Abstract

Background & Aims

Cirrhosis is associated with an increased surgical morbidity and mortality. Portal hypertension and the surgery type have been established as critical determinants of postoperative outcome. We aim to evaluate the hypothesis that preoperative transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement in patients with cirrhosis is associated with a lower incidence of in-house mortality/liver transplantation (LT) after surgery.

Methods

A retrospective database search for the years 2010–2020 was carried out. We identified 64 patients with cirrhosis who underwent surgery within 3 months after TIPS placement and 131 patients with cirrhosis who underwent surgery without it (controls). Operations were categorised into low-risk and high-risk procedures. The primary endpoint was in-house mortality/LT. We analysed the influence of high-risk surgery, preoperative TIPS placement, age, sex, baseline creatinine, presence of ascites, Chronic Liver Failure Consortium Acute Decompensation (CLIF-C AD), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores on in-house mortality/LT by multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression.

Results

In both the TIPS and the control cohort, most patients presented with a Child-Pugh B stage (37/64, 58% vs. 70/131, 53%) at the time of surgery, but the median MELD score was higher in the TIPS cohort (14 vs. 11 points). Low-risk and high-risk procedures amounted to 47% and 53% in both cohorts. The incidence of in-house mortality/LT was lower in the TIPS cohort (12/64, 19% vs. 52/131, 40%), also when further subdivided into low-risk (0/30, 0% vs. 10/61, 16%) and high-risk surgery (12/34, 35% vs. 42/70, 60%). Preoperative TIPS placement was associated with a lower rate for postoperative in-house mortality/LT (hazard ratio 0.44, 95% CI 0.19–1.00) on multivariable analysis.

Conclusions

A preoperative TIPS might be associated with reduced postoperative in-house mortality in selected patients with cirrhosis.

Impact and implications

Patients with cirrhosis are at risk for more complications and a higher mortality after surgical procedures. A transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is used to treat complications of cirrhosis, but it is unclear if it also helps to lower the risk of surgery. This study takes a look at complications and mortality of patients undergoing surgery with or without a TIPS, and we found that patients with a TIPS develop less complications and have an improved survival. Therefore, a preoperative TIPS should be considered in selected patients, especially if indicated by ascites.

Keywords: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, Portal hypertension, Cirrhosis, MELD score, CLIF score, VOCAL Penn score, Child-Pugh score

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Complications and in-house mortality are lower in TIPS patients undergoing surgery.

-

•

This effect is present after both low-risk and high-risk surgery.

-

•

A preoperative TIPS should be considered, especially if indicated by ascites.

-

•

Child-Pugh B and C patients undergoing surgery may benefit the most from a preoperative TIPS.

Introduction

Cirrhosis is associated with an increased surgical morbidity and mortality. The Child-Pugh score was developed for the purpose of surgical risk assessment and has stood the test of time.1,2 The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score has further improved preoperative risk stratification.3 Impaired organ function and portal hypertensive complications as integral components of these scores have widely been accepted to determine poor outcome. Importantly, portal hypertension itself as measured by the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) has only recently been identified as an independent predictor of postoperative mortality in patients undergoing hepatic4 and extrahepatic5 surgery. Additionally, high-risk (or major) and emergency surgery have emerged as critical determinants of an unfavourable postoperative outcome.3,[5], [6], [7], [8] These observations have led to the development of the Veterans Outcomes and Costs Associated with Liver Disease (VOCAL) Penn score,8 which provides an improved risk prediction for 30-day mortality in patients with cirrhosis undergoing surgery, considering both the status of liver disease and risks inherent to specific types of surgery.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement can correct portal hypertension and has emerged as the treatment of choice in patients with cirrhosis with recurrent and refractory ascites.9,10 The concept of prophylactic preoperative portal decompression by a TIPS to prevent morbidity and mortality of surgery was proposed by Haskal et al.11 already in 1994, shortly after its introduction into clinical practice.12 However, data on preoperative TIPS placements are still sparse, partly contradictory, and mainly consist of case reports,[13], [14], [15] case series[16], [17], [18], [19] (Table S1), and two summary articles.20,21 An undeniable reporting bias is inherent to these reports, and considering the lack of control groups, no real conclusion can be drawn regarding the clinical effect of a preoperative TIPS placement. So far, four retrospective studies have been published that also incorporated control groups, but with different study designs, endpoints, and conflicting results. The inclusion of patients in different stages of hepatic decompensation and various types of surgery may cloud the effect of a preoperative TIPS on postoperative outcome. Therefore, our present observational study incorporates a large control group of cirrhosis patients undergoing surgery without a TIPS and stratifies for low-risk and high-risk surgery. We aim to evaluate the hypothesis that preoperative TIPS placement in patients with cirrhosis is associated with a lower incidence of in-house mortality/liver transplantation (LT) after surgery.

Patients and methods

Patients

This retrospective single-centre study was approved by the local ethics committee (Ethikkommission Ärztekammer Hamburg, Germany, references PV5580 and PV3548) in accordance with the principles of both the declarations of Helsinki and Istanbul. The necessity to obtain written informed consent was waived because of the retrospective study design.

Patients with cirrhosis undergoing surgery with or without prior TIPS placement between 2010 and 2020 were identified by screening of our in-house TIPS registry and a clinical database search based on the encoding of the surgical catalogue and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th edition (ICD-10). For the TIPS cohort, we included both patients who had received a TIPS because of an upcoming surgery as the main indication for its placement, as well as patients who had received a TIPS to control ascites or variceal bleeding and later underwent surgery that was not anticipated at the time of TIPS placement. However, to reflect the main concept of a prophylactic TIPS placement, patients were excluded from the final analysis if: (i) surgery took place >90 days after TIPS placement, (ii) surgery was required as a result of TIPS procedure-related complications, (iii) only minor surgery was performed for which a preoperative TIPS placement would not have been discussed (e.g. catheter implantations), and (iv) TIPS placement was carried out between two consecutive surgical procedures.

For the control cohort, patients were excluded from the final analysis if: (i) surgery was related to hepatocellular carcinoma, (ii) surgery was performed in patients who had undergone previous LT, (iii) only minor surgery was carried out (catheter implantation), or (iv) data yield was insufficient.

For all patients, clinical, histological and radiological criteria were used to define cirrhosis. Patients who did not meet reliable criteria for cirrhosis were excluded.

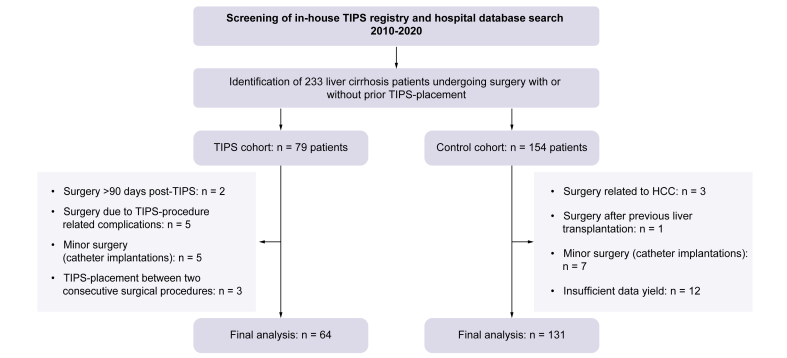

In total, 233 patients undergoing surgery with or without a TIPS were identified. In the TIPS cohort, 15 of 79 patients did not enter the final analysis according to exclusion criteria, resulting in a final cohort of 64 patients. In the control cohort, 23 of 154 patients were excluded, resulting in a final cohort of 131 patients (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patients included in the study.

