Abstract

BACKGROUND

Globally, almost 30% of women report experiencing intimate partner violence. In Australia, intimate partner violence is estimated to affect 2.0% to 4.3% of pregnant women. Those who experience intimate partner violence during pregnancy have poorer perinatal and maternal outcomes, including preterm birth, low birth weight, preterm prelabor rupture of membranes, perinatal death, miscarriage, antepartum hemorrhage, maternal trauma, and death.

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to evaluate the maternal and perinatal outcomes among women who reported intimate partner violence in a tertiary Australian hospital.

STUDY DESIGN

This was a retrospective observational study conducted between January 2017 and December 2021 at the Mater Mother's Hospital in Brisbane, Australia. The study cohort included pregnant women who completed a prenatal intimate partner violence questionnaire. Exclusion criteria included infants with known major congenital or chromosomal abnormalities.

RESULTS

Of the total study cohort comprising 45,177 births, 3242 births (7.2%) were among women who were exposed to intimate partner violence. Those who identified as Indigenous or had refugee status experienced significantly higher rates of intimate partner violence. Women exposed to intimate partner violence had greater odds of having a small for gestational age infant (adjusted odds ratio, 1.17; 95% confidence interval, 1.04–1.33), preterm birth (adjusted odds ratio, 1.21; 95% confidence interval, 1.07–1.37), preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (adjusted odds ratio, 1.23; 95% confidence interval, 1.05–1.45), and an infant with severe neonatal morbidity (adjusted odds ratio, 1.21; 95% confidence interval, 1.08–1.35). Women who reported intimate partner violence also had higher odds of acute presentation to the obstetrical assessment unit (adjusted odds ratio, 1.71; 95% confidence interval, 1.58–1.85) and admission to hospital (adjusted odds ratio, 1.44; 95% confidence interval, 1.30–1.61). When compared with non-Indigenous women exposed to intimate partner violence, Indigenous women had worse outcomes with significantly higher rates of preterm prelabor rupture of membranes, extreme preterm birth, lower gestational age at birth, low birth weight, and higher rates of infants with birth weight <fifth percentile for gestation.

CONCLUSION

Intimate partner violence is associated with increased risks for poor perinatal outcomes, particularly among those who identify as Indigenous and those with refugee status. Our results reinforce the importance of purposefully screening for intimate partner violence during pregnancy and emphasize that mitigating this risk may improve pregnancy outcomes.

Key words: adverse pregnancy outcomes, domestic violence, intimate partner violence, perinatal outcomes, pregnancy, preterm birth, small for gestational age

AJOG Global Reports at a Glance.

Why was this study conducted?

This study aimed to evaluate the maternal and perinatal outcomes among women who reported intimate partner violence in a tertiary Australian hospital.

Key findings

The overall prevalence of intimate partner violence was reported for 7.2% of all births. Almost 1 in 3 women who identified as Indigenous and 1 in 7 women with refugee status reported intimate partner violence during pregnancy. Intimate partner violence was associated with increased rates of small for gestational age infants, preterm birth, preterm prelabor rupture of membranes, severe neonatal morbidity, acute obstetrical presentations, and admission to hospital.

What does this add to what is known?

Screening for intimate partner violence during pregnancy is important and helps to identify those at risk for adverse perinatal outcomes. Indigenous women and those with refugee status are particularly vulnerable.

Introduction

The World Health Organization defines intimate partner violence (IPV) or domestic violence as behavior by an intimate or former partner that causes harm-physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse, and controlling behavior all fall under this category.1 Globally, almost 30% of women are victims,2 whereas in Australia, 17% of women have reported physical or sexual IPV and 23% reported emotional IPV with more than 1 in 2 of these women describing repeated episodes of violence.3 Regardless of gender or geography, IPV is associated with a plethora of complications, including physical trauma, chronic pain, and posttraumatic stress,4, 5, 6, 7 which leads to poorer quality of life and often more frequent use of health services by affected individuals.8

Pregnant women are a particularly vulnerable cohort-they experience higher rates of IPV,3,9 which leads to considerable adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes, including preterm birth, low birth weight, preterm pre-abor rupture of membranes, perinatal death,10,11 miscarriage,12 antepartum hemorrhage,13 maternal trauma, and death.14 In Australia, IPV is estimated to affect 2.0% to 4.3% of pregnant women15, 16, 17 although these figures are likely to be an underestimate of the true prevalence of this problem.

Against this background, the aim of this study was to evaluate perinatal outcomes among women who reported experiences consistent with exposure to IPV during pregnancy in a large Australian birth cohort.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective observational cohort study that was conducted between January 2017 and December 2021 at the Mater Mother's Hospital in Brisbane, Australia. Ethical and waiver of consent approvals were provided by the Mater Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number: HREC/18/MHS/46). The Mater Mother's Hospital is a large, tertiary, perinatal center with almost 12,000 births per annum. The study cohort included women who had completed an IPV questionnaire prenatally as part of routine antenatal care (Appendix Table A.1), which was first implemented in 2017. Pregnancies in which the fetus had a known major congenital or chromosomal abnormality were excluded.

From 2017, data on perceived family safety and exposure to physical and psychological harm were prospectively collected from all pregnant women. A positive IPV screen was defined as exposure to any form of physical, sexual, or psychological harm as indicated in the questionnaire. The questions used in the Mater questionnaire were similar to and adapted from validated questionnaires used in the healthcare context and deemed suitable for use in pregnancy,18 namely the Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream (HITS)19 and the Humiliation, Afraid, Rape, and Kick (HARK)20 questionnaires that cover various domains of domestic violence.

