Abstract

Chance fractures are rare lesions but are often associated with abdominal injuries. We present a case of a 21-year-old patient who sustained a delayed type of abdominal injury associated with a bonny Chance fracture of lumbar 2nd following a traffic accident. Initial X-rays and computed tomography (CT) scans showed a Chance fracture with subtle bowel images, evading the prompt diagnosis of bowel injuries. However, the toxic signs were presented after 17h of stay in intensive care unit, and hollow visceral perforation was diagnosed in the re-do abdominal CT scanning. The laparostomy with primary anastomosis was performed for complete transection of the middle part of the jejunum. After a follow-up period of 20 days, the patient underwent kyphoplasty, accompanied by posterior fusion of the L1–L3 vertebrae and was found well recovered at 2 weeks follow-up. Clinicians should realize the subtle but meaningful imaging signs to allow prompt diagnosis as well as management when meeting patients with seatbelt sign associated with Chance fracture after a traffic accident.

Keywords: Seatbelt injury, Janus sign, Motor-vehicle collision, Delayed bowel and mesentery trauma, Chance fracture

Introduction

The seatbelt injury was presented in some patients who sustained high energy collisions. The inappropriate usage of restrained system imposed powerful hit on the passengers. Therefore, the seatbelt sign may indicate devastating abdominal injuries. Approximately 10 % of individuals with blunt abdominal trauma (BAT) would turn to hollow viscus and mesenteric injury [1]. The range of severity spans from minor contusions to complete transection. However, the abdominal CT only demonstrated subtle and early pictures of bowel injuries when the patients was immediately sent to emergency unit. The initial images may mislead the further treatment plan for patients with stable hemodynamic. Clinicians should realize the subtle but meaningful signs to allow prompt diagnosis as well as management. A close monitoring of laboratory and physical examination are important to initiate follow-up CT [2]. We present a case in which BAT resulting from seatbelt injury led to a Chance fracture, subsequently resulting in delayed complete transection of the middle part of the jejunum.

Case presentation

A 21-year-old male passenger in the rear seat of a car experienced a collision that caused him to collide forcefully with the front seat while wearing a seatbelt. The patient's car traveling at 90 km/h collided head-on with another vehicle moving at 60 km/h. Following the collision, the patient was taken to our hospital's emergency department, where he arrived with stable vital signs but complained of lower back pain, accompanied by abdominal discomfort and nausea. His medical history was unremarkable. He was conscious with stable vital signs. Upon physical examination (PE), a diagonal linear wound was observed on his chest, and there was bruising on both flanks covering an area measuring 15 cm × 20 cm (Fig. 1). Tenderness upon palpation was noted in the periumbilical region and right shoulder. His muscle strength initially scored 3 but fully recovered after some time. An Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (E-FAST) examination detected a small amount of fluid in the cul-de-sac.

Fig. 1.

A diagonal linear wound accompanied by bruising on both flanks, resulting from the seatbelt.

