Abstract

AIM

To investigate the differences in retinal refraction difference values (RDVs) of adult patients with myopic anisometropia compared with those without myopic anisometropia, and to investigate the relationship between ocular biometric measurements and relative peripheral refraction.

METHODS

This clinical observation study included 130 patients with myopia (-0.25 to -10.00 D) between October 2022 and January 2023 aged between 18 and 40y. The patients were divided into anisometropia (n=63; difference in binocular anisometropia ≥1.00 D) and non-anisometropia (n=67; difference in binocular anisometropia <1.00 D) groups accordingly. Ocular biometric measurements were performed by optical biometrics and corneal topography to assess the steep keratometry (Ks), flap keratometry (Kf), axial length (AL), corneal astigmatism (CYL; Ks-Kf), surface regularity index (SRI), surface asymmetry index (SAI), and central corneal thickness (CCT). The RDV was measured at five retinal areas from the fovea to 53 degrees (RDV-0-10, RDV-10-20, RDV-20-30, RDV-30-40, and RDV-40-53), the total RDV (TRDV) of 53 degrees, and four regions, including RDV-superior, RDV-inferior, RDV-temporal, and RDV-nasal. An analysis of Spearman correlation was carried out to examine the correlation between RDV and the spherical equivalent (SE) and ocular biological parameters.

RESULTS

Within RDV-20-53, both groups showed relative hyperopic defocus, and the increase in RDV corresponds to the increase in eccentricity. In the myopic anisometropia group, the TRDV, RDV-20-53, RDV-superior, and more myopic eyes had significantly higher RDV-temporal values than less myopic eyes. (P<0.05). In the non-anisometropia group, there was no significant difference in the RDV between the more and less myopic eyes at different eccentricities (P>0.05). There was a negative correlation between SE and TRDV (r=-0.205, P=0.001), RDV-20-53 (r=-0.281, -0.183, -0.176, P<0.05), RDV-superior (r=-0.251, P<0.001), and RDV-temporal (r=-0.230, P<0.001), a negative correlation between CYL and RDV-10-30 (r=-0.147, -0.180, P<0.05), and a negative correlation between SRI and RDV-0-20 (r=-0.190, -0.170, P<0.05). AL had a positive correlation with RDV-20-30 (r=0.164, P=0.008) and RDV-temporal (r=0.160, P=0.010).

CONCLUSION

More myopic eyes in patients with myopic anisometropia show more peripheral hyperopic defocus. Diopter and corneal morphology may affect peripheral retinal defocus.

Keywords: myopia, anisometropia, peripheral refraction, multispectral refractive topography, axial length

INTRODUCTION

Myopic anisometropia refers to the difference (≥1 D) in the equivalent spherical diopter between the two eyes of patients with myopia[1]. Studies have shown that the frequency and severity of anisometropia escalate with aging and the presence of myopia[2]–[3], and anisometropia serves as a biomarker for the decreased level of optically controlled ocular growth[4]. Anisometropia can lead to a difference in the size of binocular retinal imaging, leading to binocular visual dysfunction such as visual fatigue, amblyopia, and stereopsis dysfunction[5]–[6]. At present, it is believed that myopic anisometropia has differences based on eye structure and binocular development[7].

In recent decades, peripheral refraction has become a popular research topic in myopia prevention and control. Animal experiments and clinical studies suggest that the refractive state in the peripheral retina is strongly associated with the development of myopia[8]–[9]. Multispectral refractive topography (MRT) can quantify the peripheral defocus value of the retina within 53° by successively collecting fundus images with different wavelengths of single spectral light and combining them using a computer algorithm. This method has been found to be accurate, reliable, and reproducible[10]–[11].

However, few studies have demonstrated differences in refractive status at different retinal eccentricities between more and less myopic eyes in patients with myopic anisometropia. Therefore, the aim of this research was to 1) examine the binocular difference in peripheral refraction of the retina in adult patients with myopic anisometropia with different eccentricity ranges, 2) to explore the correlation between common ocular biometric measurements and peripheral retinal defocus. Our findings may provide a source of reference and theoretical foundation for the selection of personalized optical correction methods for myopic anisometropia and aid in the regulation and management of myopia in teenagers in clinic settings.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Ethical Approval

This study meets the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethics approval from the Ethics Committee of the In eye Hospital of Chengdu University of TCM (No.2022yh-022). All the participants signed written informed consent.