If IPV was identified following screening, obstetrical caregivers would follow a specified protocol. Providing that the woman gave consent, referral to a social worker and a specialist domestic family violence service was instigated. Additional information about other support services, including police and legal services, websites, and emergency hotlines, was provided. An immediate safety assessment was conducted, and a plan to ensure the safety of the woman, other children, and the family more broadly was developed.21

Data regarding maternal health, demographic, intrapartum, and birth outcomes were extracted from the woman's electronic health records (ObstetriX, Meridian Health Informatics, Surry Hills, New South Wales, Australia). Null values were assumed in the case of missing data. The demographic data that were extracted included the Socio-Economic Index for Areas (SEIFA), which is reflective of a woman's socioeconomic status22; the average score is 1000 and a lower score reflects relative socioeconomic deprivation with a score in the lowest decile being indicative of a low socioeconomic status.

The following clinical outcomes were specifically ascertained: stillbirth, neonatal death, severe neonatal morbidity, rates of small for gestational age infants, gestational age at birth, mode of birth, induction of labor, birth weight, number of acute maternity presentations, preterm prelabor rupture of membranes, preterm birth, antepartum hemorrhage, postpartum hemorrhage, and maternal intensive care unit admission.

Stillbirth was defined as any antenatal or intrapartum fetal death ≥20 weeks’ gestation. Neonatal mortality was defined as mortality within 28 days of birth. Severe neonatal morbidity was defined as a composite of severe acidosis (umbilical cord artery pH <7) and/or Apgar score <4 at 5 minutes and/or respiratory distress requiring neonatal intensive care unit admission and/or significant cardiopulmonary resuscitation at birth (ie, respiratory support, resuscitation drugs, intubation, or cardiac compressions). A small for gestational age infant was defined as one with a birth weight <10th percentile for gestation. Acute maternity presentations were defined as any nonscheduled self- or physician-referred presentation to hospital for any reason (pregnancy or nonpregnancy related complaint).

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics are presented for the maternal demographic and health characteristics and IPV. The distribution of continuous variables was assessed using histograms. Categorical data are reported as number and percentages, whereas continuous data are presented as mean (standard deviation [SD]) or median (interquartile range [IQR]). The univariable relationship between these characteristics and IPV were examined using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables.

A causal approach was used to develop a directed acyclic graph (DAG) to inform parameterization of statistical models with incorporation of published information on known causal risk factors (Figure 1). Evidence supporting the causal relationships is presented in Appendix Table A.2. Minimum sufficient adjustment sets (the minimum sets of covariates that, when adjusted for, blocked all the back-door paths between the exposure and the outcome) were determined from the DAG. A graphical tool, Dagitty, was used to examine the relationships between IPV and maternal and birth outcomes.23,24 Data were analyzed using Stata 17 (Statacorp, College Station, TX). Logistic regression analyses were used to determine odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for the effect of IPV on maternal and birth outcomes. Multivariable models were built according to the minimum sufficient adjustment sets.23

Figure 1.

Directed acyclic graph: inter-relationships among intimate partner violence and key variables

Arrowheads provide direction of influence of relationship.

Lockington. Intimate partner violence and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023.

Results

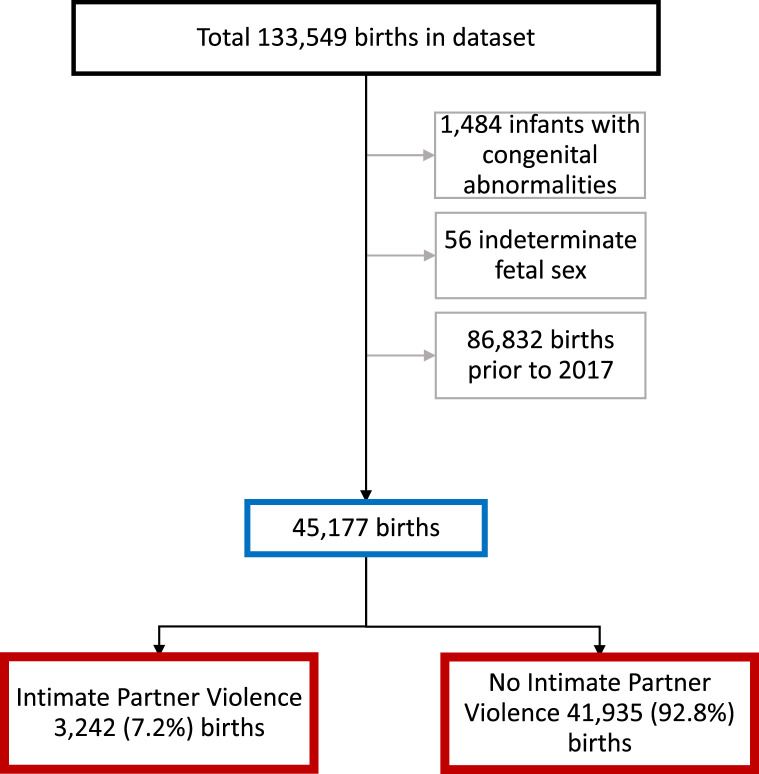

The final study cohort consisted of 45,177 births (Figure 2). Of these, 3242 (7.2%) were to women who reported IPV. Those who reported IPV were more likely to be younger, of lower socioeconomic status, multiparous, have a raised body mass index, consume alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs during pregnancy, and have hypertension or diabetes mellitus. They were less likely to have used assisted reproductive technology. Higher rates of IPV were seen among Indigenous and refugee women (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the prevalence of intimate partner violence and birth outcomes from 2017 to 2021 in Queensland, Australia

Lockington. Intimate partner violence and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023.