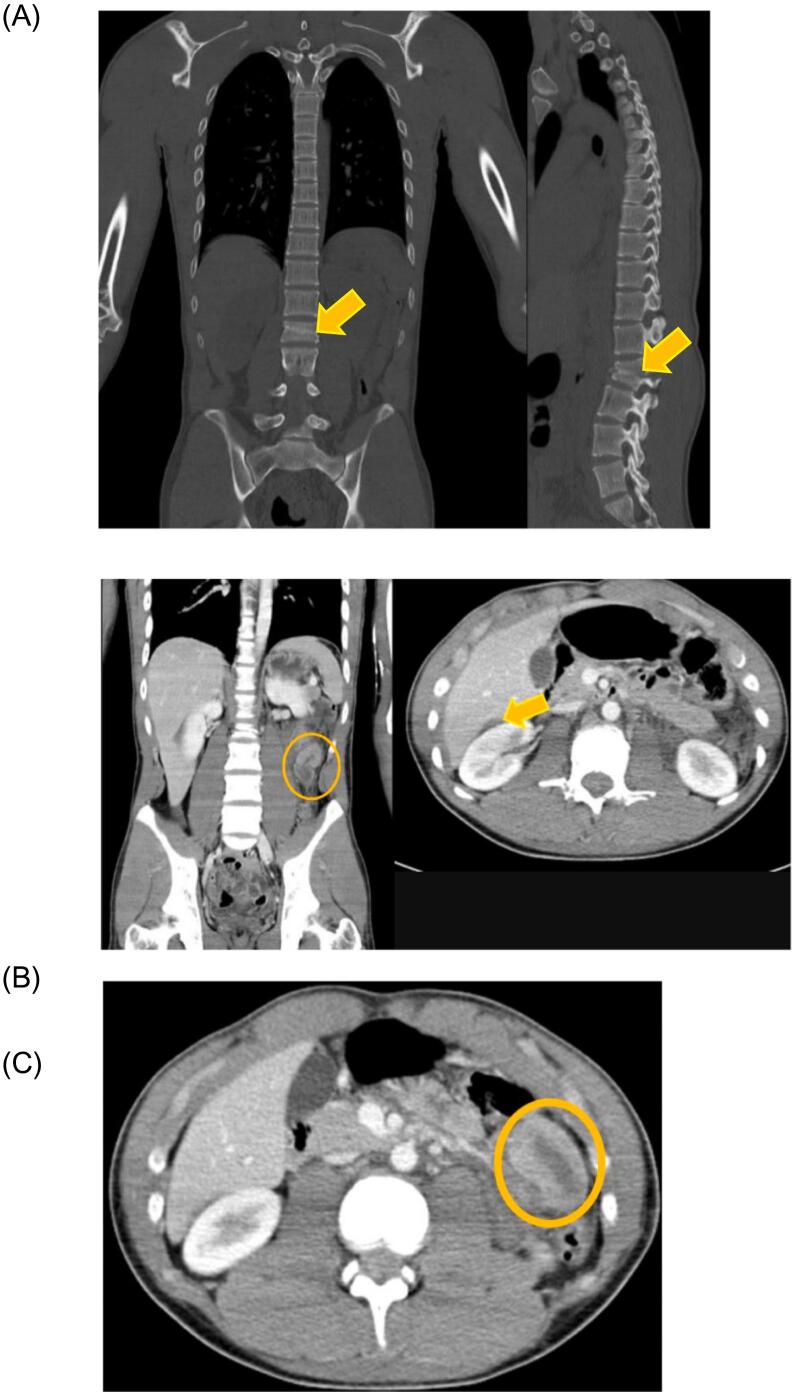

A comprehensive CT scan of the chest and abdomen showed a transverse fracture in the second lumbar (L2) vertebra, commonly referred to as a Chance fracture. Additionally, there was a subcapsular hematoma over segment 6 of the liver, graded as I on the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma [AAST] liver injury scale, and a small pulmonary contusion was identified (Fig. 2a–c). A fracture of the right mid-clavicle became evident after closely monitoring plain films over the course of 1 week.

Fig. 2.

Results of complete abdominal and chest CT. (A) Chance fracture at L2 vertebra (arrow). (B) Subcapsular hematoma measuring 2.5 cm × 1.0 cm over segment 6 of the liver (arrows). This injury was classified as grade 1 according to liver injury scale of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. (C) Presentation of adjacent hypoenhancing and hyperenhancing segments (yellow circle, so-called Janus sign) over the middle part of the jejunum.

Following 17 h of observation in our intensive care unit, the patient's condition progressed to severe abdominal pain accompanied by pale skin and sweating. Auscultation of the abdomen revealed hypoactive bowel sounds, whereas the urine appeared tea-colored. PE revealed muscle guarding and rebound tenderness upon palpation. A second abdominal CT scan showed hollow organ perforation with diminutive amounts of extraluminal air (Fig. 3). This finding prompted further investigation through exploratory laparostomy. Our examination during the procedure revealed a complete transection of the proximal jejunum, situated 15 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz. Adjacent to this transection, a tear was observed in the mesentery. Furthermore, a substantial volume of turbid ascites (1100 mL) was present in the pelvic area (Fig. 4). To address severe hemorrhaging and reduce contamination, we performed resection of the jejunal defect and carried out a primary anastomosis as the essential measures. After a follow-up period of 20 days, the patient underwent kyphoplasty, accompanied by posterior fusion of the L1–L3 vertebrae and was found well recovered at 2 weeks follow-up.

Fig. 3.

CT scan illustrating small amounts of free air within the retroperitoneal space and surrounding the omentum.

Fig. 4.

The proximal jejunum was transected 15 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz, and a tear was observed in the adjacent mesentery. Additionally, several areas of serosa damage and a contusion on the small bowel surface were identified.

