Abstract

For behavior analytic practitioners, skills related to building a therapeutic alliance (e.g., empathic statements, reflective listening, affirmations) may be as important as knowledge of and skills in implementation of the science of behavior analysis. We surveyed 277 board certified behavior analysts (BCBAs) to learn more about their training, use of these skills, and their perceptions of how their skills might have changed over years of practicing. The findings suggest that behavior analysts may benefit from explicit training in skills required to establish and maintain therapeutic relationships with parents of children with autism. In this article we review recent research in this area and suggest directions for training of behavior analysts. Further, motivational interviewing is introduced as an evidence-based clinical approach that encompasses many of the skills required to build a therapeutic alliance.

Keywords: Compassionate care, Therapeutic alliance, Parent interaction, Empathy, Motivational interviewing

Across the helping professions, the relationship between a care provider and client is considered a central component of client-centered care (Horvath et al., 2011). In many fields (e.g., medicine, psychology, social work, counseling), a positive clinician–client relationship is referred to as a therapeutic alliance. Therapeutic alliance is defined as the rapport established between the professional and the client, and their agreement on treatment goals and therapeutic approach (Zilcha-Mano et al., 2015). Decades of research across multiple helping professions has identified variables that foster and inhibit development and maintenance of the therapeutic alliance, and this research may have important implications for practicing behavior analysts.1

The Importance of a Therapeutic Alliance

Overall, research indicates that therapeutic alliance is made up of three elements: agreement on goals for treatment, agreement on interventions, and an affective bond between clinician and client (see Baier et al., 2020, for a systematic review). It is perhaps not a surprise that there is substantial research documenting that the therapeutic alliance between clinician and client is one of the most consistent predictors of positive treatment outcomes (Horvath et al., 2011). Further, cross-disciplinary research has demonstrated a positive correlation between therapeutic alliance and client’s active participation in the intervention process (e.g., Allen et al., 2017) and adherence with intervention recommendations (Bourke et al., 2021), with client satisfaction (Zendjidjian et al., 2014) and with clinical outcomes (Croft & Watson, 2019). In sum, this research shows that when the therapeutic alliance is strong, not only are clients more engaged in the intervention process, but outcomes are better than when the relationship between the client and helping professional is not strong. The benefits of a positive therapeutic alliance are well-established within the literature of a myriad of disciplines; yet the relationship between a clinician and a client (e.g., parent or teacher) has received only minimal attention in applied behavior analysis (ABA).

Applied behavior analysis has been, and continues to be, characterized by seven dimensions first described by Baer et al. (1968) and restated and expanded upon by Baer and Wolf (1987). Adherence to those dimensions: applied, behavioral, analytic, technological, conceptual, effective, capacity for appropriately generalized outcomes, and the focus on socially significant results characterizes virtually all the training and dissemination activities in our field. However, until relatively recently there has been little attention paid to whether the “practice” of behavior analysis might require additional skills. In 1998, Foxx argued that behavior analysts who delivered services with attention to interpersonal relations were more effective than those who did not. Foxx referred to behavior analysts who demonstrated strong interpersonal skills in their work as “behavioral artists” (Foxx, 1998, p. 14). Following up on this work, Callahan et al. (2019) compared the interpersonal skills of students in ABA programs to students in other helping professions and found that students in ABA had lower levels of “behavioral artistry” than did students in other human services areas and even students in non-human services degree areas. Callahan et al. then had parents rate the interpersonal skills of therapists during videotaped samples of them working with an autistic child. Practitioners with higher scores in behavioral artistry were rated by parents, who were blind to these scores, as delivering ABA in a more positive manner than those with lower scores. Also in 2018, Taylor et al. surveyed 95 parents of children with autism who were receiving home-based ABA services. Parents were contacted via email through autism specific listservs and social media. Taylor et al. collected information on parents’ impressions of board certified behavior analysts’ (BCBA) therapeutic relationship skills and variables affecting those skills and reported that parents viewed BCBAs as lacking interpersonal skills across a breadth of areas including listening and collaborating, empathy and compassion, and approach to their work. Taken together, the findings of Callahan et al. (2019) and Taylor et al. (2018) suggest that many BCBAs would benefit from explicit training in skills required to establish and maintain therapeutic relationships.