Table 1.

Maternal demographics and health characteristics

| Characteristics | Total births | No intimate partner violence | Intimate partner violence | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=45,177 | n=41,935 | n=3242 | ||

| Maternal age at birth | 32±5 | 32±5 | 30±7 | <.001 |

| Married de facto | 88.9% (40,150) | 90.8% (38,081) | 63.8% (2069) | <.001 |

| Maternal ethnicity | <.001 | |||

| White | 59.0% (26,590) | 58.8% (24,613) | 61.0% (1977) | |

| Asian | 23.7% (10,705) | 24.9% (10,406) | 9.2% (299) | |

| Other | 14.7% (6613) | 14.3% (5993) | 19.1% (620) | |

| Born outside Australia | 44.4% (20,054) | 45.5% (19,067) | 30.4% (987) | <.001 |

| Indigenous status | 2.6% (1188) | 2.0% (842) | 10.7% (346) | <.001 |

| Refugee | 3.3% (1475) | 3.0% (1267) | 6.4% (208) | <.001 |

| Lowest SEIFA decile | 7.0% (3140) | 6.7% (2780) | 11.2% (360) | <.001 |

| Parity | <.001 | |||

| Nulliparous | 46.2% (20,778) | 46.6% (19,424) | 41.8% (1354) | |

| Parity ≥1 | 53.8% (24,153) | 53.4% (22,271) | 58.2% (1882) | |

| Maternal BMI | 25±6 | 24±6 | 26±7 | <.001 |

| BMI categoriesa | <.001 | |||

| Underweight | 6.3% (2834) | 6.3% (2595) | 7.4% (239) | |

| Normal Weight | 57.8% (25,807) | 58.5% (24,237) | 48.5% (1570) | |

| Overweight | 21.4% (9568) | 21.3% (8846) | 22.3% (722) | |

| Obese | 14.5% (6470) | 13.9% (5762) | 21.9% (708) | |

| Alcohol Consumption during pregnancy | 3.9% (1754) | 3.6% (1504) | 7.7% (250) | <.001 |

| Smoking in pregnancy | 7.9% (3575) | 6.6% (2781) | 24.5% (794) | <.001 |

| Illicit drug use in pregnancy | 1.7% (747) | 1.0% (424) | 10.0% (323) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 4.7% (2115) | 4.6% (1939) | 5.4% (176) | .037 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11.7% (5296) | 11.7% (4893) | 12.4% (403) | .19 |

| Use of ART | 9.9% (4483) | 10.2% (4278) | 6.3% (205) | <.001 |

| EPDS score ≥12 | 8.9% (2054) | 6.9% (1452) | 28.7% (602) | <.001 |

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation or median (interquartile range) for continuous measures, and percentage (number) for categorical measures.

ART, assisted reproductive technology; ATSI, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander; BMI, body mass index; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; SEIFA, Socio-Economic Indexes for Area.

The BMI categories were defined according to the World Health Organization standard classification as follows: underweight BMI <18.5kg/m2, normal BMI, 18.5–24.99kg/m2, overweight BMI, 25–29.99kg/m2, obese BMI ≥30kg/m2.

Lockington. Intimate partner violence and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023.

The obstetrical and perinatal outcomes are outlined in Table 2. There was no difference in the stillbirth or neonatal death rates between women exposed to IPV and the controls. However, rates of severe neonatal morbidity were higher in the IPV cohort. Induction of labor and spontaneous vaginal birth rates were also greater in the IPV group. Preterm birth rates (<37 weeks’ gestation) and the number of small for gestational age infants (birth weight <10th and <5th percentile) were significantly higher among women who experienced IPV, however, there was no difference in the rates of planned preterm birth. There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of maternal outcomes, including postpartum hemorrhage or maternal intensive care unit admission.

Table 2.

Obstetrics and perinatal outcomes stratified by the presence of intimate partner violence

| Outcome | Total | No intimate partner violence | Intimate partner violence | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=45,177 | n=41,935 | n=3242 | ||

| Stillbirth | 0.7% (295) | 0.7% (277) | 0.6% (18) | .47 |

| Neonatal death | 0.1% (54) | 0.1% (52) | 0.1% (2) | .32 |

| Acidosis at birth (pH <7 or base excess <−12) | 0.3% (127) | 0.3% (117) | 0.3% (10) | .76 |

| Apgar score <4 at 5 min | 0.6% (282) | 0.6% (263) | 0.6% (19) | .77 |

| Severe respiratory distress | 10.5% (4737) | 10.4% (4344) | 12.1% (393) | .002 |

| Significant cardiopulmonary resuscitation | 1.8% (808) | 1.8% (741) | 2.1% (67) | .21 |

