Abstract

Glucocorticoids are primary stress hormones that exert neuronal effects via both genomic and non-genomic signaling pathways. However, their rapid non-genomic effects and underlying mechanisms on neural activities remain elusive. In the present study, we investigated the rapid non-genomic effect of glucocorticoids on Kv2.2 channels in cultured HEK293 cells and acute brain slices including cortical pyramidal neurons and calyx-type synapses in the brain stem. We found that cortisol, the endogenous glucocorticoids, rapidly increased Kv2.2 currents by increasing the single-channel open probability in Kv2.2-expressing HEK293 cells through activation of the membrane-associated glucocorticoid receptor. Bovine serum albumin-conjugated dexamethasone, a membrane-impermeable agonist of the glucocorticoid receptor, could mimic the effect of cortisol on Kv2.2 channels. The cortisol-increased Kv2.2 currents were induced by activation of the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) 1/2 kinase, which could be inhibited by U0126, an antagonist of the ERK signaling pathway. In layer 2 cortical pyramidal neurons and the calyx of Held synapses, cortisol suppressed the action potential firing frequency during depolarization and reduced the successful rate upon high-frequency stimulation by activating Kv2.2 channels. We further examined the postsynaptic responses and found that cortisol did not affect the mEPSC and evoked EPSC, but increased the activity-dependent synaptic depression induced by a high-frequency stimulus train. In conclusion, glucocorticoids can rapidly activate Kv2.2 channels through membrane-associated glucocorticoid receptors via the ERK1/2 signaling pathway, suppress presynaptic action potential firing, and inhibit synaptic transmission and plasticity. This may be a universal mechanism of the glucocorticoid-induced non-genomic effects in the central nervous system.

Keywords: Glucocorticoid, Non-genomic effect, Kv2.2 channel, Neural activity

1. Introduction

Glucocorticoids, such as cortisol in humans and corticosterone in rats and mice, are produced by the zona fasciculata cells of the adrenal cortex in a diurnal pattern under the control of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Boyle et al., 2016; Herman et al., 2016; Lightman et al., 2020). Glucocorticoids play a crucial role in regulating metabolism, immune function, and the response to stress. They have been widely acknowledged as stress hormones, and their production markedly increases following exposure to stress (Dominguez et al., 2019; McEwen and Akil, 2020). In the mammalian brain, stress-induced elevations in glucocorticoids induce variable neuronal effects via both genomic and non-genomic signaling pathways. The genomic pathway, which has been well studied, is mainly mediated by the cytosolic glucocorticoid receptor. Activated by glucocorticoid binding, the glucocorticoid receptors undergo conformational changes and translocate to the nucleus to regulate cellular gene expression (Kadmiel and Cidlowski, 2013; Oakley and Cidlowski, 2013; Whirledge and DeFranco, 2018). For example, stress-induced increases in the glucocorticoid level induce neuronal structure changes in the hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex (McEwen et al., 2016; Gray et al., 2017). However, the non-genomic effects of glucocorticoids, which usually occur within a few minutes and depend on the membrane-associated glucocorticoid receptor (Tasker et al., 2006; Harris et al., 2019), are still not fully understood.

Increasing evidence indicates that the rapid non-genomic effects of glucocorticoids may be related to the ion channels on the cell membrane (Yu et al., 2015; Abdoul-Azize et al., 2017). A previous study showed that cortisol, the endogenous glucocorticoids, can rapidly increase the large conductance calcium and the voltage-dependent potassium currents (IK) in rat chromaffin cells (Lovell et al., 2004). Cortisol can also rapidly inhibit Kv1.3 channels in the rat paraventricular nucleus (Zaki and Barrett-Jolley, 2002) and L-type calcium channels in the tilapia prolactin cells (Hyde et al., 2004). Interestingly, the level of glucocorticoids in the brain oscillates constantly (Kalafatakis et al., 2019). Recent studies show that the ultradian rhythmicity of glucocorticoids is critical in regulating normal emotional and cognitive responses in humans (Kalafatakis et al., 2018). Glucocorticoids may regulate neural activity through rapid non-genomic effects during these fluctuations.

The Kv2 channel family, which consists of Kv2.1 and Kv2.2, plays a vital role in modulating neural excitability (Johnston et al., 2010; Liu and Bean, 2014). Kv2.1 is expressed throughout the mammalian brain (Gutman et al., 2005), whereas Kv2.2 is preferentially expressed in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) in the brain stem (Johnston et al., 2008), basal forebrain (Hermanstyne et al., 2010), and layers 2 and 5a of the neocortex (Bishop et al., 2015). The Kv2 channels are critical for maintaining high-frequency action potential (AP) firing upon intense stimulation (Johnston et al., 2008; Guan et al., 2013).

The calyx of Held synapse, a giant glutamatergic synapse located in the MNTB of the brainstem, provides great convenience for investigating both pre-and postsynaptic mechanisms of synaptic transmission (Wu et al., 2014; Baydyuk et al., 2016). Previous studies have demonstrated that Kv2.2 is highly expressed in the MNTB and involved in maintaining high-frequency AP firing by facilitating the recovery of voltage-gated sodium channels from inactivation (Johnston et al., 2008; Tong et al., 2013).

In the present study, we investigated the rapid non-genomic effect of cortisol, the endogenous glucocorticoids, on Kv2.2 channels that were overexpressed in HEK293 cells and brain slices, including cortical layer 2 pyramidal neurons and the calyx-type synapses. We found that glucocorticoids rapidly increase the Kv2.2 channel currents via the glucocorticoid receptors on the cell membrane and phosphorylation of the ERK pathway. Cortisol significantly reduces the AP firing rate in cortical pyramidal neurons and the presynaptic nerve terminals of the calyx-type synapses through Kv2.2 channels. The similar effects in the prefrontal cortex and brainstem in our results may suggest a possible universal mechanism for the rapid non-genomic glucocorticoid-induced effect in the brain.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture and transfection

Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells were purchased from the cell bank of the Chinese Academy of Science. HEK293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotic antimycotic solution (all from Gibco). As previously reported (Zhang et al., 2021), plasmids for rat Kv2.1 (NM_013186.1) and Kv2.2 (NM_054000.2) channels in pEGFPN1 vectors were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells using jetPRIME (Polyplus). For patch clamp recordings, the cells were used after 24 h transfection.

2.2. Animal and slice preparation

Brain slices containing the prefrontal cortex (PFC) were prepared from C57/BL mice of either sex from postnatal week 3. Mice were anesthetized using pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg) and decapitated. The whole brain was transferred into ice-cold low calcium artificial cerebrospinal fluid solution (ACSFPFC) and bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2 containing (in mM): 220 sucrose, 3 KCl, 5 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 glucose. For electrophysiological recordings, 200-μm coronal slices were prepared using a vibratome (VT 1200s, Leica, Germany). Slices were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in normal ACSFPFC containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 26.2 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.5 MgSO4, 1 NaH2PO4, 2.5 CaCl2, and 11 glucose (95% O2/5% CO2).

Brainstem slices containing the MNTB were prepared from postnatal days 8–10 (p8 – p10) Sprague Dawley rats of either sex as reported previously (Liu et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020). The pups were killed by decapitation, and a block of brain tissue containing the brainstem was quickly placed into the ice-cold low calcium solution (ACSFcalyx), containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 0.05 CaCl2, 3 MgCl2, 25 glucose, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 0.4 L-ascorbic acid, 3 myo-inositol, and 2 Na-pyruvate (95% O2/5% CO2). For electrophysiological recordings, 200-μm coronal slices were prepared using a vibratome (VT 1200s, Leica, Germany). Slices were incubated for at least 30 min at 37 °C in normal ACSFcalyx containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 25 glucose, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 0.4 L-ascorbic acid, 3 myo-inositol, and 2 Na-pyruvate (95% O2/5% CO2).

All studies were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of Fudan University. All surgeries were performed under sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) anesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering.

2.3. Electrophysiology

Whole-cell potassium currents in HEK293 cells and cortical layer 2 pyramidal neurons were recorded using an Axopatch 200B or Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, USA). The extracellular solution contained (in mM): 135 NaCl, 3 KCl, 0.001 TTX, 10 glucose, 5 4-AP, 10 HEPES, and 2 MgCl2, pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH. The pipette (4–6 MΩ) solution contained (in mM): 135 K-gluconate, 10 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 2 Mg-ATP, and 10 EGTA, pH 7.3 adjusted with KOH. Whole-cell potassium currents were sampled at 10 kHz and filtered at 2 kHz. A 200-ms depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV was applied to induce a potassium current in HEK293 cells and cortical pyramidal neurons. To analyze the steady-state activation and inactivation of Kv2.2 currents, the normalized conductance or currents was fitted using the Boltzmann equation: G/Gmax = A2 + (A1 − A2)/(1 + exp((Vm − V1/2)/slope factor)). For cortical pyramidal neuron AP recordings, cortical slices were perfused in normal ACSFPFC solution; the pipette (3–5 MΩ) solution contained (in mM): 150 K-gluconate, 10 HEPES, 8 NaCl, 0.4 EGTA, 0.1 Na3-GTP, and 2 Mg-ATP, pH 7.3 adjusted with KOH. A 1 s, 200-pA current was injected to induce AP trains.

