Abstract

Given the persistent shift in racial and ethnic demographics in the United States, board certified behavior analysts (BCBAs) will increasingly serve culturally and linguistically diverse families. There has been a recent increase in published resources to help behavior analysis practitioners navigate working with diverse populations. The purpose of this article is to add to these resources and demonstrate how these recommendations can be put into action. We outline five recommendations for working with culturally and linguistically diverse families in the context of a small company that has incorporated these practices in their own work focused on serving a large percentage of immigrant families.

Keywords: Applied behavior analysis, Culturally and linguistically diverse families, Immigrant families, Service delivery

There is an urgent need for professionals in the field of applied behavior analysis (ABA) to consider culture when working with all families. Given the persistent shift in demographics in the United States with the nation’s foreign-born population projected to rise from 44 million people in 2016 to 69 million in 2060 (Vespa et al., 2020), ABA practitioners will increasingly serve families and individuals of racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds. Research outside of behavior analysis has consistently shown that health services are not equipped to meet the needs of an increasingly diverse population in the United States (Nair & Adetayo, 2019; Riley, 2012). This effect is mirrored in the field of ABA with multiple calls to train professionals in cultural humility (Wright, 2019), cultural responsiveness (Jimenez-Gomez & Beaulieu, 2022), and compassionate care (Rohrer et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2019), and to increase the number of diverse professionals in the field (Beaulieu et al., 2018; Fong et al., 2017; Rosales et al., 2022). This call to action is both timely and pressing given the most recent demographics reported by the Behavior Analyst Certification Board ([BACB] n.d.) showing that 69.16% of board certified behavior analysts at both the master’s and doctoral degree levels are white.

In a webinar hosted by the Behavioral Health Center of Excellence focused on culture and language inclusion in the field, Hernandez and Williams Awodeja (2022) asserted that failing to take into consideration culture for families and individuals under our care violates the Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts (2020) and helps to maintain a system of oppression within the U.S. health-care system, and in particular within the ABA industry. Results from a survey of 703 BCBAs conducted by Beaulieu et al. (2018) on several variables related to working with individuals of diverse backgrounds indicated that 57% of respondents reported that more than half of their clients were from diverse backgrounds, 88% agreed that training on working with diverse populations was extremely or very important, and 86% felt moderately or extremely skilled at working with individuals from diverse backgrounds. These results are surprising given that 82% of the respondents also reported they had little to no training or coursework on these topics and 71% reported their employer provided little to no training related to working with individuals from diverse backgrounds. These results were supported by Conners et al. (2019), who reported that only 54.53% of behavior analysts responding to a survey focused on multiculturalism and diversity in ABA reported their graduate training curriculum covered content related to working with racially and ethnically diverse clients; whereas even fewer (36.46%) reported their graduate training provided opportunities to gain clinical experience working with a racially and ethnically diverse learner population.

There are significant disparities in terms of quality and basic access to various forms of healthcare for families of racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2014). Despite the efforts of collaborators and researchers to address these inequities and examine their cause and viable solutions, they have persisted over the years (Reynolds, 2017; Riley, 2012) and were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Cione et al., 2023; Thomeer et al., 2023). Relevant to the field of ABA, it is well-documented that Black and Latin American children are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) at a much later age than their white counterparts (Mandell et al., 2009; Zuckerman et al., 2014), and that these same populations report difficulties in accessing ABA services, resulting in suboptimal outcomes (Ferguson & Vigil, 2019; Magaña et al., 2012). In a recent publication by Broder-Fingert et al. (2020), the authors highlight the significant racial inequities that exist for children with autism in accessing services that may also be present in the practice of ABA. The factors creating this inequity and disparity in access to treatment are complex and may include racial bias and discrimination (Beaulieu & Jimenez-Gomez, 2022), lack of diversity in the workforce (Conners et al., 2019), differing insurance reimbursement rates (Zhang & Cummings, 2020), and a concentration of services and professionals with expertise in geographic areas (Drahota et al., 2020).

A study by Parish et al. (2012) examined access, utilization, and quality of health care for Latin American children with autism and other developmental disabilities using publicly available data. Results revealed that, compared to their white counterparts, Latin American children fared worse in all three categories with poorer health-care access, utilization, and quality. Further analysis of the data indicated that several quality indicators were correlated with these disparities including providers not spending enough time with the child, providers not being culturally sensitive, and providers not making caregivers feel like partners in the development of treatment goals for their child. Access to ABA services is a critical element to promote equity and inclusion within the field. Yet, recent studies and discussion papers have highlighted the barriers that marginalized communities face when accessing ABA services. For example, Castro-Hostetler et al. (2021) and Rosales et al. (2021) described the poor overall experience of Latin American families accessing ABA services, and Čolić et al. (2021) described the perspective on racism in ABA services by Black caregivers’ receiving services for their child.

Once ABA services are secured, it is important for providers to consider the adaptations needed when working with families of culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) backgrounds (Bernal et al., 2009; Dennison et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2019). Cultural adaptation has been defined as “the systematic modification of an evidence-based treatment (EBT) or intervention protocol to consider language, culture, and context in such a way that it is compatible with the client's cultural patterns, meanings, and values” (Bernal et al., 2009, p. 362). Thus, adaptations can occur at varying levels and dimensions including language of intervention, the individuals delivering the intervention, metaphors of cultural expressions used during intervention, content or cultural knowledge about different groups of individuals, treatment concepts, goals, methods, and the context of the intervention that can include social, economic, and political variables related to the individual (Bernal et al., 1995).

There has been a recent increase in publications focused on providing recommendations and resources to ABA practitioners working with CLD families (e.g., Deochand & Costello, 2022; Kornack et al., 2019; Martinez & Mahoney, 2022; Neely et al., 2019). These articles serve as a helpful start for practitioners to consider cultural adaptations that may be necessary and helpful in the delivery of services. The present article aims to present recommendations alongside actionable steps for individual providers and organizations working with culturally and linguistically diverse families. The second and third authors have implemented the recommendations in their own company that serves a large demographic of CLD families, including immigrant families from various regions of Africa, the Caribbean, and Latin America, who live in an urban region of the northeast United States where the company provides ABA services. The company was established in 2012 with a core value of providing culturally sensitive ABA services. The recommendations outlined in this manuscript were implemented based on the lived experience of the founder of the company and are in line with recent publications that provide guidance to practitioners working in this domain.

Recommendation 1: Create a Family Liaison Position

Companies that provide ABA services to CLD families may benefit from additional support to navigate language and cultural barriers and to assist clients with non-ABA related topics. For example, families may benefit from dedicated time describing ABA services (e.g., what sessions will look like, how families will be involved), and may need help navigating the school system (Blair & Haneda, 2021), legal systems (Cycyk & Durán, 2020), and identifying and connecting with related social services outside of ABA (e.g., mental health counseling, respite care; Wylie et al., 2020). These are tasks that a well-trained individual servicing in a Family Liaison role can provide in an attentive and thorough manner.

Previous related research has shown that training “family navigators” is a promising approach to improve early ASD diagnosis and access to treatment for families from underrepresented groups (Feinberg et al., 2021). Family navigators are trained community members who guide caregivers through obstacles to health care using a culturally responsive approach. A critical aspect of the family navigator is continuous and proactive outreach to families. The interactions between a family navigator and the family helps to bridge cultural and language barriers because they will often have personal knowledge of the family’s circumstances that may mirror their own learning histories.

