Abstract

A new insertion element, IS1549, was identified serendipitously from Mycobacterium smegmatis LR222 during experiments using a vector designed to detect the excision of IS6110 from between the promoter region and open reading frame (ORF) of an aminoglycoside phosphotransferase gene. Six of the kanamycin-resistant isolates had a previously unidentified insertion element upstream of the ORF of the aph gene. The 1,634-bp sequence contained a single ORF of 504 amino acids with 85% G+C content in the third codon position. The putative protein sequence showed a distant relationship to the transposase of IS231, which is a member of the IS4 family of insertion elements. IS1549 contains 11-bp terminal inverted repeats and is characterized by the formation of unusually long and variable-length (71- to 246-bp) direct repeats of the target DNA during transposition. Southern blot analysis revealed that five copies of IS1549 are present in LR222, but not all M. smegmatis strains carry this element. Only strains with a 65-kDa antigen gene with a PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism type identical to that of M. smegmatis 607 contain IS1549. None of 13 other species of Mycobacterium tested by PCR with two sets of primers specific for IS1549 were positive for the expected amplified product.

Insertion sequences are mobile DNA elements which can produce various types of genome rearrangements, such as deletions, inversions, duplications, and replicon fusions, by transposition within the genome (12). Most bacterial insertion sequences are 800 to 2,500 bp long, contain one or more open reading frames (ORFs), and encode a transposase which mediates movement of the element. Typically, these elements have terminal inverted repeats of 10 to 40 bp which serve as recognition sites for the transposase during the transposition process (6, 8, 12). Another characteristic of most known insertion elements is the generation of short, direct repeats of the target DNA at the point of insertion. This is presumably due to the staggered cleavage of target DNA by the transposase during the transposition process (6). The length of the direct repeats ranges from 2 to 13 bp and is a fixed characteristic of each element; however, a few elements have shown slight variations in the target duplication length (6, 8).

Insertion elements can modify gene expression by blocking transcription to inhibit gene expression or by acting as mobile promoters to activate transcription of flanking genes (6). The inhibition of gene expression is reversible in that many transposable elements are capable of excision which restores interrupted gene function (4, 6). In these experiments, we constructed a vector based on this premise to detect the excision of IS6110 from between the promoter and ORF of the aminoglycoside phosphotransferase (aph) gene of Tn5. During these experiments, we discovered a new insertion element, IS1549, from Mycobacterium smegmatis LR222, which produces unusually long and variable-length (71- to 246-bp) direct repeats of the target DNA upon insertion. To our knowledge, the production of long, variable-length direct repeats during transposition is a novel genetic event mediated by a bacterial insertion element.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1 and were obtained from the stock culture collection at the Tuberculosis/Mycobacteriology Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These strains were identified by standard biochemical procedures (10) and/or high-performance liquid chromatography (18). The Escherichia coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) strain was grown in Luria broth (LB) or on LB agar. Mycobacterium strains were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 35°C. M. smegmatis LR222 transformants were grown on Trypticase soy agar (TSA) with 50 μg of hygromycin (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.), and LR222 kanamycin-resistant mutants were selected on TSA with 50 μg of kanamycin per ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Species | Straina |

|---|---|

| E. coli | XL-1 |

| Mycobacterium spp. | |

| M. tuberculosis | 91-2609 |

| M. smegmatis | LR222 |

| 607 | |

| P22 | |

| TMC1515 | |

| TMC1519 | |

| TMC1583 | |

| 87-609 | |

| 87-763 | |

| 91-351 | |

| 96-6082 | |

| M. avium | TMC716 |

| M. bovis | TMC412 |

| M. bovis BCG | TMC1024 |

| M. chelonae | TMC1524 |

| M. fortuitum | TMC1547 |

| M. gordonae | TMC1325 |

| M. intracellulare | ATCC 1411 |

| M. kansasii | ATCC 12478 |

| M. marinum | TMC1218 |

| M. nonchromogenicum | |

| M. scrofulaceum | TMC1309 |

| M. tuberculosis | H37Rv |

| M. vaccae | TMC1526 |

| M. xenopi | 80184 |

TMC strains are from the Trudeau Mycobacterial Culture Collection.

DNA manipulations.

All enzyme reactions were performed as recommended by the manufacturers (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md., and New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). Wizard Plus Minipreps Kits (Promega, Madison, Wis.) were used to isolate plasmid DNA from E. coli. Genomic DNA was purified by the sodium dodecyl sulfate-proteinase K method from mycobacterial cultures as previously described (21). Crude lysates from mycobacterial cultures used in the PCR analysis were prepared by a bead lysis method which has been described previously (16).

Construction of pK6110 and pK6110-t4a4.

