Abstract

Two methods of food presentation (simultaneous and sequential) were compared in an adapted alternating treatment design to determine effects on consumption of target foods for three children with autism in a school setting. Preferred and nonpreferred target foods were nominated by parents, and consumption of reported preferred and nonpreferred foods was directly tested. Preferred and nonpreferred foods were then paired together and assigned to one of two conditions. In the simultaneous condition, bites of preferred and nonpreferred food were presented at the same time, with the nonpreferred food placed behind or inside the preferred food. In the sequential condition, a bite of preferred food was delivered contingent on consumption of a bite of nonpreferred food. Consumption increased in the sequential condition for two out of three participants. Implications for treatment of food selectivity in a school setting are discussed.

This study describes two simple interventions to increase consumption of nonpreferred foods that can be implemented in a classroom setting

These data contribute to previous studies comparing sequential versus simultaneous presentation of foods by conducting the procedures in participants’ natural setting

Results indicate the efficacy of sequential presentation of preferred and nonpreferred foods without the use of escape extinction

Results also suggest further research comparing sequential versus simultaneous food presentation is warranted, given the few direct comparisons that currently exist and their overall mixed results regarding relative efficacy

Keywords: Autism, Food selectivity, Nonextinction, Simultaneous presentation, Sequential presentation

Food selectivity may be defined as consuming a limited variety of foods and avoiding unfamiliar foods, and is commonly reported as a major concern for families with typically developing children and autistic children (Ekstein et al., 2010; Peterson et al., 2016). However, food selectivity is more common in children with autism than neurotypical children (Bandini et al., 2010; Cermak et al., 2010). For example, Bandini et al. (2017) suggest that 46%–86% of children with autism have feeding concerns; by contrast, Benjasuwantep et al. (2013) reported that 27% of typically developing children may have feeding concerns. These concerns can frequently appear as rigidity surrounding food choices (Peterson & Ibañez, 2018), which may include refusing foods based on texture, brand, color, smell, taste, or appearance (Hubbard et al., 2014). These factors can lead to nutritional deficiencies and affect growth and development (Bandini et al., 2010; Ekstein et al., 2010). For example, Suarez and Crinion (2015) found that children who consumed fewer than 20 different food items per month consumed less fruits and vegetables than children with a wide food repertoire (i.e., children who consumed more than 20 foods per month). Hyman et al. (2012) found that children with an autism diagnosis lacked certain vitamins and minerals such as vitamins K, C, D, E, potassium, and fiber. The lack of essential nutrients can negatively affect growth and development (Bandini et al., 2010; Ekstein et al., 2010). In some severe cases, children have been diagnosed with scurvy due to nutritional deficiencies (Swed-Tobia et al., 2019), which demonstrates that diverse diet is imperative.

Feeding difficulties can be exacerbated by medical and biological factors such as difficulty chewing or swallowing, gastroesophageal reflux disease, heartburn, oral hypersensitivity, or failure to thrive (Nadon et al., 2011; Piazza & Carroll-Hernandez, 2004; Rommel et al., 2003). Potential medical factors should be ruled out or addressed with a multidisciplinary team before attempting behavioral intervention for food selectivity. Food selectivity has also been characterized as a form of change-resistant behavior (Crowley et al., 2020). Change-resistant behavior such as rigid routines surrounding mealtime and persistence in consuming the same limited number of foods can be common in children with an autism diagnosis. In addition, environmental factors such as removing nonpreferred foods, providing parental attention, or accessing tangibles such as preferred foods or toys may also affect food consumption and maintain inappropriate mealtime behavior that occurs when nonpreferred foods are presented (Piazza, 2008).

There are a number of behavior-analytic interventions available to increase consumption of novel or nonpreferred foods. Research on these interventions is often conducted in clinical settings designed to provide intensive feeding intervention (e.g., Piazza et al., 2002, 2003; Rubio et al., 2021; Ibañez et al., 2020). For example, Saini et al. (2019) reported that 68% of the functional analyses of inappropriate mealtime behavior they reviewed occurred in a clinical setting, and only 15% occurred in a naturalistic setting. Ledford et al. (2018) reported that only 12% of feeding interventions they reviewed occurred in a school setting. Given that many children with autism receive services in naturalistic settings like their schools and homes, it is important to explore interventions for food selectivity in these settings. This is especially true for children with mild food selectivity who may not require intensive intervention in a specialized clinic or hospital setting.

Simultaneous presentation and sequential presentation of foods are two interventions that rely on relatively simple antecedent or consequence arrangements, and may therefore be feasible to implement in naturalistic settings. Simultaneous presentation of preferred and nonpreferred foods is an antecedent modification that involves placing a preferred food (e.g., chip) side by side or inside a nonpreferred food (e.g., banana) and offering the two foods together (e.g., Ahearn, 2003; Buckley & Newchok, 2005; Najdowski et al., 2012; Piazza et al., 2002). For example, Ahearn (2003) increased consumption of vegetables (a nonpreferred food) for a teenager with autism by simultaneously presenting a bite of vegetable topped with a condiment such as BBQ sauce or ranch dressing (preferred foods). Ahearn observed robust treatment effects with the simultaneous-presentation treatment, and no other treatment components were necessary. Sequential presentation, by contrast, involves providing a bite of preferred food after (i.e., contingent upon) accepting a bite of nonpreferred food, and can thus be conceptualized as differential reinforcement (e.g., Kern & Marder, 1996; Piazza et al., 2002; Pizzo et al., 2012; Whelan & Penrod, 2019).

Direct comparisons of simultaneous and sequential food presentation have produced mixed results regarding efficacy in increasing consumption of reportedly nonpreferred foods, and how often either treatment is effective without escape extinction. For example, Kern and Marder (1996) compared simultaneous and sequential presentation with escape extinction in a multielement design with a young child with autism. They found that consumption of nonpreferred foods eventually increased in both conditions, although it was more quickly achieved in the simultaneous condition. However, nonpreferred fruits were targeted in the simultaneous condition and nonpreferred vegetables were targeted in the sequential condition, making it unclear whether responding was a function of the type of presentation itself or a preference for fruits over vegetables. In addition, escape extinction in the form of nonremoval of the spoon and re-presentation of expelled bites were included as treatment components in both conditions, so it is unknown whether the same effects would have been observed in either condition without extinction.

VanDalen and Penrod (2010) and Piazza et al. (2002) both addressed the limitations of Kern and Marder (1996) by randomly assigning foods from multiple food groups to simultaneous and sequential presentation conditions, and by directly comparing the two conditions without escape extinction in a multielement design. Piazza et al. found that simultaneous presentation without escape extinction was more effective in increasing consumption of nonpreferred foods for two out of three participants. The third participant, however, did not respond to either treatment until physical guidance and escape extinction in the form of re-presentation of expelled bites was added. When these components were introduced, consumption of nonpreferred foods increased in the simultaneous condition only. By contrast, VanDalen and Penrod (2010) found that neither sequential nor simultaneous presentation was effective without escape extinction for their two young participants with autism. Once escape extinction was introduced, one participant responded more quickly to sequential presentation and the other responded more quickly to simultaneous presentation. VanDalen and Penrod also noted that participants began eating their food sequentially during the simultaneous condition (i.e., participants separated the preferred and nonpreferred foods, and ate the nonpreferred bite first, followed by the preferred bite), suggesting that sequential presentation was preferred by participants even though both interventions were effective.