Single-channel recordings were made for the Kv2.2 channel in HEK293 cells using cell-attached mode in Axopatch 200B amplifier with Digidata 1550B (Molecular Devices, USA), acquisition at 10 kHz, and filtering at 2 kHz. The extracellular and pipette solutions were the same as for the whole-cell recording in HEK293 cells. For leak subtractions, null sweeps (traces with no channel opening) were averaged and subtracted from the recordings. Single-channel analysis was accomplished with Clampfit10.7 (Molecular Devices, USA). The unitary conductance was determined from the slope of the linear fit of the channel current induced by depolarizing from −110 to +10 mV (20 mV step). To evaluate the potassium channel open probability, the patches were depolarized from the resting membrane potential (around −70 mV) to test potentials of +10 mV for 400 ms. The open probability was calculated from the total channel opening time divided by the duration of the depolarizing stimulus.

Measurements of presynaptic IK and APs at the nerve terminal of the calyx-type synapse were taken with a sampling rate of 20 kHz using an EPC-10 amplifier (HEKA, Germany). To isolate the presynaptic Kv2.2 currents, TTX (1 μM) and 4-AP (5 mM) were added to the normal ACSFcalyx solution, substituting for NaCl with equal osmolarity. The presynaptic pipette (3–4 MΩ) solution contained (in mM): 125 K-gluconate, 20 KCl, 4 Mg-ATP, 10 Na2-phosphocreatine, 0.3 Na3-GTP, 10 HEPES, and 0.5 EGTA, pH 7.2 adjusted with KOH. The series resistance (<10 MΩ) was compensated by 65% (10 μs lag). A 200-ms depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV was applied to induce a potassium current. A 1 ms, 100–300 pA current was injected to evoke single presynaptic AP or AP trains. Burst firing was defined as a series of two or more APs with <10 ms intervals (Omura et al., 2015; Raus Balind et al., 2019).

For postsynaptic recordings at the principal neuron of calyx-type synapse, the excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) and miniature EPSC (mEPSC) were recorded with an EPC-10 amplifier. The postsynaptic pipette (2–3 MΩ) solution contained the same components as the presynaptic pipette solution, and the series resistance (<10 MΩ) was compensated by 90% (10 μs lag). The EPSC was induced as described previously (Xue and Wu, 2010; Liu et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020). Briefly, a bipolar electrode was placed at the midline of the MNTB. A pair of 0.1 ms, 2–20 V stimuli with 20 ms interval was applied every 10 s, and the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) was calculated as the second EPSC (EPSC2) divided by the first EPSC (EPSC1) (Wu et al., 2020). The EPSC40/EPSC1 ratio was calculated as the average of the last 10 EPSCs (EPSC31-EPSC40) divided by the EPSC1 (Sun et al., 2006). The mEPSC was recorded at a holding potential of −80 mV with 50 μM APV, 0.5 μM TTX, and 10 μM bicuculline in the extracellular solution. All of the electrophysiological recordings mentioned above were performed at room temperature (22–24 °C).

Cortisol (S1696, Selleck, USA), RU486 (mifepristone, S2606, Selleck, USA), and U0126 (S1102, Selleck, USA) were purchased from Selleck Chemicals. Dexamethasone (D4902, Sigma, USA), H-89 (B1427, Sigma, USA) and corticosterone (235135, Sigma, USA) were purchased from Sigma. Dexamethasone-BSA was purchased from Qiyue biotech. Bisindolylmaleimide I (HY-13867, MCE, USA) was purchased from MCE. TTX (14964, Cayman Chemical, USA) was purchased from Cayman Chemical. Staurosporine (ab120056, Abcam, UK) was purchased from Abcam. All drugs were dissolved in DMSO with a final concentration not exceeding 0.1%. Unless otherwise specified, all control groups were treated with 0.1% DMSO. The Kv2.1 (ab192761, Abcam, UK) and Kv2.2 (APC-120, Alomone, IL) antibodies were purchased from Abcam and Alomone Labs, respectively.

2.4. Lentiviral production and injection

Oligonucleotides specifying the shRNA was 5′-ATGGCAGAAAAGGCACCTCCTG GC-3′, and the scramble oligonucleotides was 5′-AAAGAACGGACCTCCCGGTCGGTA-3′. The shRNA hairpin sequences were inserted into MluI-ClaI sites of pLVTHM targeting vector. Lentivirus was produced in 293T cells using a packaging vector psPAX2, and an envelope plasmid, pMD2.G, as reported previously (Yang et al., 2016). The knockdown efficiency of the shRNA was tested in HEK293 cells transfected with Kv2.2 by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Mice were anesthetized using pentobarbital sodium, and 1 μL virus was injected into the prefrontal cortex using a microsyringe pump. Three weeks after injection, layer 2 cortical pyramidal neurons with fluorescence were used for patch clamp recording.

2.5. RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR were performed as previously reported (Yang et al., 2016). Briefly, qRT-PCR was performed in 20 μL reactions containing: 2 μL of template, 0.4 μmol/L of each paired primer, and SYBR Green Polymerase Chain Reaction master mix. The thermocycling conditions were 94 °C, 10 min; 38 cycles of 94 °C, 30 s; 55 °C, 30 s; 72 °C, 30 s; and 72 °C, 8 min. Results were normalized by β-actin mRNA. Data were calculated by 2−ΔΔCt method and reported as fold change over control. Primers used in PCR: Kv2.2: forward 5′-CACCTGGCTTGAACAGAAAG, reverse 5′-TTGCTTCGGATAATGTCCAC; β-actin: forward 5′-GTGGACATCCGCAAAGAC, reverse 5′-AAAGGGTGTAACGC AACTAA.

2.6. Western blot

The mouse brain slices were incubated with cortisol for 5 min, and then the outmost layer (∼1-mm-thick) of the slices was cut off and collected for the Western blot experiments. HEK293 cells were treated with cortisol for 5 min. The homogenates of the cortical slices or HEK293 cell homogenates were prepared using a HEPES-NP40 lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 0.1 mM Na3VO4) with protease inhibitor (P8340, Sigma, USA) and phosphatase inhibitor (P5726, Sigma, USA) cocktail. For cell surface expression experiments, HEK293 cell membrane proteins were isolated using the membrane protein extraction kit (P0033, Beyotime, China). The protein samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to polyvinyldifluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, USA). The membranes were blocked with 10% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C (anti-ERK, 1:1000, 4695S, Cell Signaling Technology, USA; anti-pERK, 1:1000, 4370S, Cell Signaling Technology, USA; anti-beta-tubulin, 1:1000, M20005, Abmart, China). The blots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents and imaged using the ChemiDoc XRS + imaging system from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA) and manufacturer's software. Molecular weight marker and chemiluminescent signal images were automatically overlaid by the manufacturer's software. The Western blot images were presented according to the recommendations from the report (Kroon et al., 2022).

2.7. Data analysis

The IK, AP waveform, and EPSCs were measured using Igor Pro (v9.0.1, WaveMetrics, USA), and mEPSCs were measured with Mini Analysis (v6.07, Synaptosoft, USA). ImageJ (v1.53, NIH, USA) was used for quantitative analysis of the Western blot experiments. ERK expression was normalized to the expression of beta-tubulin.

Data are given as the mean ± SEM; n indicates the number of cells tested or independent experiments in Western blot. Paired Student's t-test was used to compare two samples, and one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test was used to compare multiple samples. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Igor Pro and GraphPad Prism (v9.4, GraphPad Software Inc, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Glucocorticoids increase Kv2.2 currents in HEK293 cells

To investigate the rapid non-genomic effects of glucocorticoids, we examined whether glucocorticoids could regulate the activity of Kv2.2 channels. Rat Kv2.2 channels were overexpressed in HEK293 cells and the Kv2.2 currents induced by a 200-ms depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV. Extracellular application of cortisol, the endogenous glucocorticoids, rapidly increased the Kv2.2 currents in a concentration-dependent manner within 5 min, suggesting a rapid non-genomic effect (Ctrl, normalized, with 0.1% DMSO: 100 ± 2.1%; n = 6; 0.1 μM: 113.2 ± 2.7%; n = 6; p = 0.1669; 1 μM: 123.4 ± 4.7%; n = 6; p = 0.0011; 10 μM: 135.8 ± 4.4%; n = 7; p < 0.0001; 50 μM: 140.8 ± 2.7%; n = 6; p < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 1A–C). The increase in Kv2.2 current reached a plateau in the presence of 10 μM cortisol in the extracellular solution (10 μM Vs 50 μM: p > 0.9999; Fig. 1C); therefore, we used 10 μM cortisol for the subsequent experiments unless noted otherwise. Since the primary glucocorticoid in rats and mice is corticosterone, we also investigated whether cortisol and corticosterone exert similar effects. Extracellular application of 10 μM corticosterone induced a similar stimulatory effect on Kv2.2 currents to that of cortisol (126.1 ± 2.2%; n = 5; p = 0.0129, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Glucocorticoids increase Kv2.2 currents in HEK293 cells.

