Abstract

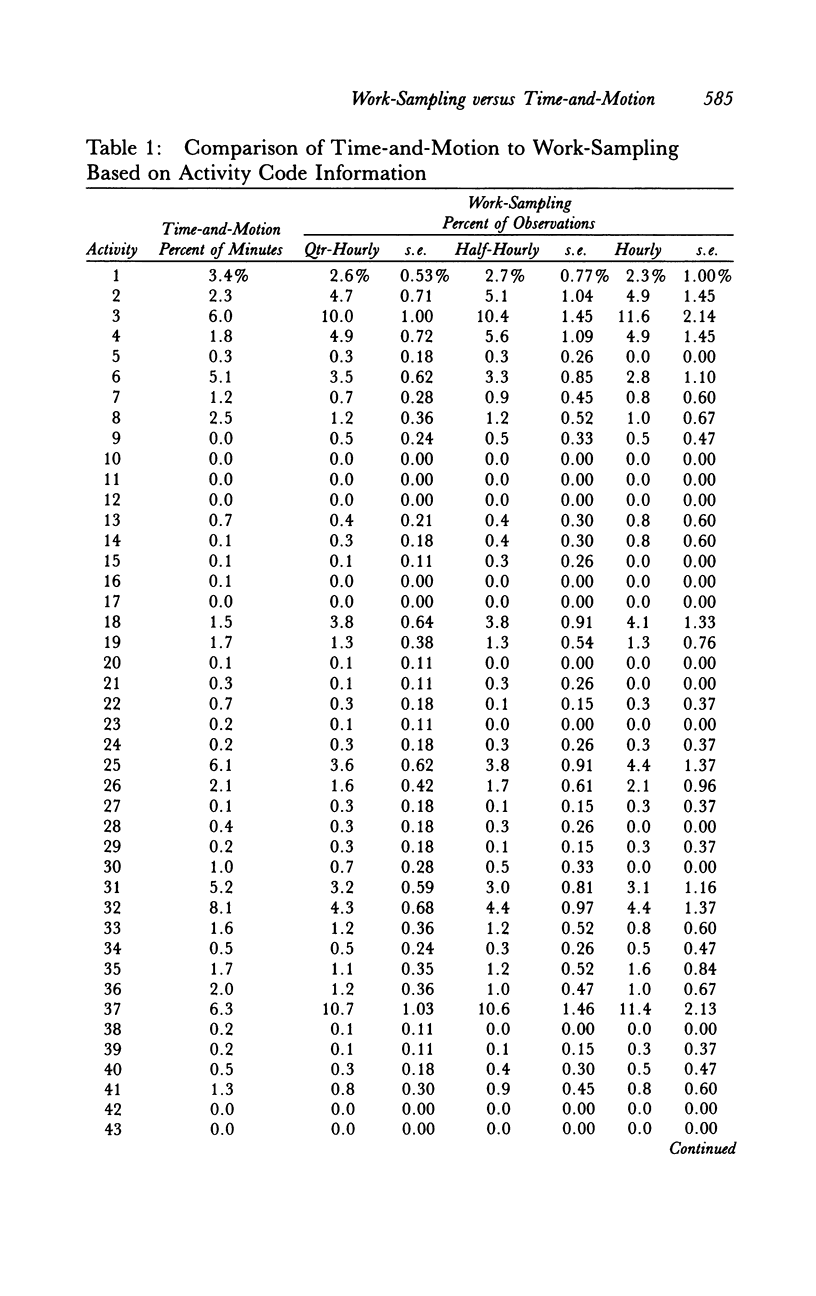

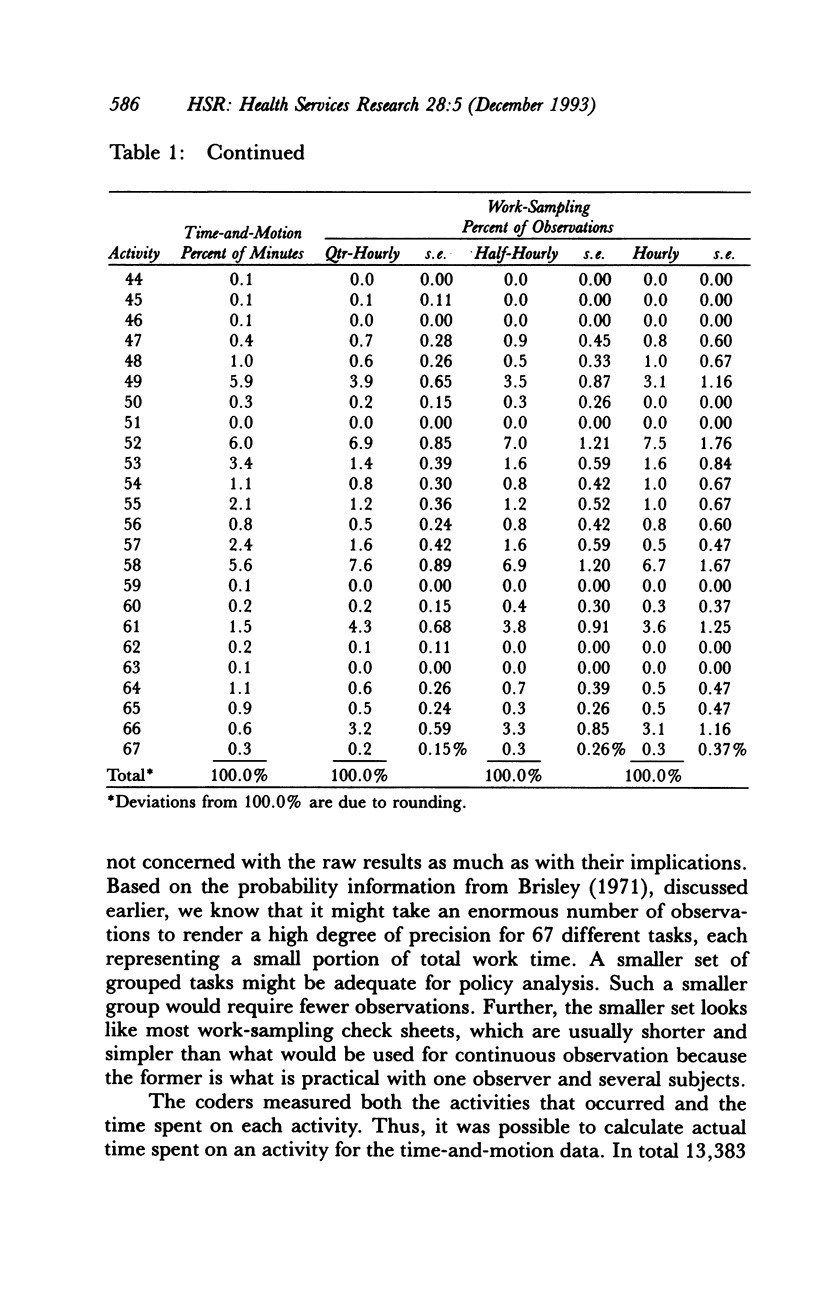

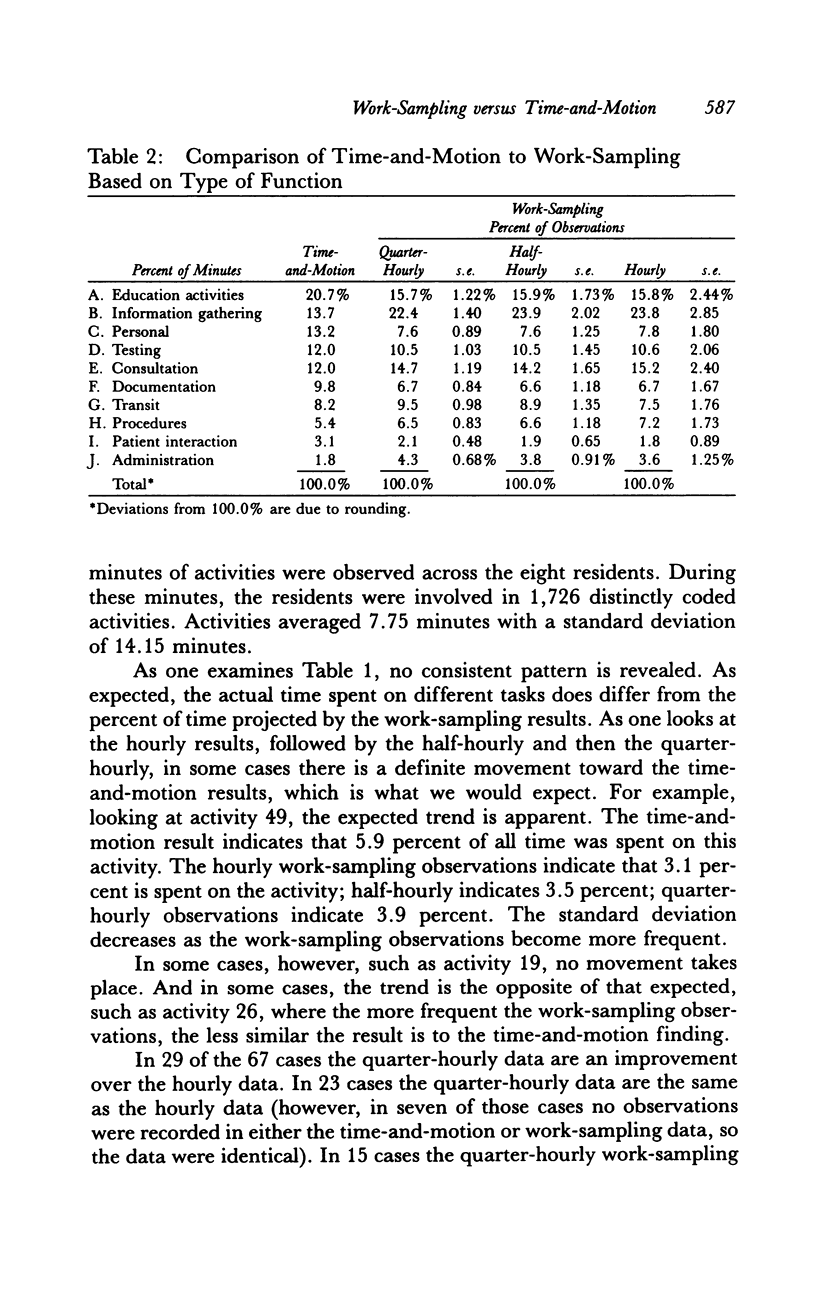

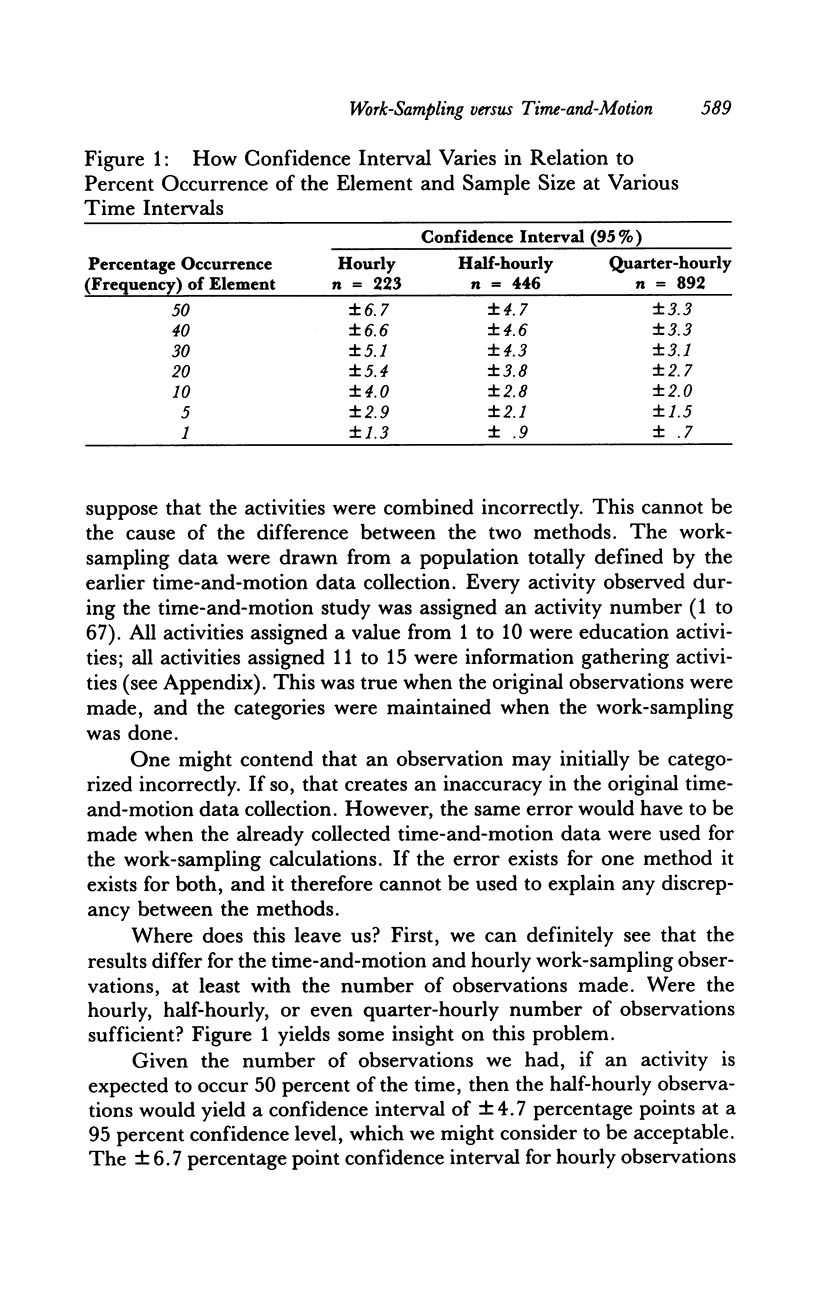

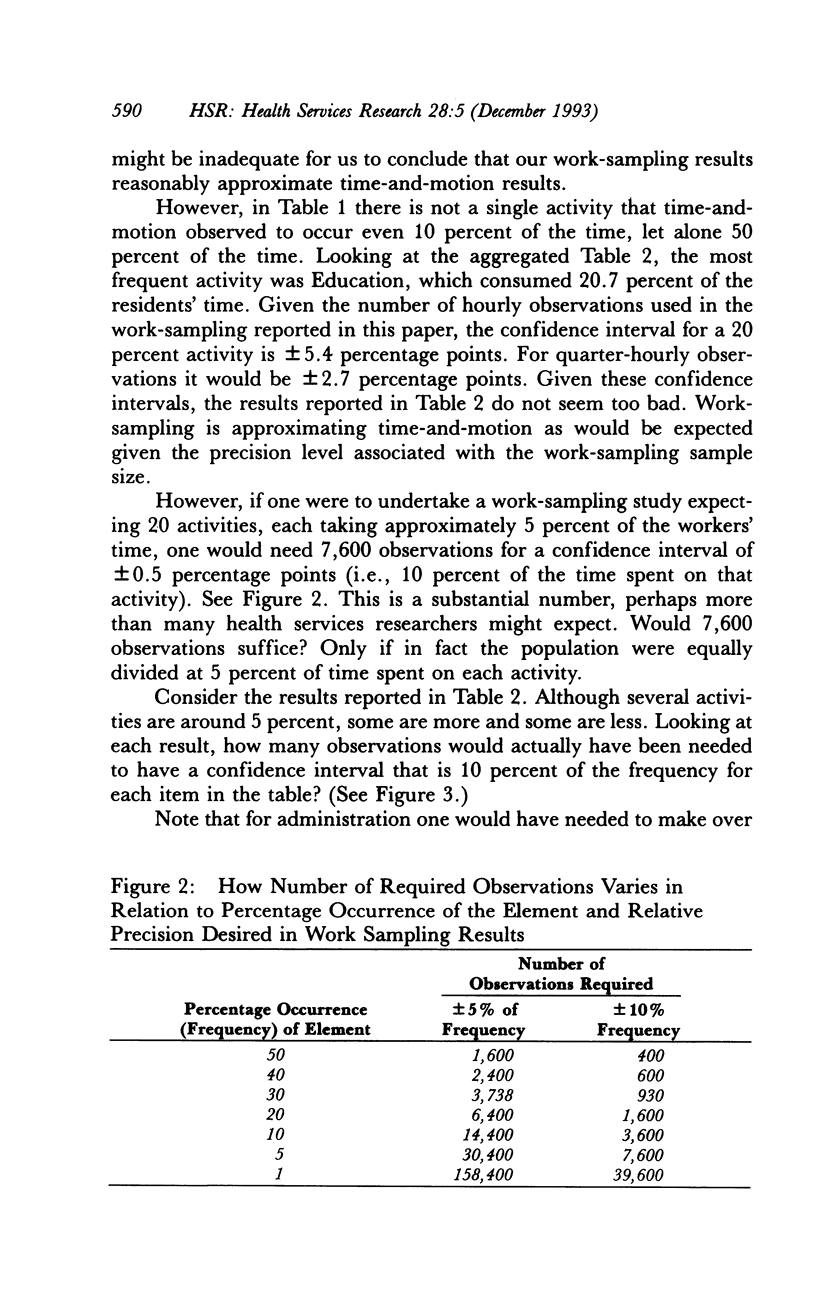

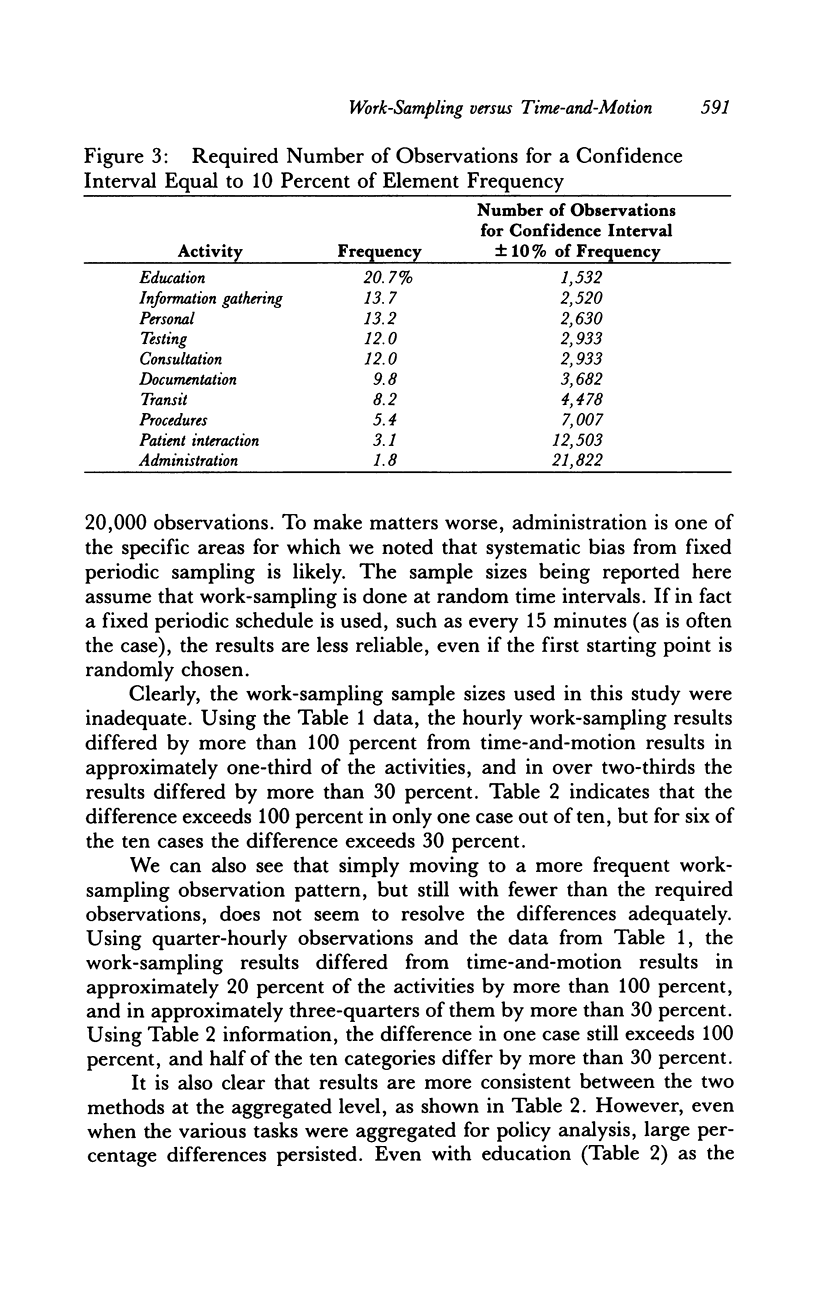

OBJECTIVE. This study compares results and illustrates trade-offs between work-sampling and time-and-motion methodologies. DATA SOURCES. Data are from time-and-motion measurements of a sample of medical residents in two large urban hospitals. STUDY DESIGN. The study contrasts the precision of work-sampling and time-and-motion techniques using data actually collected using the time-and-motion