Abstract

Curriculum-based measurement (CBM) is an approach to measuring student academic growth and evaluating the effectiveness of instruction (Deno, Exceptional Children, 52, 219-232, 1985) that was developed, in part, based on characteristics of applied behavior analysis. Learning to administer and use CBM data is commonly part of teacher preparation programs, but less common in behavior analysis graduate programs (Schreck et al. Behavioral Interventions, 31, 355-376, 2016; Schreck & Mazur, Behavioral Interventions, 23, 201-212, 2008). This article describes a sequence of steps that educational teams can follow to use CBM within the multi-tiered system of support (MTSS) framework. These steps include (1) selecting a CBM publisher and gathering materials; (2) practicing administering and scoring CBM; (3) administering, scoring, and comparing student scores to grade-level benchmarks; (4) using CBM data to write ambitious and realistic IEP goals; and (5) using data-based individualization. Each step is described and includes a description of a case study that is based on our experiences working with pre-service teacher candidates, and special education and behavior analysis graduate students in K–12 and after-school instructional programs.

Keywords: Academic assessment, Progress monitoring, Curriculum-based measurement, Data-based individualization, Public education

Behavior analysts have long worked in educational settings (Shepley & Grisham-Brown, 2019; Heward, 2005) and since the development of the BCBA certification, schools are increasingly seeking behavior analysts that are board certified (i.e., BCBAs). Currently, 12.19% of BCBAs report working in education (BACB, n.d.). Changes in federal policies have created increased opportunities for behavior analysis and therefore BCBAs to be incorporated into schools. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act Amendments of 1997 (IDEA) states that functional behavior assessment (FBA) must be conducted for students with disabilities that engage in challenging behavior. Additionally, public schools are implementing positive behavior interventions and support (PBIS) systems as part of their response to intervention (RtI) or multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) (Horner & Sugai, 2015; Putnam & Kincaid, 2015). Despite these positive steps, behavior analysts still struggle to find meaningful traction in public schools (Layden, 2022). For example, although IDEA mandates that FBAs are completed for students who engage in challenging behavior, it did not state who should complete them or provide guidance on how they should be completed. Although there is an extensive literature base on how to apply behavioral interventions in schools, there needs to be more literature on how behavior analysts are supported and function in this unique environment (Layden, 2022). In addition to supporting decreasing unwanted behaviors, school-based BCBAs can play essential roles in supporting students' academic achievement. The IDEA 2004 mandates that teachers use "research-based interventions, curriculum, and practices" (p. 2787). Therefore, it is important that behavior analysts working in schools are well-versed in reliable and valid academic assessments, curricula, and instructional strategies. Although this information is covered in initial or advanced special education programs, it is less common in graduate-level behavior analysis coursework (Schreck et al., 2016; Schreck & Mazur, 2008; Vladescu et al., 2022). To highlight this limitation in preparation, the BCBA 5th edition task list identifies nine skills related to behavior assessment. Preference assessment and functional analysis are specifically listed but academic assessment is not. A commonly used academic assessment used within the MTSS framework is curriculum-based measurement (CBM). CBM was developed by Deno and Mirkin (1977) at the Minnesota Institute for Research and Learning Disabilities. They were developing an intervention process called data-based program and modifications (DBPM), which was a package of procedures for establishing goals, planning interventions (with a heavy emphasis on collaboration and consultation), and progress monitoring. In their program, Deno and Mirkin outlined a variety of ways in which special education teachers could use progress monitoring data to make informed educational decisions for their students (Deno, 2003a, b). During their research, it became clear that an assessment system that was built on common principles and that used standardized procedures and rules was needed. This type of system existed in applied behavior analysis (ABA) in areas such as classroom management and social behavior but did not exist for academic content (Hosp et al., 2016). CBM procedures were based, in part, on the characteristics of ABA (Deno, 2003a, b). For example, all CBM procedures involve the direct observation of behavior and use the single-case analytical procedures of ABA. Additionally, each time CBM is administered, students’ data are graphed, and educators use systematical rules to inform instruction, which is referred to as data-based individualization (DBI; National Center on Intensive Intervention [NCII], 2013).