General Information

In this cross-sectional clinical study we collected the information of 130 patients with myopia who were seen at In eye Hospital of Chengdu University of TCM between October 2022 and January 2023. The criteria for inclusion were as follows: 1) aged between 18 and 40 years old; 2) binocular myopia; 3) degree of cylindrical mirror ≤3.00 D; 4) stopped using soft contact lenses for at least 2wk and rigid gas breathable contact lenses for 4wk before examination; 5) no history of refractive surgery and corneal diseases. The criteria for exclusion were as follows: 1) participants with eye or major systemic diseases; 2) corrected distance visual acuity <20/25.

Anisometropia is defined as a refractive error difference of at least 1.0 D between the two eyes. Participants were divided into anisometropia and non-anisometropia groups accordingly. In each group, eyes with higher myopic refractive error are referred to as “more myopic eyes” and eyes with lower myopic refractive error are referred to as “less myopic eyes”.

Examinations

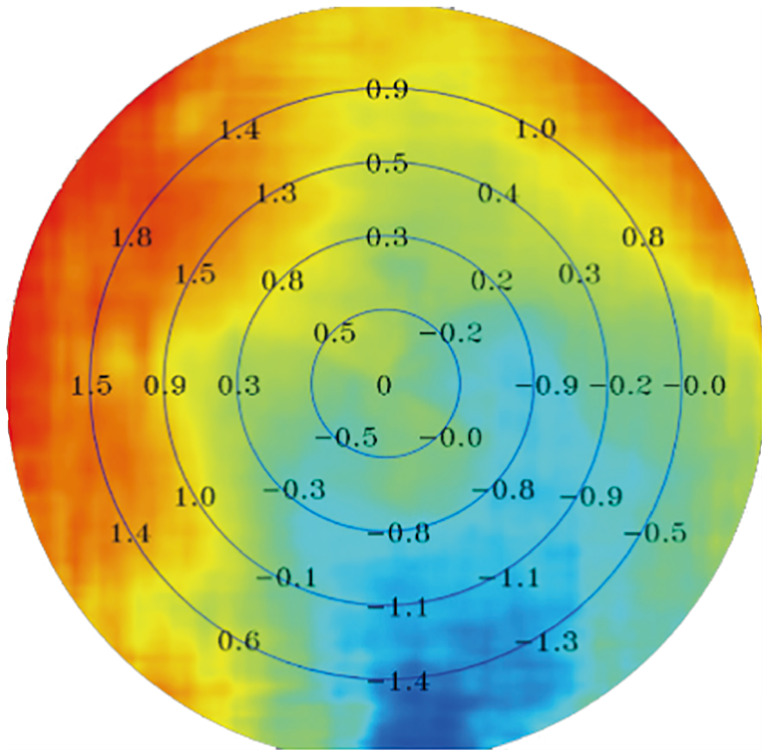

Each patient underwent visual acuity, intraocular pressure, and the anterior segment of the eye examination. The central corneal thickness (CCT) and axial length (AL) were measured by optical biometry (LS900, Haag-Streit AG, Switzerland). Corneal topography (TMS-4, Tomey, Japan) was used to evaluate the binocular topography, and the surface asymmetry index (SAI), surface regularity index (SRI), steep keratometry (Ks), flap keratometry (Kf), and corneal astigmatism (CYL=Ks-Kf) were recorded. The retinal refraction difference value (RDV) was measured using multispectral refractive topography (MRT, MSI C2000, ShengDa TongZe, ShenZhen, China) at five retinal eccentricities (Figures 1 and 2). From the fovea into 53 degrees (RDV-0-10, RDV-10-20, RDV-20-30, RDV-30-40 and RDV-40-53), the retinal total refraction difference value (TRDV) of 53 degrees, and four regions, including RDV-S (RDV-Superior), RDV-I (RDV-Inferior), RDV-T (RDV-Temporal), and RDV-N (RDV-Nasal). Positive RDV values indicate hyperopic defocus, while negative values indicate myopic defocus. All examinations were performed during the 8:30 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. time period to avoid diurnal variations in measurements. Examination of spherical equivalent (SE) using cycloplegic refraction. In this study, the refractive power of the participants was measured through computerized optometry, retinoscopy, and subjective optometry. The 0.5% compound tropicamide was utilized for cycloplegias. The SE was calculated as SE=diopter sphere (DS) + 1/2 diopter cylinder (DC).

Figure 1. Retinal refraction difference values (RDVs).