A related concept is the role of a family liaison in school settings (Dretzke & Rickers, 2016). Responsibilities of the family liaison most often include building rapport with families to create an environment where caregivers feel welcomed and included. For example, the family liaison can help connect caregivers with resources and ongoing school activities, and coordinate school events that increase parental involvement. For schools classified as “high-needs” areas (e.g., often correlated with more families living in poverty, single-parent households, and immigrant communities), this role is critical because caregivers may require additional help and resources to effectively navigate the school community and advocate for their child.

A family liaison can also assist with systematically and proactively reaching out to families to identify factors that can improve their experience, and as a result can increase satisfaction with the ABA services provided. This is important given recent reports from the Behavioral Health Center of Excellence (BHCOE) indicating that families who are recipients of Medicaid and Medicare, those who have lower contact with medical services, and those receiving ABA services for 2–3 years, may be the most likely to be dissatisfied with ABA services (Cox, 2022).

Application of Recommendation 1

To implement this first recommendation, the company created the role of family liaison to be an integral member of the administrative team. The family liaison is the first person families interact with after they are approved to receive services for their child from the company. One of the primary responsibilities of the family liaison is to communicate with parents on a regular basis, starting from the time the family enters the waitlist to the day they have completed or are discharged from services. This regular cadence of interaction facilitates building rapport and trust between the family and the service provider.

While a family is on a waitlist, the family liaison follows up with the caregivers to (1) provide updates on status of provider availability and wait time; (2) provide brief education around ABA services to prepare them for services; and (3) help refer them to other services if they no longer meet criteria for services with the company (e.g., they moved outside the company’s service area, they are already enrolled in behavioral health services). By providing follow-up while on the waitlist, the family liaison begins building a collaborative and trusting relationship with caregivers to support their child before services begin.

Once the company is authorized to begin services with the child, the family liaison completes an intake interview (see Recommendation 2 below). Next, the family liaison schedules a formal meeting with families every 6 months to ask questions that can assist caregivers in navigating the educational system, financial aid programs, legal resources, and mental health resources, as needed (see Table 1 for sample questions). The family liaison views each family as a separate and unique unit and is sensitive to individual differences, adjusting how they ask questions and gathering information as appropriate. In addition, the family liaison recruits feedback from caregivers on the services being provided and is the families’ primary contact for questions and/or concerns. Finally, the family liaison maintains open communication with clinical supervisors, directors, and other providers to ensure a feedback loop is in place.

Table 1.

Sample questions

| Sample Questions for Intake Interview |

| 1. Tell me about your family. Who lives at home [ask to specify relationship to each household member]? |

| 2. Can you share some of your family’s customs and traditions? Do you follow any religious norms/practices? [listen actively and ask follow-up questions] |

| 3. Which language does your family speak at home? Do you speak more than one language? How important is it that your child’s therapist speaks the home language? |

| 4. Do you prefer male or female therapists, or no preference? |

| 5. Is there a specific diet your child follows? Are there any food or drinks that are restricted or not allowed in your home? |

| 6. Are there any other requests or needs that you would like to share? |

| Sample Questions for 6-Month Follow-Up |

| 1. Do you know how to renew your child’s insurance? |

| 2. Is there any situation in your family dynamics that prevents you from taking full advantage of the company’s services? |

| 3. Are you familiar with the other community resources available to your child? |

| 4. Do you know when your child’s next Individualized Education Plan meeting is scheduled? Do you have questions about the meeting? |

| 5. Are you familiar with other social services available to you and your family? |

In addition to the formal meeting every 6 months, the family liaison connects with caregivers informally on a more regular basis in line with the needs of each family, and they are encouraged to reach out to the family liaison with questions or concerns at any time. As such, the family liaison becomes a trusted and integral member of the services rendered by the company. The family liaison initiates communication with caregivers following the intake process (see Recommendation 2) to provide updates on the progress in starting services and to share information about the ABA services their child will receive. This role is vitally important to families served by the company, as many are faced with unique needs. For example, a large percentage of the families served are immigrants from South and Central America and African countries. Immigrant families tend to experience difficulties understanding and navigating the U.S. health-care and education system, face language barriers, and may need assistance promoting their self-advocacy skills (Welterlin & LaRue, 2007).

In addition to the desired outcomes of support provided by the family liaison, the dedicated time to speak with families often results in the gathering of information crucial to ABA services but that may be missed by a clinical supervisor during more formal meetings. For example, the family liaison may discover that the client’s primary caregiver grew up with limited food on the table or faced harsh punishment for minor infractions as a child, which may hinder caregivers’ ability to fully comply with feeding programs or positive reinforcement strategies. Whereas it is important for all practitioners to develop “soft skills and show compassion in their delivery of services” (Taylor et al., 2019), the family liaison role centers around supporting families with general questions about the services they receive as well as providing guidance on services that may be outside the scope of the clinical services provided by the BCBA and behavior technicians. For example, the family liaison invites caregivers to share detailed (and sometimes lengthy) stories about their culture, provides them with ample information related to a host of social services, offers emotional support, and helps get them connected to social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, and other professionals, as needed. The family liaison has connected caregivers with programs and events that they were previously unaware of such as free summer camps and a list of additional free events in the community for the family to attend.

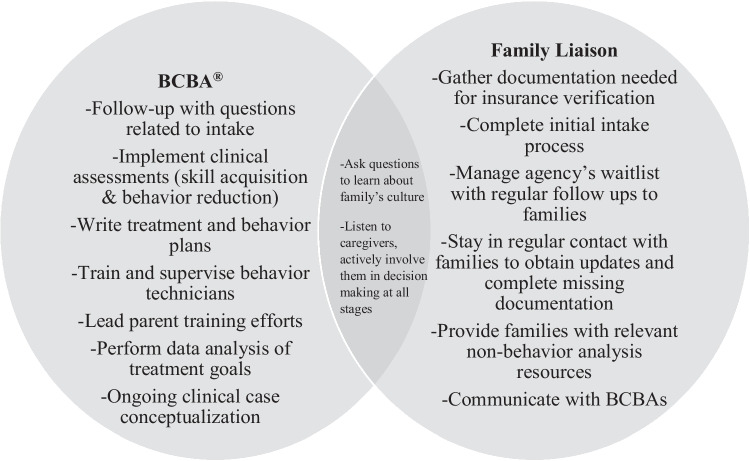

ABA services that includes a family liaison helps to ensure high-quality clinical care and the ability to address additional family needs. Figure 1 illustrates how the family liaison and BCBA work on separate goals but may overlap in their responsibilities.

Fig. 1.

Responsibilities of the BCBA and the Family Liaison

Recommendation 2: Conduct a Thorough Intake Interview

As part of the intake process, practitioners need to gather information about new clients to determine their specific needs and areas of strength. This begins with asking questions and listening to families. The intake interview can be conducted by someone in a supervisory or administrative role within a company (such as the family liaison), or by a BCBA. The information is gathered via review of prior records (e.g., treatment plans, diagnostic evaluation, individualized education plans), forms completed by caregivers, and ideally should include an interview with the family and direct observation of the client and caregiver interaction to help identify training needs. The intake assessment is an ideal time to begin building rapport and trust with families. Although there are ample resources available for practitioners to conduct structured and unstructured interviews as part of a functional behavioral assessment (e.g., Hanley, 2012; Horner et al., 2013; Reese et al., 2003), there are fewer resources to guide practitioners on conducting a thorough intake that will also take into consideration a family’s culture.