Data-based individualization is a systematic method of using assessment data to determine when and how to intensify intervention in reading, mathematics, and behavior. The method relies on the systemic and frequent collection and analysis of student-level data, modification of intervention components when those data indicate inadequate progress and teachers using their experience and judgment to individualize intervention. Using research-based curricula with high fidelity is critical within DBI. The DBI process begins when a team of educators decides that a student needs a more intensive and individualized intervention. The team uses ongoing progress monitoring data, most commonly CBM, and diagnostic assessment data (e.g., error analysis or functional behavior assessment) to assess the student’s response to intervention and determine when adjustments are needed. Readers will quickly see the commonalities between the methodologies used by educational teams implementing DBI and those used by BCBAs implementing and evaluating ABA intervention.

After nearly 50 years of extensive research, CBM is used across content areas including literacy, spelling, mathematics, and written expression in general and special education. Stecker et al. (2005) found that students of teachers who adapted instruction based on CBM data showed greater growth across academic areas (e.g., reading, mathematics, spelling) compared to students of teachers who did not engage in data-based decision-making and that students who completed CBM were more aware of their academic performance.

The purpose of this article is to provide a tutorial on how school-based BCBAs can use CBM and DBI within the MTSS framework when collaborating with school teams. The steps include (1) selecting a CBM publisher and gathering materials, (2) practicing administering and scoring CBM; (3) administering, scoring, and comparing student scores to benchmarks; (4) using CBM data to write ambitious and realistic IEP goals; and (5) using data-based individualization. Included in each step is a description of a case study that is based on our experiences working with pre-service teacher candidates and special education and behavior analysis graduate students in K-12 and after-school instructional programs.

The BACB® requires that BCBAs practice within their scope of competence (i.e., skillset) and scope of practice (i.e., job responsibilities), therefore the information presented in the current manuscript should be viewed as introductory. Interested readers are encouraged to seek professional development opportunities that provide high-quality training in CBM and DBI.

Curriculum-Based Measurement within MTSS

When used within the MTSS framework, CBM data can serve four functions: (1) universal screener; (2) progress monitoring; (3) diagnostic; and (4) outcome. Table 1 outlines the four functions of CBM data across the three tiers of MTSS. Within Tier 1, CBM is used as a universal screener and is administered to all students at three-time points across the academic year (i.e., beginning, middle, and end). When used as a universal screener, educators compare each student’s CBM score to grade-level benchmarks which allows educational teams to determine which students are performing adequately and which students are at risk for future learning failure and need more intensive or supplemental intervention (e.g., Tier 2). Teachers can also use CBM universal screening data to determine small groups for instruction and to determine an appropriate placement within curricula.

Table 1.

Functions of CBM Data within the MTSS Framework

| Function | Description | MTSS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | ||

| Universal Screening | To determine which students are academically on track and which students are at risk for academic failure | X | ||

| Progress Monitoring | To determine if the current intervention is resulting in adequate student progress or if the intervention needs to be modified (e.g., intensified) | X | X | |

| Diagnostic | To develop an individualized instructional plan for a student who is not making adequate progress in response to intensive intervention | X | X | |

| Outcome | To determine and document the effectiveness of an educational program | X | X | X |

Curriculum-based measurement data can be used to progress monitor within each tier of MTSS to evaluate if the instruction is effective and that students are making adequate progress towards important goals. The frequency at which CBM will be administered to students depends on which tier of support they are receiving. For example, students receiving Tier 2 or 3 intervention and support should be progress monitored at least once a week on instructional-level material and at least once per month on grade-level materials if different from the instructional level (Hosp et al., 2016). These data allow the interventionalist to determine if a student is benefiting from the instruction and if the intervention is helping the majority of students who are receiving it.

When used as a diagnostic, CBM data are used to develop an individualized instructional plan for students when progress monitoring shows that various educational support has not worked. Interventionalists can use CBM data as a diagnostic to determine what and how a student should be taught and allows for the selection of individualized expectations and teaching approaches. In most instances, CBM will be used as a diagnostic for students receiving special education services to develop their academic individualized education plan (IEP) annual goals (Bailey & Weingarten, 2019).

Lastly, CBM data can be used as an outcome measure to determine and document the effectiveness of an education program. For example, an elementary school may implement an after-school reading program and use CBM data to determine the rate of improvement for student who participated in the program. These data could be used to determine if the program benefited certain groups of students and if additional funding and resources should be allocated to the program.

Table 2 provides a task analysis of how to plan, administer, and use CBM within an educational setting. The task analysis comprises five broad steps; steps 1 through 3 include using CBM data as a universal screener and to progress monitor. The remaining steps outline how to use CBM data for students receiving special education services or rare cases when progress monitoring shows that various educational supports have not worked. Each step is explained, and a case study is provided as an example of how school professionals, including general education teachers, school psychologists, BCBAs, and special education teachers can work together to use CBM to improve academic outcomes for students.