The Tn5 aph gene was recovered from pUC4-KIXX (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.) as a 1.6-kb HindIII fragment and cloned into pBluescript KS+ (Stratagene), yielding pBlue+kan. A 1.4-kb fragment containing IS6110 was generated by PCR from Mycobacterium tuberculosis 91-2609 using primers FA-BglII and NTF-1R-BglII which contain BglII sites (see Table 2) and then cloned into pCR-Script (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The 1.4-kb fragment containing IS6110 was excised from this plasmid (pSC-wT4A3) with BglII and inserted into the BglII site between the promoter and ORF of the aph gene in pBlue+kan. We selected a recombinant that had the 1.4-kb IS6110 fragment inserted such that the IS6110 ORF was in the orientation opposite that of the ORF of the aph gene. A fragment containing the aph gene and inserted IS6110 was removed with HindIII and inserted into HindIII-cleaved pBPhin (13). The plasmid pBPhin contains the gene encoding the hygromycin B phosphotransferase protein from Streptomyces hygroscopicus and oriE from p16R1 (7) and a modified integrase gene from mycobacteriophage L1. The final construct containing the aph-IS6110 hybrid was designated pK6110; its structure is shown in Fig. 1. A second construct, pK6110-t4a4, was made in the same manner except that a mutated copy of IS6110 was inserted into the aph gene. The mutated IS6110 was constructed by PCR and contained an additional base in the DraI site which introduced a frameshift to fuse the two ORFs.

TABLE 2.

PCR and sequencing primers

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| FA-BglII | ATCAGATCTCCTCGGTGCCTCACGTA | 13 |

| NTF-1R-BglII | CTAAGATCTATGCCTCACGGCGGTC | 13 |

| FA107 | CGACTTGACTCACCAAGAATG | 13 |

| NTF-1R | CCATGCCTCACGGCGGTC | 13 |

| aphTN5 | GCGAAACGATCCTCATCCTG | 2 |

| aphTN5-1F | ACAGCAAGCGAACCGGAATTGC | 2 |

| aphTN5-2F | ATCAAGATCTGATCTAGAGACAGG ATGAGG | 2 |

| aphTN5-4R | CCGCTCAGAAGAACTCGTCAAG | 2 |

| IS54 | TCGACTGGTTCAACCATCGCCG | 20 |

| IS56 | GCGACCTCACTGATCGCTGC | 20 |

| IS59 | GCGCCAGGCGCAGGTCGATGC | 20 |

| IS60 | GATCAGCGATCGTGGTCCTGC | 20 |

| 18K-1F | GGCCGGAATTTGCGCACTAAG | This study |

| 18K-2R | CTTAGTGCGCAAATTCCGGCC | This study |

| 18K-3F | GTGAAGATCAAGGCCGGCACC | This study |

| 18K-4R | GGTGCCGGCCTTGATCTTCAC | This study |

| 18K-6R | CTCCAGCGTGCGGTTCACC | This study |

| 18K-7R | GGTGCTATTCGATGTGAGCACC | This study |

| F1.6-2F | CCAGAACGAACCACCTGCG | 13 |

| F1.6-1F | GCGTCGCCCGGTCATGCC | 13 |

| 6120-1F | GAGCAATGATCAATACCTGTGGAT GAG | 9 |

| 6120-6R | GAGGAATTGTCAATACCTGTGGATCG | 9 |

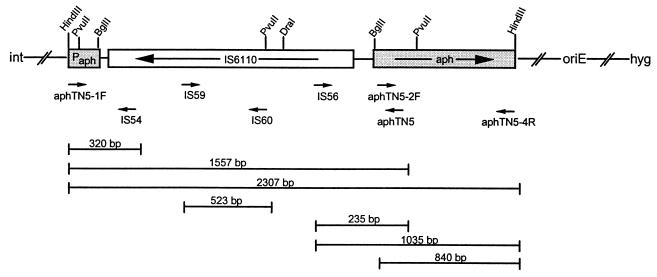

FIG. 1.

Structure of pK6110. The plasmid pK6110 contains a modified integrase gene from mycobacteriophage L1, insertion element IS6110 between the promoter and ORF of the Tn5 aph gene, an E. coli origin of replication, and the gene encoding hygromycin B phosphotransferase. Integration of this construct into M. smegmatis LR222 yields transformants which are Hygr and Kans. The arrows below the map of pK6110 indicate the locations and orientations of the primers used in PCR to compare the kanamycin-resistant mutants to the parent strains. The lines below the primer arrows indicate the sizes and contents of the expected PCR products from the original integrated construct in the parent strains.

Isolation of kanamycin-resistant mutants.

Plasmid DNA was electroporated into M. smegmatis LR222, and the recipients were plated on TSA with hygromycin to select for transformants with integrated pK6110 or pK6110-t4a4. Well-separated single colonies were picked from the transformants, inoculated into Middlebrook 7H9 broth with hygromycin, and incubated overnight at 35°C on a roller drum. The individual broth cultures were then diluted and inoculated onto TSA plates with kanamycin and TSA plates with hygromycin. From each set of plates, a parental strain (Hygr Kans) and kanamycin-resistant strain (Hygr Kanr) were isolated and grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth with the appropriate antibiotic. Genomic DNA preparations and crude cell lysates were made for each strain as described above.