Results of multispectral refractive tomography: The innermost circle corresponds to RDV-0-10; the first annular region corresponds to RDV-10-20; the second annular corresponds to RDV-20-30; the third annular region corresponds to RDV-30-40; and the fourth annular corresponds to RDV-40-53. Positive RDVs indicate hyperopic defocus, while negative values indicate myopic defocus.

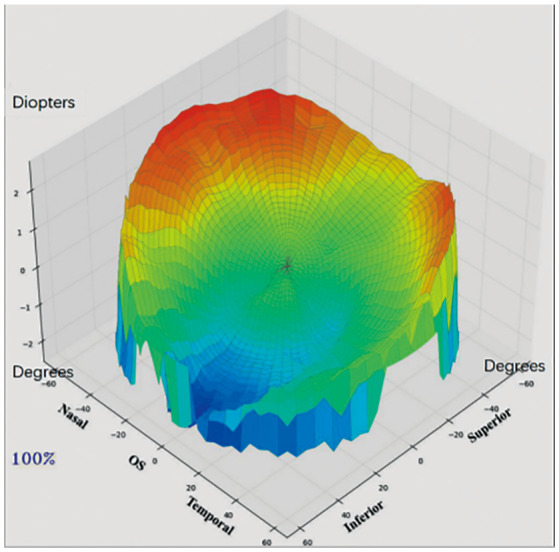

Figure 2. Three-dimensional image of a left eye showing the relative fraction status of the retina.

The red area represents hyperopia defocus and the blue area represents myopia defocus.

Sample Size

In this study, the sample size was calculated using power analysis. We assumed a moderate correlation (Spearman's r=0.3) between the correlation indicators, a power (1-β) of 90%, and a significance level (α) of 0.05. The minimum sample size was calculated as 112 subjects (anisometropia group, 56; non-anisometropia group, 56).

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 23.0 (version 23.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Data were analyzed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. For data that were not normally distributed, the Mann-Whitney U test was employed to evaluate age, SE, and AL between the anisometropia group and non-anisometropia group, and expressed as median (25th to 75th quartile). If the data were normally distributed, the paired t-test was used to compare binocular baseline and retinal peripheral defocus data between groups. Otherwise, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was employed. The results are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD). Spearman's correlation analysis was utilized to examine the relationships between AL, CCT, Ks, Kf, CYL, SRI, SAI, and RDV. The eyes of all participants were included in the correlation analysis. A P-value of <0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline Parameters Between the Two Groups

In this study, a total of 145 participants were enrolled, of which 15 patients had unsatisfactory images. Hence, 130 participants were eventually enrolled in the study. The anisometropia group included 63 participants (126 eyes), and the non-anisometropia group included 67 participants (134 eyes). The median age in the anisometropia group was 27 (18 to 40)y and it was 26 (18 to 40)y in the non-anisometropia group. The median SE and AL in the anisometropia group was -4.09 (-10.00 to -0.25) D and 25.31 (22.55 to 28.34) mm, and it was -4.00 (-6.75 to -1.13) D and 25.23 (22.49 to 27.49) mm in the non-anisometropia group (Table 1).

Table 1. The baseline parameters between the anisometropia group and non-anisometropia group.

| Parameters | Total (n=130) | Anisometropia group (n=63, 48%) | Non-anisometropia group (n=67, 52%) | Z | P |

| Gender (M/F) | 64 (49%)/66 (51%) | 30 (48%)/33 (52%) | 34 (51%)/33 (49%) | - | - |

| Age (y) | 27 (18 to 40) | 27 (18 to 40) | 26 (18 to 40) | -0.124 | 0.901 |

| SE (D) | -4.04 (-10.00 to -0.25) | -4.09 (-10.00 to -0.25) | -4.00 (-6.75 to -1.13) | -0.639 | 0.523 |

| AL (mm) | 25.27 (22.49 to 28.34) | 25.31 (22.55 to 28.34) | 25.23 (22.49 to 27.49) | -0.599 | 0.549 |

Data were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. M: Male; F: Female; SE: Spherical equivalent; AL: Axial length.