One possible reason for the deficits in therapeutic relationship skills may be that, by and large, BCBAs do not receive training in these skills (e.g., empathic statements, reflective listening, affirmations), which is in contrast to training in other professions (e.g., social work, psychology, medicine, counseling). LeBlanc et al. (2019) conducted a survey of BCBAs to explore their training experiences in this area. Across 221 respondents recruited via social media (most certified for 3 or more years at the master’s level and working in autism), only a minority (28%) reported having a lecture in class or a reading on the topic of compassionate care or therapeutic relationship building. Further, the vast majority (82%) reported no formal training in their practicum or supervised experience in therapeutic relationship skills. Almost all respondents (94%) indicated that their colleagues sometimes or often struggled with these skills and that these skills should be taught in training programs. Leblanc et al. concluded that formal training in this area would be of benefit to practicing behavior analysts.

Although previous literature demonstrates that at least some stakeholders (parents of autistic children) believe that BCBAs would benefit from training in therapeutic relationship building and that training in these skills is generally lacking from the curriculum of training programs, we wondered whether BCBAs would identify these skills as lacking in their own repertoires. According to Leblanc et al. (2019), 94% of BCBAs are indicating that their colleagues need help but are BCBAs self-assessing and identifying their own individual needs for improvement? This question is important because if BCBAs do not view these skills as needed in their own repertoires, they may be less likely to seek out, attend to, or be motivated by behavior change in therapeutic relationship building skills.

Further, it is important to understand if challenges exist, are they specific to certain topics and situations and whether those situations were addressed during graduate and practicum training. If we can identify common scenarios that BCBAs find challenging when interacting with parents of children with autism, supervisors and professors will be better prepared to integrate those experiences into the training curricula. Finally, it is important to understand if such challenges continue over time as a BCBA gains more experience or whether they are difficult only early in a practitioner’s career. If, for example, interactions between the parent and the BCBA are generally most challenging during the first 2 years of practice, an argument can be made for improved graduate and practicum curricula including behavioral skills training or a variation (e.g., role-play and feedback) to address those particularly challenging interactions prior to BCBAs entering the workforce. In addition, ongoing supervision in compassionate care during an early career BCBA’s practice may prove useful when difficult topics are broached and discrepancies arise between the BCBA and parent. If, however, these challenges persist over time, continuing education could be especially important. In addition, research might investigate the role these variables play in burnout and low-quality service delivery. Thus, one purpose of this study was to further explore the training and practical experiences of behavior analysts when interacting with parents of children with autism as well as identify specific interactions which may cause the most challenge, as a follow up to Leblanc et al. (2019).

Motivational Interviewing and the Therapeutic Alliance

Because prior research suggests that increased training in these areas could be helpful, we also assessed BCBAs’ familiarity with motivational interviewing (MI), an evidence-based approach to enhancing therapeutic relationships. MI is supported by decades of research that suggest that its use increases engagement in the intervention process, decreases client dropout, and improves adherence to treatment recommendations (Hettema & Hendricks, 2010; Lundahl et al., 2013). These findings have been replicated across diverse areas in the helping professions, which also indicate that MI improves treatment outcomes. Areas of application include but are not limited to drug and alcohol abuse (Barnett et al., 2012), smoking cessation (Heckman et al., 2011), gambling (Yakovenko et al., 2015), weight loss (Barnes & Ivezaj, 2015), and medical and pharmaceutical interventions (Ekong & Kavookjian, 2016). Due to the success of MI for broadly improving therapeutic outcomes, MI has been adopted by professionals across a myriad of disciplines including physicians (Kaltman & Tankersley, 2020), psychologists and other behavioral health providers (Barwick et al., 2012), nurses (Ostlund et al., 2015), dentists (Faustino-Silva et al., 2019), and social workers (Pecukonis et al., 2016). Given the outcomes observed in other fields (e.g., increased engagement, improved attendance, and adherence to treatment recommendations), it may behoove behavior analysts to consider this approach as one potential solution for current skill deficits in the area of therapeutic alliance skills.

MI has been defined as “a collaborative, goal-oriented style of communication . . . within an atmosphere of acceptance and compassion” (Miller & Rollnick, 2013, p. 29). MI is an approach that incorporates specific techniques along with a general style of interaction with the goal being to demonstrate empathy, compassion, listening, reflection, and clarification (Magill et al., 2018). This relational context for MI serves as the foundation for a therapeutic relationship to be built and ultimately produce positive client outcomes (Moyers, 2014). The primary focus of MI is on the way that a clinician communicates with a client; and the overall style of MI as well as specific strategies used in MI designed to lead to and sustain a collaborative, supportive, and empathic relationship between clinician and client. This evidence-based approach offers a curriculum to establish skills needed to create a therapeutic alliance and, therefore, may be useful to behavior analysts working with parents.

