Abstract

Pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinoline derivatives were synthesized from 2-aryl-pyrrolidines and alkynes via an oxidative dehydrogenation/cyclization coupling/dehydrogenative aromatization domino process. This reaction was promoted by a four-component catalytic system which included [RuCl2(p-cymene)]2, CuCl, copper acetate monohydrate and TEMPO (2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy) under aerobic conditions.

Pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinoline derivatives were synthesized from 2-aryl-pyrrolidines and alkynes via an oxidative dehydrogenation/cyclization coupling/dehydrogenative aromatization domino process.

In recent decades, domino reactions have received widespread attention and have been applied in the construction of complex organic molecules, such as materials, drugs, and other molecules.1 The advantages of domino reactions include the ability to construct complex molecules from easily available raw materials without the need to separate intermediates, which saves time and cost greatly. Recently, a large number of review articles on domino reactions have been published.2 However, developing more efficient and green domino reactions remains one of the challenges currently faced by organic chemists.

Pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinoline is a skeleton of diverse natural alkaloids whose biological activities were discovered by Mikhailovskii and Shklyaev in 1997.3 These biological activities include antitumor, antiviral, anticancer, anti-HIV, antibacterial, antidepressant etc.3,4 Furthermore, their excellent optoelectronic performance has also attracted the attention of material scientists in recent years (Fig. 1).5

Fig. 1. Natural alkaloids, drugs and materials with pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinoline skeleton.

Therefore, the development of new synthetic methods for pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinoline is still a hot topic in organic chemistry.6 In most cases, 2-aryl-indoles were used as the starting materials to synthesize pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinolines. However, 2-aryl-pyrroles were rarely reported as a starting material due to lack of availability.7 As we known, pyrroles could be synthesized from pyrrolines through oxidative dehydrogenative aromatization reaction.8 Therefore, the development of a domino reaction which using the easily available 2-aryl-pyrrolidines9 as starting materials instead of 2-aryl-pyrroles to synthesize pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinolines would be very attractive.

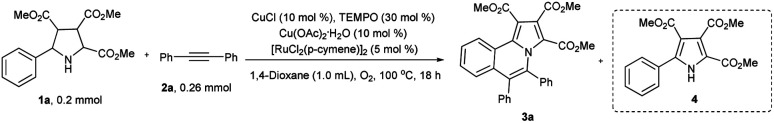

Herein, a domino reaction for the synthesis of pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinolines from 2-aryl-pyrrolidines and alkynes under aerobic oxidation conditions was reported (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. The difference of this work with previous work.

In order to optimize the reaction conditions, we chose 5-phenylpyrrolidine-2,3,4-tricarboxylate (1a) and diphenylacetylene (2a) as the starting materials. The best isolated yield (86%) was achieved under the standard reaction conditions: 1a (0.20 mmol), 2a (0.26 mmol), CuCl (10 mol%), TEMPO (30 mol%), copper acetate monohydrate (10 mol%), [RuCl2(p-cymene)]2 (5 mol%) and 1,4-dioxane (1.0 mL) as the solvent under O2 atmosphere (balloon) at 100 °C for 18 h (Table 1, entry 8). Using other solvent instead of 1,4-dioxane significantly reduce the reaction yields (entry 1, see details in ESI†). Using 20% copper acetate monohydrate as the catalyst without any CuCl added reduce the yield of 3a to 74% (entry 2). Surprisingly, when using 20% CuCl as the catalyst and without any copper acetate monohydrate added, 4 was isolated in 54% yield and no any 3a was formed (entry 3). Also no 3a was formed and 4 was isolated in 90% yield when no any [RuCl2(p-cymene)]2 was added (entry 4). 3a and 4 were isolated in 8% yield and 33% yield without TEMPO (entry 5). Reducing the amount of TEMPO from 30% to 20% and prolonging the reaction time to 36 h would greatly reduce the yield of 3a to 24% (entry 6). 3a and 4 were isolated in 22% and 24% yields respectively when the reaction was running under air instead of oxygen gas (entry 7).