(A) Representative Kv2.2 current traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV under the control condition (with 0.1% DMSO, black) and subsequently in the presence of 10 μM cortisol (red) in the same HEK293 cell. Cortisol was applied to the extracellular solution and recordings taken at an interval of 10 s. (B) Cortisol (10 μM) induced a rapid increase in Kv2.2 current within 5 min. (C) Cortisol increased Kv2.2 currents in a concentration-dependent manner (n = 6–7 for each concentration). The p values were calculated using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. (D) Left, representative Kv2.2 current traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV under the control condition (black) and in the presence of 10 μM corticosterone (red) in the same HEK293 cell. Right, statistics for the IK amplitude using a paired Student's t-test (n = 5). *p < 0.05. (E) Left, representative IK traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV under the control condition (black), in the presence of Kv2.2-specific antibody (1:200) in the pipette solution (blue), and in the presence of an additional 10 μM cortisol (red) in the same HEK293 cells transfected with Kv2.2. Right, statistics for the IK amplitude using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. ***p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. (F) Left, representative Kv2.1 current trace induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV under the control condition (black), and in the presence of Kv2.2-specific antibody (1:200) in the pipette solution (red) in the same HEK293 cells transfected with Kv2.1. Right, statistics for the IK amplitude using a paired Student's t-test. n.s., not significant. (G) Similar to E, but with the presence of Kv2.1-specific antibody (1:200) in the pipette solution. ***p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. (H) Left, representative current recordings in response to 200-ms depolarization pulses from −80 to +40 mV in the control (top, black) and cortisol-treated (bottom, red) groups. Right, plot of the current-voltage relationship in the control (black) and cortisol-treated groups (red, n = 5 for each data point). The p-values were calculated using a paired Student's t-test. *p < 0.05. (I) Plot of Kv2.2 channel activation curves in the control (n = 5 for each data point; black) and cortisol-treated (n = 5 for each data point; red) groups. (J) Plot of Kv2.2 current inactivation curves in the control (n = 5 for each data point; black) and cortisol-treated (n = 5 for each data point; red) groups. (K) Representative unitary currents of Kv2.2 channels elicited by repeated test pulses from −70 mV to +10 mV under the control condition (black, left) and in the presence of 10 μM cortisol (red, right) in the same HEK293 cell. (L–M) 10 μM cortisol significantly increased the single-channel open probability of Kv2.2 but did not alter the unitary conductance of Kv2.2. The p values were calculated using a paired Student's t-test. *p < 0.05; n.s., not significant.

To verify that the stimulatory effect of cortisol acted on Kv2.2 channels instead of other possible endogenous potassium channels in HEK293 cells, we selectively inhibited the Kv2.2 channels via intracellular application of Kv2.2-specific antibody (1:200) in the pipette solution using a whole-cell configuration. Approximately 1–2 min after break-in, Kv2.2-specific antibody dramatically reduced the IK, and cortisol showed no effect on residual currents (Ctrl: n = 5; Anti-Kv2.2: 22.8 ± 4.5%; n = 5; p = 0.0003; Anti-Kv2.2 + cortisol: 20.3 ± 3.2%; n = 5; p = 0.0003; one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 1E). We also tested the specificity of the Kv2.2 antibody in HEK293 cells overexpressing Kv2.1. The Kv2.2 antibody had no effect on Kv2.1 current (Ctrl: n = 6; Anti-Kv2.2: 96.0 ± 1.9%; n = 6; p = 0.1294; paired Student's t-test; Fig. 1F). In addition, the Kv2.1-specific antibody in the pipette solution did not alter the Kv2.2 currents or the stimulatory effect of cortisol on Kv2.2 currents (Ctrl: n = 5; Anti-Kv2.1: 98.6 ± 2.7%; n = 5; p > 0.9999; Anti-Kv2.1 + cortisol: 128.8 ± 2.6%; n = 5; p = 0.0003; one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 1G).

We further examined whether cortisol increased Kv2.2 currents by altering the steady-state activation or inactivation properties of Kv2.2 currents. We plotted the current-voltage (I-V) curve induced by a 200-ms depolarization pulse from −80 mV to −70, −60, …+40 mV with an interval of 10 s in the presence of 10 μM cortisol in the extracellular solution (Fig. 1H, left). We found that cortisol increased Kv2.2 currents at all depolarization pulses that were more positive than 0 mV (n = 5 for each group; paired Student's t-test; Fig. 1H, right). However, cortisol did not change either the steady-state activation (Ctrl: V1/2 = 6.4 ± 2.7 mV; Cortisol: V1/2 = 8.3 ± 2.5 mV; n = 7; p = 0.6443, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 1I) or inactivation (Ctrl: V1/2 = 12.0 ± 1.2 mV; Cortisol: V1/2 = 9.7 ± 2.5 mV; n = 5; p = 0.4519, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 1J) properties of Kv2.2 currents. To further investigate the mechanism of the cortisol-induced activation of Kv2.2 channels, we examined the Kv2.2 single-channel activity using cell-attached recording. We found that cortisol significantly increased the channel open probability from 33.5 ± 5.5% to 50.9 ± 8.7% (n = 7; p = 0. 0162, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 1K and L) without affecting the single-channel conductance (Fig. 1M).

3.2. Glucocorticoids increase Kv2.2 currents through the membrane-associated glucocorticoid receptors

Non-genomic effects of glucocorticoids can be glucocorticoid receptor-dependent or -independent (Panettieri et al., 2019). Next, we investigated whether cortisol increases Kv2.2 currents via glucocorticoid receptors. We found that 1 μM dexamethasone, the artificial synthetic cortisol analog, could significantly increase the Kv2.2 currents induced by a 200-ms depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV in HEK293 cells (131.5 ± 4.4%; n = 7; p = 0.0019, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 2A). Bath application of RU486 (10 μM), a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist (Lin et al., 2022), completely abolished the cortisol-induced increase in Kv2.2 currents (102.5 ± 3.0%; n = 9; p = 0.2926, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 2B). In addition, RU486 itself had no effect on Kv2.2 currents (n = 7; p = 0.6082, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 2C). These results suggest that cortisol increases the Kv2.2 current via the glucocorticoid receptor-dependent pathway.

Fig. 2.

Glucocorticoids increase Kv2.2 current by binding the membrane-associated glucocorticoid receptor and activating the ERK1/2 signaling pathway in HEK293 cells.

(A) Left, representative Kv2.2 current traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV under the control condition (with 0.1% DMSO, black) and subsequently in the presence of 1 μM dexamethasone (red) in the same HEK293 cell. Right, statistics for the amplitude of Kv2.2 current from Left using a paired Student's t-test (n = 7). **p < 0.01. (B) Left, representative Kv2.2 current traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV in the presence of 10 μM RU486 (black) and subsequently in the presence of an additional 10 μM cortisol (red) in the same HEK293 cell. Right, statistics for the amplitude of Kv2.2 current from Left using a paired Student's t-test (n = 9). n.s., not significant. (C) 10 μM RU486 did not alter Kv2.2 currents (n = 7). n.s., not significant. (D) Similar to A, but with 1 μM dexamethasone-BSA in the extracellular solution (n = 7). **p < 0.01. (E) Left, representative Kv2.2 current traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV under the 10 μM RU486 (black) and subsequently in the presence of 1 μM dexamethasone-BSA (red) in the same HEK293 cell. Right, statistics for the amplitude of Kv2.2 current from Left using a paired Student's t-test (n = 10). n.s., not significant. (F) Left, representative Kv2.2 current traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV under the control condition (black), in the presence of staurosporine (blue), and in the presence of an additional 10 μM cortisol (red) in the same HEK293 cell. Right, statistics for the amplitude of the Kv2.2 current using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (n = 6). n.s., not significant. (G) Left, representative Kv2.2 current traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV in the presence of 10 μM H-89 (black) and subsequently in the presence of an additional 10 μM cortisol (red) in the same HEK293 cell. Right, statistics for the amplitude of Kv2.2 current from Left using a paired Student's t-test (n = 5). *p < 0.05. (H) Similar to F, but with 10 μM BIS in the extracellular solution (n = 5). *p < 0.05. (I) Similar to F and G, but with 10 μM U0126 in the extracellular solution (n = 8). n.s., not significant. (J) 10 μM H-89, Bis, and U0126 did not alter Kv2.2 currents (n = 7, 6, and 6, respectively). n.s., not significant. (K) Left, representative Western blot of the ERK phosphorylation level after 5-min cortisol treatment (10 μM) in the extracellular solution in HEK293 cells. Right, statistics from 5 independent experiments using a paired Student's t-test. *p < 0.05.

The glucocorticoid receptors have been shown to be expressed both on the cell membrane and in the cytoplasm (Barabás et al., 2018), raising the question of which receptors are responsible for the non-genomic effects of cortisol. Previous studies have indicated that the non-genomic effects of glucocorticoids are most likely mediated via the glucocorticoid receptors on the cell membrane (Panettieri et al., 2019). To test this hypothesis, we applied 1 μM BSA-conjugated dexamethasone, a membrane-impermeable agonist of the glucocorticoid receptor (Di et al., 2003), to the extracellular solution and found a similar increase in Kv2.2 currents compared to the dexamethasone-treated group (136.0 ± 4.2% of the control group; n = 7; p = 0.0025, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 2D). Moreover, we applied 10 μM RU486 to the bath solution and found that it blocked the increase in Kv2.2 current induced by dexamethasone-BSA (95.9 ± 2.9% compared with RU486 group, n = 10; p = 0.2333, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 2E), suggesting a dominant role of the membrane-associated glucocorticoid receptor in modulating the glucocorticoid-increased Kv2.2 currents.