It is important to consider cultural variables from the beginning of the provider–client relationship. Allowing culture to help inform the treatment selection for each client will increase the likelihood that the services rendered are suited to each family’s needs. Tanaka-Matsumi et al., (1996) developed the Culturally Informed Functional Assessment Interview (CIFA Interview) as a step toward formulating culturally sensitive hypotheses regarding behaviors that are targeted for reduction and their controlling variables while selecting culturally acceptable replacement behaviors to increase overall treatment effectiveness. Lee et al. (2023) developed the Cultural Adaptation Checklist (CAC) as a guideline for including cultural adaptation in research and evaluating the quality of such adaptations in practice. These resources can be used and adapted by practitioners to develop their own intake form that will directly address cultural variables.

Application of Recommendation 2

To implement this second recommendation, the company initially developed an intake interview that was required for the reauthorization of services. The information in this document was deemed useful in gathering valuable information about the family’s culture and was later modified to include questions related to a variety of cultural variables. An important aspect of the intake interview that is currently used at the company is the completion of a demographics questionnaire. Caregivers respond to optional questions about their country of origin, their preferred language, their faith including religious practices, their preference for therapist characteristics, information about extended family members living in the home, and information about household norms and practices, leisure activities, and diet or preferred foods (see Table 1 for sample questions).

To build trust and rapport with parents and other caregivers, the family liaison conducts the intake interview in the family’s home, whenever possible. Although virtual meetings were necessary at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are important aspects of the initial interaction with families that can be missed when the intake is completed remotely (e.g., observations of parent–child interactions in the natural environment). For this reason, the intake interview is conducted in person whenever possible. The initial meeting is scheduled for up to 2 h with follow-ups as needed to assist with obtaining documents, to help families communicate with school personnel and other providers, and to begin establishing a collaborative relationship with the family and other professionals to best support the client. Subsequent follow-up meetings are scheduled to address additional family needs as they arise.

At the start of the interview, the family liaison tells caregivers that all questions are optional, and they can therefore skip any question they do not feel comfortable responding to. Caregivers also have many opportunities to ask questions about the information reviewed during the intake. Although parts of the questionnaire are close ended, the family liaison follows up to gather additional information about cultural practices. During the interview, the family liaison also describes what ABA services will look like in the home including the general types of treatment goals and programs their child may receive, describes the various components of services (e.g., direct therapy, supervision from clinical supervisors, caregiver training), explains how the number of therapy and supervision hours the child will receive are determined based on insurance reimbursement, and describes the formal assessment process that the clinical supervisor will conduct prior to developing a treatment plan. By reviewing this information with the family, the family liaison plants a seed on the importance of the family’s involvement in goal setting and treatment plan implementation to promote elevated levels of treatment integrity. The main objective of these early interactions is to learn about the family’s culture, to build trust, and for caregivers to become familiarized with and receptive to ABA services while collaborating with therapists and supervising clinicians.

Recommendation 3: Adapt Caregiver Training

Caregiver training is an integral component of any successful behavioral intervention (Negri & Castorina, 2014) and increasingly more funding sources are requiring that caregiver training be delivered by a BCBA as a part of treatment planning. Gunderson et al. (2022) recently reported that caregiver levels of procedural fidelity had a major influence on child cooperative responding. This research is in line with the robust body of evidence for the need to not only train staff and caregivers on implementation of behavioral interventions, but to continuously monitor for errors of omission and commission in treatment adherence (Fryling et al., 2012). Caregiver adherence to recommended behavioral strategies may require intensive training (Allen & Warzak, 2000; Dogan et al., 2017) as well as cultural adaptations (Raulston et al., 2019). To better understand some of the challenges associated with caregiver training, Raulston et al. (2019) conducted focus groups with parents of children with autism from various backgrounds. Three major themes emerged from the focus groups: (1) the need for individualized and supportive feedback from professionals; (2) accessible, flexible, and affordable training; and (3) social emotional support and connection to the community.

Other studies related to caregiver cooperation with treatment adherence indicate that when caregivers struggle financially or have limited economic resources, this may affect their ability to attend or fully participate in parent training sessions which may further impede progress (Quetsch et al., 2020). Likewise, research has shown that offering a form of monetary incentive helps to increase participation in training without diminishing rates of motivation to learn new skills (Gross & Bettencourt, 2019). Finally, previous research has recommended group training as a beneficial and cost-effective approach to educating parents and other caregivers (Schultz et al., 2011) and support groups for parents of children with disabilities to promote a sense of community, emotional support, and social companionship (Solomon et al., 2001).

Small group training has the added benefit of building a network for caregivers who experience higher levels of stress than those raising typically developing children and children with other disabilities (Padden & James, 2017), and who are often isolated or lack a social support system (Boyd, 2002). Parents of children with ASD from marginalized groups face a variety of challenges including lack of knowledge on how to access services, difficulties related to paying for specialized services, finding appropriate insurance to cover costs, and making decisions about treatment options (Vohra et al., 2014). Programs that incorporate parent-to-parent networks complement health-care services by empowering parents through information and support (Santelli et al., 1997).

Application of Recommendation 3

To implement this third recommendation, the second and third authors adapted caregiver training programs at their company by offering optional small group training on a monthly basis in addition to required individual training sessions; by offering incentives to encourage attendance to the nonrequired training sessions; and by conducting training in the families’ home language as much as possible, or providing interpreter services when an employee of the company does not speak the family’s home language (see Recommendation 4). Caregivers who opt to attend these additional training sessions are often able to use public transportation, live within walking distance to the company’s main office, and/or have their own personal vehicle. Not all families have access to a personal vehicle, and this is one of the main reasons the company strategically selected a location with easy access to public transportation and in a community where families can walk or bike to the building. These ideal characteristics in the geographic location of a company are not always possible to implement.

Flexibility is built into these options by recording the content of the trainings whenever possible and sharing recordings with families who are not able to attend, as well as encouraging families to carpool if possible, and by offering virtual attendance options for families who can access a device and use video communication platforms. The second and third authors found that all families served by the company have access to a phone with the capability to get on such platforms. In fact, using a phone is sometimes preferred by caregivers as it affords additional flexibility in where they can access the training. At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the children served by the company were primarily enrolled in an urban public school system that provided a tablet to all students for remote learning. The family liaison played a critical role in ensuring caregivers were able to connect to their child’s remote learning sessions and to caregiver training sessions that occurred remotely during this time.