Following database search, 64 patients undergoing surgery with a TIPS and 131 patients undergoing surgery without a TIPS were included in the final analysis. HCC; hepatocellular carcinoma; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

Data collection and endpoints

The electronic medical records of all patients were searched to obtain detailed preoperative baseline demographic and laboratory data, and a detailed history of the postoperative course. For the TIPS cohort, pre-TIPS laboratory values, pre-TIPS echocardiography results and invasive pressure measurements were also recorded. The preoperative risk stratification according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, the classification as emergency or elective surgery, and intraoperative procedural details were retrieved from the surgical and anaesthesiologic report. The presence of relevant ascites at the time of surgery was defined by ultrasound and clinical findings and by the need for paracentesis.

Operations were categorised into low-risk and high-risk procedures in accordance with the published literature,5,8 considering size of tissue trauma during surgery and level of urgency. In short, low-risk procedures encompassed elective orthopaedic operations, abdominal wall operations including incarcerated hernias without intestinal resection (hernia repair), minimally invasive laparoscopic and thoracoscopic operations and minor peripheral operations. High-risk procedures were defined as emergency orthopaedic operations and open thoracic and abdominal operations. When in doubt, the classification into low-risk or high-risk surgery was based on a consensus decision following discussion by multiple members of the study team (JV, JKG, FP, JK). The VOCAL Penn score was calculated for patients with (i) availability of complete datasets required for the score calculation who (ii) underwent operations for which the score was developed. Thus, minor peripheral operations, spine surgery, and oesophagectomies were excluded for not fitting into any of the six predefined categories of the score. Only the 30-day mortality prediction was analysed. The score calculation was available for 47 patients in the TIPS cohort and 100 patients in the control cohort.

The primary endpoint of this study was the incidence of in-house mortality and in-house LT. Secondary endpoints included: (i) intraoperative amount of blood and coagulation products transfused, (ii) postoperative amount of blood and coagulation products transfused, (iii) ongoing necessity and duration of catecholamine treatment and mechanical ventilation after surgery, (iv) occurrence of complications such as renal and liver failure, haemorrhage, infections, hepatic encephalopathy, the necessity for revision surgery, and (v) length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed for all variables. For continuous data, median values with the 0.25- and 0.75-quartile were calculated, for categorical data, percentages and counts are reported. A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model was applied to identify predictors of the primary endpoint, in-house mortality/LT. In patients who were discharged from hospital alive, the date of discharge, or last follow-up alive was integrated in the model. Covariates included in this analysis were selected according to the literature or if considered clinically relevant for the postoperative course. Thus, age, sex, baseline creatinine levels, presence of relevant ascites at the time of surgery, Chronic Liver Failure Consortium Acute Decompensation (CLIF-C AD) score, ASA score, MELD score, prior TIPS placement and the type of surgery (low risk vs. high risk) were included. For this model, the natural logarithm of baseline creatinine was used, as otherwise the linearity assumption did not hold. The proportional hazard assumption was checked graphically via Schoenfeld residuals and the linearity assumption for continuous predictors via martingale residuals. Missing values were not imputed and no adjustment for multiple testing was conducted. Secondary endpoints were compared descriptively. Figure design and statistical testing was carried out using SPSS Version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R Version 4.1.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Pre-TIPS work up

The main indication for TIPS placement in this cohort was prophylaxis of complications from anticipated surgery (26/64 patients, 41%, Tables S2 and S3), followed by refractory ascites (24/64 patients, 38%). In 6/64 patients (9%), the TIPS was implanted as an urgent pre-emptive treatment after variceal haemorrhage. Fourteen of 64 patients (22%) showed no or only mild signs of portal-hypertensive complications at TIPS implantation. Before TIPS placement, the median MELD score amounted to 13.0 (10.0, 17.0) points. Echocardiography excluded relevant cardiac impairment. The portosystemic pressure gradient (PSPG) was reduced from a median of 23.0 (20.0, 26.0) to 8.0 (7.0, 12.0) mmHg by TIPS. Table S3 provides details on patient characteristics, laboratory, and echocardiographic results, as well as invasive pressure measurements for the TIPS cohort.

Baseline characteristics and surgical details

Both patient cohorts were comparable regarding age and sex, with an overall predominance of middle-aged males (42/64 patients, 66% in the TIPS cohort vs. 80/131 patients, 61% in the control cohort, Table 1). The most common aetiology in both cohorts was alcohol-related liver disease. Cirrhosis-associated complications occurred more frequently in the medical history of TIPS patients, including episodes of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatic encephalopathy, and gastrointestinal bleeding. However, most patients in both cohorts were classified as Child-Pugh B at the time of surgery (37/64 patients, 58% in the TIPS cohort vs. 70/131 patients, 53% in the control cohort, Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Baseline characteristics | TIPS cohort (n = 64) | Control cohort (n = 131) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex: male/female (n, %) | 42 (66)/22 (34) | 80 (61)/51 (39) |

| Age (years) | 55.5 (48.0, 63.0) | 63.0 (54.0, 72.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.0 (22.6, 29.0) | 26.3 (22.7, 31.8) |

| Aetiology (n, %) | ||

| ALD | 38 (59) | 38 (29) |

| Viral | 11 (17) | 28 (21) |

| NASH | 3 (5) | 16 (12) |

| PBC/PSC/AIH | 8 (13) | 11 (8) |

| Cryptogenic and other | 4 (6) | 38 (29) |

| Child-Pugh score A/B/C/n.a. (n, %) | 14 (22)/37 (58)/12 (19)/1 (2) | 37 (28)/70 (53)/18 (14)/6 (5) |

| History of SBP (n, %) | 11 (17) | 12 (10) |

| History of HRS (n, %) | 19 (30) | 19 (15) |

| History of HE (n, %) | 26 (41) | 19 (15) |

| History of GI bleeding (n, %) | 29 (45) | 26 (20) |

| Variceal size 0/I/II/III/n.a. (n, %) | 9 (14)/15 (23)/17 (27)/7 (11)/16 (25) | 42 (32)/31 (24)/17 (13)/4 (3)/37 (28) |

| Red spots: yes/no/unknown (n, %) | 13 (20)/25 (39)/26 (41) | 13 (10)/55 (42)/63 (48) |

| NSBB treatment (n, %) | n.a. | 27 (21) |

Data are shown as counts and percentages as indicated or median values with the 0.25- and 0.75-quartile. Baseline characteristics were similar between the two cohorts.

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALD, alcohol-related liver disease; GI, gastrointestinal; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; HRS, hepatorenal syndrome; n.a., not available; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; NSBB, non-selective beta-blockers; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

Surgery was performed a median of 28 (11, 57) days after TIPS placement (Table 2). Relevant ascites at the time of surgery was present in 33/64 patients (52%) in the TIPS cohort and in 69/131 patients (53%) in the control cohort.

Table 2.

