Abstract

Many have suggested that a compassion-focused approach to applied behavior analysis (ABA) services may improve provider–client therapeutic relationships and has the potential to improve program acceptability and clinical outcomes experienced by our clients. In this article, radical compassion is defined and explored as a foundational approach to the implementation of ABA, with special emphasis on practical applications in the area of service delivery for families living with autism. In this framework for care, compassion is offered as a measurable repertoire and as a philosophical guidepost for future developments in the profession. This article explores preliminary tenets of compassion-focused ABA and their implications for practice. This approach is offered in the hope of moving the field toward a future of improved acceptability and sustainable consumer preference.

Keywords: compassion, compassion-focused applied behavior analysis, radical compassion

Behavior analysts are well-poised to serve society by using our compassionate science to tackle problems of social significance. Compassion has been defined as overt action toward the alleviation of another’s suffering (Gilbert, 2009; Taylor et al., 2019). Given that society’s greatest problems indicate some experience of individual or collective suffering, a science aimed at serving the world through constructing environments that allow all organisms to thrive (Skinner, 1953) is a science that embodies compassion. Therefore, we assert that applied behavior analysis (ABA) is philosophically a compassionate science. However, stakeholders have critiqued the application of ABA with the concern that our science is not always applied in a compassionate manner (Taylor et al., 2019; Autistic Self Advocacy Network, n.d.). In an effort to remain consistent with our compassionate foundations, this article discusses how ABA supports for autistic people can be implemented in a manner that further brings compassionate repertoires into focus.

The discussion of serving the world and alleviating suffering is not a trend or novel concept; seminal literature addressing applications of reinforcement, considerations involving aversive contingencies, and demonstrations of social validity have been thoroughly laid out by the founders and prominent disseminators of our science and practice (Skinner, 1953; Wolf, 1978; Goldiamond, 1974; Sidman, 1989). Researchers in ABA have highlighted the need for increased fluency in compassion repertoires for behavior analysts (Taylor et al., 2019; LeBlanc et al., 2019; Rohrer et al., 2021). In addition, the Behavior Analyst Certification Board(R) (BACB(R)) underscored the foundational nature of compassion in practice, by releasing an updated Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts (BACB, 2020), which expanded upon earlier guidelines related to compassionate practice, client well-being and dignity, and other related guiding principles.

As an extension to these resources, the purpose of the present article is twofold: to extend the discussion on behavior analytic definitions of compassion-focused care, and to propose preliminary practice parameters for its application. We first offer a synthesis of behavior analytic definitions of compassion, followed by a set of tenets to guide practice of compassion-focused application, informed by feedback from the stakeholder communities. Next, we offer job aides that may assist behavior analysts in applying these proposed tenets, through client interview forms and a list of prompts for ensuring compassion has been considered in the authoring of behavior intervention plans. Given the relation between compassionate repertoires and critical outcomes measures (Bonvicini et al., 2009; Sinclair et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2019), it is our hope that this discussion and included job aides will equip behavior analysts with practical tools for applying the requirements outlined in the Core Principles of the Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts (BACB, 2020).

An Exploration of Operational Definitions

In the health-care literature, compassion is a feature of care that is associated with greater consumer preference, improved patient outcomes, and is incorporated into the ethical codes of multiple disciplines (Sinclair et al., 2017). In a systematic review of biomedical literature examining studies that included overt physician actions, Patel et al. (2019) identified characteristics of physician behavior that patients associated with empathy and compassion. Pavlova et al. (2022) conducted a systematic review of biomedical literature (n = 74,866 physicians) that examined predictors of physician compassion, empathy, and related constructs (referred to as ECRC in Pavlova’s article, p. 1). Pavlova et al. defined compassion as “noticing the suffering of another and being motivated to alleviate it.” Medical literature provides useful first steps; however, biomedical literature is often mentalistic (e.g., “being motivated”), and the physician behaviors, when observable, are defined topographically. In order to extend the valuable work that has been emerging in the medical literature into behavior analytic practice, behavior analytic definitions are needed.

Seminal literature in ABA has consistently upheld compassion as a core value, though not in those words. In Science and Human Behavior, Skinner (1953) described a world where freedom from violence, poverty, and suffering was possible. In Wolf’s (1978) treatise on ABA “finding its heart” through social validity, he encouraged behavior analysts to ask clients about their values, preferences, and priorities, in order to collaborate with them in identifying goals, procedures, and outcomes that they genuinely care about. Contemporary articles have taken these founding principles and discussed compassion repertoires explicitly.

Recent articles in the behavior analytic literature (e.g., Taylor et al., 2019; LeBlanc et al., 2019; Leblanc et al., 2021) have achieved critical development toward a framework of discussing and practicing compassion in behavior analytic terms. In their article on the relationship between compassion repertoires and client outcomes, Taylor et al. (2019) offered definitions for sympathy, empathy, and compassion. These separate definitions are especially useful, as medical literature (as discussed in Pavlova et al., 2022) tends to group these together as “related constructs.” Although separate processes, the medical literature consistently pulls empathy and compassion into the same study (Bonvicini et al., 2009; Sinclair et al., 2017; Patel et al., 2019; Pavlova et al., 2022); thus, the processes appear to be closely related. In the following section we will explore definitions in the behavior analytic literature of both empathy and compassion, which will lay the groundwork for developing strategies for practical compassionate action in the remainder of the article.

Behavior Analytic Definition of Empathy

Empathy has been described as the act of perceiving an experience from the other person’s perspective, while understanding the other’s emotional response to that experience (Taylor et al., 2019). Taylor’s definition alludes to perspective-taking as a behavioral repertoire. Perspective taking has been explored through a behavior analytic lens, referred to as deictic relational framing (Vilardaga, 2009). Vilardaga, referring to the original Greek root words for empathy, defined empathy as “being in some sort of suffering, feeling, or emotion” and “a form of perspective taking that referred to the psychological process of objectively perceiving another person’s situation” (p. 1). In lay terms, perspective-taking occurs when an individual identifies similarities between themselves and another person in order to establish commonality. In relational frame theory terms, empathy likely involves relating oneself to another (i.e., deictic relating) in terms of similarity (i.e., relating in terms of coordination; Vilardaga, 2009).