Binocular Refraction and Ocular Biometric Parameters at Baseline

In the myopic anisometropia group, the differences in SE and AL in the 63 patients' eyes were statistically significant (Z=-6.906, t=13.072; P<0.001; Table 2), and the SE and AL in more myopic eyes were greater than those in less myopic eyes. There was no significant difference in Ks, Kf, CCT, CYL, SRI, and SAI between the more and less myopic eyes (P>0.05; Table 2). The difference in binocular diopters of the myopic anisometropia group was 2.29±1.25 D. In the non-anisometropia group, the differences in SE and AL in the 67 patients' eyes were also statistically significant (t=-11.848, 3.516; P<0.001; Table 2), and the SE and AL in the more myopic eyes were greater than those in the less myopic eyes. Additionally, there was no significant difference in Ks, Kf, CCT, CYL, SRI, and SAI between the higher and lower eyes (P>0.05; Table 2). The difference in binocular diopters of the non-anisometropia group was 0.26±0.18 D.

Table 2. The baseline parameters between the less myopic eyes and the more myopic eyes.

| Parameters | Anisometropia group |

Inspection value | P | Non-anisometropia group |

Inspection value | P | ||

| More myopic eyes (n=63) | Less myopic eyes (n=63) | More myopic eyes (n=67) | Less myopic eyes (n=67) | |||||

| SE (D) | -5.23±1.86 | -2.95±1.75 | Z=-6.906 | <0.001a | -4.12±1.33 | -3.86±1.33 | t=-11.848 | <0.001a |

| AL (mm) | 25.76±1.01 | 24.87±1.00 | t=13.072 | <0.001a | 25.28±0.91 | 25.16±0.94 | t=3.516 | <0.001a |

| Ks (D) | 44.22±1.49 | 44.31±1.46 | Z=-1.634 | 0.102 | 43.82±1.29 | 43.78±1.29 | Z=-0.901 | 0.368 |

| Kf (D) | 43.01±1.36 | 42.97±1.43 | t=0.716 | 0.477 | 43.09±1.28 | 42.95±1.68 | t=1.098 | 0.276 |

| CCT (µm) | 543.36±32.33 | 543.06±32.68 | Z=-0.156 | 0.876 | 546.74±27.61 | 547.08±27.51 | t=-0.494 | 0.623 |

| CYL (D) | 1.19±0.63 | 1.32±0.71 | t=-1.960 | 0.054 | 0.73±0.37 | 0.68±0.37 | Z=-1.077 | 0.282 |

| SRI | 0.13±0.12 | 0.14±0.15 | Z=-0.841 | 0.400 | 0.10±0.10 | 0.10±0.12 | Z=-1.047 | 0.295 |

| SAI | 0.30±0.11 | 0.31±0.17 | Z=-0.204 | 0.838 | 0.29±0.11 | 0.30±0.19 | Z=-0.190 | 0.850 |

D: Diopter; SE: Spherical equivalent; AL: Axial length; Ks: Steep keratometry; Kf: Flap keratometry; CCT: Central corneal thickness; CYL: Corneal astigmatism; SRI: Surface regularity index; SAI: Surface asymmetry index. aStatistically significant difference.

RDVs Under Different Eccentricity Ranges in the Anisometropia Group and Non-anisometropia Group

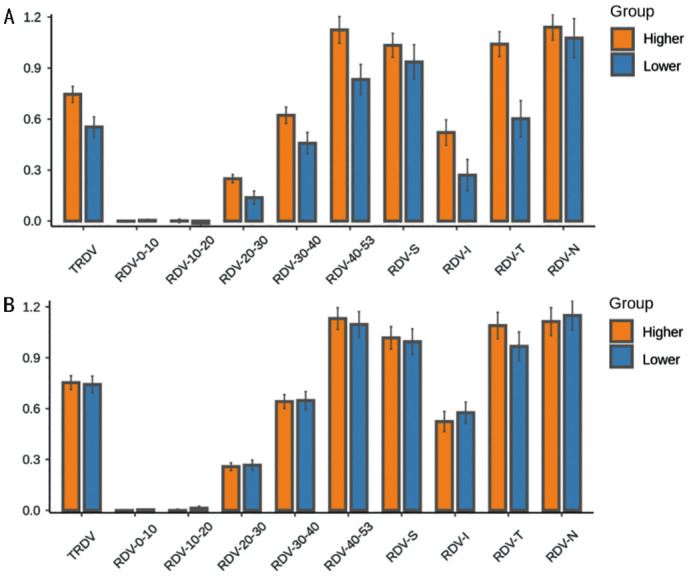

In the myopic anisometropia group, the RDVs of 63 patients with different eccentricities were compared. The TRDV, RDV-20-53, RDV-S, and RDV-T of the more myopic eyes were significantly higher than those of the less myopic eyes, and the differences were all statistically significant (P<0.05; Table 3, Figure 3). In the myopic non-anisometropia group consisting of 67 patients, there was no significant difference in any of the RDVs between the more and less myopic eyes under different eccentricities (P>0.05; Table 3, Figure 3).