Given these mixed results regarding relative efficacy of simultaneous versus sequential presentation and the limited number of studies in which both treatments were evaluated without escape extinction, additional comparisons of these interventions are necessary. Additional evaluations of food selectivity interventions in naturalistic settings are also important. The purpose of the current study was to extend Piazza et al. (2002) and VanDalen and Penrod (2010) by directly comparing simultaneous and sequential presentation without escape extinction for three children with autism in a school setting. In addition, researchers included measures of social validity from parents, measures of treatment integrity, and conducted posttreatment observations during typical classroom lunch time for one participant to determine the extent to which eating nonpreferred foods maintained in the natural environment in the absence of treatment.

Method

Participants

Four children ranging in age from 6 to 13 years who attended a private day school for children with autism were recruited to participate. Three of those children completed the study; the fourth was dismissed following consumption of all target foods during baseline. Participants were recruited based on teacher, parent, and school nurse reports of food selectivity. A school-wide email was distributed to all clinical and nursing staff describing the inclusion criteria for the study and encouraging them to share the information with any parents who may be interested in having their child participate.

To meet inclusion criteria, participants had to have a limited food repertoire, defined as regularly consuming fewer than 10 foods in total, not including unhealthy or nonnutritious foods (e.g., chips, cookies). In addition, participants must have demonstrated limited consumption of two or more of the five common food groups (i.e., vegetables, fruits, protein, grains, and dairy). Participants also had to (1) consume all calories orally; (2) eat a variety of textures (e.g., crunchy, chewy) within their limited repertoire of foods; (3) maintain appropriate weight and growth; and (4) have no history of choking, aspiration, failure to thrive, or other medical concerns related to feeding or chewing, based on their pediatrician’s report. Exclusion criteria included participants who ate more than 10 foods (beyond junk food or nonnutritious food), participants who ate multiple foods from all major food groups, and participants who had any reported history of choking, aspiration, being underweight, being diagnosed with failure to thrive, or being diagnosed with any other medical conditions related to feeding or chewing. Participants who were admitted to the study were subsequently excluded if they consumed more than 80% of nonpreferred foods during baseline. Each participant’s current food repertoire was determined by parent and staff report; current weight and medical history was determined by the school nurse who had access to participants’ medical files as part of the documentation provided by parents of all children enrolled in the school. Last, participants also had to have at least one objective in their individualized education plan (IEP) targeting consumption of novel foods. We did not receive referrals for any children who did not meet all inclusion criteria.

Aaron was a 13-year-old ambulatory white male with autism who communicated vocally in short sentences as well as with a speech-generating device (SGD). He followed simple one- and two-step instructions. Aaron’s parents reported that he regularly consumed eight foods, mostly consisting of starches, and that they wished to expand his repertoire of proteins and fruits. According to school staff reports and direct observation, when presented with novel foods, Aaron shook his head, engaged in vocal protests, and pushed the food away.

Eva was a 9-year-old ambulatory white female with autism who communicated using an SGD and followed simple one-step instructions. Eva’s parents reported that she regularly consumed nine foods, mostly consisting of fruits, and that they wished to expand her repertoire of vegetables and proteins. According to parent and school staff reports, when presented with novel foods, Eva cried, screamed, pushed the food away, and engaged in self-injurious behavior (SIB; e.g., hitting self with a closed fist or with an object.)

Ben was a 6-year-old ambulatory white male with autism who communicated using single word approximations or by pushing single buttons on his SGD, and followed simple one-step instructions. Ben’s parents reported that he regularly consumed six foods, mostly consisting of candy or snack foods like crackers, and that they wished to expand his repertoire of fruits and vegetables. According to parent and school staff reports, when presented with novel foods, Ben engaged in vocal protests, pushing the food away, or pushed the adult who presented the food.

Brooke was a 15-year-old ambulatory white female with autism who communicated vocally in complex sentences and followed multistep instructions. Brooke’s parents reported that she regularly consumed nine foods, primarily consisting of starches. According to parent reports, when presented with novel foods, Brooke engaged in vocal protests, pushed the food away, or engaged in SIB (e.g., hitting and biting self). During baseline, Brooke consumed 92%–100% of reported nonpreferred foods presented over four baseline sessions, and thus, was excluded as a study participant.

Setting and Materials

Therapists conducted all sessions in the participant’s classroom, which consisted of individual learning areas for four to six students, and a community space in the middle of the classroom. All participants received 1:1 instruction for the entire school day as part of the school’s typical model, and each participant’s case was overseen by a BCBA. Sessions took place at the participant’s regularly assigned desk with a table, chairs, novel and preferred foods, and eating utensils.

Selection of Target Foods

For all participants, we selected target foods based on parent report of foods that were not regularly consumed and which they wished their child would consume (see Table 1). Because our inclusion criteria specified that participants must already consume all calories orally, eat a variety of textures, and have no history of choking or aspiration concerns reported by their doctors, we did not specifically evaluate participants’ chewing skills. However, we selected target foods that were similar or nearly identical in texture to foods that participants already safely consumed, or were foods that participants had previously consumed but now rejected. Both preferred and nonpreferred foods were cut or broken into 2 cm x 2 cm pieces for foods that were naturally larger than 2 cm (e.g., apple, pear, scrambled eggs, Tostitos chips). Foods that were naturally bite-sized (e.g., Goldfish crackers, individual pieces of popcorn) were presented as individual pieces.

Table 1.

Parent Reported Consumption of Foods

| Participant | Regularly consumed | Occasionally consumed |

|---|---|---|

| Aaron | Tostitos chips, toast and butter, Goldfish crackers, green apples, McDonald’s fries, Scali bread, Newman’s Own Supreme Pizza, Newman’s Own Cheese Pizza | Carrot, celery, cucumber, broccoli, kale, spinach |

| Eva | Chips, crackers, yogurt, ice cream, apple, peach, banana, orange, pineapple | Carrots, broccoli |

| Ben | Chocolate, chewy candy, yogurt, Goldfish crackers, Cliff bar, chicken | Apple, banana, clementine |

Textures that Aaron already consumed included firm foods like apples, crunchy foods like Tostitos chips and Goldfish crackers, chewy foods like pizza, and softer foods like Scali bread and McDonald’s French fries. Target foods selected for Aaron included smooth peanut butter, baked French fries (not from McDonald’s), fresh nectarine, and fresh pear. Textures that Eva already consumed included crunchy foods like chips and popcorn, creamy foods like ice cream and yogurt, firm foods like apples, and soft foods like bananas. Target foods selected for Eva included scrambled egg prepared with a pinch of salt, baked salted kale chips, raw yellow pepper slices, and baked seasoned pizza crust. We selected baked seasoned pizza crust because Eva’s parents requested that we target pizza, but also reported that she did not like to eat multiple foods together (i.e., cheese and toppings on pizza) and frequently took her food apart. We therefore started with the base of pizza crust, with the intention that her parents could then add one topping at a time to the baked crust for her to consume at home. Textures that Ben already consumed included crunchy foods like Goldfish crackers, chewy foods like a Cliff bar or gummy candy, creamy foods like yogurt, firm foods like apples, and on occasion, softer foods like bananas. Target foods selected for Ben were baked Brussel sprouts, baked sweet potato, fresh blueberries, and fresh strawberries. Ben’s parents prepared both vegetables as they would at home (baked with olive oil and light seasoning) and sent them into school several times a week for Ben’s sessions. The researchers warmed them in the microwave before sessions. All other foods (e.g., scrambled eggs for Eva; baked French fries for Aaron) were prepared at school by the first author.