Behavior Analytic Definitions of Compassion

Although perspective-taking and empathy may sometimes occur solely at the covert level, compassion as defined behavior analytically requires a demonstration of overt behavior. Taylor et al. (2019) offered a definition of compassion that reflects this action focus: compassion converts empathy into action for the purpose of alleviating suffering. Building upon this definition, Leblanc et al. (2021, p. 5) offered an orientation to function by framing compassionate behavior as a “learned response to the stimulus class of aversive behaviors.” This definition is an important contribution, because it alludes to the reinforcement contingencies of both the person engaging in compassion and the recipient of the compassionate behavior. This analysis of the two-person interaction involved in compassion is roughly analogous to Skinner’s conception of verbal behavior as consisting of an interaction between speaker and listener (Skinner, 1957). Likewise, we can expect a learning history exists for the actor in the compassionate interaction; it may be that removal of suffering on the part of the recipient functions as negative reinforcement for the actor. For example, if it is aversive for the actor to see the recipient suffering, then relieving that suffering may decrease an aversive stimulus for the actor. As an alternative, if seeing another human appearing happy is positively reinforcing for the actor,, then their compassionate behavior may result in positive reinforcement via an improvement in the recipient’s condition.

In 2020, the BACB released an updated ethics code (BACB, 2020, effective 2022), which included multiple enhancements from the previous version. These included the addition of Core Principles. The first and second core principles are highly relevant to the present article. Core Principle 1 states, “Behavior Analysts work to maximize benefit and do no harm by . . . focusing on short- and long-term effects of their professional activities” (BACB, 2020, p. 4). This additional language is helpful to guide practicing behavior analysts in the focus of treatment. In the effort to create benefit and avoid harm, behavior analysts may often encounter the principles of short-term versus long-term benefits and harms. We propose that compassion, as an action aimed at the alleviation of suffering, may be said to minimize both short- and long-term suffering by minimizing both short and long-term contact with aversive stimulation. Examples of short-term suffering might include momentary distress, pain, or discomfort; examples of long-term suffering might include overly restrictive placements, social isolation, or overall poor quality of life.

To behave as compassionately as possible, the behavior analyst likely needs to carefully assess how to balance mitigating both short- and long-term suffering to the greatest extent possible. For example, toothbrushing may be distressing to a child today, whereas tooth decay will be painful and debilitating in the future. If one only focuses on eliminating short-term suffering, one might simply not ask the child to brush their teeth, which would result in long-term suffering of tooth loss. If one only focused on preventing long-term suffering, one might use overly intrusive procedures in order to force compliance with toothbrushing today. The most compassionate approach that balances both short- and long-term concerns might be to design an intervention procedure that focuses on positive reinforcement and antecedent interventions, but that is also effective at helping the child learn to brush their teeth. This effort to balance minimizing both short- and long-term distress is roughly analogous to classic discussions of how clients have a right to treatment that is both humane and effective (Van Houten et al., 1988). However, the position we are proposing in this article is that the right to be treated humanely is equally important to the right to effective treatment. It may be common to hear that ABA providers provide the least intrusive treatment that is effective (Van Houten et al., 1988), whereas our analysis of compassion suggests it is our duty to provide the most effective treatment that is humane.

The definitions of compassion described above are inherently functional, not topographical, so it is worth noting that compassionate practitioner behavior will likely need to look very different across different clients. Just as each client and caregiver has unique needs, preferences, and values, our attempts at engaging clients compassionately will need to be customized to each client. The same procedure that may alleviate suffering for one client may cause suffering for another. For example, one autistic child may genuinely appreciate a hug from an ABA therapist during a session and that hug may have the function of decreasing how aversive the overall session is for that child. A different child may not find that physical contact positively reinforcing and therefore a hug may not make the ABA session more compassionate for them. Compassionate clinician behavior will then require paying careful attention to the client’s response to the clinician’s attempts, so that those attempts can be adjusted on a moment-to-moment basis to be most compassionate. It is also likely equally important to distinguish between the function of the behavior for the clinician (i.e., attempting to alleviate suffering for the client), versus the actual functional effect of that clinician’s behavior on that client. Put another way, the intention of our behavior must be considered separately from the impact it has on others. Like everything else we do in ABA, the function of compassionate behavior must be analyzed from both the standpoint of the therapist and client.

In the following sections of the article, we propose basic tenets of application of compassion-focused care, and these are offered through a lens of radical compassion. The term “radical” compassion (Bstan-‘dzin-rgya-mtsho, Dalai Lama XIV, 1995) is based on the denotation of the word radical as meaning “from the root,” where suffering is the root of problems of social significance, and therefore acts to alleviate them are the foundation of a science aimed at addressing society’s problems. From a radical compassion perspective, autistic clients of ABA services deserve compassion simply because they are human beings, not because suffering is inherent in autism, in particular. This phrase also dovetails with radical behaviorism, the basic philosophical position that a science of behavior includes all the actions of organisms, both overt and covert, including the behavior of the scientist, themself (Skinner, 1945). Taken together, we suggest that radical compassion is a worldview, wherein all humans, including clients, caregivers, colleagues—and even ourselves—experience suffering, and are fundamentally deserving of compassion.

Preliminary Tenets of Compassion-Focused Care

In order to move from a behavior analytic conceptual discussion of compassion toward further evolving compassionate practices in our daily work with clients, a set of parameters or resolutions to guide compassion-focused care may be useful. To that end, preliminary tenets of compassion-focused ABA, drawn from behavior analytic literature, examining ethical considerations and treatment protocols, and heavily rooted in the Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts (BACB, 2020), are proposed below. We believe that these tenets, taken together, may be useful for helping develop new practices and refine existing practices based upon a foundation of radical compassion. These are not offered as rigid prescriptive “rules,” but rather as practical guideposts, as interpretations of the ethical code, that we hope practitioners will find useful as focal points for treatment design and evaluation. These tenets and sample corresponding behaviors are described in Table 1, and we expand upon each in the following section of the article, reflecting on insight from existing literature and suggesting applications in practice.

Table 1.