Southern blot analysis.

Restriction enzyme-digested genomic DNA was electrophoresed on a 1.0% agarose gel and then denatured, neutralized, and transferred by capillary blotting to a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) as previously described (14). The membranes were probed with a 1,486-bp PCR product (primers 6120-1F plus 6120-6R) homologous with IS6120 or a 1,493-bp PCR product (primers 18k-1F and 18k-4R) homologous to IS1549. The DNA probe was labeled with the ECL direct nucleic acid labeling and detection system (Amersham). The membrane was hybridized in the manufacturer’s hybridization buffer containing 0.1 M NaCl at 42°C overnight and washed under stringent conditions at 42°C in 7.5 mM sodium citrate–75 mM sodium chloride–0.4% sodium dodecyl sulfate–6 M urea. After development with the ECL detection solutions, signals were detected by using X-OMAT AR autoradiography film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.).

PCR.

The primers used in this study and their sequences are listed in Table 2. Primers were synthesized on a 381A DNA synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) at the Biotechnology Core Facility, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Amplification reaction mixtures contained 10 μl of template DNA and 90 μl of a reaction mixture (200 μM [each] deoxynucleotide triphosphates, 1.0 μM [each] primer, 1.25 U of Taq polymerase, 10 mM Tris hydrochloride [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.01% gelatin), as recommended by the Taq polymerase supplier (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.). The samples were amplified through 30 cycles in a DNA Thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus), with a three-step cycle of denaturation for 1.5 min at 94°C, annealing for 1.75 min at 60°C, and extension for 2.5 min at 72°C. The amplification products were analyzed by electrophoresis through an appropriate percentage agarose gel with a Tris-Borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer system and visualized by ethidium bromide fluorescence. The molecular sizes of the products were estimated by comparing the migration distances with those of either a 100-bp or 1-kb ladder (Gibco BRL).

PCR-RFLP analysis.

A two-step assay combining amplification of the hsp65 gene and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis which has been previously described (15) was used to subtype strains of M. smegmatis.

Sequencing.

PCR products were purified by using a PCR purification spin kit (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.). Sequencing was carried out with the ABI PRISM Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit with AmpliTaq DNA Polymerase FS (Applied Biosystems) and an ABI 373 DNA sequencer.

Production of M. smegmatis LR222 genomic DNA library and colony screening.

LR222 genomic DNA was digested with EcoRI and ligated into pBluescript KS+ (Stratagene) treated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (Gibco BRL); the ligation mixture was electroporated into E. coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene) cells. The library was then amplified and used for screening. Colonies were lifted onto Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham) and hybridized with a 1,493-bp PCR product homologous to IS1549 which was labeled as described above.

Computer programs used for sequence analysis.

DNA sequence was assembled by using SeqEd 675 DNA Sequence Editor, version 1.0.3 (Applied Biosystems). Comparison of protein sequences of ORFs was carried out with Wisconsin Package version 9.0, Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession number for the nucleotide sequence of insertion element IS1549 is AF006614. The GenBank accession numbers for insertion element IS1549 and the long direct repeats found in clones pSM5.5 and pSM1.7 are AF036758 and AF036759, respectively.

RESULTS

Experimental strategy.

The constructs pK6110 and pK6110-t4a4 were designed to detect the excision of IS6110. A copy of IS6110 was placed between the promoter and ORF of the aph gene so that precise excision of IS6110 would restore transcription of the aph gene, thus rendering the bacteria kanamycin resistant. The integrating plasmids were electroporated into M. smegmatis LR222, and hygromycin-resistant recipients were selected. Individual, isolated hygromycin-resistant colonies were inoculated into broth and grown overnight. To identify potential excision events, the cultures were diluted and plated on TSA-kanamycin and TSA-hygromycin plates. For each individual colony studied, we recovered about 103 CFU/ml on the TSA-kanamycin plates compared with 109 CFU/ml on the hygromycin plates. Initially, eight kanamycin-resistant mutants (designated 1K, 2K, 3K, 4K, 6K, 7K, 9K, and 10K) and their corresponding parent strains (designated 1H, 2H, 3H, 4H, 6H, 7H, 9H, and 10H) were selected for evaluation. Mutants 1K to 4K and their parent strains were derived from pK6110-t4a4 transformants and mutants 6K to 10K, and their parent strains were derived from pK6110 transformants.

Characterization of kanamycin-resistant mutants.