Therapists and Observers

All sessions were conducted by three school employees who were trained 1:1 ABA therapists. The therapists received general ABA training upon hiring, at least 10 hr of student-specific training for each child they worked with, and at least 24 hr per year of additional required school-wide trainings. Each therapist regularly served meals and snacks to the participants as part of their typical job duties. All staff members at the school received regular state-mandated training in CPR, first aid including the Heimlich maneuver, how to recognize signs of an allergic reaction, and emergency epi-pen administration. Thus, all sessions were conducted by 1:1 ABA therapists who knew the participant well, worked with them often outside of research sessions, was already responsible for monitoring them while eating at school, and had received training in first aid related to choking. As part of the school’s typical daily functioning, multiple registered nurses were on site each day and available immediately via intercom or walkie-talkie call.

Aaron and Eva’s sessions were conducted by the first author, who was an employee of the school as well as a 2nd-year graduate student in behavior analysis with several years of experience working as an ABA therapist. They conducted this study as their graduate thesis project. The first author was trained in conducting the study procedures by the third author, who was a BCBA-D (board certified behavior analyst) graduate faculty advisor overseeing the thesis project. Training included discussing the procedures of each phase, modeling them, and having the first author role-play them with feedback (i.e., behavioral skills training [BST]). Ben’s sessions were conducted by two of his ABA therapists, with training and guidance from the first author. This involved the first author conducting BST with Ben’s therapists, as well as viewing videotapes of their sessions and providing feedback. Ben’s ABA therapists both had several years of experience working in ABA, and one of them was also a graduate student in behavior analysis and special education.

Sessions for all participants were overseen by the participant’s school-based BCBA as well as the third author. A school nurse also served on the first author’s thesis committee, and reviewed the study procedures and inclusion criteria before study implementation. Institutional review board approval was obtained before the study from the graduate program attended by the first author, and informed consent was provided by all participants’ parents.

Sessions were conducted during naturally occurring morning or afternoon snack times (e.g., between 9:30 and 10:30 a.m. for morning snack or 2:00 and 3:00 p.m. for afternoon snack). Sessions did not exceed 10 min each, and one to two sessions were conducted during each designated snack time (morning and afternoon), for a total of two to four sessions per day, 3–4 days per week. Because sessions were conducted during regularly scheduled snack times, participants did not miss any of their other typical daily educational activities. Access to preferred food items used in treatment sessions was restricted during other snack and lunch times at school, but was not restricted at home.

Response Definitions, Measurement, Interobserver Agreement (IOA), and Procedural Integrity (PI)

Consumption was defined as the participant swallowing the entire bite of food within 30 s of placing it in their mouth. A bite was only scored as consumed if the entire piece was consumed (i.e., consumption was not scored if the participant swallowed only a portion of the bite). Bites of food were presented one at a time. Percentage of bites consumed each session was calculated by dividing the number of bites consumed by the total number of bites presented. Once a participant placed a bite of food in their mouth, the researcher visually monitored the participant during the duration of the 30 s. A mouth check was conducted after 30 s to determine whether the food was consumed (i.e., swallowed) such that no visible pieces of food remained. Expulsion of food was defined as the participant emitting food larger than the size of a pea past the plane of the lips. Packing was defined as the participant holding or pocketing the bite of food in their cheek for 30 s or longer. Expulsion and packing never occurred for any participant. In addition, there were no instances in which food was placed in the participant’s mouth but not swallowed within 30 s (i.e., participants either declined to place the food in their mouth, or placed it in their mouth and then always chewed and swallowed it within 30 s).

Trial-by-trial IOA data were scored by having a second observer view videotaped sessions and score whether each bite presented was consumed or not, and whether expulsion or packing occurred for each bite. The total number of agreements was then divided by the total number of agreements plus disagreements and converted to a percentage. Observers scored procedural integrity (PI) by viewing videotaped sessions and recording whether the therapist presented the correct foods that were assigned to that condition, whether the correct foods were paired together for each trial during simultaneous sessions, and whether the correct preferred food was delivered following consumption (or withheld following nonconsumption) for each trial in sequential sessions. Information about which foods were assigned to which condition was printed on the PI sheet filled out by the second observer. The number of correctly performed steps was divided by the total number of steps and converted to a percentage. IOA and PI were collected for 30% of baseline and treatment sessions for Aaron and Ben, and 30% of treatment sessions for Eva.1 IOA for consumption, expulsion, and packing was 100% across all participants; PI was also 100% across all participants.

Experimental Design

We compared consumption during the simultaneous versus sequential condition using an adapted alternating treatments design (Sindelar et al., 1985; Cariveau & Fetzner, 2022), which included an initial baseline and final, “best treatment” phase (e.g., Cengher et al., 2020; Devlin et al., 2011; Musti-Rao & Plati, 2015; Tincani, 2004). Sessions of simultaneous versus sequential food presentation were randomly alternated, with session type determined by a random number generator. The final best treatment phase involved moving target foods from the condition with lower consumption to the condition with high, stable consumption, as described by Piazza et al. (2002). The purpose of this phase was to strengthen the demonstration of functional control by further evaluating whether foods that were previously refused in one condition would be consumed when they were presented using the method associated with high rates of consumption.

Procedures

Parent Survey

After consent was obtained for participants, the first author sent a survey to participants’ parents with open-ended questions that asked them to describe what foods their child regularly, occasionally, or never consumed, and what foods the parents would like them to consume (see Table 1). We used the results of this survey to identify potential preferred foods to use in each condition (i.e., foods that were reported to be regularly consumed), as well as potential novel foods to target (i.e., foods that were reported not to be consumed).

Selection of Preferred Foods (Preference Assessment)

Therapists conducted a paired stimulus preference assessment (Fisher et al., 1992) with six potentially preferred food items identified on the parent survey as foods the participant regularly consumed. Participants were seated at their desk for the preference assessment. Each trial consisted of the therapist presenting two different food items on a plate in front of the participant and verbally instructing them to “pick one.” If the participant selected and consumed one of the foods within 30 s, that selection was recorded and the next trial was presented. If the participant did not consume one of the foods within 30 s, that trial was scored as neither food being consumed, the plate was removed, and the next trial was presented. No praise or other comments were provided for consuming the foods.

