Abstract

The genes encoding xylose isomerase (xylA) and xylulose kinase (xylB) from the thermophilic anaerobe Thermoanaerobacter ethanolicus were found to constitute an operon with the transcription initiation site 169 nucleotides upstream from the previously assigned (K. Dekker, H. Yamagata, K. Sakaguchi, and S. Udaka, Agric. Biol. Chem. 55:221–227, 1991) promoter region. The bicistronic xylAB mRNA was processed by cleavage within the 5′-terminal portion of the XylB-coding sequence. Transcription of xylAB was induced in the presence of xylose, and, unlike in all other xylose-utilizing bacteria studied, was not repressed by glucose. The existence of putative xyl operator sequences suggested that xylose utilization is controlled by a repressor-operator mechanism. The T. ethanolicus xylB gene coded for a 500-amino-acid-residue protein with a deduced amino acid sequence highly homologous to those of other XylBs. This is the first report of an xylB nucleotide sequence and an xylAB operon from a thermophilic anaerobic bacterium.

Thermophilic anaerobic bacteria have attracted much interest for use in the bioconversion of industrial and agricultural lignocellulosic waste materials into vendable chemicals (35). Some of these microorganisms have potent xylanolytic capacity and can metabolize pentose sugars, including xylose. Bacteria convert xylose to xylulose by xylose (glucose) isomerase, XylA. Xylulose is then phosphorylated by xylulose kinase (XylB) to yield xylulose-5-phosphate, which enters either the pentose phosphate pathway or the phosphoketolase pathway (22). The genetic organization and regulation of expression of xylose utilization genes have been described for a variety of bacteria (4). However, except for xylA and its gene product, which is important for the commercial production of high-fructose corn syrup (4), there is no published information on the organization or regulation of xylose utilization genes in thermoanaerobes.

Our original goal was to isolate xylose metabolism genes from a supposed xylose-utilizing strain of another anaerobe, Clostridium thermocellum JW20 (18), but in the course of our study it became evident that strain JW20 was actually a coculture of the Clostridium species with Thermoanaerobacter ethanolicus (16). T. ethanolicus is a gram-positive xylanolytic anaerobic thermophile that produces considerable amounts of ethanol during fermentation (59). There has been intensive study of xylan degradation by T. ethanolicus (59), and its xylA gene was previously sequenced (10), but nothing further was known about the molecular basis of xylose metabolism in this organism. In this report, we show that xylA and xylB in T. ethanolicus are organized in an operon, and the deduced sequence of the T. ethanolicus XylB protein is compared to those of its homologs. In addition, we present evidence that the regulation of xylose utilization in T. ethanolicus is mediated at the transcriptional level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and contaminant detection.

C. thermocellum JW20 (ATCC 31549) was obtained directly from the American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md., and grown as previously described (16). This culture served as the source of genomic DNA for the gene library construction. A clone (pXI-10) harboring xylAB was isolated, but sequence analysis revealed that xylA was virtually identical to xylA from T. ethanolicus (reference 10 and this study). This observation indicated contamination of the JW20 strain with T. ethanolicus, which was confirmed by a 16S rRNA PCR-based assay (16). To firmly rule out the existence of genes for xylose utilization in C. thermocellum JW20, a Southern analysis was performed (46) with equal amounts of HindIII-digested genomic DNAs from pure bacterial cultures against either xylA- or xylB-specific probes, and, under low stringency conditions, both genes were detected only in the T. ethanolicus DNA (data not shown). All subsequent experiments in this study, i.e., the transcription characterization, were carried out with freshly purchased T. ethanolicus 39E (ATCC 33223), which was grown as described previously (16). Plasmid pUC18 was used as a cloning vector, and Escherichia coli DH5α was used as a transformation host (both purchased from Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.).

Genomic library construction and screening.

Cells in the late logarithmic growth phase were washed twice with 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.0), and genomic DNA was isolated as previously described (27) except that dialysis steps were omitted. To construct the genomic library, the 4- to 7-kb chromosomal DNA fragments resulting from the Sau3A partial digest were gel purified and ligated with BamHI-cut and dephosphorylated pUC18. An aliquot of the ligation mix was electroporated into E. coli DH5α, and the transformants were plated onto Luria-Bertani agar plates containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml (2).

The probe to screen the genomic library was generated by PCR with oligonucleotides XI-3 (5′ TTT CAY GAY AGR GAY ATW GCW CC) and XI-4 (5′ TCA TAW CCT TCY CTW CCW CCC), which were designed on the basis of strongly conserved regions from the amino acid sequence alignment of XylAs. In a PCR with a genomic DNA template, a unique 300-bp amplification product was obtained. The gel-purified xylA fragment was labelled by using a random hexamer kit with digoxigenin-dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) and used for the library screening. Labelling, hybridization, washes, and detection were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

DNA sequencing and analysis.

DNA sequencing was performed on an Applied Biosystems 373A automated sequencer at the Macromolecular Structure Analysis Facility at the University of Kentucky. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Corallville, Iowa). Sequence analyses were performed by using the Lasergene software (DNASTAR, Madison, Wis.). BLAST search engines were employed for sequence homology searches (1).