Tenets of Compassion Focused ABA

| Tenet of Compassion-focused ABA | Brief Summary | Sample Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Noncontingent Compassion | Given that alleviation of suffering is central to achieving socially significant behavior change, compassion is central to high quality delivery of ABA, and therefore acts of compassion should be offered noncontingently throughout instructional sessions | Offer noncontingent access to affection and comfort stimuli from caregivers and staff |

| Positive Reinforcement | ABA programs should be rooted in the delivery of meaningful, sustainable positive reinforcement, avoiding use of aversive or coercive contingencies in the therapeutic environment | Program to include client’s priorities and values |

| Acquiring Assent | Practitioners should actively monitor for assent throughout delivery of ABA programs, and should refrain from instruction at such times as assent is withdrawn | Monitor for operationally defined assent and withdrawal of assent |

| Protecting Dignity through Least Restrictive Practice | Practitioners should avoid engaging with clients in ways that provoke unnecessary escalation and should use least restrictive methods for safely assisting clients in deescalation | Prevent severe escalations by honoring precursor behavior; eliminate use of non- emergency restraints |

Table depicting tenets of compassion-focused care (left column), brief summary of each tenet (middle column), and sample behaviors of the clinical team (right column).

Exploring Applications of the Tenets

Although the offered applications are focused solely on clients receiving autism services, we believe these tenets extend to interactions with parents/caregivers, colleagues, and may be useful in applications of self-compassion; however, these extensions are beyond the scope of the current article.

Tenet 1: Behavior Analysts Practice Noncontingent Compassion

Behavior analysts noncontingently work to create a supportive and therapeutic environment for the client, based on the client’s needs. Given that some measure of suffering is consistent across the human condition (Anderson, 2014), and therefore human clients of behavior analysis are likely to experience suffering, we contend that acts of compassion are so integral to effective practice of ABA that acts toward alleviation of suffering should be offered noncontingently. That is, a client should not be expected to perform to a certain criterion to be deserving of caring interaction. An act of compassion is not earned; rather, it is a response to an observation of suffering.

Throughout the literature, behavior modification procedures have used positive reinforcement delivered contingent upon when a client has earned it, often through demonstrations of compliance or task completion (Lalli et al., 1999). Although it is true that delivering positive reinforcement contingently is generally the most effective procedure for building skills (Anderson et al., 1996), there may be several types of interactions or tangible stimuli that may not be the best choice for use as reinforcers, such as the affection of a parent or comfort stimuli, such as a security blanket.

We acknowledge there are examples of behavioral emergencies when one’s first response may need to be oriented toward safety, rather than noncontingently giving comfort stimuli. For example, if a large, strong child is trying to harm their parent, the parent’s first priority should be to protect the physical safety of everyone involved. The suggestion that demonstration of affection be offered noncontingently is not a recommendation that safety be compromised, only that expressions of care, concern, or affection need not be contingent upon compliance. Although examples of this nature are reality for some, much of the day-to-day work in applied behavior analysis does not involve behavioral emergencies. We suggest that comfort and affection should be offered noncontingently throughout sessions, because a client has a right to reassurance and connection with their parent at any time, and removal of comfort stimuli could create unnecessary distress. Comfort stimuli are only one possible example of the need for noncontingent compassion. From a radical compassion perspective, the following question should be able to be answered in the affirmative during every single ABA session: Does the client feel safe and cared for? If the answer is not an obvious “Yes,” that is an opportunity for us to identify how we can reengineer sessions so that the client experiences ABA sessions as more compassionate.

Tenet 2: Behavior Analysts Prioritize Positive Reinforcement

The BACB Ethics Code item 2.14 states that behavior analysts select, design, and implement behavior-change interventions that “prioritize positive reinforcement procedures” (BACB, 2020, p. 12). From the standpoint of compassion-focused care, positive reinforcement is not one-of-many potential procedures; it is the central purpose and foundation of ABA services. Rather than focusing on reducing “inappropriate behavior,” behavior analysts assume all existing behavior is functional and use positive reinforcement to build upon and expand existing repertoires (Goldiamond, 1974).

Emphasizing positive reinforcement has been at the foundation of the behavior analytic world view since the beginning (Skinner, 1953), is enshrined in the BACB Professional and Ethical Conduct Code for Behavior Analysts (BACB, 2014, 4.08), and is expanded upon under the Core Principles of the updated Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts (BACB, 2020). We further emphasize this moral imperative by taking the position that encouraging client engagement maintained by durable, positive reinforcement is a minimum requirement for engaging others compassionately, because it lessens reliance on aversive contingencies while still effecting meaningful long-term outcomes. Empowering others to change their lives by helping them orient their own behavior around socially valid, meaningful sources of positive reinforcement is a critical step toward client-affirming engagement, deep caregiver and client satisfaction, and likely improved resilience (Taylor et al., 2019; Hofmeyer et al., 2016).

It might be reasonable to consider that, if the manner in which we arrange the environment motivates strong escape responses by our clients, then, by definition, we are not arranging strong enough positive reinforcers for engagement. This concern for our field is not novel. Although we acknowledge that negative reinforcement and contingencies of coercion are common in the natural physical and social environment (Sidman, 1993), we align with Sidman’s view that behavior analysts are uniquely trained and qualified to effect meaningful change through use of positive reinforcement, and that we should strive to avoid use of aversive or coercive contingencies in our therapeutic environments. We should therefore endeavor to enhance reinforcement contingencies aligned with and in support of building generalized, beneficent positive reinforcement for our clients. In doing so, we may minimize potential for short-term distress or discomfort and potential (typically unmeasured) long-term psychological effects. Although the limitations of coercion have been discussed thoroughly in the literature over decades (Goldiamond, 1974; Sidman, 1989), longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate the balance of both short and long-term outcomes associated with positive reinforcement as the main focus.

Tenet 3: Behavior Analysts Acquire Assent

Behavior analysts document methods for assessing caregiver consent and client assent at intake and throughout the treatment process (BACB, 2020, 2.11, p. 11). Behavior analysts monitor for withdrawal of assent and carefully consider when we may be unintentionally coercing clients to give assent (Goldiamond, 1974). A client may give and withdraw assent repeatedly throughout the course of treatment, and within a single session. Behavior analysts identify the desired results of treatment in collaboration with the client and caregivers (BACB, 2020; Pritchett et al., 2021; Sylvain et al., 2022; Wolf, 1978).