Table 3. Comparison of RDVs between the less myopic eyes and the more myopic eyes.

| Parameters | Anisometropia group |

Inspection value | P | Non-anisometropia group |

Inspection value | P | ||

| More myopic eyes (n=63) | Less myopic eyes (n=63) | More myopic eyes (n=67) | Less myopic eyes (n=67) | |||||

| TRDV | 0.746±0.376 | 0.554±0.474 | t=3.505 | 0.001a | 0.753±0.334 | 0.742±0.408 | t=0.372 | 0.711 |

| RDV-0-10 | -0.001±0.034 | 0.005±0.043 | Z=-0.319 | 0.750 | -0.003±0.026 | 0.003±0.031 | t=-1.199 | 0.235 |

| RDV-10-20 | 0.001±0.081 | -0.014±0.135 | Z=-1.520 | 0.129 | -0.003±0.084 | 0.013±0.092 | Z=-1.324 | 0.185 |

| RDV-20-30 | 0.249±0.198 | 0.138±0.310 | Z=-3.201 | 0.001a | 0.257±0.187 | 0.266±0.249 | t=-0.364 | 0.717 |

| RDV-30-40 | 0.622±0.383 | 0.458±0.504 | t=2.580 | 0.012a | 0.641±0.336 | 0.648±0.429 | t=-0.194 | 0.847 |

| RDV-40-53 | 1.124±0.622 | 0.833±0.709 | t=3.702 | <0.001a | 1.131±0.521 | 1.100±0.620 | t=0.835 | 0.407 |

| RDV-S | 1.034±0.560 | 0.936±0.804 | t=1.182 | 0.242 | 1.018±0.545 | 0.995±0.620 | t=0.454 | 0.651 |

| RDV-I | 0.521±0.594 | 0.270±0.732 | t=2.722 | 0.008a | 0.524±0.485 | 0.576±0.515 | t=-1.093 | 0.278 |

| RDV-T | 1.041±0.580 | 0.602±0.851 | Z=-3.618 | <0.001a | 1.090±0.637 | 0.967±0.693 | Z=-1.212 | 0.226 |

| RDV-N | 1.140±0.603 | 1.077±0.906 | t=0.555 | 0.581 | 1.113±0.673 | 1.150±0.713 | t=-0.392 | 0.696 |

RDV: Refraction difference value; RDV at five retinal eccentricities, from the fovea to 53 degrees recorded as RDV-0-10, RDV-10-20, RDV-20-30, RDV-30-40, and RDV-40-53. TRDV: Retinal total refraction difference value of 53°; TRDV: Total RDV; RDV-S: RDV-superior; RDV-I: RDV-inferior; RDV-T: RDV-temporal; RDV-N: RDV-nasal. aStatistically significant difference.

Figure 3. Comparison of RDVs in the myopic anisometropia group (A) and non-anisometropia group (B) under different eccentricities between the more and less myopic eyes.

RDV: Refraction difference value; RDVs at five retinal eccentricities, from the fovea to 53 degrees recorded as RDV-0-10, RDV-10-20, RDV-20-30, RDV-30-40, and RDV-40-53. TRDV: Total RDV; RDV-S: RDV-superior; RDV-I: RDV-inferior; RDV-T: RDV-temporal; RDV-N: RDV-nasal.

Relationship Between RDVs at Different Eccentricities, Myopic Diopters, and Ocular Biological Parameters