RNA isolation and analyses.

Cells were harvested during logarithmic growth and washed once in 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), and RNA was isolated with RNeasy Total RNA mini-prep kits (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.). For Northern analysis, aliquots of total RNA (5 μg) were fractionated in a 1% agarose–formaldehyde gel, blotted, and hybridized to [α-32P]dATP-labelled xylA or xylB DNA fragments according to standard protocols (46). The xylA probe was a PCR-amplified 412-bp fragment from the xylA open reading frame (ORF), while the xylB probe was the 584-bp HindIII fragment from the xylB ORF (Fig. 1).

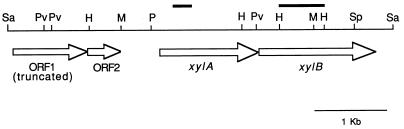

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of pXI-10. ORFs are indicated by open arrows. Thick black lines represent fragments used as probes in Northern analysis. H, HindIII; M, MfeI; P, PstI, Pv, PvuII; Sa, Sau3A; Sp, SpeI.

For dot blot analysis, 1.5-μl aliquots of various dilutions of total cell RNA were spotted onto a membrane, which was then UV-cross-linked and hybridized to the radiolabelled xylA-specific probe (46). The resulting signal intensities were quantified with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Inc.). Relative intensities of the signals obtained were calculated as previously described (53).

Primer extension analysis was performed by using oligonucleotides PEX-19 (5′ ATG CAT ATG GAT TGT TTG ATT TTG GTC CTT C), PEX-20 (5′ CTC ATT TGA AAG CTC CGT GTG GTA TCC TG), and PEX-B (5′ CCT ATT ACA TTT CCA TTT TCC TCT AC). The primers were end labelled with [γ-32P]ATP and gel purified by standard procedures (46). Each primer (5 × 105 cpm) was annealed to 40 μg of total RNA, and primer extension reactions were performed with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, Wis) by a standard protocol (46). The cDNAs synthesized, along with the sequence ladders generated with the same primers, were electrophoresed on an 8% polyacrylamide gel with 7 M urea.

Carbohydrate and enzyme assays.

Glucose was determined enzymatically (43), xylose and xylulose were determined colorimetrically (12), mannitol was determined by using anthrone reagent (3), and cell protein was determined by a standard method (34). d-Xylose isomerase and d-xylulose kinase activities were determined at 70°C as previously described (58) by using crude extracts of cells disrupted with a French press.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete DNA sequence of the clone pXI-10 was submitted to GenBank under the accession number AF001974.

RESULTS

Nucleotide sequence of xylose utilization genes.

A single positive clone, pXI-10, was isolated by screening the chromosomal library with the 300-bp xylA-specific probe. Sequence analysis of pXI-10 revealed four ORFs of unidirectional polarity (Fig. 1). ORF1 (1,014 bp) encodes a 337-residue polypeptide showing homology to the potassium uptake protein TrkG in E. coli (50). Sequence analysis suggested that ORF1 is a part of a larger ORF whose 5′-terminal 300 bp were missing as a consequence of the cloning procedure (data not shown). Immediately downstream from ORF1 lies the second ORF (587 bp), encoding a 195-amino-acid polypeptide that has sequence similarity to the E. coli trkA gene product (49). ORF2 is followed by a possible transcriptional terminator sequence (ΔG = −19.4 kcal/mol); therefore, ORF1 and ORF2 may constitute a potassium uptake operon.

The DNA sequence of ORF3 differed from that of the previously sequenced T. ethanolicus xylA (10) in three nucleotides without altering the encoded peptide sequence. ORF4 starts 14 nucleotides downstream from the xylA translation termination codon and codes for a putative peptide of 500 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 55,533 Da. Since this protein has sequence similarity to XylBs in other organisms, it appeared that the ORF4 gene product was a xylulose kinase. The xylB ORF is preceded by a properly spaced potential ribosome-binding sequence (GGAGG).

Amino acid sequence comparison.

A multiple amino acid sequence alignment of XylBs from nine different bacterial species revealed that conserved regions were found throughout the entire XylB sequence length and were somewhat less prominent in the carboxy-terminal region (data not shown). The T. ethanolicus XylB protein showed highest sequence identity (53%) to its homolog from Bacillus subtilis (60). High homology to XylBs from Lactobacillus pentosus (33), Klebsiella pneumoniae (17), a thermophilic Bacillus sp. (30), and E. coli (26) was also observed, with 52, 50, 49, and 48% sequence identity, respectively. In addition, the T. ethanolicus XylB sequence has considerable homology with the B. subtilis gluconate kinase (19) and the Enterococcus faecalis glycerol kinase (6) (47 and 39% sequence identity, respectively). These enzymes belong to the FGGY family of carbohydrate kinases (42). Sequences matching both consensus patterns characteristic of the FGGY family were identified in T. ethanolicus XylB (data not shown). As with other XylBs, no sequence regions representing ATP-binding domains, as defined by Chin et al. (7), were observed in the T. ethanolicus XylB sequence.

Transcript characterization.