In order to uphold self-determination and collaboration (BACB, 2020, p. 4), assessing assent during initial social validity assessment and continuously through service delivery, is a critical feature of compassion-focused practice. Assent is an active process by which the client, themselves, indicates through their behavior that they are willing to engage in treatment. The Ethical Code for Behavior Analysts (BACB, 2020) offers a glossary to clarify the definitions for consent and assent, and to make a clear distinction between client (the direct recipient of care) and the stakeholder (family member, community member, etc.). Prior to clarification in language defining “stakeholders” of ABA in matters of consent (BACB, 2020), it may have been common for behavior analysts practicing in autism care to interpret caregiver permission synonymously with consent to treatment. The updated code language clarifies the goal to create opportunities for clients to assent to care, which is more consistent with biomedical conceptualizations of consent and assent. An American Academy of Pediatrics committee on bioethics (Bartholome, 1995) contextualized consent as an ethical principle of respect for the patient as a person with basic rights to know or to be informed and to exercise the right of autonomy or self-determination. The article clarifies that caregivers do not truly give informed consent for their children because the caregiver is not the patient. Rather, in the event a young or cognitively affected client is unable to give informed consent, the caregiver is able to give informed permission, with the client giving assent whenever feasible.

Client assent as a defined practice is a relatively new concept in the field of ABA. A recent review of assent in ABA research found that fewer than 1% of articles published in behavior analytic journals reported assent procedures (Morris et al., 2021). It is possible that some researchers incorporated informal assent procedures in their research and/or did not report assent procedures in the publications resulting from their research, and so the true prevalence of assent in ABA research could be higher. However, if fewer than 1% of behavior analytic research articles report assent, it seems likely that there is room for improvement, and additional research on how often assent is incorporated into real-life practice would be useful.

A compassion-focused approach should consider client assent in all aspects of daily programming and treatment interactions to address the ethical principle of respect for client autonomy and basic rights (BACB, 2014, 2.05a, 4.02, 4.04). We should begin with the assumption that all clients have some right to bodily autonomy, which should guide our evaluation of intrusiveness of prompts and procedures, and even young children are capable of assenting, via vocal permission or other nonvocal means of communication. In each individual client and each unique context, it is the job of the clinician to carefully consider what assent looks like for that client. For those clients that do not engage in reciprocal vocal communication, clinicians should still explain all aspects of intervention and ensure they have gathered client assent in whatever modality is appropriate to the client before implementing treatment (BACB, 2020, p. 11). Emerging literature has demonstrated that assessing treatment preferences (e.g., Hanley, 2010) and engaging clients through social approach without extinction (Shillingsburg et al., 2019) are possible even without reciprocal vocal communication repertoires. Although outlining the nuances, considerations, and tactical details of assent protocols is beyond the scope of this article, assessing and honoring assent and assent-withdrawal is a continuous process that can occur throughout sessions, and we can proceed from the perspective that clients have a right to withdraw assent to treatment, which at times may limit our ability to intervene unless safety risks are present.

Assent-based procedures may be especially important for individuals who exhibit severe challenging behavior. Recognizing assent withdrawal and reinforcing precursor escape-motivated behavior immediately may allow us to respect client dignity and prevent escalation that otherwise could have required physical interventions. For example, if a client has a repertoire of escape-maintained behaviors that include whining, screaming, hitting, and self-injury, and the less-dangerous behaviors often occur first, then those behaviors can be reinforced with escape immediately, thereby decreasing the establishing operation that may evoke the more-dangerous topographies of behavior (Rajaraman et al., 2021b). If behavior is not successfully prevented from escalating, clinicians should consider prioritizing and honoring withdrawal of assent over adherence to procedures, while also prompting functional communication, in order to prevent further escalation (Rajaraman et al., 2021b). This is an applied example of weighing short- and long-term effects of treatment. From the perspective of honoring assent, it may be beneficial to assume that the default strategy is to reinforce any communicative behaviors, including “challenging” behaviors, and only progressing toward requiring more elaborate and socially conventional forms of communication gradually, after behavioral escalation has been consistently prevented.

Tenet 4: Behavior Analysts Protect Dignity through Use of Least Restrictive Procedures

Behavior analysts protect dignity and promote safety by relying on antecedent-based interventions that honor precursor communication/behavior, and that reduce the likelihood of behavioral escalation. Behavior analysts support personal autonomy of all clients by refraining from physical management of challenging behavior, except when absolutely necessary to protect physical safety. Potentially nonpreferred or unpleasant procedures are delivered in consideration of both long- and short-term effects. In compliance with the Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts (BACB, 2020), where restrictive or punishment procedures are deemed absolutely necessary, they are developed in collaboration with an assenting client, are closely monitored, and discontinued as soon as safely possible (BACB, 2020, 2.15, p. 12).

Behavior analysts are compelled by the Ethics Code and its four foundational principles (BACB, 2020, Core Principles, guidelines 2.13, 2.15) to maximize benefits and do no harm. In addition to being largely benevolent and effective, the practice of ABA does carry inherent risks of harm. Repeated exposure to stress as a result of prolonged or frequent behavioral escalations and/or restrictive procedures may pose risk of momentary or sustained psychological harm and momentary or prolonged loss of client dignity. According to a committee of psychosocial aspects of child and family health (Garner et al., 2012), toxic stress, the prolonged and repeated exposure to stress responses during developmentally sensitive periods of life, is purported to lead to harmful short- and long-term physical, behavioral, and psychological effects. In addition to short-term changes in observable behavior, toxic stress in young children can lead to less outwardly visible yet permanent changes in brain structure and function (Garner et al., 2012; Bremner 1999). Furthermore, intense escalation as a response to physical management procedures may present the following risks: injury to client, family, or provider; feelings associated with loss of control and dignity; damage to therapeutic relationship; fear/anxiety related to receiving services; and harm to the profession (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2018; Rajaraman et al., 2021a; Rajaraman et al., 2021b). Overall, when clients show distress, this should be discriminative for us to change our interventions so that we evoke less distress.