| NICU or ICN admission | 3.1% (1325) | 3.1% (1223) | 3.4% (102) | .40 |

| Composite severe neonatal morbidity | 11.6% (5237) | 11.4% (4798) | 13.5% (439) | <.001 |

| Method of delivery | <.001 | |||

| SVB | 47.2% (21,308) | 46.7% (19,580) | 53.3% (1728) | |

| Instrumental birth (vacuum or forceps) | 12.6% (5679) | 12.8% (5357) | 9.9% (322) | |

| Elective CD | 21.3% (9606) | 21.5% (9002) | 18.6% (604) | |

| Emergency CD | 19.0% (8565) | 19.0% (7978) | 18.1% (587) | |

| Not recorded | 0.0% (6) | 0.0% (6) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Emergency CD indication NRFS | 34.5% (2954) | 34.6% (2760) | 33.0% (194) | .45 |

| IOL | 35.2% (15,882) | 34.9% (14,641) | 38.3% (1241) | <.001 |

| Median birth weight (g) | 3320 (2976–3642) | 3324 (2980–3644) | 3290 (2909–3624) | <.001 |

| Birth weight <10th percentile | 9.6% (4328) | 9.5% (3979) | 10.8% (349) | .017 |

| Birth weight <5th percentile | 4.9% (2220) | 4.8% (2030) | 5.9% (190) | .010 |

| Number of acute presentations | <.001 | |||

| 1 | 28.1% (12,696) | 28.3% (11,868) | 25.5% (828) | |

| 2 | 14.3% (6461) | 14.1% (5905) | 17.1% (556) | |

| 3 | 7.3% (3289) | 7.1% (2962) | 10.1% (327) | |

| 4 | 3.4% (1547) | 3.2% (1338) | 6.4% (209) | |

| 5 | 1.7% (789) | 1.6% (678) | 3.4% (111) | |

| >5 | 2.0% (915) | 1.7% (722) | 6.0% (193) | |

| >1 acute presentations | 56.9% (25,697) | 56.0% (23,473) | 68.6% (2224) | <.001 |

| PPROM | 5.1% (2320) | 5.1% (2122) | 6.1% (198) | .009 |

| Median GA at birth (d) | 273 (266–279) | 273 (266–280) | 272 (265–278) | <.001 |

| Preterm birth <28 wk | 1.2% (553) | 1.3% (529) | 0.7% (24) | .009 |

| Preterm birth <32 wk | 1.5% (691) | 1.5% (633) | 1.8% (58) | .21 |

| Preterm birth <37 wk | 8.0% (3604) | 7.8% (3282) | 9.9% (322) | <.001 |

| Planned preterm birth | 34.1% (1652) | 34.4% (1527) | 30.9% (125) | .16 |

| APH | 3.2% (435) | 3.3% (403) | 2.6% (32) | .23 |

| Primary PPH ≥1500 mLa | 17.5% (545) | 17.3% (494) | 20.0% (51) | .27 |

| Maternal ICU admission | 0.5% (205) | 0.5% (190) | 0.5% (15) | .94 |

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation or median (interquartile range) for continuous measures and percentage (number) for categorical measures.

APH, antepartum hemorrhage; CD, cesarean delivery; GA, gestational age; ICN, intensive care nursery; ICU, intensive care unit; IOL, induction of labor; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; NRFS, nonreassuring fetal status; PPH, postpartum hemorrhage; PPROM, preterm prelabor rupture of membranes; SNM, severe neonatal morbidity; SVB, spontaneous vaginal birth.

PPH is a blood loss volume of >1500 mL––for major PPH with moderate shock or greater, the national guidelines recommend that the subject should undergo formal clinical incident review.

Lockington. Intimate partner violence and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023.

After adjustment for confounders, women who reported IPV had greater odds of having a small for gestational age infant (adjusted OR [aOR], 1.17; 95% CI, 1.04–1.33), preterm birth (aOR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.07–1.37), preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (aOR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.05–1.45), and severe neonatal morbidity (aOR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.08–1.35). They also had higher odds of having an Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) score ≥12 (aOR, 5.44; 95% CI, 4.86–6.09), more frequent acute obstetrical hospital presentations (aOR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.58–1.85), and hospital admission (aOR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.30–1.61) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable analyses of the effect of intimate partner violence on obstetrical and perinatal outcomes

| Outcome | Univariable odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stillbirth | 0.84 (0.51–1.39) | .50 | 0.89 (0.54–1.47) | .65 |

| Neonatal death | 0.50 (0.12–1.99) | .32 | 0.52 (0.13–2.16) | .37 |

| Severe neonatal morbidity | 1.21 (1.09–1.35) | <.001 | 1.21 (1.08–1.35) | .001 |

| Acidosis (pH <7 or base excess <−12) | 1.10 (0.58–2.11) | .76 | 1.07 (0.56–2.03) | .85 |

| Apgar score <4 at 5 min | 0.93 (0.58–1.49) | .77 | 0.96 (0.60–1.54) | .88 |

| Severe respiratory distress | 1.19 (1.07–1.34) | .002 | 1.19 (1.06–1.33) | .003 |

| Significant neonatal resuscitation | 1.17 (0.90–1.53) | .23 | 1.19 (0.91–1.55) | .21 |

| NICU or ICN Admission | 1.09 (0.89–1.34) | .40 | 1.08 (0.88–1.34) | .45 |

| IOL | 1.16 (1.07–1.25) | <.001 | 1.16 (1.08–1.26) | <.001 |

| Instrumental delivery (vacuum or forceps) | 0.75 (0.67–0.85) | <.001 | 0.78 (0.69–0.88) | <.001 |