Offering small group training creates opportunities for caregivers to come together and support one another. Small group training consists of a brief didactic presentation on relevant topics in ABA (e.g., functions of behaviors, reinforcement, generalization and prompting strategies) followed by behavioral skills training to teach the targeted skills, and time for questions and discussion to allow trainees to share their understanding of the topic. Prior to attending group training on a topic, the caregiver receives an introduction to the topic during individual training sessions with their child’s BCBA. Group training serves to review and reinforce concepts, allow time for additional questions, and provides an opportunity for caregivers to listen and share with others to build fluency on several topics. That is, caregivers help each other master basic concepts by explaining them to one another in layperson terms while a BCBA guides the discussion and clarifies any information that is shared between caregivers. These optional small group sessions are offered in addition to a minimum monthly one-on-one training conducted by the case supervisor to teach, model, and provide feedback on strategies that are specifically tailored to each child’s acquisition skills and behavior reduction goals.

In addition to group training on ABA topics, the company invites outside experts to speak on general topics relevant to caregivers raising a child with a disability including but not limited to understanding the individualized education plan process, parental self-advocacy skills, preparing for transition to adulthood, and disability rights. An important aspect of these group meetings is that they afford parents an opportunity to interact with one another in a social setting that resembles a support group. This is important given the documented need to make support groups available to caregivers of children with disabilities from underserved communities (Mandell & Salzer, 2007). As a result of these regular offerings, caregivers have an opportunity to come together to enjoy the company of a fellow parent, to learn together, and support one another in an informal context.

Recommendation 4: Translate Materials, Offer Interpretation, Hire Diverse Staff

Decades of research in the healthcare industry has demonstrated the critical need for providers to adapt their practices at minimum by translating materials and providing instructions for treatment adherence in the client or patient’s home language (Carrasquillo et al., 1999; Seijo et al., 1991; Tang et al., 2006). This evidence suggests that optimal communication, patient satisfaction, and outcomes and the fewest interpreter errors occurred when patients who were English language learners or had limited English proficiency had access to bilingual providers or to trained professional interpreters (Flores, 2005; Karliner et al., 2007). It is reasonable to expect that language will similarly affect client access and usage of ABA services. Thus, two surface level cultural adaptations (Wang-Schweig et al., 2014) that companies can provide to parents of CLD backgrounds is to hire bilingual/bicultural staff, and to provide training and written materials in the family’s home language. Some recent research on cultural adaptation in behavior analytic services tells us that although the effectiveness of an intervention may not be affected, consumers may show a preference when adaptations such as ethnicity matching between the provider and caregiver are provided (Sivaraman et al., 2022).

Hiring staff who speak the same language as the client helps to mitigate language barriers. We recommend organizations take steps to assess the need for representation, and to attract, retain, promote, and celebrate diversity within the company’s workforce (Rosales et al, 2022). As demonstrated by the BACB reported demographics, (BACB, n.d.), there is significant work to be done to increase diversity in the field, especially for those with master’s and doctoral degrees (i.e., BCBA, BCBA-D), because racial and ethnic minority groups are overrepresented at the registered behavior technician (RBT) level.

If the organization is unable to match the family with a provider who speaks the language the family has requested, all attempts must be made to secure an interpreter who is also familiar with the autism service system (Fong et al., 2022). Doing so increases the likelihood that parents will trust that the interpreter can accurately convey their needs and requests. This is crucial given that the failure to provide adequate interpreter services and translated written materials to patients with limited English proficiency could be deemed a form of discrimination, especially in federally funded programs (American Medical Association, 2017).

Additional adaptations that should be considered include the amount of text and overall comprehensibility of written materials provided to caregivers. Martinez and Mahoney (2022) provide step-by-step guidance on how to adapt parent training materials to better serve families of culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Recommendations for adaptations include limiting the amount of text, incorporating pictographs, or picture sequences that clearly depict a series of actions, adding in sufficient white space between sections of a document, using familiar language, and presenting information using bullets to improve overall readability of the document.

Application of Recommendation 4

The company implements this recommendation in various ways. First, there are strategic and targeted efforts to recruit, hire, and retain clinical and administrative staff who identify as persons of color and who are bilingual or multilingual (see Rosales et al., 2022, for data on staff demographics). The diversity of the staff reflects the community where the ABA services are provided by the company, and the demographics of the population served.

Second, the company shares a manual with all families that was created by the second and third authors to provide an overview of the ABA services rendered. The manual uses nontechnical language, has limited text with ample pictures, and includes slides with links to high-quality videos that show concrete examples of the behavioral interventions and terminology that caregivers may hear. In addition, the chief clinical officer ensures translation of all written materials. Previous papers on the language used within the field of behavior analysis have clearly shown the risk of using technical language when communicating with the public and consumers of our science (Becirevic et al., 2016). Moreover, creating documents that are accessible to families increases the likelihood that they will consume the information provided, increase adherence to treatment, and promote generalization by implementation of effective behavioral strategies in the home setting.

Finally, these steps may help contribute to retention rates, family satisfaction, and positive feedback from the families served. Since 2019 (when the company began collecting data on client retention), only 6.5% of clients that completed intake with the company opted to discontinue services. It should be noted that the company retained 100% of clients in 2020 despite the global COVID-19 pandemic. Whereas more than one variable undoubtedly affects client retention rate, the practices outlined above can contribute to retention when families feel supported. Formal input from families is discussed as the last recommendation and implementation.

Recommendation 5: Seek Formal Input/Feedback from Families

Social validity is touted as one of the integral dimensions of ABA (Baer & Wolf, 1987; Nicolson et al., 2020) with researchers continuously encouraging data collection and reporting of this validity measure in research and practice (Ferguson et al., 2019; Hanley, 2010). Although reports of social validity are often aligned with research, some studies have reported caregiver satisfaction with early intensive behavioral intervention (Grey et al., 2019), and there have been more recent calls for providers to seek out input from their clients and other stakeholders (Cox, 2022; Luiselli, 2021). Seeking and collecting feedback from consumers is an essential component of social validity.

According to the BHCOE quarterly strategic benchmark (Cox, 2022), organizations can collect, quantify, and calculate satisfaction with ABA services using a net promoter score—a metric used to measure customer satisfaction and loyalty to a company. A question that directly asks caregivers to indicate how likely they would be to recommend other families to seek services from the company is scored and calculated based on the number of “promoters” or those who would recommend the organization to other caregivers minus the number of “distractors” or those who would not recommend the company to other families (Cox, 2022). Other recommendations for development of a caregiver satisfaction survey include incorporating open text questions in addition to close-ended questions, and collecting data on a regular basis (e.g., on a quarterly basis or at least twice a year). Developing and distributing satisfaction questionnaires to caregivers serves as an invitation and opportunity to provide anonymous feedback to the company. Doing so may help ABA providers evaluate the acceptability of services provided and address concerns that families raise in a timely manner.

Application of Recommendation 5

To implement this recommendation, administrative staff at the company developed a “parent satisfaction survey” to formally gather input from caregivers regarding various aspects of the services rendered. The survey consists of 16 questions that can be rated on a scale of 1–5 with “5” being “strongly agree” and “1” being “strongly disagree”; and includes space for caregivers to provide narrative feedback (see Table 2). Caregivers are asked to rate their levels of satisfaction with various aspects of the services rendered, to rate the staff who interact with their child and family on a regular basis, to rate their overall level of comfort with asking questions to staff, and to rate their overall understanding of the treatment planning for their child.

Table 2.