In any good-quality ABA treatment program, if clients continue to demonstrate severe behavior, then the plan is not working, by definition, and needs to be modified or terminated. Therefore, clients of ABA programs should not be experiencing long-term exposure to stress. Nevertheless, not all ABA services are of the highest quality, just as in any other helping profession, and clients may experience stress for other reasons. Therefore, we should always monitor the impact of our interventions on the emotional responses of our clients.

In order to balance short- and long-term alleviation of stress, discomfort, and suffering, behavior analysts should carefully observe when our behavior evokes or occasions behavioral escalation in our clients. To the greatest extent possible, we should consider avoiding engaging with our clients in ways that provoke their escalation. Severe client escalation is a sign to us that we have not engineered a context for positive reinforcement and engagement and/or that in setting contingencies for teaching functionally equivalent replacement behaviors, we have not taken the opportunity to prevent more severe forms of escalation by terminating contingencies at the point of precursor escalation. Emerging literature has demonstrated that severe problem behaviors may be safely managed, and clients may continue to successfully acquire important skills through approaches that are designed to avoid behavioral escalation (Rajaraman et al., 2021b).

Job Aides to Assist in Application of the Tenets

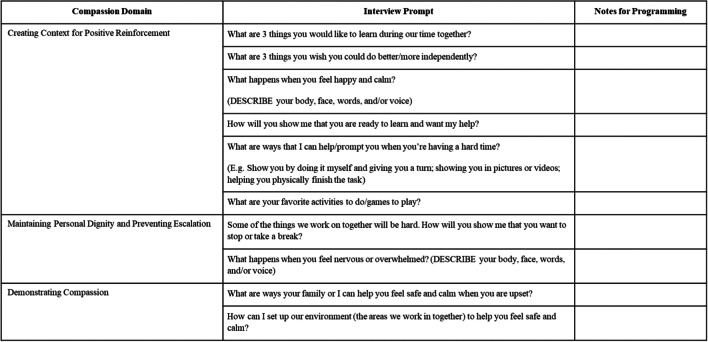

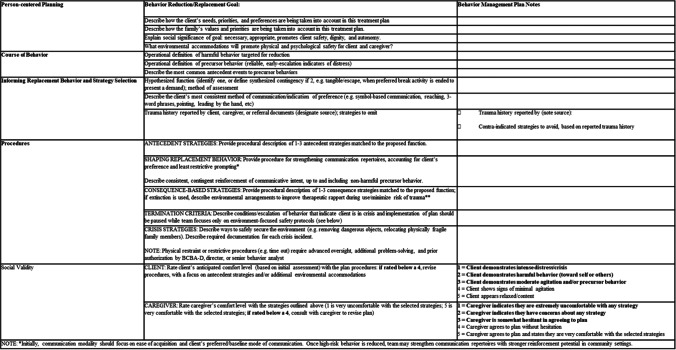

Figures 1 through 3 provide examples of practical tools that might be created to aid clinicians in centering compassion in designing and supervising interventions. Figure 1 consists of an interview form to support the behavior analyst’s adoption of compassion-focused care when designing intervention plans for autistic clients who have the functional communication repertoire to communicate their perspectives directly to the behavior analyst. Like any applied behavior analytic aide, this interview form should not be read verbatim, but rather customized by the individual BCBA for use with each unique client.

Fig. 1.

Compassion-Focused Interview Form for Clients with Reciprocal Communication Repertoires. Note. The scale of this interview form has been reduced to fit inside on journal page; more room will likely be needed for notetaking

Fig. 3.

Sample Compassion-Focused Behavior Intervention Plan Template. Note. Insufficient social validity scores are indicated in bold text to emphasize the importance of revising the document until acceptable social validity is achieved

Figure 2 consists of an interview form to support the behavior analyst’s adoption of compassion-focused care when designing intervention plans for autistic clients who may not have the reciprocal communication skills to communicate all their values and preferences directly to the BCBA, and therefore may benefit from also having caregiver input taken into consideration. This interview tool is intended to be used for interviewing parents, siblings, or other caregivers. Note that caregiver report is not always an accurate indication of client preferences and values and must therefore always be supplemented by direct observations of client assent and choice behaviors (Hanley, 2010). Figure 3 is a sample template for a behavior intervention plan that includes prompts for considering tenets of compassion-focused care when designing interventions.

Fig. 2.

Compassion-Focused Caregiver Interview Form for Clients with Less-Developed Reciprocal Communication Repertoires

It is important to note that these tools are provided as potential examples, not as prescriptive recipes or templates to follow. It is also important to note that no research has been conducted to evaluate the effects of these aides on the behavior of behavior analysts designing intervention plans, nor on the effects of those interventions on client outcome. Like all other practical tools and curricula, it is the responsibility of the behavior analyst to customize and empirically evaluate the effectiveness of what we do with each individual client.

Discussion

Throughout this article we have held in philosophic doubt procedures with significant empirical support establishing their efficacy. We assert that compassionate and effective practice are not mutually exclusive. We advocate for taking great care when a procedure is selected which has the potential to place a client into distress. For each procedure, we may be ethically bound to consider the following: the extent to which the client has received opportunities to collaborate in selecting goals, procedures, and desired outcomes (Wolf, 1978); the client’s opportunities to give and withdraw assent; safeguards to client dignity via least restrictive procedures and a focus on positive reinforcement to every extent possible; and a very careful and serious evaluation of the degree to which intrusive procedures are truly necessary and beneficial in both the short and long term.