A key component of MI is what are referred to as “core skills.” These skills serve as the foundation for the use of MI in therapeutic relationships and include the following clinician behaviors: asking open ended questions, affirming a client’s statements, reflecting what a client has said, and summarizing client communication. These skills are often referred to using the acronym OARS—open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, summarizing. For example, the use of an open-ended question such as, “Can you tell me about the highs and lows of your week?” offers the opportunity for a parent to share more information vs. a close-ended question such as, “Did you have a good week?,” which would result in a one-word answer (e.g., “good,” “fine”). Using affirmations recognizes a parent’s strengths and demonstrates positive regard and genuine care, for example, “Wow, you have been working really hard to implement this plan, it is clear how much you want to support your daughter.” Reflections are a skill used to demonstrate reflective listening and offer an opportunity to seek clarification. A BCBA may say to a parent, “I hear that you are feeling worried about your child’s future and his ability to be independent, what are three skills that he could learn that would make you feel better about that?” Finally, summaries are another form of reflective listening and allow the clinician to recap a conversation and indicate the agreed upon next steps such as, “Today we talked about the recent progress which has been made with his ability to tell you what he wants through manding, you also shared with me your concerns about toilet training, and it sounds like this is the next area you would like to target and you are prepared to take that step, is that right?” When a clinician demonstrates proficiency in OARS they are more likely to establish a therapeutic alliance, which sets the occasion for collaboration (Miller & Rollnick, 2002), information sharing (Tollison et al., 2008), and ultimately behavior change (Christopher & Dougher, 2009). Each of these OARS skills combine to serve as the foundation for building rapport and establishing a therapeutic alliance and are aligned with the skills which recent research has suggested BCBAs need to practice and acquire (Taylor et al., 2018).

The purpose of this study was twofold. First, we wanted to further explore the training and practical experiences of behavior analysts when interacting with parents of children with autism and determine whether we could identify patterns with regard to interactions that may be most challenging and if those challenges persist over time. Second, we explored BCBAs familiarity with MI and the extent to which they identified these skills as important and needed in their own practice. The answers to these questions could guide future training and ongoing supervision curricula and shape the mentoring process for BCBAs across their career progression.

Methods

Participants

BCBAs and BCBA-Ds were recruited through social media sites (e.g., Facebook and LinkedIn) and were behavior analysts who worked with autistic children and their families. A total of 310 surveys were received, 277 of which were included in the final analysis. Thirty-three surveys were excluded because participants reported they were not BCBAs. Just over half of respondents (55%, n = 151) indicated that they had been practicing for 6 or more years, 25% (n = 69) indicated they had been practicing for 3–5 years, and 21% (n = 57) reported practicing 2 years or fewer. The frequency of parent meetings was variable, ranging from at least weekly (42%, n = 115) to 1–2 times per month, 18% (n = 49). Only 5% (n = 15) reported meeting less than monthly.

Procedure

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the organizations where the authors were either employed or in graduate school at the time of the study. We developed the survey based on reviews of the literature and experience supervising BCBAs. Once a pilot version had been developed, it was reviewed by two licensed psychologists and behavior analysts who had coursework and supervision focused on skills to enhance therapeutic relationships during their graduate and postgraduate training, including recent publications and presentations in this area. Taken together, these professionals had over 50 years of experience working in clinical practice and supervision and therefore were able to provide meaningful feedback, which was incorporated into the final version of the survey. The survey was administered using Qualtrics, a survey software research tool with automatic and anonymous analytics. The survey consisted of 28 questions grouped into three areas: topics during parent discussions (11 questions), graduate training on managing challenges associated with parent interactions (7 questions), and managing challenges in first year of practice versus later years (10 questions). In addition to these 28 questions, the survey included five demographic questions to assist with participant characterization and four questions about participant’s familiarity with MI.

Results

Results are organized by topic area including (1) topics during parent discussions (11 questions); (2) graduate training on managing challenges associated with parent interaction (7 questions); (3) managing challenges in first year of practice versus later years (10 questions); and (4) familiarity with MI (4 questions).