To determine if IS6110 had been excised, PCR was performed with aphTN5-1F, a primer specific for the promoter region of the aph gene, and aphTN5-4R, a primer complementary to the 3′ end of the aph ORF (Fig. 1). This amplification produced the expected 2,350-bp fragment from all the parent strains and one kanamycin-resistant mutant, 7K. Surprisingly, the other seven kanamycin-resistant mutants produced a product of ∼3.5 kb, which suggested that additional DNA had been inserted rather than the expected excision of IS6110. Using the ∼3.5-kb PCR product from one mutant (1K) and the 2,350-bp product from its parent (1H), a series of amplification reactions were carried out with six sets of primers (Fig. 1) corresponding to different sequences within the aph promoter region, IS6110, and the aph ORF. The results of these assays (data not shown) revealed that an insertion had occurred between the proximal 150 bp of IS6110 and the start codon of the aph ORF. Sequence analysis of the PCR product made with primers IS56 plus aphTN5 from mutant 1K revealed the presence of a previously described 1,486-bp insertion element, IS6120. The insertion occurred in the typical manner reported for IS6120 (9), creating a 9-bp direct repeat of the target DNA. Southern blot analysis of PvuII-digested genomic DNA from the eight kanamycin-resistant mutants and their parent strains, using a probe specific for IS6120, showed that five (1K, 3K, 4K, 6K, and 10K) of the eight mutants had an additional fragment of ∼2.2 kb which hybridized with the IS6120 probe, indicating an additional copy of IS6120 (data not shown).

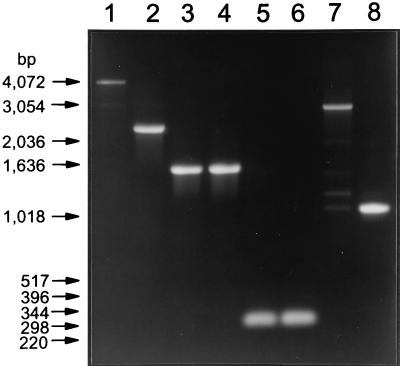

Because mutant 2K did not have an extra copy of IS6120 by Southern blotting yet appeared to have an insertion, it was further analyzed by PCR with four sets of primers (aphTN5-1F plus aphTN5-4R, aphTN5-1F plus aphTN5, IS56 plus aphTN5, and IS56 plus aphTN5-4R [Fig. 1]) corresponding to different sequences within the aph promoter region, IS6110, and the aph ORF. As seen in Fig. 2, the PCR products using aphTN5-1F plus aphTN5-4R and IS56 plus aphTN5-4R revealed that an insertion had occurred within the proximal 150 bp of IS6110 and the aph ORF. In contrast, the PCR products using aphTN5-1F plus aphTN5 and IS56 plus aphTN5 from the kanamycin-resistant mutant and parent were both the sizes expected if no extra DNA were present.

FIG. 2.

PCR of mutant 2K and its parent 2H to determine site of insertion. The templates for amplification were cell lysates made from kanamycin-resistant mutant 2K (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) and parent strain 2H (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). Primers used for amplification were TN5-1F plus TN5-4R (lanes 1 and 2), TN5-1F plus TN5 (lanes 3 and 4), IS56 plus TN5 (lanes 5 and 6), and IS56 plus TN5-4R (lanes 7 and 8).

The primer set of IS56 plus aphTN5-4R was also used to amplify the original group of mutants, except for 1K, as well as 10 additional sets of kanamycin-resistant mutants (11K, 12K, 13K, 14K, 15K, 16K, 17K, 18K, 19K, and 25K) and corresponding parent strains (11H, 12H, 13H, 14H, 15H, 16H, 17H, 18H, 19H, and 25H). Mutants 11K to 19K and their parent strains were derived from pK6110-t4a4 transformants; mutant 25K and its parent strain were derived from pK6110 transformants. All kanamycin-resistant mutants, except 7K and 14K, gave an ∼2.8-kb product in the PCR instead of the expected 1-kb fragment seen in the parent strains (data not shown). Sequence analysis of the ∼2.8-kb PCR products revealed that mutants 2K, 9K, 11K, 16K, 18K, and 25K contained identical inserted DNA which displayed no homology to IS6120 or to any other sequence in the GenBank database. Interestingly, all six mutants could be successfully sequenced with the IS56 primer; however, only mutant 18K could be sequenced with primer aphTN5.

Discovery of long direct repeats.