Each of the six foods was presented 10 times across 30 total trials (two foods were presented each trial). Each food was presented with each other food in both the left and right positions (e.g., Tostitos chip on the left and Goldfish cracker on the right; Goldfish cracker on the left and Tostitos chip on the right). Food items that were selected in 50% or more of opportunities were used as preferred foods for the interventions. These included Newman’s Own Supreme Pizza, a green apple, Goldfish crackers, and Tostitos chips for Aaron; Cheetos, sour cream and onion chips, popcorn, and salami for Eva; and Goldfish crackers and baked coconut chicken for Ben. The coconut chicken was prepared at home by Ben’s parents and sent in to school for each session. Ben only selected two foods out of the six presented.

Baseline

Each session included three bite presentations each of four different target foods in a randomized order, for a total of 12 bite presentations per session. Therapists presented one bite at a time directly on a plate or on a fork placed on a plate approximately 15 cm away from the participant, along with the verbal instruction to, “take a bite.” The therapists did not hold the food to the participant’s mouth, but instead ensured it was visible and within reach of the participant. This allowed the participant to move toward the food if desired, or to pick up the food (or fork) and self-feed. All bites that were consumed were self-fed (i.e., researchers never fed participants). If the participant placed the bite in their mouth within 30 s, therapists provided brief verbal praise, and set the timer for 30 s to allow time for the participant to consume the bite. Therapists conducted a mouth check after 30 s to determine whether consumption occurred. No other consequences were provided for consuming target foods during baseline. If the bite was not placed in their mouth within 30 s, it was removed and a different target food was presented. Across participants, if any dangerous problem behavior occurred (e.g., aggression or SIB), the session would have been terminated; however, this never occurred for any participant. Baseline sessions continued until the first author identified four target foods for each participant that were not consumed across at least two sessions.

Treatment Comparison

Two target foods were assigned to each condition for each participant. For Aaron, peanut butter and French fry were assigned to the simultaneous condition; nectarine and pear were assigned to the sequential condition. For Eva, scrambled eggs and kale chips were assigned to the simultaneous condition; yellow pepper and baked pizza crust were assigned to the sequential condition. For Ben, Brussel sprouts and sweet potato were assigned to the simultaneous condition; blueberry and strawberry were assigned to the sequential condition. Each target food was paired with a specific preferred food identified in the preference assessment. These pairings remained the same throughout the study, but the order of pairings was randomized for each session. Foods that could be easily physically combined were assigned to the simultaneous condition (e.g., peanut butter spread on a piece of apple). Foods that were not easy to physically combine were assigned to the sequential condition (e.g., yellow pepper and Cheetos). Sessions in both conditions consisted of three bite presentations of each of the two target foods in that condition (e.g., three presentations of yellow pepper and three presentations of pizza crust, in a random order), for a total of six bite presentations. A session was complete when all six bites had been presented, which usually took approximately 6–10 min (taking into consideration the time needed for the therapist to prepare bites and collect data). If the food was pushed away, the therapist kept it within reach. If the food was pushed off the table (and consequently fell onto the floor), a new bite of the same food pairings was presented. If any dangerous problem behavior occurred (SIB, aggression, or elopement), the session would have been terminated; however, this did not occur for any participant.

Simultaneous Presentation

In the simultaneous condition, a bite of preferred food and bite of target food were combined together and presented as one bite. Aaron’s food pairings were peanut butter (target) with apple (preferred) and French fry (target) with pizza (preferred). The apple and peanut butter were combined by placing a dollop of peanut butter on a bite of apple. The peanut butter portion was a half-teaspoon sized dollop; the apple was cut in approximately a 2 cm x 2 cm bite. The bites of French fry and pizza were combined by placing a French fry behind a bite of pizza on a fork. The French fry and pizza were also both cut to approximately 2 cm x 2 cm.

Eva’s food pairings were scrambled eggs (target) with salami (preferred) and kale chips (target) with popcorn (preferred). The scrambled eggs and salami were combined by placing a bite of scrambled eggs behind a bite of salami on a fork. The scrambled eggs and salami were both cut to approximately 2 cm x 2 cm. The kale chips and popcorn were combined by inserting a piece of kale chip into the folds of a piece of popcorn. The kale chip was small enough to fit inside the folds of an individual popcorn piece.

Ben’s food pairings were Brussel sprouts (target) with coconut chicken (preferred) and sweet potato (target) with Goldfish crackers (preferred). Brussel sprouts and coconut chicken were combined by placing a bite of a Brussel sprout behind a bite of coconut chicken on a fork. Both foods were cut to approximately 2 cm x 2 cm. Sweet potato and Goldfish crackers were combined by breaking a Goldfish cracker in half and placing a small amount of sweet potato inside it. The amount of sweet potato was small enough to fit in a broken Goldfish cracker; the pieces were then stuck back together and presented as one cracker.

For all bite presentations, the target food was visible to the therapist and likely visible to the participant, and they were not prevented from looking at or examining the food combination. Each bite presentation began with the therapist placing a bite of the food combination on a plate or on a fork on the plate in front of the participant, with the verbal instruction to, “take a bite.” If the participant did not place the bite inside their mouth within 30 s, the therapist removed the simultaneous bite and presented the next combination of target and preferred food. If the participant placed the bite in their mouth within 30 s of presentation, the therapist provided brief praise and set another timer for 30 s to observe the participant. The therapist recorded whether the bite was consumed within that time, and whether any packing or expulsion occurred. Consumption was confirmed via a mouth check 30 s after the participant placed the bite inside their mouth. Packing or expulsion never occurred for any participant. If the participant tried to consume only the preferred food and not the target food, the bite was removed, reassembled on the fork or plate, and offered again for 30 s. This only occurred during one session for one bite presentation.

Sequential Presentation

In the sequential condition, a bite of a target food and a bite of preferred food were placed on two different forks (for fork foods) or on two different plates (for finger foods). Before the session, the therapist verbally explained the condition contingencies to the participant (e.g., “first blueberry, then Goldfish” or a similar statement). The fork or plate with the nonpreferred food was presented directly in front of the participant, whereas the fork or plate with the preferred food remained in view on the table but out of reach, and the participant was instructed to “take a bite.” Procedures were otherwise identical to the simultaneous condition, with the exception that the preferred food was delivered contingent on consumption of the target food. If preferred food was delivered, the next bite of target food was presented after participants finished consuming the preferred food. Consumption of preferred food never took more than 1 min.

Aaron’s food pairings were Goldfish crackers (preferred) provided contingent on consumption of nectarine (target) and Tostitos chips (preferred) provided contingent on consumption of pear (target). The Goldfish cracker was presented as one single cracker; the bite of nectarine was cut to approximately 2 cm x 2cm. The Tostitos chip was broken into approximately 2 cm x 2 cm; the bite of pear was also cut to approximately 2 cm x 2cm.

Eva’s food pairings were Cheetos (preferred) provided contingent on consumption of yellow pepper (target) and a sour cream and onion chip (preferred) provided contingent on consumption of a bite of baked pizza crust (target). Cheetos were presented as a single Cheeto; the bite of yellow pepper was cut to approximately 2 cm x 2 cm. The sour cream and onion chip was presented as a single chip; the bite of baked pizza crust was cut to approximately 2 cm x 2 cm.