Some behavior analysts may perceive a call for compassionate care to be naïve to the challenges that are inherent in working with especially severe or complex cases. It is important to acknowledge that simple modifications to ABA procedures may not be sufficient for successfully managing severe behavior and keeping all people involved safe (e.g., with clients who have substantial medical, psychiatric, or comorbid conditions that complicate treatment). However, even in the most complex and severe cases, the treatment team has choices to make between treatment components and between different ways in which those components can be delivered. Even in the most severe cases, we who provide care have the opportunity to ask ourselves, have we considered if our interventions do everything possible to minimize and avoid client distress both in the short and long term? We might make the argument that the most severe cases may be the ones in which we may be most likely to resort to more intrusive procedures sooner, and therefore these cases may represent the greatest opportunity for us to reflect on the extent to which we have built our procedures on a foundation of compassion. This article’s call for a serious and careful reconsideration of physical management and other procedures that can evoke behavioral escalation should not be taken to imply that behavior analysts working with severe behavior are not compassionate and caring human beings; nor is this article a call to abandon effective strategies that are truly necessary in a given context. Instead, we believe practitioners should continuously evaluate procedures that cause escalation and judiciously evaluate alternatives, as well as weigh long- and short-term benefits in collaboration with the client.

In addition to allaying concerns of efficacy in compassion-focused practice and toward alleviation of suffering related to severe behavioral escalation, we wish to address use of the terms “radical compassion” and “compassion-focused” care throughout this manuscript. Some readers may object to this article coining yet another new term in ABA, in this case, “compassion-focused applied behavior analysis.” One potential limitation to using the term is that some may believe it implies that practitioners who do not explicitly say they practice compassion-focused ABA are not compassionate. At the same time, we acknowledge feedback from consumers who have not experienced ABA as compassionate (Taylor et al., 2019; Autistic Self-Advocacy Network, n.d.). In this article, we have attempted to functionally define the foundation for compassion-focused ABA, as well as provide potential suggestions for how to pursue it. We in no way suggest that the term itself makes one compassionate or that those who choose not to use the term are not compassionate. It is also not our position that any particular practice is more or less compassionate, but rather that behavior analysts, in pursuit of alignment with our founding literature and ethical guidelines, seek to align effective practice with tenets of compassionate care. We expect the phrase compassion-focused ABA will be useful for orienting discussion, program development, and research.

Wolf’s (1978) seminal concept of social validity might be argued to already encompass compassion, and we have made the case in this article that assessing social validity is likely one useful tactic for helping oneself provide more compassionate services. However, we argue that social validity is not equivalent to compassion. Social validity is assessed by asking clients and/or their family about their perceptions of what we do. It is entirely possible for clients and/or their families to rate the acceptability of services highly even when those services are not delivered compassionately. Especially for families who are desperate for any help and have overcome massive obstacles just to access services, they may be highly unlikely to report to service providers that they do not feel like they are being treated compassionately. In addition, it is worth noting that social validity measures have very rarely attempted to address social validity from the client directly, instead relying on caregiver report (Hanley, 2010). Assessing social validity is one important tool for enhancing our compassionate behavior, but the two are not equivalent, and we contend that assessing social validity is not an adequate substitute for taking a compassionate approach as the foundation for our work.

We propose that compassion is sufficiently important to the field of ABA that it be adopted as another defining characteristic. Although we contend that ABA is a compassionate science, at the time this article was published, our field may not have developed our compassionate repertoires substantially enough to claim that compassion is a defining characteristic of our daily practice yet. However, it is within our right as a field to proclaim that compassion is foundational enough to serving others that it should be a defining characteristic of ABA, equal in importance to the classic seven dimensions (Baer et al., 1968). In this sense, perhaps compassion might be considered an aspirational defining dimension of ABA. We believe this is a critical aim, so that we might evolve the oft-proclaimed goal of “saving the world with ABA” to “serving the world with ABA.”

Future Research

It is important to note that the basic premise of this article—that applied behavior analysts can and should begin from a foundation of compassion in everything we do with clients, caregivers, and one another—is not based on research. It is a moral and ethical position that does not require empirical data for support, much like the content of virtually all professional ethical guidelines. Still, basing daily practice on published evidence is a hallmark of the science of ABA, and we believe there is vast potential for empirically evaluating compassion-focused modifications to ABA-based autism services. First, there is a need for further research on whether commonly used ABA procedures lead to long-term suffering. Second, research is needed on whether compassionate-focused approaches to ABA reduce short- or long-term suffering, compared to older ABA procedures, and/or compared to nonbehavioral approaches. The tools offered in this article have not been subjected to research on their effectiveness, and such research would be a practical place to start on evaluating compassionate modifications to common ABA procedures.

We are encouraged by the substantive contributions to this discussion in health care (e.g., improving patient outcomes), as well as emerging behavior analytic research in this area (Rajaraman et al., 2021b; Rohrer et al., 2021). Much potential for future research lies before us. A simple question could likely be applied to virtually all we do on a daily basis: For any specific evidence-based ABA procedure, is it possible to modify the procedure to be more compassionate and, if so, what will the effectiveness of the modified procedure be, both in changing client behavior and in affecting social validity and our relationships with clients? We hope and expect to see compassion-focused protocols, trainings, and outcome measures result in improved client progress, collaborative caregiver relationships, greater sense of belonging in the profession, and improved resilience and reduced burn-out of practitioners. In addition, although not expanded upon in the current article, extending compassion toward caregivers, colleagues, mentees, and ourselves, are significant potential areas of application, each deserving of its own discussion and research efforts.

We previously highlighted that some of the emerging literature examining a less intrusive approach to behavior management (e.g., Rajaraman et al., 2021b) was conducted with individuals who demonstrated comparatively advanced skills (e.g., fluent communication repertoires). Evaluating these treatment approaches with individuals with more severe challenging behavior and fewer skills presents an interesting potential aim for future research. The existing literature examining risk reduction through treatment of precursor behaviors (Smith & Churchill, 2002) includes participants with severe problem behavior, and a potential extension of Rajaraman et al.’s work (2021b) might be to apply the enhanced choice model with clients with more severe problem behavior, where the precursor to intense escalation is the behavior targeted for intervention.