Table 2.

Task Analysis of Using CBM within MTSS

| # | Step |

|---|---|

| 1 | Select a CBM publisher and gather materials |

| 2 | Practice administering and scoring CBM |

| 3 | Administer, score, and compare student scores to grade-level benchmarks |

| 4 | Use CBM data to write ambitious and realistic IEP goals |

| 5 | Use data-based individualization |

Step 1: Select a CBM Publisher and Gather CBM Materials

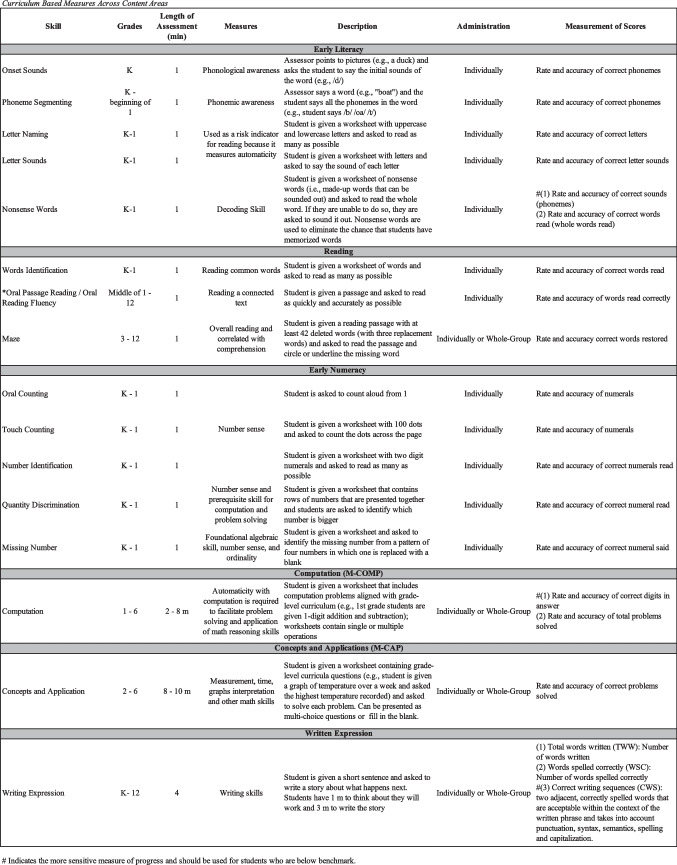

Figure 1 provides information for CBM measures across literacy, spelling, mathematics, and written expression. There is a short description of each measure, the grade(s) each measure is administered, the length of time it takes for the student to complete the measure, how the measure is administered (i.e., individually or whole-group), and the scores that are calculated on each measure. Several skills can be assessed within a content area. For example, when measuring a student’s literacy skills, the specific measures that should be used depends on the student’s grade and perhaps, more importantly, their skill level.

Fig. 1.

Curriculum-Based Measures Across Content Areas

The first step when using CBM is to identify what publisher you will use and decide if you will use an online administering system or paper-and-pencil. Over the years, several web-based CBM programs have been developed. Goos and colleagues (2012) provide a guide to selecting web-based CBM for the classroom. Popular web-based CBM platforms include AIMSweb® Plus, Acadience® Learning, Renaissance® STAR CBM, mCLASS®, and FastBridges. A web-based CBM program includes the assessment materials (e.g., reading passages, word lists, story starters) that are presented to the student on a computer or tablet. School teams can score CBM measures within the online platform and the program calculates students’ scores. Educators can create a class roster in the program and can review aggregate and student-level data. The cost of these programs varies and is typically billed per student, per year. Some schools may not have or be willing to allocate funds to purchasing online CBM systems. To our knowledge, there are five publishers that have made their CBM materials available online at no cost which are listed in Table 3. Other materials that are needed to administer CBM are the publisher’s administration manual and scoring procedures, a timer, clipboard, and pencils.

Table 3.

Free CBM materials available online

| Publisher | Content | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Literacy | Math | Writing | |

| Acadience Learning® | x | x | |

| Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS®) | x | ||

| EasyCBM.com | x | x | x |

| Intervention Central | x | x | x |

Once a teacher or team has decided which publisher to use, they will need to spend time reviewing the materials. Although the general steps of administering and scoring CBM are the same across publishers, there are variations. To ensure assessment fidelity and accurate and reliable data collection, educational teams need to carefully review the publisher’s administration guidelines and scoring procedures, and use the publisher’s grade-level benchmarks.