Average responses on caregiver satisfaction survey (N = 29)

| Survey Item | Average | Range | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| I am satisfied with the home services my child is receiving | 4.90 | 4–5 | 0.31 |

| I am satisfied with the center-based services my child is receiving | 4.90 | 3–5 | 0.41 |

| My child’s therapy sessions are consistent (e.g., they are not often rescheduled by a behavior therapist) | 4.48 | 1–5 | 1.06 |

| It is important that the therapist(s) working with my child speaks my home language | 3.34 | 1–5 | 2.00 |

| It is important that the supervisor overseeing my child’s case speaks my home language | 4.11 | 1–5 | 1.69 |

| The services provided are sensitive to my culture (e.g., respect cultural norms, rules, expectations that are important to me and my family) | 5.00 | 5 | 0.00 |

| I am satisfied with the interpreter services provided to me | 5.00 | 5 | 0.00 |

| The supervisor overseeing my child’s services asks for my input before making treatment decisions | 4.97 | 4–5 | 0.19 |

| I am satisfied with the parent training the company offers | 4.83 | 3–5 | 0.54 |

| I feel comfortable asking questions to staff who are working with my child | 5.00 | 5 | 0.00 |

| The family liaison is an important member of the staff | 5.00 | 5 | 0.00 |

| I better understand how to manage my child's behaviors thanks to the services provided by the company | 4.90 | 3–5 | 0.41 |

| Since starting services at the company, my child has improved language and communication skills | 4.90 | 3–5 | 0.41 |

| Since starting services at the company, my child has improved social skills | 4.90 | 3–5 | 0.41 |

| Since starting services at the company, my child has improved independent living skills | 4.90 | 3–5 | 0.41 |

| The behavior therapist working with my child can meet their needs | 4.86 | 3–5 | 0.44 |

*The Likert scale for the survey ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree

SD Standard Deviation

When the company distributed the survey to all families (N = 51) a total of 29 families responded in an initial distribution (see Table 2 for summary of the data). The average response for all questions ranged between 3.34 and 5.00 with the lowest average score for the question that asked if families considered it important for the therapist(s) working with their child to speak their home language. It is interesting that although this question was rated on average as neutral on the satisfaction survey, the next related question asked about the importance of the supervisor overseeing their child’s case speaking the family’s home language and this question was rated higher with an average response of 4.11. This may indicate that families served by the company and who responded to this survey place a higher value on being able to communicate directly with the supervisor in their native language regarding their child’s needs and treatment planning, while acknowledging that a therapist could be a successful match for their child and interact only in English, the primary language of instruction at school. Overall, these two questions related to the importance of a “language match” were rated the lowest by the families who completed the survey. Questions that were rated as a 5.00 overall across all families included satisfaction with interpreter services (likely related to the high percentage of staff who are bilingual and multilingual hired by the company); the ABA services provided being sensitive to the families’ culture; feeling comfortable asking questions to staff who are working with their child; and the value of the family liaison role for the company.

This initial iteration of a social validity questionnaire was conducted via the phone and follow-up was conducted by the family liaison. Caregivers at the company are primarily from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and have limited time outside of work and caregiving. As a result, many were not able to provide the time needed to respond to the survey questions. In future iterations of the survey distribution, the company plans to provide multiple formats (electronic form, paper form, etc.) as alternatives to the phone call whereby the caregiver can choose how they will respond based on preference. Although caregivers at the company are accustomed to regular meetings with familiar staff to discuss their child’s treatment plan and seek out guidance on managing behaviors, they are less accustomed to formal meetings to answer survey questions as a form of feedback. Participation may increase as the company continues to regularly distribute the survey in flexible formats and lengths.

The survey presented here should be adapted by ABA agencies to seek direct input from their collaborators. For example, additional questions to consider including based on the information presented by Cox (2022) relate to the overall satisfaction regarding the rate of progress the child is making since beginning services with the company, quality of life for the child and family, satisfaction with ABA services in general, and whether the caregiver would recommend the company to other families seeking ABA services for their child. The results of this survey are preliminary and should be interpreted with caution given the relatively low response rate. The company is viewing this as a baseline measure to help guide further implementation and data collection as well as practice decisions related to some of the questions asked in the survey.

Reflections

Considering the information presented on the practices that are incorporated at the company of the second and third authors, additional recommendations should be highlighted. First, regarding conducting the intake our recommendation and practice has been to conduct this interview in the family’s home whenever possible to facilitate relationship building and to provide an opportunity to observe the child in their natural environment which may be particularly important if services will be provided in the family home. However, it is important to acknowledge that families may be hesitant to invite professionals into their home at the beginning of a relationship and practicing flexibility in where these interviews are conducted is equally important. For example, families can be given options of where this initial intake can take place (e.g., in the home, via Zoom, on the phone, at the center, at some other neutral location). Although rapport building may prove to be more challenging when this initial contact is not in person or in the natural environment for the child, it is important to assess levels of comfort and provide options to families at all stages of the relationship.

Second, regarding the intake form and the process followed to gather information from families and to build rapport, the recommendations outlined in this article can be modified to streamline gathering of demographic information and reduce the likelihood of unintentional aversive control by practitioners working with minoritized communities. For example, Jimenez-Gomez and Beaulieu (2022) provide helpful recommendations when collecting demographics including explaining the purpose of gathering this personal information to families, describing how their information will be protected, allowing respondents to skip questions, and including multi-select boxes on the form. The company currently requests demographic information via both printed and electronic forms as opposed to asking questions vocally during the intake process. The printed forms are sometimes easier for families to use. This decreases the likelihood that families may feel pressured to respond to questions they are not comfortable answering.

Third, regarding social validity, there are many individuals from whom companies can seek feedback and input regarding the acceptability and preference for interventions and practices that are followed. The company started to gather formal feedback from caregivers but other relevant individuals should be considered in the future including for example extended family members who live in the home (e.g., grandparents, siblings, cousins), as well as other professionals who work with the learner on a regular basis (e.g., speech language pathologist, physical therapist, psychologist, teacher). Asking for regular feedback and providing opportunities to collaborate will inevitably create an optimal experience for the client.

Finally, there are alternative methods to assess social validity that should be integrated into practice other than the formal survey described in this article. There are opportunities to assess social validity throughout the assessment and treatment process and several recommendations for doing so have been outlined previously (e.g., see Hanley, 2010; Jimenez-Gomez & Beaulieu, 2022). For example, when there are proposed changes to a treatment plan or a behavior support plan is updated, social validity can be assessed both formally and informally. Likewise, where there are updates in progress meetings, caregivers and other family members can give input and feedback on the implementation of treatment goals, interactions with staff, and overall satisfaction with the services rendered by the company. Formal or objective methods of assessing social validity include offering choices between treatment options (Jimenez-Gomez & Beaulieu, 2022; Schwartz & Baer, 1991). These continuous and practical social validity measures may yield a higher rate of responding than the formal survey described in this article.

These additional recommendations highlight the need to continuously evaluate and reflect on how improvements can be made to culturally responsive practices based on the input and feedback received by both consumers and employees. As such the five recommendations outlined in this article should be viewed as ever evolving and responsive to what we learn from application (see Table 3 for a summary and resources for each recommendation).

Table 3.