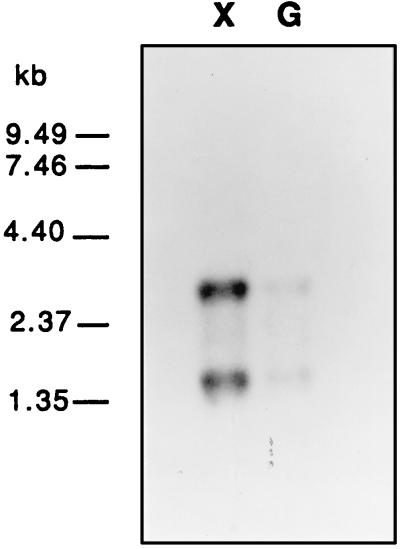

Given the mere 14-bp spacing between the xylA and xylB ORFs, it was reasonable to predict that the two genes were transcribed together as a bicistronic operon. To verify this assumption, Northern analysis was performed by hybridizing a 412-bp fragment from xylA to the total RNA isolated from T. ethanolicus 39E grown with either xylose or glucose. The autoradiograph (Fig. 2) showed two discrete bands, approximately 3.0 and 1.5 kb in size, that were more intense in the RNA sample from the xylose-grown cells than in that from the cells grown on glucose. The same result was obtained when a 584-bp HindIII fragment from xylB was hybridized to an identical Northern blot (data not shown). These results indicated that expression of xylose utilization genes is likely to be transcriptionally regulated. In addition, the presence of the 3-kb band suggested that xylA and xylB are cotranscribed as a bicistronic mRNA that is processed by cleavage.

FIG. 2.

Northern analysis. Total RNA was isolated from cells logarithmically growing with 0.4% xylose (lane X) or glucose (lane G). RNA samples (5 μg per lane) were fractionated in 1% formaldehyde–agarose gel, blotted, and hybridized to the α-32P-labelled 412-bp PCR fragment from xylA.

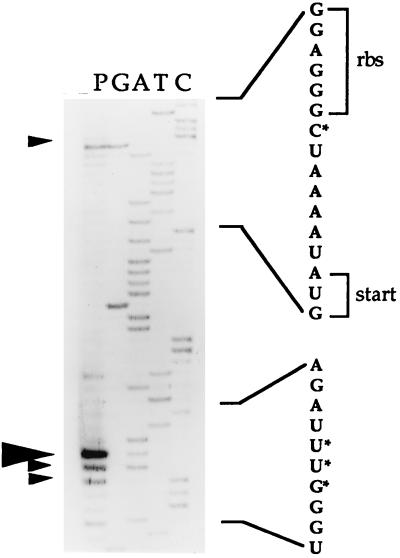

To gain further insight into xylAB transcript processing, primer extension analysis was performed with total RNA from xylose-grown cells and the oligonucleotide B-PEX, which is complementary to the 5′ region of xylB. Several cleavage sites were identified in the xylAB transcript (Fig. 3), a major one 19 nucleotides downstream from the xylB initiation codon and three minor sites, one of them proximal to the putative ribosome-binding sequence of the xylB mRNA. None of the sequences surrounding the cleavage sites had any resemblance to the RNase E cleavage consensus (reference 14 and data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Identification of the xylAB transcript cleavage site(s). Primer extension analysis was performed by using 5 × 105 cpm of the end-labelled primer PEX-B and 40 μg of RNA from T. ethanolicus grown on 0.4% xylose. A reaction aliquot (lane P) was electrophoresed on a denaturing 8% polyacrylamide gel along with the sequence ladder (lanes G, A, T, and C) generated with PEX-B. Large and small arrowheads represent major and minor cleavage sites, respectively. Portions of the RNA sequence predicted from the coding strand, which is complementary to the sequence shown in the autoradiograph, are indicated. rbs, ribosome-binding sequence; start, translation initiation codon of xylB; asterisks, cleavage sites.