Case Example

Mr. Hawkins is a 1st-year teacher at an urban elementary school. The school has been through three principals in the past 5 years. The new principal has not yet decided what academic assessment and curricula will be purchased. Mr. Hawkins decided to use DIBELS® CBM materials for literacy assessment and Acadience® math CBM materials because he learned how to use these during his teacher preparation program and feels confident administrating and scoring. He downloads DIBELS® materials from their website including the Administration and Scoring Guide and the first-grade Benchmark Materials and Scoring Booklets. There are five literacy measures included in the universal screener for first grade including letter naming fluency (LNF), phoneme segmenting fluency (PSF), nonsense word fluency (NWF), word reading fluency (WRF), and oral reading fluency (ORF) (see Fig. 1 for a detailed description of each measure). To gather math CBM materials, Mr. Hawkins visits the Acadience® website and downloads the first-grade scoring booklet and student materials. The universal screener for first grade includes number identification, next number fluency, advanced quantity discrimination, missing number fluency, and computation. He plans to administer these measures using paper-and-pencil during the first two weeks of school and has recruited the help of the school psychologist and BCBA to practice, administer, score, and use the data to make instructional decisions.

Step 2: Practice Administration and Scoring

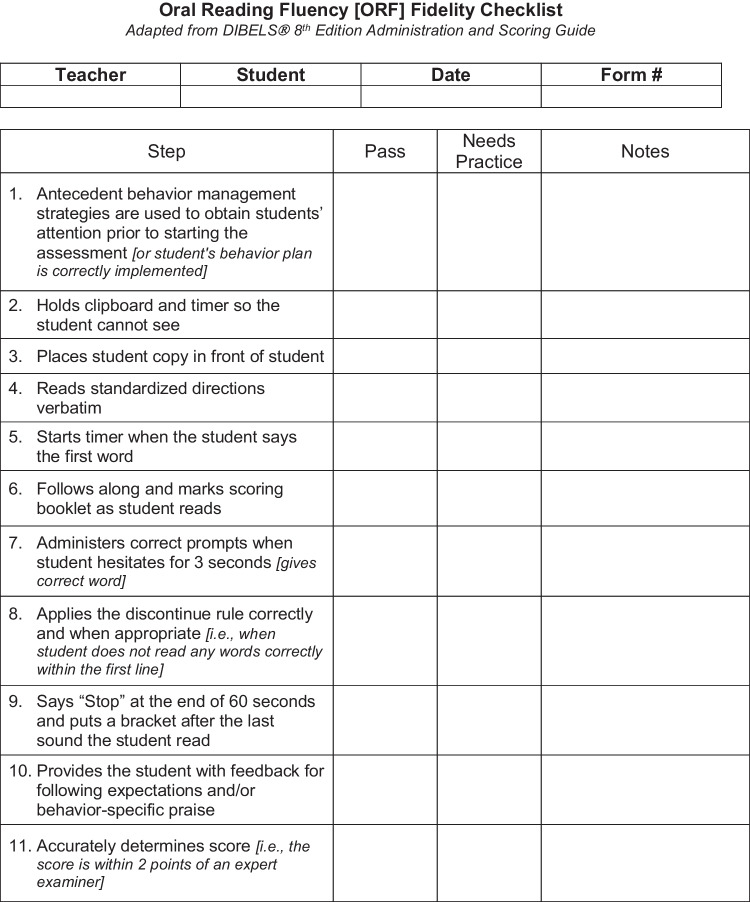

As mentioned, CBM is a standardized assessment system and data will be used to make important decisions (e.g., identifying students who need intensive support, writing IEP goals, and determining if interventions are effective) therefore it is important that measures are implemented with fidelity and data are reliable. Individuals administering CBM should practice and wait to implement it with students until they have high fidelity and reliability. Educational teams should review their publisher’s manual for fidelity checklists. These fidelity forms can be used to determine when someone can start administering CBM to students and to conduct fidelity checks throughout the school year. Behavior analysts can play an integral role in helping team members implement CBM with fidelity and collect reliable data. As part of their training program, BCBAs learn to implement effective training procedures for service delivery personnel including behavioral skills training (BST) and using performance feedback to increase assessment and intervention fidelity. In our experience, general and even special education teachers have limited or no experience with fidelity or interobserver agreement creating an opportunity for BCBAs to use their expertise within a collaborative team.