Future research might explore the trade-offs between reduced efficiency in the short-term versus long-term gains in mental health for everyone involved. A small amount of research has been published on procedures for reinforcing precursor avoidant behaviors as communication, thereby preventing escalation. For example, the enhanced choice model offers clients the opportunity to leave the work area at any time, and even to terminate the session and leave the clinic altogether at any time, without sacrificing treatment effectiveness, and with clients still completing substantial work (Rajaraman et al., 2021b). In addition, a small amount of research has been published on procedures for building engagement that do not rely heavily on extinction. For example, Shillingsburg et al. (2019) demonstrated a systematic transition approach from rapport-building to intensive instruction, with a focus on encouraging social approach behaviors and positive reinforcement, rather than relying on escape extinction. Peck et al. (1996) demonstrated reduction of severe problem behavior in individuals with disabilities by embedding choice-making within a functional communication training program, reducing or eliminating the need for extinction. In addition, Briggs et al. (2019) demonstrated that manipulating reinforcement magnitude and quality within differential reinforcement of alternative behavior without escape extinction was an effective treatment for decreasing destructive behavior. Although more research is needed, the efficacy within these studies highlights the point that little or no research has been published that demonstrates that potentially aversive, intrusive, or distressing approaches are more effective. As emerging literature suggests that engagement-based programming can develop a productive instructional interaction, while avoiding unnecessary escalation, future research could compare the results of these newer procedures on both short-term and long-term outcomes.

Assent-based programming may sometimes involve reinforcing escape-motivated behavior, including challenging behaviors. Many clinicians may be concerned that reinforcing escape-motivated challenging behavior may simply strengthen the behavior and prevent the progress of treatment, but data should be used to make this determination at the level of each individual client, rather than assuming a priori that escape extinction is necessary. Toward this end, it may be useful to evaluate the practice of beginning behavior intervention plans without extinction. For example, Briggs et al. (2019) successfully implemented differential reinforcement of alternative behavior without escape extinction by manipulating the combination of magnitude and quality of reinforcement. In practice, we could develop behavior plans that differentially reinforce challenging versus replacement behavior. A behavior plan for escape-maintained behavior without extinction may include arranging a contingency in which reinforcement (i.e., escape) is provided following any challenging behavior within the same functional class, whereas a richer version of reinforcement (likely a learner-specific combination of a longer duration of escape with highly preferred tangibles or attention) follows an identified replacement behavior. A behavior plan for a behavior that is primarily maintained by access to tangible reinforcement, may include providing shorter access to a moderately preferred version of the desired item or activity contingent on any challenging behavior within the same functional class, while providing longer access to a highly preferred version of the item or activity for the desired alternative behavior. A contingency along the same lines could be arranged for attention-maintained behavior. It may be a more ethical approach to assume that learners can be motivated through reinforcement and only add extinction to behavior intervention plans when client data have demonstrated clearly that creative and varied approaches to engagement-based instruction have failed. Although these approaches offer face validity, further empirical evaluation of these recommendations are needed. It is our hope that future research in this area could serve to create a roadmap toward less restrictive, reinforcement-based programming that still demonstrates efficacy and long-term benefit.

It also seems possible that less intrusive approaches could take longer to produce change in specific behaviors in the short-term, but that the overall rapport and relationships that are strengthened through compassion-focused repertoires could result in larger positive behavior change in the long-term. It also seems possible that compassion-focused approaches may actually result in more learning opportunities per unit time if they create less frequent establishing operations for escape-motivated behavior. Future research is needed to evaluate such possibilities. In addition, because negative reinforcement and punishment-based procedures with a greater risk of causing distress are permissible under the Ethics Code when necessary, empirical literature should undertake evaluation of what constitutes necessity. Although it is true that literature establishing empirical support for various procedures was effective over the course of the study, necessity is not automatically demonstrated by the same measures. Comparative studies, evaluating short- and long-term follow-up effects of more and less intrusive interventions would go a long way to highlight whether distressing procedures that have demonstrated efficacy were strictly necessary to create the desired outcome.

Summary

Compassion is integral to the founding assumptions of ABA (Skinner, 1953; Baer et al., 1968). Strong compassion repertoires position the practicing behavior analyst to deliver highly acceptable programs that can improve client quality of life (Taylor et al., 2019). The recommendations from recent and emerging literature may be summarized as: developing noncontingent therapeutic rapport through engaging programs that monitor for assent and honor self-advocacy (Rajaraman et al., 2021b); determining ongoing client preference and surveying for acceptability (Hanley, 2010); and promoting equity and client dignity by programming in a manner that prevents avoidable escalation and refraining from nonemergency physical management (Rajaraman et al., 2021b; Mathur & Rodriguez, 2021). Implementing compassion-focused repertoires outlined in this article as a foundation for our daily work in ABA may offer substantial improvement in meaningful, therapeutic relationships that promote improved effectiveness and greater social validity. Because compassionate care requires responding to and being guided by client feedback, it is our responsibility to demonstrate to the autistic community that we are listening to their input, both at the level of each individual client and at the larger societal level.

We may do ourselves and our field an important service if we consider whether we face a moral imperative to work toward a practice of radical compassion. At this point, we might return to considering the function of our behavior as behavior analysts. Do we exist merely to increase and decrease socially meaningful behaviors? Or are we called to a potentially deeper purpose of affecting the world by using our science to alleviate suffering in each interaction? Although not expressly included as a dimension of ABA, the aim of solving problems of social significance is so aligned with a philosophy of working to relieve suffering that radical compassion is arguably woven throughout the existing dimensions. In their seminal article on finding the heart of behavior analysis, Montrose Wolf (1978) wrote, “If you publish a measure of 'naturalness' today, why tomorrow we will begin seeing manuscripts about happiness, creativity, affection, trust, beauty, concern, satisfaction, fairness, joy, love, freedom, and dignity.” It strikes us that compassion-focused ABA is a step toward the fulfillment of that call: to apply our science in a way that establishes trust, expands freedoms, and safeguards the dignity of all we serve.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed for the current manuscript.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no known conflicts of interest. This manuscript does not include research with human participants or animals; informed consent guidelines are not applicable.

Footnotes

The authors thank Nicholas Yates for his invaluable consultation throughout the manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Anderson RE. Human suffering and quality of life: Conceptualizing stories and statistics. Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SR, Taras M, O'Malley-Cannon B. Teaching new skills to young children with autism. In: Maurice C, Green G, Luce S, editors. Behavioral intervention for young children with autism: A manual for parents and professionals. Pro-Ed; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Autistic Self-Advocacy Network (n.d.). For whose benefit?: Evidence, ethics, and effectiveness of Autism interventions [White paper]. https://autisticadvocacy.org/policy/briefs/intervention-ethics/

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1(1):91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholome WG. Informed consent, parental permission, and assent in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 1995;95(2):314–317. doi: 10.1542/peds.96.5.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2014). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020). Ethics code for behavior analysts.