Ben’s food pairings were Goldfish crackers (preferred) provided contingent on consumption of blueberry (target) and coconut chicken (preferred) provided contingent on consumption of strawberry (target). The Goldfish crackers were presented as a single cracker; the blueberry was presented as a single blueberry. The bite of coconut chicken was cut to approximately 2 cm x 2cm; the bite of strawberry was also cut to approximately 2 cm x 2 cm.

Best Treatment: Sequential Presentation Only

We included this phase to evaluate whether sequential presentation was effective in increasing consumption of target foods that had previously been refused in the simultaneous condition. During this phase, the simultaneous condition was discontinued and the foods that had been assigned to that condition were instead presented using the sequential-condition procedures. This occurred following stable, high rates of consumption for foods targeted in the sequential condition, and low rates of consumption for foods targeted in the simultaneous condition. For example, Eva’s simultaneous pairing of scrambled egg (target) and salami (preferred) were now presented using sequential-condition procedures, with a bite of scrambled egg by itself on a fork and piece of salami on a plate out of reach, but within view of the participant. Salami was delivered contingent on consumption of the egg. The procedures were identical to the sequential condition described above.

Social Validity Survey

The first author measured the social validity of these procedures through surveys to parents and teachers of the participants. Four statements were included: (1) I think that eating a wider variety of foods is important; (2) I think that this is an important skill for my student/child to have; (3) I think that the procedures used were acceptable; and (4) I believe that this intervention made positive changes to the behavior of my student/child. The questions were scored on a 1–7 Likert-type scale with 1 indicating “strongly disagree” and 7 indicating “strongly agree.”

Results

Figure 1 displays the preference assessment results for preferred food for all participants. Aaron consumed Tostitos chips in 80% of trials, green apples in 70% of trials, Newman’s Own Supreme Pizza in 60% of trials, and Goldfish crackers in 50% of trials. Eva consumed sour cream and onion chips in 80% of trials, Cheetos in 80% of trials, popcorn in 70% of trials, and salami in 70% of trials. Ben consumed Goldfish crackers in 100% of trials and coconut chicken in 80% of trials. He did not consume any other foods.

Fig. 1.

Preference Assessment Results for Aaron, Eva, and Ben

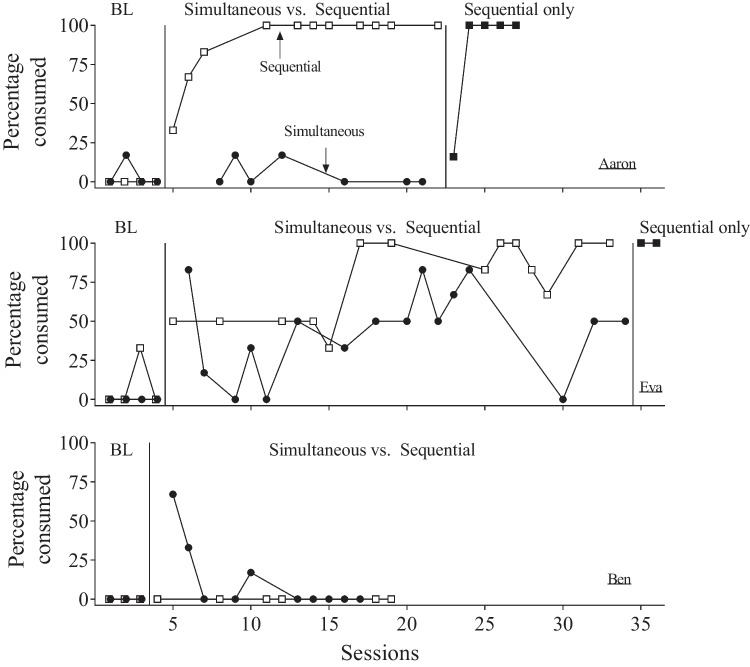

Figure 2 displays the results of the treatment comparison for all three participants. Baseline data for all participants are separated to show consumption of foods by the conditions they were eventually assigned to (although they were not yet assigned to any condition during baseline). The first panel shows results for Aaron. During baseline, Aaron’s consumption of all target foods was low. He did not consume any of the foods that were later assigned to the sequential condition, and he consumed 0%–17% of foods that were later assigned to the simultaneous condition (mean: 4.25%). During treatment for Aaron, there was an immediate increase in percentage of consumption in the sequential condition with 100% of target foods (pear, nectarine) being consumed by the fourth treatment session. Consumption of these foods remained stable at 100% for an additional seven sessions. By contrast, consumption in the simultaneous condition occurred at low rates and remained near zero (mean: 4.8%; range: 0%–17%). During the final best treatment phase when target foods from the simultaneous condition (peanut butter, French fry) were introduced in the sequential condition, Aaron’s consumption quickly increased to 100% and remained stable at this level. The preferred foods associated with each target food remained the same during this phase (i.e., apple was delivered contingent on consumption of peanut butter, and pizza was delivered contingent on consumption of a French fry).

Fig. 2.

Treatment Comparison for Aaron, Eva, and Ben

The second panel of Fig. 2 displays the results for Eva. Eva’s consumption of all target foods remained low during baseline. She did not consume any foods that were later assigned to the simultaneous condition, and she consumed 0%–33% of foods that were later assigned to the sequential condition (mean: 8.25%). During treatment for Eva, there was an immediate increase in consumption in the sequential condition (yellow pepper, baked pizza crust) that persisted at a moderate level and then increased to a high level by the end of treatment (mean: 76%; range: 33%–100%). There was also an immediate increase in consumption of target foods in the simultaneous condition (eggs paired with salami, and kale chip paired with popcorn), but this increase did not persist. Consumption in the simultaneous condition quickly decreased after the first session and remained variable (mean: 43.6%; range: 0%–83%). During the final best treatment phase when eggs and kale chips from the simultaneous condition were introduced in the sequential condition, Eva’s consumption of these foods increased to 100% for two consecutive sessions. The preferred foods associated with each target food remained the same during this phase (i.e., salami was delivered contingent on Eva’s consumption of eggs, and popcorn was delivered contingent on Eva’s consumption of a kale chip).

The third panel of Fig. 2 displays the results for Ben. During baseline, Ben displayed zero percentage of consumption for all target foods across three sessions. During treatment, there was an initial increase in the simultaneous condition (Brussel sprouts paired with chicken, and sweet potato paired with Goldfish), but this increase did not persist. Percentage of consumption in the simultaneous condition decreased to zero levels and remained at zero throughout treatment (average: 11.7%; range: 0%–17%). Consumption never occurred in the sequential condition (blueberries and strawberries). Treatment for Ben was terminated after stable levels of zero responding occurred in both conditions.

Table 2 presents the results from the social validity survey, which indicated that all parents agreed that the goals and procedures were acceptable for their child. The statement, “I think that eating a wider variety of foods is important” scored an average of 6.3; the statement, “I think that this is an important skill for my student/child to have” scored an average of 6.7. The statement, “I think that the procedures used were acceptable” scored an average of 6.6. When asked about the outcomes achieved during treatment, Aaron and Eva’s parents provided a score of 7 for the statement, “I believe that this intervention made positive changes for my child”; Ben’s parents provided a score of 2.

Table 2.