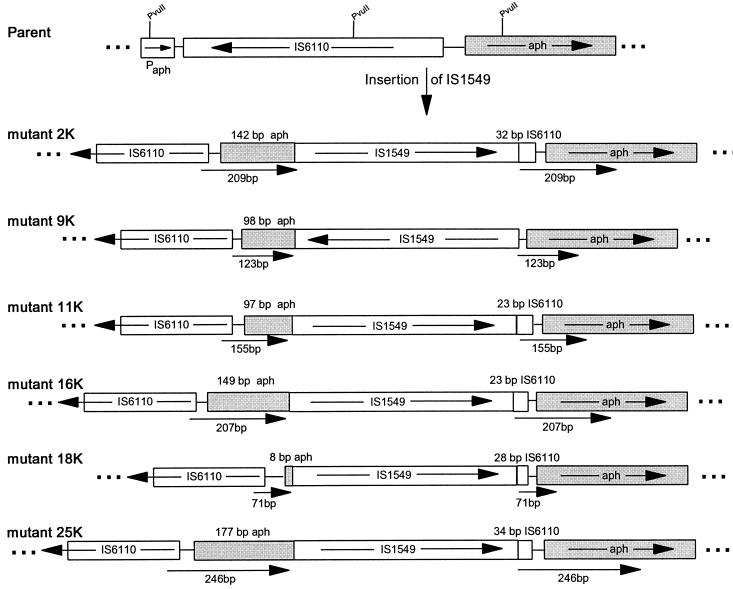

Primers 18K-2R and 18K-3F (see Fig. 4), which were complementary to sequences near the ends of the novel inserted DNA element and facing outward, were designed from the sequences obtained from mutant 18K and used to sequence across the junctions of the insertions. Analysis of sequences obtained by using these two primers revealed that the novel DNA element had been inserted in the same orientation within the proximal 35 bp of IS6110, upstream of the aph ORF, except for mutant 9K, which was in the opposite orientation and inserted in the sequence between IS6110 and the aph ORF. The most remarkable result was that the novel DNA element was flanked by long and variable-length direct repeats of the target DNA, ranging from 71 to 246 bp (Fig. 3).

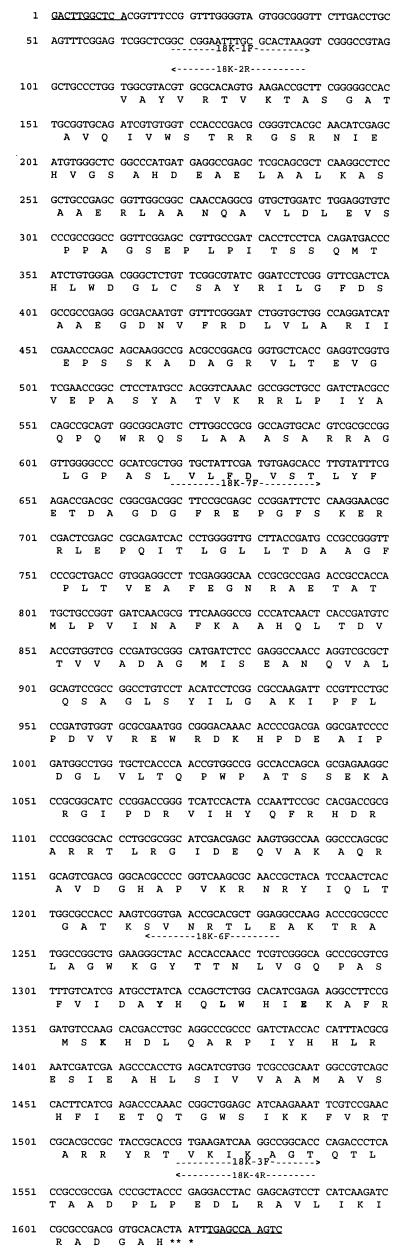

FIG. 4.

DNA sequence of IS1549. The 11-bp inverted repeats are indicated by underlining. The 504-amino-acid ORF is shown as well as the positions of the primers (indicated beneath the sequence by arrows) used for sequence analysis and PCR to determine the distribution of the element. The amino acid sequence which has homology to the highly conserved C1 signature sequence [Y-(X2)-R-(X3)-E-(X6)-K] of the IS4 family of insertion elements is shown in bold type.

FIG. 3.

Structure of IS1549 insertion site in mutants. Kanamycin-resistant mutants 2K to 25K were formed by the insertion of IS1549 within the end of IS6110 or the sequence flanking IS6110. The map for each mutant shows the portion of the aph gene and IS6110 sequence which was duplicated to form the long, variable-length direct repeats; the arrows beneath each map indicate the lengths of the direct repeats.

Insertion element IS1549.

The novel inserted DNA from mutant 18K was sequenced completely on both strands (Fig. 4). The sequence contains 1,634 bp with 11-bp terminal inverted repeats and a single ORF of 504 amino acids with an 85% G+C content in the third codon position, which is typical of ORFs in mycobacteria. The putative protein sequence has a 23.2% identity in a 151-amino-acid overlap (residues 266 to 479) with the transposase from insertion element IS231A, suggesting a distant relationship to the IS4 family of insertion elements. This 1,634-bp element has been designated IS1549 by the Plasmid Reference Center, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, Calif.

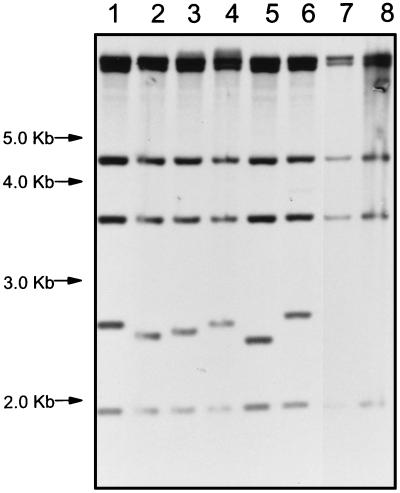

Southern blot analysis with IS1549 probe.