Discussion

Previous studies have indicated a high incidence of abdominal injuries among patients with a seatbelt sign following BAT [3]. The present case initially displayed evidence of Chance fracture at L2, inconclusive shoulder plain-film results, and an AAST Grade I liver subcapsular hematoma. Immediate surgical intervention was not warranted; thus, nonoperative management and intensive care unit stay were preferred. However, a delayed occurrence of complete jejunum transection was confirmed surgically after 17 h of admission. Our findings, coupled with previous case series [4,5], suggest that seatbelt injuries after BAT might represent a distinct pathological condition that can evolve into severe complications such as loop transection, perforation, and hemorrhagic shock following a period time of observation.Despite the use of accurate algorithms, the risk of delayed diagnosis for potentially fatal injuries remains [6]. This could be attributed to several factors, such as the gradual development of bowel perforation due to ischemia and necrosis following the initial vascular injury, which might take several hours to manifest [7]. Additionally, peritoneal signs tend to develop slowly in cases of small bowel injury due to the relatively neutral luminal contents, low bacterial presence, and reduced enzymatically activity [8]. It is advisable to perform repeated abdominal sonography. Patients with equivocal signs on the initial CT scan should undergo a follow-up imaging session after 6 h, which is strongly recommended [9]. A similar case report announced that serum amylase could reflect bowel perforation or rupture [2]. We did not use the test while monitoring.

A significant portion of preoperative false-negative TBMI cases have been reported in the literature [10]. This could stem from nonspecific findings on CT scans and a lack of awareness among clinicians regarding these injuries [11]. Upon reviewing our patient's initial CT scan (Fig. 2c), the presence of adjacent low and high enhancement (Janus sign) and thickened bowel walls may potentially indicate bowel ischemia or impending TBMI [12,13].Surgeons' experience and predictive score should guide the use of diagnostic laparoscopy at any juncture [14].

The three-point shoulder-lap belt stands out as the most effective restraint system for preventing intra-abdominal injuries. Nevertheless, improper apply of the restraint system, particularly to the underarm area of the shoulder part and above the level of the iliac crests, can still lead to chest and abdominal injuries [15]. The followings are the life-threatening issues and potential consequences associated with seatbelt injuries. (Table 1.)

Table 1.

The life-threatening issues and potential consequences associated with seatbelt injuries (SBI).

| Injury types | Notes |

|---|---|

| Traumatic abdominal wall hernia | This type of injury is reported in pediatric case series and more than half of children affected had BMI >95th percentile |

| Spinal flexion injuries | L1–L3 vertebral fracture (also known as Chance fracture), which are associated with intra-abdominal injuries in 50 % of cases, including small bowel and aorta or neurologic deficits |

| Bowel injuries | - Rupture of proximal jejunum, appendix, ileum, and sigmoid colon - Subserosa hematoma of the cecum - Handlebar sign may indicate intra-abdominal injuries (IAI) - Hematoma and tear of mesentery - Delayed presentation of small bowel perforation and cecal perforation - Chronic bowel obstruction - Ileosigmoid fistula - Abdominal aortic trauma |

| Subcutaneous hematoma and rupture of abdominis muscle | - BMI and belt placement were associated with increasing incidence of IAI - SBI can be identified clinically and radiologically - Injury to female breast - Rupture of diaphragm and diaphragmatic hernia |

| Cerebrovascular injuries | Cervical SBI, in isolation, is not a predictor of these injuries in children |

Another delayed type of Chance fracture and occult small bowel injury was reported [16]. This was a ligamentous Chance fractures which are more prone to escaping detection than bony Chance fractures. In cases of strong suspicion, MRI is recommended for accurate diagnosis. The patient evaded detection of small bowel obstruction in diagnostic laparoscopy. The author emphasized on oral contrast use in patients who are highly suspected of abdominal injuries.

When a patient is involved in a motor vehicle collision and presents with polytrauma, including possible BAT and critical injuries affecting other systems such as severe brain and/or spinal cord injuries, cauda equina syndrome, and multiple long-bone fractures, along with inconclusive findings on E-FAST, the following strategies can be considered to manage the complex situation of a deteriorating patient:

-

-

Immediate surgical intervention: Given the critical nature of the multiple injuries, an emergent operation should be prioritized.