Social Validity Results

| Question | Score provided by participant’s parents | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Aaron | Eva | Ben | |

| I think that eating a wider variety of foods is important | 7 | 4 | 7 |

| I think that this is an important skill for my child to have | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| I think that the procedures used were acceptable | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| I believe that this intervention made positive changes to the behavior of my child | 7 | 6 | 2 |

Questions were presented with a Likert scale of 1–7, with 1 being strongly disagree and 7 being strongly agree

Discussion

Sequential presentation was more effective than simultaneous presentation in increasing consumption of target foods for two out of three participants with autism in a school setting. Furthermore, both interventions were implemented in participants’ classrooms during their typically scheduled snack times by the 1:1 ABA therapists who regularly worked with them. Even though one participant did not demonstrate a favorable response to either treatment, social validity scores suggest that all caregivers agreed the target behavior was socially significant, the procedures were acceptable (ethical and humane), and two out of three of participant’s parents were satisfied with the results. Aaron’s teachers reported that he continued to eat all mastered foods 1 month after treatment, and that his food repertoire had expanded to include eating peanut butter with celery, different brands of French fries beyond those we targeted during treatment, salad (which we had not targeted and he never consumed before treatment), and a different brand of frozen pizza (which we had not targeted and he never consumed before treatment). This occurred without explicit transfer of the intervention to other caregivers.

Our results contribute to the simultaneous versus sequential presentation literature in several ways. Many examples of behavior-analytic feeding interventions are conducted in clinical or hospital rather than naturalistic settings (Ledford et al., 2018; Saini et al., 2019). It is important to evaluate the generality of these interventions in natural, less controlled settings where many children with autism receive services, especially for children who experience mild food selectivity that does not warrant referral to an intensive feeding program. The procedures themselves were relatively easy to implement in a classroom setting and to train other staff to implement as well. We are also not aware of any examples in which simultaneous and sequential presentation were directly compared and sequential presentation was found to be more effective. These results differ from those of Piazza et al. (2002), which found that simultaneous presentation was more effective without escape extinction for two participants and with escape extinction for a third participant. Other direct comparisons have found both treatments to be similarly effective (e.g., Kern & Marder, 1996; VanDalen & Penrod, 2010).

There are few evaluations of simultaneous versus sequential presentation in the absence of escape extinction, and in some cases these interventions have only been effective once escape extinction was added to the treatment package (e.g., VanDalen & Penrod, 2010). Thus, the current study also contributes to the literature by adding to the few studies that have found sequential presentation to be effective without escape extinction (Pizzo et al., 2012; Whelan & Penrod, 2019). Evaluating the necessity of escape extinction as part of a treatment package with simultaneous or sequential presentation is important because escape extinction may be difficult to carry out in natural settings where treatment fidelity is not frequently monitored (Peterson & Ibañez, 2018). It is possible there could be side effects associated with escape extinction, including an increase in emotional responding (e.g., crying), extinction bursts in which inappropriate mealtime behavior temporarily increases or intensifies, or expulsion of the food (Piazza et al., 2003; Sevin et al., 2002; Woods & Borrero, 2019).

There are a few reasons why sequential presentation may have been more effective than simultaneous presentation for Aaron and Eva. First, it is important to note that participants in the current study already consumed a variety of foods orally prior to intervention, and were not at risk for lack of growth due to poor nutrition. Their parents had never referred them for any feeding services, or been advised by their pediatricians to seek feeding care. In other words, these were not children who were experiencing severe feeding-related difficulties, but rather children with mild food selectivity whose parents wished to expand their current food repertoires. The sequential condition included a relatively simple reinforcement contingency; it is possible that participants’ current food repertoires and history of consuming foods orally contributed to the efficacy of this condition. It is also possible that participants already had a history of experiencing differential reinforcement in general, as experienced in the sequential condition. Likewise, it is important to note that this intervention would not be appropriate for children with more significant feeding challenges, such as those diagnosed with failure to thrive or severe nutritional and calorie deficiencies. In addition, we do not recommend using this intervention for children who have a history of choking or aspiration, or for children with limited experience consuming food by mouth (e.g., children who are dependent on a gastrostomy tube).

It is less likely that differential reinforcement alone would be effective in increasing consumption of novel foods for children with severe feeding difficulties (Piazza et al., 2003; Patel et al., 2002).

Piazza et al. (2002) noted that the foods two of their participants consumed in the simultaneous condition were foods that were readily combined into a single bite (e.g., salad dressing on a vegetable; broccoli inserted into a hole in a piece of apple, such that the broccoli was not visible). These authors suggested it is possible that the ease with which foods were combined contributed to the efficacy of the simultaneous condition. However, Aaron and Eva’s simultaneous foods were also easily combined into a single bite (e.g., peanut butter smeared on an apple for Aaron; a kale chip broken up and placed inside a piece of popcorn for Eva). It is possible that consuming the preferred and nonpreferred foods together altered the appetitive properties of the preferred food in a way that was aversive and thus weakened any establishing operation for the preferred food (rather than the preferred food masking the taste or reducing the salience of the aversive properties of the nonpreferred food). It is also possible that Aaron and Eva disliked eating multiple foods together in one bite (regardless of taste), and thus more readily consumed foods in the sequential condition when foods were presented as separate bites. For Eva in particular, it was reported that she often took foods apart to eat them separately; it is possible that this historical preference for consuming foods individually contributed to a lack of responding in the simultaneous condition. Last, it is possible that the brief explanation of the contingency in the sequential condition may have contributed to initial rates of responding for Aaron and Eva. A similar description was not provided in the simultaneous condition because the preferred food was presented noncontingently. However, once participants experienced several sessions of each condition, it is likely that any responding came under control of directly experiencing the contingencies in each condition.

There are several limitations of the current study to be noted, and similarly several important potential areas for future research. The first limitation is that we did not specifically collect data on chewing of target foods. Although all participants were selected in collaboration with the school nurse, had been safely eating meals at school for several years, and had no reported history of chewing difficulties, it is possible that participants were not adequately chewing some of the target foods. This concern could be eliminated in future studies by gathering data on adequate chewing of each bite.

A second limitation is that foods were not randomly assigned to treatment conditions. Although random assignment would have enhanced the rigor of our experimental design, we instead assigned foods based on the ease with which they could be physically combined (for the simultaneous condition), and assigned those that could not be easily combined to the sequential condition. This coincidentally resulted in foods that ranked higher in the preference assessment being assigned to the sequential condition, which raises the question of whether responding in this condition was a function of sequential presentation or the fact that higher-ranked preferred foods were available. It is important to note that consumption of target foods from the simultaneous condition was quickly established for both Aaron and Eva when those foods were moved to the sequential condition and the same lower-ranked preferred foods were provided contingently. If the differential rankings of preferred foods were solely responsible for consumption in the sequential condition, it is unlikely that we would have observed such an immediate change in consumption when foods from the simultaneous condition were presented sequentially with lower-ranked foods.