Case Example

Mr. Hawkins was trained to implement literacy CBM in his teacher preparation program, but it has been a while since he has done so. He meets with the BCBA to practice administrating and scoring the different measures. Mr. Hawkins and the BCBA review the DIBELS® 8th Edition Administration and Scoring Guide and find fidelity checklists for each first-grade measure in the appendices. Mr. Hawkins and the BCBA complete several role-playing activities and provide each other feedback. The BCBA observes that Mr. Hawkins does not implement behavior management strategies to obtain the “student’s” attention prior to reading the standardized instructions. They both have a difficult time remembering the specific prompting procedures that are provided on each measure, therefore they create laminated “cheat sheets” for each measure for quick reference. Additionally, they discuss that they will need to provide students feedback or praise when the student finishes, so they decide to modify the fidelity checklists to fit their needs. Figure 2 is the Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) fidelity checklist they created. It is based on the checklist provided in the DIBELS® materials, but they added steps 1 and 10 and provided details within each step for quick reference. They repeated this process with the other first-grade measures. Once they both scored 90% fidelity on a specific measure, they started administering the measure to students. They continued to observe each other and take fidelity data until they both scored 90% across three students. When they started administering measures to students, they encountered several scoring questions. They decided to print the scoring manual and housed it in a binder. They flagged and earmarked pages for quick reference. There were some instances in which the manual didn’t answer their questions. They started a Google document of these instances and determined how they would handle these instances across all students.

Fig. 2.

Adapted Oral Reading Fluency [ORF] Fidelity Checklist

Step 3: Administer, Score, and Compare Scores to Grade-Level Benchmarks

Once an individual can accurately implement and score CBM measures, it is time to administer to students. The administration column in Fig. 1 denotes how each measure is presented to students, individually or whole-group. Once a student’s score is determined, it is compared to the grade-level benchmarks. Although similar, each publisher's benchmark data differs. For example, DIBELS® presents ranges for each time point (i.e., beginning, middle, and end of the academic school year) and separates ranges into four groups that indicate if a student is at risk for academic failure. The four groups are (1) students whose scores are within the red range, indicating they need intensive support and are at risk for academic failure; (2) students whose scores are within the yellow range, indicating they need strategic support and have some risk of academic failure; (3) students whose scores are within the green range, indicating the Tier 1 curriculum and instruction is appropriate and are at minimal risk of academic failure; and (4) students whose scores are within the blue range, indicating Tier 1 curriculum and instruction is appropriate and have a negligible risk for academic failure. General education teachers can use beginning-of-the-year universal screener data to form instructional groups, identify students who need more intensive support, and select a starting place in the core curriculum. For students who are at risk for academic failure and receiving special education services, CBM data are used to develop annual IEP goals, which is described in step 4.

Case Study

Mr. Hawkins, the school psychologist, and BCBA finished administering and scoring the universal screeners within the first three weeks of school. They start by calculating a composite score for each student. Next, students are placed in four groups by comparing their composite scores to the DIBELS® grade-level benchmarks which are available at https://dibels.uoregon.edu. To be at minimal risk for academic failure (green range), a student’s composite score needs to be at least 330. The team also compares student’s scores on specific measures (e.g., PSF, NWF) to grade‐level benchmarks. For example, to be considered at minimal risk for academic failure (green range), a student needs to read between 10–34 words correctly in 1 minute with at least 67% accuracy on the ORF measure. Tykese, a student in Mr. Hawkins’ class, received a composite score of 343 which placed him in the green group (i.e., minimal risk for academic failure) and will be considered the Tier 1 (or core curriculum) group. Another student in Mr. Hawkins’ class, Lebron, received a composite score of 212, placing him in the intensive support group. When given the ORF measure, Lebron read three words correctly in 1 minute with 25% accuracy, which placed him in the red group indicating he needs intensive support and is at risk for academic failure. The team shares the class‐wide data and groups with the special education teacher.