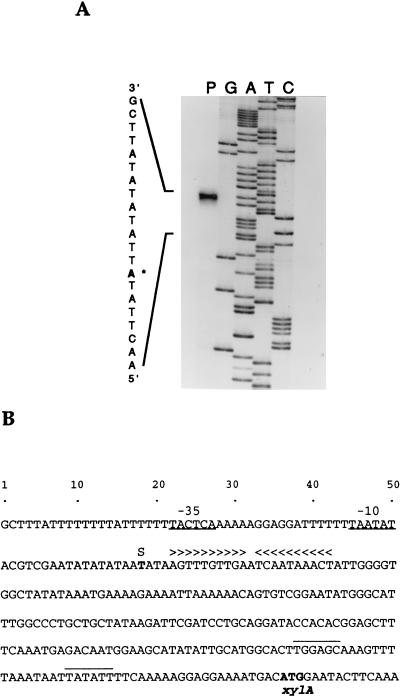

Determination of the transcription initiation site for the xylAB operon was conducted by primer extension analysis. In the original report on cloning of xylA from T. ethanolicus (10), −10 and −35 sites of the xylA promoter were tentatively assigned to the region within 40 bp upstream from the xylA ORF. Hence, an oligonucleotide (PEX-19) complementary to the sequence proximal to the translation initiation codon was designed so that an approximately 100-bp cDNA product could be obtained in the primer extension reaction. Surprisingly, our result showed that the 5′ end of the xylAB mRNA was located 217 nucleotides upstream of the xylA translation initiation codon (Fig. 4A). The primer extension analysis was repeated with another primer (PEX-20), located 27 nucleotides upstream from the previously assigned −35 site (10), and the same cDNA product was obtained (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Determination of the xylAB mRNA 5′ end. (A) Primer extension analysis was carried out with the oligonucleotide PEX-19 and RNA from xylose-grown cells. Lanes: P, primer extension aliquot; G, A, T, and C, sequence ladder generated with PEX-19. The +1 site is marked by an asterisk. (B) Nucleotide sequence of the T. ethanolicus xylAB operon 5′ terminus, indicating previously assigned (10) promoter sequences (overlined), the transcription initiation site (S), and putative −35 and −10 regions (underlined) deduced from our transcript analysis. A dyad symmetry region is indicated by arrowheads above the sequence.

Sequences that could comprise the xylAB promoter are TACTCA (−35 site) and TAATAT (−10 site), and they are separated by a 17-bp spacer (Fig. 4B). The −35 sequence is less similar to the −35 consensus (TTGACA) defined for E. coli (24) or for gram-positive bacteria (23) than the xylAB −10 region, compared to the corresponding sequence consensus (TATAAT). Upstream from the −35 site there is a poly(T) stretch, which is characteristic of strong promoters in B. subtilis (39). A potential transcription termination hairpin (ΔG = −10.5 kcal/mol) is situated 18 bp downstream from the translational end of xylB.

Regulation of xylAB expression.

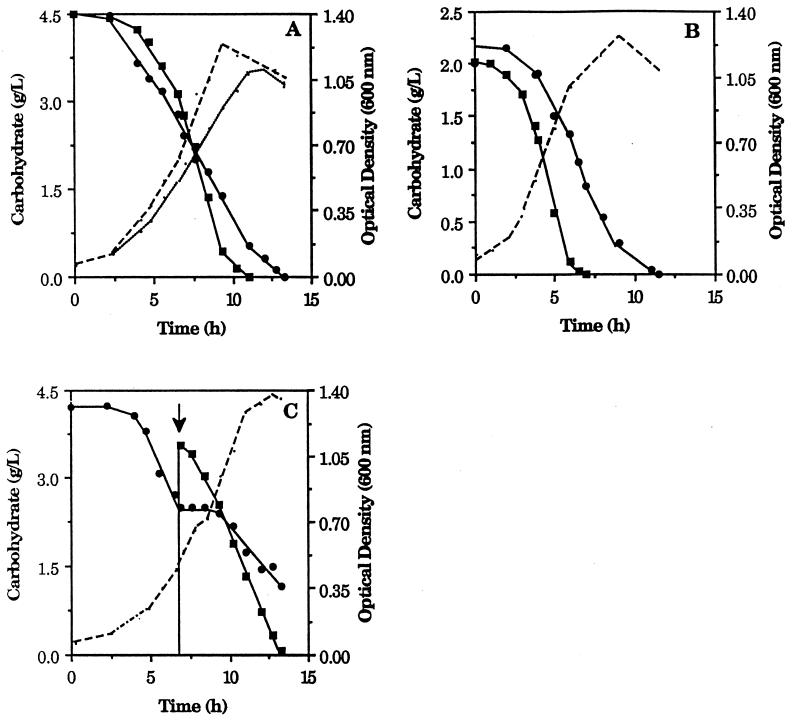

In order to determine how the expression of the xylAB operon in T. ethanolicus 39E is affected by different carbon sources, cultures were grown with either 0.4% glucose or xylose as a single substrate or with both substrates at a total initial sugar concentration of 0.4%. In addition, a separate xylose-grown culture received a pulse of glucose, and the xylAB transcript abundance was assessed after the pulse. The two sugars were used at similar rates in single-substrate cultures (Fig. 5A), whereas in the dual-substrate culture (Fig. 5B), glucose was utilized somewhat more rapidly than xylose. After the addition of glucose to a xylose culture (Fig. 5C), pentose utilization was arrested, and it then resumed following a 3-h lag period, although slightly less rapidly compared to glucose.

FIG. 5.

Carbohydrate utilization by T. ethanolicus. Cells were grown with xylose (•) or glucose (▪) (A), with both sugars in the dual-substrate culture (B), or with xylose with a glucose pulse (arrow) introduced (C). Optical densities are indicated by dashed lines in panels B and C and by a dashed line for the glucose culture and a dotted line for the xylose culture in panel A.