Regarding the ranking of preferred foods in the preference assessment, it is also important to note that different rankings may have been observed with repeated preference assessments (e.g., MacNaul et al., 2021), or if the foods were assessed again within a different array of foods (e.g., Graff & Larsen, 2011). There are examples in the preference assessment literature of cases in which the lowest-ranking item and the highest-ranking item in a preference assessment were both similarly efficacious as reinforcers (Graff & Larsen, 2011), and cases in which almost all items identified in a preference assessment functioned as reinforcers when compared to a control condition, regardless of rank (Morris & Vollmer, 2020). That is, although lower-ranking preferred foods were coincidentally assigned to the simultaneous condition, it is also possible that there was not a substantial difference in relative reinforcing efficacy between those foods and the higher-ranked foods assigned to the sequential condition. Thus, we recommend that future researchers include a reinforcer analysis before assigning preferred foods to simultaneous or sequential conditions to assign foods with similar relative reinforcing efficacy to both conditions.

Future researchers may also wish to explore the stimulus features of foods that may affect the success of either intervention. Possible stimulus features to consider include the extent to which a preferred food visually obscures a target food, the extent to which a seemingly strong flavor (e.g., olives, bleu cheese, jalapeño) masks the flavor of a milder food, or the extent to which the target and preferred foods have a similar shape, size, color, or texture. It is possible that certain stimulus features may affect the efficacy of the simultaneous presentation intervention, whereas others may affect the efficacy of sequential presentation. For example, it is possible that simultaneous presentation may be more effective in cases where the preferred food is commonly described as being strongly flavored (e.g., black olive) and could visually obscure the target food (e.g., a pea inserted inside a black olive). Likewise, it is possible that sequential presentation may be more effective in cases where the target food creates an establishing operation for the contingent preferred food (such as providing a sip of cold juice or water contingent upon consuming a salty target food like pretzels). The impact of these types of stimulus variations thus represents a second potential area of future research. Future researchers may also wish to explore the effects of bite size across different foods. Most target foods were cut to similar sizes of approximately 2 cm, but some foods such as the sweet potato inserted into the Goldfish for Ben may have varied given the size of the particular Goldfish cracker and how much hollow space was available.

A third limitation is that participants did not experience an equal number of treatment sessions in both conditions because we used a random number generator to identify session order. It is possible that different response patterns would have been obtained if sessions were balanced in dyads. Aaron experienced fewer simultaneous sessions, but differentiation in responding between conditions was observed immediately. Eva’s responding did not become differentiated until the end of treatment. It is interesting to note that she experienced more simultaneous sessions than sequential sessions (i.e., the sequential condition was most effective for Eva even though she experienced it fewer times). In addition, given that consumption of foods from the simultaneous condition increased almost immediately when the same foods were transferred to the sequential condition suggests that the treatment, rather than the number of sessions, was responsible for the increase in consumption. Future research could address this limitation by assuring an equal number of sessions occur in each condition, while still randomizing the order of sessions.

A fourth limitation is that Ben did not respond to either treatment. There are a number of factors that may have contributed to Ben’s response, but it is difficult to determine what these may be without additional research across larger numbers of participants with varying profiles. It is possible that Ben’s particular history of reinforcement for refusing target foods produced durable refusal responses (looking away, pushing food away) that were not sensitive to the simple antecedent and consequent arrangements provided in either condition. Ben had a smaller food repertoire than Aaron and Eva and had fewer selections and consumption of foods during the preference assessment. It is possible that food in general did not function as a reinforcer for consuming other foods for Ben, or that the specific foods assessed in his preference assessment were not reinforcers.

Future research could begin to evaluate participant characteristics associated with treatment efficacy by comparing sequential versus simultaneous presentation across a larger participant pool and in conjunction with documenting participant characteristics suspected to influence efficacy to identify patterns of responding. Future research should also evaluate systematic modifications to both sequential and simultaneous presentation that may increase consumption for participants like Ben who do not initially respond to either treatment. These modifications could include differential reinforcement with nonedible reinforcers, the addition of escape extinction, shaping or graduated exposure (e.g., Koegel et al., 2012; Tanner & Andreone, 2015), or use of a high-probability instructional sequence (e.g., Penrod et al., 2012). Ben participated in another study following his participation in the current study, in which consumption of target foods was successfully established for him through the use of shaping and differential reinforcement without escape extinction.

A final limitation is that we did not conduct any reinforcement schedule thinning of preferred foods in the sequential condition. It is not practical to continue providing one bite of preferred food for every bite of target food consumed; therefore, another area of future research is to evaluate effective fading or schedule-thinning strategies once consumption of novel foods is established. We did not conduct any stimulus fading of preferred foods within the simultaneous condition because consumption did not increase in this condition. However, future researchers may wish to evaluate such fading procedures for cases in which simultaneous presentation is effective. There are multiple ways that stimulus fading may be accomplished, such as by gradually increasing the size of the target bite, gradually decreasing the size of the preferred bite, or both. Future researchers may also wish to evaluate the extent to which this intervention is effective in establishing a wider repertoire of healthy foods (i.e., beyond just two additional foods) and the extent to which responding is maintained in other settings with other caregivers (i.e., at home with parents).

When considered together with previous studies, our results indicate that consumption of target foods can increase in a classroom setting for children who are safe oral feeders with mild food selectivity, but that further comparisons of sequential and simultaneous presentation with a greater number of participants is also necessary. It is possible that variables such as participant age, size of current food repertoire, intensity of aversion to nonpreferred foods, stimulus properties of preferred and target foods, or previous treatment attempts may affect the success of one type of food presentation over the other. However, it is not possible to identify such variables given the limited number of comparisons and limited number of participants. Additional treatment comparisons with a larger number of participants may also begin to identify the conditions in which escape extinction is and is not necessary with sequential or simultaneous presentation, and the extent to which either of these treatments are effective in a variety of natural settings with caregivers and teachers.

Author Notes

This manuscript was completed in partial fulfillment of a master’s degree in applied behavior analysis at Regis College by the first author. We thank Rachel Pinkhamn, Kendra Penney, Brittany Ashdown, and Kirsten Lally for their assistance in conducting sessions and scoring interobserver agreement.