Step 4: Use CBM Data to Determine Ambitious and Realistic Goals

If a student has been identified as needing intensive intervention, educators use multiple sources of information to develop a comprehensive understanding of a student's strengths and needs (McLeskey et al., 2017) including CBM data to develop short‐term goals and to develop the student’s IEP goals. For students who need more intensive intervention, teams need to determine the most appropriate measure to develop the IEP goals and to progress monitor. This is not always a straightforward process if the student is well below the grade‐level benchmark because some measures will not be sensitive enough to capture growth, which may result in a false positive determination. For example, if a first‐grade student is reading two words correctly within 1 minute on ORF, it would be inappropriate to use ORF to progress monitor or to develop an IEP goal. Using ORF to progress monitor would be insensitive to intervention effects because an appropriate intervention would teach early literacy skills (e.g., phonics) and it is unlikely that a student’s ORF score would increase, even if the intervention (or curriculum) was effective.

Once the appropriate measure has been selected, the team will need to collect additional baseline data. For example, when using literacy CBM (e.g., ORF, NWF) to write IEP goals, the student is given the same measure (ORF) three times, and the median score is the student's baseline score. Once the student’s baseline performance is known, the team must select an ambitious and realistic performance criterion (goal). Research has established three valid approaches to setting a goal using CBM data: (1) using middle‐ or end of‐the‐year benchmarks; (2) national norms for the rate of improvements (ROI); and (3) intra‐individual framework. Using end‐ or middle‐of‐the‐year benchmark scores is the most straightforward approach to setting a goal and may be appropriate for students in early grades or who are performing close to grade level. For students with intensive academic needs using benchmarks or national norms may result in unrealistic goals. In these cases, the intra‐individual framework can be used. This approach uses the student’s previous growth rate to calculate a realistic and individualized goal. To do so, six to nine data points need to be collected to identify the student’s baseline ROI or slope for the target skill. Because the student’s performance is being compared to their previous performance and not a national or local norm, enough data must be collected to demonstrate the student’s existing performance level and slope. To set an appropriate goal, teams should use the following formula: slope * 1.5 * # weeks + baseline score.

Case Study

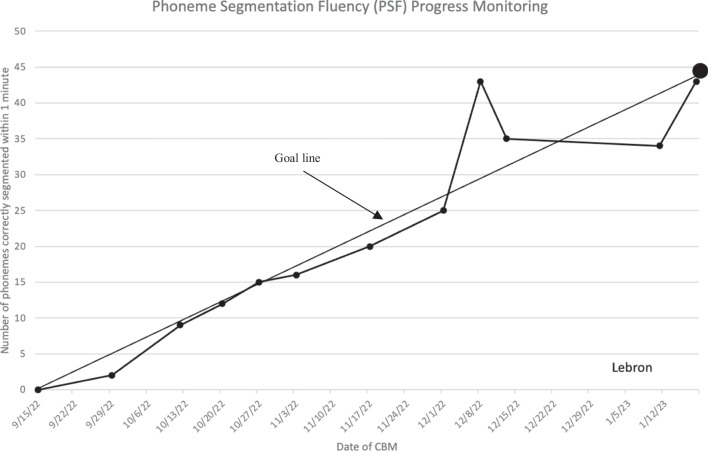

Mr. Hawkins shared Lebron’s CBM data with the special education teacher, who used the data to write two IEP goals; one for phoneme segmenting fluency (PSF) and another for nonsense word fluency (NWF) correct letter sounds (CLS), which is the more sensitive measure for NWF, compared to Words recoded correctly (WRC). They determined it was not appropriate to use ORF because Lebron scored zero on the two early literacy measures (i.e., PSF and NWF) and read three sight words (i.e., words that cannot be decoded) during ORF. Most students will not increase their score on ORF until early literacy skills, like those assessed on PSF and NWF, are learned. Lebron’s PSF goal was, “When given a first-grade standardized phoneme segmenting fluency (PSF) curriculum-based measure, Lebron will correctly segment 45 phonemes within 1 minute by spring benchmarking” (Bailey & Weingarten, 2019; Hosp et al., 2016).

Step 5: Data-Based Individualization

As described above, the DBI process is used to support students who need intensive and individualized support. The DBI process does not occur in isolation, it is used in addition to the interventions that a student is receiving within Tier 1. DBI may be used for students requiring intensive intervention in one skill area (e.g., oral reading fluency) but receiving core instruction in other areas (e.g., early literacy; NCII, 2013).

Within DBI, an evidence-based curriculum/intervention is implemented with fidelity and educators frequently progress monitor (e.g., weekly) to determine if a student is responsive to the intervention. If the student is responsive, as indicated by an upward trend in CBM scores, students continue to receive intensive intervention and support or return to core instruction depending on the rate and duration of response. If a student’s scores indicate that they are not responding to intervention, additional steps are taken such as administrating diagnostic assessments or adapting interventions based on observations.