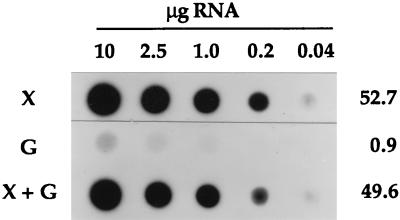

For dot blot analysis, total RNA was isolated from cells grown with various sugar substrates and hybridized to a 412-bp xylA fragment. The resulting autoradiograph (Fig. 6) demonstrated the abundance of xylAB mRNA when xylose was present in the growth medium regardless of the presence of glucose, but this transcript was barely detectable in the absence of xylose. The same results were obtained when mannitol was substituted for glucose; i.e., virtually no xylAB mRNA was detected with mannitol as a sole energy source, whereas in a dual-substrate culture (xylose plus mannitol), the presence of mannitol did not cause repression of xylAB transcription (data not shown). Determination of relative signal intensities showed a 50-fold reduction of the xylAB transcription in the absence of xylose. Quantification of the signals obtained from the xylose culture that received a glucose pulse indicated that the postpulse xylAB mRNA level was similar to that of the prepulse sample (data not shown). The xylAB transcript levels were accompanied by correspondingly high or low activities of xylose isomerase and xylulokinase, depending on the presence of xylose (Table 1).

FIG. 6.

RNA dot blot analysis. Total RNA was isolated from logarithmically growing cells cultivated with different sugar substrates. Aliquots (1.5 μl) of serial dilutions were applied to a membrane and hybridized to the radiolabelled 412-bp fragment from xylA. The resulting autoradiograph was analyzed by using a PhosphorImager to determine relative signal intensities. Their averages are shown on the right. X, 0.4% xylose; G, 0.4% glucose; X + G, xylose and glucose, each at 0.2%.

TABLE 1.

Xylose isomerase and xylulose kinase activities of T. ethanolicus 39E grown with various carbohydrates

| Carbohydrate(s) | Activity (nmol/min/mg of protein)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Xylose isomerase | Xylulose kinase | |

| Xylose | 200 | 497 |

| Glucose | NDa | ND |

| Xylose + glucose | 199 | 492 |

ND, not detected.

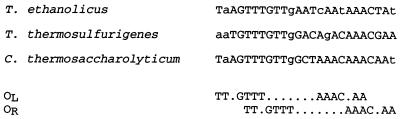

Potential cis-acting regulatory sequences.

Since the expression of the xylAB operon in T. ethanolicus appeared to be repressed in the absence and induced in the presence of xylose, we searched for DNA sequences that could function as cis-acting elements for an induction-repression regulatory mechanism. An inverted repeat was identified 3 nucleotides downstream from the T. ethanolicus xylAB transcription initiation site (Fig. 4B and 7). This sequence matched the xylAB operator sequences (xylOs), comprising two tandem overlapping palindromes, xylOL and xylOR (8), that were observed in several Bacillus species (20, 44, 47), L. pentosus (33), and Staphylococcus xylosus (53). We also searched for homologous sequences in other xylose-utilizing thermoanaerobes and found them in Thermoanaerobacterium thermosulfurogenes (28) and Clostridium thermosaccharolyticum (38), 28 and 39 nucleotides upstream from the 5′ ends of their xylA ORFs, respectively. The alignment of these two palindromes with the putative T. ethanolicus xylO revealed a marked sequence conservation (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Alignment of putative xylO sequences from three anaerobic thermophilic bacteria. The consensus sequences derived from xylOL and xylOR in gram-positive bacteria, as defined by Dahl et al. (8), are shown on the bottom. Nucleotides deviating from the consensus are in lowercase letters.

DISCUSSION

The unexpected finding that C. thermocellum JW20 is contaminated with T. ethanolicus was based on the xylAB DNA sequence analysis in this report. Our concomitant study (16) ruled out the capacity of strain JW20 to metabolize xylose and confirmed its existence as a coculture. Furthermore, as presented here, we were unable to detect either xylA or xylB in genomic DNA from the purified C. thermocellum JW20 (data not shown).

To our knowledge, this is the first report of an xylB sequence from a thermophilic anaerobic bacterium. ORFs homologous to xylB were found downstream from xylA in Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum (29) and C. thermosaccharolyticum (38), but the sequence information is not yet available. We showed that T. ethanolicus XylB is similarly related to xylulokinases from both gram-negative and gram-positive organisms and, importantly, to other members of the carbohydrate kinase family as well (42). Further studies are needed to identify amino acid residues and interactions conferring thermostability and thermophilicity to the T. ethanolicus XylB protein, as well as residues in its catalytic site(s).

The organization of the T. ethanolicus xylA and xylB genes into an operon is common for most bacterial species for which xylose utilization genes have been studied. However, processing of the bicistronic xylAB transcript, as we demonstrated for T. ethanolicus, has been noted only for K. pneumoniae (17) and L. pentosus (32) so far. While no Northern analysis results were shown in the K. pneumoniae study, processing of T. ethanolicus xylAB mRNA appears to be different from that seen in L. pentosus. Namely, both T. ethanolicus 1.5-kb mRNA moieties have approximately the same half-life as the intact xylAB transcript, whereas in L. pentosus neither the xylAB (31) nor the xylB (32) transcript was detected during exponential growth.

No inverted repeats capable of forming potentially stable hairpins were found within the sequence overlapping the termini of the xylA and xylB ORFs in T. ethanolicus (data not shown), as compared to the inverted repeat present in the L. pentosus xylAB intercistronic region (32). Thus, if there is a differential xylAB transcript regulation mechanism in T. ethanolicus, it differs from that proposed for L. pentosus xylAB (31, 32). Since none of the T. ethanolicus xylAB mRNA cleavage sites matches the cleavage consensus established for RNase E (14), it is likely that the processing of the xylAB transcript in T. ethanolicus involves a different type of endonuclease.