Analysis of the PvuII-digested DNA from strain LR222, LR222 with pK6110 integrated, and the six kanamycin-resistant mutants which had undergone insertion of IS1549 revealed that LR222 contains five copies of IS1549 (IS1549 does not contain a PvuII site) and that each of the kanamycin-resistant mutants had acquired an additional copy carried on a fragment of about 2.5 kb (Fig. 5). The variation in the size of the fragments among the different mutants is due to the variation in the size of the long direct repeats formed upon insertion.

FIG. 5.

Southern blot of kanamycin-resistant mutants with IS1549 probe. PvuII-digested genomic DNA from kanamycin-resistant mutants 2K, 9K, 11K, 16K, 18K, and 25K (lanes 1 to 6, respectively), parent strain 25H (lane 7), and LR222 (lane 8) hybridized with the IS1549 probe is shown.

Flanking sequence of native copies of IS1549 in M. smegmatis LR222.

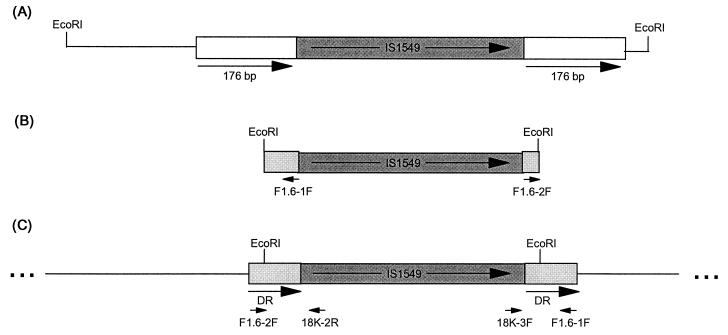

Two clones that contained IS1549 were isolated from a library of EcoRI fragments of LR222 cloned in pBluescript; pSM5.5 contained an ∼5.5-kb insert, and pSM1.7 contained an ∼1.7-kb insert (data not shown). Sequence analysis using primers 18K-2R and 18K-3F revealed that pSM5.5 contained a copy of IS1549 with a 176-bp direct repeat (Fig. 6). Clone pSM1.7 contained a copy of IS1549 with 60- and 31-bp flanking sequences ending in EcoRI sites. To determine if the lack of direct repeats in this clone was an artifact of cloning EcoRI fragments, primers F1.6-2F and F1.6-1F (Fig. 6) were designed by using the sequence obtained from the DNA flanking IS1549 and paired with either primer 18K-2R or 18K-3F, respectively, for PCR. The amplification of LR222 genomic DNA with either primers F1.6-2F plus 18K-2R or F1.6-1F plus 18K-3F produced fragments of the expected size (∼200 bp), and the sequences of both of these products showed the expected IS1549 sequence with a combination of the 60- and 31-bp flanking sequence seen in pSM1.7. This indicates that a long direct repeat containing an EcoRI site did flank this copy of IS1549 in the genome (Fig. 6), although the exact length could not be verified because of limitations within the procedure. Comparison of the sequences of these two sites of insertion as well as the insertion in the integrated pK6110 construct did not reveal homology that could be considered a site-specific target for IS1549. An interesting finding, however, was that the long direct repeat associated with the copy of IS1549 in pSM5.5 was completely homologous to nucleotides 1244 to 1420 of the previously reported insertion element IS6120 (GenBank accession no. M69182).

FIG. 6.

Long direct repeats in native copies of IS1549. (A) Map of the EcoRI fragment containing IS1549 in clone pSM5.5. The large arrows below the map indicate the direct repeat of 176 bp. (B) Map of the EcoRI fragment containing IS1549 in clone pSM1.7. Sequence analysis of the IS1549 flanking region revealed 60 bp at the 5′ end and 30 bp at the 3′ end of IS1549. The short arrows indicate the locations and orientations of the primers designed to determine if a long direct repeat existed. (C) Map of the genomic sequence flanking the EcoRI sites of the insert from pSM1.7. The short arrows indicate the orientations and locations of the primers used in PCR. The long arrows represent the direct repeats (DR) of at least 90 bp (the exact length could not be verified because of limitations within the procedure). The nucleotide sequence for the flanking region containing the long direct repeats for each of these IS1549 insertions is available in GenBank (see “Nucleotide sequence accession numbers” above for the accession numbers).

Distribution of IS1549.