3.3. Glucocorticoids increase Kv2.2 currents via the ERK1/2 signaling pathway

Previous studies have reported that cortisol exerts its effects via several signaling pathways downstream of the glucocorticoid receptors, including the PKA (Han et al., 2005), PKC (Han et al., 2002), and ERK signaling pathways (Xiao et al., 2010). First, we used staurosporine, a nonspecific protein kinase inhibitor, to test whether the stimulatory effect of cortisol on Kv2.2 occurs through protein kinase signaling pathways. As shown in Fig. 2F, staurosporine abolished the stimulatory effect of cortisol on Kv2.2 (93.8 ± 5.0% compared with the staurosporine-treated group; n = 6; p = 0.4994, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 2F). To further determine the protein kinase signaling pathway through which cortisol facilitates Kv2.2 currents, we applied H-89 (10 μM, the PKA antagonist) (Ma et al., 2021), Bis (1 μM, the PKC antagonist) (Xue and Wu, 2010), and U0126 (10 μM, the ERK antagonist) (Hou et al., 2022) to the extracellular solution to inhibit the three kinases. We found that neither H-89 nor Bis could suppress the cortisol-induced increase in the Kv2.2 currents (H-89: 126.1 ± 6.0%; n = 5; p = 0.0111, paired Student's t-test; BIS: 122.4 ± 2.2%; n = 5; p = 0.0273, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 2G and H). However, 10 μM U0126 completely abolished the cortisol-facilitated Kv2.2 current (104.5 ± 4.0%; n = 8; p = 0.3366, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 2I), suggesting that cortisol increases the Kv2.2 current via the ERK signaling pathway. Acutely application of H-89, Bis or U0126 had no effect on Kv2.2 currents (Fig. 2J). We further examined whether the ERK kinase was activated by cortisol in Western blot experiments. Five-minute treatment with 10 μM cortisol in the extracellular solution significantly increased the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in HEK293 cells (144.4 ± 13.4%; n = 5; p = 0.030; paired Student's t-test; Fig. 2K). Therefore, we concluded that cortisol increased the Kv2.2 currents via the ERK1/2 signaling pathway.

3.4. Glucocorticoids increase native Kv2.2 currents in cortical pyramidal neurons and calyx-type synapses

After demonstrating the non-genomic effect of glucocorticoids in HEK293 cells that overexpress Kv2.2 channels, we considered the differences between the HEK293 cell line and brain neurons. We investigated the rapid non-genomic effects of cortisol on native Kv2.2 channels in brain slices. We examined the effect of cortisol in mouse cortical layer 2 pyramidal neurons and the rat giant calyx-type synapses located in the brain stem, where Kv2.2 channels have been reported to be preferentially expressed (Bishop et al., 2015). In cortical pyramidal neurons, we elicited the IK using a 200-ms depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV. Bath application of 10 μM cortisol for 5 min significantly increased the rectified outward IK by 28.0 ± 1.2% (Ctrl: 1.8 ± 0.3 nA; Cortisol: 2.3 ± 0.4 nA; n = 5; p = 0.0036, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 3A). Corticosterone had a similar effect on the IK in the pyramidal neurons to that of cortisol (n = 8; p = 0.0009, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 3B). Moreover, in the presence of corticosterone, additional treatment with cortisol did not further increase the IK currents (Fig. 3B), indicating that the effects of cortisone and cortisol on the potassium channel currents are mediated through the same signaling pathway. To determine whether the cortisol-increased IK in the pyramidal neurons was mediated by Kv2.2 channels, we selectively inhibited the Kv2.2 channels via intracellular application of Kv2.2-specific antibody in the pipette solution using a whole-cell configuration (Li et al., 2022). Approximately 1–2 min after break-in, Kv2.2-specific antibody dramatically reduced the IK by 51.6 ± 4.9% (Ctrl: 2.3 ± 0.3 nA; Anti-Kv2.2: 1.2 ± 0.2 nA; n = 5; p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 3C), and additional application of 10 μM cortisol to the extracellular solution for 5 min could no longer increase the IK (88.3 ± 11.8% compared to the IK with Kv2.2 antibody; n = 5; p = 0.4311, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 3C), confirming that Kv2.2 plays a dominant role in mediating the cortisol-induced increase in the potassium current in cortical layer 2 pyramidal neurons (Bishop et al., 2015). To further confirm the involvement of Kv2.2 channels in the cortisol-induced increase of IK, we used lentivirus vectors to deliver shRNA targeted to affect post-translational silencing of the Kv2.2 gene in the pyramidal neurons. First, the knockdown efficiency of the shRNA was tested in HEK293 cells overexpressing Kv2.2 (KD-Kv2.2: 39.2 ± 2.5%; n = 3; p = 0.0017, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 3D, left). The shRNA targeting Kv2.2 channels reduced IK by 62.3% in the pyramidal neurons (Scramble: 2.6 ± 0.3 nA; n = 4; KD-Kv2.2: 1.0 ± 0.3 nA; n = 6; p = 0.0016, unpaired Student's t-test; Fig. 3D, right). The knockdown of Kv2.2 channels mimicked Kv2.2 antibody-induced inhibition of the cortisol-induced increase in Kv2.2 currents (KD-Kv2.2: 1.1 ± 0.2 nA; n = 6; KD-Kv2.2 + cortisol: 1.1 ± 0.2 nA; n = 6; p = 0.7077, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 3E). Similar to our observations in HEK293 cells above, RU486 (10 μM) or U0126 (10 μM) abolished the cortisol-induced increase in IK in the cortical layer 2 pyramidal neurons by inhibiting the glucocorticoid receptor and ERK1/2 signaling pathway, respectively (RU486 + cortisol compared to the IK with RU486: 104.3 ± 2.4%; n = 8; p = 0.1212, paired Student's t-test; U0126 + cortisol compared to the IK with U0126: 96.9 ± 1.6%; n = 8; p = 0.1471, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 3F and G). Western blots experiment further demonstrated that cortisol increased the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 kinase in cortical pyramidal neurons (131.8 ± 3.2%; n = 4; p = 0.0023, unpaired Student's t-test; Fig. 3H), indicating that cortisol increases the native Kv2.2 channel currents via the glucocorticoid receptor/ERK signaling pathway in cortical layer 2 pyramidal neurons.

Fig. 3.

Glucocorticoids increase native Kv2.2 currents by binding the membrane-associated glucocorticoid receptor and activating the ERK1/2 signaling pathway in cortical pyramidal neurons.

(A) Left, representative IK traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV under the control condition (with 0.1% DMSO, black) and subsequently in the presence of 10 μM cortisol (red) in the same cortical pyramidal neuron. Right, statistics for the IK amplitude from Left using a paired Student's t-test (n = 5). **p < 0.01. (B) Left, representative IK traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV under the control condition (black), in the presence of 10 μM corticosterone (blue), and in the presence of an additional 10 μM cortisol (red) in the same cortical pyramidal neuron. Right, IK amplitude using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (n = 8). ***p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. (C) Left, representative IK traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV under the control condition (black), in the presence of Kv2.2-specific antibody (1:200) in the pipette solution (blue), and subsequent in the presence of an additional 10 μM cortisol (red) in the same cortical pyramidal neuron. Right, statistics for the IK amplitude from Left using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. ***p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. (D) Left, effect of shRNA on mRNA expression of Kv2.2 channels in HEK293 cells transduced with shRNA-Kv2.2. Right, shRNA-targeting Kv2.2 channels reduced IK by 62.3% in the cortical pyramidal neurons, unpaired Student's t-test. **p < 0.01. (E) Left, representative IK traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV under the knockdown of Kv2.2 channels (black) and subsequently 10 μM cortisol (red) in the same cortical pyramidal neuron. Right, statistics for the amplitude of IK from Left using a paired Student's t-test (n = 6). n.s., not significant. (F) Left, representative Kv2.2 current traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV in the presence of 10 μM RU486 (black) and subsequently in the presence of an additional 10 μM cortisol (red) in the same cortical pyramidal neuron. Right, statistics for the amplitude of IK from Left using a paired Student's t-test (n = 8). n.s., not significant. (G) Left, representative Kv2.2 current traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV in the presence of 10 μM U0126 in the extracellular solution (black) and subsequently 10 μM cortisol (red) in the same cortical pyramidal neuron. Right, statistics for the amplitude of IK from Left using a paired Student's t-test (n = 8). n.s., not significant. (H) Left, representative Western blot of the ERK phosphorylation level after 5-min cortisol treatment (10 μM) in the extracellular solution in cortical pyramidal neuron. Right, statistics from 5 independent experiments using a paired Student's t-test (n = 5). **p < 0.01.

The calyx of Held synapse contains a giant presynaptic nerve terminal that allows direct presynaptic and postsynaptic recordings to investigate the precise mechanisms of synaptic transmission (Liu et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020). Consistent with our results in cortical pyramidal neurons, 10 μM cortisol in the extracellular solution also dramatically increased the presynaptic IK induced by a 200-ms depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV (Ctrl: 3.0 ± 0.2 nA; cortisol: 3.5 ± 0.2 nA; n = 9; p = 0.0011, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 4A) in the presynaptic nerve terminals of the calyx of Held synapse. Furthermore, corticosterone had a similar stimulatory effect to that of cortisol in the calyces (n = 8; p = 0.0451, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 4B). Kv2.2-specific antibody (1:200 in the pipette solution) reduced the IK by 20% approximately 3 min after break-in (19.0 ± 2.2%; n = 8; p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 4C), and cortisol could no longer increase the IK (98.4 ± 0.8% compared to the IK with Kv2.2 antibody; n = 8; p > 0.9999, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 4C), confirming that the cortisol-induced increase in the presynaptic IK was mediated by the Kv2.2 channels at the calyx of Held synapse. RU486 (10 μM) or U0126 (10 μM) completely abolished the cortisol-increased Kv2.2 current (RU486 + cortisol compared to the IK with RU486: 100.9 ± 1.5%; n = 9; p = 0.4853, paired Student's t-test; U0126 + cortisol compared to the IK with U0126: 99.6 ± 3.5%; n = 8; p = 0.6979, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 4D and E), confirming that it is the same signaling pathway as that in cortical pyramidal neurons.