Baseline work up before surgery.

| Medical history | TIPS cohort (n = 64) | Control cohort (n = 131) |

|---|---|---|

| Median time interval TIPS placement–surgery (days) | 28 (11, 57) | - |

| Relevant ascites present at time of surgery: yes/no/n.a. (n, %) | 33 (52)/31 (49)/0 (0) | 69 (53)/60 (46)/2 (2) |

| Clinical signs of hepatic encephalopathy: yes/no/n.a. (n, %) |

12 (19)/51 (80)/1 (2) |

14 (11)/117 (89)/0 (0) |

| Laboratory values | ||

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 2.1 (1.1, 3,5) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.0) |

| AST (U/L) | 62.0 (37.0, 85.0) | 43.0 (31.0, 67.5) |

| ALT (U/L) | 32.0 (20.1, 58.3) | 26.0 (19.0, 42.0) |

| g-GT (U/L) | 91.0 (59.0, 212.0) | 116.0 (58.0, 219.0) |

| ALP (U/L) | 135.0 (101.5, 215.0) | 115.0 (81.0, 174.0) |

| Albumin (g/L) | 22.0 (19.0, 27.0) | 25.0 (20.0, 32.0) |

| Platelets (1,000/μl) | 106 (78, 160) | 143 (88, 222) |

| INR | 1.3 (1.2, 1.4) | 1.2 (1.1, 1.4) |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 2.9 (2.3, 3.9) | 3.2 (2.3, 3.7) |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.1 (3.8, 4.2) | 4.1 (3.8, 4.4) |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 139 (135, 140) | 138 (135, 141) |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.10 (0.72, 1.38) | 1.00 (0.8., 1.30) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 16.0 (5.0, 29.0) | 13.3 (4.0, 78.3) |

| White blood cell count (1,000/μl) | 7.7 (4.8, 10.6) | 7.2 (4.8, 12.4) |

| MELD score | 14.0 (11.0, 17.8) | 11.0 (8.0, 16.0) |

| Child-Pugh score (points) | 7.0 (7.0, 9.0) | 7.0 (6.0, 9.0) |

| Child-Pugh score A/B/C/n.a. (n, %) | 14 (22)/37 (58)/12 (19)/1 (2) | 37 (28)/70 (53)/18 (14)/6 (5) |

| CLIF-C AD score |

49.5 (45.0, 57.0) |

51.0 (45.5, 59.0) |

| Surgery details | ||

| ASA score II/III/IV/V/n.a. (n, %) | 2 (3)/39 (61)/19 (30)/2 (3)/2 (3) | 9 (7)/73 (56)/30 (23)/0 (0)/19 (15) |

| Elective/emergency surgery (n, %) | 41 (64)/23 (36) | 74 (56)/57 (44) |

| Low-risk procedures (n, %) | 30 (47) | 61 (47) |

| Elective orthopaedic surgery | 6 (20) | 4 (7) |

| Hernia repair | 9 (30) | 22 (36) |

| Laparoscopic interventions | 4 (13) | 28 (46) |

| Other | 11 (37) | 7 (11) |

| High-risk procedures (n, %) | 34 (53) | 70 (53) |

| Emergency orthopaedic surgery | 1 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Thoracotomy | 5 (15) | 6 (9) |

| Open abdominal surgery | 27 (79) | 61 (87) |

| Other | 1 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Surgery duration (min) | 120 (89, 246) | 113 (73, 195) |

Data are shown as counts and percentages as indicated or median values with the 0.25- and 0.75-quartile. Patients in the TIPS cohort presented with a relevantly higher MELD score. Low-risk and high-risk procedures were equally distributed between cohorts.

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CLIF-C AD, Chronic Liver Failure Consortium Acute Decompensation; g-GT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; INR, international normalised ratio; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; n.a., not available; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

The laboratory work up before surgery showed a higher MELD score in the TIPS cohort (14.0 [11.0, 17.8] vs. 11.0 [8.0, 16.0] points, respectively), whereas the CLIF-C AD score (49.5 [45.0, 57.0] vs. 51.0 [45.5, 59.0] points) and Child-Pugh score (7.0 [7.0, 9.0] vs. 7.0 [6.0, 9.0]) was similar between groups. Importantly, in the TIPS cohort, when comparing the laboratory work up before TIPS placement to the one before surgery, albumin levels decreased from 26.0 (20.4, 28.0) to 22.0 (19.0, 27.0) g/L, while bilirubin levels increased from 1.3 (0.9, 2.4) to 2.1 (1.1, 3.5) mg/dl, which also resulted in a higher MELD score (13.0 [10.0, 17.0] points pre-TIPS vs. 14.0 [11.0, 17.8] points before surgery; compare Table S3 and Table 2 for details).

In both cohorts, most patients were assessed with an ASA score of III or IV at the time of surgery. The distribution of low-risk and high-risk procedures amounted to 47% and 53%, respectively, in both groups (Table 2). However, although the most common low-risk surgery in the TIPS cohort was hernia repair (9/30 operations, 30%) followed by elective orthopaedic operations (6/30, 20%), the most common low-risk surgery in the control cohort were laparoscopic interventions (28/61, 46%) followed by hernia repair (22/61, 36%). In both cohorts, open abdominal surgery was the most frequent high-risk surgery (27/34, 79% in the TIPS cohort vs. 61/70, 87% in the control cohort).

Lower incidence of postoperative complications and in-house mortality/LT in the TIPS cohort

Consistent with the similar distribution of low-risk and high-risk procedures between the two cohorts, the median duration of surgery was also comparable (120 [89, 246] min in the TIPS cohort vs. 113 [73, 195] min in the control cohort, Table 2). Intraoperative patient management did not differ between groups regarding transfusion requirements (Table 3). However, there were relevant differences in the secondary endpoints evaluating the postoperative management: in the TIPS cohort, patients required blood and coagulation product substitution less frequently (29/64 patients, 45% vs. 75/131 patients, 57% and 10/64 patients, 16% vs. 56/131 patients, 43%, respectively) and in lower amounts (median of 3.0 [1.0, 9.5] vs. 6.0 [2.0, 17.3] units of blood and 3.5 [1.8, 11.5] vs. 8.0 [4.0, 29.0] units of coagulation products). Moreover, catecholamine treatment and postoperative intubation were required less frequently and for shorter periods (Table 3). Although postoperative renal replacement therapy was necessary in a similar percentage of patients in both cohorts, other complications that were assessed, such as hepatic encephalopathy (14/64, patients 22% vs. 43/131 patients, 33%), liver failure (11/64 patients, 17% vs. 46/131 patients, 35%), and sepsis (12/64 patients, 19% vs. 54/131 patients, 41%) occurred more frequently in the control cohort. Most strikingly, only 10/64 patients (16%) in the TIPS cohort suffered from bleeding complications, compared with 52/131 patients (40%) in the control cohort, with bleeding almost exclusively occurring within the surgical area in both cohorts (90% vs. 85%, respectively). Therefore, revision surgery was also performed less frequently in the TIPS cohort (17/64 patients, 27% vs. 63/131 patients, 48%).

Table 3.