Evaluation of reaction conditions.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Entry | Variation from the standard condition | Yielda (%) |

| 1 | Other solvent instead of 1,4-dioxane | 59–68 |

| 2 | With 20 mol% Cu(OAc)2·H2O without CuCl | 74 |

| 3 | With 20 mol% CuCl without Cu(OAc)2·H2O | (54b) |

| 4 | Without [RuCl2(p-cymene)]2 | (90b) |

| 5 | Without TEMPO | 8 + (33b) |

| 6 | With 20 mol% TEMPO | 24c |

| 7 | Replace O2 with air | 22 + (24b) |

| 8 | No | 86 |

Isolated yield of 3a.

Isolated yield of 4.

36 h.

With the optimized conditions in hand, we firstly studied the scope of pyrrolidines (Scheme 2). When pyrrolidines substituted with electron-withdrawing groups on the phenyl ring were used as the starting materials, the corresponding products (3b–3h) were isolated in moderate to excellent yields (57–90%). Only a single isomer 3c was isolated in 58% yield due to steric effect when there was substituent in the meta position of the phenyl ring. However, when electron donating groups were bearing in the phenyl ring of pyrrolidines, the corresponding products were isolated in extremely low yields under the optimized conditions. Further optimization of the reaction conditions revealed that using TEMPO+BF4− (30%) as the catalyst to replace the CuCl and TEMPO and increasing the amount of copper acetate monohydrate to 20 mol%, 3i was isolated in 60% yield under O2 atmosphere and 3j was isolated in 55% yield under air. Only one isomer 3k was isolated in excellent yield (89%) when 2-naphthyl was bearing at the pyrrolidine. 3l and 3m also were isolated in 66% and 46% yields under standard reaction conditions respectively.

Scheme 2. The substrate scopes of pyrrolidines.

We next explored the substrate scopes of alkynes (Scheme 3). Diphenylacetylene derivatives with electron withdrawing or electron donating groups on the phenyl group could produce designed products (5b–5d) smoothly under standard reaction conditions. 4-Octyne (2e) also works well and the corresponding product 5e is isolated in 38% yield. When the amount of 2e is increased from 1.3 equivalent to 2.0 equivalent, the isolated yield of 5e also increased to 65%. Asymmetric alkynes show moderate region-selectivity (around 55% vs. 15%). The more electron deficient side of asymmetric alkyne tends to react with the nitrogen of pyrrolidine (5gvs.5g′ and 5hvs.5h′). The structure of 5g10 and 5h11 were confirmed by X-ray.

Scheme 3. The scope and region-selectivity of alkyne.

To reveal the reaction mechanism, a series of control experiments were conducted. When the alkyne was absence, pyrrolidines 1a was reacted under the standard reaction conditions and yield the corresponding pyrrole 4 in 71% yield (Scheme 4b). Which was similar to the yield (75%) in the absence of copper acetate monohydrate and [RuCl2(p-cymene)]2 (Scheme 4a). To our surprise, when pyrrole 4 reacted with diphenylacetylene (2a) under standard reaction conditions, 3a was only isolated in 18% yield and 60% of 4 was remain untouched (Scheme 4d). The yield of 3a even lower (12%) in the absence of CuCl and TEMPO (Scheme 4c).

Scheme 4. The results of control experiments (a)–(d).

Based on the above results and our previous results, the mechanism of this domino reaction was proposed (Scheme 5). Under the catalytic system of Cu(i)/TEMPO/O2, pyrrolidine 1a was oxidized to the intermediate 6via oxidative dehydrogenation firstly.12 Then 6 could transformed to the final product pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinoline 3a through two pathways. The major pathway is 6 reacted with alkyne 2a to produce intermediate 7 which was catalyzed by Ru and Cu(ii). Then 7 was transformed to 3a through oxidative dehydrogenative aromatization which was catalyzed by Cu(i) and TEMPO with O2 as the terminal oxidant (path A).13 The minor pathway is that pyrrole 4 was formed firstly catalyzed by Cu(i) and TEMPO under oxygen gas. Then 4 reacted with alkyne 2a to form the final product 3avia Ru and Cu(ii) catalyzed aerobic oxidative coupling reaction.7

Scheme 5. Plausible mechanism.