Fig. 4.

Glucocorticoids increase native Kv2.2 currents by binding the membrane-associated glucocorticoid receptor and activating the ERK1/2 signaling pathway at calyx-type synapses.

(A) Left, representative IK traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV under the control condition (with 0.1% DMSO, black) and subsequently in the presence of 10 μM cortisol (red) at the same calyx-type synapse. Right, statistics for the IK amplitude from Left using paired Student's t-test (n = 9). **p < 0.01. (B) Left, representative IK traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV under the control condition (black), in the presence of 10 μM corticosterone (blue), and in the presence of an additional 10 μM cortisol (red) in the same calyx-type synapse. Right, IK amplitude using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (n = 8). *p < 0.05; n.s., not significant. (C) Left, representative IK traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV under the control condition (black), in the presence of Kv2.2-specific antibody (1:200) in the pipette solution (blue), and subsequent in the presence of an additional 10 μM cortisol (red) at the same calyx-type synapse. Right, statistics for the IK amplitude from Left using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. ***p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. (D) Left, representative Kv2.2 current traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV in the presence of 10 μM RU486 (black) and subsequently in the presence of an additional 10 μM cortisol (red) at the same calyx-type synapse. Right, statistics for the amplitude of IK from Left using a paired Student's t-test (n = 9). n.s., not significant. (E) Left, representative Kv2.2 current traces induced by a depolarization pulse from −80 to +40 mV in the presence of 10 μM U0126 in the extracellular solution (black) and subsequently 10 μM cortisol (red) at the same calyx-type synapse. Right, statistics for the amplitude of IK from Left using paired Student's t-test (n = 8). n.s., not significant.

3.5. Glucocorticoids inhibit neuronal excitability via Kv2.2 channels in cortical pyramidal neurons and calyx-type synapses

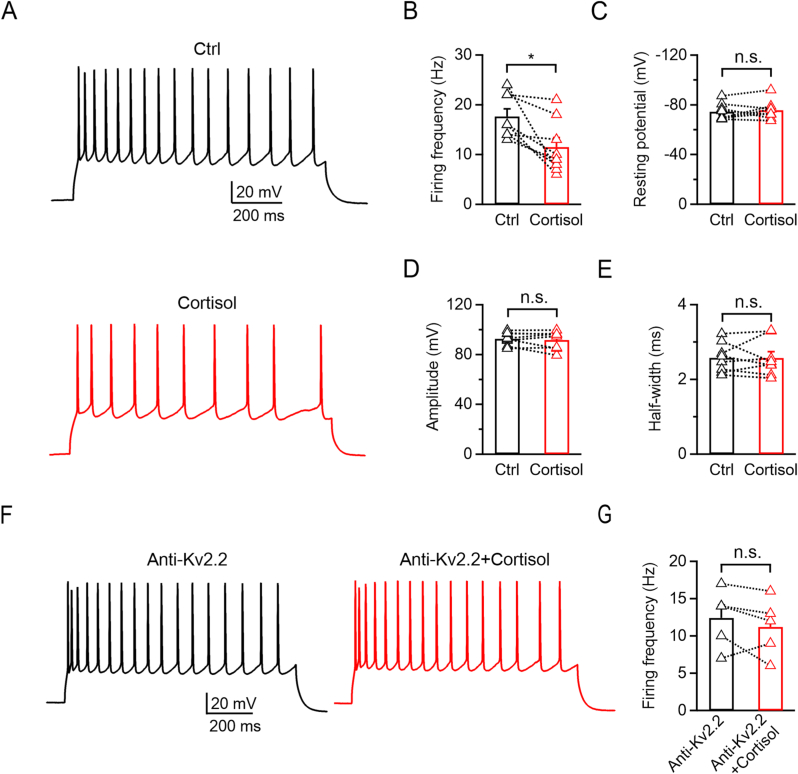

The Kv2 channel family has been shown to play key roles in regulating neuronal excitability by regulating AP repolarization and hyperpolarizing inter-spike membrane potentials during repetitive firing (Johnston et al., 2010). Therefore, we further explored how cortisol modulated the neuronal excitability in cortical pyramidal neurons and calyx-type synapses by examining the AP firing pattern. In cortical pyramidal neurons, repetitive AP firings were elicited by the injection of a 1 s, 200-pA current via a whole-cell configuration. Adding 10 μM cortisol to the extracellular solution significantly reduced the AP frequency by 34.7 ± 8.0% (Ctrl: 17.6 ± 1.5 Hz; Cortisol: 11.5 ± 1.9 Hz; n = 8; p = 0.0134; paired Student's t-test; Fig. 5A and B). Cortisol did not affect the resting membrane potential (Ctrl: −74.6 ± 2.4 mV; Cortisol: −75.7 ± 2.7 mV; n = 8; p = 0.3829; paired Student's t-test; Fig. 5C), AP amplitude (Ctrl: 92.6 ± 1.8 mV; Cortisol: 91.6 ± 2.6 mV; n = 8; p = 0.5276, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 5D), or half-width (Ctrl: 2.6 ± 0.1 ms; Cortisol: 2.6 ± 0.2 ms; n = 8; p = 0.9696, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 5E). These results suggested that cortisol inhibits AP firing but does not affect the characteristics of the AP waveform in cortical neurons. We further applied the Kv2.2 antibody (1:200) via the pipette solution and found that cortisol could not reduce the AP frequency (Kv2.2 antibody: 12.4 ± 1.7 Hz; Kv2.2 antibody + cortisol: 11.2 ± 1.7 Hz; n = 5; p = 0.2835, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 5F and G), indicating that Kv2.2 played a pivotal role in mediating the AP firing.

Fig. 5.

Glucocorticoids inhibit AP frequency via Kv2.2 channels in cortical pyramidal neurons.

(A) Representative AP firings induced by 1 s, 200-pA current injection via a whole-cell configuration under the control condition (top, with 0.1% DMSO, black) and subsequently in the presence of 10 μM cortisol (bottom, red) in the same cortical pyramidal neuron. (B–E) Statistics for the firing frequency, resting potential, amplitude, and half-width from A (n = 8). The p-values were calculated using a paired Student's t-test, *p < 0.05; n.s., not significant. (F) Similar to A, but with Kv2.2-specific antibody (1:200) in the pipette solution. (G) Statistics for the firing frequency from H (n = 5) using a paired Student's t-test. n.s., not significant.

At the calyx-type synapse, we induced single AP at the presynaptic nerve terminal by injecting 1 ms, 100–300 pA current in the current clamp configuration (Fig. 6A). Administration of cortisol (10 μM) to the extracellular solution did not affect the resting membrane potential (Ctrl: −68.2 ± 1.4 mV, Cortisol: −69.4 ± 1.8 mV; n = 9; p = 0.3237, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 6B), and we did not observe significant differences in AP amplitude (Ctrl: 106.3 ± 1.3 mV, Cortisol: 106.8 ± 1.6 mV; n = 9; p = 0.7847, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 6C) or half-width (Ctrl: 0.54 ± 0.03 ms, Cortisol: 0.62 ± 0.06 ms; n = 9; p = 0.2733, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 6D) after bath application of cortisol for 5 min. We also induced repetitive AP firing by injecting a 1s, 300 pA current (Fig. 6E). Cortisol significantly reduced the AP frequency at the presynaptic nerve terminal (Ctrl: 15.0 ± 4.8 Hz; Cortisol: 6.4 ± 2.5 Hz; n = 7; p = 0.0167, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 6F, top), consistent with what we have seen in the cortical pyramidal neurons. We also compared the bursting firing frequency and found that cortisol also significantly reduced the bursting frequency (Ctrl: 4.9 ± 1.4 Hz; Cortisol: 2.0 ± 0.8 Hz; n = 7; p = 0.0437, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 6F, bottom). Intracellular application of Kv2.2 antibody (1:200) via the pipette solution decreased the AP frequency (Ctrl: 13.9 ± 2.4 Hz; Anti-Kv2.2: 10.1 ± 1.8 Hz; n = 8; p = 0.0221, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 6G and H, top), and additional application of 10 μM cortisol to the extracellular solution could not further reduce the frequency (Anti-Kv2.2: 10.1 ± 1.8 Hz; Anti-Kv2.2 + cortisol: 9.1 ± 1.6 Hz; n = 8; p > 0.9999, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 6H, top). Kv2.2 antibody also reduced the bursting firing frequency (Ctrl: 4.5 ± 1.7 Hz; Anti-Kv2.2: 2.3 ± 0.9 Hz; n = 8; p = 0.0029, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 6H, bottom) and abolished the effect of cortisol (Anti-Kv2.2: 2.3 ± 0.9 Hz; Anti-Kv2.2 + cortisol: 2.4 ± 0.9 Hz; n = 8; p > 0.9999, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 6H, bottom), confirming the involvement of the Kv2.2 channels.