Complication management and postoperative outcome parameters.

| Parameters | TIPS cohort (n = 64) | Control cohort (n = 131) |

|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative patient management | ||

| Any substitution of blood products (n, %) | 21 (33) | 37 (28) |

| Median no. of blood products transfused | 5.0 (2.0, 14.0) | 3.0 (2.0, 6.0) |

| Any substitution of coagulation products (n, %) | 19 (30) | 39 (30) |

| Median no. of coagulation products transfused |

3.0 (2.0, 6.0) |

5.0 (3.0, 10.0) |

| Postoperative patient management | ||

| Any substitution of blood products (n, %) | 29 (45) | 75 (57) |

| Median no. of blood products transfused | 3.0 (1.0, 9.5) | 6.0 (2.0, 17.3) |

| Any substitution of coagulation products (n, %) | 10 (16) | 56 (43) |

| Median no. of coagulation products transfused | 3.5 (1.8, 11.5) | 8.0 (4.0, 29.0) |

| Any catecholamine treatment (n, %) | 27 (42) | 74 (57) |

| Duration of catecholamine treatment (h) | 55.0 (22.0, 112.0) | 160.5 (38.8, 433.5) |

| Ongoing postoperative intubation (n, %) | 18 (28) | 55 (42) |

| Intubation time (h) | 48.5 (10.8, 101.3) | 96.0 (21.0, 401.0) |

| Renal failure (renal replacement therapy, n, %) | 10 (16) | 26 (20) |

| Any hepatic encephalopathy (n, %) | 14 (22) | 43 (33) |

| Grade of hepatic encephalopathy I/II/III/n.a. (n, %) | 5 (36)/8 (57)/1 (7)/0 (0) | 6 (14)/22 (51)/3 (7)/12 (28) |

| Liver failure (n, %) | 11 (17) | 46 (35) |

| Infectious complications (n, %) | 25 (39) | 71 (54) |

| Sepsis (n, %) | 12 (19) | 54 (41) |

| Bleeding complications (n, %) | 10 (16) | 52 (40) |

| Variceal bleeding | 1 (10) | 2 (4) |

| Gastric ulcer | – | 4 (8) |

| Bleeding within surgical area | 9 (90) | 44 (85) |

| Unspecified | – | 2 (4) |

| Revision surgery (n, %) |

17 (27) |

63 (48) |

| Outcome parameters | ||

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 1.5 (0.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (1.0, 15.0) |

| In-house mortality/LT (n, %) | 12 (19) – one LT | 52 (40) – two LTs |

| After low-risk procedures (n/N, %) | 0/30 (0) | 10/61 (16) – one LT |

| After high-risk procedures (n/N, %) | 12/34 (35) – one LT | 42/70 (60) – one LT |

| Time to death/LT (days) | 10.5 (4.0, 16.3) | 17.5 (8.8, 30.0) |

Data are shown as counts and percentages as indicated or median values with the 0.25- and 0.75-quartile. Intraoperative patient management did not differ between cohorts. However, during the postoperative course, patients with a preoperative TIPS received less blood and coagulation products, less catecholamine treatment and developed less complications. Consequently, in-house mortality/LT was also lower in the TIPS cohort.

ICU, intensive care unit; LT, liver transplantation; n.a., not available; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

In line with these findings, patients in the TIPS cohort had a shorter ICU stay (1.5 [0.0, 5.0] vs. 4.0 [1.0, 15.0] days). Most importantly, however, the combined primary endpoint of in-house mortality/LT was also met in a markedly lower proportion of patients in the TIPS cohort (12/64 patients, 19% vs. 52/131 patients, 40%).

The risk for in-house mortality/LT increases for high-risk surgery but decreases after prior TIPS placement

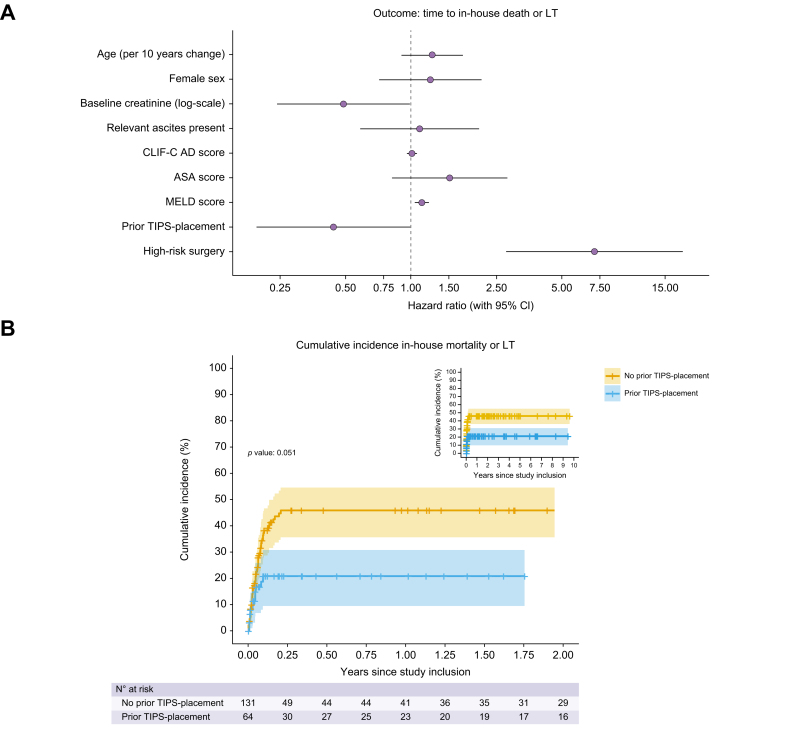

We analysed the influence of age, sex, baseline creatinine levels, presence of relevant ascites at the time of surgery, CLIF-C AD score, ASA score, MELD score, prior TIPS placement and the type of surgery (low-risk vs. high-risk) on the incidence of in-house mortality/LT by a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model (Fig. 2 and Table S4). The increased rate for in-house mortality/LT by 52% per unit change in the ASA score can be considered clinically relevant, even though not statistically significant (p = 0.183). Additionally, MELD score and high-risk surgery were associated with a higher risk for in-house mortality/LT (hazard ratio [HR] 1.13, 95% CI 1.05–1.21, p = 0.001 and HR 7.06, 95% CI 2.75–18.13, p <0.001, respectively), whereas a preoperative TIPS placement was associated with a lower risk (HR 0.44, 95% CI 0.19–1.00, p = 0.051) in our cohort (Fig. 2, Table S4, Fig. S1). The association of the analysed variables also remained similar when only in-house mortality was taken into account (MELD score: HR 1.12, 95% CI 1.04–1.21, p = 0.002; high-risk surgery: HR 6.95, 95% CI 2.70–17.89, p <0.001; prior TIPS placement: HR 0.46, 95% CI 0.20–1.04, p = 0.062, see Table S5 and Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards model to identify predictors of in-house mortality/LT.

(A) The risk for in-house mortality increases with high-risk surgery and the preoperative MELD score but is lowered by preoperative TIPS placement. (B) shows the Kaplan-Meier estimate for the incidence of in-house mortality/LT. ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CLIF-C AD, chronic liver failure consortium acute decompensation; LT, liver transplantation; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

Subpopulation analysis: no in-house mortality after low-risk surgery in the TIPS cohort

Following the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model, we further stratified the TIPS and the control cohort according to low- and high-risk surgery. Table 4 displays the exact types of surgery performed. After low-risk surgery, 0/30 patients (0%) in the TIPS cohort deceased, whereas 10/61 patients (16%) had died or undergone LT (one patient) in the control cohort, with relevant differences in elective orthopaedic operations and hernia repairs. Furthermore, in the high-risk surgery group, the incidence of in-house mortality/LT was also lower in the TIPS cohort (12/34 patients, 35% vs. 42/70 patients, 60%, with one LT in each cohort). This also applied to all subtypes of high-risk surgery, that is, emergency orthopaedic, open thoracic, and open abdominal surgery. In this last subgroup, the difference was primarily seen in patients undergoing bowel resection (Table 4). These observations remained valid when we analysed only patients who underwent elective operations, even though patients in the TIPS cohort also presented with more advanced stages of liver disease in this subpopulation analysis (median MELD score 13.0 [10.0, 15.0] vs. 9.0 [8.0, 13.0] points; Child-Pugh A patients: 12/41, 29% vs. 30/74, 41% in the TIPS vs. control cohort, respectively). Specifically, 0/22 patients (0%) after elective low-risk procedures and preoperative TIPS placement experienced in-house mortality/LT compared with 5/40 patients (13%) in the control group without prior TIPS. After elective high-risk procedures, 6/19 (32%) vs. 15/34 (44%) patients met the combined endpoint of postoperative in-house mortality/LT in the TIPS and the control cohort, respectively (Table S6).