Behavior Analysts use single-case research methodology including visual analysis at the student level to determine if interventions are effective. Educational teams use similar methodologies to analyze CBM data to evaluate if academic interventions are effective at the student-level. The two strategies to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions on student progress are (1) the data point decision rule and (2) the trend line decision rule. These rules or guidelines are designed to assist school teams to determine whether a student is making adequate progress and, if they are not, to make instructional changes. When using the data point decision rule, decisions are based upon whether a student’s CBM data, across time, are above or below the goal line. The Four-Point Method (The IRIS Center, 2015) is an easy method for examining the relationship between the four most recent data points and the goal line; if the four most recent data points are on or above the goal line the student is demonstrating improved progress and the current instructional program should continue. If the four most recent data points are below the goal line or are variable, it suggests that further diagnostic assessment or evaluation is needed. Diagnostic data may be collected through various formal and informal approaches and assists teams to determine if a lack of progress is a result of behavioral factors (e.g., the student engaging in problematic behavior), academic factors (e.g., the student is missing a pre-requisite skill), or is related to the specifics of the intervention. The CBM rules are like the rules BCBAs use when evaluating student-level data for skill acquisition programs (e.g., Kipfmiller et al., 2019).

The trend line decision rule is more complex. When using the trend line rule, the trend line must be calculated and compared to the goal line. There are four general procedures (i.e., ordinary least squares regression [OLS], quarter-intersect, split-middle, and Tukey) used to calculate the trend line within the CBM literature. Across all of the trend line decision rules procedures, the slope (i.e., steepness) of the line drawn is meant to represent a student’s estimated rate of growth. This estimate is compared to the goal line to make instructional decisions in much the same way as using the data point decisions rule. If the slope of the trend line is less than the slope of the goal line, a more intensive intervention should be implemented. If the trend line is greater than the goal line, the goal is increased and/or the intervention intensity is decreased. And finally, if the slope of the trend line is similar to the slope of the goal line the current intervention should be maintained.

Case Study Example

When Mr. Hawkins started the school year, he was not provided a Tier 1 Literacy Curriculum. He worked with the school psychologist, BCBA, and special education teacher to decide on a core curriculum. After conducting research, they decided to purchase Enhanced Core Reading InstructionTM (ECRI). They selected this curriculum because it was supported by research, was rated as having “convincing evidence” by the National Center on Intensive Intervention (NCII), was aligned with common core standards, and was cost-effective. They approached their principal who agreed to purchase the program and use the data from the academic year to determine if other classrooms would use the curriculum. Mr. Hawkins implemented ECRI with all students, and the special education teacher implemented additional lessons in combination with individualized interventions (e.g., token economies, small-group, or individual instruction) with students who scored in the red and yellow groups (which included students with IEPs). Mr. Hawkins and the team used DIBELS® CBM universal screeners again in the middle-of-the-year (MOY) and at the end-of-the-year (EOY). Lebron received ECRI during core instruction and in the resource room with the special education teacher for two, 30-minute lessons each week. The special education teacher used DIBELS® progress monitoring materials to determine if the individualization and two additional lessons each week resulted in increased skills. Figure 3 is a sample PSF progress monitoring graph. By MOY benchmarking, Lebron's PSF scores increased from 0 to 43 which placed him in the yellow range indicating he went from at risk for academic failure to some risk for academic failure. His NWF correct letter sounds (CLS) increased from 0 to 43, meaning he went from at risk to minimal risk. A similar pattern was observed in Lebron’s ORF scores. His ORF scores increased from 3 to 10 words read correctly in 1 minute with 75% accuracy. The team decides to continue with the current plan and when Lebron achieves his PSF goal, they will review assessment data and determine next steps.

Fig. 3.