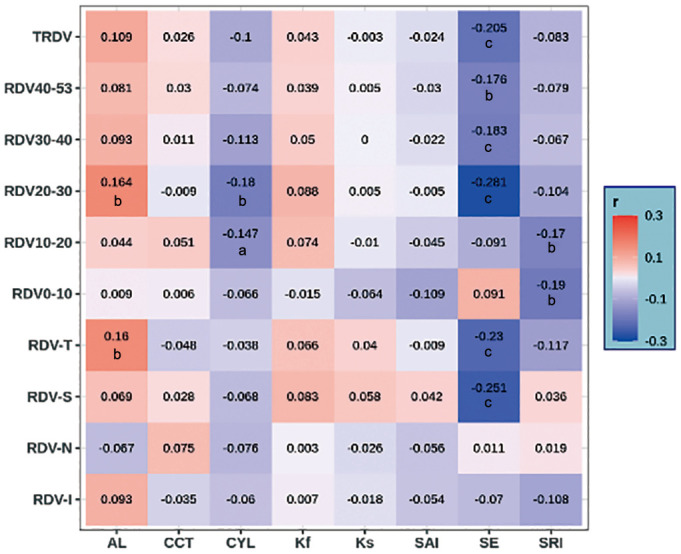

Spearman's correlation analysis showed that SE was negatively correlated with TRDV (r=-0.205, P=0.001), RDV-20-53 (r=-0.281, -0.183, -0.176, P<0.05), RDV-S (r=-0.251, P<0.001), and RDV-T (r=-0.230, P<0.001). The AL was positively correlated with RDV-20-30 (r=0.164, P=0.008) and RDV-T (r=0.160, P=0.010). The CYL was negatively correlated with RDV-10-30 (r=-0.147, -0.180, P<0.05), and SRI was negatively correlated with RDV-0-20 (r=-0.190, -0.170, P<0.05). Ks, Kf, CCT, and SAI were not correlated with the RDV (P>0.05; Figure 4).

Figure 4. Correlation analysis of RDV with diopter and ocular biometric parameters under different eccentricities (Spearman's correlation analysis).

RDV: Refraction difference value of the retina; RDVs at five retinal eccentricities, from the fovea to 53 degrees recorded as RDV-0-10, RDV-10-20, RDV-20-30, RDV-30-40, and RDV-40-53; TRDV: Total RDV; RDV-S: RDV-superior; RDV-I: RDV-inferior; RDV-T: RDV-temporal; RDV-N: RDV-nasal. AL: Axial length; CCT: Central corneal thickness; CYL: Corneal astigmatism; Kf: Flap keratometry; Ks: Steep keratometry; SAI: Surface asymmetry index; SE: Spherical equivalent; SRI: Surface regularity index. aP<0.05, bP<0.01, cP<0.001.

DISCUSSION

Anisometropia is a worldwide public health problem. The prevalence of anisometropia has been estimated to vary between 1.6% and 35.3% across different age groups and nations[12], and several studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of anisometropia is higher in children and adolescents, and it may be associated with the development of myopia. However, this is relatively stable in adulthood, which may be related to the stability of the adult refractive state[13]. The causes of anisometropia are related to the different growth rates of the binocular axial length in the process of binocular emmetropia in childhood[1]. Additionally, the degree of anisometropia is positively correlated with the diopter of myopia and the difference in binocular axial length, thus, with the increase in myopia diopter, the amount of anisometropia also increases[14]–[15].

Peripheral defocus refers to the refractive error state of the peripheral retina; the optics of the eye and the shape of the retina both contribute to the peripheral refraction of the retina[16]. Defocus of the peripheral retina also plays a significant role in controlling the growth of the eye and it may be related to defocusing-induced changes in choroidal thickness[17]. Benavente-Pérez et al[18] used +5 D and -5 D bifocal contact lenses were used to induce hyperopia and myopic defocus on the peripheral retina of marmosets, respectively, and found that modifying the refractive state and eye growth can be achieved by manipulating peripheral retinal defocus. Smith et al[9] also found that when the defocused signals around the retina and the center contradict, the defocused signals around the retina occupy a dominant position in the process of eye growth and development. Wallman and Winawer[19] pointed out that the refractive state of the peripheral retina exerts a stronger influence on ocular growth and refractive development than the refractive state of the macular central fovea, primarily because there are more optic nerve fibers in the peripheral retina than in the central region. When the retina receives visual signals both from the central and peripheral retina, signals from the numerous neurons in the peripheral retina may suppress the signals from the central retina, thereby directly influencing refractive development and ocular growth. In addition, Zhong et al[20] labeled focus-sensitive retinal neurons (bipolar cells and amacrine nerve cells ) with immunocytochemical markers after altering the quality of visual images in infant monkeys and found that visual neurons are more susceptible to hyperopic defocus than myopic defocus signals. It is inferred that differences in the distribution and sensitivity of these visual neurons may be important factors in the different responses of the retina to peripheral defocus in different regions, with different impacts on ocular growth. Understanding the relationship between central refraction and peripheral retinal defocus has important implications for the control of myopia.