Recommendations and resources for working with CLD families

| Recommendation | Rationale/Implications | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Create a family liaison position |

-Based on models used by other health-care providers and in schools -Is the main point of contact for all nonclinical related questions -Some overlapping duties with the BCBA (related to rapport building) -Helps bridge connections between clinical providers and caregivers -May result in increased caregiver/family satisfaction with the company |

Dretzke and Rickers (2016) https://tinyurl.com/3bpbbwwb Feinberg et al. (2021) https://tinyurl.com/4edf2mym Welterlin and LaRue (2007) https://tinyurl.com/2cfwtrbm |

| 2. Conduct a thorough intake interview |

-Gather information to determine specific client and family’s needs and strengths -Ask questions related to culture -Begin to build rapport with families -Conduct in person (if possible) to allow for observation of family dynamics -Gain perspective on family values and customs |

Lee et al. (2023) https://tinyurl.com/2p8xhheb Tanaka-Matsumi et al. (1996) https://tinyurl.com/3cd4mknu |

| 3. Adapt caregiver training |

-Allows for additional support (parent-to-parent network) -Caregiver levels of procedural fidelity have a major influence on the effectiveness of behavioral intervention -Offer optional group training -Offer incentives |

Quetsch et al. (2020) https://tinyurl.com/293dmw95 Raulston et al. (2019) https://tinyurl.com/3583p53a Santelli et al. (1997) https://tinyurl.com/5n6dmv9t Vohra et al. (2014) https://tinyurl.com/mrky397c |

| 4. Translate materials, offer interpreter services, hire diverse staff |

-Denial of adequate interpreter services may be deemed a form of discrimination -Translating materials and providing interpretation services are minimum requirements of cultural adaptations -Hiring diverse and bilingual or multilingual staff is another minimal adaptation -Improve consumer satisfaction and retention |

American Medical Association (2017) https://tinyurl.com/p8ktcptz Flores (2005) https://tinyurl.com/2p8rbkyv Karliner et al. (2007) https://tinyurl.com/4mmwyrrs Martinez and Mahoney (2022) https://tinyurl.com/5n7fh23u Rosales et al. (2022) https://tinyurl.com/28sv3m9y Sivaraman et al. (2022) https://tinyurl.com/v7nmpmxk |

| 5. Seek formal input/feedback from families |

-Seeking feedback from consumers is an essential component of social validity -Satisfaction with ABA services can be collected using a social validity form with both closed and open-ended questions -Provides caregivers with opportunities to provide anonymous feedback to the company -May increase retention and overall satisfaction with ABA services |

Cox (2022) https://tinyurl.com/ytpc6z4p Grey et al. (2019) https://tinyurl.com/57rh3mxj Luiselli (2021) https://tinyurl.com/2k5nub7k Nicolson et al. (2020) https://tinyurl.com/p4y9ep7n |

Conclusion

The purpose of this article was to provide recommendations and examples of actionable steps ABA companies can take when working with CLD families. It is important to note that these recommendations are not exhaustive but can serve as a starting point for companies seeking resources to put into practice. The five recommendations outlined in this article were selected as a starting point because of the personal experience implementing these recommendations as part of company practice for the past decade.

A critical component of health-care services is culturally responsive care, defined as an ongoing practice in which the service provider actively works towards effectively providing services within the cultural context of the individual, family, and community they are serving (Campihna-Bacote, 2002). In line with Fong and Tanaka’s (2013) proposed standards on cultural competence, culturally responsive care begins with increasing cultural awareness (e.g., self- examination of one’s own culture), cultural knowledge (e.g., seeking and obtaining an educational foundation about diverse populations), and the development of a specific skill set (e.g., selecting culturally sensitive assessments and gathering culturally relevant data; Campihna-Bacote, 2002; Fong et al., 2016, 2017). However, it is not enough to simply acknowledge the cultures of other people. Behavior analysts need to first develop their own cultural awareness (Fong et al., 2016) and to assess how their lived experiences and culture shape how clients are perceived, prioritized, and treated (LeLand & Stockwell, 2019).

Cultural competency and humility are critical to providing equitable and effective services (Stubbe, 2020). This includes but is not limited to being responsive to diverse beliefs and values, delivering services in preferred languages, and considering factors that may affect a client or family’s ability to implement the recommended strategies with adequate levels of integrity. The information presented here is a preliminary demonstration in one clinical practice with a limited number of families. It is important to note that although the focus of the recommendations outlined in this article were for working with CLD families, the information is applicable to working with families of all backgrounds. It is important to note that the recommendations provided are not exhaustive; rather they are shared to serve as a starting point for companies seeking practice resources. We encourage practitioners and applied researchers alike to continue to actively collaborate with caregivers and to continually evaluate culturally responsive practices and collect data to support integration of these practices on a larger scale.

Appendix A: Sample Family Liaison Position Description

Position: Family Liaison

Classification: Exempt

Reports to: Chief Clinical Officer

Summary/Objective

The Family Liaison will support the company’s mission to provide a culturally responsive, effective, and individualized approach to intervention tailored to the unique needs of each child and family. The Family Liaison will help families navigate the system to enroll in ABA services and will serve as a support bridge during the enrollment process and beyond to create and maintain positive relationships.

Essential Functions

Initiate and finalize the intake process.

Manage the company’s waitlist and regularly follow up with families on expected wait time and required paperwork.

Gather all the necessary documents to open each case; submit to Billing & Payroll Administrator for insurance verification.

Monitor clients’ records and communicate with parents to obtain updates or missing documentation.

Communicate with the clinical team on a regular basis.

Assist with care coordination (communication with clients’ external provider team) and assist clients with referral to community resources as needed.

Distribute Parent Satisfaction Survey. Document responses and send them to the Chief Clinical Officer for follow-up action items.

Assist with organizing optional caregiver training and other events as required.

Required Education and Experience

Bachelor's degree in social work, psychology, counseling, or related field.

Valid driver’s license.

Bilingual (Spanish fluency required due to our client population).

Proficient in Microsoft Office Suite and Zoom.

1–2 years of experience working with families in a social service or advocacy setting.

Preferred Skills and Experience

Excellent interpersonal and communication skills (written & verbal).

Exceptionally organized.

Excellent problem-solving skills and ability to switch tasks quickly.

Receptive to constructive feedback.

Excellent relationship-building skills.

Work Environment

This job might operate in an office/program center environment, at the clients’ residences, or in alternative designated areas in the community. The Family Liaison is required to use a cell phone device for regular communication with staff and clients’ families.

Physical Demands

Duties may require standing and walking or sitting for extended periods of time as well as driving to different sites (e.g., clients’ homes, schools, agency offices).

EEO Statement

The company is an Equal Opportunity employer of qualified individuals and does not discriminate based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, disability, veteran status, or any other basis protected by applicable federal, state, or local law. The company prohibits harassment of applicants or employees based on any of the protected categories.

Funding

N/A

Data Availability

N/A

Code Availability

N/A.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

The first author is an unpaid research consultant for the company of the second and third authors. The second and third authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank Betzaida Fuentes, M.S., BCBA, LABA, president and founder of ABATEC and Claudia Rodriguez, family liaison of ABATEC. We also thank Dr. Tyra Sellers and several anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback on previous versions of this article.