Sample Phoneme Segmentation Fluency (PSF) Progress Monitoring Graph

Conclusion

Curriculum-based measurement (CBM) is an approach to formative assessment that measures student academic growth along with evaluating the effectiveness of instruction in the classroom (Deno, 1985). Although commonly part of teacher preparation programs, BCBAs may not receive systematic or intensive instruction on how to use CBM within the MTSS framework. In this article, we provided a description of CBM and how it can be used within the MTSS framework. Additionally, we provide case study examples based on our experiences instructing special education teacher candidates, and behavior analysis and special education graduate students in K-12 settings and after-school tutoring programs. By being knowledgeable in the purpose and use of CBM, school-based BCBAs can be collaborative, helpful members of MTSS teams, and can support general and education teachers to administer and use CBM data to inform instruction.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or nonfinancial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bailey, T. R., & Weingarten, Z. (2019). Strategies for setting high-quality academic individualized education program goals. Washington, DC: National Center on Intensive Intervention, Office of Special Education Programs, U.S. Department of Education.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (n.d.). BACB certificant data. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/BACB-certificant-data/

- Deno S. Curriculum-based measurement: The emerging Alternative. Exceptional Children. 1985;52:219–232. doi: 10.1177/001440298505200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deno S. Curriculum-based measurements: Development and perspective. Assessment for Effective Intervention. 2003;28(3–4):3–12. doi: 10.1177/073724770302800302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deno S. Developments in curriculum-based measurement. The Journal of Special Education. 2003;37(3):184–192. doi: 10.1177/00224669030370030801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deno S, Mirkin PK. Data-based program modification: A manual. Council for Exceptional Children; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Goos M, Watt S, Park Y, Hosp J. A guide to choosing web-based curriculum-based measurement for the classroom. Teaching Exceptional Children. 2012;45(2):34–40. doi: 10.1177/004005991204500204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heward WL. Twelve reasons why ABA is good for education and why those reasons have been insufficient. In: Heward WL, Heron TE, Neef NA, Peterson SM, Sainato DM, Cartledge G, Gardner R, Peterson LD, Hersch SB, Dardig JC, editors. Focus on behavior analysis in education: Achievements, challenges, and opportunities. Pearson; 2005. pp. 239–251. [Google Scholar]

- Hosp M, Hosp J, Howell K. The ABCs of CBM: A Practical Guide to curriculum-based measurement. 2. The Guilford Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Horner RH, Sugai G. School-wide PBIS: An example of applied behavior analysis implemented at a scale of social importance. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;8(1):80–85. doi: 10.1007/s40617-015-0045-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 (2004).

- Kipfmiller KJ, Brodhead MT, Wolfe K, LaLonde K, Sipila ES, Bak MY, Fisher MH. Training front-line employees to conduct visual analysis using a clinical decision-making model. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2019;28:301–322. doi: 10.1007/s10864-018-09318-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Layden SJ. Creating a professional network: A statewide model to support school-based behavior analysts. Behavioral Analysis in Practice. 2022;16:51–64. doi: 10.1007/s40617-022-00700-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeskey, J., Barringer, M-D., Billingsley, B., Brownell, M., Jackson, D., Kennedy, M., Lewis, T., Maheady, L., Rodriguez, J., Scheeler, M. C., Winn, J., & Ziegler, D. (2017, January). High-leverage practices in special education. Arlington, VA: Council for Exceptional Children & CEEDAR Center. © 2017 CEC & CEEDAR.

- National Center on Intensive Intervention . Data-based individualization: A framework for intensive intervention. Office of Special Education, U.S. Department of Education; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R, F. & Kincaid, D. School-wide PBIS: Extending the impact of applied behavior analysis. Why is this important to behavior analysts? Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;8(1):88–91. doi: 10.1007/s40617-015-0055-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreck KA, Mazur K. Behavior analyst use of and beliefs in treatments for people with autism. Behavioral Interventions. 2008;23:201–212. doi: 10.1002/bin.264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schreck KA, Karunaratne Y, Zane T, Wilford H. Behavior analysts’ use of and beliefs in treatment for people with autism: A 5-year follow-up. Behavioral Interventions. 2016;31(4):355–376. doi: 10.1002/bin.1461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shepley C, Grisham-Brown J. Applied behavior analysis in early childhood education: An overview of policies, research, blended practices, and the curriculum framework. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(1):235–246. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-0236-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecker PM, Fuch L, Fuchs D. Using curriculum-based measurement to improve student achievement: Review of research. Psychology in the Schools. 2005;42(8):795–819. doi: 10.1002/pits.20113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The IRIS Center. (2015). Intensive intervention (part 2): Collecting and analyzing data for data-based individualization. Retrieved from https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/dbi2/

- Vladescu, J. C., Breenman, S. L., Cox, D. J., & Drevon, D. D. (2022). What’s the big IDEA? A preliminary analysis of behavior analyst’s self-reported training in and knowledge of federal special education law. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 15, 867–880. 10.1007/s40617-021-00673-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.