In order to demonstrate the practicality of the reaction, we successfully increased the reaction scale to gram-scale (Scheme 6). Under the standard reaction conditions, 1.15 grams of 3a was isolated in reasonable yield (78%) which was slightly lower than the yield of small scale reaction.

Scheme 6. The result of gram scale reaction.

In summary, we have reported on the first of a domino reaction for the synthesis of pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinolines from 2-aryl-pyrrolidines and alkynes. This process was promoted by a four-component catalytic system which included [RuCl2(p-cymene)]2, CuCl, copper acetate monohydrate and TEMPO. Control experiments show all four catalysts were important for this reaction and pyrrole was not the key intermediate. Using oxygen gas as a solo oxidant made this transformation green. In short, this method of synthesizing pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinolines is green, simple, and practical, which may provide assistance for the application of such compounds in fields of biomedicine and materials.

Author contributions

Z. Luo and H. Hu conceived the project and performed the investigation on the scope. Z. Luo and Z. Yang optimized the reaction and prepared the experimental parts and first draft of the manuscript. H. Hu supervised the project, H. Hu, C. Wang and Y. Wang edited the manuscript and proofread the experimental part.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Key Projects of China National Key Research and Development Plan (2021YFE0107000) and the National Natural Science Foundation in China (Grant No. 52074339). Professor Zaichao Zhang (HYTC, Huaian, P. R. China) is acknowledged for the X-ray analysis.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. CCDC 2299581 and 2299583. For ESI and crystallographic data in CIF or other electronic format see DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d3ra07653a