approach. That data set was used to generate a simulated set of work-sampling data points. DATA COLLECTION/EXTRACTION METHODS. Trained observers followed residents during their 24-hour day and recorded the start and end time of each activity performed by the resident. The activities were coded and then grouped into ten major categories. Work-sampling data were derived from the raw time-and-motion data for hourly, half-hourly, and quarter-hourly observations. PRINCIPAL FINDINGS. The actual time spent on different tasks as assessed by the time-and-motion analysis differed from the percent of time projected by work-sampling. The work-sampling results differed by 20 percent or more of the estimated value for eight of the ten activities. As expected, the standard deviation decreases as work-sampling observations become more frequent. CONCLUSIONS. Findings indicate that the work-sampling approach, as commonly employed, may not provide an acceptably precise approximation of the result that would be obtained by time-and-motion observations.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ABDELLAH F. G., LEVINE E. Work sampling applied to the study of nursing personnel. Nurs Res. 1954 Jun;3(1):11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson W. M. Measuring pharmacist time use: a note on the use of fixed-interval work sampling. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1978 Oct;35(10):1241–1243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenech M. A., Payton O., Hill J., Shukla R. K. Utilization of physical therapy personnel in one hospital. A work sampling study. Phys Ther. 1983 Jul;63(7):1108–1112. doi: 10.1093/ptj/63.7.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao W. C., Braun P., Becker E. R., Thomas S. R. The Resource-Based Relative Value Scale. Toward the development of an alternative physician payment system. JAMA. 1987 Aug 14;258(6):799–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knickman J. R., Lipkin M., Jr, Finkler S. A., Thompson W. G., Kiel J. The potential for using non-physicians to compensate for the reduced availability of residents. Acad Med. 1992 Jul;67(7):429–438. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199207000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptak G. S., Super D. M., Baker N., Roghmann K. J. An analysis of waiting times in a pediatric emergency department. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1985 Apr;24(4):202–209. doi: 10.1177/000992288502400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie N., Rank B., Parenti C., Woolley T., Snoke W. How do house officers spend their nights? A time study of internal medicine house staff on call. N Engl J Med. 1989 Jun 22;320(25):1673–1677. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198906223202507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rascati K. L., Kimberlin C. L., McCormick W. C. Work measurement in pharmacy research. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1986 Oct;43(10):2445–2452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid R. A. A work sampling study of midlevel health professionals in a rural medical clinic. Med Care. 1975 Mar;13(3):241–249. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]