To determine the distribution of IS1549 among the subtypes of M. smegmatis, four strains were analyzed by Southern blotting using a probe homologous to IS1549. Strains LR222 and 607 each had five copies of IS1549, whereas P22 and clinical isolate 96-6082 did not hybridize with the probe (data not shown). Eight strains of M. smegmatis (LR222, 607, TMC1515, TMC1519, TMC1583, 91-351, 87-763, and 87-609) were then analyzed by PCR with two separate sets of primers specific for IS1549, 18K-1F plus 18K-4R, and 18K-7F plus 18K-6R (Fig. 4). Only five of these strains (LR222, 607, TMC1515, TMC1519, and TMC1583) carry IS1549, and these five strains have the same pattern in a PCR-RFLP typing analysis (15) based on the 65-kDa gene, whereas the three strains negative for IS1549 in the PCR make up two different groups by the PCR-RFLP typing method. Thirteen other species of Mycobacterium (Table 1) were evaluated by PCR with the two sets of IS1549 primers, and none gave the expected size PCR products (not shown). Therefore, IS1549 has a narrow distribution in that it is present only in subtypes of M. smegmatis with a PCR-RFLP pattern identical to that of strain 607.

DISCUSSION

The predicted amino acid sequence of the ORF of IS1549 has a 23.2% identity in a 151-amino-acid overlap with the transposase from IS231A. This 151-amino-acid sequence contains the highly conserved C1 region which corresponds to the C-terminal box and displays the C1 signature sequence Y-(X2)-R-(X3)-E-(X6)-K (16). The corresponding IS1549 sequence is Y-(X2)-L-(X3)-E-(X6)-K. IS231A is a member of the IS4 family of insertion elements which is defined by the following characteristics: (i) homology in the C1 region; (ii) homology in a second region, N3, which lies in the amino-terminal half of the transposase; and (iii) separation of these two regions by up to 110 amino acid residues (17). IS1549 shows no homology with the IS231A N3 region, therefore the relationship of IS1549 to the IS4 family of elements is distant. An interesting aspect of the IS4 family is that two other mycobacterial insertion elements, IS1096 from M. smegmatis (3) and ISTUB from M. tuberculosis (11), have homology to the C1 and N3 conserved regions. However, the ORFs of IS1096 and ISTUB do not show significant homology with the IS1549 ORF. IS1096 and ISTUB also form typical direct repeats of 8 and 4 bp, respectively (3, 11).

IS1549 was discovered in an attempt to detect excision of IS6110. Although restoration of gene expression by excision of other bacterial insertion elements has been documented (4, 6), in our system the restoration of gene expression was mediated by the insertion of another insertion element, either IS1549 or IS6120, upstream of the ORF of the aph gene. These results were not too surprising, because the promoter activity of bacterial insertion elements has been well documented (6) and a recent report described construction of a transposon trap based on this activity (19). Szeverenyi et al. (19) reported that the majority of IS elements resident in the studied E. coli strains became trapped in a vector with a promoterless antibiotic resistance gene. The promoter activity produced by the insertion element could be due to insertion of a complete promoter region facing outward from the insertion element or the formation of a composite promoter upon insertion. The possibility of a composite promoter being formed in mycobacteria is enhanced by the fact that mycobacterial promoters tolerate a wide variety of sequences in the −35 region (1). The insertion of IS1549 in the forward direction in five mutants within a 12-bp region at the 5′ end of IS6110 is consistent with the formation of a composite promoter to restore transcription of the aph gene. The results of this study in which two insertion elements were trapped by their ability to restore gene expression show that this strategy may have general application as a trap for insertion elements in mycobacteria.

An unusual aspect of IS1549 is that instead of producing constant-length, short direct repeats like most insertion elements, this element produces long direct repeats which can vary in length. Although this variation ranged from 71 to 246 bp based on our analysis of insertions, the actual range is unknown. The presence of such long repeats explains our unexpected PCR results. For example, mutant 2K has a 209-bp direct repeat which includes 32 bp of IS6110 and 142 bp of the aph gene, but amplification with primers aphTN5-1F plus aphTN5 and IS56 plus aphTN5 gave the same size product as the parent strain despite insertion of IS1549. This occurred because the sequence complementary to primer aphTN5 had been duplicated during transposition and the shorter amplification product was favored during amplification. Since the sequence complementary to primers aphTN5-1F plus aphTN5-4R and IS56 plus aphTN5-4R had not been duplicated, these primers produced amplicons larger than the product amplified from the parent as expected from the insertion of IS1549. The formation of the long direct repeats also explains the inability to use primer aphTN5 in the sequencing reactions. In all the mutants except 18K, the sequences complementary to primer aphTN5 had been duplicated; therefore, the sequence data actually contained two sets of sequence data neither of which could be read accurately.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a bacterial insertion element forming long, variable-length direct repeats of the target DNA upon transposition. Not only were the long direct repeats seen in the transposition of IS1549 into our integrated construct, but they were also documented in a native copy of IS1549, and evidence was presented that long direct repeats existed for a second native copy of IS1549 though the exact length could not be determined. The fact that IS1549 found in clone pSM5.5 had inserted into a known sequence, insertion element IS6120, supports the hypothesis that these long direct repeats are generated during the insertion of IS1549. Although the actual mechanism of the formation of the long, variable-length direct repeats is unknown, the fact that the duplications vary in length suggests that a nick is made in a single strand of the target DNA, which is ligated with a single-strand end of the insertion element, and a replication fork is then formed as described in the model for transposition by Galas and Chandler (5) and reviewed by Grindley and Reed (8). However, unlike previously described insertion elements, the nick in the second strand seems to be unrelated to the first. This hypothesis is supported by the analysis of the insertion of IS1549 in mutants 11K and 16K. Although IS1549 is inserted at the exact same site in the 5′ end of IS6110, the direct repeats formed are 155 and 207 bp, respectively, indicating that the nick in the second strand occurred at two different points. Further study is required to determine the mechanism of transposition of IS1549 as well as the formation of long, variable-length direct repeats upon insertion.