Topics Discussed During Parent Discussions

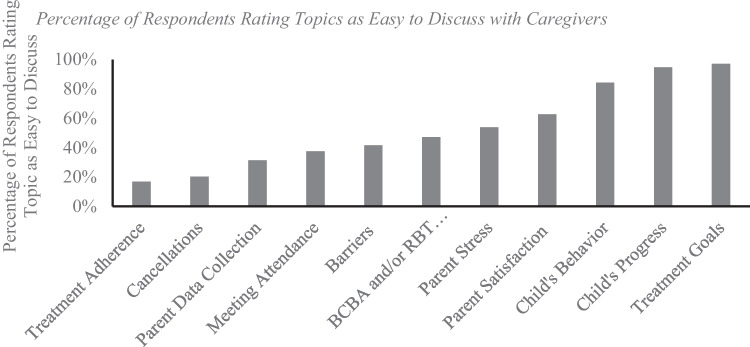

BCBAs were asked to rate the perceived difficulty of discussing 11 different topics with parents on an 3-point Likert-style scale ranging from 1 to 3 with 1 being “This is an easy topic to bring up and/or discuss,” 2 being “This is a difficult/challenging topic to bring up and/or discuss but I do so when necessary,” and 3 being “I often avoid bringing up this topic in parent meetings.” There was an additional N/A selection, “I have never had a discussion about this topic or viewed this topic as necessary to address.” As is shown in Fig. 1, a substantive majority of respondents reported that discussing treatment goals (97.11%), a child’s progress (94.64%), and child behavior during sessions (84.34%) were easy topics to bring up and/or discuss, and a slight majority reported that parent satisfaction with services (62.68%) and parent level of stress (53.36%) were easy topics to bring up and/or discuss. In contrast, only a small percentage of participants reported that topics such parent adherence to intervention recommendations (16.84%), cancelation of services (20.28%), parent-collected data (31.23%), parent attendance at meetings (37.46%), and barriers to effective interventions (39.43%) were easy topics to bring up and/or discuss.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of Respondents Rating Topics as Easy to Discuss with Caregivers

Graduate Coursework and Practicum Training in Therapeutic Relationship Skills

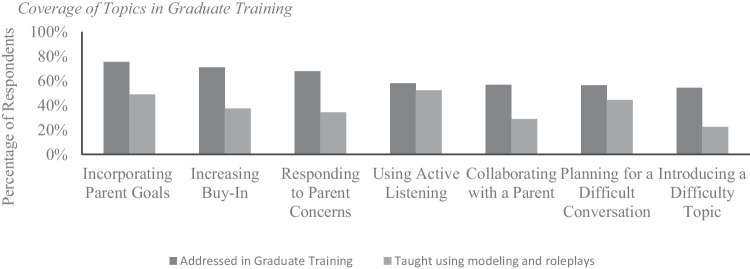

To explore respondents’ training in therapeutic relationship skills during graduate coursework and practicum training, we asked respondents to indicate (1) whether a topic had been addressed during training and, (2) if so, whether that skill had been explicitly taught using role plays and feedback (i.e., behavior skills training or variation). As is shown in Fig. 2, over half of participants (ranging from 54.5% to 75.5%, depending on topic) indicated that topics related to interacting with parents were addressed during at least one class or practicum supervision meeting. However, only a small percentage of respondents indicated they had received explicit training using modeling, rehearsal, and feedback during their graduate training.

Fig. 2.

Coverage of Topics in Graduate Training

Changes in Perceptions of Challenge and Years Practicing

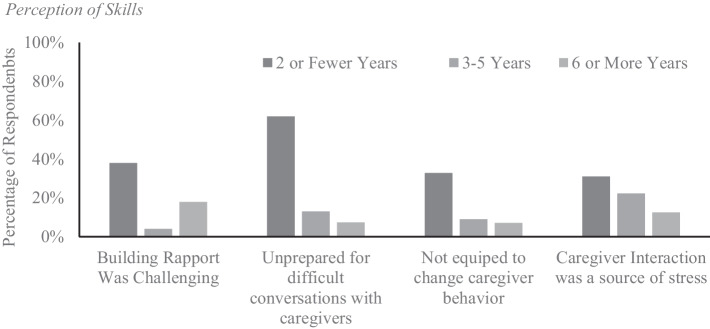

To explore whether behavior analysts’ self-perception of skills in working with parents might change as a function of years in practice, we compared answers of BCBAs who had been practicing 2 years or fewer (n = 57) with those practicing between 3 and 5 years (n = 69) and those practicing 6 years or longer (n = 151). It is not surprising that more junior BCBAs reported fewer skills in parent interactions than did BCBAs with more years practicing, which was especially evident regarding perceptions of skills in the areas of building rapport, having difficult conversations, and addressing parent behavior (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Perception of Skills