It has been shown that the refractive condition of the peripheral retina varies with central refraction, that myopic children and adults usually show more hyperopic defocus in the peripheral retina, and that the degree of hyperopic defocus in the peripheral retina increases with axial myopia[21]–[23]. Findings of the current study are similar to those of the aforementioned studies. Specifically, we discovered that the myopic eyes in both groups were relatively hyperopic defocused in the range of 20-53 retinal eccentricity, and the value of RDV increased with the increase in eccentricity; in this study, a negative correlation was also found between SE and TRDV, RDV-20-53, RDV-T. Zheng et al[21] found a positive correlation between AL and RDV-20-45 through MRT in 241 young patients with myopia and found that AL is an independent risk factor for retinal defocus within the range of 20-35 eccentricity. In our study, we found that AL was positively correlated with RDV-20-30 in patients with myopic anisometropia. We speculated that the retinal defocus of 20-30 eccentricity range may stimulate the growth of AL, which is a crucial element that impacts the emergence and progression of myopia.

In the myopic anisometropia group in the present study, the TRDV, RDV-20-53, RDV-S, and RDV-T of the more myopic eyes were significantly higher than those of the less myopic eyes. This is evidenced by the absence of a significant difference in peripheral retinal defocus between the more and less myopic eyes under different eccentricities in the non-anisometropia group. The results showed that when the diopter difference of both eyes was greater than 1.0 D, the difference in peripheral retinal defocus was different in both eyes. Conversely, when the difference in binocular diopter was less than 1.0 D, the difference in binocular retinal defocus was not significant. Clinical studies have found that orthokeratology, defocus soft, defocus frame, and multifocal soft lenses reduce the defocus of peripheral hyperopia through refractive correction and thus control the progress of myopia[24]–[28]. Personalized selection and customization of binocular myopia prevention and control tools are particularly important. Due to the significant difference in peripheral retinal defocus in both eyes of patients with myopic anisometropia, is it possible to customize myopia control tools based on the original peripheral retinal values of more and less myopic eyes to better help teenagers with myopic anisometropia in myopia control. This will be the direction of future research.

There was a negative correlation between CYL and RDV-10-30, suggesting that with the increase of corneal astigmatism, the value of retinal defocus in the range of 10-30 eccentricity will also increase. The SRI is used to evaluate the refractive power distribution of 256 radial lines within the diameter of 4 mm in the central area of the cornea. It is mainly used to assess the regularity of the cornea. The more regular the corneal surface, the lower the SRI. There was a negative correlation between SRI and RDV-0-20 in the present study, suggesting that the regularity of the central corneal region has a certain impact on the retinal defocus in the range of 0-20 eccentricity. Therefore, the diopter and corneal morphology of the eye may affect the peripheral defocus of the retina. Due to the limitations of sample size and diopter distribution in this study, a complex regulatory relationship may exist between myopia, corneal morphology, and retinal peripheral refraction; thus, further studies with a larger sample size and longer duration are needed. Moreover, due to the small sample size, further grouping was not carried out according to the severity of anisometropia.