The insertion element IS1549 identified from M. smegmatis has demonstrated its ability to transpose and contains inverted repeats at its ends typical of other insertion sequences. However, the production of long, variable-length direct repeats of target DNA upon transposition makes this a novel element and suggests that its mechanism of transposition may be significantly different from that described for other insertion elements. Also, the lack of significant homology to other known insertion elements suggests that IS1549 may be the first member of a new class of insertion elements to be described.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Douglas Young for providing plasmid p16R1, Charles Woodley and Suzanne Glickman for providing M. smegmatis strains, Jonathan Mills for conversations which lead to interest in the frequency of transposition of IS6110, and Gordon Churchward for enlightening discussions and critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bashyam M D, Kaushal D, Dasgupta S K, Tyagi A K. A study of the mycobacterial transcriptional apparatus: identification of novel features in promoter elements. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4847–4853. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4847-4853.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck E, Ludwig G, Auerswald E A, Reiss B, Schaller H. Nucleotide sequence and exact localization of the neomycin phosphotransferase gene from transposon Tn5. Gene. 1982;19:327–336. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cirillo J D, Barletta R G, Bloom B R, Jacobs W R. A novel transposon trap for mycobacteria: isolation and characterization of IS1096. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7772–7780. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.24.7772-7780.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster T J, Lundblad V, Hanely-Way S, Halling S M, Kleckner N. Three Tn10-associated excision events: relationship to transposition and role of direct and inverted repeats. Cell. 1981;23:215–227. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galas D J, Chandler M. On the molecular mechanisms of transposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:4858–4862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galas D J, Chandler M. Bacterial insertion sequences. In: Berg D E, Howe M M, editors. Mobile DNA. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 109–162. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garbe T R, Barathi J, Barnini S, Zhang Y, Abou-Zeid C, Tang D, Mukherjee R, Young D B. Transformation of mycobacterial species using hygromycin resistance as selectable marker. Microbiology. 1994;140:133–138. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-1-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grindley N D F, Reed R R. Transpositional recombination in prokaryotes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:863–896. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.004243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guilhot C, Gicquel B, Davies J, Martin C. Isolation and analysis of IS6120, a new insertion sequence from Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:107–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kent B D, Kubica G P. Public health mycobacteriology: a guide for the level III laboratory. U.S. Atlanta, Ga: Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mariani F, Piccolella E, Colizzi V, Rappuoli R. Characterization of an IS-like element from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1767–1772. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-8-1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohtsubo E, Sekine Y. Bacterial insertion sequences. In: Saedler H, Gierl A, editors. Transposable elements. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1996. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plikaytis, B. B. Unpublished data.

- 14.Plikaytis B B, Marden J, Crawford J T, Woodley C L, Butler W R, Shinnick T M. Multiplex PCR assay specific for the multidrug-resistant strain W of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1542–1546. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.6.1542-1546.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plikaytis B B, Plikaytis B D, Yakrus M A, Butler W R, Woodley C L, Silcox V A, Shinnick T M. Differentiation of slowly growing Mycobacterium species, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, by gene amplification and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1815–1822. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1815-1822.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plikaytis B B, Gelber R H, Shinnick T M. Rapid and sensitive detection of Mycobacterium leprae using a nested-primer gene amplification assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1913–1917. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.1913-1917.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rexsohazy R, Hallet B, Delcour J, Mahillon J. The IS4 family of insertion sequences: evidence for a conserved transposase motif. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:1283–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steering Committee of the HPLC Users Group. Standardized method for HPLC identification of mycobacteria. U.S. Atlanta, Ga: Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szeverenyi I, Hodel A, Arber W, Olasz F. Vector for IS element entrapment and functional characterization based on turning on expression of distal promoterless genes. Gene. 1996;174:103–110. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00407-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thierry D, Cave M D, Eisenach K D, Crawford J T, Bates K H, Gicquel B, Guesdon J L. IS6110, an IS-like element of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:188. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.1.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson K. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman I G, Smith J A, Stuhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Wiley Interscience; 1990. pp. 2.4.1–2.4.2. [Google Scholar]