Fig. 6.

Glucocorticoids inhibit the AP firing frequency via Kv2.2 channels at calyx-type synapses.

(A) Representative AP waveforms under the control condition (with 0.1% DMSO, black) and subsequently in the presence of 10 μM cortisol (red) at the presynaptic nerve terminal of the calyx-type synapse were overlapped. Single AP was induced by 1 ms, 100–300 pA current injection with 50-pA increments. (B–D) Statistics for the resting membrane potential, amplitude, and half-width from A (n = 9). The p-values were calculated using a paired Student's t-test. n.s., not significant. (E) Representative presynaptic AP firings evoked by 1 s, 300 pA current injection under the control condition (black) and subsequently in the presence of 10 μM (red) cortisol at the calyx-type synapse. (F) Statistics for the AP firing frequency (top) and bursting frequency (bottom) from E using a paired Student's t-test. *p < 0.05. (G) Representative presynaptic AP firings evoked by 1 s, 300 pA current injection under the control condition (black), in the presence of Kv2.2-specific antibody (1:200) in the pipette solution (blue), and in the presence of an additional 10 μM cortisol (red) at the calyx-type synapse. (H) Statistics for the AP firing frequency (top) and bursting frequency (bottom) using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; n.s., not significant. (I) Representative presynaptic AP firings evoked by 1 ms, 300 pA current injection at 10, 50, 100, and 200 Hz for 1 s under the control condition (black) and subsequently in the presence of 10 μM cortisol (red) at the calyx-type synapse. (J) Statistics for the success rate of AP firing from I (n = 5 for each stimulation frequency) using a paired Student's t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (K) Similar to I, but with Kv2.2-specific antibody (1:200) in the pipette solution. (L) Statistics for the success rate of AP firing from K (n = 5 for each stimulation frequency) using a paired Student's t-test.

At calyces, the neuronal firing can be increased to 600 Hz upon stimulation (von Gersdorff and Borst, 2002). Therefore, we induced 1 s AP firing by 1 ms, 300 pA depolarizing current injections at 10, 50, 100, and 200 Hz. We found that the APs at the nerve terminal were 100% successful at 10 Hz, and cortisol could not reduce the successful rate (Fig. 6I, top left). However, at higher stimulation frequencies, cortisol gradually inhibited the AP success rate in a frequency-dependent manner (50 Hz: Ctrl, 69 ± 13%; Cortisol, 66 ± 14%; n = 5; p = 0.3739, paired Student's t-test; 100 Hz: Ctrl, 51 ± 13%; Cortisol, 32 ± 12%; n = 5; p = 0.0025, paired Student's t-test; 200 Hz: Ctrl, 26 ± 5%; Cortisol, 13 ± 6%; n = 5; p = 0.0328, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 6I and J). In addition, Kv2.2 antibody (1:200) in the pipette solution abolished the cortisol-induced inhibition of the AP successful rate at all stimulation frequencies (50 Hz: Ctrl, 70 ± 15%; Cortisol, 62 ± 17%; n = 5; p = 0.4630, paired Student's t-test; 100 Hz: Ctrl, 47 ± 15%; Cortisol, 46 ± 16%; n = 5; p = 0.7151, paired Student's t-test; 200 Hz: Ctrl, 11 ± 3%; Cortisol, 8 ± 2%; n = 5; p = 0.0793, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 6K and L). These results demonstrated that cortisol can inhibit neuronal excitability upon intense stimulation.

3.6. Glucocorticoids inhibit synaptic transmission upon intense stimulation at calyx-type synapses

Presynaptic AP triggers neurotransmitter release and evokes the postsynaptic response. We further investigated whether the cortisol-induced presynaptic inhibition affects the postsynaptic responses at the calyx-type synapse. We elicited two consecutive EPSCs at the principal neuron via a pair of brief stimulations with a bipolar electrode every 10 s (Wu et al., 2020). Bicuculline (10 μM) was added to the extracellular solution to inhibit GABAA-mediated currents (Lujan et al., 2019). PPR was used to evaluate the changes in release probability (Mahapatra and Lou, 2017; Wu et al., 2020). After 5 min baseline recording, cortisol (10 μM) was applied to the extracellular solution for 15 min, and then washed out for another 10 min (Fig. 7A). We found that the EPSC amplitude, PPR, rise time, and decay time were not significantly changed with cortisol treatment, suggesting that cortisol did not affect either the characteristics of the postsynaptic responses or the presynaptic release probability (Fig. 7B–D) (Wu et al., 2020). We also measured the mEPSCs to examine whether cortisol can modulate the sensitivity of the postsynaptic AMPA receptors (Fig. 7E) (Wu et al., 2007). All mEPSCs were recorded at a holding potential of −80 mV with 50 μM APV and 10 μM bicuculline in the extracellular solution to inhibit the NMDA and GABAA-receptors mediated currents (Sun and Wu, 2001; Wu et al., 2007). The mean mEPSC amplitude and frequency in controls were 32.1 ± 1.8 pA and 1.2 ± 0.3 Hz, respectively (2528 events from 7 calyces; Fig. 7F and G). The 10–90% rise time and 20–80% decay time were 0.34 ± 0.02 ms and 1.69 ± 0.08 ms, respectively (n = 7; Fig. 7I and J). Administration of 10 μM cortisol in the extracellular solution did not change the amplitude (32.7 ± 2.0 pA, 2112 events from 7 calyces, p > 0.9999, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 7F) or frequency (1.0 ± 0.2 Hz; p = 0.3467; one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 7G). The 10–90% rise time and 20–80% decay time were also not affected (Cortisol-treated group: 10–90% rise time, 0.32 ± 0.02 ms; 20–80% decay time,1.66 ± 0.07 ms; n = 7; p > 0.9999, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; Fig. 7I and J). The results of the EPSC and mEPSC recordings were consistent with the observation that cortisol did not affect the presynaptic AP firing at low frequency (Fig. 6).

Fig. 7.

Glucocorticoids inhibit synaptic transmission upon intense stimulation at calyx-type synapses.

(A) Top, representative paired EPSC recordings in response to 0.1 Hz fiber stimulation at the midline of the trapezoid body. After obtaining a stable baseline (control with 0.1% DMSO) for 5 min, 10 μM cortisol was applied to the extracellular solution for 15 min and then washed out for another 10 min. Bottom, the corresponding PPR calculated from the paired EPSC amplitudes. (B) Top, EPSC pairs sampled at time points a (control, black), b (cortisol treatment, red), and c (washout, blue) from A were overlapped, showing the EPSC changes in response to cortisol application. Bottom, statistics for EPSC amplitude and PPR from A (n = 7) using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. n.s., not significant. (C–D) Statistics for the rise time and decay time from A (n = 7) using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. n.s., not significant. (E) Sampled mEPSC recordings under the control condition (upper, black), subsequently in the presence of 10 μM cortisol (middle, red), and washout (lower, blue) at the same principal neuron of the calyx-type synapse. (F–G) Statistics for the amplitude and frequency of the mEPSCs from E (n = 7) using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. n.s., not significant. (H) The cumulative probability distribution from E. (I–J) Statistics for the 10–90% rise time and 20–80% decay time (n = 7) using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. n.s., not significant. (K) Top, representative EPSC evoked by 100 Hz fiber stimulation under the control condition (black) and subsequently in the presence of 10 μM cortisol (red) at the same principal neuron of the calyx-type synapse (inset shows the scaled EPSCs in the stable plateau). Bottom, similar to Top, but with 200 Hz fiber stimulation. (L) Top, statistics for the EPSC successful rate at 5, 50, 100, and 200 Hz under the control condition (black) and subsequently in the presence of cortisol (red, n = 6 for each stimulation frequency). Bottom, similar to Top, but for the EPSC40/EPSC1 ratio (n = 6 for each stimulation frequency). The p-values were calculated using a paired Student's t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

We further explored how EPSCs were affected under intense stimulation. We evoked 40 EPSCs at 5, 50, 100, and 200 Hz at the postsynaptic principal neuron via fiber stimulation in the presence of 10 μM cortisol in the extracellular solution. Cortisol induced an increased activity-dependent synaptic depression upon high-frequency stimulation trains. The success rate was dramatically decreased when the stimulation frequency was higher than 100 Hz (100 Hz: Ctrl, 97.1 ± 1.4%; Cortisol, 98.3 ± 1.1%; n = 6; p = 0.0756, paired Student's t-test; 200 Hz: Ctrl, 52.1 ± 5.0%; Cortisol, 33.8 ± 4.4%; n = 6; p = 0.0011, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 7K and L). The EPSC40/EPSC1 ratio was also decreased (100 Hz: Ctrl, 6.3 ± 2.0%; Cortisol, 5.3 ± 2.1%; n = 6; p = 0.1942, paired Student's t-test; 200 Hz: Ctrl, 4.5 ± 1.6%; Cortisol, 1.7 ± 0.6%; n = 6; p = 0.0450, paired Student's t-test; Fig. 7K and L). These results indicated that cortisol strongly enhanced the synaptic depression upon high-frequency stimulation.

4. Discussion

Glucocorticoids have been reported to induce diverse effects via genomic and non-genomic mechanisms in the mammalian brain (Roy and Rai, 2009; Billing et al., 2012; Panettieri et al., 2019). In the present study, we, for the first time, reported that glucocorticoids rapidly increase the Kv2.2 channel currents in neurons through the glucocorticoid receptors on the cell membrane. We further investigated the underlying signaling pathway and found that phosphorylation of the ERK1/2 pathway, but not the PKA or PKC pathways, was involved in the rapid non-genomic modulation. Our findings may provide a new universal mechanism for glucocorticoid-induced non-genomic effects in the central nervous system.