We established that the xylAB mRNA 5′ end lies 169 nucleotides upstream from the previously assigned promoter region (10). The untranslated leader sequence of the xylAB transcript is considerably longer than those predicted for other T. ethanolicus genes (5, 37, 41) and many other bacteria (23, 24). At present, it is not clear whether this long sequence has any functional significance. For instance, no palindromic sequences that could provide increased mRNA stability (55) are found in this upstream region.

Our results clearly demonstrate that the regulation of xylAB expression in T. ethanolicus 39E is mediated at the transcriptional level. The observation that the T. ethanolicus xylAB mRNA was abundant when xylose was available indicated that regulation of xylose utilization in T. ethanolicus could be mediated by one of the following mechanisms: (i) negative regulation by a transcriptional repressor, as observed in other xylose-utilizing gram-positive bacteria (21, 33, 44, 53); (ii) positive regulation by a transactivator, as described for E. coli (54) and Salmonella typhimurium (51); or (iii) dual regulation, i.e., suppresion of transcription in the absence and stimulation in the presence of xylose, possibly mediated by a protein analogous to E. coli AraC (40). The strong homology of the palindromic sequences found in the vicinity of the T. ethanolicus xylAB +1 site to the consensus sequences of xylOs from organisms in which xylose catabolism is negatively regulated (Fig. 7) suggests that xylose utilization in T. ethanolicus is mediated by an inducer-repressor mechanism. The same inference could be made for two other related thermophilic anaerobes; the total numbers of deviations from the consensus sequences for OL and OR (5, 4, and 3 for T. ethanolicus, T. thermosulfurigenes, and C. thermosaccharolyticum, respectively) are comparable to those seen in Bacillus spp., L. pentosus, and S. xylosus, from which the consensus sequences were defined (8).

In gram-positive bacteria in which the repressor protein, XylR, binds xylOs in the absence of xylose, thus inhibiting the transcription of xylAB, xylR is located immediately upstream from xylA (25, 33, 44, 48, 52). Since the sequence upstream from the T. ethanolicus xylAB operon contains only the putative K+ uptake genes, we analyzed the 367-bp pXI-10 fragment flanking the xylB ORF for homology to xylR, but this sequence showed no similarity to known xylRs (data not shown). Furthermore, the ORFs identified within the 4-kb genomic locus contiguous to the pXI-10 3′ terminus had no homology with known XylR repressors (15). The observation that a putative xylR resides in front of the xylanase gene, xynA, in two other obligately anaerobic thermophilic bacteria, a Caldicellulosiruptor sp. (13) and Anaerocellum thermophilum (61), suggests the possibility that the T. ethanolicus xylR gene is situated in the vicinity of genes mediating catabolism of xylans and/or xylooligomers, but this requires further study.

In gram-positive bacteria in which carbon metabolism was studied at the molecular level, glucose was shown to inhibit transcription of xylAB by catabolite repression (45). In E. coli and S. typhimurium glucose also exerts an inhibitory effect on expression of xylose utilization genes (9, 51). In contrast, we demonstrated that the xylAB transcription in T. ethanolicus is not repressed by glucose and, to our knowledge, this is the first report of such a phenomenon. A temporary inhibition of xylose catabolism by a glucose pulse observed in our study (Fig. 5C) might be related to a competition between the two sugars for xylose isomerase or to an inhibition of xylose transport by glucose. Several other anaerobic bacteria were shown to coutilize these two sugars (56–58), but none of these studies examined aspects related to molecular regulation. In summary, our study provides a foundation for understanding molecular mechanisms orchestrating carbohydrate utilization in T. ethanolicus. Given the recent successful genetic transformations of two other related species (11, 36), one can expect substantially more insight to be developed in this field before long.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The technical assistance of Chris Jones is appreciated. We are indebted to Wolfgang Hillen for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful comments.

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture under agreement 95-37500-1793.