References

- American Medical Association. (2017). Affordable Care Act, Section 1557 [Fact sheet]. https://www.ama-assn.org/media/14241/download

- Allen KD, Warzak WJ. The problem of parental nonadherence in clinical behavior analysis: Effective treatment is not enough. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33(3):373–391. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer DM, Wolf MM. Some still-current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1987;20(4):313–327. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1987.20-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (n.d.). BACB certificant data. https://www.bacb.com/BACB-certificant-data

- Beaulieu L, Addington J, Almeida D. Behavior analysts' training and practices regarding cultural diversity: The case for culturally competent care. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;12(3):557–575. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00313-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu L, Jimenez-Gomez C. Cultural responsiveness in applied behavior analysis: Self-assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2022;55(2):337–356. doi: 10.1002/jaba.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becirevic A, Critchfield TS, Reed DD. On the social acceptability of behavior analytic terms: Crowdsourced comparisons of lay and technical language. The Behavior Analyst. 2016;39(2):305–317. doi: 10.1007/s40614-016-0067-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Bonilla J, Bellido C. Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: Issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23(1):67–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01447045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Jiménez-Chafey MI, Domenech Rodríguez MM. Cultural adaptation of treatments: A resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice. 2009;40(4):361–368. doi: 10.1037/a0016401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blair A, Haneda M. Toward collaborative partnerships: Lessons from parents and teachers of emergent bi/multilingual students. Theory into Practice. 2021;60(1):18–27. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2020.1827896. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd B. Examining the relationship between stress and lack of social support in mothers of children with autism. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities. 2002;17(4):208–215. doi: 10.1177/10883576020170040301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broder-Fingert, S., Mateo, C., Katherine E. Zuckerman, K.E. (2020). Structural racism and autism.Pediatrics, 146(3), e2020015420. 10.1542/peds.2020-015420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Campihna-Bacote J. The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services: A model of care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing: Official Journal of the Transcultural Nursing Society. 2002;13(3):181–201. doi: 10.1177/10459602013003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasquillo O, Orav EJ, Brennan TA, Burstin HR. Impact of language barriers on patient satisfaction in an emergency department. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14(2):82–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Hostetler M, Greenwald AE, Lewon M. Increasing access and quality of behavior-analytic services for the Latinx population. Behavior & Social Issues. 2021;30:13–38. doi: 10.1007/s42822-021-00064-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cione, C., Vetter, E., Jackson, D., McCarthy, S., & Castañeda, E. (2023). The implications of health disparities: A COVID-19 risk assessment of the Hispanic community in El Paso. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 20(2), 975. MDPI AG. 10.3390/ijerph20020975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Čolić M, Araiba S, Lovelace TS, Dababnah S. Black caregivers’ perspectives on racism in ASD services: Toward culturally responsive ABA practice. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2021;15(4):1032–1041. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00577-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners B, Johnson A, Duarte J, Murriky R, Marks K. Future directions of training and fieldwork in diversity issues in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(4):767–776. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00349-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D. (2022). Digging into parent and caregiver satisfaction with ABA providers [Webinar]. Behavioral Health Center of Excellence. https://learning.bhcoe.org/courses/digging-into-parent-and-caregiver-satisfaction-with-aba-providers

- Cycyk LM, Durán L. Supporting young children with disabilities and their families from undocumented immigrant backgrounds: Recommendations for program leaders and practitioners. Young Exceptional Children. 2020;23(4):212–224. doi: 10.1177/1096250619864916. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison A, Lund EM, Brodhead MT, Mejia L, Armenta A, Leal J. Delivering home-supported applied behavior analysis therapies to culturally and linguistically diverse families. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(4):887–898. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00374-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deochand N, Costello MS. Building a social justice framework for cultural and linguistic diversity in ABA. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2022;15(3):893–908. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00659-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan RK, King ML, Fischetti AT, Lake CM, Mathews TL, Warzak WJ. Parent-implemented behavioral skills training of social skills. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2017;50(4):805–818. doi: 10.1002/jaba.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drahota, A., Sadler, R., Hippensteel, C., Ingersoll, B., & Bishop, L. (2020). Service deserts and service oases: Utilizing geographic information systems to evaluate service availability for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 24(8), 2008–2020. 10.1177/1362361320931265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dretzke BJ, Rickers SR. The family liaison position in high-poverty, urban schools. Education & Urban Society. 2016;48(4):346–363. doi: 10.1177/0013124514533794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg E, Augustyn M, Broder-Fingert S, Bennett A, Weitzman C, Kuhn J, Hickey E, Chu A, Levinson J, Sandler Eilenberg J, Silverstein M, Cabral HJ, Patts G, Diaz-Linhart Y, Fernandez-Pastrana I, Rosenberg J, Miller JS, Guevara JP, Fenick AM, Blum NJ. Effect of family navigation on diagnostic ascertainment among children at risk for autism: A randomized clinical trial from DBPNet. JAMA Pediatrics. 2021;175(3):243–250. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JL, Cihon JH, Leaf JB, Van Meter SM, McEachin J, Leaf R. Assessment of social validity trends in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2019;20(1):146–157. doi: 10.1080/15021149.2018.1534771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson A, Vigil DC. A comparison of the ASD experience of low-SES Hispanic and non-Hispanic white parents. Autism Research. 2019;12(12):1880–1890. doi: 10.1002/aur.2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong EH, Catagnus RM, Brodhead MT, Quigley S, Field S. Developing the cultural awareness skills of behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(1):84–94. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0111-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong EH, Ficklin S, Lee HY. Increasing cultural understanding and diversity in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis: Research & Practice. 2017;17(2):103–113. doi: 10.1037/bar0000076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fong VC, Lee BS, Iarocci G. A community-engaged approach to examining barriers and facilitators to accessing autism services in Korean immigrant families. Autism. 2022;26(2):525–537. doi: 10.1177/13623613211034067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong EH, Tanaka S. Multicultural alliance of behavior analysis standards for cultural competence in behavior analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation & Therapy. 2013;8(2):17–19. doi: 10.1037/h0100970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flores G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of healthcare: A systematic review. Medical Care Research & Review. 2005;62(3):255–299. doi: 10.1177/1077558705275416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryling MJ, Wallace MD, Yassine JN. Impact of treatment integrity on intervention effectiveness. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45(2):449–453. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey I, Coughlan B, Lydon H, Healy O, Thomas J. Parental satisfaction with early intensive behavioral intervention. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities. 2019;23(3):373–384. doi: 10.1177/1744629517742813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Bettencourt AF. Financial incentives for promoting participation in a school-based parenting program in low-income communities. Prevention Science. 2019;20:585–597. doi: 10.1007/s11121-019-0977-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson J, Symons F, Wolff J. Fidelity and effectiveness of a caregiver mediated compliance training for children with autism spectrum disorder. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2022;44(3):147–164. doi: 10.1080/07317107.2022.2079832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP. Toward effective and preferred programming: A case for the objective measurement of social validity with recipients of behavior-change programs. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2010;3(1):13–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03391754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP. Functional assessment of problem behavior: Dispelling myths, overcoming implementation obstacles and developing new lore. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2012;5(1):54–72. doi: 10.1007/BF03391818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, C. & Williams Awodeja, N. (2022). Culture and language inclusion in the practice of Applied Behavior Analysis: A call to action [Webinar]. Behavioral Health Center of Excellence. https://learning.bhcoe.org/courses/culture-and-language-inclusion-in-the-practice-of-applied-behavior-analysis-a-call-to-action

- Horner, R. H., Albin, R. W., Storey, K., Sprague, J. R., & O’Neill, R. E. (2013). Functional assessment and program development for problem behavior (3rd ed.). Wadsworth.