Table 4.

Detailed overview on surgical procedures and in-house mortality/LT.

| n in-house death or LT/n operations | n in-house death or LT/n operations | |

|---|---|---|

| Low-risk surgery | TIPS cohort (n = 30) | Control cohort (n = 61) |

| Elective orthopaedic surgery | 0/6 (0% dead) | 2/4 (50% dead/LT) |

| Spondylodiscitis | 0/1 (0% dead) | – |

| Kyphoplasty | 0/2 (0% dead) | 0/2 (0% dead) |

| Nail osteosynthesis (femoral/humoral) | 0/2 (0% dead) | 1/1 (100% LT) |

| Hip endoprosthesis | 0/1 (0% dead) | 1/1 (100% dead) |

| Hernia repair | 0/9 (0% dead) | 2/22 (9% dead) |

| Laparoscopic interventions | 0/4 (0% dead) | 5/28 (18% dead) |

| Cholecystectomy | 0/2 (0% dead) | 0/10 (0% dead) |

| Abdominal haematoma evacuation | 0/1 (0% dead) | 1/3 (33% dead) |

| Sleeve gastrectomy | 0/1 (0% dead) | 1/9 (11% dead) |

| Sigmoidostomy | – | 0/1 (0% dead) |

| Explorations | – | 2/2 (100% dead) |

| Lung resection/pleurectomy | – | 1/3 (33% dead) |

| Other | 0/11 (0% dead) | 1/7 (14% dead) |

| Abscess cleavage and necrotic wound debridement | 0/2 (0% dead) | 1/4 (25% dead) |

| Oesophageal endoscopic mucosa dissection | 0/2 (0% dead) | – |

| Bladder tamponade clearance | 0/1 (0% dead) | – |

| Mandibular vestibuloplasty | 0/2 (0% dead) | – |

| Tracheotomy | 0/2 (0% dead) | – |

| Circumcision | 0/1 (0% dead) | – |

| Lymph node extirpation | 0/1 (0% dead) | 0/1 (0% dead) |

| Thyroidectomy |

– |

0/2 (0% dead) |

| High-risk surgery | TIPS cohort (n = 34) | Control cohort (n = 70) |

| Emergency orthopaedic surgery | 0/1 (0% dead) | 2/2 (100% dead) |

| Dislocated humerus fracture | 0/1 (0% dead) | – |

| Destructive spondylodiscitis | – | 2/2 (100% dead) |

| Thoracotomy | 0/5 (0% dead) | 3/6 (50% dead/LT) |

| Decortication and pleurectomy | 0/3 (0% dead) | 2/3 (66% dead/LT) |

| Lung resection | 0/2 (0% dead) | 1/3 (33% dead) |

| Open abdominal surgery | 12/27 (44% dead/LT) | 36/61 (59% dead) |

| Shunt surgery with splenectomy | 0/1 (0% dead) | 0/2 (0% dead) |

| Pancreatectomy (including Whipple procedure) | 1/4 (25% LT) | 1/3 (33% dead) |

| Bowel resection (ileo- and/or colectomy) | 4/11 (36% dead) | 24/36 (67% dead) |

| Kidney transplantation | 0/1 (0% dead) | – |

| Gastrectomy | 2/4 (50% dead) | 3/8 (38% dead) |

| Cholecystectomy | 1/2 (50% dead) | 1/2 (50% dead) |

| Oesophagectomy | 3/3 (100% dead) | 6/9 (67% dead) |

| Abdominal compartment as a result of bleeding | 1/1 (100% dead) | – |

| Intra-abdominal abscess cleavage | – | 1/1 (100% dead) |

| Other | 0/1 (0% dead) | 1/1 (100% dead) |

| Subcutaneous abscess with resection of thesternum | 0/1 (0% dead) | – |

| Emergency foot amputation (gangrene) | – | 1/1 (100% dead) |

The incidence of in-house mortality/LT is lower in the TIPS cohort after both low-risk and high-risk surgery. Numbers in bold indicate the incidence of in-house mortality/LT of the respective subcategory.

LT, liver transplantation; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

Prediction of postoperative mortality by calculation of the VOCAL Penn score: improved survival in the TIPS cohort across different risk strata

We calculated the VOCAL Penn score for all eligible patients in the TIPS and the control cohort and stratified patient outcome according to different strata of the 30-day mortality risk prediction model, specifically 0–1%, 1–5%, 5–10%, 10–20%, 20–50%, and >50% (Table 5). Patients in the TIPS cohort had higher predicted mortality risks according to the VOCAL Penn score compared with patients in the control cohort, resulting in a predicted median 30-day mortality of 10.0% (4.5%, 21.1%) vs. 4.9% (1.6%, 15.9%), respectively. These findings are in line with the higher preoperative MELD score in the TIPS cohort. However, the incidence of in-house mortality/LT was lower in patients with a preoperative TIPS across all strata of the risk prediction model.

Table 5.

Risk stratification according to the predicted 30-day mortality as calculated by the VOCAL Penn score.