In conclusion, patients with myopia show peripheral hyperopic defocus, and the peripheral retinal defocus values of both eyes in myopic anisometropia patients are significantly different. These results serve as a reference and theoretical foundation for the selection of personalized optical correction methods for myopic anisometropia in clinic settings. They also provide new ideas for behavioral interventions for myopia prevention and control in adolescents with myopic anisometropia.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest: Du YQ, None; Zhou YH, None; Ding MW, None; Zhang MX, None; Guo YJ, None; Ge SS, None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vincent SJ, Collins MJ, Read SA, Carney LG. Myopic anisometropia: ocular characteristics and aetiological considerations. Clin Exp Optom. 2014;97(4):291–307. doi: 10.1111/cxo.12171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nunes AF, Batista M, Monteiro P. Prevalence of anisometropia in children and adolescents. F1000Res. 2021;10:1101. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.73657.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wajuihian SO, Mashige KP. Gender and age distribution of refractive errors in an optometric clinical population. J Optom. 2021;14(4):315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.optom.2020.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flitcroft I, McCullough S, Saunders K. What can anisometropia tell us about eye growth? Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;105(9):1211–1215. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-316406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karimian F, Ownagh V, Amiri MA, Tabatabaee SM, Dadbin N. Stereoacuity after wavefront-guided photorefractive keratectomy in anisometropia. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2017;12(3):265–269. doi: 10.4103/jovr.jovr_138_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovasik JV, Szymkiw M. Effects of aniseikonia, anisometropia, accommodation, retinal illuminance, and pupil size on stereopsis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985;26(5):741–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Emamian MH, Shariati M, Abdolahi-nia T, Fotouhi A. All biometric components are important in anisometropia, not just axial length. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(12):1586–1591. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Sankaridurg P, Donovan L, Lin Z, Li L, Martinez A, Holden B, Ge J. Characteristics of peripheral refractive errors of myopic and non-myopic Chinese eyes. Vision Res. 2010;50(1):31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith EL, Hung LF, Huang J. Relative peripheral hyperopic defocus alters central refractive development in infant monkeys. Vis Res. 2009;49(19):2386–2392. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao YR, Yang ZL, Li ZJ, Zeng R, Wang J, Zhang YC, Lan YQ. A quantitative comparison of multispectral refraction topography and autorefractometer in young adults. Front Med. 2021;8:715640. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.715640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu WC, Ji RY, Ding WZ, Tian YY, Long KL, Guo Z, Leng L. Agreement and repeatability of central and peripheral refraction by one novel multispectral-based refractor. Front Med. 2021;8:777685. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.777685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou D. Research progress on anisometropia. Chin J Optom & Ophthalmol. 2016;18:504–507. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohammadi E, Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Emamian MH, Shariati M, Fotouhi A. The prevalence of anisometropia and its associated factors in an adult population from Shahroud, Iran. Clin Exp Optom. 2013;96(5):455–459. doi: 10.1111/cxo.12045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai WS, Wang JH, Lee YC, Chiu CJ. Assessing the change of anisometropia in unilateral myopic children receiving monocular orthokeratology treatment. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118(7):1122–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pärssinen O, Kauppinen M. Anisometropia of spherical equivalent and astigmatism among myopes: a 23-year follow-up study of prevalence and changes from childhood to adulthood. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017;95(5):518–524. doi: 10.1111/aos.13405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verkicharla PK, Mathur A, Mallen EA, Pope JM, Atchison DA. Eye shape and retinal shape, and their relation to peripheral refraction. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2012;32(3):184–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2012.00906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang YY, Wang YL, Shen Y, et al. Defocus-induced spatial changes in choroidal thickness of chicks observed by wide-field swept-source OCT. Exp Eye Res. 2023;233:109564. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2023.109564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benavente-Pérez A, Nour A, Troilo D. Axial eye growth and refractive error development can be modified by exposing the peripheral retina to relative myopic or hyperopic defocus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(10):6765–6773. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallman J, Winawer J. Homeostasis of eye growth and the question of myopia. Neuron. 2004;43(4):447–468. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhong XW, Ge J, Smith EL, 3rd, Stell WK. Image defocus modulates activity of bipolar and amacrine cells in macaque retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(7):2065–2074. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng XY, Cheng DJ, Lu XL, Yu XY, Huang YT, Xia YJ, Lin CN, Wang Z. Relationship between peripheral refraction in different retinal regions and myopia development of young Chinese people. Front Med. 2022;8:802706. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.802706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao Q, Du XL, Yang Y, Zhou YL, Zhao XX, Shan XB, Meng YX, Zhang M. Quantitative analysis of peripheral retinal defocus checked by multispectral refraction topography in myopia among youth. Chin Med J. 2023;136(4):476–478. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu XL, Zheng XY, Lian LH, Huang YT, Lin CN, Xia YJ, Wang Z, Yu XY. Comparative study of relative peripheral refraction in children with different degrees of myopia. Front Med. 2022;9:800653. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.800653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ni NJ, Ma FY, Wu XM, Liu X, Zhang HY, Yu YF, Guo MC, Zhu SY. Novel application of multispectral refraction topography in the observation of myopic control effect by orthokeratology lens in adolescents. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9(30):8985–8998. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i30.8985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beasley IG, Davies LN, Logan NS. Effect of peripheral defocus on axial growth and modulation of refractive error in children with anisohyperopia. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2023;43(4):805–814. doi: 10.1111/opo.13139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radhakrishnan H, Lam CSY, Charman WN. Multiple segment spectacle lenses for myopia control. Part 1: optics. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2023;43(5):1125–1136. doi: 10.1111/opo.13191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen YY, Ding CL, Li X, Huang YY, Zhou FC, Drobe B, Chen H, Bao JH. Comparison of visual performance between peripheral gradient high-addition multifocal soft contact lenses and orthokeratology. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2023;43(4):874–884. doi: 10.1111/opo.13144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erdinest N, London N, Lavy I, Berkow D, Landau D, Morad Y, Levinger N. Peripheral defocus and myopia management: a mini-review. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2023;37(1):70–81. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2022.0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]