- Jimenez-Gomez C, Beaulieu L. Cultural responsiveness in applied behavior analysis: Research and practice. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2022;55(3):650–673. doi: 10.1002/jaba.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Services Research. 2007;42(2):727–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornack J, Cernius A, Persicke A. The diversity is in the details: Unintentional language discrimination in the practice of applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(4):879–886. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00377-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. D., Meadan, H., Sands, M. M., Terol, A. K., Martin, M. R., & Yoon, C. D. (2023). The Cultural Adaptation Checklist (CAC): Quality indicators for cultural adaptation of intervention and practice. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 10.1080/20473869.2023.2176966

- Leland W, Stockwell A. A self-assessment tool for cultivating affirming practices with transgender and gender-nonconforming (TGNC) clients, supervisees, students, and colleagues. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(4):816–825. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00375-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luiselli JK. Social validity assessment. In: Luiselli JK, Gardner RM, Bird FL, Maguire H, editors. Organizational behavior management approaches for intellectual and developmental disabilities. Routledge; 2021. pp. 46–66. [Google Scholar]

- Magaña S, Parish SL, Rose RA, Timberlake M, Swaine JG. Racial and ethnic disparities in quality health care among children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities. 2012;50(4):287–299. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-50.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Salzer MS. Who joins support groups among parents of children with autism? Autism. 2007;11(2):111–122. doi: 10.1177/1362361307077506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Wiggins LD, Carpenter LA, Daniels J, DiGuiseppi C, Durkin MS, Giarelli E, Morrier MJ, Nicholas JS, Pinto-Martin JA, Shattuck PT, Thomas KC, Yeargin-Allsopp M, Kirby RS. Racial/ethnic disparities in the identification of children with autism spectrum disorders. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(3):493–498. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez S, Mahoney A. Culturally sensitive behavior intervention materials: A tutorial for practicing behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2022;15(2):516–540. doi: 10.1007/s40617-022-00703-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair L, Adetayo OA. Cultural competence and ethnic diversity in healthcare. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. Global Open. 2019;7(5):e2219. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely L, Gann C, Castro-Villarreal F, Villarreal V. Preliminary findings of culturally responsive consultation with educators. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;13(1):270–281. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00393-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negri, L. M., & Castorina, L. L. (2014). Family adaptation to a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. In J. Tarbox, D. R. Dixon, P. Sturmey, & J. L. Matson (Eds.), Handbook of early intervention for autism spectrum disorders (pp. 117–137). Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4939-0401-3

- Nicolson AC, Lazo-Pearson JF, Shandy J. ABA finding its heart during a pandemic: An exploration in social validity. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2020;13:757–766. doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00517-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padden C, James JE. Stress among parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder: A comparison involving physiological indicators and parent self-reports. Journal of Developmental & Physical Disabilities. 2017;29(4):567–586. doi: 10.1007/s10882-017-9547-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish S, Magaña S, Rose R, Timberlake M, Swaine JG. Health care of Latino children with autism and other developmental disabilities: Quality of provider interaction mediates utilization. American Journal on Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities. 2012;117(4):304–315. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-117.4.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quetsch, L. B., Girard, E. I., & McNeil, C. B. (2020). The impact of incentives on treatment adherence and attrition: A randomized controlled trial of parent-child interaction therapy with a primarily Latinx, low-income population. Children & Youth Services Review, 112, Article 104886. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104886

- Raulston TJ, Hieneman M, Caraway N, Pennefather J, Bhana N. Enablers of behavioral parent training for families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 2019;28:693–703. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1295-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reese RM, Richman DM, Zarcone J, Zarcone T. Individualizing functional assessments for children with autism: The contribution of perseverative behavior and sensory disturbances to disruptive behavior. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities. 2003;18(2):89–94. doi: 10.1177/108835760301800202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A. Disparities in diagnosis and treatment of autism in Latino and Non-Latino white families. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5):e20163010. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley, W. J. (2012). Health disparities: gaps in access, quality, and affordability of medical care. Transactions of the American Clinical & Climatological Association, 123, 167–174. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3540621/ [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rohrer JL, Marshall KB, Suzio C, Weiss MJ. Soft skills: The case for compassionate approaches or how behavior analysis keeps finding its heart. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2021;14(4):1135–1143. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00563-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales R, León IA, León-Fuentes AL. Recommendations for recruitment and retention of a diverse workforce: A report from the field. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2022;16:346–361. doi: 10.1007/s40617-022-00747-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales R, Leon A, Serna RW, Maslin M, Arevalo A, Curtin C. A first look at applied behavior analysis service delivery to Latino American families raising a child with autism spectrum disorder. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2021;14(4):947–983. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00572-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli, B., Turnbull, A., & Higgins, C. (1997). Parent to parent support and health care. Pediatric Nursing, 23(3), 303–306. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9220808/ [PubMed]

- Schultz TR, Schmidt CT, Stichter JP. A review of parent education programs for parents of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities. 2011;26(2):96–104. doi: 10.1177/1088357610397346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz IS, Baer DM. Social validity assessments: Is current practice state of the art? Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24(2):189–204. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seijo R, Gomez H, Freidenberg J. Language as a communication barrier in medical care for Hispanic patients. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1991;13(4):363–376. doi: 10.1177/07399863910134001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaraman M, Fahmie T, Garcia A, Hamawe R, Tierman E. An evaluation of ethnicity-matching for caregiver telehealth training in India. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2022;16:573–586. doi: 10.1007/s40617-022-00738-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M, Pistrang N, Barker C. The benefits of mutual support groups for parents of children with disabilities. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29(1):113–132. doi: 10.1023/A:1005253514140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbe DE. Practicing cultural competence and cultural humility in the care of diverse patients. Focus American Psychiatric Publishing. 2020;18(1):49–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20190041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka-Matsumi J, Seiden DY, Lam KN. The culturally informed functional assessment (CIFA) interview: A strategy for cross-cultural behavioral practice. Cognitive & Behavioral Practice. 1996;3(2):215–233. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(96)80015-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G, Lanza O, Rodríguez FM, Chang A. Quality translations: A matter of patient safety, service quality, and cost-effectiveness. The Permanente Journal. 2006;10(3):79–82. doi: 10.7812/TPP/06-040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BA, LeBlanc LA, Nosik MR. Compassionate care in behavior analytic treatment: Can outcomes be enhanced by attending to relationships with caregivers? Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(3):654–666. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00289-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomeer MB, Moody MD, Yahirun J. Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health and mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Racial & Ethnic Health Disparities. 2023;10(2):961–976. doi: 10.1007/s40615-022-01284-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality. (2014, August). Highlights: 2013 National Healthcare Quality & Disparities Reports (AHRQPub. No. 14–0005–1). https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqr13/2013highlights.pdf

- Vespa, J., Medina, L., & Armstrong, D.M. (2020). Demographic turning points for the United States: Population projections for 2020 to 2060, Current Population Reports, P25–1144, U.S. Census Bureau.