- Bonvicini KA, Perlin MJ, Bylund CL, Carroll G, Rouse RA, Goldstein MG. Impact of communication training on physician expression of empathy in patient encounters. Patient Education & Counseling. 2009;75(1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD. Does stress damage the brain? Biological Psychiatry. 1999;45(7):797–805. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AM, Dozier CL, Lessor AN, Kamana BU, Jess RL. Further investigation of differential reinforcement of alternative behavior without extinction for escape-maintained destructive behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2019;52(4):956–973. doi: 10.1002/jaba.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bstan-‘dzin-rgya-mtsho DLXIV. The power of compassion. HarperCollins; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Garner AS, Shonkoff JP, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, McGuinn L, Pascoe J, Wood DL. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: Translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e224–e231. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P. The compassionate mind: A new approach to life's challenges. Constable-Robinson; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Goldiamond I. Toward a constructional approach to social problems: Ethical and constitutional issues raised by applied behavior analysis. Behaviorism. 1974;2(1):1–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP. Toward effective and preferred programming: a case for the objective measurement of social validity with recipients of behavior-change programs. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2010;3(1):13–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03391754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeyer A, Toffoli L, Vernon R, Taylor R, Fontaine D, Klopper HC, Coetzee SK. Teaching the practice of compassion to nursing students within an online learning environment: A qualitative study protocol. Contemporary Issues in Education Research (CIER) 2016;9(4):201–222. doi: 10.19030/cier.v9i4.9790. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lalli JS, Vollmer TR, Progar PR, Wright C, Borrero J, Daniel D, Barthold CH, Tocco K, May W. Competition between positive and negative reinforcement in the treatment of escape behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32(3):285–296. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc LA, Gingles D, Byers E. The role of compassion in social justice efforts. In: Zube M, Sadavoy J, editors. Compassion and social justice in applied behaviour analysis: A Collection of essays. Routledge; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc LA, Taylor BA, Marchese NV. The training experiences of behavior analysts: compassionate care and therapeutic relationships with caregivers. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;13(2):387–393. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00368-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur SK, Rodriguez KA. Cultural responsiveness curriculum for behavior analysts: A meaningful step toward social justice. Behavior Analysis Practice. 2021;15(4):1023–1031. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00579-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris C, Detrick JJ, Peterson SM. Participant assent in behavior analytic research: Considerations for participants with autism and developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2021;54(4):1300–1316. doi: 10.1002/jaba.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Pelletier-Bui A, Smith S, Roberts MB, Kilgannon H, Trzeciak S, Roberts BW. Curricula for empathy and compassion training in medical education: A systematic review. PloS One. 2019;14(8):e0221412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova A, Wang C, Boggiss AL, O'Callaghan A, Consedine NS. Predictors of physician compassion, empathy, and related constructs: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2022;37(4):900–911. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07055-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck SM, Wacker DP, Berg WK, Cooper LJ, Brown KA, Richman D, McComas JJ, Frischmeyer P, Millard T. Choice-making treatment of young children’s severe behavior problems. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29(3):263–290. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett M, Ala'i-Rosales S, Cruz AR, Cihon TM. Social justice is the spirit and aim of an applied science of human behavior: Moving from colonial to participatory research practices. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2021;15(4):1074–1092. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00591-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaraman A, Austin JL, Gover HC, Cammilleri AP, Donnelly DR, Hanley GP. Toward trauma-informed applications of behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2021;55(1):40–61. doi: 10.1002/jaba.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaraman A, Hanley GP, Gover HC, Staubitz JE, Simcoe KM, Metras R. Minimizing escalation by treating dangerous problem behavior within an enhanced choice model. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2021;15(1):219–242. doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00548-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer JL, Marshall KB, Suzio C, Weiss MJ. Soft skills: The case for compassionate approaches or how behavior analysis keeps finding its heart. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2021;14(4):1135–1143. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00563-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillingsburg MA, Hansen B, Wright M. Rapport building and instructional fading prior to discrete trial instruction: moving from child-led play to intensive teaching. Behavior Modification. 2019;43(2):288–306. doi: 10.1177/0145445517751436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman M. Coercion and its fallout. Authors Cooperative; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sidman M. Reflections on behavior analysis and coercion. Behavior & Social Issues. 1993;3:75–85. doi: 10.5210/bsi.v3i1.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair S, Beamer K, Hack TF, McClement S, Raffin Bouchal S, Chochinov HM, Hagen NA. Sympathy, empathy, and compassion: A grounded theory study of palliative care patients' understandings, experiences, and preferences. Palliative Medicine. 2017;31(5):437–447. doi: 10.1177/0269216316663499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. The operational analysis of psychological terms. Psychological Review. 1945;52(5):270–277. doi: 10.1037/h0062535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Science and human behavior. Macmillan; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts.10.1037/11256-000

- Smith RG, Churchill RM. Identification of environmental determinants of behavior disorders through functional analysis of precursor behaviors. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35(2):125–136. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvain MM, Knochel AE, Gingles D, Catagnus RM. ABA while Black: The impact of racism and performative allyship on Black behaviorists in the workplace and on social media. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2022;15:1126–1133. doi: 10.1007/s40617-022-00694-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BA, LeBlanc LA, Nosik MR. Compassionate care in behavior analytic treatment: can outcomes be enhanced by attending to relationships with caregivers? Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12:654–666. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00289-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2018). Discipline disparities for black students, boys, and students with disabilities: report to congressional requesters. https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/690828.pdf

- Van Houten R, Axelrod S, Bailey JS, Favell JE, Foxx RM, Iwata BA, Lovaas OI. The right to effective behavioral treatment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1988;21(4):381–384. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1988.21-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilardaga R. A relational frame theory account of empathy. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy. 2009;5:178–184. doi: 10.1037/h0100879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf MM. Social validity: the case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1978;11:203–214. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed for the current manuscript.