| Emergency CD | 0.94 (0.86–1.04) | .21 | 0.96 (0.87–1.05) | .37 |

| Emergency CD for NRFS | 0.93 (0.78–1.12) | .46 | 0.95 (0.79–1.15) | .62 |

| Elective CD | 0.84 (0.76–0.92) | <.001 | 0.84 (0.76–0.92) | <.001 |

| Birth weight <10th percentile | 1.15 (1.02–1.30) | .02 | 1.17 (1.04–1.33) | .01 |

| Birth weight <5th percentile | 1.22 (1.04–1.44) | .01 | 1.24 (1.05–1.46) | .01 |

| EPDS score ≥12 | 5.42 (4.85–6.05) | <.001 | 5.44 (4.86–6.09) | <.001 |

| >1 acute presentation | 1.72 (1.59–1.86) | <.001 | 1.71 (1.58–1.85) | <.001 |

| PPROM | 1.22 (1.04–1.43) | .01 | 1.23 (1.05–1.45) | <.01 |

| PTB <37 weeks’ gestation | 1.30 (1.14–1.48) | <.001 | 1.29 (1.12–1.47) | <.001 |

| Planned PTB <37 wk | 0.86 (0.67–1.10) | .22 | 0.83 (0.65–1.07) | .16 |

| Admission to hospital after acute presentation | 1.47 (1.32–1.63) | <.001 | 1.44 (1.30–1.61) | <.001 |

| APH | 0.80 (0.55–1.16) | .24 | 0.82 (0.56–1.21) | .32 |

| PPH >1500 mLb | 1.20 (0.87–1.66) | .27 | 1.19 (0.85–1.64) | .31 |

| Maternal ICU admission | 1.02 (0.60–1.73) | .94 | 1.02 (0.60–1.74) | .93 |

APH, antepartum hemorrhage; CD, cesarean delivery; CI, confidence interval; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; ICN, intensive care nursery; ICU, intensive care unit; IOL, induction of labor; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; NRFS, nonreassuring fetal status; PPH, postpartum hemorrhage; PPROM, preterm prelabor rupture of membranes; PTB, preterm birth.

Adjusted for socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and refugee status

PPH defined as blood loss >1500 mL––for major PPH with moderate shock or greater, the national guidelines recommend that the subject should undergo formal clinical incident review.

Lockington. Intimate partner violence and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023.

Among Indigenous women, 29.1% experienced IPV. Within the IPV cohort, when Indigenous women were compared with non-Indigenous women, they were more likely to be younger, in the lowest SEIFA decile, multiparous, underweight or obese, smoke, and have an EPDS score ≥12. They were also less likely to be married or in a de facto relationship. Within the cohort of Indigenous women only, rates of smoking and illicit drug use were increased in the IPV cohort (42.2% vs 29.6% and 21.7% vs 8.2%, respectively). When compared with non-Indigenous women, Indigenous women who were exposed to IPV had worse perinatal outcomes with higher rates of preterm prelabor rupture of membranes, extreme preterm birth, a lower median gestational age at birth, low birth weight, and higher rates of infants with birth weight <fifth percentile. However, regardless of whether IPV was present or not, there was no difference in the perinatal outcomes within the cohort of Indigenous women (Appendix B, Tables 1–4).

Discussion

Principal findings and clinical implications

The results of this large, single-center Australian study showed that the prevalence of IPV during pregnancy was 7.2% among all births, a figure that is consistent with other international centers.25 Our results also showed that IPV in pregnancy is a risk factor for preterm birth and is strongly associated with increased odds of severe neonatal morbidity, preterm prelabor rupture of membranes, and birth of a small for gestational age infant. Women who experienced IPV were also more likely to have an EPDS score >12, indicative of an increased risk for mental health issues,26 and more likely to have multiple presentations to an acute obstetrical service and admission to hospital. Our results also demonstrated that almost 1 in 3 Indigenous and 1 in 7 refugee women reported IPV during pregnancy.

The global estimates of IPV during pregnancy range between 3.9% and 8.7%.25 However, the true prevalence of this problem is highly likely to be underestimated because of its nature, different definitions, and the varied screening and reporting methods used in disparate populations.27 Often, information is derived from telephonic or face-to-face surveys or cross-sectional household data.25 The World Health Organization has noted that clinical studies often identify a higher prevalence28 with 1 review reporting IPV rates of 3.4% to 11% during pregnancy in high-income countries and up to 31.5% in low- and middle-income countries.29 Indeed, a recent publication reported that more than half of Iranian women experienced some form of IPV during pregnancy.30 Often, low- and middle-income countries have a turbulent and insecure political, social, and economic climate, which can be further exacerbated in times of conflict.31 This can lead to conditions that limit a victim's ability to leave an abusive relationship, including economic insecurity, gender inequitable norms, high amounts of societal stigma, and inadequate support services.31

A 2016 review that included 50 studies across 17 countries showed that IPV was significantly associated with preterm birth (OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.60–2.29) and low birth weight (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.68–2.65), although a large level of heterogeneity was present.10 Our study also found similar associations between IPV and increased odds for preterm birth and small for gestational age infants. However, although the 2016 review examined the effect of different types of IPV (showing a stronger association when 2 types of IPV were present), our study did not differentiate between types or combinations of IPV. A recent publication from Western Australia32 that used data from the Police Force Incident Management System and hospital morbidity data collection showed that neonates born to women who were antenatally exposed to family and domestic violence had higher odds of congenital malformations (OR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.18–1.94), low birth weight (OR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.45–2.10), and preterm birth (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.22–1.79); some of these results are consistent with our study in which a large hospital database was used.