Motivational Interviewing Questions

When participants were asked if they could benefit from additional training on how to increase parent buy-in to treatment, 74.73% (n = 207) agreed or strongly agreed that they would benefit. Only a small proportion of total respondents, 22.79% (n = 62), reported being familiar with MI. Of this subset of 62 respondents who said they were familiar with MI, only 11 people, when asked to describe MI, provided a response that aligned with the core characteristics of MI. Of the 62 people, 14 (22.60%) indicated that they were introduced to MI during graduate or practicum training, suggesting that the majority of individuals learned about MI after their formal training was complete (e.g., during continuing education events and independent learning). It is interesting that although only 11 responses indicated these individuals might have a basic understanding of MI, 28 respondents (45.16% of the 62 people) reported that they often or always used MI when communicating with parents.

Discussion

Prior research has indicated that parents may view behavior analysts as lacking in core skills associated with building a therapeutic alliance (Callahan et al., 2019; Taylor et al., 2018) and that behavior analysts desire more training in this area (LeBlanc et al., 2019). We sought to add to this work by exploring whether specific interactions between a BCBA and a parent might be more challenging than others, whether those situations perceived as difficult were included in graduate training, if challenges reduce over time as BCBAs gain more experience in clinical practice, and if motivational interviewing was a familiar treatment approach for BCBAs. Overall, our findings further suggest that behavior analysts would benefit from additional training in therapeutic relationship skills and that motivational interviewing is not a familiar treatment approach. Moreover, because motivational interviewing is not an approach which BCBAs are trained in or using in clinical practice, yet it encompasses many of the suggested skills for improvement in the area of compassionate care, perhaps it should be considered to address the field's current areas of deficit.

In the area of compassionate care, much of our current literature is based on the self-report of parents and/or BCBAs (Callahan et al., 2019; Taylor et al., 2018; LeBlanc et al., 2019). Although self-report measures are used infrequently by behavior analysts, due in part to the field’s emphasis on direct observation and functional control, there are research questions however, when indirect methods such as self-report may be most appropriate. The purpose of this study, to learn more about behavior analyst’s perceptions of (1) their training and (2) interactions with caregivers are such research questions because there is simply no other way to understand perceptions than by asking about experiences. Although direct observation of clinician/caregiver interactions in either analog or natural settings is possible, without a very large sample and use of repeated observations, results would be limited to the specific scenario assessed and the conditions under which that assessment was conducted. Self-report measures in this study allowed us to glean information about behavior analyst’s perceptions of their training and interactions that may be challenging for them. A tradition in our field is to view self-report measures with suspicion however these measures are used widely in fields such as psychology and medicine and the reliability and validity of measures used in research (as well as practice) is well-established. Examples include but are not limited to self-reports of pain (see Birnie et al., 2019, for a systematic review), binge eating (see Burton et al., 2016, for a systematic review), anxiety (see Modini et al., 2015, or Zuccala et al., 2019, for systematic reviews), and parent report of child experiences and/or parenting experiences (see Jaafar et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2016; Pontoppidan et al., 2017, for systematic reviews).