Notes and references

- (a) Domino Reactions: Concepts for Efficient Organic Synthesis, ed. L. F. Tietze, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, 2014 [Google Scholar]; (b) Tietze L. F., Brasche G. and Gericke K. M., Domino Reactions in Organic Synthesis, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- For recent reviews: ; (a) Pellissier H. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2023;365:620. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pounder A. Neufeld E. Myler P. Tam W. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2023;19:487. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.19.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Doraghi F. Mohaghegh F. Qareaghaj O. H. Larijani B. Mahdavi M. RSC Adv. 2023;13:13947. doi: 10.1039/d3ra01778h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhailovskii A. G. Shklyaev V. S. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1997;33:243. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Zhang Q. Tu G. Zhao Y. Cheng T. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:6795. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang R. Yang X. Ma C. Cai S. Li J. Shoyama Y. Heterocycles. 2004;63:1443. [Google Scholar]; (c) Su B. Cai C. Deng M. Liang D. Wang L. Wang Q. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:2881. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.04.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ballot C. Kluza J. Martoriati A. Nyman U. Formstecher P. Joseph B. Bailly C. Marchetti P. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2009;8:3307. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Reddy M. V. R. Rao M. R. Rhodes D. Hansen M. S. T. Rubins K. Bushman F. D. Venkateswarlu Y. Faulkner D. J. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:1901. doi: 10.1021/jm9806650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Muthusaravanan S. Perumal S. Yogeeswari P. Sriram D. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:6439. [Google Scholar]; (g) Maryanoff B. E. Vaught J. L. Shank R. P. McComsey D. F. Costanzo M. J. Nortey S. O. J. Med. Chem. 1990;33:2793. doi: 10.1021/jm00172a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Baik C. Kim D. Kang M. Song K. Kang S. O. Ko J. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:5302. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sun K. Zhang Y. Chen X. Su H. Peng Q. Yu B. Qu L. Li K. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020;3:505. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.9b00946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ahmed E. Briseno A. L. Xia Y. Jenekhe S. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:1118. doi: 10.1021/ja077444g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhu L. Kim E.-G. Yi Y. Ahmed E. Jenekhe S. A. Coropceanu V. Brédas J.-L. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2010;114:20401. [Google Scholar]; (e) Choi H. H. Najafov H. Kharlamov N. Kuznetsov D. V. Didenko S. I. Cho K. Briseno A. L. Podzorov V. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:34153. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b11134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Kumarab S. Singh A. K. Chem. Commun. 2022;58:11268. doi: 10.1039/d2cc03713k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Michikita R. Usuki Y. Satoh T. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2022:e202200550. [Google Scholar]; (c) Das D. Das A. R. J. Org. Chem. 2022;87:11443. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.2c00958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Heckershoff R. May G. Däumer J. Eberle L. Krämer P. Rominger F. Rudolph M. Mulks F. F. Hashmi A. S. K. Chem. – Eur. J. 2022;28:e202201816. doi: 10.1002/chem.202201816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kumarab S. Singh A. K. Chem. Commun. 2022;58:11268. doi: 10.1039/d2cc03713k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Thavaselvan S. Parthasarathy K. Org. Lett. 2020;22:3810. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Liu Y. Yang Z. Chauvin R. Fu W. Yao Z. Wang L. Cui X. Org. Lett. 2020;22:5140. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Obata A. Sasagawa A. Yamazaki K. Ano Y. Chatani N. Chem. Sci. 2019;10:3242. doi: 10.1039/c8sc05063e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Morimoto K. Hirano K. Satoh T. Miura M. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2068. doi: 10.1021/ol100560k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Ackermann L. Wang L. Lygin A. V. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:177. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tang X. Huang L. Qi C. Wu W. Jiang H. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:9597. doi: 10.1039/c3cc44896g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Arrieta A. Otaegui D. Zubia A. Cossío F. P. Díaz-Ortiz A. de la Hoz A. Herrero M. A. Prieto P. Foces-Foces C. Pizarro J. L. Arriortua M. I. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:4313. doi: 10.1021/jo062672z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Das T. Saha P. Singh V. K. Org. Lett. 2015;17:5088. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu H. Tao H. Cong H. Wang C. J. Org. Chem. 2016;81:3752. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b00396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Liu H. Liu K. Xue Z. He Z. Wang C. Org. Lett. 2015;17:5440. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Murthy S. N. Nageswar Y. V. D. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:4481. [Google Scholar]; (f) Fejes I. Toke L. Blasko G. Nyerges M. Pak C. S. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:8545. [Google Scholar]; (g) Oussaid B. Garrigues B. Soufiaoui M. Can. J. Chem. 1994;72:2483. [Google Scholar]; (h) Baumann M. Baxendale I. R. Kirschning A. Ley S. V. Wegner J. Heterocycles. 2011;82:1297. [Google Scholar]; (i) Liu Y. Hu H. Wang X. Zhi S. Kan Y. Wang C. J. Org. Chem. 2017;82:4194. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.7b00180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Luo Z. Liu Y. Wang C. Fang D. Zhou J. Hu H. Green Chem. 2019;21:4609. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Cayuelas A. Larranaga O. Najera C. Sansano J. M. de Cozar A. Cossio F. P. Tetrahedron. 2016;72:6043. [Google Scholar]; (b) Arpa E. M. Gonzalez-Esguevillas M. Pascual-Escudero A. Adrio J. Carretero J. C. J. Org. Chem. 2016;81:6128. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Xu H. Golz C. Strohmann C. Antonchick A. P. Waldmann H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:7761. doi: 10.1002/anie.201602084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bai X. Li L. Xu Z. Zheng Z. Xia C. Cui Y. Xu L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016;22:10399. doi: 10.1002/chem.201601945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang Z. Xu B. Xu S. Wu H. Zhang J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:6324. doi: 10.1002/anie.201602542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CCDC no. 2299581

- CCDC no. 2299583

- Richter H. Mancheño O. G. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2010:4460. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Xu J. Hu H. Liu Y. Wang X. Kan Y. Wang C. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2017:257. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shi F. Zhang Y. Lu Z. Zhu X. Kan W. Wang X. Hu H. Synthesis. 2016;48:413. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang W. Han J. Sun J. Liu Y. J. Org. Chem. 2017;82:2835. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.