A 2019 meta-analysis of >32 million women demonstrated a 3-fold increase in the odds of perinatal death among women who were exposed to unspecified IPV (OR, 3.18; 95% CI, 1.88–5.38), physical IPV (OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.76–3.44), and any type of IPV during pregnancy (OR, 2.89; 95% CI, 2.03–4.10).11 Although we have not shown a similar association, this is possibly because our sample size, which, although large, is probably insufficient to detect rare outcomes such as perinatal death.33

Our findings of high EPDS scores among women exposed to IPV is likely reflective of increased anxiety and depression in this cohort. This finding is supported by other publications34, 35, 36 from diverse geographical and socioeconomic settings that show high levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety and posttraumatic stress,36 reduced breast feeding rates,37 and suicide38 among pregnant women who experience IPV. A recent large systematic review and meta-analysis found that the highest prevalence of perinatal depression was found among women who experienced IPV (38.9%; 95% CI, 34.1%–43.6%).39

Within Australia, Indigenous communities experience higher rates of family violence-both potentially a cause and effect of social disadvantage and intergenerational trauma as a consequence of colonization and its ongoing effects.3 Our study also found higher rates of IPV during pregnancy among Indigenous women, and when compared with non-Indigenous women who experienced IPV, they had higher rates of extreme preterm birth (<28 weeks’ gestation), a lower median birth weight, and higher rates of low birth weight and preterm prelabor rupture of membranes. This disparity in health outcomes is one of the motivations underpinning national public health initiatives such as Closing the Gap40 in an attempt to address these inequities. Closing the Gap is an Australian Government social justice campaign launched in 2007 that aims to close the health and life expectancy gap between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous Australians and focuses on 17 key socioeconomic outcomes.

Depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and mood disorders have all been associated with IPV exposure6,41 with some studies reporting high PTSD prevalence rates (weighted OR, 3.74) among women who were exposed to IPV.6 In addition, rates of alcohol consumption, drug abuse,41 and smoking42 are higher among individuals exposed to IPV. Suggested explanations for the increased substance use involve maladaptive coping mechanisms for the physical and emotional pain of relationship distress and IPV.42 These aberrant coping mechanisms are also postulated to explain why women who experience IPV have higher rates of obesity.43 Indeed, our results showed that pregnant women with obesity are at a significantly increased risk for IPV in pregnancy. This is an important finding, because regardless of IPV, this cohort is already at increased risk for poorer maternal and infant health outcomes.44 Several studies have suggested a link between IPV and metabolic45 and cardiovascular disease46,47 in the nonpregnant population-the presence of physical or sexual violence increases the risk fo abdominal obesity, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and elevated triglycerides.47 Pheiffer et al45 identified IPV as a risk factor for gestational diabetes mellitus-a proposed biologic mechanism is IPV-induced stress and depression that lead to dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which leads to the hypersecretion of cortisol and the subsequent development of insulin resistance. We, however, did not find higher rates of gestational diabetes mellitus in our IPV cohort.

Research implications

Detection of IPV during pregnancy is crucial so that the necessary support can be provided to the victims. A recent study from North America showed that among postnatal women who reported physical IPV, nearly half were not screened for IPV before or after pregnancy, suggesting that public health measures to improve maternal and child health should address both access to care and universal screening for IPV. However, the merits of universal screening is unclear with a Cochrane review by O’ Doherty et al48 showing that although universal screening increased IPV identification, this had no clear effect on either the subsequent referrals for maternal support or an actual decrease in the rates of abuse. Nevertheless, many national and international organizations support and recommend routine screening for IPV in the antenatal period, because identifying at risk women provides an opportunity for engagement and ongoing work toward improvements in maternal, infant, and child outcomes.49,50 It has been shown that when IPV screening is done sensitively and by trained staff it does not cause any serious harm.51 Furthermore, even if women who had a positive screen do not accept immediate help, being identified helps to reduce the taboo and sense of isolation and increases their perception of support.52 Although the impact on maternal and childhood outcomes is increasingly evident, there is much that we do not know or understand. Worryingly, recent studies suggest that antenatal maternal IPV exposure is associated with sex-specific alterations in the brain structure among young infants.53 If this finding is validated in other studies, the long-term impact on individuals exposed to maternal IPV in utero may be considerable.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the relatively large study population and the use of contemporary data up to December 2021. Information regarding IPV was also prospectively collected during each pregnancy. For women who did not speak English, suitable interpreters were used. We also focused on clinically important maternal and perinatal outcomes. Limitations of this study include its retrospective nature and the use of a questionnaire for screening at routine antenatal visits, which may underestimate the true prevalence or acuity of IPV. Although the screening questions inquired about current maternal exposure to IPV, some of the questions were sufficiently broad that the timeline of exposure of IPV was unclear. We did not examine different types of IPV-physical, emotional, sexual-and therefore the magnitude of effect for a specific type of IPV on clinical outcomes is unclear. Because maternal outcomes were not the primary focus of this study, we are unable to comment in more detail on the impact of IPV on women beyond intensive care unit admissions and postpartum hemorrhage. We also did not investigate the impact of COVID-19 on IPV rates or perinatal outcomes. More recently, evidence from police reports, online surveys, and the number of calls to victim hotlines and charities suggests that restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic have potentially led to an exacerbation of this problem17 with increased severity of IPV and new cases of IPV arising in previously healthy relationships.54 It is postulated that strict lockdown measures may have forced women and their IPV perpetrators into persistent close proximity with each other and thus increasing the potential for abuse. Exacerbation of other risk factors and limited access to support services have increased the vulnerability of pregnant women to IPV and its sequelae.