Over the last 25 years, although several behavior analysts (Callahan et al., 2019; Foxx, 1998; Leblanc et al., 2019; Taylor et al., 2018) have advocated for increased attention to these variables, there has been little offered regarding what training should focus on or entail for behavior analysts, or research to support the efficacy of recommended approaches. Rather than reinvent the proverbial wheel by developing new training materials that may or may not actually result in increased clinician skills in these areas, we recommend that those charged with training behavior analysts integrate motivational interviewing into their coursework and practicum training. Motivational interviewing is often referred to as an intervention strategy and has been found to be very successful for increasing change-related behaviors in individuals (e.g., increasing adherence to intervention recommendations), and a large body of research supports its efficacy as an intervention approach and demonstrates that, when clinicians are taught to implement motivational interviewing, they are better able to develop and maintain therapeutic relationships and enhance client outcomes (Maslowski et al., 2021; Schwalbe et al., 2014). Further, many studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of motivational interviewing training protocols. This literature has been summarized across six meta-analytic reviews documenting significant changes in knowledge, use of MI skills during roleplays, and in work with clients, and maintenance of skills over time (Barwick et al., 2012; de Roten et al., 2013; Madson et al., 2009, 2019; Maslowski et al., 2021; Schwalbe et al., 2014). Overall, changes in clinician knowledge and overt behavior have been shown to increase following training with moderate to large effect sizes, and this is true across modalities of training (e.g., workshops, coaching, and roleplays) and various training fields (e.g., mental health, corrections, and medicine) with ongoing supervision and coaching recommended to maintain behavior change posttraining and greater effects observed with longer training programs (Schwalbe et al., 2014). Given the ease by which these skills have been taught within other fields, it would behoove those charged with training behavior analysts to consider including them in their graduate and practicum training curriculums.

Inclusion of MI in training programs could occur in various ways, depending on the type of training offered in a program. For example, as prior research (Barwick et al., 2012; Schwalbe et al., 2014) shows that didactic instruction and roleplays can be effective; MI could be included as either a standalone class (e.g., Lim et al., 2014) and/or embedded within multiple courses focused on the application of behavior analysis. An additional way to incorporate MI into training programs would be to teach MI skills prior to practicum placements, and then provide feedback via supervision (e.g., Carroll et al., 2006; Martino et al., 2009) or coaching (e.g., Forsberg et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2004). Incorporating MI into training programs will require that faculty either develop skills in MI prior to teaching, partner with professionals with expertise in this area, or some combination. It is important to recognize that such training may be viewed as outside the “scope” of behavior analysis and there could be resistance to expanding a behavior analytic training program to include such an approach. Although it is true that the skillset of MI is not necessarily a direct application of behavior analysis, others (e.g., Christopher & Dougher, 2009; Oliveira & Huziwara, 2021) have articulated the mechanisms underlying the effectiveness of MI in behavior analytic terms. Further, it may not matter how well someone understands principles of behavior analysis if they are not able to implement them in a manner that clients find appealing. Chadwell et al. (2019) found that parents were more accepting of a treatment with less empirical support if the therapist demonstrated characteristics during interactions which were more favorable. The implications of a damaged therapeutic alliance, particularly when attempting to gain parent adherence and commitment to treatment are far-reaching and should be considered, particularly given the focus of behavior analysis on conceptually sound, socially significant and effective treatment. Given the potential benefits of a positive therapeutic alliance, it is critical that graduate training programs prepare students of behavior analysis to engage with clients in a way which is warm, relational, and accepting in order to set the occasion for greater commitment and thus, improved outcomes (Chadwell et al., 2019). In order to do this, training programs should adopt a curriculum to shape not only strong conceptual foundations in behavior analysis, but also therapeutic relationship skills in order to produce well-rounded and effective practitioners who engage in behaviors consistent with those necessary to build therapeutic alliances. Motivational interviewing is a clinical approach with decades of well-established empirical evidence that could be adopted into the field of behavior analysis to both address the current deficits in therapeutic relationship building skills and provide a skill set for BCBAs which may help them during those situations which are associated with their greatest professional challenges.

Data Availability

N/A.

Code Availability

N/A.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

Study approved by Endicott College and May Institute Institutional Review Boards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was gathered for all participants.

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

N/A.