Footnotes

Published with the approval of the Director of the Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station as journal article no. 98-07-12.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F A, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey R W. The reaction of pentose with anthrone. Biochem J. 1958;68:669–672. doi: 10.1042/bj0680669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhosale S H, Rao M B, Deshpande V V. Molecular and industrial aspects of glucose isomerase. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:280–300. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.280-300.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burdette D S, Vieille C, Zeikus J G. Cloning and expression of the gene encoding the Thermoanaerobacter ethanolicus 39E secondary-alcohol dehydrogenase and biochemical characterization of the enzyme. Biochem J. 1996;316:115–122. doi: 10.1042/bj3160115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charrier V, Buckley E, Parsonage D, Galinier A, Darbon E, Jaquinod M, Forest E, Deutscher J, Claiborne A. Cloning and sequencing of two enterococcal glpK genes and regulation of the encoded glycerol kinases by phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent, phosphotransferase system-catalyzed phosphorylation of a single histidyl residue. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14166–14174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chin D T, Goff S A, Webster T, Smith T, Goldberg A L. Sequence of the lon gene in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:11718–11728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahl M K, Degenkolb J, Hillen W. Transcription of the xyl operon is controlled in Bacillus subtilis by tandem overlapping operators spaced by four base-pairs. J Mol Biol. 1994;243:413–424. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.David J D, Weismeyer H. Control of xylose metabolism in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;201:497–499. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(70)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dekker K, Yamagata H, Sakaguchi K, Udaka S. Xylose (glucose) isomerase gene from the thermophilic Clostridium thermohydrosulfuricum; cloning, sequencing, and expression in Escherichia coli. Agric Biol Chem. 1991;55:221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demain A L, Klapatch T R, Jung K H, Lynd L R. Recombinant DNA technology in development of an economical conversion of waste to liquid fuel. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;782:402–412. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dische Z. Color reactions of pentoses. In: Whistler R L, Wolfram M L, editors. Methods in carbohydrate chemistry. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1962. pp. 483–488. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dwivedi P P, Gibbs M D, Saul D J, Bergquist P L. Cloning, sequencing and overexpression in Escherichia coli of a xylanase gene, xynA, from the thermophilic bacterium Rt8B.4 genus Caldicellulosiruptor. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;45:86–93. doi: 10.1007/s002530050653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehretsmann C P, Carpousis A J, Krisch H M. Specificity of Escherichia coli endoribonuclease RNase E: in vivo and in vitro analysis of mutants in a bacteriophage T4 mRNA processing site. Genes Dev. 1992;6:149–159. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erbeznik, M., K. A. Dawson, C. R. Jones, and H. J. Strobel. 1997. Unpublished data.