The glucocorticoid-modulated effect on ion channels via classical genomic pathways, such as increasing cardiac sodium channel expression in the fetal ovine heart (Fahmi et al., 2004) and epithelial sodium channel expression in fetal and adult guinea pig lungs (Norlin et al., 1999; Ye et al., 2004), typically takes more than a few hours. A recent study also reported that corticosterone increases acid-sensing ion channel expression in rat hippocampal neurons (Ye et al., 2018). However, there are few reports on glucocorticoid's rapid effect (within minutes) on ion channels. A previous study reported that cortisol rapidly inhibits Kv1.5 current in Xenopus oocytes (Yu et al., 2015). Furthermore, the downstream signaling pathway of the glucocorticoid-induced rapid effect on ion channels remains elusive. Ffrench-Mullen reported that cortisol rapidly inhibits L-type calcium channels in hippocampal pyramidal neurons via the PKC signaling pathway (ffrench-Mullen, 1995). Previous studies have suggested that the specific kinase pathways involved in mediating the rapid effects of glucocorticoids can vary depending on the cellular context (Panettieri et al., 2019). For example, in the hippocampus, glucocorticoids have been found to enhance CA1 pyramidal excitability through activation of ERK1/2 kinase (Olijslagers et al., 2008), whereas in the hypothalamus, they have been shown to inhibit glutamatergic synaptic activity of PVN parvocellular neurons through activation of the PKC pathway (Di et al., 2003). In human bronchial epithelial cells, dexamethasone has been shown to decrease intracellular Ca2+ by activating PKA (Urbach et al., 2006), whereas in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells, dexamethasone has been reported to increase intracellular Ca2+ by deactivating ERK1/2 kinase (Abdoul-Azize et al., 2017). In the present study, we demonstrated that the rapid effect of glucocorticoids on Kv2.2 channels is associated with the activation of ERK instead of PKC, suggesting a variety of downstream glucocorticoid signaling pathways.

The membrane-associated glucocorticoid receptor is derived from the same gene as the classical cytosolic glucocorticoid receptor and has been reported to be widely expressed in various cell types (Strehl et al., 2011; Vernocchi et al., 2013). Glucocorticoids rapidly regulate BK and Kv1.3 channels via unknown membrane receptors or direct interaction with the channel (Zaki and Barrett-Jolley, 2002; Lovell et al., 2004). Our study provides direct evidence that glucocorticoids increase the Kv2.2 current through membrane-associated glucocorticoid receptors with bath application of BSA-dexamethasone and RU486, the membrane-impermeable agonist and antagonist of the glucocorticoid receptors, respectively. After binding to the glucocorticoid receptor, glucocorticoids could further modulate the activities of various kinases, including PKA, PKC, and ERK (ffrench-Mullen, 1995; Xiao et al., 2010; Abdoul-Azize et al., 2017). Previous studies have shown that dexamethasone rapidly (within 5 min) decreases the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in human leukemia cell lines Nalm-6 and Reh (Abdoul-Azize et al., 2017) and that BSA-conjugated corticosterone rapidly (within 15 min) inhibits the NMDA-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in cultured hippocampal neurons (Xiao et al., 2010). However, Qiu et al. reported that corticosterone and BSA-conjugated corticosterone rapidly (within 15 min) activate ERK1/2 in PC12 cells (Qiu et al., 2001). Our results also confirm that cortisol rapidly increases ERK1/2 activities in HEK293 cells and cortical neurons. These results indicate that the rapid effect of glucocorticoids on ERK1/2 could be diverse among different cell types. However, the underlying mechanisms that activate ERK1/2 through membrane-associated glucocorticoid receptors need further investigation.

The Kv2 family of voltage-gated potassium channels contains Kv2.1 and Kv2.2. The Kv2.1 channel has been reported to be widely expressed in the brain (Bishop et al., 2015). However, previous studies have shown that the Kv2.2 channels were preferentially expressed in layer 2 pyramidal neurons, the basal forebrain, and the MNTB neurons (Bishop et al., 2015). Kv2 channels are high voltage-activated (HVA) channels with slow activation kinetics and, therefore, contribute little to the resting membrane potential and single AP properties (Irie, 2021). Consistent with this, we found that cortisol did not change the resting membrane potentials and single AP properties in layer 2 pyramidal neurons and calyx-type synapses in the MNTB (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). The effect of Kv2 on neuronal activity can be excitatory or inhibitory. Kv2 channels have been shown to facilitate repetitive AP firing by promoting recovery of voltage-gated sodium channels from inactivation (Johnston et al., 2008). Inhibition of Kv2 channels could reduce the repetitive firing in MNTB neurons (Johnston et al., 2008; Tong et al., 2013) while increasing the fidelity of repetitive firing in dorsal root ganglia neurons (Tsantoulas et al., 2014). In previous studies, dexamethasone rapidly increased basal nitric oxide production in human endothelial cells (Hafezi-Moghadam et al., 2002) and enhanced ATP-induced nitric oxide production in spiral ganglion neurons (Yukawa et al., 2005). Steinert et al. reported that the potentiation of Kv2 currents by nitric oxide reduces the excitability of MNTB and hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons (Steinert et al., 2011), indicating a potential role of nitric oxide in the rapid effect of glucocorticoids on neuronal Kv2.2. Interestingly, in the present study, we found that either inhibition of Kv2.2 with antibodies or activation of Kv2.2 by cortisol reduced the firing rate in the pyramidal cortical neurons and presynaptic nerve terminals at the calyx of Held synapses (Fig. 6E–H), suggesting that Kv2.2 plays a key role in fine-tuning the repetitive neuronal firing upon stimulation. Moreover, we observed that cortisol could strongly enhance synaptic depression upon high-frequency stimulation. At calyces, the presynaptic AP firing rate can be 50 Hz in the resting condition and increase to more than 600 Hz upon stimulation (von Gersdorff and Borst, 2002). The enhanced inhibition during high-frequency stimulation may provide a certain level of protection for prompt and accurate synaptic transmission.

Although the functions of rapid glucocorticoid actions in the brain are not fully understood, one of their main functions is fast feedback regulation of the HPA axis (Kim and Iremonger, 2019). Glucocorticoids directly suppress HPA activity by rapidly suppressing excitation of the corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN), and can also exert positive or negative regulation of the HPA axis through rapid action on the hippocampus or amygdala (Furay et al., 2008; Tasker and Herman, 2011). Previous studies suggested that glucocorticoid receptors in the prefrontal cortex were involved in the negative feedback regulation of stress-induced HPA activation (Mizoguchi et al., 2003; Furay et al., 2008; Hill et al., 2011; McKlveen et al., 2013). The projection of the prefrontal cortex to PVN neuroendocrine cells is through local interneurons, majority of which are GABAergic. Therefore, the inhibitory glucocorticoid action in cortical neurons may be expected to produce fast activation of the HPA axis (Herman et al., 2005). However, studies have also shown the presence of local glutamate excitatory synaptic inputs to PVN neurons (Boudaba et al., 1997). In addition, frontal cortex stimulation has been shown to stimulate corticosterone secretion in rats (Feldman and Conforti, 1985), and local application of glucocorticoids in the medial frontal cortex inhibits stress-induced HPA activation (Diorio et al., 1993), suggesting that the rapid inhibitory effect of glucocorticoids on the actions of prefrontal cortical neurons may provide fast negative feedback regulation of stress-induced HPA activation.

Under non-stress conditions, glucocorticoids are secreted in pulsatile patterns following circadian rhythms, with concentration ranging from tens to hundreds of nanomolars in both rats and mice. However, under stress conditions, peak glucocorticoid levels can reach micromolar levels (Magarinos and McEwen, 1995; Cerqueira et al., 2005; Van der Mierden et al., 2021). Our study revealed that 100 nM of cortisol caused a slight increase in Kv2.2 currents in cultured HEK293 cells, and 1 μM of cortisol significantly increased the Kv2.2 currents by approximately 25%, with the effect peaking at 10 μM. A previous study indicates that the drug concentration at the cell surface is about 3.4 times lower than the perfusion concentration in brain slices (He et al., 2010). Thus, we used 10 μM cortisol throughout our study, reflecting a physiological dose range.

A previous study suggested that glucocorticoids could reverse the cochlear acoustic hypersensitivity induced by adrenalectomy and protect from acoustic trauma (Siaud et al., 2006). In addition, Kv2.2 activity in the ventral nucleus of the trapezoid body and MNTB of the central auditory brainstem has been implicated in noise-induced hearing loss (Tong et al., 2013). These results indicate that the inhibitory action of glucocorticoids on Kv2.2 plays a role in glucocorticoid-induced regulation of hearing.