| Predicted 30-day mortality VOCAL Penn score | TIPS cohort (n = 47) |

Control cohort (n = 100) |

|---|---|---|

| n in-house death or LT/n operations | n in-house death or LT/n operations | |

| <1% | 0/3 (0% dead) | 1/17 (6% dead) |

| Abdominal – laparoscopic | 0/2 (0% dead) | 1/16 (6% dead) |

| Abdominal – open | – | 0/1 (0% dead) |

| Abdominal wall | 0/1 (0% dead) | – |

| Major orthopaedic | – | – |

| Chest/cardiac | – | – |

| 1–5% | 0/10 (0% dead) | 6/33 (18% dead) |

| Abdominal – laparoscopic | 0/2 (0% dead) | 2/10 (20% dead) |

| Abdominal – open | 0/4 (0% dead) | 3/9 (33% dead) |

| Abdominal wall | 0/4 (0% dead) | 0/12 (0% dead) |

| Major orthopaedic | – | – |

| Chest/cardiac | – | 1/2 (50% dead) |

| 5–10% | 1/11 (9% LT) | 5/13 (38% dead) |

| Abdominal – laparoscopic | 0/2 (0% dead) | 0/1 (0% dead) |

| Abdominal – open | 1/4 (25% LT) | 5/8 (63% dead) |

| Abdominal wall | 0/2 (0% dead) | 0/4 (0% dead) |

| Major orthopaedic | 0/1 (0% dead) | – |

| Chest/cardiac | 0/2 (0% dead) | – |

| 10–20% | 3/10 (30% dead) | 12/19 (63% dead) |

| Abdominal – laparoscopic | – | 1/1 (100% dead) |

| Abdominal – open | 3/5 (60% dead) | 10/13 (77% dead) |

| Abdominal wall | 0/2 (0% dead) | 0/1 (0% dead) |

| Major orthopaedic | 0/2 (0% dead) | – |

| Chest/cardiac | 0/1 (0% dead) | 1/4 (25% dead) |

| 20–50% | 1/6 (17% dead) | 9/12 (75% dead) |

| Abdominal – laparoscopic | – | – |

| Abdominal – open | 1/4 (25% dead) | 7/10 (70%) |

| Abdominal wall | – | – |

| Major orthopaedic | 0/2 (0% dead) | 1/1 (100% dead) |

| Chest/cardiac | – | 1/1 (100% dead) |

| >50% | 4/7 (57% dead) | 6/6 (100% dead/LT) |

| Abdominal – laparoscopic | – | – |

| Abdominal – open | 4/5 (80% dead) | 4/4 (100% dead) |

| Abdominal wall | – | – |

| Major orthopaedic | – | 1/1 (100% LT) |

| Chest/cardiac | 0/2 (0% dead) | 1/1 (100% LT) |

The incidence of in-house mortality/LT is lower in the TIPS cohort across all strata of the predicted 30-day mortality as calculated by the VOCAL Penn score.

LT, liver transplantation; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; VOCAL, Veterans Outcomes and Costs Associated with Liver Disease.

Postoperative outcome according to the stage of liver disease

It is conceivable that patients with decompensated cirrhosis benefit more from a prophylactic preoperative TIPS placement than patients with compensated cirrhosis. To address this question, we compared patients who had received a prophylactic TIPS with no or only minor manifestations of portal hypertension (i.e. perihepatic ascites and varices without a history of bleeding) with similar patients in the control cohort (Table S7). In this small subpopulation analysis of n = 12 patients each, we did not observe a survival benefit in the TIPS cohort with a similar incidence of in-house mortality/LT (4/12 patients, 33% and 5/12 patients, 42%) in the TIPS and control cohort, respectively. However, the length of ICU stay was shorter in the TIPS cohort (3.5 vs. 8.5 days), suggesting a reduction of postoperative morbidity.

With no clear survival benefit in patients without signs of portal-hypertensive complications, we finally stratified both cohorts according to the Child-Pugh stage (Table 6). Although the incidence of in-house mortality/LT was not different in the TIPS and the control cohort in patients with Child-Pugh A cirrhosis, patients who presented with Child-Pugh stage B and C and with preoperative TIPS placement had an improved transplant-free survival compared with control patients without TIPS. For patients with Child-Pugh B cirrhosis, the incidence of in-house mortality/LT was 4/37 patients (11%) in the TIPS cohort, compared with 32/70 patients (46%) in the control cohort. In patients with Child-Pugh C cirrhosis, postoperative in-house mortality/LT occurred in 4/12 cases (33%) in the TIPS vs. 14/18 cases (78%) in the control cohort.

Table 6.

In-house mortality/LT stratified according to the Child-Pugh stage.

| TIPS cohort (n = 63) | Control cohort (n = 125) | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||

| Child-Pugh A (n, %) | 14 (22) | 37 (29) |

| Sex: male/female (n, %) | 8 (57)/6 (43) | 22 (59)/15 (41) |

| Age (years) | 58.0 (54.3, 62.5) | 66.0 (52.0, 71.0) |

| Child-Pugh B (n, %) | 37 (59) | 70 (56) |

| Sex: male/female (n, %) | 26 (70)/11 (30) | 43 (61)/27 (39) |

| Age (years) | 54.0 (47.0, 65.0) | 64.5 (55.0, 72.0) |

| Child-Pugh C (n, %) | 12 (19) | 18 (14) |

| Sex: male/female (n, %) | 8 (66)/4 (33) | 13 (72)/5 (28) |

| Age (years) |

55.5 (46.8, 59.0) |

61.5 (53.0, 66.8) |

| Laboratory values | ||

| Child-Pugh A | ||

| MELD score | 12.0 (10.0, 13.8) | 9.0 (8.0, 10.5) |

| CLIF-C AD score | 47.5 (43.3, 50.8) | 46.0 (41.0, 51.3) |

| Child-Pugh B | ||

| MELD score | 14.0 (11.0, 15.0) | 10.5 (8.0, 14.0) |

| CLIF-C AD score | 48.0 (45.0, 54.0) | 52.0 (46.0, 58.0) |

| Child-Pugh C | ||

| MELD score | 19.5 (18.0, 22.3) | 23.5 (19.3, 29.5) |

| CLIF-C AD score |

58.5 (57.0, 61.0) |

60.5 (54.3, 72.0) |

| Surgery details | ||

| Child-Pugh A | ||

| ASA score II/III/IV/V/n.a. (n, %) | 0 (0)/11 (79)/3 (21)/0 (0)/0 (0) | 3 (8)/26 (70)/2 (5)/0 (0)/6 (16) |

| Low-risk procedures (n/N, %) | 5/14 (36) | 24/37 (65) |

| High-risk procedures (n/N, %) | 9/14 (64) | 13/37 (35) |

| Child-Pugh B | ||

| ASA score II/III/IV/V/n.a. (n, %) | 2 (5)/25 (68)/9 (24)/1 (3)/0 (0) | 4 (6)/42 (60)/14 (20)/0 (0)/10 (14) |

| Low-risk procedures (n/N, %) | 21/37 (57) | 29/70 (41) |

| High-risk procedures (n/N, %) | 16/37 (43) | 41/70 (59) |

| Child-Pugh C | ||

| ASA score II/III/IV/V/n.a. (n, %) | 0 (0)/3 (25)/6 (50)/1 (8)/2 (17) | 2 (11)/4 (22)/12 (67)/0 (0)/0 (0) |

| Low-risk procedures (n/N, %) | 4/12 (33) | 5/18 (28) |

| High-risk procedures (n/N, %) |

8/12 (67) |

13/18 (72) |

| Outcome parameters | ||

| Child-Pugh A | ||

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 1.5 (0.0, 5.8) | 1.0 (0.0, 1.0) |

| In-house mortality/LT (n/N, %) | 3/14 (21) – one LT | 4/37 (11) |

| After low-risk procedures (n/N, %) | 0/5 (0) | 0/24 (0) |

| After high-risk procedures (n/N, %) | 3/9 (33) – one LT | 4/13 (31) |

| Child-Pugh B | ||

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 1.0 (0.0, 4.0) | 6.0 (1.0, 19.0) |

| In-house mortality/LT (n/N, %) | 4/37 (11) | 32/70 (46) |

| After low-risk procedures (n/N, %) | 0/21 (0) | 7/29 (24) |

| After high-risk procedures (n/N, %) | 4/16 (25) | 25/41 (61) |

| Child-Pugh C | ||

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 3.0 (1.8, 4.0) | 7.5 (1.8, 15.0) |

| In-house mortality/LT (n/N, %) | 4/12 (33) | 14/18 (78) – two LTs |

| After low-risk procedures (n/N, %) | 0/4 (0) | 2/5 (40) – one LT |

| After high-risk procedures (n/N, %) | 4/8 (50) | 12/13 (92) – one LT |

Data are shown as counts and percentages as indicated or median values with the 0.25- and 0.75-quartile. In patients classified as Child-Pugh A, the incidence of in-house mortality/LT was not different between the two cohorts, neither after low-risk nor after high-risk operations. However, the incidence of in-house mortality/LT was relevantly lower in patients who were Child-Pugh B and C after prior TIPS placement.