Footnotes

As described below, aspects of this relationship have been referred to in the behavior analytic literature as both behavioral artistry (e.g., Foxx, 1998) and compassionate care (e.g., Taylor et al., 2018), however, we use the term therapeutic alliance given the robust research on this topic in other fields.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Allen M, Le Cook B, Carson N, Interian A, La Roche M, Alegria M. Patient-provider therapeutic alliance contributes to patient activation in community mental health clinics. Administration Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research. 2017;44(4):431–440. doi: 10.1007/s10488-015-0655-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer DM, Wolf MM. Some still-current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1987;20(4):313–327. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1987.20-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1(1):91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baier AL, Kline AC, Feeny NC. Therapeutic alliance as a mediator of change: A systematic review and evaluation of research. Clinical Psychology Review. 2020;82:101921. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes RD, Ivezaj V. A systematic review of motivational interviewing for weight loss among adults in primary care. Obesity Reviews: An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2015;16(4):304–318. doi: 10.1111/obr.12264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett E, Sussman S, Smith C, Rohrbach LA, Spruijt-Metz D. Motivational interviewing for adolescent substance use: A review of the literature. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(12):1325–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barwick MA, Bennet LM, Johnson SN, McGowan J, Moore JE. Training health and mental health professionals in motivational interviewing: A systematic review. Children & Youth Services Review. 2012;34(9):1786–1795. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birnie KA, Hundert AS, Lalloo C, Nguyen C, Stinson JN. Recommendations for selection of self-report pain intensity measures in children and adolescents: A systematic review and quality assessment of measurement properties. Pain. 2019;160(1):5–18. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourke E, Barker C, Fornells-Abrojo M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of therapeutic alliance, engagement, and outcome in psychological therapies for psychosis. Psychology & Psychotherapy: Therapy, Research & Practice. 2021;94(3):822–853. doi: 10.1111/papt.12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton AL, Abbott MJ, Modini M, Touyz S. Psychometric evaluation of self-report measures of binge-eating symptoms and related psychopathology: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2016;49(2):125–142. doi: 10.1002/eat.22453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan K, Foxx RM, Swierczynski A, Aerts X, Mehta S, McComb M, Nichols SM, Segal G, Donald A, Sharma R. Behavioral artistry: Examining the relationship between the interpersonal skills and effective practice repertoire of behavior analysis practitioners. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2019;49(3):3557–3570. doi: 10.1111/papt.12330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Nich C, Martino S, Frankforter TL, Farentinos C, Kunkel LE, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Morgenstern J, Obert JL, Polcin D, Snead N, Woody GE. Motivational interviewing to improve treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse: A multisite effectiveness study. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81(3):301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwell MR, Sikorski J, Roverts H, Allen KD. Process versus content in delivering ABA services: Does process matter when you have content that works? Behavior Analysis: Research & Practice. 2019;19(1):14–22. doi: 10.1037/bar0000143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher PJ, Dougher MJ. A behavior-analytic account of motivational interviewing. The Behavior Analyst. 2009;32(1):149–161. doi: 10.1007/bf03392180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft RL, Watson J. Students clinicians’ and clients’ perceptions of the therapeutic alliance and outcomes in stuttering treatment. Journal of Fluency Disorders. 2019;61:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jfludis.2019.105709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roten Y, Zimmermann G, Ortega D, Despland JN. Meta-analysis of the effects of MI training on clinicians' behavior. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2013;45(2):155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekong G, Kavookjian J. Motivational interviewing and outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Patient Education & Counseling. 2016;99(6):944–952. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustino-Silva DD, Meyer E, Hugo FN, Hilgert JB. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing training for primary care dentists and dental health technicians: Results from a community clinical trial. Journal of Dental Education. 2019;83(5):585–594. doi: 10.21815/jde.019.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg L, Forsberg LG, Lindqvist H, Helgason AR. Clinician acquisition and retention of Motivational Interviewing skills: A two-and-a-half-year exploratory study. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, & Policy. 2010;5(1):Article 8. doi: 10.1186/1747-597x-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxx RM. Twenty-five years of applied behavior analysis: Lessons learned. Discriminanten. 1998;4:13–31. doi: 10.1007/bf03393166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman CJ, Egleston BL, Hofmann MT. Efficacy of motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tobacco Control. 2011;19(5):410–416. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.033175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JE, Hendricks PS. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(6):868–884. doi: 10.1037/a0021498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO, Del Re AC, Fluckiger C, Symonds D. Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy. 2011;48(1):9–16. doi: 10.1037/a0022186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaafar NH, Othman A, Majid NA, Harith S, Zabidi HZ. Parent-report instruments for assessing feeding difficulties in children with neurological impairments: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2019;61(2):135–144. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltman S, Tankersley A. Teaching motivational interviewing to medical students: A systematic review. Academic Medicine. 2020;95(3):458–469. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000003011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc LA, Taylor BA, Marchese NV. The training experiences of behavior analysts: Compassionate care and therapeutic relationships with caregivers. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;13(2):387–393. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00368-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Yang H-J, Chen VC, Lee W-T, Teng M-J, Lin C-H, Gossop M. Meta-analysis of quality of life in children and adolescents with ADHD: By both parent proxy-report and child self-report using PedsQLTM. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2016;51–52:160–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim G, Park I, Park S, Song S, Kim H, Kim S. Effectiveness of smoking cessation using motivational interviewing in patients consulting a pulmonologist. Tuberculosis Respiratory Diseases. 2014;76(6):276. doi: 10.4046/trd.2014.76.6.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl B, Moleni T, Burke BL, Butters R, Tollefson D, Butler C, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Education Counseling. 2013;92(2):157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madson MB, Loignon AC, Lane C. Training in motivational interviewing: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36(1):101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madson MB, Villarosa-Hurlocker MC, Schumacher JA, Williams DC, Gauthier JM. Motivational interviewing training of substance use treatment professionals: A systematic review. Substance Abuse. 2019;40(1):43–51. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2018.1475319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Apodaca TR, Borsari B, Gaume J, Hoadley A, Gordon R, Tonigan J, Moyers T. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing process: Technical, relational, and conditional process models of change. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. 2018;86(2):140–157. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Carroll KM. Informal discussions in substance abuse treatment sessions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36(4):366–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowski AK, Owens RL, LaCaille RA, Clinton-Lisell V. A systematic review and meta-analysis of motivational interviewing training effectiveness among students-in-training. Training & Education in Professional Psychology. 2021;16(4):354–361. doi: 10.1037/tep0000363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change (Applications of Motivational Interviewing) Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(6):1050–1062. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.72.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modini M, Abbott MJ, Hunt C. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of trait social anxiety self-report measures. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment. 2015;37(4):645–662. doi: 10.1007/s10862-015-9483-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB. The relationship in motivational interviewing. Psychotherapy. 2014;51(3):358–363. doi: 10.1037/a0036910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira CSR, Huziwara EM. Motivational interviewing under a behavior analysis perspective. In: Oliani SM, Reichart RA, Banaco RA, editors. Behavior analysis and substance dependence: Theory, research, and intervention. Springer; 2021. pp. 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ostlund A, Wadensten B, Kristofferzon M, Haggstrom E. Motivational interviewing: Experiences of primary care nurses trained in the method. Nurse Education in Practice. 2015;15(2):111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecukonis E, Greeno E, Hodorowicz M, Park H, Ting L, Moyers T, Burry C, Linsenmeyer D, Streider F, Wake K, Wirt C. Teaching motivational interviewing to child welfare social work students using live supervision and standardized clients: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research. 2016;7(3):479–505. doi: 10.1086/688064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pontoppidan M, Niss NK, Pejtersen JH, Julian MM, Væver MS. Parent report measures of infant and toddler social-emotional development: A systematic review. Family Practice. 2017;34(2):127–137. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmx003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalbe CS, Oh HY, Zweben A. Sustaining motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of training studies. Addiction. 2014;109(8):1287–1294. doi: 10.1111/add.12558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BA, LeBlanc LA, Nosik MR. Compassionate care in behavior analytic treatment: Can outcomes be enhanced by attending to relationships with caregivers? Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;12(3):654–666. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00289-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollison SJ, Lee CM, Neighbors C, Neil TA, Olson ND, Larimer ME. Questions and reflections: The use of motivational interviewing microskills in peer-led brief alcohol intervention for college students. Behavioral Therapy. 2008;39(2):183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovenko I, Quigley L, Hemmeigarn BR, Hodgins DC, Ronksley P. The efficacy of motivational interviewing for disordered gambling: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Addictive Behaviours. 2015;43:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zendjidjian XY, Auquier P, Lancon C, Loundou A, Parola N, Faugere M, Boyer L. Determinants of patient satisfaction with hospital health care in psychiatry: Results based on the SATISPSY-22 questionnaire. Patient Preference & Adherence. 2014;8:1457–1464. doi: 10.2147/ppa.s67641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilcha-Mano S, Roose SP, Barber JP, Rutherford BR. Therapeutic alliance in antidepressant treatment: Cause or effect of symptomatic levels? Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics. 2015;84(3):177–182. doi: 10.1159/000379756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccala M, Menzies RE, Hunt CJ, Abbott MJ. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of death anxiety self-report measures. Death Studies. 2019;46(2):257–279. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2019.1699203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

N/A.

N/A.