Conclusion

Our main findings of an association between IPV in pregnancy and increased risks for severe neonatal morbidity, preterm prelabor rupture of membranes, birth of a small for gestational age infant, maternal mental health issues, preterm birth, increased use of maternity services, and hospital admission highlight the importance of purposefully screening for IPV in this population. Our findings also highlight specific cohorts (Indigenous and refugee women) who are particularly vulnerable during pregnancy and require an immediate safety assessment and plan for themselves, their children, and unborn child. These women may also require culturally sensitive interpreters or health workers to obtain the relevant history and facilitate subsequent referral to appropriate support services and preventive interventions.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Veronika Schreiber, MBiostat, in the preparation of the original data set.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

S.K. was supported by the Mater Foundation and received research funding from the Australian Medical Research Future Fund and the National Health and Medical Research Council.

None of the funding parties had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

All code, scripts, and data used to produce the results in this article will be available to any researcher provided that the appropriate ethics approval, interinstitutional data sharing agreements, and other regulatory requirements are in place.

Patient consent was not required because no personal information or details were included.

Cite this article as: Lockington EP, Sherrell HC, Crawford K, et al. Intimate partner violence is a significant risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023;XX:x.ex–x.ex.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.xagr.2023.100283.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Violence against women. 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women. Accessed December 20, 2022.

- 2.World Health Organization. Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256. Accessed December 20, 2022.

- 3.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia, 2018. 2018. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/domestic-violence/family-domestic-sexual-violence-in-australia-2018/summary. Accessed December 20, 2022.

- 4.Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Rivara FP, Thompson RS. Health outcomes in women with physical and sexual intimate partner violence exposure. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16:987–997. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonomi AE, Thompson RS, Anderson M, et al. Intimate partner violence and women's physical, mental, and social functioning. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:458–466. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23:260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, et al. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1157–1163. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drexler KA, Quist-Nelson J, Weil AB. Intimate partner violence and trauma-informed care in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2022;4 doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donovan BM, Spracklen CN, Schweizer ML, Ryckman KK, Saftlas AF. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and the risk for adverse infant outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2016;123:1289–1299. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pastor-Moreno G, Ruiz-Pérez I, Henares-Montiel J, Petrova D. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and risk of fetal and neonatal death: a meta-analysis with socioeconomic context indicators. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.07.045. 123–33.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pastor-Moreno G, Ruiz-Pérez I, Henares-Montiel J, Escribà-Agüir V, Higueras-Callejón C, Ricci-Cabello I. Intimate partner violence and perinatal health: a systematic review. BJOG. 2020;127:537–547. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khaironisak H, Zaridah S, Hasanain FG, Zaleha MI. Prevalence, risk factors, and complications of violence against pregnant women in a hospital in Peninsular Malaysia. Women Health. 2017;57:919–941. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2016.1222329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devineni K, Kumari S, Sodumu N, Garg R. Effects of intimate partner violence on pregnancy outcome. S Asian Feder Obst Gynae. 2018;10:142–148. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaves K, Eastwood J, Ogbo FA, et al. Intimate partner violence identified through routine antenatal screening and maternal and perinatal health outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:357. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2527-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahlen HG, Munoz AM, Schmied V, Thornton C. The relationship between intimate partner violence reported at the first antenatal booking visit and obstetric and perinatal outcomes in an ethnically diverse group of Australian pregnant women: a population-based study over 10 years. BMJ Open. 2018;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotlar B, Gerson EM, Petrillo S, Langer A, Tiemeier H. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal health: a scoping review. Reprod Health. 2021;18:10. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Australian Institute of Health Welfare. Screening for domestic violence during pregnancy: options for future reporting in the National Perinatal Data Collection. 2015. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/screening-for-domestic-violence-during-pregnancy. Accessed June 19, 2023.

- 19.Sánchez ODR, Tanaka Zambrano E, Dantas-Silva A, et al. Domestic violence: a cross-sectional study among pregnant and postpartum women. J Adv Nurs. 2023;79:1525–1539. doi: 10.1111/jan.15375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sohal H, Eldridge S, Feder G. The sensitivity and specificity of four questions (HARK) to identify intimate partner violence: a diagnostic accuracy study in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Queenland Health. Domestic and family violence (DFV) resources to support the health workforce. Queenland Government. Available at: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/clinical-practice/guidelines-procedures/patient-safety/duty-of-care/domestic-family-violence/healthcare-workers. Accessed October 6, 2023.