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CLIF-C AD, chronic liver failure consortium acute decompensation; ICU, intensive care unit; LT, liver transplantation; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; n.a., not available; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

Discussion

Portal hypertension and high-risk surgery have recently been shown to be critical determinants of postoperative mortality in patients with cirrhosis undergoing surgery.5,7 In our retrospective analysis, the presence of a TIPS before surgery was associated with a lower incidence of postoperative in-house mortality/LT in patients with Child-Pugh B and C cirrhosis.

In the context of the published literature,[22], [23], [24], [25] our study stands out in several of its aspects and significantly contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting the potential benefit of preoperative TIPS placement. First, we present the largest number of patients in both the TIPS and the control cohorts. Second, in-house mortality is the most appropriate endpoint in this setting, as long-term endpoints such as 1-year mortality,25 although relevant, may rather reflect the course of liver disease than surgery-related morbidity and mortality. A beneficial effect of TIPS on long-term survival in decompensated cirrhosis has already been established in several randomised controlled trials.[26], [27], [28], [29] Moreover, we also assessed secondary endpoints that are relevant for postoperative morbidity such as transfusion requirements, bleeding complications, and the length of the ICU stay in detail. Third, we only included patients who underwent surgery within 3 months after TIPS placement. This is particularly relevant for evaluating the concept of a preoperative TIPS, as liver synthesis deteriorates in the first weeks after TIPS placement, which was also observed in our cohort, and may adversely affect surgical outcome. A longer time interval25 between TIPS and surgery does not appropriately reflect a practical period between indication and actual performance of surgery.

Another strength of our study is the careful multivariable analysis that controls for known and proposed risk factors such as age, ASA, and MELD score,3 CLIF C AD score,25 and most importantly, a risk classification of surgical procedures. Our multivariable analysis supports the hypothesis that patients with higher MELD scores and patients undergoing high-risk surgery are at a higher risk for in-house mortality, which is consistent with the published literature. However, the analysis also suggests that a prior TIPS placement may decrease the risk for postoperative in-house mortality with a HR of 0.44, even though the level of significance is missed (p = 0.051) in this model with the variables chosen. However, in the light of our other results we still consider our findings relevant: We observed that 0/30 patients (0%) died or underwent LT if undergoing low-risk surgery after prior TIPS placement, compared with 10/61 patients (16%) that were operated without a TIPS. Importantly, the incidence of in-house mortality/LT was also lower after high-risk surgery (12/34, 35% vs. 42/70, 60% in the TIPS and control cohort, respectively. The beneficial outcome in the TIPS cohort after both low-risk and high-risk surgery is even more relevant when the baseline characteristics are considered, as patients in the TIPS cohort had a higher MELD score at the time of surgery (14 vs. 11 points), with the MELD score itself being a significant predictor of an adverse postoperative outcome. In line with this, we also show that patients undergoing surgery after prior TIPS placement have an improved survival across different risk strata of the 30-day mortality risk prediction according to the VOCAL Penn score.

The conflicting results regarding the effect of a preoperative TIPS placement in the published literature may be explained by differences in study design and the composition of the respective patient cohorts. Vinet et al.22 compared 1-month mortality and complications after elective major abdominal surgery in a small cohort study but found no difference between the groups for the respective outcome parameters. However, the control group had a relevantly lower Child-Pugh score indicating lower severity of liver disease as a possible explanation. Similarly, Tabchouri et al.23 found no survival benefit in their propensity-matched retrospective study of 68 control patients and 56 patients who had received a prophylactic TIPS before undergoing elective abdominal surgery. However, the study comprised >60% Child-Pugh A patients and the authors did not distinguish between low-risk and high-risk surgery. A possible survival benefit may have also been overlooked due to the low 30-day mortality rate of 1.8% and 3% in the TIPS and control cohort, respectively.

The two most recent studies found a stronger benefit for patients with preoperative TIPS. Aryan et al.24 present a small unmatched study in patients that had received a TIPS for non-surgical reasons and underwent low-risk surgery (>80% hernia repairs) a median of 28 days post-TIPS. The 30-day mortality was 0% in both cohorts, and therefore not different, but in the TIPS cohort patients developed ascites and acute kidney injury less frequently. The most recent study by Chang et al.25 reported the retrospective evaluation of matched cohorts of 45 patients each undergoing surgery with or without a TIPS regarding development of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) and 1-year survival. The median interval between TIPS placement and surgery was 6 months, which led to low presence of ascites in the TIPS cohort (4%). Most patients underwent surgical procedures that would have been classified as low-risk, with hernia repairs being the most common intervention. In this study, patients who underwent visceral surgery with a TIPS were less likely to develop ACLF at 28 and 90 days, received fewer blood transfusions, had less ascites development and a shorter ICU stay than the control cohort, and finally, an improved 1-year survival.

Our study has the limitations inherent to a retrospective analysis. First, some patients who experienced TIPS procedure-related complications may not have lived to undergo the anticipated surgery. Others may have experienced deterioration of liver function following TIPS placement and were too sick to undergo surgery, therefore not entering the analysis. Thus, cumulated risks of two consecutive procedures (TIPS placement followed by surgery) cannot be assessed by our study. Because of the retrospective design of our study, a systematic assessment of post-TIPS morbidity in patients with intended surgery was not available. However, a recent study in 28 patients undergoing preoperative TIPS placement has shown that two of 28 patients (7%) were not able to undergo the scheduled surgery.30 Second, not all TIPS analysed in our study were implanted to prevent morbidity and mortality of a future surgery. In almost half of the cases, indications for TIPS implantation and for surgery were made independently from each other. Even if our study comprises the largest cohort so far, the sample size is limited and may be too small to detect all relevant predictors and results in wide confidence intervals and thus an imprecise estimation. Additionally, the results of our multivariable analysis are limited to the included variables and this dataset only. Thus, the inclusion of other variables which would also have a merit such as the Child-Pugh score may change the results. In addition, a categorisation of low-risk and high-risk surgery is not standardised; although we classified elective major orthopaedic and thoracoscopic interventions as low-risk operations, these interventions are associated with a high surgical risk in the VOCAL Penn score. Therefore, our data can only provide a preliminary statement to the question if a TIPS should be implanted preoperatively to decrease postoperative morbidity and mortality, even though this study by its design reflects this concept.

Despite these limitations, our findings support the hypothesis that a preoperative TIPS may reduce postoperative mortality in selected patients with cirrhosis and represent a rational for a randomised controlled trial to evaluate preoperative TIPS as a prognosis-modifying concept. Importantly, our data illustrate that postoperative outcome in patients with cirrhosis is heterogeneously distributed depending on the type of surgery.7,8 Thus, the design of a randomised prospective intervention study must include a stratification of the type of extrahepatic surgery to obtain robust findings on the effects of a preoperative TIPS. Short-term mortality should be the primary endpoint for patients undergoing low-risk and high-risk surgery. Whether LT classifies as an adverse outcome especially in patients already on the waiting list remains debatable, so that ‘unexpected’ LT as an additional endpoint may be more adequate.

The fact that our study, but not the one by Tabchouri et al.,23 demonstrates an association of prior TIPS placement with a reduced postoperative mortality is likely explained by differences in baseline characteristics, as the Tabchouri cohort consisted of 65% patients who were Child-Pugh A, whereas patients who were Child-Pugh A comprised only 25% of our cohort. Importantly, our findings suggest that only patients classified as Child-Pugh B or C, but not Child-Pugh A obtain a survival benefit from a preoperative TIPS placement. This represents a comprehensible explanation for previous negative studies.

