N.G., Ali M., Kumar A., Bellare J., Pandey B.N. Theranostic magnetic nanoparticles enhance DNA damage and mitigate doxorubicin-induced cardio-toxicity for effective multi-modal tumor therapy. Biomater. Adv. 2022;142 doi: 10.1016/j.bioadv.2022.213147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang S., Han F., Xie L., Liu Y., Yang Q., Zhao D., Zhao X. Preparation and evaluation of paclitaxel-loaded reactive oxygen species and glutathione redox-responsive poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles for controlled release in tumor cells. Nanomed. (Lond. Engl.) 2022;17:1627–1648. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2022-0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jan N., Madni A., Khan S., Shah H., Akram F., Khan A., Ertas D., Bostanudin M.F., Contag C.H., Ashammakhi N., et al. Biomimetic cell membrane-coated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2022 doi: 10.1002/btm2.10441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fu Y., Yang S., Liu Y., Liu J., Wang Q., Li F., Shang X., Teng Y., Guo N., Yu P. Peptide modified albumin-paclitaxel nanoparticles for improving chemotherapy and preventing metastasis. Macromol. Biosci. 2022;22 doi: 10.1002/mabi.202100404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yin H., Yan Q., Liu Y., Yang L., Liu Y., Luo Y., Chen T., Li N., Wu M. Co-encapsulation of paclitaxel and 5-fluorouracil in folic acid-modified, lipid-encapsulated hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles for synergistic breast cancer treatment. RSC Adv. 2022;12:32534–32551. doi: 10.1039/d2ra03718a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Konhäuser M., Kannaujiya V.K., Steiert E., Schwickert K., Schirmeister T., Wich P.R. Co-encapsulation of l-asparaginase and etoposide in dextran nanoparticles for synergistic effect in chronic myeloid leukemia cells. Int. J. Pharm. 2022;622 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2022.121796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao D., Hu X., Zhang J. Tumour targeted polymer nanoparticles co-loaded with docetaxel and siCCAT2 for combination therapy of lung cancer. J. Drug Target. 2022;30:534–543. doi: 10.1080/1061186x.2021.2016773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zou L., Zhang Z., Feng J., Ding W., Li Y., Liang D., Xie T., Li F., Li Y., Chen J., et al. Paclitaxel-loaded TPGS(2k)/gelatin-grafted cyclodextrin/hyaluronic acid-grafted cyclodextrin nanoparticles for oral bioavailability and targeting enhancement. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022;111:1776–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2022.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ren G., Li Y., Ping C., Duan D., Li N., Tang J., Wang R., Guo W., Niu X., Ji Q., et al. Docetaxel prodrug and hematoporphyrin co-assembled nanoparticles for anti-tumor combination of chemotherapy and photodynamic therapy. Drug Deliv. 2022;29:3358–3369. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2022.2147280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hashemi M., Ghadyani F., Hasani S., Olyaee Y., Raei B., Khodadadi M., Ziyarani M.F., Basti F.A., Tavakolpournegari A., Matinahmadi A., et al. Nanoliposomes for doxorubicin delivery: reversing drug resistance, stimuli-responsive carriers and clinical translation. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023;80 doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2022.104112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Silva M.M., Calado R., Marto J., Bettencourt A., Almeida A.J., Gonçalves L.M.D. Chitosan nanoparticles as a mucoadhesive drug delivery system for ocular administration. Mar. Drugs. 2017;15 doi: 10.3390/md15120370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singla A.K., Chawla M. Chitosan: some pharmaceutical and biological aspects–an update. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2001;53:1047–1067. doi: 10.1211/0022357011776441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baghdan E., Pinnapireddy S.R., Strehlow B., Engelhardt K.H., Schäfer J., Bakowsky U. Lipid coated chitosan-DNA nanoparticles for enhanced gene delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2018;535:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adhikari H.S., Yadav P.N. Anticancer activity of chitosan, chitosan derivatives, and their mechanism of action. Int. J. Biomater. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/2952085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ashrafizadeh M., Hushmandi K., Mirzaei S., Bokaie S., Bigham A., Makvandi P., Rabiee N., Thakur V.K., Kumar A.P., Sharifi E., Varma R.S. Chitosan-based nanoscale systems for doxorubicin delivery: exploring biomedical application in cancer therapy. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2023;8:e10325. doi: 10.1002/btm2.10325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park J.H., Lee S., Kim J.H., Park K., Kim K., Kwon I.C. Polymeric nanomedicine for cancer therapy. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2008;33:113–137. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fahmy S.A., Ramzy A., Mandour A.A., Nasr S., Abdelnaser A., Bakowsky U., Azzazy H.M.E. PEGylated chitosan nanoparticles encapsulating ascorbic acid and oxaliplatin exhibit dramatic apoptotic effects against breast cancer cells. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14020407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCarron P.A., Woolfson A.D., Keating S.M. Sustained release of 5-fluorouracil from polymeric nanoparticles. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2000;52:1451–1459. doi: 10.1211/0022357001777658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nair K.L., Jagadeeshan S., Nair S.A., Kumar G.S. Biological evaluation of 5-fluorouracil nanoparticles for cancer chemotherapy and its dependence on the carrier, PLGA. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011;6:1685–1697. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s20165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nair K.L., Jagadeeshan S., Nair S.A., Kumar G. Biological evaluation of 5-fluorouracil nanoparticles for cancer chemotherapy and its dependence on the carrier. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011;6:1685–1697. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S20165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aydin R.S.T., Pulat M. 5-Fluorouracil encapsulated chitosan nanoparticles for pH-stimulated drug delivery: evaluation of controlled release kinetics. J. Nanomater. 2012;2012:42. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li Y., Duan S., Jia H., Bai C., Zhang L., Wang Z. Flavonoids from tartary buckwheat induce G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human hepatoma HepG2 cells. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2014;46:460–470. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmu023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tummala S., Kuppusamy G., Satish Kumar M., Praveen T., Wadhwani A. 5-Fluorouracil enteric-coated nanoparticles for improved apoptotic activity and therapeutic index in treating colorectal cancer. Drug Deliv. 2016;23:2902–2910. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2015.1116026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.El-Hammadi M.M., Delgado Á.V., Melguizo C., Prados J.C., Arias J.L. Folic acid-decorated and PEGylated PLGA nanoparticles for improving the antitumour activity of 5-fluorouracil. Int. J. Pharm. 2017;516:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sağir T., Huysal M., Durmus Z., Kurt B.Z., Senel M., Isık S. Preparation and in vitro evaluation of 5-flourouracil loaded magnetite-zeolite nanocomposite (5-FU-MZNC) for cancer drug delivery applications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016;77:182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2015.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fadaeian G., Shojaosadati S.A., Kouchakzadeh H., Shokri F., Soleimani M. Targeted delivery of 5-fluorouracil with monoclonal antibody modified bovine serum albumin nanoparticles. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. IJPR. 2015;14:395–405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Handali S., Moghimipour E., Rezaei M., Saremy S., Dorkoosh F.A. Co-delivery of 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin in novel poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate acid)/poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles for colon cancer therapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;124:1299–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.09.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singh T., Kang D.H., Kim T.W., Kong H.J., Ryu J.S., Jeon S., Ahn T.S., Jeong D., Baek M.J., Im J. Intracellular delivery of oxaliplatin conjugate via cell penetrating peptide for the treatment of colorectal carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Pharm. 2021;606 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zumaya A.L.V., Rimpelová S., Štějdířová M., Ulbrich P., Vilčáková J., Hassouna F. Antibody conjugated PLGA nanocarriers and superparmagnetic nanoparticles for targeted delivery of oxaliplatin to cells from colorectal carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms23031200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schwarz C., Mehnert W., Lucks J., Müller R. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) for controlled drug delivery. I. Production, characterization and sterilization. J. Control. Release. 1994;30:83–96. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Taylor M., Daniels A., Andriano K., Heller J. Six bioabsorbable polymers: in vitro acute toxicity of accumulated degradation products. J. Appl. Biomater. 1994;5:151–157. doi: 10.1002/jab.770050208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rajpoot K., Jain S.K. Colorectal cancer-targeted delivery of oxaliplatin via folic acid-grafted solid lipid nanoparticles: preparation, optimization, and in vitro evaluation. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018;46:1236–1247. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2017.1366338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Janardhanam L.S.L., Bandi S.P., Venuganti V.V.K. Functionalized LbL film for localized delivery of STAT3 siRNA and oxaliplatin combination to treat colon cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022;14:10030–10046. doi: 10.1021/acsami.1c22166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang Q., Kuang G., Yu Y., Ding X., Ren H., Sun W., Zhao Y. Hierarchical microparticles delivering oxaliplatin and NLG919 nanoprodrugs for local chemo-immunotherapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022;14:48527–48539. doi: 10.1021/acsami.2c16564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gao J., Logan K.A., Nesbitt H., Callan B., McKaig T., Taylor M., Love M., McHale A.P., Griffith D.M., Callan J.F. A single microbubble formulation carrying 5-fluorouridine, Irinotecan and oxaliplatin to enable FOLFIRINOX treatment of pancreatic and colon cancer using ultrasound targeted microbubble destruction. J. Control. Release. 2021;338:358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Giacchetti S., Perpoint B., Zidani R., Le Bail N., Faggiuolo R., Focan C., Chollet P., Llory J.F., Letourneau Y., Coudert B., et al. Phase III multicenter randomized trial of oxaliplatin added to chronomodulated fluorouracil-leucovorin as first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000;18:136–147. doi: 10.1200/jco.2000.18.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.André T., Boni C., Mounedji-Boudiaf L., Navarro M., Tabernero J., Hickish T., Topham C., Zaninelli M., Clingan P., Bridgewater J., et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:2343–2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Thanki K., Gangwal R.P., Sangamwar A.T., Jain S. Oral delivery of anticancer drugs: challenges and opportunities. J. Control. Release. 2013;170:15–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jain A., Jain S.K., Ganesh N., Barve J., Beg A.M. Design and development of ligand-appended polysaccharidic nanoparticles for the delivery of oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2010;6:179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shakeel F., Haq N., Al-Dhfyan A., Alanazi F.K., Alsarra I.A. Double w/o/w nanoemulsion of 5-fluorouracil for self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system. J. Mol. Liq. 2014;200:183–190. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pangeni R., Choi S.W., Jeon O.C., Byun Y., Park J.W. Multiple nanoemulsion system for an oral combinational delivery of oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil: preparation and in vivo evaluation. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016;11:6379–6399. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s121114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.May J.P., Ernsting M.J., Undzys E., Li S.D. Thermosensitive liposomes for the delivery of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin to tumors. Mol. Pharm. 2013;10:4499–4508. doi: 10.1021/mp400321e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cheraga N., Ouahab A., Shen Y., Huang N.P. Characterization and pharmacokinetic evaluation of oxaliplatin long-circulating liposomes. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/5949804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alavi N., Rezaei M., Maghami P., Fanipakdel A., Avan A. Nanocarrier system for increasing the therapeutic efficacy of oxaliplatin. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2022;22:361–372. doi: 10.2174/1568009622666220120115140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]