-

-

Simultaneous general surgery procedures: Perform diagnostic laparoscopy concurrently, which can be converted to therapeutic laparotomy or laparoscopy as required based on findings.

-

-

Comprehensive whole-body CT scan: In cases involving explosions, high-speed motor vehicle collisions, or falls from significant heights, performing a whole-body CT scan is advisable [17]. The potential benefit of abdominal exploration should outweigh the risk of overlooking an injury [18].

Conclusion

The presence of a seatbelt sign following hyperflexion-distraction injury could indicate BAT. Chance fractures frequently correlate with intra-abdominal injuries, although certain injuries might not manifest immediately due to various factors. Clinicians should remain attentive to subtle signs in abdominal CT scans. Close monitoring is crucial, involving successive imaging, laboratory tests, evaluations of vital signs, and physical examinations. It is strongly recommended to conduct a follow-up CT scan 6 h after admission and whenever the patient's condition deteriorates.

Consent for publication

The patient provided informed consent for publication of this article.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chih-kai Huang drafted the manuscript. Chen-Chi Lee participated in the design of the study. Ching-Ming Kwok conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding source

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of generative AI in scientific writing

There is nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Wadhwa M., et al. Blunt abdominal trauma with hollow viscus and mesenteric injury: a prospective study of 50 cases. Cureus. 2021;13(2) doi: 10.7759/cureus.13321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tatekawa Y. A case of seat belt-induced small bowel rupture and chance fracture accompanied by elevated serum amylase. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2021;2021(7) doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjab315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandler C.F., Lane J.S., Waxman K.S. Seatbelt sign following blunt trauma is associated with increased incidence of abdominal injury. Am. Surg. 1997;63(10):885–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohpe Kapseu S., Tchokonte-Nana V. Lessons learned about the management of a traffic road accident victim with abdominal seatbelt sign: case report. Trauma Case Rep. 2023;43 doi: 10.1016/j.tcr.2023.100765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okeke R.I., et al. A case of delayed cecal perforation after abdominal (seat belt) injury. Cureus. 2022;14(8) doi: 10.7759/cureus.27901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke J.R., et al. Time to laparotomy for intra-abdominal bleeding from trauma does affect survival for delays up to 90 minutes. J. Trauma. 2002;52(3):420–425. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smyth L., et al. WSES guidelines on blunt and penetrating bowel injury: diagnosis, investigations, and treatment. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2022;17(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s13017-022-00418-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sule A.Z., et al. Gastrointestinal perforation following blunt abdominal trauma. East Afr. Med. J. 2007;84(9):429–433. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v84i9.9552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouzat P., et al. Early management of severe abdominal trauma. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2020;39(2):269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2019.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaewlai R., et al. Radiologic imaging of traumatic bowel and mesenteric injuries: a comprehensive up-to-date review. Korean J. Radiol. 2023;24(5):406–423. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2022.0998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bates D.D., et al. Multidetector CT of surgically proven blunt bowel and mesenteric injury. Radiographics. 2017;37(2):613–625. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017160092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boscak A.R., et al. Segmental bowel hypoenhancement on CT predicts ischemic mesenteric laceration after blunt trauma. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2021;217(1):93–99. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.23108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper C., et al. Janus sign. Abdom. Radiol. (NY) 2023;48(4):1554–1555. doi: 10.1007/s00261-023-03828-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wandling M., et al. Multi-center validation of the Bowel Injury Predictive Score (BIPS) for the early identification of need to operate in blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries. Injury. 2022;53(1):122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2021.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rischall M.L., Puskarich M.A. In: Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice. Walls R.M.M.D., editor. 2023. Abdominal trauma; pp. 398–411.e2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henry D.A., Bumpass D.B., McCarthy R.E. Delayed diagnosis of a flexion-distraction spinal injury and occult small bowel injury in a pediatric trauma patient: importance of recognizing the abdominal “seatbelt sign”. Trauma Case Rep. 2021;34 doi: 10.1016/j.tcr.2021.100499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chowdhury D. Does a fall from a standing height warrant computed tomography in an elderly patient with polytrauma? World J Emerg Med. 2023;14(4):302–306. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2023.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elbanna K.Y., et al. Delayed manifestations of abdominal trauma: follow-up abdominopelvic CT in posttraumatic patients. Abdom. Radiol. (NY) 2018;43(7):1642–1655. doi: 10.1007/s00261-017-1364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]