- 16.Erbeznik M, Jones C R, Dawson K A, Strobel H J. Clostridium thermocellum JW20 (ATCC 31549) is a coculture with Thermoanaerobacter ethanolicus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2949–2951. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2949-2951.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldman S D, Sahm H, Sprenger G A. Cloning and expression of the genes for xylose isomerase and xylulokinase from Klebsiella pneumoniae 1033 in Escherichia coli K12. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;234:201–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00283840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freier D, Mothershed C P, Wiegel J. Characterization of Clostridium thermocellum JW20. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:204–211. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.1.204-211.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujita Y, Fujita T, Miwa Y, Nihashi J, Aratani Y. Organization and transcription of the gluconate operon, gnt, of Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13744–13753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gärtner D, Degenkolb J, Rippberger J, Allmansberger R, Hillen W. Regulation of Bacillus subtilis W23 xylose utilization operon: interaction of Xyl repressor with xyl operator and the inducer xylose. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;232:415–422. doi: 10.1007/BF00266245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gärtner D, Geissendörfer M, Hillen W. Expression of the Bacillus subtilis xyl operon is repressed at the level of transcription and is induced by xylose. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3102–3109. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3102-3109.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottschalk G. Bacterial metabolism. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graves M C, Rabinowitz J C. In vivo and in vitro transcription of the Clostridium pasteurianum ferredoxin gene. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:11409–11415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harley C B, Reynolds R P. Analysis of E. coli promoter sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:2343–2361. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.5.2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreuzer P, Gärtner D, Allmansberger R, Hillen W. Identification and sequence analysis of the Bacillus subtilis W23 xylR gene and xyl operator. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3840–3845. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3840-3845.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawlis V B, Dennis M S, Chen E Y, Smith D H, Henner D J. Cloning and sequencing of the xylose isomerase and xylulose kinase of Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:15–21. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.1.15-21.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawyer F C, Stoffel S, Saiki R K, Myambo K, Drummond R, Gelfand D H. Isolation, characterization, and expression in Escherichia coli of the DNA polymerase gene from Thermus aquaticus. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:6427–6437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee C, Bagdasarian M, Meng M, Zeikus J G. Catalytic mechanism of xylose (glucose) isomerase from Clostridium thermosulfurogenes. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:19082–19090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee C, Ramesh M V, Zeikus J G. Cloning, sequencing and biochemical characterization of xylose isomerase from Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum strain B6A-RI. J Gen Microbiol. 1994;139:1227–1234. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-6-1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liao W X, Earnest L, Kok S L, Jeyaseelan K. Organization of the xyl genes in a thermophilic Bacillus species. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1996;39:1049–1062. doi: 10.1080/15216549600201212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lokman B C, Heerikhuisen M, Leer R J, van den Broek A, Borsboom Y, Chaillou S, Postma P W, Pouwels P H. Regulation of expression of the Lactobacillus pentosus xylAB operon. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5391–5397. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5391-5397.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lokman B C, Leer R J, van Sorge R, Pouwels P H. Promotor analysis and transcriptional regulation of Lactobacillus pentosus genes involved in xylose catabolism. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;245:117–125. doi: 10.1007/BF00279757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lokman B C, van Santen P, Verdoes J C, Krüse J, Leer R J, Posno M, Pouwels P H. Organization and characterization of three genes involved in d-xylose catabolism in Lactobacillus pentosus. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;230:161–169. doi: 10.1007/BF00290664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynd L R. Production of ethanol from lignocellulosic materials using thermophilic bacteria: critical evaluation of potential and review. Adv Biochem Eng. 1989;38:1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mai V, Lorenz W W, Wiegel J. Transformation of Thermoanaerobacterium sp. strain JW/SL-YS485 with plasmid pIKM1 conferring kanamycin resistance. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;148:163–167. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathupala S P, Lowe S E, Podkovyrov S M, Zeikus J G. Sequencing of the amylopullulanase (apu) gene of Thermoanaerobacter ethanolicus 39E, and identification of the active site by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16332–16344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meaden P G, Adose-Opoku J, Reizer J, Reizer A, Lanceman Y A, Martin M F, Mitchell W J. The xylose isomerase-encoding gene (xylA) of Clostridium thermosaccharolyticum: cloning, sequencing and phylogeny of XylA enzymes. Gene. 1994;141:97–101. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moran C P, Jr, Lang N, LeGrice S F J, Lee G, Stephens M, Sonenshein A L, Pero J, Losick R. Nucleotide sequences that signal the initiation of transcription and translation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;186:339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00729452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogden S, Hagerty D, Stoner C M, Kolodrubetz D, Schleif R. The Escherichia colil-arabinose operon: binding sites of the regulatory protein and a mechanism of positive and negative regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:3346–3350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Podkovyrov S M, Zeikus J G. Structure of the gene encoding cyclomaltodextrinase from Clostridium thermohydrosulfuricum 39E and characterization of the enzyme purified from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5400–5405. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5400-5405.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reizer A, Deutscher J, Saier M H, Jr, Reizer J. Analysis of the gluconate (gnt) operon of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1081–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Russell J B, Baldwin R L. Substrate preferences in rumen bacteria: evidence of catabolite regulatory mechanisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;36:319–329. doi: 10.1128/aem.36.2.319-329.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rygus T, Scheler A, Allmansberger R, Hillen W. Molecular cloning, structure, promoters and regulatory elements for transcription of the Bacillus megaterium encoded regulon for xylose utilization. Arch Microbiol. 1991;155:535–542. doi: 10.1007/BF00245346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saier M H, Jr, Chauvaux S, Cook G M, Deutscher J, Paulsen I T, Reizer J, Ye J-J. Catabolite repression and inducer control in Gram-positive bacteria. Microbiology. 1996;142:217–230. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-2-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scheler A, Hillen W. Regulation of xylose utilization in Bacillus licheniformis: Xyl-repressor-xyl-operator interaction studied by DNA modification and interference. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:505–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scheler A, Rygus T, Allmansberger R, Hillen W. Molecular cloning, structure, promoters and regulatory elements for transcription of the Bacillus licheniformis encoded regulon for xylose utilization. Arch Microbiol. 1991;155:526–534. doi: 10.1007/BF00245345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schlösser A, Hamann A, Bossemeyer D, Schneider E, Baker E P. NAD+ binding to the Escherichia coli K+-uptake protein TrkA and sequence similarity between TrkA and domains of a family of dehydrogenases suggest a role for NAD+ in bacterial transport. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:533–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schlösser A, Kluttig S, Hamann A, Baker E P. Subcloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of trkG, a gene that encodes an integral membrane protein involved in potassium uptake via the Trk system of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3170–3176. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.10.3170-3176.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shamana D K, Sanderson K E. Genetics and regulation of xylose utilization in Salmonella typhimurium LT2. J Bacteriol. 1979;139:71–79. doi: 10.1128/jb.139.1.71-79.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sizemore C, Buchner E, Rygus T, Witke C, Götz F, Hillen W. Organization, promoter analysis and transcriptional regulation of the Staphylococcus xylosus xylose utilization operon. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;277:377–384. doi: 10.1007/BF00273926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sizemore C, Wieland B, Götz F, Hillen W. Regulation of Staphylococcus xylosus xylose utilization genes at the molecular level. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3042–3048. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.9.3042-3048.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Song S, Park C. Organization and regulation of the d-xylose operons in Escherichia coli K-12: XylR acts as a transcriptional activator. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7025–7032. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7025-7032.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stern M J, Ames G F-L, Smith N H, Robinson E C, Higgins C F. Repetitive extragenic palindromic sequences: a major component of the bacterial genome. Cell. 1984;37:1015–1026. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strobel H J. Pentose utilization and transport by the ruminal bacterium Prevotella ruminicolla. Arch Microbiol. 1994;159:465–471. doi: 10.1007/BF00288595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strobel H J, Dawson K A. Xylose and arabinose utilization by the ruminal bacterium Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;113:291–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thurston B, Dawson K A, Strobel H J. Pentose utilization by the ruminal bacterium Ruminococcus albus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1087–1092. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.4.1087-1092.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wiegel J, Mothershed C P, Puls J. Differences in xylan degradation by various noncellulolytic thermophilic anaerobes and Clostridium thermocellum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:656–659. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.3.656-659.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilhelm M, Hollenberg C P. Nucleotide sequence of the Bacillus subtilis xylose isomerase gene: extensive homology between the Bacillus and E. coli enzyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:5717–5722. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.15.5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zverlov, V. V., K. Bronnenmeier, and G. A. Velikodvorskaya. 1996. Unpublished data.