Data Availability

Data are available from first author upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Video of Eva’s baseline sessions was not available.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahearn WH. Using simultaneous presentation to increase vegetable consumption in a mildly selective child with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:361–365. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandini LG, Anderson SE, Curtin C, Cermak S, Evans EW, Scampini R, Must A. Food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorders and typically developing children. Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;157(2):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandini L, Curtin C, Phillips S, Anderson S, Maslin M, Must A. Changes in food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2017;47(2):439–446. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2963-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjasuwantep B, Chaithirayanon S, Eiamudomkan M. Feeding problems in healthy young children: Prevalence, related factors, and feeding practices. Pediatric Reports. 2013;5(10):38–42. doi: 10.4081/pr.2013.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley SD, Newchok DK. An evaluation of simultaneous presentation and differential reinforcement with response cost to reduce packing. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:405–409. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.71-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cariveau T, Fetzner D. Experimental control in the adapted alternating treatments design: A review of procedures and outcomes. Behavioral Interventions. 2022;37(3):805–818. doi: 10.1002/bin.1865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cengher M, Ramazon NH, Strohmeier CW. Using extinction to increase behavior: Capitalizing on extinction-induced response variability to establish mands with autoclitic frames. Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2020;36(1):102–114. doi: 10.1007/s40616-019-00118-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cermak SA, Curtin C, Bandini LG. Food selectivity and sensory sensitivity in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2010;110(2):238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley JG, Peterson KM, Fisher WW, Piazza CC. Treating food selectivity as resistance to change in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(4):2002–2023. doi: 10.1002/jaba.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin S, Healy O, Leader G, Hughes B. Comparison of behavior intervention and sensory-integration therapy in the treatment of challenging behavior. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2011;41:1303–1320. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstein S, Laniado D, Glick B. Does picky eating affect weight-for-length measurements in young children? Clinical Pediatrics. 2010;49(3):217–220. doi: 10.1177/0009922809337331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WW, Piazza CC, Bowman LG, Hagopian LP, Owens JC, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff RB, Larsen J. The relation between obtained preference value and reinforcer potency. Behavioral Interventions. 2011;26:125–133. doi: 10.1002/bin.325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard KL, Anderson SE, Curtin C, Must A, Bandini LG. A comparison of food refusal related to characteristics of food in children with autism spectrum disorder and typically developing children. Journal of the Academy Nutrition & Dietetics. 2014;114(12):1981–1987. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SL, Stewart PA, Schmidt B, Cain U, Lemcke N, Foley JT, Peck R, Clemons T, Reynolds A, Johnson C, Handen B, James J, Manning Courtney P, Molloy C, Ng PK. Nutrient intake from food in children with autism. Pediatrics. 2012;130:S145–S153. doi: 10.1542/pedS.2012-0900L. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibañez VF, Peters KP, St. Paul JA, Vollmer TR. Further evaluation of modified-bolus-placement methods during initial treatment of pediatric feeding disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;54:287–308. doi: 10.1002/jaba.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern L, Marder TJ. A comparison of simultaneous and delayed reinforcement as treatments for food selectivity. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29(2):243–246. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel RL, Bharoocha AA, Ribnick CB, Ribnick RC, Bucio MO, Fredeen RM, Koegel LK. Using individualized reinforcers and hierarchical exposure to increase food flexibility in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2012;42:1574–1581. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1392-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledford JR, Whiteside E, Severini KE. A systematic review of interventions for feeding-related behaviors for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2018;52:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2018.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacNaul H, Cividini-Motta C, Wilson S, Di Paola H. A systematic review of research on stability of preference assessment outcomes across repeated administrations. Behavioral Interventions. 2021;36:962–983. doi: 10.1002/bin.1797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SL, Vollmer TR. A comparison of methods for assessing preference for social interactions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53:918–937. doi: 10.1002/jaba.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musti-Rao S, Plati E. Comparing two classwide interventions: Implications of using technology for increasing multiplication fact fluency. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2015;24:418–437. doi: 10.1007/s10864-015-9228-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadon, G., Feldman, D. E., Dunn, W., & Gisel, E. (2011). Association of sensory processing and eating problems in children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Research & Treatment, 2011, Article 541926. 10.1155/2011/541926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Najdowski AC, Tarbox J, Wilke AE. Utilizing antecedent manipulations and reinforcement in the treatment of food selectivity by texture. Education & Treatment of Children. 2012;35:101–110. doi: 10.1353/etc.2012.0004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MR, Piazza CC, Martinez CJ, Volkert VM, Santana CM. An evaluation of two differential reinforcement procedures with escape extinction to treat food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35(4):363–374. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrod B, Gardella L, Fernand J. An evaluation of a progressive high-probability instructional sequence combined with low-probability demand fading in the treatment of food selectivity. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45(3):527–537. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson K, Ibañez V. Food selectivity and autism spectrum disorder: Guidelines for assessment and treatment. Teaching Exceptional Children. 2018;50(6):322–332. doi: 10.1177/0040059918763562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson KM, Piazza CC, Volkert VM. A comparison of a modified sequential oral motor approach to an applied behavior-analytic approach in the treatment of food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2016;49:485–511. doi: 10.1002/jaba.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza, C. C. (2008). Feeding disorders and behavior: What have we learned? Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 14, 174–181. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1002/ddrr.22 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Piazza, C. C., & Carroll-Hernandez, T. A. (2004). Assessment and treatment of pediatric feeding disorders. In Encyclopedia on early childhood development [online] (pp. 1–7). Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development.

- Piazza CC, Patel MR, Santana CM, Goh H-L, Delia MD, Lancaster BM. An evaluation of simultaneous and sequential presentation of preferred and nonpreferred food to treat food selectivity. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35:259–270. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza CC, Patel MR, Gulotta CS, Sevin BM, Layer SA. On the relative contributions of positive reinforcement and escape extinction in the treatment of food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36(3):309–324. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzo B, Coyle M, Seiverling L, Williams K. Plate A-Plate B: Use of sequential presentation in the treatment of food selectivity. Behavioral Interventions. 2012;27:175–184. doi: 10.1002/bin.1347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rommel N, DeMeyer AM, Feenstra L, Veereman-Wauters G. The complexity of feeding problems in 700 infants and young children presenting to a tertiary care institution. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition. 2003;37(1):75–84. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200307000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio EK, McMahon MXH, Volkert VM. A systematic review of physical guidance procedures as an open-mouth prompt to increase acceptance for children with pediatric feeding disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2021;54:144–167. doi: 10.1002/jaba.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini V, Kadey HJ, Paszek KJ, Roane HS. A systematic review of functional analysis in pediatric feeding disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2019;52(4):1161–1175. doi: 10.1002/bin.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez, M. A., & Crinion, K. M. (2015). Food choices of children with autism spectrum disorders. International Journal of School Health, 2(3), 1–5. 10.17795/intjsh-275

- Sevin BM, Gulotta CS, Sierp BJ, Rosica LA, Miller LJ. Analysis of response covariation among multiple topographies of food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35(1):65–68. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindelar, P. T., Rosenberg, M. S., & Wilson, R. J. (1985). An adapted alternating treatments design for instructional research. Education & Treatment of Children, 8(1), 67–76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42898888. Accessed 24 May 2022

- Swed-Tobia R, Haj A, Militianu D, Eshach O, Ravid S, Weiss R, Aviel YB. Highly selective eating in autism spectrum disorder leading to scurvy: a series of three patients. Pediatric Neurology. 2019;94:61–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2018.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner A, Andreone BE. Using graduated exposure and differential reinforcement to increase food repertoire in a child with autism. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;8(2):233–240. doi: 10.1007/s40617-015-0077-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tincani M. Comparing the picture exchange communication system and sign language training for children with autism. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities. 2004;19:152–163. doi: 10.1177/10883576040190030301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- VanDalen KH, Penrod B. A comparison of simultaneous versus sequential presentation of novel foods in the treatment of food selectivity. Behavioral Interventions. 2010;25(3):191–206. doi: 10.1002/bin.310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woods JN, Borrero CSW. Examining extinction bursts in the treatment of pediatric food refusal. Behavioral Interventions. 2019;34:307–322. doi: 10.1002/bin.1672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan CM, Penrod B. An evaluation of sequential meal presentation with picky eaters. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12:301–309. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00277-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from first author upon request.