Taking this into consideration, a future prospective trial should also stratify for the preoperative stage of decompensation of cirrhosis. Although the study by Reverter et al.5 suggests that an elevated HVPG >16 mmHg represents an independent risk factor for an unfavourable postoperative outcome and thus a treatment target, it is unclear if a preoperative TIPS implantation is justified just by elevated HVPG measurements in patients without clinical decompensation and in patients classified as Child-Pugh A. It is possible that the risk–benefit balance only favours preoperative TIPS placement in patients with decompensation of cirrhosis.

Our data and the study by Chang et al.25 suggest that patients who have received a TIPS in the past and are consequently recompensated are relatively safe to undergo especially low-risk surgery. Therefore, in light of the data presented in this study and with confirmatory results of prospective randomised trials pending, a pragmatic approach for patients with cirrhosis who need to undergo surgery is to perform prior TIPS placement if indicated by ascitic decompensation according to established criteria.31

In conclusion, in our study a preoperative TIPS is associated with a reduced incidence of postoperative in-house mortality/LT in selected patients with cirrhosis. These promising results should be confirmed in a prospective randomised controlled clinical trial that also addresses the question at which stage of liver disease severity according to HVPG and Child-Pugh score a preoperative TIPS is beneficial.

Financial support

This study was supported by the Dr Brauns foundation (Dr Liselotte-Brauns research prize 2018 to JK and FP).

Authors’ contributions

Conception of the study: FP, JK. Design of the study: FP, JKG, JK. Data acquisition: FP, JV, FF. Statistical analysis: FP, AKO. Interpretation of the data: FP, JV, AH, DB, PH, MR, CR, PB, JRI, GA, SH, AWL. Writing the manuscript: FP, JV, JK. Critical reading: FF, JKG, AKO, AH, DB, PH, MR, CR, PB, JRI, GA, SH, AWL, JK. Final approval: JK.

Data availability statement

Data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare regarding the work under consideration for publication.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2023.100914.

Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

:

References

- 1.Child C.G., Turcotte J.G. Surgery and portal hypertension. Major Probl Clin Surg. 1964;1:1–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pugh R.N., Murray-Lyon I.M., Dawson J.L., et al. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646–649. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teh S.H., Nagorney D.M., Stevens S.R., et al. Risk factors for mortality after surgery in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1261–1269. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boleslawski E., Petrovai G., Truant S., et al. Hepatic venous pressure gradient in the assessment of portal hypertension before liver resection in patients with cirrhosis. Br J Surg. 2012;99:855–863. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reverter E., Cirera I., Albillos A., et al. The prognostic role of hepatic venous pressure gradient in cirrhotic patients undergoing elective extrahepatic surgery. J Hepatol. 2019;71:942–950. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhangui P., Laurent A., Amathieu R., et al. Assessment of risk for non-hepatic surgery in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 2012;57:874–884. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahmud N., Fricker Z., Serper M., et al. In-hospital mortality varies by procedure type among cirrhosis surgery admissions. Liver Int. 2019;39:1394–1399. doi: 10.1111/liv.14156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahmud N., Fricker Z., Hubbard R.A., et al. Risk prediction models for post-operative mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2021;73:204–218. doi: 10.1002/hep.31558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piecha F., Radunski U.K., Ozga A.K., et al. Ascites control by TIPS is more successful in patients with a lower paracentesis frequency and is associated with improved survival. JHEP Rep. 2019;1:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Franchis R., Bosch J., Garcia-Tsao G., et al. Baveno VII – renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2022;76:959–974. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haskal Z.J., Scott M., Rubin R.A., et al. Intestinal varices: treatment with the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Radiology. 1994;191:183–187. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.1.8134568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richter G.M., Noeldge G., Palmaz J.C., et al. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt (TIPSS): results of a pilot study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1990;13:200–207. doi: 10.1007/BF02575474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moulin G., Champsaur P., Bartoli J.M., et al. TIPS for portal decompression to allow palliative treatment of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1995;18:186–188. doi: 10.1007/BF00204148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catalano G., Urbani L., De Simone P., et al. Expanding indications for TIPSS: portal decompression before elective oncologic gastric surgery in cirrhotic patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:921–923. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000180798.41704.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liverani A., Solinas L., Di Cesare T., et al. Preoperative trans-jugular porto-systemic shunt for oncological gastric surgery in a cirrhotic patient. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:997–1000. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i3.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gil A., Martínez-Regueira F., Hernández-Lizoain J.L., et al. The role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt prior to abdominal tumoral surgery in cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azoulay D., Buabse F., Damiano I., et al. Neoadjuvant transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: a solution for extrahepatic abdominal operation in cirrhotic patients with severe portal hypertension. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:46–51. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00911-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menahem B., Lubrano J., Desjouis A., et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement increases feasibility of colorectal surgery in cirrhotic patients with severe portal hypertension. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J.J., Dasika N.L., Yu E., et al. Cirrhotic patients with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt undergoing major extrahepatic surgery. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:574–579. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31818738ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain D., Mahmood E., V-Bandres M., et al. Preoperative elective transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for cirrhotic patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Ann Gastroenterol. 2018;31:330–337. doi: 10.20524/aog.2018.0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lahat E., Lim C., Bhangui P., et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt as a bridge to non-hepatic surgery in cirrhotic patients with severe portal hypertension: a systematic review. HPB (Oxford) 2018;20:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vinet E., Perreault P., Bouchard L., et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt before abdominal surgery in cirrhotic patients: a retrospective, comparative study. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:401–404. doi: 10.1155/2006/245082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabchouri N., Barbier L., Menahem B., et al. Original study: transjugular ntrahepatic portosystemic shunt as a bridge to abdominal surgery in cirrhotic patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:2383–2390. doi: 10.1007/s11605-018-4053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aryan M., McPhail J., Ravi S., et al. Perioperative transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt is associated with decreased postoperative complications in decompensated cirrhotics undergoing abdominal surgery. Am Surg. 2022;88:1613–1620. doi: 10.1177/00031348211069784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang J., Höfer P., Böhling N., et al. Preoperative TIPS prevents the development of postoperative acute-on-chronic liver failure in patients with high CLIF-C AD score. JHEP Rep. 2022;4 doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2022.100442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bureau C., Thabut D., Oberti F., et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts with covered stents increase transplant-free survival of patients with cirrhosis and recurrent ascites. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:157–163. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossle M., Ochs A., Gulberg V., et al. A comparison of paracentesis and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting in patients with ascites. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1701–1707. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006083422303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salerno F., Merli M., Riggio O., et al. Randomized controlled study of TIPS versus paracentesis plus albumin in cirrhosis with severe ascites. Hepatology. 2004;40:629–635. doi: 10.1002/hep.20364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Narahara Y., Kanazawa H., Fukuda T., et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus paracentesis plus albumin in patients with refractory ascites who have good hepatic and renal function: a prospective randomized trial. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:78–85. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fares N., Robic M.A., Péron J.M., et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement before abdominal intervention in cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension: lessons from a pilot study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:21–26. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tripathi D., Stanley A.J., Hayes P.C., et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt in the management of portal hypertension. Gut. 2020;69:1173–1192. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

:

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.