In summary, our results demonstrate that glucocorticoids could rapidly facilitate Kv2.2 currents via the membrane-associated glucocorticoid receptors and activation of downstream ERK1/2 signaling pathways, leading to the modulation of neuronal excitability in the pyramidal cortical neurons and calyx of Held synapses. Our study provides the first evidence that glucocorticoids regulate neural activity via a rapid non-genomic effect on Kv2.2 channels.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yuqi Wang: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Yuchen Zhang: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Jiawei Hu: Investigation. Chengfang Pan: Investigation. Yiming Gao: Investigation. Qingzhuo Liu: Methodology. Wendong Xu: Conceptualization. Lei Xue: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Changlong Hu: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by the National Key Research & Development Program of China (2022YFC3602700 & 2022YFC3602702), the Science and Technology Innovation 2030 - Brain Science and Brain-Inspired Intelligence Project (2021ZD0201301), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32170688, 31971159, 31771282), the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (23ZR1425900), the Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (2019-01-07-00-07-E00041), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (No. 2018SHZDZX01), and ZJLab.

Handling editor: Rita Valentino

Contributor Information

Lei Xue, Email: lxue@fudan.edu.cn.

Changlong Hu, Email: clhu@fudan.edu.cn.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abdoul-Azize S., Dubus I., Vannier J.-P. Improvement of dexamethasone sensitivity by chelation of intracellular Ca2+ in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells through the prosurvival kinase ERK1/2 deactivation. Oncotarget. 2017;8:27339–27352. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabás K., Godó S., Lengyel F., Ernszt D., Pál J., Ábrahám I.M. Rapid non-classical effects of steroids on the membrane receptor dynamics and downstream signaling in neurons. Horm. Behav. 2018;104:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydyuk M., Xu J., Wu L.-G. The calyx of Held in the auditory system: structure, function, and development. Hear. Res. 2016;338:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billing A.M., Revets D., Hoffmann C., Turner J.D., Vernocchi S., Muller C.P. Proteomic profiling of rapid non-genomic and concomitant genomic effects of acute restraint stress on rat thymocytes. J. Proteonomics. 2012;75:2064–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop H.I., Guan D., Bocksteins E., Parajuli L.K., Murray K.D., Cobb M.M., Misonou H., Zito K., Foehring R.C., Trimmer J.S. Distinct cell- and layer-specific expression patterns and independent regulation of Kv2 channel subtypes in cortical pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:14922–14942. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1897-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudaba C., Schrader L.A., Tasker J.G. Physiological evidence for local excitatory synaptic circuits in the rat hypothalamus. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;77:3396–3400. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.6.3396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle N.B., Lawton C., Arkbåge K., West S.G., Thorell L., Hofman D., Weeks A., Myrissa K., Croden F., Dye L. Stress responses to repeated exposure to a combined physical and social evaluative laboratory stressor in young healthy males. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;63:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira J.J., Pego J.M., Taipa R., Bessa J.M., Almeida O.F., Sousa N. Morphological correlates of corticosteroid-induced changes in prefrontal cortex-dependent behaviors. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:7792–7800. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1598-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di S., Malcher-Lopes R., Halmos K.C., Tasker J.G. Nongenomic glucocorticoid inhibition via endocannabinoid release in the hypothalamus: a fast feedback mechanism. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:4850–4857. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-04850.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diorio D., Viau V., Meaney M.J. The role of the medial prefrontal cortex (cingulate gyrus) in the regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:3839–3847. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-09-03839.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez G., Henkous N., Prevot T., David V., Guillou J.-L., Belzung C., Mons N., Béracochéa D. Sustained corticosterone rise in the prefrontal cortex is a key factor for chronic stress-induced working memory deficits in mice. Neurobiol. Stress. 2019;10 doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahmi A.I., Forhead A.J., Fowden A.L., Vandenberg J.I. Cortisol influences the ontogeny of both alpha- and beta-subunits of the cardiac sodium channel in fetal sheep. J. Endocrinol. 2004;180:449–455. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1800449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S., Conforti N. Modifications of adrenocortical responses following frontal cortex simulation in rats with hypothalamic deafferentations and medial forebrain bundle lesions. Neuroscience. 1985;15:1045–1047. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ffrench-Mullen J.M. Cortisol inhibition of calcium currents in Guinea pig hippocampal CA1 neurons via G-protein-coupled activation of protein kinase C. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:903–911. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00903.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furay A.R., Bruestle A.E., Herman J.P. The role of the forebrain glucocorticoid receptor in acute and chronic stress. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5482–5490. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J.D., Kogan J.F., Marrocco J., McEwen B.S. Genomic and epigenomic mechanisms of glucocorticoids in the brain. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017;13:661–673. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan D., Armstrong W.E., Foehring R.C. Kv2 channels regulate firing rate in pyramidal neurons from rat sensorimotor cortex. J. Physiol. 2013;591:4807–4825. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.257253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman G.A., Chandy K.G., Grissmer S., Lazdunski M., McKinnon D., Pardo L.A., Robertson G.A., Rudy B., Sanguinetti M.C., Stuhmer W., Wang X. International Union of Pharmacology. LIII. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of voltage-gated potassium channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005;57:473–508. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafezi-Moghadam A., Simoncini T., Yang Z., Limbourg F.P., Plumier J.C., Rebsamen M.C., Hsieh C.M., Chui D.S., Thomas K.L., Prorock A.J., Laubach V.E., Moskowitz M.A., French B.A., Ley K., Liao J.K. Acute cardiovascular protective effects of corticosteroids are mediated by non-transcriptional activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nat. Med. 2002;8:473–479. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J.Z., Lin W., Chen Y.Z. Inhibition of ATP-induced calcium influx in HT4 cells by glucocorticoids: involvement of protein kinase A. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2005;26:199–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J.Z., Lin W., Lou S.J., Qiu J., Chen Y.Z. A rapid, nongenomic action of glucocorticoids in rat B103 neuroblastoma cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1591:21–27. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris C., Weiss G.L., Di S., Tasker J.G. Cell signaling dependence of rapid glucocorticoid-induced endocannabinoid synthesis in hypothalamic neuroendocrine cells. Neurobiol. Stress. 2019;10 doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman J.P., Ostrander M.M., Mueller N.K., Figueiredo H. Limbic system mechanisms of stress regulation: hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;29:1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YL, Zhan XQ, Yang G, Sun J, Mei YA. Amoxapine inhibits the delayed rectifier outward K+ current in mouse cortical neurons via cAMP/protein kinase A pathways. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010;332:437–445. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.159160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman J.P., McKlveen J.M., Ghosal S., Kopp B., Wulsin A., Makinson R., Scheimann J., Myers B. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical stress response. Compr. Physiol. 2016;6:603–621. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c150015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermanstyne T.O., Kihira Y., Misono K., Deitchler A., Yanagawa Y., Misonou H. Immunolocalization of the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv2.2 in GABAergic neurons in the basal forebrain of rats and mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010;518:4298–4310. doi: 10.1002/cne.22457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill M.N., McLaughlin R.J., Pan B., Fitzgerald M.L., Roberts C.J., Lee T.T., Karatsoreos I.N., Mackie K., Viau V., Pickel V.M., McEwen B.S., Liu Q.S., Gorzalka B.B., Hillard C.J. Recruitment of prefrontal cortical endocannabinoid signaling by glucocorticoids contributes to termination of the stress response. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:10506–10515. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0496-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y., Zhou B., Ni M., Wang M., Ding L., Li Y., Liu Y., Zhang W., Li G., Wang J., Xu L. Nonwoven-based gelatin/polycaprolactone membrane loaded with ERK inhibitor U0126 for treatment of tendon defects. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022;13:5. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02679-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde G.N., Seale A.P., Grau E.G., Borski R.J. Cortisol rapidly suppresses intracellular calcium and voltage-gated calcium channel activity in prolactin cells of the tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;286:E626–E633. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00088.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie T. Essential role of somatic Kv2 channels in high-frequency firing in cartwheel cells of the dorsal cochlear nucleus. eNeuro. 2021;8 doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0515-20.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J., Forsythe I.D., Kopp-Scheinpflug C. Going native: voltage-gated potassium channels controlling neuronal excitability. J. Physiol. 2010;588:3187–3200. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J., Griffin S.J., Baker C., Skrzypiec A., Chernova T., Forsythe I.D. Initial segment Kv2.2 channels mediate a slow delayed rectifier and maintain high frequency action potential firing in medial nucleus of the trapezoid body neurons. J. Physiol. 2008;586:3493–3509. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.153734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadmiel M., Cidlowski J.A. Glucocorticoid receptor signaling in health and disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2013;34:518–530. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalafatakis K., Russell G.M., Lightman S.L. Mechanisms in endocrinology: does circadian and ultradian glucocorticoid exposure affect the brain? Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019;180:R73–R89. doi: 10.1530/EJE-18-0853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalafatakis K., Russell G.M., Harmer C.J., Munafo M.R., Marchant N., Wilson A., Brooks J.C., Durant C., Thakrar J., Murphy P., Thai N.J., Lightman S.L. Ultradian rhythmicity of plasma cortisol is necessary for normal emotional and cognitive responses in man. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115:E4091–E4100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1714239115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.S., Iremonger K.J. Temporally tuned corticosteroid feedback regulation of the stress axis. Trends Endocrinol. Metabol. 2019;30:783–792. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon C., Breuer L., Jones L., An J., Akan A., Ali E.A.M., Busch F., Fislage M., Ghosh B., Hellrigel-Holderbaum M., Kazezian V., Koppold A., Restrepo C.A.M., Riedel N., Scherschinski L., Gonzalez F.R.U., Weissgerber T.L. Blind spots on western blots: assessment of common problems in western blot figures and methods reporting with recommendations to improve them. PLoS Biol. 2022;20 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]