- 22.Pink B. 2039.0 - Information Paper: An Introduction to Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA). 2006. Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/1283d7fbee2e758bca2570820000f844/2bf2ac2b6f8332c4ca2570a50015eea4!OpenDocument. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- 23.Textor J, Hardt J, Knüppel S. DAGitty: a graphical tool for analyzing causal diagrams. Epidemiology. 2011;22:745. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318225c2be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tennant PWG, Murray EJ, Arnold KF, et al. Use of directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to identify confounders in applied health research: review and recommendations. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50:620–632. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devries KM, Kishor S, Johnson H, et al. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: analysis of prevalence data from 19 countries. Reprod Health Matters. 2010;18:158–170. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(10)36533-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navaratne P, Foo XY, Kumar S. Impact of a high Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score on obstetric and perinatal outcomes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33544. doi: 10.1038/srep33544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chisholm CA, Bullock L, Ferguson JEJ., 2nd Intimate partner violence and pregnancy: epidemiology and impact. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization . Department of Reproductive Health and Research World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy Information Sheet; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell J, García-Moreno C, Sharps P. Abuse during pregnancy in industrialized and developing countries. Violence Against Women. 2004;10:770–789. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raziani Y, Hasheminasab L, Gheshlagh RG, Dalvand P, Baghi V, Aslani M. The prevalence of intimate partner violence among Iranian pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Public Health. 2022 doi: 10.1177/14034948221119641. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sardinha L, Maheu-Giroux M, Stöckl H, Meyer SR, García-Moreno C. Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. Lancet. 2022;399:803–813. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02664-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orr C, Kelty E, Fisher C, O'Donnell M, Glauert R, Preen DB. The lasting impact of family and domestic violence on neonatal health outcomes. Birth. 2023;50:578–586. doi: 10.1111/birt.12682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/stillbirths-and-neonatal-deaths. Accessed November 30, 2022.

- 34.Melby TC, Sørensen NB, Henriksen L, Lukasse M, Flaathen EME. Antenatal depression and the association of intimate partner violence among a culturally diverse population in southeastern Norway: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Midwifery. 2022;6:44. doi: 10.18332/ejm/150009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nowshad G, Jahan N, Shah NZ, et al. Intimate-partner violence and its association with symptoms of depression, perceived health, and quality of life in the Himalayan Mountain Villages of Gilgit Baltistan. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howard LM, Oram S, Galley H, Trevillion K, Feder G. Domestic violence and perinatal mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarkar NN. The impact of intimate partner violence on women's reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28:266–271. doi: 10.1080/01443610802042415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Modest AM, Prater LC, Joseph NT. Pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide: an analysis of the national violent death reporting system, 2008-2019. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:565–573. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitchell AR, Gordon H, Lindquist A, et al. Prevalence of perinatal depression in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.0069. 425–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Commonwealth. National agreement on closing the gap. Available at: https://www.closingthegap.gov.au/national-agreement/national-agreement-closing-the-gap/7-difference/b-targets/b13. Accessed November 11, 2022.

- 41.Mehr J, Bennett E, Price J, et al. Intimate partner violence, substance use, and health comorbidities among women: a narrative review. Front Psychol. 2023;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1028375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crane CA, Hawes SW, Weinberger AH. Intimate partner violence victimization and cigarette smoking: a meta-analytic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2013;14:305–315. doi: 10.1177/1524838013495962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alhalal E. Obesity in women who have experienced intimate partner violence. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:2785–2797. doi: 10.1111/jan.13797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santos S, Voerman E, Amiano P, et al. Impact of maternal body mass index and gestational weight gain on pregnancy complications: an individual participant data meta-analysis of European, North American and Australian cohorts. BJOG. 2019;126:984–995. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pheiffer C, Dias S, Adam S. Intimate partner violence: a risk factor for gestational diabetes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:7843. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chandan JS, Thomas T, Bradbury-Jones C, Taylor JB, Bandyopadhyay S, Nirantharakumar K. Risk of cardiometabolic disease and all-cause mortality in female survivors of domestic abuse. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stene LE, Jacobsen GW, Dyb G, Tverdal A, Schei B. Intimate partner violence and cardiovascular risk in women: a population-based cohort study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013;22:250–258. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Doherty L, Hegarty K, Ramsay J, Davidson LL, Feder G, Taft A. Screening women for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007007.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Department of Health and Aged Care Clinical practice guidelines: pregnancy care. Australian Government. 2021 https://www.health.gov.au/resources/pregnancy-care-guidelines Available at: Accessed April 16, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Halpern-Meekin S, Costanzo M, Ehrenthal D, Rhoades G. Intimate partner violence screening in the prenatal period: variation by state, insurance, and patient characteristics. Matern Child Health J. 2019;23:756–767. doi: 10.1007/s10995-018-2692-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nelson HD, Bougatsos C, Blazina I. Screening women for intimate partner violence: a systematic review to update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156 doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00447. 796–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang JC, Dado D, Hawker L, et al. Understanding turning points in intimate partner violence: factors and circumstances leading women victims toward change. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:251–259. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hiscox LV, Fairchild G, Donald KA, et al. Antenatal maternal intimate partner violence exposure is associated with sex-specific alterations in brain structure among young infants: evidence from a South African birth cohort. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2023;60 doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2023.101210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peitzmeier SM, Fedina L, Ashwell L, Herrenkoh TI, Tolman R. Increases in intimate partner violence during COVID-19: prevalence and correlates. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37:NP20482–NP20512. doi: 10.1177/08862605211052586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.